Michael Iwama, Kawa Model of Occupational Therapy Developer

Dr. Michael Iwama is the developer of the Kawa Model of Occupational Therapy. He is internationally known for his work and is the Dean of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at the MGH Institute in Boston. He was previously Professor and Chair of the Department of Occupational Therapy at Augusta University (formerly the Medical College of Georgia). He is also an Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto and holds similar adjunct professorial appointments at six universities in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Asia.

Franklin Stein, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA

Contributing Editor

Salute to OT Leaders Series

20Q: Kawa Model of Occupational Therapy Developer

Michael Iwama, PhD, MSc, BScOT, BSc

Development of the Kawa Model

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Describe the Kawa Model of Occupational Therapy and its application to clinical practice.

- Identify the significant issues in healthcare that impact on occupational therapy.

- Discuss the trends in international occupational therapy especially in Japan.

1. As a researcher, you helped develop the Kawa Model as a guide for treatment? Can you give us some background on this?

In the early 1990s, I had a chance to go back to my native Japan on two occasions as an adult. The first trip was to study how Japanese companies attend to their employees' health issues and injuries. I returned again in 1995 as a professor at a Japanese university. I helped them to establish one of the first bachelor programs for occupational therapy.

While I was doing this, I discovered that Japanese occupational therapists had a complicated time understanding theory and the basic principles of occupational therapy. They also did not understand the concept of occupation. All of these were ideas that came from a very different cultural context and are predominantly Western. They reflect the day-to-day experience norms and views of the world that are germane to Western English-speaking cultures.

As I was having some difficulties acculturating back into Japanese life and encountering these views from my colleagues, I began to ask questions about the very core ideas of occupational therapy especially in terms of its relevance and its power to enact a positive difference in the lives of all people. I saw immediately that there was a need to critically evaluate the core ideas of occupational therapy from a cross-cultural perspective. When we take some ideas that were born and celebrated in the Western world, like independence, individualism, and self-determinism as examples, we can take for granted that these are norms to lead a healthy and well life. What happens when you then take these culture-bound ideas into a Japanese context that has been described as a society that is based on collectivism? What I mean by that is that Japanese people grow up learning the world around them from their parents, their teachers, and everyone else, instead of the person or self. Japanese culture focuses on relationships with all of the people around us. In other words, collectives, or groups, are much more important or just as important as the self.

How can we take these theories around self-efficacy, personal causation, and the meaning "doing" (occupation) and apply it to this context? I recognized early on, along with my Japanese peers, that the models that I was importing looked very exotic to the Japanese students and had very little connection with the day-to-day norms and views of wellbeing in everyday life.

2. Let's go back to the fundamental question. Can you describe how the model was formulated?

I saw the need to develop a new model of occupational therapy. I believe that it is imperative that occupational therapists continue to build models instead of assuming that there is one model that is universal in its application. There is a need for many different models that can be applied to very different and specific cultural settings, locations, and conditions.

If people want to read more about this idea that I am putting forward, I would refer people back to an article that I wrote in 2003 in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy, which was deemed to be controversial at the time and still is controversial today. Just like we think that these ideas around occupational therapy are really pertinent and valuable to us here in North America, shouldn't it be also good enough for everyone around the world? In this article, I presented a case against the age of grand theories to explain things for everyone everywhere are over with the modern period. We are now into the postmodern period and the age of relativism. So, I reject the notion that there is one model or a one-size-fits-all answer. I would argue that these models that we hold so sacredly in occupational therapy are not applicable to everyone everywhere. People abide in a different cultural reality and view of wellbeing in the world in which we inhabit.

3. What was the process you went through?

First, I started a focus group. Instead of just translating a model that was made in North America, I decided that we needed to start from scratch. If occupational therapy models can be anchored in concepts and constructs that are deemed to be most essential for our existence and our definitions of wellbeing, then we needed to ask some fundamental questions.

- What is the most important thing in life?

- What are these things that are so important in your life that if you didn't have them, you wouldn't want to live anymore?

- How do you define wellbeing?

- How do you define health?

- What is occupational therapy?

- What should it be in the Japanese cultural context and day to day realities?

We started to meet on a weekly basis at a university in Okinawa Prefecture, where I was living at the time. I brought together therapists, students, professors of occupational therapy, and then eventually, clients. On a side note, all of the members that were recruited for this qualitative research project were actually people who had attended a national seminar in Japan that I put on in the mid-1990s explaining the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) and the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (CMOP), now called the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E).

I gave this presentation in the Japanese language. It was an epiphany to me to find so many people who felt discouraged and dejected because they thought that this was their chance to understand imported Western occupational therapy ideas and models and they couldn't. When I gathered those people together, I said, "The problem is not in your own minds," because people were blaming themselves for being not cognitively competent enough to be able to understand these concepts from America and from Canada. At the end of the day, it wasn't their lack of intelligence that was the problem. The problem was occupational therapy theory was developed in the Western world.

We tried to apply a modified process of grounded theory, which is a qualitative research method that is probably closest to being positivistic amongst the qualitative research methodology. Grounded theory was very popular at the time, and it is the method that was put together by Bernard Glaser and, Anselm Strauss. However, I found that even qualitative research methods are culturally bound. With grounded therapy, there is an assumption that you can run your focus groups and have everybody exercise democracy and that everybody has an equal voice. The problem is that most Japanese people can't understand the concept of democracy. This is because they've learned through the Confucian ethic of filial piety which are ideas from China and Korea. (In Chinese Buddhist and Taoist ethics, filial piety is a virtue of respect for one's parents, elders, and ancestors.) Social groups are always structured hierarchically. There is no such thing as equality in any Japanese group.

Typically, in a group discussion like this in Japan, the most senior person in the room will always be the first to speak. And if this person does not speak or have an opinion on something, everybody else will be very reluctant to be able to then voice their opinions. In order to get around that, we had to have the study participants answer questions on pieces of paper so they were not identifiable. Then, we had another subgroup that would vet all of these comments and post them onto this big board on the wall. This is how we went about developing the Kawa Model.

4. How long did it take you?

It took us a good part of almost a year to develop a framework. At the time, it was very unlike any of the contemporary models in occupational therapy that we had so far. It was based on a Japanese view of the world, which differs from a Western cosmology. Even from the time of the enlightenment and even before, "Westerners" are rational in our thinking. We have this propensity to break things down into categories including things within ourselves and our environment. Once we group them, we like to then put names on all of these different groups and classifications.

We then take all of these items and we vet them against either ourselves or a collective truth that we find to be correct. We not only like to put things into groups, but we also want to take all of those different items and put them on a hierarchy of importance. You can find all of this in critical social science literature. In contrast, the indigenous peoples of the world, and Japanese people, and Asian people tend to learn cosmology, or a view of the world and the universe, the meaning of it all, and how all things are connected. They are unified and connected, always in flux, and ever-changing, but none of these parts are inseparable. If one thing changes in your environment and something is always changing, everything else is affected and changes as well.

Kawa Model

5. What are the components of the Kawa Model?

I'll explain this in the metaphor of nature, like a river, in a few moments. But first, I want to say that in the Western world, many of us believe that there is a single deity, a God, who is almighty, separate from us and the universe. We have the self as a separate entity. Under the theology of Christianity, all people are equal under God, yet still, there is a sense that God loves me, individually. Then also in this cosmology, we have the rest of creation, which is nature. Nature can be broken down into living things and nonliving things like the sky, the water, the earth, flora, and fauna. Given enough time, the Western man will develop a taxonomy and be able to say what things are related and which ones aren't and will come up with different rules to further those truisms.

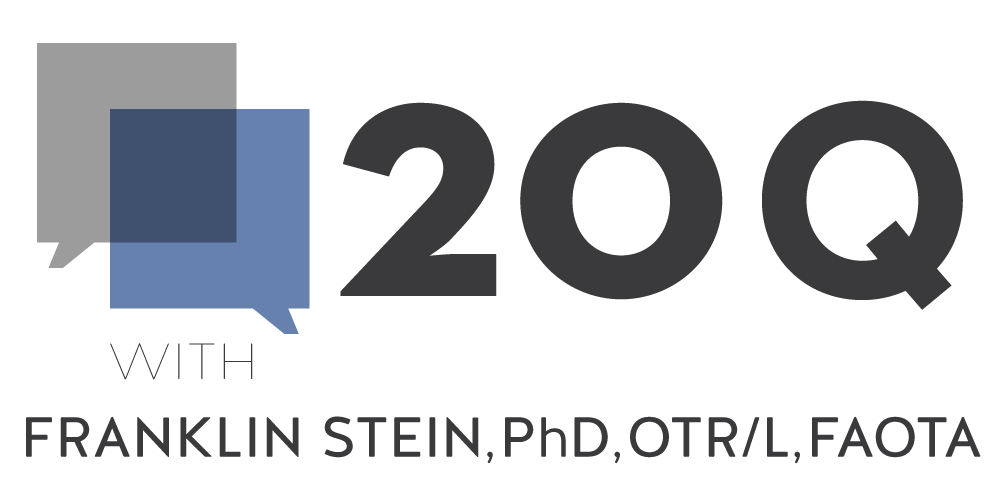

We developed a model (Kawa meaning river) and that model was made up of four elements. These four things are encapsulated into a circle (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Four elements of the Kawa model.

You have these four boxes in the middle of the circle and the boxes are all connected to one another. If you ask anyone from the team that developed the model, they'll say, "These boxes are always in flux. If one increases in size, all of the other boxes will slightly decrease in size, and everything is always in this flux and flow." It is kind of like an amoeba.

In contrast, models from Western occupational therapy have clearly developed components that are separate and independent of one another. They interact but they are deemed to be independent. Contemporary occupational therapy models always have, for example, a concept for self, a separate concept for the environment, and most of the time a concept for this thing that we call occupation. Others will say, "Well, OT models also hold to the same principles. Everything's always in flux." Yes, but the main difference is that all of these entities are actually inseparably connected. They cannot be separated.

It is not like you have the self and you have the environment, and then occupation connecting the self to the environment. And then, occupational therapy is required if this interaction between these two elements is not going so smoothly. We get feedback from the environment and then make decisions as to whether we want to prolong that activity, modify that activity, or stop that activity. In this particular model, the self and the environment are one. And this is why, if we present occupational therapy models to Japanese OTs, they can't quite get it. They'll say, "If the self and the environment are already inseparably intertwined, what is the instrumental value of this thing that you call occupation?" "The environment is in me as I am in the environment. Why do I need occupation?" Isn't that a good question?

This is why we need to develop all kinds of models in occupational therapy that our clients can understand and relate to so that they can appreciate the value of occupational therapy in their lives. The components, those four boxes, are:

- Life flow and health

- Environmental factors (the social and the physical environment)

- Life circumstances and problems

- Personal assets and liabilities (personality traits that the person has within themselves). Perhaps the person is really headstrong and stubborn, or maybe they're really relaxed and laissez-faire. Maybe the person went to university and got a degree in a particular field like botany and biology so they really know a lot about plants. Maybe they've been imbued with a natural ability to play instruments or paint and draw. Maybe they are really good with computers, mathematics, or languages. These are all examples of personal factors.

When we take a look at these four components of the model, we'll see that there's an interplay between life flow and health and the environment, with the problems and difficulties and challenges that they face in everyday life, and then personal factors and abilities that a person has within them. I say the word liability because in some cases, your stubbornness and your OCD tendencies may become a point of frustration if you incur an injury or an illness and you lose your ability to do something that you really enjoy doing well. At the same time, those same traits can become an asset if you are organized and determined and are able to channel that energy through some appropriate therapeutic activities.

6. Can you explain this metaphor in layman's terms?

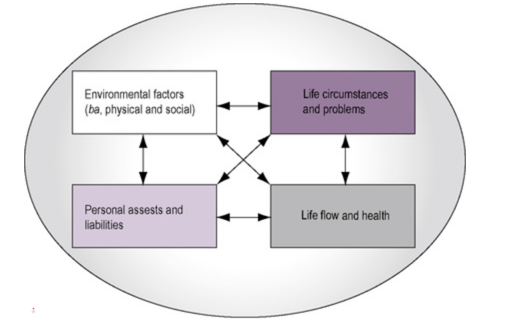

An easier way to explain these four components is in the metaphor of a river. Imagine a river starting up in the mountains as a small stream as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. River metaphor of the Kawa model.

It's symbolic of birth, and as that water flows downstream pulled by gravity, it gathers momentum and begins to meander and goes over all kinds of different terrain. Eventually, after a very long journey, it then enters into a large body of water, be it the ocean or a large lake, which then can be symbolic for the end of life. Seen in this way, a river is like a long story. The story unfolds and changes from moment to moment, and everything is always in flux. If you were to take a cross-section of this river at any point along its length, you would see essentially four elements that are always in interplay with one another.

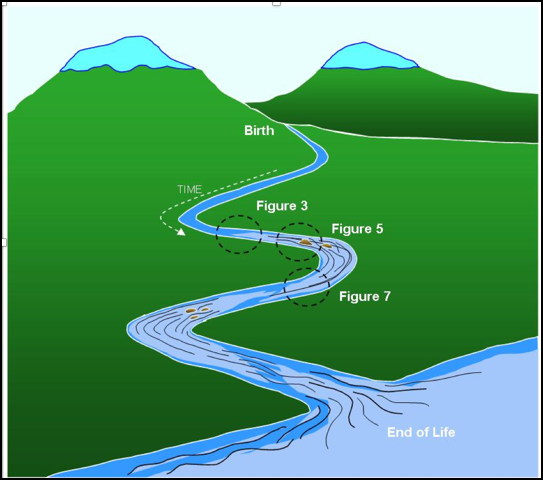

We can assign these same 4 elements within this metaphor as such: Rocks (life circumstances and problems), River Sides and Bottom (environmental factors), Driftwood (personal factors), and Water (life flow and health). This can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The metaphoric elements in the river.

At one moment the river might be full of rocks and debris, and at other moments around another bend of the river, it may seem as if there are hardly any rocks at all, and the water is deep and wide and flowing quite nicely. The water in the river is symbolic of life flow and health. The quality of the flow of water (current) is dictated by the river walls and sides, which are symbolic of the environment. If there are problems in your social or physical environment due to an injury or a problem, the river walls may be thicker thus creating a smaller channel of flow for the water making either the current smaller or more turbulent. Conversely, if you have good things happening in your physical and social environment, the "river walls" will expand and allow more water to flow through its course. Occupational therapy professionals are interested in manipulating the social and the physical environment for their clients to see in what ways these wall thickenings can be eroded or expanded to allow greater water to flow.

The third box inside of the model contains rocks of different sizes and shapes. These rocks provide an impediment to the flow of water in combination with the river walls and sides. Problems or issues that appear in a person's life are also connected with the social and physical environment. The rocks are symbolic of these difficulties.

The last of the four components in the river is driftwood. Driftwood can float on by or it can get caught between the rocks and the river walls and sides. The driftwood can combine together with the rocks and thickening river walls to create even a larger impediment to flow. However, driftwood can also have a very positive effect. It can also hit a rock and move it out of the way to create a new channel of flow. It can also erode the river walls.

You can see how these four elements are always in play with one another. And, if you cut the river and look at a cross-section from moment to moment to moment (as in Figure 3), you can see these 4 elements at play. Think back to when you were 13 or 14 years old, and you were having conflicts with your parents because you wanted to be more independent. What did your river look like? What were the problems and challenges you were facing and perceiving? What kinds of driftwood were in your river. How was your river flowing at that time?

Now, I'll just go on to add that Western occupational therapists have added one more meaning to the water of life flow and health. They will say that this to them is what occupation is. Often, when they use the Kawa model to guide their occupational therapy, they'll often think about using activity and focusing it onto certain rocks (problems), aspects of the physical and social environment (river walls), or to enhance personal factors (mobilizing driftwood) in order to punch a bigger hole through the blockage and the river.

7. How can this be used in practice?

Often in practice when this model is being used, the clients will understand the model and subsequently occupational therapist's purpose before the therapist has a chance to be able to fully explain it. At first, we thought that this model would only be good for Japanese people, but we discovered that the metaphor of the river as a depiction of a person's life journey was something that people all over the world could relate to. This is why it is starting to really pick up in America and Canada as well. Many therapists are saying that the river metaphor can be used as a vehicle for communication with their clients.

It provides a common language that is established between the therapist and the client. It helps us as OTs to get to those aspects of a person's wellbeing and everyday life that really matters the most in an accessible way. We don't have to revert back to the sophisticated models of occupational therapy that have a language and concepts that clients don't always understand. Additionally, there are norms that are embedded in the model that can be biased toward upper-middle class and white experience of everyday life. Culture is really important in everything that we do, especially in occupational therapy. Let's say that a person has had an L3-L4 soft tissue injury of the lumbar spine. The medical personnel run a CAT scan and verify the extent of the injury and diagnosis. Then at that point, a prescription is then made for occupational therapy. As such, most health professionals are very much focused on the problem that is located in the body. They want to know what part of this body is broken or not functioning normally, and that's where the interventions normally tend to focus. I believe that occupational therapy's greatest power lies not in just trying to help fix the things that are broken or malfunctioning inside of the body, but rather in helping the client address the social and physical consequences of those medical embodied pathologies on everyday life.

We need models that focus on the interface between the self and the environment. When assessing a client, often it is hard to work on one definable thing. They may have other comorbidities beside a back injury, like depression. By the time you see them, a combination of a new injury and other issues can have had a profound effect on their everyday life.

8. What are the steps of the Kawa model?

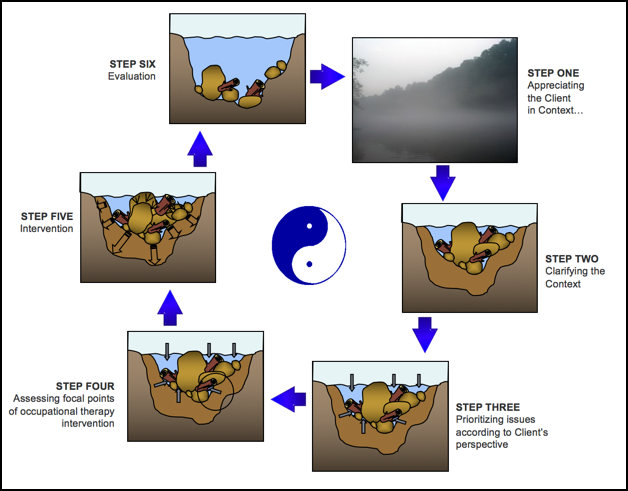

The steps of the Kawa model are outlined in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The steps of the Kawa model.

The therapist using the Kawa Model will then assess the person's situation of their experience of everyday life through those four concepts.

- Appreciating the client in context

- Clarifying the context

- Prioritizing issues according to the client's perspective

- Assessing focal points of occupational therapy intervention

- Intervention

- Evaluation

9. Can you give us an example of how this would work using these steps?

Sure, here is an example of how this might work for a client session.

Appreciating the client in context:

- "Mr. Smith, how are things going in general for you every day?"

- "Can you tell me about what's going on, and how you're dealing with your back injury?"

- "How has it affected you and the activities that you do on a day to day basis?"

- "How are you doing in general?"

Clarifying the context (River wall and sides--the social and physical environment):

- "Mr. Smith, tell me about your family."

- "Tell me about your social connections and the people that you normally interact with on a daily basis."

- "How are things going in those relationships? Have any of those been affected by this injury that you've had?"

- "What about the physical environment? What kind of a house do you live in? Do you have to climb a lot of stairs to get into your place? Is that a problem?"

- "What about your workplace?"

- "Or when you go bowling?"

- "Describe what that physical environment is like and the kinds of difficulties that you're encountering in those areas."

Prioritizing issues according to the client's perspective:

- "What kinds of specific problems and difficulties are you encountering every day out there in the real world? Tell me about them?"

- "How big are these problems for you?" (Rocks)

- "This will determine the size of the rocks that are in your river and how many of them there are."

- "I'd like to know, Mr. Smith, a little bit more about yourself. What are you really good at? What kinds of things do you really enjoy doing? If you were not injured, what kinds of things would you be engaged in? Oh, I see that you've gone to college. What did you study? What other kinds of things would other people tell you that you're really good at or that they appreciate about you?" (Driftwood)

Assessing focal points of occupational therapy intervention:

- "Mr. Smith, let's take another look at another section of your river from six months ago. What did your river look like back before any of these medical problems happened?"

- "How would you like your river to look six weeks from now, six months from now, six years from now?"

There are many different ways to use the Kawa model. Some people use it as a mental framework only. Some people will actually use a drawing, while others use a three-dimensional model. It can be great as a group activity as well. "Here, use these materials to build a river that explains how your life is going right now."

Intervention:

When they use the Kawa model, occupational therapists are always looking for the areas of the river that are blue or show even a trickle of water. Why? Because wherever there's a trickle or flow of water, there's the potential for greater flow. This is a strength-based model. It appreciates all of the assets that a person has and really tries to see the reality of the everyday life of the client through their eyes, through their words, and through their experience. We're not taking a model based on some other ideals and then forcing and cramming it onto the client.

Evaluation:

We could then use the model again to see if things have changed after intervention.

Future Research

10. What is future research in this area?

The Kawa model was meant to be a gift from clinicians to clinicians. Clinicians aren't always the most prolific writers, and publishers of articles, and they're not necessarily geared toward research and science. Many are very good consumers. I think the future of the Kawa model is that clinicians will begin to partner with academics to be able to demonstrate the efficacy of the Kawa model in practice. There is a steady trickle of articles that are coming into play that discuss the Kawa model and its effectiveness and usefulness. We need more from a very diverse cross-section of practice and settings and not just in America but in other countries around the world. Essentially, the truth is that every client's life is uniquely configured. Everybody has a beautiful story and an interesting one, and that's what I want occupational therapy to concentrate on. That's where I think the future of research is in the Kawa model.

A lot of research itself is quantitative and positivistic in nature. I think that researchers and scientists who abide in a much more positivistic genre of inquiry will want to take the Kawa model, and then to in some ways condense it into more standardized measurable categories. I think that's fine too. I think that the Kawa model is open to adaptation. Really at the end of the day, you want to be able to help your client. So, if there's a way to be able to modify it in different ways, you have my permission. It is like an open source software. I have been given the credit for having developed the Kawa model, and that's all the recognition that I need. People who know me also know that I have vowed from the very beginning not to make one penny profit from the Kawa model.

That is why nothing is for sale, but we'd like people to be able to acknowledge its roots in occupational therapy. I think that for the Kawa model to go forward, it also needs to not only be researched in terms of its efficacy, but also it needs to be modified and tried in different settings. I think that in itself would be quite informative to future use and development of the Kawa model.

Background

11. As this is a "Salute to the OT Pioneers," tell us your story. Where did you grow up?

I was born and raised on the island of Okinawa, Japan. It's the smallest and newest Japanese prefecture. Okinawa is a small island that lies southern-most in the Japanese archipelago. In fact, it has its proximity to China, Taiwan, the Korean peninsula, the Philippines, and Japan. For that reason, the American military called it the Keystone of the Pacific. Even though I grew up in a Japanese home in Okinawa, because the American military had established these massive military bases there, I was fortunate to be sent by my parents to an American school. That's where I went to school until I reached my teens.

My family then moved to Vancouver, Canada. The Vietnam War was going on at the time, and my parents didn't want us three boys, I have two older brothers, to naturalize as American citizens for fear that we would be sent to Vietnam as GIs, and maybe come back in a body bag. I'm not trying to make fun or light of the enormous sacrifice that 55,000 American young men made in the Vietnam War, but that is something that my parents did not want us to be a part of. Maybe that had something to do with growing up on the Island of Okinawa and being surrounded by military machines and military personnel. Anyway, we ended up in Canada where I went to a place called Killarney Secondary School (high school) in the Southeast part of Vancouver. I then got my first bachelor's degree in exercise physiology at the University of Victoria.

I began working with elite athletes and found out very quickly that that was no fun. Elite athletes, by the way, are some of the most egocentric people on earth. I felt like a glorified water bottle holder, and it was just too boring for me. I wanted to do something for people who were at sub normal levels of performance trying to reach some semblance of normalcy.

12. What was a turning point in your life?

At the time, the natural progression was to go to physical therapy school. In Canada, we call it physiotherapy. I was accepted into a bachelor's program of physiotherapy. I was at a rehabilitation hospital at a clinical fieldwork placement and was working with an elderly woman every day doing leg raises after a hip injury. And as I was counting repetitions, I spied a couple of occupational therapists across the gymnasium floor. They were a married, American couple from the University of Southern California, and they were working with someone who had had a stroke. They were doing something really different with this patient. I approached them, and they began to talk about occupational therapy in such a compelling way. It fascinated me to the point whereby at the halfway point of my fieldwork placement, I was living in their basement.

It didn't mean anything to me at the time, but they said that their teachers were people like Mary Riley and Jean Ayres, icons in our field. And, when I was sitting in their dining room table, I noticed a tree carving up above the lintel of the entrance into the kitchen. I said, "Oh, that's a really nice carving. Which one of you did that?" And they said, "Well, neither of us did. Our classmate back at USC made that named Gary Kielhofner."

From this experience, I quit physical therapy and enrolled in the University of British Columbia's bachelor's program in occupational therapy. This is the best decision I have ever made.

13. Who were some of your other mentors?

After graduating, I started one of the first standalone private practices and vocational rehabilitation programs using a method that came out of California using a work capacity evaluation and work hardening. I experienced such success with it that Charles Christiansen (Chuck), the new director of rehabilitation medicine at the University of British Columbia, invited me to come and teach at the University of British Columbia. This is how I learned that I really loved teaching and wanted to go further into academia. Chuck advised me on the kinds of programs I should be looking at, and I went on to do a master's degree also at the University of British Columbia in Canada. It was a master's of science degree in rehabilitation science. From there, I had a couple of social scientists on my degree committee, and it turned me on to the social sciences. Eventually, I went on to do a PhD in sociology in Japan at Kibi International University.

My supervisor was the former chair of sociology at the University of Toronto, Canada, and he had studied at Berkeley with other Japan sociologists. It was the perfect doctoral training experience for me. From there, I became interested in critical social sciences and I would go on to then enter into the PhD program at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands in health and medical anthropology. What was really interesting about Leiden is that is has one of the most extensive repositories of cultural works from Japan through the Dutch East India trade so there were a lot of Japan scholars there. It's a very famous university, and it's where René Descartes and Spinoza studied and where Einstein held the chair of physics for many years. Rembrandt is also from Leiden.

Another great mentor was Elizabeth Townsend at Dalhousie University. When I left Japan to come back to North America, it was Elizabeth Townsend who gave me a job at Dalhousie University where I was for two and a half years before another great occupational therapist, Helen Polatajko, invited me to join the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto. Her PhD was a supervised or evaluated by none other than Dr. Frank Stein.

Frank Stein is also another great OT. He helped me get my job here at Massachusetts General Hospital and has given me timely advice at different parts along the way. I hope my work is seen as an extension of some of the great work that Dr. Frank Stein has done. His wisdom and advice is also invested in me, and so it's with great honor and pleasure that I acknowledge you, Frank. Thank you so much.

Career

14. Tell us a little bit about your OT journey.

As I mentioned, early on I went into private practice and worked at the same rehabilitation center where I related that story about changing from physical therapy to occupational therapy, called the Gorge Road Hospital in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. When I worked in private practice, I was qualified as an expert witness in the Supreme Court of British Columbia, Canada. I had a wonderful idyllic life. I had lots of money and drove a red Tiara six convertible sports car, lived in a penthouse apartment in the City of Victoria that overlooked the harbor, and used to take a helicopter to Vancouver to either appear in the Supreme Court or to lecture in the occupational therapy program at the University of British Columbia. I say that with a little bit of a chuckle. Those days are long gone by the way.

15. When did you start teaching?

At another turning point in my life, I was invited to help establish one of the first bachelor's programs in occupational therapy in Japan. By then, I had left clinical practice and was a full-time lecturer. I did not practice occupational therapy in Japan, although I was very close to it. From there, I moved from that University to Dalhousie, a university in Canada from the years 2002 to 2005. In 2005, I joined the Faculty of Medicine in the Rehabilitation Sciences Institute at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. I was there for eight years, and then I had an invitation to become chair of the occupational therapy program at Augusta University. It was formally called The Medical College of Georgia. I was there for six and a half years before then being invited to take this job at the MGH Institute, and now I serve as the Dean of the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, I also serve as a professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy. I have been here for about a year and a half now, and I oversee many graduate programs.

16. Describe some of the work you did.

As I mentioned, I worked mainly in the field of vocational rehabilitation in the 1980s, and at the time, there weren't a lot of people doing a lot of this in occupational therapy, let alone in Canada. I ran work hardening programs, work capacity evaluation programs, functional capacity evaluation programs, as well as a consulting service in ergonomics.

16. What were some of the interventions you used?

All of the interventions commensurated with work therapy like work simulation. It was really a wonderful time for me as an OT to be creative and look at the client's life and the kind of work that they did. I loved developing programs to help a client increase their skills and confidence to return back to work.

17. How did you become an administrator?

By my seventh year at the University of Toronto, I had worked in five different university programs as an occupational therapy educator. I could have probably spun my wheels and eventually retired as a professor emeritus from there, and that's nothing to sneeze at. That would have been a wonderful way to end a career. However, the OT in me I think thought differently. I wondered, "Is this all that I have in my tank?" I've been raised in such a way in which if I'm not giving to people and others, I'm not very happy. It's not a coincidence that the leadership philosophy that I aspire to is the one that these days is called servant leadership. I consider myself a servant leader. I decided to try and expand my capacity to make a difference in people's lives and try my hand at administrative leadership. At the time, there were lots of opportunities as there was a shortage of people to be able to serve as chairs of different programs.

I decided to take a position in Georgia, and my family and I moved to the U.S. It has been an energizing step in my life and career. Interestingly, I still find that I am doing occupational therapy. I often look through an occupational therapy lens at all of my coworkers and faculty and think, "What does your river look like right now? Where do you want to flow and how can I help you get there?"

18. What kinds of important traits must an administrator have?

I have discovered in academia that there are two streams that call for two very different skillsets. I've also found out that no one person is good at everything. Some positions involve very organized and detail oriented thinking, while others need creativity, forward thinking and a vision. Above all, I think that 95% of everything that we do in administrative leadership is about the people. If it isn't, then you're not going to have many people that are going to support you. You have to care and be a person who sees the glass is always half full. You want to be optimistic, especially when it's very difficult for people around you to be optimistic. In short, you have to be a good OT.

Reflections on OT

19. How would you define OT to a new student?

I would define occupational therapy in the form of a promise that we make to others and to society. It's a magnificent promise to enable people from all walks of life to engage and participate in activities and processes of daily living that matter. It is also complicated and difficult to deliver. In order to make good on our promises, we can't limit ourselves to understanding the embodied system or the things that are physically and functionally wrong within the self. It also entails an adaptive understanding of the environment and the relationship then between the person and the environment. If you can't, then you're not going to be a very effective occupational therapist.

Summary

20. What do you see as future trends in occupational therapy?

I came from Canada to the United States and the healthcare system here was a revelation to me. I came and I didn't even know what a copay or a deductible was. When I was at the beginning of the year, the HR department would sit down with me and they would ask, "What plan do you want to go on?" In Canada, we only had one plan so this was a new experience. Canada does not have copays and deductibles. In the US, you have to think about if you think you are going to get sick or need a procedure when picking out your plans. It just baffles me that the so-called greatest and most powerful nation on earth can't somehow reform their healthcare system. The government doesn't have to change everything. It just needs to give its citizens the assurance that if they get sick, they'll be cared for. One reason that this has been so tough is that this country has adopted over the years a system of free enterprise and capitalism that now treats healthcare as a commodity and a privilege rather than a right. So, I think one significant trend that we see is that there are hints of healthcare reform, but that debate is going to be a hot and heavy one. I think that people are also beginning to see the need for preventive care, where we're not necessarily just reacting to catastrophic problems that cost so much more money to address in the emergency room.

I think that other countries around the world have healthcare and welfare systems that are more amenable to an expanded role of occupational therapy. I know there are some Scandinavian countries have certainly been moving in that direction. I would say that if an American therapist went to some of these countries and actually looked at how OTs practice and what they did, they would be astounded. They would come away shaking their heads thinking, "There's no way that we can do that. We'd never get paid to do that."

In developing countries, OT is trying to find practical ways to help people who are impoverished and who don't have the luxury of enabling people to engage in meaningful activities. When you're growing up in developing areas, being able to engage in pleasurable activities or meaningful activities can be a far off dream. People are just trying to survive and to cope with oceveryday conditions that they find themselves in. Some OTs in those areas are working more up the policy and activism levels where they're trying to remove some of the political structures and barriers that stunt or deny them their own life development and growth.

As Mary Riley had said back in the early '70s, occupational therapy can be one of the great ideas of 20th-century medicine (the 21st century now). It is so true because the basic thrust of what occupational therapy is about is helping people deal with the consequences of the disruptions that have happened in their lives, to get back onto their feet again, and to be contributing members of society. I hope that OT will not lose sight of that broader vision as we go forward. In order to do that, I think that we need ideas and philosophical statements that encourage us to broaden and go in that much more progressive direction. I hope that the Kawa model will be an early contributor to that. The more people discover the Kawa model, the more they love it.

I would summarize my significant contributions to occupational therapy as saying it is still a work in progress. I hope that after I move on from this life, that people will appreciate that I was a person that came along that injected some new ways to move our profession forward and that my work was an impetus to occupational therapy moving to the next level, whatever that is.

Resources

Iwama, M. (2003). Toward culturally relevant epistemologies in occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57, 582-588. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.57.5.582

Citation

Iwama, M. (2020). 20Q: Kawa Model of Occupational Therapy developer. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5207. Retrieved from www.occupationaltherapy.com