Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Early Co-Regulation In The Infant And Parent Dyad, presented by Teresa Fair-Field, OTD, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify causes of disrupted or atypical co-regulation.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize assessment tools and treatment strategies using case study presentations that impact co-regulation and self-regulation to support occupation.

- After this course, participants will be able to list co-regulation strategies to parents and treatment team members in understandable terms to support occupation.

Introduction

Greetings. I'm pleased to revisit the topic of co-regulation in the parent-infant dyad. When I initially addressed this subject for occupationaltherapy.com in 2017, much of the latest research on co-regulation had yet to be published. Fortunately, since then, there has been a significant surge in evidence, particularly in the realm of infant mental health and co-regulation. I'm thrilled to offer an update to the audience of occupationaltherapy.com, presenting the latest findings in co-regulation.

For those who have previously taken this course, I've taken your feedback into account and expanded the content on OT assessment and treatment. And to those who are new here, welcome. Co-regulation is a profoundly impactful topic, and I'm eager to contribute to this ongoing dialogue.

Operational Terms

- Parent/Caregiver

- Parent/Infant Dyad

Let's start by defining some terms we'll use throughout this discussion. I'll use the terms "parent" and "caregiver" interchangeably throughout the course to recognize today's diverse family structures. If I do happen to use the term "mother" or any other specific term, it's likely because it was presented in a piece of literature I may reference. You'll often hear me refer to the "parent-infant dyad," which refers to the parent or caregiver together with the infant, examining their connection as a cohesive unit.

Self-Regulation

- ‘the act of managing thoughts and feelings to enable goal-directed actions’ (Murray et al., 2014)

- Serves as the foundation for lifelong functioning

- The act of managing cognition and emotion

- Influenced by a combination of individual and external factors

- Can be strengthened and taught (like literacy)

- Dependent upon ‘co-regulation’ by parents or other caregiving adults

- Disrupted by prolonged or pronounced stress and adversity

- Develops over an extended period (birth through young adulthood)

Let's delve into the concept of self-regulation, which has evolved and matured over the years. Research on self-regulation, conducted by Desiree Murray and her team at the Duke University Center for Child and Family Policy under contract with the US Department of Health and Human Services, offers valuable insights. Their definitions align with the terminology used here. You can find their work easily accessible, and I've provided a link to Maria et al. 2014 in your resources, which is available for free download without needing academic library access.

While some aspects of self-regulation may be familiar to occupational therapists, I'd like to emphasize certain points highlighted in red text. Self-regulation, as indicated, can be cultivated and taught akin to literacy. Much of our work in clinical and educational settings revolves around nurturing the language and skill-building aspects of self-regulation. It's crucial to recognize that these self-regulation skills are built upon early experiences of co-regulation between parents or other caregivers. This lays the foundation for self-regulation to flourish.

There's a wealth of literature available on how adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), stress, and adversity can impact infants and subsequently affect the development of self-regulation. Furthermore, it's important to note that the timeframe for self-regulation development spans from birth through young adulthood, evolving alongside executive functioning skills.

Co-Regulation

- ‘an interactive process of regulatory support that can occur within the context of caring relationships’ (Rosanbalm & Murray, 2017)

- Provide a warm, responsive relationship

- Structure the environment

- Teach and coach self-regulation skills

Now, let's explore the concept of co-regulation. Co-regulation involves an interactive process of regulatory support that unfolds within caring relationships. These relationships are characterized by environments that are warm and responsive to the needs of infants or young children. They provide structured settings conducive to engagement, where caring adults can effectively teach and coach self-regulation skills. Throughout our discussion, we'll delve into specific strategies for nurturing these skills within the context of co-regulation.

Warm, Responsive Relationship

- Display care and affection

- Recognize and respond to cues

- Provide caring support in times of stress

- Communicate (words and actions) interest in the child’s world

- Respect the child as an individual

- ‘Unconditional positive regard’

(Rosanbalm & Murray, 2017)

Defining a warm and responsive relationship involves several key elements. Firstly, it entails demonstrating care and affection towards the young infant. Additionally, it encompasses the ability of the adult to recognize and respond to the infant's cues effectively. Providing supportive care during times of stress, showing active interest in the child's world, acknowledging the child as an individual, and practicing unconditional positive regard are all integral components of such a relationship. Later, we'll discuss aspects of children who enter occupational therapy care, such as those from foster care systems. One of our case studies involves a child from such a system, characterized by significant ACEs. While they are now in a home with adoptive parents and beginning to develop, challenges in early co-regulation may still arise.

Structure the Environment

- Physical safety

- Emotional safety

- 'Able to learn at their level of development without serious risk to their wellbeing’

- Consistent, predictable routines, & expectations

- Well-defined logical consequences

(Rosanbalm & Murray, 2017)

Once a child is in a stable placement, crucial reparative work must be done, particularly in structuring the environment. This involves ensuring the child's physical and emotional safety, allowing them to learn and develop without jeopardizing their well-being. Consistent and predictable routines and expectations are paramount, as they provide stability and security for the child. Additionally, well-defined and logical consequences play a significant role in this process. Establishing such structures fosters a sense of safety and forms the foundation for developing self-regulation skills based on understanding cause and effect.

Teach & Coach Self-Regulation

- Modeling

- Instruction

- Opportunities for practice

- ‘Prompts for skill enactment’

- ‘Reinforcement of successful use’

(Rosanbalm & Murray, 2017)

Teaching and coaching self-regulation often follow a similar approach to teaching any other skill. This involves modeling, providing instruction, offering opportunities for practice, prompting the use of skills when needed, and reinforcing their application. As outlined by Rosenbaum and Murray, this methodology emphasizes a systematic approach to skill development. You can find their work linked in your resources, which can serve as a valuable parent handout. Although the white paper may be at a college reading level, it offers caregiver-specific guidelines for supportive co-regulation activities at various developmental stages, from infancy through young adulthood. The bullet-point format is at about a 10th-grade reading level but can be further simplified if necessary, making it an excellent resource for parents. Nonetheless, effectively engaging caregivers in understanding and implementing these concepts can still present challenges.

Parent-Facing Definition of Co-Regulation

- ‘borrowing’ regulation off someone else’s body

(Fair-Field, 2017)

Over time, I've crafted my own "parent-facing" definition of co-regulation, which I find more approachable: "The child is borrowing regulation off of someone else's body." This definition lends a friendlier tone and opens the door for parent and caregiver education. By explaining that when a child borrows regulation from an adult, their response will likely improve if the adult's body is regulated, we empower caregivers to understand and participate in this dynamic interaction more effectively. I encourage you to develop your own version of this concept, whether adapted from my vocabulary or entirely original, to facilitate meaningful conversations with parents and caregivers about co-regulation.

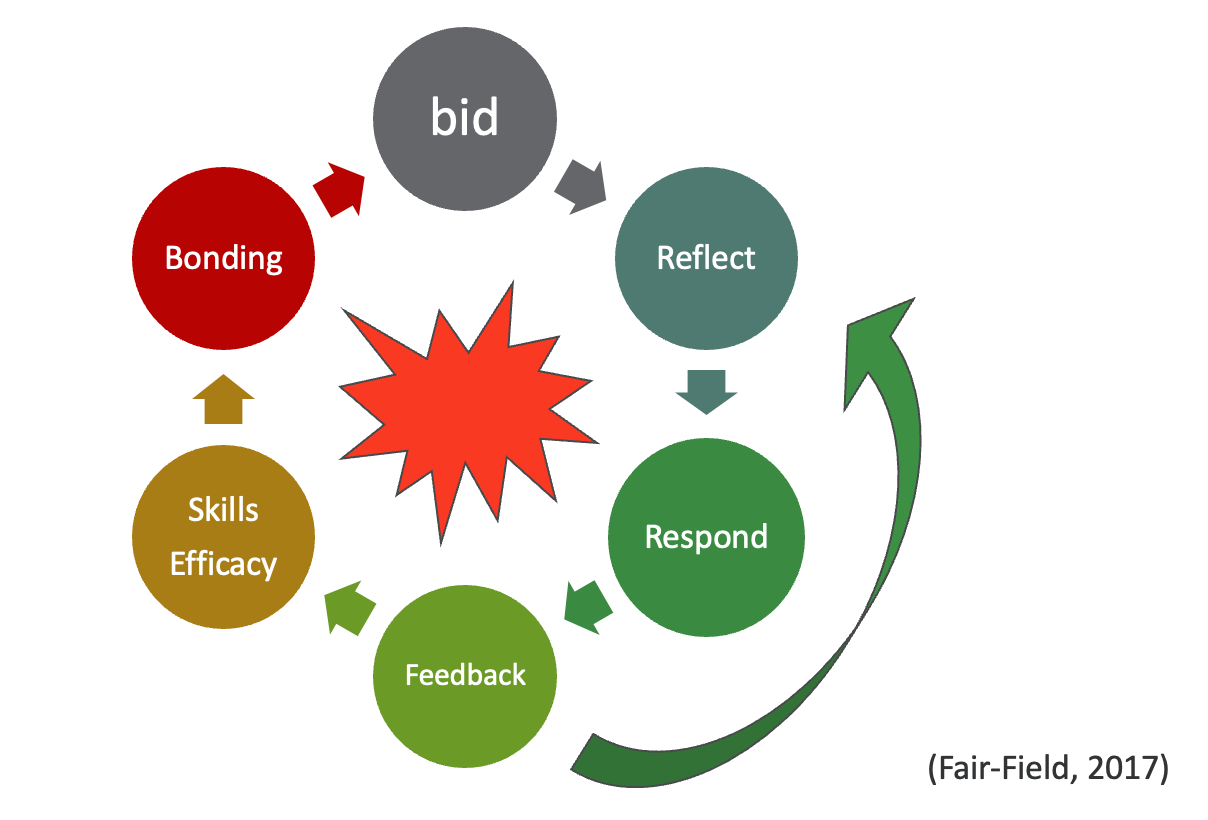

Cycle of Regulation

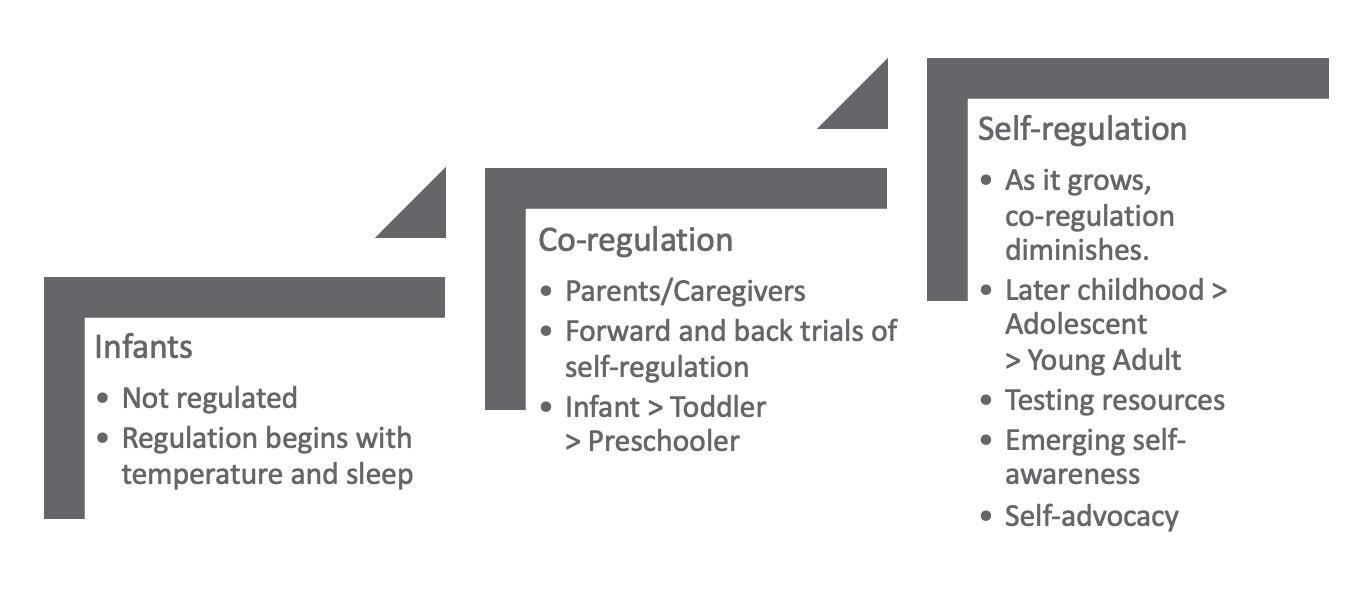

Let's now talk about this cycle of regulation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cycle of regulation illustration.

The process of co-regulation and self-regulation can be likened to running up a sand dune rather than climbing stairs, as it involves cycles rather than linear progression. We take steps forward but sometimes slide backward to more familiar levels of functioning. It's essential to understand that achieving self-regulation doesn't mean abandoning co-regulation; instead, it expands our toolbox of coping mechanisms. Continuous co-regulation with others allows access to higher levels of functioning.

Infants are not born regulated; regulation begins with basic functions like temperature control and sleep. Early interventionists often assess infant sleep behavior to gauge regulatory development. Co-regulation then emerges with parents, caregivers, or other significant adults. Throughout infancy, toddlerhood, preschool, and into school age, there are trials of self-regulation, with periods of success followed by regression back to co-regulation or lack of regulation.

As children near school age, self-regulation becomes more prominent, reducing the necessity for co-regulation but not eliminating it entirely. This cycle persists through young adulthood. As self-regulation grows, children test their resources, occasionally reverting to co-regulation. During this process, they may develop emerging self-awareness of tools and strategies. Concepts like the "zones of regulation" provide a vocabulary to describe experiences, fostering self-advocacy over time.

Dynamic Co-Regulation

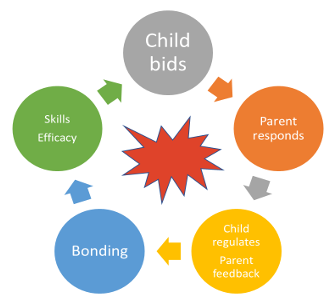

This is my own graphic in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Illustration of dynamic co-regulation (Fair-Field, 2017).

I use a visual representation to illustrate the dynamics of a successful co-regulation event. At the onset, there's an upset, depicted by a red explosion. This reflects the intense emotions often experienced by young children and is mirrored in the language used by parents and caregivers to describe such events. Following the upset, the child makes a bid for co-regulation, symbolized by a gray circle, as they recognize their inability to self-regulate at that moment.

The bid for co-regulation can manifest in various ways. If successful, regardless of the child's presentation, the parent or caregiver responds with their own regulated body, represented by an orange circle. The child then borrows regulation from the caregiver's body, initiating their own self-regulation process. This reciprocal interaction allows the child to begin regulating while the parent receives feedback on the effectiveness of the co-regulation event.

A successful co-regulation event strengthens the bond between the child and caregiver, fostering the child's development of skills and efficacy. They learn they can rely on the caregiver for co-regulation, which resolves or mitigates their upset until the next bid for regulation. This process forms a continuous loop as the child's developing skills and efficacy influence their subsequent bids for co-regulation.

Factors Affecting Regulation

- Genetics

- Environment

- Neurological development

- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

- Intrauterine Exposures

- Prematurity

- Allergies / Digestion / Physical Symptomatology

- System maturation

- Accommodation / Strategy / Exposure

Several factors influence regulation, including genetics, environment, neurological makeup, and ACEs. ACEs, such as intrauterine exposures or issues of prematurity, can significantly impact a child's regulatory system. These factors and exposure to explosive bids for co-regulation often contribute to infants and young children entering the early intervention system.

Many children in early intervention present with issues related to these factors, which also have implications for their future self-regulation. Addressing these challenges requires considering various confounding variables, making it challenging to pinpoint a single cause. While some factors, like physical discomfort, are modifiable and can be addressed concurrently with therapy, others are historical and have occurred before the child's arrival in therapy.

As therapists, our approach addresses the child and family system as they are presented in the clinical environment. We recognize the complex interplay of factors influencing regulation and tailor interventions accordingly.

Assessing Regulation

- Who to Assess?

- Child and

- Parent/caregiver

- How to Assess?

- Observation of infant regulatory behavior

- Parental questionnaires

- Sensory Assessment

(detection of sensory behaviors as a coping strategy)

- poor adaptation skills

- sensory reactions trigger emotional states

- emotional states trigger sensory reactions

- perceived loss of control (remember volitional impact)

Assessing co-regulation and self-regulation in infants and young children requires evaluating both the child and the parent or primary caregiver. This approach provides insights into genetic aspects of regulation that may be inherited if a birth parent is part of the dyad. Additionally, it helps identify mismatches in regulation needs between the caregiver and the child.

Mismatched regulation needs can lead to challenges and disruptions in co-regulation, causing the dyad to be off-step. Clinically, infants and toddlers rarely communicate regulation concerns directly, so understanding the dynamics between caregiver and child is crucial. If the caregiver and child co-regulate similarly, regulation issues may not be apparent at younger ages. However, as the child develops and encounters new environments like school, mismatches in co-regulation styles may become problematic.

Assessment should, therefore, consider both the caregiver's and the child's regulation styles and expectations. Mismatches often garner the most attention from caregivers who are unable to meet their child's needs or face unexpected behaviors based on their own sensory or self-regulation style. When conducting assessments, it's essential to evaluate both the parent or caregiver and the child, but how exactly do we begin this assessment process?

Observational Assessments

We're probably most familiar with providing parental questionnaires, but I'd like to describe a few infant observational assessments that are worth seeking out if you do complete a lot of infant work.

NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS)

- Measures healthy term infants & preterm, at-risk infants, drug exposures, etc.

- Hospital, clinic, or EI

- 20-30 min to administer

- Minimal handling

- Measures:

- Reflexes

- Tone

- Movement quality

- Response to ‘cuddling’

- Nystagmus (an early indicator of neuro dysfunction)

- Arousal, Excitability, Signs of Stress

- Self-soothing/Regulatory behavior

The NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS) is an interdisciplinary assessment tool designed for evaluating at-risk infants, including preterm, drug-exposed, and healthy-term infants. Despite its name, don't let the "NICU" part discourage you from using it in early intervention or infant-based practices. While originally developed for neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), it is applicable in various settings.

Administering the NNNS typically takes 20 to 30 minutes and involves minimal handling of the infant, making it feasible during parent coaching sessions. It is suitable for hospital, clinical, and early intervention environments. The assessment evaluates neurobehavioral outcomes such as reflexes, muscle tone, and stress responses, and importantly, it considers the infant's state of arousal. This adaptability is particularly valuable in early intervention settings, where observing the child in their natural home environment is essential.

Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS)

- Measures all infants with multiple pre- and perinatal factors

- Age 0-2 months old

- Measures 28 behavioral items on a 9-point scale

- Measures 20 neurological items on a 4-point scale

- Provides a behavioral “portrait” of the infant

- Strengths

- Adaptive responses

- Vulnerabilities (areas requiring ‘extra care’)

The Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS) is another valuable tool used to assess newborn behavior. Originally published in 1989 and revised in 1995 by T. Barry Brazelton and associates, it remains widely used and respected in its second edition, published in 2011.

This assessment tool has a long-standing history of validity and reliability, with its presence in recent literature affirming its continued relevance. The NBAS examines the behavior of all infants but is particularly useful for studying the effects of various factors such as intrauterine deprivation, maternal substance use, C-section delivery, preterm birth, and other pre and perinatal deficiencies that can impact development. It demonstrates extensive cross-cultural validity and decades of reliability.

The NBAS assesses behavioral and neurological items on a point scale, focusing on both strength areas (termed adaptive responses) and vulnerabilities. Identified vulnerabilities serve as areas where the infant may require additional care, making the assessment a valuable educational tool for families, providing insight into their infant's needs and promoting informed caregiving practices. You can find this tool available for purchase, and it's also accessible for free download from various online sources, including Amazon.

Parental Questionnaires

Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ) and (IBQ-R)

- Infants 3-12 months old

- Translated into 38 languages

- Activity Level

- “Distress to limitations”

- Approach

- Fear

- “Duration of orienting”

- Smiling and Laughter

- Vocal reactivity

- Sadness

- Perceptual sensitivity

- High-intensity pleasure

- Low-intensity pleasure

- Cuddliness

- Soothability

- Rate of recovery from distress

The Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ) is one of the most widely used, researched, and translated tools for assessing infant behavior. Originally developed in 1981 and revised in 1998, it remains actively utilized today, with short and very short forms continuing to be prevalent in evidence throughout the 2020s.

One of the IBQ's most valuable features for early interventionists is its translation into 38 languages, including multiple Chinese and Spanish dialects, making it one of the most culturally valid tools available. While the database provides a list of authors who completed these translations, the actual translated versions are not linked, necessitating additional steps to locate them. However, having access to this list can expedite the search process for practitioners seeking specific translations for their families.

As for its assessment areas, the IBQ covers various aspects of infant behavior within their first year. It measures activity distress to limitations, approach fear, duration of orienting, vocal reactivity, sadness, sensitivity, high-intensity pleasure, low-intensity pleasure, cuddliness, suitability, and rate of recovery from distress. These dimensions assess various aspects of infant behavior, including their response to stimuli, emotional regulation, and sociability, providing valuable insights into their development and well-being.

Sensory-based Questionnaires

Sensory Profile 1 & 2 (Dunn, 2002, 2014)

- Infant Sensory Profile 2 (2014; birth-6m)

- Toddler Sensory Profile 2 (2014; 7-35m)

- Adult Sensory Profile (older edition, 2002)

Our sensory-based questionnaires are commonly used tools in our practice, providing valuable insights into aspects of regulation. However, it's important to consider how they complement other assessment tools and recognize their limitations, especially in culturally diverse settings or when language translations are needed.

For instance, the Sensory Profile tool offers both infant and toddler forms, but its adult forms have not been updated recently. Consequently, using the Sensory Profile tool alone may not effectively capture the co-regulation dynamics of the dyad. While you can administer separate adult and infant/toddler forms to the caregiver, connecting the results requires observational skills.

Observations should encompass factors such as regulatory instability, sleep patterns, body temperature, and body state to bridge the gap between caregiver and child assessments. While the Sensory Profile tool provides valuable information, it may not directly support the interpretation of co-regulation dynamics between the caregiver and child. Therefore, it's essential to supplement questionnaire data with observational insights for a comprehensive understanding of regulation in the dyad.

Sensory Processing Measure 2 (Parham et al., 2021)

- Infant/Toddler forms (4-30m)

- Adolescent (12-21y) and Adult forms (21-87y)

The Sensory Processing Measure (SPM) is another valuable tool for assessing sensory processing abilities in both children and adults. Developed by Diane Parham et al., the most recent edition, published in 2021, includes updated norms and expanded standardization to include infants as young as four months old. This expansion is particularly significant for preterm and early-term infants who are increasingly encountered in early intervention settings.

One notable aspect of the SPM's standardization process is the inclusion of side-by-side self-assessment with the primary parent or caregiver. This approach ensures that the assessment captures the dyadic interaction between caregiver and infant, providing a more comprehensive understanding of sensory processing abilities in the context of co-regulation.

If you use the SPM in your practice, it's essential to utilize the updated SPM-2 version when assessing the infant and caregiver dyad to ensure alignment with the latest norms and standardization procedures. Be sure to explore the work of Diane Parham et al. for further insights into the development and application of the SPM in clinical practice.

Disordered Sensation: Effects of the Sensory System on Co-regulation

Understanding the connection between sensory processing and co-regulation is crucial, especially when considering the impact of disordered sensation or sensory processing differences on both adults and children. While we have clear models for understanding self-regulation, integrating sensory processing assessments into our evaluation process provides valuable insights into how sensory experiences influence co-regulation dynamics.

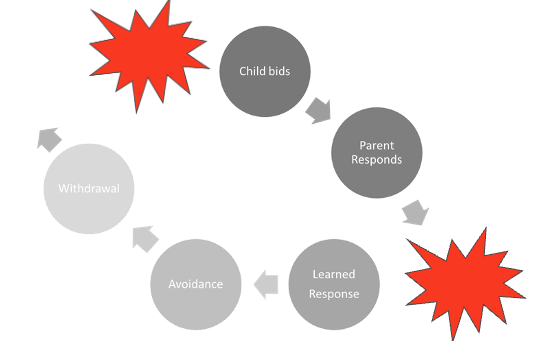

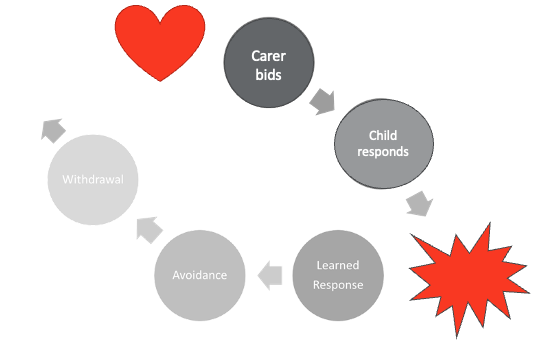

Figures 3 and 4 are my own creations that show co-regulation mismatches.

Figure 3. A mismatch between a child and parent when the child bids (Fair-Field, 2017).

Figure 4. A mismatch between a carer and child when the carer bids (Fair-Field, 2017).

This visual depicts the dynamics of an unsuccessful co-regulation event or a mismatch in co-regulation between the caregiver and the child. It begins with a red explosion, signifying the child's upset or distress, which can stem from various causes, including sensory experiences. It's crucial to note that the nature of the initial upset doesn't inherently cause a problem in co-regulation; rather, it's the pattern of co-regulation between caregiver and child that matters.

In this scenario, the child makes a bid for co-regulation (represented by the darkest gray circle), but the caregiver's response doesn't effectively meet the child's regulatory needs due to factors such as the caregiver's own stress or an incomplete bonding relationship. Consequently, the child's dysregulation may escalate, leading to further distress and an unsuccessful resolution of the bid for co-regulation.

Both the child and the caregiver develop learned responses from this interaction. The child may learn that their co-regulation needs are not met, leading to avoidance or withdrawal behaviors in future bids for co-regulation. Similarly, the caregiver may develop a learned response of ineffectiveness in meeting the child's needs, further perpetuating the cycle of unsuccessful co-regulation.

One example of such a mismatch is when a child reacts negatively to the loving touch initiated by the caregiver, leading the caregiver to avoid initiating affectionate interactions in the future. Another example is when a caregiver tolerates disruptive or overwhelming touch from the child, leading to a mismatch in co-regulation bids and responses.

Addressing these mismatches in occupational therapy involves understanding the sensory aspects of behavior and intervening to break patterns of avoidance and withdrawal. By maturing the child's sensory system and promoting self-regulation, we aim to close the co-regulation loop and improve the bonding relationship between caregiver and child.

Indicators of Poor Regulation

Here are indicators of poor regulation shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Indicators of poor regulation (Click here to enlarge the image.)

Persistent sleep disturbances well into toddlerhood, along with challenges in body awareness and sensory-seeking behaviors like leaning, pushing, or crashing, are common indicators of sensory processing difficulties in children. These behaviors may also manifest as touch avoidance or oral motor behaviors, such as prolonged mouthing of objects or difficulties with eating and feeding.

Assessing these areas requires a comprehensive approach, utilizing tools such as the Bailey Scales (e.g., Bailey Scales-4) and the DASH (Developmental Assessment of Young Children). These assessments include components for social, emotional, and adaptive behavior, providing valuable insights into functional areas of regulation in infants and toddlers.

By utilizing a range of assessment tools tailored to the needs of early intervention settings, occupational therapists can gather comprehensive information to guide intervention strategies and effectively support children with sensory processing difficulties. The choice of assessment tools may vary based on state regulations and available resources, but a combination of tools can offer a holistic understanding of a child's regulatory challenges and inform targeted interventions.

Occupational Therapy Interventions: Treatment Activities to Impact Successful Co-regulation

Let's talk about some therapy interventions we might promote that are all within OT scope.

- Caregiver-focused interventions

- Address the mismatch

- Parent-education & Parent coaching

- Child-focused interventions

- Assessments will guide your interventions

- Environmental supports and adaptations

In the realm of treatment, it's crucial for a therapist to address the struggling emergence of self-regulation to tackle the issue of mismatch between the caregiver and the child. Simply discussing environmental supports and adaptations isn't sufficient until this mismatch is clearly articulated in a way that the parent can understand, allowing them to recognize that their own regulatory system differs from their child's. This realization creates an essential space for parents to reconsider their bonding with the child.

It's important to remember that the diagram illustrates how this mismatch leads to learned behaviors such as avoidance and withdrawal. Parents often interpret their child's reactions as a sign of their own failure. By bringing awareness to this mismatch, therapists help parents understand that they haven't necessarily been doing things wrong; rather, there's a distinction between how the parent regulates and how the child's needs differ.

Treatment should encompass both aspects of the dyad, involving the parent in providing co-regulation and the child in seeking it, ultimately facilitating a successful transition to self-regulation over time. While child-focused interventions are typically informed by assessments, addressing the caregiver's role in the dyad may be a newer practice for some therapists, requiring a more nuanced approach.

Parent Coaching Activities

- The Still-Face Experiment

- Three successive interactive contexts

- Caregiver is asked to use face-to-face interaction and play with the infant in an expressive manner. (2-3 min)

- Caregiver is asked to use a ‘still face’ (unresponsive poker face) when facing the child without smiling, touching or talking. (2-3 min)

- Caregiver is asked to conduct a ‘reunion’ interaction in which normal expressive interaction is resumed. (2-3 min)

- Used with infants between 2-12 months old

- Outcome: changes in behavior, including averting gaze, turning away, negative affect, physical distancing, or agitation

Here's a parent coaching activity known as the face-to-face or still-face experiment, originally studied in 1978 by one of the founding fathers of infant mental health. Despite its age, it remains relevant in current literature and is internationally recognized for studying the interactive dynamics between parents and children in the home.

During this experiment, the caregiver engages in two to three minutes of close-face interaction and plays with the infant in an expressive and attentive manner. Then, the caregiver is instructed to adopt a still face, displaying no emotional response or attempts to engage with the infant for another two to three minutes.

Following the still-face phase, a reunion episode occurs where normal interactive engagement is resumed for another two to three minutes. Typically conducted with infants in their first year, the experiment often reveals changes in infant behavior during the still-face phase. Infants may display signs such as turning away, exhibiting negative affect like crying or increasing physical agitation in response to the sudden lack of responsiveness from the caregiver.

Even after the reunion episode, infants may exhibit hesitancy to engage fully, indicating a level of uncertainty or mistrust. By incorporating supportive coaching, therapists can utilize this experiment to gain insights into the formation of co-regulation and the child's reliance on it for their own behavior regulation.

- The Still-Face with Smartphone Experiment (2020)

- Three successive interactive contexts

- Caregiver is asked to use face-to-face interaction and play with the infant in an expressive manner. (2-3 min)

- Caregiver is asked to engage with their smartphone while facing the child without smiling, touching or talking. (2-3 min)

- Caregiver is asked to conduct a ‘reunion’ interaction in which normal expressive interaction is resumed. (2-3 min)

- Used with infants between 2-12 months old

- Outcome: changes in behavior, including averting gaze, turning away, negative affect, physical distancing, or agitation

The parallels between the still-face experiment and parents engaging with smartphones are indeed striking. In 2020, a study involving 227 parent-infant dyads conducted the still-face experiment with parents using smartphones instead of interacting with their infants during the still-face phase. The research revealed that infants exhibited strong reactions, including increased negative affect, attempts at self-soothing, and escape behaviors during the phone-distracted phase. Additionally, many infants did not return to their prior baseline levels of engagement during the reunion phase.

Notably, infants aged nine months or older showed particularly strong responses compared to younger infants. This suggests that older infants may be more sensitive to disruptions in caregiver attention. Therefore, employing this modified still-face experiment as a parent coaching activity, accompanied by supportive and non-judgmental discussion, could be highly effective. Parents could learn to implement self-limiting strategies such as setting device timers or using dark modes to structure their phone use around their infant's schedule. It's essential to find a balance between supporting parental mental health and promoting infant mental health, which may also involve providing referrals or support for parental mental health when needed.

ASI® Interventions

- Fussy Baby

- Sleepy Baby

- Clumsy Baby

- Disorganized Baby

ASI research offers insights into four distinct types of infants facing regulation challenges. These categories include the "Fussy Baby," characterized by frequent and prolonged crying, difficulty settling down, and easy waking; the "Sleepy Baby," who exhibits sluggishness, struggles to awaken for feeding, and has trouble staying alert during the day; the "Clumsy Baby," who may take longer to achieve motor milestones and display awkward movements; and the "Disorganized Baby," who experiences difficulty learning how to play and reproducing skills.

For occupational therapists, these descriptions provide a lens through which to understand infants' behaviors and developmental needs. By attentively listening to parents' observations and descriptions of their infants' behaviors, early intervention providers can gather valuable insights into sensory reactions and tailor interventions to support the infant's growth and development.

- ASI® Interventions: Fussy Baby

- Coach the caregiver to recognize STOP SIGNS:

- Color changes

- Looking away from the stimulus

- Fussy

- Jerky movements

- Coach the caregiver to recognize STOP SIGNS:

The additional handout emphasizes the importance of coaching caregivers to recognize the early signs of dysregulation in fussy babies. Rather than attempting to coax happiness out of a fussy child, which could exacerbate their dysregulation, caregivers should discontinue social and engagement demands and focus on calming strategies. These strategies involve creating a calming environment with low lights, low voices, calm facial expressions, and reduced stimuli. It's crucial to note that moving towards calming doesn't imply disengagement; caregivers should remain engaged with the child during this process. However, depending on the caregiver's natural tendencies, employing these calming strategies may not align with their usual responses to a fussy baby.

- ASI® Interventions: Sleep Baby

- Difficulty maintaining alertness

- Possibly sleepy feeder

- Weight gain and developmental milestones may be affected.

- Considerable effort is required to elicit a reaction

- More intense stimulation than expected

- Infant massage & tactile inputs

- Alerting smells & sensations

Detecting sleepy babies can be challenging for caregivers, as they might not perceive excessive sleepiness as a cause for concern. In fact, an overly sleepy baby might be viewed positively. However, excessive sleep can lead to missed interactions, activities, and engagement opportunities crucial for development, potentially resulting in challenges later in childhood or adolescence. These challenges may manifest as descriptions of the child being unmotivated or lacking engagement. Often, low-registration children go unnoticed for extended periods. Therefore, increasing parent coaching is essential if caregivers express concerns about a sleepy baby. Educating caregivers about the importance of alertness and exploration during infancy is crucial to instilling a sense of urgency in promoting healthy development.

- ASI® Interventions: Clumsy Baby

- Persistent head lag

- Asymmetrical or uncoordinated motor efforts

- Difficulty maintaining balance during sitting, standing, crawling, and walking

- Frequent and high-intensity swinging, carrying, dancing

- Babywearing

- High vestibular and proprioceptive input

We might recognize a clumsy baby by delayed motor milestones. We will need to educate caregivers about providing more input and motor experiences.

- ASI® Interventions: Disorganized Baby

- Prefer familiar tasks and activities/repetition

- May become distressed at novelty

- Difficulty negotiating the environment

- Add incremental changes to gradually increase/extend demands

- Introduce novelty with a graded but persistent approach

Parent coaching is crucial for caregivers of disorganized babies to prevent the dyad from becoming stuck in repetitive patterns during this critical growth phase. By providing guidance, caregivers can ensure that they are able to increase or extend their demands on the child, facilitating their transition to a new and higher level of development.

Environmental Supports & Adaptations

- Mismatch usually shows up in the environment.

- Support the caregiver in problem-solving reasonable environmental changes.

- If removal of the expectation is the only response, reactivity may increase with age and grow more dominant in interference with family activities.

Managing the environment is crucial in supporting both the caregiver and the child in their co-regulation journey. Often, there's a disconnect between the parent's environment, which is designed to meet their needs, and the child's needs. During home visits or interviews, it's important to identify these environmental structures that may not support the child's regulation. By working with the caregiver to develop a safe environment tailored to the child's needs, we can create a space conducive to effective co-regulation.

Differentiating Types of Regulation

- Emerging Self-Regulation

- Able to participate in a group with similar-aged peers

- Can join play in progress

- Able to adjust behavior to cues

- Able to lead or follow

- Collects information from the environment

- Changes gears relatively easily

- Recovers relatively quickly

- Difficulty Transitioning to Self-Regulation

- Struggles to join or remain in a group (without help)

- Disrupts play in progress

- Struggles to turn off a behavior, even when prompted (without help)

- Appears to only lead an action (without help)

- Overly upset when having to transition (without help)

- Takes a long time to recover (without help)

Articulating the difference between typical development and regulation challenges can indeed be challenging, especially during the notorious "terrible twos" phase. Children who are typically developing during this stage may still experience upsets but can generally join ongoing play or adjust their behavior once they become regulated. They can take on various roles in play, adapt to changes in the environment, and recover quickly from upsets.

On the other hand, children who struggle with regulation may exhibit disruptive play behavior, have difficulty taking on different roles, and remain overly upset without assistance. While they may eventually regulate with help from caregivers or therapists, they rely heavily on co-regulation and have not yet developed self-regulation skills independently. Identifying and understanding these differences can guide interventions and support strategies for children and their caregivers.

Case Dyad: 18-month-old Child and Caregiver

- Child Factors

- Asian-American

- Missing motor milestones

- ‘Content’ to sit alone for hours

- No independent transitional movements observed:

- From back to belly

- From sitting to crawling

- From sitting to standing

- Waits for parent to pick up and reposition.

- Cries if placed on back instead of upright sitting

- Parent/Family Factors

- Birth parents

- First child

- Parents unconcerned

- Personal & Cultural preferences/expectations

- Difficulty developing goals for the Early Intervention period

- Goal:

- Walking

In this case, it's evident that the child is experiencing delays in motor development, particularly in achieving milestones related to transitional movements. The child's reliance on the parent to reposition them and their discomfort when placed on their back suggests a lack of independent mobility and potential sensory discomfort.

The parents' lack of concern may stem from cultural expectations or personal preferences regarding child behavior. Their primary goal of getting the child walking reflects a desire for the child to meet developmental milestones perceived as important.

To address this situation effectively, it's crucial to educate and support the parents about the importance of early motor development and the potential impact of delays on the child's overall development. Working collaboratively with the family, therapists can develop goals that focus on achieving walking, promoting foundational motor skills, and addressing any underlying sensory issues.

Interventions may include providing strategies to encourage independent movement, such as promoting tummy time and facilitating transitions between positions. Additionally, supporting the child's sensory needs and promoting engagement in play activities that promote motor development can be beneficial.

Cultural considerations should also be taken into account when developing interventions, ensuring that strategies are culturally sensitive and align with the family's beliefs and preferences. Ultimately, the goal is to support the child's development in a way that respects the family's values while addressing their concerns and promoting optimal outcomes.

Assessment and Treatment Approach

- Bayley Motor Scale & Adaptive Skills (team)

- The family declined early intervention services

- Culturally-concordant EI occupational therapist

- Strong motor program addressing facilitation and activation of muscle groups

- Sensory-based assessment

- Parent coaching

It's unfortunate that the family declined early intervention services, but it's essential to respect their decision while acknowledging the potential benefits of intervention. If the family had continued with services, a culturally concordant early interventionist would be crucial in providing support that aligns with the family's cultural beliefs and values.

Assessment using a team-based approach, such as the Bailey Motor Scale and adaptive skills assessment, can provide valuable insights into the child's developmental needs. A strong motor program focusing on foundational aspects of motor movement, with an emphasis on facilitating and activating relevant muscle groups, would be essential.

Sensory-based assessment would also be important to identify any sensory issues that may be impacting the child's motor development. Additionally, parent coaching would play a significant role in supporting the family in understanding and implementing strategies to promote the child's motor development at home.

While the family declined services in this case, it's essential to remain open to future opportunities for support and intervention should they reconsider their decision. In the meantime, providing the family with information and resources to support their child's development at home may be beneficial.

Case Dyad: 25-month-old Child and Mother

- Child Factors

- Hispanic

- Youngest child

- No verbal speech

- Breastfeeding for comfort

- Protracted tantrums

- Aggressive play

- Required nearly constant physical contact

- Unable to soothe to sleep

- Parent/Family Factors

- Birth parent

- Married mother of 7

- Visits conducted w/in-person interpreter

- 3 of 7 with dev delays

- Goals:

- to wean

- to leave the room at bedtime

- to play with sibs without support

This dyad faced significant challenges related to the child's developmental delays and the mother's desire to address specific issues, such as weaning the child, promoting independence in bedtime routines, and playing with siblings. The child's ASD diagnosis added another layer of complexity to the situation.

During in-person visits conducted in the family home with the assistance of an interpreter, it would be important to take a holistic approach to assessment and intervention. This could involve assessing the child's communication skills, sensory needs, and emotional regulation and providing support and guidance to the mother in addressing her goals.

For example, strategies to support the weaning process could include gradually reducing breastfeeding sessions while introducing alternative comfort measures for the child. Teaching the child alternative methods of self-soothing could also be beneficial, such as providing comfort objects or using calming sensory activities.

Addressing the child's difficulty with independent play and bedtime routines could involve implementing structured routines and visual schedules to promote predictability and autonomy. Additionally, providing support and guidance to the mother in managing protracted tantrums and aggressive play behaviors could help improve the dyad's overall functioning.

Overall, a collaborative and family-centered approach, with input from an interdisciplinary team of professionals, would be essential in addressing the complex needs of this dyad and supporting positive outcomes for both the child and the mother.

Assessment and Treatment Approach

- Sensory-based Questionnaire in Spanish

- Extensive parent coaching w/ interpreter

- Described the co- to self-regulation process

- Exploration of sensory strategies for calming

- The parent opted for abrupt weaning

- Bedtime remained challenging due to room sharing

- Structured routines/schedule

The treatment was tailored to address the child's sensory needs and promote the transition from co-regulation to self-regulation while also supporting the mother's goals, such as weaning the child and improving bedtime routines. The use of a sensory-based questionnaire in Spanish allowed for a culturally and linguistically appropriate assessment of the child's sensory needs.

Parent coaching played a central role in helping the mother understand and respond to her child's unique needs, particularly in the context of having multiple children with varying developmental profiles. Strategies focused on sensory regulation, such as providing calming sensory activities, were implemented to support the child's emotional regulation.

The mother's decision to abruptly wean the child highlighted the importance of providing her with information and support to navigate this transition successfully. Parent education helped her understand why her youngest child responded differently than her other children, which likely contributed to her ability to shape her behavior and adapt to the child's needs.

Despite ongoing challenges with bedtime routines due to room sharing with siblings, structured routines and schedules were implemented to promote predictability and consistency for the child. Overall, the treatment approach emphasized parent-directed support and collaboration to address the complex needs of the dyad effectively.

Case Dyad: 30-month-old Child and Caregiver

- Child Factors

- Black

- Intrauterine exposures

- History of multiple ACEs

- Avoided loving touch

- Difficult interactions with family dog

- Intolerant of hair care

- Limited intake (low variety)

- Caregiver/Family Factors

- White

- Married mother of 2 teen boys

- Foster > Adoption (in process)

- Newly fostering infant sister

- Goals:

- mutual bonding needs

- self-care routines

- expand diet

Our final case dyad is a 30-month-old child and caregiver. The caregiver is a married mother of two teen boys who began fostering a child with intrauterine exposures. Due to multiple ACEs, the child avoided loving touch and had difficult interactions with the senior dog. She was also resistant to hair care and had limited food intake. The family was working towards adoption. It was during this process, they began fostering this child's younger sister as an infant.

This family's goals were mutual bonding needs, self-care routines, and expanding her diet.

Assessment and Treatment Approach

- Dual Sensory Assessment (Caregiver & Child)

- SPM-2 Adult Form

- SPM-2 Toddler Form

- (SPM-2 Infant Form)

- Extensive parent coaching re: CG's own profile and the impact of the mismatch

- Environmental impact on regulation

- Increasing volitional choices by the child

- Development of a sensory room

We completed a dual sensory assessment of both, which provided a lot of insight into the adoptive parent's and the child's profiles, and developed a sensory room. With supported co-regulation, the caregiver could reflect before responding, getting feedback from the child, which might reinitiate their reflection, move on to skills and efficacy, and then increase bonding.

Supported Co-Regulation

Here is a graphic that I created that hopefully summarizes much of what we have talked about today.

Figure 6. Supported co-regulation.

Summary

We have covered all of the learning outcomes. Let's now go to the exam poll.

Exam Poll

1) Self-regulation...

The correct answer is all of the above.

2) What is co-regulation?

The correct answer is B, as co-regulation is an interactive process of regulatory support.

3) How can you teach and coach self-regulation?

The answer is all of the above.

4) Which of the following is TRUE about the cycles of regulation?

C is correct because as self-regulation grows, co-regulation diminishes. It does not disappear, but it does diminish.

5) What is the key to assessing co-regulation?

The key to assessing co-regulation is to assess both the child and the infant, so the answer is B.

Thanks for participating today. I hope this is helpful for your practice.

References

Aureli, T. et al. (2022). Mother-infant coregulation during infancy: Developmental changes and influencing factors. Infant Behavior & Development, 69, 101768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2022.101768

Boukydis, C.F.Z. et al. (2004). Clinical use of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale. Pediatrics, 113. 679. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/113/Supplement_2/679.full.html

Brazelton, T.B. & Nugent, J. K. (2011). Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Fair-Field, T. (2017). Early co-regulation in infants and young children. Occupationaltherapy.com.

Gottman Institute. (2024). The research: The still-face experiment. The Gottman Institute Blog. https://www.gottman.com/blog/research-still-face-experiment/

ILARC Policy Research Group (2018). The parent-child dyad in the context of child development and child health. Illinois ACEs Response Collaborative. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1781292/the-parent-child-dyad-in-the-context-of-child-development-and/2512938/

Lester, B.M. & Tronick, E. (2004). The NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS). Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Murray, D.W. et al. (2015, January). Self-regulation and toxic stress report 1: Foundations for understanding self-regulation from an applied perspective. OPRE report # 20115-21: Office of Planning, Research, & Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/report_1_foundations_paper_final_012715_submitted_508_0.pdf

Pinto, T.M. & Figeroa, B. (2022). Measures of infant self-regulation during the first year of life: A systematic review. Infant & Child Development, 32. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2414

Rosanbalm, K.D. & Murray, D.W. (2017, October). Caregiver co-regulation across development: A practice brief. OPRE Brief #2017-80: Office of Planning Research, & Evaluation, Administration for Children & Families, U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/co-regulation-birth-through-young-adulthood-practice-brief

Rothbart, M. & Gartstein, M. (1998). Infant Behavioral Questionnaire, Revised.

Smith, C.G. et al. (2022). Anxious parents show higher physiological synchrony with their infants. Psychological Medicine, 52(14). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720005085

Smith, L.M. (2005, February). NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale manual. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 26(1). 68. https://journals.lww.com/jrnldbp/fulltext/2005/02000/nicu_network_neurobehavioral_scale_manual.14.aspx

Smith Roley, S. et al. (2016, December) Ayres Sensory Integration® for infants and toddlers. http://www.instsi.co.za/blikmin_saisi/files//04 SAISI Integration for Infants and Toddlers_Article_c WEB.pdf

Stockdale, L.A. et al. (2020). Infants’ response to a mobile phone modified still-face paradigm: Links to maternal behaviors and beliefs regarding technoference. Infancy, 25(5). 571-592. https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12342

Taipale, J. (2016). Self-regulation and beyond: Affect regulation and the infant-caregiver dyad. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00889

Wass, S.V. et al. (2019). Parents mimic and influence their infant’s autonomic state through dynamic affective state matching. Current Biology, 29, 2415-2422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.016

Woolard, A. et al. (2022). Parent-infant interaction quality is related to preterm status and sensory processing. Infant Behavior & Development, 68, 101746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2022.101746

Citation

Fair-Field, T. (2024). Early co-regulation in the infant and parent dyad. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5701. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com