Introduction

Molly: Welcome everyone to our webinar, we are so happy you are here. Here is a little background on Kathryn and me. We both work currently Cardinal Glennon Children's Hospital in St. Louis and have been working together for about 10 years. We have built a relationship and have learned about each other's perspectives on feeding. We respect each other and our scopes of practice, and this is how we have helped each other make changes in all of our patients.

Mealtime Relationships

If you look at this photo (Figure 1), you can see everyone is having so much fun and this is how it should be.

Figure 1. Mealtime relationships.

Meals should be fun and social. Feeding is the primary occupation of children necessary for growth and development. Even though we work in a hospital, we both strive to keep pictures like this in our head as an end goal for the kids in our care. As a side note, you are going to hear me reference the PEO, Person Environment Occupation, framework during this talk. I find it to be a really good framework to identify, break down, and resolve dysfunction in feeding.

Relationship-Based Feeding

- “A holistic approach is key to addressing multiple factors while supporting the feeding relationship. Data obtained through a systematic review of the literature support multiple types of feeding interventions (i.e., oral–motor, parent-mediated, positioning, behavioral) because of the complex nature of feeding difficulties.”

- “Occupational therapy offers a unique perspective on feeding, eating, and swallowing because it considers all factors involving the person, environment, and occupation.”

- “Most children with complex feeding problems have a combination of underlying issues that are best addressed by an interdisciplinary team.”

- “Feeding is a primary occupation of children that is necessary for their growth and development.”

- “Feeding is a social activity and involves a dyadic relationship between the caregiver and the child.”

Henton, P. A. (2018). The Issue Is - A call to reexamine quality of life through relationship-based feeding. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72, 7203347010. https://doi.org/10.5014.ajot.2018.025650

One of the articles that we came upon was by Henton in AJOT in 2018. It stated that most children with complex feeding problems have a combination of underlying issues that are best addressed through a multidisciplinary team. Kathryn and I feel that a holistic approach by an interdisciplinary team is the best way for us to support our patients. We come from different backgrounds, but we have similar beliefs about how kids should eat and the development that feeding should look like in the life of a child.

Putting Collaboration Into Practice

- OT/RD have similar assessment questions and collaborating while interviewing the caregiver together allows us to benefit from the discipline-specific knowledge as well.

- OT/RD working together sends the caregiver a consistent message, which allows them to trust the process.

- Improves productivity of RD/OT because they communicate verbally and simultaneously between caregivers and the medical team.

- OT/RD complement each other’s scope of practice to determine how and what to feed the patient.

We have a lot of similar assessment questions and collaborating during the interview of the caregiver allows us to benefit from our discipline-specific knowledge as well. I have learned so much by listening to what Kathryn asks caregivers. Sometimes her questions are very similar to what I want to know and why I want to know it. It also sends the caregiver a consistent message. I think when the caregivers see us together this gives them more trust. It also improves productivity because we communicate verbally and simultaneously with the caregiver and with the medical team. Often my questions are prompted by one of Kathryn's questions and vice versa. We complement each other's scope of practice.

Let me now give you some examples of how this works in practice. I might get an order, and when I look at the chart, I see Kathryn also has an order or she has already put a note in the chart. We then make sure to get together to talk about the case. As productivity is such a priority for health care as all of us know, this collaboration cuts down on the time needed as compared to when we are trying to see patients separately and then finding a time to sit down and chat. Sometimes, we can catch the rest of the team on rounds and give our opinions on a case to help with treatment planning in real time. If these team members have specific questions they can always contact us, but it is nice to be there together and working as a team.

Clinical Abbreviations

- NG tube: nasogastric tube (nose to stomach)

- ND tube: nasoduodenal tube (nose to the duodenum)

- PN: Parental Nutrition (IV nutrition, aka “TPN”)

- EN: Enteral Nutrition (feeding that uses the gastrointestinal tract for nutrition delivery, via a tube)

- PO: by mouth

Kathryn: Thank you, Molly. Before we jump into the research and our case studies, we do just have a few clinical abbreviations we wanted to share. An NG tube is a nasogastric tube that goes from the nose down to the stomach. This is primarily used for bolus tube feedings. An ND tube, nasoduodenal tube, goes from the nose to the duodenum into the intestines, and an ND tube is used for continuous feedings. You cannot put a bolus feeding into the intestine so an ND tube is just for continuous feeds. PN stands for Parenteral Nutrition which is IV nutrition, and that is commonly referred to as TPN. EN is Enteral Nutrition or feedings that use the gastrointestinal tract for nutrition delivery by way of a tube. NG tubes and ND tubes deliver enteral nutrition. And then, PO means by mouth.

Pediatric Feeding Disorders (PFD)

- In 2018, Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition established a Consensus Definition

- Pediatric Feeding Disorder (PFD): “impaired oral intake that is not aged appropriate, and is associated with medical, nutritional, feeding skill, and/or psychosocial dysfunction”.

- “To be fully functioning, a child’s feeding skills must be safe, age-appropriate, and efficient. Dysfunction in any of these areas constitutes PFD."

- Acute < 3 months, but > 2 weeks

- Chronic > 3 months

Goday, P., Huh S. Y., Silverman, A., Lukens, C. T., Dudrill, P., Cohen, S. S.,… Phalen, J. A. (2018). Pediatric Feeding Disorder: Consensus definition and conceptual framework. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000002188.

Prior to last year, there was no universally accepted definition for feeding disorders. In 2018 the Journal of Pediatric, Gastroenterology, and Nutrition established a consensus definition. Pediatric feeding disorder or PFD is impaired oral intake that is not age-appropriate and is associated with medical, nutritional, feeding skill, and/or psychosocial dysfunction. This definition is multidisciplinary. It acknowledges that there are so many factors that can affect feeding. The authors also identify that safety and efficiency with feeding is part of the dysfunction that can define pediatric feeding disorder. The duration of pediatric feeding disorder can certainly vary, and duration of fewer than three months is considered acute, while pediatric feeding disorder lasting longer than three months is chronic. It is important to note that pediatric feeding disorder is not appropriate in an acute illness. One criterion is that a pediatric feeding disorder should be present for longer than two weeks. Again, if a child is admitted for a short term to the hospital that would not be pediatric feeding disorder, it has to be longer than two weeks.

- Medical

- Prematurity

- End-stage liver disease

- Congenital Heart Disease

- Nutritional

- Inadequate intake to meet nutrition and fluid needs

- Feeding Skill

- Delayed oral motor/oral sensory skill development

- Psychosocial

- Environment

- Structure of meals and snacks

Let's now break it down into the various domains that affect pediatric feeding and may contribute to the diagnosis of a pediatric feeding disorder. There are multiple medical reasons that may contribute to a child's poor feeding, and we have a few examples listed here. A premature infant may have a prolonged hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit or the NICU. Depending on the gestational age of birth, some reflexes such as rooting and sucking may not be fully developed. Therefore, a premature infant is likely to receive nutrition therapy by tube feeding until that infant acquires the appropriate feeding skills and can gain weight adequately.

Second, a patient with end-stage liver disease may have fluid overload and ascites in their abdomen that could contribute to decreased appetite and calorie intake. Additionally, they may have higher calorie needs due to malabsorption. Children with end-stage liver disease often require some form of nutrition therapy, either tube feedings or parenteral nutrition.

A patient with congenital heart disease may have feeding difficulties due to tachypneic or shortness of breath. They may also have the inability to consume adequate calories to meet increased needs. These patients also often have frequent surgeries and hospitalizations that interrupt feedings.

From a nutrition perspective, a child should always be growing and gaining weight, and if they are not, it is important to consider an alternate route of nutrition. This could be enteral or parenteral.

Any delay in skill development and diet progression can also negatively affect feeding. One example would be that if an infant receives baby food in the bottle instead of from a spoon. This could delay diet progression and skill development. Another example of delayed feeding skills may just be the difficulty transitioning from a bottle to a cup.

Lastly, a child's environment and structure can also hinder feeding. An example may be that if a child does not learn to sit at the table for meals and snacks, they could be easily distracted by playing or just grazing on snacks throughout the day. Ultimately, they may not consume adequate calories to promote optimal growth.

Overall, a pediatric feeding disorder can be complicated by many different factors. Unfortunately, there is now a consensus definition to help practitioners across many disciplines come together to help these children and families.

Infant Case Study: Oral Feeder

- Assessment Interview: what we ask

- Intervention: what and how to feed

- Education: how to transition recommendations from hospital to home

In this case study, we will discuss the hospital course of an infant. We will also review what Molly and I asked during the assessment, the intervention that addressed what and how to feed this baby, and the education that helped the family transition from hospital to home.

Tommy

- 15-week old male

- Born full term at 39 2/7 weeks

- Dx: poor weight in infant, malnutrition, and Tetralogy of Fallot.

- DA from the cardiology clinic

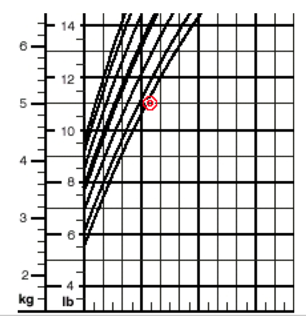

When Tommy came to us, he was almost four months old. He was full-term and had congenital heart disease with a diagnosis of Tetralogy of Fallot. He was directly admitted to the hospital from the Cardiology Clinic for Malnutrition. As you can see on the growth chart, that red dot representing his weight was below the curve.

Figure 2. Tommy's growth curve.

Tommy was born weighing 3.2 kilos and was at the 38th percentile weight for age. His weight for length at birth was at the 21st percentile. Upon admission, he weighed just five kilos. Even though he had grown and gained some weight since birth, it was not adequate, and his weight for his age had fallen to the first percentile. His weight for length indicated that he met the clinical definition of malnutrition. For those of you in a clinical setting, you may be seeing more use of the term malnutrition instead of failure to thrive, which was used more in the past. One way to identify malnutrition is by considering a child's weight for length in infants and the BMI, or the body mass index, in children over two.

- Anthropometrics at birth:

- 3.2 kg = 38%tile with a Z-score of -0.30

- 50.5 cm = 63rd%tile with a Z-score of 0.33

- Weight for length: 21st%tile with a z-score -0.80

- Admission Anthropometrics:

- 5 kg = 1st%tile with a Z-score of -2.42

- 60 cm = 11th%tile with a Z-score of -1.23

- Weight for length: 1st%tile with a Z-score of -2.24 = moderate malnutrition

Other parameters to diagnose pediatric malnutrition include the rate of weight gain, the percent of calorie needs met, and a mid-upper arm circumference measurement.

- Malnutrition Definitions: Weight for length or BMI

- Mild malnutrition = z-score of -1-1.99

- Moderate malnutrition = z-score of -2-2.99

- Severe malnutrition = z-score -3 or less

Nilesch, M., Corkins, M., Lyman, B., Malone, A., Goday, P., Carney, L…. and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) Board of Directors (2013). Defining pediatric malnutrition: A paradigm shift toward etiology-based definitions. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 37(4): 460-481. doi: 10.1177/0148607113479972

The diagnosis of malnutrition can also be classified as disease related or non-disease related, and then either acute or chronic with the same parameters of less than three months or greater than three months. For this particular patient and the purpose of this presentation, know that Tommy met the criteria for chronic moderate and disease-related malnutrition.

Molly and I met with his mother to gather some initial information about feeding Tommy. We wanted to know how often Tommy was eating, how much he was eating at each feeding, and how long the feeding took. These questions give us both a sense of whether the baby is consuming adequate calories and not expending too many calories at the same time as feeding is an exercise for babies. If they nipple for longer than 30 minutes, they may actually be burning more calories than they are ingesting.

- OT and RD conduct interview together to gather pertinent information about feeding

- Mother is an inconsistent historian.

- Mother reports baby takes 2-3 ounce every 3 hours and that feeds take a ‘long time,’ at least 30-45 minutes.

- Mother says pt “usually” feeds on demand.

- Mother reports she mixes the formula “as it says on the can”.

When we spoke with Tommy's mother, she was not the best historian at first. She gave us some vague information initially. She indicated that Tommy was taking about two to three ounces of formula every three hours. However, she could not really give some specific information in relation to just the number of feedings offered or the total ounces he consumed in a 24-hour period. She said he usually fed when he was hungry, and that he did cry and demand feedings. When working with caregivers, it is important to ask how they prepare the formula. You want to get that recipe because we do not want them diluting the formula. If a caregiver is diluting formula and you are worried about their ability to mix powdered formula correctly, one thing you could do is request ready-to-feed formula from WIC if that is a service or a benefit that they receive. Fortunately, in Tommy's case, his mother was preparing formula correctly, 220 calories per ounce.