Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome And Long COVID: OT Strategies, presented by Zara Dureno, MOT.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the biological mechanisms of chronic fatigue.

- After this course, participants will be able to list techniques for enhancing the client’s self-management of fatigue.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify regular forms of pacing and pacing with these disorders.

Introduction/Who I Am?

- Zara Dureno, BA/MOT

- 4 years working in neurological rehab

- 2 years running my own clinic- focus on mental health and chronic pain

I have a master's in occupational therapy from the University of British Columbia in beautiful BC. This is me on top of one of the mountains here in British Columbia. I also have an undergraduate degree in neuroscience and psychology. I've been super interested in the brain since I was a kid, and I'm very passionate about this stuff.

I'm always excited to talk to people about it. I've been working in neurological rehab for four years, and I also run my own clinic with a focus on mental health and chronic pain. Within that clinic, I see a lot of people with chronic fatigue syndrome. Since I wrote this bio, I've also been running courses for people with chronic fatigue syndrome with a doctor in BC. So, I've had even more experience with that clientele in the last couple of months. Let's get into it.

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)

- "Debilitating disease with core symptoms of fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, postexertional malaise (PEM), and cognitive dysfunction for more than 6 months [1]. This disorder affects individuals of all ages across all socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups, ‘approximately estimated 1% of the population,’ 17 to 24 million people worldwide”

- “The clinical impact of ME/CFS left 27% of the ME/CFS patients bedridden and 29% housebound, leading to 50% unable to work full time and 21% unable to work at all”

(Lim & Son, 2020)

Let's discuss myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is a debilitating disease with core symptoms that include fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, and post-exertional malaise. It's crucial to understand post-exertional malaise because it's a core identifying feature of this condition. Unlike other fatigue-related conditions, such as untreated thyroid disorders or iron deficiency, ME/CFS uniquely involves post-exertional malaise.

Post-exertional malaise refers to the worsening of symptoms following physical or mental exertion that would not have caused problems before the illness. This is an important distinguishing feature that helps identify ME/CFS. We'll explore post-exertional malaise in our clients and how we might support them when they experience it.

Additionally, people with ME/CFS often suffer from cognitive dysfunction. This condition is usually diagnosed after symptoms persist for more than six months. ME/CFS can affect anyone, including children and older adults. Approximately 17 to 24 million people worldwide are affected by this condition.

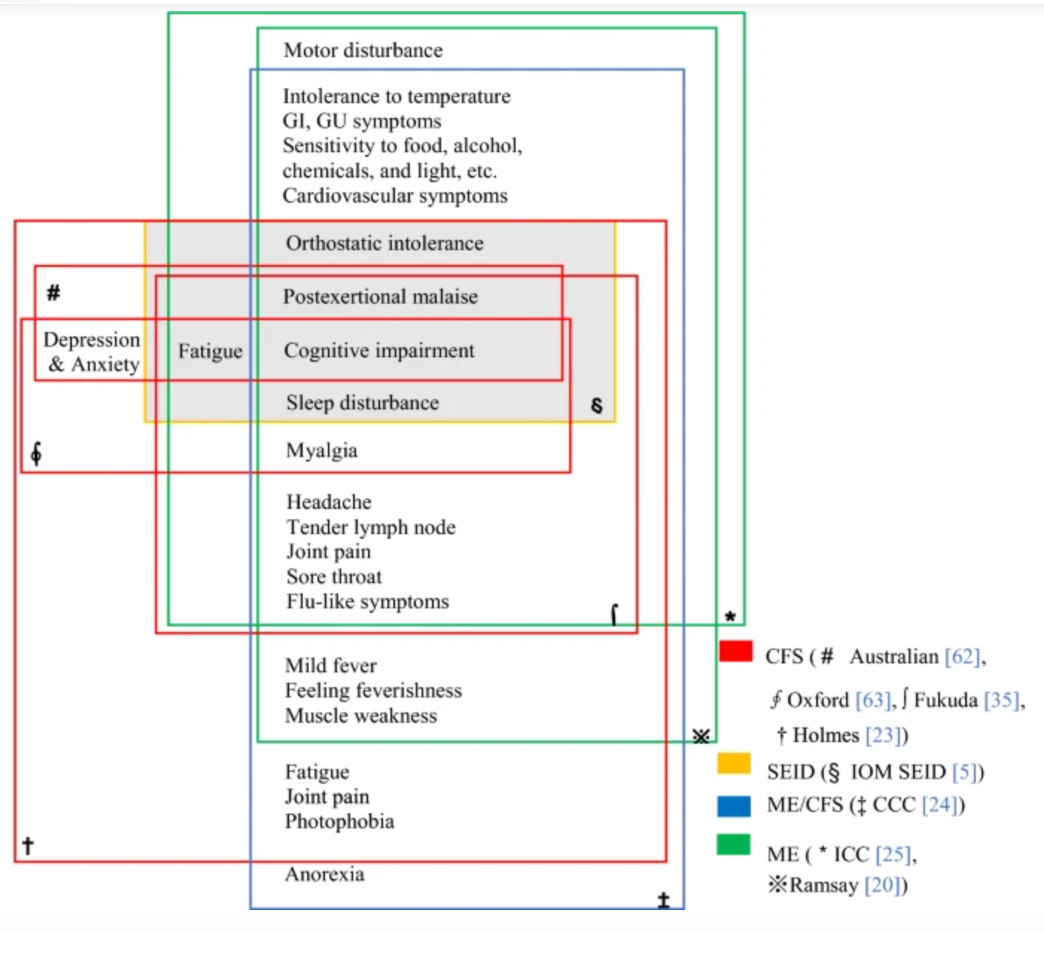

Figure 1 is a graph from 2020 research.

(Lim & Son, 2020)

Figure 1. Research on myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (Click here to enlarge the image).

Before the pandemic, research indicated that a significant number of clients with ME/CFS were already bedridden and housebound, heavily impacting their occupations. When someone cannot leave their bed, many activities they used to enjoy and find meaningful become impossible. This is where occupational therapists must get creative in engaging these clients in meaningful activities. Meaningful activities are crucial for helping people function and feel better, but finding suitable activities becomes challenging with a limited energy envelope.

For clients with limited usable energy, bringing them back to meaningful activities requires creativity. They might only have a few hours of usable energy each day and need to engage in activities from bed, which looks very different from clients with varying energy levels. About 50% of ME/CFS clients cannot work full-time, some are on a gradual return to work, and 21% are unable to work. This highlights the debilitating nature of the syndrome without implying hopelessness; rather, it underscores the need for understanding and appropriate support.

ME/CFS clients are often stigmatized and misunderstood within the medical system, similar to those with post-concussion syndrome. Despite looking healthy, their debilitating condition is often not recognized by society or medical professionals, leading to dismissal and medical trauma. Therefore, when first meeting these clients, validation is crucial. Validating their experiences and acknowledging the impact on their valued occupations goes a long way in building trust and understanding.

Research on chronic fatigue syndrome can be confusing due to different acronyms and symptom constellations worldwide. It's called ME/CFS in Canada, and it covers many symptoms. Post-exertional malaise is a common symptom, along with sleep disturbances, cognitive impairment, and orthostatic intolerance. Many people with ME/CFS also have POTS, where standing up significantly changes their heart rate.

Additional symptoms can include flu-like symptoms, headaches, tender lymph nodes, joint pain, sore throat, fever, muscle weakness, light sensitivity, and GI symptoms. Multiple chemical sensitivities (MCAS) are also common, making clients sensitive to smells, sounds, and lights. This requires consideration of the clinic environment, ensuring it is scent-free and mindful of lighting and external sounds to avoid triggering these sensitivities.

These various symptoms can significantly impact someone's life. Understanding and accommodating these symptoms in a clinical setting is crucial for providing effective support and interventions for ME/CFS clients.

Post-Exertional Malaise

- DEFINING factor

- Exercise/cognitive functioning/emotional distress induces malaise- exertion can be very minimal

(Vernon et al., 2023)

Post-exertional malaise (PEM) is indeed a central and defining symptom of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), also known as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME). It is characterized by a significant exacerbation of symptoms following physical, cognitive, or emotional exertion that can be minor or routine for most people but debilitating for those with CFS/ME. This worsening of symptoms can last for days, weeks, or even longer.

When working with clients who have CFS/ME, it's crucial to understand their unique "energy envelope"—the amount of activity they can handle without triggering PEM. This envelope varies greatly among individuals. For some, even minimal activities like walking to the bathroom can cause severe symptoms, while others might manage more significant physical activity before experiencing a crash.

PEM can manifest from physical exertion, cognitive tasks, and emotional stress. Thus, pacing strategies must encompass all these areas. Educating clients about this comprehensive approach to pacing is vital because traditional pacing often focuses solely on physical activity.

The symptoms of PEM can be severe and debilitating, often described by clients as feeling like they have the flu or have been hit by a truck. This can include intense fatigue, muscle and joint pain, headaches, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, and cognitive issues such as brain fog.

The underlying cause of PEM is not entirely understood, but mitochondrial dysfunction is believed to play a significant role. In people with CFS/ME, the mitochondria—responsible for producing energy in cells—do not function properly, leading to a lack of energy and an inability to recover from exertion as healthy individuals do. This mitochondrial dysfunction explains why exertion leads to worsened symptoms rather than the expected benefits seen in healthy people.

Causes

- Infectious agents (viral, bacterial, fungal)

- (Wu et al., 2022)

- Abnormal immune response

- (Bansal et al., 2022)

- Trauma

- (De Venter et al., 2017)

Some potential causes of ME/CFS and long COVID are known. For long COVID the cause is clearly the COVID-19 virus. However, the causes of ME/CFS can vary. Infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, and fungi can be triggers. For example, some people on my caseload have had exposure to toxic molds, which created their symptoms. Others have had severe bacterial or viral infections.

Abnormal immune responses also play a role. Some people have a genetic predisposition that makes their immune system more likely to develop ME/CFS. Trauma is another significant factor. This trauma could be psychological, such as from childhood, or physical, like a car accident. I see this quite a bit in my caseload.

It's important to note that many clients with ME/CFS have been dismissed by healthcare providers, with their symptoms attributed to psychological issues. They are often told that it's all in their head or that they are just depressed. When considering trauma as a factor, it's crucial to recognize not just the psychological impact but also how trauma can affect the body physically.

Factors Causing or Perpetuating ME/CFS

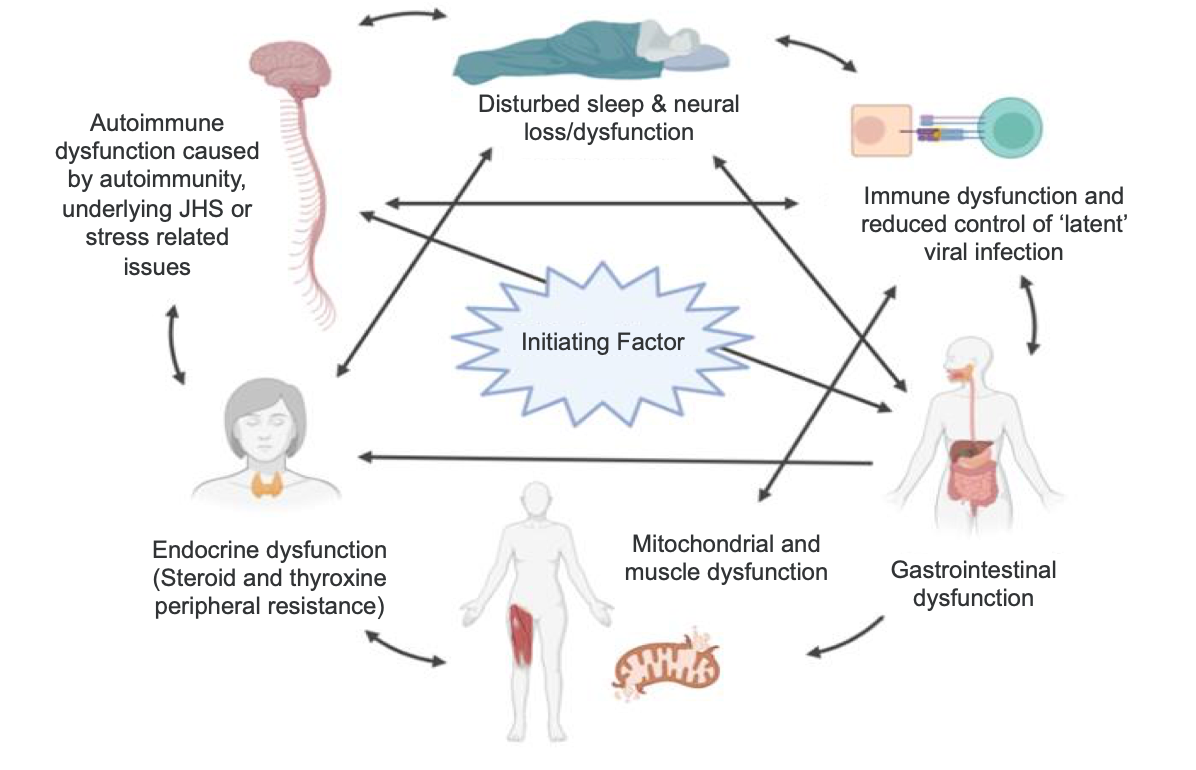

You can see in Figure 2 some of these potential causes.

Bansal et al, 2022

Figure 2. Factors causing ME/CFS (Click here to enlarge this image).

They're all factors that overwhelm our nervous system. When a particularly nasty viral infection interacts with someone's system in a certain way, it triggers a cell danger response. Encountering a virus, a fungal infection like black mold, or severe trauma pushes the nervous system into survival mode. This involves the autonomic nervous system switching to fight, flight, freeze, or fawn responses. Additionally, our cells, especially the mitochondria, respond by entering a protective state.

Mitochondria, known as the powerhouse of the cell, typically produce energy. However, in a survival situation, they shift from energy production to slowing cellular activity to prepare us for survival. In chronic fatigue syndrome, the mitochondria become chronically dysfunctional. This means they're not efficiently producing energy for the brain and body, leaving the cells suboptimal.

People with chronic fatigue often oscillate between survival responses, such as fight or flight, which leads to severe anxiety. This anxiety isn't the cause of the disorder but rather a response to the nervous system's attempt to protect itself from an initial threat. They may also experience freeze or faint states, which are protective responses where the body becomes very fatigued and immobile as a defense mechanism.

This constant imbalance in the nervous system means the alarm has been set off and never turned off. The nervous system continuously tries to rebalance itself after the threat but fails for various reasons, including individual biological and psychological differences. Therefore, ME/CFS involves numerous factors, making it frustrating when doctors dismiss it as mere depression. Clients often share stories of being dismissed despite having significant physical issues.

An initiating factor, such as an infection or trauma, triggers a cascade of immune, autonomic, and endocrine dysfunctions. Many people with ME/CFS also experience mitochondrial dysfunction, gastrointestinal issues, cortisol and immune deficiencies, and disturbed sleep. These physical changes are extensive.

However, there's hope. Regulating the nervous system can reduce some of these physical symptoms. It's not a hopeless situation because various approaches can address the different aspects of the condition. A multidisciplinary care team is essential. Occupational therapists are well-positioned to support aspects like sleep, nervous system regulation, and mental health support, helping clients feel safer in their bodies.

Working with a knowledgeable doctor, possibly including medications, a naturopath, or a functional medicine doctor, can provide a comprehensive treatment approach. This team effort can support clients effectively, considering all facets of their condition.

Co-morbidities

- Fibromyalgia

- Post-concussion Syndrome

- Orthostatic Intolerance

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Multiple Sensitivity Disorder

- Migraines

- *Since there is no official test, this is a RULE out disorder.*

Nacul et al., 2020

Some of the comorbidities we often see with ME/CFS include fibromyalgia, post-concussion syndrome, orthostatic intolerance, irritable bowel syndrome, and PTSD. Many of my clients have PTSD, either stemming from their childhood or from the event that caused their ME/CFS. Additionally, medical trauma and trauma from accidents or dealing with insurance agencies post-accident are common.

When working with clients, it's crucial to consider these possibilities. Multiple sensitivity disorders and migraines are also frequent. The common thread among these conditions is that they are all sensitized syndromes. This means that something has happened to sensitize the nervous system.

There is a nervous system component to these conditions, as evidenced by the prevalence of autonomic nervous system changes among sufferers. However, there is no definitive test for ME/CFS, so doctors must rule out other potential causes of fatigue. Conditions like iron deficiency, thyroid problems, and diabetes can also cause fatigue, and these must be excluded before a diagnosis of ME/CFS can be made.

Understanding the broad range of comorbidities and the nervous system's role in these conditions helps us provide more comprehensive and empathetic care. By acknowledging the complex interplay of factors contributing to ME/CFS and its related conditions, we can better support our clients through their recovery and management journey.

Prognosis

- “Although recovery and improvement rates varied widely across different studies, almost all studies agree that ME/CFS prognosis is rather unfavorable.

- Recovery rates ranged from 0% to 8%.

- Improvement rates from 17% to 64% were reported according to studies.”

- *It is unlikely that a client will recover fully, but there is some evidence to suggest improvements are possible.

Ghali et al., 2022

Studies show that full recovery rates for ME/CFS are quite low, ranging from zero to 8%. This statistic can make the prognosis seem bleak. However, the range of improvement rates is higher, and I firmly believe that with the right care, most people can improve and gain significant function. I’ve seen individuals progress from being bedridden to hiking, which demonstrates that improvement is possible.

When considering recovery, it’s essential to recognize that total recovery is a contentious topic in rehabilitation. Whether dealing with a stroke, a severe traumatic brain injury, or ME/CFS, individuals may never return to their pre-condition state. While full recovery might not be attainable, improvement certainly is. Encouraging hope is crucial because it can be half the battle. Many people with ME/CFS feel hopeless about making any changes, so it’s vital to emphasize that change is possible, symptoms can be managed, and function can be regained. Some people do recover.

I often encourage my clients to look up recovery stories online. A great resource is a YouTube channel run by Raelyn, who shares inspiring recovery stories and offers excellent educational content. Searching for “Raelan CFS” on YouTube can provide inspiration and practical advice. Listening to recovery stories is important because hope is vital, and some people recover.

Recovery and improvement rates vary widely across studies, making it challenging to pinpoint exact figures. This area of research is still evolving, but most studies agree that the prognosis for ME/CFS is generally unfavorable. Despite this, while full recovery might not be likely, significant improvement is possible.

In Canada, we use the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) to understand clients’ occupational goals. We focus on narrowing down reasonable goals for the next three months, six months, and a year, working towards these goals within a SMART framework. By instilling hope and setting achievable goals, we can help clients improve their quality of life while maintaining realistic expectations.

What Is Long COVID?

- Lots of overlap with ME/CFS but not synonymous

- Symptoms:

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Loss of taste or smell

- Brain fog

- Heart/lung abnormalities

- Mood swings

- PEM but: “There were many significant differences in the types of PEM triggers, symptoms experienced during PEM, and ways to recover and prevent PEM between Long COVID and ME/CFS.” (Vernon et al., 2023)

Garg et al., 2021

The similarities between long COVID and ME/CFS are striking, particularly in the presence of post-exertional malaise, extreme fatigue, headaches, and flu-like symptoms. However, there are also some notable differences. Long COVID, depending on the individual, may impact the heart and lungs, leading to tissue damage, breathing pattern problems, and the formation of microclots—small blood clots in various parts of the body. These additional complications differentiate long COVID from ME/CFS.

Long COVID remains somewhat mysterious due to the relatively short time since the pandemic began, leaving research still catching up. While many symptoms of long COVID overlap with ME/CFS, certain aspects, such as loss of taste or smell and heart and lung abnormalities, are typically not seen in ME/CFS. Furthermore, the triggers for post-exertional malaise can differ between the two conditions.

In my practice, I emphasize understanding each client's triggers for post-exertional malaise. These triggers can be physical, cognitive, emotional, or environmental, particularly for those with heightened sensitivities. Identifying these triggers allows for better management and planning of activities. This approach is akin to working with clients who have migraines or chronic pain—understanding triggers not to avoid them entirely, but to manage exposure and mitigate symptoms effectively.

Role of Occupational Therapy

- ME/CFS affects physical, cognitive, and affective functioning.

- It impacts all occupations: Leisure, Productivity, and Self Care.

- “Environmental barriers to participation included stigma and misunderstanding of ME/CFS, financial hardship, lack of appropriate health services, and strains on personal support networks and relationships.”

Bartlett et al., 2022

As occupational therapists, our role is crucial in supporting individuals with ME/CFS, given its impact on physical, cognitive, and affective functioning. ME/CFS affects all aspects of daily living, including leisure, productivity, and self-care. Our expertise uniquely positions us to address these challenges and facilitate significant improvements in our clients' lives.

The essence of occupational therapy is to engage people in meaningful occupations to help them gain function and recover. We can make a substantial difference by identifying our clients' interests and helping them creatively and adaptively engage in those activities. For example, I once worked with a client who loved hockey. He used to play several times a week with his children and friends, which was an important social and recreational activity for him. Despite his condition, we set up a small net in his garage, allowing him to shoot pucks with his child. This adaptive approach enabled him to continue participating in a beloved activity with less physical exertion.

Our creative and adaptive thinking as occupational therapists is key to helping clients with limited energy still engage in meaningful activities. Beyond the physical and cognitive aspects, ME/CFS also brings stigma and misunderstanding. Many clients face environmental barriers, such as financial hardship due to being unable to work, lack of appropriate health services, and insufficient education about their condition.

A vital part of my approach involves discussing clients' relationships with their families and support systems. Ensuring that their families understand ME/CFS is crucial. Many people are unaware of the complexities of the condition, so I provide educational materials to the patient's family and friends. Simple searches like "chronic fatigue family and friends pamphlet" yield numerous resources from various societies that explain the condition and its limitations.

Additionally, resources such as the MeTV channel on YouTube offer videos designed for family and friends to enhance their understanding of ME/CFS. Educating the support network can significantly improve social support, a critical aspect of managing the condition.

Treatment Strategies

Let's talk about treatment strategies and what we can do and sort of a little bit more about our role.

Goals of Treatment

- “Improvement of current symptoms, functioning, and quality of life.

- Prevention of worsening symptoms.

- Help patients cope with the emotional impact and grieve the losses that have resulted from having a chronic, complex, debilitating illness.

- Prevention of the development of depression and potential suicide by managing the physical and emotional issues resulting from ME/CFS.

- Prevention of new environmentally-associated illnesses with worsening of the condition, such as multiple chemical sensitivity.”

Bested & Marshall, 2015

Some of our treatment goals for ME/CFS include improving current symptoms, functioning, and quality of life. Enhancing quality of life is a primary focus, considering the condition's chronic, complex, and debilitating nature.

We aim to prevent the worsening of symptoms and help patients cope with the emotional impact of ME/CFS. This involves supporting them as they grieve the losses they have experienced, whether it's the loss of their previous level of functioning or their ability to work or engage in social activities. Addressing these emotional aspects is crucial to prevent the development of depression and the risk of suicide, which can be common in this population.

Having open and honest conversations about suicide is essential from the start. I often use the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 questionnaires to assess levels of anxiety and depression. The PHQ-9, in particular, includes a question about thoughts of being better off dead or hurting oneself. If a client indicates any level of these thoughts, it opens the door for a candid discussion about their feelings and considerations. If necessary, we can develop a safety plan to ensure their immediate safety, discuss counseling options, and potentially involve their doctor in the conversation.

Another goal is the prevention of new environmentally associated illnesses. Managing multiple chemical sensitivities involves reducing exposure to harmful chemicals and fungi. Evaluating and adjusting their environment is vital to minimize triggers and improve overall well-being.

Pacing

- Not using Graded Exercise Therapy (Bested & Marshal, 2015)

- Green/Yellow/Red Zones

- Point system or “Spoons”

- Physical, cognitive, and emotional

- Evaluate environment for triggers: “Minimize those stimuli to which the patient is sensitive, such as light, noise, touch, movement, chemicals, and odors. Exposure to these could increase pain and other symptoms. The most severe patients may not be able to tolerate any touch, light or noise.” (Montoya et al., 2021)

- Modification and adaptation strategies

Kos et al., 2015

As I said earlier, we were going to discuss pacing and how it differs for people with ME/CFS.

The main difference is that people with ME/CFS will experience post-exertional malaise if they're pushed too much. We must avoid graded exercise therapy and ensure that any kinesiologists or physiotherapists involved are on the same page that they are not doing graded exercise therapy. Graded exercise therapy involves giving exercises that increase incrementally every week or every couple of weeks without considering the feedback from the nervous system or the body. This approach can push clients into post-exertional malaise and make their condition worse. There is substantial research indicating that this is not beneficial for people with ME/CFS.

Instead, we should use different pacing systems tailored to the client's energy levels. Some clients might use spoon theory, where they start the day with a certain number of metaphorical spoons, and each activity requires a different number of spoons. When they run out of spoons, it’s time to rest. Another method is the pacing point system, where activities are assigned points, and clients have a daily point limit. For example, attending a child's soccer game might be five points, while making a snack might be one point. Together with the client, we determine a reasonable daily point limit. However, these intensive systems can sometimes cause anxiety, so they need to be tailored to each client’s preferences and needs.

A method I favor is adapted from concussion rehab: using green, yellow, and red zones. The green zone represents the client's baseline, with no symptoms or manageable symptoms. The yellow zone occurs when activities push them slightly, causing discomfort but allowing quick recovery within an hour or two. The red zone signifies significant overexertion, leading to a prolonged increase in symptoms, which we aim to avoid. Educating clients on recognizing when they are moving into the yellow or red zones helps them manage their activities and avoid crashes, which I prefer to call "increases in symptoms."

Micro breaks and awareness of their body's signals are essential in helping clients manage their energy levels. Life’s demands, like parenting or caregiving, may make it difficult to avoid overexertion, but encouraging clients to take micro-breaks and stay attuned to their body's signals can help.

It's also important to note that post-exertional malaise can be delayed, sometimes showing up two days after the triggering activity. This delay necessitates a modified approach to pacing. We should monitor the client's response over the next two days when introducing new activities, such as increasing steps from 1000 to 1500 per day. If they don’t experience increased symptoms, we can continue progressing. This careful, incremental approach helps avoid pushing the client beyond their limits.

Overall, the goal is to help clients increase their functioning slowly and steadily, recognizing that pacing for ME/CFS must be approached more cautiously than for other conditions. By doing so, we can help clients improve their quality of life and manage their symptoms more effectively.

Sleep Hygiene

- Work with light: Very dark room (Mason, 2023), Direct sunlight when waking and in afternoon (Huberman, 2023)

- Delay caffeine 90 mins-2 hours after waking (Huberman, 2022)

- Low room temperature (Te Kulve, 2017)

- Cold in the morning, heat at night (Huberman, 2021)

- Don’t set multiple alarms

Sleep hygiene is crucial, especially for clients with ME/CFS and long COVID, who often experience disturbed sleep due to cortisol system disruptions. While you're familiar with general sleep hygiene, here are some additional considerations that might not be on typical sleep hygiene lists.

Firstly, working with light is essential. A dark room is optimal, so I recommend a sleep mask if blackout curtains aren't an option. Even a little light can disrupt sleep. Upon waking, direct sunlight exposure is vital. Within 5 to 10 minutes of waking, clients should get direct overhead sunlight into their eyes. This could mean having breakfast outside or using an overhead sunlamp during winter.

Delaying caffeine intake is another important tip. If clients consume caffeine, it should be delayed for 90 minutes to 2 hours after waking to allow for the natural progression of cortisol. The optimal room temperature for sleeping is around 18 degrees Celsius. Cold exposure in the morning and heat exposure at night can also help regulate sleep. For instance, if a client practices cold exposure, they should do it first thing in the morning. Conversely, hot showers or baths should be taken at night, as heat induces sleepiness and cold wakes us up.

Additionally, avoiding multiple alarms is crucial. Setting multiple alarms can disrupt the natural production of wake-up hormones and chemicals, leading to sleepiness throughout the day. It's better to have a single alarm and get up immediately.

Incorporating these tips and standard sleep hygiene practices—such as avoiding screens before bed and maintaining a consistent sleep routine—can significantly improve clients' sleep quality. By combining traditional sleep hygiene with these newer insights, we can better support our clients in achieving restorative sleep.

Accommodations

- School

- Discuss with disability services prior to school beginning

- Minimize travel: Online options, Handicapped parking permits

- Test accommodations: Limited number of tests in one day, extra time, alternative testing (oral), quiet space for exams

- Flexibility to leave class when needed and an appropriate resting area

- Educate staff on ME/CFS

(Chu et al., 2020)

- Work

- Anti-fatigue mats/shoe insoles

- Adaptive/ergonomic equipment

- Earplugs/sunglasses

- Flexible hours or ability to work from home

- External memory strategies, AI organizers

If a client is still in school, I always like to discuss potential accommodations with disability services. Many options are usually available to help reduce the energy expenditure required for school activities. Online class options, parking permits close to school buildings, and other accommodations can be useful.

For test accommodations, it’s important to consider a limited number of tests in a day, extended time for exams, oral testing rather than written, and providing a quiet space for exams. Flexibility to leave class when needed and having an appropriate resting area are also critical considerations.

A significant part of our role in these situations is educating the clients, their families, and their schools or workplaces. This education ensures that everyone understands the condition and knows how to support the client effectively.

For clients in the workplace, consider anti-fatigue mats, shoe insoles, and adaptive ergonomic equipment. These can help the body use less energy. Managing environmental sensitivities is also crucial, as well as ensuring flexibility in work hours and the ability to work from home, which many companies now offer.

Memory strategies and AI can also be invaluable tools. AI offers numerous adaptive solutions, and there are many innovative ways we can use technology to help clients conserve energy. Getting creative with technology can significantly improve the efficiency and comfort of our clients’ daily activities.

Support Cognition

- Pacing

- External strategies (calendars, phones, notebooks)

- Internal strategies (repetition, meaning-making, chunking, mnemonics)

We can also support their cognition. Unlike clients with stroke or severe traumatic brain injury, ME/CFS clients do not typically exhibit primary cognitive dysfunction, where a part of the brain is dead tissue. Instead, their cognitive issues are usually secondary to fatigue, pain, and other symptoms. Therefore, specific cognitive training is often unnecessary.

However, we can provide them with various strategies to help manage cognitive difficulties. External reminders such as calendars, phones, notebooks, and sticky notes can be very helpful. Additionally, we can suggest internal strategies, such as repeating information in their mind or creating meaningful associations with names to improve memory. Techniques like chunking and mnemonics can also be beneficial.

Rather than focusing on cognitive training, which is not typically required for these clients, we should prioritize managing their fatigue, pain, and other symptoms. Often, as these symptoms improve, their cognitive function naturally improves. However, if a client expresses interest in cognitive training, we can explore that option.

Nervous System Regulation

- Manage the ”freeze” and “faint” responses (Porges, 2018)

- Techniques:

- Physiological sigh (Balban et al., 2023)

- Singing, humming (Fancourt et al., 2016)

- Bilateral stimulation: Eyes, butterfly hug, 8D music (Reichel, 2022)

- Weighted blanket (Eron et al., 2020)

- Co-regulation (Eisenberger, 2017)

- Mindfulness (Querstret, 2020)

One of the major things I do with my clients is teach nervous system regulation skills. Clients with ME/CFS often experience freeze and faint responses, leading to dysregulation. Helping their nervous system return to a parasympathetic, "rest and digest" state can make a significant difference.

One effective technique is the physiological sigh, which involves two quick inhales and a long exhale as if fogging up a mirror. Practicing this throughout the day, even for five minutes, can reset the nervous system by offloading CO2 and promoting a parasympathetic state.

Singing and humming are also beneficial, as humming increases nitric oxide in the blood, which has anti-inflammatory effects and helps regulate the nervous system. Bilateral stimulation can be soothing, such as the butterfly hug, where clients cross their hands over their chest and tap alternately. 8D music, which moves from one ear to another, can also create a sense of safety and relaxation.

For some clients, proprioceptive feedback through deep pressure stimulation, like using a weighted blanket, helps them feel more grounded and secure. Co-regulation is crucial; being regulated yourself during sessions, with warmth and a smile, can create a safe space for clients. Encouraging them to co-regulate with pets or family members can also be beneficial.

Mindfulness techniques are another valuable tool for resetting the nervous system. Teaching clients simple mindfulness exercises can help them achieve a calm state.

I am developing a comprehensive course on nervous system regulation and writing a book on the subject. If you're interested in more information, please email me, and I can provide details about the course and book once they are available.

Sensory Modulation

- Energize

- Smell citrus

- Taste peppermint

- See bright patterns

- Hear an energizing song

- Feel a splash of cold water

- Move quickly, spin, or balance

- Calm

- Smell lavender

- Taste chamomile

- See a cool color

- Hear nature sounds

- Feel a weighted blanket

- Move or rock slowly

Kandlur, 2023

I'm happy to discuss sensory modulation as well. As occupational therapists, we excel at considering sensory inputs, which is something Deb Dana, a polyvagal researcher, emphasizes. She talks about "glimmers," or little things in our environment that help bring us into regulation.

Identifying energizing sensory inputs can be beneficial for clients experiencing a slump. For example, they might smell citrus, taste peppermint, see bright patterns, or hear an energizing song. Conversely, when clients feel overwhelmed and need to calm their nervous system, they might engage with smells like lavender, taste chamomile, see cool colors, or hear nature sounds.

Helping clients create a personalized list of sensory inputs that energize or calm them can be very useful. This list can be a toolkit for them to manage their sensory environment and maintain daily regulation.

By integrating these sensory modulation strategies, we can further support clients in managing their symptoms and improving their overall well-being.

Managing Mental Health

- Cognitive Behavior Therapy

- (Adamson et al., 2020)

- Exploring values and meaningful activity

- Support groups

Managing mental health is another critical aspect of supporting clients with ME/CFS. If you're trained in it, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can be particularly useful. We often talk about top-down and bottom-up approaches. Top-down approaches include therapies like CBT or dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), while bottom-up approaches encompass methods like somatic therapy, polyvagal theory, and internal family systems therapy.

If you're not trained in these therapies, it's essential to help clients find a counselor who is. Combining top-down approaches with bottom-up approaches can be very effective. Since many ME/CFS cases involve an initial trauma, treating this trauma and helping clients feel safe in their bodies can lead to profound changes, even at the cellular level, including the mitochondria.

We have discussed the importance of values and meaningful activities extensively. Support groups can also be beneficial, but it is crucial to ensure they are moderated. Unmoderated support groups can sometimes exacerbate negative feelings and experiences, so moderation is key to providing a safe and supportive environment.

Here are some additional resources that can be helpful:

- The Post Viral Podcast- by Lindsay Vine: This podcast offers valuable insights and is highly recommended.

- The Gupta Program- A neural retraining program that clients can use to help manage their symptoms.

- The Curable App- This app offers some free resources and can be a useful tool for clients.

Deb Dana's books on polyvagal theory are excellent resources for further learning and applying these concepts in clinical practice.

By integrating these mental health strategies and resources, we can provide comprehensive support that addresses the psychological and physiological aspects of ME/CFS, helping clients achieve better overall well-being.

Summary

Hopefully, you were able to learn the outcomes from this course. Thank you so much for paying attention and learning with me.

Questions and Answers

Where do you access 8D music?

You can find it if you type in "8D music" on Spotify, YouTube, or any other music platform. I recommend typing "8D" followed by a genre or type of music you enjoy. For example, you might search for "8D music EDM," "8D music classical," "8D music country," or "8D music relaxing." This way, you can find 8D music that suits your preferences.

Do you have any advice when working with somebody resistant to slowing down or giving up any responsibility? Due to this, they continue to have exertional malaise other than strategies to monitor their energy level. Do you have any suggestions to help them cope with this life change?

Working with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can be very effective when clients resist slowing down. Often, this resistance stems from underlying cognitions, such as feeling unworthy if they slow down or believing they must take care of everyone else.

By challenging these thoughts, we can help clients reframe their perspectives. Providing education about post-exertional malaise is also crucial. When clients understand that repeatedly pushing themselves into the red zone leads to worsening symptoms and diminished capacity, they can begin to see the value in pacing. I often explain that "slow is fast"—the more we slow down and pace ourselves, the more we can expand our capabilities in the future. However, if we continue pushing ourselves, we remain stuck in a cycle of overexertion and setbacks.

Explaining this concept to clients can be helpful, although it often requires multiple conversations. Our society frequently values constant activity and productivity, so it can be challenging for clients to adjust their mindset. Nonetheless, consistent education and reinforcement can gradually help them adopt healthier practices and improve their well-being.

Are there pre-existing conditions that make someone more susceptible to ME/CFS or long COVID?

A history of trauma can make individuals more susceptible to developing ME/CFS, long COVID, and other sensitized disorders such as migraines, chronic pain, and IBS. If the nervous system is already accustomed to sensitization, it increases the likelihood of being affected by these conditions. This understanding highlights the importance of addressing and managing trauma histories to potentially reduce susceptibility to such disorders.

What kind of doctor diagnoses a patient with ME/CFS?

A family physician can diagnose ME/CFS if they have the necessary knowledge. In Canada, this is often done by a functional medicine specialist. In the United States, it might also be an internal medicine doctor. If a family doctor is unfamiliar with ME/CFS, they can refer the patient to a more knowledgeable specialist.

Do individuals come to you with a diagnosis, or do you have to help them get one from a doctor?

Sometimes, my clients will come to me and describe various symptoms they're experiencing. In such cases, I often suggest they talk to their doctor, which could be crucial in their diagnosis and treatment. I work closely with a doctor who specializes in diagnosing ME/CFS, so many of my clients come to me with an already-established diagnosis. For those who don't, I recommend that they see this doctor to determine if ME/CFS might be the underlying cause of their symptoms.

How do we educate physician referral sources about the role of OT to increase the understanding of how we can help these clients?

Often, I write notes for general practitioners (GPs), providing a brief letter that describes the client's symptoms and the role of occupational therapy. Due to the nature of our title, some GPs mistakenly believe that occupational therapists are primarily focused on return-to-work issues.

To clarify, I explain how occupational therapy helps clients engage with activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, leisure activities, and education. Sometimes, I'll outline these points in a letter to the GP or funding sources to ensure they understand the full scope of our work and how we support clients in various aspects of their lives.

What do you suggest for parents?

One thing I discuss with my clients who are parents and struggling to stay within their energy envelope is setting good boundaries. Depending on their children's ages, this might involve establishing "mommy or daddy time" with a note indicating the need for a break. Setting these boundaries helps parents take necessary breaks while teaching children about respecting others' needs.

Delegating tasks and seeking help with caregiving are also crucial. Enlisting family members, friends, or professional caregivers can provide much-needed support. Additionally, engaging in nervous system regulation activities with their children can benefit both the parent and the child. For example, teaching children physiological techniques can be engaging, as kids are often interested in these activities. Techniques like the horse breath, where you breathe in and out like a horse, can be fun for kids and provide a way for parents to take a break while also regulating their nervous system.

ME/CFS impacts children similarly to adults, presenting with symptoms such as fatigue, post-exertional malaise, headaches, and sometimes pain. Although I haven't worked with children in my practice, I know these symptoms can affect children, so applying similar strategies and support systems is important.

References

Adamson, J., Ali, S., Santhouse, A., Wessely, S., & Chalder, T. (2020). Cognitive behavioural therapy for chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: outcomes from a specialist clinic in the UK. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 113(10), 394-402

Bansal, A. S., Kraneveld, A. D., Oltra, E., & Carding, S. (2022). What causes ME/CFS: The role of the dysfunctional immune system and viral infections. J. Immunol. Allergy, 3, 1-14.

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., ... & Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1).

Bartlett, C., Hughes, J. L., & Miller, L. (2022). Living with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Experiences of occupational disruption for adults in Australia. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 85(4), 241-250.

Bested, A. C., & Marshall, L. M. (2015). Review of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: An evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Reviews on Environmental Health, 30(4), 223-249.

Chu, L., Fuentes, L. R., Marshall, O. M., & Mirin, A. A. (2020). Environmental accommodations for university students affected by myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Work, 66(2), 315-326.

De Venter, M., Illegems, J., Van Royen, R., Moorkens, G., Sabbe, B. G., & Van Den Eede, F. (2017). Differential effects of childhood trauma subtypes on fatigue and physical functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome. Comprehensive psychiatry, 78, 76-82.

Eisenberger, N. I., Moieni, M., Inagaki, T. K., Muscatell, K. A., & Irwin, M. R. (2017). In sickness and in health: the co-regulation of inflammation and social behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(1), 242-253.

Eron, K., Kohnert, L., Watters, A., Logan, C., Weisner-Rose, M., & Mehler, P. S. (2020). Weighted blanket use: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(2), 7402205010p1-7402205010p14.

Fancourt, D., Williamon, A., Carvalho, L. A., Steptoe, A., Dow, R., & Lewis, I. (2016). Singing modulates mood, stress, cortisol, cytokine and neuropeptide activity in cancer patients and carers. ecancermedicalscience, 10.

Garg, M., Maralakunte, M., Garg, S., Dhooria, S., Sehgal, I., Bhalla, A. S., ... & Sandhu, M. S. (2021). The conundrum of ‘long-COVID-19: a narrative review. International journal of general medicine, 2491-2506.

Ghali, A., Lacout, C., Fortrat, J. O., Depres, K., Ghali, M., & Lavigne, C. (2022). Factors influencing the prognosis of patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Diagnostics, 12(10), 2540.

Huberman Lab (2023). Using light for health. https://www.hubermanlab.com/newsletter/using-light-for-health

Huberman Lab (2022). Using caffeine to optimize mental & physical performance. Online here: https://hubermanlab.com/using-caffeine-to-optimize-mental-and-physical-performance/

Huberman Lab (2021). Using temperature for performance, brain and body health. https://www.hubermanlab.com/episode/dr-craig-heller-using-temperature-for-performance-brain-and-body-health

Kandlur, N. R., Fernandes, A. C., Gerard, S. R., Rajiv, S., & Quadros, S. (2023). Sensory modulation interventions for adults with mental illness: A scoping review. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 36(2), 57-68.

Kos, D., Van Eupen, I., Meirte, J., Van Cauwenbergh, D., Moorkens, G., Meeus, M., & Nijs, J. (2015). Activity pacing self-management in chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(5), 6905290020p1-6905290020p11.

Lim, E. J., & Son, C. G. (2020). Review of case definitions for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Journal of translational medicine, 18(1), 1-10.

Mason, I. C., Grimaldi, D., Reid, K. J., Warlick, C. D., Malkani, R. G., Abbott, S. M., & Zee, P. C. (2022). Light exposure during sleep impairs cardiometabolic function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(12), e2113290119.

Montoya, J. G., Dowell, T. G., Mooney, A. E., Dimmock, M. E., & Chu, L. (2021, October). Caring for the patient with severe or very severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic fatigue syndrome. Healthcare, 9(10), 1331). MDPI.

Nacul, L., O'Boyle, S., Palla, L., Nacul, F. E., Mudie, K., Kingdon, C. C., ... & Lacerda, E. M. (2020). How myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) progresses: the natural history of ME/CFS. Frontiers in neurology, 11, 826.

Naviaux, R. K. (2020). Perspective: Cell danger response Biology—The new science that connects environmental health with mitochondria and the rising tide of chronic illness. Mitochondrion, 51, 40-45.

Reichel, V., Sammer, G., Gruppe, H., Hanewald, B., Garder, R., Bloß, C., & Stingl, M. (2021). Good vibrations: Bilateral tactile stimulation decreases startle magnitude during negative imagination and increases skin conductance response for positive imagination in an affective startle reflex paradigm. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(3), 100197.

Querstret, D., Morison, L., Dickinson, S., Cropley, M., & John, M. (2020). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psychological health and well-being in nonclinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Stress Management, 27(4), 394.

Te Kulve, M., Schlangen, L. J., Schellen, L., Frijns, A. J., & van Marken Lichtenbelt, W. D. (2017). The impact of morning light intensity and environmental temperature on body temperatures and alertness. Physiology & behavior, 175, 72-81.

Vernon, S. D., Hartle, M., Sullivan, K., Bell, J., Abbaszadeh, S., Unutmaz, D., & Bateman, L. (2023). Post-exertional malaise among people with long COVID compared to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Work, (Preprint), 1-8.

Wu, T. Y., Khorramshahi, T., Taylor, L. A., Bansal, N. S., Rodriguez, B., & Rey, I. R. (2022). Prevalence of Aspergillus-Derived Mycotoxins (Ochratoxin, Aflatoxin, and Gliotoxin) and their distribution in the urinalysis of ME/CFS Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2052.

Citation

Dureno, Z. (2024). Chronic fatigue syndrome and long COVID: OT strategies. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5718. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com