Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Creating a “Sensory Safe” Evacuation Plan, presented by Kathryn Hamlin-Pacheco, MS, OTR/L.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to differentiate between the experience of a natural disaster from the perspective of a person with and without a disability.

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze potential challenges that a person with sensory processing dysfunction/disorder might encounter during an evacuation.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify an evacuation plan that meets the sensory needs of an individual with sensory processing disorder/dysfunction.

Introduction

Thank you so much for having me. I’m truly excited to be here, sharing this information with all of you. There’s a lot to cover, so let’s dive right in.

I’d like to begin by sharing a bit about how I came to focus on this topic. I am an occupational therapist, but my journey began as a teacher. In the classroom, I gained some familiarity with sensory processing and integration, though, at that point, I hadn’t imagined it would become such a central part of my professional life. When I decided to pursue my master’s degree, I was thrilled to study at Virginia Commonwealth University. Not only does VCU have an excellent faculty, but they’ve also hosted some of the leading figures in the sensory integration (SI) world.

Coming into the program as someone already acquainted with sensory processing, I was eager to deepen my understanding but was skeptical. I never envisioned focusing my career on SI; I assumed it would be one of many areas I’d explore before moving on to something else. However, life has a way of surprising us. My first job out of school was at an SI clinic, and I quickly discovered how much I loved this area of practice. That experience sparked a passion I never anticipated, and I've never looked back.

At the time, I lived and worked in Clearwater, Florida, while my husband served as a helicopter pilot in the Coast Guard. His work often involved disaster response—flying those helicopters you see on the news and rescuing people during or after hurricanes. Because of the nature of his job, our family became deeply immersed in disaster preparation and response.

Eventually, I started to notice an overlap between our worlds. Many of the families my husband was rescuing during hurricanes were those who either couldn’t evacuate or were at high risk during a disaster. At the same time, I was working with sensory kids and their families. I wondered what an evacuation would look like for these sensory families. As I reflected, the answer became clear. For many of them, evacuation would be extraordinarily difficult. For some, it would feel almost impossible.

When I started investigating this intersection of disaster response and sensory needs, I realized no one was discussing it. This gap was critical, and I knew something had to be done. That realization set me on a new path, one where I’ve worked to raise awareness and develop strategies to support these families in moments of crisis.

So, here I am, thrilled to share this information with you. I hope we can illuminate this important issue together and create meaningful change.

Natural Disaster 101

I'd like to start with Natural Disaster 101 to get everyone on the same page. We’re very familiar with the idea—and the reality—that natural disasters are increasing in both frequency and severity.

They are on the rise. We’re seeing more of them, and they’re becoming more intense. These disasters affect millions yearly, disrupting lives, displacing communities, and leaving lasting impacts. Understanding this growing trend is essential to preparing for their challenges, particularly when considering how they uniquely affect vulnerable populations, including sensory families. By starting here, we can build a solid foundation for addressing the critical issues ahead.

Who Is At Risk?

"Who is at risk for a natural disaster?" In one sense, the answer is simple: everyone. Everyone is at risk for experiencing a natural disaster, and that risk is only increasing.

Take, for example, some of the flooding in North Carolina this past year. It is a powerful reminder of how unpredictable and far-reaching these events can be. In inland North Carolina, particularly in the mountains, many likely would have said no if you had asked families whether they needed to worry during hurricane season. Hurricanes wouldn’t have seemed like an immediate threat to their area. Yet, we saw a hurricane make landfall, bringing monumental amounts of rain. The impact was devastating—homes were flooded, lives were disrupted, and tragically, lives were lost.

This example highlights how natural disasters can affect everyone, even those who may feel removed from the immediate threat. Whether it’s a hurricane, a wildfire, or a tsunami, these events don’t discriminate. They don’t alter their paths based on who or what might be in the way. Their reach is indiscriminate and often surprising, which underscores the importance of awareness and preparedness for all of us.

"Taking the Naturalness Out of Natural Disasters"

We can say everyone’s at risk, but we cannot say everyone is at equal risk. To understand this more deeply, I’d like to bring in some research from 1976. In the 70s, some researchers put forward an important perspective that reshaped how we think about natural disasters. They pointed out that these events—whether hurricanes, droughts, heat waves, or tsunamis—are not solely about extreme weather or physical phenomena. Instead, they are the intersection of what they called "an extreme physical phenomenon" and "a vulnerable human population."

This idea resonated deeply with me, especially a particular quote from their paper, open source and available online if you'd like to read it. The quote was simple yet profound: "Without people, there is no disaster."

Think about that for a moment. Imagine the most intense hurricane ever recorded—one with unprecedented rainfall, the highest winds, and more tornadoes than we’ve ever known. If that hurricane landed in an area where no people lived, it would remain an extreme weather event. It wouldn’t be a disaster. It becomes a disaster because of its interaction with human lives. The human experience—the impact on people, communities, and their well-being—transforms these events into disasters.

That realization changed how I think about risk. Returning to the question of who is at risk, the answer remains: everyone. However, understanding that disasters arise from the interface between extreme weather and human vulnerability challenges us to dig deeper into why not everyone is at equal risk. This intersection shapes the scale and severity of what we call a disaster.

Who Is At Heightened Risk?

Let’s take a closer look at who’s at heightened risk. I use guiding questions to frame the discussion when I consider this question. I ask: Who’s more likely to be in the path of a natural disaster? Who’s less likely to be adequately prepared for such an event? And finally, who’s less likely to be able to move out of harm’s way or to shelter in place safely?

Exploring these questions reveals significant disparities in risk. Not everyone has the same capacity or resources to prepare for, respond to, or recover from a disaster. Vulnerability is shaped by social, economic, and physical factors, creating heightened risks for certain populations.

One group that consistently emerges in the research is individuals with disabilities. The intersection of disability and disaster vulnerability often amplifies the challenges these individuals face. Critical factors include mobility limitations, difficulty accessing emergency alerts or clear communication, and insufficient support systems for evacuation or sheltering in place. By examining this evidence, we can better understand why these heightened risks exist and, more importantly, what can be done to mitigate them.

This exploration is vital because disasters don’t discriminate in their paths, but the ability to prepare, respond, and recover is not equally distributed. Recognizing these disparities is the first step toward meaningful solutions.

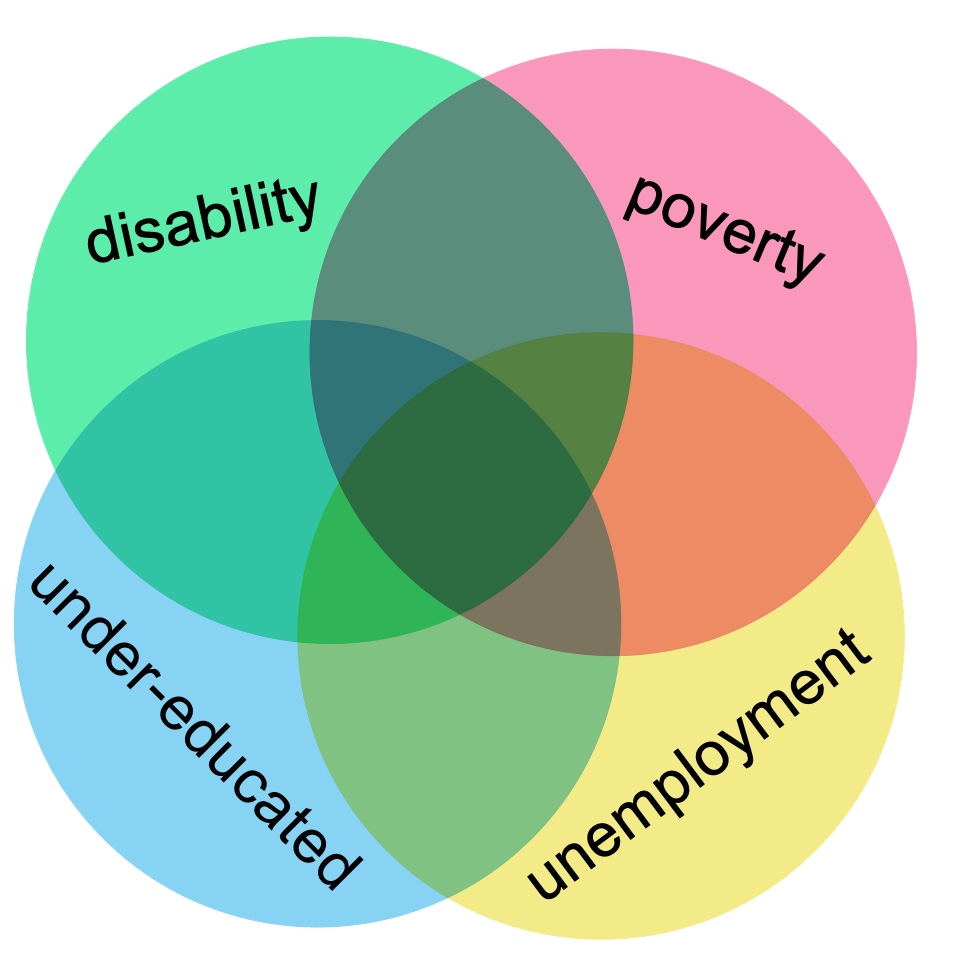

Beyond disability, we must also draw on a broader scope of evidence. Individuals experiencing poverty, those who are underemployed, or those with limited education are disproportionately impacted by natural disasters. These factors, while distinct, often overlap and compound one another, creating systemic barriers to resilience. While this presentation doesn’t allow us to delve deeply into the intersections of these factors, they are visually represented in Figure 1, which provides a snapshot of how these vulnerabilities overlap. Understanding these broader patterns is essential for addressing the full spectrum of heightened risk in the face of natural disasters.

Figure 1. The intersection of vulnerabilities that are at heightened risk.

For instance, people with a disability are more likely to live in poverty, and conversely, individuals living in poverty are more likely to have a disability. There is a clear overlap between these factors, allowing us to draw on neighboring evidence to understand better who is at risk.

I hope to emphasize today that it’s not just abstract populations at risk—it’s our families. The families we work with, care for, and support are often among the most vulnerable.

Let’s begin by looking at information from the U.S. Census Bureau. They explore this exact question: Who is at heightened risk? Their research focuses on community resilience, which they define as the capacity of individuals and households within a community to absorb the external stressors of a disaster. In other words, how equipped are people to cope when disaster strikes?

The Census Bureau has identified key components of social vulnerability that contribute to this resilience. These components can be considered part of a framework or algorithm that reveals the relationships between risk factors. Among the most critical components are disability, poverty, and employment. When we examine these factors, it becomes evident that our families—those with children or individuals with disabilities—are already starting at a disadvantage and are at significantly heightened risk.

This evidence serves as a call to action. Understanding and addressing these overlapping vulnerabilities is not merely important—it’s essential. Recognizing our families' challenges allows us to better advocate for their needs and support them in building resilience against the inevitable stressors brought by disasters.

When we consider the relationship between socioeconomic status and disaster resilience, it makes a lot of sense. Those with fewer resources are less likely to have the means to prepare for disasters, less likely to access timely information, and less likely to recover quickly. This cycle perpetuates vulnerability, emphasizing the urgency of addressing these disparities.

Disaster Impact and Low SES

Americans of low socioeconomic status (SES) are generally less prepared for disasters. When we think about disaster preparedness, we often picture our actions in advance: going out to buy extra food and water—nonperishable items that may not already be on our shelves. These steps require money, often a significant amount.

Think about filling up all the vehicles in your household with fuel—that also takes money and time. Preparing your home might involve boarding up windows, installing shutters, or laying sandbags at the door. These measures are effective but require financial and physical resources, often limited or unavailable for individuals living at a low SES.

Another factor is that people living in poverty are more likely to reside in areas that are at high risk for disaster impact. This is often due to the cost of land or property. Areas that are more vulnerable to disasters, like those prone to flooding, tend to have lower property values because people are generally less inclined to live there. Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans offered a stark illustration of this. Some of the hardest-hit and most devastated areas were low-income neighborhoods well below sea level, where the property was inexpensive because of the inherent risk. When the storm hit, it decimated these communities, leaving families with little to rebuild upon.

These challenges are not just theoretical—they have tangible, often tragic outcomes. Research shows that individuals with low SES experience higher rates of injury and death during disasters. One striking example comes from the 1980s during a heatwave in the Midwest. This wasn’t a hurricane or a tsunami—just extreme heat, a reminder that disasters can take many forms, including blizzards, droughts, and extreme cold.

In this case, local governments recognized the danger and took action, distributing fans for free to anyone in need. People came, picked up fans, and returned home, seemingly better equipped to cope with the heat. However, in the aftermath, it was discovered that many of these individuals still succumbed to the heat. Why? They were worried about their electricity bills. Even though they had the fans, the financial strain prevented them from using them, leading to tragic outcomes.

This example underscores how deeply financial constraints impact disaster resilience, even when efforts are made to provide resources. It’s a powerful reminder of how SES factors compound risk, influencing preparedness and survival. When we look at these overlapping vulnerabilities, it’s clear how critical it is to address these disparities head-on.

Disaster Impact and Disability

During natural disasters, individuals with disabilities are disproportionately impacted, often overlooked, and disregarded. The National Council on Disability, following hurricanes Katrina and Rita, conducted two studies and published two position papers that are freely available online. These reports offer invaluable insights and are a great resource for understanding this population's disaster preparedness gaps.

The Council found that individuals with disabilities were not considered or planned for during these disasters. Their needs were ignored, their voices unheard, and their lives put at unnecessary risk. As a subset of this population, individuals with mental health disorders faced an even greater level of disparity. The findings were staggering: not only were individuals with disabilities neglected, but those with mental health disorders were actively turned away from shelters because of their disability.

This wasn’t a story from the distant past—it happened in 2005 and 2006. These individuals did everything right: evacuating, seeking safety, and making it to the shelters. Yet, upon arrival, they were denied entry because of their mental health conditions. This failure led to what the National Council on Disability described as avoidable trauma and death—a direct result of poor planning and inadequate efforts to help them prepare for and respond to natural disasters.

Adding another layer to this, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), part of the United Nations, has provided crucial insights into how disasters affect individuals with mental health disorders. Their findings highlight a profound double vulnerability. People with mental health disorders, like everyone else, are vulnerable to the immediate impacts of extreme weather and disasters. However, they also lose access to their typical supports—the routines, relationships, and systems we put in place to help them function daily. The IASC emphasized that during disasters, these supports often become unavailable, leaving individuals with mental health disorders exposed and unsupported.

This intersection of disability and natural disasters is vital to understand, but today, we are diving deeper—looking at sensory processing differences and their relationship to disaster preparedness. So, what does the research tell us about this specific intersection? Unfortunately, the answer is very little. Despite the critical need to address this gap, there is barely any research on disaster preparedness and sensory processing differences. I’ve searched extensively, and the lack of evidence is striking and frustrating. This absence of research underscores how much work remains to be done to understand and support families navigating sensory processing challenges in the context of natural disasters.

Disaster Preparedness and Sensory Processing Differences

Because of the information we’ve just discussed, we know natural disasters disproportionately impact our families. While the research on sensory processing and disaster preparedness is limited, there are pieces of evidence we can build upon. As I delved into the literature, I expanded my reading and came across a phenomenal scoping review by Mant et al. from 2021. This review highlighted that children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), for example, experience sensory processing challenges—including heightened sensitivity to light, sound, odors, taste, and touch—that predispose them to greater difficulty coping during disasters. When I saw this, I was excited—it was something concrete we could use as a starting point.

The Mant review cited two additional papers, so I followed the trail. One of the papers discussed sensory disabilities but focused on blindness and hearing impairments rather than sensory processing challenges and integration. The other, a study by Boone et al. from 2001, addressed the unique vulnerabilities of children with ASD in high-stimulation environments like emergencies and disasters. That was encouraging—another piece of evidence—but when I looked deeper, I found the citations led to an OT Practice article discussing children in school settings during emergencies and another article about teaching children with ASD coping mechanisms for disasters. While both offered valuable insights, they weren’t robust research studies.

This underscores a significant gap in the evidence. However, evidence-based practice is not solely reliant on research. It also incorporates expert opinion, clinical reasoning, and personal observation, all of which are valid sources of evidence when used thoughtfully. Clinical reasoning, especially in sensory integration (SI) treatment, involves balancing a child’s unique needs, goals, and interests alongside available research. By combining what we know with expert insights, we can support families in disaster preparation while staying firmly grounded in evidence-based practice.

Here’s my clinical justification: Everyone is at risk of being impacted by natural disasters. Individuals with disabilities—especially those with mental health disorders—are at heightened risk. Sensory processing disorder or dysfunction, often falling under the mental health umbrella, can reasonably be included in this heightened risk category. By extension, families of individuals with sensory processing challenges are also at greater risk during disasters.

In practice, I offer guiding questions to assess risk. For a client, I ask: Does this individual experience sensory-based challenges that interfere with daily life? And do they have an evacuation plan? If the answer is yes to the first and no to the second, it’s time to discuss developing an evacuation plan.

Another way to think about it is this: How much harder will an evacuation be during a natural disaster if an individual struggles to cope with the sensory demands of everyday environments—like a grocery store, classroom, or social event? Evacuations are inherently stressful, and none of us function at our best under extreme stress. These challenges will likely be even more pronounced for individuals with sensory processing differences.

This becomes particularly significant when families weigh the decision to evacuate, shaped by factors like wind speeds, rainfall, wildfire direction, etc. For families with sensory processing concerns, the prospect of leaving a carefully controlled home environment—a space often designed to feel safe and supportive—can feel overwhelming. I’ve had families express that, in some cases, staying home during a Category 5 storm feels safer than evacuating to an unfamiliar shelter where they have no control over sensory inputs. This fear isn’t irrational; it stems from the real challenges their children face.

But this fear can be addressed. We can shift these dynamics by acknowledging these challenges and starting conversations about solutions. Now that we’ve explored the problems, we can move forward and focus on practical, actionable solutions that empower families and help them prepare for the unpredictable challenges of natural disasters.

Make A Plan

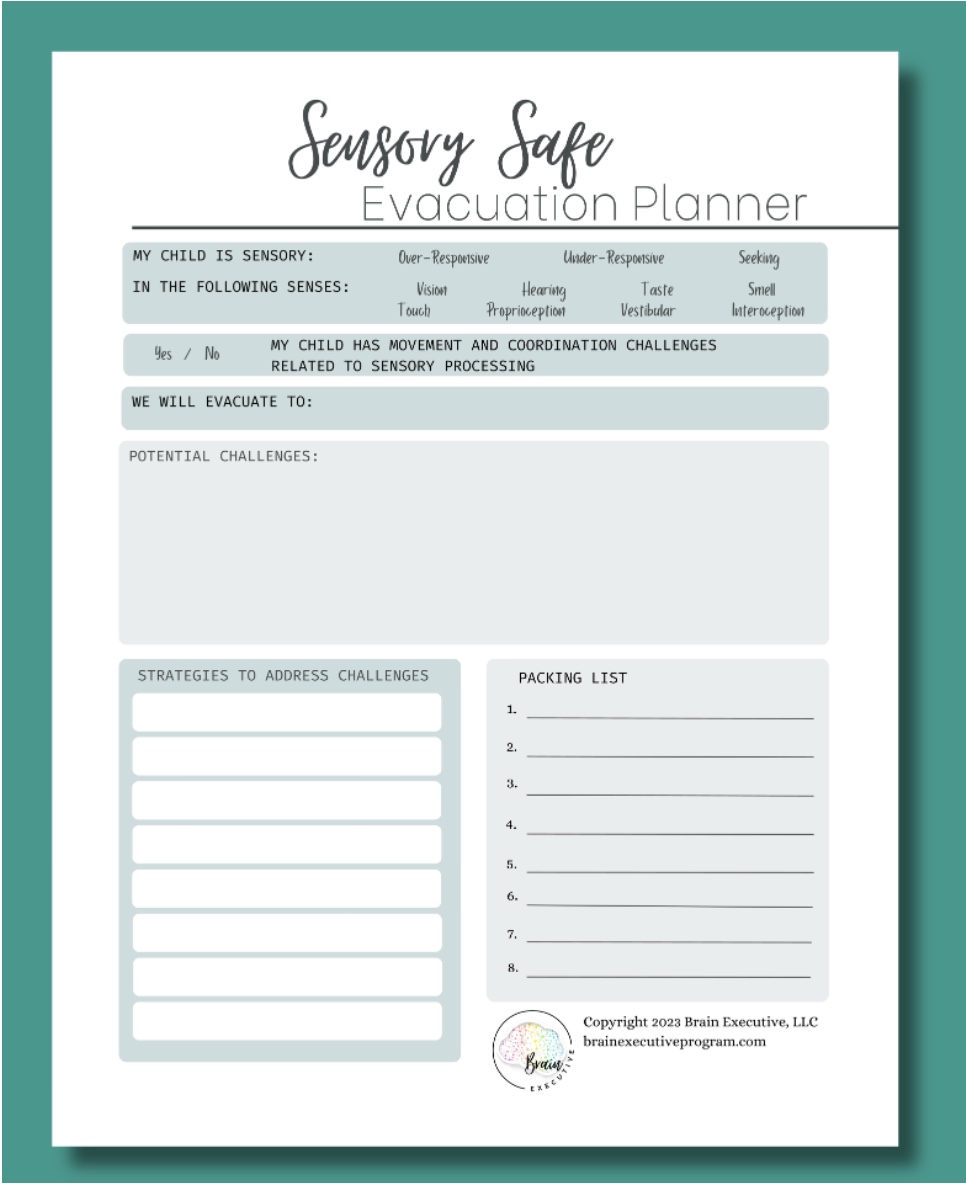

So what can we do? We can help them make a plan. For this Intersection of needs, I got to work and created the Sensory Safe Evacuation Planner in Figure 2. It is also available in the handouts.

Figure 2. Sensory Safe Evacuation Planner (Click here to enlarge the image).

It is designed to help a family or an individual think about sensory-based challenges, consider an evacuation, and make a plan to help them. For the rest of this presentation, we will go through those steps.

There are variations, but we will use the one designed for a family's plan to support a child. There is an adult version; we'll discuss how to get those later.

An Evacuation Plan is Positively Correlated With Evacuating

Before we dive in, I like to emphasize a few foundational ideas. First, having an evacuation plan positively correlates with actually evacuating. This means that when families take the time to create a plan, they are statistically more likely to evacuate if and when the need arises. Whether OTPs, PTs, SLPs, or other healthcare professionals, we support life and well-being. In this case, helping a family develop an evacuation plan is an opportunity to save lives potentially. It’s a profound responsibility and privilege to provide that level of impact.

Another key idea I like to discuss is the distinction between obstacles and barriers. I love the imagery of a tiny figure standing at the base of a massive mountain, looking up at safety at the summit. This visual helps clarify the difference. Imagine if I asked you to close your eyes and picture yourself on an obstacle course. You’d likely imagine yourself climbing, crawling, running, or jumping. It’s challenging, but you’re actively doing it, making progress toward the goal. That’s an obstacle—something hard but achievable with effort.

Now, contrast that with a barrier. If I asked you to close your eyes and imagine yourself at a barrier, you’d probably picture a massive wall or cliff edge. There’s no way forward, no way around. A barrier feels insurmountable—it’s not something you can actively tackle.

Regarding evacuation planning, we want this concept to live firmly in the realm of obstacles, not barriers. Natural disasters and evacuations are inherently difficult—we can’t make them easy. But we can strive to keep the challenge manageable, something families feel they can take on. We don’t want the idea of evacuation to shift into the barrier space, where families feel it’s impossible and give up entirely.

Returning to the mountain analogy, imagine that tiny figure at the base. To him, the mountain may seem insurmountable. But what if we equipped him? What if we gave him the right shoes, a pack of supplies, ropes, and picks and taught him how to climb? Suddenly, what once seemed impossible becomes achievable. That’s what we aim to do when we work with families—help them turn what feels like a barrier into an obstacle they can overcome. This shift in perspective and preparation can make all the difference when it matters most.

Our Responsibilities

For your reference—and because it’s such a meaningful point—I want to mention a fantastic scoping review from 2019 that explored the role of community-based service providers, including therapists, in supporting emergency preparedness for their clients. The review identified seven responsibilities for practitioners in this area, and I love bringing this up because it emphasizes just how impactful our role can be.

We fulfill five of those seven responsibilities by working through this planner with families. We’re identifying vulnerable clients, assessing their unique needs, making an evacuation plan, preparing an emergency kit (because I like to integrate this planner as part of the kit), and providing essential education and recommendations to clients and caregivers. This is such a powerful way to support our families, as it addresses multiple layers of preparedness in a structured and effective manner.

Considering the weight of this responsibility, it’s clear that this work is a heavy hitter in terms of its potential to make a difference. By engaging in these activities, we’re not just preparing our clients for emergencies—we’re equipping them with the tools, resources, and confidence they need to navigate disasters and protect their well-being. This approach aligns with evidence-based practice and demonstrates the vital role we, as therapists, can play in disaster preparedness.

Creating a Sensory Safe Evacuation Plan

Let’s talk about actually filling out this evacuation planner. We will go through it step by step to ensure you’re comfortable and familiar with it. You have the printout or document as part of your handout. You can follow along as we walk through it together—not once but twice. Repetition is key to ensuring you feel confident using this tool in practice.

Now, in real-world applications, this isn’t something that should take a lot of time to complete. Sitting down with a family to work through the planner is intended to be a focused and efficient process. The goal is to guide the family, provide clarity, and ensure they leave the session feeling prepared—not overwhelmed. By the time you’ve walked through it with them, they’ll have a tangible plan they can rely on, one that’s tailored to their unique needs and circumstances.

As we move forward, remember that this isn’t just about filling out a form. It’s about empowering families, reducing their stress, and helping them feel more capable of navigating a potentially overwhelming situation. Let’s dive in and take it step by step.

Step 1: Identify the Client’s Sensory Characteristic

To start using this planner, we identify the client’s sensory characteristics. At the planner's top, you’ll see a section with circles for “yes” or “no,” along with descriptors like sensory over-responsive, under-responsive, or seeking/craving. This is where we define the child’s sensory patterns in the following sensory areas. Take a moment to consider the child’s characteristics and write them down thoughtfully. For example, does the child display movement and coordination challenges related to sensory processing? These are our praxis kids, so ask yourself: Is this a child with praxis challenges? Yes or no?

Starting with sensory characteristics is vital because it lays the foundation for the plan. It allows us to be specific and targeted in our approach. I find this step to be a valuable check-in for my practice as a clinician. Educating kids and their families about sensory processing, integration, needs, patterns, and characteristics is a huge part of my role. If I’ve done my job well, a parent should feel confident filling out this section without hesitation. If they can’t, that’s a sign for me to circle back and reinforce their understanding. After all, we can’t meet needs we don’t fully comprehend.

Before we move on, let’s pause for a reality check. If you work in SI practice, you might look at this framework and think, This won’t fit every kid. And you’d be right. Sensory integrative needs are multifaceted and dynamic. A child might seek or crave one type of input while avoiding or being defensive toward another. Their responses can vary based on the time of day, the environment, or the context. For example, a child might seek sensory input in a classroom but avoid it at home.

When I initially tried to design a planner that captured these dynamics, the result was overly complicated and lost its utility. The purpose of this planner is to be practical and user-friendly—for clinicians and families alike. It’s intentionally simple and designed to fit on one page so families and practitioners can easily apply it. If a child’s sensory characteristics are so complex or dynamic that they don’t fit neatly on one page, I recommend keeping the one-page format for simplicity and printing out multiple copies to capture the full picture.

We don’t want to overcomplicate things, but we also recognize that some children need more support. If that’s the case, use as many planners as necessary. The goal is to balance simplicity with flexibility, ensuring the tool remains practical and accessible while accommodating each child's unique needs. I hope this approach makes sense and feels manageable as you work with families.

Step 2: Identify Most Likely Evacuation Location

Step two is about identifying where the family is most likely to evacuate. Different settings come with unique sensory challenges, so it’s important to consider this as part of the planning process. For example, a local shelter with hundreds of people crammed into one large room will pose vastly different sensory demands than a quiet hotel room with just a few family members. Similarly, evacuating a relative’s home—say, your great Aunt Irma’s house—will look and feel quite different from your home or a public shelter.

I like to sit down with the family and ask, What would you likely do if you had to evacuate? Would they go to a shelter? Would they look for a hotel room? Would they try to stay with family? It’s important to note that their plans might change based on the circumstances, but the goal is to create the best possible plan based on their current preferences and resources.

By identifying the client’s sensory characteristics (from step one) and the likely evacuation setting, we lay the groundwork for the next planning phase. Understanding these two pieces allows us to anticipate potential sensory challenges and consider strategies to address them, which leads us directly to step three.

Step 3: Identify Potential Sensory-based Challenges for that Space

Now, I say, imagine your child with those sensory characteristics in that setting. Tell me about the challenges. What do you see? This is where we open the door to discussing the fears and obstacles that might feel overwhelming. Sometimes I’ll phrase it as Let’s talk about the monster in the room because these fears are often the very things that prevent families from evacuating. Naming and exploring them is a critical part of the process.

For instance, let’s consider the example of a child who is highly over-responsive to sound, as highlighted in that OT Practice article. If the family’s resources only allow for the option of evacuating to a local shelter, we know that large rooms filled with people bring countless unexpected, loud, and unfamiliar noises. At this point, I might ask, How will your child react in that environment?

The mother might reply, It’s not just that she puts her hands over her ears. She runs to the exit. What if I lose her? Or what if she falls to the ground in a full stress response—a complete meltdown with her nervous system overloaded? That’s what I’m scared of.

And that fear is valid. These scenarios can feel overwhelming for families. Whether it’s a child who bolts, shuts down, or becomes physically and emotionally dysregulated, it’s important to acknowledge these challenges without minimizing them.

This is the time to let families express their fears fully. What do you think might happen? What’s the scariest part for you? These discussions help pinpoint their child's specific challenges in an evacuation scenario, tailored to the unique combination of their sensory characteristics and the likely setting.

From here, we move into step four: developing strategies to address those challenges. Once we’ve identified the fears and potential obstacles, we can begin crafting a plan that makes those fears more manageable, helping families feel empowered and prepared.

Step 4: Develop Strategies and Solutions for These Challenges in That Space

Now, let’s think about solutions. I encourage you to focus on this child's specific challenges in the identified setting. I like to remind myself and others to stay on target. What are this child’s particular sensory challenges in this evacuation setting, and how can we support them through these challenges?

Avoid being general—let’s aim to be as specific as possible. Having the evacuation location in mind is a great support for this process. For example, let’s say you have a child whose sensory need is the swing. It’s their go-to tool for regulation. After a stressful day at school, they come home, get on the swing, and you give them that time to themselves. After 30 minutes, they’ve reset and are ready to reengage.

Will that child still need the swing in the chaos and stress of a natural disaster? Likely, yes. But if the family evacuates to a hotel, that swing won’t be accessible. We have to brainstorm alternatives to meet that sensory need. On the other hand, if the family is evacuating to grandma’s house and she happens to have a swing set, fantastic—problem solved.

This level of specificity is crucial. By going step by step, we can pinpoint the child’s needs in a particular setting and figure out how to meet them in that context. Whether creating portable sensory solutions, identifying alternative tools, or finding natural supports in the evacuation environment, staying targeted allows us to craft effective, practical strategies that truly work for the family and their child.

The key is recognizing that every child’s sensory profile and needs are unique. By aligning solutions with their specific challenges and the evacuation context, we give families a real chance to feel prepared and empowered, even in stressful and unfamiliar situations.

Step 5: Create a Packing List

The final step in this process is creating a packing list. Here, I love to borrow from Amy Arnsten’s incredible work on the prefrontal cortex and how it functions—or doesn’t function—during stress. If you’re not familiar with her work, it’s truly remarkable. One of the key insights from her research is that during periods of high stress, the prefrontal cortex essentially goes offline. This is the part of the brain responsible for thinking, planning, and problem-solving, and when it’s not fully engaged, those critical functions are impaired.

Natural disasters and evacuations are inherently stressful. I grew up on the Gulf Coast, so I remember hurricanes vividly from my own childhood. I saw firsthand how stressful it was for my parents. They were worried about the house, scrambling to figure out insurance contacts, taking care of pets, packing belongings—including heirlooms—and getting us all safely into the car. Meanwhile, my two sisters and I bounced off the walls, caught between excitement and fear. My parents were managing our energy on top of everything else, and it was chaos. That stress level makes it easy to forget things, even important things.

When families are evacuating, you can assume their prefrontal cortex is under duress, making it harder to think clearly. That’s why creating a packing list is so crucial. If we’ve devised great strategies to help a child cope in the hotel room or shelter but forget to pack the necessary items, those strategies are rendered useless. A detailed, thoughtful packing list ensures families are equipped with what they need when they need it most.

My hope is that as you help families fill out this planner, you also guide them in creating this packing list. As the clinician, I highly recommend keeping a copy of the completed planner on file. Ideally, families will keep their copy in their go kit, but if an evacuation is imminent and the family can’t locate it, you’ll have a backup to provide. You can call and say, Do you still have a copy? If not, I have it right here for you.

Encourage families to include this packing list in their evacuation plan, to take it with them when they leave, and to ensure it’s part of their preparation process. The goal of this planner is to make evacuations safer, smoother, and less overwhelming, giving families the tools they need to act decisively in high-stress situations. I hope this planner empowers families to navigate emergencies with confidence and care.

Habilitative vs. Adaptation/Modifications

Before we proceed, I would like to briefly discuss the difference between habilitative approaches and adaptation and modification approaches. These represent distinct ways of thinking, and it’s important to understand which lens we use in different contexts.

In SI practice, we often use a habilitative approach. This means we’re working to develop or habilitate skills to create positive changes in a child’s brain and nervous system. We’re helping children build new abilities and strengthen their capacity to navigate the world more effectively.

However, during a natural disaster or evacuation, the focus shifts. In these scenarios, I’m not aiming to grow or develop skills. Instead, I’m adopting an adaptation and modification approach. The goal in these moments is immediate: to ensure safety and survival. It’s about making the necessary adjustments—adding supports, making modifications, and putting adaptations in place—so the family and child can get through the situation safely and as smoothly as possible.

This distinction may seem obvious, but I find it worth revisiting briefly. It helps us center our focus and clarify our role in these high-stakes, high-stress situations. By emphasizing adaptation and modification during emergencies, we ensure that our efforts are practical, actionable, and aligned with the child's and family's immediate needs.

Sensory Needs During an Evacuation

Next, we will discuss specific sensory challenges and how to address them. As clinicians, we’re natural problem solvers, and it’s instinctive for us to start thinking, Okay, how can we tackle this? What strategies can we implement?

For this part, I’ll use the foundational framework of sensory integration (SI) theory and practice, particularly the sensory modulation and praxis constructs from the Sensory Integration Theory and Practice text. While we could delve into more complex theories and advanced techniques, my primary goal is to empower you with practical, accessible knowledge you can apply immediately.

We’ll explore enough examples to get your gears turning, providing a solid base of strategies you can build on in your practice. The idea is not to overwhelm but to equip you with tools and insights grounded in the principles of SI and tailored to meet the needs of the families and children you work with. Let’s start unpacking these sensory challenges and solutions together.

Sensory Over-Responsivity

Let’s start with sensory over-responsivity and what we can do to support a child who experiences this challenge. The key here is preparation and intentional planning to minimize potential stressors.

If this is a child who is over-responsive to sounds and relies on headphones, make sure those headphones are on the packing list. Don’t forget the charger, extra batteries, or any backup items necessary to keep them functional. These tools are crucial in managing auditory sensitivities and providing a sense of calm.

Wearing certain types of clothing might already be difficult for a child with tactile defensiveness in daily life. During the heightened stress of a natural disaster, this challenge will likely be amplified. When packing clothes, prioritize their most comfortable, familiar outfits—this is not the time to experiment with new or less preferred options. Keeping this aspect as manageable as possible can make a significant difference.

Consider whether lighting is a concern, such as over-responsivity to bright or uncontrolled lighting. Pack sunglasses, visors, or a favorite baseball cap. If the evacuation destination allows, perhaps a relative’s home, consider bringing a familiar lamp or a low-light alternative to help the child feel more comfortable.

Consider positional strategies for children who fear bumping into people or being bumped—a common challenge in crowded spaces. I recommend positioning the child between parents or next to a parent who can keep a comforting arm around them. This physical boundary can help them feel secure and reduce anxiety about unexpected contact. Applying deep pressure input, like a firm hug or brush protocol, can provide calming sensory input.

Simple changes can help with vestibular challenges. For example, take the stairs instead of the elevator or escalator when possible. Parents may forget these small but impactful details during stressful moments, so it’s worth highlighting them in advance to avoid potential meltdowns.

Picky eating is another significant area to address. For some children, picky eating is mild and manageable, but for others, it’s tied to deep sensory sensitivities, and their diet may be extremely limited. If the evacuation destination—a hotel, relative’s home, or shelter—is unlikely to have their preferred foods, think critically about how to meet this need. Can you pack enough familiar foods to get through the evacuation period? If the answer is no, parents might understandably lean toward staying home, where at least they can ensure their child eats. Addressing this challenge in advance is crucial to building a viable evacuation plan for these families.

Ultimately, the goal is to anticipate these sensory needs and create solutions that reduce stress, increase comfort, and help the family feel prepared. By addressing these challenges thoughtfully, we help families overcome the obstacles that might otherwise prevent them from evacuating safely.

Sensory Under-Responsivity

For children with sensory under-responsivity, there are specific considerations we need to address to ensure safety and smooth transitions during an evacuation. These kids often require additional support to help them notice their surroundings, stay connected to their group, and manage basic interoceptive needs.

Let’s consider a scenario where the family is evacuating to a relative’s home, and this relative has a fine china collection. For a child who tends to bump into things because they’re not fully aware of their body in space, the solution might be simple: Can the fine china be put away for the weekend? These small adjustments can prevent unnecessary stress for everyone involved.

Wandering or getting separated is another major concern with under-responsive children. They may not notice cues that the group is moving or that they’ve strayed away. Losing a child is one of the greatest fears for any parent. A practical strategy is to establish and practice a meeting point. For instance, if the family is in room 402, write that number on paper and put it in the child’s pocket, pin it discreetly inside their jacket, or attach it to their belongings. If they get separated, they can clearly communicate their location.

Bright, easily recognizable clothing can also be helpful. Depending on the child’s preferences and age, you might suggest visiting a craft store to pick up some brightly colored t-shirts. For example, if the child is wearing a neon yellow shirt, it’s much easier to describe them to others and locate them in a crowd. Similarly, parents wearing matching or similarly bright clothing can make reuniting easier if the child becomes lost. This should always be approached respectfully, considering the child’s comfort and dignity.

Periods of stress can also affect interoceptive abilities. A child who is typically potty-trained might regress in unfamiliar or stressful settings. Packing diapers or training pants as a precaution can provide peace of mind. Similarly, under-responsive children may need reminders to eat or drink because they might not notice hunger or thirst cues. Encouraging parents to pack snacks and water bottles and set meal reminders can help meet their child’s basic needs.

By thinking through these scenarios and implementing simple, respectful strategies, we can help families navigate these challenges and feel more prepared for the unexpected. These proactive measures can make all the difference in ensuring the child’s safety and well-being during an evacuation.

Sensory Seeking/Craving

For our sensory seekers or cravers, it’s essential to consider what tools and activities will help them regulate in unfamiliar and potentially stressful environments. While "fidget" has become overused, the concept remains valuable. For some children, tactile stimulation is incredibly regulating, so if there are specific fidget items or sensory tools they rely on, let’s ensure those are on the packing list. Whether it’s a textured ball, a favorite squishy toy, or a pop-it, these items can comfort and help them stay grounded.

For children who are always on the move and benefit from heavy work activities, we can get creative about incorporating these needs into the evacuation setting. Evacuations often involve suitcases, which are usually heavy—there’s your built-in heavy work! You can help families develop a plan to let the child push, pull, or carry luggage to meet those sensory needs. For example, they can be the “official suitcase helper” when moving through a shelter, hotel, or relative’s home, turning a potential challenge into a purposeful and regulated activity.

Grounding breathwork is another great option for sensory seekers who need help slowing down and centering themselves. Something as simple as packing bubbles can provide a calming outlet while encouraging deep, controlled breathing. Blowing bubbles is engaging and naturally slows their breathing, promoting relaxation.

It's important for children who are oral seekers to have safe, appropriate options. Whether it’s chewing gum, a favorite snack, or oral motor tools designed for sensory input, packing these items can make a big difference in helping them self-regulate. Consider what has worked at home or in other familiar settings and ensure these tools are included.

The key with sensory seekers is to anticipate their needs and find ways to incorporate movement, touch, or oral input into the environment they’ll be navigating. By planning ahead and packing thoughtfully, we can help them feel supported and more in control, even in the midst of unfamiliar and stressful circumstances.

Praxis

Let’s take a moment to focus on praxis needs. While sensory modulation tends to get a lot of attention, praxis needs are just as important to address, especially for children who struggle with motor planning and execution.

For example, if a child is prone to bumping into things and breaking them, we return to the simple yet effective solution: putting the fine china away. It’s a practical adjustment that can save the child and the family from unnecessary stress. Beyond that, we should think about packing activities or items that are low demand—things the child can engage with successfully in a high-stress environment, such as a shelter. For a parent thinking, How am I going to keep this child entertained in a shelter for three days?—the key is to pack activities that are familiar, calming, and require minimal instruction or effort.

And here’s where we revisit the habilitation versus adaptation lens. As much as it pains me as an OT to say this, an evacuation might not be the time to use packing as a teachable moment. Packing a bag is a big praxis task involving motor planning, sequencing, and execution. We might work on this skill during therapy or in calmer times, but when stress levels are high, it’s often better for caregivers to take on this task to avoid additional challenges.

For children who are prone to bumps and bruises, it’s a great idea to pack a "TLC kit." Include band-aids, antiseptic wipes, or any comfort items that help soothe minor injuries. When a family is out of their normal environment, the likelihood of small accidents increases, and having these items on hand can help mitigate the stress.

Finally, I want to circle back to feeding and communication needs, as these can often become the most significant barriers during an evacuation. For a child with a very limited diet, the thought of evacuating to a place where they can’t eat can feel overwhelming for both the child and their parents. Evacuations are unpredictable—we often don’t know how long they’ll last. It might be two days a week or longer. In some cases, families might not have a home to return to. These unknowns add a layer of stress, and ensuring that a child’s feeding needs are met can make the difference between whether a family decides to evacuate.

Communication is another essential consideration. If a child uses AAC devices or other tools to communicate, those need to be part of the packing plan. Without these critical supports, the child may be unable to express their needs effectively, adding further stress to an already challenging situation.

The bottom line is that by thoughtfully addressing praxis, feeding, and communication needs, we reduce the risk of these factors becoming barriers and instead help families feel more prepared, confident, and supported during an evacuation.

Feeding and Communication Needs

Talking about feeding and communication needs is absolutely essential, and I agree it warrants extra attention. These are foundational aspects of a child’s well-being, especially in a high-stress situation like an evacuation.

As discussed, feeding needs can easily become a significant family barrier. A child’s eating ability can directly influence whether a family decides to evacuate or stay in place. Packing enough of the child’s preferred or safe foods is critical, especially when we consider the uncertainty of how long an evacuation might last. The last thing we want is for a parent to worry that their child won’t eat in an unfamiliar environment, adding to the stress of an already difficult situation.

Equally important are communication needs. While not always sensory-related, communication challenges often overlap with sensory processing differences. And no matter the overlap, communication is a human right. Every child deserves the ability to express their needs, preferences, and feelings, particularly during a natural disaster when routines and environments are disrupted.

Families should add communication devices and supports—whether an AAC device, picture cards, or other tools—to their packing list. It doesn’t matter if they don’t perfectly fit into the sensory framework we’ve been discussing; these devices are critical. In the rush of packing and evacuation, it’s easy to forget something so essential, which is why it’s worth emphasizing.

Additionally, it’s a great idea to collaborate with a SLP to prepare for these scenarios. Families might need to add evacuation-specific words or phrases to their child’s AAC device or communication system, such as “Where is the bathroom?” “I’m scared,” or “I need help.” Ensuring these tools are ready and tailored to the situation can make a huge difference in reducing frustration and ensuring the child’s needs are met.

Considering Well-Being

Before we jump into a case study, I want to take a moment to emphasize the importance of considering overall well-being. While much of our focus has been on saving lives and ensuring survival, it’s equally important to consider what we can do to help families be well during these challenging times. Survival is the baseline, but we also want to put measures in place that make the experience easier and less overwhelming for both the kids and their families.

This means thinking beyond just the essentials and asking: What can we do to support emotional and mental well-being? What small steps or adjustments can we make to ease the burden on these families? By addressing these questions, we can provide families with the tools to survive and maintain a sense of balance and dignity during an inherently stressful situation.

With that in mind, let’s dive into a case study. This will allow us to apply what we’ve been discussing, see how these strategies work in practice, and explore how we can tailor solutions to meet individual needs. I want to leave enough time for this discussion and your questions at the end, so let’s begin.

Case Study

For today’s case study, let’s explore one specific example of the many we could consider. We’re looking at a four-year-old boy from a family with two parents, three kids, and two grandparents. This child is a sensory seeker—always on the move, climbing, crashing, and seeking intense movement. The parents have implemented a successful home program with heavy work, intense movement activities, and breathing exercises, which have been incredibly regulating for him. However, despite this progress, they still struggle to engage him successfully in public spaces. This is the typical progression: clinic to home, perhaps to school, but those community pieces often come later in the journey.

Now, let’s use the planner. Step 1: Identify his characteristics. This child is sensory-seeking for touch, proprioceptive, and vestibular information. He does not have any identified praxis or movement coordination challenges. Step 2: Identify the likely evacuation location. The family is planning to evacuate to a hotel.

With those details in mind, let’s move to Step 3: Potential challenges. What challenges do you foresee for this child in a hotel setting? Some great ideas are already coming in (from the live event):

- Limited space: A small hotel room with four adults and three kids offers few movement opportunities.

- The car ride: Long car rides can be tough for sensory seekers who crave movement.

- Unsafe-seeking behaviors: Jumping off beds or climbing furniture could be risky in a confined space.

- Sleep challenges: If the child’s sensory needs aren’t met, everyone’s sleep will likely be affected, increasing family stress.

- New environment: Unfamiliar surroundings can be disorienting and dysregulating.

I’ve noted some of these challenges and will reflect on a few here. Limited movement opportunities, unsafe-seeking behaviors, and sleep challenges are top concerns. Now, let’s move to Step 4: Strategies and Solutions.

What can we do to meet this child’s needs in this space? Some fantastic ideas have already come through:

- Noise machine: Helps everyone get better sleep by masking unfamiliar sounds.

- A hotel with a pool is a great way to provide sensory input and burn energy. Add swimsuits to the packing list!

- Preferred gross motor activities: Think of jumping, climbing stairs, or other simple ways to incorporate movement.

- Using the environment creatively: One of my favorite strategies is having the child push and pull a heavy suitcase down the hotel hallway. This provides heavy work and makes use of the long hallways. Adding a goal, like completing a puzzle at the end of the task, adds structure and purpose.

And don’t forget to pack what’s crucial! If a puzzle or specific toy is part of the plan, ensure it’s on the packing list. You’re already demonstrating that you have the tools and creativity needed to address these challenges effectively. Keep brainstorming and sharing in the chat!

Summary

We will then wrap up this part of the presentation. Before we transition, I want to remind you that this evacuation planner is available for download as part of this course. I encourage you to use, share, and integrate it into your practice to support the families you work with. Additionally, this planner and other helpful resources are available at no cost on my website, which we’ll provide you at the end of the session.

If you would like to adapt this planner and concept for application, please do. Please feel free to reach out to me. My website and email are listed. You can reach out to me if you need any help. Safety is a human right.

Questions and Answers

I work with seniors in a memory care community. Do you have any tips or resources for helping those with dementia during an evacuation?

While I don’t have specific dementia-focused resources, there’s often an overlap between dementia care and sensory-based strategies. Some of the Sensory Safe Evacuation Planner principles might be adaptable for your population. If interested, please email me or visit my website to access the planner. I’d be happy to modify the language to make it more suitable for adults and respectful of your residents. For instance, we would avoid terms like "child" and "children" in this context.

Who is Amy Arnsten, and what is her research about?

Amy Arnsten is a researcher whose work focuses on executive functioning and the role of the prefrontal cortex during stress. Her research has provided phenomenal insights into how stress impacts our ability to think, plan, and problem-solve—key considerations during evacuations or other high-pressure situations.

Do you use this planner as a standard part of the OT evaluation process at your clinic?

I’ve started using it with some of my caseloads as I transition into a new clinic after moving with my military family. While it’s not yet a standard part of the evaluation process, I see a lot of potential for it to become one. You could incorporate it during evaluations if it fits your setting or introduce it after getting to know the family better in their natural environment. Another idea I’m working toward is organizing a Natural Disaster Evacuation Planning Week, where clinics could engage all clients in these discussions and complete the planner together.

Are there adaptations of this planner for adults with sensory processing needs or those in residential facilities?

Yes, an adult planner version is available on my website for free. It features the same framework but uses more age-appropriate language, such as "my sensory processing needs" and "my challenges." If you need additional tweaks to fit your population better or address specific needs, feel free to reach out, and I’d be happy to work with you to adapt the planner accordingly.

How can I access these planners?

All versions of the planners, including those tailored for different populations, are available for free on my website. You’re welcome to download them, use them, and share them as needed. Please contact me directly if you want a customized version for your specific population.

References

Please refer to the additional handout.

Citation

Hamlin-Pacheco, K. (2025). Creating a “sensory safe” evacuation plan. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5771. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com