Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Feeding Development: What Is Typical? presented by Rhonda Mattingly Williams

EdD, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- list the 3-step hierarchy of functions important to human beings in relation to feeding.

- list 3 ways developmental readiness influences feeding progression.

- recognize 3 ways in which relationships impact feeding development.

Introduction

Good afternoon, everyone. Let's get started with typical feeding development.

Comprehensive Approach: Feeding Development

- Feeding is related to developmental readiness.

- Multisensorial, multifactorial, multidimensional processes

- Basic milestone timeline but based on the alignment of all systems

Feeding development is comprehensive and related to developmental readiness. Some people say a child will do something at six months and another at eight months. For example, we typically see kids begin to sit independently at eight months, but developmental readiness coincides more with gross and fine motor development than with a specific age.

We also know that feeding development is multisensorial, multifactorial, and multi-dimensional. A basic feeding milestone timeline based on the alignment of all systems looks at if a child can breathe, has appropriate heart function, has gross and fine motor skills, and things like that.

The Senses and Feeding

- Sight

- Sounds

- Smell

- Touch

- Sounds

- Vestibular

- Proprioception

- Interoception

As I am talking to a group of OTs, I am not going to go super deep into the senses. I will say to think about the last time you had a meal. You see, hear, smell, touch, and taste the food. You also sense if the food is hot or cold. For the vestibular sense, you need balance and movement against gravity when eating. You also need the proprioceptive sense to know where your body is and in cooperation with other parts of your body. All of these things come into play when we are eating. Additionally, when we develop feeding skills, we need to be aware of our internal states and visceral organs, known as interoception.

In typical feeding development, we eat when we are hungry and stop when we are not hungry anymore. This typical development does not happen for every single person.

Hierarchy of Feeding

- Breathing

- Postural Support

- Eating

There is a must-know hierarchy of feeding. I have heard pediatricians tell families, "Your child will eat when he or she is hungry." This is not true. In terms of typical feeding development and human functioning, we breathe first. Next, we need adequate postural support to keep ourselves upright. Last, we eat. If an individual cannot breathe or does not have adequate postural support, eating will not occur.

Environmental Factors

- What is available to a child/family?

- What sources of nutrition are affordable?

- What is a child’s experience with tastes?

- What is a child’s health status?

- What is the status of a child’s hunger?

- What social norms dominate a child’s life?

- What nutritional needs does the child have?

Environmental factors have a role in feeding development. Environmental factors include what is available to a child or a family, affordable sources of nutrition, and the child's experience with taste. We know now that a fetus can taste things within the amniotic fluid based on the mother's diet. Additionally, breast milk has an odor and taste. These factors are going to impact feeding development.

Additionally, we want to look at the child's health status. Is the child well enough to be able to eat and drink? We also need to assess the child's hunger. In atypical feeding development, children may have tubes or alternate sources of nutrition that are typically delivered on a schedule. For instance, we may feed them every three or four hours, whether they are hungry or not. In terms of normal, typical feeding development, knowing about the status of a child's hunger has much to do with how that develops.

We also need to investigate social norms. Typical feeding development at my house might look a little different at your house. Different foods are offered depending on the child's culture. And some cultures do not use utensils. There are many ways "typical feeding" looks, so it is imperative to be aware of what each child is going to have and why they are in that presentation.

Lastly, what nutritional needs does the child have? This is also going to impact feeding development.

Relationships and Feeding

- Feeding is based on observation, experience, and interaction.

- The reciprocal process between the child and caregiver

- The feeding relationship is dependent on an infant’s overall development.

- The feeding relationship is supportive to an infant’s overall development.

Relationships in feeding are absolutely critical. Feeding is based on observation, experience, and interaction. The next time you eat dinner with someone, think about how you observe what they are doing. You look, hear, and see what they are doing. As a child develops feeding skills, they also use these senses and hopefully interact with the people in their environment around food. It is a reciprocal process, and we are going to get into that a little more deeply later.

The feeding relationship is largely dependent on an infant's overall development. If an infant is not yet able to sit up independently, then the feeding relationship is going to be where the caregiver has the infant positioned to provide adequate support. In contrast, later on, when this infant can sit up independently, this relationship may change a bit. At this point, the infant can potentially self-feed, so it is going to change over time.

The feeding relationship is supportive of an infant's overall development. Suppose the family members are encouraging the child to explore, be independent, and learn things like self-feeding. In that case, that is going to enhance overall development across the board because of such a nurturing relationship and environment.

Best-Case Scenario

- Association of hunger to “time to eat”

- Communication of hunger is expressed.

- Caregiver recognizes and responds.

- “All done” is communicated.

- Caregiver responds with cessation of feeding.

The best-case scenario is that the child says, "I am hungry, and it is time to eat." An infant's cry tells the caregiver they are hungry, and the caregiver recognizes that and responds. Even more important is the cue that the infant is all done is communicated by turning their head. This is then responded to with the cessation of feeding. This goes back to the concept of interoception: "I am full, so I should be able to stop eating."

Caregiver-Child Relationship: Typical Feeding Development

- Division of responsibility (Satter)

- Infants

- The parent is responsible for what the infant consumes

- The infant is responsible for how much (and everything else)

- Infant transitioning to family food

- The parent is responsible for what (become responsible for when/where)

- The infant is responsible for how much and whether

- Toddlers-through-adolescents

- The parent is responsible for what, when, and where

- The child is responsible for how much and whether

Ellyn Satter is a famous dietician with books and classes and has been very important to our fields. She talks about a division of responsibility. In terms of infancy, parents are responsible for what the infant consumes, like breast milk, formula, and that thing. The infant is responsible for how much they take in. When the infant begins to transition to family food, the parent is still responsible for what, but also begins to have responsibility for when and where. They may say, "We are close to lunchtime or dinnertime, so let's wait a little bit," or "Let's eat at the table or in a high chair." The infant is still responsible for whether they eat and how much they eat.

The third tier of this is toddlers through adolescents. Again, parents are responsible for what, when, and where these folks eat, but the child is responsible for how much and whether they take in any of it. As a child becomes an adolescent, they can choose their own food. In my opinion, we do not push children to eat more than they want.

Typical Feeding Environment

- Baby/child present during family meals

- Baby/child plays with water/food/utensils/cups/dishes

- Baby/child observes family preparing food/eating food/enjoying food

In a typical feeding development, the baby or child is present during family meals. The child may play with water, food, utensils, cups, et cetera. In the kitchen, the child observes the family either preparing, eating, or enjoying food. In addition, the child may go to the grocery store, grandpa's garden, or a container garden if in the city. Children are exposed to food their whole lives in a typical feeding environment

Neurophysiological Development

- Homeostasis

- 1-3 months

- State regulation

- Parent provides a safe and comfortable environment

- Neurophysiologic stability

- Reflex feeding transitions to self-regulation of hunger

- Attachment

- 2-6 months

- ”Falling in love”

- Affective engagement and interaction

- Infant’s emotional/physical needs reinforced

- Individuation

- 6-36 months

- Separation and differentiation

- Behavioral organization and control

- The parent supports autonomy and provides daily structure

We also have to think about neurophysiological development and how all this plays into feeding. We are all familiar with homeostasis, attachment, and individuation. Homeostasis is seen in the first three months of life when we start to see some state regulation. The baby can stay awake a little longer and sleep a little less. The parent's role is to provide a safe and comfortable environment so that the infant has neurophysiological stability. Their heart rate and breathing are working well, and they are still very reflexive during this period.

Next, a period of attachment emerges at two to six months: the falling-in-love stage. There is a lot of engagement, interaction, and eye gaze between family members and infants. The infant's emotional and physical needs are reinforced by people responding to them.

Finally, if homeostasis and attachment have worked well, we hit a period of individuation, which is about six to 36 months. Once the infant's needs have been met, they feel they can branch out. They begin to exert some control and separate from what everybody else is doing. The parent will continue to provide them with parameters and support so the child grows in a safe and connected environment.

- Homeostasis

- Feeding Related Cues-Arousal, crying, rooting, sucking

- Hunger-satiation patterns emerge

- Positive feeding interaction promotes a future positive experience

- Attachment

- Reciprocity between child and caregiver

- Feeding Related Cues-Anticipation, social pauses/satiety pauses, preference for feeder, attention seeking

- Individuation

- The age of the individual

- Exploratory play, self-feeding emerges, speech and language development, follows simple directions, responds to ”no”

With homeostasis, we start to see feeding-related cues like arousal, crying, rooting, and sucking. Hunger and satiation patterns emerge, as well as positive feeding interaction.

A positive feeding interaction between caregiver and infant leads to attachment and reciprocity between child and caregiver. For example, if the mom is breastfeeding and the baby pauses for a second, that is honored. This reciprocity creates a further bond between the baby and the mother. If they are bottle feeding and pause, this is also honored.

If all of this goes well, the child has individuation. The child has developed homeostasis and attachment, enabling them to explore things like self-feeding. They also start to use speech and language. Now. when food is brought out to them and their experiences have been positive, they may touch and play with it or put it in their mouth and take it out again.

It is very critical that these stages happen so that the child becomes comfortable with eating.

Temperament Theory

- Categories of personality styles that persist through life

- Personality styles based on activity, adaptability, intensity, mood, persistence, distractibility, regularity, responsivity, approach/withdraw

- Relates to how individuals manage in relation to novel situations

(Thomas et al., 1970)

Along this line of homeostasis, attachment, and things like that, we must also consider the child's temperament. Temperament theory talks about categories of personality styles that persist throughout life. Personality styles are based on activity, how adaptable you are, intensity, mood, et cetera. It relates to how individuals manage novel situations. I do not know how many of you have read Marsha Dunn Klein's work, but I remember something she said that was absolutely brilliant. She said if you sit down to a meal, the food presentation changes every time you take a bite. It is longer the same shape, things may start to run out of it, or it mixes with the other foods. My point in saying this is eating and feeding are very novel due to the ever-changing aspects of food.

Temperament Categories

- Easy

- Approach to novelty:

- Positive mood

- Adaptable

- Regular

- Active

- Low intensity

- Approach to novelty:

- Slow to Warm

- Approach to novelty:

- Withdraws

- Low mood

- Low activity

- Moderate to low intensity

- Cautious

- Approach to novelty:

- Difficult

- Approach to novelty:

- Withdraws

- Low adaptability

- High intensity

- Low regularity

- Negative mood

- Approach to novelty:

The temperament categories include easy, slow to warm, and difficult. As you can imagine, if a child has an easy temperament and is adaptable, they accept novel items. Their activity is good, and their intensity is lower. In contrast, those with a slow-to-warm temperament may withdraw or be cautious around novel things. Those with a difficult temperament do not do well in novel situations. They may have a high-intensity response, withdraw, or have a negative mood. We have to keep all these characteristics in mind with feeding development.

Quick Anatomy Refresher: Infants and Children

Before we move into the stages of traditional feeding development, let's do a quick anatomy refresher.

- Oral cavity

- Pharynx

- Nasopharynx

- Oropharynx

- Hypopharynx

- Larynx

Oral Cavity

- Lips

- Mandible

- Maxilla

- The floor of the mouth

- Cheeks

- Tongue

- Hard palate

- Soft palate

- Anterior faucial arches

- Posterior faucial arches

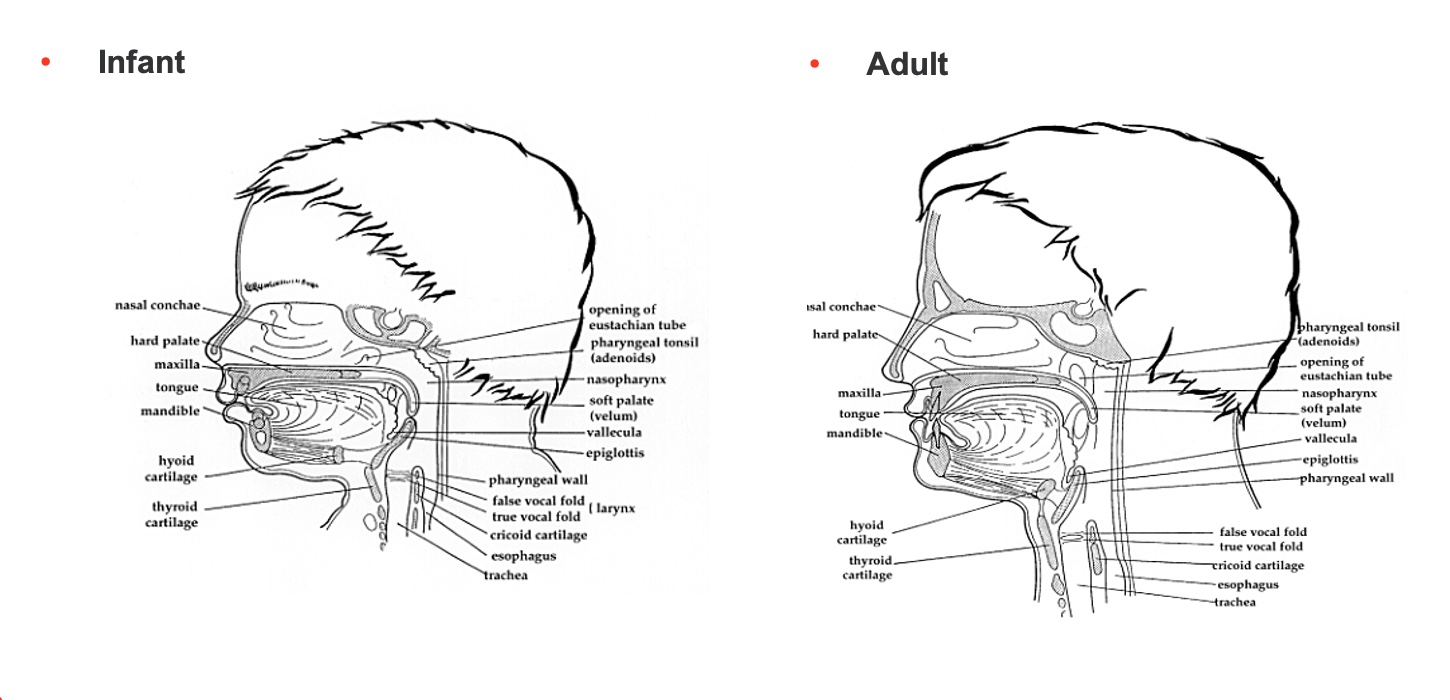

Before we move ahead, we have to understand the differences in the anatomy of an infant and an adult.

Oral Cavity Anatomical Differences: Infant vs. Adult

- Infant

- Potential Oral Cavity

- Tongue fills mouth

- The tongue rests more anteriorly

- Sucking pads (up to 4-6 months)

- Relatively smaller mandible

- Obligatory nose breathers

- Adult

- Potential Oral Cavity

- Tongue fills mouth

- The tongue rests more anteriorly

- Sucking pads (up to 4-6 months)

- Relatively smaller mandible

- Obligatory nose breathers

An infant has only a potential oral cavity, as the tongue fills the entire mouth. The tongue rests more anteriorly because the smaller mandible is moved back. They have sucking pads for up to about four to six months to help with stability and fill that space. As such, they are obligatory nose breathers, and believe it or not, these are all very good things.

Adults have true oral cavities, and our tongue does not fill the mouth. An adult's mouth has the tongue resting slightly farther back than an infant's, does not have sucking pads, and the mandible and jaw are more proportionate to the rest.

"A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words"

Figure 1 is an image by Suzanne Evans Morris, who gave me permission to use it.

Figure 1. A drawing of the oral cavities of an infant and adult. Click here to enlarge the image.

Let's start with the adult. There is an oral cavity, nasopharynx, and oropharynx. The oropharynx comes out of the oral cavity back to the pharyngeal wall. Next is the hypopharynx. The adult has these different levels. Because everything is connected, the infant has a nasopharynx, not a real oropharynx. It is not elongated yet, and the hypopharynx is squished. Again, that is not bad because the epiglottis is touching the soft palette, and everything else is very high in their pharynx.

What is going to happen around four months of age is the mandible, or jaw, is going to move forward and down, and the pharynx, or the pharyngeal space, is going to elongate vertically. The larynx and the hyoid bone, which you cannot see until after nine months, are going to come down as well, so they can be used as part of the swallowing process.

You do not have to memorize or know any of this, but I want you to know that 30 muscles and cranial nerves are involved in swallowing. The last thing I would say about this is that the anatomy is so squeezed in the infant, it makes swallowing safer. In contrast, there is a risk of food going into the airway. Until about four months of age, when all of this growth and elongation happen, the cavity is tighter and less open.

Esophagus

- Muscular tube lined with mucosa

- Cricopharyngeus (upper esophageal sphincter) (UES)

- Gastroesophageal sphincter (lower esophageal sphincter)

The esophagus is a muscular tube lined with mucosa with a couple of sphincters There is a cricopharyngeus, which is an upper esophageal sphincter. It stays closed unless swallowing activates it to open so the food can pass through. The gastroesophageal sphincter or lower esophageal sphincter also stays closed, but once we swallow, that food goes through that upper esophageal sphincter, through the esophagus, and down through the lower esophageal sphincter into the stomach. This lower sphincter then closes to keep the food from coming back up.

Again, we are talking about typical feeding development, but if any of you see children with feeding problems and reflux, this may give you a visual of what is not working for the child. This is because something either did not make it all the way through the esophagus and tried to come back up, or it made it through the esophagus, but the lower esophageal sphincter did not stay closed. This can be a real problem for people for lots of reasons.

Typical Esophageal Function

- Consists of an automatic peristaltic wave that carries bolus to the stomach

- Skeletal muscles in the cervical esophagus propel food faster than the thoracic esophagus' smooth muscles.

- The primary wave goes from UES to LES in one contraction.

- The esophageal phase occurs after each separate pharyngeal phase when there is a definite time delay between swallows.

The esophagus has a peristaltic wave, which carries the bolus or the food to the stomach. The skeletal muscles in the cervical esophagus propel that food more quickly than the smooth muscles in the thoracic esophagus. The primary wave, or first wave, goes from the upper esophageal to the lower and happens in one contraction after the swallow.

The esophageal phase occurs after each separate pharyngeal phase, and there is a time delay. There is also secondary peristalsis, as the primary wave goes through. If something has not come all the way through the esophagus and it feels this distension, the lower esophageal sphincter will open again to push the remaining bolus through to get it into the stomach and out of the esophagus.

Typical Gastrointestinal Function

- A typical pattern of gastric motility and emptying is the end result of functional and complex interactions

- Food volume, viscosity, and separate food content impact gastric function

- Acid clearance in the distal esophagus

We all have our own gastric motility and emptying. I may have a different gradient pressure in my body than you, but we all have optimal motility for us unless something happens to disrupt that. That said, food volume, viscosity, texture, and content can all impact gastric function. Some foods may move through more quickly.

Breast milk tends to have enzymes in it that are processed a little faster than a formula. This can alter how our system is functioning, but it should not disrupt it. There may be food that does not move through as well for me or you, so maybe we stop eating that.

There is also acid clearance in the distal esophagus to make sure that everything is out, and there is no irritation, as part of typical development.

Reflexes, Phases, & Norms: How It All Comes Together

We are now going to talk about reflexes, phases, and norms, and this all fits together.

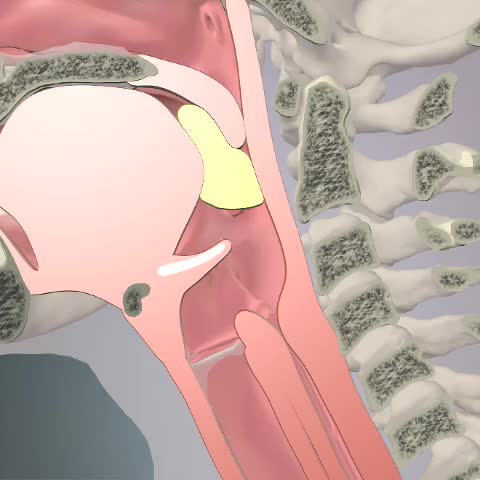

Phases of Swallowing

- Oral Preparatory Phase-Preparing food/liquid in the oral cavity to form a bolus

- Oral Transit Phase-Propelling bolus through oral cavity to posterior

- Pharyngeal Phase-Initiating the swallow, bolus moves through the pharynx

- Esophageal Phase-Moving bolus through the esophagus

These are the phases of swallowing, and you may see them written differently. Some people will say there are three phases, and others will say four, and they will name them something different. There are not many ways to talk about it, but there are a few variations. I am going to talk to you about the oral prep phase, oral transit phase, pharyngeal phase, and esophageal phase, as they are part of atypical and typical feeding and swallowing.

We are going to talk about what is typical. The oral preparatory phase prepares the food and liquid in the oral cavity to form a bolus. If I take a bite of a candy bar, I use my tongue to move it around, and masticate and chew it. After I have a nice cohesive bolus, I propel it in the oral transit phase. We are going to watch a video in a second. We propel it through the oral cavity to the posterior portion. At this point, it is going to go into the pharyngeal phase. As it enters the pharynx, the swallow is initiated and moves through the pharynx. Hopefully, with typical function, it then goes into the esophagus, where it moves through to the stomach for the whole gastric process.

Swallowing Video

This is the oral prep phase and then oral transit. The bolus is pushed back, the epiglottis drops down, and it goes into the esophagus. I am going to show you that one more time as I want to point something out. As the epiglottis drops, the arytenoid cartilage will abduct and move up a bit. Then, the false and true vocal cords close off so that everything is kept out of the airway. There are some 30 muscles and cranial nerves involved in the swallow. This helps us to appreciate the fact that typical feeding goes along with typical swallowing. If you have a child who does not feed safely due to a swallowing issue, it is definitely going to impact how their feeding develops. They are not going to have the same experience, based on what I just described to you.

Typical Reflexes Associated With Feeding

- Root Reflex-Stimulus presented near the infant’s mouth resulting in head turn toward stimuli and mouthing/rooting

- Suck Reflex-Sucking in response to stimuli within the oral cavity

- Suck/Swallow-When liquid is moved into the mouth infant sucks/swallows

- Tongue Thrust-When lips are touched infant protrudes the tongue

- Gag-Solid object propelled forward and outward of infant’s mouth

Now, let's look at some typical reflexes associated with feeding. There are more than these, but I am just sharing some.

The root reflex is where we stimulate near the infant's mouth, and they turn their head and mouth and root. I have seen things all over the board, but typically, this will integrate around four to six months. I have seen this integration at three months, but we do not see it anymore after about six months. The infant is more volitional at that point.

There is also a suck reflex, where the infant sucks on anything in their mouth. This also hangs around as a reflex until three to six months or so.

The suck-swallow reflex is where they suck and swallow anything in their mouth. This is present throughout the rest of our lives to some degree, but it becomes more volitional as we mature.

Tongue thrust is when the infant's lips are touched, and they protrude their tongue. This reflex integrates around four to seven months.

Lastly, there is the protective gag reflex. It is when a solid object is propelled forward and out of an infant's mouth if they can get it out. What is important to know about the gag reflex is that it does not necessarily integrate. What happens is that in an infant, it is very anterior. The gag reflex moves posteriorly over time as infants put hands, toys, and food in their mouths. This allows us to eat things we want to eat without too pronounced of a gag reflex.

Important Milestones

- Sucking develops in utero ~ 15-16 weeks gestation

- Swallowing develops ~ 14-17 weeks gestation (Fetus swallows approximately 15 oz of amniotic fluid per day)

- Suck, swallow, breathe synchrony emerges between 32-34 weeks

- Synchrony stabilizes ~ 37 weeks

Here are some other interesting milestones. Sucking develops in utero at approximately 15 to 16 weeks gestation. Swallowing happens at about 14 to 17 weeks, and the fetus will swallow about 15 ounces of amniotic fluid per day. The suck-swallow-breathe synchrony emerges between 32 to 34 weeks. I have also seen this around 34 to 36 weeks. It is critical that the suck-swallow-breathe actions are in synchrony so the infant i not trying to breathe while they are swallowing. Synchrony stabilizes at about 37 weeks when the infant uses the proper rhythmicity during feeding.

This leads me to talk about traditional norms for feeding development.

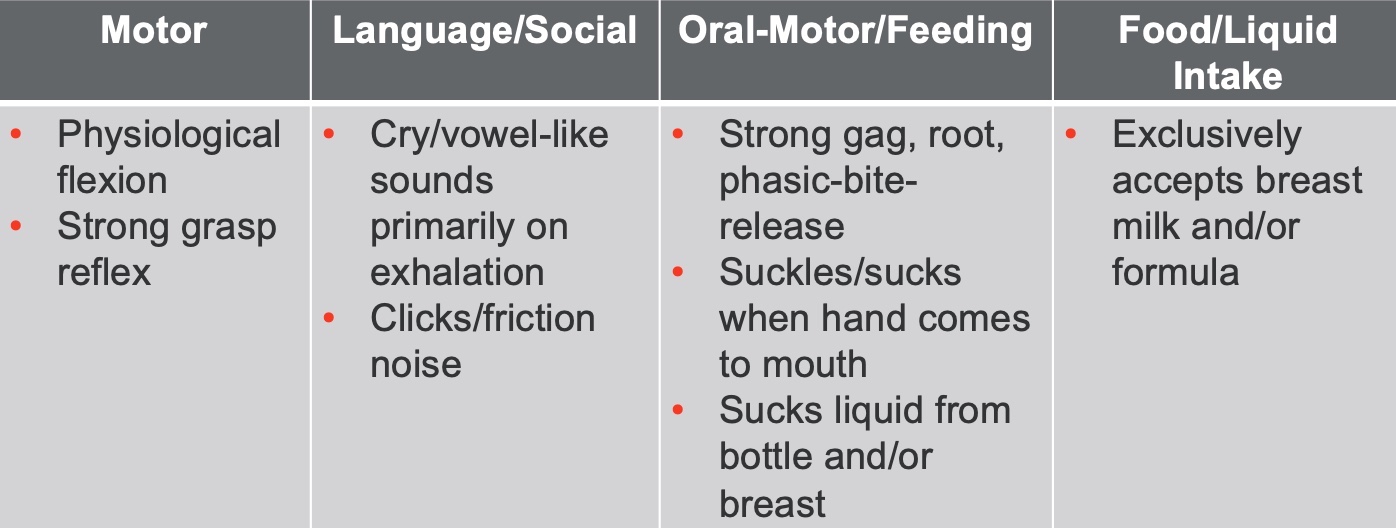

Newborn Milestones

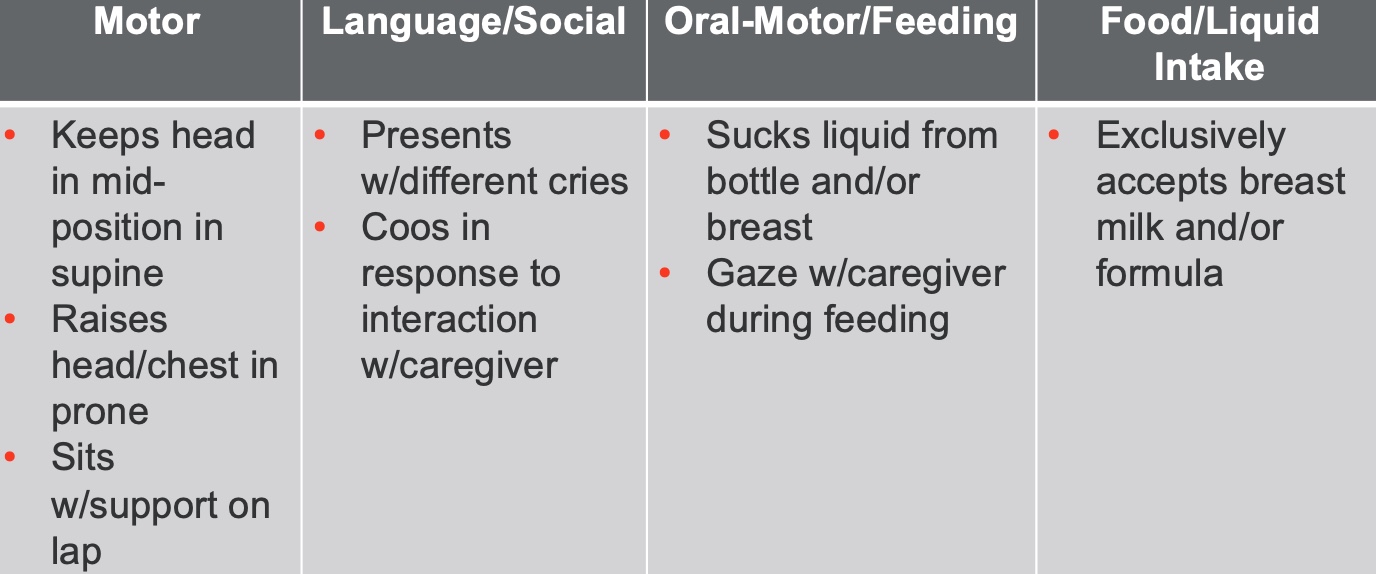

Figure 2 shows milestones in a newborn.

Figure 2. Newborn feeding milestones.

A newborn is driven by physiological flexion. They are squishy and have a strong grasp reflex.

Their cry has vowel-like sounds due to the potential oral cavity, as there is not a lot of room. A newborn is a highly reflexive individual at this point with strong gag and suckle reflexes. They take all nutrients from the breast or bottle because that is what they can do now. They suckle with an anterior-posterior tongue movement, instead of sucking. Sucking emerges as time goes by, as there is not enough room for an up-and-down movement, which is what constitutes a suck.

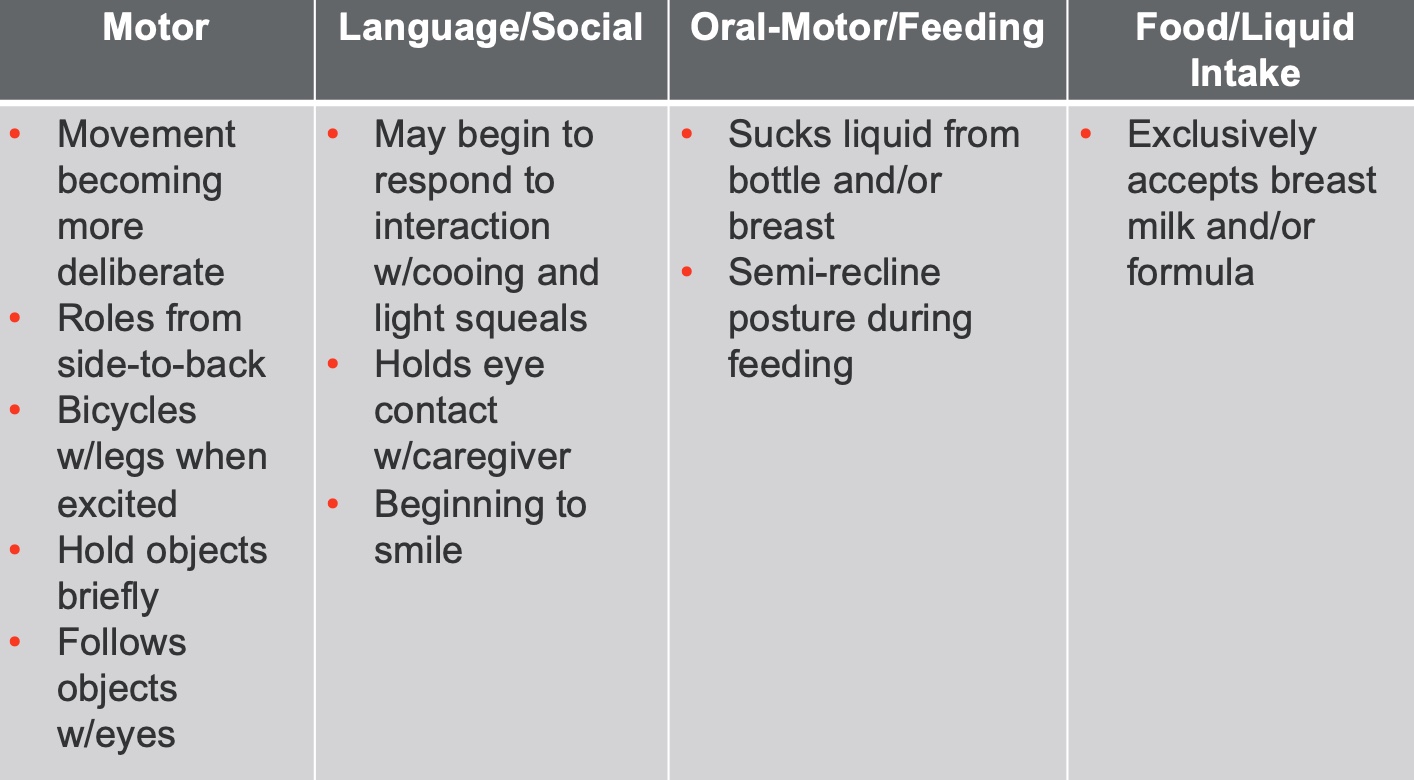

1-2 Months Milestones

Infant milestones for one to two months are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. One to two months feeding milestones.

You start to see changes in the infant, They may be rolling from side to back, following some objects with their eyes, and becoming more deliberate and less reflexive. With oral-motor, they still take in liquid from the bottle or breast and get some sucking intermixed with some suckling. They are also semi-reclined for feeding during this period.

2-3 Months Milestones

Figure 4 shows two to three-month milestones.

Figure 4. Two to three months feeding milestones.

Around four months, you see a big change with the elongation of the pharynx and growth in the mandible. The infant cannot only do some things from a motor standpoint, but they may be cooing because they have more room to do so. They are also less reflexive. They present with different cries, which is important for communicating with caregivers. "Ooh, what cry was that?" "I think it is a dirty diaper," or "Oh, that is a scared cry," or "Oh, that is a hungry cry." There is more gazing with the caregiver and the beginning of attachment. They are still taking breast milk or formula.

3-4 Months Milestones

Three to four-month milestones can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Three to four months feeding milestones.

At this age, the head, eyes, and hands are more oriented to the midline. There is also some random babbling at this point. They are starting to use their hands to hold the bottle or touch the breast as this is still their primary eating. The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend holding complimentary foods like purees and things like that until six months. It used to be four months. That being said, some folks still go ahead and introduce that to their infant, and you may see this in the clinic.

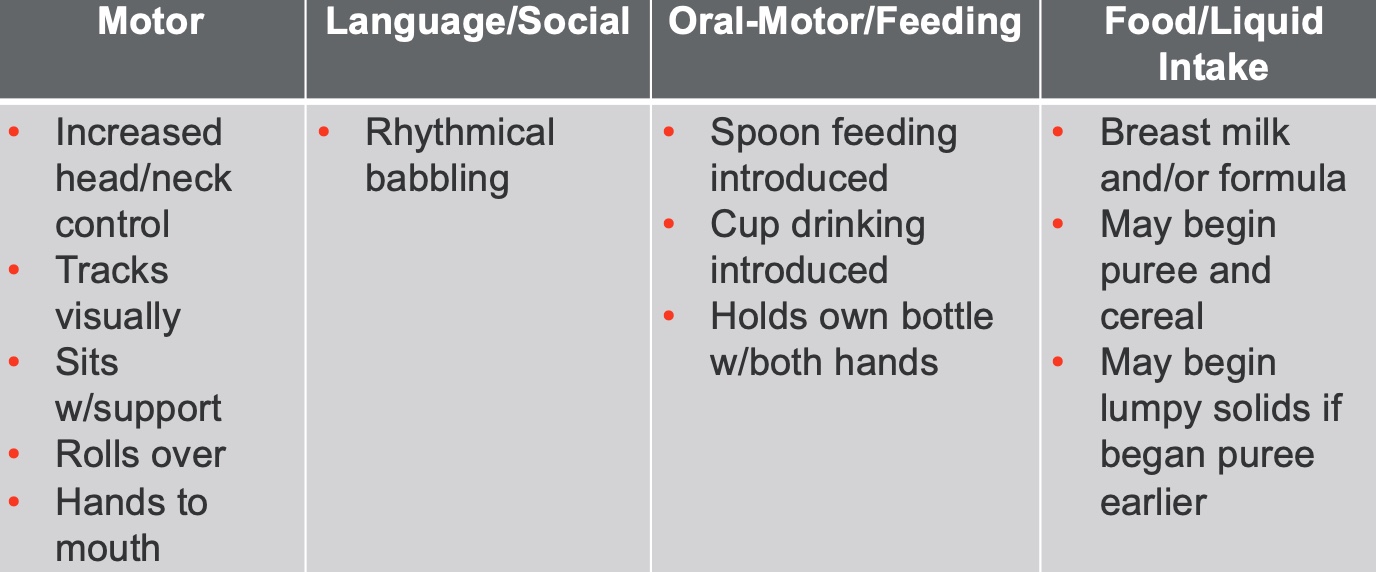

5-6 Months Milestones

Five to six-month milestones are in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Five to six months feeding milestones.

At five to six months, we are starting to see increased head and neck control. They have improved head and neck control and start to have the ability to sit independently. This increased upright posture of their head and neck and room in their mouth allows more oral motor movement and some rhythmical babbling.

They are sitting more with support, opening up their world in many ways. They are bringing their hands to their mouths and start spoon-feeding. I also always encourage families to introduce a cup at this age, and here is why. I want to make a cup a part of their life so that it becomes familiar before weaning them from the breast and bottle. It helps with that later transition.

The majority of infants begin to have puree and cereal around six months. If parents have introduced the infant to puree and cereal at four months, they may have some lumpy solids.

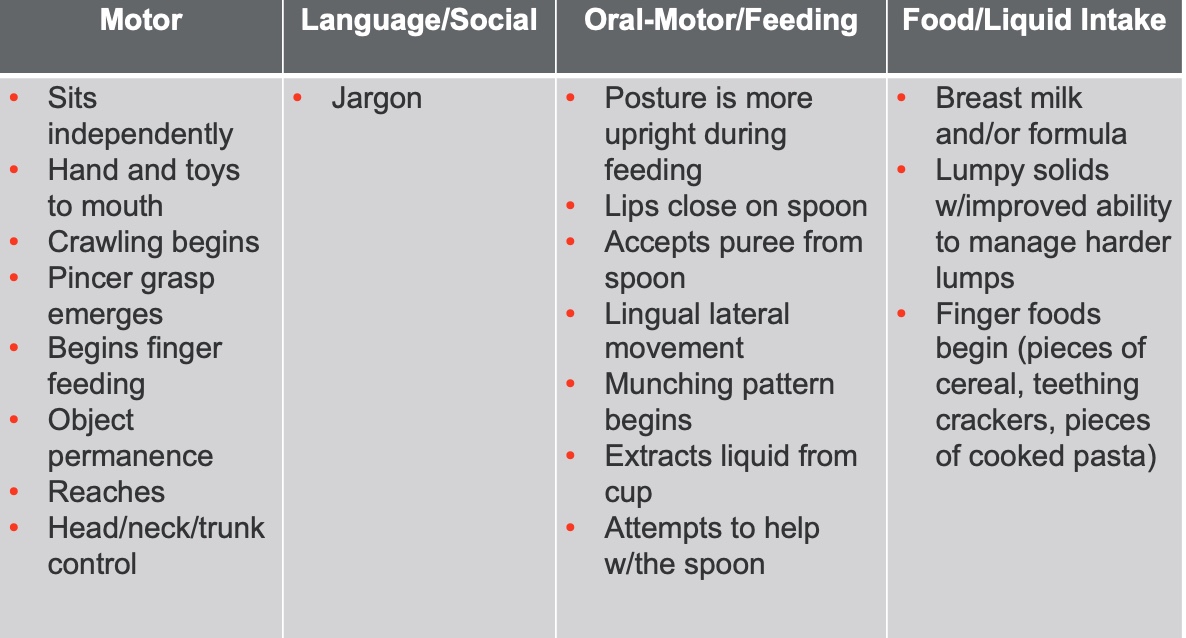

6-9 Months Milestones

Now, six to nine months is an exciting time (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Six to nine months feeding milestones.

If all is working well, the child will be sitting independently and may be crawling at this age. They also develop a pincer grasp which is going to give them independence as far as feeding. Additionally, object permanence is going to be developing. They have many motor skills developing. They have better head, neck, and trunk control and can close their lips around a spoon to accept pureed food.

They also have lingual lateral movement emerging around seven months and are getting pretty good by nine months. They are able to chew on different planes, and munching is beginning around six months. They are practicing chewing up and down. Hopefully, they can also extract some liquid from a cup.

You might still see breast milk and formula consumption at this stage, but they may also be eating lumpy solids due to increased lingual lateralization. Many finger foods are added, like cereal, crackers, and cooked pasta.

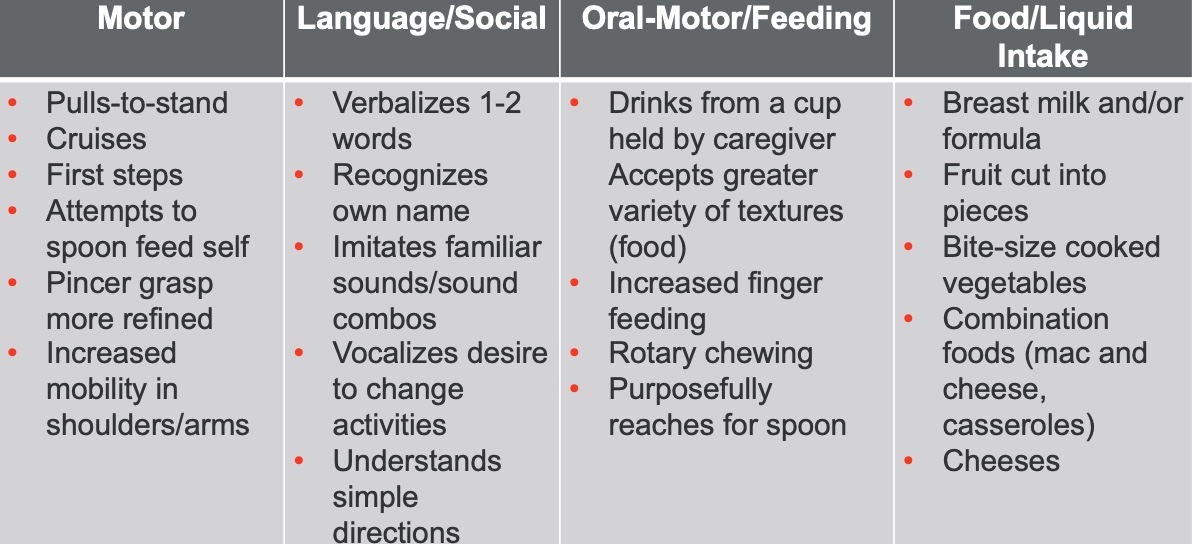

9-12 Months Milestones

Figure 8 shows nine to 12 months.

Figure 8. Nine to 12 months feeding milestones.

At nine to twelve months, they pull to stand, cruise, and take some first steps. Individuation is exploding at this point if all has gone well. Pincer grasp is more refined, and there is more mobility in their shoulders and arms. There are also many things going on with language due to oral-motor development. They drink from a cup if they have had some experience and accept a greater variety of textures. There is increased finger feeding, and you may even see some rotary chewing because they have been practicing diagonal movements of the jaw toward the 12-month mark. They are still drinking breast milk or formula, and eating things like fruit cut into pieces, bite-sized cooked vegetables, and a combination of foods. Around 12 months, you start to see infants eating what they will eat later, but it may be cut up a little bit more.

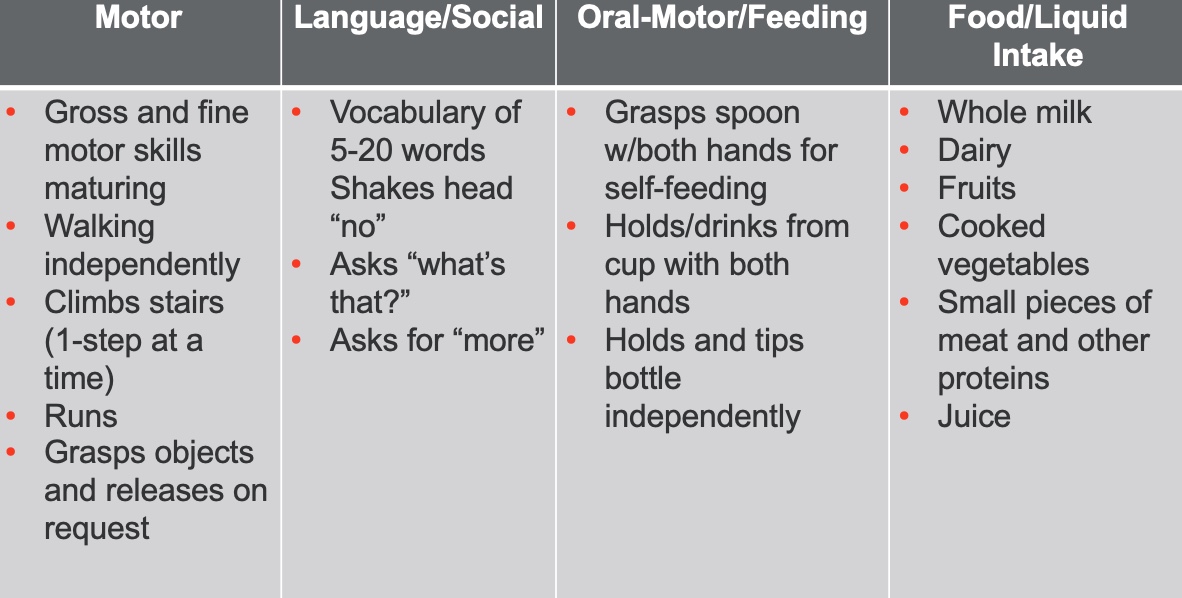

12-18 Months Milestones

Figure 9. Twelve to 18 months feeding milestones.

At 12 to 18 months, if everything is going okay, we start to see increased walking efficiency and may even be running. Their vocabulary is getting bigger, with five to 20 words, and they are learning to shake their head no. As they get closer to 18 months, their motor skills become more refined, and they start asking for more when eating.

I would like to point out that some people do not like to introduce juice to their children, while others are vegetarians or vegans and will have different food offerings. The child's environment is going to also be part of feeding development.

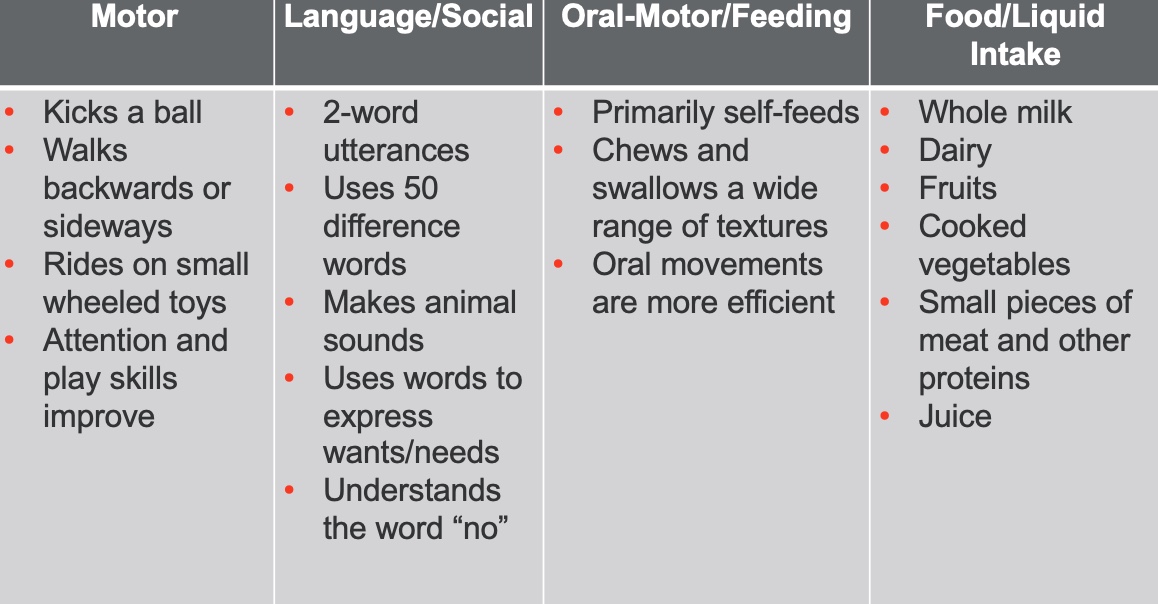

18-24 Months Milestones

At 18 to 24 months, we continue to see more refined movements and more advancement development across the board (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Eighteen to 24 months milestones.

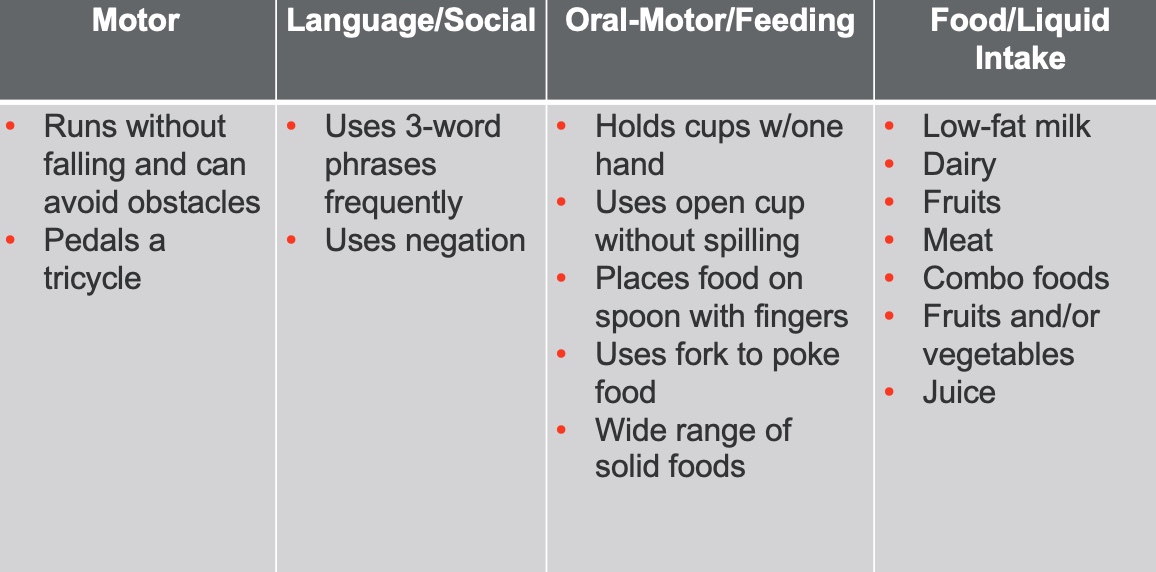

24-36 Months Milestones

The same is true for 24-36 months in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Twenty-four to 36 months milestones.

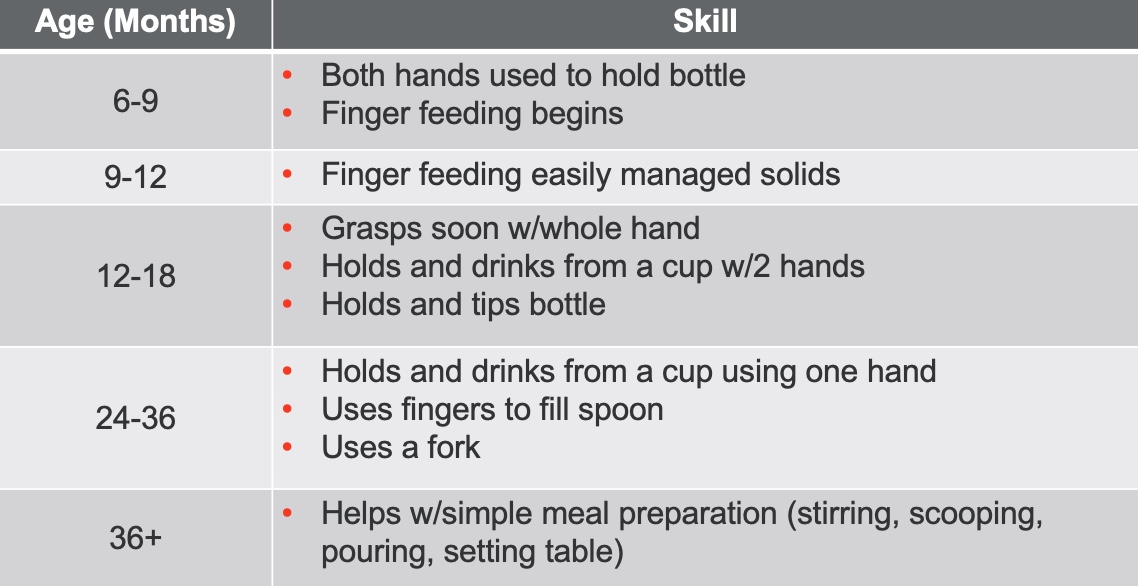

Self-Feeding Milestones

Now, this brings me to self-feeding, and again, go back to what we said in the beginning (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Self-feeding milestones.

In some cultures, people do not use utensils or only use specific utensils. It is going to vary according to the family. This is only one version of a milestone chart that I have seen.

In this chart, infants use both hands to hold the bottle at six to nine months, and finger feeding is beginning. Finger feeding and easily managed solids around nine to 12 months. You can see the other progression of tasks in this chart. I am not going to read the whole thing to you, as these activities may vary. However, you can share this with family if you think it would be helpful.

Baby-Led Weaning

- An approach to complementary feeding

- Emphasizes infant's ability to self-feed

- Minimally-processed foods vs. puree

I have referred to typical feeding development from a traditional sense throughout this talk. The phenomenon of baby-led weaning came out a while ago, and it is an approach to complementary feeding. It emphasizes an infant's ability to self-feed and be part of the family meal. It emphasizes that foods should be minimally processed and not pureed.

I have read much about this method, as my children are older, and I did not use this. There are arguments for and against this method. Proponents of baby-led weaning say it is a great way for the infant to be able to try all of these foods and be in control. The infant is also a part of the family meal.

What about choking? Proponents say there is a difference between gagging and choking. Another argument is that they gag a lot; won't that create feeding aversion? The response is that they do it themselves and do it with toys and other things when they are mouthing them. It is not necessarily like somebody is force-feeding them and creating that gag reflex. Feelings about baby-led weaning are all over the board.

There is more research about this every year. I have to say, though, the sample sizes are small, and many are surveys. Be aware if you go into a pro-baby-led weaning household, you are not going to see typical development in the same way that I have described.

Summary

- How "typical" experiences impact the infant/child

Early Experiences and the Brain

- Most regions of the brain contain all of the neurons they will have by birth.

- An ongoing process of wiring/re-wiring connections among neurons

- New synapses are formed through use/others that are unused are pruned away

- Over-pruning can occur when a child is deprived of normally expected experiences.

Most regions of the brain contain all the neurons they will have by birth. I want to talk about the fact that the basic architecture of the brain is constructed through an ongoing process beginning before birth and continuing into adulthood. You have simple neural connections at first, which are then followed by more complex ones.

For the first few years of life, you can have like a million new neural connections every second, and early childhood brains are programmed to let all of this happen. Still, there comes a point where pruning occurs if certain tasks or skills are not happening. In contrast, what is used often stays.

In typical feeding development, we want all of the experiences to reinforce positive feeding and healthy feeding habits. We want them to have many positive experiences because if they do not, they are at risk of eating, feeding, and swallowing motor areas being pruned.

Emotional Development and the Brain

- Infants have the fundamental task of determining whether their needs are met.

- When adults are responsive, the infant perceives them as a source of safety.

- Infants who feel safe/secure can focus on exploring, allowing the brain to develop.

The other part of that is emotional development in the brain. Infants have the fundamental task of determining whether their needs are met. If they are not met, and there is a lack of responsiveness, it will result in less interaction and exploration, and the infant will not feel safe. They are also not going to enter the individuation phase that we talked about earlier. If an infant feels safe and secure, they can focus on what we want them to focus on exploring food and their world.

Harvard has a webpage that talks about brain architecture. It is an excellent website with interesting research about brain architecture, genes, and infants and development.

Early Experiences, the Brain, and Eating

- Positive early experiences and Feeding

- Communication acknowledged and needs met by caregiver = Safety/Security

- Safety-Security = Infant/child who is free to experiment, explore, and practice

- Experimentation, exploration, and practice = Reinforcing neuronal connections and overall function

Communication is acknowledged, and needs are met by a caregiver. This equals safety and security for an infant. If there are safety and security, that equals an infant or child who is free to experiment, explore, and practice. Experimentation, exploration, and practice are equal to reinforcing all the neuronal connections and overall function of this developing person.

Feeding Development: Disrupted

What we probably want to end with today is that we love typical feeding development. It is the most amazing, miraculous thing ever. However, we are going to have infants and children who have things that happen to them that disrupt their ability to develop feeding in a normal, typical way.

Factors That Can Impact Typical Development

- Medical Diagnoses & Complications

- Developmental Diagnoses

- Temperament

- Psychosocial Diagnoses/Issues

- Nutrition Problems

- Environmental Factors

The factors that can do that are medical diagnoses and complications, developmental diagnoses, temperament, psychosocial diagnoses and issues, nutrition problems, and environmental factors. All of these things can impact somebody's ability to develop a positive relationship with food and develop typically.

Summary: Feeding Development: Using Your Knowledge to Guide Intervention

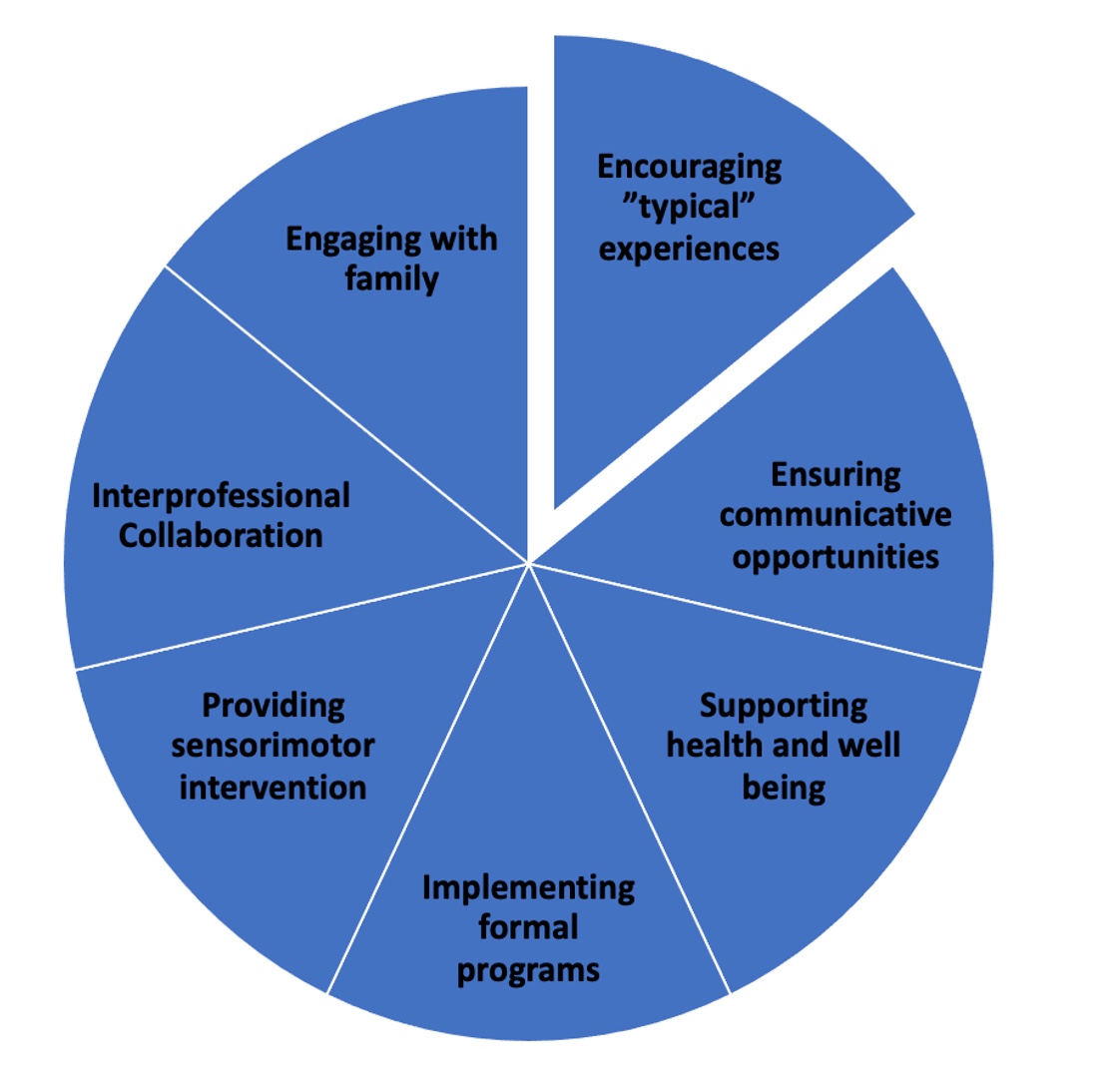

Overall feeding development is summarized in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Pie chart of feeding development.

I want you to consider how to use this in your therapy sessions. This is not a presentation on therapy and interventions, but hopefully, I opened your eyes and mind of how you can use this to guide your intervention.

You may interprofessionally collaborate with speech pathologists, physical therapists, dieticians, or whomever.

You are also still going to engage with your families.

You may provide sensory-motor intervention to help children or implement formal programs. I have been trained in sequential oral sensory approach with Dr. Kay Toomey and food chaining, both fantastic formal programs. I have also used them together.

You want to support the health and well-being of a child. For example, you want to ensure the child can communicate, even if you are not a speech pathologist. Anytime a child is doing something that is causing fear, it makes it 20 times worse if they can not communicate. It can be as simple as giving the child communicative opportunities like yes or no.

All of these components are going to be in your therapy, but now I want you to think about all of this in the context of what a typical experience looks like.

If you are working with a child with some feeding problems, deficits, or delays, I go in with my techniques, food choices, et cetera. We have been trained to intervene and evaluate so thoroughly that sometimes we forget that encouraging typical experiences is going to be extremely important.

Questions and Answers

How does interoception work with a child that has feeding issues due to neurodevelopmental delays, such as those born early or diagnosed with something that affects typical feeding?

This is something that I am very passionate about. I have worked in many NICUs. Some NICUs are developmentally appropriate and use cue-based feeding. If the infant is stable enough, is rooting, and wants some food, we feed them, either breastfeeding or bottle feeding, depending on their situation. If I am feeding an infant a bottle and they start to show me about halfway through that they are done, or they do not enjoy it, I need to honor that cue and stop. If this cue is not recognized or responded to, what happens is that interoception is damaged. "I am full, but they keep feeding me." This negative happens more with infants that are premature, have delays, cannot communicate as clearly, or if we are concerned that they are not gaining enough weight. I also think kids with tube feeds do not always know what "full" is.

What feeding course do I recommend to be certified?

I am not sure as far as a certified course. There are a number of great courses out there, and I think I have some in my references. You are also welcome to contact me.

What if there are any oral restrictions, like a tongue, lip, or buckle tie? It seems like that would impact that elongation and change the oral structure.

The tongue has a huge impact on the palate. If you have a lingual tether, your pharynx will still elongate, but it can impact your function. The tongue is not free to move, and the child has to learn compensatory strategies. I had an infant with a significant lingual tether, and a neonatologist said, "It is okay. They'll be able to get through it." I told him that was not true. A term newborn may be able to compensate, but if the infant is premature with respiratory distress and other complications, they do not have the same ability. They are working hard to live.

What is a true oral cavity?

A true oral cavity comes around four months of age. This is when you have a vertical elongation of the pharynx, and the mandible grows forward and downward. A newborn's oral cavity is so tight because the sucking pads are pushing in.

We used Ellyn Satter's philosophy and baby-led weaning as a family, which has been beautiful for our family. However, it is not the right choice for everyone.

That is what I have heard. I always hate to do just one thing. I think baby-led weaning has great points, but I also like to keep other options open, like offering puree. Pureed food can be part of the developmental sequence that helps that child to be able to get to the next step. People have to do what is right for their family.

What are your thoughts about baby-led weaning in regards to oral motor development?

We are trying to develop these less complex patterns into more complex patterns. For the most part, development is supported by having pureed food as part of that developmental sequence. However, I am not saying you cannot do some of that with baby-led weaning. I do not want to throw anything out because if the experience is positive, we hope it continues for the kids and the infants.

Does texture affect the gag reflex?

As I am talking to a bunch of OTs, I am treading softly because this is not part of my role. I used to work with a lot of great OTs. One of the things that I would hear from them, and it made sense to me, was that a child who did not tolerate things like rice on their hands or wet things, may not tolerate oral items either. I think a gag reflex could be increased or heightened with somebody with an aversion to textures. And, I think certain textures can also break apart more. It just depends on the oral motor phase that person is in.

Can difficulty with food textures be caused by developmental sphincter issues or a lack of variation?

I am not sure what we mean about developmental sphincter issues. All I can say is that I have seen children with difficulty with textures of foods for a variety of reasons. Some have had oral tethers and are understandably avoidant of textures that they cannot manage. I have also seen infants and children with swallowing problems because it is difficult to manage the bolus orally. There can also be severe reflux that causes avoidance of certain textures, like lumpy things. I am thinking that many kids think that if it came back up, it would not feel as good. I have seen many with texture issues for a multitude of reasons. If you mean developmental sphincter issues such as a reflux issue, I could see that reflux definitely could impact their experience.

References

Addessi, E., Galloway, A. T., Wingrove, T., Brochu, H., Pierantozzi, A., Bellagamba, F., & Farrow, C. V. (2021). Baby-led weaning in Italy and potential implications for infant development. Appetite, 164, 105286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105286

Alexander, R., Boehme, R., & Cupps, B. (1995). Normal development of functional motor skills: The first year of life. London: Psychological Corporation.

D'Auria, E., Bergamini, M., Staiano, A., Banderali, G., Pendezza, E., Penagini, F., Zuccotti, G. V., Peroni, D. G., & Italian Society of Pediatrics (2018). Baby-led weaning: What a systematic review of the literature adds on. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 44(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0487-8

Lefton-Greif, M. A. Feeding/swallowing development and disorders in children: For graduate students [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from www.asha.org/Events/ convention/handouts/2010/1337-Lefton-Greif-Maureen/

Hawley, T. (2000). Starting smart: How early experiences affect brain development. Second Edition. Ounce of Prevention Fund.

Johnson, C. (1995). Mosby's comprehensive dental assisting: A clinical approach (B. Finkbeiner, Ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Jones B. L. (2018). Making time for family meals: Parental influences, home eating environments, barriers and protective factors. Physiology & Behavior, 193(Pt B), 248–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.03.035

McCarthy, J. (2008). Feeding infants and toddlers strategies for safe, stress-free mealtimes [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from www.asha.org/Events/convention/handouts/ 2008/1884_McCarthy_Jessica_L/

Morris, S.E. (1990). Issues in anatomy and physiology of swallowing: Impact on assessment and treatment of children with dysphagia. Retrieved from https://www.new- vis.com/fym/pdf/papers/feeding.10.pdf

Morris, S. E., Klein, M. D., & Satter, E. (2000). Pre-feeding skills: A comprehensive resource for mealtime development (2nd ed.). Austin: Pro-Ed.

Rowan, H., Lee, M., & Brown, A. (2022). Estimated energy and nutrient intake for infants following baby-led and traditional weaning approaches. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics: The Official Journal of the British Dietetic Association, 35(2), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12981

Satter, E. (2000). Child of mine: Feeding with love and good sense. Palo Alto, CA: Bull Publishing.

Satter, E. (1987). How to get your kids to eat…but not too much. Palo Alto, CA: Bell Publishing company.

Thomas, A., Chess, S, & Birch, H. (1970). The origin of personality. Scientific American, 102-109.

Utami, A.F., Wanda, D., Hayati, H. et al. (2020). Becoming an independent feeder”: Infant’s transition in solid food introduction through baby-led weaning. BMC Proc, 14 (Suppl 13), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-020-00198-w

Williams Erickson, L., Taylor, R. W., Haszard, J. J., Fleming, E. A., Daniels, L., Morison, B. J., Leong, C., Fangupo, L. J., Wheeler, B. J., Taylor, B. J., Te Morenga, L., McLean, R. M., & Heath, A. M. (2018). Impact of a modified version of baby-led weaning on infant food and nutrient intakes: The BLISS randomized controlled trial. Nutrients, 10(6), 740. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10060740

Citation:

Williams, R. M. (2023). Feeding development: What is typical? OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5590. Available at www.OccupationalTherapy.com