Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, The Driver of Function: Postnatal Pelvic Health Virtual Conference, presented by Kyrsten Spurrier OTR/L, PCES, TIPHP.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify OT’s role in pelvic health to support occupation.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the function of the pelvic floor.

- After this course, participants will be able to list 3 categories of dysfunction of the pelvic floor.

Introduction

My name is Kirsten Spurrier, and I’m thrilled to be here with you today to discuss pelvic health, a topic that holds significant importance to me. We'll begin by exploring how pelvic health can be addressed across various settings.

Case Study

What is pelvic health? Let’s begin with a case study. A 35-year-old woman comes into my office at 20 weeks pregnant, reporting that she leaks urine when she sneezes. This is her second pregnancy, following a first delivery 18 months ago that involved hours of pushing, an emergency C-section, hemorrhaging, and a two-day ICU stay during her son’s early life.

Currently, she engages in Pilates three times a week, plays tennis twice a week, and works part-time training hunter-jumper horses imported from Europe for sale in the United States. Her job involves riding horses five days a week. She also mentions mid-back discomfort and shares that her husband travels frequently, leaving her to manage primarily as a single mom. In passing, she notes that intercourse is "fine" but not always comfortable.

The only issue she identifies as problematic in her situation is the irritation caused by leaking when sneezing. This highlights an important point: there is often a significant gap between how society or those unfamiliar with pelvic health perceive the field and what pelvic health truly encompasses. Today, we will explore the full scope of pelvic health and what it means for individuals like this client.

Definition

I like Baylor Health's definition: "Pelvic health is the best possible functioning and management of the bladder, bowel, and reproductive organs. It’s not merely the absence of disease or weakness in these organs. Pelvic health is critical for physical, mental, social, and sexual well-being." To me, occupational therapy is written all over it. Whether you realize it or not, as an occupational therapy practitioner (OTP), you consistently work with and support the pelvic floor in every individual you rehab. If you are helping someone recover from a stroke, working with a pediatric client on interoception, or assisting a post-ICU patient with energy conservation, you are impacting their pelvic floor. That is why I chose the title, the driver of function.

Before I began working in pelvic health, I was an ICU therapist, and medicine continues to amaze me. It can do incredible things for patients who are unable to function independently. If you ask most internal medicine doctors what they believe to be the most essential function, they would likely say breathing. It’s fundamental, and we’d all agree. But if you asked them what can cause a patient to deteriorate rapidly and turn septic overnight, they would probably respond with bladder and bowel elimination. While people can survive without movement or can live with the support of ventilators or ECMO, the inability to eliminate properly is often the tipping point for serious complications.

A retrospective study from 2016 to 2019 revealed that hospital stays increased by 3.4 days for patients with constipation, adding $31,762 to hospital costs and leading to higher ICU mortality rates. These findings highlight how pelvic floor function is foundational to survival and why it is critical to understand its role as a driver of function in any practice setting.

Returning to the case study, let’s examine where occupational therapy can make an impact by addressing the client’s needs through physical, mental, emotional, social, and sexual dimensions. You don’t need specialized training in pelvic health to work with this patient.

Physically, the client reports leaking, but we must determine the cause. Is it related to her breathing, strength, posture, or coordination between the diaphragm and pelvic floor? She is highly active, participating in Pilates, tennis, and horseback riding. Two of these activities demand significant pelvic floor reaction time. We should ask whether she leaks during these activities or only when sneezing. Her pregnancy shifts her center of gravity, so assessing how she compensates for this is essential. Her history of a C-section may also indicate scar tissue adhesions impacting her bladder. Additionally, her discomfort with intercourse might stem from physical factors like vaginal dryness, which can occur during pregnancy.

Mentally and emotionally, she doesn’t see herself as having major issues, but she has experienced significant birth trauma that remains unaddressed. Acting as a single parent much of the time has likely heightened her nervous system’s stress response. She scored over 50 on the Central Sensitization Inventory, indicating a high probability of central sensitivity syndrome, a group of diagnoses such as fibromyalgia, IBS, and chronic fatigue that are driven by the central nervous system. She hasn’t had the time or resources to process these challenges and isn’t currently seeing a therapist. Fertility struggles with her first pregnancy, and the rapid conception of her second adds another layer of complexity.

Socially, her life is tightly scheduled, and attending pelvic floor therapy is already a significant burden. She feels she has no choice but to keep going without a break. This is where we, as OTPs, can address roles and routines, helping her find more balance and prioritize self-care.

Sexually, she reports some discomfort but doesn’t view it as a high priority. It’s important to explore whether this discomfort arises from stress, desire, physical limitations, or a combination of factors. Understanding her perspective can help inform appropriate interventions.

This case demonstrates how occupational therapy’s holistic approach can make a meaningful difference in addressing pelvic health and integrating physical, emotional, social, and sexual considerations into a comprehensive care plan.

What is OT’s Role in Pelvic Health?

What is OT’s role in pelvic health? We play a significant role in this area, even if a client initially seeks pelvic floor therapy for what seems like one specific issue. Often, that single reason uncovers ten or more reasons why therapy can be beneficial. Clients may feel their situation doesn’t warrant the time or effort, and part of our role is to carefully show them how much can be addressed to improve their function and quality of life. Occupational therapy practitioners have the ability to make a profound impact on the trajectory of someone’s life, and pelvic health is no exception.

The OT Practice Framework continues to guide our profession, and addressing pelvic floor dysfunction doesn’t change that. It provides a clear structure for breaking down a patient’s situation. Every OTP, regardless of their current knowledge of pelvic health, can address at least one element of what we’ve discussed. This reinforces that pelvic health isn’t limited to a specific setting or specialty. We have an obligation to consider a person’s pelvic health in every practice area.

A qualitative study published in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy highlights the transformative impact of OT on pelvic health. The study found that occupational-based therapy changed the course of women’s journeys with pelvic health. Women experienced relief in symptoms and empowerment by becoming experts in their bodies. Significant improvements were observed, as measured by decreased symptoms on the Pelvic Floor Disability Index and increased quality of life after OT intervention.

This evidence underscores that OTPs belong in pelvic health-specific settings and bring a unique and essential perspective by linking pelvic health to overall function. Incorporating pelvic health into our therapist skill set is appropriate and necessary. As we move forward, let’s explore the anatomy and function of the pelvis in greater detail to deepen our understanding and refine our approach.

What is the Structure of the Pelvis?

What are the structures of the pelvis?

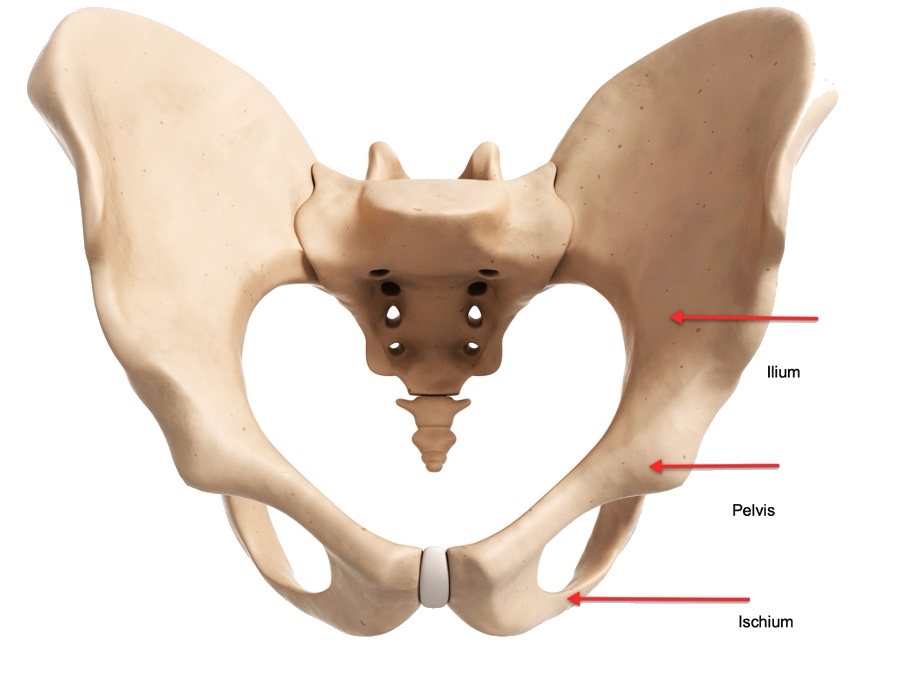

Figure 1. Pelvis structure.

For those who need a refresher, the pelvis has two parts. The anterior part, including the pelvic girdle, comprises the pubis, the ischium, and the ilium. The posterior part, which is the pelvic spine, comprises the coccyx and the sacrum. Sixteen muscles contribute to the pelvic floor.

Some of the muscles in the pelvic region are isolated to the pelvic space, while others extend into the abdomen, glutes, and lower back. For example, the piriformis is classified as a pelvic floor muscle but extends beyond the pelvic floor. The pelvic cavity is a storage space for critical structures, including the urinary bladder, pelvic colon, internal reproductive organs, and rectum.

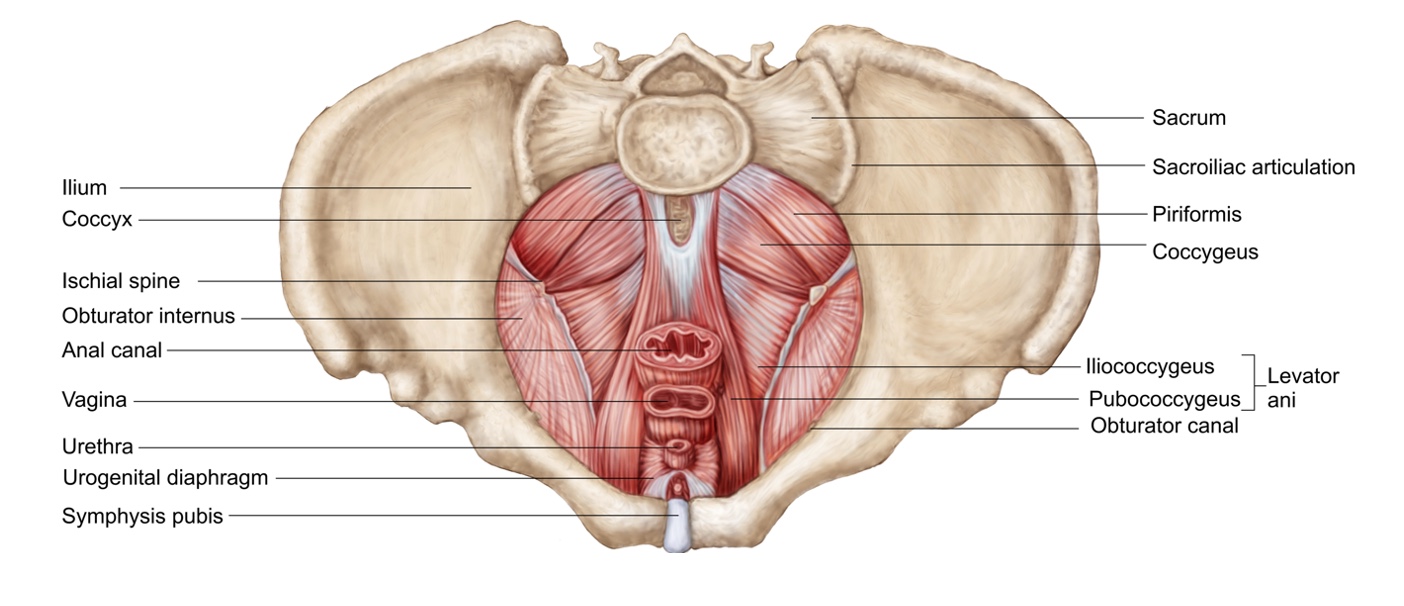

Within the pelvic floor, there are two openings: the urogenital hiatus, which consists of the urethra and the vaginal opening in female anatomy, and the rectal hiatus, which is the anal canal. You can see all three openings in the female anatomy diagram in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Superior view of the pelvic diaphragm. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

It’s important to emphasize that everyone has a pelvic floor, and it can be accessed in different ways: through the vaginal canal, the rectum, or externally. Internal work is not always necessary to positively impact the pelvic floor.

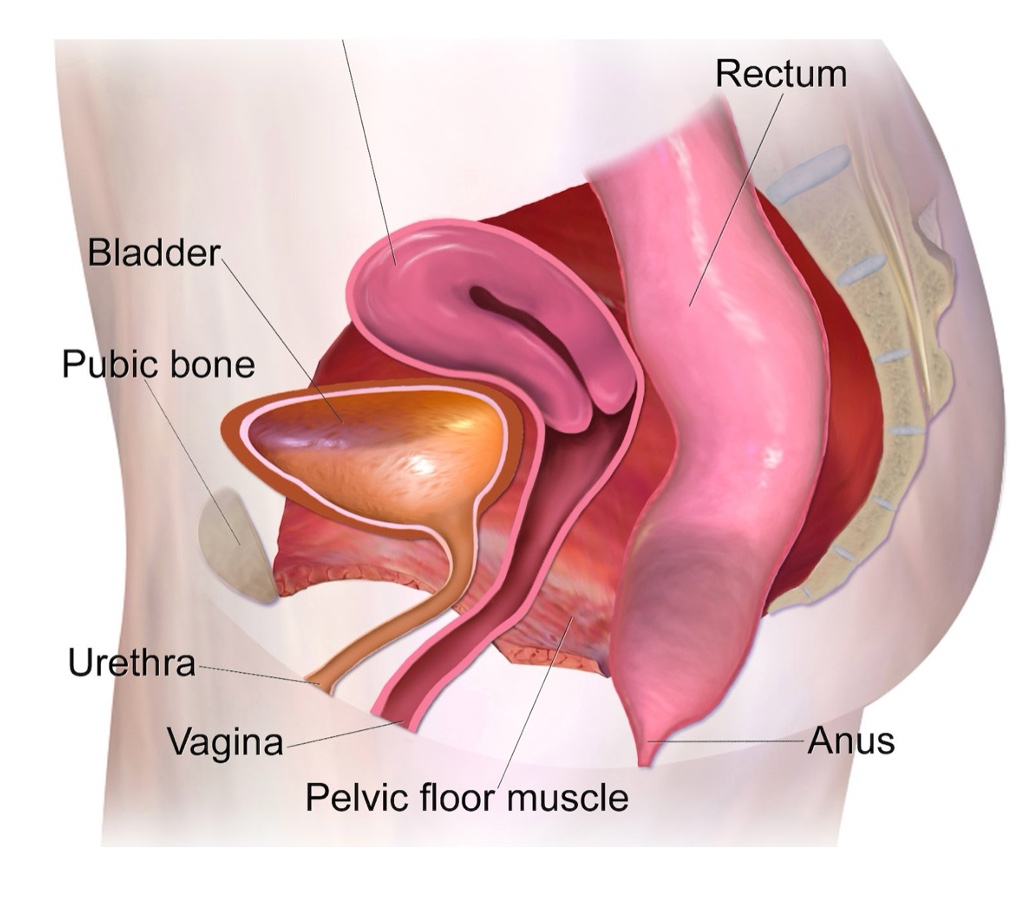

Another noteworthy point is how tightly packed the internal organs are within the pelvic cavity. As shown in Figure 3, the bladder, rectum, and uterus are closely positioned, meaning they can influence one another significantly. This interconnectedness underscores the complexity of the pelvic floor and the need for a comprehensive understanding when addressing pelvic health.

Figure 3. Side view of female anatomy.

If one is off, it can affect other things.

What is the Function of the Pelvis?

The pelvic floor is responsible for four primary functions: support, elimination, stability, and sexual pleasure.

Support: The pelvic floor holds up the visceral organs inside the body, providing essential structural support. It also serves as the foundation of our pressure system, which is crucial for enabling us to function effectively.

Elimination: The pelvic floor controls the retention of urine and feces throughout the day and facilitates their release at appropriate times, allowing for proper bowel and bladder emptying.

Stability: It helps balance the pelvis and stabilizes the lower back, hips, and pelvic girdle. Additionally, it plays a key role in core function, contributing to overall stability and movement efficiency.

Sexual pleasure: The pelvic floor is involved in arousal, intercourse, and orgasm for both men and women. Addressing this aspect is important, as it is a natural and functional part of the body.

A side note worth considering is that the pelvic floor often holds unprocessed emotions and memories of past events. Discussions about elimination or sexual pleasure can evoke strong emotional responses in patients. As therapists, it’s critical to approach these topics with care, empathy, and thoughtful therapeutic use of self. Creating a safe and supportive space for these conversations is essential to building trust and facilitating meaningful progress.

Optimal Pelvic Floor Function

Now that we understand the pelvic floor's functions let’s explore what it means to function optimally. When the pelvic floor is working as it should, it operates automatically. It doesn’t require conscious thought or interfere with activities. Think back to childhood—running, playing, and riding bikes were typically done without any concern about issues like leaking or bowel problems unless pelvic floor dysfunction was present. Optimal function means the pelvic floor supports daily activities seamlessly without being a point of focus.

When evaluating the pelvic floor, many people equate its health solely with strength, often in the context of performing Kegels. However, there are four key elements to consider when assessing pelvic floor integrity. First, range of motion is important. The pelvic floor must move through its full range, including shortening and lengthening. This ability is critical for proper function. Coordination is another essential aspect. The pelvic floor must work harmoniously with the diaphragm and adapt to its physical demands. The coordination required for someone who primarily walks may differ significantly from that of a multi-discipline athlete, whose activities demand a higher level of pelvic floor control.

Strength is, of course, part of the picture. Like any other muscle, the pelvic floor can be graded, but it’s important to remember that strength does not mean tightness. Many individuals, especially those who have experienced stress, trauma, or scar tissue, may have overly tight pelvic floors. This can even be true for postpartum patients. Focusing on Kegels can worsen the problem in these cases instead of helping.

Lastly, endurance is critical. The pelvic floor must withstand pressure over time, maintaining its integrity throughout sustained activity. For example, a person might be able to jump five times without difficulty but struggle to maintain pelvic floor control during a 20-minute run.

The important takeaway is that Kegels are not a universal solution. Without a thorough pelvic floor assessment, recommending Kegels could potentially worsen an individual’s symptoms. Tailored interventions based on specific assessments are essential for addressing each person's unique needs.

Dysfunction of the Pelvic Floor

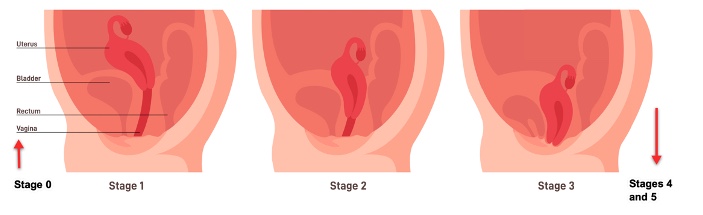

Dysfunction of the pelvic floor occurs when one or more of its four primary functions—support, elimination, stability, or sexual pleasure—becomes compromised. This dysfunction often presents as pain, prolapse, or leaking. Since everyday activities and changes influence the pelvic floor, it is highly sensitive to factors like injury, stress, pregnancy, hormonal shifts, and weakness. Any of these can contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction.

Prolapse, one of the more common dysfunctions, particularly for females after delivery, provides a good visual representation of how pelvic floor dysfunction can manifest. As in Figure 4, the stages of prolapse highlight the varying degrees of support loss within the pelvic cavity.

Figure 4. Stages of prolapse. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

To recap, we’ve established occupational therapy's role in pelvic health, reviewed the anatomy and functions of the pelvic floor, explored what optimal function looks like, and discussed the characteristics of dysfunction. Understanding these elements lays the groundwork for addressing pelvic health meaningfully and effectively.

Pregnancy

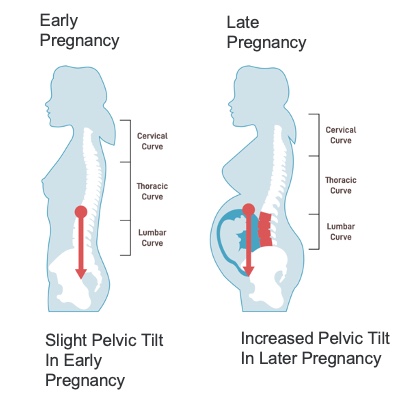

Now, let’s dive into the effects of pregnancy and a glimpse into the postpartum period, particularly how posture changes during pregnancy and how those changes affect function. Pregnancy is a time of rapid postural adjustments. With weight gain and shifts in weight distribution, combined with the increased ligament laxity caused by the hormone relaxin, the body adapts by tightening muscles to stabilize the growing baby. Over time, this tension can lead to anatomical changes in response to the sustained demands placed on the body. It’s a powerful reminder of how pregnancy transforms the musculoskeletal system, often in ways we may not immediately notice.

Let’s take a moment to experience this concept. Stand up if you can. It’s always good to reset our nervous systems; this is the perfect opportunity to engage physically with what we’re discussing. Take a minute to stand in what you feel is your best posture. Place your feet hip-width apart. Keep your pelvis neutral—no gripping with your glutes. Your shoulders should be back and down, with your head upright and your eyes straight ahead. Take a few deep breaths. As you hold this position, perform a quick body scan. How does this feel? Notice how your feet connect with the ground; if you want, sway gently back and forth to find the most balanced position for your hips. Relax any tension in your shoulders and take full, deep breaths. This position should feel comfortable and natural as you align your body optimally. Take a moment to appreciate how your body responds to this alignment.

Now, stay standing and imagine you’re pregnant. How does your posture shift? Did your hips tilt forward into an anterior pelvic tilt? Did you grip your glutes or curve your upper back, causing your neck to jut forward? Pay attention to how these adjustments impact your breathing—did it become harder to take a deep breath? Where do you feel tension building in your body? Does this feel as comfortable as the optimal posture you were in before?

This simple exercise illustrates pregnancy's significant changes to the body’s alignment and tension patterns. Understanding these shifts helps us better address pregnant and postpartum individuals' functional and physical needs.

Pregnancy Posture

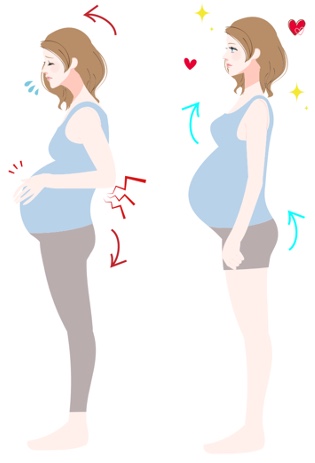

Here is the common pregnancy posture (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Examples of pregnancy posture.

Even after just a few minutes of experiencing it, you can feel how this posture can create discomfort—and that’s without the added weight of a growing baby in your abdomen. The difference between optimal posture and pregnancy posture is significant, and I hope you can feel that contrast in your body.

Some of this posture is the body’s natural way of accommodating the baby, but there are strategies to improve this alignment. These adjustments can support postpartum recovery and alleviate some of the aches and pains that arise during pregnancy. We’ll now take a deeper dive into pregnancy anatomy and posture, examining how these changes influence function.

It’s important to remember that every body is different. The goal isn’t to fit everyone into a single posture mold but to help individuals optimize their alignment to support their unique anatomy and movement throughout the day. Factors like past injuries, muscle weakness, or previous pregnancies can all influence someone’s posture. Starting with the neck, we’ll explore how each part of the body plays a role in adapting to pregnancy and how we can work toward better function and comfort.

Neck Posture

Forward neck posture is a common issue in both pregnancy and postpartum. This posture often creates long, weak muscles in the front of the neck and short, tight muscles in the back. It can even contribute to jaw pain due to the tension it generates. The connection between the jaw and the pelvis, through the frontal fascial line, means that neck posture can significantly influence pelvic floor function.

As we discuss these connections, I hope you find ideas to apply to your patients in the coming weeks. I’ll share a moment of application from a patient I worked with to spark your thinking.

A patient came to my office with complaints of urinary incontinence, which was the main reason for her appointment. During her intake, she needed to breastfeed her baby, and I noticed she was holding a lot of tension in her body while looking down at her baby the entire time. Her baby had challenges with latch and lactation, and she felt she had to hold herself in a specific position to support her baby’s success. When I asked if she was comfortable, she admitted that she had terrible neck pain but didn’t know how to address it. She mentioned that her lactation consultant had recommended a particular holding technique, but she hadn’t found a way to make it more comfortable for herself.

I suggested we work on it together, and she agreed. I educated her about the connection between neck posture and pelvic floor function and helped her explore the ergonomics of her breastfeeding position. We adjusted how she held her baby, focusing on creating a more supportive and sustainable posture. I provided her with neck exercises to perform while breastfeeding, encouraging her to occasionally look around the room to avoid prolonged tension from looking down. Afterward, we incorporated some stretches and manual therapy for her neck. She felt relief in her neck and noted an improvement in her pelvic floor symptoms.

This experience highlights how addressing neck posture, even in seemingly unrelated scenarios like breastfeeding, can have a meaningful impact on pelvic health. It reminds us to consider the whole body and its interconnected systems when working with patients.

Shoulder Posture

Rounded forward shoulders are commonly observed during pregnancy and postpartum, often caused by tight pectoral muscles. During pregnancy, as the center of gravity shifts with the added weight in the abdomen, the back muscles tire from holding everything up, leading to a rounded posture. This tightness can become even more pronounced postpartum during breastfeeding and baby carrying. For postpartum patients, it’s helpful to ask them to bring in their baby carrier to assess how it impacts their posture and identify any adjustments that might alleviate strain.

The serratus anterior is a key muscle for addressing rounded shoulders, as it works to balance the pectoral muscles. This muscle connects with the external obliques, making it a critical link between the core and the upper body. Incorporating exercises that activate and strengthen the serratus anterior can improve posture and reduce tension.

One tool I’ve found particularly helpful for releasing upper back tension is yoga tune-up balls. These myofascial release balls are excellent for relieving tightness from the base of the neck down to the sacrum. Patients can use them lying on the floor or against a wall if getting to the ground is challenging. Pregnant patients often appreciate these balls as they progress into the later stages of pregnancy since they provide a way to release tension without the rotational movements they may need to avoid in the thoracic spine. These simple interventions can offer significant relief and help patients achieve better posture and comfort.

Diaphragm Posture

The diaphragm plays a vital role in posture, especially during pregnancy, as the baby grows and the ribs tend to flare or grip. The diaphragm is a key stabilizer that influences the musculoskeletal system, impacts the vagus nerve, and works with the pelvic floor to manage pressure. Therefore, deep breathing is significant for physical function and the nervous system, influencing how stress is processed—an essential consideration for both delivery and adapting to motherhood.

In postpartum patients, it’s common for the ribs to remain in a flared or gripping position. Ideally, we aim for a 90-degree infrasternal angle, so assessing this during breathing can be valuable for any patient. In newly postpartum patients, the ribs often "turn off" during pregnancy. They are pushed out of the way or become stuck in a downward position, and the intercostal muscles stop functioning optimally to allow proper rib expansion. Focusing on rib mobility and full rib expansion breathing is crucial to restoring function, whether working in outpatient, hospital, or SNF settings.

One of the most effective techniques is 360 breathing, which is key to optimal pelvic floor function. It helps the pelvic floor achieve its full range of motion and improves its coordination with the diaphragm. This technique is also a standout area where occupational therapy can uniquely contribute to pelvic floor therapy.

I want to share an experience that highlights the value of 360 breathing. Early in my practice, I had a patient who had moved from Florida. She had a complex medical history, including seven miscarriages, endometriosis, two surgeries, and prior treatment from four pelvic floor therapists. She arrived at her first session with a three-inch binder of medical records, which made me panic a little. Given her extensive history and previous care at a large hospital system, I wasn’t sure what I could offer that hadn’t already been done.

As I began the session, I asked her if she had been taught 360 breathing. To my surprise, she said no. On one hand, I felt heartbroken that such a simple and effective tool had not been introduced to her. On the other hand, I was relieved and excited because I now had a meaningful way to help her. We began working on 360 breathing, which became her therapy's cornerstone. This experience reinforced how impactful such foundational techniques can be, even for patients with the most complex histories. It’s a reminder of the power of simplicity and the importance of addressing the basics to optimize function.

360 Breathing

I educated my patient on 360 breathing and worked with her to practice it. During our conversation, she mentioned that she used to be a yoga instructor before pelvic pain forced her to stop. While she had experience with breathing in yoga, no pelvic floor therapist had ever incorporated it into her treatment. The results were immediate. She felt significant relief simply from focusing on her breath, which was remarkable. This foundational practice became transformative in her life. She is pregnant with her second child, and it is an incredible journey. It all started with learning to breathe properly and integrating that skill into her daily activities.

Breathing is powerful, and as therapists, we should respect its profound impact on our patients. This patient’s story is not unique. I’ve encountered many others who, despite seeing other pelvic floor therapists, had never been taught this fundamental technique. They struggled to improve their function without proper breathing ingrained in their bodies.

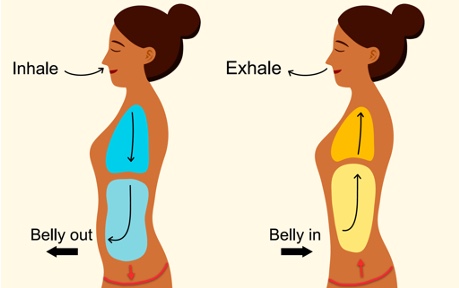

When we discuss 360 breathing, the focus is on creating expansion throughout the chest, back ribs, abdomen, and pelvic floor during the inhale, allowing everything to lift and contract upward on the exhale (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Example of 360 breathing.

This isn’t a forced breath but rather a gentle, whole-body movement. Many people lack the mind-body connection to feel their breath reach their pelvic floor, and that’s okay. It’s something to work on before progressing to strength-based exercises. The pelvic floor is the foundation of the body’s pressure system, and coordination must come first.

To help you connect with your breathing, I’d like to guide you through a 360 breathing and body scan meditation. I use this practice with patients in my office to help them relax and tune into their natural breathing patterns. When patients are relaxed, it’s much easier to observe their breath and work from a place of understanding. I often begin sessions with this type of meditation to help patients connect with their bodies before engaging in manual work.

Take a moment to get comfortable in your space. Feel your feet grounded and your body supported, whether sitting, lying down, or standing. Rest your hands comfortably, and if you feel comfortable, allow your eyes to close or settle into a soft gaze. Begin by taking several long, slow, deep breaths, breathing fully in, and exhaling slowly. With each inhale, feel your stomach expand, and with each exhale, let your body relax and let go. Allow the external noises and distractions to fade, bringing your focus inward.

Bring attention to your feet. Notice the sensations there—perhaps the feeling of the ground, your toes moving slightly, or the texture of your socks or shoes. Imagine your breath traveling all the way down to your feet and then back up through your body. Slowly move your attention to your ankles, knees, and thighs, noticing any sensations, tightness, or comfort. Simply observe without judgment, allowing these sensations to shift naturally.

Next, direct your focus to your lower back and pelvis. As you breathe, see if you can feel your pelvic floor gently dropping toward your seat during the inhale and lifting upward during the exhale. This movement is subtle, so just notice it without forcing or judging. Move your attention to your mid-back and upper back. Feel the sensations of your ribs expanding with each breath. Notice if one side moves more freely or if any areas feel restricted. As you breathe, allow any tension to melt away.

Now bring your attention to your stomach and internal organs. Feel the gentle rise and fall of your belly and observe whether your breath feels natural and coordinated between your chest and abdomen. Continue moving your focus upward to your neck, shoulders, and throat. Notice any tension or holding in this area and allow it to release with each exhale. Finally, shift your awareness to the movement of air through your nose or mouth. Feel the rhythm of your breath as it moves in and out, softening any remaining tension.

Expand your awareness to your whole body. From the top of your head to the tips of your toes, feel the gentle flow of your breath as it connects and integrates with your entire body. Take one final deep breath, noticing how your body feels more relaxed and how your breathing has improved. When you’re ready, gently open your eyes and return to the presentation.

Thank you for participating in this practice. I hope it demonstrates how breathing goes beyond the physical, connecting deeply with the nervous system and mental health. For many of our patients, stress from not being able to go to the bathroom, dealing with accidents, or balancing care for themselves and their children can be overwhelming. Breathing is a simple yet powerful way to help patients release stress and connect with their bodies.

Thoracic Spine and Abdominals

Let’s move on to the thoracic spine and abdominals. Weight changes during pregnancy often increase thoracic kyphosis, leading to alignment changes that affect the entire body. Core imbalances, combined with the diaphragm’s reduced effectiveness during this time, result in poor pelvic and spine stability. Postpartum, the ability to regain control over internal abdominal pressure is critical. Poor pressure management can hinder healing from diastasis recti and exacerbate pelvic floor dysfunction.

The transverse abdominis (TA) is the primary stabilizer of the core and works in synergy with the pelvic floor. However, the TA tends to become less active during pregnancy, especially if it hasn’t been intentionally engaged. Teaching TA activation during pregnancy is essential, not only for injury prevention but also for aiding postpartum recovery. Many pregnant individuals adopt the relaxed "birth posture" we discussed earlier, allowing their bellies to hang forward with minimal core engagement. This posture can increase the risk of injury and complicate recovery after delivery.

One effective way to teach TA activation is through hands-and-knees breathing exercises. I encourage patients to get onto their hands and knees with a flat back, similar to the starting position for cat-cow breathing, but with no movement in the spine. Instead, the focus is on the gentle relaxation and contraction of the core. Patients practice pulling their baby toward their spine during the exhale, which activates the transverse abdominis. Once they’ve mastered this position, we apply the same TA engagement during functional activities, such as lifting groceries or performing other daily tasks.

This approach helps patients maintain alignment, protect their core during pregnancy, and support recovery postpartum. Integrating these techniques into their everyday movements can prevent strain and foster long-term stability and function.

Back Pain During Pregnancy

Figure 7 shows how that center of gravity changes throughout pregnancy.

Figure 7. Changes in gravity throughout pregnancy. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

It’s easy to observe how weight shifts forward during pregnancy, increasing thoracic curvature. This forward shift also moves weight off the sacrum, which brings us to the sacroiliac (SI) joint and lower back. The SI joint, where the sacrum meets the ilium, is critical for transferring force between the upper and lower body. During pregnancy, the added weight of the baby places significant stress on this joint, often leading to discomfort or pain.

The gluteus medius is vital in providing stability to the SI joint. Ensuring this muscle is activated and strengthened during pregnancy is essential for maintaining SI joint function and reducing strain. Incorporating exercises that target and engage the gluteus medius can help pregnant individuals better manage the increased load on their joints, improving both comfort and overall stability.

SI Joint/Lower Back

Pubic symphysis dysfunction is common during pregnancy and postpartum, largely due to ligament laxity and muscular imbalances. From the earlier slide, we can see how the shift in the center of gravity, now positioned in front of the joint rather than directly over it, increases stress on the joint, often resulting in discomfort or pain.

Learning about rebalancing the hips was transformative for my practice. I had taken many pelvic floor courses, but it wasn’t until I studied with Lynn Schulte and her focus on balancing the bones that I truly understood the importance of this concept. Consider a delivery scenario where the individual is laboring on their side. In this position, one hip is constrained with a limited range of motion due to the bed, while the other flares out to allow delivery. Postpartum, that hip flare doesn’t just correct itself—it often remains "stuck" unless it is actively addressed and brought back into balance.

This imbalance has a profound effect on the pelvic floor muscles. One side of the pelvic floor becomes tight, while the other is overstretched. While internal pelvic floor muscle work can be beneficial, it is unlikely to yield significant progress unless the underlying hip imbalance and bone alignment are addressed. Rebalancing the hips and pelvis is key to optimizing pelvic floor function and alleviating discomfort, making it an essential component of effective treatment.

Pelvic Floor

Our pelvic floor plays a role in every activity we perform. Ideally, we want the pelvic floor to activate before the abdominals to provide foundational support. However, tightness or imbalance on one side of the pelvic floor can stress other body parts. Additionally, the pelvic floor reacts to tension throughout the body, further influencing function. A 2015 study demonstrated that increasing awareness and training of the pelvic floor muscles significantly decreased stress urinary incontinence in postpartum women. Another study in 2017 revealed that women experiencing pelvic floor issues are more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety, highlighting the profound impact pelvic health has on overall well-being.

Remember that just because someone could perform an activity during pregnancy doesn’t mean they can return to it immediately postpartum. The pressure system shifts postpartum. What was once supported by the baby during pregnancy is now managed by weakened abdominal muscles trying to adapt to a new pressure regulation system.

For example, I recently worked with a postpartum mom, a competitive soccer player. She had played soccer until she was 35 weeks pregnant and assumed she could return to playing just two weeks after delivery. Unfortunately, she began experiencing prolapse symptoms and significant pain, finding it difficult to manage pressure during activities. This highlights how the demands of postpartum recovery differ from those of pregnancy and why we cannot expect the body to resume pre-pregnancy or even pregnancy-level activity without proper rehabilitation immediately.

This brings us back to why posture changes during pregnancy matter so much. These shifts influence the pelvic floor, abdominal pressure, and overall stability, all of which need to be addressed to optimize function postpartum. Understanding and supporting this transition is essential for guiding our patients toward recovery and long-term well-being.

So What?

Why should we care? First and foremost, posture impacts function. How we move through life matters, and how we go through pregnancy matters. Postural imbalances don’t just resolve on their own after delivery. Without intentional effort to strengthen and rebalance our bodies, these imbalances can lead to lifelong dysfunction. Most women who experience pelvic floor dysfunction during pregnancy will continue to face it postpartum. Furthermore, the delivery method, labor process, and positions during labor significantly affect postpartum healing.

In my personal opinion, the idea of "getting your body back" after delivery should not focus on weight or size. Instead, it should emphasize addressing the imbalances pregnancy leaves behind to prevent injury and dysfunction. I often see perimenopausal patients who are dealing with issues that stem from their early postpartum phases. These issues, left unaddressed for 7, 10, or even 12 years, have evolved into more significant and challenging problems.

As occupational therapy practitioners, we are experts in function. It’s our role to care deeply about how people perform their activities and achieve their goals. Posture and breathing are often overlooked or dismissed as secondary concerns but are foundational. I encourage us to focus on these simple yet powerful elements that impact our patients most. You bring immense value by working on breathing and posture. It might not involve flashy equipment or quick fixes, but it lays the groundwork for meaningful and lasting success.

For those working in hospitals or skilled nursing facilities, breathing exercises are a great tool for patients who may initially refuse therapy or cannot get out of bed. You can simply meet them where they are, focusing on breathing to begin improving their nervous system regulation and functional capacity. These seemingly small steps can have a profound impact, as we’ve experienced throughout today’s discussion.

Refer to Pelvic Health Therapist

Referring patients to a pelvic health therapist is one of the most critical aspects we will discuss today. By now, you have a solid understanding of what the pelvic floor is, how it functions, and its role, particularly in the pregnant and postpartum population. This information should guide your treatment practice, not just with pregnancy and postpartum patients, but with everyone. Recognizing dysfunction and knowing when to act is essential.

Start by asking your patients about pelvic pain, leaking, or pelvic heaviness. While we often inquire about bathroom setups and assist with toileting, we rarely go further to discuss bathroom habits or challenge what patients perceive as "normal." Importantly, most other healthcare providers aren’t asking these questions either, so patients are unlikely to bring them up independently. Be the one to ask. Patients will often feel relief and gratitude when someone takes the time to address these concerns.

Leaking, for example, is common, but it’s not normal. It has become normalized largely due to societal stigma and misunderstanding, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Breaking this stigma is essential, and when the problem is beyond your expertise, or you don’t have time to address it, referring out is the best course of action.

A study conducted in Hawaii among family medicine and internal medicine practitioners revealed that only 36% of physicians sometimes screen for urinary incontinence, 45% sometimes screen for overactive bladder, and 43% rarely screen for prolapse. The study concluded that most primary care providers are uncomfortable managing urogynecological issues and do not make appropriate referrals. This indicates that pelvic health is not prioritized, even among other healthcare professionals. As OTPs, it often falls to us to initiate these conversations and advocate for the importance of pelvic health.

The prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction is growing significantly. In 2010, 28.1 million American women had at least one pelvic floor disorder, and this number is projected to increase to 43.8 million by 2050. These statistics highlight the increasing need for awareness and intervention.

We need to address this need. For example, if a patient casually mentions that she has never experienced an orgasm, you can say, “I know someone who can help you with that.” If you hear about a child unable to attend daycare because they’re not potty trained or a mom who only wears black pants because of leaking, we must inform them that there are solutions.

Our responsibility is to advocate for pelvic health and occupational therapy's role in this specialty. Not every OTP needs to be a pelvic health therapist or receive specialized training. However, every OTP should recognize dysfunction, have these important conversations with patients, and connect them to resources or professionals who can help. Doing this can help change the care landscape and awareness for pelvic health nationwide.

Summary

In closing, I’d like you to take a moment to think about yourself. Imagine if you experienced symptoms—maybe you have, or maybe you haven’t—but consider how it would feel if you couldn’t go to dinner with friends out of fear of not being able to find a bathroom in time or if you were unable to have intercourse without pelvic pain. How would that affect your daily function? Your quality of life? Your relationships? How would it dim your light in this world?

As you encounter patients, remember the importance of addressing these concerns if you see or hear anything related to the pelvic floor’s functions—elimination, support, stability, and pleasure. Refer them to a pelvic health therapist, and let them know the profound impact that addressing these issues can have on their lives.

Thank you for spending this time with me today. It has been a pleasure sharing this information with you, and I hope you’ll apply some of these insights to your practice tomorrow and in the weeks ahead.

Exam Poll

1)Pelvic health is the best possible functioning and management of the what?

2)In the case study, which of the following was NOT discussed regarding her mental and emotional status?

C is the correct answer, as she does not live in a rural area.

3)How many muscles make up the pelvic floor?

There are 16 muscles that make up the pelvic floor.

4)What is the function of the pelvis?

The pelvic floor does all of these.

5)What joint in the body is most impacted by the weight of a growing baby?

Yes, the sacroiliac joint, which is a part of the hips.

Questions and Answers

Would you suggest using a pregnancy girdle to help with posture?

I don’t usually recommend many belts or supports. The only one I typically suggest is the Serola Sacroiliac Belt. If a patient cannot maintain stability in their hips, I prefer to focus on strengthening the muscles first before jumping into using external supports. Belly bands and similar products generally don’t hurt, but they don’t necessarily provide much benefit, either. The Serola Sacroiliac Belt is different because it compresses the hips and supports the SI joint.

How do bladder irritants and body composition, such as weight gain post-pregnancy, affect stress incontinence?

I don’t see significant evidence that weight gain post-pregnancy directly impacts urinary incontinence. Society tends to overemphasize weight as a cause. However, bladder irritants are a real factor. It’s important to pay attention to what you’re hydrating with and how much. Some people try limiting hydration to avoid leaking, but that can worsen things. When the bladder isn’t properly hydrated, its substances become more concentrated, irritating the bladder. Drinking enough water—typically half your body weight in ounces daily—is key. For breastfeeding individuals, even more hydration is needed.

What is the hip balancing course you mentioned toward the end?

Lynn Schulte offers excellent pregnancy and postpartum courses that focus on hip balancing. She’s a physical pelvic floor therapist and takes a whole-person approach, including alignment of both the mother and the baby. For pregnancy patients, she emphasizes ensuring the baby is midline and the hips are balanced for smoother deliveries. Her courses are highly valuable and align well with the holistic care we aim to provide.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Spurrier, K. (2024). The driver of function: Postnatal pelvic health virtual conference. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5759. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com