Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Concussion And Pain: Exploring Treatment From An OT Perspective, presented by Zara Dureno, MOT.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify the most common types of pain associated with concussions.

- Identify 3 main occupational therapy treatment strategies for this population.

- Recognize the nervous system component in pain.

Agenda

- What is a concussion?

- Headaches

- Migraines

- MSK pain

- Sensitized systems- general strategies

Thank you so much for having me. Let's go over our agenda. Today, we will talk about the definition of a concussion. There are some common misconceptions about concussions, so hopefully, we can displace any of those. I did not get much education about concussions, so I learned most of it after graduating. We will discuss common types of pain associated with concussions, like headaches, migraines, and musculoskeletal pain. Those are the three things that I see the most in my practice. We will also talk a little about a sensitized system, what that means, and how we can treat clients who have a sensitized system after a concussion.

Who I Am

I am passionate about concussions from a personal and a professional level. I am a neuroscience nerd and geek out on this stuff, but I also have had some significant injuries. In Figure 1, you can see me as a 13-year-old after a serious horseback riding accident.

Figure 1. Author after a horseback riding accident.

I had chronic pain for many years after that accident, and I have had two very severe concussions. Figure 2 shows me doing my favorite occupation, hiking.

Figure 2. Author hiking.

I can hike, work, and do everything I love because of the education I received around chronic pain and concussions. I also had excellent rehab practitioners. I am passionate about this from many levels, so I want to share my lived experience with all of you.

What is a Concussion?

- As defined by the CDC (2019): "A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury—or TBI—caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. This sudden movement can cause the brain to bounce around or twist in the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain and sometimes stretching and damaging brain cells."

A concussion is a traumatic brain injury caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or hit to the body. You can get a concussion from a hit to the head and a jolt to the body. Anything that causes the head to move back and forth rapidly with force can cause a concussion. I got a concussion in France, and they thought it was not a concussion because the hit was to my body. So even in the medical field and in different parts of the world, some people have that myth. The sudden movement causes the brain to bounce around or twist in the skull creating chemical changes in the brain and sometimes the stretching and damaging of brain cells. It is important to note that there are chemical changes in the brain.

- Not a structural injury- a functional one!

A concussion is not a structural injury but a functional one that affects how the neurons in the brain communicate as the neurons get pulled apart. Imagine the neurons as a road where a flood or a rock slide blocks the road. Your brain has to figure out if it can rebuild that road or if it needs to make a detour. Our brains are pretty good at rebuilding those roads, but it can be done much quicker with the proper rehab.

Many of our clients have the idea that they have a bruise on their brain or actual brain damage that you can see on an MRI or a CT scan. You can not see a concussion with the current technology that we have. They imagine a scary image that causes more symptoms. Dispelling this myth can help people recover from concussions. With the right rehab, concussions are recoverable. In fact, the majority of clients will recover within seven to 10 days.

Depending on the practitioner, these injuries have been called post-concussion syndrome or prolonged concussion symptoms. One reason for prolonged concussion symptoms is physiological with the pulling apart of the neurons. There can also be alterations in blood flow and communication and hormone imbalances in the brain. The pituitary gland is a dangly piece of the brain, and when your brain is jolted back and forth, the pituitary gland is sometimes affected. This is good knowledge to have as OTs due to our holistic perspective and ability to advocate for our clients. Doctors do not receive much education in medical school about concussions, only about 30 minutes total in previous years. Recently, they have increased this concussion education to a couple of hours.

Much of what we will talk about today is advocacy. One of the main advocacy pieces is the knowledge of the physiological alteration of hormones with concussions, and we can advocate for hormone testing.

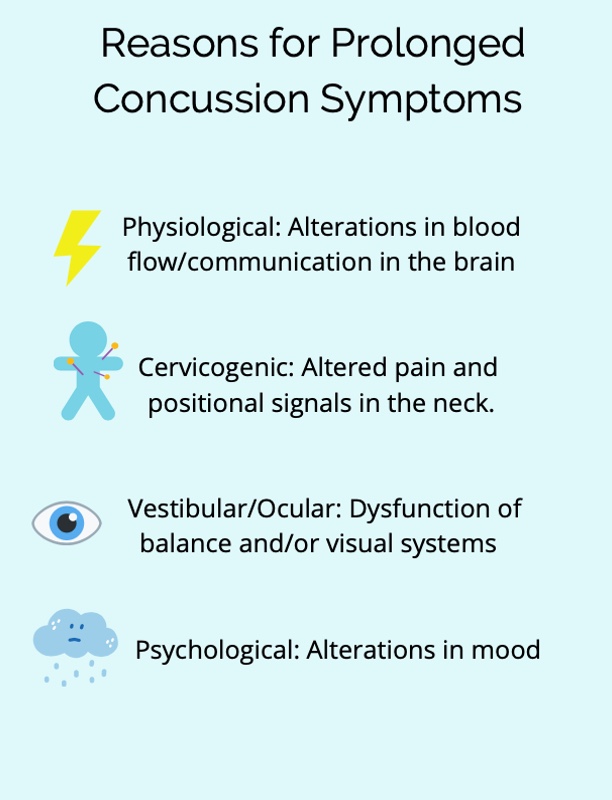

Figure 3. Infographic about the reasons for concussion symptoms.

There are different reasons for concussion symptoms. Physiologically, there may be an alteration in blood flow and communication in the brain. Altered pain and positional signals in the neck may signal a cervicogenic issue. This neck pain and tenseness can also cause dizziness as our necks help tell us where we are in space. Vestibular or ocular problems are caused by dysfunction and how those systems communicate with our brain. This visual dysfunction can lead to balance issues. Lastly, psychologically there can be alterations in mood that can be hormonal or due to changes in roles. They may not be able to do meaningful things anymore.

We will not get into the treatment of all these things today, but we will talk about the cervicogenic component and pain. I wanted to give you the complete picture before we got into the topic.

Migraines vs. Headaches

Migraines are prevalent after a concussion. After one of my concussions, I had intense headaches two or three times a week for an entire year. I have seen people with varying degrees of migraines, but the migraines tend to be very disruptive to people's lives. Clients need to know the difference between migraines and headaches. As OTs, we can provide this education about the difference because they are treated differently.

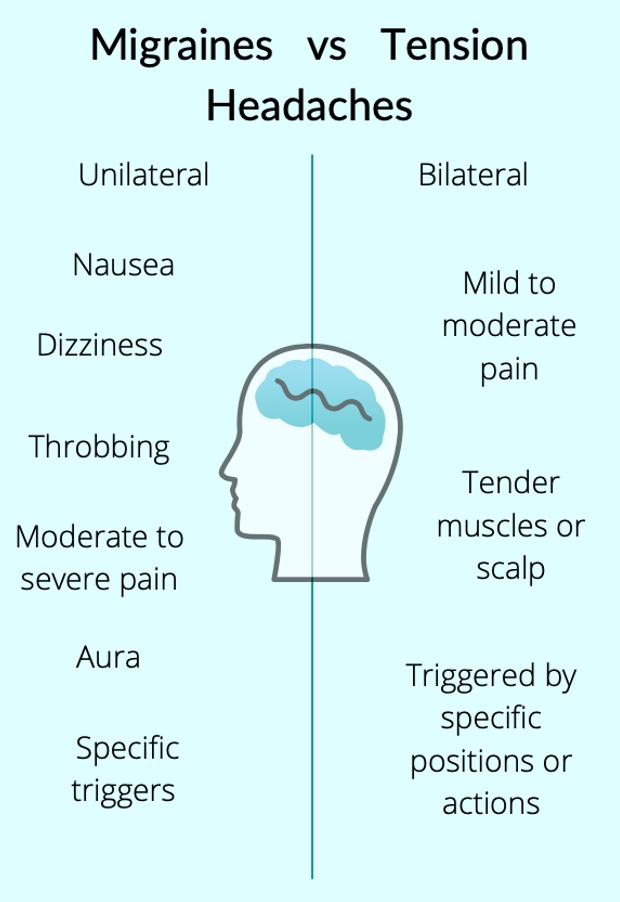

A migraine is an electrical storm in the brain. Something is triggered, and the brain's response is, "This is very dangerous." With this electrical storm, the trigeminal nerve is involved, and it is excruciating. Figure 4 shows the difference between a migraine and a tension headache.

Figure 4. Infographic about the difference between migraines and tension headaches.

Migraines are usually unilateral or on one side of the head and are associated with nausea and dizziness. A typical tension headache usually does not have these symptoms. Migraines have a pulsating and throbbing feeling, which is one of the key indicators. Alternatively, a tension headache is achy but with no rhythm to it. Migraines cause moderate to severe pain where people are debilitated and often cannot move.

Migraines also have an aura. An aura is anything that tells you that you are about to have a migraine. It is usually visual, and there is a theory that the electrical storm starts in the occipital lobe, which may be the cause. An aura can be something like a bit of sparkle, blur, or flashing light in your visual field, almost like a mini hallucination, if you will. This is an indicator you are about to have a migraine.

Migraine Triggers

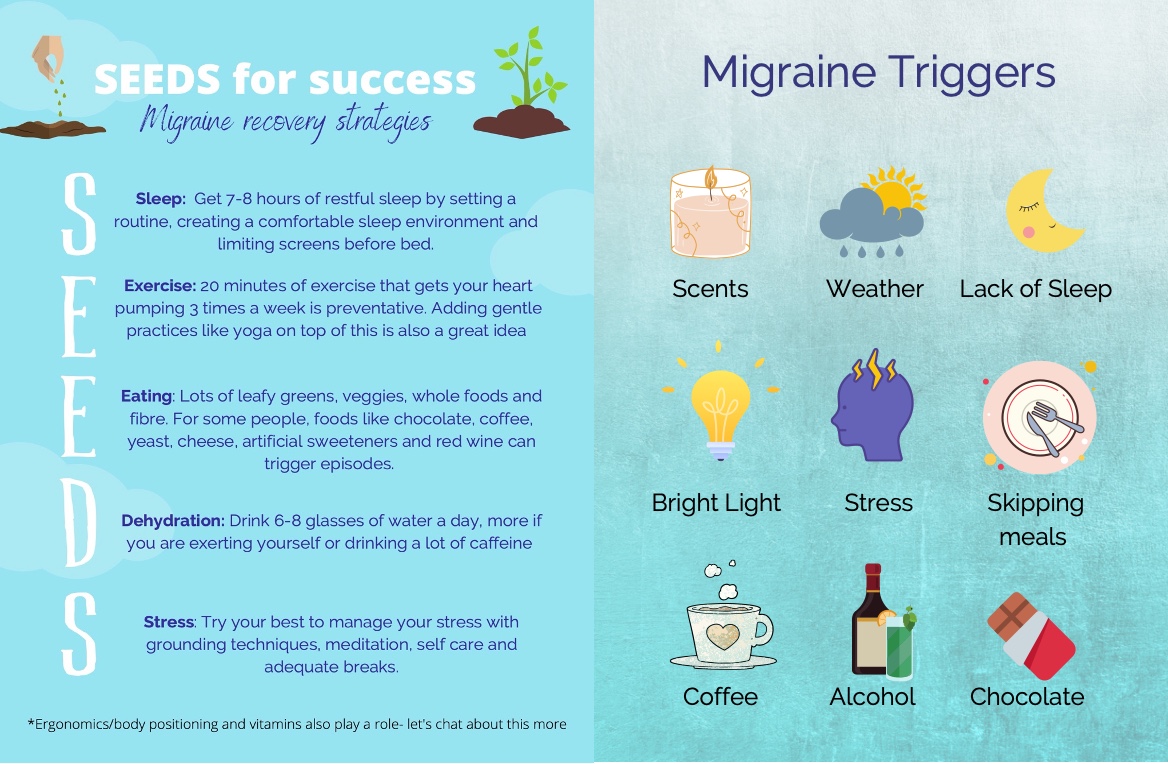

Figure 5. Seeds for success and migraine triggers poster. Click here to enlarge the image.

There are specific triggers for migraines. Some people might get triggered by certain smells or foods. Assisting your client in identifying migraine triggers can be helpful for prevention.

Tension headaches are usually bilateral, and the client experiences mild to moderate pain and tender muscles or scalp. Often, you can palpate their traps and feel the tension in those muscles. These are usually triggered by specific positions or actions or holding a position for a long time. We will get into more detail about these to see how OT fits into the treatment.

Before getting a client connected with a doctor or a neurologist, we can look at SEEDS: Sleep, Exercise, Eating, Dehydration, and Stress. These are the main things that will be looked at for migraine treatment. You can see how OT fits in well with this migraine treatment program as we are experts in sleep hygiene, getting people to do things they love using gradual activity grading, and providing mindfulness-based exercises.

Individuals need seven to eight hours of restful sleep. We can help people to create a routine and set up a comfortable sleeping environment. We can help them with sleep ergonomics with the proper pillows and other adaptations for sleep.

We are good at promoting meaningful exercise by breaking down things they used to do. Perhaps they enjoyed hiking. We can break that down and get them back into that activity gradually. The research shows that 20 minutes of exercise three times a week gets your heart pumping and is preventative for migraines. We can also add in gentle practices like yoga.

We can coach clients to eat better foods like leafy greens, veggies, whole foods, and fiber. For some people, there are certain trigger foods. Clients can complete a migraine diary to identify any migraine triggers. There is also an app called Migraine Buddy, which helps to document daily intake and potential triggers. Identifying migraine triggers is a great way to help a client manage them.

Some common triggers include changes in weather, certain scents, a lack of sleep, skipping meals, stress, and bright lights. Other triggers are coffee, alcohol, and chocolate. Help a client set a routine that makes sense for them, that they do every day to help them get better sleep and eat healthy meals.

Dehydration can be another factor. Drinking six to eight glasses of water a day is important, especially if you have a headache. And if they exert themselves or drink a lot of caffeine, they may need to drink more. As a rule, you want to drink as much water as you have caffeine on top of the six to eight glasses of water because the caffeine dehydrates you.

You can help clients manage stress with grounding techniques such as meditation, self-care, and adequate breaks. When a client is building their routine, pacing is important. We will be talking more about pacing and grounding techniques for a sensitized nervous system in more detail a little later.

Ergonomics and body positioning are also great to review with migraines and tension headaches. For an ergonomic assessment, we can look at their workstation setup and their positioning during daily tasks like dishes or laundry to see if there are any ways to optimize their head and neck position. Currently, as a society, we are bent over our phones and computers all the time. This positioning is not great for migraines or headaches. Even talking with a client about they use their phone and better ergonomic positions can be beneficial.

There are also certain supplements that I tend to recommend for migraines. I always have clients discuss these recommendations with their doctor or pharmacist first. Riboflavin, magnesium, and CoQ10 are the three that are the most beneficial for migraines. Often when clients start taking magnesium, they see significant results. Riboflavin and CoQ10 are also excellent additions to a supplement regime as well.

- Ensure the client is connected with a good doctor or neurologist who can trial medications for them (prophylactics, abortives, botox, etc.)

- There are stimulator treatments available now on the market- may be worth discussing with the client and their doctor (Cefaly)

We also want to ensure that the client is connected with a good doctor or neurologist who can trial medications for them. Again, with the advocacy piece, some doctors and even some neurologists are not familiar with concussions and might not even be very familiar with migraines. In the resources, you will find the UBC headache clinic guidelines that have a list of medications. Sometimes I send that in a doctor's note and ask, "What do you think?"

Several different kinds of medications can be trialed if the SEEDS protocol does not work. Prophylactics are medications people take every day to prevent a migraine, while abortives are things people take when they have a migraine. Botox is another option because it helps loosen up the neck muscles, as tightness can trigger a migraine.

There are also treatments available on the market that stimulate the trigeminal nerve. This is not in our wheelhouse to prescribe any of this stuff, but we can advocate for it.

Managing Tension Headaches

- Chronic pain education

- Referral to a therapist for neck strengthening and manual therapy

- Referral to a pain clinic as necessary or neurologist (botox, prolotherapy, other treatments)

- Education on medication overuse headaches and liaising with doctors about medication

Let's now talk about tension headaches. Chronic pain education is a huge part of managing tension headaches, especially after a concussion. I was told there are many chronic pain education seminars on OccupationalTherapy.com, so if this does not feel like enough, many more are available.

Referral to a therapist for neck strengthening and manual therapy can be another option. Weak supporting muscles in the neck can contribute to tension headaches, especially after a whiplash injury where you tend to see that the deep neck flexors are weaker.

You can refer to a pain clinic as necessary. A neurologist may be able to do Botox treatments that will help. There are also treatments called Provo therapy, which can be done by an MD, a chiropractor, or sometimes a naturopathic doctor. There are many treatments available. One important thing when working in neurological rehab is never giving up hope. Many clients feel hopeless, and I always tell them there is always something more we can try. There is also new research coming out all of the time. I do not want them to lose hope. I am an eternal optimist when it comes to treating my clients.

We also must educate clients on something called a medication overuse headache. If a client takes more than 15 doses of Tylenol or Advil in a calendar month, that may cause headaches. So if a client comes to me post-concussion with horrible headaches, I first ask, "How much Tylenol and Advil are you taking?" 'If they take too much medicine, this could be the culprit. Some of my clients are taking four tablets a day. Usually, what needs to happen is that they need to be put on a different kind of pain medication, aside from Tylenol or Advil. We can flag this as a talking point with their physician.

Chronic Pain- What is Pain?

Answering the question, "What is pain?" is hard. It is a word we use daily but does not have a solid definition. What is your definition, and how would you explain pain to a client? As we go through this talk, I will see if your definition changes from what you have in your mind right now. You can also reflect on if there are any challenges or things that are different for you. Chronic pain lasts more than three months. Before three months, clients are in the acute phase meaning things are healing up, and we would not provide clients with this type of education. We would tell them to treat their pain with rest, heat, and anti-inflammatories. As rehab professionals, we often see them in the chronic phase.

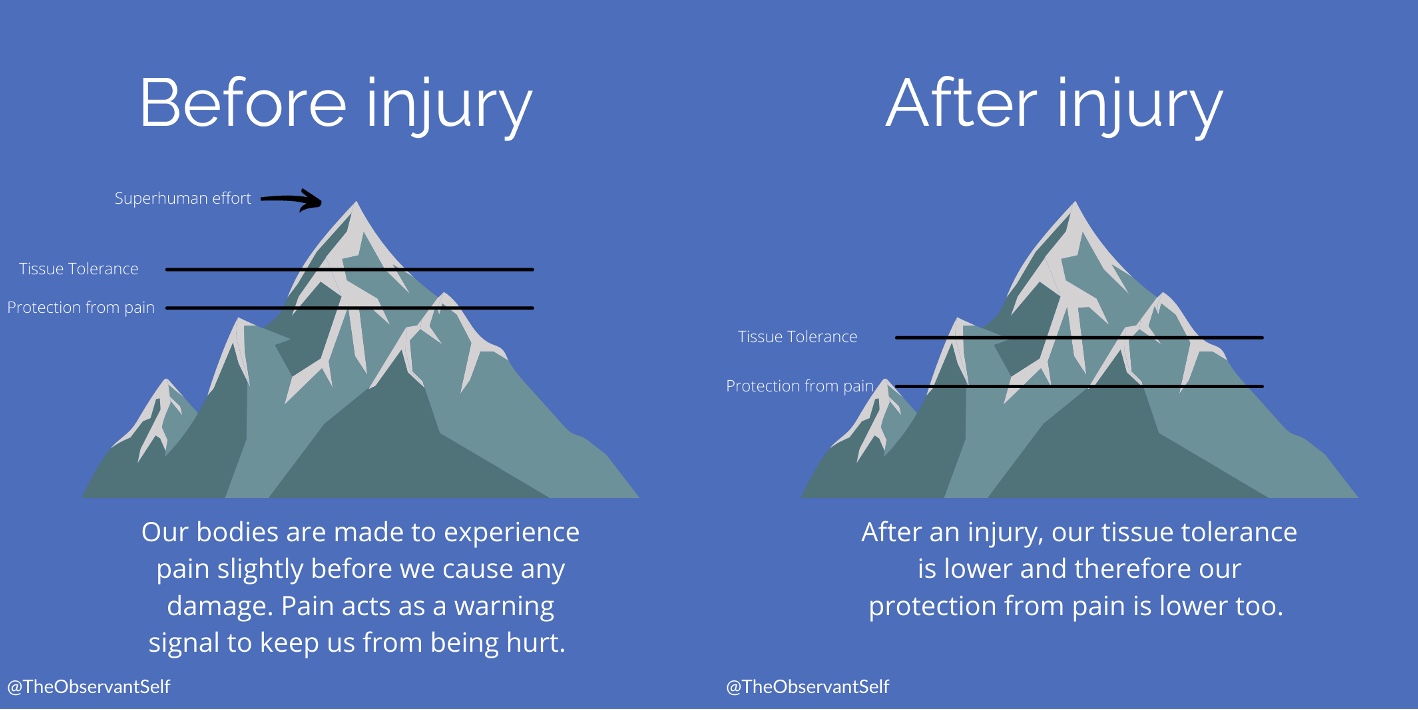

We can look at chronic pain using the Twin Peaks Model (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Twin Peaks Model of chronic pain. Click here to enlarge the image.

If it is safe for you to do, push your finger back towards the back of your hand (the way it is not supposed to go). There is a certain point where your finger says, "No, do not go any further," and you start feeling a little pain. However, if you release your finger, there is no damage. There was a bit of pain during the activity, but there was no damage because we have protection from pain before tissue tolerance. That is what the model is showing. If we were to continue pushing our fingers back and ignore the pain, we would go beyond tissue tolerance and injure ourselves. Our bodies are made to experience pain slightly before we cause damage.

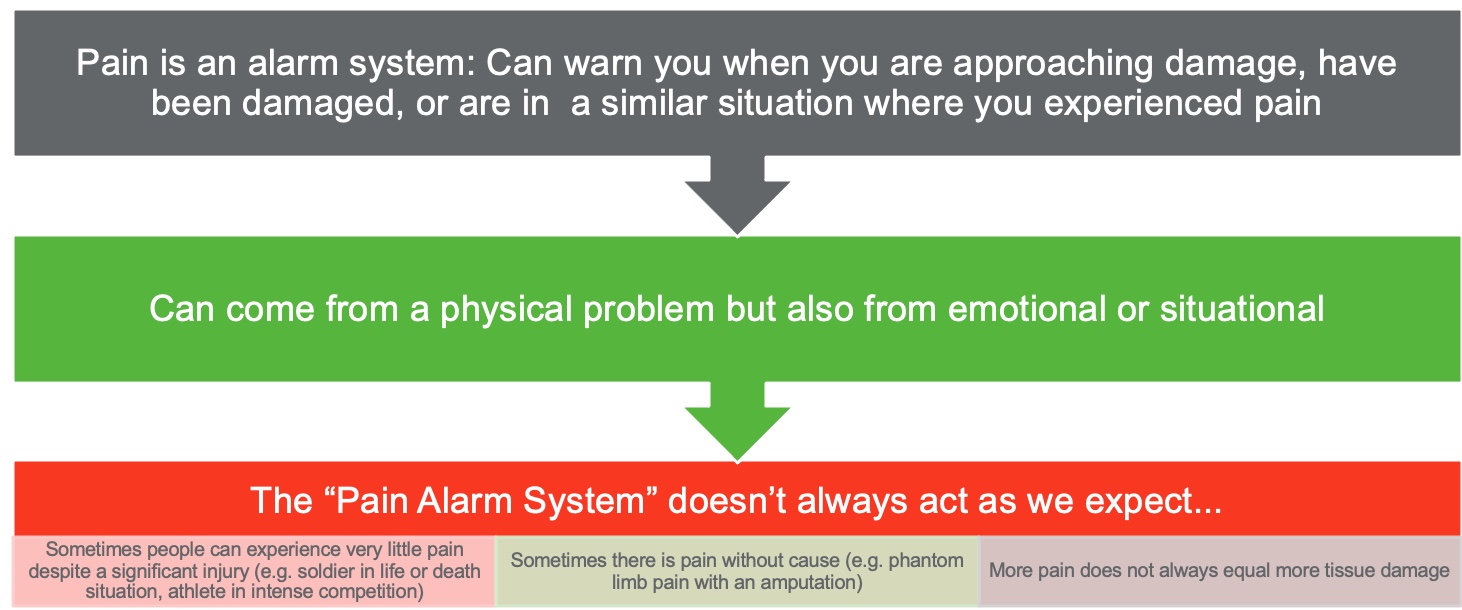

Figure 7. Diagram showing the different areas of the pain alarm system. Click here to enlarge the image.

Pain acts as a warning signal to keep us from being hurt. How many of you identified the definition of pain as a warning cycle? It is not always how we would think about pain, but that is how I want my clients to think about pain. The definition of pain in our minds is that there is something wrong, but the pain is a warning signal trying to protect us. It is like an alarm that is trying to protect us, but it does not always act as we expect it to, and we will talk about that a little bit more.

We have this warning signal and then the tissue tolerance. After an injury, what happens? Let's say I break my finger. After an injury, we have a lowered protection from pain, which means that it will hurt if I even touch my finger after an injury. This does not mean I will injure it again from touching it, but touching it slightly will hurt. And if I move it a little bit, my tissue tolerance is lower, meaning I will probably re-injury it easier. This is within the three months after an injury while that tissue is healing.

After those three months, what should happen is that it goes back to normal. Sometimes, our tissue tolerance is slightly lower, but it usually goes back to our pre-injury level. In chronic pain, our protection from pain stays low when the tissue tolerance goes back up. It might not remain as low as being triggered by touching that specific area, but for some people, it does. As an example, you may not be able to touch someone's neck after whiplash, even after six months. I have a client who is five years post-injury, and I am not allowed to touch her neck at all. The muscles, ligaments, and joints have healed, but this protection from pain continues to be low. Have you ever had a toaster that sets off your smoke detector? It is like that-- a little signal but a big response. With chronic pain education, using our previous example, I need to help my client understand that her neck injury has healed, but there is still an ample protection response.

Central Sensitization

- "Central sensitization is defined as an increased responsiveness of nociceptors in the central nervous system" (Woolf & Latriemollie, 2009).

- Basically, the alarm is always on; the dial is all the way up.

An alarm system warns us that we are approaching damage or are in a similar situation where we have experienced pain. I am not in pain because my finger is broken, but my body is trying to protect me from hurting it more. It is a subtle distinction, and sometimes it does not make sense to people.

Pain can be from a physical problem, but it can also be emotional or situational, meaning that the context and our emotions can influence a person's experience of pain. This is because we have nociceptors or little receptors all over our bodies that detect chemical changes, pressure, and heat. However, they do not detect pain. The nociceptors send signals to the brain, which the brain processes through the limbic system or our emotional system. The limbic system is found in the frontal cortex, our contextualizing system that makes sense of our environment and makes sense of our past. These signals are also put through the reticular activating system, which enables us to be alert.

All pain is produced in the brain. Every time I say that to a client, without fail, they say, "You think I'm making it up?" No, their pain is entirely valid, whether chronic pain, labor, a broken arm, or whatever. Pain is created in the brain because our body does not have pain receptors. Our body has nociceptors that send signals, but the brain decides whether it is going to produce pain or not. I typically say "pain is produced in the nervous system" versus the brain to avoid them thinking that I think they are making the pain up.

Pain also does not always act as we expect it to do. For example, some people can experience very little pain despite a significant injury, like a soldier in a life or death situation or an athlete in an intense competition. Other times, there is a lot of pain without cause. An example of this is phantom limb syndrome. This is where someone will feel pain in a limb that has been amputated. Again, pain is created in the brain and not in the body. The brain has to decide how much danger it is in and if it needs protection. So if we have a sensitized area, like the neck, when talking about concussion, the body does not release that trauma. It says, "I'm protecting this area, so I'm going to produce lots of pain." The point here is that more pain does not always equal more tissue damage, especially in the case of chronic pain. And frequently, there is no tissue damage, and people still experience chronic pain.

Why Do People Have Persistent Pain?

- Mentally: Stress, depression, anxiety, trauma

- Personality: Self-critical perfectionism, Type "A" (Kempke et al., 2014)

- Physically: Bones, muscles, nerves, and ligaments typically take 6-8 weeks to heal from an injury.

- Cancer, arthritis, and nerve damage can sometimes cause chronic pain, but these things are generally noticeable on imaging and have a component of sensitization as well.

- Weaker supporting muscles, stretched ligaments, compensatory movements, and tension in muscles can cause physical pain.

I will pause for a moment on central sensitization and answer the question, "Why do some people experience chronic pain?" There could be mental reasons for chronic pain like stress, depression, anxiety, and trauma. As we discussed, the limbic system is involved in the brain's decision of whether it will produce pain or not, so our "emotional" brain is involved in the production of pain. That is why sometimes emotional pain can even feel like physical pain. But if somebody is under stress, depression, anxiety, or trauma, their pain will be heightened because of that limbic system involvement.

Personality traits like being self-critical, a perfectionist, or "Type A" may increase the risk of chronic pain, but we are not sure why. They might have a higher body awareness or be more stressed. It is hard to say, but that comes up in the research.

Or, it could be a physical reason. Bones, muscles, nerves, and ligaments take about six to eight weeks to heal. Why do we continue to experience pain if our body structures are healed? Some people might have cancer, arthritis, or nerve damage, but those things are visible on imaging. When talking about concussions, it is unlikely that we would find a tumor or something like that after a concussion, but it is not completely unlikely. We need to ensure that everything is imaged correctly to rule that out, but that is not common.

We see weaker supporting muscles, which is where physio can come in handy. There could be stretched or severed ligaments that are not getting as much blood flow, and these take a little bit longer to heal or may benefit from prolotherapy.

Compensatory movements are where we come in and are things people do over time to protect their neck, for example. You can watch someone do their ADLs using these compensatory movements. For instance, they may not use their neck's full range of motion, even though they can. There is a difference between not being able to do a full range of motion versus being fearful of doing full range of motion. You may also see protective mechanisms like people pulling up their traps to their ears to protect their necks as much as possible. Somebody may use their whole body to check their blind spot when driving instead of turning their neck. We must watch our clients through different ADLs to see if they use these compensatory movements. And if we see them, how can we get them to move more fluidly?

Tension in our muscles can cause physical pain as well. When looking at those compensatory movements, we need to make sure that we give them pain education and help them to retrain those movements. Pain education in itself is a pain treatment. You can tell them about the Twin Peaks theory, the phenomenon of hurt versus harm, and that pain is not necessarily equal to tissue damage. Musculoskeletal pain after a concussion can be treated via this pain education.

As I discussed earlier, nociceptors detect chemical changes, pressure, and heat. They send that information to the brain so it can interpret it and decide whether it will produce pain. Central sensitization often happens with chronic pain, where those nociceptors become more sensitized and send more signals to the brain. It is like a sensitive fire alarm that goes off every time you make toast or a dog that barks at everyone walking by instead of just barking at an intruder. Our nervous system becomes sensitized, and the nociceptors send off more signals. So light touch is going to feel like deep pain like you would see with tissue damage. The alarm is always on, and the dial is always up.

This happens a lot with concussions. We see dysautonomic regulation, where people are in fight or flight or sympathetic overdrive, which we will discuss shortly. Being in sympathetic overdrive can cause an increase in musculoskeletal pain in the neck and shoulders. We want to educate clients on this and give them ways to desensitize their bodies and the pain. Sometimes it's just a matter of getting them to do their ADLs without reacting to the pain or engaging in as many pain behaviors. They need to slowly learn to touch the area with different sensations (different clothes), temperatures, and movements.

Polyvagal Theory and Pain

- Fight

- Flight

- Freeze

- Ventral Vagal

I love the polyvagal theory as it is an excellent way of explaining things to our clients. It also helps them to understand what happens after trauma. A concussion is a traumatic injury. You do not always see people as traumatized if a concussion occurs from a sport because they are doing something they love. Still, people can become quite traumatized if a concussion happens from a car accident or something of that nature. If you think about it evolutionarily, we were not meant to drive around in two-ton things of metal.

- Breakdown of the Nervous System

- Central nervous system: Brain and spinal cord

- Peripheral nervous system: Nerves that carry info to/from CNS

- Somatic (conscious): muscle movement

- Autonomic (unconscious): internal organs

We are talking about the autonomic part of the peripheral nervous system or our unconscious control of internal organs. If a lion were to jump into my room right now, I would either fight it, run away, or curl up in a little ball and freeze. If I could not process that trauma once the lion left and I survived, those feelings would get stuck in my body. This is how I try to describe it to clients. The fight-flight-freeze feelings can get stuck in our bodies, and it can cause a lot of anxiety, anger, and frustration. The freezing part can cause shame, shut down, depression, depersonalization, or dissociation, where you watch life like it is a video. This is reported a lot in my concussion clients. There is also a significant increase in anxiety. I explain to them, "You've been through a trauma, and this is a very normal response. There's nothing wrong with you, and you're not an anxious person now. It's your body's responding to trauma in the normal way that it would to protect you and help you survive." People's bodies are sensitized after a concussion, and light, noise, or touch can feel like a mortal threat.

I refer to the amygdala, the little almond-shaped part of our brain responsible for turning on this fight-or-flight system, as the screaming almond of terror. It is always saying, "I'm going to die!" Those who are post-concussion have an amygdala that is always on alert. We want to help reduce these clients' pain and concussion symptoms by engaging the ventral vagus nerve.

The ventral vagus nerve runs from the base of our skull into our stomach. It is a major highway that connects our brain and stomach, which is vital because 90% of our serotonin, our happy chemical, is produced in our bellies. So we need that highway to be running and communicating well. A concussion can be another reason why people in chronic pain are very depressed after a concussion. It also goes down past the belly into the pelvis. It is called the vagus nerve, which in Latin means wandering as it wanders all around our body and helps us to rest and digest. It is also socially connected and helps us feel creative and calm. It helps us do the work we love because we are focused. This nerve becomes weaker after trauma as people get into a sensitized pain system. This weakness can cause migraines, chronic pain, and other symptoms.

Stimulating the Ventral Vagus Nerve

- Diaphragmatic breathing

- Cold exposure

- Horse breath

- Laughter

- Sensory modulation/Safe activities

- Butterfly hug

- Cupping hands over eyes

There are hundreds of ways to stimulate the ventral vagus nerve, with many excellent books and teachers. I will go through some of the ways I find the most beneficial or that I like the most.

Diaphragmatic Breathing

The very first one that I teach all my clients is diaphragmatic breathing. Diaphragmatic breathing stimulates the ventral vagus nerve and reduces tension headaches, and migraines. If we are breathing from the apex or only the top of our lungs, then we use accessory muscles in our neck to breathe. This is top heavy breathing, and usually, shoulders also are involved. This type of breathing can cause a lot of tension in the neck, headaches, and pain. Teaching clients to breathe diaphragmatically will help them calm down and reduce tension and pain.

I have clients put their hands on their lower ribs and provide pressure or resistance to the diaphragm. I then have them breathe into their hands and the back of their lungs. It expands the lungs to the sides and back, and their belly will expand simultaneously. If they find that hard to do, it probably means they are not doing it often. Diaphragmatic breathing will help build up the diaphragm muscle and the vagus nerve to work better.

If people have trouble doing this in a seated position, you can have them lay down. Teaching people how to "belly breathe" into their diaphragm and making the exhale longer than the inhale will stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system and ventral vagus nerve. When we inhale, it stimulates our sympathetic nervous system and wakes us up. On the other hand, a long exhale stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system and is calming. Retraining our breathing sounds simple, but it can benefit our clients.

Cold Exposure

The next one is cold exposure. Some of my clients hate this one and refuse to do it, which is fine, while others love it. I love it most of the time. We have this thing called the mammalian diving reflex. When we go into cold water, like diving in cold water, our nervous systems become more alert and calm. We can do this in a few different ways by either filling a sink with cold water or taking a cold shower to stimulate that ventral vagus nerve. Clients can incorporate this into their daily routine.

Horse Breath

Horse breath is what it sounds like and is a little silly. It is good for clients with kids because they can do that with them as a way of regulating.

Laughter

You can encourage clients to listen to comedy podcasts, watch comedy shows, or socialize with friends.

Sensory modulation/Safe activities

Sensory modulation is where OTs shine. We can use sensations to either activate somebody in a frozen state or calm them down if they are in a fight-or-flight state. We can think about what kinds of things people might see, hear, taste, touch, and smell that would be either activating like lemon or calming, like lavender. Other ideas include using weighted blankets, squeezing a ball, or rocking in a chair. There are great occupational therapy-based courses in sensory modulation.

Butterfly Hug

A butterfly hug is squeezing yourself. You can also tap on both shoulders to help with bilateral stimulation of the brain.

Cupping Hand Over Eyes

You can try this right now if you want. Warm your hands up and hold them over your eyes. Then, take a few nice deep breaths with your hands over your eyes. It is relaxing and nice for our clients who need a break from being on the computer for too long.

Pacing to Enable Occupation

- Green/Yellow/Red zones

- Frequent breaks (timed)

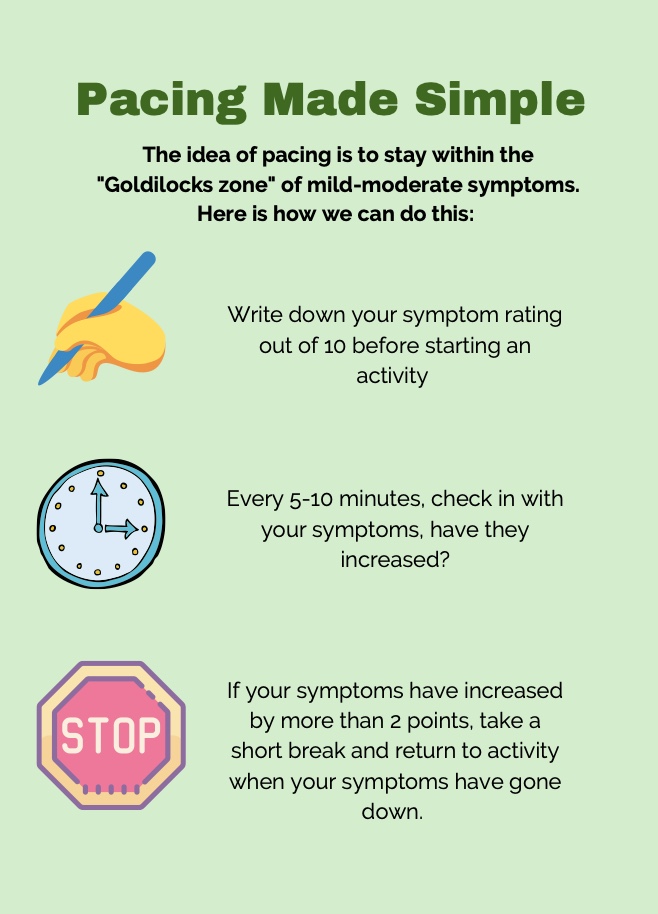

Meaningful activities are another great intervention, but we must consider pacing. Parkwood Pacing Graphs, out of a research facility in Toronto, is a good resource. I am sure we have all had much education about pacing and how to do it. However, you may not have heard it described this way before.

First, I like to tell my clients about green, yellow, and red zones. Green is a zone where the activity does not cause any symptoms, yellow are some symptoms, and red is where there are so many symptoms that they have to rest for a few hours. Often, we see clients go from green to red and back to green. They are "booming and busting." Instead, as we go through their daily activities, we encourage them to go into the yellow a little bit and then take a break and repeat. More frequent breaks will give them more extended time, which is especially important for chronic pain and concussion.

I check in with them every 10, 15 minutes, "Do you need a break? How are you feeling? Where are your symptoms?" Getting them to pace themselves can make all the difference. I've had clients who have had post-concussion symptoms for 15 years, and getting them to pace has completely changed their symptoms and pain. Here is a way to simplify pacing in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Pacing made simple infographic. Click here to enlarge the image.

Another handy way of thinking about this is, on a scale of one to 10, have them write down how bad their symptoms are before starting an activity. Then, every five to 10 minutes, check in with them. If they increase more than two points, they need to take a short break and return to the activity when the symptoms have gone down. When I say a short break, it could be two minutes. It does not have to be long, but the idea is that we are regulating the nervous system.

You can use some of the techniques we just went over to help them calm their nervous system, and then they can return to the activity afterward. This is getting them in the "Goldilock zone" or that just right challenge we talk about in OT.

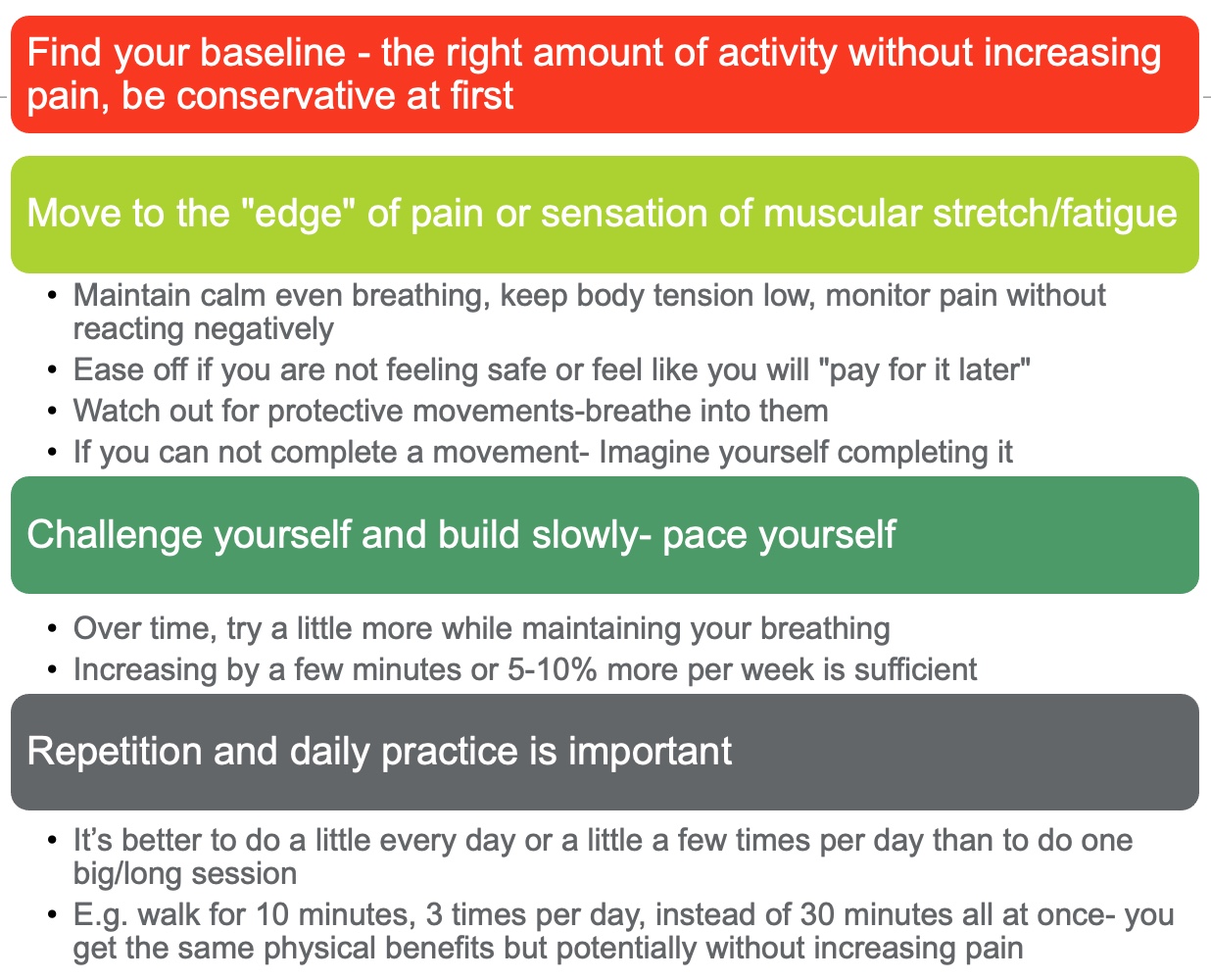

Exercise Principles for Chronic Pain

When we talk about exercise principles, here is a helpful resource in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Exercise principles for chronic pain. Click here to enlarge the image.

We want to help people find their baseline for meaningful activity. Even if we are talking about something like doing the dishes, laundry, or participating in whatever ADLs, we want to see that they are maintaining calm and even breathing with their body tension low. They should be able to monitor their pain without reacting negatively.

As I discussed earlier, we are looking for compensatory movements, pain behaviors, and muscle guarding. For example, I reach for something off a high shelf, and I am engaging my traps and my arm muscles, which is muscle guarding. We want them to only use the muscles they need for the activities that they are doing. Suppose they are demonstrating pain behaviors, even saying expletives. In that case, we want to try and encourage them to reduce those pain behaviors as they are a huge contributing factor to chronic pain. Some people have claimed that those two things cause a transition to chronic pain. We want to make them aware and help reduce them. Protective movements are not what we want. And, of course, we want to ensure they are doing something safe and building up to a specific lifting capacity or movement.

We are going to challenge them and build slowly with pacing. We do not want them to start out lifting or running like they used to do. They are building up a tolerance to meaningful activity in a slow way. If they are doing something they enjoy, like listening to music or chatting with friends while working on something, they will have pleasure and not as much pain. As OTs, we are great at finding what makes things fun and engaging for people. Find what makes the things they have to do around their house fun and engaging; that can honestly be half the battle with pain.

Other Strategies for Pain

- Change the language

- Visualizing (Changing the pain, doing activities, putting out fires)

- Distraction techniques

- Mindfulness/meditation (Parsons et al., 2017)

- Expressive writing

- Engagement in meaningful activity (pleasure is opposite to pain)

- CBT or ACT (Viane et al., 2003)

- EFT (tapping)

Change the language around pain. They can give pain a name like, "John is being a real bother today." That is as long as they do not know someone named John. They may say, "It feels like I'm being stabbed." The image of being stabbed is terrifying, and that visual may produce more pain. We want the language around pain to be as objective as possible. Even see if we can change the word pain to something like discomfort may make a difference.

Visualizing can be a really powerful tool. There are many different visualizing pain exercises, like imagining the pain as a fire in your brain and they are putting it out. Or they might imagine the color red in the area and turn it to the color green. Many high-performance athletes picture themselves getting a perfect goal or something like that, then they do better. Our brains are amazing, especially our occipital lobe and visual cortex, in changing brain thoughts so that visualization can be a great technique.

Distraction techniques can be helpful if the pain is intense, and there are many things that you can look up. Mindfulness and meditation are super beneficial for concussion and pain. Expressive writing can be as simple as setting a timer for 20 minutes and writing to process emotions.

Again engagement in meaningful activity is the opposite of pain. We tend to focus on ADLs, but I would argue that leisure can be one of the essential things for pain and concussion. Participating in something meaningful can change how somebody interacts with their body and experience symptoms. This is how OT started. We were helping people after the war to do basket weaving and other leisure activities to engage them. Whatever homework I have for a client, I always add one fun thing.

Cognitive behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy are excellent therapies with a lot of research behind them for treating pain and concussion. If you can get trained in them, they are OT-specific and valuable.

Lastly, EFT tapping is another significant intervention for pain.

Other Helpful Resources

- Curable app

- Insight Timer app

- Greg Lehman's pain book (available for free online)

- Explain pain YouTube videos and podcasts/videos with Lorimer Mosely

- UBC headache clinic guidelines

The Curable app walks people through pain education. Unfortunately, it is not free, but they do have free sections. The Insight Timer is mainly free with many different kinds of meditations. Greg Lehman's pain book is free and is available as a PDF. If you are interested in pain after this and you want to know more, I would go and read that book. It is an incredible workbook that I usually give to clients. We work through it together.

Explain Pain YouTube videos and podcasts with Lorimer Mosley are other great resources. That is where I learned all of my pain education through Lorimer Mosley's pain modules. His research is incredible, so check him out.

The UBC Headache Clinic Guidelines are some of the most updated research on managing headaches.

I hope all this information helps you with your clients. Thanks for listening.

References

Citation

Dureno, Z. (2022). Concussion and pain: Exploring treatment from an OT perspective. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5517. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com