Overview

- Overview of the ED

- Unique Value of OT

- Assessment Tools

- OT Interventions

- Case Studies

- Q&A

Katie: In today's lecture, we are focusing on OT's role in the emergency department. We have broken down this presentation into a general overview of the emergyency department (ED) to help those who may not have practiced in that area, as well as, we want to highlight the unique value of OT as we are thinking about patients that might be served in the emergency department. We will go over some assessment tools, interventions, and case studies.

Overview of the ED

- 145 million ED visits per year

- 12.6 million hospital admissions

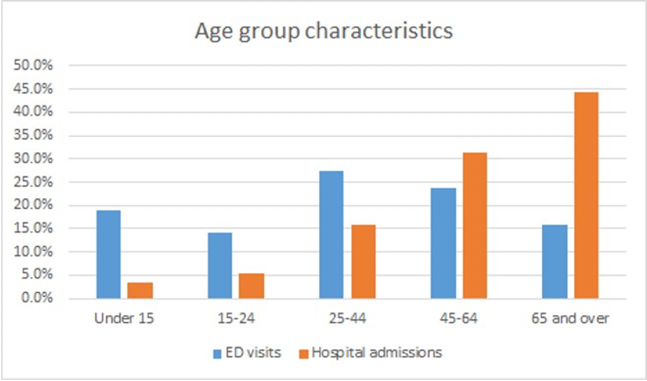

In the US, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has some great resources. Figure 1 is from 2016.

Figure 1. Age group characteristics for ED visits vs. hospital admissions (CDC, 2016).

At the last count, there were 145 million ED visits per year. This is across rural and urban populations and smaller hospitals as well as academic medical hospitals. From these 145 million ED visits per year, approximately 12 million cases result in hospital admissions. About 8% of folks that present at the ED will end up being admitted to the hospital. The CDC looks at this across age ranges. On the graph, you can see in blue the ED visits are broken down by age group as well as the hospital admissions. One thing that really jumps out at me is that the 65-and-over population accounts for the bulk of hospital admissions despite having some of the fewer ED visits. This information gives rise to the bulk of our presentation in which we will address how we can uniquely serve the older adults that might present in the ED.

In general, the most commonly diagnosed issue, based on ICD-10 criteria, is an injury. This makes up approximately 42 million of the total 145 million presentations. It is an acute change in function. And, most of the folks presenting to the ED live at home as opposed to coming from a nursing home, a facility, or homeless. The majority of patients are also females living at home alone. When we look at insurance in the ED, which we will touch upon later in terms of discharge planning, the bulk of patients presenting to the ED usually have Medicaid or state-based provided insurance (about 55 million of these ED visits). The second biggest group is private insurance, then Medicare, and the fourth biggest group has no insurance or is listed typically as self-pay. Certainly, there are some workers' comp and other unusual insurance situations that also float in through the ED. Thus, it is important to reach out to your case manager and peers in the ED to understand the kind of unique restrictions or benefits for each individual to help with discharge recommendations.

Going back to older adults, although they are not the highest population in terms of ED visits, they represent the highest population of hospital admissions. One thing to also consider is that older adults typically have longer lengths of stays in the ED, either tracked in hours or days if it is needed. They are also more likely to have repeat ED visits as compared to the other age group populations. A higher rate of adverse outcomes after ED or discharge from the ED are also reported for this cohort such as mortality, hospital admission, and return ED visits.

As the CDC has tracked ED visits over the years, they have also tracked the increasing use of the ED as frontline unplanned healthcare visits for Americans. This results in overcrowding, and evidence shows that when there is overcrowding in the ED, this leads to an increase in 30-day adverse outcomes. Again, this includes increased mortality, return ED visits either for the same complaint or a different complaint, as well as a hospital admission at a return ED visit. Vulnerable populations such as our older adults can become even more vulnerable in periods of overcrowding or popular use of ED services. Other evidence has gone as far as to look at patients that are actually admitted to the hospital during periods of ED crowding. These patients have increased hospital inpatient length of stays, higher inpatient mortality, and that ED patients discharged home during crowding have increased rates of short-term mortality in return to the ED visits requiring hospitalization. The pressure to discharge patients during periods of crowding may lead to a discharge of more vulnerable patients that would otherwise be admitted. There is a huge need to have good discharge practices during these periods of crowding in the ED to ensure safe transitions to the community whether for older adults or other populations. Thinking about the big picture and the business side in the ED, how do we best serve patients as they are moving through?

Common Diagnoses in the ED

- Musculoskeletal

- Fractures, dislocations, sprains

- Falls

- Altered Mental Status

- Failure to Thrive

- Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

The most common diagnoses that we see are due to injury and are in the musculoskeletal category. These are fractures, dislocations, and sprains. Falls certainly is another common diagnosis where OTs are consulted. Others include altered mental status, general failure to thrive at home, and mild traumatic brain injury sometimes termed concussion and often undiagnosed.

One thing to consider, especially within the altered mental status and failure to thrive categories, is that these individuals might be living with chronic diseases and trying to manage those at home. They might have difficulties with managing medications related to their chronic illness, decreased ADL performance, and decreased IADL performance. We need to screen our patients not only for cognitive and functional challenges but also for performance challenges at home. ED physicians report that cognitive impairments are the most significant barrier to providing the best emergency care.

Unique Value of OT

- In-depth functional assessment and intervention which can assist with:

- Recognizing post-discharge needs and informing discharge decisions

- Reducing the probability of future adverse health outcomes

- Avoidance of hospital admission

(Bisset, Cusick, & Lannin, 2013; Cusick, Johnson, & Bisset, 2009)

Occupational therapists are clinical experts in functional assessment and intervention for patients coming in through the ED. We look not only at the person and their physical, psychosocial, cognitive statuses, but we also look at their environment. We also look to see what occupations or activity level of participation they are trying to achieve outside of the ED. We are looking at what has been disrupted by this health event. We can help the team to recognize post-discharge needs and help to inform discharge decisions. Is there durable medical equipment (DME) that can help this individual after a fall, car crash, or another injury to be able to return safely home? Is there any patient education that is needed to help them address their new precautions? Can we provide education to a caregiver to help this client better succeed at home? And, can we refer them to community or support services? What is the safest discharge decision? Is it discharging a patient home with support? Is it advocating for admission to the hospital? What are the options available to this patient through their unique insurance, social and financial situation, their occupational needs, their environmental needs, and their person-related needs? What is the best discharge setting to help avoid future presentation to the ED, avoid admission to hospital, and help them to thrive at home? Certainly, reducing the probability of future adverse health outcomes is a huge area for OT, whether looking at medication administration and chronic disease management or general health literacy for an individual with repeat presentations to the ED. For example, someone with diabetes may present multiple times to the ED. Do they have difficulty with the management of their diabetes, a lack of access to services, or an understanding of the disease process? Perhaps, it is as simple as they cannot manage their insulin due to low vision. Can we help to modify this task for them to make them more successful?

Another goal is the avoidance of hospital admission if at all possible. It is a strain on resources, but it also can be a sentinel event for an individual if they are presenting to the ED and then admitted to the hospital to address their injury, illness, or disease. Again, this is a predictor of adverse events including future ED re-presentation and adverse post-discharge events. After the acute medical issue is addressed, we need to do an assessment of their function to address post-discharge needs. This needs to be done quickly to create a safe discharge plan for the individual and their family. This aligns with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) where they look at functional status as the result of a dynamic interaction between not only the health condition but contextual factors. As OTs, we look at the individual person and any participation restrictions like environmental factors, barriers, or facilitators to an individual's functioning in the societal roles. We are uniquely suited to address this need to assess function in the ED to help our patients have the best outcomes. How is this helpful? Let's look at some of the evidence.

The Evidence

There is a lot of research on this topic coming from the UK, Australia, and Canada, as well as some more evidence starting to come out of the US. These few studies are older but there is some good information to share.

Preventing Unnecessary Hospital Admissions: An Occupational Therapy and Social Work Service in an Accident and Emergency Department

- 209 OT referrals within a six-month period

- 79% - ADL assessment

- 61% - caregiver training

- 81.3% of patients receiving OT returned home

- 500 saved bed-days

(Carlill, Gash, & Hawkins, 2002)

This article looked at preventing unnecessary hospital admissions with an OT and social work service in an accident and emergency department. They staffed one full-time OT and a part-time social worker and tracked data over a six-month period and looked at OT referrals. They ended up getting about 209 OT referrals. Upon referral, the OT would perform an initial evaluation. This included an interview, an assessment of ADLs (dressing, mobility, transfers), and any other person-related factors like vision, cognition, and so on to determine whether or not the patient had needs for OT services. Additionally, the OT would evaluate whether the patient could benefit from a social work consult for assessment of further social and care needs, particularly based in the community. Of these 209 referrals, approximately 2/3 of them saw OT only and 1/3 of them saw both OT and social work. On average, they were about 78 years old. Again, the majority were female (152). The main reasons for a referral from providers, MDs or physician assistants, were concerns about mobility, assessment of ADLs, and concerns for the ability for the patient to cope or thrive at home. Of these patients that were referred to this pilot program, 81% of the patients were actually able to return home resulting in less than 19 that had to be admitted to the hospital for further therapy needs, discharge planning, and medical workup. Quite a few of these patients were able to return either to their own homes or to the home of a loved one. Approximately, 500 bed days were saved in the hospital which is quite a big deal. These are patients that prior to this pilot program might have been admitted to the hospital instead of returning home. This freed up space in the hospital for more critically ill patients or patients that needed more acute medical management. At the end of this pilot study, the medical providers in the ED said they felt they were able to make better decisions based on the functional info received from the OT. This led to better outcomes for the patients as well.

An Audit of Referrals to Occupational Therapy for Older Adults Attending an Accident and Emergency Department

- §1,036 OT referrals in 3 years

- §306 inappropriate hospital admissions prevented

- <1% readmission within 1-month of ED discharge

(Smith & Rees, 2004)

Another study looked at why having an OT in the ED was important and what kind of outcomes could be achieved. It was a three-year study in the UK and reviewed over a thousand OT referrals that they got during this time period. This study had one full-time OT working eight hours a day, five days a week. Referrals were triggered for this program when a patient was identified or screened to have a functional deficit or a social or environmental concern from an ED provider. The OT would then perform an assessment and establish a client-centered plan of care or discharge recommendations based on their assessment. Over this time period, they found that 92% of the referrals were over the age of 65 and a median age of around 80. The majority were found to be female and living alone. This information fits with the US-based ED information regarding common diagnoses being a fall or injury, half of which had result in some sort of fracture or injury, either an upper or lower extremity fracture or otherwise.

Again, about 80% of these patients were able to be discharged directly home from the emergency room or to a relative's home, thereby avoiding admission to the hospital. They were able to track that about 306 inappropriate hospital admissions were prevented, which based on the average length of stay for orthopedic, trauma, and medicine populations were estimated to save over 2,224 bed days over a three-year period. Again, this allowed the hospital to serve patients that truly needed acute care services. There was only a 1% readmission rate within one month of ED discharge. Not only were these patients able to avoid admission to the hospital, but they were also able to be discharged home and stay at home. This article concluded that historically patients presenting to the ED with a functional decline or inability to cope or thrive at home were often admitted to the hospital before this pilot program due to a lack of ED resources. They concluded that providing OT in the ED improved their patient care by avoiding inappropriate admissions, establishing a patient's needs within their home environment, and offering a link to community services or follow-up services to best meet that patient's functional needs and allow them to have the best outcomes as an individual.

Common Assessments

Non-standardized

- Initial Interview

- Occupational Profile

- Observation of performance of ADLs

- Home/environmental assessments

Some common assessments fall into both the non-standardized and the standardized categories. Similar to an acute setting, you want to inquire about their home setup, resources available not only from social support standpoint but DME standpoint, and any existing home health services. We want to set up an occupational profile and observe the performance of ADLs in the ED environment. The challenges with the ED environment, of course, surround the artificial nature of a busy, noisy, loud environment with a hospital bed or gurney in the room and perhaps one bathroom down the hall. Being able to observe or simulate the performance of ADLs in an artificial environment is certainly a key need as an OT practitioner. We also need to assess the patient's home environment via an interview as able.

Standardized

- Identification of Seniors at Risk

- Triage Risk Stratification Tool

- Older American Resources and Services

- Functional Status Assessment of Seniors in the Emergency Department (FSAS-ED)*

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment

*Developed specifically for use in the ED

(Bisset, Cusick, & Lannin, 2013; http://www.ot-ed.com/en/fsas-ed-tool.html)

There are standardized categories and many of these are listed above. Many of these assessments were found in the literature. While many are based on self-report, there are some that look at performance, particularly in the FAS-ED. A literature review found that the Identification of Seniors at Risk and the Triage Risk Stratification Tool were two of the more psychometrically sound assessments for screening the appropriateness of returning home. Or, is your goal more of a comprehensive understanding of functional performance? In which case the Older American Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire or the FAS-ED have a more expanded ability to look at the dimensions of functioning such as contextual factors, activities and participation, body functions, environmental factors, clinical impressions, and recommendations. The FAS-ED, developed out of Canada is now available in English, and it looks at functional status as a person's ability to perform their daily activities and fulfill their societal roles in the most satisfying way possible. One that we commonly use at our site is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment which a lot of folks are familiar with from other practice settings and is a quick standardized cognitive screen for mild cognitive impairment.

Delirium in the ED

Overview

- “An acute onset, fluctuating course, and alterations in consciousness, orientation, memory, thinking, or behavior.”

- Triggering factors

- acute pain, acute infection, immobilization, urinary retention, dehydration, and/or psychosocial factors.

- 8-17% of patients in the ED*

(Perez-Ros & Martinez-Arnau, 2019)

Lyndsay: Now that we know OT's unique value and a little bit about how to assess the patients in the ED, I want to dive a little bit deeper in terms of another aspect of our unique value as it relates to delirium. Delirium has been long studied in ICUs as well as in general acute care. There is not a ton of literature out there about delirium in the ED. However, it is quite detrimental, and I will go a little bit deeper into that.

Delirium is described as an acute onset with a fluctuating course and also has alternations in consciousness, orientation, memory, thinking, or behavior. The hallmark features of delirium are inattention and disorganized thinking, and I really want to emphasize that it is an acute onset. This differs from dementia which is a gradual progressive decline. As OT practitioners, we want to collaborate with family members or caregivers who may be present at the bedside to establish the patient's baseline cognitive functioning.

There are certain predisposing factors that put people at a higher risk for delirium. This includes over the age of 65, and any patient who may have a premorbid cognitive deficit whether it is a history of a CVA, TBI, or baseline dementia. Other predisposing factors are anyone with a sensory impairment or multiple comorbidities. Triggering factors include acute pain, acute infection, periods of immobility, urinary retention, dehydration, and/or potentially psychosocial factors. Remember, frequent utilizers of ED services are those over the age of 65, almost 50% of the cases, and often they come in with musculoskeletal injuries. They are going to be in an acute pain cycle which is a triggering factor for potential delirium. Additionally, any sort of acute infection like pneumonia, a viral upper respiratory infection, or UTI are at risk. We see a lot of patients who have a failure to thrive and may be dehydrated or malnourished due to their inability to care for themselves. They may have had long periods of immobility or reduced mobility, spending most of the day in bed or a recliner. All of these things are triggering factors of delirium that maybe other providers might not pick up on unless they are doing that in-depth occupational profile with people. We know advanced age is a big risk factor for delirium so we can anticipate potentially a higher incidence of delirium because this is a large bulk of the patient population that is seen. Based on some research, eight to 17% of patients in the ED have experienced delirium at any given time. However, it is suggested that upwards of 75% of all delirium cases go undetected by bedside clinical providers.

- Undetected delirium in the ED is correlated with higher mortality within 6 months

- Onset of delirium in ED is associated with increased morbidity and mortality

- Most common in ED stays >12hrs

(Perez-Ros & Martinez-Arnau, 2019; Kakuma et al., 2003)

Why is delirium relevant to the profession of OT? Many cases of delirium go undetected. This is associated with poor long-term cognitive functioning as well as decreased functional independence in terms of ADLs, IADLs, and mobility at the time of hospital discharge. Undetected delirium is also independently associated with increased six-month mortality. As OTs, we understand that delirium impacts somebody's ability to engage in meaningful activity and be independent. It also increases their risk of mortality which is quite profound. I think our role is pretty apparent and we need to intervene quickly and frequently.

A study by Kakuma et al. found that the mortality of patients with detected delirium as well as those who did not experience delirium was about 11 to 14% at six months after discharge. However, the mortality rate for patients, who were in the ED and the delirium was present but was not detected by the bedside provider, was upwards of 30%. That is a twofold increase in mortality. We know that detected delirium is detrimental from a functional and neurocognitive perspective, but we also know that undetected delirium carries a higher risk of mortality. We can analyze the patient cases, figure out what risk factors and triggering events might be present, and then use our role and clinical knowledge to advocate. Additionally, anybody who has been in the ED for greater than 12 hours, has a higher risk of delirium. As mentioned earlier in the presentation, the elderly population are at risk for higher utilization of ED services and have a higher length of stay in the ED, whether it is they have lack of community resources, lack of insurance, or a tough discharge disposition where it requires them to be admitted to the ED for a prolonged period of time. This puts them at increased risk. OT has a unique lens to provide some intervention in these cases.

Assessing for Delirium

The 4 A’s Test.

- Administration Time: <2min

- No training required

- 89.7% sensitivity, 91.3% specificity

- Dementia: 83.3% sensitivity, 84.1% specificity

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/543cac47e4b0388ca43554df/t/57ebb74ad482e9f4d47b414d/1475065676038/4AT_1.2_English.pdf

(Perez-Ros & Martinez-Arnau, 2019; O’Sullivan et al., 2018)

How exactly do we identify delirium within the ED? Outcome measures are very useful to demonstrate change. We know that our intervention is efficacious, but I challenge you to make sure that the outcome measure you are utilizing is appropriate. We need to make sure it is appropriate for the patient population, has strong psychometric properties (validity, specificity, sensitivity), and that it is feasible in the setting in which you are practicing. There is a myriad of different assessments that can be used for delirium. The Confusion Assessment Method is the gold standard for delirium screening within the ICU and the general acute care. However, it may not be the best for the ED because it requires training and longer administration time. It also may not be as sensitive in rapid-fire situations.

In 2018, O'Sullivan et al. studied the 4 A's Test. They found that it had good sensitivity and specificity for detecting delirium in a typical patient population as well as a decent sensitivity and specificity for a patient population with a neurocognitive disorder such as dementia. It is a very quick assessment that takes roughly two minutes or less to administer. This is absolutely essential for the ED because of the fast-paced environment. The other component is there is really no training required. There are four areas you assess and then you write down the scores and tabulate it at the bottom. It does not require any sort of formal standardization as the handout walks you through the process. There is a link to a PDF file. The first A is alertness. You will use your observation to determine whether you feel like the patient's level of alertness or affect is normal, whether they appear mildly sleepy, or if they are overtly abnormal. The second A is assessing for orientation. This is done by asking them their name, age, the date, their current place, type of location, and what year it is. The third A is attention. You will have the patient recite the months of the year backward, starting in December, and assess for how many errors they make. The last A is the question, "Is this an acute change?" As I said before, delirium is an acute onset. It differs from dementia in that it is not a gradual onset. You tabulate the scores, and anything over a three is considered to be sensitive for a potential delirium process occurring. This is a great way to be able to communicate with providers what we are finding in our sessions in a very objective and concise manner.

OT Interventions

- Discharge planning

- DME Recommendations

- Patient/Family Education

- Home modifications

- Referrals to community-based services

- UE splinting

- ADL Re-training

- Precaution Training

Once you have established the presence or absence of delirium, where do we go from here? The OT practitioner can provide client-centered interventions that either help to manage the existing delirium or help to prevent the occurrence of delirium in those patients that we know are at higher risk. Interventions that are obviously outside of our scope of practice would be the management of acute pain or infection. Physicians will be managing the medical component, but there are various triggering factors that are within our scope such as reducing immobility. Specifically, if somebody comes in with an altered mental status, there is an increased likelihood of providing restraints or some sort of restrictive component to their movement to promote patient safety and reduce falls. We can come in and assess the patient and modify the environment to help promote mobility and engagement and activity.

Through education as well as access to community resources, we can have a major impact in helping manage those psychosocial issues for patients that may be a triggering factor for their delirium. Additionally, interventions that we know have been proven to manage delirium, specifically on the acute care side, include family involvement. This is great for empowering family members through education and engagement with the patient. A lot of times when people come into the hospital, there seems to an "invisible wall" between their loved one and themselves due to the medical nature of the environment. If we can get family members engaged as quickly as possible via simple measures such as conversation, reorientation, and calming strategies (telling them a story, reading them their favorite book, or maybe putting on some music ), this can be very impactful. Healthcare providers cannot be in the room at all times, and we know that specifically in the ED as it is more fast-paced than general acute care and resources are even tighter. Family can provide these interventions to help to manage that delirium a little bit better.

Another significant way that we can help is to regulate the environment and normalize it as much as possible. This might be something as simple as regulating sensory input, putting in someone's hearing aids, or giving them their dentures or their glasses so they are able to interact within the environment. This will allow them to both hear and see the doctor that is talking to them. Oftentimes, these are overlooked due to the emergent nature of the ED. OT has a role in trying to empower the patient to be able to engage in daily tasks as normally as possible.

Engagement in basic self-care can have a huge impact on delirium management and can also tie in that mobility piece. In the ED due to time and the risk of falls, a bedpan is often the safest choice. However, for those of us who are trained in mobility and progressive activity, we know that transferring to a bedside commode has a plethora of benefits not only for neuromuscular activity tolerance but also for the cognitive piece.

I want to now segue into general OT interventions that can be provided in the ED. I look at this a little bit in terms of kind of two focuses. The first is direct benefits to the patient or caregiver. The second one is benefits to the overall health of the ED from a resource management or fiscal perspective. Our primary focus is patient safety. That is the central theme of all OT interventions. We are not necessarily providing a lot of OT treatment in the ED. Much of our care is an assessment with some treatment interventions tagged on to it. The ED is not necessarily a place where you are evaluating somebody on day one and then following up for two or three sessions. It is a one-and-done environment where we want to maximize patient safety and provide our clinical expertise so that we can set them up for safe discharge. We want to be able to provide the family, the patient, and the hospital team our recommendations as quickly as possible as to how we think the patient is going to be to interact with their current occupations in whatever environment they will be discharged to. We also want to recommend the necessary equipment. For example, if somebody had a fall in the shower and did not have a shower chair, we could recommend this piece of equipment to mitigate some of that risk. Providing education on what equipment is required as well as that equipment training is super important. Also, empowering the patient through education is vital. Examples include home modifications or education on fall risk, managing their environment, lighted hallways, and setting them up with necessary resources for home or community-based resources.

The last component of our intervention is how we affect the health of the ED. We know that expediting our discharge recommendations reduces wait times. We are also promoting patient satisfaction by reducing wait times as well as reducing the resource burden on the ED from a financial and resource management perspective. We can help providers alleviate their general census and also provide overall patient safety.

Case Scenarios

We are going to bring it all together with two case scenarios.

Maria

- Tibial Plateau Fracture

- Occupational Profile

- Independent with all ADLs/IADLs

- Working as a school teacher

- Visiting from out of state

- Interventions

- DME Training

- ADL re-training

- Caregiver education

- Orthotic training

Maria was a 52-year-old female that I worked with a couple of years ago. She was originally from Nebraska but was traveling out to Colorado over the summer for vacation. She was walking down the street and tripped over an uneven piece of sidewalk. The fall resulted in a tibial plateau fracture. Orthopedics reviewed her imaging and found that she was not in need of acute surgery so they made her non-weight-bearing in a knee immobilizer.

As you can see on her occupational profile, Maria was extremely independent prior to this incident. She worked as a school teacher and was visiting from out of state. She had good support from her husband. However, her children were off at college so it was just her and her husband. Our primary focus for Maria was optimizing ADL function and providing some caregiver training to ensure her safety so that she and her husband could travel the five hours back to their home state. We started by going over general mobility and ADL engagement with this new non-weight-bearing restriction which involved the use of a front-wheel walker for toilet and shower transfers using a shower chair. Her husband had never provided physical assistance to anybody before so we also provided a lot of education to him on how to best manage her environment to set her up for success. We also instructed in lower body dressing and managing that knee immobilizer. Lastly, we provided a lot of education in terms of community resources. We knew that they needed a few pieces of equipment to safely get from point A to point B, but there were several other pieces of equipment that were going to optimize their home safety. We educated them on how to obtain those once they were back in their local community as well as gave them ideas on how to set up home health services. As you can see, it was probably a 50/50 split in terms of hands-on training from an ADL/IADL perspective as well as orthotics management, and then another 50% dedicated to education and empowerment for her own care moving forward.

Thomas

- Generalized weakness & fall

- Occupational Profile

- Alzheimer’s

- Living with daughter, who provides supervision for ADLs and assistance for all IADLs

- Interventions

- The 4 A’s Test

- Family training

- Fall prevention education

- Resources for community-based services

Thomas was an 82-year-old man. He had experienced a short bout of the common cold which unfortunately had led to some immobility, generalized weakness, and subsequently, he experienced a fall. His daughter and caregiver brought him to the ED. There were no serious injuries, fortunately. He had a pretty decent bruise on his hip and just some generalized soreness from the fall. He also had lingering generalized weakness from the cold that he had experienced several days prior. He had a history of Alzheimer's dementia and had been living with his daughter for the past several years. She did not work and was around 24 hours a day. She provided supervision for all ADLs and provided assistance for all IADLs and transportation. He had one of the risk factors and two of the triggers for delirium. We started off right away with the 4 A's Test as we wanted to rule out any concern for delirium. Luckily, the test was negative, and we were able to utilize information from his daughter, who is around 24 hours a day, for information. She did not feel like she had noticed any changes, but we wanted to do the 4 A's Test just to be sure.

One of the things we wanted to target first was optimizing his sensory regulation. We made sure that he had his glasses on and his hearing aids in place. One of them had popped out during the fall, so being able to put that one back in gave him 100% hearing back, which was extremely important. Additionally, after our functional assessment and initial interview, we discovered that Thomas was moving decently well, but he required contact guard assistance for a little bit of decreased balance. He also required a front-wheel walker for fall prevention, which he had used previously. His daughter had never provided hands-on physical assistance before for ADLs or mobility as she was just there for supervision and some safety awareness and verbal cueing. A huge part of our intervention was providing that skilled hands-on training for this daughter to be able to adequately assist him with ADL transfers, mobility to and from ADL environments, as well as ADL performance. They did have all the recommended DME, but, again, the daughter had never physically utilized it before. We educated on fall prevention and safe transfer techniques for tub transfers as well as general transfers for ADL performance. And even though he had been diagnosed for several years with Alzheimer's, the family had not been hooked up with community resources. We provided education on family support groups and education. There is a wonderful call line through the Alzheimer's Association for resources and local chapters of the Alzheimer's Association. Lastly, we recommended some home health OT for continued rehab given his recent stint of immobility and generalized weakness to maximize his recovery. All of these interventions were done in conjunction with physical therapy. We have to utilize our interdisciplinary team members and it is definitely a group effort.

Challenges to OT in the ED

- Fast-paced

- Set-up of ED environment

- Interdisciplinary education for appropriate referrals

- Insurance barriers

To wrap it up, we know why OT is valuable. We know what we can offer and what outcomes measures we should utilize. Let's not briefly talk about potential challenges. The ED is fast-paced even more so than acute care. They want those beds turned over ASAP. Everybody is "discharge pending." We should be expediting our assessment and intervention with these patients because time is money from an insurance perspective as well as the hospital. Something that Katie had alluded to earlier is that in the ED environment many of our assessments are not applicable. We have to do the best we can with what we have, and everybody's facility will obviously differ. At our facility, we are lucky enough to be able to bring significant amounts of equipment down to the ED for different training or education with family, but the environment is not necessarily ideal. The bathrooms are down the hall, and so it may a 250-foot walk for somebody who at baseline only walked 50 feet. The elevated gurneys are also probably four feet off the ground. Somebody of a petite stature trying to do a transfer out of bed can get pretty interesting. Also, the lack of specialized equipment down there can be a barrier. Interdisciplinary education for appropriate referrals is something I am sure as OTs we experience in every setting, and the ED is no different. We want to make sure we have educated the whole team on appropriate consults and the appropriate timing. We need to build rapport through conversation and advocate for our services where appropriate. The last one is the insurance barriers. Again, these are experienced in a multitude of settings, and the ED is no different. As Katie stated earlier, the number one user of ED services are those with Medicaid. In the state of Colorado, Medicaid insurance does not provide patient access to subacute rehab benefits. Thus, being able to provide appropriate recommendations that are also feasible for the patient from an insurance standpoint is extremely valuable. The third and fourth utilizers of ED services have Medicare insurance and self-pay. Those that are self-paying may have fewer resources and may not have access to a lot of other community-based resources. From a Medicare standpoint, the ED is not inpatient so we are utilizing their Medicare Part B benefit. We need to be aware and collaborate with our care management teams to figure out what insurance these people are presenting with and then how do we best serve them with the insurance that they have available.

Questions

Can the 4 A's Test be used in environments outside the ED acute care SNF? How do you recommend educating providers on the results of an unfamiliar assessment?

The 4 A's is a delirium screen. The CAM, the Confusion Assessment Method, is the most widely researched and the gold standard, but if the 4 A's is something that you would like utilize, it has good sensitivity and specificity and it is 100% okay to utilize in environments outside of the ED. That is just the one that has been shown to have the best application for the ED. When educating providers, I give them an overview of the components of the tool. I also document any results in my note.

OT interventions seem to overlap with those that social services provide. Is that true?

Absolutely. These interventions are not done in isolation. They are done in conjunction with other interdisciplinary team members. The value of OT is being able to provide them education on resources that support their home safety in terms of ADL, IADL performance, as well as caregiver burden. That is 100% in our scope and something that we are more than capable of providing.

Can some of those services be provided from a social work perspective?

Yes, albeit they come from a different lens and from a different skill set. I think as long as we are staying true to our core value and unique value as occupational therapy practitioners, we can definitely provide those services.

Do hospitals employ OTs to work in the ER or do you go to the ED whenever they need a consult?

I can only speak to our hospital, but we have a staff of acute care therapists that service all of the inpatient including the ED. I may have one or two consults on a typical day. I would reach out to some other resources to see how they operate. We do not employ somebody specifically for the ED or house them there eight hours a day. We house all our therapists in inpatient and then float to the ED when needed.

In our hospital, they are in observation status and we discharge after the evaluation. How can they qualify for a three-day SNF stay?

In my experience, they can't. Under Medicare, they need those three midnights of inpatient status, and patients that are under observation status do not qualify. This is where we decide if this something that could be referred to an acute rehab facility if it is a qualifying diagnosis or appropriate. Or, is it a case where we have to pull in the family for family support and be able to support them from a community standpoint? I think that is an ethical struggle we face in the ED as our current healthcare system may not provide the support that patients need. Another piece that is super important to note is communicating with your care management team, whether it is social work or case management. This is because if a patient has had a qualifying hospital stay in the last 30 days or if they do have a managed Medicare, they might be able to qualify for a subacute stay, which is obviously outside of my scope. I do not have that knowledge base. I would advocate for having the care management team look in a little bit more in-depth on that.

Do you ever use a cognitive assessment such as the SLUMS?

I personally don't. The MoCA is what I use for a general screen because it has great normative data for age and level of education. The author on that is Rossetti et al. I think the SLUMS would definitely be appropriate if you feel that it would meet the needs of your patients.

Sincerely, I would like to thank everybody for hanging in with us for the last hour. It was an absolute pleasure to talk to you guys a little bit more about the unique value of OT in the emergency department. If you have any more questions, please funnel those through occupationaltherapy.com and Fawn, and she will pass those along to us. Thank you all and have a wonderful day.

References

Bisset, M., Cusick, A., & Lannin, N.A. (2013). Functional assessments utilized in emergency departments: A systematic review. Age and Ageing, 42, 163-172.

Carlill, G., Gash, E., & Hawkins, G. (2002). Preventing unnecessary hospital admissions: AN occupational therapy and social work service in an accident and emergency department. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(10), 440-445.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2016 emergency department summary tables. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2016_ed_web_tables.pdf

Clevenger, C.K., Chu, T.A., Yang, Z., & Hepburn, K.W. (2012). Clinical care of persons with dementia in the emergency department: A review of the literature and agenda for research. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60, 1742-1748.

Cusick, A., Johnson, L., Bissett, M. (2009). Occupational therapy in emergency departments: Australian practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 15, 257-265.

Functional Status Assessment of Seniors in the Emergency Department (FSAS-ED). Retrieved from http://www.ot-ed.com/en/fsas-ed-tool.html

Kakuma, R., Galbaud du Fort, G., Arsenault, L., Perrault, A., Platt, R.W., Monette, J., Moride, Y., & Wolfson, C. (2003). Delirium in older emergency department patients discharged home: Effect on survival. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 51, 443-450.

O’Sullivan, D., Brady, N., Manning, E., O’Shea, E., O’Grady, S., Regan, N., & Timmons, S. (2018). Validation of the 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test and the 4AT test for combined delirium and dementia screen in older emergency department attendees. Age and Ageing, 47, 61-68.

Perez-Ros, P. & Martinez-Arnau, F.M. (2019). Delirium assessments in older people in emergency departments. A literature review. Diseases, 7(14).

Smith, T., & Rees, V. (2004). An audit of referrals to occupational therapy for older adults attending an accident and emergency department. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67(4), 153-158.

Citation

Laxton, L. & Freeman, K. (2020). Acute care back to the basics: OT's role in the emergency department. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5166. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com