Editor's Note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Client-Centered Occupational Therapy Pediatric Upper Extremity Treatment To Obtain Outcomes, presented by Valerie Calhoun, MS, OTR/L, CHT.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze who the "client" is to provide client-centered treatment for a pediatric patient with various referral sources.

- After this course, participants will be able to examine two areas of knowledge the OT has to guide the establishment of treatment outcome goals.

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze the importance of parental participation in treatment and establishing goals.

Introduction

Welcome, everybody. Today, I get to talk about a topic I feel strongly about, and I was excited when working on this lecture. I have spoken to other therapists about it throughout my career, as I think it is critical. The title is a little cumbersome, but it explains that we are focusing on client-centered treatment in pediatric settings. I will also focus on the upper extremity patient because that is the population I work with most, but the information can transfer over into any pediatric setting.

Client-Centered

World Federation of Occupational Therapy Position Statement

- In occupational therapy, the occupational therapist respects and partners with clients, values peoples' subjective experiences of their participation, and appreciates peoples' knowledge, hopes, dreams, and autonomy.

- WFOT position statement

Being client-centered is a catchphrase from about 25 years ago. The World Federation of OT came out with the statement, "In occupational therapy, the occupational therapist respects and partners with the clients, values people's subjective experiences of their participation, and appreciates people's knowledge, hopes, dreams, and autonomy." It means that we look at each person as a unique individual and treat them that way, valuing their input.

It does not matter if we think they are getting better. They need to feel that they are getting better and that their goals are being met.

British Journal of OT (2000)

- Client-centered occupational therapy is a partnership between the client/patient and the therapist, which allows empowerment of the patient to engage in functional performance to fulfill their occupational roles in a variety of environments.

- Sumsion, T. A. (2000). A revised occupational therapy definition of client-centred practice. Br J Occup Ther., 63, 304–309.

This statement is from the British Journal of Occupational Therapy in 2000.

Client-Centered Intervention Definition

- Client-centered intervention. This is an approach that takes seriously the needs, strengths, weaknesses, and explicitly articulated goals of each occupational therapy (OT) client.

The vital part of the client-centered intervention is its articulated goals. We are the experts in the field, but we need to understand that this is the collaboration we are doing with our clients. It is not us telling them what they need to work on or what needs to get better. In a pediatric setting, this can be challenging.

Client-Centered Intervention Challenges

- Practical challenges to client-centered practice include a lack of time, organizational support, and professional autonomy

- OT is concerned about productivity

- Concerned about payor approval

- Want continued referrals

Many clinicians lack time due to productivity. There is pressure to be extremely busy. Clinics are also developing what they are calling standard protocols. For example, if you come in with a specific diagnosis, you are directed to provide a particular treatment for a specific number of sessions. While there are rationales for why standard protocols are developed, they affect our ability to be client-centered.

Often, we are also concerned about payor approval. If the insurance company does not approve your treatment, you will not be allowed to do it. Thus, therapists have become much more concerned about getting that approval for a certain number of visits than listening to that patient.

Additionally, most therapists want continued referrals.

There are pressures from many sources coming at us in a hectic work environment. This is what the rest of this talk is going to discuss.

Who are the Pediatric Clients?

- Patient

- Parent/caregiver

- Referral source

- Physician

- Teacher

- Other therapists

- Payor Source

In pediatrics, there are multiple clients. The first is the patient, who could be an infant up to an 18-year-old. The caregiver is also our client, whether the parent comes to the session or not. Referral sources are also clients. In an orthopedic setting, most of our referrals come from a physician, a PA, or a nurse practitioner. In the school setting, it may be a teacher. Additionally, other therapists may make a referral, like an SLP referring to OT. An unwritten client is the payor source, as we need to meet their needs to continue to receive reimbursement for our services.

Client: Client/Child

- Child: Age assists in determining their ability to participate in treatment decisions and goal setting

- Can they participate actively in the interview part of the assessment?

When able, the child participates in treatment decisions and goal setting. Again, you will work directly with the caregiver if it is a younger child or a child with cognitive difficulties.

Client: Parent/Caregiver

- Parent: They are integral to the implementation of treatment and goal establishment. They speak for the younger infant/toddler.

- Are their goals realistic?

- What is driving their goals?

Our next client is the caregiver. It could be a parent or a legal guardian with them daily. These individuals are integral to our implementation of treatment and goal establishment. Many parents/guardians have goals, but we need to assess if they are realistic, especially for the child's age. What is driving their goals? Are they comparing this child to their older children or to somebody else's child?

Client: Referral/Payor Source

- Referral Source: They have observed limitations

- May have specific goals themselves

- May have pressure to limit access to therapy

- Payor Source

- Insurance company

- State agency

Our third client is the referral source, who may have specific goals. The physician may want them to crawl and bear weight on their arms, or a teacher may want them to hold a pencil and write their name.

The fourth client is the payor source, like an insurance company reimbursing you for the services or a state agency such as Medicaid or some other state funding.

Why Does the Client Matter?

- You want them invested in the outcome.

- You want them invested in the process.

- You want them to continue referrals.

- You want to be reimbursed.

Clients old enough to verbalize their desires and goals are invested in the therapy process and outcome. Whether it is the child or caregiver, you want to ensure that they understand the goals and why they are working on those. You also want your referral sources to continue sending patients. If you do not have referrals, you do not have patients, or if you do not have productivity, eventually, you do not have a job. You also want to be reimbursed, so it is something that we have to consider.

Goals

Goal Establishment

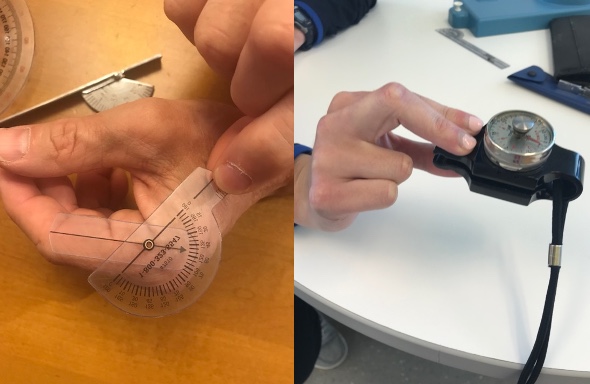

- OT completes an evaluation

- Determines limitations

How do we establish our goals? In a busy clinic, typically, the patient comes in, we complete an interview and evaluation to determine the individual's limitations, whether it is motion or strength. As pictured in Figure 1, we can measure joints and test strength.

Figure 1. Hand assessment for ROM and strength.

We can also complete a developmental evaluation to see if a grasp development limits them.

- The limitations

- Why the referral was provided

- To ensure payment (in accordance with the payor source)

You establish your goals based on the limitations you have observed, why the referral was provided, and ensure payment by the payor source. They may have requirements for their goals and how they are written.

Typical Goal Setting

- Inform all parties of the established goals.

- Scoping review in Journal of Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics:

- Sparse evidence that the child is included in establishment of goals, especially when younger than 5 or with communication or cognitive limitations.

- Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics Vol. 42, Iss. 3, (2022): 275-296

This is a typical way we set goals. Once we set them, we inform all the parties of the established objectives, including sending the evaluation to the physician and payor source. We tell the caregiver this is what we will treat.

There was a scoping review in the journal of Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics that showed there was sparse evidence that the child is included in establishing their goals, especially when the child is younger than five or has communication or cognitive limitations. They are not included in goal establishment, which is a problem. We need to do better.

Why Include the Child?

- According to Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, therapists are duty-bound to include children in decisions that impact them.

Why should we include the child? According to Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, therapists are duty-bound to include children and decisions that impact them. As an experienced OT, I strongly agree and feel we should include children in our decisions about treatment and goals.

- If the outcome is not important to the child, it affects:

- Participation

- Follow through at home

If the outcome of what we want to happen is not important to the child, it affects their participation and follow-through at home. We need to ensure that they are included in establishing their treatment and goals so that the child feels successful in what they are doing.

How to Make Treatment More Client Centered

Roles

- It is your role to assist in making treatment and goals client-centered to all involved.

Child; Parent; Referral Source; Payor; Coach; Teacher

It is your role as an occupational therapist to assist in making treatment and goals client-centered for everybody involved, including the child, parent or caregiver, referral source, and payor. It may also include the coach in their sport, the teacher who sees them daily, and anybody else involved with the child.

Referral Source

- Referral Source: Determine specifically why they are referring the child and what outcomes they are hoping for

- You should do this prior to seeing the patient

- Referral/Prescription

- Phone call

We need to determine specifically why they referred the child and what outcomes they want. You should have this part completed before that patient walks in the door. If you are lucky, you have a prescription from your physician. Some of the prescriptions only say "OT." We love this because we get to do what we want, but it does not clarify why they are referring them.

You can call the physician to ask more questions if it is not on the referral. The other thing you can do is wait until that patient and child walk into the clinic and ask them. Make sure you have determined as much as possible what the referral source's goals are before seeing the patient.

Child/Parent

- Initial Visit:

- Interview child and ask questions

- Why are they here?

- What can and can't they do?

- What do they want to be able to do?

- Interview child and ask questions

How do we make it client-centered for the child and parent? This is why we complete an initial interview. I always ask the child first, "Why are you here?" Depending on their age, they may not know or say something like, "I broke my arm, and they told me I have to come here."

My next question is, "What can you do and not do?" The child may say, "They will not let me ride my bike right now," or "They will not let me play sports." If it is an older child, they know what they cannot do. Interestingly, when you ask them what they can do, they usually say they can do everything until you have them show you. So, if there is something in doubt, ask them to demonstrate it.

You ask them these questions to find out the child's goal. It may be broad or specific. Some may not be sure why they are there if it is a traumatic injury. In these cases, ask the caregivers what they want their child to be able to do or what their child is not doing well. They will usually have information from schools, coaches, and everybody else involved with their child.

- Interview the Parent/Guardian:

- Why did they bring their child in?

- What is the child limited in?

- What do they want them to be able to accomplish?

As I was saying, I ask the parent or guardian their reason for bringing their child to therapy, especially for younger or nonverbal clients. They often say, "I want them to do their normal things again." They may report that the teacher is complaining about their handwriting or other issues. Caregivers can give you an insight into other areas of the child's life.

Payor

- Know appropriate treatment parameters

- Prior approval as necessary

Regarding being client-centered for the payor, you need to know the appropriate treatment parameters based on diagnoses and what that insurance provider requires. Prior approval may be necessary for treatment. Often with the payor source, you can do the evaluation and then submit for treatment visits. Some insurance companies may approve three visits for a traumatic injury, and they want to hear back from you every three visits on how that child is doing regarding progress and goals.

Payors can have stringent parameters, so it is essential to be aware of those. Otherwise, you may get denials, the last thing you want to happen. Some of the larger medical centers have a billing department. If the payor does not cover your services, the parents may get a large bill, which is not what you want.

Outcome Measures

Pre-Treatment Outcome Measure

- Most are diagnosis-specific or very broad

- COPM

- PODSI

- DASH

- CHEQ

We can also use pre-treatment outcome measures to help determine if goals are being met. The COPM, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, is excellent for establishing client-centered goals for older children, but it will not work for children under seven. It may also be challenging for some children and parents to understand the questions. You can get a clearer picture if you go over it with them. It is also time-consuming.

The PODSI is a generic broad-based pediatric outcome tool. Many orthopedic research studies use components of the PODSI or use it as a generic outcome tool. It focuses on function, pain, and psychosocial aspects.

The DASH is used in many upper extremity clinics. You see a lot of therapists using the DASH. It is not designed for pediatrics, as many questions are designed for adults. Sometimes they will remove the adult questions.

The CHEQ is a function-based outcome tool that is not used much in the United States. It was designed in the Netherlands.

These are all questionnaires you can hand to the patient or parent depending on their age, and you can find some information.

Evaluation Components

- Specific evaluation components also count

- Functional related goals

You can also use specific evaluation components as outcome tools. For instance, if you have noticed that they cannot supinate beyond neutral and cannot hold an object, say a ball, you can take a ROM measurement to use as an outcome goal. With all the outcome information, it may seem like we need broad function-based goals, but you can also have components for outcomes. However, all of your goals need to have a functional component. If you have a range of motion measurement as part of your goal, it must relate to function, like allowing them to turn their palm fully up to hold whatever object you want them to hold.

OT Treatment/Goals

Establishment of Treatment Plan/Goals

- OT synthesizes all of the information

- Referral

- Intake interview

- Payor guidelines

- Evaluation measures

- Determines treatment goals

The OT synthesizes all of the information from the referral, intake interview, payor guidelines, and evaluation measures to determine treatment goals because we are the professionals and experts. Then, you review those goals with the patient and the parent and revise them as needed. The parents may say, "That is not important to me. I do not care if they can open a package of chips, and it is not a limitation I want to address." You need to be willing and ready to revise your goals based on the caregiver. Or, if you have established your goals and the child says, "All I want to do is ride my bike."

Review with Client/Caregiver

- Review with patient and parent

- Revise as needed

- Explain clearly how you determined goals

- Define discharge plan

- Submit to payor and referral source

You need to revise your goals so that their desires are addressed. Once you adjust your goals, you explain clearly to the child and family how you determined your goals.

Frequently, I have patients come in through my physician looking for a second opinion, and they switched their treatment to me. They say, "I do not know why the therapist made me (or my child) work with those bubbles (or whatever activity). It didn't mean anything to me." I have frequently heard these comments, so I know that we need to do a better job of explaining our goals.

And when you are establishing your goals, you need to define your discharge plan. "This will happen when you are ready to be discharged." After we are done with all of that, we submit it to our payor and referral source. I would guess that most people, including me at times, have not taken that extra step of revising based on the family's input.

Why Should OT Establish the Goals?

- They have the knowledge base

- They have the understanding of social norms

- They can look at the whole person in relation to completion of tasks

- Connection to all involved parties

Again, why should OT establish the goals? We have the knowledge, so we need to use that. We also have an understanding of social norms. We can also look at the whole person in relation to completing one simple task, which is one of our good strengths, and we need to use it. We also are the one person that has connections to all these involved parties.

- Development: Know what an infant/child should be performing for their age

- Knowledge of the progression for development of activities; mobility, grasp, functional activities/ADLs; handwriting

What do we know that allows us to establish goals for these families and help them understand why. First, we know development very well and know what an infant and child should be performing for their age. We also know what the next steps of development are. They can do this type of grasp but will progress to this by 12 months. Through our knowledge of fine and gross motor and functional development, such as activities of daily living and handwriting, we can explain why a parent's goal may not be realistic. We can establish an in-between goal to bridge the gap. I cannot tell you how many parents of six months old want their child to use a pincer grasp, and they do not understand why they cannot. I show them what an immature pincer grasp looks like, and we will work toward that before developing the refined one.

- Anatomy/Kinesiology

- Understand how the body should work and move for function

- Tissue Healing:

- Understand the progression of tissue healing and when activity can be performed

We also know anatomy, kinesiology, and how the body needs to move for function. We also understand the progression of tissue healing; therefore, we can help instruct that patient on what activities can be performed at what stage of healing and which ones they need to avoid.

- Activity Analysis:

- Understand the components of movement and strength required to complete a task

- Can break down a task into components to work toward the larger task completion

I would guess every OT listening took at least one full semester of activity analysis. We know how to break down activities to understand the components of movement and strength required to complete a task. We can also break down a task into components to work toward a larger task. We may need to explain this to a parent. "I'm having them string beads now because I want them to be able to pinch to snap their jeans later. First, I need to work on the motion of the index fingertip to thumb to hold the small beads, but my goal is to be able to do it with force to snap their jeans." We can explain this to the child and caregiver so that they see how we are progressing toward goals.

- Adaptations:

- We know how to adapt an activity to allow successful performance

The last area of knowledge is how to adapt activities to allow for successful performance. For either a permanent or a temporary limitation, we can adapt an activity for the children to succeed. Figure 2 is a picture of a bottle I adapted for a small infant with arthrogryposis. Their elbows were stiff, and they could not bend them to get their hands to their mouth.

Figure 2. Adapted bottle.

Although we were working on gaining elbow motion, it was slow, which is common with that population. I used a dowel and a bracket holder from a hardware store so the child with extended elbows could hold their bottle. Figure 3 shows an adapted hockey mitt of a child with an orthopedic injury to their thumb.

Figure 3. Adapted hockey mitt.

The surgeons I work with are adamant that kids can go back to play, and I need to help figure out how to provide support. I always have them bring their gloves in, and we work on adapting them to protect the injured or surgical site.

How to Make Both the Eval and Treatment Client-Centered

- Listen

- Engage

- Be open-minded

- Have Cultural Sensitivity

- Inform

Listen To:

- Their story

- Their fears

- Parents concerns

- Referral source desires

- Ask good questions

We must listen to the child's and the caregiver's stories and concerns. We also need to know what the referral source's desires are. To do so, we have to ask good questions. I see many children with congenital differences. Parents may bring in their six-month-old missing with a below elbow amputee and ask, "How will they be able to hold a bat to play baseball?" Or, if it is their left hand, they will ask, "How can they put a wedding ring on?" They may be a musical family and wonder if their child will ever play piano. These are the thoughts that the parents of infants have. They are looking far ahead, but my job is to bring them back. "Here's what they need to be doing now." Or, "This is what we can work on that is appropriate for a six-month-old?"

I also want to hear the children's fears and their stories. They may have stories about how they got hurt. They may be fearful of getting hurt again or people making fun of them. You need to be a great listener.

Engage:

- Give them options

- Educate patient/parent

- Tell stories

- Personal

- Other patient's experiences

- Provide resources

You want to engage your clients by making treatments client-centered and giving them options. I tell personal and other patients' stories and experiences to engage the client and caregivers. You do not reveal who the story is about, but you say, "I had another six-year-old who had this same type of break, and here's what they ended up doing."

I see a lot of children with brachial plexus injuries. One of my favorite stories is about a professional football player named Adrian Clayborne. I believe he is retired now, but he played Big Ten football on a full scholarship for the University of Iowa. He played professional football for about a decade and was a brachial plexus injury survivor. He had limited motion in one extremity, but you never knew it. I would give an article to young boys with similar issues who were asking about their injuries or had concerned parents. Their eyes would light up. You can share these stories to help engage and see the possibilities for their recovery and lives. It also makes them invested in the process. We can provide resources on the diagnosis, support groups, camps, et cetera. We can also hook them up with support systems.

Be Open-Minded:

- Don't assume

- Don't assign goals and treatments based on what will be approved by others

- Don't assume you know best

- Collaborate

We need to be open-minded. We would all like to think that we are open-minded, but when we are busy, things may not be as optimal as we would like. You should never assume that you know what is best for that patient or what they want to do. You also do not want only to make treatment goals based on what you know insurance will approve. Instead, we need to listen to these families and find ways to convince the payor sources that those are important goals. We collaborate with these families to ensure their children have the best outcomes.

Cultural Sensitivity:

- What is important for some is not for others

- Be open to changing your priorities

We also need cultural sensitivity because what is essential for some cultures is not for others. I had a child from a different culture who had a brain stem stroke at eight. He had left the hospital after many months but still had one-sided upper extremity weakness and lack of motion. During one treatment session, he revealed that his mother was feeding him. He was eight, and one arm was not affected. I asked, "Why is your mother feeding you?" He replied, "It's just easier." His father reported that his mother was feeding him as it was very important to her. "This is what parents do for children in our culture." I did not bring feeding back up, and we worked on other tasks knowing eventually, it would carry over into self-feeding. You are not trying to change the parents' input or opinion, but you are trying to educate them so they understand the development and sequence of tasks. For instance, they need to bear weight on extended elbows before they crawl. And before they can bear weight on extended elbows, they must be prone and hold their head upright.

Inform:

- Use your knowledge to educate patient/parent

- Collaborate with parent(s) on what you know is important and what they are looking for

- Assist in realistic goals

- Break down barriers

You need to use your knowledge to explain incremental goals to achieve realistic end goals. If a parent wants them to do something that is not age-appropriate, this is where your information on development is crucial. Often patients and their parents come to you with their walls up. They have been told that they are not doing something right, like holding their pencil correctly, when they think they are doing fine. You need to use your information to help break down that barrier and engage them more.

Determining Outcomes

- Are established goals met?

- Has the child returned to or accomplished the activity?

- Is the referral source satisfied?

- Is the payor source satisfied?

When determining the outcomes of our treatment, we need to determine if the goals were met. You do not always meet all your goals, which is the reality of treatment. We need to see if the child returned to or accomplished the activity that they said was important. For instance, if they broke their arm while riding their bike, have they resumed doing it? Is the referral source satisfied, and have they reimbursed you for the treatment?

- Patient satisfaction versus outcomes

- Utilize outcome tools as appropriate

- Refer to the discharge plan

Many facilities have patient satisfaction surveys because some payor sources, such as the US government, pay based on patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction is only one small component of your outcome. We need to go above and beyond patient satisfaction. You can use your outcome tools and refer to your discharge plan.

Discharge From Treatment

- Once goals are achieved

- Continued work at home/school

- May need a follow-up plan

It is crucial to bring your discharge plan to the first treatment session after the evaluation. You show them the overview, and then at discharge, you can say, "We established and met these goals. You are now ready to be discharged." A discharge does not mean they are done with therapy. They may not need to see a professional anymore but may need to continue to work on this motion at home or school. For example, their elbow may be stiff in the morning, but by the end of the day, it is much better. They can continue to work on that end range of motion at home.

You can develop a follow-up plan where they come back and see you in so many months so that you can remeasure them and check if everything is good. Or, you can tell the caregiver, "If everything's good in three months and you notice their motion is full, you do not need to come back and see me."

There may be a need for episodic care if you are working with developing children. Instead of continual ongoing therapy for an issue that will be a lifetime issue, episodic care focuses on their current issues. "Bring them back in six months, and we will address any new issues." Many of my clients with congenital issues do episodic care. You want to get them age-appropriate with all of their daily activities. In younger years, you may focus on them doing their hair and getting dressed. They may come back a few years later wanting to work on participation in a particular sport.

In conclusion, OT is the guide for upper extremity treatment or any treatment we provide pediatric patients. Treatment must occur outside the clinic setting because therapy once or twice a week will not make a difference. We are guiding them in treatments that they have to do daily. The other part of discharge is that reimbursement constraints are a reality. If they are only going to pay for 12 visits for a compound forearm fracture, then you had better use those 12 visits wisely. Those 12 visits are all they will have for the entire year. You need to think ahead to plan for if their arm bothers them later. We may choose to use four visits right now and have them come back in a month.

Case Examples

Next, I have a couple of cases to demonstrate how to make care client-centered and establish goals and treatment. These are merely examples to help guide your thinking. Occupational therapists are busy; some clinics have even taken away administration/documentation time. This means therapists write up evaluations during lunch or stay late to do them. When overworked, it is hard to consider the client's input. I hope some of these cases help you with your clinical reasoning to make things easier.

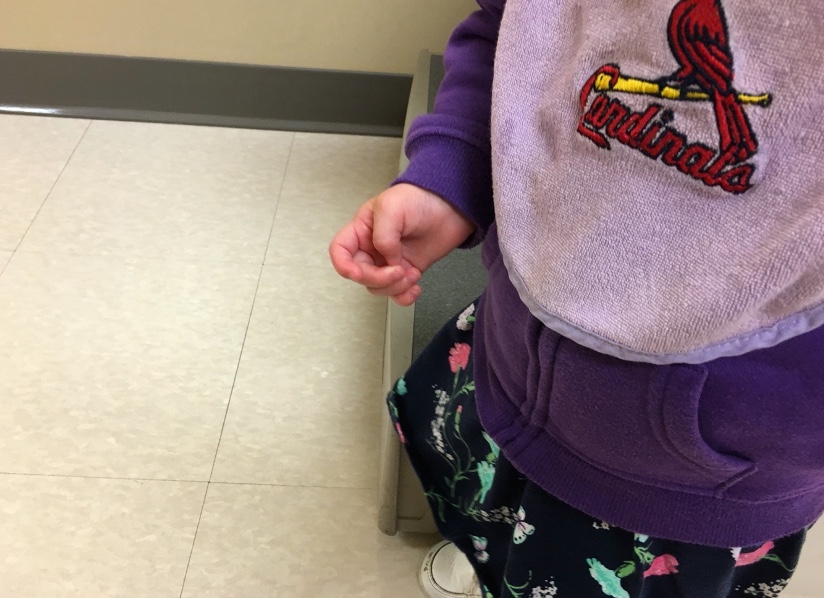

Case Example 1: Clasped Thumb

- 18-month-old infant with clasped thumb

- Referred from pediatrician

- Evaluation:

- Interview parent/guardian

- Assessment grasp and thumb motion of infant

My first case example can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. A child with a clasped thumb.

This is an 18-month-old infant, almost a toddler, with a clasped thumb. A clasped thumb cannot extend or abduct, so it rests in the palm. It can be weak, overstretched, or have absent thumb extensors or abductors. Parents do not always see it in their young infants. Or if they do, the pediatrician may say, "It'll get better. Do not worry about it." Sometimes I see one or two-month-old infants when their parent pushes for a referral. However, many pediatricians say, "Let's wait and see because there is a certain percentage that will gain strength and get their thumb out on their own." Typically, it is not a full movement, just FYI.

This 18-month-old child has a clasped thumb and was referred by their pediatrician. You do your evaluation and interview the parent. The parent may say that the thumb is in the way or they are not using that hand. The parents are getting concerned because they cannot hold on to things like handrails or bottles or manipulate toys between two hands. By 18 months, they should be using bimanual manipulation, and they cannot. After hearing the parent's concern, I do a grasp assessment using various size objects to see how far out they can move their thumb. After this, I can define and describe how they use their hand to grasp objects and what limitations they have. I may note that they cannot get their thumb out of their palm and are limited in the size of objects they can grasp.

- Determine goals

- Review with parent and provide with treatment plan including discharge planning

- Educate parent on grasp development; the common outcome of clasped thumb treatment; and clasped thumb affect on further development

I then determine my goal. For this case, my goal is that they will show increased thumb abduction and extension. I can define that if I want, or I can say, "Increase thumb abduction and extension to allow grasp of a bottle or sippy cup." I am going to start with an object that is age appropriate for that child. I can also say to grasp a toy handle. I can use whatever function is essential to that child and that parent, and I review the goal with the parent and provide them with a treatment plan and my discharge planning at that time.

At this point, I also go over grasp development and demonstrate different grasp patterns to help the parent to understand what the child should be doing. My first treatment session might be educating the parent and having the child demonstrate. I also describe the common outcome of clasped thumb treatment, including splinting and stretching, to allow the child to gain enough thumb abduction and extension to grasp all the objects they need. I also described to them the effect of clasped thumbs on further development as it can affect their long-term function.

- Provide treatment

- Determine ongoing home treatment and goals being met

- Follow up

For treatment, I may put them in a splint to hold the thumb into the more functional grasp position and provide a wearing schedule (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A splint on a child to prevent thumb in the palm.

For example, I may want them to use this splint when using their hands and/or wear it at night to keep their thumb fully out so the extensor tendon has time to shorten. If their thumb is always in their palm, the extensor tendons get overstretched. I also define my ongoing home treatment, goals, and when I will consider them being met.

The parent will need to provide home treatment such as donning and doffing the splint per the schedule, having the child grasp various objects of different sizes to bring the thumb out, and stretching the thumb out into full abduction/extension.

I also set a timeline that if we do not notice an improvement by six months, then the child has to go back to the pediatrician to see about further referrals. The child may need a surgeon as a clasped thumb is functionally limiting the older a child gets. They may be unable to hold a baseball or play a musical instrument.

Case Example 2: Both Bone Forearm Fracture

- 8-year-old with both bone forearm fracture

- Referred from orthopedics: includes x-ray and precautions/restrictions

My next case example is an eight-year-old boy with a both bone forearm fracture who was referred from orthopedics. This referral came from orthopedics, including an x-ray, precautions, and restrictions. I was in the ortho clinic with the referring physician, so I knew he was concerned about this child's forearm rotation and grip strength. The child came to me after his cast was removed.

- Evaluation:

- Interview child (child provides answers)

- Include parent in interview

- Measurements:

- Motion

- Edema

- Strength

- Provide education on restrictions: specific

I did my normal evaluation, interviewing the child and asking him what he wanted to do. He wanted to get back to playing baseball and riding his bicycle. I included his parent in the interview because they were more concerned with his ability to pronate and work on their keyboard for their homework. This was a valid goal as well.

- Establish goals

- Educated patient and parent on goals and treatment plan

- Provide education on tissue healing

- Movements affected

- Function affected

- Potential outcomes

- Discharge plan

Again, I want my goals to incorporate the child's, parent's, and my goals. My goals come from my motion, edema, and strength measurements for this child.

I am using my knowledge to provide education on restrictions. And when I instruct an eight-year-old, I am extremely specific. For instance, if I say no weight bearing, they do not know what that means. Instead, I say, "You cannot get on the floor and push yourself up." "You cannot get in the swimming pool and push yourself up using this arm." Or "You cannot do any leaning on your arm." I get very specific so that they understand because when they hear the physician has said, "No weight bearing for four weeks," they think it means no handstands or pushups. However, there are a lot of other functional activities that involve weight bearing. No weight bearing means no floor play or all the things an eight-year-old might do. Thus, I establish the goals based on motion and strength limitation, what the child wants to do, and what the parent wants them to be able to do. I educate the patient and parent on their goals and treatment plan and what we will do in treatment.

- Involve in treatment

- Utilize activities that are age appropriate and

- Patient has helped select

- Provide parent-specific activities for home

I want to ensure that my treatment is age appropriate and that the child is included in decisions. "These are the activities we need to complete today. Which one do you want to do first?" In this way, the client gets to participate in his treatment selection. I have already chosen my treatment activities based on what he has told me he likes to do. Every once in a while, we have to add things they do not like to do, like stretching or massaging the scar. I provide education to the families on tissue healing and the movements that are affected by a both bone forearm fracture. "If you cannot supinate, you cannot get your hand flat on the table or do toilet hygiene." I like to get very specific about what will be affected if they do not get full motion back. Figure 6 shows some activities selected for treatment.

Figure 6. The client used a laptop and held a baseball bat.

I also provide parents with specific activities for home. We talk about the child's daily schedule and find out what time of day is perfect for their exercises. The best time may be when they get home from school or before bed. I help them define the exercise time because it makes it easier for the parents and client to comply.

- Once goals are met:

- Provide ongoing home activities

- Provide referral source with information

- Discharge

Once the goals are met, I provide ongoing home activities. I also provide referral sources with progress on their motion and strength. Once goals are met, I can discharge him back to riding his bicycle without restrictions.

Other Case Examples

- Unilateral congenital UE amputee: Below elbow

- Monkey bars

- Cheer

- Lift weights

- Ride bicycle

Here are a couple of other case examples. Figure 7 shows an adaptation for a bike handle.

Figure 7. Bike handle adaptation for a congenital arm amputation.

Questions and Answers

How do you balance being culturally sensitive when behaviors, like the example you gave of the mother feeding an eight-year-old, affect the child's recovery?

I work in an acute pediatric setting where we often do not have very long at all to work with a child. Sometimes, we only have one week to make progress and get as much functional return as possible. Parents often help their children out of guilt or just a natural reaction, which is entirely understandable. However, this can directly and negatively affect the child's progress. It is a good question because you are right. We all have time constraints. We need to show some progress, but hopefully, we can have a goal that involves using that hand that does not impact that area in question. For example, if the parent is doing all self-care, which I have seen, that is hard to show progress. We need to educate the caregiver. We can tell them stories, give them pictures, or say, "Picture him one year from now. Do you still want to do these activities for your child, or do you want them to do them independently?" They usually say that they want their child back to normal. "Well, here's how we can get him back to doing his activities. It's imperative that he start doing some of these things for himself. Why don't you pick one, and I'll help you work with him on getting him independent with that." If you can help them look forward and share other clients' stories, that is usually helpful.

References

Curtis, D. J., Weber, L., Smidt, K. B., & Nørgaard, B. (2022). Do we listen to children's voices in physical and occupational therapy? A scoping review. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics, 42(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2021.2009616

Dorich, J. M., & Cornwall, R. (2020). A psychometric comparison of patient-reported outcome measures used in pediatric hand therapy. Journal of hand therapy: Official journal of the American Society of Hand Therapists, 33(4), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2019.05.001

Heath, K., Timbrell, V., Calvert, P., & Stiller, K. (2011). Outcome measurement tools currently used to assess pediatric burn patients: an occupational therapy and physiotherapy perspective. Journal of burn care & research: Official publication of the American Burn Association, 32(6), 600–607. https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e31822dc450

Kessler, D., Walker, I., Sauvé-Schenk, K., & Egan, M. (2019). Goal setting dynamics that facilitate or impede a client-centered approach. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, 26(5), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2018.1465119

King G. (2017). The role of the therapist in therapeutic change: How knowledge from mental health can inform pediatric rehabilitation. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics, 37(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2016.1185508

Maitra, K. K., & Erway, F. (2006). Perception of client-centered practice in occupational therapists and their clients. The American journal of occupational therapy: Official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 60(3), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.60.3.298

Majnemer, A., & Limperopoulos, C. (2002). Importance of outcome determination in pediatric rehabilitation. Developmental medicine and child neurology, 44(11), 773–777. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0012162201002912

O'Connor, D., Lynch, H., & Boyle, B. (2021). A qualitative study of child participation in decision-making: Exploring rights-based approaches in pediatric occupational therapy. PloS one, 16(12), e0260975. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260975

Phoenix, M., & Vanderkaay, S. (2015). Client-centred occupational therapy with children: A critical perspective. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, 22(4), 318–321. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1011690

Riley, B., Hardesty, L., Butler, A., Kimmelman, A., Gardner, K., & Miceli, A. (2017). How do pediatric occupational therapists implement family-centered care? Am J Occup Ther, 71(4_Supplement_1), 7111505155p1. doi:

Tanner, L. R., Grinde, K., & McCormick, C. (2021). The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: a Feasible Multidisciplinary Outcome Measure for Pediatric Telerehabilitation. International journal of telerehabilitation, 13(1), e6372. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2021.6372

Citation

Calhoun, V. (2022). Client-centered occupational therapy pediatric upper extremity treatment to obtain outcomes. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5546. Available at https://OccupationalTherapy.com