Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Evidence-Based Approaches: A Pediatric Perspective Of The Occupation Of Sleep, presented by Nicole Quint, Dr.OT, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify at least 3 common types of sleep disturbances.

- After this course, participants will be able to compare and contrast the objective and subjective signs and symptoms of sleep disturbances and their impact on areas of occupation.

- After this course, participants will be able to apply the use of evidenced-based strategies to improve patient functional outcomes.

Introduction

Thank you for joining me today. I am pleased to share valuable resources to enhance our understanding of pediatric sleep assessment and intervention. In the realm of child sleep evaluation, employing evidence-based tools is crucial. I have curated a resource packet for you, which includes various tools that align with our approach, namely the "Hit the SAAQ" method.

Firstly, I'd like to draw your attention to the "Children's Sleep Diary", an evidence-based tool freely accessible online. This diary is invaluable in understanding a child's sleep patterns. Its comprehensive nature encompasses factors like sleep duration, architectural considerations, and sleep quality, all of which are pivotal aspects of our forthcoming discussion.

Another instrument I've included is the "Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire." Designed for preschool and school-aged children, this user-friendly tool covers essential aspects that align with our approach. It delves into sleep duration and explores elements such as sleep architecture and quality, setting a foundation for a holistic understanding of a child's sleep habits.

In addition to these, I've included another sleep diary that, while having a more juvenile appearance, offers diverse information. This tool allows for flexibility, enabling you to tailor your approach based on specific needs, whether it's focusing on wake-up times, total sleep duration, or gauging how a child feels during the day – an insightful aspect that can be instrumental in understanding the correlation between sleep and daily functioning.

It's essential to note that while the emphasis is on comprehensive assessment, the focus on specific sleep hours may not be as pivotal as initially perceived, according to recent research. However, leveraging this data can still be motivational for certain individuals.

I've also provided a tool from the National Sleep Foundation, a comprehensive chart Jason and I developed specifically for our course – a visual aid supporting the "Hit the SAAQ" approach. This chart not only assists in gathering necessary information about the client and their family but also facilitates a Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO) approach, aiding in formulating and monitoring interventions.

As you explore these resources through the provided link, including QR codes (in the handout) for convenient access, please feel free to reach out if any technical issues arise. My email, displayed in the handout, is a direct line for alternative formats or additional assistance. I appreciate your commitment to this course, and I'm confident these resources will enrich our collective knowledge of pediatric sleep intervention.

What is Sleep Health?

- Sleep is part of a holistic vision of health

- Children should spend most of the 24-hour day sleeping

- What makes up good sleep (Hit the"SAAQ")

- Sleep Duration

- Architecture

- Sleep Duration

- Architecture

- Address Sleep Disorders

- Quality

It's essential to view sleep not just in terms of hours spent in slumber but as an integral component of overall well-being. When discussing sleep health, we're examining a holistic perspective, encompassing various aspects contributing to a child's overall well-being.

Children, in particular, devote a significant portion of their day to sleep, making it a cornerstone of their daily routine. To understand and promote sleep health, we'll explore four key elements. First and foremost is sleep duration, emphasizing the importance of time spent asleep. This aspect gains significance when considering non-REM sleep, a specific phase that plays a crucial role in overall sleep quality.

Moving on to the 'A' in our framework, we encounter sleep architecture. This element focuses on understanding how sleep cycles progress. Examining the patterns and transitions within these cycles provides valuable insights into a child's sleep health.

Simultaneously, we cannot overlook the impact of sleep disorders. The landscape of sleep disorders is diverse, and it's noteworthy that children with various diagnoses or disabilities often grapple with comorbid sleep issues. Recognizing when these issues fall within the scope of occupational therapy intervention or require referral to a specialist is a key consideration.

Lastly, we combine these elements to form the sleep quality concept. Combining sleep duration and architecture and addressing sleep disorders results in a comprehensive sleep health evaluation. This multifaceted approach allows us to discern when to intervene from an occupational therapy standpoint and when it's prudent to collaborate with medical professionals or physicians.

Sleep health for children is a nuanced interplay of duration, architecture, disorders, and quality – a holistic perspective that goes beyond mere hours on the clock. By comprehensively understanding these components, we can navigate the complexities of pediatric sleep and contribute to fostering a foundation of overall well-being.

Basics of Sleep

- Restorative

- Non-REM sleep: “Quiet” sleep

- Blood supply to muscles is increased

- Energy restored

- Tissue growth and repair occur

- Important hormones released for growth and development

- National Sleep Foundation (2018)

- Adaptive

- Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep: “Active” sleep

- The primary activity of the brain during early development

- Directly impacts mental and physical development

- REM and nREM alternate (50/50)

- 50% of baby’s time is sleeping

- Cycles are 50 min each, 4 cycles within sleep

- 90 min at preschool (30/70)

Understanding the fundamentals of sleep is crucial to comprehending its significance in promoting overall well-being. So, why do we sleep? The answer lies in the dual nature of sleep – restorative and adaptive.

From a restorative standpoint, we delve into non-REM sleep, characterized by its tranquility. During this phase, the body undergoes essential processes for restoration. Energy levels are replenished, tissues experience growth and repair, and crucial hormones are released, particularly vital for the growth and development of children and adolescents. Additionally, an increased blood supply to the muscles contributes to the overall physical recovery. While non-REM sleep is predominantly serene, subtle movements may occur.

Conversely, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is considered the adaptive form of sleep, marked by increased brain activity. It plays a pivotal role in mental and physical development, especially during the early stages of life. Notably, the proportion of REM sleep decreases with age, guiding the development trajectory.

The sleep architecture, characterized by the alternating cycles of REM and non-REM sleep, evolves throughout a person's life. In infancy, sleep cycles are approximately 50 minutes each, with about 50% of a baby's time spent sleeping. As children progress to preschool age, the ratio shifts to around 30% REM and 70% non-REM sleep, with longer 90-minute cycles. These changes in sleep architecture reflect the dynamic nature of sleep as children grow and develop.

It's important to recognize these nuances, as they lay the foundation for a deeper comprehension of sleep patterns and needs in children. While we won't delve into the specifics of adult sleep, it's worth noting that sleep architecture continues to undergo intriguing changes throughout the lifespan. This foundational knowledge is a crucial tool in our exploration of pediatric sleep health. This graph is adapted from an article from 2022 (Figure 1).

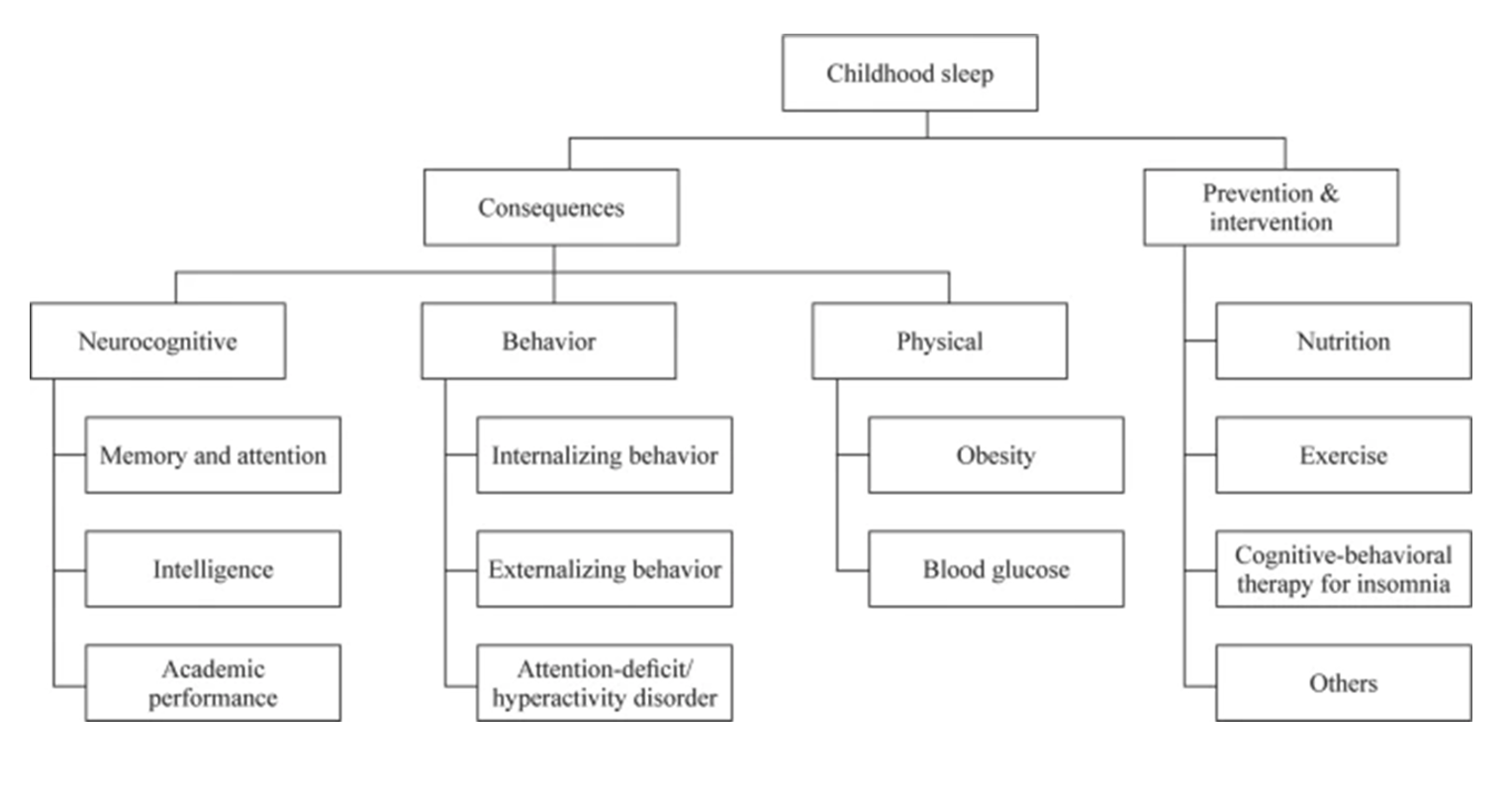

Figure 1. Areas of childhood sleep (Click here to enlarge the image).

Exploring childhood sleep extends beyond understanding its intricacies to recognize the potential consequences of inadequate sleep and the avenues for prevention and intervention. This insightful chart encapsulates the holistic view of childhood sleep, encompassing the repercussions of insufficient sleep and the strategies for mitigating these effects.

Delving into the consequences, we encounter significant impacts across neurocognitive, behavioral, and physical domains. Neurocognitively, inadequate sleep is linked to direct implications on academic performance, highlighting the essential role of quality sleep in cognitive functions. Behavioral consequences manifest as internalizing and externalizing behaviors, contributing to various challenges. The mention of ADHD in this context is nuanced – while not suggesting a causal relationship, insufficient sleep may exhibit traits resembling ADHD, including attention deficits and hyperactivity.

The physical ramifications extend to obesity and blood glucose levels, revealing the intricate connection between sleep and overall physical health. These insights stem from a thorough investigation, likely a systematic review or meta-analysis, reflecting a robust examination of existing literature.

Shifting to prevention and intervention, the chart emphasizes the importance of holistic approaches. Nutrition and exercise emerge as crucial components, recognizing their impact on sleep health. Additionally, cognitive-behavioral therapies tailored for insomnia stand out as effective interventions. The spectrum of insomnia, diverse in its manifestations, underscores the need for targeted and personalized approaches.

As we explore these consequences and interventions, we aim to acknowledge the potential challenges and equip ourselves with knowledge of preventive measures and effective interventions. By embracing a comprehensive approach that includes lifestyle factors, therapeutic interventions, and tailored strategies, we can promote optimal sleep health in children, mitigate the identified consequences, and foster overall well-being.

Sleep in Children

- Occupational Therapy Framework Sleep:

- Rest

- Sleep preparation

- Sleep participation

- Sleep is a primary occupation of children:

- School-aged children should sleep up to 38% of their day

- Up to 20-40% of children have irregularities in sleep

- Children's sleep has decreased by 70 minutes during the 20th century

Sleep is the primary occupation of children. It's essential to view sleep not just in terms of hours spent in slumber but as an integral component of overall well-being. When discussing sleep health, we examine a holistic perspective, encompassing various aspects contributing to a child's overall well-being.

Children, in particular, devote a significant portion of their day to sleep, making it a cornerstone of their daily routine. To understand and promote sleep health, we'll explore four key elements. First and foremost is sleep duration, emphasizing the importance of time spent asleep. This aspect gains significance when considering non-REM sleep, a specific phase that plays a crucial role in overall sleep quality.

Moving on to the 'A' in our framework, we encounter sleep architecture. This element focuses on understanding how sleep cycles progress. Examining the patterns and transitions within these cycles provides valuable insights into a child's sleep health.

Simultaneously, we cannot overlook the impact of sleep disorders. The landscape of sleep disorders is diverse, and it's noteworthy that children with various diagnoses or disabilities often grapple with comorbid sleep issues. Recognizing when these issues fall within the scope of occupational therapy intervention or require referral to a specialist is a key consideration.

Lastly, we combine these elements to form the sleep quality concept. Combining sleep duration and architecture and addressing sleep disorders results in a comprehensive sleep health evaluation. This multifaceted approach allows us to discern when to intervene from an occupational therapy standpoint and when it's prudent to collaborate with medical professionals or physicians.

Occupation of Sleep According to the OTPF-4

- Rest

- Engaging in quiet actions that interrupt physical and mental activity

- Engaging in relaxation

- Restoring energy

- Calming

- Renewing interest in engagement

- Engaging in quiet actions that interrupt physical and mental activity

- Sleep Preparation

- Engaging in routines in preparation for sleep

- Grooming, undressing/redressing

- Reading, listening to music

- Addressing the needs of others (partner, children, etc.)

- Ensuring healthy sleep patterns (time to bed, time out of bed--may be culturally driven)

- Securing your home

- Ensuring a comfortable environment (light, sound, bedding, etc.)

- Engaging in routines in preparation for sleep

- Sleep Participation

- Taking care of personal needs for sleep without disruption

- Ceasing activity (electronics, work, etc.)

- Meeting nighttime toileting and hydration needs

- Needs of others (Children, pets, partner, etc.)

- Taking care of personal needs for sleep without disruption

In the context of occupational therapy's approach to sleep, the "OT Practice Framework" fourth edition offers a comprehensive breakdown into three categories: rest, sleep preparation, and sleep participation. Recognizing that sleep is not confined to sleeping, the framework emphasizes the importance of understanding and intervening in various facets of the sleep process.

Of particular interest is the role of sleep preparation, an area where occupational therapy can bring about meaningful change. Addressing rest and sleep preparation contributes to overall sleep participation, forming a crucial continuum. When working with families on sleep-related issues, my approach involves education, practical activities during sessions, and a significant emphasis on family monitoring and home programs. This family-centered care approach ensures that interventions are collaborative, involving families in problem-solving and decision-making.

Exploring the concept of rest, it is described as quiet actions providing a respite from physical and mental activity. This can range from simple moments of relaxation, such as listening to music, to more structured activities like mindfulness or yoga nidra. Identifying and understanding family and child habits and patterns during rest periods is crucial for effective intervention.

Sleep preparation, commonly called sleep hygiene activities, encompasses evening routines. This includes grooming, dressing/redressing, bathing, and engaging in literature or bibliotherapy during story time. The key components are addressing all family members' needs, ensuring a healthy sleep pattern, securing the home, and creating a comfortable sleep environment. Recognizing cultural influences is paramount, allowing for compromises that align with cultural practices and practical constraints, such as school hours.

Lastly, sleep participation involves uninterrupted sleep. Meeting personal needs, ceasing activities, attending to nighttime toileting and hydration, and considering the needs of others contribute to a seamless sleep experience. It underscores the interconnectedness of caring for others and oneself in seeking optimal sleep participation.

In essence, the occupational therapy approach to sleep extends beyond sleeping, encompassing a range of activities and habits that collectively contribute to a child's overall sleep health. Through education, collaboration, and practical interventions, occupational therapy is pivotal in supporting families in fostering positive sleeAeasures to ensure safety. The National Institutes of Health has undertaken a commendable initiative known as the Safe to Sleep campaign, primarily designed to reduce the incidence of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), a deeply concerning and frightening phenomenon.

The campaign promotes a safe sleep environment and highlights the importance of tummy time, recognizing its impact on children's developmental milestones—particularly pertinent to occupational therapists. The Safe to Sleep campaign provides valuable resources and guidelines through its Safe Sleep Environment Protocol.

I have included a link to access free handouts for families on this campaign's website. This is a valuable resource, especially for those working in clinics, schools, or preschools. By ordering these materials, you can equip yourself with essential information and tools to educate families on safe sleep practices. As an advocate for resources, particularly those that are free, I encourage you to explore these materials and integrate them into your practice to benefit the children and families you work with.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)

SIDS Facts

- SIDS

- Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

- Under 1 yearARisk Factors

- Sleep on stomach

- Sleep on a soft surface

- Sleep on or under soft or loose bedding

- Get hot during sleep

- Exposed to cigarette smoke

- Sleep in an adult bed with parents, other children, pets

- Co-Sleeping

- Risk Factors

- Increased risk if:

- An adult smokes, has recently had alcohol, or is tired

- Baby covered by quilt or blanket

- More than one bed-sharer plus the baby

- Baby younger than 11-14 weeks of age

Navigating the risk factors associated with Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) presents a complex challenge, especially when considering that the cause remains unknown and the risk is heightened in infants under a year old. Occupational therapists want to empower and educate families, allowing them to make informed decisions that reduce risk factors without instilling fear.

Understanding the risk factors is key, and our role is to ensure that families are health-literate on this concept. Risk factors include placing infants on their stomachs, utilizing soft surfaces for sleep, incorporating soft or loose bedding, and monitoring temperature, particularly if the infant tends to get hot during sleep. Exposure to cigarette smoke is a significant risk factor that demands careful consideration.

Controversial territory arises when discussing the idea of infants sleeping in an adult bed with parents, other children, or pets. While cultural practices may play a role in this decision, families need to be aware that such arrangements carry an increased risk, especially if the adult has smoked, consumed alcohol, or is fatigued. Co-sleeping risk factors escalate with the number of individuals sharing the bed. Educating families on these risks allows them to make informed decisions based on their values and circumstances.

Factors that increase co-sleeping risks include the baby being covered by quilts, blankets, or comforters, having more than one bed-sharer with the baby, and the infant's age. Babies younger than 11 to 14 weeks are at a higher risk during co-sleeping, emphasizing the importance of considering alternatives or taking additional precautions during this period.

Ultimately, we aim to facilitate open and informed discussions with families, encouraging them to weigh the risks and make decisions aligned with their values and cultural practices. Emphasizing risk reduction strategies and sensitivity to cultural considerations are crucial elements of our role as occupational therapists in this delicate context.

Let's Help the Families! (NIH, 2018)

- How to reduce risks of SIDS and other sleep-related causes of infant death

- Baby on Back to Sleep

- Naps

- Night sleep

- Be careful with swaddling-do not put baby to sleep swaddled if he/she can roll over as this can smother the baby

- Bed

- Firm, flat surface

- Safety-approved crib and mattress

- Fitted sheet with no other bedding or soft items in the sleep area

- No soft objects, crib bumpers, or loose bedding under, over, or near the baby

- Shared Room, not Bed

- Keep baby close to bed but on a separate surface designed for infant

- Minimum first 6 months

- Ideally first year

- Baby on Back to Sleep

How do we help the families? Empowering families with knowledge without inducing fear is the crux of our approach when discussing safe sleep practices. While the topic is frightening, emphasizing that informed decisions can significantly contribute to the baby's safety becomes pivotal. Educating families about key practices is an essential step in this process.

Placing the baby on their back for sleep, including naps, is a fundamental recommendation. Acknowledging the benefits of swaddling, we must caution families against swaddling once the baby can roll over, as this could pose a risk of smothering. The firmness of the mattress might seem uncomfortable to us, but it is a critical safety aspect. A safety-approved crib and mattress are crucial, especially when considering the potential use of hand-me-downs or family heirlooms.

Ensuring a minimalistic sleep environment is vital—using a fitted sheet without additional bedding, avoiding soft objects, and eliminating stuffed animals or crib bumpers. These precautions are essential in preventing potential hazards that could harm the baby during sleep.

When discussing co-sleeping, a compromise could involve having the baby in a shared room on a separate surface designed for infants. This approach maintains proximity while minimizing risks, particularly during the high-risk phase of 11 to 14 weeks.

Recommendations advocate for co-sleeping in a shared room for the first six months, with the ideal scenario being the first year. Beyond the first year, the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) significantly diminishes. These guidelines provide families with a framework for safe sleep practices, allowing them to make informed decisions aligned with their values and circumstances.

- Mothers

- Regular prenatal care

- Avoid smoking, drinking, using marijuana, or illegal drugs

- Pacifier

- Can reduce SIDS

- Do not attach to anything to avoid strangulation

- Breastfeeding

- If it falls out, it’s ok

- Other

- Regular health checkups, vaccines

- Avoid products that claim to reduce SIDS*

- Tummy time

Ensuring regular prenatal care for mothers is a crucial factor in reducing the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). While approaching cases where prenatal care is lacking, it's essential to avoid guilt or shame but rather inform families about the increased risk in a supportive manner. Acknowledging the importance of factors like smoking, drinking, marijuana use, and illegal drugs in elevating risks is part of this comprehensive education.

The role of a pacifier in non-nutritive sucking is widely recognized for its potential to reduce SIDS. However, caution is necessary, emphasizing that the pacifier must not be attached to clothing to prevent strangulation. Breastfeeding is another positive factor in risk reduction, although it's crucial to understand mothers who cannot breastfeed.

Addressing the significance of regular health checkups, vaccines, and avoiding products claiming to reduce SIDS contributes to risk reduction. Encouraging and acknowledging mothers actively participating in community health programs and maintaining consistent health checkups for their infants is vital. The caution against relying on products with unsubstantiated claims is important in the age of online shopping.

Tummy time, supported or unsupervised, is an evidence-based practice to reduce SIDS risk factors. Emphasizing its benefits not only aids in risk reduction but also complements the back sleeping practice. A supportive and informative approach ensures that families know effective strategies and make informed choices to safeguard their infants.

Tired Parents

- Question from parent: “What if I fall asleep while feeding my baby?”

- Answer: “It is less dangerous to fall asleep in an adult bed than on a sofa or armchair, so ask yourself how tired you are, and if you think you might (even slight chance) fall asleep, then choose the bed and remove ALL SOFT ITEMS and BEDDING before you start”

Addressing the reality of tired parents is crucial in discussions about safe sleep practices. An important query that may arise, or should be proactively addressed, is the concern about parents potentially falling asleep while feeding the baby. In providing guidance, it's essential to convey key information: falling asleep in an adult bed is less dangerous than doing so on a sofa or armchair.

Empowering parents with this knowledge helps them make informed decisions about their tiredness. Encourage them to engage in a quick self-assessment of their fatigue level before feeding the baby. Opting for the bed is a safer choice if there's even a slight possibility of falling asleep. Additionally, it's crucial to emphasize the importance of removing all soft items, including top sheets, comforters, and pillows, before starting the feeding session. This proactive measure significantly reduces potential risks to the baby.

Encouraging parents to incorporate this habit into their routine—asking themselves the fatigue question, choosing the bed, and eliminating soft items—provides a practical strategy to minimize risks. Documenting this guidance in their records reinforces the importance of these safe sleep practices and serves as a reference point for ongoing education.

Figure 2 is a picture of me and my cousin from the '70s.

Figure 2. A child from the 1970s with too many soft textures in the bassinet.

Reflecting on past practices, this image offers a vivid snapshot of a bygone era, highlighting the evolution in our understanding of safe sleep environments for babies. The setting, featuring a soft and padded chaise with various plush items like giant and small teddy bears, a homemade baby doll, and pillows, exemplifies an environment modern knowledge recognizes as unsafe.

The nostalgia attached to such images is coupled with an acknowledgment of the progress made in ensuring the safety of infants during sleep. The elements, including the soft material, buttons, and even the crochet Afghan, contribute to an unsafe sleeping space. The photograph is a stark reminder of the strides in enhancing our awareness and practices concerning infant safety.

While the sentiment of "we did things differently in the '70s" resonates, the contemporary understanding underscores the need for continuous improvement and adherence to safer sleep guidelines. Acknowledging the experiences of past generations, it becomes evident that the pursuit of knowledge has refined our approach to ensuring the well-being of infants, reinforcing the notion that we must continually strive to do better for the next generations.

Assessment

When doing assessment intervention, we want to discuss hitting the "SAAQ" and the theoretical frameworks we will use. I love this picture in Figure 3.

Figure 3. An example of how you can have the child draw how they sleep.

This adorable drawing comes from my nephew, and it's quite charming to see how kids interpret the idea of sleep through their art. Despite the levitating position and the not-so-comfortable-looking pillow, the portrayal has a unique and imaginative quality. Encouraging children to draw pictures of themselves sleeping is a wonderful way to get them thinking about the topic and gaining more buy-in.

During our educational sessions, I remember doing this activity with him and discussing why sleep is important. It was during these conversations that he created this cute drawing. I'm grateful he allowed me to share it because it adds a personal touch to the experience.

The Approach: Hit the “SAAQ”

The "SAAQ" approach is a framework co-developed by Jason Browning and me, featuring four key components. This approach addresses sleep duration, architecture, sleep disorders, and quality, collectively steering individuals toward optimal sleep health.

Sleep duration involves assessing the overall length of one's sleep. Understanding the time spent in various sleep cycles, typically lasting around 50 to 90 minutes for children, provides crucial insights into sleep patterns. These cycles can vary in number and duration, underscoring the importance of recognizing individual variations.

Moving on to sleep architecture, we explore sleep's intricate cycles and phases. Considering that individuals may experience multiple cycles throughout the night, with durations influenced by age and other factors, delving into these nuances helps create a comprehensive view of sleep quality.

The "A" in the approach prompts us to address sleep disorders. Recognizing and understanding various sleep disorders is vital, especially when dealing with children who may have comorbid sleep issues linked to specific diagnoses or disabilities. Identifying when occupational therapy interventions can be beneficial or when a referral to a specialist is warranted is a crucial aspect of this component.

Finally, the "Q" stands for quality, encompassing the synthesis of sleep duration, architecture, and the management of sleep disorders. Focusing on these three pillars can enhance overall sleep quality and contribute to the broader concept of sleep health.

Sleep Assessments

Sleep Assessment Table Resource

Sleep Area of Assessment | Questionnaire |

Sleep Latency | PSQI, CSHQ*, MCSR, SSR, HBSC, LRSHQ |

Sleep Efficiency | PSQI, LRSHQ |

Sleep Duration | PSQI, ASHS, CSHQ*, SSR, HBSC, LRSHQ, SWQ |

Sleep Disturbances | PSQI, CSHQ*, ASHS, SSR, SWQ, MCSR, LRSHQ |

Daytime Sleepiness/ Dysfunction | SWQ, PSQI, CSHQ*, ASHS, HBSC, SSR |

Bedtime | SWQ, LRSHQ, SSR, ASHS, CSHQ*, PSQI |

Assessments: Adolescent Sleep Hygiene Scale (ASHS) Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ)* Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Meijer Child Self Report (MCSR) Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Life Rhythms and Sleep Habits Questionnaire (LRSHQ) Sleep Self Report (SSR) Sleep-Waking Questionnaire (SWQ) Adapted from: (Phillips et al., 2020, p. 63) | |

In sleep assessment, various questionnaires and tools exist to delve into various facets of sleep health. A chart guides professionals through this landscape, offering insights into specific assessment areas and the corresponding questionnaires aligned with each aspect.

Firstly, we consider "Sleep Latency," examining the duration of falling asleep. The questionnaires pertinent to this aspect include CSHQ, CSD, and DBAS, each providing a unique perspective on this dimension.

Moving on to "Sleep Efficiency," this parameter assesses the ratio of time spent asleep to the total time spent in bed. Questionnaires like PSQI and the "Life Rhythms and Sleep Habits Questionnaire" are designed to shed light on sleep efficiency.

The third dimension, "Sleep Duration," delves into the time spent in slumber. While various tools are available for this assessment, the CSHQ is a versatile option covering multiple dimensions of sleep health.

Addressing "Sleep Disturbances," these questionnaires aim to identify disruptions during sleep, including night awakenings. The tools encompass CSHQ, SAS, DBAS, SRS, and WASO, offering a comprehensive perspective on sleep disturbances.

Lastly, "Daytime Sleepiness and Dysfunction" explores the consequences and impacts of sleep patterns during waking hours. The questionnaires covering this dimension range from CSHQ to ESS, MFSS, AESS, SSS, and SFI.

The Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) emerges as a standout tool because it covers multiple facets of sleep assessment. Its accessibility and versatility make it an invaluable resource for professionals seeking a holistic view of sleep health. As professionals explore these tools, factors such as availability, potential costs, and language options should be considered. The accompanying packet will provide additional details, including information on tools available in different languages, enriching the repertoire of professionals engaged in sleep assessment.

Infant Sleep Assessment Options

- Infant Sleep Questionnaire

- Sleep and Settle Questionnaire

- BEARS (Bedtime problems, Excessive sleepiness, Awakenings, Regularity, Snoring)

- Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children

- Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire

In exploring sleep-related information, it's crucial to delve into bedtime habits and routines, aptly encapsulated in the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ). This comprehensive tool provides valuable insights into the sleep patterns of individuals, shedding light on various aspects.

The BEARS assessment, conveniently available online at no cost, caters to the toddler and preschool age group. BEARS, an acronym for bedtime problems, excessive sleepiness, awakenings, regularity, and snoring, is a useful guide for understanding sleep-related challenges in this demographic.

Furthermore, we mustn't overlook the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC), another noteworthy resource accessible for a comprehensive evaluation of sleep disruptions among children.

An additional resource of significance is the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire, a valuable tool designed to assess infant sleep patterns. The link to this questionnaire is conveniently provided at the conclusion of this narrative to facilitate your access.

These sleep assessment tools offer a nuanced understanding of sleep-related nuances, contributing to a more informed and targeted approach to addressing sleep concerns in children.

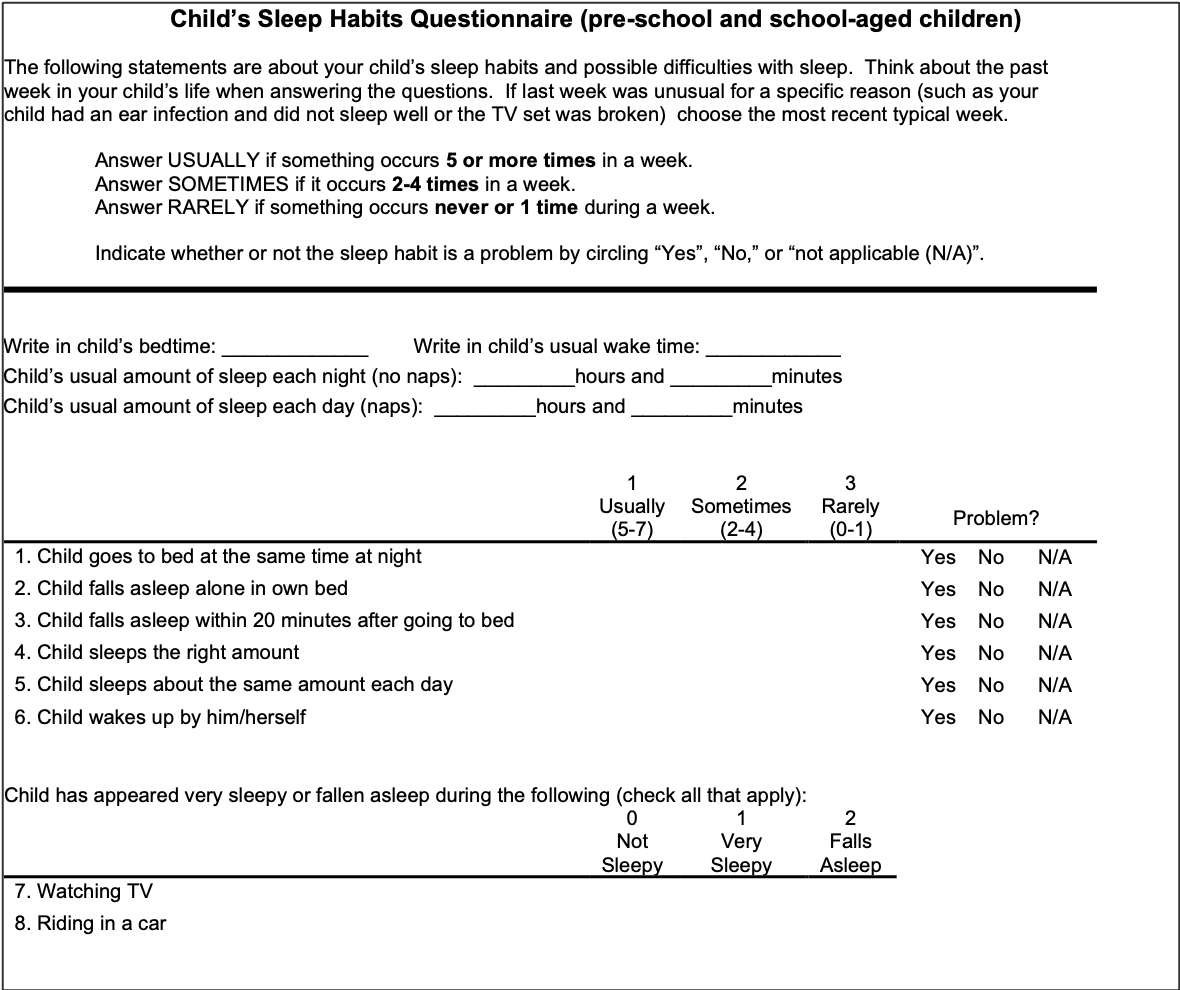

Assessment: CSHQ (Obtains SAQ)

Here's the CSHQ in Figure 4.

Figure 4. An example of the CSHQ (https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1nHZGd9CkyvJKC1RVNwzeFcVNc-L5e24w?usp=sharing).

Within the provided packet, we explored an array of sleep-related metrics encompassing sleep duration, addressing sleep concerns, and evaluating sleep quality. While these aspects offer valuable insights, it's essential to acknowledge the complexity of sleep architecture, a dimension that extends beyond conventional questioning.

Unraveling the intricacies of sleep architecture poses a challenge, as conventional inquiries might not suffice. For instance, asking someone about the quality of their sleep may yield subjective responses, but delving into specific architectural details like REM (rapid eye movement) sleep requires more sophisticated measurement tools. While some individuals may utilize smartphone apps to track aspects such as REM, deep sleep, and core sleep, a comprehensive understanding of sleep architecture demands a more nuanced approach.

To facilitate this nuanced exploration, a specific link has been provided for a resource that delves into sleep architecture. This shortcut enables a more direct and efficient access point, bypassing the need for an extensive search process. Recognizing the significance of comprehending sleep architecture contributes to a more holistic assessment of one's sleep health.

Sleep Recommendations

Age | Recommended hours of sleep | |

Infants (0-3 mo) | 14-17 hours | Including naps |

Infant (4-11 mo) | 12-16 hours | Including naps |

Toddlers (1-2 yrs) | 11-14 hours | Including naps |

Preschoolers (3-5 yrs) | 10-13 hours | Including naps |

School-aged (5-13 yrs) | 9-11 hours |

|

Adolescents (14-17 yrs) | 8-10 hours |

|

In exploring sleep-related considerations, I've provided comprehensive sleep recommendations, guiding understanding of the optimal duration for different age groups. The significance of sleep duration becomes apparent when considering the vast variations across age categories, acknowledging the flexibility within these guidelines.

For infants aged zero to three months, a substantial sleep duration of 14 to 17 hours, including naps, is emphasized. As we move through developmental stages, flexibility remains key. Infants aged 4 to 12 months are recommended to sleep for 12 to 16 hours, including naps. Toddlers within the age range of 1 to 2 years are advised to aim for 11 to 14 hours, encompassing naps. Preschoolers aged 3 to 5 years should target 10 to 13 hours of sleep, once again incorporating nap times into the equation.

The sleep duration recommendations continue with school-aged children aged 6 to 12 years, suggesting 9 to 11 hours of sleep. Adolescents aged 13 to 18 years are recommended to get 8 to 10 hours of sleep per night. While acknowledging the challenges teenagers face in meeting these recommendations, it's crucial to recognize that emerging research emphasizes the importance of sleep quality and architecture over strict adherence to duration.

Understanding the multifaceted impact of sleep on academic performance and behavior, we delve into the intricate dynamics wherein even slight improvements in sleep duration can yield positive outcomes. Research indicates that incremental enhancements, as short as half an hour, correlate with improved academic grades and standardized test scores. As we navigate this landscape, it becomes evident that addressing sleep concerns encompasses the quantity of sleep and the broader spectrum of sleep architecture and quality, significantly influencing overall well-being.

Variability in Sleep

- Infants: High

- Toddlers: Low

- Communication: “I’m a tired baby”

- Fuss

- Cry

- Rub eyes

- Unique gestures

- Total Hours

- 9 hours minimum

- Up to 18 hours

- Awake time ranges from 1-3 hours

- Take Away

- Don’t worry about the hours of sleep

- Focus on building positive SAFE sleep routines (quality)

- Communication: “I’m a tired baby”

In considering the variability in sleep patterns across different age groups, it becomes evident that infants exhibit a high degree of variability, while toddlers demonstrate a more stabilized pattern, albeit with lower variability. Understanding the cues infants provide when tired, such as fussiness, crying, or rubbing their eyes, allows caregivers to respond appropriately to their sleep needs.

Highlighting the broad range of normalcy, infants can sleep at least nine to 18 hours. The window for awake time spans from one to three hours, offering caregivers a flexible framework to cater to each infant's unique needs. The key takeaway here is to prioritize the establishment of positive and safe sleep routines, recognizing that the focus should extend beyond the quantity of sleep to encompass its quality and safety.

Addressing a query about long-term melatonin use, it's acknowledged as a pertinent topic to be discussed in due course. As for assessment questionnaires for the early intervention age group, there isn't a one-size-fits-all approach. The Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), presented with some modifications, is a comprehensive tool that provides a wealth of information to guide assessments. The emphasis lies not on determining the "best" tool but on selecting one that effectively gathers the necessary information to inform interventions and improve sleep quality.

Understanding the eagerness to delve into the intricacies of sleep architecture, it's assumed that this aspect will be addressed in due time. As we navigate through the wealth of information, the focus remains on equipping caregivers with the tools and insights necessary for fostering optimal sleep environments and habits for children.

Consistent Bedroom Routine

- Sleep hygiene: 3-4 quiet activities each night

- Set a sleep schedule (same sleep times for all)

- EBP: research study with 130 infants (7-18 mos)

- EBP: research study with 200 toddlers (18-36 mos) (Mindell et al., 2006)

- Control: usual routine

- Routine: bath, massage/lotion, quiet activities (cuddles, stories, etc.; talking about day for toddlers

- Other options: singing, going bathroom, brushing

When working with children, particularly the younger ones, the research underscores the pivotal role of sleep hygiene and consistent bedtime routines. A seminal longitudinal study by Mindell in 2006 laid the foundation for our understanding of the impact of sleep and bedtime routines on infants and toddlers. Mindell, a renowned researcher in infant and toddler sleep, emphasizes the significance of establishing consistent practices for optimal sleep.

The findings from this study, which involved 130 infants aged seven to 18 months and 200 toddlers aged 18 to 36 months in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), indicated that a structured bedtime routine significantly contributes to improved sleep outcomes. The established routine included activities such as bath, massage, lotion, quiet activities (cuddles, stories, singing), discussing the day, going to the bathroom, brushing teeth, bath, diaper change, and concluding with the crucial element of "lights out."

Consistency in the bedtime routine emerged as a key factor, showing positive effects on sleep duration and quality. Importantly, the benefits of a consistent sleep schedule extend beyond childhood, impacting long-term health and disease risks.

However, it's acknowledged that implementing such routines may pose challenges, especially for children with specific needs or diagnoses like autism. The collaborative approach involves negotiating and problem-solving with families to tailor the routine to each child's unique requirements. While this evidence-based approach is effective for all children, addressing sleep concerns, as we will discuss later, requires a nuanced understanding and collaborative effort to build and sustain positive sleep habits.

Rest/Sleep Prep

- Bibliotherapy

- Warm bath

- Physical environment

- Bedtime/Wake time

- Healthy food

- Daytime exercise

- Pause electronics

- Sunlight

- Timing of dinner

- Mother perceived work flexibility

Integrating evidence-based practices within the occupational therapy domain aligns with the "OT Practice Framework" to address rest and sleep preparation. The visual support offered here encompasses various categories, each substantiated by research:

Bibliotherapy finds its place as a method of utilizing stories to aid in rest and sleep preparation. This approach recognizes the power of narratives in facilitating a transition to sleep.

Warm baths emerge as an effective strategy, acknowledging their ability to promote relaxation and prepare individuals for sleep.

Consideration of the physical environment becomes crucial, emphasizing the importance of a comfortable and clutter-free sleep space, particularly focusing on providing a comfortable bed.

Establishing a consistent bedtime and waketime routine proves vital, as research supports the positive impact of a regular sleep schedule.

Acknowledging the role of a healthy diet in contributing to quality sleep, despite potential challenges in instilling these habits, underlines the Healthy Food and Diet category.

Daytime exercise and exposure to sunlight are advocated, recognizing their potential benefits for circadian rhythm and overall well-being.

The timing of dinner is addressed, exploring the impact of eating late on sleep and recognizing cultural variations that may influence this aspect.

Perceived work flexibility is acknowledged as a key factor, with research indicating a correlation between the flexibility of mothers' work schedules and the quality of sleep routines for their children.

This comprehensive overview underscores the multifaceted nature of sleep preparation, offering therapists valuable insights for supporting families in establishing effective sleep practices. While challenges may exist, the emphasis lies on collaborative problem-solving and education to empower families to make informed choices based on their unique circumstances. As the discussion expands to include supplements, vaccines, and specific challenges related to a child's reluctance to sleep, these topics will be explored to foster a thorough understanding of sleep-related considerations.

Sleep Participation

Stages

- Stage 1: NREM (N1)

- Relaxing muscles

- Body temperature decreases

- Eye movements slow, side to side

- Brain waves

- Easily awakened

- Stage 2: NREM (N2)

- Some vigilance

- Lack of eye movement

- Regular breathing and heart rate

- Rapid bursts of brain activity*

- Sleep spindles: turns learning into memories

- Synaptic pruning

- Stage 3: NREM (N3)

- Increased relaxation

- Decreased pulse and breathing rate

- Immune-system activation

- Tissue repair through growth hormone release

- Slow brain waves

- Neurotransmitter regeneration

- Stage 4: REM (R)

- Rapid eye movement (REM)

- Brain activity mimics that of alert and awake

- Vivid dreams

- Muscles other than the heart and lungs are paralyzed

It's crucial to understand the various stages of sleep, each characterized by distinct physiological changes. In the initial stage, known as stage one nREM (non-rapid eye movement), relaxation sets in, muscle tension decreases, overall body temperature drops, and eye movements slow and become side-to-side. Brainwaves start calming down, and individuals in this stage are easily awakened, akin to the light dozing experienced, for instance, when nodding off during a movie.

Moving to stage two nREM, vigilance persists, but eye movement diminishes. Breathing and heart rate become regular, accompanied by rapid bursts of brain activity. Notably, this stage introduces sleep spindles, crucial for converting learning into memories. The significance of stage two in the context of childhood development and learning is increasingly recognized.

Transitioning to stage three nREM, a deeper stage ensues, marked by increased relaxation. Pulse and breathing rates decrease, facilitating immune system support and tissue repair by releasing growth hormones. Slow brainwaves and neurotransmitter regeneration characterize this stage.

Stage four marks the entry into REM (rapid eye movement), a phase where brain activity mirrors that of alert wakefulness. Vivid dreams occur during this stage, often with limited recall. Notably, muscles, excluding those responsible for heart and lung functions, experience temporary paralysis during REM sleep.

Understanding these sleep stages provides insight into the intricate architecture of sleep, emphasizing the importance of each phase for overall sleep quality and its implications for memory consolidation and bodily rejuvenation.

Typical Sleep

- 3 Functional States

- NREM

- REM

- Wakefulness

- 4 stages of sleep: N1, N2, N3, R

- Ultradian Rhythm

- Alternating cycles of REM/NREM

- Stage 3 NREM (deep sleep) dominates the first 1/3 of the night

- REM sleep dominates the last third (dreaming/ absence of skeletal muscle tone)

- Development: 50m (infancy), 90-110m (school age-adult)

- Development

- 0-3m: no circadian rhythm

- 2-3m: sleepiness and alertness rhythm

- 4-12m: more nocturnal

- 1-4y: naps are common (18m decrease)

Despite being physically immobile during REM sleep, the brain remains exceptionally active and engaged in dynamic cognitive processes. The significance of REM sleep lies in its crucial role in various functions, including dream experiences. A typical sleep cycle involves alternating non-rapid eye movement (nREM) and REM stages, interspersed with brief periods of wakefulness. These stages collectively contribute to the overall sleep architecture.

The ultradian rhythm refers to the alternating cycles of REM and nREM sleep. Notably, the first third of the night is often dominated by stage three nREM, representing deep sleep. While REM sleep can predominate in the last third of the night, individual variations are common, especially among children.

Observing sleep patterns through sleep apps may reveal these trends, showcasing the dominance of different sleep stages during specific portions of the night. Infancy exhibits shorter sleep cycles, around 50 minutes, while school-age to adult sleep cycles extend to approximately 90 to 110 minutes. Variability exists within these ranges.

Developmentally, the circadian rhythm in infants is not fully established in the initial months, gradually forming alertness and sleepiness rhythms by two to three months. From four to 12 months, a more nocturnal pattern emerges. In the one to four-year age range, napping is common, but around 18 months, a normative decrease in napping may be observed. Recent research suggests the potential benefits of maintaining napping habits and challenging cultural norms around napping cessation. However, cultural practices often lag behind emerging scientific insights.

Sleep Architecture

- Total sleep time, sleep period time, and time in REM decrease from infancy to adulthood

- No difference in biological sex

- Influences anxiety in children

- A typical night of sleep (approximately 8 hours):

- First cycle: 1-2-3-2-REM

- Second cycle: 2-3-2-REM

- Third cycle: Wake briefly-1-2-3-2-REM

- Fourth cycle: 1-2-wake briefly

- Fifth cycle: 1-2-REM-2

In the context of sleep participation, it's notable that total sleep time, sleep period time, and time spent in REM (rapid eye movement) decreases from infancy to adulthood, showing a developmental progression. Importantly, these sleep parameters have no discernible difference between biological genders. Anxiety in children can be influenced by sleep patterns, particularly inadequate REM sleep. When children experience insufficient REM sleep, they may exhibit heightened anxiety or irritability, serving as a potential indicator of disrupted sleep patterns. Consistent deprivation of REM sleep over time can contribute to the development of more persistent anxious behaviors and states in children.

An average night of sleep, approximately eight hours, may consist of multiple sleep cycles characterized by stages of non-rapid eye movement (nREM) and REM sleep. The cyclical nature of sleep includes variations such as 1-2-3-2-REM or 2-3-2-REM, reflecting different stages in each cycle. These variations are observable through sleep tracking apps, providing insights into the dynamic nature of sleep cycles.

Infant Sleep Issues

- The transition from bassinet to crib

- Night Wakings

- Development

- Milestones can create disruptions

In infants, some sleep issues can happen from transitioning from the bassinet to the crib, like night wakings and milestones that create disruptions.

Toddler Sleep Issues

- Transition

- Crib to bed

- Development

- Calling out

- Climbing out

- Night fears

- Night Wakings (normal)

- 3-6 times/night

Navigating toddler sleep issues also presents unique challenges, often around developmental milestones and transitions. Key considerations include transitioning from crib to bed. This period signifies a significant change for toddlers. The newfound bed freedom can lead to challenges like calling out, climbing out, and resisting the new sleeping arrangement.

Climbing out becomes common as toddlers acquire motor skills and independence, disrupting sleep patterns and posing safety concerns. Developmental milestones in toddlerhood are marked by rapid development, and as they acquire new skills, toddlers may experiment with these abilities during the night, impacting their sleep routine.

The emergence of night fears is a natural part of toddler development. It's common for toddlers to experience fears of the dark, monsters, or other imaginative elements, leading to disrupted sleep. Night wakings are normal for toddlers, with an average of three to six times considered within the typical range. While these night wakings are expected, addressing them effectively can improve sleep habits.

Behavioral Insomnia Categories

Insomnia Category |

Description |

Therapy Intervention Options |

Inadequate sleep hygiene | Due to performance of ADLs that are inconsistent with maintenance of good quality sleep and full daytime alertness | Sleep hygiene program |

Insufficient sleep syndrome | Persistently fails to obtain sufficient nocturnal sleep required to support normally alert wakefulness | Sleep log Mindfulness Worry shell Sensory arousal approaches |

Limit-setting sleep disorder* | Inadequate enforcement of bedtimes by a caretaker, with child then stalling or refusing to go to bed at an appropriate time | Parent education/ coaching Behavioral approach Routine building Sleep hygiene |

Sleep-onset association disorder | Occurs when sleep onset is impaired by absence of a certain object or set of circumstances (person, activity, eating); unable to fall back to sleep as well | Fading of adult intervention Maintain daytime naps Transition object introduction Sleep hygiene optimization |

An inadequate sleep hygiene program entails a lack of a structured sleep preparation routine, affecting daytime alertness. The solution involves implementing a sleep hygiene program with three to four preparatory activities.

Insufficient sleep syndrome refers to a persistent lack of sufficient sleep hindering alert wakefulness. Recommended interventions include using a sleep log, mindfulness techniques, worry shells, and sensory arousal approaches. Medical assessment may be necessary.

Limit-setting sleep disorder involves blaming inadequate bedtime enforcement by caregivers for a child's stalling and refusal to go to bed. Interventions encompass parent education, coaching, behavioral approaches, routine building, and assertiveness training.

Sleep onset association disorder signifies impaired sleep onset due to the absence of a specific object or activity, leading to difficulties falling back to sleep. Recommended interventions involve gradually fading adult intervention, maintaining daytime naps, introducing transition objects, and optimizing sleep hygiene.

These categories offer insights into potential factors contributing to behavioral insomnia, allowing for targeted interventions to enhance sleep quality in children.

Sleep Concerns

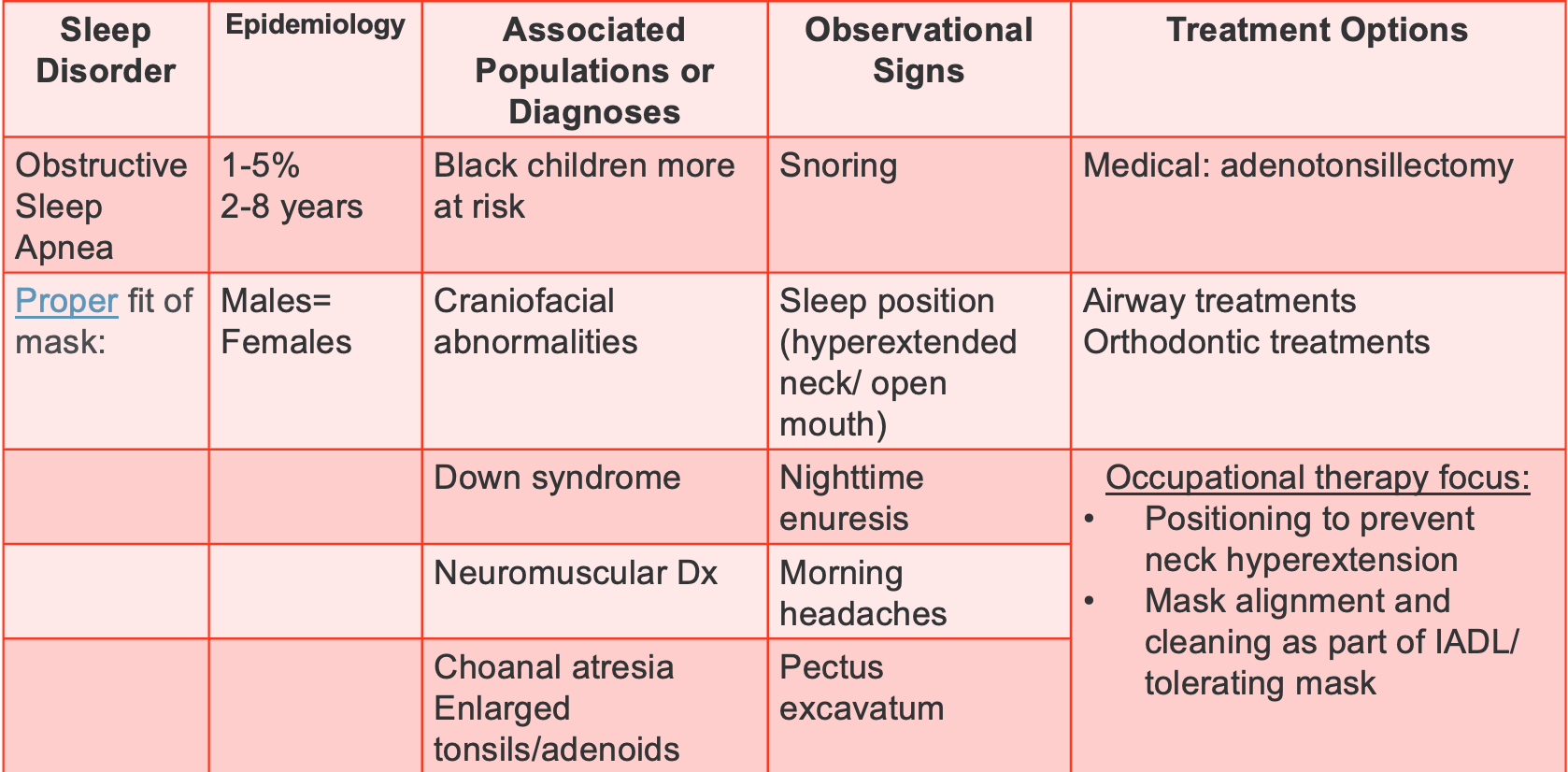

"Hit the SAAQ" can be used to address sleep concerns. I have provided a chart that will go on for a few slides. It will provide the sleep disorder, the epidemiology behind that sleep disorder, some helpful information, the population or diagnoses at risk, observational signs, and treatment options. It will help you decide if you must involve physicians and other health practitioners. Figure 5 is a chart I developed to pull this information together.

Figure 5. Chart overviewing obstructive sleep apnea.

Discussing obstructive sleep apnea, a significant concern typically observed in the age range of two to eight years. Interestingly, both males and females share an equal risk, but children of Black or African American descent face higher susceptibility. Additionally, those with cranial facial abnormalities, Down syndrome, or any neuromuscular diagnoses, along with enlarged tonsils or adenoids with choanal atresia, are more prone.

Understanding the proper fit of a sleep apnea mask is crucial for parents dealing with this issue. I've included a link for reference to aid informed decision-making. When working with children in this context, informing parents about the correct fit and maintenance of the mask becomes an essential aspect of care.

Treatment options encompass medical interventions such as adenoid and tonsil removal, common procedures in such cases. Airway and orthodontic treatments also play a role in addressing the condition. From an occupational therapy perspective, focusing on positioning to prevent neck hyperextension is vital, particularly for those with neuromuscular diagnoses or Down syndrome. Attention to mask alignment and cleaning is integrated into activities of daily living. For some children, building tolerance to the mask may be challenging, prompting the use of sensory approaches, behavioral strategies, and rewards to ease the process.

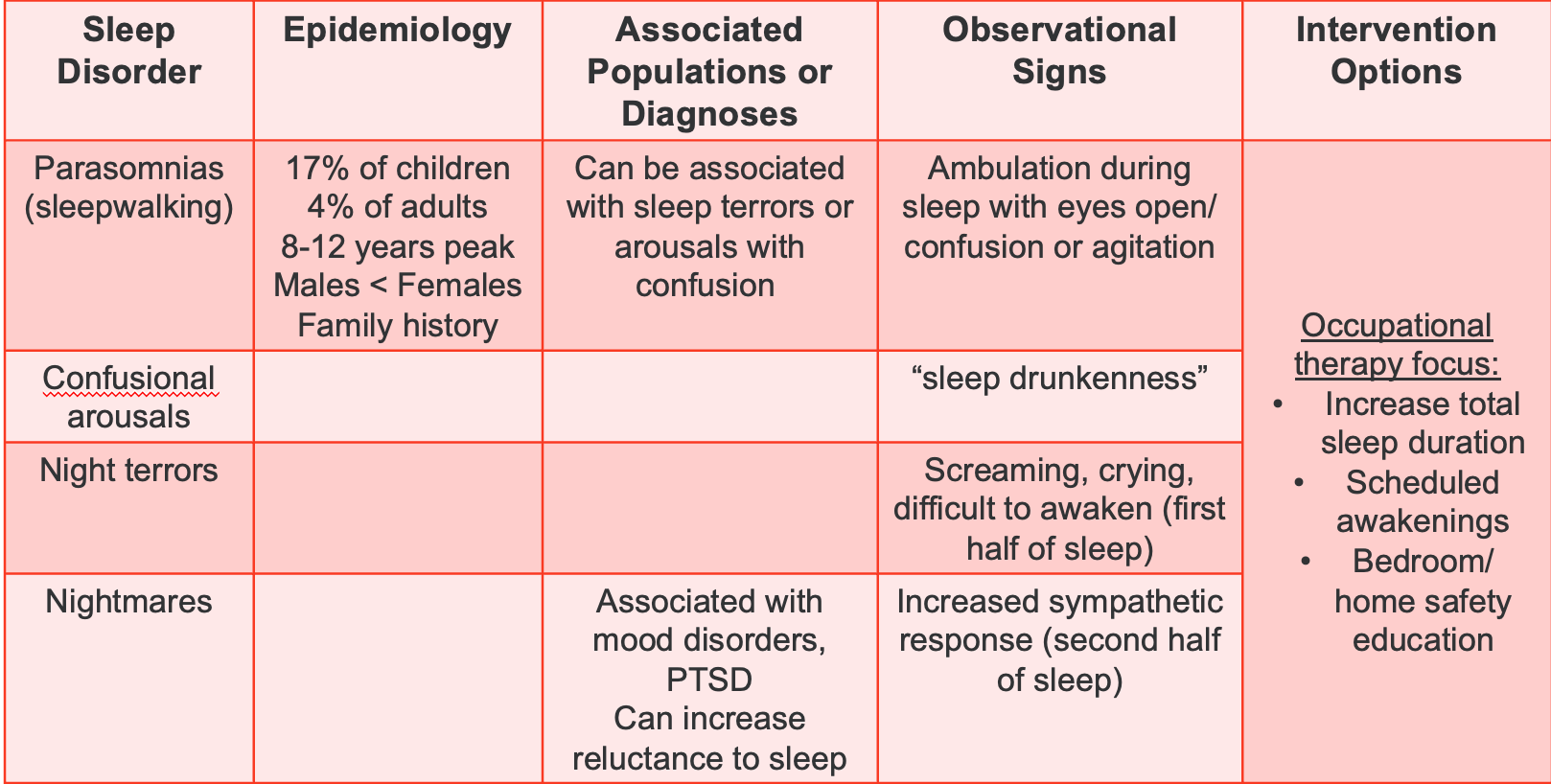

Figure 6 shows information on other sleep disorders.

Figure 6. Chart overviewing other sleep disorders like parasomnias, confusional arousal, night terrors, and nightmares.

Exploring parasomnias, particularly sleepwalking, is a concern that affects around 17% of children. The peak age for this phenomenon is eight to 12 years, with notable differences between males and females. Family history can also contribute to the likelihood of sleepwalking. Intriguingly, individuals with a history of sleepwalking often discover shared experiences among family members.

Sleepwalking can be associated with sleep terrors, typically observed around six to seven years of age, or arousals with confusion. Children engaged in sleepwalking exhibit actions while asleep, often with open eyes, and may display confusion or agitation. Interventions not only address sleepwalking but also confusional arousals, sleep drunkenness leading to sleepwalking, night terrors, and nightmares.

Night terrors, characterized by intense episodes of screaming and crying, usually occur in the first half of sleep and can be linked to mood disorders or PTSD. On the other hand, nightmares are more vivid dreams that children can recall and may be associated with an increased reluctance to sleep.

Observing sympathetic responses, such as redness of cheeks or ears, changes in breathing, fisting, or becoming noodly, can offer insights into the child's emotional state during sleep disturbances. While nightmares can be discussed by the child, night terrors are typically not remembered.

Occupational therapists can contribute to managing these conditions by increasing total sleep duration, scheduling awakenings to disrupt established sleep patterns, and educating families on bedroom and home safety measures. Safety concerns, such as children attempting to leave the house or climb out of windows while sleepwalking, may arise, necessitating specific safety precautions.

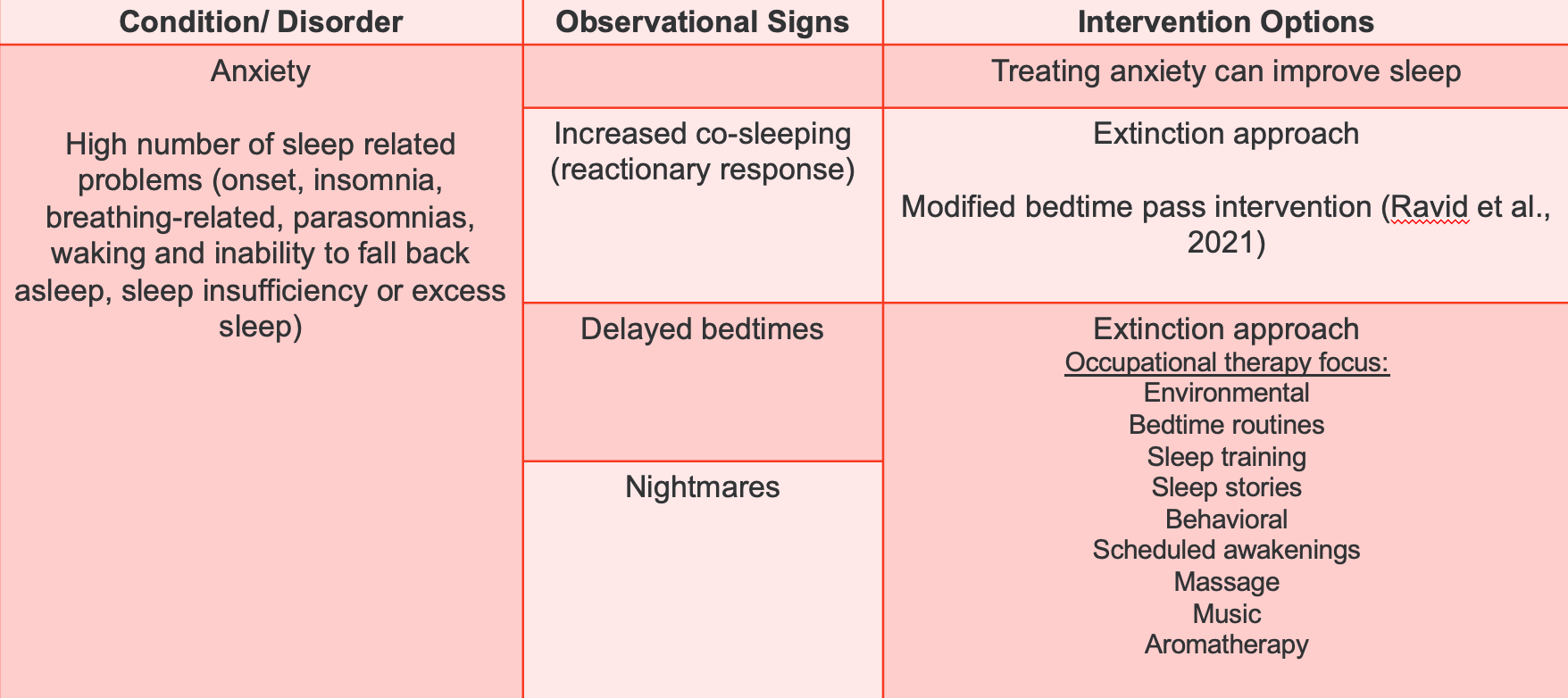

Figure 7 looks at anxiety.

Figure 7. Chart overviewing anxiety and relation to sleep.

Anxiety often accompanies various sleep-related issues, ranging from difficulties in falling asleep to parasomnias and breathing-related problems. Children with anxiety may experience insomnia, struggling to return to sleep once awakened. Sleep-related challenges associated with anxiety include both insufficient and excessive sleep, leading to behaviors like increased co-sleeping or delayed bedtimes.

Addressing anxiety directly has proven effective in improving sleep outcomes. Therapeutic interventions, such as sensory approaches and social-emotional learning strategies, can reduce anxiety and, consequently, improve sleep. The extinction approach involves gradually modifying bedtime routines or schedules to disrupt established patterns and alleviate anxiety.

Environmental modifications, alterations to bedtime routines, and incorporating sleep-related elements, such as music, apps, stories, or massage, can aid in creating a more conducive sleep environment. Behavioral approaches, including reward systems and monitoring, scheduled awakenings, and aromatherapy, offer diverse options tailored to the child's needs. While some strategies may require trial and error, a comprehensive approach targeting anxiety can significantly enhance sleep quality.

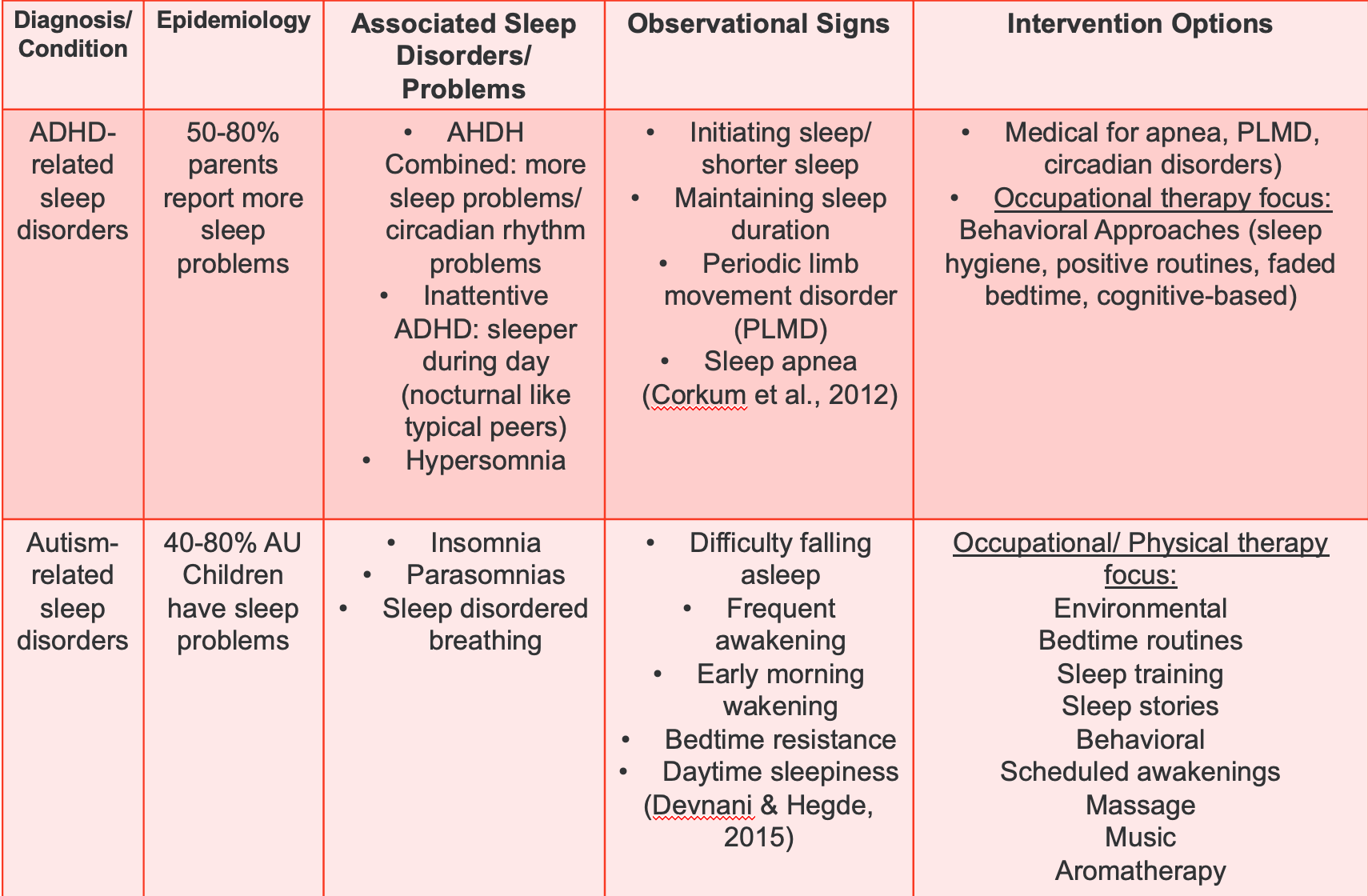

ADHD and autism-related sleep disorders are reviewed in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Chart looking at ADHD, autism, and sleep.

Children with ADHD often experience sleep-related challenges, with 50 to 80% of parents reporting sleep problems. The combined type, characterized by both hyperactivity and inattention, tends to face more sleep issues and circadian rhythm problems. Sunlight exposure in the morning can be beneficial for these children, particularly those with circadian rhythm challenges.

Observationally, children with ADHD may exhibit hypersomnia, where they fall asleep frequently and deeply. Some may also experience periodic limb movement disorder, sleep apnea, difficulty initiating sleep, shorter sleep duration, or difficulty maintaining sleep. Seeking medical attention is crucial for issues like apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, and circadian disorders.

While sunlight exposure is encouraged, caution is advised when considering melatonin supplementation, as it is a hormone with uncertain long-term effects, especially in children entering puberty. It's recommended that parents discuss melatonin use with their child's physician. Behavioral approaches are effective, including sleep hygiene, positive routines, and faded bedtime strategies. Additionally, cognitive-based interventions show promise in addressing sleep challenges in children with ADHD. Some evidence suggests that sensory input, physical activity, and play during the day can benefit those with periodic limb movement disorder.

Individuals with autism often experience sleep problems, with 40 to 80% facing challenges such as insomnia, parasomnias, and sleep-disordered breathing. The sleep-related issues in autism mirror those observed in ADHD, encompassing difficulties falling asleep, frequent nighttime awakenings, early morning awakening around 4:00 AM, as well as bedtime resistance and daytime sleepiness.

Addressing sleep concerns in individuals with autism involves employing strategies similar to those used for anxiety-related sleep problems. Environmental modifications can improve sleep outcomes, such as creating a conducive sleep environment, implementing sleep training techniques, and establishing positive bedtime routines.

When seeking medical intervention for sleep-related issues in individuals with autism, it is essential to comprehend the physician's recommendations. If a sleep study is conducted, obtaining and reviewing the sleep report becomes crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the individual's sleep patterns and potential recommendations for intervention.

Rest/Sleep Prep/Sleep Participation

Sleep Quality

- Going to bed at consistent time

- Sleeping for 9-12 hours

- Minimum delay of sleep latency

- Limited sleep disturbances

- Absence of daytime dysfunction due to sleepiness

Achieving optimal sleep quality involves several key factors. It is essential to maintain a consistent bedtime, aiming for a recommended sleep duration of nine to twelve hours, particularly for children and adolescents. Sleep quality is further enhanced by minimizing the time it takes to fall asleep, known as sleep latency, ensuring limited disruptions during sleep, and preventing daytime dysfunction caused by sleepiness.

Individuals should prioritize adequate rest, engage in effective sleep preparation activities, and actively participate in sleep-promoting behaviors to enhance sleep quality. By adhering to these principles, individuals can create an environment conducive to achieving and maintaining high-quality sleep, ultimately contributing to overall well-being and daytime functioning.

Sleep Specific Interventions

- Mindfulness exercises: Duration, architecture, promote latency

- Safety: worry shell, dream catcher, locked external doors

- Relaxation: Yoga/light stretching

- Cultural needs: Gratitude/prayers

- Caregiver bonding: Sleep duration (hygiene), architecture

- Bibliotherapy/social stories

- Caregiver presence-cuddles, safety

- Mom's perceived flexibility of work schedule

- Sleep log/charts: EBP routine building, routine, motivation

- Sleep games: Increase motivation/ buy-in

- Sleep diary: EBP monitor, routine, motivation

- Architecture: wearables without screens

- Sensory accommodation: Duration, architecture

- Weighted blankets (safety with weight %, do not use with infants)

- Comfortable/preferred clothing

- Creating a cozy sleep space

- Reduction of noise (light, sound, tactile, electronics, etc.)

- Decrease activity level

- Monitor meals (timing, content)

In the realm of sleep-specific interventions, mindfulness is a cornerstone approach supported by evidence. This multifaceted technique proves beneficial in addressing various aspects such as sleep duration, architecture, and latency. Particularly effective for children encountering challenges in falling asleep, mindfulness serves as a calming mechanism for those grappling with anxiety, ADHD, or heightened sensory processing.

Mindfulness interventions, however, necessitate consideration from a safety perspective. Precautions involve ensuring secure environments for children and implementing therapeutic aids like dream catchers. An intriguing and successful method within this framework is the "worry shell" meditation. Tailored for children dealing with ADHD, autism, or anxiety-related sleep issues, the worry shell introduces a symbolic narrative involving a shell, the ocean, and the act of unburdening worries.

Encouraging children to imagine being on a beach, sinking into the sand due to the weight of their concerns, the worry shell narrative unfolds. The child finds a shell, symbolizing their worries, and engages in a cognitive behavioral exercise by vocalizing their concerns to the shell. Subsequently, the child metaphorically throws the shell back into the ocean, alleviating their worries and fostering a sense of lightness conducive to restful sleep.

Complementary interventions extend to yoga and light stretching, focusing on yoga nidra, an evidence-based body scan mindfulness approach. Caution is advised regarding potential religious connotations, emphasizing the need for sensitivity in presentation. Additionally, incorporating gratitude prayers emerges as a mindfulness exercise, offering a family-oriented component to the bedtime routine.

Bibliotherapy, centered around social stories and reading books, supports caregiver bonding while addressing sleep duration and architectural considerations. The presence of caregivers, involving cuddling and safety reassurances, contributes to creating a secure bedtime environment. Sleep logs and charts, although perhaps dubiously named, provide an evidence-based tool to track sleep patterns, motivate children, and introduce sleep games for engagement.

A noteworthy recommendation involves the utilization of wearables without screens, offering anecdotal benefits beyond sleep tracking. The article mentioned details a mother's experience with such a wearable, highlighting unintended advantages, such as heightened parental awareness of correlations between a child's sleep and subsequent behavior.

Sensory accommodation strategies, pivotal for managing sleep duration and architecture, encompass the cautious use of weighted blankets. While effective for calming children with high arousal, their usage requires adherence to safety guidelines, especially with infants and toddlers. Attention to comfortable clothing, creating a cozy sleep space, and reducing noise contribute to an optimal sleep environment.

The nuanced progression of bedtime routines is emphasized, recognizing that the abrupt imposition of sleep expectations can trigger resistance. Acknowledging children's inherent negotiating skills, a strategic approach involving gradual transitions, choices, and behavioral rewards is advocated. The discussion discourages the Ferber method, promoting an individualized, behaviorally focused approach that considers each child's unique needs and responses.

Sleep Quality: Learning & Emotional Regulation

- Inadequate sleep: more negative, less positive emotions (Palmer & Alfano, 2017)

- Children who spend less time awake during the night in early life are associated with better performance on working memory tasks (Pisch et al., 2019)

- Sleep enhances memory consolidation from an early age (those who don’t nap have problems remembering a newly seen face) (Horvath et al., 2018)

- Sleep duration 0-4y relates to emotional regulation and other health indicators (Chaput et al., 2017)

- More Stage N2 sleep, less Stage N3 sleep, and less slow-wave sleep results in stronger improvements in executive function test (Vermeulen et al., 2018)

- Only 8.8% of U.S. children meet all 3 guidelines: sleep, physical activity, and screen time (Friel et al., 2020)

Understanding the intricate connection between sleep and various aspects of a child's development, including learning and emotional regulation, provides a compelling rationale for prioritizing sleep quality. The evidence underscores the transformative impact that adequate sleep can have on children's cognitive and emotional well-being.

Positive sleep quality is intricately linked to positive emotions, while insufficient sleep correlates with heightened negative emotions. The importance of uninterrupted sleep during the night becomes evident early in life, as children who spend less time awake during nighttime hours exhibit improved performance on working memory tasks. This insight is a persuasive incentive for families grappling with resistance due to overwhelming circumstances.

Memory consolidation, a critical cognitive process, is significantly influenced by sleep. Notably, children who forego napping may struggle to remember newly encountered faces, underlining the role of sleep in memory retention. While the absence of napping does not necessarily warrant alarm, understanding its potential impact can inform a nuanced approach tailored to the child's needs.

The duration of sleep during the formative zero to four-year age range emerges as a pivotal factor in emotional regulation and in influencing broader health indicators. This emphasizes the need to balance acknowledging the importance of sleep duration and avoiding rigid adherence to specific numerical targets.

Delving into the intricate architecture of sleep, the correlation between sleep stages and executive function is revealed. More Stage N2 sleep and less Stage N3 sleep, characterized by slow-wave sleep, lead to pronounced improvements in executive function. Although we may not directly control sleep spindle patterns, optimizing sleep duration and creating conducive sleep conditions can enhance these critical cognitive functions.

Recognizing the role of sensory input in calming arousal levels, interventions involving proprioception and deep pressure prove beneficial. Techniques such as linear rocking provide a soothing sensory environment that fosters better sleep quality. These insights align with established practices addressing sensory needs to promote relaxation and sleep.

The broader context of children's lifestyles in the United States, marked by insufficient sleep, inadequate physical activity, and excessive screen time, further underscores the urgency of prioritizing sleep hygiene. This multifaceted approach involves not only optimizing sleep duration but also mitigating external factors that can impede the quality of sleep.

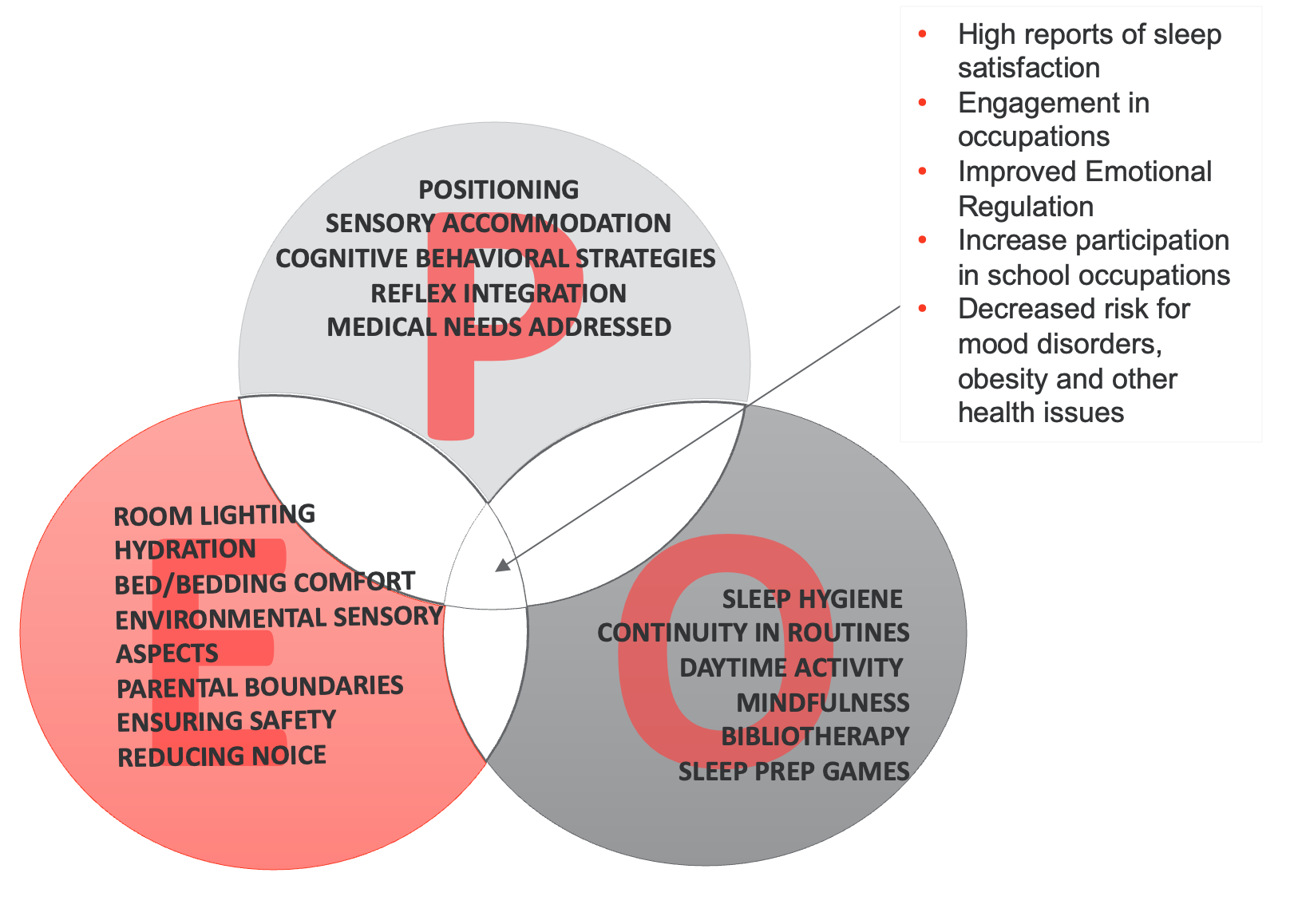

Person-Environment-Occupation Model

From a PEO perspective, these are options you can do (Figure 9).

Figure 9. PEO model with sleep treatment options (Click here to enlarge the image.)

Packet

You can go through this packet, start to get some information from the family, and then fill that out. The bottom part has what you can do from an intervention approach, right?

SAAQ | Pre-Assessment Info | Additional Interview Info | CSHQ Information |

S: Sleep timing | Bedtime?___________ Wake time?_________ Consistency?_______ Hours of sleep?_____

| Exposure to sunlight Mother’s work schedule Sleep hygiene?

|

|

A: Sleep disorder? | What type?

| How does this affect the child?

|

|

A: Architecture

| Is child cranky/ anxious next day (REM)?

| What time are electronics turned off?

|

|

Q: Quality | Do you have wearable (what is score?)

| How does child rate his/her sleep?

|

|

Case Study: Julie

- Julie is 8 months, and her mother states she “is a bad sleeper.” Her parents have another child who is 2. Julie can roll over to one side.

- Julie has a dx of Down syndrome and sleeps in her parents’ bedroom in an approved crib.

- Julie’s mother, Hannah, says that their schedule is “all over the place sometimes,” and she often falls asleep feeding Julie while feeding her sitting on the couch.

- Hannah expressed concerns about safety with SIDS, needs help promoting sleep routine, and is also indicating that her 2-year-old, K.C., is also “not the greatest sleeper” and resists going to bed.

Julie is eight months old. Her mother states she's "a bad sleeper." We probably have all heard this before. Her parents have another child who's two. Julie can roll over, so we know she can move to one side. She has Down syndrome. She sleeps in her parents' bedroom in an approved crib, so she's safe, which is great. Mom says their schedule's "all over the place" and that she often falls asleep feeding Julie while sitting on the couch. Hannah (mom) expressed concerns about SIDS safety and needs help promoting a sleep routine. She's also indicated that her two-year-old, Casey, is not the greatest sleeper and resists going to bed. What are we going to do?

Hit the SAAQ

- S: Amount of sleep (duration)

- Sleep hygiene for both

- Consistent bedtime

- Get father involved

- A: Address: Safety

- Back to Sleep

- Education on SIDS

- Tummy time

- A: Address sleep problems

- Obstructive sleep apnea??

- More at risk for behavioral sleep issues

- Low tone-need firm mattress/ positioning

- Q: Quality

- Routine is key

- Quality sleep improves behavior and learning

- Benefits entire family, lifelong patterns

We can implement the "Hit the SAAQ" approach for Julie, addressing the amount and duration of her sleep. Introducing sleep hygiene practices can empower Mom and establish a consistent bedtime routine. Involving the father, if possible, benefits overall family sleep quality.

Safety is paramount, and Mom should be educated on the back-to-sleep campaign, minimizing covers in the bed, and promoting safe sleeping positions. Emphasizing tummy time contributes to healthy sleep patterns. Considering the heightened risk for obstructive sleep apnea in Down syndrome, a physician's evaluation is crucial. Behavioral sleep issues may arise, especially with low tone, necessitating a firm mattress and specific positioning. If Julie uses a CPAP, ensuring proper mask fit and educating Mom on its use is essential.

Monitoring sleep quality over time is vital for building positive lifelong patterns. Quality sleep positively impacts behavior and learning, benefiting Julie and her two-year-old sibling. This comprehensive approach is a practical framework to guide interventions and support Mom in fostering better sleep for her children.

Case Study: Jaxson

- Jaxson is 8 and has a dx of ASD.

- He likes going to bed but has difficulty with awakenings through the night.

- He has daytime sleepiness.

- Mom reports she notices on the nights when he wakes up more, he is cranky the next day.

- Mom reports he likes games and animals and wants to join a baseball team. She is concerned he won’t make the team because of his low tone and dyspraxia. She stated he spends most of his time playing video games on the couch/bed/floor.

Examining Jaxson's sleep challenges, we find that his difficulty with nighttime awakenings leads to daytime sleepiness and crankiness. Understanding the connection between REM and nREM sleep sheds light on the potential reasons for his mood fluctuations.

Jaxson's interests in games and animals and a desire to join the baseball team offer valuable insights into potential motivators for sleep interventions. However, concerns about low tone, dyspraxia, and excessive screen time placing him at risk for obesity need addressing.

Implementing the "Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire" (CSHQ) can provide a structured assessment of Jaxson's sleep patterns, helping identify specific areas requiring intervention. This comprehensive approach considers physical and behavioral aspects, aiming to improve the quality of Jaxson's sleep and alleviate daytime challenges.

SAAQ | Pre-Assessment Info | Additional Interview Info | CSHQ Information |

S: Sleep timing | Bedtime?____8_______ Wake time?____7_____ Consistency?____Y___ Hours of sleep?____11_

| Exposure to sunlight- minimal Mother’s work schedule –works p/t home Sleep hygiene? Grooming, PJ, cuddles, story

|

-grinds teeth |

A: Sleep disorder? | What type?

| How does this affect the child?

|

|

A: Architecture

| Is child cranky/ anxious next day (REM)?

| What time are electronics turned off?

|

-tired -sometimes he watches phone during night -nightlight for bathroom |

Q: Quality | Do you have wearable (what is score?)

| How does child rate his/her sleep?

|

|

Analyzing Jaxson's sleep routine, we applaud the consistent bedtime and waking schedule, demonstrating a commendable effort by his mother. However, identifying areas for improvement is crucial for optimizing his sleep quality.

Sunlight exposure is a potential enhancement, though the effectiveness of sunlight lamps remains uncertain. Despite cost concerns, exploring this option could be beneficial. Acknowledging the flexibility of the mother's work schedule is advantageous, allowing for adjustments to accommodate Jaxson's needs.

Jaxson's sleep hygiene practices, including grooming, pajamas, cuddles, and storytime, align with positive bedtime routines. The absence of co-sleeping and pets in his bed is noteworthy. However, discovering teeth grinding and difficulty waking up raises concerns about a potential sleep disorder, necessitating collaboration with a physician.