Sara: What I want to focus on today is discussing strategies to empower occupational therapy assistants to advocate for themselves, and their important role within the practice of occupational therapy. A secondary goal here is to educate any OTs that may want to learn more about how to work well and work together with occupational therapy assistants in practice.

I am an occupational therapist. I care about this topic for a few important reasons. The first one, that I think is more common than realized, is that I am ignorant. I was not aware and informed of the role of the occupational therapy assistant, and how to utilize them in practice. My first job was working in a residential treatment facility for children who had emotional and behavioral issues. I was hired to replace an OT/OTA team at the facility. I never got to interact with them. I saw a lot of co-signing on notes, but I never got to work in that team. I changed jobs a few years later and then worked in a very busy, urban university hospital, in their acute care department. There were high caseloads, and I never saw a patient more than one scheduled visit to evaluate and then recommend the next level of care. This setting did not use occupational therapy assistants either. After that, I decided I wanted to specialize in hand therapy, and I got my certification as a certified hand therapist. I moved to an outpatient orthopedic practice that only hired CHTs, so this was another missed opportunity to collaborate. Luckily, I found that I loved teaching in a classroom. I worked at several different universities in the Philadelphia area, and at one of those universities, I began to develop an OTA program. That was about eight years ago. I got the opportunity to help develop their curriculum, and then eventually started teaching some courses for the OTA program. This led to four years ago taking a full-time faculty position at the Jefferson OTA program. This is my second reason for really caring about this topic. My job is to educate future OTA practitioners and prepare them to be competent, entry-level OTAs. I want them to be able to promote themselves within the practice, and I want them to talk about their abilities and their distinct role in this OT/OTA relationship. This is why I want to talk about strategies to promote the role of the OTA. I want to educate practitioners like me who just did not know, and then empower OTAs to highlight their important role within occupational therapy.

Advocacy Strategy: Know Your History

I teach a course that is called, "The History and Philosophy of OT Practice." We discuss occupational therapy on a historical timeline, as well as, learn basic concepts about the role of the OT and the OTA and different theories and models of practice. Our profession, as you probably know, is now 100 years old. With the centennial occurring, there are a lot of resources that are emerging about the historical roots of occupational therapy, which date all the way back to World War One, the rebirth of moral treatment, and our founders, who got together and decided to formalize the profession. The birth of the occupational therapy assistant is embedded within this history, but it is not as well-known.

My first suggestion, in this class, is for OTA students to know the history. If you open a textbook, look at the AOTA website, or do a Google search, you are going to find lots of great information about the history of occupational therapy. We have a very rich and interesting history, but outside of looking at an OTA textbook, it is difficult to pinpoint and understand exactly how the profession decided to add this second layer of support personnel, and what influential OTs helped to make this happen. We know about Eleanor Clark Slagle and William Rush Dunton, and the roots of occupational therapists, but the OTA history is not as clear. Most of us do not know the names that are associated with the promotion of the occupational therapy assistant.

I did a search to see if there was anything else out there, outside of my textbooks, and I found a few articles. However, most of the articles were over 20 years old. What happened was that a little over 30 years after OT started, the assistant level was added to the profession. It was proposed at an AOTA board meeting. There was a shortage of OTs in psychiatric hospitals so it was recommended that OTA educational programs would be housed within these psychiatric hospitals and train supportive personnel.

Purpose of Assistants

- Post-WWII rush to meet the demands of medical/rehabilitation settings

- Shortage of skilled therapists in psychiatric hospitals leaving aides and technicians to fill the need

- Experienced but without formal training and in need of supervision

- Recognition of a need for support personnel or ‘assistants’ with training

(Carr, 2004; Cottrell, 2000)

After World War Two, the rehabilitation movement shifted many of the occupational therapists into more medical and rehabilitation settings. This is what left a shortage in the psychiatric hospitals, where OT was previously really valued and played an instrumental role. Aides and technicians, who had plenty of experience working alongside OTs, stepped in and started delivering services. They either modeled what the OT had been doing, or they just used trial and error methods to treat patients. What they lacked was the knowledge of interventions and clinical reasoning. They also still required supervision so this motivated some individuals to organize formal courses. This started as early back as the late 1940s. The formal education of occupational therapy assistants started in 1958. Again, this education took place in psychiatric facilities, and the first graduates came into the field as occupational therapy assistants in 1960. This was the beginning of an intra-professional collaboration within our profession. The first educational programs were 12-week courses that had didactic components. They focused on specialty skills, mostly within psychiatry. There was supervised clinical experiences, and then you could become a COTA.

Education of OTAs

- 1958: 12-week formal curriculum carried out in psychiatric facilities

- 'Grandfathering’ into becoming COTA

- 1960: a 12-week formal program to prepare for general practice

- 1966: AOTA mandate for OTA educational programs to address both psychiatry and general training

(Cottrell, 2000)

In 1958, at the same time this was going on, there was also the idea that you could be grandfathered as a COTA if you worked as an OT aide for two years and received three satisfactory recommendations from qualified individuals, including a supervising OT. Then, after three years, they decided that this probably was not the best idea, and this grandfathering process ended. Out of 460 applicants, there was 336 approvals and 336 new OTAs through this process. After a few years, again, there was a growing need for OTs to move into more indirect service roles, resulting in more help being needed in more general practice areas and in direct service delivery outside of psychiatry. So, in 1960, the AOTA Board of Management developed a new curriculum, which was focused on general practice. At this point, OTAs were either certified in general practice or psychiatry. By 1966, the AOTA mandated that all OTA educational programs were going to have this dual training, in both psychiatry and general practice, and still today, it is a general, entry-level degree. In 1961, the first directory listed 553 certified occupational therapy assistants.

Educational Settings

- Initially in psychiatric facilities

- Institution-based programs (hospitals)

- Academic institutions

- Inconsistencies in education programs until 1975

- Approved Educational Program for the Occupational Therapy Assistant

- Graduates of AOTA-approved OTA program must pass a written certification exam

(Cottrell, 2000)

Like I said, these educational settings were in psychiatric facilities. This moved into more institution-based programs within hospitals, and eventually ended up, as it is seen today, in our academic institutions. Within these early educational programs, there was some inconsistency about what was being taught and what the entry-level skills looked like. In 1975, there was the approved educational program for the occupational therapy assistant, which was published by the AOTA. You had to graduate from an AOTA-approved program, and then pass a written certification exam. This mirrors what happens today with the ACOTE and the NBCOT exam.

Founders

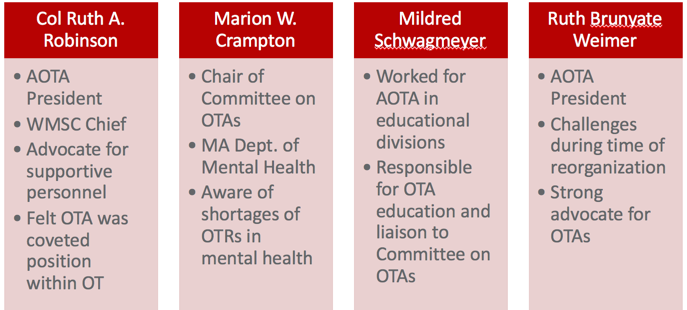

We should know the founders of occupational therapy or at least be familiar with some of the names. The founders of the assistant program are not as well know (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Founders of OTA program (Carr, 2004).

These women, all occupational therapists, had the idea that supportive OT personnel were really important. The first three women on this list were on what was called The Initial Committee on Occupational Therapy Assistants, which developed all aspects of the OTA role, such as figuring out the needs, where the educational programs should be, and what the requirements should be. They reviewed the proposals of the programs, and doing so, they did on-site reviews. They, then, approved educational programs. They understood how to appropriately use and supervise support personnel.

Colonel Ruth A. Robinson. Colonel Ruth A. Robinson was the AOTA president from 1955 to 1958, when this idea was gathering steam. She was also the chief of the OT section of the Women's Medical Specialist Corps, and then the first chief of the Women's Medical Specialist Corps. Her involvement in both the military and the AOTA made her a very fierce advocate for support personnel and OTAs. She ended up passing away in 1989, but she did an interview where she stated that she felt her greatest accomplishment to occupational therapy was the development and training of occupational therapy assistants. This made her proud, and she felt that the OTA was going to be that coveted job within the profession. The OT would be doing intake and program planning, but really the OTA was the one delivering the services. The profession that people were going to flock to and want to be within our profession. With all of the accomplishments in her career, I thought it was really interesting that her contributions to support personnel is what she thought was most important in her career.

Marion Crampton. Marion was a member of the board of management of the AOTA. She was also employed by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. She knew first-hand about these OT shortages in psychiatric hospitals. She was the chair of the committee on OTAs, and one of the neat things about her is that she made sure that all viewpoints were heard. She took into consideration things from people who were in support of occupational therapy assistant education, and also those who were not in support of it. We will more about this a little bit later.

Mildred Schwagmeyer. Mildred worked in tuberculosis hospitals until she was recruited within the AOTA to work in the educational division. At the same time, the OTA education was being developed so it became part of her job. She was extremely knowledgeable about OTA educational services. She helped to open up a discussion at the time when these programs were being developed. There were concerns about career mobility of the occupational therapy assistant, about what entry-level skills should look like, and the fact that there was a lack of OTA textbooks and teaching aids. There was also a lack of OTA faculty. Her main focus was education.

Ruth Brunyate Weimer. Ruth was not on the committee of OTA development. She was working as an OT consultant in Maryland for the department of health. And in 1964, she was the AOTA president during a time of reorganization within the AOTA. There was a rapid expansion of need for services after Medicare passed, and OT, at this time, had low visibility and recognition in health care. Even within AOTA, it was having difficulty finding its identity.

Changes Within the Profession

Once OTA's role was finalized within the profession, there was some unrest. This quote is a good representation of this, "Resistance is a natural part of any professionalization movement" (Salvatori, 2001, p.225). You are never going to see everybody buy in automatically. There was a mix of support from the occupational therapists, but there was also a feeling that they were being threatened. Professional roles were shifting within the profession, and this was within a profession that was still trying to create its own strong identity within healthcare.

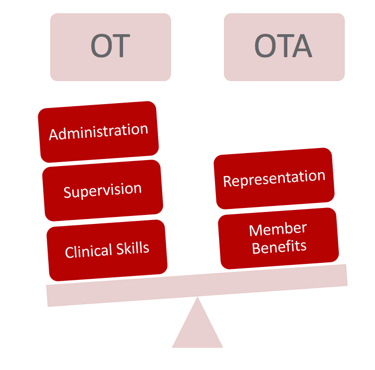

Figure 2. Shifting of roles between the OT and OTA.

Advocacy Strategy: Know Your Role in the OT Process

There was no agreement as to what the role of the OT versus the OTA looked like. OTAs sometimes even highlighted inconsistencies and weaknesses within their OT counterparts. OTs now had to be supervisors, trainers or had to take on more administrative duties. This is not a skill that everybody wanted to take on or a skill that everybody excelled in. Some OTAs were coming in with a lot of experience in the field, while others were coming into the profession as fresh graduates. Sometimes their skills or experience would shed light on, or highlight, areas of weakness within the OTs. Overall, there was a lack of defined roles at times.

There was also a lack of understanding of what supervision should look like, and which tasks should be delegated to the occupational therapy assistant. The OTAs were asking for representation. They were asking for voting rights, professional recognition, and wanted all the member benefits of the AOTA. Although the OTA was recognized by the AOTA in the late '50s, it was not until the end of the '70s that OTAs had full membership and voting rights. For example, an OTA could publish in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy before it was a member benefit for an OTA to receive the journal as a member. Through the 1980s, OTAs still had concerns about role delineation. There were concerns about salary differences, career mobility, and feeling excluded from some things within the AOTA. I feel that some of these feelings of unrest are still present within the profession. There are current issues going on in the AOTA that continue to make me feel that the role of the OTA is being devalued.

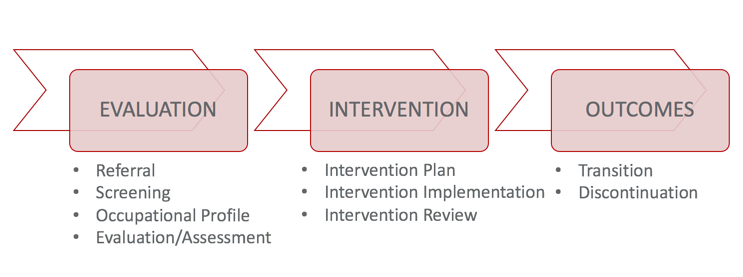

I think one of the common misconceptions is that the OTA only contributes during the intervention phase of the OT process. Many of my OTA students come into the program, and they think this as well. This information was either conveyed to them this way, or this is what they thought after looking at the literature or information on OTA programs. Also, when we send them out on their fieldwork experiences, sometimes their fieldwork educators are unsure of their role. It is so important to be educated and knowledgeable about where the OT and the OTA fit in the OT process.

The OT Process

Being able to promote the role of the OTA in practice is the next advocacy strategy. Figure 3 should look familiar, whether you are an OT or an OTA. This is the OT process.

Figure 3. The OT Process (O'Brien, 2018).