Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Cerebral Palsy Review: Facilitating Functional Outcomes, presented by Patti Sharp, OTD, MS, OTR/L, BCP.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify literature supporting the use of CO-OP for children with cerebral palsy.

- Recognize how the CO-OP approach is used and how it differs from traditional therapy approaches.

- List personal therapy practice and define a plan to apply the CO-OP Approach to a client with CP.

Introduction

Today, we will discuss some interventions for kids with cerebral palsy that look at meaningful activities or the meat of what we are doing. There are a lot of other factors that go into treating kids with CP. The two other presentations in this series cover the diagnosis and classification of CP and evidence-based interventions for kids with CP.

As we chat today, I want you to reflect on your caseload or someone you saw years ago. Hopefully, you can learn some techniques that you can use right away.

Agenda

- Brief Review of CP

- What is CO-OP?

- Application to CP

- Using the CO-OP approach

- 7 key features & 4 main objectives of CO-OP

- Application to Caseload

- Discussion & Questions

We are going to start with a brief review of CP. Then, we will talk about CO-OP and how it applies to cerebral palsy. The CO-OP approach is usually taught in a two-day workshop, so this is just a little taste. However, you should be able to take ideas and start to apply them.

Brief Review of CP

Definition

- An umbrella term that describes a group of disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation, that is attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occur in the developing fetal or infant brain.

What CP is Not

- Cerebral palsy is not progressive (i.e., brain damage does not get worse) --> secondary conditions exist, such as muscle spasticity, which can develop and may get better over time, worse, or remain the same.

- Cerebral palsy is not communicable --> It is not a disease and should not be referred to as such.

- Although cerebral palsy is not "curable" in the accepted sense, training and therapy can help improve function.

The damage happens during birth or shortly after that and is not progressive. Cerebral palsy is not progressive, but the problems from this initial brain injury can worsen if we do not treat them like spasticity. If we do not manage the spasticity, we can lose range of motion, and they can develop contractures. The CP looks like it is worsening, but the actual insult to the brain does not change after it is there.

Cerebral palsy is not communicable, as it is not a disease. And though it is not curable, as therapists, we are not aiming to cure whatever happened, but we can do a ton to improve function and participation through therapy.

When Can You Identify CP?

- Typically not diagnosed until 12-24 months (Rosenbaum et al., 2007)

- Newer research indicates that CP can be accurately predicted or diagnosed as "high risk for CP" before 6 months (Novak et al., 2017)

- Newborns - screening should be done on any high-risk populations through 5 months of age

- Prematurity, neonatal encephalopathy, birth defects, NICU admits

Typically, it is not diagnosed until one to two years, even better than it was a couple of years ago. Then, it was not diagnosed until three, four, or five years old as pediatricians took a wait-and-see approach. New research shows that we can spot CP before six months, which is fantastic because we know from our experience and the literature that the sooner you intervene, the better their outcomes.

Infant Detectable Risks

- These signs prompt further evaluation for CP (Novak et al., 2017)

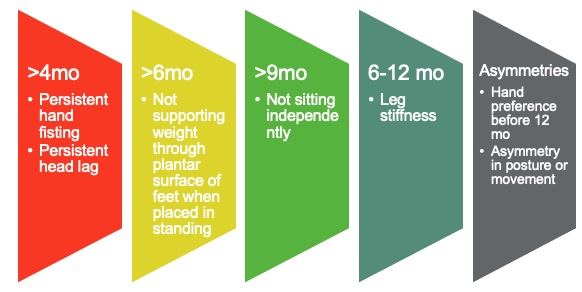

There are some things we can see early on called infant detectable risks in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Infant detectable risks.

At four months, there can be persistent fisting or head lag when you pull a baby up. If they do not bear any weight through the plantar surface of their feet by six months, that is a sign. They also should be sitting independently by nine months. Between six and 12 months, you want to look for leg stiffness that is not controlled. We also want to look for any asymmetry before 12 months. Kids this young are not right or left-handed. They do not use one hand more than the other when they are infants. If they are, that is a concern. And you want to also assess for any asymmetry in posture or movement. This could include favoring one leg over another or always having one curled up.

If we see these signs, we should refer the child to a pediatrician or a CP clinic to check for other signs of CP.

What Causes CP?

- Even though cerebral palsy affects muscle movement, it is not caused by problems in the muscles or nerves.

- Instead, faulty development or damage to motor areas in the brain disrupts the brain's ability to adequately control movement and posture.

- Most cerebral palsy is related to brain damage that happened before or during birth, though some is related to brain damage after birth. (www.cdc.gov/NCBDDD/cp/data.html)

It looks like a motor disorder as their muscles are not working, they are tight, and they cannot control any of their movements. Does that mean that there is something wrong with the muscles themselves? Are they pathological? The answer is no, not at the beginning. Of course, if we do not intervene and get those muscles moving and stretching, they will atrophy and become pathological. But in general, the muscles are fine.

Is it a peripheral nerve disorder with nerves not firing correctly into the muscle? The answer is no, as the nerves are fine.

Instead, it is a brain disorder. Something happened in the brain, causing targeted damage to the motor control area and cerebral palsy. It is essential to keep that in mind because we treat motor symptoms, but this does not treat the disorder itself. That damage to the brain happened early on, and it is not changing. We are not aiming to remove or cure the CP.

It is up to two years that specific damage to a motor area can fall under the CP umbrella. For example, if a premature baby has a brain bleed two or three days after birth, this can count as CP.

Epidemiology

- Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common motor disability in childhood in the US (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/cp/data.html).

- About 1 in 345 children in the US have CP

- Prevalence of 1 - 4 per 1,000 births worldwide

- Increased prevalence of CP for:

- Children born preterm or at low birthweight

- Significantly more common among black children than white children

- Hispanic children and white children are equally likely to have CP.

It is the most common motor disorder in children in the United States. About one in 345 children in the United States have CP; globally, it is about one to four per thousand births. Demographic data shows that different groups have higher percentages of kids with CP, such as preterm or low-weight babies and Black versus white children. Hispanic and white children are equally likely to have CP. It is not known why this is the case.

Symptoms of CP

- Decreased muscle length

- Altered muscle tone

- Decreased muscle strength

- Decreased selective motor control

(Bax, 2005; Wright & Wallman, 2012)

These are the four main things that we deal with as therapists. Even though some of these kids are spastic and tight, this does not mean they are strong. They also have decreased selective motor control, which is generally the thing that gets in the way of the function. A ton of information looks at the different classifications showing the best interventions and outcomes.

CP Classification

- Tone & Movement

- Defines motor subtype

- Topography

- Unilateral or bilateral, UEs or LEs

- Gross Motor Function

- GMFCS

- Fine Motor Function

- MACS, Mini-MACS, AHA

- Communication

- CFCS

- Eating Function

- EDACS

You can classify these kids by tone and movement. For the motor subtype, is it spasticity, hypotonia, or dyskinesia? We will talk about the different types here in a second. We can talk about the topography and what body part is impacted. Gross and fine motor function are fundamental ways we, as therapists, talk about these kids. For gross motor function, there is a test called the GMFCS, and for fine motor function, it is the MACS or the Mini-MACS. We will discuss both in a moment.

There is also research on communication and eating function and some tests that divide them into groups. All of these are broken down into these five main levels.

Classification By Muscle Tone

- What is tone?

- Continuous & passive partial contraction of muscles

- Muscle's resistance to passive stretch during resting state

- Tone is NOT the same as strength.

- Strength is the amount of force a muscle can produce with a single maximal effort.

- A spastic muscle can be weak, and a hypotonic muscle can be strong.

One of the main ways we will classify these kids is by muscle tone. This is something that it took me a while to understand. It can be hard to wrap your brain around because tone looks like strength. However, tone and strength are not the same things. These kids do not necessarily have problems with strength, as the initial problem is the altered tone.

Tone is a continuous, passive partial contraction of muscles. Their brain is turning the muscle on continuously, and it is uncontrolled. You can test tone with the muscles' resistance to passive stretch. You can also see it with movement. Again, tone is not the same thing as strength. Strength is the amount of force a muscle can produce with a single maximal effort, with "effort" being the keyword. Tone is your brain is making your muscles go haywire. A spastic muscle can be weak, and a hypotonic muscle can be strong. The way I explain this to families and students is that the brain is like a radio, and tone is the volume control. People unaffected by cerebral palsy have a ton of tone control. They can turn tone up or down depending on the activity, which is fine-tuned for each little muscle. This control allows for fine motor control and dexterity. For clients with CP, tone is either on or off.

Tone is off when the person with CP is resting or asleep. But when you startle these kids, or they are trying something hard, are excited, scared, nervous, et cetera, their tone is full force. You and I can turn on one muscle to whatever volume we want. For these kids, all the muscles in the arm, for example, are on at once. This leads to synergistic patterns of movement. Whatever muscles are stronger (usually the flexor muscles) will overpower the weaker (extensor) muscles, even though the brain is firing to all of them.

This is how I explain tone. Hopefully, this is helpful to you.

CP Population Distribution

- Spastic 85-91%

- Dyskinetic 4-7%

- Ataxic 4-6 %

- Hypotonic 2%

(Novak et al., 2017)

Most clients are spastic, with tightness and the uncontrolled turning on of muscles. Parents will say, "They are loose when they're asleep." This is because the brain is resting. However, they show spasticity whenever they try to do something effortful or are excited.

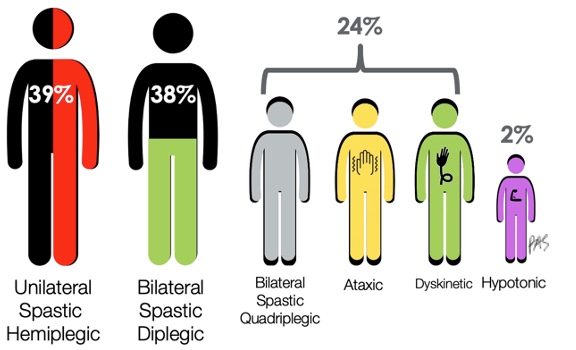

Other clients are dyskinetic, with writhing, choreiform form movement, ataxic, with shaky uncontrolled movement, and hypotonic. There is some discussion in the CP world about whether kids with just hypotonia have CP. The topography distribution can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percentage of CP population by muscle tone.

About 40% of kids with CP are hemiplegic, with an affected arm and a leg on one side, and about 40% are diplegic, with only their legs affected. The remaining categories involve all four limbs with a presentation of ataxia, dyskinesia, or hypotonia. Most of the kids we see will be either hemiplegic spastic, or diplegic.

These are two main ways that we can classify CP, and therapists must understand how these affect gross and fine motor function.

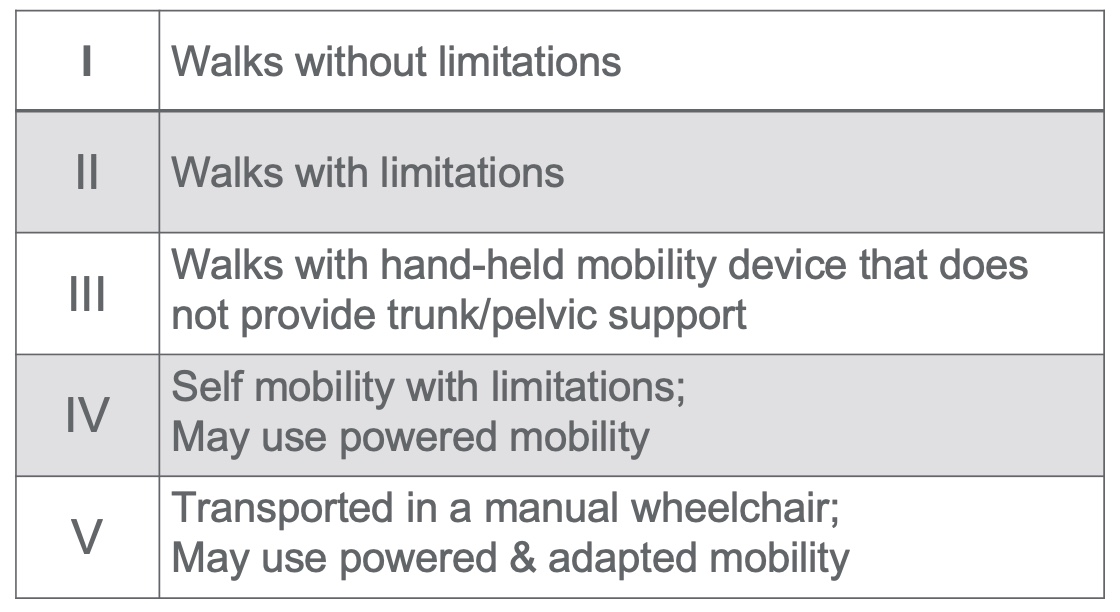

Gross Motor Function

- In children with CP, gross motor function can be described in 5 levels using the Gross Motor Function Classification System GMFCS (Palisano et al., 1997) or the Extended & Revised version GMFCS-E&R (Palisano et al., 2007).

- Available free online on multiple websites

- Generally stable after age 2

- Do not assign before age 2 – period of rapid change

Gross motor function is classified into five levels using the Gross Motor Function Classification System or the GMFCS, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. GMFCS-E&R General (Palisano et al., 2007).

These levels are meaningful to those treating CP. It is free online and on multiple websites. They have these levels broken down by age. Generally, these are not assigned until age two, as the tone may still develop, and intentional movement is not yet known. They will also not go from Level I to Level III or vice versa. For example, we may say to the family that a child will not move from Level III as they need crutches, but they may be able to increase activity with crutches.

Level I is the least impacted, and Level V is the most impacted. Level I is walking without limitations, but they might be somewhat unsteady and uncoordinated. Level II has trouble with curbs and stairs, but they do not need a device. Level III is when they are using a walker or Lofstrand crutches that do not provide pelvic support or trunk support. Level IV is self-mobility with limitations with a wheelchair or a gait trainer. Level V are those that are dependent and need care throughout their whole life.

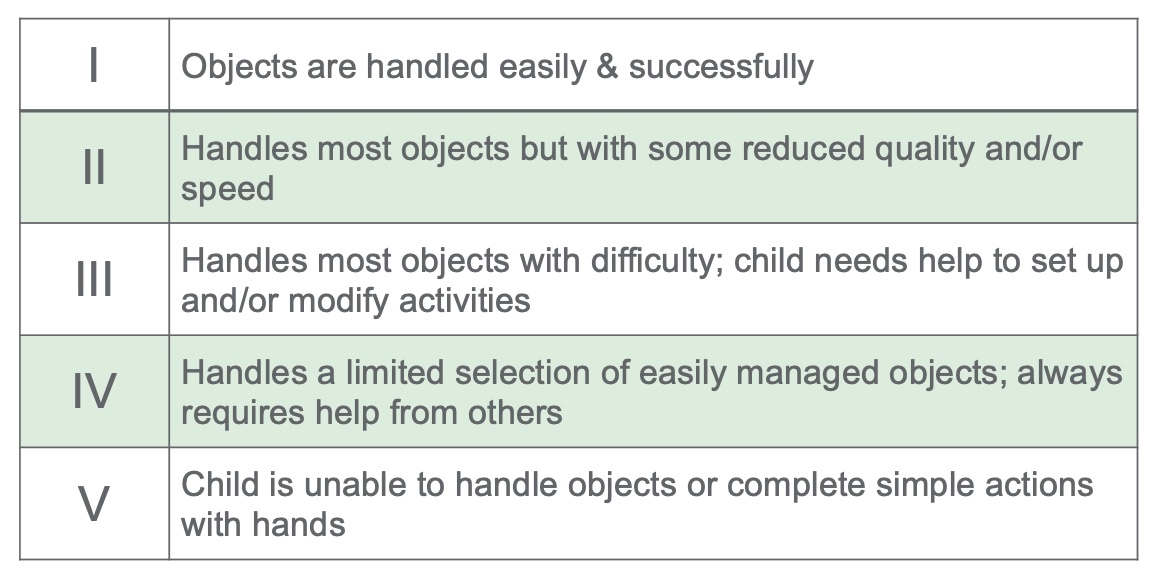

Fine Motor Function

- Measured in kids with CP using the

- Manual Abilities Classification System MACS (Eliasson et al., 2006)

- Mini Manual Abilities Classification System Mini-MACS (Eliasson et al., 2017)

Fine motor function is measured by MACS, the Manual Abilities Classification System, or the Mini-MACS, which is just for younger kids.

- MACS (Eliasson et al., 2006)

- Describes how children ages 4-18 years with CP use their hands to handle objects in daily activities on a regular basis (not BEST performance)

- Considers overall abilities, not each hand separately

- 5 levels based on self-initiated activity, need for assistance or need for adaptation

- Free online https://www.macs.nu/

This scale describes how kids best use their hands to handle objects in daily life. It does not matter if they use only one hand (like hemiplegia). It looks at how they can do things, whether it can be done independently, and if they require help or adaptation. This looks at them regularly and not on their best day.

- Mini-MACS (Eliasson et al., 2017)

- Mini-MACS classifies children's ability to handle objects that are relevant to their age and development, as well as their need for support and assistance in such situations.

- For ages 1-4 years

- Also free online https://www.macs.nu/

The Mini-MACS in Figure 4 is for kids ages one to four.

Figure 4. MACS & Mini-MACS - General.

Again, the least impacted is Level I, and the most impacted is Level V. Someone in Level I can handle most objects easily, but maybe with some clumsiness and incoordination. In Level II, there is some reduced quality, and it is slower, but they can still do what they need to and want to do. Level III handles most objects with difficulty and requires setup and modification. This is where they may use push scissors or a universal cuff. Level IV is profiting help. Level V includes kids who are dependent.

CP Summary

This was a whirlwind overview of CP. As I said, look at the other lectures if you want more detail. Much data went into determining the GMFCS and MACS levels to help us prognostically. That does not mean that some kids will be out of the norm and can progress from Level II to Level III. But generally, they will stay at their levels based on lots of research. To best help these kids, I will refer to these levels throughout the talk.

CO-OP

Let's talk about CO-OP, the main focus of this talk. I recommend looking into this great example of how CO-OP can be used with patients with CP in this video.

What is CO-OP?

- "a client-centered, performance-based, problem-solving approach that enables skill acquisition through a process of strategy use and guided discovery."

(Polatajko & Mandich, 2004, p. 2).

What the heck is CO-OP? CO-OP stands for the Cognitive Orientation Approach to Daily Occupational Performance. I am not a huge fan of the title because it is long. And while I do love the word occupation, this method is not just for occupational therapists and can be a turnoff for those who are not OTs.

I teach this method with a PT colleague. It is a client-centered, performance-based therapy approach involving problem-solving that enables skill acquisition through strategy use and guided discovery.

Goals of CO-OP

- Skill acquisition

- Strategy use

- Generalization to other settings

- Transfer to other tasks

- The client's goals can serve as a means to an end, which is the effective & proficient use of metacognitive strategies.

CO-OP has four main goals. Number one is skill acquisition, not impairment reduction. It is not an increased range of motion or learning strategies. It is to get the child or person to do what they need, want to, or are expected to do.

The second goal is a close second to me, which is strategy use. As a therapist, the goal serves as a means to an end. The end is that I am looking for effective and proficient use of these strategies, which we will talk about in a minute.

The other two goals are generalization to different settings and transfer to other tasks. We want the client to use these strategies at home, school, or wherever. We also want them to take the problem-solving strategies they used to ride a scooter and use it to do a ponytail or paint a picture.

I have seen kids complete these goals using CO-OP, which is terrific. There is a lot of research on it, and it is starting to get more momentum in the United States. It has been widely used in Australia and Canada.

- CO-OP has been proven to meet primary goals, including transfer to untrained tasks.

- (Capistran & Martini, 2016; Houldin et al., 2018; McEwen et al., 2014)

- Important secondary gains:

- Participation

- Elements of motor control

- Elements of cognition, including cognitive flexibility and self-regulation

- Self-efficacy

Research shows that it meets those primary goals, including transfer to untrained tasks. They are seeing some significant gains that were not necessarily the primary goals, like participation, elements in motor control (range of motion and strength), cognitive flexibility, self-regulation, and self-efficacy, which I love to see. Giving kids this power to figure things out and understand how they did something successfully is so awesome. You can see the kids have so much more confidence.

Origins of CO-OP

- Originally developed to enable skill acquisition in children with developmental coordination disorder (DCD)

- Founded on theory

- Supported by evidence originally from studies of children with DCD

- Supported by evidence from studies on several other child and adult populations

Polatajko, H. J., & Mandich, A. (2004). Enabling occupation in children: The Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) approach. Ottawa, ON: CAOT Publications ACE.

It was originally developed for kids with DCD or developmental coordination disorder. Many theories, including learning, motor learning, and cognitive behavioral, were used in its creation. The initial evidence supports it with kids with DCD, but much research is now coming from different populations. We see gains in kids and adults with various disorders.

Why do we care that it was initially developed for DCD? Kids with developmental coordination disorder cannot make a plan to get something done, like riding a bike or forming the letter "A." They cannot make that mental model move their bodies. They appear clumsy, crash their bikes, make many mistakes, and drop things. They are like bulls in a china shop. We tell them to do things better, and they do not listen. These are all motor outcomes, but DCD is not necessarily a motor disorder.

Why is DCD important to CO-OP?

Figure 5. Infographic about DCD. Image sources: Continued (licensed from Getty Images)

It is a cognitive problem because their muscles, nerves, and brains are fine. If you look at them on an MRI, they are normal, but their ability to put thoughts together to achieve motor outcomes is not there. DCD is a cognitive problem with motor symptoms. Why does that matter?

- Individuals with DCD are unable to make mental models.

- The thought processes about how things work in the real world

- Can help shape behavior and set an approach to solving problems and doing tasks

- CO-OP targets the cognitive skills of

- Individual performance analysis

- Problem-solving

- Creation & evaluation of a plan

- These specific skills are those used in making mental models!

Kids and adults with DCD cannot make mental models or thought processes about how things work. These mental models can shape behavior and set the individual up for problem-solving. All of this is not well organized in people with DCD. CO-OP targets the skills that are specifically used for making mental models.

It also includes performance analysis (How well did I do?), problem-solving (How could I do it better?), and the creation and evaluation of a plan. CO-OP looks at the cognitive piece to make plans to do things.

CO-OP & Other Diagnoses

- What are other conditions which may result in a "mismatch" between the cognitive plan and the motor outcome?

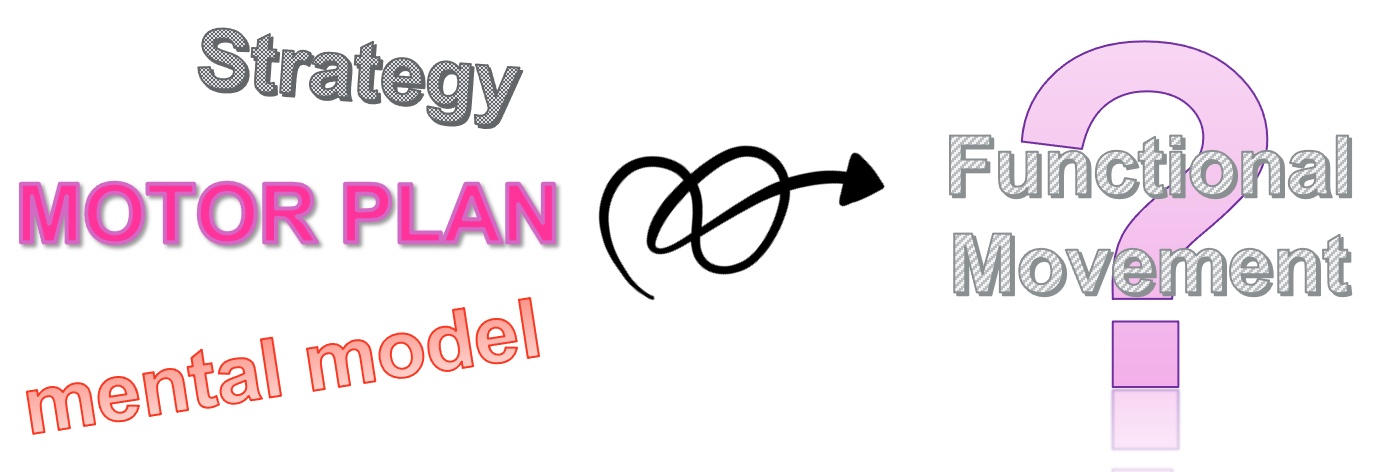

For kids with DCD, the cognitive plan is a mess, as seen in Figure 5.

Figure 6. An infographic showing the mismatch of the cognitive plan and functional movement in those with DCD.

They have a messy motor outcome. The cognitive plan is there for people with CP, but the motor outcome does not happen because the cognitive plan does not match what their body wants to do. Thus, if I am trying to teach a child with CP how to move their body as if it were mine, that will not result in functional movement.

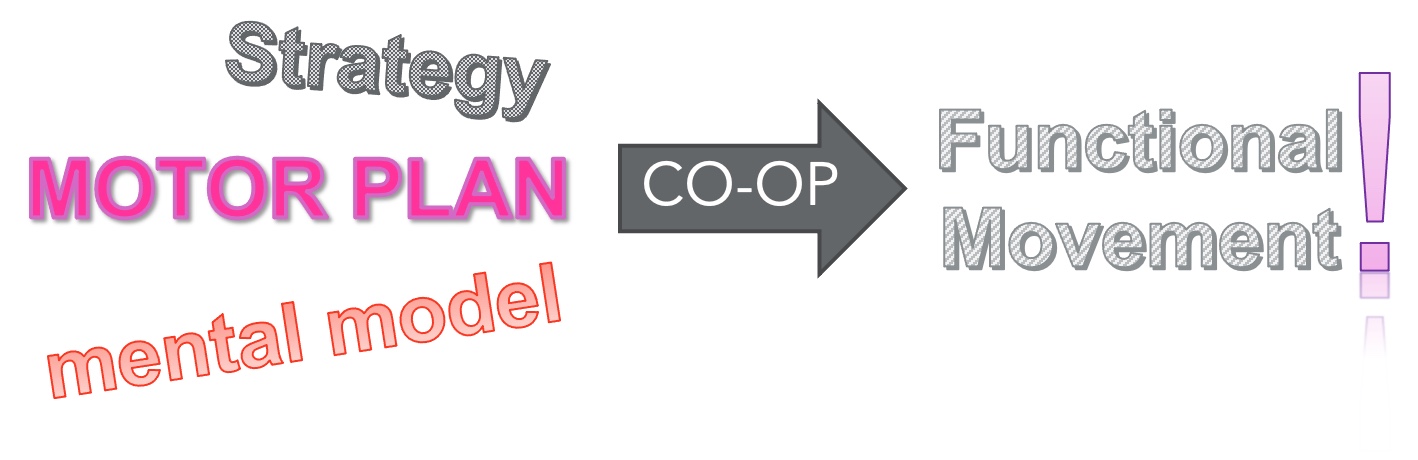

- CO-OP can tighten up the connection between the cognitive plan and the motor output for many conditions.

Figure 7. An infographic showing how CO-OP helps tighten the connection of the cognitive plan and functional movement in those with many disorders.

Research shows that CO-OP helps facilitate functional outcomes for various conditions for adults and kids, like DCD, autism, cerebral palsy, dystonia, ADHD, brain injury, stroke, and spina bifida.

Evidence for CO-OP

These links should send you right to an updated bibliography on the ICAN website, PubMed, and Google Scholar.

Application to CP

Evidence for CO-OP & CP

- CO-OP facilitated personal goal achievement and enhanced self-efficacy (Ohrvall et al., 2020; Peny-Dahlstrand et al., 2020)

- Improved functional skill performance significantly more than traditional therapy approaches (Sousa et al., 2020

- Enhanced goal achievement without functional hand splinting more than traditional therapy WITH hand splints (Jackman et al., 2018)

The evidence is pretty strong on using CO-OP for kids with CP, but all are relatively recent, as I do not think it was thought of to use CO-OP for kids with CP until recently. Some excellent studies, including some systematic reviews, show that CO-OP facilitates personal goal achievement and enhanced self-advocacy, which is so powerful for kids with CP. Some show improved functional skill performance, significantly more than traditional therapy approaches, which is also cool.

We also see more significant improvements than with traditional approaches. Jackman and colleagues looked at a group of kids with thumb splints. The thinking was that if we put the thumb in a better position, the child would be able to grab more. They looked at a group of kids with thumb splints and CO-OP, thumb splints alone, no thumb splints, and then just CO-OP. They found that the thumb splint added nothing, which I thought, "Well, that was 15 years of my practice." And the group with the thumb splint and the CO-OP did not do better than just the CO-OP alone. The results also showed that the CO-OP groups did better than the traditional therapy approaches. Reflecting on the thumb splint approach, I am trying to think of their body in the way my body works and putting their thumb in the correct position so it will do better. However, if I help them develop a plan for their body, wherever their thumb is, we get better outcomes. This approach is cooler, simpler, cheaper, and less stinky.

Here are some more powerful systematic reviews.

- Occupational Therapy Interventions for Children and Youth Ages 5 to 21 Years (Beisbier & Cahill, 2020)

- Occupational therapy practice guidelines for children and youth ages 5–21 years (Cahill & Beisbier, 2020)

- State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: systematic review of interventions for preventing & treating children with cerebral palsy (Novak et al., 2019)

- Effectiveness of pediatric occupational therapy for children with disabilities: A systematic review (Novak & Honan, 2019)

AOTA recently developed a guideline called OT interventions for Children and Youth Ages 5 to 21. They also came out with overall practice guidelines. This research showed strong support for using CO-OP to achieve functional outcomes. If you are looking for range of motion or elements of motor control, CO-OP is not going to be as strong because we do not care at that point. Do I care about range of motion? Absolutely. But, I only care about range of motion if it is getting a kid to improve function and do the things they want.

Iona Novak and colleagues have a great article that I cite in all of my presentations. She did this massive systematic review in 2019 that looked at all pediatric OT populations. It included many diagnoses and interventions. They found strong support for using CO-OP to prevent further impairment in kids with CP and improve functional outcomes. There was a recent systematic review specific to cerebral palsy, and they showed strong support for strong use of CO-OP for it.

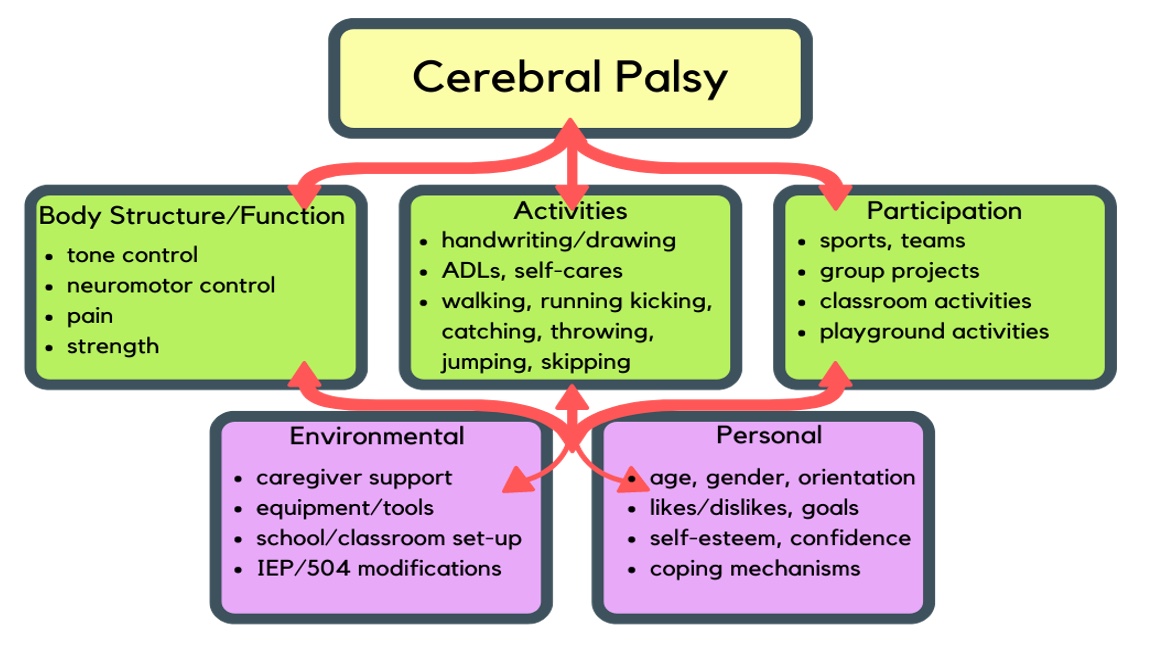

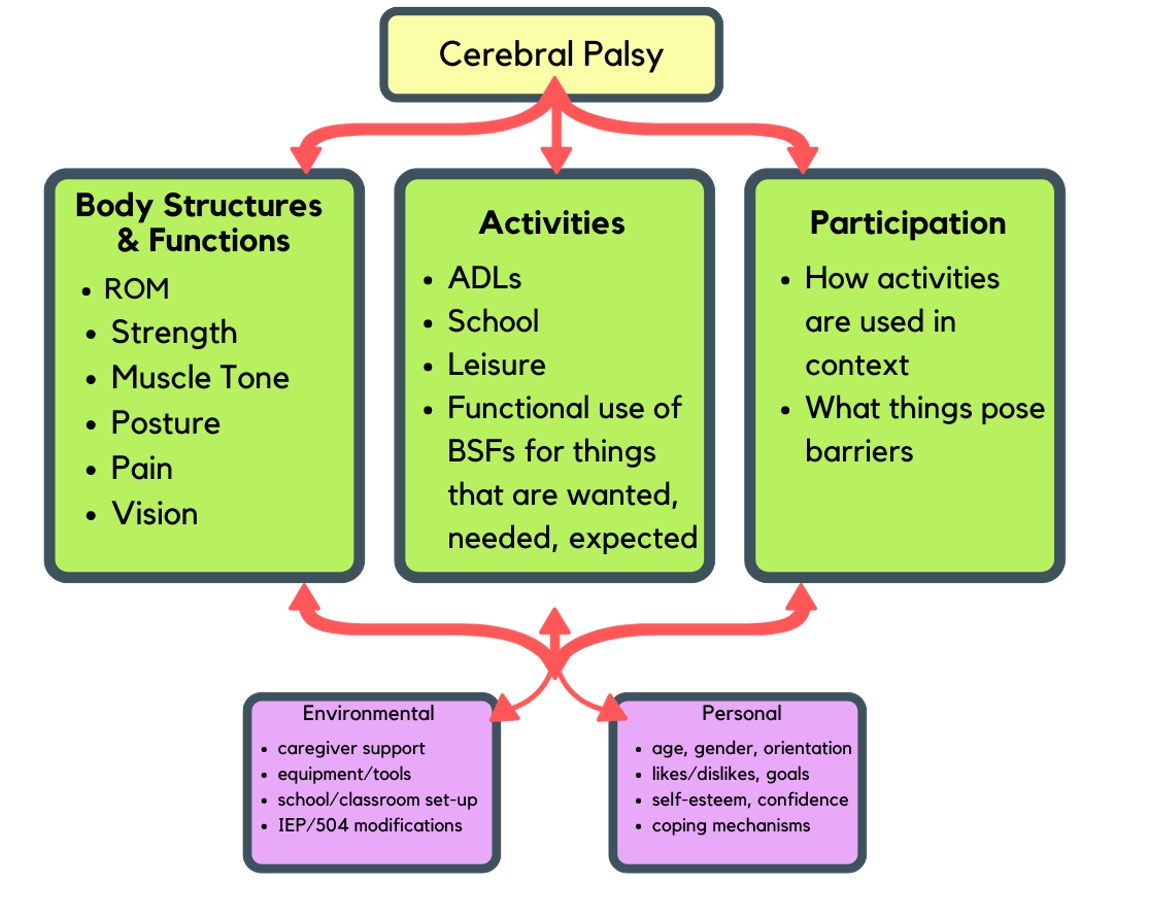

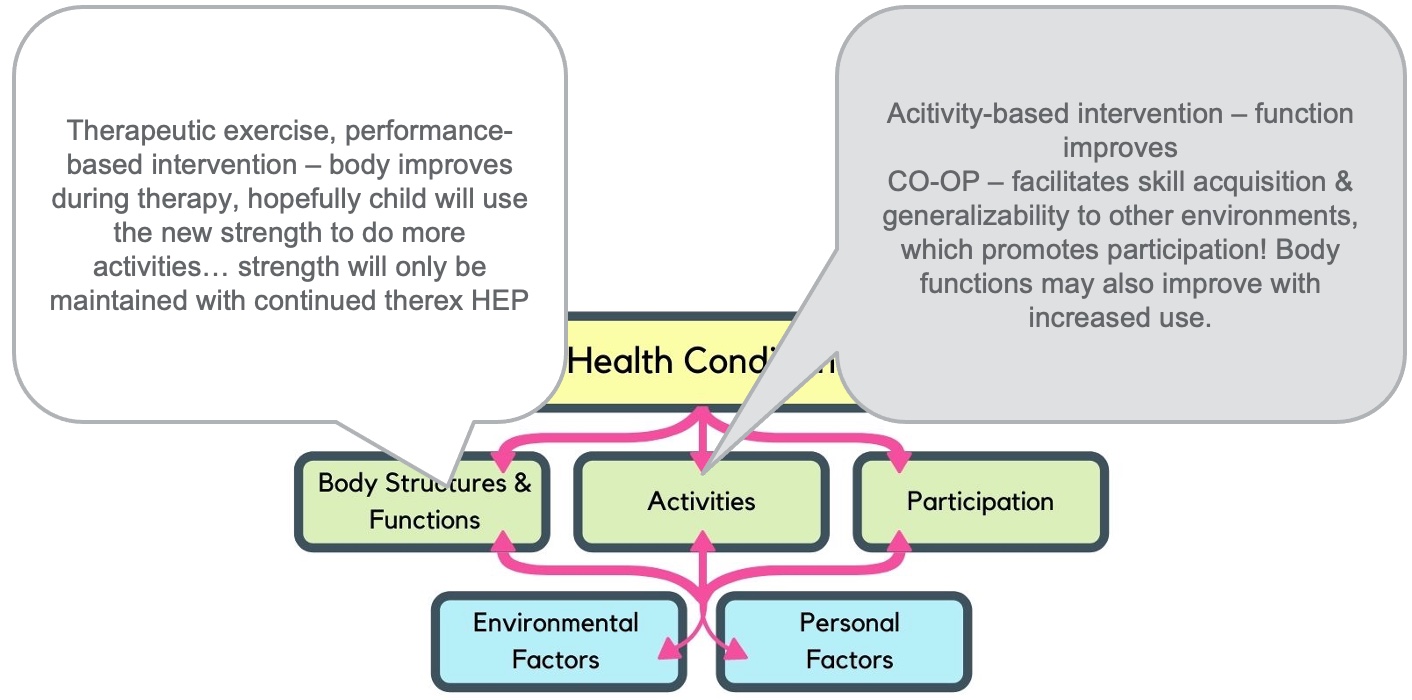

In summary, that evidence is there. Let's look at how CP impacts a child. Figures 8 and 9 show the ICF model or the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. It looks at any condition and outlines how it impacts a person. We can examine how the disease affects three levels: body structures and functions, activities, and participation.

Click here to enlarge this image.

Click here to enlarge this image.

Figures 8 and 9. Graphics of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health using a CP case study (WHO, 2001).

Body structures and functions are the things we measure when we do a detailed assessment and evaluation that include tone control, neuromotor control, pain, strength, range of motion, dexterity, visual perception, visual motor, and any of those component types of things. These all contribute to function, but we can measure them on their own. If we were using a medical model for reducing impairments, this is where we would focus.

In the middle is activities. Activities are the things we do as part of our daily functioning, like handwriting, drawing, getting dressed, and doing self-care. It also involves leisure activities such as running, kicking, and walking.

Participation is being on a team, in a classroom, sitting at the dinner table with your family, et cetera.

As a reminder, we are not impairment reduction therapists. We do not get significant gains from looking at motor components like range of motion. We are here because we want these kids to do what they want and participate with their peers and family.

We also have to look at the things that contribute to these factors, as sometimes we can make improvements here. Environmental factors include caregiver support, tools, the setup in their classroom or home, and any modifications in an IEP or 504.

Personal factors are also impactful, looking at age, gender orientation, likes, dislikes, self-esteem, confidence, and coping mechanisms. Cultural and family values will also impact how much we want to work on changing this child versus accepting and getting to function.

I think these are nice visuals. Whenever I create an intervention, I think, "Where am I aiming? Am I just improving strength?" And "Does that matter?" We are not body function and structure improvement therapists. We want activities, participation, and occupation.

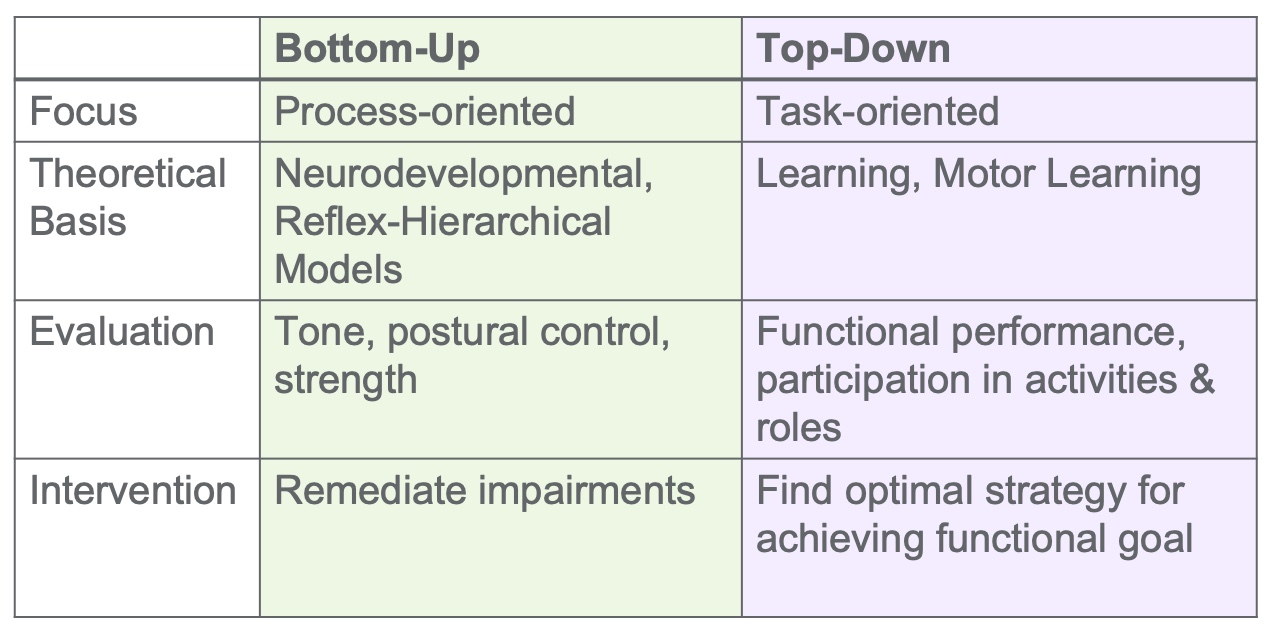

Intervention Approaches: Bottom-Up Vs. Top-Down

There are two main ways that we can approach interventions. The traditional way (medical model), and the way I learned in school, are more bottom-up. It is process-oriented, where we will evaluate everything, including tone, postural control, and strength. This is where we do a grip strength on everybody. It is also based on neurodevelopmental theories and reflex hierarchical models that we need to do things in a certain order. We need to crawl before we walk. You have to have certain base skills before you get further ones. The intervention is aimed at remediating impairments. A top-down approach is more task-oriented. This is where research is shifting, and those extensive OT studies show that interventions that aim at improving activities and participation are much more powerful and effective than those that are bottom-up. They aim at the task based on learning and motor learning theories. Figure 10 shows a side-by-side comparison of the two.

Figure 10. A side-by-side comparison of the two approaches.

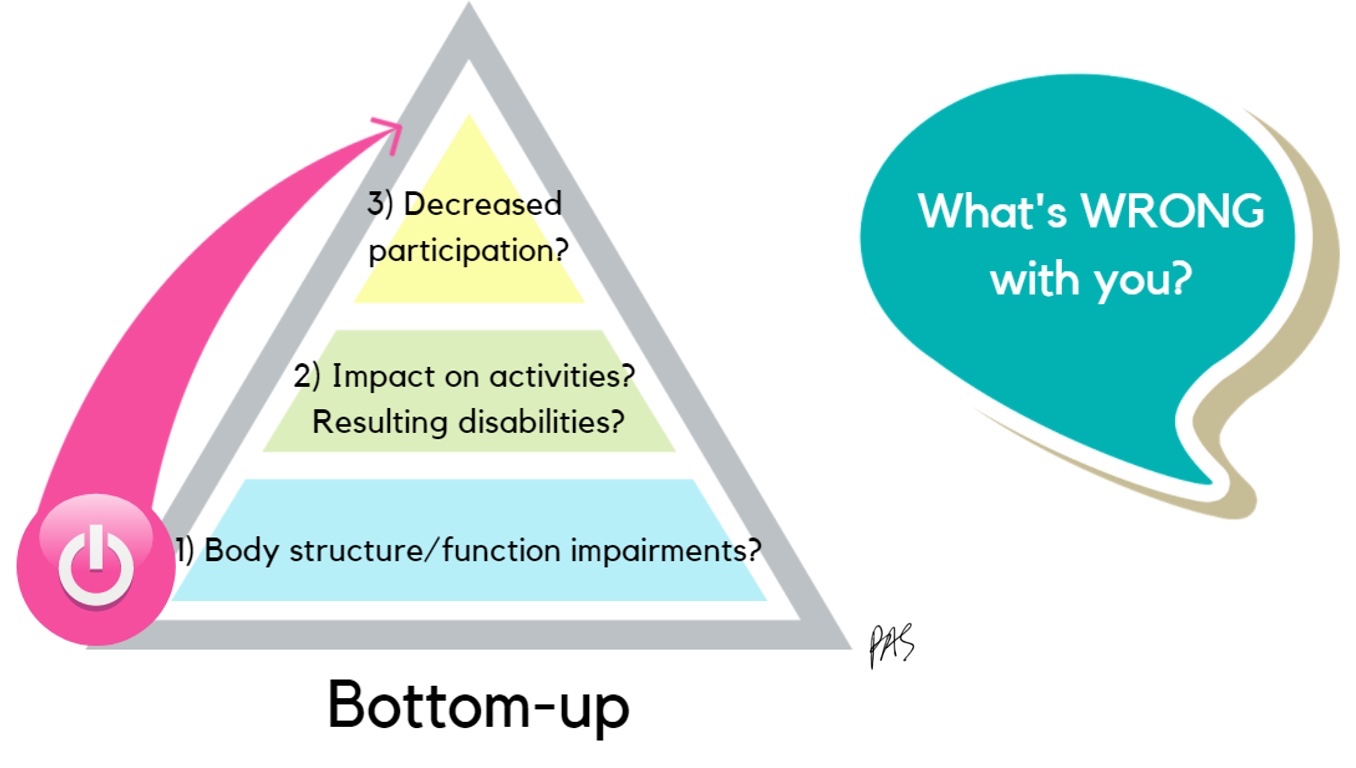

Bottom-Up Interventions

Another way to conceptualize a bottom-up approach is in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Bottom-up approach.

You ask the question, "What's wrong with your body?" You are looking if the functional impairments impact activities and participation. It is based on the theory that if we make one's body strong, dextrous, and all those things, they will be able to do more activities leading to more participation. However, it does not work that way. How often have you been frustrated that a child still does not improve performance after working on strengthening and fine motor activities?

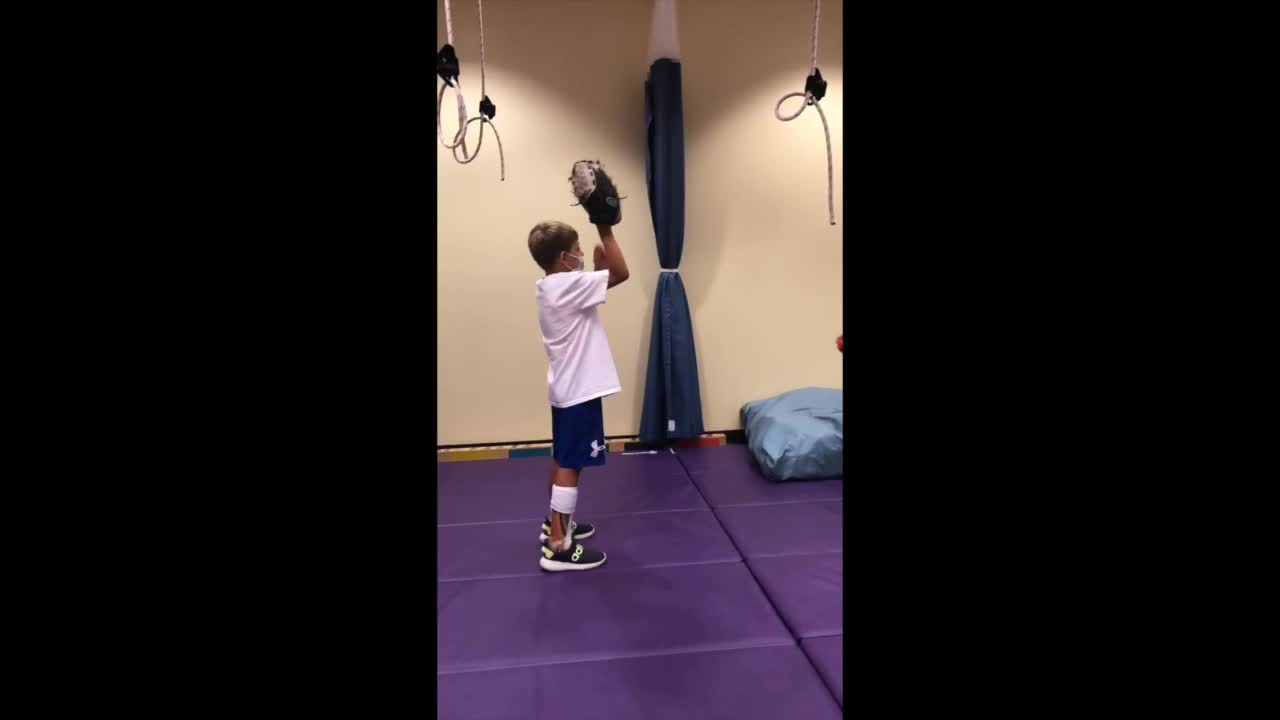

This video is a traditional bottom-up approach with a kid with CP. He is doing constraint, where he has a cast on the less impaired arm so that he will use the impaired arm more. I love constraint, but we must ensure we do it at the right time for the right outcomes.

Video 1: Bottom-Up Approach

It gets kids more function in their impaired limbs, but how sad is he? It is just not for everybody all the time. In this session, I felt it impacted his quality of life and confidence. He was so sad wearing that cast, and why wouldn't he, especially when he could do so many things without the cast?

Top-Down Interventions

Top-down starts with the question, "What do you want to do, and what is getting in the way?"

Figure 12. Top-down approach.

Again, it can be an impairment, weakness, lack of range of motion, a bag that is not easy to open, or whatever. Then, we examine whether it is an impairment in the body, an environmental mismatch, or because the person does not know how. We want to know what is getting in the way, not what's wrong with the person. This next video is the same child using a top-down approach.

Video 2: Top-Down Approach

He is still frustrated and not necessarily successful, but he is working on the things he wants to do. We are using a task-based approach. Coming at activity from the top is not necessarily CO-OP.

Summary

- Top-down, function-based, task-based interventions directed at activities & participation are most effective for facilitating functional outcomes in children.

- (Cahill & Beisbier, 2020; Novak & Honan, 2019; Pless-Carlsson, 2000; Polatajko & Cantin, 2006; Hillier, 2007; Smits-Engelsman et al., 2013; Preston et al., 2017)

- CO-OP is top-down, function/task/occupation-based, client/family-centered; directed at the activities & participation levels, and has demonstrated generalizability and transfer

- (iCan bibliography; Blank et al., 2019; Capistran & Martini, 2016; McEwen et al., 2014; Sugden, 2014; Polatajko & Mandich, 2004)

Research shows that top-down, function-based, and task-based interventions at the activities and participation level on the ICF model are most effective for facilitating functional outcomes. Hopefully, we want functional outcomes as OTs. CO-OP is occupation-based, client-centered, and directed at the activities inpatient level, and it shows generalizability to other environments and transfers to other tasks. Hence, it is a good fit for us.

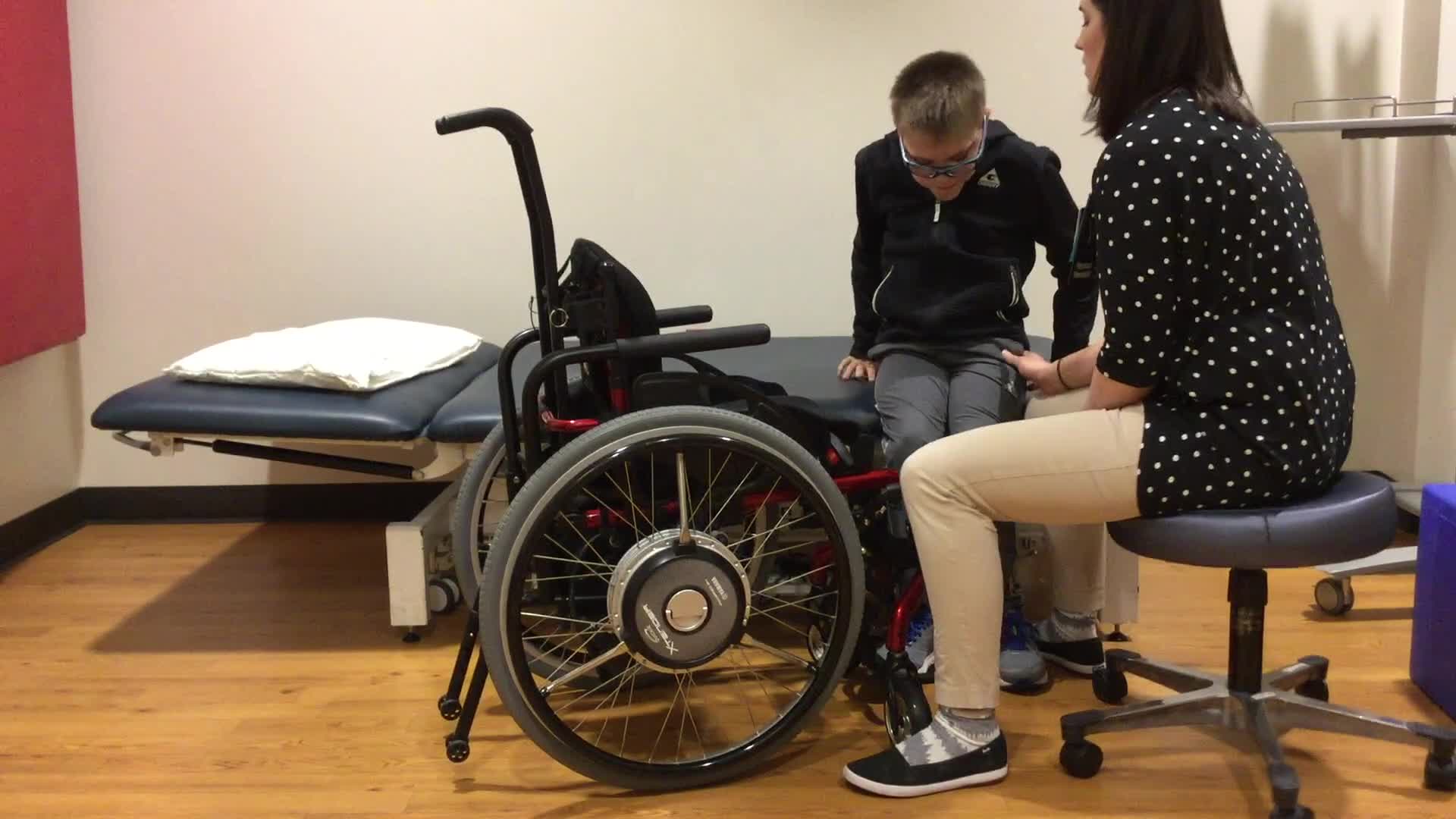

This is Braiden again working with his PT. She was frustrated because she was working on the things he wanted to do, but he was not making many gains. We worked together using a CO-OP approach, which opened things up to various solutions. This is what they came up with for baseball.

Video 3: CO-OP

When using CO-OP, we figured he might not need a glove. Putting a dystonic hand into a baseball glove is hard. Do you put it on the better hand or the worst hand, and do you take it off to throw it? With him, we just could not get there. The PT came up with the idea of him deflecting it instead. He is using his better hand to deflect it and throw with his good hand. Look how excited he is. He is on a local team, and they are going to the Little League World Series soon. It is so exciting, and that is everything to me. If he was obsessed with using a glove, we could get there too, but his goal was to catch and throw.

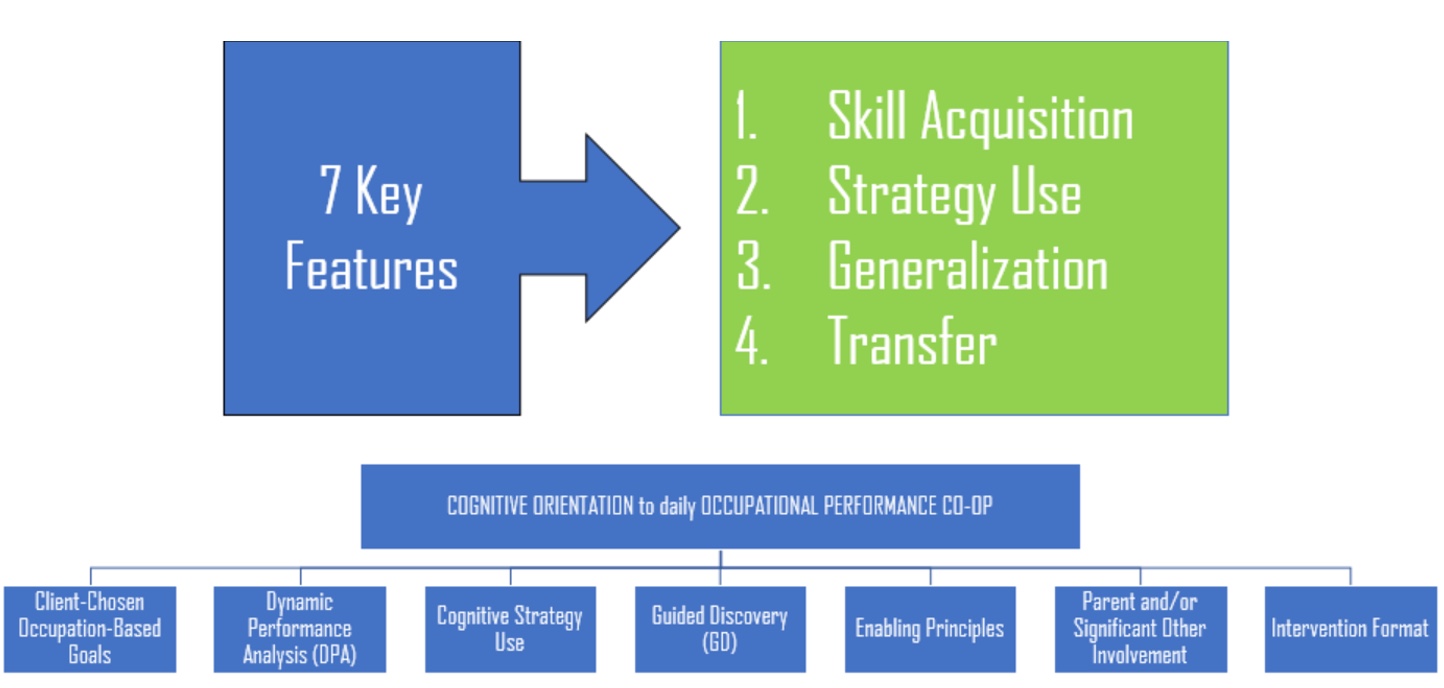

Using The CO-OP ApproachTM

Let's break it down a little bit. A lot goes into the CO-OP approach, but I am giving you a little taste. Figure 13 goes over the 7 key features.

Figure 13. Seven key features of CO-OP. Click here to enlarge this image.

There are four main goals of CO-OP: skill acquisition, strategy use, generalization, and transfer, with seven key features that lead to these four main goals. You have them in a handout. It does not matter if you know the key features, but take tidbits from this so that you can change the direction of your practice. It is so doable.

7 Key Features

- Client-chosen, occupation-based goals

- Dynamic Performance Analysis (DPA)

- Cognitive strategy use

- Guided discovery

- Enabling principles

- Significant other involvement

- Intervention format

Key Feature 1: Client-Chosen Occupation-Based Goals

- Client Pre-requisites

- Functional goals

- Sufficient language fluency

- Basic cognitive skills

- Behavioral responsiveness

- CO-OP is not for everyone.

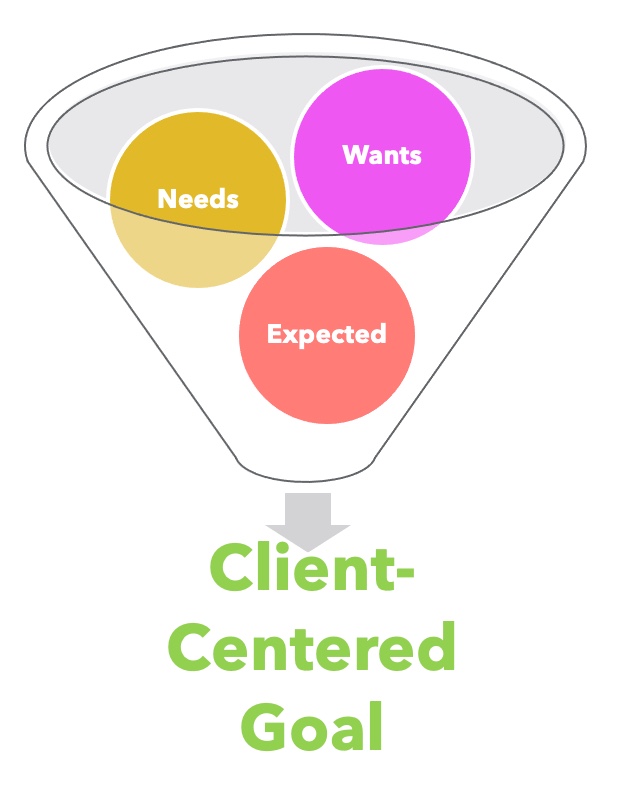

Client-chosen occupation-based goals are represented in the graphic in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Client-centered goals focus on wants, needs, and what is expected.

Therapy has changed in the past five to 10 years. We used to approach the client to assess their impairments and then set goals to fix those. Today, we know that if we work on something important to the client, they do it more and practice at home. There is much more momentum. Client-centered goals are anything that the child needs to do, wants to do, or is expected to do. Most people do not want better handwriting, but it is an expectation. All of those things go into a client-centered goal.

To use CO-OP, the client has to have the cognitive ability to want to do something better and be able to state it. With CO-OP, having kids with more language is good because it is a significant give-and-take process. You can have kids with limited language, and you will see some videos, but they must have basic cognitive skills and behavioral responsiveness. It is not necessarily for everybody.

- Goal Setting

- Tools

- Conversation with client/significant other

- Framing occupational goals

- Delimiting occupational goals

- Daily Log

- PACS/ACS

- COPM

- Establishing baseline performance PQRS

- Tools

There are many ways to assess goals. You can do this during an occupational profile, evaluation, interviewing the family, or using the COPM, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. You need to come up with what they want to do. I encourage you to be open to whatever they want and delimit those occupational goals. For instance, if you are working with someone in a wheelchair who wants to run a marathon, have a discussion. This can lead you in directions that you did not expect.

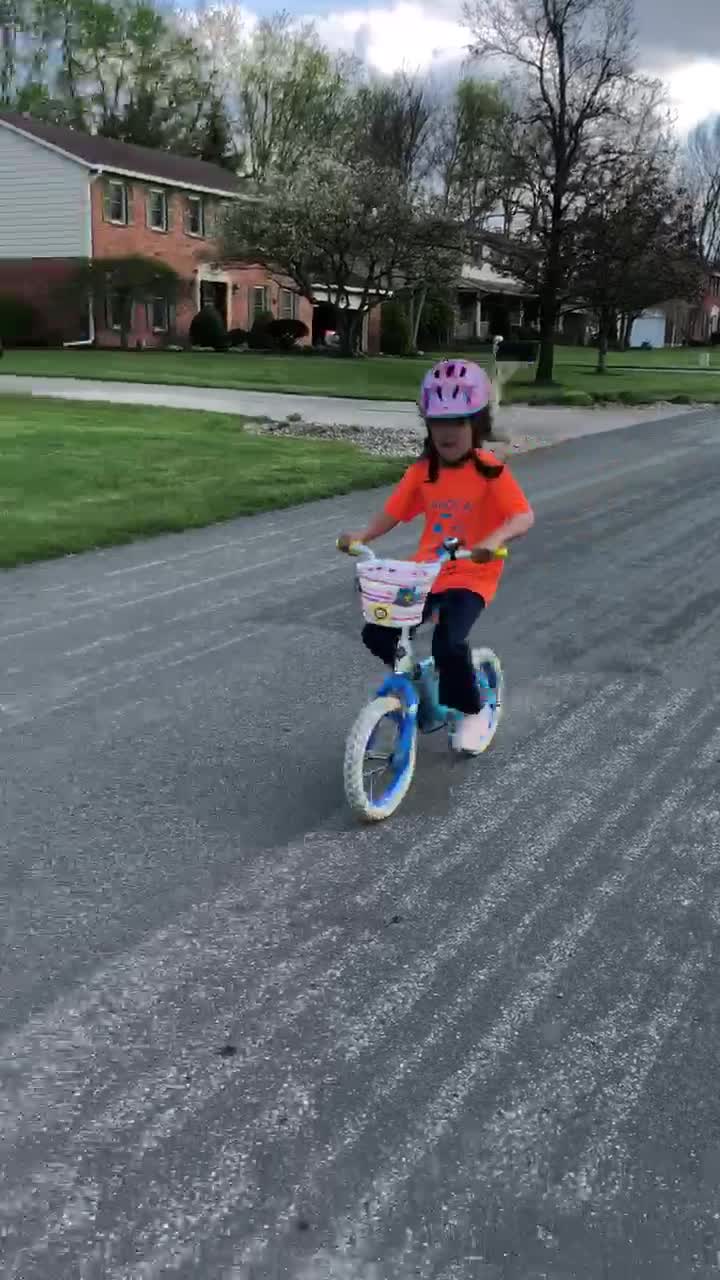

An example would be Grace riding a bike. I would not have thought that was possible. I want you to approach clients with, "Let's talk about it," as it may lead us to other paths. Be brave and delimit some of those goals.

Client-Centered Goals

- From a parent -

- "I didn't think that learning to be a goalie was a good goal for therapy. I thought writing was the important thing. Well, I have to tell you that he learned to be a good goalie with you, and then he made the school floor hockey team. They went to the championships and won. He is living his dream!"

(Mandich et al., 2002)

This is from the original CO-OP book from a parent. Achieving something important to the child pushes improvement in other areas. It is so powerful.

Figure 15. The importance of client-centered goals. Click here to enlarge the image.

We will improve measurable things if we work on things from this body functions and structure level, like therapeutic exercise and repetitions. Perhaps, they will improve their strengths so that they can do more coloring. And we are hoping that they will use those new gains to do more activities. However, strengths will only be maintained if they continue to do the exercises that we were doing, and who does exercises forever? My clients do not, nor do I. I cannot get my kids to practice piano before piano lessons the next week.

In contrast, if you are working on something the child wants to do, the child improves on their own with more generalizability. Body functions and structures may improve with improved participation, but does it matter if they have improved in something we can measure? The whole point is that they do what they need and want to do. Here is another example.

Key Feature 2: Dynamic Performance Analysis

- Objectives

- To ensure client-centeredness

- To identify performance problems

- To identify potential strategies to enable performance

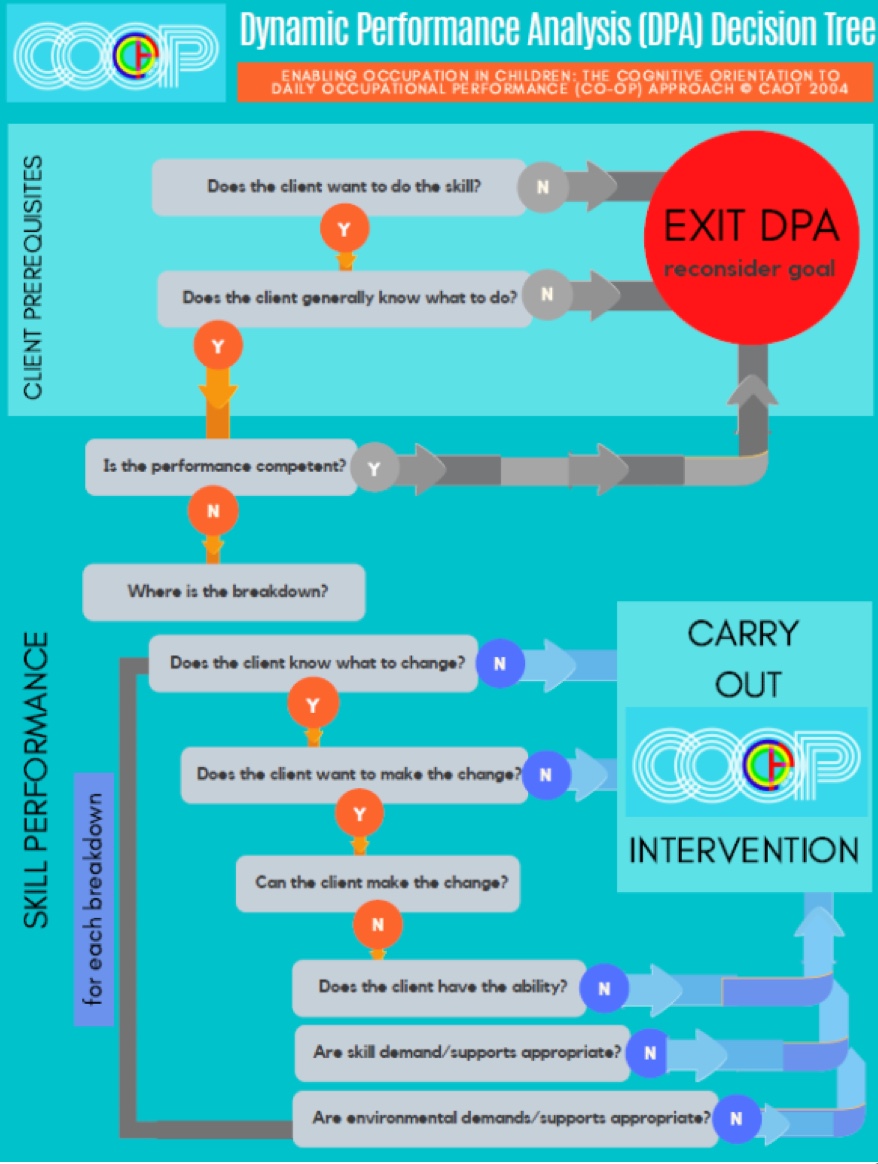

Dynamic performance analysis is where we figure out what is going wrong in whatever they want to do. You have this decision tree in your handouts in Figure 16.

Figure 16. Decision tree for dynamic performance analysis (DPA). Click here to enlarge the image.

It is complex and works through a series of questions to figure out where we start to intervene. It starts with, "What do you want to do?" If they want to ride a bike, I may put a bike there in front of them so they can show me what they can do. Sometimes, they do not even know how to approach the bike. Other times, they get on it and ride away. In this case, the barrier to riding the bike was that they never tried because they thought they could not do it. You find out more information by assessing their baseline.

We may ask, "What can you do?" Then, we intervene when something goes wrong. This is different from task analysis.

Task Analysis or DPA?

- Task Analysis

- What is the underlying problem?

- Where are body impairments?

- Component Analysis

- DPA

- What is wrong with the whole picture?

- What's going wrong with the person, environment, task

- Behavioral Analysis

Task analysis is what we were trained to do. Even when I am working with students on CO-OP, they want to go right to "what's the problem?" They may have no core strength, poor grasp, or not use both arms. Task analysis looks at underlying problems and impairments. We are looking at all the pieces that contribute to the performance. While this is not wrong, we get improved function with CO-OP and dynamic performance analysis.

Dynamic performance analysis is asking what is wrong with the whole picture. We are taking into account the environment, equipment, and the client's emotional state. Are they nervous or excited?

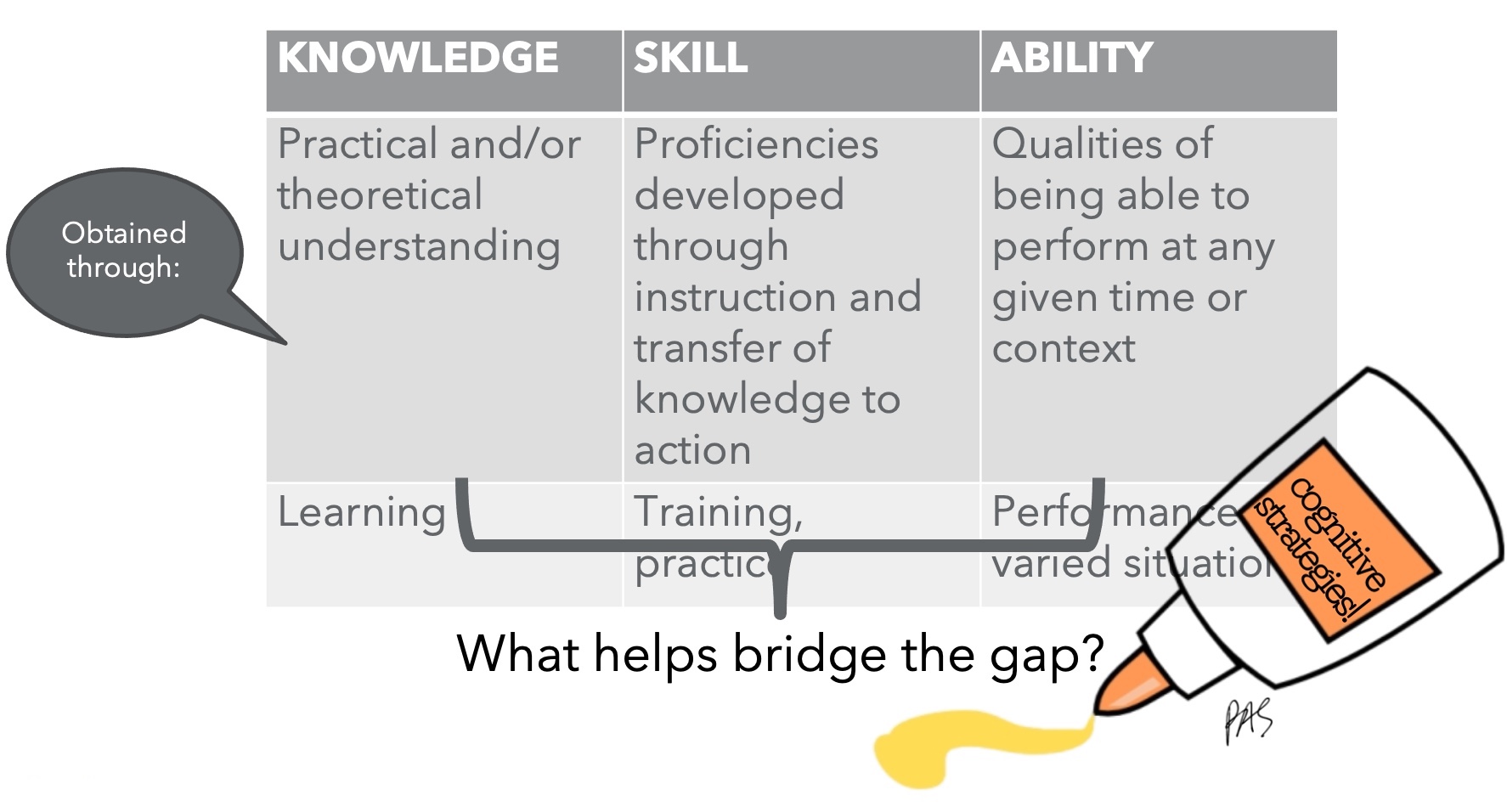

Key Feature 3: Cognitive Strategy Use

- Cognitive Strategy:

- a cognitive tool put into place to help learn, memorize, and problem solve

- a goal-directed, cognitive operation used to facilitate learning and problem solving

Cognitive strategy use is the meat of CO-OP. It is a cognitive strategy that we put in place to help us remember or learn something.

Figure 17. Overview of cognitive strategy use.

We all use cognitive strategies. For example, our passwords are based on something we know or remember. We also put our keys in the same place.

Skill is proficiency through the transfer of action or training and practice. Knowing the alphabet takes a lot of thinking and practicing it repeatedly. Then, you can write it automatically after performing the tasks in varied situations.

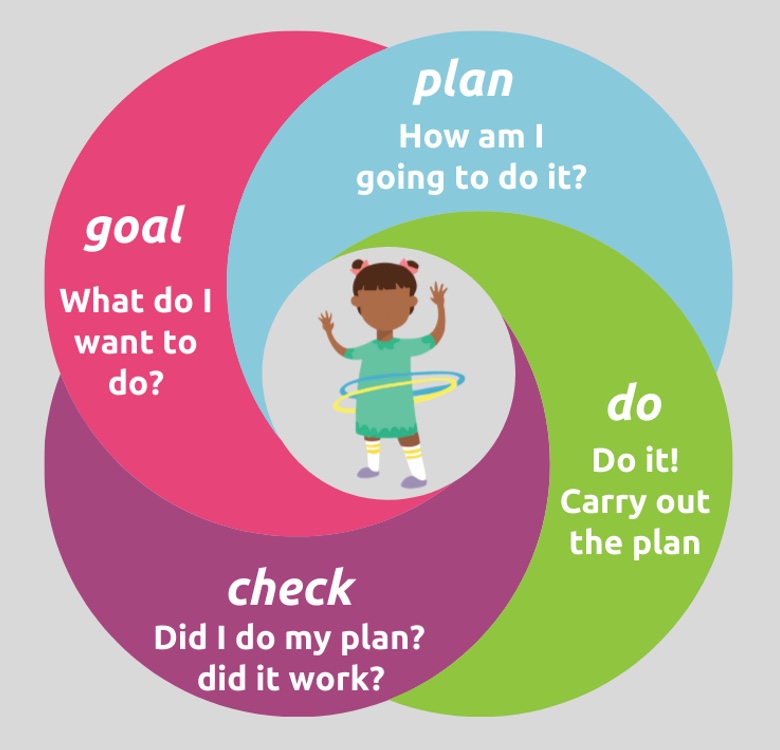

Cognitive strategies are what get us there. CO-OP is based on a main cognitive strategy called goal-plan-do-check. This is what we are bringing to kids (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Goal-Plan-Do-Check strategy.

We are finding out what they want to do and then looking at the first thing that goes wrong. We then look at the goal again and ask, "What do you want to do?" It could be to write all the letters, or it could be writing the letter "A" without having to erase it. We then need to help them plan how to do it. This is what we are developing in therapy. They then make the plan, do it, and then check it.

Children are not used to analyzing their performance. We need them to stick with a plan to ensure it works. Here is an excellent example. The audio and this child are quiet, but the therapist does repeat most of what he says.

Video 4: Goal-Plan-Do-Check

Please reflect on how this looks different from what you have done or are doing. For me, it looks different as it is not as therapist-directed. The therapist is not the boss there, which can be challenging. It involves a lot of questioning and using the child's words. Goal-plan-do-check is the primary strategy that we are using in CO-OP, but there are also other strategies that we can access. The CO-OP Academy refers to them as domain-specific strategies.

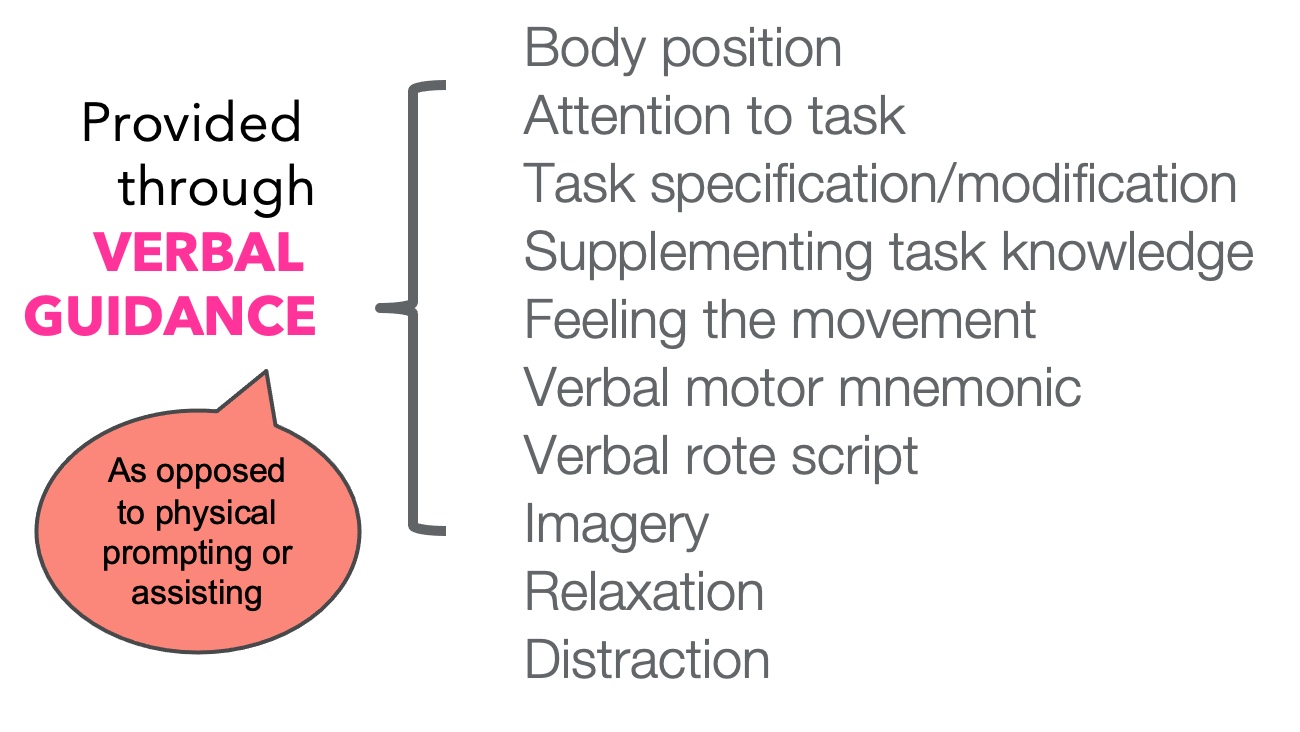

These are the tools we have to pull the plan out of the child. We need to use our knowledge about the person, the task, and the environment to help facilitate that planning in the child.

Domain Specific Strategies

- Unique for each person performing an activity in a certain environment

- The therapist uses performance knowledge about the person, task, and environment, so the child discovers his own strategies and solutions.

These are the domain-specific strategies. It is not essential to know their terms or memorize them, but we have the tools at our disposal. Through verbal guidance, not our hands, we want to facilitate the child to think through these things (Figure 19).

Figure 19. Different features of verbal guidance.

We want to use our words, not our hands, to cue them about body position. We can ask, "Where are your hands?" We want them to attend to the task. We can ask, "What are you thinking about?" We can draw their attention to the task or modify it. "Do you think it'd be easier to use something different?" We can supplement their knowledge and ask, "Do you know how to do that?" If they do not, we can ask them, "How can we find out?" Perhaps, they can feel the movement. "How does it feel? Is it hard or soft?" We can use verbal mnemonics or a verbal script, which I always use. Whatever is helpful to the child. Have them imagine doing it and practice it that way. Sometimes they just need to relax. They are trying so hard or using distractions to get their minds off all that thinking.

Here is another example of using strategies. Zoe wants to ride a bike like her sister. She does not seem to mind which bike she uses. She is lower-level and is very quiet. I am throwing things out there and see if it sticks. I am using words that might make sense to her mental plan.

Video 5: Strategy Use

Is she weak? Absolutely. She has terrible core strength and is uncoordinated, but I am not working on any of those components. I am working on her riding the bike. First, I am making sure we are using the same terms to cue her to move her leg in the way to move the bike.

Key Feature 4: Guided Discovery

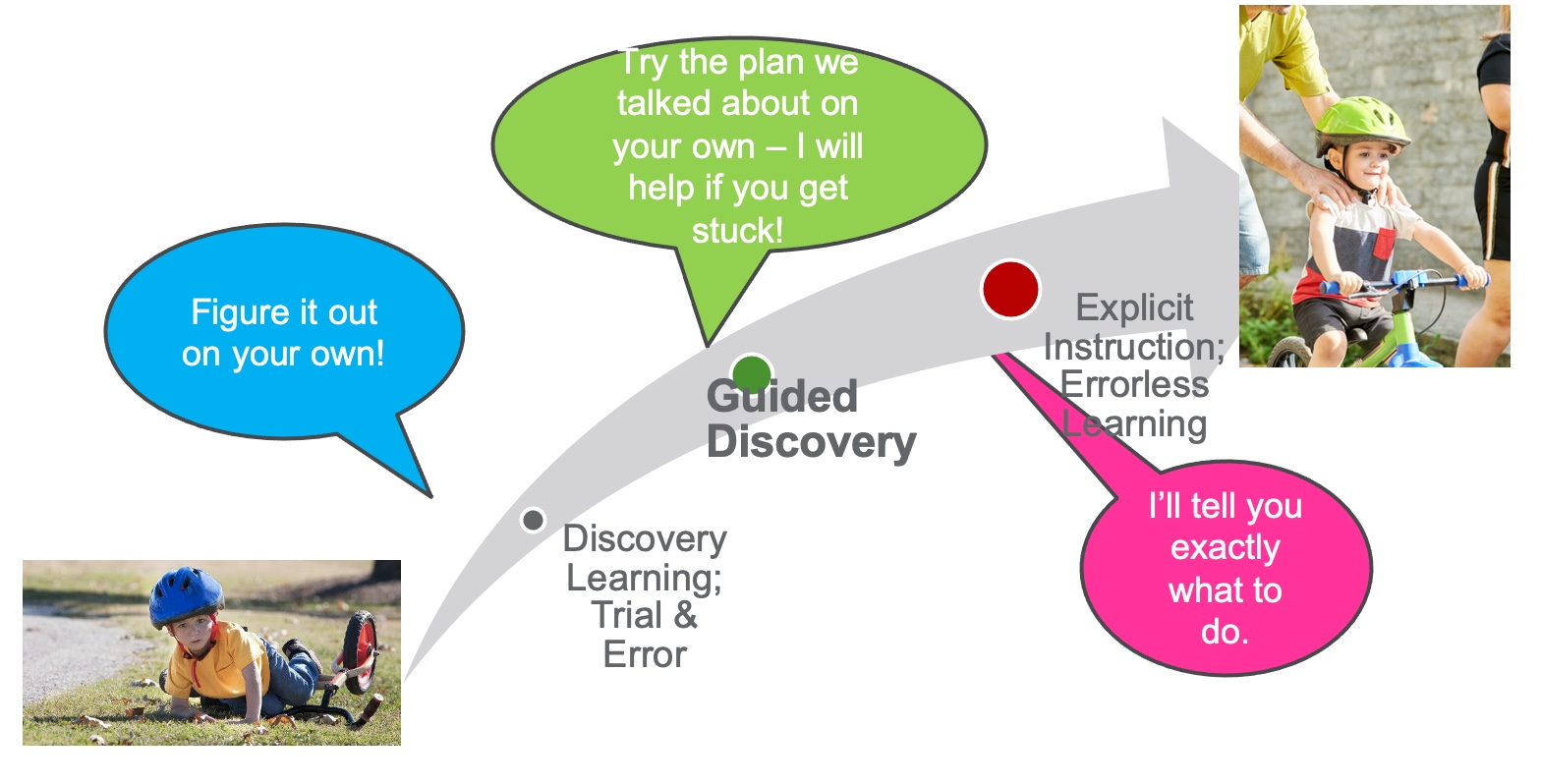

Guided discovery is how we help kids problem-solve. We must let kids experience the problem, especially kids with disabilities. We like to protect them, so they do not fail or feel bad about themselves.

The Power of Problem Solving

- Because self-esteem actually comes from facing difficult challenges and successfully overcoming obstacles, kids need a chance to solve problems by themselves. Dr. Susan Hales

Problem-solving gives children the robustness and feeling they can survive in the world.

This is in contrast to us saying, "I'm the expert. Just listen to me." For example, I know a cute story about a bunny that goes through a hole to help someone learn to tie their shoes, except it does not. With this method, we are backing off and thinking that perhaps we do not know the best way. Instead, what can we come up with together? The problem-solving is so powerful.

- Each time one prematurely teaches a child something that he could have discovered himself, that child is kept from inventing it and consequently from understanding it completely. (Piaget, 1970)

Again, we are trying to get kids to come to this aha moment. Have you ever experienced something where it finally clicks? You may have thought, "If they had explained it this way, I would have understood it." We are trying to drive kids to that moment where it clicks. CO-OP does that for kids.

Guided Discovery Definition

- A means of providing both instruction and feedback during the learning process in which the learner is encouraged to solve problems independently but is guided by a knowledgeable instructor who questions, coaches, cues, or hints.

It is not teaching. I am helping them to figure out what works. The challenge is twofold.

- Challenge #1: how to specify the desired outcome of learning

One, we want them to learn something and need to specify how to do it. I want the pedal to go a certain way, but how do I get there?

- Challenge #2: how much and what kind of guidance to provide

Two, how much and what type of guidance should I provide?

Trial and error learning is where they figure it out on their own, and the other end of the spectrum is where we tell them exactly what to do, which is errorless learning. Guided discovery is in the middle.

Figure 20. Instructor control continuum.

We want them to try what we discussed, but we will help them if they get stuck. We also let them fail if we think they can tolerate it.

We will talk about how the plan was wrong, not them.

- One thing at a time

- Ask, don't tell

- Coach, don't adjust

- Make it obvious

Here are four main things that go into guided discovery. We will do one thing at a time and figure out the issues. With Zoe, we focused on kicking that leg forward to move the pedal. For ask, do not tell. I toss things out instead of saying, "Do it my way." I am coaching and not adjusting by only using my words and not my hands. Lastly, I make it obvious when needed.

Ask, Don't Tell

- Keep the questioning focused on the performance problem

- Avoid yes-no questions

- Be sure they have the knowledge to answer

- Use closed questions to focus attention

- Use open-ended questions to promote critical thinking

- Use choice questions if open-ended questions are too hard

- Be sure to allow 'wait time' for thinking to process

- Periodically summarize what has and what has not been dealt with and/or resolved

It is almost like a reflex for us to teach and tell, and it takes a lot of practice. We must stop and ask, "How do you think you should be doing it?" Or, "Do you think you should use it hard or soft?" It is also vital to avoid yes and no questions. We want to draw their attention to what is going on and can offer choices if we think the questions are too complicated.

Something hard for me was allowing some wait time for them to answer. Suppose you want to reflect on your practice, video yourself. It is uncomfortable at first, but it is powerful to see what you do versus what you think you are doing. It made me increase my wait time, ask more questions, and get my hands out of the way.

Make It Obvious, Slowly

We also want to make it obvious, but slowly. If I am trying to draw their attention to a toy in the room, I may start with the room. I may say that it is over on this wall or that it is square. I may then say it has three colors. I am giving hints but want them to be part of the solution. Here is an example of some guided discovery.

Video 6: Guided Discovery

The goal was to eat a cup of oranges without the orange cup falling on the floor using her helper hand.

Examples of Plans

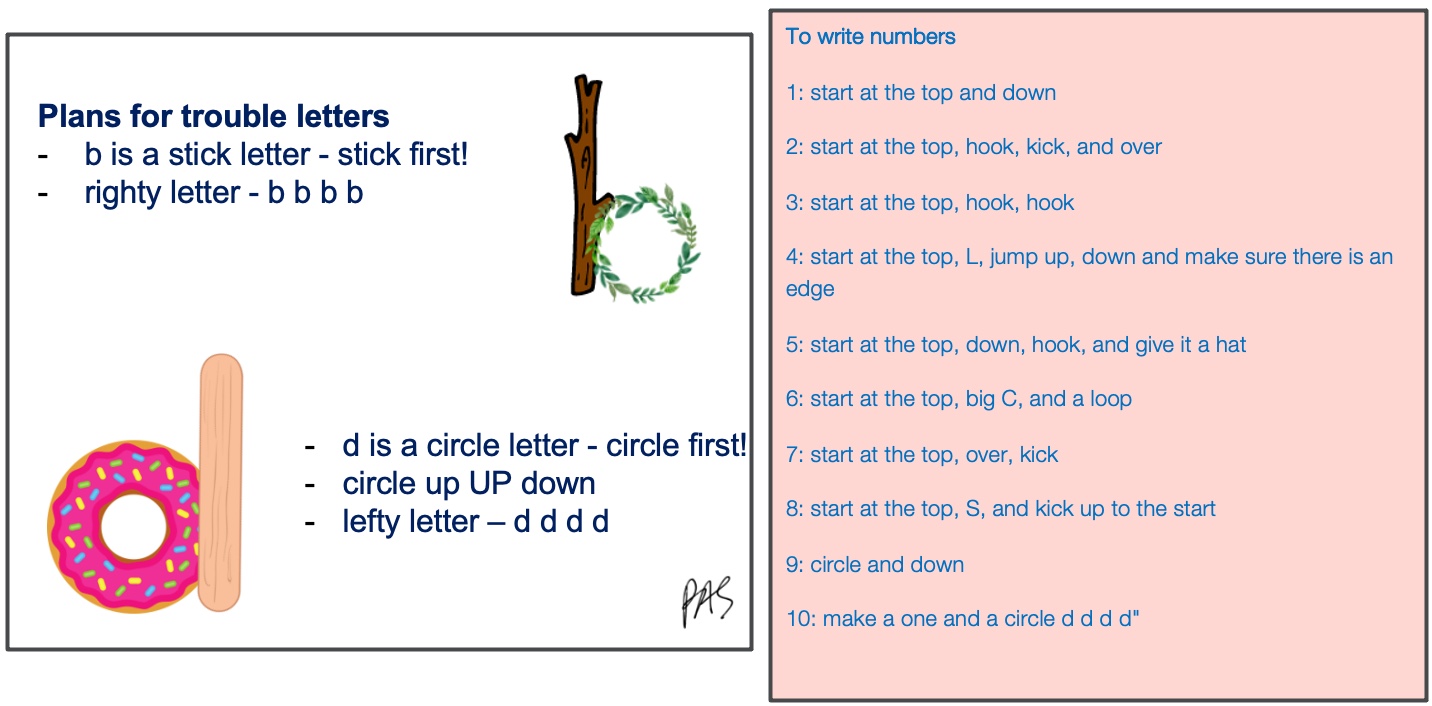

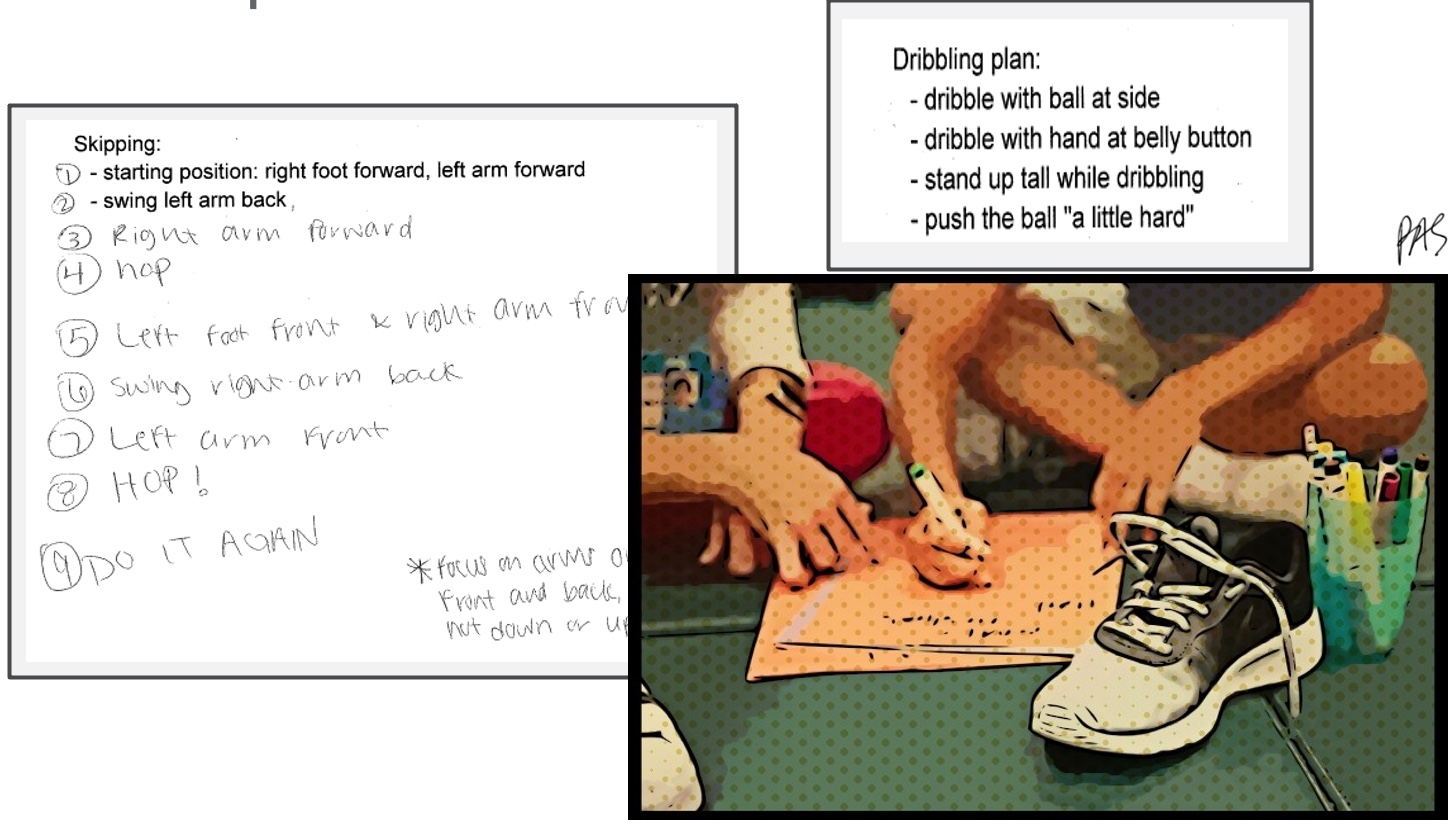

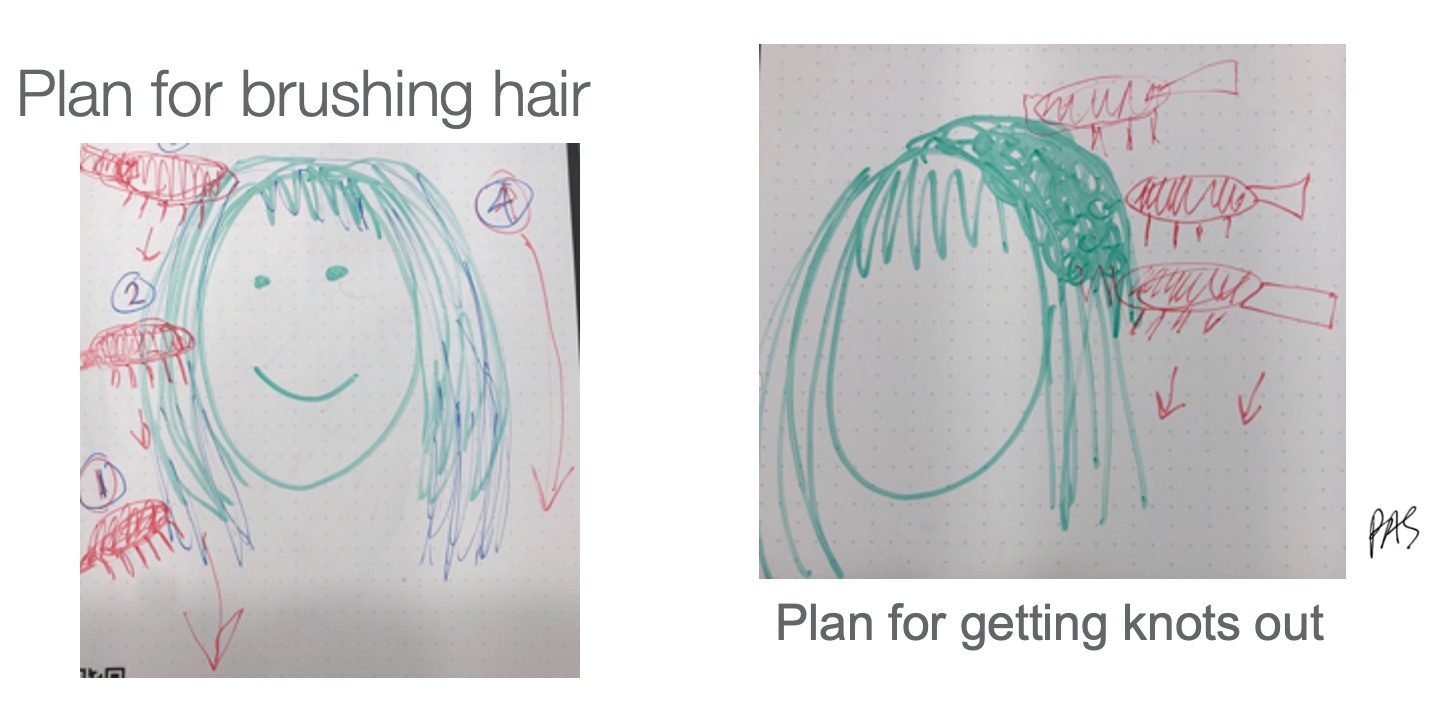

Plans can look many different ways with CO-OP, and I have never written a plan that looks the same as another. Before, I made similar plans, but they did not get the same results. Here are many examples.

Figure 21. Examples of plans for writing letters.

Figure 22. Examples of plans for skipping, dribbling a ball, and tying a shoe.

Figure 23. Examples of plans for brushing hair and getting knots out.

It can be in a picture. This is one for brushing hair. This is how we do it. And this is coming up with the child. , last little bit here,

Key Feature 5: Enabling Principles

- Make it fun

- Promote learning

- Work towards independence

- Promote generalization and transfer

Enabling principles are things that I think pediatric therapists already do. Being silly helps keep kids engaged. We also want generalization to other environments. This is CO-OP being done in a session and how it is transferred to the home.

Video 7: Generalization

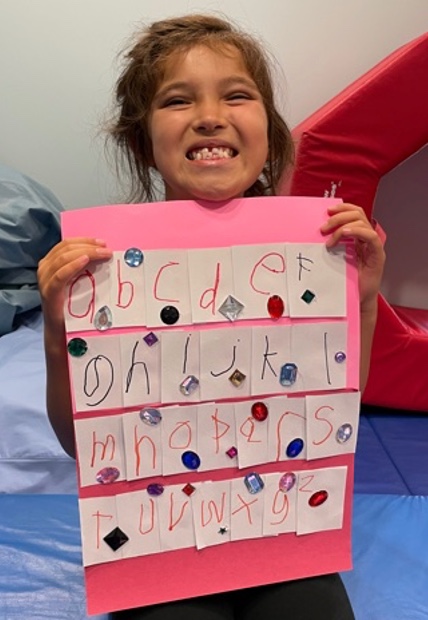

She is saying the plan that we came up with for each letter. I think Handwriting Without Tears is great, but magic C does not make sense to many kids. Every kid has a different vocabulary, so I have to write it down because I cannot remember.

Transfer to Other Skills

- Transfer – when strategies can be applied to problem-solve a completely different action or skill

- CO-OP has shown transfer to untrained goals (Capistran & Martini, 2016; McEwen et al., 2014; Sugden, 2014)

With CO-OP, we work on figuring things out in the clinic, and they come back with new skills, like hula hooping. I see an increased willingness to try things and also the ability to figure them out. With his little girl, we worked on her letters (Figure 24). Lo and behold, she figured out how to ride a bike.

Figure 24. Client with the completion of her alphabet.

Video 8: Transfer

It was not like it just magically happened. However, her mom carried over some of the skills, like asking what was going wrong and making a plan. The magical unicorn in the therapy world is when they solve their own goals.

Key Feature 6: Significant Other Involvement

- CO-OP focuses on goals of client, and client is focus of intervention.

- However others are often involved

- Parents, grandparents, teachers, spouse, children, personal support workers

- How?

- Goal setting

- Homework completion

- Intervention – strategy use

- Transfer and generalization

Parent and significant others' involvement are key in setting goals and practicing at home. If they are involved, we try to teach them to use the same questioning and queuing so they can use it at home.

Key Feature 7: Intervention Format

- Pre-Intervention

- Send out daily log

- Client to identify 3 goals using PACS, COPM

- CO-OP Intervention Sessions

- Session 1: Teach global strategy – GPDC

- Sessions 2-10:

- Apply GPDC to occupational goals

- Use GPDC to identify appropriate DSS

- Homework

- Between all sessions

- Post-Intervention

- Re-evaluate performance

Traditionally, CO-OP is one-on-one and involves approximately 12 sessions. They do homework in between. If you can add little bits of this in your therapy and ask questions instead of giving instructions, you can start to transform your practice.

CO-OP Variants

- Groups

- Clubs

- Camps

- Telehealth

- Emerging evidence supporting use of CO-OP in conjunction with OT&PT delivered via telemedicine.

- "Telerehabilitation shows promise as a way to deliver the CO-OP approach and may help promote community integration of individuals living with TBI" (Ng et al., 2013).

Evidence shows it works in groups, clubs, and camps. I am doing a CO-OP Fine Motor Camp right now. It is a ton of work, and it is crazy. I do not know how teachers do it. However, it has been tremendous and surprisingly effective. It also works well via telehealth because it is verbal interaction.

Reflection and Application

I want you to think of somebody that might benefit from this. Are you stuck on goals? It is so transformative, and you can get some excellent outcomes when using it. What scares you about it or makes you nervous? I was worried that if I did not focus on body functions and structures, I was not doing my job or was not smart enough.

Applying CO-OP in Your Practice

- Will you use the CO-OP approach?

- With whom?

- Which potential client goals would you address with CO-OP?

- What GOALs do you hope to achieve for your clients and yourself?

- What outcomes do you anticipate?

- What is your PLAN?

- How can you be supported?

- What will your CHECK be?

Letting go of some of those preparatory activities has given me time to work on the things that matter.

Reflection

- What hesitations do you have about using more top-down approaches like CO-OP?

- What fears do you have about reducing emphasis on body structures & functions?

- What clients have you felt "stuck" with?

- What are you hoping to gain from trying the CO-OP approach?

Resources

- ICAN - International Cognitive Approaches Network (formerly the CO-OP Academy): https://icancoop.org/

- CanChild - Valuable information for clinicians & parents on various childhood conditions: https://canchild.ca/

- CanChild on DCD: https://canchild.ca/en/diagnoses/developmental-coordination-disorder/workshops

- Cincinnati Children's Hospital: https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/

Here are some resources from the CO-OP academy. CanChild is a wonderful resource on some of these things. CanChild on DCD just to get your understanding of it. They've also got a page on CP.

- ICAN - International Cognitive Approaches Network – Workshop Schedule: https://icancoop.org/pages/upcoming-workshops

You can visit the ICAN CO-OP website or reach out if you want to look into additional CO-OP training.

Questions and Answers

Who does the MACS level testing?

It is not an assessment but rather a way to classify them. You can just look up the information.

How do insurance companies reply to this type of training?

It falls under therapeutic activities or neuromuscular reeducation because we train the brain to use the body differently and improve function.

Instruction leads to dependency, while CO-OP leads to decision-making and feedback for the therapist.

Absolutely, woohoo!

How do you bill for this without many objective measures?

We use objective measures, like the COPM, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, or Goal Attainment Scaling. Both of those are standardized outcome measures. The PQRS is another one where we assess the level of performance and satisfaction with a goal. There is also the FIM and the WeeFIM.

Would I be able to give some treatment therapeutic activity examples of your fine motor camp via telehealth?

I have one child who is attending virtually. Intervention is not that different via telehealth because you use your words instead of your hands. It is conducive to doing that. I am only going to do the fine motor skills that are functional. We talk about the different parts of the paper, strokes, and other types of letter parts like "bellies," "sticks," and "overs." We also figure out how letters are formed together.

Has CO-OP ever been used in the geriatric population for post-CV?

There is a ton of data on CO-OP post-stroke, both acute and chronic. Tim Wolf has some research that shows the cool transfer of skills in the stroke population.

Does CO-OP address the prevention of loss of function or regression?

Not directly, but if you keep functioning and participating, you will not regress or lose function.

I hope that answers your questions. Please reach out to me if you have any further questions. I would love to problem-solve anything with you. I hope that this inspired you a little bit to change things up and to try some new stuff.

References

Please refer to the additional handout.

Citation

Sharp, P. (2022). Cerebral palsy review: Facilitating functional outcomes. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5545. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com