Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Bowel And Bladder Considerations: Pediatric Acute Care Virtual Conference, presented by Alex King, OTR/L, CCLS.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to differentiate between and describe 3 modified management strategies for the bowel and bladder systems initiated by the medical team.

- After this course, participants will be able to apply specific bowel and bladder management strategy components to the occupational profile to assess for likely barriers and/or facilitators of participation.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify at least 3 indicators of a need for durable medical equipment evaluation and/or outpatient OT services to support bowel and bladder management as part of the acute discharge plan.

Introduction

Today is designed to provide a general system overview to simplify the concept for everyone. Bowel and bladder function is a complex specialty with numerous directions and challenges, even within the medical community. We are still learning a great deal about it in basic science. The discussion will focus on the plumbing and simplicity of bowel and bladder function and how we can manage it. We will explore how our medical team handles this so we can better support families in managing their children's health conditions and GI tracts.

Scope Accountability

- Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process

- AOTA 2020 OT Code of Ethics

- Licensure Act

- Patient Rights

To begin, we'll discuss scope accountability. This term describes the expectation that an occupational therapist, upon entering a room with a specific licensure and scope, will provide at least an understanding that certain services are available to the client. This allows the client to provide informed consent and request a different provider if necessary or be referred to the appropriate services. Scope accountability is defined by various documents and policies.

The framework for practice from the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) and the American Journal of Occupational Therapy (AJOT) is our most comprehensive guide in the United States. It details what we do and how we do it. This framework is an excellent reference when considering whether a task falls within your scope as an occupational therapist. It outlines what occupational therapists are trained to do and defines our professional boundaries.

The AOTA Code of Ethics is another crucial resource. If there is ever a question about whether you should address a particular issue or whether you are properly addressing diversity and inclusivity, the Code of Ethics supports us in upholding the rights and lifestyles of all individuals.

Specific to your state or area of practice, your licensure act is also essential. Understanding the specific language used in your licensure act to support your actions is important. Knowing which terms and statements in your licensure act back your actions is crucial. While the licensure act may not explicitly mention areas like bowel and bladder function, sexuality, or mental health, it often contains language supporting your general practice area. It is vital to understand what your licensure act holds you accountable for and what permissions it grants.

Finally, it is important to focus on patient rights and informed consent. Clients must know the scope of occupational therapy services in their state, what can be provided, and what you can offer today. This knowledge allows them to both give permission for those services and request a provider who can offer a higher level of specialty or a different level of inclusion for their needs.

OT's Role

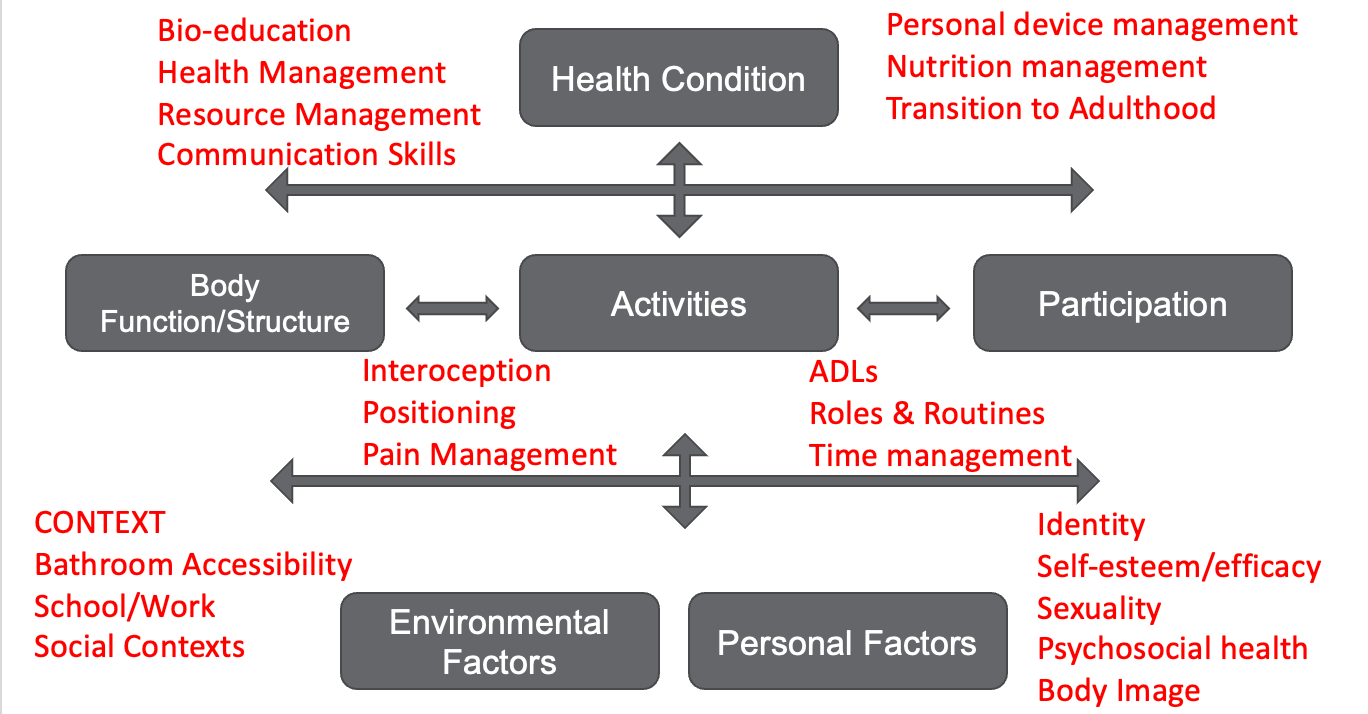

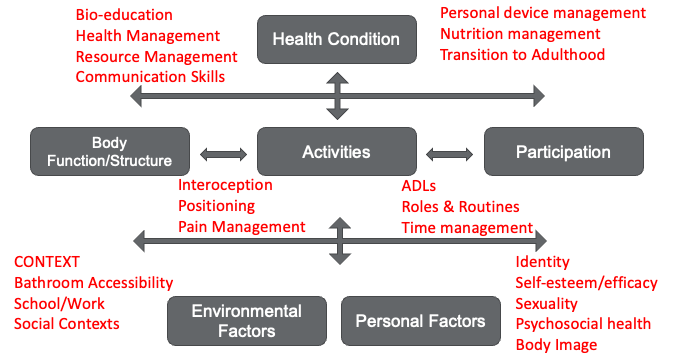

OT's role is integrated throughout the ICF model (Figure 1).

Figure 1. OT's role when compared to the ICF model. (Click here to enlarge the image).

It's crucial to remember that all aspects of our scope are deeply embedded within the lifestyles of our clients. The routines and roles of every individual in a family, the contexts they live in, and the support systems in their lives all stand to benefit from occupational therapy intervention or training. Each element of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) model is represented within our practice act and framework. This means that while you may not explicitly feel like you're addressing bowel and bladder function or another specific area of function, all these pieces fit together.

When you address a client's identity, you're inherently addressing all their occupations and figuring out how that identity merges with different contexts. Bowel and bladder function is deeply integrated into how individuals perceive themselves and interact with the world. It's a part of daily life that varies across different contexts, and how it's managed also changes with these contexts. Mental health plays a significant role in this, often as much as gastrointestinal (GI) function or the specific methods we use to manage our GI and urinary tracts. This holistic approach ensures that occupational therapy considers and supports all aspects of a person's life.

Applying the OTPF-4

This is a reminder that the OTPF gives us a very clear framework for this.

Exhibit 1. Aspects of the Occupational Therapy Domain All aspects of the occupational therapy domain transact to support engagement, participation, and health. This exhibit does not imply a hierarchy. | ||||

Occupations | Contexts | Performance Patterns | Performance Skills | Client Factors |

•Activities of daily living (ADLs) •Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) •Health management •Rest and sleep •Education •Work •Play •Leisure •Social participation | •Environmental factors •Personal factors | •Habits •Routines •Roles •Rituals | •Motor skills •Process skills •Social interaction skills | •Values, beliefs, and spirituality •Body functions •Body structures |

1American Occupational Therapy Association (2020)

Our practice might focus on specific motor skills, such as fine or gross motor skills, to prepare for activities like self-catheterization (cathing). Cathing may be a long-term goal, and upon conducting a task analysis, you might identify motor barriers as obstacles to achieving this goal. Consequently, working on motor skills becomes essential.

We may engage clients in preparatory activities that are functional and relevant to the task and skill of self-catheterization. These activities serve as a foundation for developing the necessary motor skills. As the client progresses, we integrate these preparatory activities with task-specific training, moving closer to achieving the long-term goal of self-catheterization. This approach ensures a structured progression, systematically addressing barriers and building the required skills.

Basic Anatomy Review

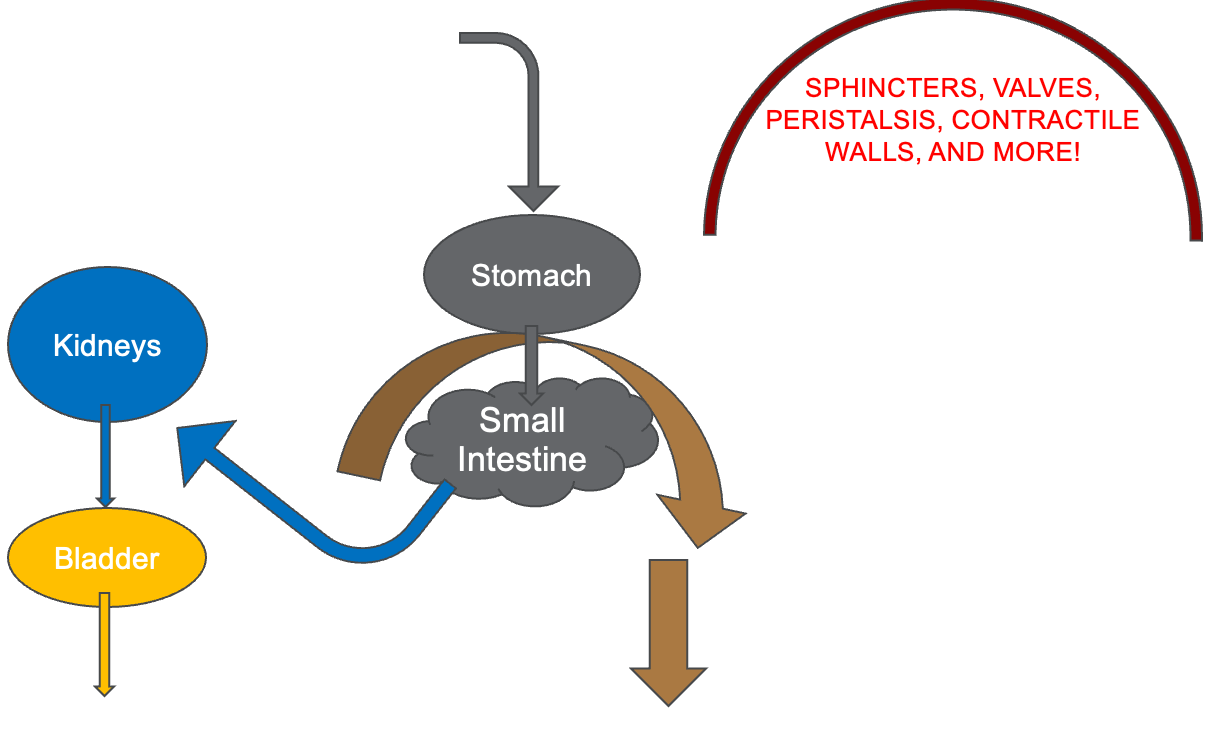

We will start with a basic anatomy review in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Illustration of the bowel and bladder function. (Click here to enlarge this image.)

Our goal is to provide a general understanding of how these systems work. Even if you have a complex understanding, it's important to bring it back to basics, remembering our role and the fundamental aspects of the system.

Today, we won't delve into chemicals, reactions, or neurotransmitters, as the gut's functions are highly complex. There's always a role for managing nutrition and nutrition routines, which we'll touch on later. We'll focus on the hard anatomy, starting with the urinary tract. When we discuss how the entire GI system works, including the urinary system, we start with the basics: food enters the mouth, passes through the esophagus, and reaches the stomach, where significant breakdown occurs. The content then moves to the small intestines, where fluids and nutrients are absorbed most. The small intestines are long and intricately folded within our abdomen, providing ample time for nutrients and chemicals to be absorbed into the body.

After the small intestines, fluid absorption continues and eventually reaches the kidneys. The kidneys process this fluid and send it to the bladder and the urethra. While discussing anatomy, we refer to a general understanding applicable to most populations. However, in pediatrics, anatomical variations are common, so it's essential to verify specifics with providers or families. Some individuals may have atypical anatomy, such as a single opening for the urethra, vagina, and anus, which might have been surgically corrected.

Understanding a patient's medical history is crucial. The typical process involves fluid moving from the kidneys to the bladder and out of the urethra. Fecal matter, on the other hand, travels from the small intestines to the large intestines, which span across the abdomen. This part of the GI tract is where constipation commonly occurs. After passing through the large intestines, the fecal matter moves into the rectum and exits through the anus. While this describes typical anatomy, it's not universally applicable.

Various chemical and absorption processes occur in this process, with motility being a key factor we'll discuss today. Medical interventions often focus on sphincters, valves, peristalsis, and contractile walls that move content through these tracts. Neurological or chemical conditions might impact these functions. We'll focus on educating clients about their conditions and the rationale behind their adaptations. This understanding can aid their mental health and identity, providing a basis for deeper health education.

Bowel Management

- Level 1: Eat, Drink, Sleep, Move (And go to the bathroom)

- Level 2: Medication

- Level 3: Transanal Enema and/or Stimulation

- Level 4: Surgical Intervention

- Cecostomy

- Colostomy

2Bokova, et al. (2022); 3Bokova et al. (2023)

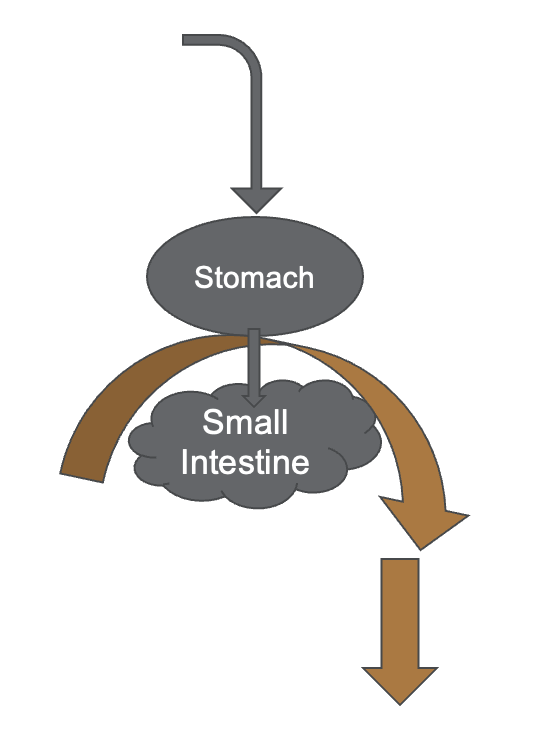

Speaking specifically about the bowel, we will take the urinary process out for a minute. Bowel management comes down to a few primary components, and we've removed the urinary component in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Bowel system.

This looks at how food and solids enter and exit our system. As I said, absorption primarily happens in the small intestines. Breakdown primarily happens in the stomach, and then the whole process (the brown arrow) goes to the large intestine. Its role is primarily moving and condensing that matter through the system and then out so it can be disposed of.

With anything we talk about, whether we're talking about bowel and bladder management, mental health, or chronic condition management, you're always going to start your process with what a daily routine looks like. What do the values look like, and how does all of this fit with the basic things we need to know so that the body continues working well? I call that an eat, drink, sleep, move model, and, in this case, go to the bathroom.

When we're talking about helping someone manage their new bowel program because they have a spinal cord injury, chronic constipation, or psychosocial constipation caused by fissures, we're thinking about how this interacts with their whole system throughout the day. In pediatrics, we often see a correlation between anal fissures and reduced intake of food and similar issues.

We discuss the concept of GI discomfort as a cloud of conditions, recognizing that some people experience having food and nutrients in their bodies as uncomfortable and not pleasurable. They don't necessarily experience hunger and satiety as we do, and they might not find any part of the process—whether intake, digestion, or elimination—pleasurable. Typically, our bodies are designed to give us satisfaction, pleasure, or satiety when we're getting the nutrients we need and expelling what we don't need.

When people don't experience this natural process of pleasure and disposal, they miss out on positive feedback through their nervous and endocrine systems, indicating the process is working well. Instead, they receive signals to avoid the process because it involves pain, suggesting a problem that the body needs to address in a certain way. Often, bowel and bladder conditions start with GI discomfort and progress to more complex issues such as constipation or reduced food intake, or there's a primary condition that leads to GI discomfort and subsequent routine changes.

When someone's admitted to the hospital for a primary condition like constipation, reduced food intake, or chronic stomachaches, the first step for OTPs is to understand who this person is, what’s important to them, how they take care of themselves daily, and what parts of their lives, relationships, and roles impact that process. By understanding the origin of the issue, what contributes to it, and what routine adjustments can help, we can assist the medical team in developing a sustainable discharge plan.

Managing chronic conditions often involves lifestyle changes to prevent, delay, or manage the condition. The biggest challenge is ensuring follow-through on these recommendations because they're integrated into daily routines. As OTPs, we know how to make these changes consistent, ensure safe access, and manage cognitive strategies to support medication adherence and overall health.

When discussing bowel management, our primary job is to understand how a person lives their life and support that process. For anyone with a bowel management issue, changes will be evident in their daily lives, which is often why they're in the hospital. The medical team's initial response to bowel issues typically involves medication to help break down or condense material and move it through the system comfortably and consistently.

We'll skip deep discussions on Bristol stool scales or medications to focus on our role. Medications and other conservative approaches are the first line of treatment. Our job is to understand how the medication affects their system and ensure it fits into their daily routine post-discharge. When medications and conservative approaches fail, level three involves transanal or retrograde enemas to help expel fecal matter. These methods include suppositories and enemas, which introduce fluids or medications into the rectum to stimulate bowel movements.

If these methods also fail, surgical interventions might be recommended, creating an alternative pathway for waste to leave the body, such as a colostomy or ileostomy. This involves an external bag for fecal matter. Another surgical option involves flushing the system from the beginning of the large intestine, sometimes through a stoma, to stimulate bowel movements.

As OTPs, our role is to understand the task analysis and help clients integrate these medical recommendations into their daily routines, ensuring they have the necessary support, equipment, and strategies. We assist in the decision-making process when clients are presented with different options by their doctors, considering their daily routines, relationships, and personal preferences.

No matter the intervention, level one always matters: maintaining the eat, drink, move, take medications, and manage bowels model is crucial for overall well-being.

Bladder Management

- Level 1: Eat, Drink, Sleep, Move (And go to the bathroom)

- Level 2/3: Medication and/or CIC

- Level 4: Surgical Intervention

- Bladder Augmentation

- Vesicostomy

4Hobbs et al. (2021)

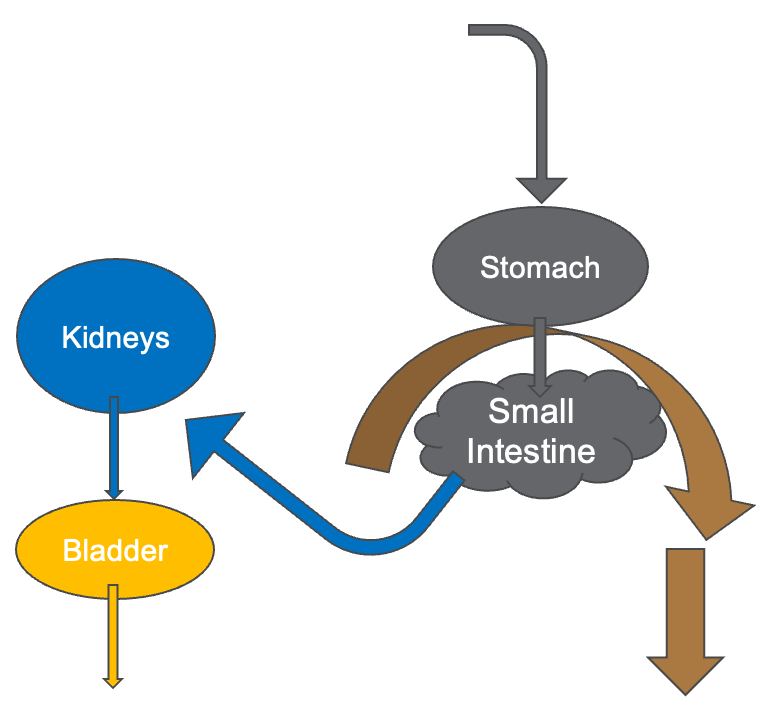

We're going to see a similar model for bladder management. The biggest difference is that the fluids we consume go to the small intestines, where most absorption occurs. While not all absorption occurs in the small intestines, it is the primary site for absorbing fluids (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Bladder anatomy. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

If you have a condition that affects how things get to or process through the small intestines, you're probably going to have an issue with the absorption of fluids. Then, that fluid goes into the bloodstream and processes through the body. We're not going to get into the liver and all the roles of other organs, but ultimately, the residual fluid ends up in the kidneys for processing. The kidneys then send it down through bilateral ureters into the bladder. The bladder has both a contractile and an expanding property, allowing it to either expand to hold more fluid or contract to push it through the urethra and out of the body again.

We start this process by eating, drinking, sleeping, and moving. If someone's not hydrating, it will affect how their urinary tract is working. If they're drinking a lot of water, it will change how often they need to go to the bathroom. We see this in older adults and populations with incontinence or bladder discomfort, as they may limit their fluid intake to avoid incontinence in social or other contexts. For example, someone might hydrate in the evenings because they wear briefs to bed but refrain from drinking in the morning until after 3:00 p.m.

Routines are very important for our bodies. Helping people understand their bodies, the importance of managing their chronic condition, and how to integrate this management into their daily routines is a critical part of our job. Few other providers have the time and the ability to refer for outpatient services to address how these things fit into someone's life. As with bowel management, the biggest barrier to maintaining a chronic bladder condition is self-management, our specialty.

Level two and level three interventions for the bladder can include medication, which is often the first approach if someone has difficulty emptying or maintaining their bladder. If someone experiences incontinence, leakage, or full bladder voiding at inappropriate times, medication is commonly used initially. Additionally, if someone cannot fully empty their bladder, imaging and attention to the kidneys are important because a bladder that cannot empty properly can lead to kidney infections and other kidney problems.

Doctors consider sphincters, contractile tissues, peristalsis, valves, and other factors affected by the nervous and other body systems. While we might understand common issues in certain populations or spinal cord injuries, there is significant diversity in how people's bodies function. Therefore, understanding doctors, reading medical charts, and asking questions is essential to grasping bladder and kidney system concerns.

Our role involves health education and motivational interviewing to help clients develop routines prioritizing their health. We provide clear and accurate education on the consequences of not maintaining their routines. We provide two types of education: the immediate consequences of not following through (e.g., abdominal pain, leakage) and the long-term effects (e.g., kidney damage). Understanding these consequences helps clients manage their conditions effectively.

We often discuss how to manage bowel and bladder functions in conjunction with activities such as sexuality, sports, and other daily routines. Adolescents with bladder issues may avoid sports due to a higher risk of leakage during activity. Linking self-management to motivating factors in their lives and providing adaptations to their routines or contexts supports their health and helps them achieve their desired activities.

Surgical interventions may be considered if medications and catheterization are ineffective. These can include bladder augmentation to increase bladder size or creating a vesicostomy or another stoma to redirect urine from the bladder through an alternative pathway. This can be particularly helpful for those with urethral differences or challenges managing their urethra or sphincters, allowing for better continence and bladder and kidney health.

Your Team

- Client/Family

- Urology

- Surgery

- ENT

- Nutritionist

- Nutritionist

- Colorectal Specialist

- Nursing

- SLP

- PT

- OT

- Nursing

- Pediatrics

- Neurology

- Neurosurgery

- Hematology

- Gastroenterology

- Dietician

- PCP

- SCHOOL

- CAREGIVERS

- COMMUNITY

- AND MORE…

The good news is that there is a very large team, with everyone intimately involved in bowel and bladder management. Each team member's contributions are integral to this process. Our role is less about devising all the solutions, fully understanding every condition and its effects on the body, or knowing all the available products. Instead, we focus on comprehending the collective recommendations from all these providers and how they integrate with the patient's lifestyle. As the team develops the medical discharge plan, it may now include a new medication regimen, a more frequent catheterization schedule, or a new catheterization method altogether. Additionally, we may introduce briefs at night to manage incontinence.

OT's Role

Our job is to assess how the plan will actually work in practice. We need to revisit the OTPF chart and the ICF model to ensure everything aligns with these frameworks. By doing this, we can better understand how the recommendations integrate with the patient's daily routine and overall lifestyle, ensuring a comprehensive and effective approach to their care (Figure 5).

Exhibit 1. Aspects of the Occupational Therapy Domain All aspects of the occupational therapy domain transact to support engagement, participation, and health. This exhibit does not imply a hierarchy. | ||||

Occupations | Contexts | Performance Patterns | Performance Skills | Client Factors |

•Activities of daily living (ADLs) •Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) •Health management •Rest and sleep •Education •Work •Play •Leisure •Social participation | •Environmental factors •Personal factors | •Habits •Routines •Roles •Rituals | •Motor skills •Process skills •Social interaction skills | •Values, beliefs, and spirituality •Body functions •Body structures |

1American Occupational Therapy Association (2020)

Figure 5. OT's role when compared to the ICF model. (Click here to enlarge the image). 1American Occupational Therapy Association (2020).

Our job is to determine how the plan will be implemented. We need to assess whether the patient will be able and willing to follow through with the plan, considering other motivating factors such as their social context, identity, or participation in sports that might take precedence over their bladder health. For instance, if they are uncomfortable catheterizing at school, they won't do it during the day.

We need to figure out where in the school they feel comfortable, where their supplies will be kept, how they will carry out the procedure, whether they will have support, and how the entire process will work. By addressing these factors before discharge, we significantly reduce the likelihood of readmission due to bladder infections, urinary infections, or other related issues that arise from not maintaining proper bladder or bowel care.

Our role is integrated into every aspect of the patient's daily routine, as their bowel and bladder function continuously, regardless of what they do. Whether they are sleeping, running, exercising, attending school, sitting in class, or socializing with friends, their bladder and bowels are always active. It's essential to understand what the bowel and bladder are doing at these times, how the management program interacts with these activities, and ensure that both fit together well without negatively impacting each other.

Often, people might choose their life activities over their bowel and bladder management, or vice versa. Our job is to help them merge these aspects, understanding all the pieces of the occupational therapy domain and how they work as a system. Occupational therapy's role is integrated throughout the entire process. For example, if someone has a long-term goal of catheterization but experiences stress and anxiety around it and is unsure if they can position themselves correctly, we don't need to solve all these issues on the first day. Instead, we gradually help them achieve their goals, ensuring they are comfortable and confident in managing their bowel and bladder health.

Acute Care Goals

- Understanding, Skills, and Readiness for Self-Management

- Barriers to Self-Management Across Life Contexts

- Recommendations: Positioning/Mobility Devices (PRIMARY and BATHROOM, Manual Skill Adaptations, Cognitive Adaptations, Human Supports, Physical/Temporal/Social

- Coping/Adjustment

- Future Impacts on Participation

- Pre-emptive training/education, Future roles of OT

5Edelstein et al. (2022)

When someone is admitted to the hospital and introduced to a new catheterization routine, it is often the occupational therapist’s role to help them understand what we can offer as a profession, both now and in the future. This includes guiding them through problem-solving to achieve their personal goals and ensuring they feel comfortable during their hospital stay. For example, positioning them on the toilet or in a wheelchair for these tasks is essential. While urologists and nursing staff can provide some assistance, we are the experts in positioning devices, so collaboration is key.

Our responsibility is to determine which parts of the process need to happen in acute care and which will be addressed by other team members after discharge. The team includes the patient's family, who often play a significant role in maintaining psychosocial health. We must also consider referrals for future self-catheterization training or other necessary services.

The primary goals in acute care are to ensure that the patient and their family understand this new aspect of their daily routine, recognize its importance, and have the skills to complete it safely and independently. We must also assess their readiness and resources to carry out these tasks regularly. Identifying barriers and making initial and follow-up plans is crucial to manage these aspects effectively.

For many patients, this new routine may involve catheterization or enemas, which require new ways to position themselves. Whether lying on a mat on the floor for a bowel program or transferring to the toilet with a cone enema, we must help them figure out how to make these processes work seamlessly. Planning for such scenarios in advance is essential to avoid complications and readmissions.

Additionally, many bowel programs require significant time, often involving sitting on the toilet for one to two hours. We aim to reduce this time to 30-45 minutes, but we must assess their sitting endurance, pressure points, skin conditions, and potential for prolapse. The team must understand the risks and how positioning and support devices can mitigate them. Initially, a patient might not need a bath, shower, or toilet chair, but if they require extended time on the toilet, these devices become necessary to relieve pressure and provide support.

Our interventions may include positioning devices, adaptations, or modifications to primary mobility or bathroom devices. It could also involve teaching manual skill adaptations, cognitive strategies for routine anchoring, building reminders, or discussing human support preferences. Understanding the patient's preferences for assistance, whether from family or home health nursing, is vital.

Throughout the process, we continuously assess the patient's coping and adjustment to the new routine, considering future impacts on participation. We provide preemptive training, preparing them for puberty changes, sports participation, or after-school activities. We help families understand available resources and how to access them, ensuring that the patient’s personal factors are considered.

Occupational therapy is a lifelong support option for those with chronic bowel and bladder conditions. While not always needed, there will be times when lifestyle or medical changes necessitate OT services. We aim to ensure that these changes don't always lead to readmission but that patients know when and how to access OT services as needed.

Case Studies

We're going to go through a few cases to anchor these concepts. These are all real cases. They've been changed in small ways, like diagnoses, specifics about conditions, or lifestyles, to protect the privacy of these clients.

Case #1 – New Onset

- A 16-year-old s/p GSW to neck resulting in C5-7 SCI. Active movement is limited to the head/face/neck/diaphragm at this time. Sensation is present, although diminished/distorted throughout most of the body.

- OT referral for evaluation of rehabilitation plan/recommendations + DC recommendations.

- OT Eval: BBM review/evaluation revealed successful initial management of bowels with trans-anal enema with in-bed positioning. Bladder management via CIC q4hr – uncomfortable and limited by erection response to triggered spasticity.

- BOWEL INTERVENTION: We reviewed the home context and discussed positioning options for placing the enema over the toilet or commode. The device was trialed and ordered for the home.

- BLADDER INTERVENTION: The OT attended catheterization with the nurse specialist and then assessed spasticity triggers/alleviators (touch and positioning). Collaboration to improve positioning (in power w/c and bed), limit unnecessary touch triggers, and trial a flex-tip catheter resulted in successful catheterization without pain/discomfort.

A 16-year-old status post gunshot wound to the neck results in a C5-C7 SCI, with active movement limited throughout the entire body and the diaphragm. At this time, sensation is present but diminished and distorted throughout most of the body, indicating an incomplete injury. The OT referral is for general rehabilitation plan recommendations and discharge recommendations.

The OT evaluation reveals successful initial bowel management using a transanal enema with an in-bed positioning system. However, bladder management via catheterization every four hours is uncomfortable and limited by an erection response to triggered spasticity. When the patient experiences spastic reactions, which commonly occur in the legs and arms, he also gets an erection.

A home context review and positioning options are provided for bowel and bladder intervention so the enema can be administered over the toilet or commode. The device is trialed and then ordered for home use.

For bladder intervention, the OT attended catheterization with a nurse specialist who focused on training to address spasticity triggers and alleviators. This involved identifying ways to touch or position the patient or avoid certain touches and positions that trigger the erection response and spasticity. Collaboratively, we provided positioning options in the power wheelchair and bed to limit unnecessary triggers. We also worked with the nurse specialist to trial different catheter options, finding that a flex tip catheter resulted in more successful and less painful catheterization, even when an erection was elicited.

Case #2 - Chronic

- A 13-year-old with T10 MMC, shunted HC, and hx of sacral pressure injuries presents s/p surgery for cecostomy placement.

- OT Consult: Evaluation of toileting skills/supports for safe discharge and completion of daily 90-minute bowel flush routine.

- OT Eval + Intervention:

- MWC user with roll-in shower, currently using stationary mesh bath seat (limited self-cleaning due to positioning in the device). CIC q4hr independently.

- Trial and order of self-propelled commode/shower chair with modifications including pressure relieving cushion, padded chest strap for endurance, and education on anterior table placement during voiding routines.

Number two is an example of a chronic case. A 13-year-old with a T10 myelomeningocele or spina bifida has shunted hydrocephalus and a history of sacral pressure injuries. The patient presents post-surgery for a new cecostomy placement, a tube in the right side of the abdomen similar to a G-tube. This tube administers fluid to start a bowel flush, stimulating peristalsis to push feces out of the large intestine.

The OT evaluation focused on toileting skills and support needed for safe discharge. The new requirement was the completion of a daily 90-minute bowel flush routine. The patient, a manual wheelchair user with a roll-in shower, was currently using a stationary mesh bath seat, which limited their ability to self-catheterize due to the device's positioning. Self-catheterization was required every four hours, and the patient performed it independently.

Given their roll-in shower setup, we trialed and ordered a self-propelled commode shower chair during the intervention. Modifications included adding a pressure relief cushion, specifically an air-filled cushion designed for a toilet seat, and a padded chest strap to ensure trunk support and enable endurance for the 90-minute sitting routine. We also provided education on managing an anterior table to allow leaning forward during voiding and participation in activities such as homework during the bowel routine. This approach aimed to ensure the patient could manage their new routine effectively while maintaining time for homework and other daily activities.

Summary

In this course, we learned to differentiate between and describe three modified management strategies for the bowel and bladder. We learned several strategies initiated by the medical team. We applied these specific bowel and bladder management components to the occupational profile to assess and understand likely barriers or facilitators for the patient in life and bowel and bladder management. Additionally, we identified three indicators that suggest the need for durable medical equipment, an evaluation, and/or outpatient OT services to support bowel and bladder management as part of the acute discharge plan.

Questions and Answers

I have a child with spastic cerebral palsy, and he wears a brief for incontinence. His goals are to go to the bathroom for bladder and bowel management every hour. However, he has frequent constipation and uses laxatives chewable daily that help him. Any other recommendations?

It sounds like this is a child who utilizes a brief to ensure safety if they experience bowel or bladder changes in contexts where a bathroom isn't accessible. The child wants or needs to go to the bathroom every hour. The first challenge here would be assessing whether this routine is practical for daily life or too demanding. Going to the bathroom every hour might not be achievable, depending on the child's age and daily routines. It could take a lot of time and energy to get to the bathroom and settle on the toilet.

If this frequent bathroom routine is causing significant lifestyle challenges, it would be beneficial to discuss with the family how satisfied they are with this aspect of care. This might be an opportunity to consult their provider about alternative options to better manage this issue. If the entire daily routine revolves around going to the bathroom, the child may miss out on other activities.

If frequent constipation is also an issue and the child is using chewable laxatives, it seems they are at the early stages of level two management. It might be time to talk to the provider about other medical options that could significantly impact stool passage and constipation management. Reviewing the daily routine is essential, emphasizing the importance of hydration and mobility. For children with spastic CP, hydration can be particularly challenging due to issues like dysphagia, which can reduce fluid intake and contribute to constipation.

The eat, drink, sleep, move model is a great starting point. However, it's crucial to have a conversation with the provider to explore more options. Spasticity affects the bowel and bladder, leading to neurogenic responses and the entire body’s muscle activation and posture, often impacting breathing.

Addressing the quality and symmetry of breathing strategies might significantly improve bowel and bladder management. A physical therapist, occupational therapy practitioner, or speech-language pathologist trained in breathing strategies, such as Mary Massery’s techniques, could be very helpful. Additionally, strategies like taping might be beneficial.

In summary, it seems essential to discuss these issues with the provider to explore more effective management strategies.

Are there any mirror types or other bathroom devices that you have found more helpful?

It's important to have a variety of strategies because there's no one-size-fits-all solution for everyone. That's precisely why referring someone to an OTP is so valuable, as we can problem-solve with them and recommend the most suitable options.

One of my favorite tools is a mirror that flips open with LED lights that turn on when opened and straps to the legs. This design means it doesn't need to be held and provides extra light. These mirrors are compact enough to fit in a small purse, bag, or back pocket.

I also recommend that students and providers learning how to assist with catheterization take the time to explore anatomy on their own. This helps them understand the process better and consider various positions that might work for them. By doing so, they can relate to the process and gain a deeper understanding, which is crucial when teaching someone else about their body.

What practical OT interventions have been successful for those who have undergone surgical interventions?

First, health education using a motivational interviewing approach is essential at an age-appropriate level. This helps the individual understand how their body functions, how to manage it, and how to explain it or set boundaries when discussing it with peers.

It's important to recognize that anyone who has undergone such surgery likely has had challenging medical experiences and might have sensitivities around that area, which is being accessed regularly. Identifying whether there is trauma or sensory sensitivity around the stoma and working through a desensitization approach or providing ways for the individual to self-manage, direct their care, and feel a sense of control is crucial. Utilizing a trauma-informed care approach helps manage these anxieties.

From a social standpoint, it’s important to help the individual understand all parts of their body and diagnosis and how to communicate about it. This includes working on levels of intimacy and trust, understanding which types of relationships they want to share certain information with, and creating a script of words to use when they don't want to discuss it anymore.

Helping them know how to shut down unwanted questions or respond comfortably gives them ownership of their situation. This helps them identify and accept this part of who they are.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74 (Suppl. 2), 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Bokova, E. et al. (2022). State of the art bowel management for pediatric colorectal problems: Anorectal malformations. Children, 10 (846). https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050846

Bokova, E. et al. (2023). State of the art bowel management for pediatric colorectal problems: Functional constipation. Children, 10 (1078). https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061078

Hobbs, K.T. et al. (2021). The importance of early diagnosis and management of pediatric neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Research Reports in Urology, 12 (647-657). https://doi.org/10.2147/RRU.S259307

Edelstein J. et. al. (2022). Higher frequency of acute occupational therapy services is associated with reduced hospital readmissions. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(1). https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2022.048678

Citation

King, A. (2024). Bowel and bladder considerations: Pediatric acute care virtual conference. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5714. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com.