Editor's Note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Beyond The Fear: Understanding And Addressing Fear Of Falling Avoidance Behavior, presented by John V. Rider PhD, MS, OTR/L, BCPR, MSCS, ATP.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize fear of falling avoidance behavior and the downstream biopsychosocial consequences.

- After this course, participants will be able to list adaptive and maladaptive forms of fear of falling avoidance behavior and their implications on occupational performance.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify evidence-based assessment methods and interventions to mitigate excessive fear of falling avoidance behavior.

Background

Hello, everyone. I appreciate your presence here, and I’m excited to discuss the topic of fear of falling and avoidance behavior. This has been an area of interest for me since I began practicing as an occupational therapist. Over the years, I've had the privilege of addressing this in clinical practice and conducting research across several populations.

My goal is that by the end of this session, you’ll feel more comfortable discussing the fear of falling and its impact on behavior, particularly the downstream psychosocial consequences we’ll explore. I hope you can differentiate between adaptive and maladaptive forms of fear of falling and understand how these behaviors affect occupational performance. Finally, I want to equip you with some evidence-based assessment tools and interventions to help you effectively manage excessive levels of fear of falling among your clients.

Fear of falling, and more specifically, fear of falling avoidance behavior, is a significant concern among many of the populations we work with as practitioners. High levels of this fear have been documented in older adults, individuals with neurological injuries such as cerebrovascular accidents or traumatic brain injuries, and those with neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis, among other diagnoses and injuries. It’s quite common and something we’re all likely to encounter if we work with the adult population or in any rehabilitation setting.

Moreover, fear of falling and avoidance behavior is often linked to downstream consequences, including decreased independence in activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), occupational withdrawal, and social isolation—outcomes we strive to prevent and overcome in our practice. We also know that fear of falling avoidance behavior is associated with factors we routinely evaluate and address, such as anxiety, depression, catastrophizing, self-efficacy, confidence, and even life satisfaction or quality of life. Interestingly, these behaviors can significantly impact functional independence and predict future falls more than actual balance levels in some populations.

From a clinical standpoint, the positive takeaway is that many of these variables are connected to fear of falling or avoidance behaviors and are amenable to occupational therapy treatment. This positions us uniquely and strongly to prevent and treat excessive fear of falling behaviors and, in doing so, mitigate those downstream consequences. In recent years, we’ve observed an increasing number of individuals leaving acute and inpatient rehabilitation with higher-than-expected levels of fear, which often leads to excessive avoidance behaviors. This trend is particularly concerning when we see it happening among individuals who have relatively good balance but begin to avoid meaningful activities due to this fear.

As occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs), we aim to support clients in participating at their highest possible level without instilling unnecessary or excessive fear. These are just some reasons this topic is critical for us as professionals and our client's well-being. While we’ll explore the detrimental consequences of these behaviors, the encouraging news is that they are treatable. We are uniquely equipped to address this issue through our holistic understanding of occupational performance and psychosocial factors.

Today's content is designed for practitioners with little to no experience addressing fear of falling avoidance behavior. It offers foundational knowledge and practical strategies to incorporate into your practice.

Key Concepts

I’d like to begin by defining a few key terms. While they might seem straightforward, they’re often used interchangeably in clinical practice and, unfortunately, even in the literature. This is problematic because these terms represent different constructs. We will clarify these definitions to avoid confusion, which will help us develop stronger clinical reasoning around this topic.

The first term is balance confidence. This refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to maintain balance or remain steady, and it’s typically assessed about a specific activity. For instance, how confident are they in maintaining their balance while reaching for an item on a high shelf? It’s important to note that balance confidence doesn’t address whether they think they will fall; rather, it’s focused solely on their perceived steadiness and stability. It’s often measured using a Likert or a percentage scale from zero to 100.

Next, we have fall efficacy, sometimes referred to as fall self-efficacy. This concept is slightly different from balance confidence because it involves the perceived ability to perform an activity without falling—the belief that one can engage in a task without a fall occurring. Here, the concern shifts to the possibility of falling while performing a specific task, such as walking to the mailbox or preparing a meal. It’s a subtle but critical distinction because now we’re looking at whether they perceive a fall risk, not just their general steadiness.

Finally, we have the construct of fear of falling, which is how afraid someone is that they might fall. This fear can be assessed in general or about a specific activity. Often, it’s measured simply, such as a yes or no question: “Do you experience fear of falling?” While this dichotomous approach is common in research, it’s quite limiting regarding the information we glean and the clinical decisions we can make.

Now, as you consider these three concepts—balance confidence, fall efficacy, and fear of falling—I want you to reflect on what’s missing from them. In my view, the major gap is that they overlook the impact on occupational performance and participation. This is my primary focus as an occupational therapy practitioner, and I imagine it’s yours.

This is where fear of falling avoidance behavior comes into play. This term describes a client's behavioral consequences or actions due to their fear of falling. It encompasses the extent of activity avoidance or restriction a person engages in because they’re afraid they might fall or fear the potential consequences of falling. For OTPs, this is where the heart of our work lies. We want to understand: How does the fear that my client is experiencing influence their activity selection? Are they avoiding things they need or want to do because of this fear? If so, we must determine which specific activities they’re avoiding and why.

From there, we can ask questions: Do they need to avoid these things? What does this fear look like for them? How are they deciding, “I should avoid this, but not that?” Exploring these nuances is crucial, and that’s what we’ll be delving into today—understanding these behavioral consequences and their impact on daily life.

A Vicious Cycle

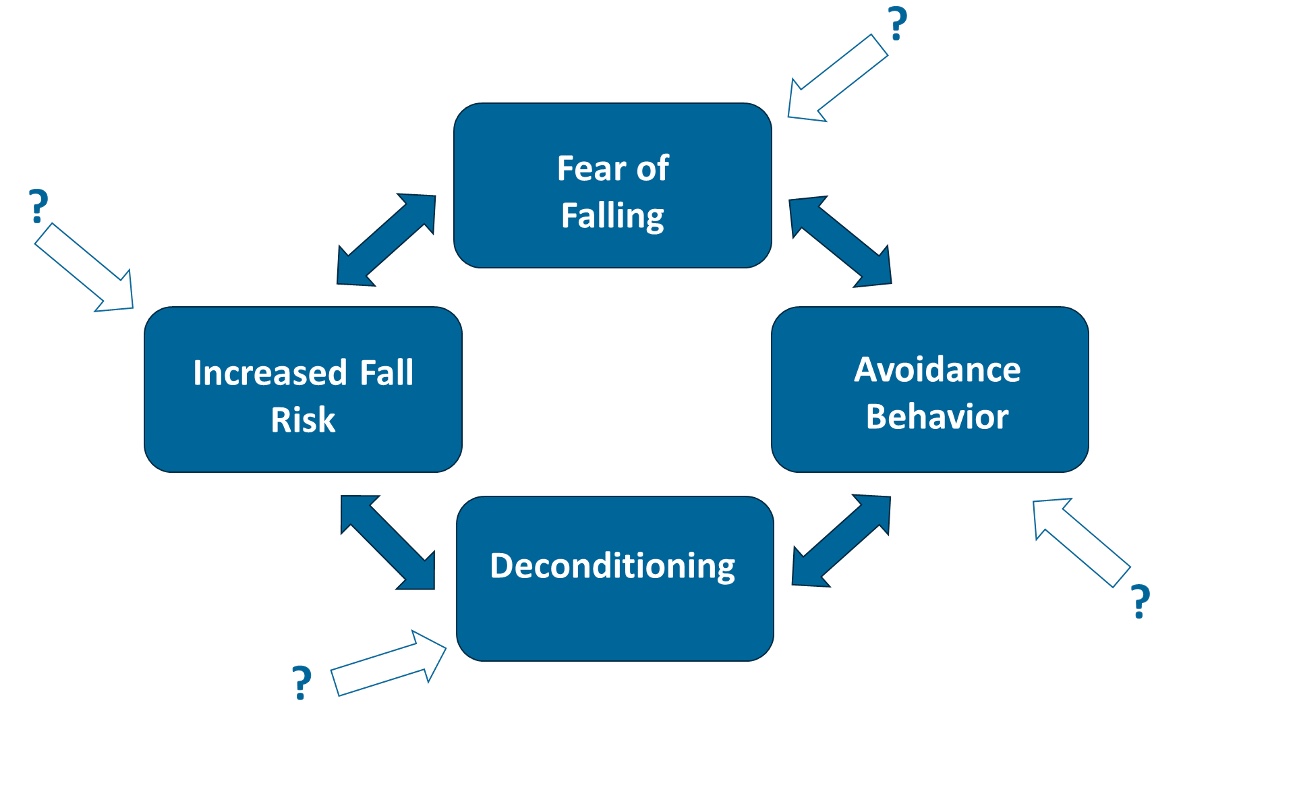

As we delve into the concept of fear of falling avoidance behavior, we begin to see a pattern. This cycle consistently emerges across multiple populations, so much so that it’s often referred to in the literature as a "vicious cycle." I didn’t come up with this term; it’s what it’s commonly called in research, and it highlights how fear-driven behaviors can become self-perpetuating. It’s important to note that this cycle can be behaviorally directional. I’ve illustrated it in Figure 1 with arrows going in both directions, acknowledging that it’s not always linear. However, as we’re just scratching the surface for today's discussion, we’ll look at it through a somewhat linear lens.

Figure 1. Fear of falling cycle (Click here to enlarge the image).

If you look at the screen, you’ll see the fear of falling at the center of this cycle. This fear can lead to avoidance behavior, resulting in physical deconditioning. As a person becomes deconditioned, their overall risk of falling increases, fueling fear and avoidance. Thus, the cycle continues. Fall risk and prevention are multifactorial, influenced by numerous environmental, psychological, physical, social, and cognitive factors. That’s why, when we aim to reduce fall risk and prevent falls, we must consider all these contributing factors and address multiple areas.

Let’s pause momentarily and consider what factors might influence each part of this cycle. Understanding these components can guide us in identifying key areas for assessment and targeting our interventions. Consider your practice and the clients you’re working with. What factors might be feeding into this cycle for them?

Let’s begin by examining the initial fear of falling. What might cause a client to develop this fear in the first place? It could be the result of a recent fall or a near miss. A new diagnosis associated with falls, such as a neurological condition, may also trigger this fear. Sometimes, even well-meaning education from healthcare providers can inadvertently instill anxiety around falls. Changes in physical status, like new-onset pain, dizziness, or vestibular changes, can contribute. Environmental factors, such as living in an unsafe or inaccessible home or navigating challenging environments in the community, may also heighten fear. Additionally, vision changes, sensory issues like peripheral neuropathy, and psychosocial factors such as new anxiety or panic attacks can all play a role.

These are all factors we should be attuned to in practice, as they may need to be addressed in our therapy sessions. When clients begin to experience fear of falling, we want to consider what might cause this fear to progress into avoidance behavior. Right now, we’re not focusing on whether the avoidance is appropriate; we’re just examining what factors might shift someone from a place of fear to a place of restriction.

Increases in anxiety or depression can amplify this fear. The literature also shows that living alone can transform fear into activity restriction, as can aging and declining health. Perceptions of one’s health are critical—sometimes even more influential than what others tell them. Catastrophizing is another factor. If you’ve ever worked with a client who tends to magnify threats, ruminate on negative outcomes, or feel helpless, you see this in action. Hearing about the falls of others—whether from a family member or healthcare provider—can also play a role, especially when those falls result in serious consequences like hospitalization, a fractured hip, or a long-term stay in a skilled nursing facility.

As clients begin to avoid activities—sometimes unnecessarily—we often see the emergence of deconditioning. This deconditioning is natural when people start doing less. It could be as simple as staying in bed longer, spending more time in a recliner, or choosing not to leave the house. When clients give up hobbies or activities that previously kept them active, deconditioning follows. It’s not just physical deconditioning, though that’s where we often focus first; it’s also psychological, social, and cognitive deconditioning. When people isolate more, their fear and anxiety compound and we may see an increase in depression.

This leads to a decreased ability to perform daily activities, reduced problem-solving skills, and diminished executive functioning. We, as occupational therapy practitioners, understand what happens when someone stops being active and disengages from things that are important to them. This is what we mean by the deconditioning component of the cycle.

As clients decondition, they often recognize these changes in themselves. They notice the physical losses—decreased strength, range of motion, balance, and endurance—and the psychological changes, like declining confidence and judgment. With this realization, additional fall risk factors emerge, and clients may feel even more vulnerable. This awareness can push them deeper into the cycle, with more fear, avoidance, and deconditioning.

Hopefully, you can see how these downstream consequences create a spiral, with different clients getting caught at various points. Depending on the setting and the specific situation, we may need to address any of these factors to help clients break free from the cycle. So far, I’ve focused on the negative aspects of fear of falling and avoidance behavior, but I want you to pause and consider for a moment: are there any potential benefits?

Would we ever want a client to have some level of fear of falling or to exhibit a certain amount of avoidance behavior? After all, everyone has some risk, myself included. Perhaps a degree of caution is protective, guiding us to avoid truly hazardous situations. So, the key is finding the balance—understanding when fear drives clients to restrict their lives unnecessarily and when it might serve a purpose. We’ll explore that further today as we work through strategies to intervene effectively.

What Are the Benefits of FOF or FFAB?

Everyone can probably agree that a certain level of fear and avoidance behavior can be beneficial. When managing fear of falling and avoidance behavior, recognizing that it can be a sound strategy when it appropriately matches the individual’s capabilities. In other words, when the amount of fear or avoidance behavior is proportional to what the person can or cannot do safely, or when the activity in question is inherently dangerous or carries a high level of risk, it may be a good decision to avoid it.

For example, if a client decides to avoid walking down a steep driveway with loose gravel without assistance because they know their balance changes and slower reaction time following a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), that’s likely an appropriate response. Similarly, choosing not to walk to the mailbox when the sidewalk is covered in ice on a windy day is a wise decision. In these cases, the fear is aligned with the person’s capabilities and the situational risk, reflecting an appropriate and protective level of caution.

Sometimes, we are more concerned about clients who don’t fear falling or avoidance behaviors, particularly when they have notable impairments. The absence of fear or avoidance can be problematic because it might indicate poor insight into their limitations, leading to risky behaviors. On the other hand, we also don’t want clients starting to isolate themselves or significantly decrease their activity levels due to excessive fear, especially when it’s unwarranted.

From a clinical standpoint, it’s crucial to differentiate between when fear and avoidance behaviors are appropriate versus when they are disproportionate to the actual risk. When these behaviors match the individual’s capabilities, it can signify increased awareness, good judgment, and appropriate mental planning. That’s why we can’t automatically assume that any level of fear or avoidance is always detrimental.

It’s essential to explore the client’s rationale behind their fear and avoidance behaviors. We must dig deeper into their physiological fall risk, perceived risk, and perceptions of their abilities. Then, we must look at the specific activities they are avoiding and use our clinical findings to determine if their behavior is appropriate or if a sign of excessive fear needs to be addressed. By doing so, we can help our clients balance caution and meaningful engagement in daily activities.

Fear of falling avoidance behavior can be:

We also want to empower our clients to develop a framework that helps them determine the appropriateness of different activities. Since we won’t always be there to guide their decisions, it’s crucial that they have strategies in place to assess their capabilities and safety. There are many ways of describing the fear of falling and avoidance behaviors, with various terms used in the literature and clinical documentation. The main takeaway is that not all fear of falling avoidance behavior is inherently good or bad; the context and alignment with the individual’s abilities matter.

For OTPs, this requires clinical reasoning and a thorough evaluation to determine if the behavior is adaptive, protective, and appropriate—terms that suggest it’s beneficial and the right level of fear and avoidance. Alternatively, is it maladaptive, excessive, or inappropriate? Making this distinction is crucial in guiding our interventions effectively.

One challenge is that no single assessment tool can definitively tell whether a client’s fear of falling and avoidance behavior is appropriate or inappropriate. While having such a tool would be ideal, the absence of a singular measure means that our clinical reasoning skills are essential. This is where our unique background as occupational therapy practitioners becomes valuable—evaluating all these factors and using objective measures and subjective insights to decide what is appropriate for each client.

However, this also means that our evaluations must be comprehensive, including the biopsychosocial factors that truly influence fall risk and fear of falling. This requires thorough interviews, understanding the client’s occupational profile, and delving into their thought patterns and perceptions. By considering all of this, we can better identify the type of fear and avoidance behavior our client is exhibiting and, if needed, develop targeted strategies to help them.

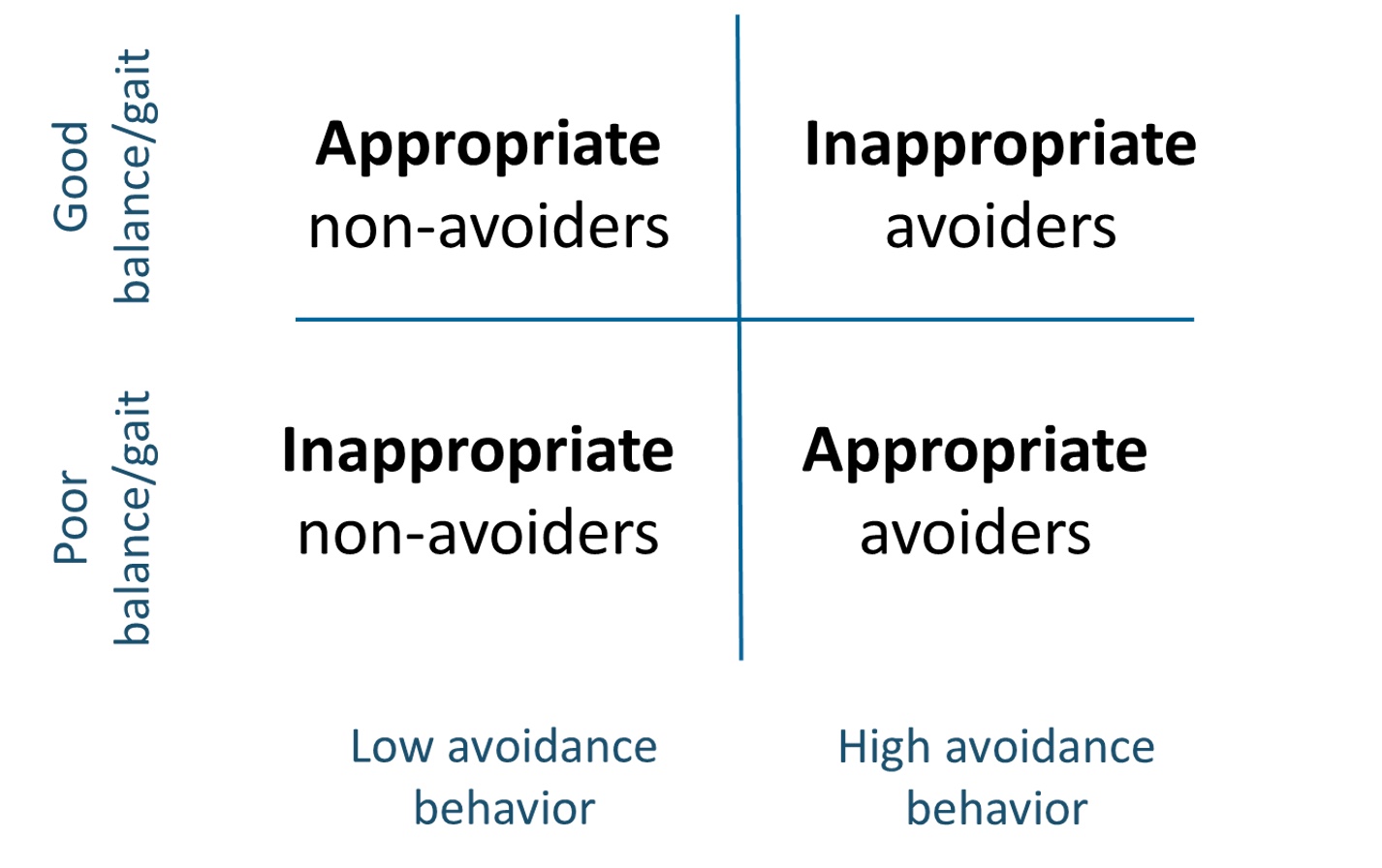

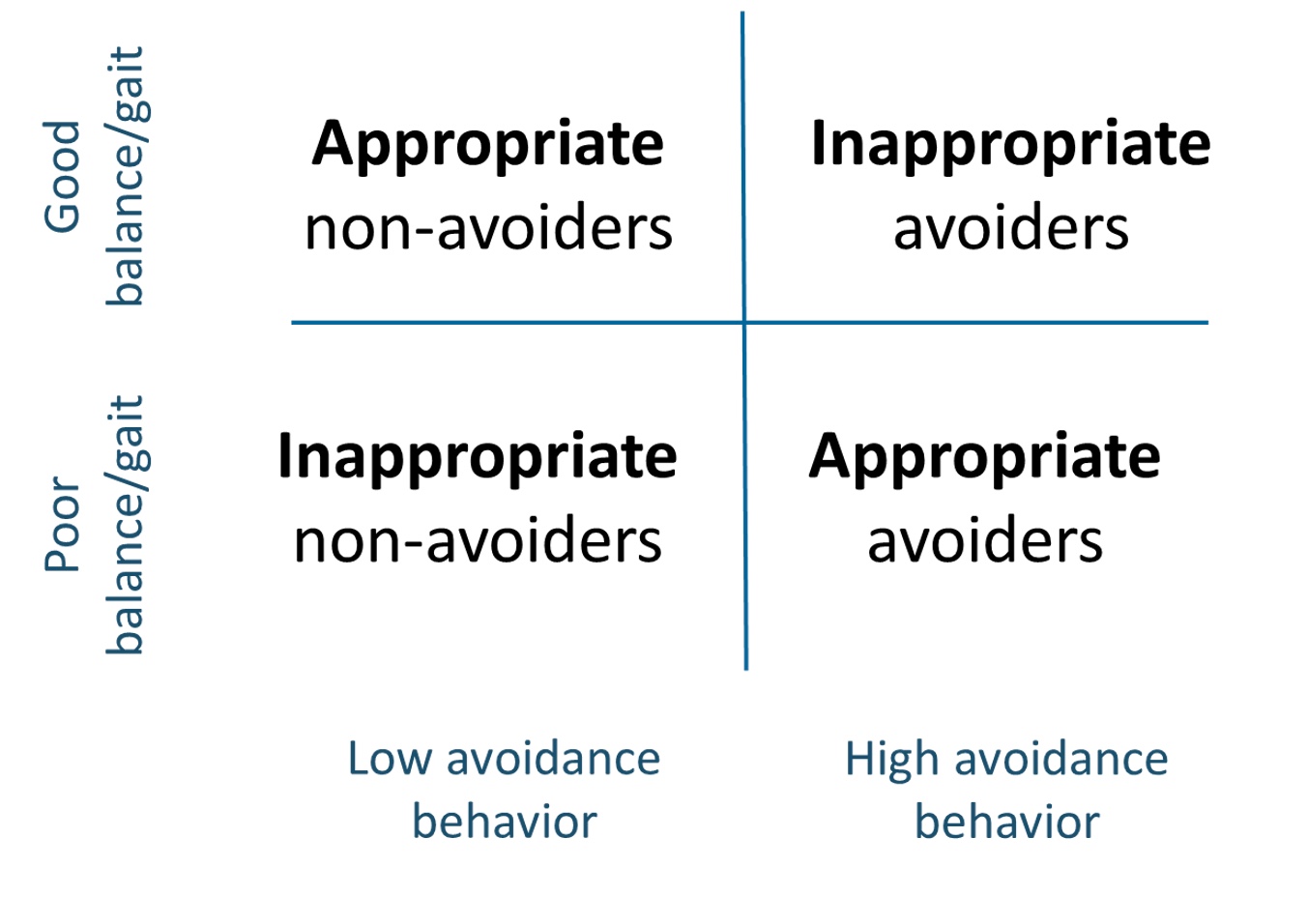

While no single assessment tells us everything we need to know, there is a framework that can guide us in determining whether fear of falling avoidance behavior is appropriate or excessive. I’ve used this framework in various ways—both with clients in a simplified form and when teaching other practitioners how to approach this issue. I’ve found it helpful to frame our thinking using a visual representation, breaking down behavior into specific quadrants.

If we look at the visual framework in Figure 2, we see a vertical axis labeled “balance and gait,” ranging from poor to good, representing the individual’s physiological fall risk. On the horizontal axis, we have avoidance behavior, ranging from low or minimal to high or excessive.

Figure 2. Visual framework for fear of falling avoidance behavior (Click here to enlarge the image).

This framework allows us to categorize individuals into four types of responses: appropriate non-avoiders, inappropriate non-avoiders, appropriate avoiders, and inappropriate avoiders.

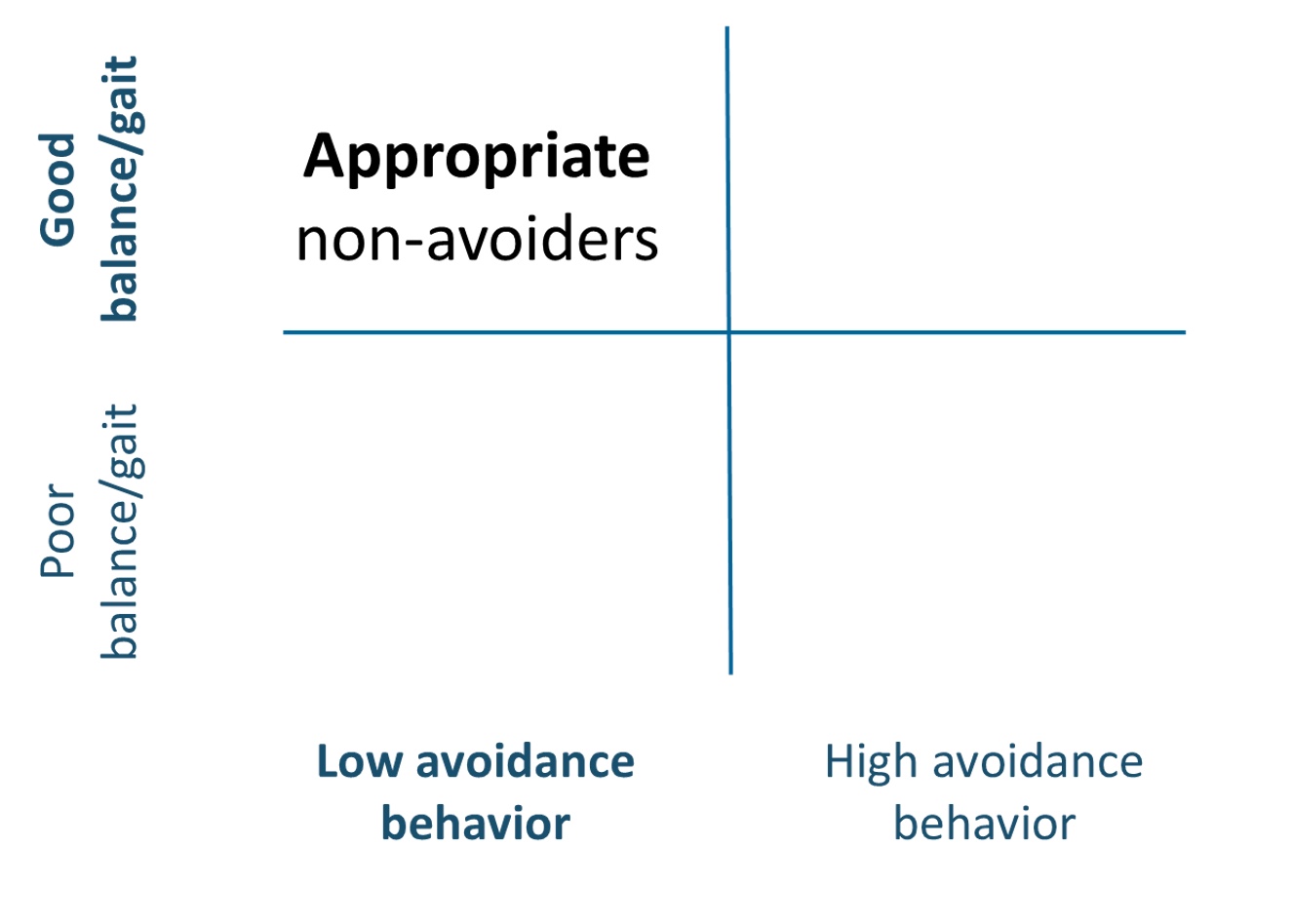

Let’s now walk through each quadrant. In the first quadrant (Figure 3), we have individuals with good balance and gait, meaning they have a low physiological fall risk and demonstrate low avoidance behavior.

Figure 3. Appropriate non-avoiders quadrant (Click here to enlarge the image).

Their level of fear and avoidance behavior matches their capabilities, making them what we would call appropriate non-avoiders. They are not excessively avoiding activities because they don’t need to. These individuals are probably not the ones we’re seeing for concerns about fear of falling or avoidance behavior, and they may not even be our typical clients for other areas of occupational therapy.

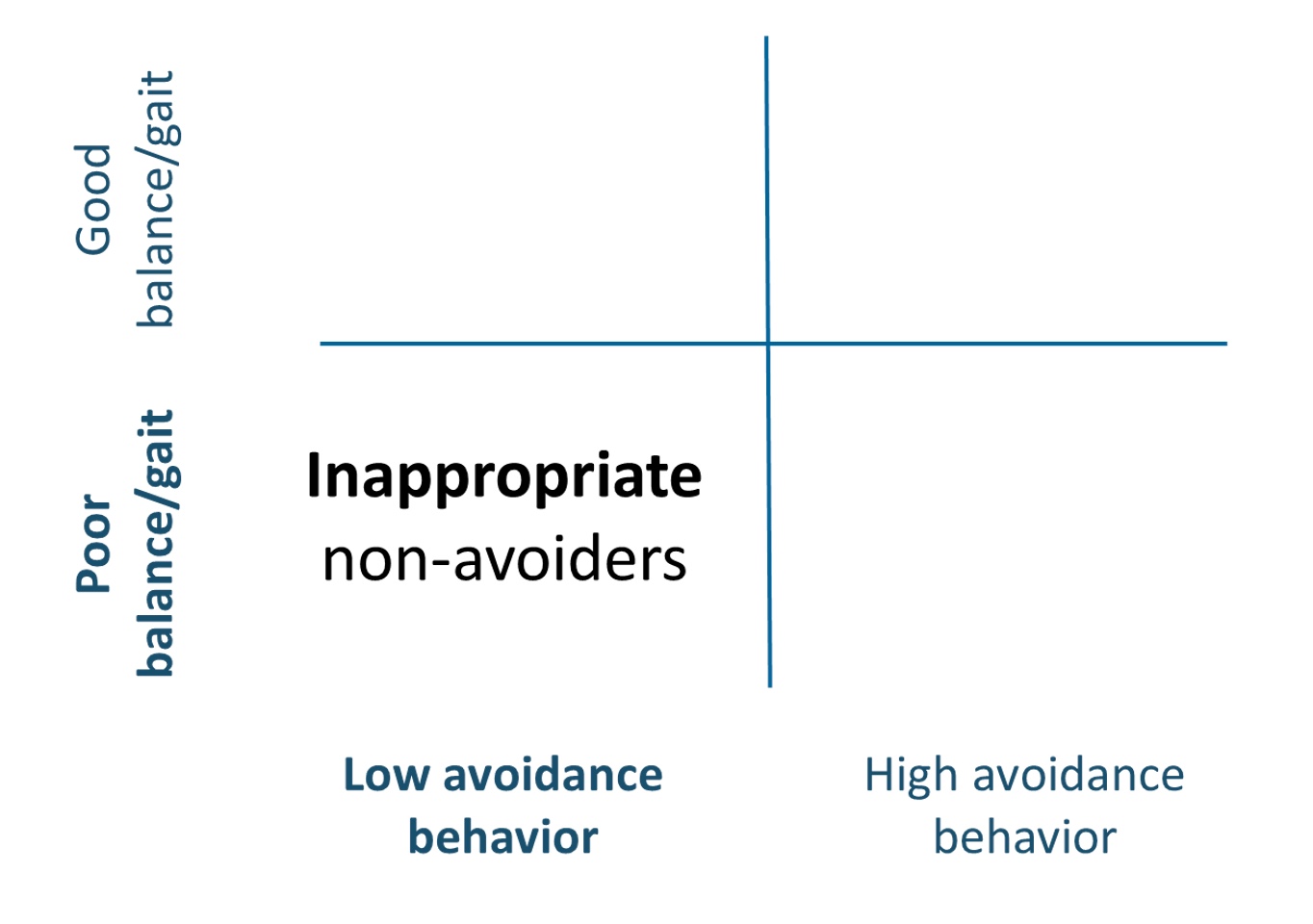

Moving down to the second quadrant, we see individuals with poor balance and gait, indicating a high physiological fall risk but demonstrating low avoidance behavior (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Inappropriate non-avoiders quadrant (Click here to enlarge the image).

This would be a concern because their avoidance behavior does not align with their capabilities, making them inappropriate non-avoiders. In other words, they’re not avoiding activities, but they probably should be due to their high fall risk. These are often the clients we see following neurological injuries like CVA or TBI. With this group, we might need to focus on improving cognitive-perceptual skills and safety awareness until their fall risk decreases.

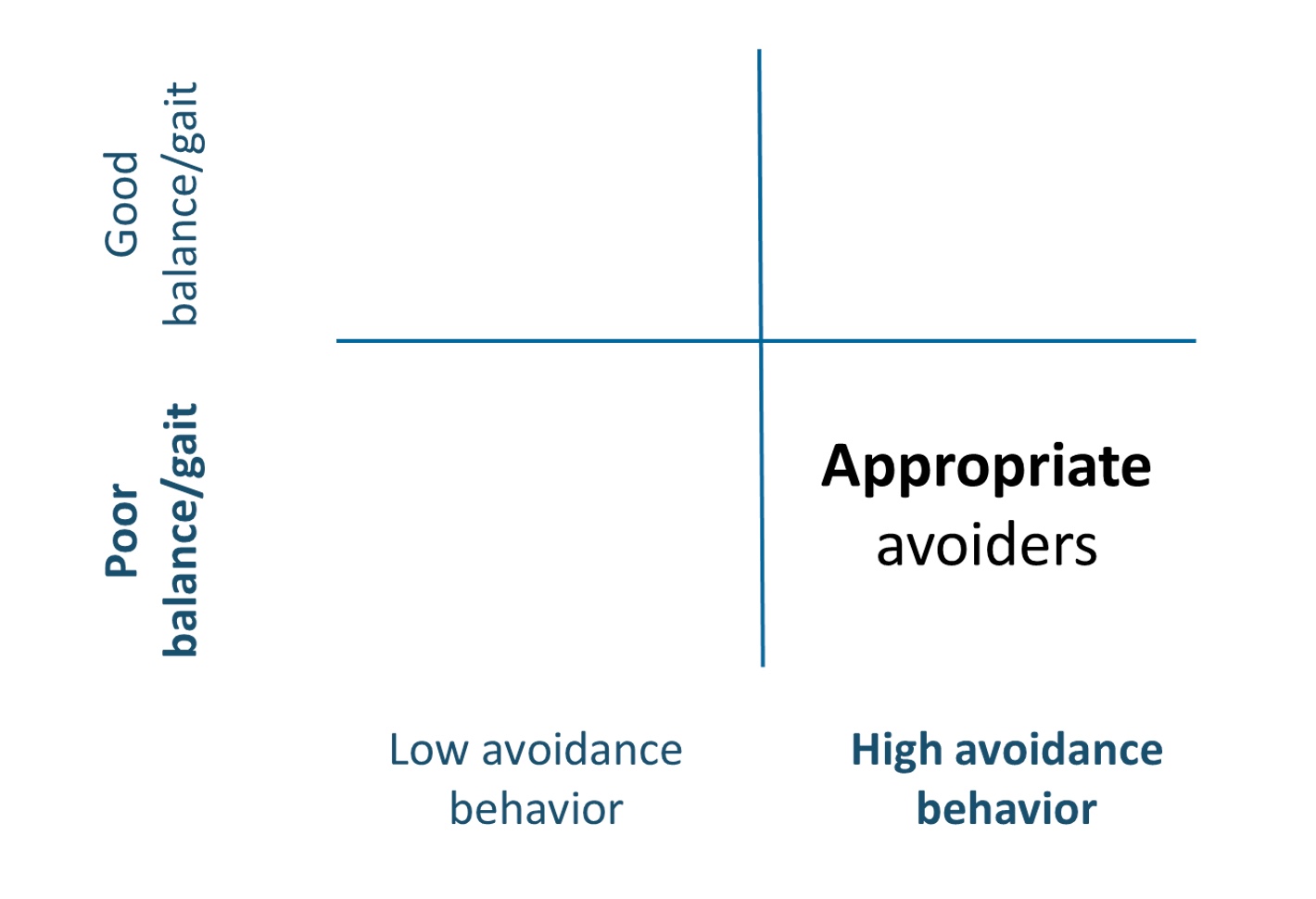

In Figure 5, the third quadrant includes individuals with poor balance and gait (high fall risk) exhibiting high levels of avoidance behavior.

Figure 5. Appropriate avoiders quadrant (Click here to enlarge the image).

In this case, the high avoidance is appropriate, as it matches their capabilities, so we refer to them as appropriate avoiders. For these clients, our intervention would focus on addressing the underlying fall risk factors—such as balance, strength, endurance, or environmental risks—while carefully monitoring that their avoidance behavior decreases as their fall risk decreases.

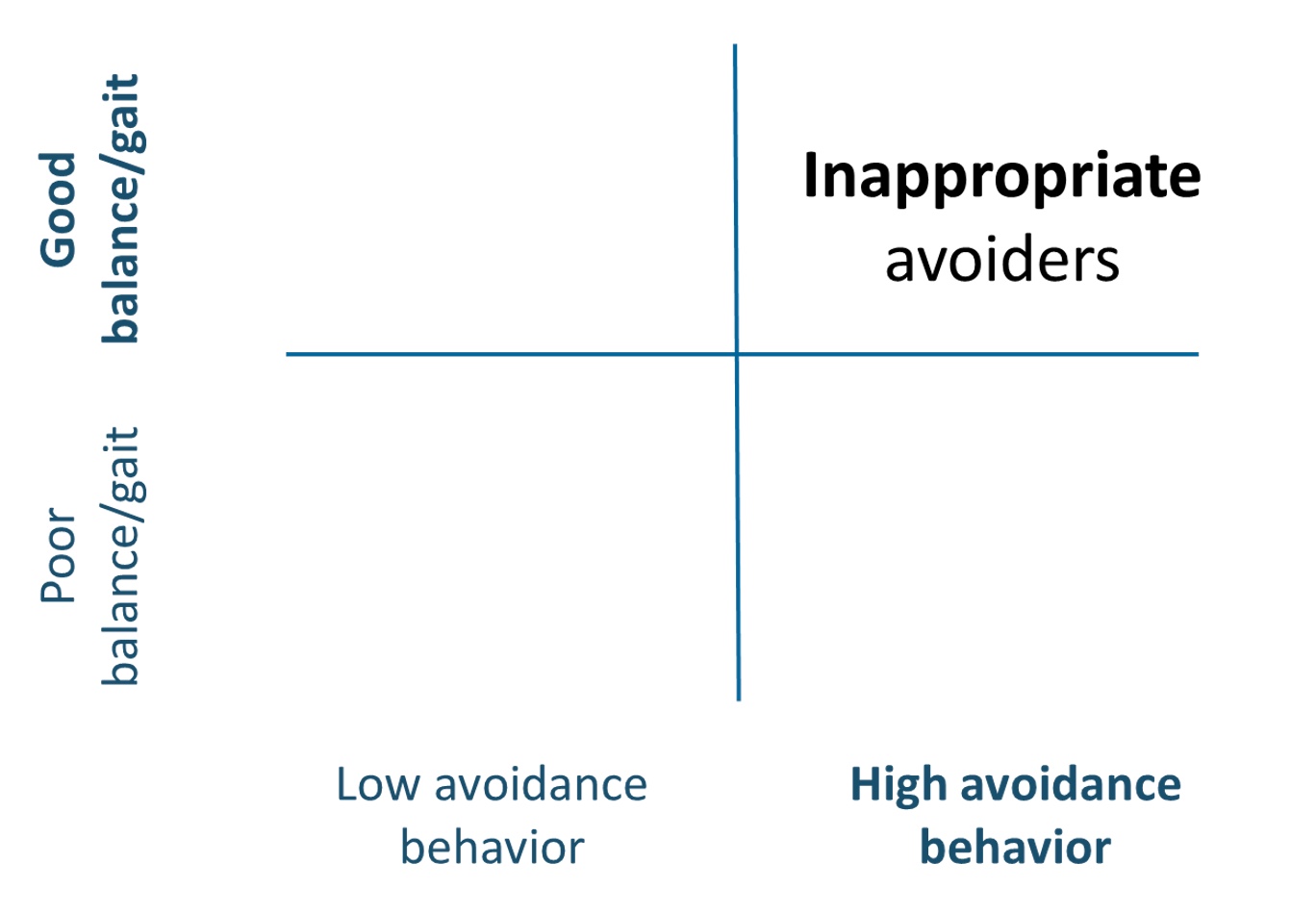

Finally, our main concern today lies in the last quadrant—individuals with good balance and gait (low physiological fall risk) who demonstrate high levels of avoidance behavior (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Inappropriate avoiders quadrant (Click here to enlarge the image).

We call them inappropriate avoiders. Their high avoidance behavior doesn’t match their capabilities, making it a behavioral concern. These clients risk getting caught in that vicious cycle we discussed earlier, which can lead to further deconditioning and, eventually, a decline in function.

Addressing these clients is challenging for OTPs because it requires us to go beyond traditional fall risk factors like gait, balance, and physical concerns. If we don’t address this, we’ll likely see long-term negative consequences that impact all aspects of their lives. Even though they may not have a high fall risk right now, if they continue to engage in high levels of avoidance, they will eventually experience physical and psychological decline, leading to a higher fall risk and decreased overall function.

As we revisit this framework (Figure 7), I hope it provides a useful visual and guide for thinking through your evaluations.

Figure 7. Visual framework for fear of falling avoidance behavior (Click here to enlarge the image).

Consider your clients’ physiological fall risk—based on client factors, standardized tests, and observations. Then, compare that to their perceived risk and avoidance behavior. Are they responding appropriately or inappropriately to their capabilities and actual risk?

This distinction is important because, even today, clinicians treat avoidance behavior as if it’s always negative or instill too much fear through education and recommendations. This framework can help us avoid common clinical practice mistakes and ensure our interventions are tailored to each individual's needs.

Assessments

Let’s look at some assessments we typically use to evaluate fear of falling and avoidance behavior. These have been shown to have moderate to strong psychometric properties, so the focus shouldn’t be on which one is more valid or reliable. Instead, we want to consider what you want to measure and how that information can support your client.

I’ve organized these assessments into two categories. We have those measuring fear of falling, primarily focused on constructs like balance confidence, self-efficacy, and perceived consequences. Next, some assessments specifically measure fear of falling avoidance behavior, focusing on clients' actions based on their fear. The reason for this separation is to emphasize that while the tools on the left can provide valuable information, they don’t capture the behavioral consequences—the actual avoidance behaviors—that we’re particularly interested in.

Assessments Measuring Fear of Falling

Let’s start with the Falls Efficacy Scale (FES), a tool many of you may be familiar with if you work with adult populations. The FES measures fear of falling or, more accurately, the level of concern about falling during everyday activities using a Likert scale. It looks at specific activities, and a higher score indicates greater concern. There are various versions of this scale, including an international version, which is quite versatile.

Next, we have the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale, a common tool often taught in OT programs. The ABC measures balance confidence in performing different activities without losing balance or experiencing a sense of unsteadiness. Clients are asked to rate their confidence on a scale from 0 (no confidence) to 100 (complete confidence).

Another interesting tool is the Consequences of Falling Scale. This scale measures the perceived consequences of falling, divided into functional independence and social consequences, including damage to identity. It asks questions like, “If I fall, I might lose my independence,” or “If I fall, I might feel embarrassed or become disabled.” Clients respond using a Likert scale. While these assessments are valuable, they only capture the cognitive aspects—clients’ thoughts and beliefs about falling—without addressing the behavioral consequences or actions taken due to these beliefs.

Assessments Measuring Fear of Falling Avoidance Behavior

Moving over to the assessments on the right, we have tools that measure the behavioral consequences, such as fear of falling and avoidance behavior. One prominent tool is the Modified Fear of Falling Avoidance Behavior Questionnaire. It’s a mouthful, but it’s a well-established measure. Originally, there was a non-modified version, but the author revised the wording after research showed it was challenging for clients to understand. The modified version asks questions like, “Due to my fear of falling, I avoid...” followed by various recreational and leisure activities, meal preparation, or walking in crowded places. Clients respond with options ranging from never, rarely, sometimes, often, or always, or they can use a percentage value. The tool is freely available online, and I’ve found it invaluable in practice. It’s a great conversation starter and provides concrete data on the client’s activity patterns and avoidance behaviors.

Another option is the Survey of Activities and Fear of Falling in the Elderly (SAFE), specifically designed and validated for older adults. This tool helps differentiate between fear of falling and avoidance behavior, asking clients to indicate whether they would “never,” “sometimes,” or “always” avoid specific activities. It’s an effective tool if you primarily work with older adult populations.

Using Assessments in Practice

The key takeaway is using these assessments to facilitate client conversations. Even if you don’t administer the entire questionnaire, you can borrow language or specific questions to guide your discussions and understand the client’s thoughts and behavior patterns. Ultimately, we want to identify: Does my client have these thoughts? Are they avoiding activities? If so, is it appropriate or inappropriate?

For those new to discussing these concepts with clients, using these structured assessments or examining their language can help you feel more comfortable and confident in your approach.

Key Points and Common Pitfalls

I also want to highlight some key points and common pitfalls that I see coming up frequently in practice. This first one is so often overlooked that it warrants discussion: We cannot postpone discussing the fear of falling or avoidance behavior until a client has experienced a fall. We can’t assume that these behaviors only arise after a fall. In reality, many individuals—especially older adults or those with neurological or neurodegenerative conditions—develop a paralyzing fear of falling without ever having experienced an actual fall.

Many of the publications in this field include a call to action for healthcare providers, urging us to screen all clients for fear of falling avoidance behavior, not just those who have had a fall. While it may not always be feasible to administer a full assessment, a simple question like, “Are you avoiding any activities because of a fear of falling?” can open up the conversation and create an environment where the client feels safe sharing that information. This approach is critical for any of our clients who may be at risk, and it could help us prevent long-term consequences and start addressing concerns early on.

The Role of Anxiety, Depression, and Catastrophizing

Another key point I want to emphasize is the role of anxiety. Anxiety is a strong predictor of fear of falling and avoidance behavior. We need to be comfortable discussing and addressing anxiety with our clients because higher levels of anxiety are associated with increased avoidance and a greater likelihood of future falls. Depression and catastrophizing thoughts are also associated with avoidance behavior, though not as consistently as anxiety. However, catastrophizing—when clients magnify threats, ruminate on worst-case scenarios, and feel a sense of helplessness—has been strongly linked to avoidance behavior patterns and is often interrelated with anxiety.

As OTPs, it’s vital that we consider the impact of these thoughts and beliefs. Helping clients explore these cognitive patterns, problem-solve, and work through different scenarios will allow us to support them more effectively in breaking the cycle of fear and avoidance. By addressing both the physical and psychological factors, we can help our clients build confidence and re-engage in activities that are meaningful and important to them.

Intervention Approaches

As OTPs, we are uniquely positioned to comprehensively address fear of falling and avoidance behaviors. I genuinely believe that we are one of the few professions that consistently consider this aspect of fall prevention. We need to approach it thoughtfully, document our findings clearly, and develop strategies that address these behaviors effectively.

When it comes to psychological factors such as anxiety, fear, worry, and catastrophizing, addressing these concerns early in the rehabilitation process can prevent the development of excessive or inappropriate fear of falling avoidance behavior. By doing so, we can potentially circumvent those downstream consequences we talked about earlier and keep clients from getting stuck in that vicious cycle. Many of us, even with just a few years of experience, could probably share countless stories of clients underestimating or overestimating their actual fall risk. We see it all the time—clients who either believe they are at no risk and take dangerous chances or, conversely, avoid activities altogether due to fear.

Perceptions are deeply tied to avoidance behaviors, making it crucial to assess not just physical risk but also perceived risk of falling. For instance, after completing some balance testing, you might have a conversation with a client and say, “You mentioned that you’ve been avoiding a lot of activities because you don’t think your balance is good, or you’re afraid you might fall. However, based on the results of these tests, you’re actually scoring in the low fall risk category. What do you think about that? How does that make you feel?” This opens the door for a deeper discussion and allows us to explore how they interpret this information and if it changes their thoughts about what they can safely do.

A follow-up question might be, “Are there activities that you think you could be doing safely but are currently avoiding? What activities would you like to try again?” These conversations help uncover gaps between the client’s actual abilities and their perceived abilities, which is where we, as practitioners, can make a real impact. One of my favorite strategies is to ask clients to walk me through their thought process: “Can you explain to me how you decide what is safe or unsafe for you to do? What goes through your mind when you’re faced with an activity that makes you nervous?”

These discussions are invaluable in helping clients build better awareness of their capabilities and limitations. We often complete standardized assessments, but we don’t always relay the results in a way that clients can easily understand or relate to their everyday lives. It’s important to take time to not just share the findings but to ask what those results mean to them: “How does this make you feel? Do you have any other questions?” Engaging in this back-and-forth conversation helps us bridge the gap between objective data and subjective experience, allowing us to tailor our interventions more meaningfully.

We must focus on intrinsic and extrinsic factors to address the fear of falling and avoidance behavior. This means looking at the client’s physical capabilities and balance and their beliefs, perceptions, and cognitive appraisals of fall risk. When we engage clients in problem-solving and have them walk through scenarios they perceive as risky, we gain insights into their decision-making process. This helps us pinpoint areas where we can support them to reframe thoughts, modify behaviors, and build confidence.

Now that we’ve covered fear of falling, avoidance behaviors, assessments, and contributing factors, let’s shift to intervention approaches. Our assessments and interventions must consider the biopsychosocial factors influencing fall risk and fear of falling avoidance behavior. We need to treat the entire person, not just isolated factors. Fall risk is inherently multifactorial, and effective interventions often require addressing more than one area. For example, a client’s concern may include physical limitations, psychological factors like anxiety, and even socioeconomic or environmental barriers. Addressing only one factor rarely resolves the problem; we must adopt a holistic approach.

Intervention Strategies: Supported Self-Management

One of the most effective strategies is what we call supported self-management. I emphasize “supported” because simply promoting self-management isn’t enough. We must provide clients with the tools and guidance to manage independently when we aren’t there. Fall risk fluctuates over time, and our goal is to equip clients to self-manage these changes effectively. Our interventions should focus on providing education and training that enables them to appraise their fall risk and capabilities accurately, identify which activities are safe, and know when they need assistance.

Supported self-management involves developing a framework to help clients make decisions about their activity engagement, using techniques like health literacy, task-oriented training, and cognitive behavioral approaches. We want clients to leave our care feeling equipped to self-manage their fear and behaviors throughout different stages of life, not just for the immediate present.

Environmental Considerations

The environment plays a significant role in promoting or hindering safe engagement. Our expertise in environmental modifications can ensure that clients have access to safe and supportive spaces. This goes beyond home modifications; we also need to consider community environments, as many clients withdraw from community activities due to fear. Supporting the appropriate use of assistive devices and mobility aids is also crucial, enabling clients to engage more fully and safely in their surroundings.

Community Programs and Graded Exposure

Community-based fall prevention programs such as A Matter of Balance, Stepping On, Otago, and Tai Ji Quan: Moving for Better Balance have decreased fall risk and improved awareness. These programs incorporate peer support, which helps reduce fear and build confidence. I encourage you to be aware of what is offered in your area so you can recommend them to your clients.

For intervention, the best way to promote safe re-engagement is through *graded exposure*. This involves slowly and systematically increasing participation in feared activities, starting with low-risk situations and gradually increasing the challenge. This approach allows clients to see their capabilities, build confidence, and develop safe strategies, all while receiving our support. We are experts at designing the right challenges that are meaningful and motivating for our clients.

The Role of Cognitive Behavioral Approaches

Finally, cognitive behavioral techniques are a must when addressing fear and avoidance. These approaches help clients reframe their thoughts, challenge beliefs contributing to avoidance, and develop new coping strategies. Whether it’s traditional cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or newer approaches like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), the focus should be on addressing the thoughts and beliefs driving the behaviors. Without this piece, we’re missing a critical component of effective intervention.

Involving Care Partners

It’s also essential to involve care partners in this process. Many clients will spend more time with their loved ones than with us, and the attitudes and behaviors of these care partners can either exacerbate or alleviate excessive fear and avoidance. Care partners often have good intentions, but their words and actions can unintentionally increase fear. We need to help them understand how to provide physical, cognitive, and emotional support that is empowering, not limiting.

In the end, we can sum up the key elements needed to address maladaptive or excessive fear of falling avoidance behavior into three core components:

- Comprehensive Evaluation: A thorough assessment considering all biopsychosocial factors, including an in-depth occupational profile.

- Cognitive Behavioral Interventions: Approaches that address the thoughts and beliefs influencing behavior, customized to the client’s preferences.

- Supportive Occupational Engagement: Graded, safe, and contextually relevant engagement that allows clients to regain confidence, rebuild skills, and develop a framework for lifelong self-management.

As occupational therapy practitioners, we are uniquely positioned to integrate these strategies and truly support our clients in achieving their highest potential for safe and meaningful participation.

Take Away

To wrap up our discussion today, the key takeaway is that fear of falling avoidance behavior is not always bad. However, it can have significant negative consequences when it becomes excessive or maladaptive. This makes early identification and intervention crucial—we cannot wait until a client has experienced an actual fall to address these concerns.

Various standardized assessments can help quantify the impact of fear and avoidance on occupational participation. Even if you don’t administer these tools regularly, you can use the language and concepts they offer to guide your conversations with clients. As occupational therapy practitioners, we have the skills and knowledge to integrate biopsychosocial approaches into meaningful occupations, allowing us to effectively navigate and reduce excessive avoidance behaviors.

I hope that today’s session has provided you with practical strategies that you can apply to better assess and address avoidance behavior in your clinical practice. At the very least, I hope you leave with a heightened awareness of this vicious cycle and feel empowered to intervene before clients get trapped. As OTPs, we have a unique perspective and a comprehensive skill set that position us to be leaders in addressing this issue.

In closing, I hope we’ve met the learning outcomes we set out to achieve today—that you can now recognize avoidance behavior and understand its downstream consequences, that you feel more comfortable distinguishing between adaptive and maladaptive forms, and that you have a clearer sense of what assessments and interventions are available for immediate use.

Thank you for participating, and we’ll now move on to the exam portion.

Exam Poll

1)What does FFAB stand for?

2)What does the vicious cycle of fear of falling cause?

3)Which is a TRUE statement about "inappropriate avoiders?"

4)Which of the following is used to assess for fear of falling avoidance behavior?

5)What has been shown to predict FOF, activity levels, and FFAB, and increase the likelihood of falls?

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Rider, J. (2024). Beyond the fear: Understanding and addressing fear of falling avoidance behavior. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5748. Available at https://OccupationalTherapy.com