Sharon: Good morning everybody. I am excited to be here today to talk to you guys about balance and outcome measures.

Balance

It is what it sounds like. It is the ability to remain upright against gravity while sitting or standing during locomotion or other kinds of transitions between positions. It is important to note that this is what balance is because what balance is not are things that we tend to call falls. Anybody who has any kind of problem maintaining that upright posture and loses the ability to do that, even in part, it is considered a fall for most researchers. And in most studies, when they are talking about falls, it is an unexpected change in your level of balance or coming to rest at a surface or object or position that was lower than you originally intended. This is important to note when we ask patients about things like balance and falls. For instance, they might drop into a chair due to poor balance or strength, but because they did it in a safe place or with something behind them, they may not report it. This could be considered a fall.

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Model

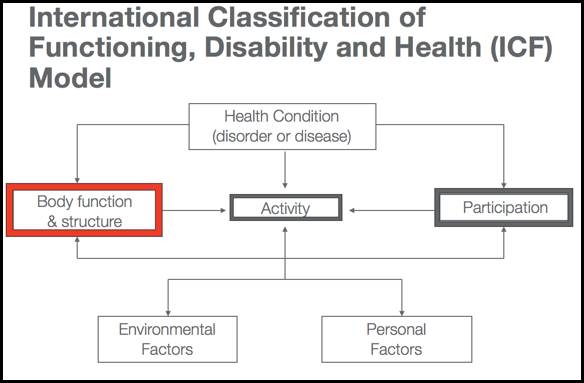

The ICF model of functioning, disability and health can help us frame health conditions.

Figure 1. ICF Model. (CDC.gov)

Physicians and sometimes nurses look at the health condition as the disorder or the disease; however, rehab therapies are usually more interested in body function and structure, activity, and participation. I want to point this out because this becomes important later when we are talking about different kinds of balance tests. Different balance outcome measures can give you information about different portions of these three boxes, and how they interact together. Obviously, activity is really important to us, and especially occupational therapists. What is the person able to do or need to be able to do in their daily life? Participation becomes important because in order to fulfill those roles that they believe they need to do to be a whole person and function in society. These are things like a worker, wife, student, or child. Balance lives under body function and structure.

Balance is a multi-factorial impairment to body functions and structures. You might have tests that look at the functionality of balance and the contributing factors that lead to a balance problem. It might look at how balance affects activity level. Are they able to walk, stand, or transfer? Do they feel they could go to church, do yard work, etc.? All of these three that rehab therapists are very concerned with are always influenced by environmental factors and personal factors, and we will talk a little bit more about those in a moment. Again, we want to understand that balance lives as its own entity as an impairment to body function and structure, but it has downstream effects on somebody's ability to perform activities and to participate.

Multi-Factorial Impairment

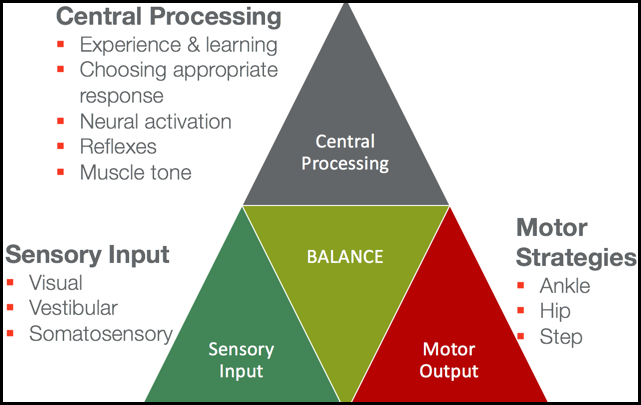

I say that balance is a multi-factorial impairment because you need a lot of different sensory inputs that all have to go through a certain amount of central processing to give you motor outputs or motor strategies. Let's go over Figure 2 in more detail.

Figure 2. Overview of balance.

Sensory Input

Balance is influenced by three primary sensory inputs: visual, vestibular, and somatosensory systems.

The visual system is usually the most important for most people. Most people use their eyes to understand how to balance themselves. So anyone who has a loss of vision, functioning in a low light, or no light situation automatically has a challenge being presented to their balance.

The vestibular system also plays a very significant role. It helps you understand where your body is oriented in relationship to gravity. If I am going to stay upright against gravity, I have to understand which direction gravity is moving on my body. If I am laying down, gravity is pushing at a different kind of orientation to my body than if I am sitting up or standing up.

Somatosensation, which really depends on what posture the person is in, is what we think of as classical balance. This is standing balance or the ability of your feet to be able to sense the floor and the ability of those foot and ankle joints to know where their position is in space. Am I a little dorsiflexed, or am I a little plantar flexed? Do I have my weight more forward towards my toes or more posterior towards my heels?

Central Processing

Those three sensory inputs then all go through central processing in your central nervous system in a variety of different areas. They are then influenced by experience and learning. People get better at balance by experiencing balance challenges. That is important when you are designing rehabilitation programs and plans of care. They need to choose an appropriate motor response, which we will get to in a minute. They need to have appropriate neural activation. And if they do not, this automatically is going to lessen their ability to balance themselves. Their reflexes need to be normal, especially when an unexpected balance challenge happens. They need to have some kind of normalization of their muscle tone. Patients, who have problems with normal muscle tone, are going to have more likelihood of having problems with balance.

Motor Outputs

There are three primary ways people move their bodies to balance in a standing position. These are somewhat true in a sitting position, but you just have to think of them a little bit differently. First of all, if you do not have a very big balance challenge, you implement an ankle strategy. Your ankles are just going to move a little bit between dorsiflexion and plantar flexion, and you have a little bit of a sway. With an ankle strategy, your hips and knees are going to stay in the same position. This is normal for small balance challenges, and we will even see those when we do things like close our eyes. With a slightly bigger perturbation to your balance, you use a hip strategy, which means that you incorporate hip flexion and hip extension to maintain your balance. It is a little bit too much for your ankle to handle so you have to start pulling in your hips and your upper body. Then last of all, the saving reflex and motor strategy for balance is taking a step. Anybody who has tripped and almost fallen down understands what a step strategy is. It could be a big step or a small step.

Different kinds of patient diseases and disorders are going to limit somebody's ability to either have normal sensory input, normal central processing. or normal motor output, all of which can affect their balance.

External Factors

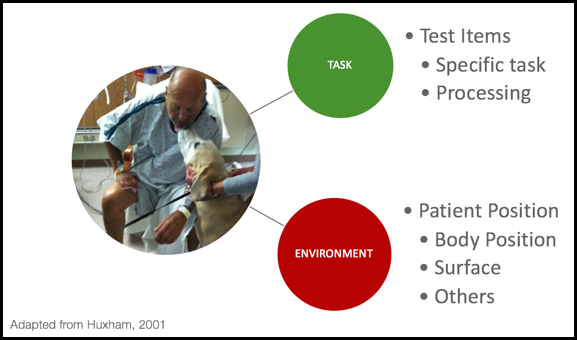

There are external factors to consider (Figure 3).

Figure 3. External factors. (Adapted from

If you think of things that are external to the patient, there could be particular things about the task that make the balance challenge increased or decreased. What is the specific task and what are the processing requirements? If somebody is taking out the garbage on a dark night, with limited vision, walking on uneven ground while holding a big garbage can, this can be a big balance challenge. It could be something about the environment itself. What is the person's body position? Are they laying down? Are they sitting? Do they have to reach?

This gentleman in the ICU has to reach over because he wants to give his dog a little kiss. Patients are going to have more stability if they sit on something that is a little more firm. Sitting on the edge of a hospital bed might be more difficult than sitting in the chair in the hospital room because of that surface. There could be other environmental factors at play. You can pretty much think of anything in the environment that could have an influence on balance.

Personal Factors

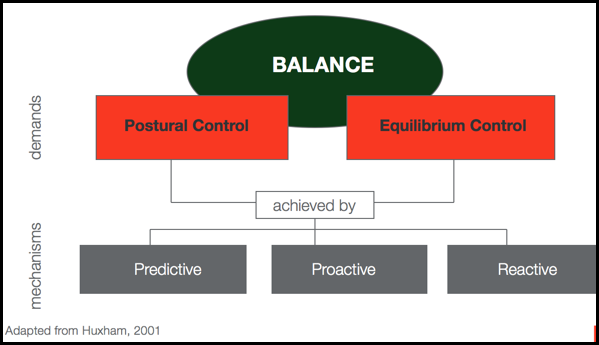

There are some personal factors that come into play with balance.

Figure 4. Overview of personal factors.

You have all of these demands of your postural and equilibrium control. You have to manage moving and being still. This is the idea of static and dynamic challenges both playing a part. These are all achieved by different mechanisms for balance. Outside of those motor strategies, we have these mechanisms that really help our body to understand how to move. For example, you see a cord on the floor while you are walking to the living room. You start to get your body ready by predicting that you are going to have to take a large step to get over that cord. You cannot shuffle your feet. It might be a proactive balance challenge where you plan on a movement. For instance, you are sitting and want to reach for your cup of coffee a little too far away. You are going to have to pre plan your postural control and equilibrium control to do that reaching maneuver. There also might be reactive mechanisms, like with unexpected balance challenges. I always like to point out that pets and small children always provide reactive balance challenges to patients because you never quite know what they are going to do. Are they going to run and grab your legs? Or is the dog or the cat going to suddenly want to go between your feet, and you are going to have to adjust your balance so you do not squash them? You have all three of those going at once.

Assessments

I want to take a little moment here and acknowledge I am not going to talk about every balance measure that exists. I am picking certain ones that fit into some categories that you can easily use, that are standardized, reliable and valid, have good intra and interrater reliability, and are all very well established in the literature. I also acknowledge that you do not have a lot of time with your patients. There is one that is a little long and we will talk about specifically, but most of them are quite short so that you can use them effectively during the limited time you might have with your patients.

Initial Considerations

- What to Measure?

- Body Functions

- Activity

- Participation

- Purpose of Measurement?

- Discriminative vs. Predictive vs. Evaluative

- Type of Measure?

- Generic vs Disease-specific

- Self-report vs Performance-based

When you are selecting a test, it is better if you can tailor it to that particular patient. As I mentioned, one test might be better at looking at body functions and impairments to those body functions, while another might be great at identifying activity and activity limitations. Any one of those things might be more important to you as a therapist with a particular patient. If you understand how each test is either very good at or not so good at identifying those areas, that can help you identify the most appropriate test(s).

There are some balance measures that are very generic and can be used with anybody. There are also some that are very disease-specific. I did not pick any today that were disease-specific because I figured you guys wanted a more general overview in this kind of course. But realize when you are looking for these in the literature, you might be able to find some that are especially good at talking about balance problems in a patient with Parkinson's disease or in a patient with multiple sclerosis.

And then there is this idea of self-report versus performance-based. It is really going to depend on how well you think you can trust the patient's self report. For some things like a participation restriction measurement, you really need to have self-report because that really gets at the core of what that person thinks about what they should be doing and the activities that they would like to be doing. That almost always is a self-report. If you are talking about more things like body functions and structures and activity, those tend to be more performance-based.

What to Measure

- Body Function/Impairment

- Correlates to activity & participation measures

- Good for short term – changes over time

- Activity/Function

- Primary concern for therapists/payers

- Participation/QOL

- Primary concern for patient/family

- May be the only thing that changes significantly

I want to point out one more thing about balance tests that look at body function and impairment. They might be good for showing short term changes over time. Things that look at activity or function might be really good for payers for insurance purposes. Participation is one of the things that we often see with balance that is the only thing that changes significantly. Maybe the patient's balance does not really change that much but their self-efficacy about their balance or their understanding of what they can do with the level of balance that they possess might change.

Purpose of the Measure

- Discriminate

- Classify patients into discrete groups

- Screen

- Classify patients into discrete groups

- Predict

- Predict outcome

- Falls, safety

- Predict outcome

- Evaluate

- Measure change over time

- Measure effectiveness of an intervention

Does a measure discriminate and classify patients into groups? Or is this more of a screening test? Does this person even have a balance problem? Something that is discriminative could tell us that. Is it something that is going to predict something? Usually, with balance tests, we are looking to predict things like falls or how safe they might be at home. Is this an evaluatative measure? Does the measure evaluate change over time and show the effectiveness of our interventions, which could be really helpful when you are setting up goals?

Cover the ICF Model

I usually recommend to try and cover the ICF model in more than one of these areas because you are going to capture different perceptions about the person's balance at different levels, and it might give you a more complete picture. Now this does not mean you have to spend your entire half an hour with the patient doing balance tests necessarily. You could do this over time, or you could pick a measure that gets at a little bit of all three.

- Multi-pronged approach best

- Impairments

- Activity limitations

- Participation restrictions

Impairment Level Examination

Impairment level examinations are looking at body function and structures, and many times they are looking at those sensory inputs.

- Examination of the 3 primary input systems

- Vision, vestibular, somatosensory

- Integration of these 3 primary input systems

- Failure to have adequate strategy reaction

- What impairments could lead to problems with strategy output?

- ROM, strength, coordination, timing

- Selected Tests

- Romberg & Sharpened Romberg

- Single Limb Stance

- mCTSIB

They are looking at how much vision, vestibular and somatosensory systems are feeding into somebody's ability to balance themselves. These are also looking at the output as far as what other kinds of problems could be complicating this balance issue. Is it that the patient does not have adequate range of motion at their ankles, and that is why they have poor motor responses and poor ankle strategy? Or is it that they are very weak and that is why they have a balance problem? Do they have a problem with their coordination or their timing? Again, it is getting at those impairment levels.

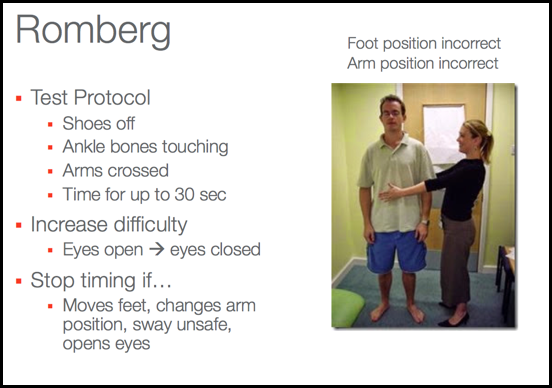

Romberg & Sharpened Romberg

Romberg is a very standard classic test. This is one of those ones that even your neurologist colleagues are probably going to do with patients.

Figure 5. Overview of the Romberg.

ut falls, it's kind of an unexpected change in your level of balance or coming to rest at a surface or object or position that was lower than you originally intended. That's important to note because when we ask patients about things like balance and falls, they might think of fall as only if you hit the ground. And they might be like well, I kind of fall all the time every time I sit because I basically just lose my balance and end up in a chair because I did it in a safe place and there was something behind me. But that actually could be considered a fall and not maintenance balance, because basically, they were letting go, couldn't stay there anymore and they happened to come to rest in something that was safe and they didn't land on the floor, but it still could be considered a fall. So I wanted to point that out. If you are at all familiar with the ICF model of functioning, disability and health, you've seen something like this before. A lot of where medicine concerns themself and physicians and sometimes nurses is on this idea of the health condition which is the disorder or the disease, however rehab therapies are usually more interested in these there metal boxes, where we talk about body structure and function, activity and participation. I wanna point this out because this becomes important later when we're talking about different kinds of balance tests, because different balance outcome measures can give you information about different portions of these three boxes and how they interact together. And obviously, activity is really important to us, and especially occupational therapists, because this is really what is the person able to do in their daily life that they need to be able to do? Participation becomes important because that's, are they able to fulfill those roles that they believe they need to do to be a whole person and function in society? So things like I'm a worker, I'm a wife, I'm a student, I am a child and I need to play. And balance actually lives under this idea of body function and structure. So technically, balance is a multi-factorial impairment to body functions and structures. So you might have tests that look really at what is the functionality of the balance, what are the contributing factors that lead to a balance problem? It might look at what does that balance do to my level of activity? Am I not able to walk, am I not able to transfer, am I not able to stand? Or it might look at how well I'm able to do those things I like to do in my life? Do I feel like I could go to church, do I feel like I could do yard work, things like that. All of these three that rehab therapists are very concerned with are always influenced by environmental factors and personal factors, and we'll talk a little bit more about those in a moment. So again, we wanna think and understand that balance lives as its own entity as an impairment to body function and structure, but it has downstream effects facts on somebody's ability to perform activities and to participate. So when you think of balance as what happening in the body, and I say it's this multi-factorial impairment, it's because you end up with, you need a lot of different sensory inputs that all have to go through a certain amount of central processing to give you these motor outputs or these motor strategies. So let's go through some of the items on the slide a little carefully so that you can understand this. So balance is influenced by three primary sensory inputs, your visual system, and that's the most important for most people. Most people really use their eyes to understand how to balance themselves. So anyone who has a loss of vision or anyone who's functioning in a low light or no light situation automatically has a challenge being presented to their balance. Vestibular system plays a very significant role in it helps you understand where your body is oriented in relationship to gravity. So if I'm gonna stay upright against gravity, I have to actually understand which direction gravity is moving on my body. If I'm laying down, gravity is pushing at a different kind of orientation to my body than if I'm...