Introduction

Imagine awakening one morning, feeling more tired than when you went to bed. Your sleep was unrefreshing. The morning’s occupations await. These include a lively young daughter to get ready for school, her lunch to make, your lunch to make, the dogs to feed, and your body to dress in preparation for another busy day as an occupational therapist. As you go about your tasks, the fatigue feels so intense that you actually feel ill with the need to lie down. You manage to reach the clinic and find appointments for 18 clients on your daily schedule. You will need to perform a number of physical activities in order to treat these people. It is impossible to keep up with the daily documentation, required reassessments, evaluations, and discharge documentation as you struggle to provide your usual standard of client care. It is necessary to stay at the clinic after hours to complete the documentation. When you arrive home that evening, dinner preparations are rushed and family time is limited. You are late going to bed. Each day this continues. A heavy black curtain of fatigue separates you from the meaningful occupations in your life. Within a few years, you prematurely retire from clinical practice, unable to perform the quality of occupational therapy that you feel is deserved by your clients. This describes an onset of chronic pathological fatigue, of the type experienced in many autoimmune and neuro-immune illnesses.

Background

Peripheral fatigue is well-known, widely experienced, and not a pathological entity (Van Heest, Mogush, & Mathiowetz, 2017). This type of fatigue may be experienced after physical or mental excessive exertion, and is a physiological response (Krajewska-Włodarczyk, Owczarczyk-Saczonek & Placek, 2017). The usual reaction is a cessation or decrease in the exertion, often with a period of rest. Rest, either short-term or after sleep, is restorative. Chronic pathological fatigue, sometimes referred to as central fatigue, is often present in the absence of significant exertion, may have specific triggers such as sun exposure, and is not relieved by rest or sleep (Van Heest et al., 2017). Sustained fatigue can interfere with thought processes as well as daily occupations (Treharne et al., 2008; Van Heest et al., 2017).

Prevalence

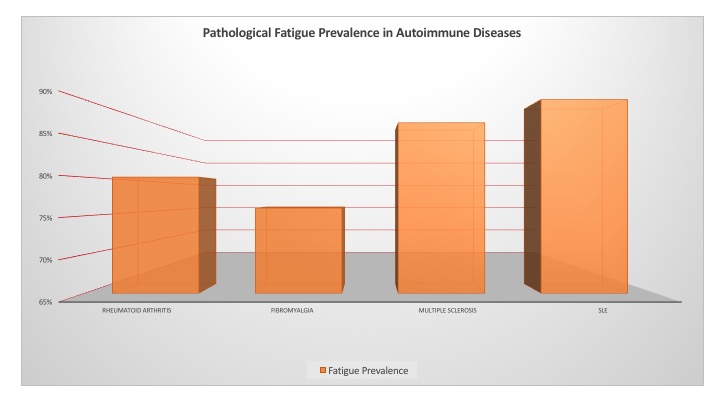

The prevalence of fatigue in autoimmune and neuro-immune disorders is high (see Figure 1). Over 80% of those with rheumatoid arthritis report chronic fatigue symptoms (Treharne et al., 2008). Chronic fatigue and unrefreshing sleep are cardinal symptoms of fibromyalgia. At least 76% of patients with fibromyalgia experience these symptoms (Vincent et al., 2013). Similarly, up to 87% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are affected by pathological fatigue that significantly reduces their occupational performance (Ward & Robinson, 2008). Individuals diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have stated that fatigue is the symptom that has the most negative effect on their quality of life and occupational engagement. Chronic fatigue is experienced by up to 90% of these patients (O'Riordan, Doran & Connolly, 2017). The prevalence of pathological fatigue that profoundly decreases a patient’s ability to function in daily occupations is similar in conditions such as primary Sjögren’s syndrome (Hackett, Newton, & Ng, 2012), psoriatic arthritis (Krajewska-Włodarczyk et al., 2017), autoimmune thyroid diseases (Jovanovic, 2017), and chronic fatigue syndrome (Nijs, 2009). Many additional autoimmune and neuro-immune chronic disorders also demonstrate symptoms of central, chronic fatigue.

Figure 1. Pathological fatigue prevalence as reported in selected widely researched autoimmune diseases. Image by author. (enlarged PDF version)

Pathogenesis

Until recently, it was thought that fatigue begins in the skeletal muscles, which are unable to perform at their continued intensity, and engender recognition of fatigue with decision-making to cease or slow the activity (Roerink, van der Schaaf, Dinarello, Knoop, & van der Meer, 2017). Current theory maintains that the central nervous system is the regulator of fatigue perception and ultimately decision-making to continue or desist in activity. Cytokines are signaling molecules which mediate and regulate immune system actions, inflammation and hematopoiesis. More specific names identify cytokines based upon the jobs that they perform. It is now thought that proinflammatory cytokines, specifically interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), play a prominent role in the perception of fatigue and the severity of fatigue (Krajewska-Włodarczyk et al., 2017).

Interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 beta engender an inflammatory reaction when bound to the type 1 IL-1 (IL-1R1) receptor. This reaction includes a complex signaling cascade that ultimately produces a number of biological events, including activation of the acquired immune system as well as the initiation of fever and slow-wave sleep (Roerink et al., 2017). These cytokines are produced peripherally, but are able to bypass the blood-brain barrier in several ways to create central fatigue effects, such as increased perception of fatigue and depressed mood as well as reduced participation in physical activity and social interactions (Roerink et al., 2017).

Levels of specific cytokines may have correlations with fatigue that vary among pathologies. For example, Lampa et al. (2014) found a positive correlation between elevated levels of IL-1β and fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Harboe et al. (2009) reported a positive correlation with elevated IL-1α and fatigue in patients with Sjögrens syndrome. Studies measuring levels of interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) have produced inconsistent results. This has resulted in a disparity in identification of CFS as a neuro-immune illness (Morris, Berk, Galecki & Maes, 2014) versus categorization as a non-inflammatory disease (Roerink et al., 2017).

Barriers to Diagnosis and Treatment

Fatigue is a symptom rather than a sign. A person’s level of fatigue is whatever he or she says it is. Because of this, pathological fatigue is difficult to assess objectively (Krajewska-Włodarczyk et al., 2017). Fewer medications are well-known for treatment of fatigue versus medications for pain or for depression. Patients may not request to be seen by the healthcare provider for “only fatigue” as opposed to pain (Vincent et al., 2013). Patients may feel that pathological fatigue is an expected part of the autoimmune or neuro-immune condition and impossible to avoid (Sandıkçı & Özbalkan, 2015). Fatigue may be erroneously equated with or thought to be a part of depression. The healthcare provider’s logic may believe that if the depression is treated, then the fatigue should be resolved. Yet, this is not the case with pathological fatigue.

Individually perceived levels of central fatigue are affected by specific factors such as poor sleep, advanced age, harsh environment, demanding employment, and lack of social support (Krajewska-Włodarczyk et al., 2017). The medical provider may tell the patient that fatigue is “natural” given the person’s advanced age, or lengthy hours on the job. When a patient is attempting to continue at a previous level of activity, he or she may be told by the healthcare provider, “You’re just trying to do too much!” Even if the activity level is high, such as maintaining two employments, the patient is attempting to report a change in fatigue behavior that differs from a normal physiological response. The statement of the provider may deprecate the validity of the patient’s complaint, neatly placing the blame on the patient rather than offering concern and assistance. It is not understood that the patient is not reporting “natural” fatigue, which will be improved when there is adequate rest. Central fatigue is increased with the above factors, but it is also present with none of these causations.

Finally, the healthcare provider may not have knowledge of non-pharmacological treatments for fatigue, and feel at a loss to address it because of this (Vincent et al., 2013). Or, the provider may not be a specialist such as would be required for prescription and management of some of the newer pharmacological treatments, which may include chemotactic medications. The role of an occupational therapist in treating a patient for chronic, pathological fatigue is not well-known or well-validated in the scholarly literature, although it is well-supported as being within the scope of practice of occupational therapy.

Role of Occupational Therapy

Scope of Occupational Therapy Practice

Occupational therapists utilize patient education in a number of forms to address the functional needs of their patients who experience pathological fatigue. Patient education is recognized and supported as treatment within the scope of occupational therapy practice, and is defined in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process (3rd ed.; American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2014) as the “imparting of knowledge and information about occupation, health, well-being, and participation that enables the client to acquire helpful behaviors, habits, and routines that may or may not require application at the time of the intervention session” (p. S30). Occupational therapists are able to view and treat the person as an individual, with specific client-centered and meaningful goals. Attaining these goals restores balance and satisfaction with occupational performance, which increases the perception of wellbeing (Hackett et al., 2012).

Treatment by physical therapists of patients experiencing central fatigue has traditionally featured a focus of exercise and increased activity over time (Veenhuizen et al., 2015). While occupational therapy for this condition may include physical exercises and activities, a more predominant treatment consists of delivery of education on energy conservation, pacing, rest–activity balance, achieving and maintaining a favorable diet, lifestyle moderation, stress management, time management, and sleep hygiene. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a necessary adjunct to these educational programs, as it addresses motivations and emotions that drive behaviors (Sandıkçı & Özbalkan, 2015). A patient may be provided with education; however, if a behavioral change is not made, the education is ineffective.

Fatigue Effects on Occupational Performance

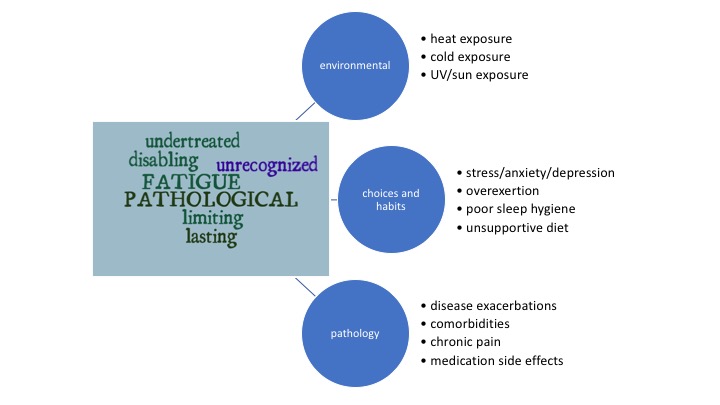

Although chronic pathological fatigue is not a cause of chronic pain, they often coexist in autoimmune and neuro-immune diseases, and each may affect the perceived severity of the other. Chronic central fatigue is also correlated with the presence of decreased activity and exercise capacity, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and progression of these conditions over time (Sandıkçı & Özbalkan, 2015). Fatigue can be a vicious cycle of decreased activity leading to decreased strength and lowered metabolism, which are perceived by the patient as increased fatigue. The triggers and causes of pathological fatigue are more complex than those of physiological fatigue, and have a more lasting effect (see Figure 2). Disease exacerbations, comorbidities, stress and anxiety, depression, poor/unrefreshing sleep hygiene, pain, heat exposure, UV/sun exposure, medication side effects, and overexertion all have central fatigue consequences (Sandıkçı & Özbalkan, 2015).

Figure 2. Triggers and causes of pathological fatigue. Image by author. (View enlarged PDF)

Pathological fatigue can have devastating effects upon a person’s performance of daily occupations. Gainful employment may be prioritized in energy expenditure due to financial necessity, to the detriment of personal appearance, personal fitness, childcare, sexual activity, homecare, social interactions, and leisure pursuits. It can reduce the physical performance ability, even given unlimited time, of previously enjoyed occupations such as gardening, cooking, dancing, exercising, performing martial arts, and other physically taxing pursuits. Chronic fatigue can cause work disability and unemployment (Sandıkçı & Özbalkan, 2015). Fatigue may be viewed by family members, friends, co-workers, and medical providers as an expression of weakness and lack of motivation. The patient may hesitate to admit the level of fatigue experienced, due to fear of stigma (Krajewska-Włodarczyk et al., 2017). The effect of chronic fatigue on occupational performance may itself present a barrier to recognition and treatment.

Occupational Therapy Assessment for Fatigue

Assessment tools for measuring fatigue as well as assessing treatment response are necessary to determine a starting point and plan of care for the patient. They are also necessary to provide progress information and treatment outcomes in regard to pathological fatigue and its effects on daily occupational performance. Both general and specific assessments are available.

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) is used as an outcomes measure for treatment of central fatigue in patients with pathologies including multiple sclerosis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and many other autoimmune and neuro-immune disorders (Nijs et al., 2009; Ward et al., 2008). The COPM uses a semi-structured interview that can be administered via computer, tablet, or smartphone with a web-based application, or by paper and pen with the standard form. It is available for purchase by individual or business from the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists’ website. The COPM is completely client-centered, focusing on the client’s perception of the importance of each occupation as well as his or her ability to perform it. Occupations assessed cover three domains: self-care, productivity, and leisure time. This measure is unique in that two subscale scores indicate not only the ability of the person to perform an activity, but also his or her satisfaction with the level of that ability. Psychometric properties of the COPM are well-established (Nijs et al., 2009).

The Short Form 36-item scale (SF-36) was developed by RAND as a part of the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS). It contains a set of general, comprehensible quality-of-life measures that measure functional status and well-being (Nijs et al., 2009). Out of 36 total questions, four specifically reflect levels of fatigue. The scale is listed as a public document, free to use, and is available at the RAND Health website. According to Nijs et al., 2009, the SF-36 is the most frequently used measure of functional status in chronic fatigue syndrome research, and has reliability and validity which generalize across many patient populations (Krajewska-Włodarczyk et al., 2017; Sandıkçı & Özbalkan, 2015).

The Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF) was originally developed for use with patients who have rheumatoid arthritis (Belza, Henke, Yelin, Epstein & Gilliss, 1993); however, it is now generalized for use with many patient populations who experience pathological fatigue (Krajewska-Włodarczyk et al., 2017; Sandıkçı & Özbalkan, 2015). The MAF consists of a 16-item scale that measures fatigue in terms of degree and severity, distress that it causes, timing of fatigue, and its effect on a number of activities of daily living (Belza et al., 1993). This assessment is available to use free of charge if its intended use is in individual clinical practice, and may be downloaded from the ePROVIDETM website.

The Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) was originally developed to measure central fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis or systemic lupus erythematosus (Krupp, LaRocca, Muir-Nash, & Steinberg, 1989). The brief scale consists of nine questions, with responses graded on a seven-point Likert scale. The highest score indicates strong agreement. Severe fatigue is indicated with scores or four or more (Krajewska-Włodarczyk et al., 2017; O'Riordan, 2017; Vanage, Gilbertson & Mathiowetz, 2003). The FSS is free to use; it was published in the original article (Krupp et al., 1989) in Table 2 on page 1122. Extensive psychometric information is available, with references to specific diagnoses (Neuberger, 2003).

Additional measures, scales, and assessments include:

- Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue scale (FACIT-F) (Krajewska-Włodarczyk et al., 2017; Sandıkçı & Özbalkan, 2015)

- Profile of Mood States, Ordinal Scales, Visual Analog Scales (Sandıkçı & Özbalkan, 2015).

- The Fatigue Impact Scale (Vanage, Gilbertson & Mathiowetz, 2003)

- The Chronic Fatigue Syndrome-Activities and Participation Questionnaire (CFS-APQ), CFS Symptom List, and Checklist Individual Strength (CIS) (Nijs et al., 2009)

- The Energy Conservation Strategies Survey (ECSS), Self-Efficacy for Performing Energy Conservation Strategies Assessment (SEPECSA), Frenchay Activities Index, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Lupus Quality of Life Questionnaire (LupusQoL), the Health Education Impact Questionnaire (HEIQ) (O'Riordan, 2017)