Brittany: Thank you so much for that introduction. Thank you all for joining us. I am really excited to be able to share some of this content with you today. In our session for the day, we will start out with a brief introduction to define what applied behavior analysis is. Then, we will discuss types of practice, such as massed, distributed, constant, and variable practice, and the rationale for selecting rote exercise or purposeful activities. We will discuss two types of feedback; knowledge of performance, and knowledge of results. We will also discuss positive reinforcement and how that can be applied to motor learning schedules, types of reinforcers, and how to send schedules of reinforcement over time. For applications to intervention planning, we will have some multiple choice questions and some open ended case studies. We will then end a with a brief summary with how we have achieved our course objectives and conclude with some time for questions and answers.

Introduction to ABA

As many of you may already know, motor learning refers to the process of acquiring a skill, by which the learner through practice and assimilation, refines and makes a desired movement automatic. It can also be defined as an internal neurologic process, that results in the ability to produce a new motor task. Motor learning interventions have become increasingly common in rehabilitation with the use of treadmill training and pediatric constraint induced movement therapy, which are no part of the standard of care for many patients. These interventions tend to be pretty regimented and prescribed, however, they are skills that therapists use during these motor learning interventions that have wide spread applications to many different diagnostic populations. This is what we are going to be focusing on today.

One technique, that may be particularly beneficial for occupational therapy clinicians when working children, is applied behavior analysis (ABA). Applied behavior analysis is a scientific approach for discovering environmental variables that reliably influence socially significant behavior and for developing a technology of behavior change that takes practical advantages of those discoveries. In the context of a motor learning intervention, environmental variables that you might encounter include both internal and external conditions. An environmental variable might be a sound, a visual stimulus, an object, or a sensation or emotion. The purpose of ABA is to identify environmental variables, be they internal or external, that reliably influence the behavior that you are trying to change. In this case it would be the performance of a motor based task. To develop a technology of behavior change, we collect data on the way that the environmental variables influence the performance of the behavior, and then we use that knowledge to influence the future performance of that behavior. ABA involves conditioning of voluntary, controllable behavior.

This is predicated on operant conditioning. You have an antecedent, a stimulus, that is presented. Then you have some behavior, like a child's motor response to the stimulus. Finally, you have a consequence, and that consequence will either increase or decrease the future frequency of the behavior that proceeded it. If the consequence increases the future frequency of the behavior, then it would be called a reinforcer, and if it decreases the frequency of the behavior, it would be referred to as a punishment.

Knowledge Check:

A therapist designs a treatment activity to have a child place blocks into a container to work on active release. The therapist places the container in front of the child, and the child places the block in the container. The therapist then provides verbal praise. Based on this scenario, what you would identify as the antecedent, the behavior, and the consequence.

- The antecedent in this scenario is placing the container in front of the child.

- The behavior is the child placing the block in the container.

- The consequence is verbal praise.

Types of Practice and Activity Selection

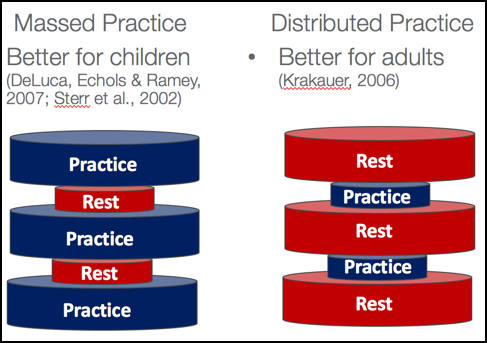

Now that we have defined ABA, we are going to focus on the way to select treatment activities to best facilitate motor learning. The amount, type, and frequency of practice directly influences motor learning. We are going to review which types of practice are the most effective to use (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Massed vs. distributed practice.

Massed and distributive practice refer to the frequency and duration of practice. In massed practice, you have many closely spaced trials. An example of this would be pediatric constraint induced movement therapy, where perhaps the child receives three hours of direct intervention every day, for 15 days or something to that effect. In contrast with the distributive process, there are more frequent rest periods that break up the time of active intervention. An example of a distributed practice schedule may be just standard of care therapy where a child receives 60 minutes of therapy, once a week. The literature tells us that massed practice is much better at facilitating motor learning in children; whereas, distributed practice is better for facilitating motor learning in adults. Variable and constant practice refer to the amount of variance that are in your treatment activities. Constant practice is drill-like with many repetitions, on the same task, over and over. This is similar to working on an assembly line, or in the context of a child, you might have them practice writing their name over and over. Or if someone were practicing gross motor skills, like in soccer, constant practice would be kicking the ball in the same exact way over and over. Variable practice, as the name suggests, randomly links other motor learning tasks together that may work on the same underlying skills. For example, if you were having a child practice writing their name, you may have them take breaks intermittently to do a maze or color a picture since those activities are also working on the foundational skill of visual motor coordination. Going back to the soccer example, they may kick the ball from different angles, or you may have them run and kick it versus having them kick the ball from a stationary position. This is trying to switch up the task.

The type of activity that you choose is also really important. As occupational therapists, we should always strive to have our activities be purposeful and meaningful to our clients, even when we are providing these motor learning interventions. Research tells us that purposeful activities are associated with higher numbers of repetition and better or equal motor outcomes than rote exercise alone. Play-based activities that you might want to use to target shoulder flexion and strengthening, for example, may be playing with magnets on a vertical surface or building with blocks and Legos, where the child has to reach up above shoulder height to retrieve each piece. If you are trying to work on shoulder strengthening, you could have the child do a scooter board maze or obstacle course. Within all of these activities, there is the opportunity for many, many repetitions. Think about the scooter board activity. How many times are they placing their hand on the ground to propel forward? With many repetitions, they are getting massed practice, which is known to be most effective for children.

Knowledge Check:

b)Distributed

c)Variable

d)Constant

Working on a 10 minute motor task, during each weekly therapy session over a one month period of time, would be an example of distributive practice schedule. Tying shoes as the only treatment activity would be an example of constant practice. Treatment, alternating between tying shoes and working on other underlying skills with play based schemes, would be an example of variable practice. And working on visual motor coordination tasks for three hours would be an example of massed practice.

Feedback and Reinforcement Mechanisms

Now that we have discussed different types of practice and activity selection, it is also important to understand how to provide feedback and reinforcement during those activities. Feedback is about giving the child information about what they are doing and how they are doing it. Feedback is absolutely critical to motor learning. There are two basic kinds of feedback, intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic feedback is the sensory perceptual information that occurs as a natural consequence of task completion. A great example is a child taking a bite of food. If you are trying to teach them pinch or grasp, and they pick up Cheerio and taste it, that provides intrinsic feedback that they have successfully completed the task. Extrinsic feedback is related to the provision of supplementary information that adds to the intrinsic feedback. Knowledge of performance is telling the child how they did. For example, you might say, "You reached so high that time," or "Good job holding your pencil with three fingers." It is describing their performance. This can be really beneficial when a specific movement component must be improved or corrected, like correcting a maladaptive movement pattern. Knowledge of results is a type of feedback that explains to the child what they have done. Knowledge of results is effective because it confirms the child's own assessment of their performance, via intrinsic feedback. It may be necessary for you to provide knowledge of results if the child is not able to determine the outcome on the basis of the intrinsic feedback alone. By telling the child the result of their performance, that can also give them some motivation to continue practicing. A study, recently comparing the effectiveness of knowledge of performance and knowledge of results for young adults that were engaging in a motor task, found that both significantly improved the individual's performance. However, knowledge of performance made more of a difference.

As we defined earlier, reinforcement is something that is provided to the child immediately after a certain behavior to increase the future frequency of that behavior. There are many different kinds of reinforcement, and that can include tangibles like a sticker, a preferred toy, or edibles, like candy or food. You could also have a social reinforcer, like verbal praise, smiling at the child, or giving the a high five or a hug. Lastly, you could have a reinforcement that is activity-based. The child might be motivated by being able to play soccer once they complete a 15 minute table task. The type of reinforcement that we are focusing on is positive reinforcement, which means that something has been added to the child's environment to increase the future frequency of the target behavior. I also wanted to mention briefly that there is also something called negative reinforcement, which means that something has been removed from the child's environment that increases the future frequency of the behavior that proceeded it. This is typically not something that we want to do. An example of this might be a really loud, obnoxious noise that is distracting to the child. Once they successfully performed the desired behavior, that obnoxious sound is terminated. Additionally though, it is important to note that taking away a task, once a child is throwing a tantrum or if they are refusing to participate, that is also negative reinforcement. When you are taking away the task demand, that increases the likelihood of future challenging behaviors when the child does not want to complete the activity. This is not to say we should not force children to engage in activities in which they are not interested, but it is important to acknowledge that by taking away the task demand, it is teaching them that if they throw a tantrum, they will not have to do something.

There are a number of different factors that affect how effective a reinforcer can be for a child. This can be the size, amount, or magnitude of the reinforcement. You want the reinforcement to be sufficient enough to strengthen the behavior that proceeded it, but you do not want it to be so big or so often, that it satiates the child where it no longer serves as an effective reinforcer. You may also want to increase the magnitude of the reinforcer for the successful completion of a more complex motor task. For example, if a child is writing a certain letter, and instead they write three letters, and make a short word, you may want to be more emphatic with your language. "Oh my goodness, that was such a great job. You wrote three whole letters." You want to increase the magnitude of the reinforcement that you are providing in relation to how challenging the task is. It is also important that the reinforcement be presented contingently. The reinforcement must depend on the occurrence of the specific movement or behavior that you are targeting. Lastly, the reinforcement needs to be provided immediately. The longer the delay between the behavior and the reinforcement, the less likely it is that the reinforcement is going to alter the future frequency of the behavior. This is partially because other behaviors might have occurred between when the behavior occurred and when you provided the reinforcement, thus you could be inadvertently reinforcing those other behaviors.

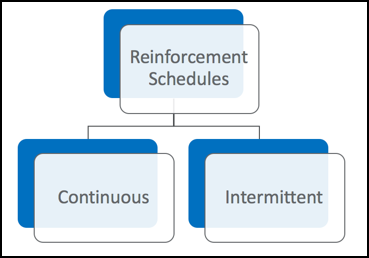

Reinforcement can be provided following different schedules. A schedule of reinforcement describes the conditions by which behaviors will produce reinforcement. Two broad categories of reinforcement schedules are continuous and intermittent.

Figure 2. Two types of reinforcement schedules.

Continuous reinforcement is when the therapist provides reinforcement every single time the behavior is performed. This is often used in the very initial stages of learning. Intermittent reinforcement is when the target behavior is reinforced some of the time. This type of reinforcement schedule is better for facilitating maintenance of a skill, and it is less likely that the child will become satiated to the reinforcer. This means that the reinforcer will continue to function.

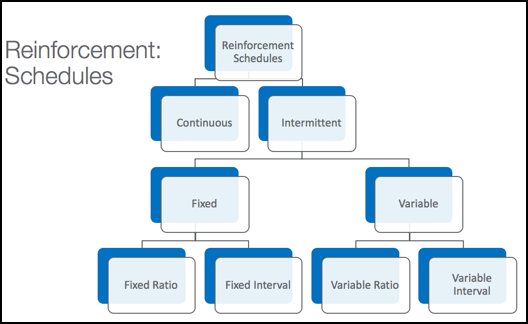

Intermittent schedules can be further classified by whether the reinforcement is provided on a fixed or a variable basis as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Types of intermittent schedules.

The reinforcement can be based on an amount of time or the number of responses. The intermittent schedules of reinforcement can be further divided into either fixed or variable schedules, and then divided even further based on whether they are a function of the amount of responses or in units of time. A fixed ratio schedule requires the completion of a constant number of responses. For example, a therapist might give reinforcement to a child after every fourth successful performance of the motor task. A variable ratio schedule, in contrast, is where the therapist would change the number of responses before the reinforcement is given. For example, a therapist may provide reinforcement after four successes, then after six successes, and finally after eight. A fixed interval schedule provides reinforcement upon the first response following a fixed duration of time, maybe after every five minutes or so; whereas, the variable interval schedule provides reinforcement on the first response, following a duration of time that fluctuates or changes.

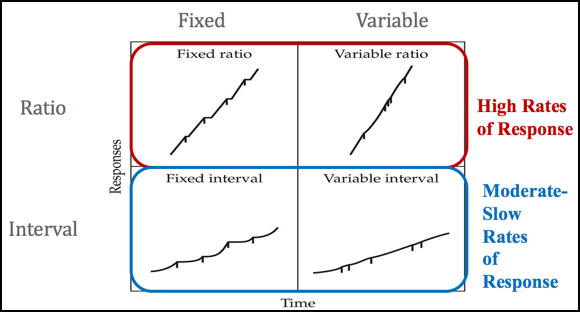

When trying to choose a reinforcement schedule, it is important to consider how the selected schedule will influence learning.

Figure 4. Results of reinforcement schedules.