Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Cerebral Palsy Review: Medical and Therapy Management, presented by Patti Sharp, OTD, MS, OTR/L, BCP.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- Recognize various classifications of cerebral palsy.

- List options for medical and surgical management of cerebral palsy sequelae.

- Identify evidence-based recommended therapy interventions for improving function and participation in children with cerebral palsy.

Introduction

Thanks for joining me today for the second course in a 3-part series. We will review the medical and therapy management of Cerebral Palsy (CP).

What is Cerebral Palsy?

- An umbrella term that describes a group of disorders in the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation that is attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occur in the developing fetal or infant brain.

My perspective on CP has changed, and I now understand it better. I want to give you detailed information about intervention so that you can feel comfortable treating kids with CP. I also want to provide an overview and discuss the importance of treating kids with this condition. I will zoom in, give you detailed information, and then zoom out so you can put it together.

CP is an umbrella term that describes a group of disorders in the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitations that are attributed to non-progressive disturbances in the developing fetal or infant brain. It describes a big group of things that happen to the infant's brain before birth, during birth, or shortly after birth.

The damage to the brain causes cognitive and motor impairments. When talking about CP to families, they often think of a more extreme version, like a child in a wheelchair with no movement and limited speech. Instead, it includes various symptoms, so we want to ensure that we convey that.

What CP Is Not

Cerebral palsy is non-progressive, and brain damage has already occurred and will not change. It does not get better and does not get worse. Secondary conditions can follow from brain damage that can change over time and worsen. However, this does not mean that the brain damage is worsening. CP is not infectious or a disease that you can catch. Although CP is not curable, therapy can help to improve function and quality of life.

When Can You Identify CP?

- Typically not diagnosed until 12-24 months (Rosenbaum et al., 2007)

- Newer research indicates that CP can be accurately predicted or diagnosed as "high risk for CP" before 6 months (Novak et al., 2017).

Kids used to be identified as having CP when they were three to six years old as pediatricians had a wait-and-see approach. Newer research shows that we can and should identify it early because outcomes are better. Parents also want to know. We can increase a child's quality of life if we identify and treat CP earlier, even before six months.

Infant Detectable Risks

- These signs prompt further evaluation for CP (Novak et al., 2017).

- >4mo

- Persistent hand fisting

- Persistent head lag

- >6mo

- Not supporting weight through plantar surface of feet when placed in standing

- >9mo

- Not sitting independently

- 6-12 mo

- Leg stiffness

- Asymmetries

- Hand preference before 12 mo

- Asymmetry in posture or movement

- >4mo

Above is a list of signs to look for in a child. For example, if a kid is still fisting or has a persistent head lag at four months, that is a risk factor for CP. These signs do not mean the child has CP, but you should investigate further. By six months, if they are not supporting weight through the plantar surface of their feet when standing, this is a concern. By nine months, they should be able to sit independently without a Boppy, pillows, or a hand. Any leg stiffness or tightness between the six to 12-month period is also a risk factor. Lastly, any hand asymmetry or asymmetry in posture or movement before 12 months is a concern.

What Causes CP?

Kids with CP cannot move in a controlled fashion, but the muscles are totally fine. They will weaken and atrophy over time with disuse, but there is nothing essentially wrong with the muscles. The nerves are also fine.

- Even though cerebral palsy affects muscle movement, it isn't caused by problems in the muscles or nerves.

- Instead, faulty development or damage to motor areas in the brain disrupts the brain's ability to adequately control movement and posture.

The insult to the brain before birth, at birth, or around birth causes targeted cell damage leading to motor impairments. CP is technically a brain disorder, but we work with the kids at a motor level. We are trying to get them to move and do things better, but we are not working directly with the muscle. We know that the damage came from the brain, and the brain cannot communicate with the intact muscles and nerves. We cannot eliminate that damage at this point, but we can take whatever communication the brain has with those nerves and muscles and improve it.

What causes it? Even though CP affects muscle movement, it is not caused by muscle and nerve problems. The faulty development or damage to the motor areas in the brain disrupts the brain's ability to control movement and posture.

- Complete causal path to CP is unclear in ~ 80% of cases, but risk factors are often identifiable.

- Risk factors can be identified in patient history during conception, pregnancy, birth, and postneonatal period (Nelson, 2008).

- Newer evidence shows that ~14% of cases have a genetic component (McMichael et al., 2015; Oskoui et al., 2015; Schaeffer, 2008).

What causes it? I wish we could tell, but most of the time, we do not exactly know what happened in about 80% of the cases. I think families want to know the moment it happened, as they want to focus on something. People related to parents of children with CP, like aunts and uncles, might think they want to do things better or differently so their child does not have CP. I believe families generally get some story of what led to the CP, for example, "I had a rough pregnancy" or "Oh, the birth was traumatic."

We can relate CP to a variety of risk factors. Research shows that about 14% of kids with CP have some genetic component. It is not necessarily a birth trauma or something that went wrong, but their genetics would lead to this anyway.

When Does The Damage Happen?

- Prenatal

- Genetic

- Congenital anomaly

- Infections

- Anoxia

- Metabolic disorders

- Intraventricular Hemorrhage (IVH)

- Perinatal

- Premature birth

- Prolonged or traumatic labor

- Anoxia

- Postnatal

- Vascular accidents

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Trauma

- Infections

When does that damage happen? As stated previously, we cannot tell. It can occur during any prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal periods.

Genetics/Prenatal: During development, the chromosomes put cells together a certain way, and the cells lead to some abnormality in the brain in the motor areas of the brain. It can be a congenital abnormality. As the fetus develops, something does not form correctly or fully, leading to brain damage that causes CP. Infections, anoxia, abnormal metabolism, stroke, or intraventricular hemorrhaging can cause CP in the womb. Some people may separate intrauterine stroke from CP, but it is the same. An intrauterine stroke can cause CP, but they can identify the causative factor in this case.

Perinatal: Premature birth is probably the biggest thing that happens. This is not necessarily stressful or traumatic labor, although that does happen. The vessels in those developing brains may not be strong enough and tend to burst, causing bleeding or anoxia in the brain.

Postnatally: Anything that happens within those first couple of months will be classified as cerebral palsy, including vascular accidents, strokes, intracranial hemorrhaging, infections, and anything that causes brain damage.

At our hospital, even children with non-accidental trauma or abuse resulting in brain damage are treated for CP. They are not traditionally diagnosed with CP, but their clinical course is the same as CP. We treat them in the CP clinic and have had some good outcomes.

Epidemiology

- Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common motor disability in childhood in the US. (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/cp/data.html)

- About 1 in 345 children in the US have CP

- Prevalence of 1 - 4 per 1,000 births worldwide

- Increased prevalence of CP for:

- Children born preterm or at low birthweight

- Significantly more common among black children than white children

- Hispanic children and white children are equally likely to have CP

CP is the most common motor disability in childhood in the US, with about one in 345 children in the United States. It is much more common than other things in young babies, like brachial plexus injury, which is only about one in a thousand.

The incidence is more, with one in four per thousand live births worldwide. And there is an increased risk for CP in preterm, low birth weight babies. There is more incidence of CP among African American children than white children, and we do not know why. Finally, Hispanic children and white children are equally likely to have CP.

Symptoms of CP

- CP

- Decreased muscle length

- Altered muscle tone

- Decreased muscle strength

- Decreased selective motor control

(Bax, 2005; Wright & Wallman, 2012)

As therapists, we do not deal with the brain per se or look at their scans. The four main things we see as OTs are decreased muscle length, altered muscle tone, reduced muscle strength, and decreased selective motor control. These are the things we will try to treat or prevent. This is what we will talk about today.

The great thing is that there is a lot of research on cerebral palsy. I work with other special populations, such as brachial plexus injury, developmental coordination disorder, burns, and various things, and these areas do not have much research on them. In contrast, cerebral palsy has excellent research on diagnosing, classifying, and intervening for kids with CP.

The more we can compile strong research, the better we can treat these kids. Every time I present on CP, I get excited because there is so much evidence. However, we need to tease out the main points I will give you today.

CP Classification

CP can be classified in a variety of ways.

- Tone & Movement

- Defines motor subtype

- Topography

- Unilateral or bilateral, UEs or LEs

- Gross Motor Function

- GMFCS

- Fine Motor Function

- MACS, Mini-MACS, AHA

- Communication

- CFCS

- Eating Function

- EDACS

There is so much research on this population that they have different recommendations based on the child's level. Specific categories can give you an idea of where to set your sights and expectations for your intervention.

The primary way that we can classify CP is by tone and movement. We will break it down into motor subtypes, which we will discuss in just a minute. Topography is where in the body the child is impacted. Gross motor function classification is probably the most researched way, using a GMFCS level. When we speak of fine motor control, this is broken down by an assessment called the MACS, which classifies how kids initiate use with their hands. CP can also be classified by how a child communicates and eats.

Classification by Muscle Tone

- What is tone?

- Continuous & passive partial contraction of muscles

- Muscle's resistance to passive stretch during resting state

- Tone is NOT the same as strength

- Strength is the amount of force a muscle can produce with a single maximal effort

- A spastic muscle can be weak, and a hypotonic muscle can be strong

Again, muscle tone and topography are the two most significant ways we classify CP. Tone is confusing to understand because it may present or look like strength, but it is not. Tone is a continuous passive partial contraction of muscles that is ongoing and not initiated by the child or the brain. It can be full tone, where the muscles are fully contracted for a given period, or anywhere in between.

We can test for tone when we passively move a child. When we move a child during a resting state where they are not doing anything (not sleeping), we will feel a catch (abnormal tone and spasticity).

Tone is not the same thing as strength. Strength is the force a muscle can produce with a single maximal effort. Kids with CP look super strong because they are so tight. Families may say, "Their abs are rock hard," or "Their shoulders are so strong that I cannot even move them." This is not strength.

I think of tone as volume control, and the brain is a radio. We can dial down or up the volume for any given task. Tasks require a different amount of control, and we adjust our tone without thinking about it. For CP, this is an oversimplification, but I think it is an excellent way to describe it.

In CP, a child's tone is either on or off, and the movement is not controlled. When a child with CP is not doing anything, they can be floppy, but when they try to reach for something, the whole body contracts. There is no separate control of muscle groups. This is a helpful way to explain strengthening to families because they may not think they need strengthening. Research shows that even kids with high tone have muscle weakness and poor endurance when we can elicit controlled movement.

When we break them down by tone, there are five motor subtypes: spastic, dyskinetic, ataxic, hypotonic, and mixed.

Motor Subtype: Spastic

- Caused by injury to the cortex

- Overactive muscles with increased tendon reflex activity and velocity-dependent resistance to stretch

- Usually not present at birth, develops over time

- 85-91% of cases (Novak et al., 2017)

Spastic is the most common and is caused by injury to the brain's cortex. There are overactive muscles whenever they have velocity-dependent movement. Anytime you pull a joint, you will get some spasticity. Spasticity usually is not present at birth, but it develops over time as the brain starts to communicate with the muscles abnormally. It looks like the CP is getting worse, but it is not.

Motor Subtypes

- Spastic (85-91%)

- Dyskinetic (4-7%)

- Ataxic (4-6%)

- Hypotonic (2%)

- Mixed

(Novak et al., 2017)

Most kids with CP are spastic (85-91%). The other three main types are ataxic, a Parkinson's type of movement, dyskinetic with choreiform movements (uncontrolled wavy movement), and hypotonic with flaccidity.

CP Population Distribution

- Unilateral spastic hemiplegic- 39%

- Bilateral spastic diplegic- 38%

- Bilateral spastic quadriplegic, Ataxic, and Dyskinetic- 24%

- Hypotonic- 2%

(Novak et al., 2017)

Above is the breakdown in topography or where the body is impacted. Hemiplegia is half the body, diplegia is the lower or upper portion (rarely seen), and quadriplegia is with all four limbs affected. A significant percentage of kids are either unilateral spastic hemiplegic, with spasticity on one side of the body. An equal portion of kids is bilateral spastic diplegic, with spasticity in the legs. The other types make up less than the other two combined; hypotonic is just a small percentage.

Most kids I see are hemiplegic, diplegic, quadriplegic, and some with ataxia.

Gross Motor Function

- In children with CP, gross motor function can be described in 5 levels using the Gross Motor Function Classification System GMFCS (Palisano et al., 1997) or the Extended & Revised version GMFCS-E&R (Palisano et al., 2007).

- Available free online on multiple websites

- Generally stable after age 2

- Do not assign before age 2 – period of rapid change

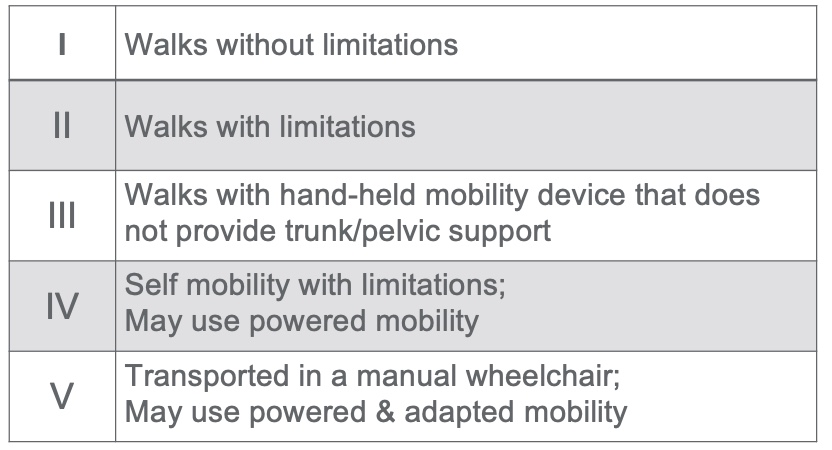

The next most common way therapists and physicians talk to each other is by gross motor function. Figure 1 shows the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS).

GMFCS-E&R General (Palisano et al., 2007)

Figure 1. Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS).

This system was revised and edited in 2007. It is free on multiple websites. In my first lecture, we discussed this scale in a little more detail. It lets us know what is coming in the future for this child and can guide treatment. We do not assign a GMFCS level until they are around two because many things change. As I said, the brain teaches the muscles what to do and develops tonal patterns. After two, the GMFCS level typically does not change. We are trying to work with the child at their current level, aiming to make improvements, but we are not necessarily trying to move them to a whole other level.

These classification systems are generally broken into five levels, one being the mildest impairments and five being the most dependent. For gross motor function, a one would be walking without limitations. There might be a gait abnormality or something that you might notice, but they can walk on all surfaces, go up and down stairs, and do not need special equipment or environments. GMFCS level two would be walking with limitations but not with a mobility device. They have trouble, trip, and might need assistance on stairs or surfaces. Level three is walking with a handheld mobility device, like lofstrand crutches, a walker, or anything that provides support. GMFCS level four would be self-mobility with limitations. This would include a self-propelled wheelchair, gait trainer, or a powered wheelchair controlled by the child. Level five is fully dependent for mobility and doing things.

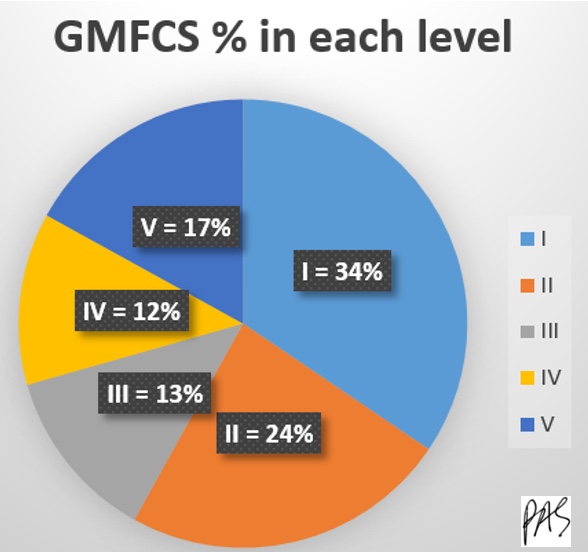

CP Population by GMFCS

Where do kids fall, according to the GMFCS?

- Compiled from

- Ohrvall, 2010, Sweden

- Reid, 2011, Worldwide

- Hidecker, 2012, US

- Christensen, 2014, US

- Novak, 2014, Australia

- Delacy, 2016, Australia

- Novak, 2017, Australia

- Mcallister, 2022, Sweden

Figure 2. GMFCS % in each level.

Luckily, most children fall in the first two categories, and almost three-fourths are in those first three categories. Most are in GMFCS level one, meaning they do not have total impairments.

Fine Motor Function

- Measured in kids with CP using:

- Manual Abilities Classification System MACS (Eliasson et al., 2006)

- Mini Manual Abilities Classification System Mini-MACS (Eliasson et al., 2017)

We measure fine motor function with the MACS, Manual Abilities Classification System, or the Mini-MACS, which is for younger kids.

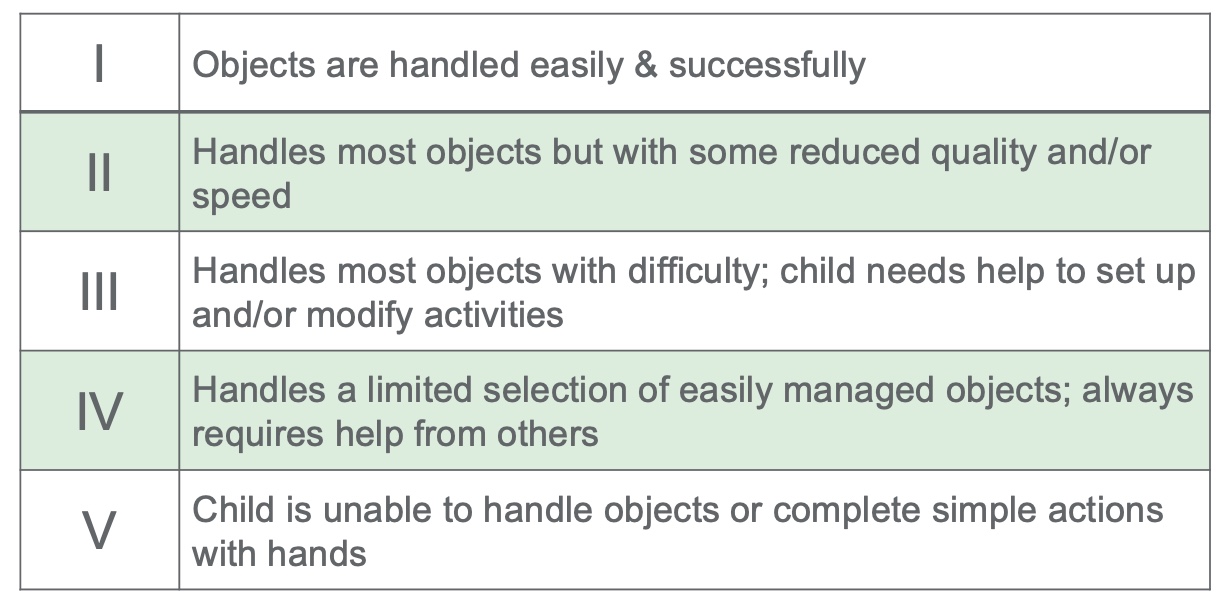

MACS (Eliasson et al., 2006)

- Describes how children ages 4-18 years with CP use their hands to handle objects in daily activities on a regular basis (not BEST performance)

- Considers overall abilities, not each hand separately

- 5 levels based on self-initiated activity, need for assistance, or need for adaptation

- Free online https://www.macs.nu/

The MACS describes how kids ages four to 18 with CP use their hands to regularly handle objects in daily activities. This looks at activities on a day-to-day basis, not only when they have the proper setup or when mom is telling them to do it. This is the same with a GMFCS.

It also considers the child's overall abilities, not each hand separately. If a child handles everything with their unaffected hand and can do it entirely without limitation, they would fall into a lower category of less impairment. We are not looking specifically at the impaired limb. There are other assessments, but we are looking at function in this case. This also has five levels based on self-initiated activity, need for assistance, and need for adaptation. This is also free and online in multiple places.

Mini-MACS (Eliasson et al., 2017)

- Mini-MACS classifies children's ability to handle objects that are relevant for their age and development, as well as their need for support and assistance in such situations

- For ages 1-4 years

- Also free online https://www.macs.nu/

The Mini-MACS is for younger kids based on their skill levels.

MACS & Mini-MACS - General

Figure 3. MACS & Mini-MACS - General.

The least impaired are in level one and can handle most things easily and successfully. A child in level two can handle most objects, but they do so with reduced quality, slow, awkward movements, and frequent dropping. In level three, most objects are handled with difficulty and need setup or modification. Level four is characterized by handling a limited selection of easily manipulated objects and help. Level five is primarily dependent for handling objects.

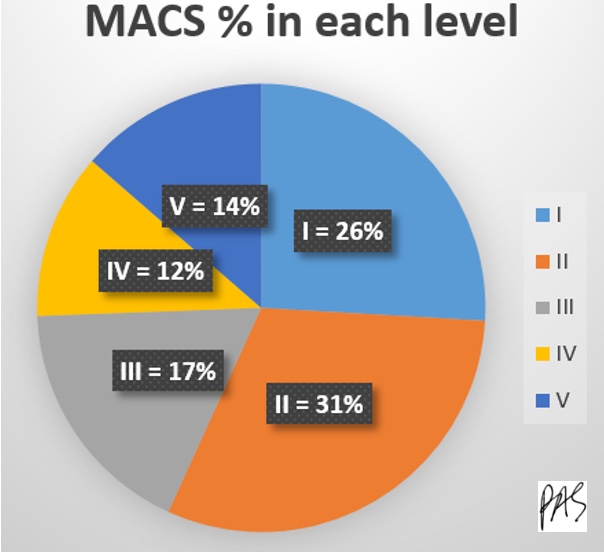

CP Population by MACS

- Complied from:

- Ohrvall, 2010, Sweden

- Hidecker, 2012, US

- Mcallister, 2022, Sweden

Figure 4. MACS % in each level.

Most kids are in levels one, two, or three, with less in the more severe categories.

Intervention

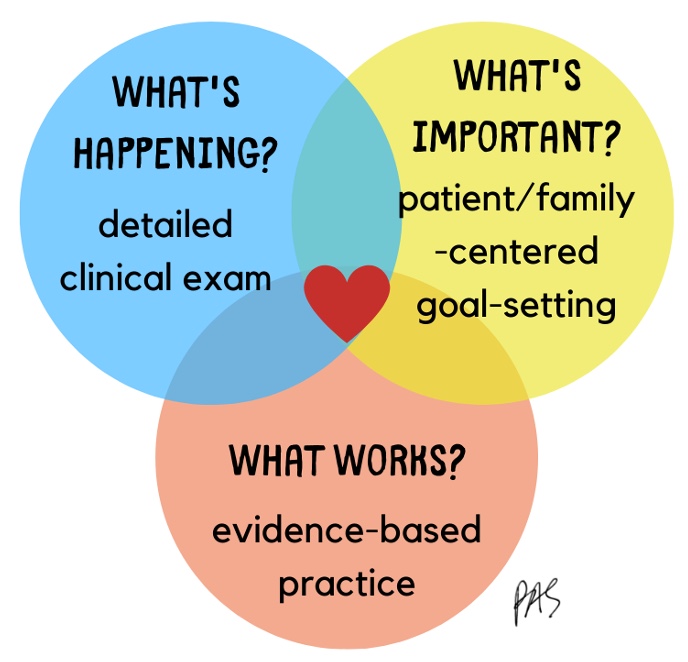

Let's shift into what we want to talk about today: intervention. Here is an infographic on our areas of intervention in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Infographic of intervention.

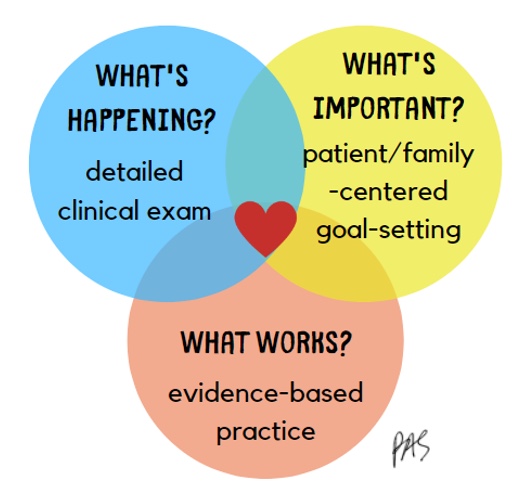

I want to give you detailed information for your toolbox and make you comfortable treating this population. While it is essential for communication to know their level, we must take a step back and realize that we have the tools to help these kids. It is similar to any intervention planning we do.

For kids with CP, we need to know what is happening right now, which comes from a detailed clinical examination. We must figure out what is essential to the child and their family right now; these priorities will change significantly over time. For example, early on, they may be focused on recovering motion or getting as much motion as possible. Over time, they may shift into not caring how they do something but only being able to do it. This may flip-flop as they figure out what works.

We also want to look at the evidence. We can do many things, and not all work as well as others. With CP, we have valuable data showing what works and does not.

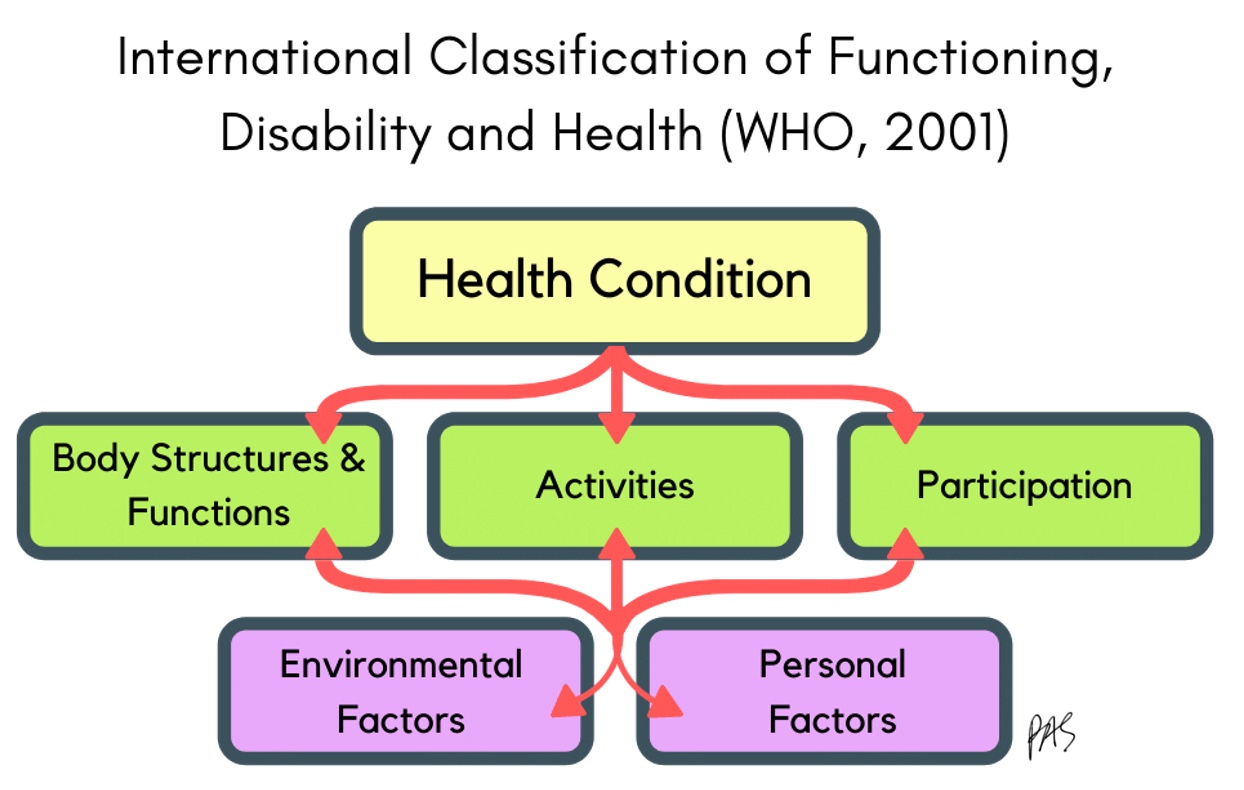

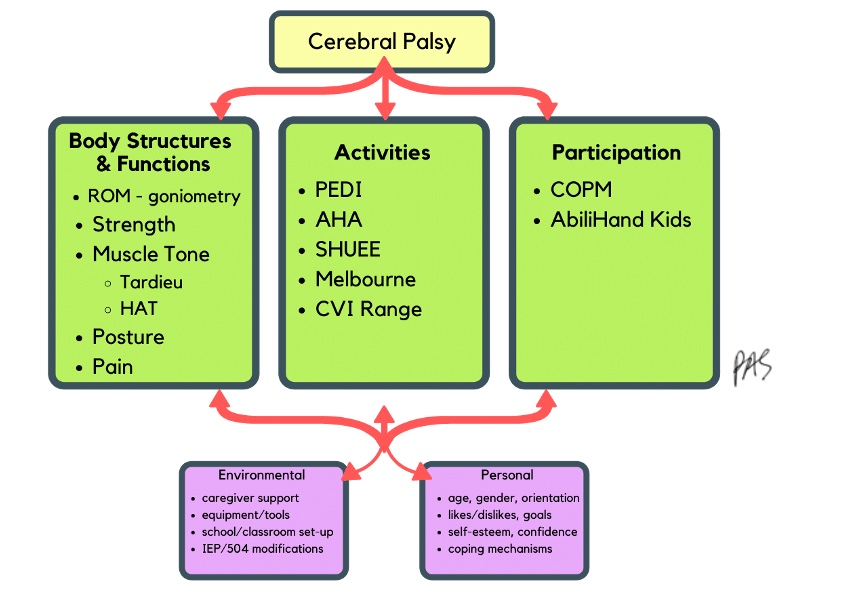

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO, 2001)

I like the excellent way to break things down using the ICF model, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. It was written by the World Health Organization in 1980 and then revised in 2001. Figure 6 shows how I like to break down thinking about intervention for any patient.

Figure 6. ICF Model (WHO, 2001).

Any health condition will impact a person in these three main areas. Body functions and structures include muscles, bones, and things we can measure, like strength and range of motion. Activities are things that a person can or cannot do, like writing, brushing hair, and eating. Participation is how a person can function at home, in school, and in leisure activities. Included in this model are environmental and personal factors. We need to know accessibility, equipment, and available resources for the environment. Personal factors include confidence level, age, culture, and family. These are the main areas where a condition impacts our roles.

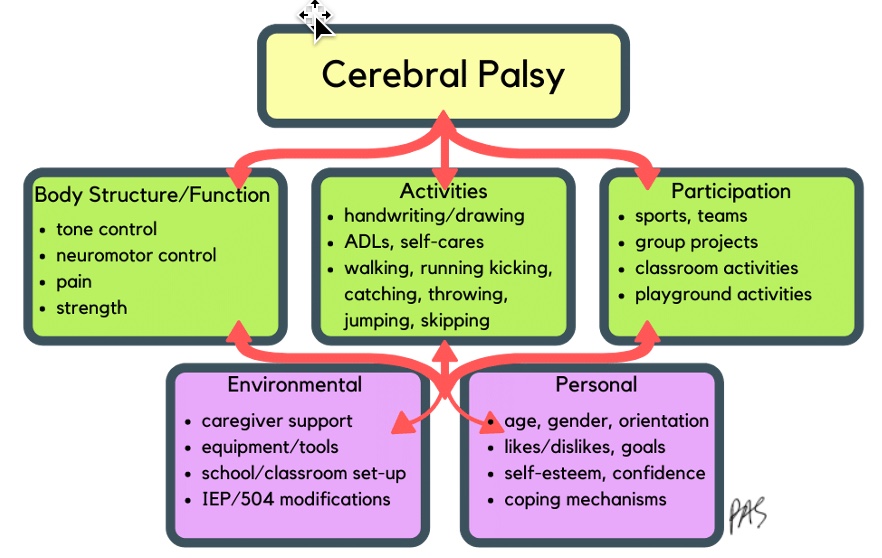

Figure 7. ICF Model using CP areas.

For CP, the body structure and function area would include poor tone control, neuromotor control, pain, strength, range of motion, and bone density deficits. There are a variety of things that are impacted that we can measure. Activities like handwriting, ADLs, working, et cetera could be affected. Participation is doing all of the things that their peers and siblings are doing in leisure, school, and home environments.

What is most important? The answer is all of it. Whenever I have students or interns, I remind them that we are not impairment reduction therapists. We aim for improved activity performance and participation. We want our kids to feel good about themselves and do the things they want to do. We can improve body functions and structures, but we must ask ourselves, "Is this activity purposeful and meaningful for the child?". Figure 8 shows another way to break these areas down.

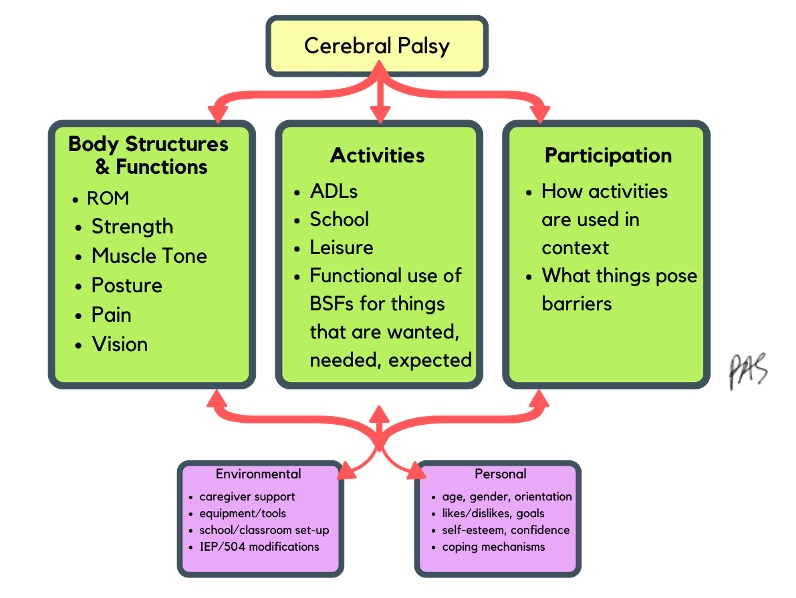

Figure 8. ICF Model further expands on CP areas.

These are the ways that we can assess these areas, and our job is to ask what things pose barriers. Figure 9 shows a list of assessments and tools in each area.

Figure 9. List of assessments and tools in each area.

These are in the references as well.

Principles of Treatment

- CP is a chronic condition that extends across the lifespan but does not necessarily mandate continuous skilled care.

- Episodes of care will occur throughout a child's lifetime and should be related to classification level (MACS or GMFCS) and age.

- Injury is not progressive, but the body will change over time with growth and age and the impact of the CP.

There are a couple of principles of treatment that are unique to CP. It is a chronic condition that is not necessarily going away and will continue throughout their lifetime. We are not trying to cure it, and the children do not need ongoing continuous care. The old model is where we used to see kids forever. We found that it did not work if we kept seeing these kids, as they do not need ongoing, continuous, skilled care. What is shown to be more effective are episodes of care.

They will focus hard on OT and then take a break and focus on gross motor skills and PT. It is going to fluctuate, and every child is different. We cannot say a child at a certain level will need more OT than others. We must look at what is happening with the family and the child; it will change throughout life. I let my families know that this is my role in their future. I tell them that I want to help them throughout their life, but that does not mean I will see them weekly for the rest of their lives. Often, we make the child and family feel comfortable, and when we take a break, they may feel anxious. We have found that it is more effective when we do bursts of therapy, 12 weeks, 16 weeks, six months, et cetera. We are working on specific goals each time and then having them put that to use in their lives. With this model, we have found that people show up more and are more accountable for their home programming. And they come up with better goals because they know the time is relatively limited. It has been empowering for everyone.

We also need to remember the injury itself is not progressive. The brain damage is not progressive, but the body will change over time with growth, age, and the impact of CP. Their body will fluctuate based on what the child is doing, so their symptoms can look progressive.

We need to monitor and work with them throughout their life.

Coordinated Multidisciplinary Care

- Pediatric rehabilitation

- Neurology

- High risk/neonatology

- Neurosurgery

- Orthopedics

- Gastrointestinal

- Developmental pediatrics

- Occupational Therapy

- Physical Therapy

- Speech Therapy

- Nutrition

- Social work

These kids are more complex than I knew a couple of years ago. They have a lot of unique differences that I would not think would be related, but they are. We have a big hospital where we know what to look for in kids with CP, but people reach out to me from smaller towns as they do not have this information. Knowing what is happening and what other specialties can contribute is essential.

Pediatric rehab is generally the hub for seeing these kids, and tone and contractures are the focus of physicians and others. Neurology looks at seizures, which are common in kids with CP. If the kids are born early, they will be followed by some high-risk groups like neonatology. Neurosurgery will be involved in more complex surgeries to decrease spasticity and other complications. Orthopedics work on surgeries to improve their joints. Many kids' gastrointestinal systems are impacted. They have terrible digestion as increased tone affects intestines and motility. Developmental pediatrics focuses on checkups and specific milestones. Of course, OT, PT, and speech will see these kids most often. Nutrition is essential as well. These kids are hypermetabolic, and they absorb nutrients differently. Lastly, social workers help coordinate many of these services, including funding and transportation.

Lifespan Approach

- Children with CP will participate in several different models of treatment and frequencies of therapy throughout their lifespan based on evidence, family-centered goals, and shared decision-making (Palisano et al., 2012; Wiart et al., 2010)

They will need things forever, but that does not mean ongoing weekly therapy. We want to work in bursts, take breaks, and come back when they want to work on something else. I have seen some families that I thought would never take a break. They want to be in therapy forever, and I understand, but these kids do not need therapy forever. I have seen many families take a break and then return to OT to do something like style hair. It gives us something tangible and functional to work on versus making it all better. It is empowering, useful, and effective when working on important things.

There are a variety of things we can do in terms of therapy, but we want to ensure we are aiming for the proper treatment at the right frequency. Sometimes, therapy is intensive a couple of times a week, while sometimes, it is monthly. We may say, "Come back and see me in a year." We must continually assess if we are seeing the person for the right amount of time. There is no solid answer, and you are not going to find an answer. We can use our experience with children at various levels in different ages and stages of life to make a judgment. For example, we may see them as they transition, like entering school. We may want to address fine motor skills or self-feeding at this time.

Primary Goals of Intervention

- Prevent & reduce secondary impairments

- Muscle atrophy, contractures, joint deformities

- Cascade of problems that follow

- Promote function, independence, & participation

- How can we help this child do what they need to do, want to do, or are expected to do?

Our primary goals of intervening for kids with CP fall into two categories. One is to prevent and reduce secondary impairments. This is important, but I do not want you to get stuck here focused on every little component of the body. We do not want to let muscles atrophy or contract, for example. In the other category, we promote function, independence, and participation as OTs. How can we help a child do what they need to do, want to do, or are expected to do? I know this seems obvious, but the following slides have so much detailed information you can get stuck in the weeds. I want to remind you to back up and assess what is happening and what is important to them right now. We then need to know if we have the tools to address these areas.

Not Goals of CP Intervention

- To reverse brain damage

- To normalize spasticity or tone

- To "cure" the CP

What are not the goals of CP intervention? One is to reverse brain damage. I would love to do that, but I cannot. The second is to normalize spasticity or tone. If I had one magic wand, I think that would be it. I want to fix tone and make it go away. Older schools of thought proposed that we could normalize or break up the tone, but we cannot. We will talk about that.

Planning Intervention

Our goal is not to cure CP. Our goal is to get these kids to do what they need, want to, or are expected to do.

Figure 10. Infographic of intervention.

Let's break this down a bit. We examined the patient, determined what was going on, and identified what was important to the child and their family. Now, we are going to turn to the evidence.

What Do Parents Think?

- Parent-identified themes when considering meaningful OT/PT Goals (Wiart et al., 2010)

- Make my child "normal," "fix" the CP- NO!

- Gain movement for function

- Fitness and physical health

- Doing things that are personally fulfilling

- "We can't do it all!"

- Roles in goal-setting should shift over time.

- Make my child "normal," "fix" the CP- NO!

This is a great qualitative study from a while ago. It looked at parents of kids with CP, providing great information about planning OT or PT intervention or goals for children. What was not on that list was to "make my child normal" or "fix the CP." I am always afraid of that. I do not want to be the one to say we are not going to make it go away, but as it is part of my role, I will address this with parents as needed.

What is important to these parents? They want their child to gain movement for function and want them to be healthy and physically fit. They want their kids to do things that are personally fulfilling. In this study, a prominent theme was that we (therapy) could not do it all. I love that because it seems like sometimes families come to treatment and want their children to participate in all available interventions. At some point, I want them to get to where they know it is essential to attend therapy when needed and for specific purposes.

The last theme is that roles and goal setting should shift over time. To do this, we must know who the client is, what is going on, and what symptoms they have because not every kid with CP is every kid with CP. What are we trying to make happen? For instance, I may look at the literature and say constraint-induced movement therapy is excellent for CP, but is it the right intervention for what am I trying to get to happen?

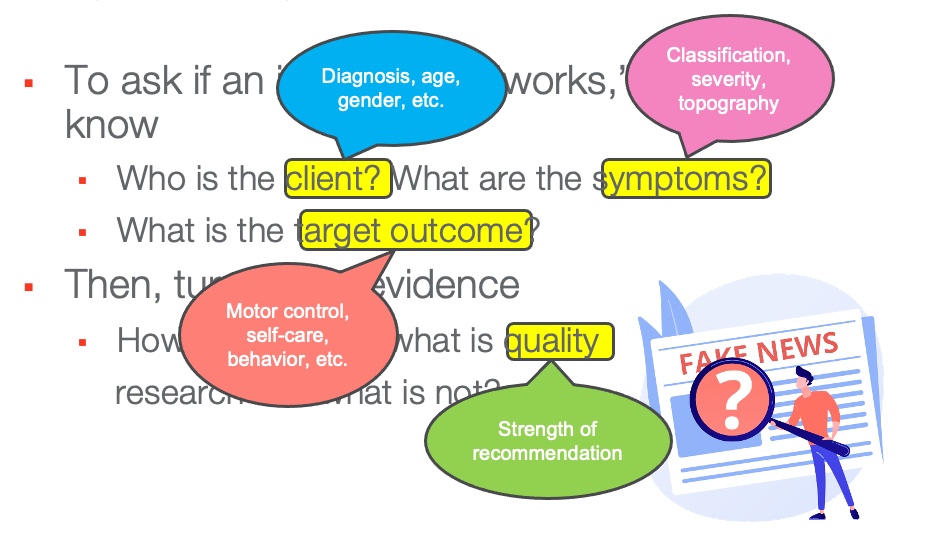

Evidence-Based Practice

- To ask if an intervention "works," we have to know

- Who is the client? What are the symptoms?

- What is the target outcome?

- Then, turn to the evidence.

- How do we know what is quality research and what is not?

There are many ways that the evidence can be broken down. It can be broken down by the client's diagnosis, age, gender, and other demographics. What are their symptoms?

Organizing the Evidence

Figure 11. Infographic of how to organize the evidence.

We need to know the target outcome. Are we looking for improved motor control, self-care, cognitive skills, or behavior? We also want quality interventions, so want to use those with strong recommendations?

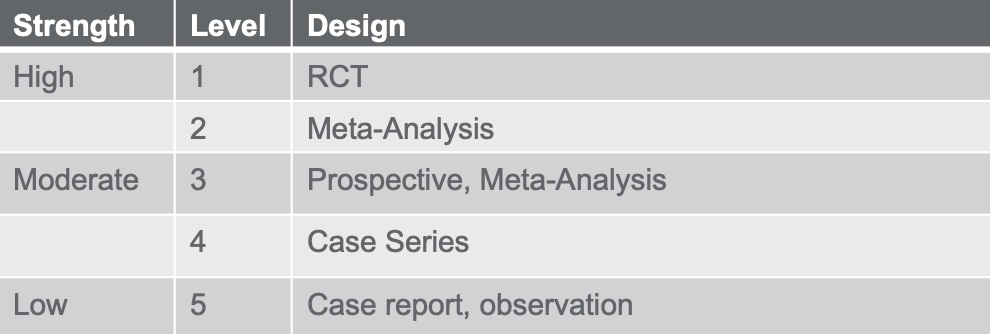

Determining Evidence Strength

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (2009)

How do we determine the strength of the evidence?

Figure 12. Levels of evidence.

Evidence Alert Traffic Light Grading System

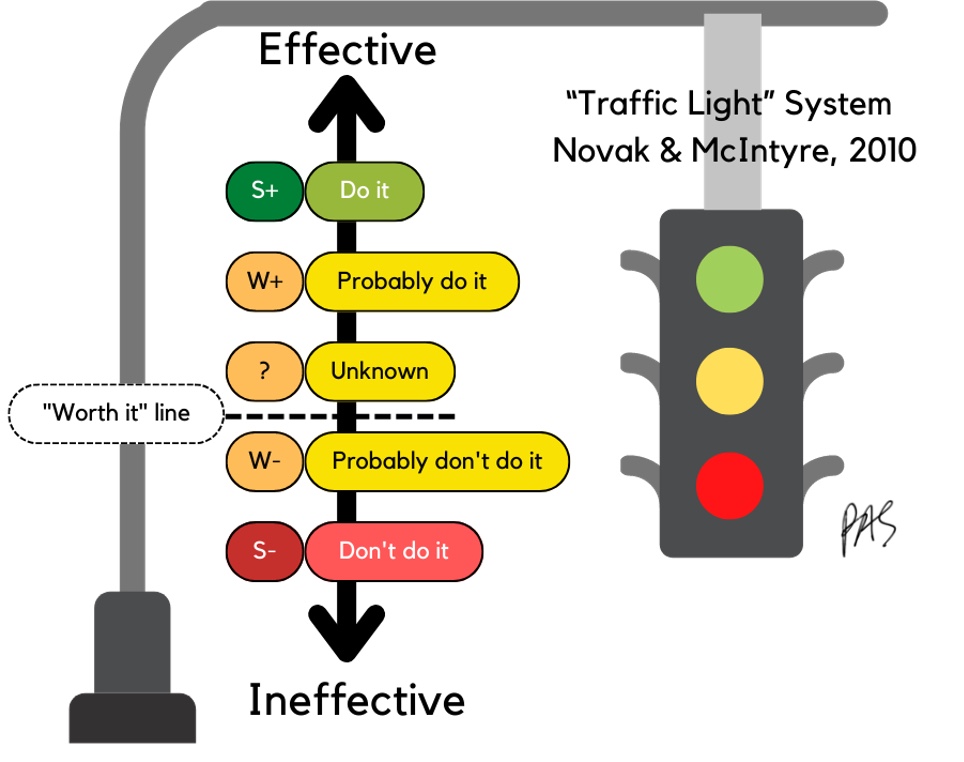

If you are unfamiliar with the Evidence Alert Traffic Light Grading System for therapy research, you should check it out. Here is an example in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Infographic of an overview of the Evidence Alert Traffic Light Grading System.

I talk about this classification system in every one of my presentations. Iona Novak, a PT out of Australia, is a brilliant, client-centered, and function-based clinician. She and her team completed a systematic review of pediatric interventions and classified them as red, green, and yellow light interventions, which are user-friendly. Figure 14 is my conceptualization of how she does this.

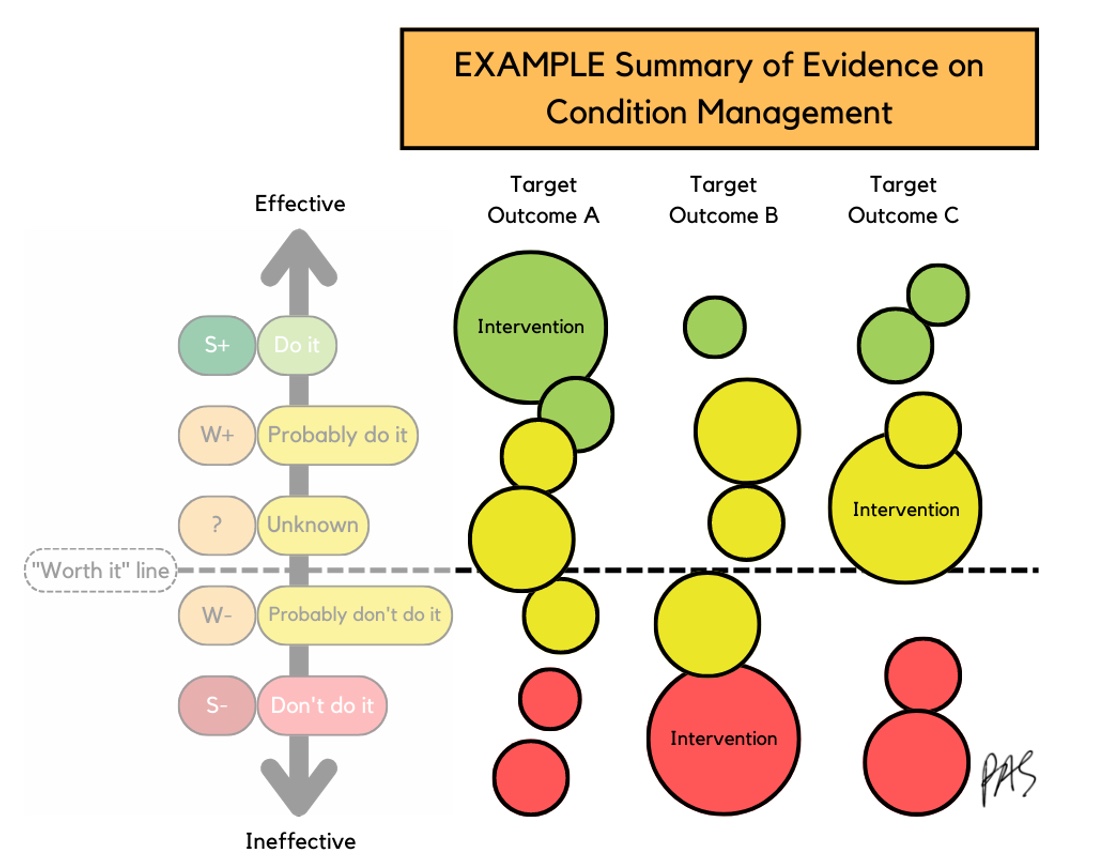

Figure 14. Infographic of how the interventions are rated.

Novak and her team gathered evidence on specific conditions, like Cerebral Palsy, and broke those down into target outcomes like motor, oral motor control, or ADL improvement. Each bubble represents a study, and the bubble size is the effect size. A larger bubble means a larger effect size. If a study is more effective, it is higher on the scale toward the green and lower toward the red if it has stronger negative intervention effects. The red interventions mean the kid got worse, not better, or even harmed. If something is above the "worth it" line, keep doing it and gather information. If an intervention is below the worth it line, there is more negative information than positive, and we should most likely stop doing it.

Traffic Light for CP

- Novak, I., Morgan, C., Fahey, M., Finch-Edmondson, M., Galea, C., Hines, A., & Badawi, N. (2020). State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: Systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Current neurology and neuroscience reports, 20(2), 1-21.

- 247 articles, 182 interventions, 383 target outcomes

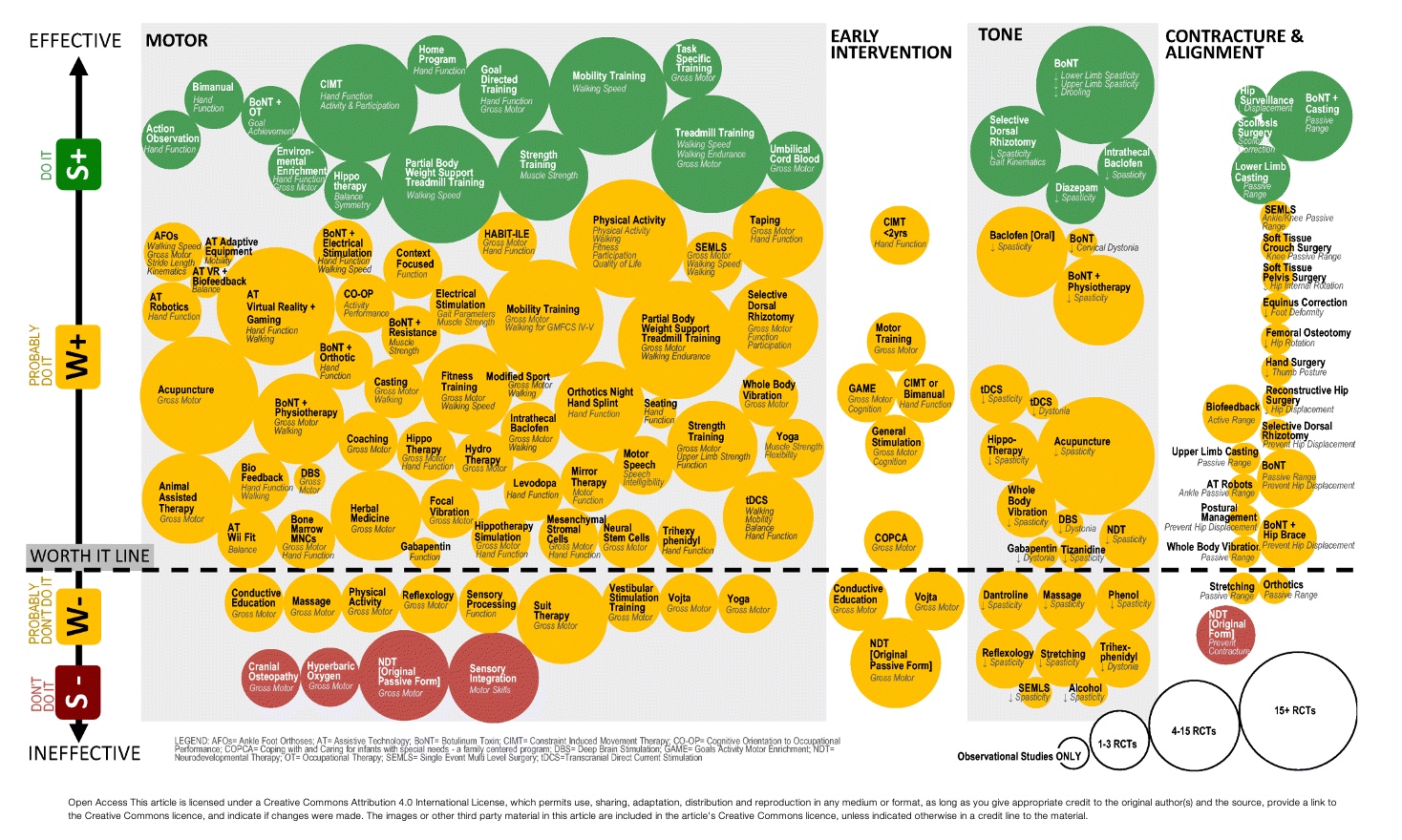

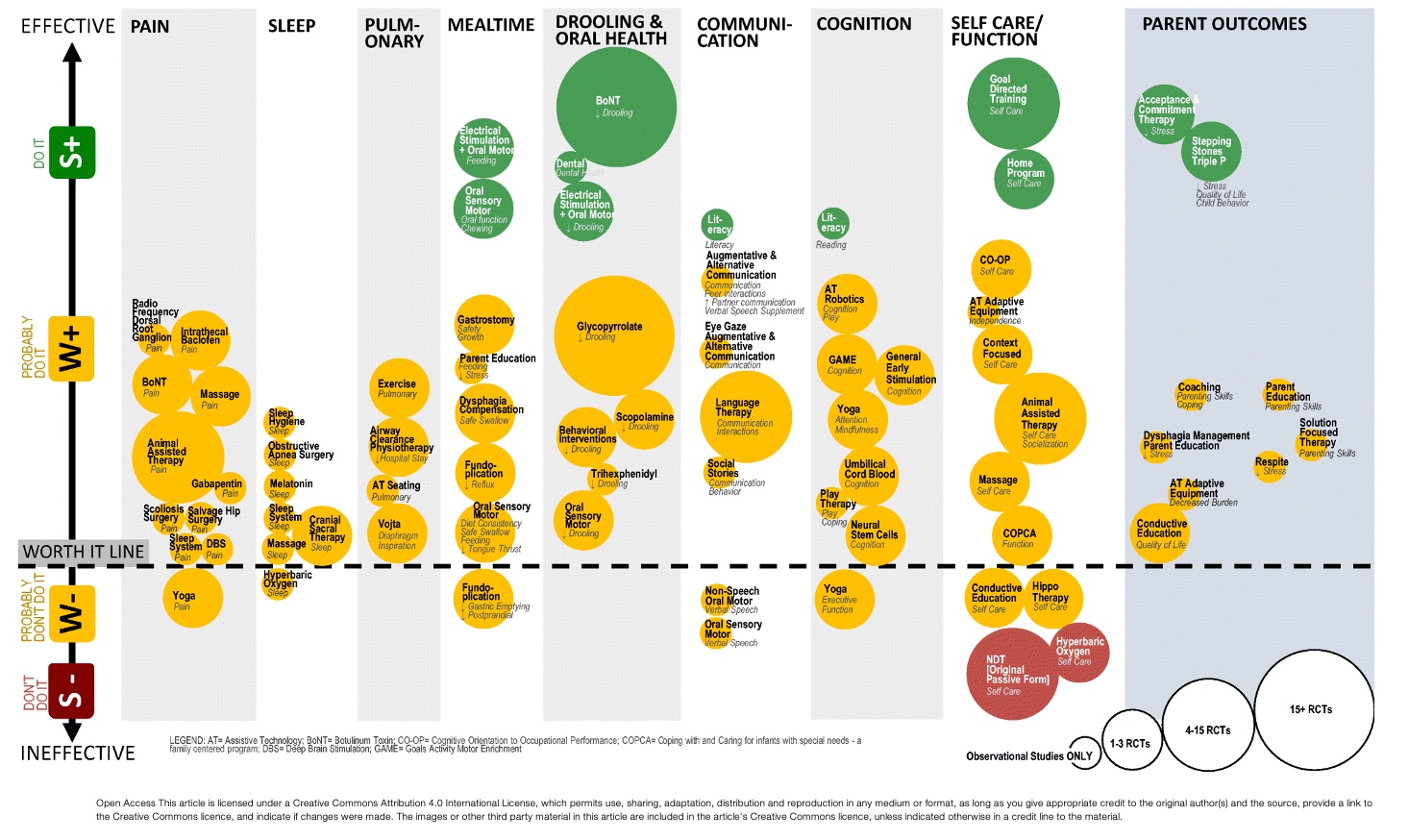

- We will discuss interventions targeting functional movement, tone control, and contracture management

- Originally written in 2013, updated in 2019

This is Novak's article that came out in 2019, which looked at all pediatric OT interventions for every condition. Recently, she came out with an update on one for CP. They looked at thousands of articles and included ones that qualified enough to be in the study. Study qualifications were that they looked at CP, had some controls, and were weighty enough to be included. This process led to 247 articles about 182 interventions, leading to 383 target outcomes. I highly recommend looking it up, but we will discuss some specific functional outcomes today.

Figure 15 is the diagram from her article.

Figure 15. Graphic from Novak et al., 2019. Click here to enlarge this image.

The more effective an intervention is, the higher up in the green area. And the bigger the bubble size, the higher the effect size. This means that the larger percentage of the study group was positively impacted. In the first gray square, these are all the studies looking for an improvement in motor function. There are a good amount of green light interventions, which is great, and many things we can do to make a difference. There are also a considerable amount of yellow light interventions. The few red light interventions mean there is evidence to stop doing them.

Figure 16. Another graphic from the article (Novak et al., 2019). Click here to enlarge this image.

It is mind-blowing how they processed all this information, but it is user-friendly. For example, I did not know that Botox had that big of an impact on decreasing drooling.

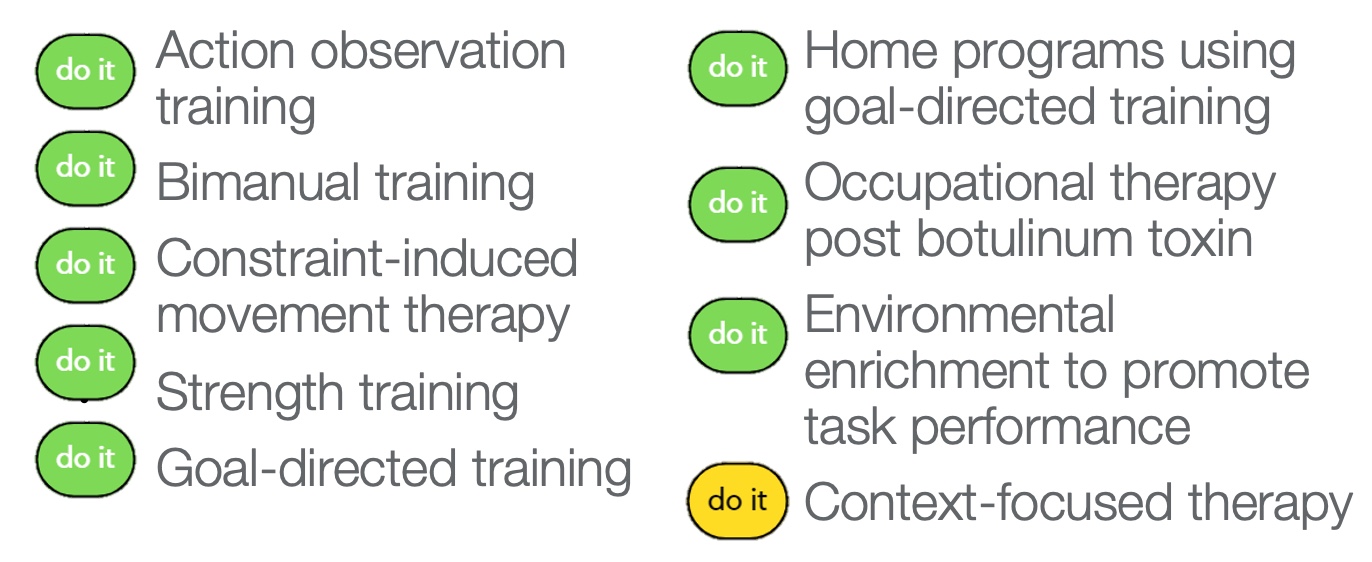

Green Light Interventions

Motor Outcomes & Function-Clear Evidence Supporting Training-based Interventions

Figure 17. Training-based interventions for motor outcomes and function.

Here are some green light and one strong yellow light interventions for motor outcomes and function. These may seem less fancy than some therapy interventions, and anyone can do these, but that is not true. However, it takes a therapist to determine their barriers and how best to help them.

Motor Outcomes & Function-Key Features of Green-Light Interventions

- Practice of real-life tasks and activities

- Self-generated active movements

- High intensity

- Practice directly targets the achievement of a goal set by the child

- Mechanism of action is experience-dependent plasticity

- Inherently rewarding, facilitating spontaneous regular practice

All green light interventions involve self-generated active movements, where the kid independently moves their own body. This is not the therapist putting them through movements or patterns. These interventions are high intensity, meaning the child works hard. This does not necessarily mean frequency. The practice directly targets the achievement of a goal set by the child.

The mechanism of action is experience-dependent plasticity. The thinking is that they cannot do things is not from the CP, but rather, they have not practiced in a way that works for them. And all these things work on the premise that these things are inherently rewarding. Doing stuff you feel good about is rewarding and facilitates spontaneous regular practice.

Action Observation Training

- Clients watch video clips of functional movement sequences without verbal instruction and without simultaneous rehearsal.

- Immediately after watching, clients are prompted to rehearse the movements.

- Believed to activate mirror neurons and portions of the brain involved in motor learning and motor planning.

(Buccino et al., 2012)

Action observation training is an intervention where clients watch video clips of functional movement sequences without verbal instruction or rehearsal. The therapist or the researcher will record a video of something like opening up a soda can. It is the video of that action without any verbal cueing. The child watches that video without any instruction, and they do not practice at the same time. Immediately after watching, the client is prompted to try it on their own without verbal cueing. It is hoped that the child forms a plan or a concept of what to do. The theory is that action observation training activates mirror neurons and portions of the brain involved in motor learning and planning. We know that it is effective at getting kids to try their own plans. It is similar to video modeling.

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT)

- CIMT is based on principles of mass practice & shaping, in which a constraint is utilized on the unaffected hand/arm of a person with hemiplegia to improve functioning of their involved upper extremity.

- Improves bilateral hand use by improving the capacity of the affected UE through neuroplasticity.

- Multiple protocols exist, varying in duration of cast use and intensity/frequency of skilled intervention.

Constraint-induced movement therapy is a significant OT intervention based on mass practice and shaping principles. It involves doing things over and over that are hard and getting better at it with a constraint on the unaffected arm or hand of a person with hemiplegia to improve the functioning of that impaired arm. We put a cast or a brace on the arm that is better to make the child figure out how to use their more impaired arm. It is shown to improve bilateral hand use by enhancing the capacity of the impaired arm.

It is shown to improve the functioning of the impaired arm, and there are different protocols depending upon location or study. They vary in duration, cast and splint material, intensity, frequency of the scaled intervention, and amount of practice. Despite the variety, they are all effective, which is interesting.

- No published age or ability cutoffs

- Clinically, it is more tolerable & successful with:

- Purposeful grasp in affected UE

- Independent hand-to-mouth with affected UE

- When the child isn't "waiting" for the cast to be removed

- All day vs. on for a few hours, then off

- Cast is not seen as punishment, and removal is not treated as a reward

There are no published age or ability cutoffs, which was frustrating. Can you do it with a baby? The answer is yes. There is no data from studies, but it is from my experience. It is more tolerable and successful for kids with purposeful grasp and release, but I have used it with those with a poor grasp. They have to have some ability to pick something up, and it is great if they can release it, but it is not as crucial as the grasp. The other thing to consider is independent hand-to-mouth motion because eating is motivating. If they can pick something up and bring it to their mouth in any way, no matter how sloppy, I get more success. These are the two things I look for before using CIMT. Some therapists would rather not use CIMT because they want the child to recognize that their hand is there.

It can be tricky at this age. If it is a short protocol with two hours on and two hours off, the child may focus on moving when the cast comes off. It works better if the cast is on during waking hours. You want to teach the family to look at the cast, not as a punishment or a reward when removed.

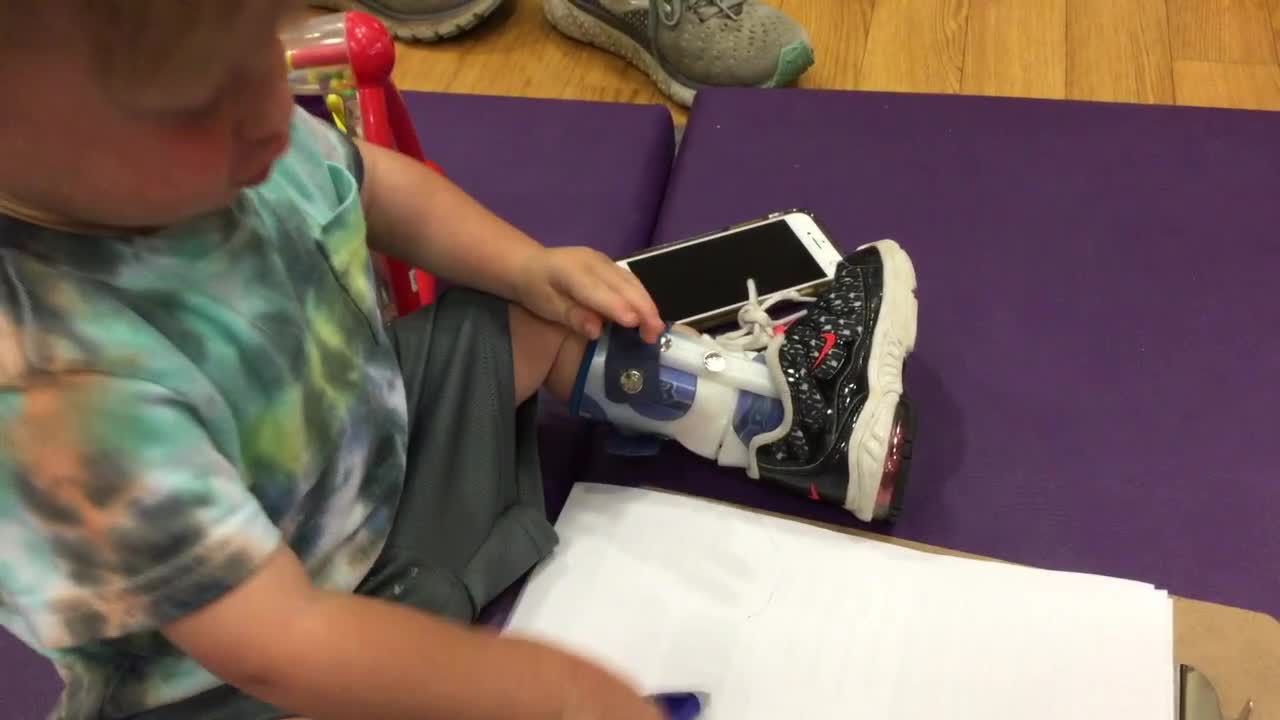

Video 1-Infant CIMT

Here is a little example of an infant doing CIMT with me.

I think this is a good result from CIMT, but knowing how to set my and the family's expectations is essential. He may not play piano, but he is willing to use it more and get things done faster with less frustration. I am not trying to get it to work better than the dominant hand, but I want them to use it with their other hand.

Bimanual Training (BIT)

- BIT intensive functional task training for patients with hemiparesis to improve performance of tasks that require two hands

- Often used in conjunction with or following CIMT to further improve bilateral function

- Hand Arm Bimanual Intensive Training (HABIT)

- Focused, intensive, structured practice of functional bimanual activities (Brandao et al., 2018)

- CIMT & BIT are often used in conjunction with Botox injections

Bimanual training is when we are intensively working on skills that require two hands. When used at our hospital, we often use it following CIMT. For example, we will do eight weeks of constraint followed by four weeks of bimanual training. If you just focus on the constraint treatment, they may learn to do things with their impaired hand but then return to their stronger arm when removed. If you follow it with bimanual training, they discover a new set of skills using both hands.

A published bimanual training is called HABIT, Hand Arm Bimanual Intensive Training. It is a nicely packaged way to look at it.

Botulinum Toxin + OT

- Botulinum toxin-A (Botox) injections are used to treat spasticity and dystonia

- reduce over-activity in targeted muscle groups

- improve movement and reduce pain

- When combined with OT, botulinum toxin has been found to improve motor activity

- Provide stretch to injected muscle, strengthen opposing muscles, engage in function

- Lasts 3-6 months

Both constraint and bimanual training are often used in conjunction with Botox, which we will discuss briefly. Botox temporarily paralyzes and weakens a muscle. It was initially used with kids with CP to treat spasticity before cosmetic purposes. Botox reduces overactivity in targeted muscles to improve movement and reduce pain. Research shows that you get good results when you time Botox with a burst of OT. Our rehab docs have gotten good at recommending Botox and OT, but this is not always the case.

We must figure out if a tight muscle is getting in the way of doing things. For example, let's say we are doing Botox to the thenar eminence because a kid is pocketing their thumb. The peak of Botox's impact is three to four weeks after the injection, so we want to start doing OT during this time. I may do a splint to stretch out that muscle, let it relax, and then strengthen the opposing muscle and engage them in functional activities. Botox only lasts three to six months and varies by the child. Sometimes all you need is that one time to stretch them, strengthen the other side, and get great function. Others may need it every three to six months.

Goal-directed Training

- Rehearsal of activity sequence in the presence of deficits using motor learning and compensatory strategies as needed

- Practice the goal activity only, NO rote strength or ROM; no generalized fine motor work

- Practice entire activity sequence with focus on one step at a time as needed

- Can use cognitive strategies (e.g., CO-OP or Motor Imagery) to enhance motor learning

Goal-directed training is focused training on doing something that the kid wants to do. It can look a lot of different ways. Goal-directed training is breaking down the goal into several levels and targeting difficult things. It is a rehearsal of any activity sequence in the presence of deficits using motor learning and compensatory strategies.

This does not mean you have to work on the whole goal of playing basketball. They can just work on picking up a basketball. We are not doing rote strengthening, range motion, or other prep activities. I love goal-directed training, which is the bulk of what I do with most of my patients.

You can also use cognitive strategies, like Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) or motor imagery. I will talk about this in a future lecture.

Video 2-What Intervention is Best?

My buddy Brayden is in this video, and we were doing some CIMT.

He is engaging his more impaired arm to an extent. He can open it, get the chip out, and eat it. He is not so sad. Not all green light interventions are effective for all kids at all times. I continuously cycle through in my head what green light intervention would work.

Strength Training

- All children with CP are at risk of muscle weakness (Novak, 2014)

- Children with CP have muscle imbalances across joints (Eek et al., 2008)

- Strength training targets slow functional movements or muscles groups using:

- Anti-gravity and gravity-assisted bodyweight training

- Resistive training using resistance bands, cuff weights, pulleys, or free weights, weight training equipment

Strength training is a green light intervention. All children with CP are at risk of muscle weakness. They seem strong, but they are not and have muscle imbalances. Strength training is supported by lots of published, intensive strengthening guides. You start with gravity-reduced movement with a sling or pulleys and then move up to resistive training.

- Indications:

- Muscle weakness is a primary factor in the child's functional limitations

- Weakness of a specific muscle group is affecting the child's movement patterns

- Example: The child has weakness in elbow extensors affecting reach

- Do it: Multiple additional benefits: fitness, physical activity, participation, quality of life

When should you use strength training? If you strengthen a muscle, will that make it more accessible for them to do what they want? I used to do a lot of strength training as part of specific protocols, but I had to ensure that the weakness was the thing making it hard.

Of course, there are benefits to getting stronger, improving posture, and being more fit to increase the quality of life.

- The following program characteristics are recommended to maximize safety:

- Instruction in proper form/alignment

- Supervision during all weight training

- Sub-maximal weights

- Proper warm-up and cool-down

- Program variation to avoid overuse injuries

(Faigenbaum et al., 2009)

There are some program recommendations; you can read about them a little later. You want to look at them using the proper form and weights, a warm-up and cool-down, and strength training safely.

- Strength training program design:

- Frequency: 2-3x/week for 8-12 weeks

- Volume: Start with 70-85% of 1 rep max

- 3 sets of 6-8 repetitions

- Rest 60-90 seconds between sets

- Increase 5% once 3 sets at 85% 1 rep max achieved

- Quality: Slow, controlled movements

- Always follow with functional skills

(Moreau et al., 2016; Moreau et al., 2013)

Some protocols can help you find the child's one rep max and bring it down from there to start. It can also give guidelines on reps to do over a certain number of weeks and when to follow that with functional skills.

Home Programs

- Child-centered, active, repetitive, and structured home-based practice of functional tasks meaningful to the child and family (Novak, 2014)

- Home programs are used within the context of all other interventions

- Developed through collaboration between therapist and family

- Should be the result of ongoing family-centered discussions, NOT prescriptive

Home programs are green light interventions. We can use them within the context of all these interventions. We want to ensure our home programs are developed with the family and the child. As such, I have changed the way I approach home programming. I used to give the family and child many things to do at home, but when I became a mom, I realized how unrealistic this was. I cannot even get my kids to practice piano. So I start with, "What do you want to work on this week?" And, "When do you think you could do it?" We need to take it out of the prescriptive form and move more toward a discussion.

Environmental Enrichment

- Children who have impaired movement & perception automatically have deprived environments as compared to unimpaired peers

- Proposes that enriched environments innately promote motor challenges & learning opportunities

- Enriched environment + brain plasticity = learning, memory, motor learning

(Morgan, Novak, & Badawi, 2013)

Environmental enrichment is a specific intervention. It sounds like making the environment nice and motivating, which is true, but it is a specific school of thought. It is based on the belief that kids who cannot move, think, or see their environment are unenriched. They do not have access to the environment as much as kids who can move and do things. If we enrich the environment for kids with CP, you pull out their cognitive, sensory, motor, and social skills to learn in their context.

Context-focused Therapy

- Concentrates on altering the factors in the child's tasks and surroundings instead of treating the child's impairments

- Change the task

- Change the environment

- Provide adaptive equipment

Context-focused therapy is a yellow light I included in this section because this is something that I like to keep in mind all the time. Context-focused therapy is where we are taking the intervention off of the child. I am not trying to change the child's body, but I can change anything else. I can make the task easier, use different equipment, change the environment, give visuals, et cetera.

- Adaptive equipment

- Self-Care Tools

- reachers, cuffs, dressing aids

- Durable Medical Equipment (DME)

- bath seats, transfer benches, commodes

- https://www.yourcpf.org/all-products/

Adaptive equipment is increasingly available. This link is from the Cerebral Palsy Foundation, where they have many different products for this population.

- Seating/Standing/Positioning Options

- Being upright is essential for health

- HEALTH: Bone density, respiration, digestion, muscle activation, ROM

- FUNCTION: Use of vision, use of extremities

- PARTICIPATION: The rest of the world is upright!

- Being upright is essential for health

Context-focused therapy is done where the child is spending most of their time. It looks at where they are sitting, standing, and positioned. We want to get these kids upright for various periods, so they can use their vision and hands to participate with their peers. Seating is often done by somebody in a specialty clinic or DME department.

- Ensure support is comfortable and adequate

- Encourage participation when in stander or seating devices

- Provide trays/tabletops

The child needs to be supported and comfortable. Does the position allow them to do more, and do they have a surface to do things on? These were the green light interventions. Now we are going to review yellow light interventions.

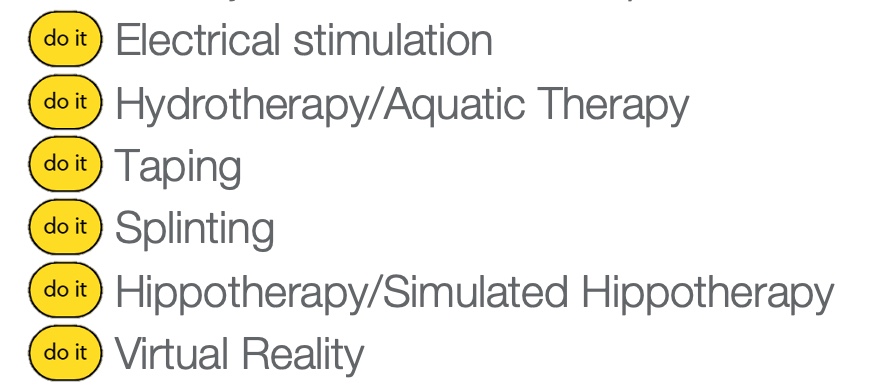

Yellow Light Interventions

Motor Outcomes & Function-Augmentations Yield Positive Effects

When added to task-specific motor training, these adjunct interventions improve results (Figure 18), but none of these are proven effective in isolation.

Figure 18. Yellow light interventions.

These are supported interventions when we add them to task-based training. These things are not shown to be effective on their own, but they will when we add them on top of working on the hard stuff. These include electrical stimulation to specific muscle groups, hydrotherapy or aquatic therapy, therapeutic taping, splinting, hippotherapy with horses, or simulated hippotherapy, which I have never seen but sounds cool, and virtual reality.

Splints and Orthotics

- Indications:

- Optimize function by promoting joint stability

- Thumb opponens splints

- Wrist cock-up splints

- Improve or prevent loss of range of motion

- If minimal support is needed, therapeutic taping can be used

- Optimize function by promoting joint stability

Many kids with CP have splints, but we want to ensure that we give a splint because it improves function or health. There are many different kinds of splints. I see a lot of kids with CP that have a thumb splint or a wrist cock-up splint, as seen in Figure 19.

Figure 19. Thumb and wrist cock-up splints.

If we put a joint in a specific position, will it improve what they can do? We also want to ensure that if we splint a child, we are not taking away movements that kids use, like the tonal synergies they use for function.

- Considerations:

- Hand splints meant to put the hand in a "functional" position often block tonal synergies that kids use for function

- Literature supports use of hand splints at night ("non-functional" splints) to maintain ROM and joint stability (Jackman, Novak, & Lannin, 2014)

- When children posture in joint deforming positions, orthotics are helpful to provide a prolonged stretch (6-8 hours/ day) to maintain ROM

- Literature suggests that task-based interventions focusing on problem-solving are more effective at facilitating hand function than "functional" hand splints! (Jackman et al., 2018)

What is supported in the literature is night splinting to maximize their range of motion to allow them to move during the day. Literature shows that working on a functional skill using a task-based or cognitive intervention is more effective than putting a child's hand in the correct position, which I thought was cool.

Hippotherapy

- Therapeutic use of equine movement to engage sensory, neuromotor, and cognitive systems to promote functional outcomes

- Child active: Child is riding the horse

- Child passive: Child is being led

- For non-ambulatory children, hippotherapy promotes postural control & balance for supported sitting (Novak, 2014)

Hippotherapy uses horses, and there are a couple of different kinds:

- The horse's center of gravity is displaced three-dimensionally when walking (similar to that of the human pelvis during walking)

- The horse provides a variety of inputs to the rider, which may be used to facilitate improved contraction, joint stability, weight shift, and postural equilibrium responses

- Facilitates participation & engagement

The child's pelvis is on the horse, and as the horse walks, it moves that child's pelvis the same way as if the child is walking. This movement provides a ton of input, and what I love about hippotherapy is that it facilitates participation, engagement, and social skills. Just engaging with the horse and being out in the community is impactful.

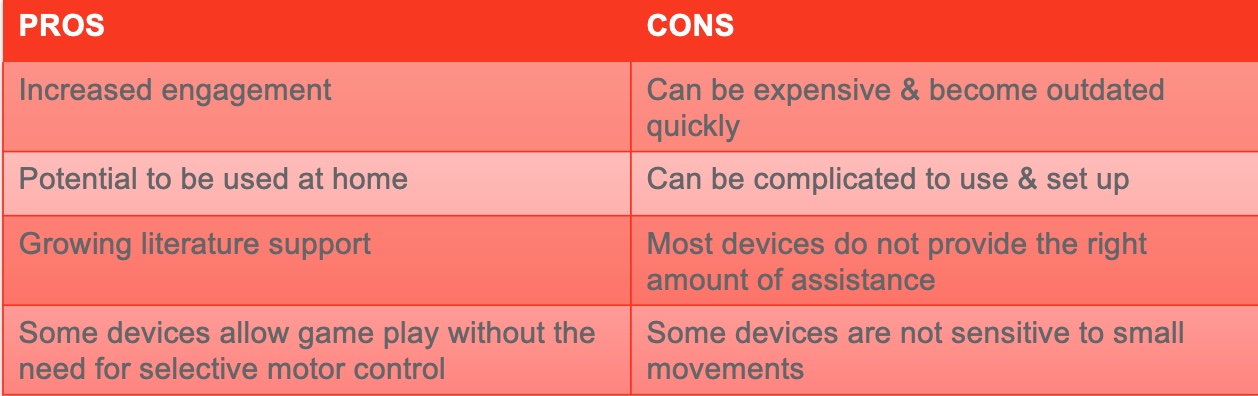

Virtual Reality

- The use of software to enable high dose repetitive child active structured training in motor function (Novak, 2014)

- Multiple brands & options, constantly evolving

There are so many different types of virtual reality. The pros and cons are seen in the chart in Figure 20.

Figure 20. Pros and cons of virtual reality.

Kids like it, and it increases engagement. The cons are that it is expensive and can be outdated quickly. It can also be complicated. If you have virtual reality accessible to you, try it.

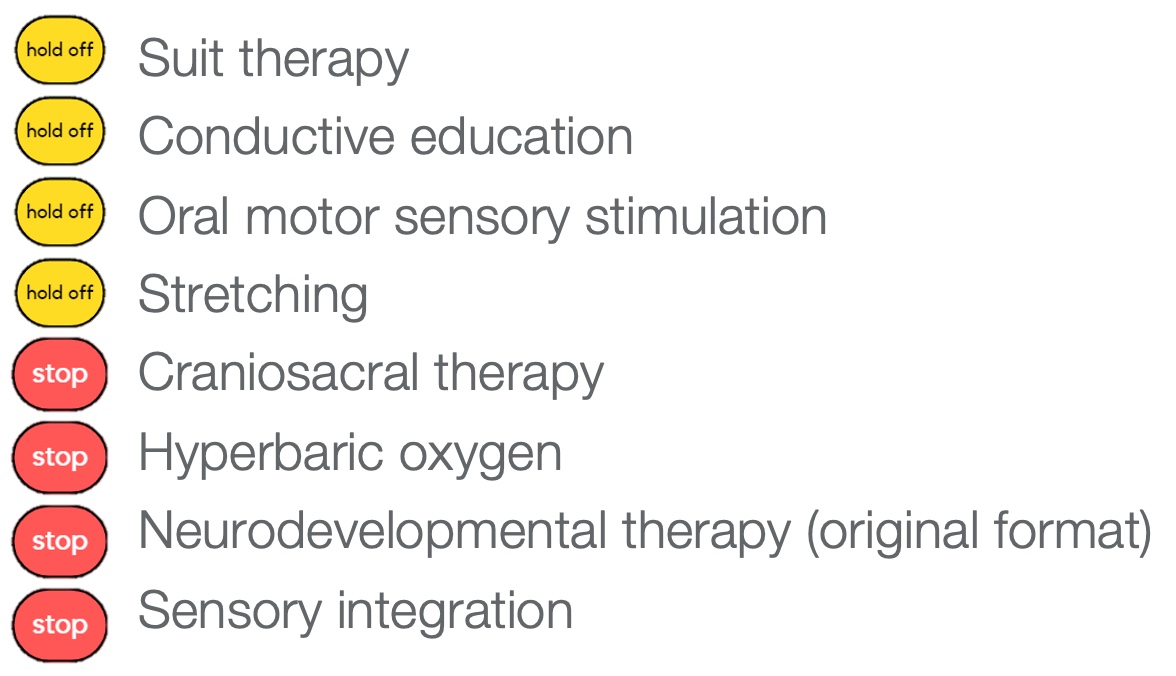

Yellow and Red Interventions- Hold Off

Most Outcomes & Function- Generic, Bottom-up, Passive Interventions Are Not Effective

What is shown to be not effective are generic, bottom-up passive interventions (Figure 21).

Figure 21. Generic bottom-up passive interventions.

With passive movement, the children are not thinking about how they move. Suit therapy includes Velcro garments with bungees that move the body into the proper position but is ineffective. Conductive education is a form of therapy that is focused on a specific type of learning. Oral motor sensory stimulation is obvious, and stretching does not do anything and is just uncomfortable. Craniosacral therapy, hyperbaric oxygen. NDT, in its original format, are not effective. Sensory integration for kids with CP is not effective either.

Tone Management- Occupational Therapy/Allied Health

- Unfortunately, there are no effective tools for OTs to change abnormal muscle tone.

Unfortunately, we do not have anything in our OT toolbox that changes tone. What we want to do is work with the tone and see how we can make use of it or minimize its impact.

- Tone varies throughout a child's day.

- Severity at any given moment is dependent on state of arousal and time from any inciting event.

- Abnormal tone can impact functions differently.

- Impede function – co-contraction of biceps & triceps often interferes with reaching, whole body extensor patterns can interfere with sitting & crawling

- Facilitate function – recruitment and use of tone can often allow standing and stepping, which wouldn't be possible using the child's weak muscles

Tone varies throughout a child's day. Families may say, "They are relaxed when they sleep." Tone is sparked when an individual tries to do something or when they get excited or scared.

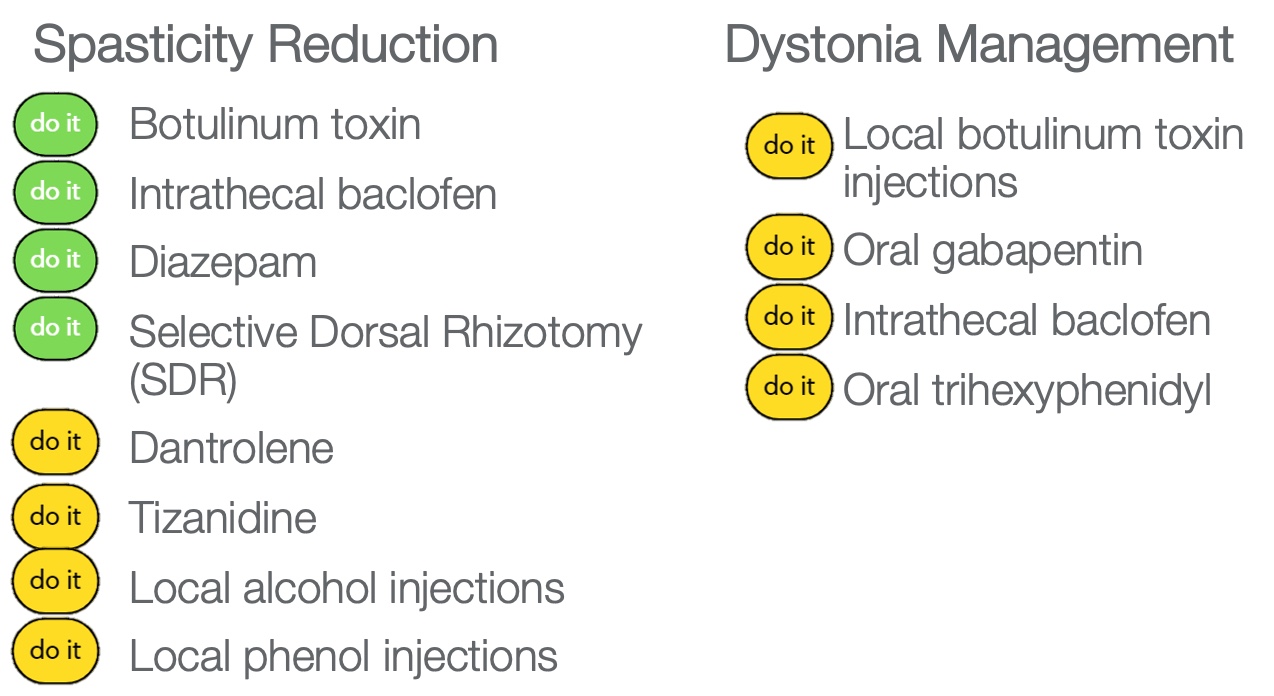

Tone Management- Pharmacology & Neurosurgery

What works for tone is medication and surgery. Some examples are in Figure 22.

Figure 22. Pharmacology and neurosurgery options for tone.

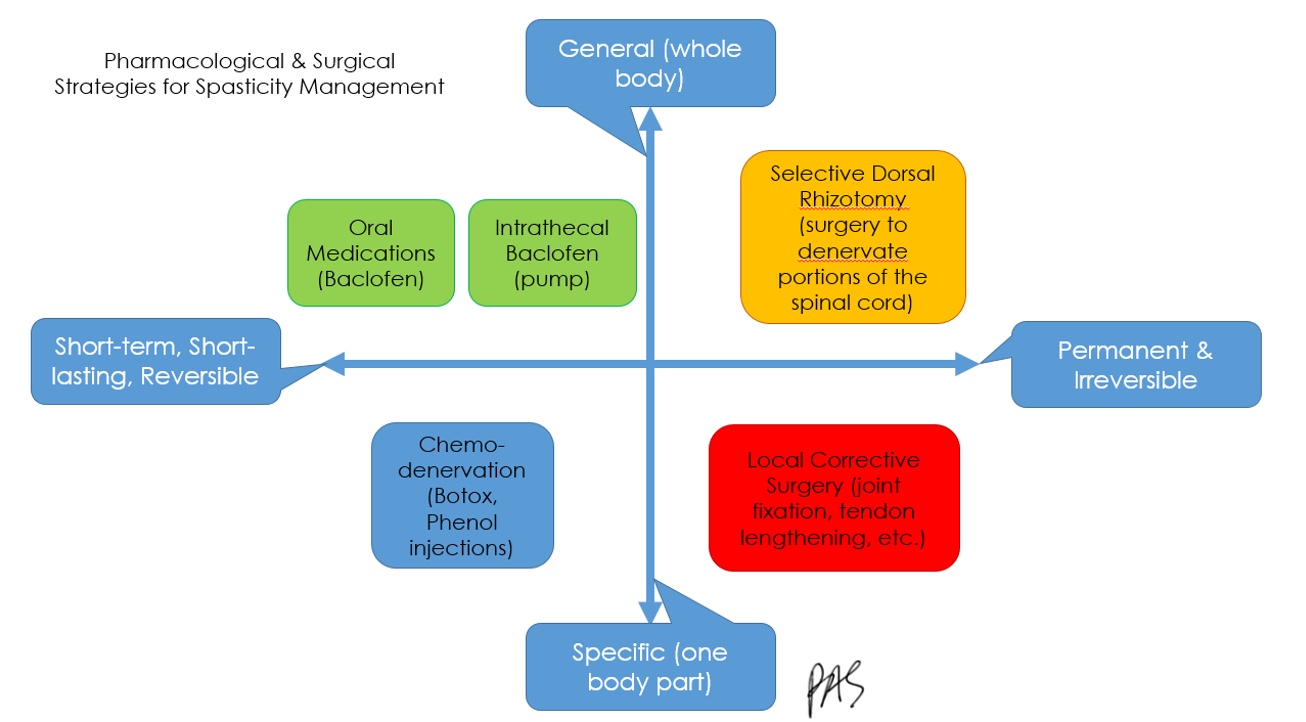

To reduce spasticity, there are some medications like Botox, intrathecal baclofen, a medicine that is in a pump and goes into the muscles directly, and Diazepam. Selective dorsal rhizotomy is a surgery I will talk about in a minute. There are other oral and injected medications listed. Dystonia is more tricky to treat, but here are some examples that may work. This diagram in Figure 23 shows four options for drugs and surgery.

Figure 23. Graphic showing options for medications and surgery. Click here to enlarge this image.

Some of these interventions are more temporary,

- Because abnormal tone can both interfere with AND facilitate function, reduction of spasticity should be considered within the context of its functional impact and multiple factors (Patel et al., 2020).

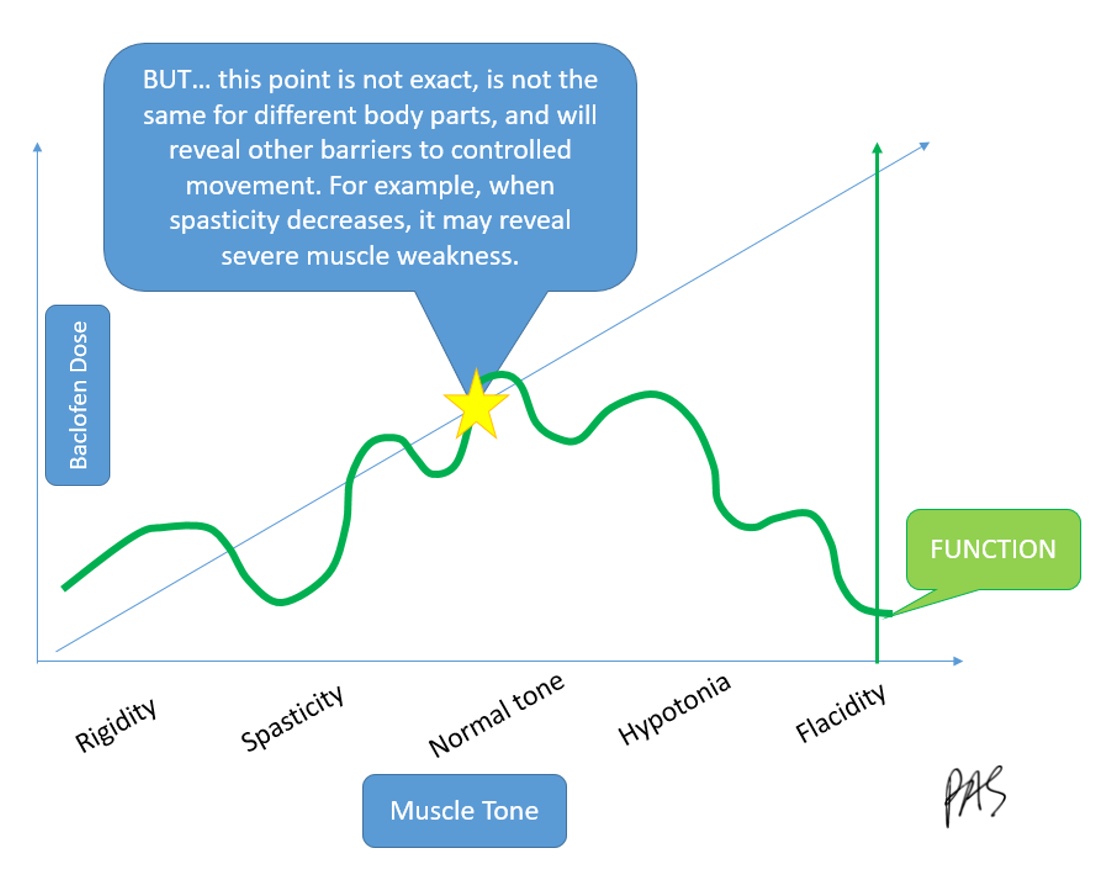

If we give somebody a medication that will reduce their tone, and the child uses their tone for movement, it will take away their function. I created this graph in Figure 24.

Figure 24. Graph of how baclofen and function have an inverse relationship. Click here to enlarge this image.

We must know the right balance of removing the tone that is impairing and uncomfortable versus leaving some tone that lets the child function. There is no exact point, and it changes over time.

Tone Management- Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy (SDR)

- Surgical technique to reduce spasticity in which dorsal (or posterior) nerves are selectively cut.

- The rhizotomy is performed through an incision in the spine, and a stimulator is used on the muscle to attempt to identify abnormal nerves; these nerves are then cut, resulting in an immediate reduction of the child's spasticity

An SDR, Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy, is a surgery used to reduce spasticity in which dorsal nerves are selectively cut. The neurosurgeon identifies the activating nerves causing the spasticity in the muscle, and they cut those. It is permanent, and the therapy programming can be upwards of an entire year.

- Indications- Children who are:

- Ambulatory 3-7 years old who are able to walk with significant difficulty due to spasticity, but are limited due to spasticity OR

- Children who are dependent for all care, and whose care is difficult and/or hygiene is a challenge because of spasticity

- Children with dystonia are not candidates for a SDR

- Intensive physical therapy (1-3x/week) is needed for the full year following the SDR in order to maximize results

- Results are generally good, but hard-earned

- The surgery is NOT reversible

Results are excellent but hard-earned. It is not reversible, and it is not for everybody.

Tone Management-Reflexes

- Persistence of primitive reflexes or primary motor pattern beyond the expected age is a key clinical characteristic of CP.

- Persistence of primitive reflexes prevents or delays typical progression of motor development and sequential acquisition of higher-level neuromotor skills.

- There is no substantial evidence supporting neurofacilitation, NDT, or reflex integration techniques to improve functional motor control.

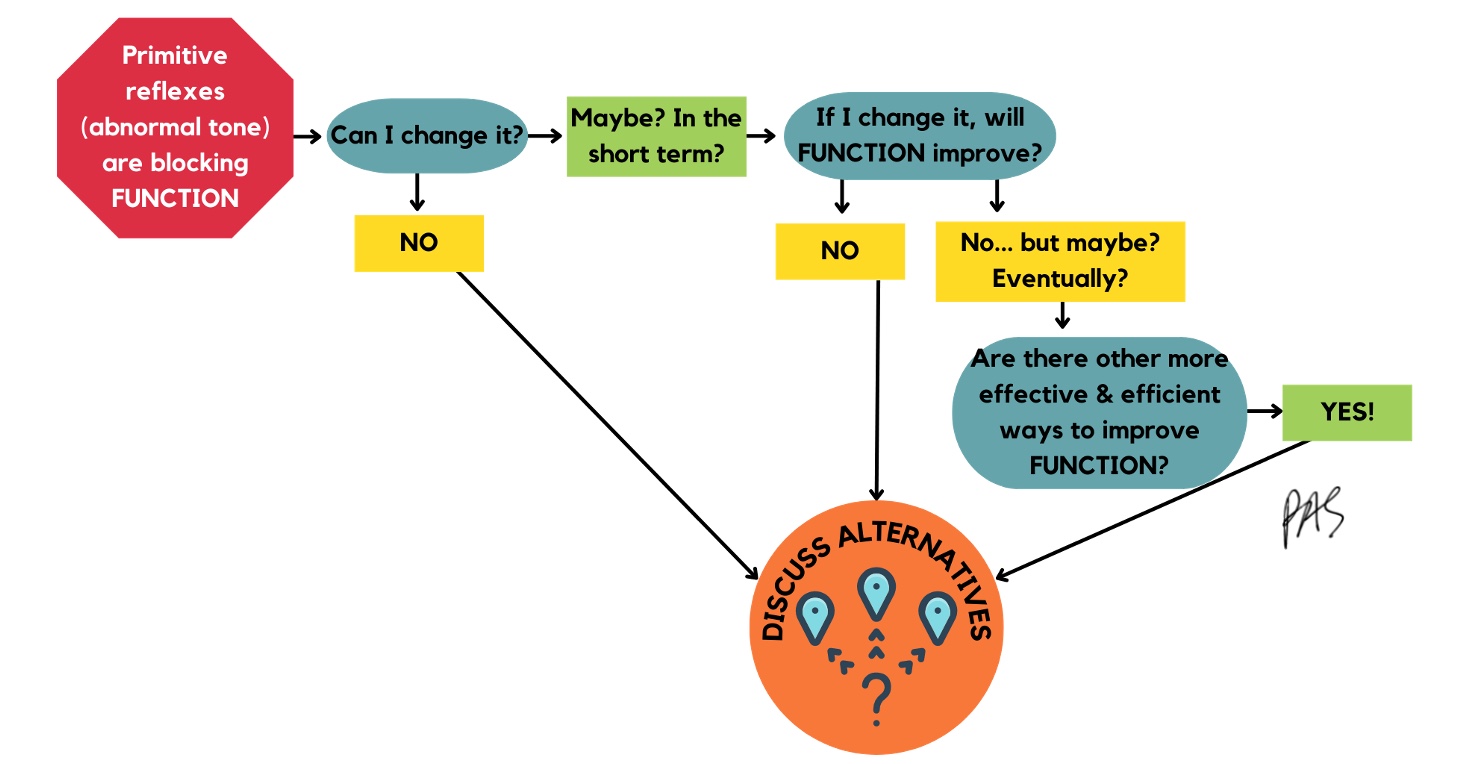

There is no substantial evidence supporting reflex integration or neurofacilitation. Figure 25 goes through a series of questions.

Figure 25. Decision tree for tone management. Click here to enlarge the image.

If primitive reflexes are blocking function, can I change that? I have not seen this, and research does not support this. Let's say, I say, well, maybe. Can I change it a little if I move them through specific patterns? Does that improve function? This does not improve function directly, which will lead me to think I should not do it. If it does not improve function now, perhaps it will. I will ask myself, are there other more effective things I can use with my time with this child? And if there are, I would do those instead.

Contracture Prevention & Management

- Upper Extremity

- Incidence: 36%

- Most common

- Thumb in palm with clasp hand (causes greatest impairment)

- Shoulder adduction & IR

- Wrist flexion & pronation

- (Makki, Duodu, & Nixon, 2014

- Lower Extremity

- Incidence: 34%

- First contractures

- GMFCS I&II – ankle plantar flexion

- GMFCS III-V – knee flexion

- (Cloodt et al., 2021)

Contractures frequently happen with these kids. We want to ensure that we are monitoring them, especially their upper extremities.

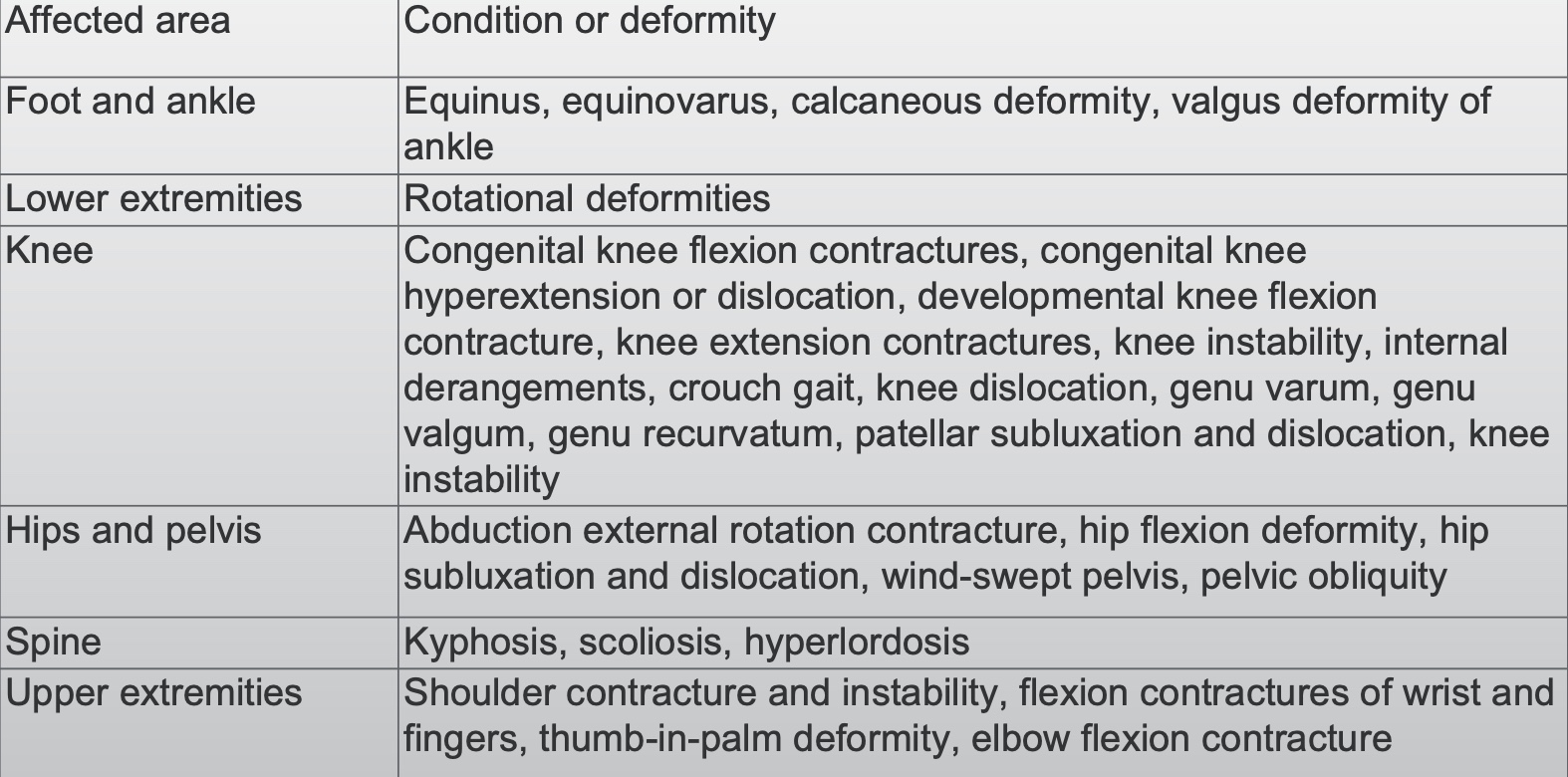

Figure 26. Areas affected by contractures.

- Do it: Early high-intensity self-generated active movement to prevent onset of weakness, disuse and contracture

- Includes functional movements & standing/weight-bearing

- Addition of Botox to manage spasticity is helpful

Early active movement, weight-bearing, and adding Botox when needed are important.

- May help manage contractures by eliciting antagonist muscle activity that counterbalances involuntary agonist muscle contractions

- Do it:

- ankle robotics

- biofeedback

- botulinum toxin plus electrical stimulation

- whole-body vibration

We can also add robotics, biofeedback, Botox plus E-stim, and vibration. There is some evidence to show these interventions work.

- Ineffective

- Stop: Neurodevelopmental Therapy (NDT)

- Hold off: Stretching in isolation

Things that do not work are NDT and just plain old stretching.

- Do it: Once contracture begins to develop, serial casting can reduce or eliminate early/moderate contractures in the short term

- Joints must be correctly aligned

- Effective for increasing ROM, enhanced when combined with Botox

- Does not impact spasticity itself

- Various protocols exist, but casts are generally changed 1-2x/week for 4-6 weeks

- Serial casting should be followed by active strength training and/or goal-directed training

Once a contracture begins, this is when serial casting is indicated. We need to align joints correctly, so it is essential the person is trained in serial casting. It improves the range of motion but does not change the tone or the spasticity. It puts the joint in a better, more healthy position.

- For severe and longstanding contractures (greater than 20°)

- Stop: Casting is not sufficient in isolation

- Discuss surgical options – tendon transfer, joint fusion, osteotomies

- Follow surgery with functional strengthening!

- Do it: Single-event multi-level surgery (SEMLS)

- Simultaneously addresses multiple contributors to contracture and maladaptive movement

- Minimizes repeat surgeries

- Stop: Casting is not sufficient in isolation

For more severe contractures, casting is not sufficient. This is when we need to refer to surgeons for something called SEMLS, or a single event multi-level surgeries. We can address multiple areas of the child's body in numerous surgeries simultaneously. It is also used a lot for lower extremities for gait and posture.

OT for CP - Overview

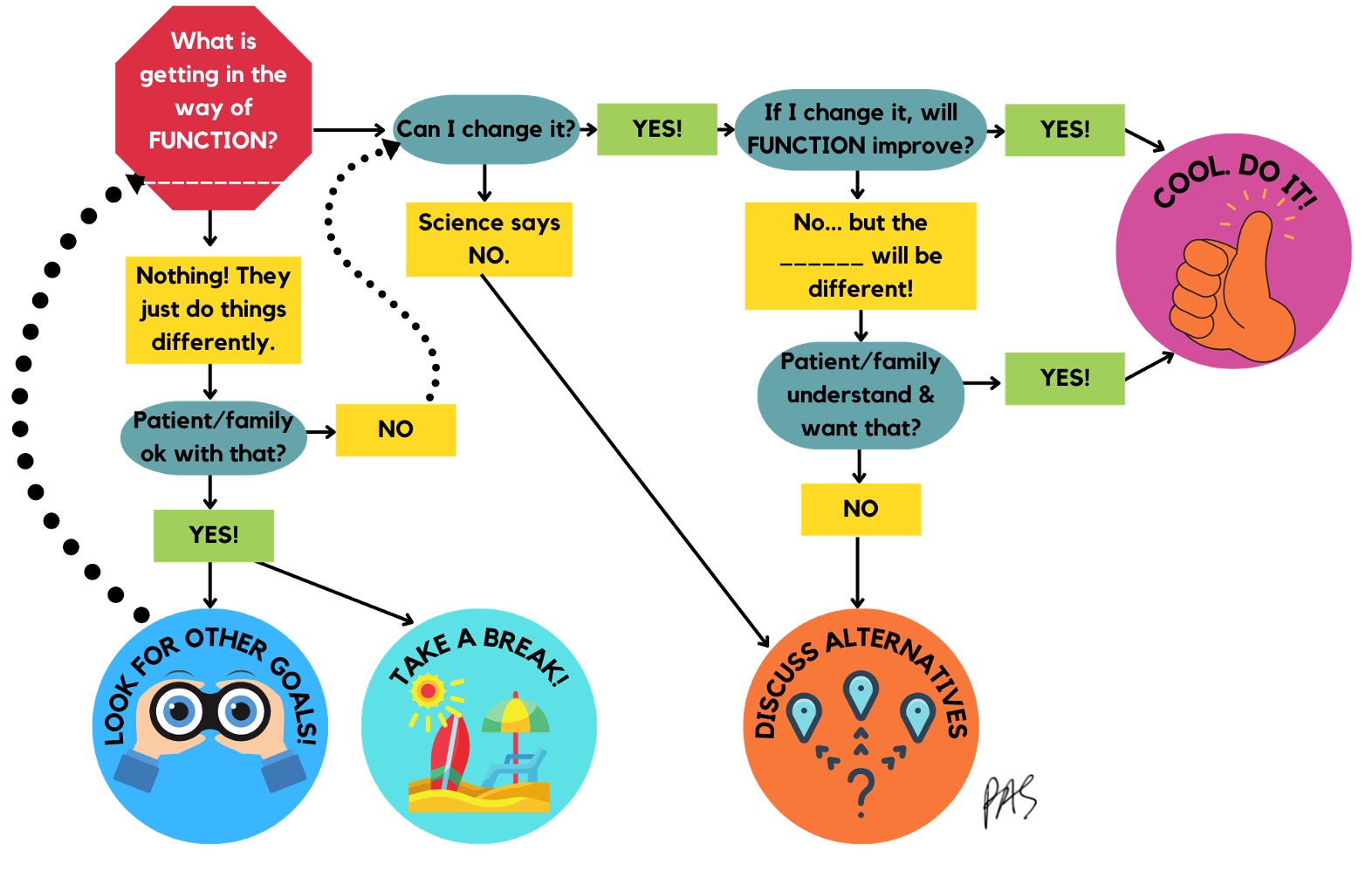

Here is an overview of OT for CP shown in a decision tree (Figure 27).

Figure 27. Decision tree about OT interventions for CP. Click here to enlarge the image.

First question, what is getting in the way of what they want to do? If it is nothing, they just do things differently or all with one hand. Are the patient and family okay with that? If they are, you can look for other goals. Science says you cannot change their tone or reflexes, so you must discuss alternatives. If science says, yes, you can change something, then do it. For example, will their function improve if I improve their range of motion or reduce the contracture? If yes, do it. If their joint range will improve but their function will not, is that what they want? If they do not, discuss the alternatives.

Here is a video with a mother discussing her child's case.

Video 3: CP Case Study

Early Interventions

- CIMT

- Bimanual Training

- Goal-Directed Training

- Night splinting

- Home programming

For this same case study, the mother discusses the different interventions.

Video 4: CP Case Study- CIMT

Video 5: CP Case Study – CIMT + Botox

Video 6: CP Case Study – Episodes of Care

Video 7: CP Case Study – Value of OT

Summary

I hope these videos help provide an excellent summary and wrap-up. If anyone has any questions, please reach out to me. Thanks for joining us today.

References

Please refer to additional reference handout.

Citation

Sharp, P. (2022). Cerebral palsy review: Medical and therapy management. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5537. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com