Introduction

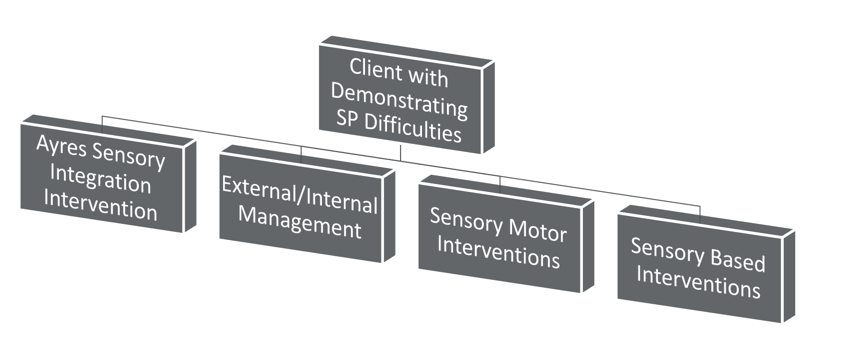

There are different interventions that are used to address the problems that are impacting occupational performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sensory processing theories.

We have Ayres Sensory Integration® intervention, external/internal management, sensory motor interventions, and sensory based interventions. There is a fairly large push, I think from the national association but also from funding sources, to demonstrate the value of what we do as pediatric occupational therapists. I think one of the challenges that we have faced over the past 30 years is being able to communicate that value of what we do when we are working with individuals with sensory processing difficulties. This stems from how we classify and diagnose and how we are communicating the different interventions that we are using and how they are different. They may fall under the umbrella of sensory integration or sensory processing theory, but that does not equate to actual sensory integration intervention. I think this has created some confusion. I think we have an opportunity to better communicate the differences among those interventions, and why we are using them with different occupational performance problems, in different settings, and with different populations.

Ayres Sensory Integration® Intervention

Sometimes it is termed as occupational therapy using a sensory integration frame of reference. There are four foundational components (Roley, Mailloux, Miller-kuhaneck, & Glennon, 2007).

- Hallmarked by its individualization to the child’s needs.

- Therapist to adjusts the type of activity, its duration, and intensity from varying moments and glimpses of the child’s interests.

- Therapists attempt to tap into a child’s inner drive (interests, motivations, and values) to facilitate a higher effort with the therapeutic activities.

- It is a constellation of principles that are sequenced together to facilitate a functional adaptive response.

It is an individualized approach to address the client's needs. The therapist adjusts the activity, the type of activity, how long the activity lasts, and how intense that activity lasts throughout the session, but also tapping into the child's interests. The therapist, through that process, is identifying the child's inner drive, or what they are motivated by and what they value. By doing so, you can facilitate a higher level of effort and or difficulty in those therapeutic activities. It is a constellation of sensory-based principles that are sequenced together to facilitate a functional adaptive response. We do not hear the term adaptive response much anymore. It comes from the 1950s and '60s when Dr. Ayres developed her theory. It was how these concepts were communicated in neuroscience in those days.

A functional adaptive response is an appropriate response given the parameters of the task and the expectations of the environment. Wherever we are functioning, those change. So when we are working with individuals with sensory processing difficulties, we are looking to see if the response is becoming more and more in line with the expectations of the environment and the task. One of the things that has bubbled up over the past two decades is a lot of folks saying that they are doing sensory integration therapy. We see this with a wide variety of folks in addition to the occupational therapy profession like speech language pathology, physical therapy, the rehab profession, chiropractics, developmental optometry, and psychology. In fact, there are some psychologists that are saying that they are doing sensory integration therapy. This has created a challenge. You might think you are doing sensory integration, but are you doing the intervention that has been manualized? Specific things need to occur in order to ensure that.

A) There has to be fidelity to the intervention,

B) It has to be in line with the outcomes that have been documented in the literature.

There has been some confusion on what is sensory integration versus what is sensory stimulation, and there is a lot of overlap and redundancy. The other thing that we see is there has been some exclusion of occupational therapy professionals from evaluation and treatment of individuals who have a sensory processing disorder. We want to get back into those circles where we have more expertise, more credentials, and a better understanding of what underlies sensory processing, what sensory integration is, how it manifests, and the most effective ways of creating functional change.

Trademark

Why was Ayres sensory integration® intervention trademarked?

- Confusion between sensory integration intervention and sensory stimulation techniques implemented by OT’s, other health professionals, or non-credentialed individuals.

- The exclusion of OT from the evaluation and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with sensory processing disorders.

- The use of sensory integration techniques as a reward as a part of other behavioral based interventions.

Manual

Why was Ayres sensory integration® intervention manualized? Instead of guessing, it gives us some parameters and provides a manual. It identifies how Ayres Sensory Integration® Intervention differs from other sensory-based interventions.

- Document how the intervention differs from other sensory interventions OT’s use.

- Alignment of SPD, intervention objectives, and outcomes.

- Knowing that specific outcome may be attributed to an intervention.

- Replication of an intervention across cases

- Ensure that the intervention was addressing occupation based outcomes.

- Ensure the intervention practices align with the evidence that is being generated.

Constructs

There are not only this constellation of sensory principles, but there are 10 constructs that need to be included in order to be classified or characterized as Ayres Sensory Integration® intervention. Since 2007, we have seen a lot of new research that has been published on the efficacy of Ayres Sensory Integration® intervention, and how they are using a manualized approach. The manualized approach can be found in a wide variety of publications now. There are several research articles that have been published in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy, and a manual on sensory integration intervention for individuals with autism that has been published by AOTA, so these things are out there.

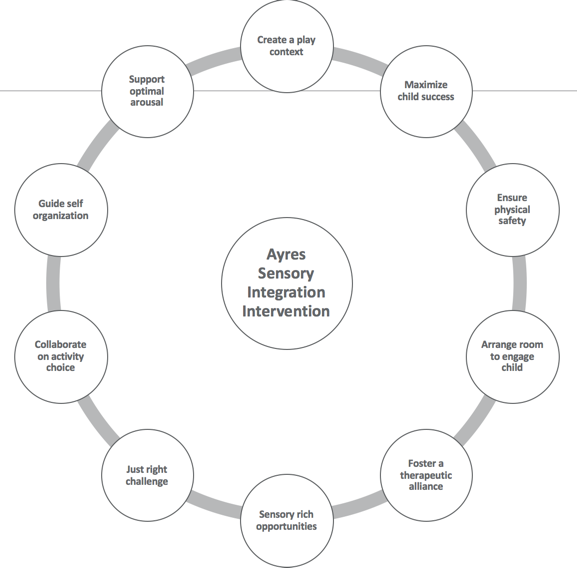

Figure 2 shows the constructs for Ayres Sensory Integration® (Parham, Cohn, Spitzer, et al., 2007; May-Benson & Schaaf, 2015).

Figure 2. Constructs of Ayres Sensory Integration®.

1. First and foremost, Ayres SI tends to be very rich with sensory experiences. It is not just one sensory experience, it is more than one. If we look at Ayres' original work, it was heavily influenced and rich with proprioceptive, vestibular, and tactile sensory experiences.

- Tactile

- Vestibular

- Proprioceptive

- Visual

- Auditory

- Gustatory/Olfactory

- The intervention involves more than one sensory modality/channel

- Proprioceptive

- *Vestibular (Core of SI)

- Tactile

According to Ayres, the more sensory systems we are exposing the client to and that they are attempting to process, the more integration occurs. Sensory Integration Intervention® is not just one sensory system that you are working on.

2. The next thing is that we provide the just right challenge. We want to present challenges to the client that are not too hard but not too easy. We want to facilitate adaptive responses and also provide challenges to the client's praxis skills, so we do this through scaffolding. When you paint your house, you need a scaffold to get higher and higher to reach those hard places. There are hard and soft scaffolds. A soft scaffold would be the type of prompts and cues that you provide, and a hard scaffold would be that you make changes to the physical space to make them more successful.

3. The next principle is that the occupational therapist collaborates on the activities with the child. It is not a therapist-driven session nor is it a child-driven session. It is a collaboration. The child needs to have some control over the activities they engage in, but you also want to make sure that there is not an overly-prescriptive schedule of activities. The collaboration is based upon what the child is motivated to do and what they respond to. There is a lot of at the moment clinical reasoning that occurs.

4. The next principle is that the therapist needs to support and guide self-organization. One of the goals of Ayres Sensory Integration® intervention is to facilitate and see self-organization. We want the client to be able to make choices and plan out their own behavior. It really is based upon their cognitive and emotional abilities, but we also want them to initiate and develop ideas, plans, and activities. This goes back to this idea of a functional adaptive response. Can they do it and self-organize in environments or with tasks that may be challenging? Is their response in line with the expectations of the environment and the expectations or the capacity of the task?

5. Another principle that we want to make sure that the therapy situation is helping the client maintain an optimal level of arousal. We do this through the activity or the environment. A lot of these activities tend to be preparatory, but it is to try to get them to be emotionally available to engage in what we want them to do. The other way we do this is through the goodness of fit. The goodness of fit is where we, as therapists, align our responses to where the client is. For example, if they are over-aroused, we try to lower the tone of voice, speak softer, or modify the environment. Again, we want to get them to that point where they are emotionally available to play, to learn, to socially engage, to develop relationships, et cetera.

6. Take advantage of the primary occupation in children, which is play. We do this through different types of play: object play, social play, motor play, and imaginative play. Play is a primary construct, and in adults, this might be play in leisure or engaging in these things that tend to be more naturally motivating. They are the vehicle in which we then expose and engage the client in sensory-rich experiences.

7. Modify activities so that the child or the client can experience success. This again is the just right challenge.

8. We want to make sure that the client is engaging in these sensory-rich activities, but they need to do so in a safe manner. We need to make sure all the equipment that we have is safe. We might use a lot of swings and vertical surfaces. We want to make sure that it is safe, but we also want them to take risks as well. We also want to make sure that our proximity is always supportive of the child and their actions. This has been an issue as some kids have been injured.

9. The environment should provide sensory exploration and occupational performance. What do I need to do that? Do we need to have these real expensive sensory rooms? If we look back at Dr. Ayres, she originally did it in a trailer that was on the property of elementary schools. It was not in these elaborate gyms that we see now. She was just trying to find ways to provide sensory-rich experiences that were motivating for the clients.

10. Finally, we want to establish and maintain a therapeutic alliance, which means we respect the client's emotions. We convey positive regard towards the client. We want to try to connect with the client. We may not always connect with the client, but that is our ultimate goal. We want to make sure that the climate that we have established is a climate of trust and emotional safety. The reason why this is really important is with a lot of our clients, that demonstrate sensory processing difficulties, we are asking them to trust new or confusing experiences or experiences. In order for them to take risks, we need to help them engage and feel like they can trust the physical spaces, the activities, and us as therapists as well.

Of course, it is much more complex than this, but that is a brief overview of Ayres Sensory Integration® intervention. Since about the year 2000, we have seen an explosion of literature evaluating the effectiveness of Ayres Sensory Integration®. These are coming out of several different institutions throughout the country, and they are effective. The key is to convey that to our funding sources.

Evidence

- Cases

- Schaaf, R. C., Hunt, J., & Benevides, T. (2012). Occupational therapy using sensory integration to improve participation of a child with autism: A case report. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(5), 547-555.

- Schaaf, R. C., Benevides, T. W., Kelly, D., & Mailloux-Maggio, Z. (2012). Occupational therapy and sensory integration for children with autism: A feasibility, safety, acceptability and fidelity study. Autism, 16(3), 321-327.

- Randomized Control Trials

- Schaaf, R. C., Benevides, T., Mailloux, Z., Faller, P., Hunt, J., van Hooydonk, E., ... & Kelly, D. (2014). An intervention for sensory difficulties in children with autism: A randomized trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1493-1506.

- Miller, L. J., Coll, J. R., & Schoen, S. A. (2007). A randomized controlled pilot study of the effectiveness of occupational therapy for children with sensory modulation disorder. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 228.

- Systematic Reviews

- May-Benson, T. A., & Koomar, J. A. (2010). Systematic review of the research evidence examining the effectiveness of interventions using a sensory integrative approach for children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(3), 403-414.

- Case-Smith, J., Weaver, L. L., & Fristad, M. A. (2015). A systematic review of sensory processing interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 19(2), 133-148.

- Watling, R., & Hauer, S. (2015). Effectiveness of Ayres Sensory Integration® and sensory-based interventions for people with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(5), 6905180030p1-6905180030p12.

If you look at the bottom three, there have been some systematic reviews evaluating the effectiveness of the approach. This is really what is helpful to then help convey to our funding sources.

Sensory Diets

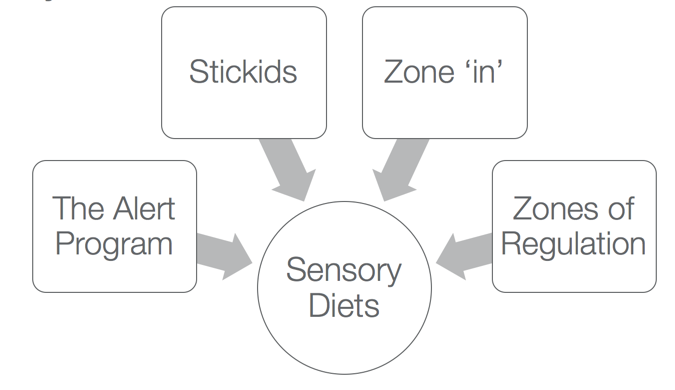

Our next topic is sensory diets (external/internal management).

Figure 3. Examples of sensory diets.

There are a bunch of different sensory diets (Figure 3), and I am not here to promote any given product or intervention. This is what is out there or what is being commonly used by therapists. If we go back to Ayres Sensory Integration® intervention, her assumption was that she was going to change how the clients processed sensory information. This is a change not only at the behavioral level, but it is a change at the physiological level or the level of the neuron. Sensory diets are definitely a step away from that.

- Sensory Diets

- Just as food is nourishment for the body, sensory input is nourishment for the brain. A sensory diet provides nourishment for the brain for children with sensory processing disorders (Case-Smith, 1996).

- The therapeutic sensory diet provides the optimal combination of sensations at the appropriate intensities for an individual child.

- For most typically developing children, the sensory diet does not require conscious monitoring by caregivers. The environment continuously feeds the child in a variety of nourishing sensations in the flow of everyday life.

- Prescribed type and amount of sensory stimuli.

- Externally implemented --------- internally managed

The assumption is that we need nourishment that comes from our environment. It helps us engage in those things that we find meaningful.