Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Cognitive Interventions In The Home: A Practical Approach For OT Professionals, presented by Krista Covell-Pierson, OTR/L, BCB-PMD.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify four ways an OT can integrate cognition into a treatment plan.

- List four assessments for cognition that are appropriate to use in the home setting.

- Recognize four types of memory impairments and distinguish between dementia and delirium.

Introduction

Today, we will delve into cognitive interventions in the home—a practical approach tailored for occupational therapy professionals. Our profession holds significant potential to profoundly impact individuals' lives, although, at times, it may seem challenging to grasp the full scope of our role. However, during our discussion, I aim to provide you with valuable insights that you can readily integrate into your practice.

I reside in Colorado and am the proprietor of Covell Care and Rehab, a private practice where we serve a diverse patient population. The majority of our patients contend with various cognitive impairments, an aspect of care that I find particularly rewarding. Our work extends to individuals coping with conditions such as dementia, brain injuries, mild cognitive impairment, and other cognitive-related issues.

In my 22-year career as an occupational therapist, I have come to believe that, as OTs, we can enhance our approach to addressing cognition. As we embark on a deeper exploration during this hour, I encourage you to consider how you can better assist patients facing cognitive challenges.

You might wonder why this topic is of utmost importance. Given your roles as OT practitioners, you likely recognize its significance and inherent value. However, I intend to equip you with the language and rationale to explain its importance to our patients, their families, our colleagues, supervisors, and third-party payers. Effective communication, both verbally and in written documentation, is crucial. Therefore, we will touch on various aspects of this skill.

Why Is This Important?

When defining cognition, it's essential to appreciate the multifaceted nature of the concept. Several skills interplay when we consider cognition. One definition I find particularly insightful is derived from the Dementias Platform in the United Kingdom, and it reads as follows: "Cognition is a term for the mental processes that take place in the brain, such as thinking, attention, language, learning, memory, and perception." The areas are listed below.

- Defining Cognition:

- Thinking

- Attention

- Language

- Learning

- Memory

- Perception

- Skill generalization and combination

- Functional cognition

We also know as OTs that these processes are not discrete abilities, like this gentleman in his raft (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Man in a raft in the water.

Cognitive processes are intricately interconnected, akin to floating on a raft. Our objective is to equip our patients with diverse skills that harmoniously converge, enabling them to become proficient, functioning individuals, regardless of age. Therefore, when we clarify our purpose, we must emphasize that we are not solely focused on enhancing learning or memory.

Instead, our aim is for these improvements to translate into a higher quality of life. Effective communication plays a pivotal role here. While we often discuss these individual facets, it is equally essential to view the bigger picture and recognize the invaluable role that occupational therapists bring to the table.

Patients may have previously undergone neuropsychological evaluations, cognitive screenings with physicians, or worked with speech-language pathologists. Nevertheless, we can step in and comprehensively assess the array of skills listed here, aligning them with our patients' life goals. Thus, our presence within the cognitive team is highly practical.

The research underscores that when patients receive occupational therapy tailored to address functional cognition, it significantly reduces their risk of hospitalization or re-hospitalization. This outcome is compelling and resonates with various stakeholders, including third-party payers, administrators, supervisors, and, most importantly, our patients and their families. Keeping our loved ones out of the hospital is a shared priority for all.

Cognition Impacts ADLs

- Dressing

- Showering

- Cooking

- Laundry

- Childcare

- Grooming

- Home management

- Financial management

- Community involvement

- On and on!

Moving beyond discussing cognition, let's look at how cognition profoundly influences our daily activities, our routines, and, ultimately, our quality of life. While it's not groundbreaking for us to acknowledge that cognitive skills impact daily living, what sets us apart is our ability to effectively communicate how we can enhance these activities.

The tasks I've outlined here serve as simple examples that can be seamlessly integrated into our therapeutic goals to demonstrate tangible improvements in function through enhanced cognition.

Is it truly impactful if someone can recall five random words when prompted? Not really, because it lacks functionality. What genuinely matters is if someone can remember five essential steps in operating their washing machine, enabling them to independently and efficiently do their laundry. The real victory lies in achieving practical, meaningful outcomes where individuals no longer require constant caregiver assistance.

Our approach involves identifying these personally significant tasks, aligning them with the cognitive processes that require improvement, and then guiding our patients through the journey of mastering these tasks. This approach benefits our patients and facilitates clearer communication in our notes and collaboration with our peers, which we will delve into further.

ADLs at Home

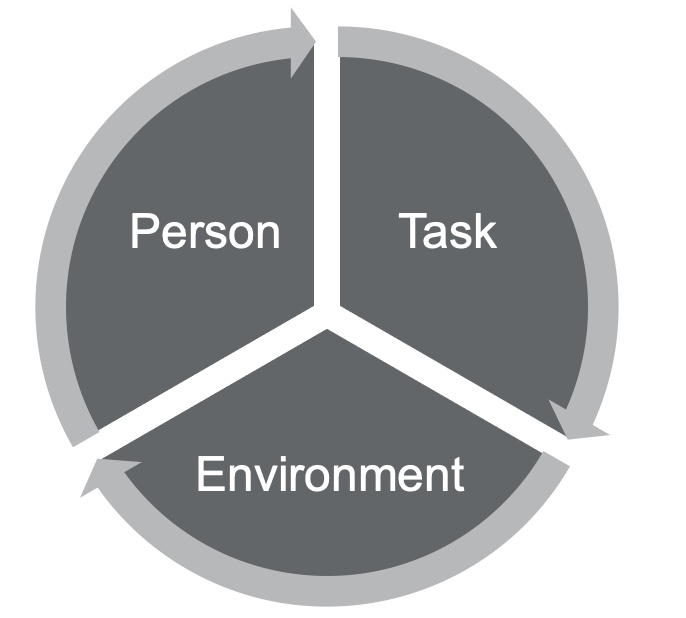

Figure 2 shows an infographic showing how the person, task, and environment are interconnected.

Figure 2. Person-task-environment diagram.

I frequently use diagrams like the one shown here because they align with the person-environment model, which emphasizes a holistic approach to assessing occupational performance. When working with our patients, conducting a comprehensive assessment is crucial. This assessment should encompass an examination of their skills, deficits, desires, mental and physical health, and medical needs. The goal is to develop a personal profile, recognizing that all these facets significantly impact an individual's functional cognition.

Next, we focus on identifying meaningful tasks, a process in which both the patient and their family members or caregivers play a vital role. Prioritizing tasks that resonate with the patient's motivations is imperative because intrinsic motivation is pivotal, especially when dealing with cognitive challenges. If a task isn't personally meaningful, it can be challenging to rationalize its importance, particularly for those already facing cognitive difficulties.

Additionally, it's crucial to assess how the patient perceives their skillset and compare it with our observations. Often, individuals with cognitive difficulties may overestimate their abilities. Input from loved ones and caregivers is equally valuable, as their perceptions might differ from our assessments.

A particularly rewarding aspect of our work is when we can engage with patients in their homes. This intimate setting allows us to witness their daily lives, which can be both dynamic and enlightening. Unlike a static therapy gym, homes vary, offering a unique and enjoyable challenge.

Here are two real-life examples that illustrate the diversity of environments we encounter. I had a patient who was living in a mother-in-law-type apartment above the garage. She had a huge family with members coming in and out all the time. It was distracting even for me during treatment, so I knew it was distracting for her, especially living with memory loss and cognitive fatigue related to chemotherapy treatments. I also had a patient who lived two minutes away in low-income housing. She had very limited resources and no social support system in town. Her family lived out of state, and she had no friends. She was dealing with crippling anxiety, memory loss, and decreased problem-solving skills related to years of alcohol and drug abuse. These are different people in two different environments. I can start by going into the home and looking for ideas and answers based on those environments. I can see what's meaningful to them. For example, I might see that they have a smartphone or notes next to the phone. I might see that they have their own cookbooks and like to cook. I can start using those things to make the tasks more meaningful when I'm in the environment. Working in the home setting requires flexibility and adaptability, but it's where the magic truly happens. Utilizing personal items like photographs, meaningful objects, or even the layout of their home can enhance memory recall and yield better results. Whether you're considering working in a home setting or already doing so, it's a personally rewarding endeavor. You'll find ample opportunities to connect with patients and significantly impact their lives.

Lastly, the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) advocates for our role in the cognitive space. They define us as experts in measuring functional cognition, encompassing everyday task performance. Recognizing subtle cognitive impairments is crucial, as they often go untreated but can significantly impact an individual's functioning. As OTs, we treat cognitive impairments because they have the potential to compromise the safety and long-term well-being of our patients. By familiarizing yourself with AOTA's resources and language, you can strengthen your documentation and advocacy efforts, ensuring that OTs continue to play a vital role in addressing cognition and improving the lives of our patients. For additional information, refer to AOTA's resources on cognitive intervention.

Integrating Cognition Into a Treatment Plan

- Starts with chart review

- Education to patients/families of brain function as it relates to ADL at home

- Identification of areas of concern at home

- Administration of cognitive assessments at home

The integration of cognition into a treatment plan is a pivotal aspect of our occupational therapy practice. It's a process that begins with a thorough chart review, a step that some therapists may sometimes overlook in the midst of their busy daily routines. However, I want to emphasize the significance of this step. Neglecting it can potentially hinder the outcomes of your treatment plan.

A strong understanding of neuroanatomy is essential when reviewing medical records, especially in cases involving cognitive challenges. While most of us studied neuroanatomy in college, refreshing your knowledge may be a good idea, especially if it's been a while. Although we won't go into an in-depth neuroanatomy lesson, I'll touch on some key points to jog your memory. This knowledge will serve as a foundation for aligning the information you gather from chart reviews with your patient assessments. It also enables you to educate your patients, their families, and caregivers about what's happening in the brain.

You don't need to become a neurologist, but having a strategic understanding of the neurological aspects can significantly benefit your approach. For example, consider a patient who exhibits inappropriate behavior, like a previous client of mine. He would go out into public and act inappropriately, especially towards some of the women working at a local coffee shop. This gentleman was quite large, standing at 6'7", and that alone could be intimidating. Some of his inappropriate behaviors required occupational therapy intervention, but I also understood that trauma in his brain might have contributed to these behaviors. It's important to approach your work with a bit of strategy and understanding about what's going on neurologically. Knowing how specific areas of the brain might be contributing to certain behaviors can be incredibly valuable. It's all about bringing this understanding back to functional cognition.

If you find yourself without access to detailed medical records or relevant neurology reports, especially when dealing with a patient diagnosed with dementia but lacking associated medical documentation, consider requesting these records or making referrals to specialists. In some areas, neurology departments may have lengthy waitlists, so it's wise to get the process started early to ensure your patients receive timely support for their cognitive challenges.

Let's briefly review the critical regions of the brain. The frontal lobe, often referred to as our "mission control," plays a central role in cognitive functioning. It influences emotional expression, problem-solving, memory, judgment, and even sexual behaviors. Understanding this region can help us connect cognitive deficits with functional challenges. The temporal lobes are responsible for visual, olfactory, and auditory processing. These processes are vital for healthy thinking, emotional responses, and communication. The occipital lobes act as our visual hub, enabling us to interpret color, shapes, and object locations. In contrast, the insular cortex facilitates sensory processing, emotional expression, and some motor functions. The parietal lobe allows us to make sense of sensory experiences in the world, ensuring we can understand our surroundings and adapt our actions accordingly. There are also subcortical structures deep within the brain, including the diencephalon, pituitary gland, limbic structures, and basal ganglia. These structures can be likened to a "switchboard" or "mission control," simplifying complex medical concepts for our patients.

When educating patients and families about brain function in relation to activities of daily living (ADLs), consider using relatable examples and analogies. For instance, you could compare the brain to an avocado. This can make complex information more accessible and engaging.

Once you've conducted a chart review and gathered relevant information, it's an excellent time to begin educating your patients and their families about brain function and its implications for daily life. This step is crucial in building a strong foundation for your treatment plan. It helps your patients and their families understand the reasoning behind your interventions, making your approach transparent and empowering.

For instance, I once worked with an aide in an assisted living facility who had been caring for residents with different diagnoses for years but was unaware of the differences between these conditions and their effects on motor planning, cognition, and progression. Educating her about these differences transformed her perspective and improved her caregiving. Incorporate this education into your treatment plans and goals, and consider including caregiver-based goals when appropriate. By fostering understanding and collaboration, you can ensure that your interventions are effective and well-received.

Identifying areas of concern in the patient's home is the next crucial step. During evaluations, patients and their families may provide a wealth of information, but it's essential to sift through this data and prioritize. Given the pervasive influence of cognitive deficits, the list of concerns can be extensive. Start by identifying safety concerns, as these should always be addressed first.

Subsequently, focus on two to three areas that are particularly important to the patient and their family. This targeted approach allows for more manageable and effective interventions. Keep in mind that cognitive improvements in one area may have a positive ripple effect on other ADLs.

Treatment Planning Within the Home Environment

- Interpretation of results/Giving results meaning

- Identification of areas to work on

- Determining Functional Cognition!

Giving meaning to assessment scores is crucial. It's not enough to provide a number; we need to translate those scores into practical implications for the individual's daily life. This helps us pinpoint areas that require intervention and tailor our treatment plans to address specific functional challenges related to cognitive deficits.

Functional Cognition

- Defined as:

- The cognitive ability to perform daily life tasks is conceptualized as incorporating metacognition, executive function, other domains of cognitive functioning, performance skills (e.g., motor skills that support action), and performance patterns.

- Making Functional Cognition a Professional Priority | The American Journal of Occupational Therapy | American Occupational Therapy Association (aota.org)

- Functional cognition should ONLY be evaluated in actual task performance. Home is ideal!

Functional cognition is a critical aspect of occupational therapy practice, and its definition has evolved over the years to provide a more comprehensive understanding of its role in daily life. The current definition emphasizes the integration of cognitive skills for performing activities of daily living (ADLs) and includes skills, strategies, and psychosocial elements. This updated definition acknowledges the impact of the environment, mental health, and physical health on an individual's cognitive abilities, making it a more robust framework for OTs to assess and address functional cognition in their clients.

Consideration for Functional Cognitive Treatment Planning

- Person focused

- Culture

- Environment

- Emotional health

- Neurological and biological factors

In the realm of functional cognitive treatment planning, our focus naturally gravitates towards a person-centered approach. This inclination is hardly surprising, given that we, as occupational therapists, excel at catering to individual needs and aspirations. However, we may not always consider the profound impact of culture in our practice.

Culture, encompassing one's upbringing and early learning experiences, profoundly influences how individuals engage with their surroundings, perceive others, absorb and retain information, and form judgments. It's essential to recognize that these cultural nuances can vary significantly, especially when working with individuals from diverse backgrounds or those whose cultures we may not be intimately familiar with. A thoughtful exploration, whether through conversations with the patient or their family or through independent research, can unearth vital insights that should not be overlooked.

Cultural awareness aside, we must also cast our gaze upon the environmental factors that bear upon an individual's performance. Consider the case of a patient dwelling in a mother-in-law apartment, where chaos perpetually reigns. Amidst the constant juggling of pet care, from dogs to kittens and birthing cats, alongside the responsibility of caring for a boyfriend with brittle diabetes, distraction becomes a relentless companion, exhausting in its own right. Here, our task is to discern the nuances of such environments and strategize on managing their impact.

Emotional well-being is another facet deserving of our attention. A poignant quote aptly reminds us that "emotional function and cognitive function aren't unrelated to each other; they're completely intertwined." This truth is self-evident to anyone who has traversed the depths of grief, battled the shadows of depression, or grappled with the relentless grip of anxiety. When we encounter a patient navigating such emotional storms, we must acknowledge that their cognitive abilities may bear the brunt of these turbulent waters. A recently bereaved patient struggling to find equilibrium may exhibit signs of forgetfulness or cognitive struggle directly linked to their emotional state.

Lastly, we must not overlook the neurological and biological dimensions. Employing tools like brain scans and neuropsychological evaluations, we gain invaluable insights into the mind's inner workings. This knowledge becomes a cornerstone for crafting precise treatment plans and, where necessary, advocating for specialized care. Consider this parallel: just as you wouldn't prescribe the same medication for every patient with chest pain, so too should we be cautious of hastily offering psychiatric drugs without a comprehensive understanding of what's transpiring within the patient's brain. As occupational therapists, recognizing the significance of these assessments, our duty extends to educating our patients and championing their access to the expertise that can provide tailored solutions for their unique cognitive challenges.

Assessments to Use at Home

- Confusion Assessment Method: to identify patients with delirium: The_Confusion_Assessment_Method.pdf (va.gov)

- The Brief Interview for Mental Health Status

- Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills

- Executive Function Performance Test

Let's now delve into the assessments that can be incorporated into our practice. Although some of these assessments may initially appear unconventional for occupational therapists, they offer valuable insights and are integral to comprehensive care.

The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and Brief Interview for Mental Health Status (BIMS) do not inherently align with traditional OT practices, but both have gained approval from Medicare for assessing cognition. CAM, for instance, aids in identifying delirium in patients. Delirium, which can range from subtle to severe, may not always be readily apparent. By conducting CAM, we ensure that cognitive assessments are appropriate, as addressing cognition when delirium is present can be counterproductive. Even if you are confident that delirium isn't a factor, utilizing CAM demonstrates a thorough approach, which can be crucial for third-party payer compliance. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has integrated CAM into post-acute care assessments, which might already be a part of your healthcare team's protocol.

On the other hand, BIMS, another CMS-approved assessment, serves as a valuable tool for neuropsychological screening. For example, if you encounter a patient grappling with profound grief and depression, the BIMS can shed light on their mental state. It's essential to address mental health concerns before diving into cognitive evaluations. Collaborating with your healthcare team to determine who administers these assessments can streamline the process. Alternatively, you can administer them yourself; they are efficient and quick, providing a solid foundation for cognitive assessments.

Let's explore assessments that align more closely with traditional occupational therapy practices. The Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills is a reliable, client-centered, performance-based assessment designed to measure occupational performance in daily life tasks. It can be effectively employed with adolescents, adults, and older adults, even in home settings. Comprising 26 core tasks, including mobility, basic ADLs, IADLs with a physical focus, and crucially, 14 IADL tasks related to cognition, the PASS provides a holistic view of a patient's abilities and how they navigate various tasks.

The Executive Function Performance Test examines a patient's capabilities in tasks like cooking, phone use, medication management, and bill payment within their home environment. It offers valuable insights into a patient's functional abilities and serves as an educational tool for families. Additionally, it's accessible as a free download, providing convenient access to a useful assessment tool.

Despite their initial differences from conventional OT practices, these assessments play an indispensable role in ensuring comprehensive care and tailored interventions for our patients.

Additional Assessments to Use at Home

- Fitness to Drive Screening Measure: Web-based to identify at-risk drivers

- Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment (LOTCA): Cognitive and visual perception skills in older adults are assessed

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): Measures orientation, recall, short-term memory, calculation, language, and constructability

- Cognitive-Performance Test (CPT): Explains and predicts capacity to function in various contexts and guide intervention plans

- Cognistat: Rapid testing for delirium, MCI, and dementia (can be used with teens to adults)

- Trail Making Tests A and B

Incorporating assessments into our home-based occupational therapy practice is essential for providing comprehensive care. One critical area that demands our attention is assessing a patient's fitness to drive. If you work in the community, be it outpatient, home care, or mobile outpatient services, addressing a patient's ability to drive is paramount, especially when cognitive issues are at play. However, determining whether a patient should drive requires specific skills and training. If you lack this expertise, it's crucial to connect with a Certified Driving Rehab Specialist (CDRS), often an occupational therapist or physical therapist with extensive training in driving assessments. Collaborating with CDRSs is vital, as it directly relates to public health, safety, and community well-being. The tragic example of a wrong-way driver causing a fatal accident highlights the significance of addressing driving concerns diligently.

Here are some assessments that you can integrate into your practice. The Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment, previously known as the LOTCA, assesses cognitive and visual perception skills. It aids in identifying various levels of cognitive difficulties and provides insights into a patient's learning potential and thinking strategies. This information significantly influences our treatment planning and intervention selection. Additionally, the LOTCA offers different versions tailored to different age groups, enhancing its versatility.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) assesses orientation, recall, short-term memory, calculation, language, and constructive ability. While it's commonly administered in physician's offices, you can also use it in your home-based practice. There's a similar tool called the SLUMS (Saint Louis University Mental Screening), which is a free assessment option.

The Cognitive-Performance Test (CPT) is a performance-based assessment that explains and predicts a patient's capacity to function in various contexts. It employs the Allen Cognitive Levels for rating patients, which can be shared with their families to help them understand cognitive challenges better.

Although typically used in inpatient psychiatric facilities, the Cognistat can be adapted for home-based assessments. It's a rapid test that differentiates between delirium, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia and can be applied across various age groups.

The Trail Making Tests A and B evaluate general cognitive function, including working memory, visual processing, visual-spatial skills, selective and divided attention, processing speed, and psychomotor coordination. Trail Making Test B, in particular, has been linked to poor driving performance. If a patient performs poorly on this test and intends to drive, it's advisable to refer them to a CDRS or consider pursuing CDRS certification.

These assessments, though diverse in their applications and availability, expand our toolkit for home-based occupational therapy. Some may require purchase, while others can be downloaded. Discuss the possibility of integrating these assessments into your practice with your employer to enhance the quality of care you provide during home visits.

Clinical Observations

- Errors in math

- Frustration from the patient

- Distractibility

- Difficulty focusing

- Repeated phrases

- Requires redirection

- Unable to locate items

- Impulsivity

- Reduced reciprocity

- Reduced problem-solving skills

- Delayed or absent recall

- Changes in perception

- Poor insight

- Changes in personality

- Irritability

- Safety concerns

- Increased fatigue

- Decreased organization

It's essential to emphasize the value of your clinical observations and activity analyses in your documentation. These observations, rooted in your skilled assessment and honed through clinical experience, provide crucial insights into a patient's cognitive abilities and challenges.

For instance, consider an activity as straightforward as making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, reminiscent of college days. While occasional difficulties in locating items or lapses in focus are common and may not necessarily indicate a cognitive issue, persistent patterns of such challenges warrant attention. If you consistently encounter these issues or receive complaints from families, it's an indication that cognitive assessment and intervention may be necessary, even if your initial focus was on a different aspect of care. Your ability to recognize these signs and adapt your approach is a testament to your clinical expertise and dedication to comprehensive patient care.

Home Strategies

- Visual cues

- Automatic timers

- Lighting alternatives

- DME for fall prevention

- Reduced clutter

- Calendars

- Alarm/alert systems

- Phones and computers

- Routine modifications

- Mental health support/activities

- Paper calendars

- Checklist

- Timers for time modulation

- Caregiver education

- Driving alternatives

- Dementia education and training

- Emergency preparedness

- “Just right challenge” tasks

- Safety training

- Stress management

Working in a patient's home setting can be an incredibly rewarding experience for occupational therapists. It provides a unique opportunity to tap into our innate creativity and adaptability as professionals. Here are some strategies and interventions that can be seamlessly integrated into home-based care:

Utilizing visual cues can be highly effective. For example, consider a patient who frequently snacks on unhealthy foods. To address this issue, you can clear a designated place on the kitchen counter, place a placemat there, and instruct caregivers to set out specific healthier snacks on the placemat. This visual cue prompts the patient to choose healthier options, promoting improved dietary habits.

While automatic timers can be useful, it's crucial that the patient understands their purpose. Many patients may become confused when timers go off without clear instructions. Therefore, ensuring the patient comprehends the intended use of timers and how to respond when they activate is essential.

In cases where certain areas lack adequate illumination, such as bathrooms, adjusting the lighting can reduce patient distress and confusion, particularly for those with cognitive impairments. Ensuring a well-lit environment can enhance their comfort and safety.

Managing a patient's energy levels throughout the day is vital. Cognitive issues, from dementia to brain injuries, can lead to increased fatigue. Therefore, helping patients modulate their activity levels and prevent excessive exhaustion is integral to care planning.

Smartphones, computers, and phones can be valuable tools for patients, provided they have a basic understanding of how to use them. Caregiver education in this regard can empower patients to leverage technology for various aspects of daily life.

Stress can significantly worsen cognitive function. Implementing stress management techniques and strategies can be beneficial for patients. This may include relaxation exercises, mindfulness practices, or simple stress-reduction activities.

Although not listed, exercise plays a crucial role in maintaining and improving cognitive function. Incorporating physical activity, even in modified forms, can engage the cerebellum and contribute to clearer thinking and improved cognitive abilities.

In summary, home-based occupational therapy allows us to be creative and tailor interventions to suit each patient's unique environment and needs. Utilizing visual cues, appropriate technology, and effective energy management can enhance our patients' quality of life and well-being while addressing cognitive challenges.

Adding Goals to Treatment Plans

- Client-based

- Occupation

- Assist level

- Specific

- Time-bound

When formulating goals for cognitive interventions, it's beneficial to employ the COAST framework, emphasizing client-centered, occupation-based, specific, and time-bound goals. These objectives should align with the principles of functional cognition and measure improvements in functional outcomes. Here are a few practical examples:

Medication Management Goal

For this goal, the focus is on the patient's ability to manage their medications effectively. In the COAST framework, the goal is tailored to a specific patient, the occupation in focus is the proper administration of daily medications, the patient will employ learned strategies to achieve this goal, the specific objective is for the patient to take all five of their daily medications using the strategies they've acquired, and the patient is expected to reach this goal within a timeframe of three consecutive days within two weeks.

Phone Management Goal

This goal centers around a patient's capability to manage medical appointments through phone calls. In the COAST framework, the goal is customized to meet the specific patient's needs, the occupation in focus is the efficient management of medical appointments via telephone, the patient is encouraged to strive for independent management using their contact list and iPhone, the specific aim is for the patient to make two phone calls with a flawless accuracy rate to manage medical appointments, and the patient is expected to reach this goal within the span of four treatment sessions.

Meal Preparation Goal

In this scenario, the goal is to enhance a patient's ability to prepare a meal, leveraging visual cues. In the COAST framework, the goal is tailored to meet the specific patient's needs, the occupation in focus is the independent preparation of a meal, visual cues will be used to assist the patient in achieving this goal, the specific aim is for the patient to prepare a simple meal while relying on visual cues placed within the kitchen, and the patient is expected to reach this goal within a specified timeframe.

In your documentation, it's crucial to be explicit about the cognitive strategies being employed. This guides the treatment approach and sets clear expectations regarding when the patient is anticipated to succeed. By adhering to the COAST framework and focusing on measurable functional improvements, your cognitive goals will effectively address each patient's unique needs and challenges.

Challenges With Documentation

- EMR useability

- Limited resources online or with employers

- Cognitive goals can require extra time to ensure quality

- Medically necessary required for billing

- Third-party payer authorizations can be more difficult to obtain

Documenting cognitive interventions can pose challenges, particularly within electronic medical records (EMRs) that may not be tailored to occupational therapists. It's not uncommon for EMRs to be more user-friendly for physical therapists, so OTs often need to get creative in how they use these systems. This might involve finding workarounds or advocating for the necessary resources and support from employers to ensure efficient documentation.

Cognitive goals and interventions may also require additional time compared to traditional physical therapy interventions. Justifying this extended timeframe in your treatment recommendations for third-party payers is crucial. Instead of merely stating that you're working on a specific task, such as transfer training, provide a clear rationale for the prolonged duration. For instance, if you're implementing errorless learning techniques or addressing specific cognitive challenges, explain why this additional time is medically necessary for the patient's benefit.

Navigating third-party payment authorizations can be more complex when dealing with cognitive disabilities. Advocacy becomes essential in such cases. You may encounter denials, but don't hesitate to appeal these decisions. Back your appeal with well-structured documentation that educates the payer about the intricacies of cognitive impairments and their impact on the patient's daily life. Emphasize the medical necessity of your interventions. This advocacy can lead to successful outcomes, as exemplified by a case where an appeal secured additional therapy sessions for a patient who ultimately achieved her academic and career goals despite cognitive challenges.

In summary, documenting cognitive interventions may require creativity within EMRs, justification for extended treatment times, and advocacy to secure the necessary authorizations. Through clear and informed documentation, you can effectively convey the medical necessity of your interventions and advocate for the best outcomes for your patients.

Billing for Cognition

- 97129:

- Therapeutic interventions that focus on cognitive function (e.g., attention, memory, reasoning, executive function, problem-solving, and/or pragmatic functioning) and compensatory strategies to manage the performance of an activity (e.g., managing time or schedules, initiating, organizing, and sequencing tasks), direct (one-on-one) patient contact.

- 97130:

- Therapeutic interventions that focus on cognitive function (e.g., attention, memory, reasoning, executive function, problem-solving and/or pragmatic functioning) and compensatory strategies to manage the performance of an activity (e.g., managing time or schedules, initiating, organizing, and sequencing tasks), direct (one-on-one) patient contact.

When it comes to billing for cognitive interventions in occupational therapy, there are specific Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes that you should use. These codes help you accurately document and bill for the services you provide. Here's a breakdown of the relevant codes:

The 97129 code is used for the initial 15 minutes of therapeutic interventions. It's important to note that this code is the same as 97130 in terms of definition. After the initial 15 minutes, you would use the 97130 code for each additional 15-minute increment of therapeutic interventions.

It's crucial to be precise in your documentation and use the language provided in the CPT code descriptions. This helps ensure that your third-party payer understands the nature of the interventions you're providing and approves the billing accordingly. For example, if your therapy session focused on executive function tasks, make sure to explicitly mention that in your documentation. By aligning your documentation with the CPT code definitions, you provide a clear and accurate account of the services you delivered.

To stay organized and informed, consider keeping a handy reference sheet of CPT codes and their definitions, even if you're experienced in your field. This can be a valuable tool for ensuring consistency and accuracy in your billing and documentation practices.

Types of Cognitive Impairments

As we wind down, I want to talk about delirium and dementia for a second.

Delirium Vs. Dementia

Delirium is a condition that, while more commonly associated with acute care settings, can also manifest in the community or during home care visits. As occupational therapists, it's essential to be knowledgeable about delirium because of its potential severity and impact on patients. You might be the primary healthcare provider present in these situations, so identifying delirium becomes crucial.

Delirium is characterized by a sudden onset and is primarily defined by disturbances in attention and awareness. Recognizing delirium is essential because it can lead to significant complications if left unaddressed. Being vigilant and informed about delirium ensures that you can provide appropriate care and support, especially when you're working in home care or outpatient settings where immediate access to medical personnel may not be readily available.

Delirium

- Disturbance in attention and awareness developing acutely tends to fluctuate in severity

- At least one additional disturbance in cognition

- Disturbances are not better explained by dementia

- Disturbances do not occur in the context of a coma

- Evidence of an underlying organic cause

Delirium is a condition characterized by its rapid onset and varying degrees of severity. It's marked by at least one noticeable disturbance in cognition, and it's important to note that this disturbance cannot be attributed to dementia. To help identify delirium quickly, you can utilize the delirium assessment we discussed earlier, which is a fast and efficient tool. If the assessment indicates delirium, seeking immediate medical attention is crucial. While it's rare to encounter someone in a coma during home visits, delirium can manifest in various ways and usually indicates an underlying cause.

Delirium can result from factors such as medication interactions, psychiatric issues, or infections. When you're in a home care setting and observe signs of delirium, it's essential to prioritize the person's safety and well-being by promptly getting them the necessary medical care.

Dementia

- Significant cognitive decline in one or more cognitive domains.

- Cognitive impairment interferes with ADL.

- Cognitive impairment does not occur exclusively in the context of delirium.

- Cognitive decline is not better explained by other medical or psychiatric conditions.

Dementia is distinguished by significant cognitive decline in one or more cognitive domains, and this decline typically interferes with a person's ability to perform daily activities. It's important to note that delirium and dementia can coexist and are not mutually exclusive conditions. While someone with dementia can experience delirium, the two are distinct.

To diagnose dementia, a physician is required as it involves a comprehensive evaluation beyond the scope of occupational therapy. It's essential to remember that dementia is not a specific disease; rather, it is an umbrella term encompassing various conditions characterized by cognitive decline. Each type of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, or Lewy body dementia, has its unique features and progression patterns. Thus, it's crucial to recognize that not all dementias are the same, and a proper diagnosis is necessary for appropriate management and care planning.

- Dementia

- Vascular dementia

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Frontotemporal dementia

- Alzheimer’s

- Mild cognitive impairment

- Encephalopathy

It's crucial to understand that dementia is a broad category encompassing various conditions, each with its unique characteristics and underlying causes. Dementia is not a single disease but rather a term used to describe a range of cognitive impairments. Here are some types of dementia and their distinguishing features:

Vascular dementia results from impaired blood flow to the brain, leading to problems with reasoning, planning, judgment, memory, and other cognitive functions. It is often characterized by cognitive deficits that can vary in severity, as if the brain's function has "holes" due to damage from inadequate blood flow.

Dementia with Lewy bodies is a progressive dementia characterized by a decline in thinking, reasoning, and independent function. Individuals with this type of dementia commonly experience sleep disturbances, visual hallucinations, and movement disorders, such as slow movements, tremors, and rigidity. It is closely related to Parkinson's disease.

Frontotemporal dementia refers to a group of disorders caused by nerve loss in the brain's frontal and temporal lobes. It can manifest as changes in behavior, empathy, judgment, foresight, and language abilities. The specific symptoms may vary depending on the regions of the brain most affected.

Alzheimer's disease is the most common type of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of dementia cases. It is characterized by progressive cognitive decline, including memory loss, language problems, and difficulties with daily activities. Plaques and tangles in the brain are hallmarks of Alzheimer's.

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) represents cognitive impairments that are more significant than expected for an individual's age and education level but do not meet the criteria for dementia. While individuals with MCI are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, not everyone with MCI progresses to dementia.

Encephalopathy refers to a broad term for brain dysfunction. It can lead to a range of cognitive difficulties, including problems with concentration, suicidal thoughts, lethargy, vision issues, swallowing difficulties, seizures, dementia-like behaviors, and more.

Understanding the specific type of dementia is essential for appropriate care and interventions, as each type may require different management strategies and approaches. Additionally, dementia is a complex condition with various underlying causes, and research continues to uncover more about its mechanisms and risk factors.

Summary

- "Neuroscience is by far the most exciting branch of science because the brain is the most fascinating object in the universe. Every human brain is different - the brain makes each human unique and defines who he or she is.”

- Stanley B. Prusiner

- “Occupational therapy practitioners help people live life to its fullest - no matter what. They provide practical solutions for success in everyday living and help people alter how they arrange their daily activities to maximize function, vitality, and productivity.”

- Florence Clark, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA

As we conclude this session, I'd like to share some valuable insights and practical tips for addressing cognition in occupational therapy. Remember, as occupational therapy practitioners, our role is to help people live life to the fullest, providing practical solutions for success in everyday living. We can assist individuals in maximizing their function, vitality, and productivity, regardless of their cognitive impairments.

It's crucial to advocate for our patients and for the occupational therapy profession's involvement in addressing cognition. Staying informed about neuroanatomy and emerging scientific findings allows us to develop creative and effective treatment plans tailored to each patient's needs, especially when working in a home-based setting.

One essential aspect to remember is that the brain plays a central role in all bodily functions. As Thomas Edison aptly put it, "The chief function of the body is to carry the brain around." Therefore, even when working on physical aspects with our patients, we must recognize the critical importance of cognitive function.

In documenting cognitive deficits influenced by psychosocial aspects during home visits, it's essential to provide specific examples. For instance, if a patient exhibits signs of depression that impact their daily life, you can document the patient's emotional state, any refusal to participate in activities, and your efforts to address their emotional well-being. While we cannot diagnose depression, we can highlight observable signs and symptoms and collaborate with other healthcare professionals for further evaluation and intervention.

Regarding the Allen Cognitive Levels, you can access resources and printouts online. There are books available, such as "Understanding the Allen Cognitive Levels," that can serve as valuable references. These levels can be instrumental in helping patients and their families better understand cognitive impairments and manage associated behaviors effectively.

In summary, occupational therapy practitioners play a vital role in addressing cognition, and we have the tools and knowledge to make a meaningful impact on our patients' lives. By advocating for our patients, staying informed, and using evidence-based approaches, we can help individuals with cognitive impairments lead more fulfilling and independent lives.

Thank you for joining this session.

References

Adamit, T., Shames, J., & Rand, D. (2021). Effectiveness of the Functional and Cognitive Occupational Therapy (FaCoT) intervention for improving daily functioning and participation of individuals with mild stroke: A randomized controlled trial. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(15), 7988. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157988

Cognition, Cognitive Rehabilitation, and Occupational Performance. (2019). AJOT, 73(Supplement_2), 7312410010p1–7312410010p26. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.73S201

Edwards, D. F., Wolf, T. J., Marks, T., Alter, S., Larkin, V., Padesky, B. L., Spiers, M., Al-Heizan, M. O., & Giles, G. M. (2019). Reliability and validity of a functional cognition screening tool to identify the need for occupational therapy. AJOT, 73(2), 7302205050p1–7302205050p10. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.028753

Manee, F. S., Nadar, M. S., Alotaibi, N. M., & Rassafiani, M. (2020). Cognitive assessments used in occupational therapy practice: A global perspective. Occupational Therapy International, 8914372. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8914372

Stigen, L., Bjørk, E., & Lund, A. (2022). Occupational therapy interventions for persons with cognitive impairments living in the community. Occupational therapy in health care, 1–20. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2022.2056777

Citation

Covell-Pierson, K. (2023). Cognitive interventions in the home: A practical approach for OT professionals. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5638. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com