Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Discharge Planning: Pediatric Acute Care Virtual Conference, presented by Julia Colman, OTD, OTR/L, BCP.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the unique needs of hospitalized pediatric patients and special considerations for the safe discharge of children from hospital settings.

- After this course, participants will be able to list specific family-centered interventions and interprofessional collaboration efforts to promote positive outcomes through hospital discharge and various transitions of care.

- After this course, participants will be able to apply evidence-based knowledge regarding discharge planning for optimized functional outcomes in pediatric acute care practice settings.

Introduction/Kids Are Not Just Little Adults

First, I'd like to emphasize that kids are not just little adults. When treating children in pediatric acute care settings, we must remember their unique needs and considerations. While we will cover standard discharge considerations common across the lifespan, we must focus on children's special needs.

In adult practice settings, there are more defined transition guidelines, specific assessments for levels of independence, and clear protocols for what OT should do to assess safety for home discharge and the trajectory of care from the hospital to subacute settings to the home. However, we have fewer tools and less clear discharge guidelines in pediatric settings.

Many times, it's assumed that children will transition home with parents or caregivers, and the support will be there. This assumption can lead to overlooking children's unique safety needs and not ensuring that families feel fully prepared. Additionally, the regulations and guidelines for discharge documentation and requirements can differ due to the different payer sources in pediatric and adult settings.

It's crucial to address these gaps by thoroughly considering the unique needs of children and ensuring that families are well-prepared and supported throughout the discharge process.

Transitions of Care

What is a transition of care? Transitions of care refer to any patient movement from one care setting to another. It involves the transfer of responsibility from one healthcare provider to another. In pediatric acute care, this transition often involves moving from hospital medical staff to community settings, such as primary care physicians or various community organizations. These providers take over the responsibility for the child’s rehabilitation needs after discharge from the hospital.

Even if children are discharged to home, their healthcare needs often transition from one provider to another. This can include a variety of community-based resources, ensuring that the child's care continues seamlessly outside the hospital. We'll discuss different discharge dispositions later in this presentation, but it's important to understand that these transitions of care are critical for maintaining continuity and quality of care for pediatric patients.

Standard Discharge Considerations

- Across the lifespan, improved outcomes when patients are active participants in care & there is effective communication with families (Bucknall et al., 2020).

- Patient as a consumer (transparency in options, cost)

- Positive patient report- discharge planning and preparation from all team members, firmly established care continuity plan, and emotional support (Gotlib Conn, 2018).

- Negative factors impacting discharge quality- pressure to leave hospital, imposed transfer or discharge decisions, sub-optimal communication (Gotlib Conn, 2018).

- Patients perceive that discharge decisions were made without them (Bucknall et al., 2020).

- Insurance- Reimbursement often guides where they can go

- Baseline/change in status, home set up, caregiver availability, equipment needs, client and family values and goals

What are the standard discharge considerations? Across the lifespan, improved outcomes are demonstrated when patients are active participants in their care and when there is effective communication with families. Numerous studies consistently show that communication and collaboration with patients and families are key factors. The patient is the consumer, so transparency about options and the costs associated with them is crucial during these conversations.

Positive patient feedback is given when there is discharge planning and preparation involving all team members. This underscores the importance of interprofessional collaboration, ensuring that everyone is on the same page and that there is a firmly established care continuity plan. It involves identifying community support people after discharge and ensuring connections with all necessary team members.

Negative factors impacting discharge quality across the lifespan include pressure to leave the hospital, imposed transfer or discharge decisions made without patient participation, and suboptimal communication. Patients often feel that discharge decisions are made without input, highlighting a significant issue in patient perception.

In the context of our healthcare system, reimbursement often guides where people can go, which is an important consideration for occupational therapy practitioners. We must realistically evaluate what options are available and consider factors such as baseline and change in status, home and caregiver availability, equipment needs, and the client's and family's values and goals. These considerations apply across the lifespan, from infants to older adults.

Overall, a significant issue is that discharge decisions are often made by health professionals without consulting patients and families, which can negatively impact the quality of discharge and patient satisfaction.

Ethical Issues: Autonomy vs. Non-Maleficence

As occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs), we must balance two ethical principles: autonomy and non-maleficence. This means figuring out how to respect the informed choices of individuals and families while also protecting them from harm. Involving clients and families in discharge requires clear communication to understand their values and priorities. It also involves providing transparent and clear education about their options and the associated risks. This way, clients can make informed choices about their care.

To achieve this balance, we must engage in open and honest conversations with clients and their families to understand their values and needs. This helps ensure that their perspectives are considered in the decision-making process. Providing comprehensive information about the options available, including potential risks and benefits, is essential. This includes discussing the practical implications of different choices and any financial considerations. Allowing clients and families to participate actively in their care decisions involves respecting their autonomy while providing professional guidance to ensure their safety.

By following these steps, we can help clients and families make well-informed decisions that align with their values and needs, ensuring a safe and effective discharge process.

Family-Centered Care

- Patient and family participation in the care and discharge planning process has a positive influence on patient outcomes, satisfaction, risk of adverse events, and readmission rates (Bucknall et al., 2020).

- Families reported improved satisfaction when they had the opportunity to meet with OT/PT before discharge (Bucknall et al., 2020).

- Trauma-informed- A study found at least ⅓ of families experience post-traumatic stress symptoms following an acute pediatric critical illness admission (Riley et al., 2021).

In pediatrics, considering all of these factors means we need to provide family-centered care, which involves patient and family participation in the discharge planning process. Studies consistently show that this approach positively influences patient outcomes, satisfaction, the risk of adverse events, and readmission rates. Families also report improved satisfaction when they have the opportunity to meet with OT and PT before discharge.

As OTPs, we should keep this in mind when developing our care plans. Even if we determine that a patient doesn't need additional follow-up, it can be beneficial to arrange a one-time follow-up right before discharge. This ensures all questions are answered and families feel confident and comfortable with the discharge plan. Providing this level of support helps families feel more prepared and reassured, ultimately contributing to better overall outcomes.

Specific Trauma-Informed OT Interventions

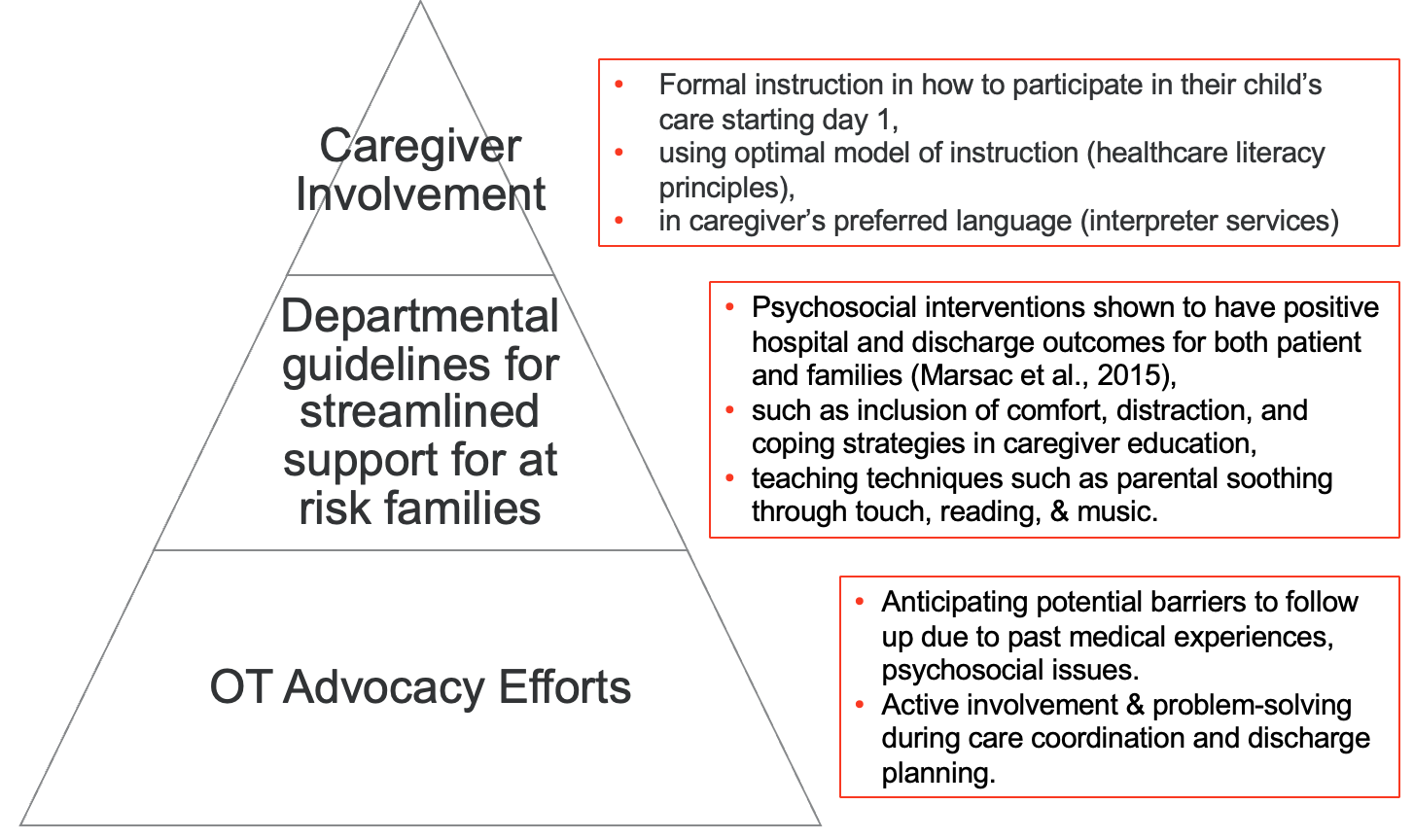

This also means that we are being trauma-informed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trauma-informed OT interventions (Click here to enlarge the image).

A study found that at least one-third of families experience post-traumatic stress symptoms following an acute pediatric critical illness admission. We often overlook the psychological implications for families and patients in acute care settings. Providing trauma-informed care can minimize the potential for medical care to become a traumatic or triggering experience. Addressing distress, providing emotional support, offering positive coping strategies, and giving anticipatory guidance all support the recovery process and improve discharge outcomes.

This approach requires careful consideration of timing when providing patient and family education. It's essential not to give education immediately after a family receives distressing news, as they are unlikely to be in a state to learn effectively. Clear communication within the team is crucial to identify the best times for education. It is necessary to validate and recognize the emotional impact on patients and families to understand how it might affect their receptiveness to caregiver education. It may take multiple sessions to deliver the necessary education effectively due to the emotional state of the families.

Specific trauma-informed OT interventions can be applied at every level of care. At a systemic level, OT advocacy efforts should anticipate potential barriers to follow-up, considering past medical experiences that might impact compliance with recommendations for outpatient follow-up or community-based resources. Recognizing psychosocial issues that can create barriers to follow-up is essential, and OTPs can advocate and provide support in this realm. Active problem-solving during care coordination and discharge planning is vital.

Guidelines for streamlined support should be established at the departmental level, especially for at-risk families. Psychosocial interventions have been shown to improve hospital and discharge outcomes for both patients and families. OTPs are well-equipped to provide these interventions, including comfort, distraction, and coping strategies as part of caregiver education. Techniques such as parental soothing, therapeutic touch, reading, and music can facilitate caregiver involvement in their child's care throughout the hospital stay.

Caregiver involvement from day one is crucial. Starting immediately, formal instruction on participating in their child's care is important. In acute care settings, healthcare providers often take over tasks such as changing diapers and soothing the child when families may not realize they can and should be involved. Involving caregivers in these aspects of care from the beginning helps them feel more connected and effective in supporting their children.

Using optimal instructional models, considering healthcare literacy principles, and always providing education in the caregiver's preferred language using interpreter services are essential for being trauma-informed and client—and family-centered. This approach ensures that families are well-supported, informed, and actively involved in their child's care and recovery process.

Evaluation Process: When Does Discharge Planning Begin?

- What must be included in a pediatric acute care evaluation for optimal discharge planning?

- Knowledge of conditions- change in status, common care trajectory

- Home set up (including all relevant homes)

- Caregiver availability

- Current equipment, equipment needs

- Patient and family values, goals

- Anticipated discharge disposition

- Patient-centered, occupation-focused goals

Thinking back to the OT evaluation process, when does discharge planning begin? According to our OT practice framework, discharge planning should start during the initial evaluation. This is crucial because it impacts what is included in our evaluation documentation and what is built into our EHR/EMR systems. Here are some key elements that should be included in that initial OT evaluation to optimize discharge planning.

First, we must have knowledge of conditions and what we can expect regarding changes in status and the common care trajectory. When we receive a referral to evaluate a child in acute care, we need to understand the expected course of the hospital admission, including the typical length of stay, anticipated changes in status, pain levels, and common side effects of the condition or treatment. This knowledge is essential for effective discharge planning.

Second, we must talk with families about the home setup, including all relevant homes. Unlike in adult settings, children may spend time in multiple homes due to shared parenting arrangements or time spent with other family members, such as grandparents. Understanding the different environments the child will need to access after discharge is crucial for comprehensive planning.

Third, we need to assess caregiver availability and capacity. This includes understanding whether a caregiver will be present and their physical ability to perform necessary tasks, such as transfers. We should also consider whether the caregiver has other responsibilities, like caring for siblings, that might impact their availability and capacity.

Fourth, we need to discuss current equipment and equipment needs. It’s important to know what equipment the family already has at home to avoid unnecessary recommendations and to identify any additional equipment that may be required.

Fifth, we must understand patient and family values and goals. Families may have different expectations regarding the child’s independence based on cultural norms and personal values. It's essential to align our discharge recommendations with these expectations and consider the role of siblings as caregivers in some families.

Sixth, we need to anticipate the discharge disposition. We should consider whether the child will be leaving the hospital with new needs they didn’t have before admission or if they are expected to return close to their baseline level of performance and participation. Understanding where they are discharging to is also important.

Lastly, we must set patient-centered and occupation-focused goals. Even in an acute care setting, where the focus is on medical stability and safety, our goals should remain occupation-focused. This means considering the child's everyday activities and ensuring that our interventions and recommendations support their ability to participate in those activities.

By incorporating these elements into the initial OT evaluation, we can ensure that discharge planning is comprehensive and effectively supports the child's transition from hospital to home or other settings.

Pediatric Acute Care Discharge Considerations

- Medical complexities; changes to caregiver roles and routines

- Often require coordinated, multispecialty follow-up

- Developmental surveillance and monitoring; anticipated growth; return to school

- Complex social situations; psychosocial considerations; history with healthcare system

- Consideration of family and community resources

- Geographical location- proximity to the hospital

Connors, Havranek, & Campbell, 2021

Specific pediatric acute care discharge considerations differ significantly from those in adult practice settings. When a child experiences a significant change from their baseline status or faces medical complexities, it substantially changes caregiver roles and routines. Caregivers may have other responsibilities outside of caring for the child, and while caring for the child may be their primary focus, they still need to manage other aspects of their lives. Recognizing this, we must be mindful of where families are coping and grieving with the changes in their lives. Overloading them with recommendations can be overwhelming, so understanding their emotional state is crucial.

Pediatric discharge often requires coordinated multi-specialty follow-up. Children with medical complexities involve numerous team members, necessitating clear communication and coordination among all parties involved. Engaging in developmental surveillance and monitoring is essential in pediatric care. Even if a child is admitted for reasons unrelated to developmental progression, Occupational Therapists need to identify deviations from expected development and provide appropriate recommendations.

Anticipated growth is another critical factor. Unlike adults, children will outgrow equipment such as splints or orthotics, requiring follow-up to ensure these items remain appropriate as they grow. Additionally, we need to consider the child's return to school and ensure they have the necessary support and resources to transition back safely after hospitalization.

Complex social situations are common in pediatric settings. Children may have multiple homes due to shared parenting arrangements, and other psychosocial considerations must be considered. Families with a history of extensive medical interactions often develop mistrust in the healthcare system. Approaching these families with sensitivity and understanding their advocacy history is vital. Knowledge of custody arrangements and who is allowed at the bedside is also important. Occupational Therapists need to know where to access this information in the chart and who to contact on the team for any questions about discharge plans.

Family and community resources should be considered when making discharge recommendations. The hospital setting should be a bridge to community resources, providing families with contacts and connections to continue care outside the hospital.

Geographical location and proximity to the hospital are significant considerations, especially since specialized pediatric hospitals in a state may be few and far between. Families may travel long distances for care, making returning to the same facility for outpatient therapy impractical. Establishing connections with outpatient clinics throughout the state is essential to ensure continuity of care.

Potential Discharge Disposition

- Parents, family, group home, foster care

- Home

- With referral to specialty clinics, outpatient, school-based, home health, EI, DDD

- Transfer or in-house length of stay

- Inpatient rehabilitation

- Medical home, residential treatment

- Long-term care facility

With follow-up services, this leads to the potential discharge disposition. Families or children may be discharged to their parents, to home with their family, or they may be discharged to a group home or foster care. When providing education, we must consider the discharge destination and tailor our approach accordingly. It's essential to think about necessary referrals, such as specialty clinics within the healthcare system, that might be appropriate for the child but haven't yet been connected with them.

Connecting families with outpatient services, school-based services, home health, early intervention, and Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD) resources is crucial. Children may need to connect with numerous potential resources and partners after discharge. Identifying the most appropriate resources begins at the initial evaluation and must be included in the discharge plan.

Children may transfer from one unit to another, from acute care to inpatient rehabilitation. This rehabilitation can be within the same facility or at another location. Considering the length of stay at our facility and the approval for the next step in inpatient rehabilitation is essential. Documentation needs to be specific for potential inpatient rehab candidates, adhering to the guidelines for admission in pediatric settings. Acute care therapists must communicate effectively with inpatient rehabilitation teams and understand the documentation requirements.

Children might also be discharged to home, a residential treatment facility, or a long-term care facility. It is crucial to provide appropriate training, such as ADL, equipment, and transfer training, to the staff at these facilities. Ensuring a smooth transition is also important, especially if children are not discharged to home, or caregivers are not at the bedside.

One is the Wi FIM, the pediatric version of the functional independence measure. That's where we assess levels of independence in activities of daily living. But when we're talking about kids, a lot of times, especially for our younger pediatric patients, there isn't an expectation developmentally that they would be independent in ADLs. Often, the question isn't, can the child participate in these ADLs independently? It's more about whether the caregiver feels comfortable assisting them with these ADLs, assisting them with functional transfers, and engaging them with age-appropriate developmental play. Do they feel comfortable with all of that after discharge?

Another measure we have is the PD CAT, which will also look at participation in various daily activities. It goes a bit more in-depth than the Wi FIM, which is just ADLs, but it still isn't giving us everything we need to know regarding the child's ability to safely discharge. We also, a lot of times, rely on skilled observation. Many of my acute care evaluation and discharge recommendations are made based on having in-depth conversations with caregivers. But again, they're not always available at the bedside. There are a lot of barriers to parents and caregivers being present. They have jobs as well. They have other kids to care for. A lot of times, siblings are not allowed at the bedside in children's hospitals.

So these are major barriers. But if they are available, having those conversations is really helpful in discharge planning and that skilled observation piece.

Parent Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale (PedRHDS)

- Provides outcome metrics for hospital care & risk indicators for post-discharge coping difficulty and readmission (Weiss et al., 2020).

- Caregiver readiness for discharge should be assessed at admissions and before discharge to allow for timely education and training by the interdisciplinary team.

- The PedRHDS is recommended in acute rehabilitation settings by OTPs.

However, a new measure, the parent readiness for hospital discharge scale, or the PedRHDs, examines the family experience's key variables further.

This looks at aspects of the discharge transition that differ from the disease. It examines things like health status, patient demographics, and some social determinant parameters typically used in risk prediction models for safe discharge to home. However, it focuses more on the psychosocial aspect of discharge planning and caregiver readiness.

While the Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM), the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI), and skilled observations are extremely valuable tools, they should be used in collaboration with something like the PedRHDs, which also evaluate family readiness.

5 dimensions of Parental Readiness | ||||

Personal status-parent | Personal status- child | Knowledge | Coping Ability | Expected support |

The five different dimensions assessed by this questionnaire include the personal status of the parent, the personal status of the child, knowledge (the family and child's understanding of post-discharge care), their coping ability (considering that many children have experienced traumatic or acute events), and the expected support.

This contextually important aspect includes the difference between a family taking a child home with minimal social support versus one with ample support, where caregivers can trade off care and have time for respite. It's crucial to consider expected support when planning a pediatric discharge. This scale provides outcome metrics for hospital care and risk indicators for post-discharge coping difficulty and readmission. Discharging from the hospital before readiness often leads to high readmission rates and negative quality improvement outcomes.

Implementing this scale into the team's discharge planning can help reduce readmission rates. Caregiver readiness for discharge should be assessed both at admission and before discharge. This allows time for timely education and training by the interdisciplinary team. This proactive approach prevents last-minute training and education when caregivers are stressed about transportation, medication, and other discharge details. Early assessment of discharge needs and incorporating parent readiness conversations ensure adequate time for comprehensive education without the rush of last-day preparations.

The PedRHDs is recommended in acute rehabilitation settings by Occupational Therapists. Studies show that this can be helpful for acute care therapists and inpatient rehabilitation teams in determining readiness for families when it comes to the hospital discharge of children.

Barriers

- Family availability for training and education during therapist work hours

- work

- transportation

- other caregiving responsibilities

- Organizational pressure to discharge

- Focus on logistics vs. psychological family support (Bucknall et al., 2020)

- Segmentation of care

- roles/responsibilities divided between departments →

- diffusion of responsibility

- lack of coordinated efforts between departments

There are unique barriers in pediatric discharge planning that aren't as prevalent in adult settings. One significant barrier is the limited availability of families for training and education. Since our therapists work during standard hours, which overlap with families' work hours, families often can't be present for crucial training. This issue calls for a potential shift in staffing and working hours for our inpatient OT teams. Other providers often work on more variable shifts, so there may be room to discuss implementing similar schedules for OT acute care therapists. This way, we can provide family training and education during evenings when families are more likely to be available at the bedside.

Transportation barriers are another critical issue. Children's hospitals are frequently far from where families live and work, making it challenging for them to visit regularly. This difficulty is exacerbated by a lack of resources for transportation. Additionally, caregivers often have other responsibilities, such as caring for siblings who may not be allowed at the hospital. To address this, hospitals could consider providing access to childcare, enabling caregivers to visit and receive necessary training and education without worrying about their other children.

Organizational pressure to discharge quickly is a substantial barrier. The healthcare system's trend emphasizes quicker discharges to improve outcomes measures. However, this pressure can hinder family-centered care and prevent adequately involving families in discharge planning decisions. This focus on rapid discharge overlooks the importance of ensuring families are truly ready to care for their children at home.

Another barrier is the focus on logistics at the expense of psychological family support. While ensuring medical stability, pain management, adaptive dressing techniques, and safe transfers are crucial, we often miss addressing the psychological support families need. Completing the checklist of necessary medical tasks is insufficient if the family isn't receptive or confident in carrying out the care independently. Providing psychological support is essential for families to feel comfortable and safe with the discharge recommendations.

The segmentation of responsibilities between different departments also presents a barrier. This diffusion of responsibility can lead to a lack of coordinated efforts. For example, while OTs may recommend discharge equipment, they are not always responsible for ordering it. Discharge planners handle this through home care services. Consequently, OTs might not know the specifics of the equipment provided or whether it is covered by the family's insurance. This lack of coordination can impact discharge recommendations and the overall effectiveness of the discharge plan.

In summary, addressing these barriers requires a more flexible approach to staffing and working hours, better transportation solutions and childcare support for families, shifting from organizational pressures towards more family-centered care, and improved coordination between departments. By tackling these issues, we can ensure that discharge planning in pediatric care is comprehensive, supportive, and effective.

Key Players in Discharge Care Coordination

Key Players in Discharge Care Coordination | |

Parents, Family, Caregivers •# team member | Pharmacy •Medications, formulas, tube feeding/nutrition |

Acute care team •Medical team (including OT), discharge planner/care coordinator | Payor sources •Managed care, private insurance, Medicaid |

Primary Care •OT? | DME & orthotics companies •Orthotics, helmets, bath equipment, wheelchairs, etc. |

Specialty follow-up clinics •Neurodevelopment specialist, rehab team- including OT | Schools •Therapy services, 504 plan, IEP, nursing |

Early Intervention •PT, OT, SLP, Vision & Hearing, Psychosocial, and Assistive Devices | Community resources •DDD, Home Health Agencies, WIC, CPS- case management, parent/sibling support, mental health services, financial/food/housing assistance, transportation |

There are many key players in discharge care coordination, and communication among them is critical. The family, patient, parents, and caregivers are the team's most important members. Following them, the entire acute care medical team plays a vital role, including occupational therapists, discharge planners, and care coordinators. These roles might have different names at various facilities, but they coordinate all discharge efforts.

Often overlooked, the primary care team should be connected with the acute care team to ensure a smooth transition from hospital to home. Specialty follow-up clinics, neurodevelopmental specialists, and the inpatient rehab team also play crucial roles. Communication between these specialists and acute care OTPs can streamline documentation and planning, making the transition smoother for the patient and ensuring better outcomes.

Early intervention teams, including PTs, OTPs, speech-language pathologists, and vision and hearing specialists, should be engaged early. Starting evaluations and screenings during the hospital stay can help families initiate processes and get support while still under hospital care. Pharmacy teams are also crucial due to the complexity of medication management, formulas, tube feedings, and nutrition education. Coordinating education sessions with the pharmacy and home care teams at different times can prevent overwhelming families on discharge day.

Payer sources such as managed care, private insurance, and Medicaid impact discharge recommendations. For example, knowing whether a patient's insurance covers specific equipment like a bedside commode is vital. Developing relationships with durable medical equipment and orthotics companies can facilitate evaluations and equipment provision while the patient is still inpatient.

Schools are another important consideration. Recommendations should include school therapy services, 504 plans, IEP evaluations, special education evaluations, or nursing needs. The acute care team must discuss these needs with families to ensure appropriate support post-discharge.

Community resources, including DDD, home health agencies, WIC, and CPS, should be considered. If CPS is involved, providing psychosocial and psychological support is crucial. Sibling support, including involving siblings in transfer and caregiver training, is also important since siblings often act as caregivers. Connecting families with mental health services, financial aid, food, and housing assistance is essential. As described in Maslow's hierarchy, meeting these basic needs is necessary for optimal outcomes.

One example highlighting the importance of considering the big picture is a case where a therapist recommended a tub transfer bench for a child living in a homeless shelter. This recommendation was inappropriate given the child's living situation and need for safe transfers in and out of a car. This situation underscores the necessity of considering all logistical barriers and the context of the patient's living conditions when making discharge recommendations.

To address these barriers, adopting a more flexible approach to staffing and working hours is essential, improving transportation solutions and childcare support for families, shifting from organizational pressures toward more family-centered care, and enhancing coordination between departments. We can ensure comprehensive, supportive, and effective discharge planning in pediatric care by addressing these issues.

Interprofessional Collaboration

Interprofessional Collaboration |

Clear Communication •Poor communication is the main cause of poor discharge planning and negative outcomes (Lobchuk et al., 2020) •Effective documentation |

Occupational Therapy Participation in Daily Rounds •Meet with interprofessional team to identify and assess goals, plan, coordinate, and evaluate patient discharge plans (Lobchuk et al., 2020) •Optimized timing and safety of discharge (Lobchuk et al., 2020); ensures OT discharge and equipment recommendations are considered •Many formats- may be weekly or daily •OTs should be participating in all aspects of discharge planning (Ragni et al., 2021) |

Interprofessional Empathy •Decline in empathy over time in healthcare professionals, including OTs. •Negatively impacted by compassion fatigue, burnout, excess demand, & unreasonable productivity requirements. |

Interprofessional collaboration is extremely important; clear communication is the number one way to ensure positive discharge outcomes. Poor communication is the main cause of poor discharge planning and negative outcomes in acute care settings. This means communication isn't just face-to-face with different providers or families and clear communication in our documentation.

Occupational therapy practitioners should participate in daily rounds. How can we communicate effectively with other interprofessional team members if we're not participating at that level? Participating in daily rounds allows us to meet with the team to identify and assess goals and plan, coordinate, and evaluate patient discharge plans. This helps optimize the timing and safety of discharge and ensures that OT discharge and equipment recommendations are considered by the medical team.

Effective documentation is crucial, but we know that not every line of our documentation is always read. By participating in rounds, we can ensure our recommendations are heard. There are various formats for conducting rounds, and while daily participation may be logistically challenging, starting with weekly participation could be a feasible solution. Finding a format that works within your hospital's structure is important to ensure the team can communicate and collaborate effectively.

OTs should be involved in all aspects of discharge planning, not just ADL techniques, precautions, and equipment training. Our role is much larger, and we must ensure we encompass the full scope of our practice in pediatric acute care. Interprofessional empathy is also critical. It's known that empathy declines over time among healthcare professionals, including occupational therapists. This decline is often negatively impacted by compassion fatigue, burnout, excess demand, and unreasonable productivity requirements.

We should consider reducing factors contributing to fatigue and burnout at the department level. Adjustments to productivity requirements should focus on positive patient outcomes rather than on how many patients can be seen and how quickly. By prioritizing quality care and supporting the well-being of our healthcare professionals, we can maintain empathy and provide better care to our patients.

In summary, the key to effective discharge planning and positive outcomes in pediatric acute care is strong interprofessional collaboration, clear communication, active participation in rounds, comprehensive discharge planning, and addressing factors contributing to professional fatigue and burnout. Focusing on these areas can improve the discharge process and ensure better outcomes for our patients and their families.

Case Example: Baby Bridge Program

Case Example: Baby Bridge Program | |

The Baby Bridge program: A sustainable program that can improve therapy service delivery for preterm infants following NICU discharge (Pineda et al., 2020) | Is there a cost-effective method for improving continuity of care in pediatric populations?

*Program achieved sustainability within 16 months of implementation.

|

Methods: •Developed to promote timely, consistent and high-quality early therapy services for high-risk infants following neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) discharge. •Key features of the Baby Bridge program were defined as: 1)having the therapist establish rapport with the family while in the NICU, 2)scheduling the first home visit within one week of discharge and continuing weekly visits until other services commence, 3)conducting comprehensive assessments to inform targeted interventions by a skilled, single provider and 4)using a comprehensive therapeutic approach while collaborating with the NICU medical team and community therapy providers. | |

To conclude, I would like to provide a case example of a program excelling in bridging the gap between hospital discharge and community support: the Baby Bridge program. This sustainable program facilitates therapy service delivery for preterm infants following NICU discharge. While the NICU setting is specific, it shares similarities with acute care regarding the need for seamless transitions from hospital to community settings.

The Baby Bridge program developed a method to provide timely, consistent, and high-quality early therapy services to high-risk infants. After infants were discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit, they were connected with their community early intervention supports. The key features of this program included therapists establishing rapport with the family while the infant was still in the NICU. This translates to building clear and trusting relationships early during the patient's stay in acute care.

The program scheduled the first home visit within one week of discharge and continued these weekly visits until other services commenced. This approach bridged the gap between hospital discharge and the initiation of early intervention services, addressing the long waitlists for outpatient clinics and the lengthy process of early intervention program initiation. By doing so, the program prevented losing children to follow-up.

Therapists conducted comprehensive assessments to inform targeted interventions, which were provided by a skilled single provider. The program also used a comprehensive therapeutic approach while collaborating with the NICU medical team and community therapy providers. It emphasized the importance of building a strong relationship with the family.

As we conclude, consider whether there are cost-effective methods for improving continuity of care in pediatric populations. Often, discharge recommendations from acute care are non-specific, such as suggesting follow-up with outpatient services without confirming the availability of those services in the community where the patient is being discharged. Ensuring closer monitoring of care continuity and verifying the connection to services is crucial.

The Baby Bridge program achieved sustainability within 16 months of implementation, demonstrating that such programs are realistic and achievable. As occupational therapists, we must be creative and innovative in our approaches, tailored to our unique geographical locations and the specific feasibility within our environments. Implementing similar programs can significantly improve continuity of care and ensure better outcomes for pediatric patients transitioning from hospital to home and community settings.

Practical Takeaways

- Recognize that pediatric patients have unique needs when it comes to discharge compared to adults.

- Involve families in care and decision-making. OT sessions should be trauma-informed and heavily focused on caregiver training and education.

- Include parental readiness in evaluation & discharge decisions.

- Actively participate in interdisciplinary rounds.

- Program development that improves care coordination and smooth service transition from hospital to community.

Recognizing that pediatric patients have unique needs when it comes to discharge compared to adults is crucial. Here are some practical takeaways to ensure effective discharge planning and transition for pediatric patients:

Pediatric patients have unique needs when it comes to discharge compared to adults. Involving families in their care and decision-making is essential. OT sessions should be trauma-informed, focusing heavily on caregiver training and education. This includes incorporating parental readiness in both the evaluation and discharge decisions.

OTPs should actively participate in interdisciplinary rounds to ensure clear communication with the medical team. This helps in planning and coordinating discharge plans, optimizing the timing and safety of discharge, and ensuring that OT recommendations are integrated into the overall plan.

Engaging in program development that improves care coordination and facilitates smooth service transitions from hospital to community settings is also crucial. Programs like the Baby Bridge, which provide timely, consistent, and high-quality therapy services to high-risk infants post-NICU discharge, serve as excellent models. These programs emphasize early rapport building, timely follow-ups, and comprehensive support until community services are established, preventing children from being lost to follow-up.

Summary

Hopefully, you feel we have met the learning outcomes today. Thanks for joining us.

References

Bucknall, T. K., Hutchinson, A. M., Botti, M., McTier, L., Rawson, H., Hitch, D., ... & Chaboyer, W. (2020). Engaging patients and families in communication across transitions of care: An integrative review. Patient education and counseling, 103(6), 1104-1117.

Connors, J., Havranek, T., & Campbell, D. (2021). Discharge of medically complex infants and developmental follow-up. Pediatrics in review, 42(6), 316- 328.

Gotlib Conn, L., Zwaiman, A., DasGupta, T., Hales, B., Watamaniuk, A., & Nathens, A. B. (2018). Trauma patient discharge and care transition experiences: Identifying opportunities for quality improvement in trauma centres. Injury, 49(1), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2017.09.028

Lobchuk, M., Bell, A., Hoplock, L., & Lemoine, J. (2021). Interprofessional discharge team communication and empathy in discharge planning activities: A narrative review. Journal of interprofessional education & practice, 23, 100393.

Lori B. Ragni, Camille Velasco, Teresa Fitzsimons, Katie Shniderman (2021). Pediatric Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale (PedsRHDS): Use in Interdisciplinary Caregiver Training Program in Acute Inpatient Rehabilitation. Am J Occup Ther, 75(Supplement_2), 7512500053p1. doi: https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.75S2-RP53

Marsac, M. L., Kassam-Adams, N., Hildenbrand, A. K., Nicholls, E., Winston, F. K., Leff, S. S., & Fein, J. (2016). Implementing a Trauma-Informed Approach in Pediatric Health Care Networks. JAMA pediatrics, 170(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2206

Pineda, R., Heiny, E., Nellis, P., Smith, J., McGrath, J. M., Collins, M., & Barker, A. (2020). The Baby Bridge program: A sustainable program that can improve therapy service delivery for preterm infants following NICU discharge. PloS one, 15(5), e0233411.

Ragni, L. B., Velasco, C., Fitzsimons, T., & Shniderman, K. (2021). Pediatric readiness for hospital discharge scale (PedsRHDS): Use in interdisciplinary caregiver training program in acute inpatient rehabilitation. *American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75*(Supplement_2), 7512500053p1. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.75S2-RP53

Riley, A. R., Williams, C. N., Moyer, D., Bradbury, K., Leonard, S., Turner, E., ... & Hall, T. A. (2021). Parental posttraumatic stress symptoms in the context of pediatric post-intensive care syndrome: Impact on the family and opportunities for intervention. Clinical practice in pediatric psychology, 9(2), 156.

Weiss, M. E., Lerret, S. M., Sawin, K. J., & Schiffman, R. F. (2020). Parent readiness for hospital discharge scale: psychometrics and association with post-discharge outcomes. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 34(1), 30- 37.

Williams, C. N., Hall, T. A., Francoeur, C., Kurz, J., Rasmussen, L., Hartman, M. E., ... & PEDIATRIC NEUROCRITICAL CARE RESEARCH GROUP (PNCRG). (2022). Continuing care for critically ill children beyond hospital discharge: Current state of follow-up. Hospital pediatrics, 12(4), 359-393.

Citation

Colman, J. (2024). Discharge planning: Pediatric acute care virtual conference. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5716. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com.