Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Implementing The Cognitive Behavioral Frame Of Reference In Outpatient Care For Youth With Mental Health Conditions, presented by Monica Jones, OTD, OTR/L, PMH-C.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to compare and contrast assessments and how they are administered, especially between CBT and the CB-FoR.

- After this course, participants will be able to distinguish unique documentation, billing, and plan of care implementation in this setting to increase confidence in this area.

- After this course, participants will be able to examine different treatment ideas to address occupational needs.

Introduction and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Foundations

Thank you for joining today, and I appreciate the introduction.

Dr. Aaron Beck is widely recognized as the founder of this psychological approach. His work emerged from recognizing that many psychological interventions lacked a strong evidence base. Today, cognitive behavioral therapy remains one of the most evidence-based psychological interventions and is regarded as the gold standard.

The approach emphasizes the interplay between behavior and cognition, focusing on how changes in one can lead to changes in the other.

CBT and OT

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and occupational therapy (OT) share historical roots dating back to the late 1960s when CBT principles began to assist occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) in teaching clients adaptive behaviors to enable engagement in their occupations. CBT components align closely with OT values, such as individualized approaches, collaborative efforts between therapist and client, and evidence-based, effective interventions. Notably, OT practitioners can receive training to administer CBT techniques, broadening their scope of practice.

However, research on integrating CBT within OT, particularly in outpatient settings, is limited. I found it challenging to locate substantial information in this area. My interest in CBT was initially sparked during my master’s program, where it was covered only briefly. This curiosity led me, in 2018, to pursue several training courses through the Beck Institute. I began incorporating these interventions into my outpatient clinic practice and observed remarkable client improvements within relatively short periods. After several years of seeing these outcomes, I started exploring ways to formally research the application of CBT within OT to better understand and substantiate its impact.

Research on CBT and OT

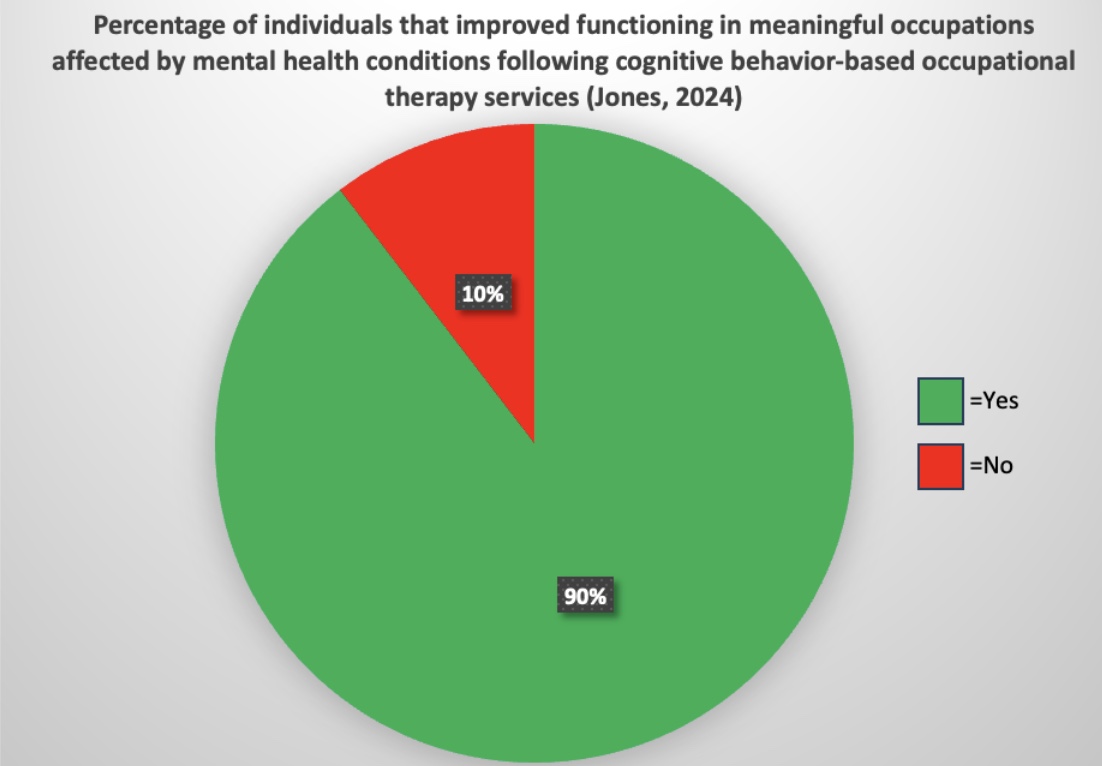

Conducting research independently can be incredibly challenging, and I quickly realized how much easier it is with support from academia. This realization motivated me to return to school for my doctorate in 2022 to publish my research. Once I received approval through the Boston IRB and began reviewing charts, I discovered something remarkable. Among individuals aged 8 to 78 who were living with mental health conditions, insomnia, or lifestyle challenges, 90% demonstrated clinically significant improvement (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of individuals who improved functioning in meaningful occupation following cognitive behavior-based OT.

This was measured as at least a two-point improvement in satisfaction and performance on the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. These results were achieved in an average of nine weekly sessions, each lasting 30 to 60 minutes.

I published this research in March of this year, and it has since shaped my primary goal: to educate as many people as possible about this highly effective intervention.

What qualifies OT practitioners to work in mental health?

Occupational therapy practitioners are well-qualified to work in mental health, which is essential to understand when implementing interventions like CBT in practice. You will likely encounter questions about whether this falls within our scope. Fortunately, the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) clearly defines our scope in the mental health space, including the focus on global and specific mental functions. This framework provides the necessary guidance to support our work in addressing mental health challenges as part of occupational therapy practice.

Global Mental Functions

Global mental functions encompass psychosocial temperament and personality, energy, and sleep. These functions influence how we respond to others and include questions like: Are we agreeable? Are we introverted or extroverted? Do we struggle with motivation? Are we getting good sleep? These elements are foundational to understanding a person’s overall mental health and their ability to engage meaningfully in daily activities.

Specific Mental Functions

Specific mental functions include higher-level cognitive processes such as attention, memory, perception, and thought, as well as mental functions related to sequencing complex movements, emotional regulation, and the experience of self over time. These functions encompass our ability to control ourselves, regulate our emotions, and distinguish reality from delusion. They also include how well we attend to tasks, utilize executive functioning skills, process and respond to environmental cues, and maintain a sense of personal identity. These elements are critical for engaging in meaningful activities and navigating everyday life.

The Cognitive Behavioral Frame of Reference (CB-FOR) (Jones, 2024)

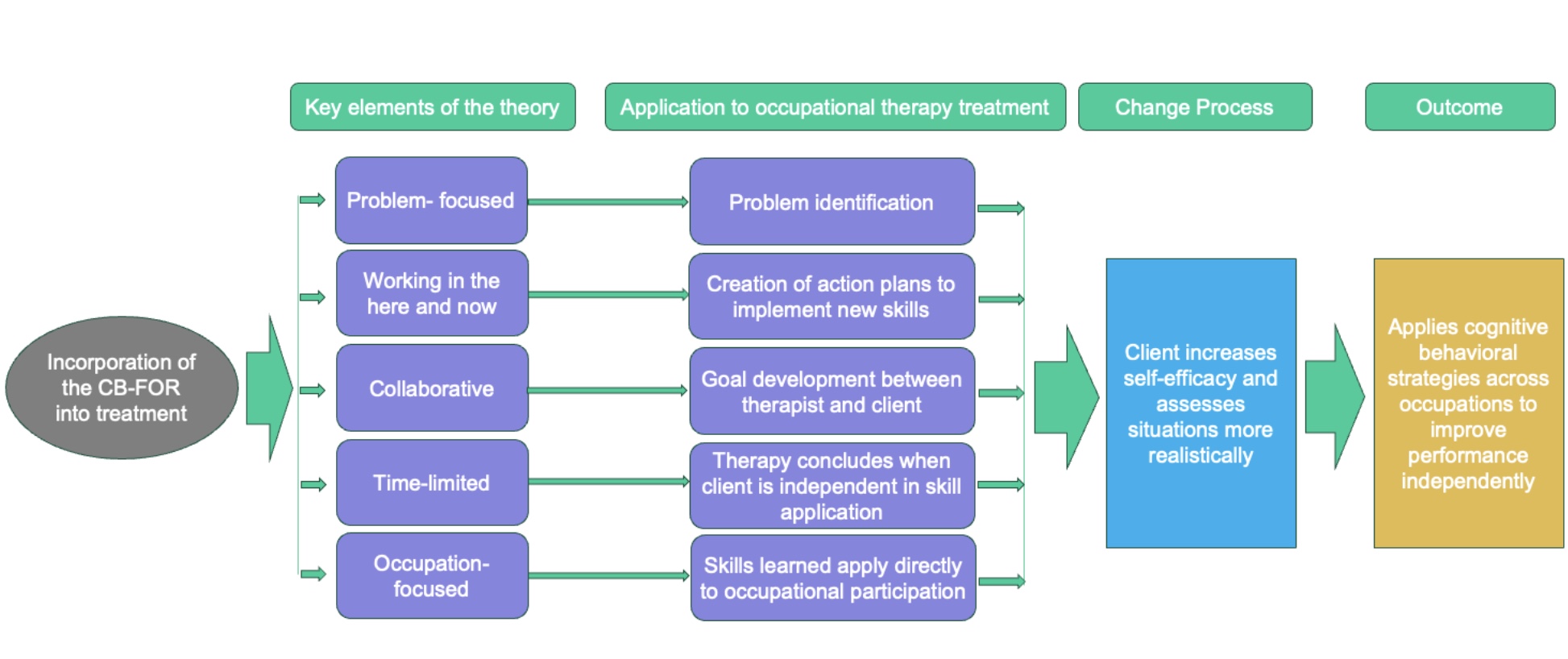

Figure 2 is the Cognitive Behavioral Frame of Reference (CBFOR) model I developed, adapted from my published research.

Figure 2. The Cognitive Behavioral Frame of Reference (CB-FOR). Click here to enlarge the image.

The model begins with integrating the CBFOR into treatment, serving as the foundational input. Key elements of this approach include its problem-focused orientation, its emphasis on addressing present concerns and working in the here and now, its collaborative nature between therapist and client, its time-limited structure, and its occupation-centered focus.

The model is applied within occupational therapy by identifying specific occupational challenges, collaboratively developing action plans to address them, and implementing new skills or setting meaningful goals. Therapy concludes when the client achieves independence in applying these skills, directly contributing to their occupational engagement.

The process of change unfolds as clients enhance their self-efficacy and gain the ability to evaluate situations more realistically. The overarching goal is for clients to independently and effectively utilize cognitive behavioral strategies across different environments, thereby improving their performance and satisfaction in activities that matter most to them.

Initial Evaluation

1. Interview

When conducting an initial evaluation, I first ask my clients, "What brings you here today?" Often, they might respond with something like, "I don’t know," or "My doctor just sent me." In these cases, I might say, "Well, I looked in your chart, and it seems like you’re having a hard time with things like eating vegetables, not sleeping well, and dealing with some anxiety. Does that sound accurate?" This usually helps them open up, and they’ll often say, "Oh, yes," which naturally leads to a discussion about their main concerns and background.

I also like to ask, "What would you like your life to look like a year from now?" If they respond with something general like, "I want to be happy," I follow up by asking, "What does happiness look like to you? Does it mean exercising every day? Does it mean being able to hang out with friends without feeling worried? What does being happy mean to you specifically?" This approach helps clients define their goals in concrete, actionable terms that can guide our work together.

2. Educating the Client and Parent/Caregiver

During the initial evaluation, it’s important to educate both the client and, if applicable, their parent or caregiver about neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to change and adapt. Until recently, it was believed that knowledge and thinking patterns were fixed, but we now understand that we can change our thinking throughout our lives. This realization is powerful, as it underscores that change is always possible. However, like building physical strength at the gym, retraining the brain requires consistent practice. You don’t get a six-pack from one gym session, and similarly, we must train our brains repeatedly to think differently.

I also take time to explain the role of occupational therapy in mental health and how it differs from talk therapy. To qualify for OT services, a client's mental or physical challenges must adversely affect their daily occupations, such as sleep, eating, exercise, or socializing. If their challenges aren’t significantly impacting their ability to engage in these activities, I often recommend talk therapy instead. Many clients see a therapist for talk therapy, work with me for OT, and engage with psychiatry. This multidisciplinary approach is often highly effective because each professional uses different strategies to address the client’s needs.

Using person-first language is another important component of my approach. For example, instead of saying someone is "an anxious person," I describe them as "a person living with anxiety." This shift in language helps separate the individual from their condition, offering freedom and empowerment to view their challenges as something they can address rather than as an intrinsic part of who they are.

I also address the concept of positive versus realistic thinking. While cultivating positivity is helpful, thinking realistically’s even more critical. We often focus on small negatives that overshadow the many meaningful and positive things we accomplish in a day. To illustrate this, I use a schema model during the initial evaluation, which visually represents how thoughts are processed.

Schema Example.

In this model, our schema represents how we perceive ourselves. Negative thoughts fit seamlessly into the schema, and because they align, we let them in without question. On the other hand, positive thoughts that don’t align with this schema are often ignored, no matter how many there are. I point out to clients that while a tiny fraction of their day—perhaps 0.01%—might be negative, it can overshadow the 99.99% of the day that went well. This lack of balance distorts reality.

Through this cognitive restructuring exercise, clients begin to recognize the disproportionate weight they assign to small negatives and learn to focus on the broader, more realistic view of their day. This exercise is particularly effective at the start of therapy because it sets the foundation for understanding and restructuring unhelpful thought patterns. By helping clients focus on realistic thinking, they can see that a couple of challenging moments don’t negate the positive experiences of an entire day.

3. Assessment Administration

Continuing with the initial evaluation, it is crucial to administer an assessment to establish a baseline of the client’s functioning. This baseline serves multiple purposes. It allows us to measure progress when we revisit the client’s outcomes at discharge, provides evidence of the medical necessity of our services, and clearly delineates the unique contributions of occupational therapy to the client’s care.

I always use an occupational performance measure, which I will discuss later, as it helps capture these elements effectively. Establishing this foundation is especially important when communicating with reimbursers. We need to demonstrate that what we are doing is valuable, effective, and distinctively aligned with occupational therapy's principles and goals.

4. Action Plan

In occupational therapy, we always create action plans for each session. For the first session, I recommend that clients get a therapy journal or notebook dedicated to their work together and bring it to each session. One of the first tasks is to start recording "credit daily," which means noting anything they do during the day that’s a little bit challenging, a lot challenging, something that went well, or even a compliment they received.

I write down a few examples with the client during the session to ensure clarity. This helps them understand exactly what I mean and sets the tone for future entries. Often, clients need cues to get started. For instance, I might ask, "Was it hard for you to come to therapy today?" If they say yes, I’ll suggest writing that down. Then I might ask, "What else have you done today?" Responses like brushing their teeth or eating breakfast are great examples, and we also write those down. This process typically becomes their first action plan as they begin treatment.

From there, we usually collaborate on one or two additional action plans, depending on what feels feasible. It’s critical that these plans are realistic and achievable because the last thing we want is for a client to return feeling overwhelmed and say, "I couldn’t get any of it done." For example, if their ultimate goal is to exercise five times a week, but they decide they want to start exercising daily, I’ll help them break it down into something more manageable. I might ask, "How many times do you think you could exercise this week?" If they say, "I think I could do two days," we’ll agree.

We then specify details: "What time will you exercise?" and "Which days will you choose?" This ensures the plan is actionable, specific, and realistic, increasing the likelihood of success. This collaborative and structured approach builds confidence and lays the foundation for meaningful progress.

5. Conclusion of Session

After the session, I review the evaluation scores with the client. Having total scores at this stage is unnecessary, but it’s helpful to give them a clear sense of where they stand. For example, with the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, where scores range from 1 to 10, a score below 5 typically indicates a need for therapy services. For other evaluations, I provide a general overview to highlight areas where therapy could be beneficial. This helps convey the message: "It looks like you would benefit from occupational therapy services."

I also take this time to educate the client about what treatment will look like. Initially, I schedule around 12 sessions. Depending on the client’s progress, this may change—we might need a few more sessions or even fewer. As we progress, sessions will taper, with the ultimate goal of empowering the client to become their own therapist by the end of our work together.

Before wrapping up, we refine the action plan to ensure it’s clear and achievable. I always strive to leave clients hopeful, emphasizing that everything they’ve shared represents challenges we can work on together. These are all areas where improvement is possible, and I assure them that progress is within reach.

Assessment

Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) is a tool I’ve used extensively in my research, and I highly recommend it. What I particularly like about the COPM is how effectively it detects changes in occupational performance and satisfaction over time. This makes it valuable for tracking progress and demonstrating to insurance companies that our interventions are making a measurable difference. It’s equally impactful for clients, as it provides a tangible way to see how far they’ve come, and it reaffirms to us as therapists that what we’re doing is effective.

The COPM can be used with individuals who are at least 8 years old mentally. It’s versatile and can be administered during the initial evaluation and reevaluation. I’ve also successfully adapted it for younger children by working closely with their parents, and I sometimes use it with parents of teens, depending on their comfort level and cognitive abilities.

The COPM assesses three main performance areas: personal care, productivity, and leisure. Within these areas, several specific tasks relate directly to pediatric practice. For self-care, this includes hygiene, sleep, eating, healthy community management, feeling comfortable in public spaces, and transitioning between locations. Productivity encompasses work and volunteerism, household management (like completing chores), play, and school-related tasks, such as time management, organization, and social play. Leisure activities are divided into quiet recreation, which involves downtime activities like managing screen use, and active recreation, such as exercise. Socialization, or how we interact with others, is also a critical area, particularly for many children and adolescents.

This tool provides a comprehensive framework for setting and tracking goals. For instance, a goal might be: "Client will independently participate in a sleep hygiene routine on four out of five trials within three months." Including specific timeframes and measurable outcomes ensures that goals align with best practices for effective therapy.

Although this information is comprehensive, I hope it serves as a useful resource for understanding how to utilize the COPM and developing meaningful, client-centered goals.

Child Occupational Self Assessment (COSA)

I also occasionally use the Child Occupational Self-Assessment (COSA), a client-directed tool designed for youth to complete independently without parent input. The COSA focuses on capturing the child’s perceptions of their occupational competence and the importance they place on various activities.

While the research-based age range for this tool is 7 to 17, it can be effectively used with children as young as 6 or young adults up to 21, depending on their cognitive and developmental level.

Typically, I will choose either the COPM or the COSA for an evaluation, though there are instances where I use both. However, I almost always include the COPM because it is exceptionally effective at demonstrating the efficacy of treatment over time, particularly when tracking changes in occupational performance and satisfaction. This makes it a valuable tool for clinical practice and communication with stakeholders like parents, caregivers, and insurance providers.

The Cleveland Adolescent Sleepiness Questionnaire (CASQ)

This assessment is relatively new to me, but I came across it and found it intriguing enough to reach out to the author for permission to use it. It measures excessive daytime sleepiness in adolescents and can be administered as a pre-and post-treatment assessment. This makes it a valuable tool for tracking changes and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions to improve sleep hygiene and related functional outcomes.

Beck Youth Inventories, Second Edition (BYI-2)

The Beck Youth Inventories include five different self-report inventories, and I typically select one to three of these based on the time available and the client’s specific areas of concern. The ones I use most often are the depression, anxiety, and self-concept inventories, as they align closely with many of the challenges clients present with.

These inventories are designed for individuals aged 7 to 17 and can be utilized as pre- and post-treatment assessments. This dual application provides valuable insight into the client’s progress and helps demonstrate measurable outcomes to the client, the therapy team, and reimbursers, further validating the efficacy of our interventions.

Coding and Billing

Commonly Used CPT® Codes

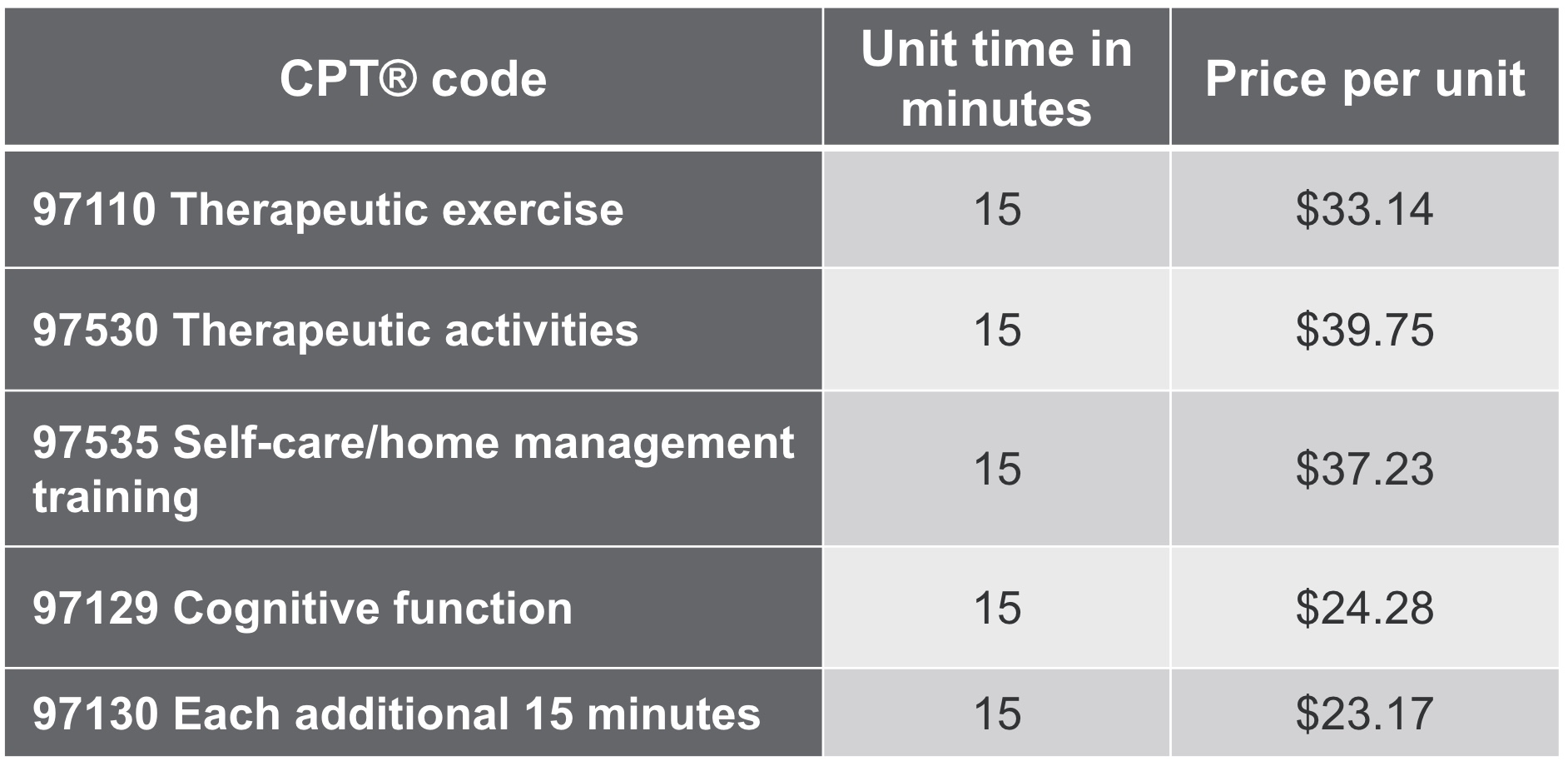

CPT codes are essential to address because they are crucial in ensuring our practice is financially sustainable. Figuring out which codes to use for outpatient mental health services with an occupational focus took some experimentation on my part. I had to navigate this independently without much guidance, trying different approaches to determine what worked best. Over time, I identified codes reimbursable for these types of services, which has been key to maintaining the financial viability of my practice.

The codes I currently use are based on the 2023 pricing per unit through my hospital’s charge master at the time (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Charge codes from 2023 from the author's hospital's charge master.

However, this landscape is always evolving. Reimbursement rates can change frequently, which makes it essential to stay informed and adaptable. I’m also actively working to get some behavioral codes implemented at my hospital, which could further enhance our ability to bill for mental health-focused services. These new codes are promising and may soon become part of my billing repertoire, which is exciting.

Staying current on changes in CPT codes and reimbursement policies is critical. It ensures that our services remain financially viable while continuing to align with best practices in occupational therapy.

Frequently Used Referring Diagnosis and Treatment Codes

These are frequently used referring and diagnosis treatment codes.

- R41.844 Frontal lobe and executive function deficit: Cognitive deficit in executive function

- F89 Unspecified disorders of psychological development (<18 years old only)

- R41.840 Attention and concentration deficit: Cognitive deficit in attention or concentration.

- R44.9 Unspecified general sensations and perceptions or R20.8 Disturbance of skin sensation

- R53.83 Other fatigue

In my practice, the two most common referring diagnoses I see are executive functioning deficits and disorders of psychological development. These are broad umbrella terms that encompass most of the referrals I receive.

I also often see referrals for attention and concentration deficits and unspecified general sensations and perceptions or disturbances of skin sensations—essentially, issues related to sensory processing. Additionally, I receive referrals for fatigue, particularly when sleep difficulties are a significant factor.

It’s worth noting that my referrals weren’t always like this. When I first started, I received many referrals for anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression. However, these diagnoses don’t always indicate an occupational deficit. As we’ve discussed before, just because someone isn’t feeling their best doesn’t necessarily mean they’re having difficulty engaging in daily activities.

The referrals I focus on now often highlight more specific occupational challenges. These include difficulties with emotional regulation, higher-level executive functioning, and normal psychological development. Clients may also struggle with attention, environmental cue processing, or fatigue—all of which directly impact their ability to perform and participate in meaningful occupations.

Intervention

Session Structure Elements

Here are the session structure elements.

- Mood check-in

- Review of the past week

- Agenda setting

- Specific interventions (therapeutic, cognitive, self-care)

- Develop an action plan for the upcoming week

- Elicit feedback

Each session begins with a mood check-in. I typically start by asking, "How are you feeling today?" and, at times, we might incorporate an inventory to help them articulate their mood. Afterward, we review the past week. If the client starts with something negative, that’s okay, but I always ask, "What are some positive things that happened this week?" This helps reinforce the cognitive restructuring process, encouraging them to focus on their achievements and what they are doing well rather than solely on what might be going wrong.

Next, we set the agenda for the session. I ask, "What would you like my help with today? What do you want to work on?" This allows us to collaboratively determine the session's focus and prioritize specific interventions that address their needs.

Our interventions include therapeutic cognitive and self-care strategies tailored to their goals. We also develop an action plan for the upcoming week, ensuring it is practical and achievable.

Finally, I elicit feedback to wrap up the session. I’ll ask questions like, "How did you feel about the session today? What can we do to improve it next time? Is there anything you’d like me to add to our agenda for the next session?" This feedback helps refine the therapeutic process and ensures the client feels heard and actively involved in their progress.

Intervention Examples

These are some examples of interventions I use.

- Emotion-based games

- Breathing beads

- Worry jar

- Roleplay

- Mindfulness

- Arts and crafts

- Yoga

- Desensitization/ exposure

- Activity scheduling

- Mental imagery

- Journaling “credit”

Emotion-based games are a great tool, and there are many free PDF downloads available online for activities like "breathing beads" or the "worry jar." These tools help teach emotional regulation and can be adapted to different age groups. For mindfulness, plenty of online scripts are available that are tailored to specific age ranges, making it easier to select the most appropriate one for each client.

Arts and crafts are another excellent option, providing an enjoyable activity where clients can feel successful. These creative tasks are especially useful for building self-esteem and fostering a sense of accomplishment. Similarly, introducing exercise routines, such as yoga or relaxation techniques, helps clients learn to regulate their emotions and manage stress effectively.

Desensitization exposure involves structured, small experiments to gradually help clients face their fears. For example, if a child fears being in public, we might start with an experiment where they go to a gas station to buy something independently. Once they feel comfortable, we can progress to more challenging situations like going to a grocery store alone. These experiments become increasingly complex as their confidence builds.

Activity scheduling focuses on improving time management skills, while mental imagery involves envisioning success and preparing for positive outcomes. Lastly, journaling credit—writing down daily achievements, no matter how small—reinforces a sense of progress and helps clients focus on what they are doing well. All these strategies work together to support emotional and functional growth in a structured and engaging way.

Intervention Items

This is what a worry jar might look like in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Example of a worry jar.

This is just an old wipes container from my work. You can really use any kind of jar, big or small. The client writes down on a little piece of paper what their worry is. Let's say it's an upcoming test. They crumple it up and put it in the jar.

Once it's in the jar, they can no longer worry about it. If it comes up later, that's okay, but they must write it down and put it back in there. Alternatively, for teenagers, we can do something called worry time. We schedule five minutes daily for them to worry their hearts out. And outside of that five minutes, they're no longer allowed to think about it.

If they have some worries that come up, that's okay. They can write those down, but they can't worry about them until their next scheduled worry time. You also want to ensure this worrying time is far from bedtime, so it's not keeping them up at night. This allows us to confront our worries and what we're anxious about, but it also gives it boundaries so it doesn't ruin our whole day.

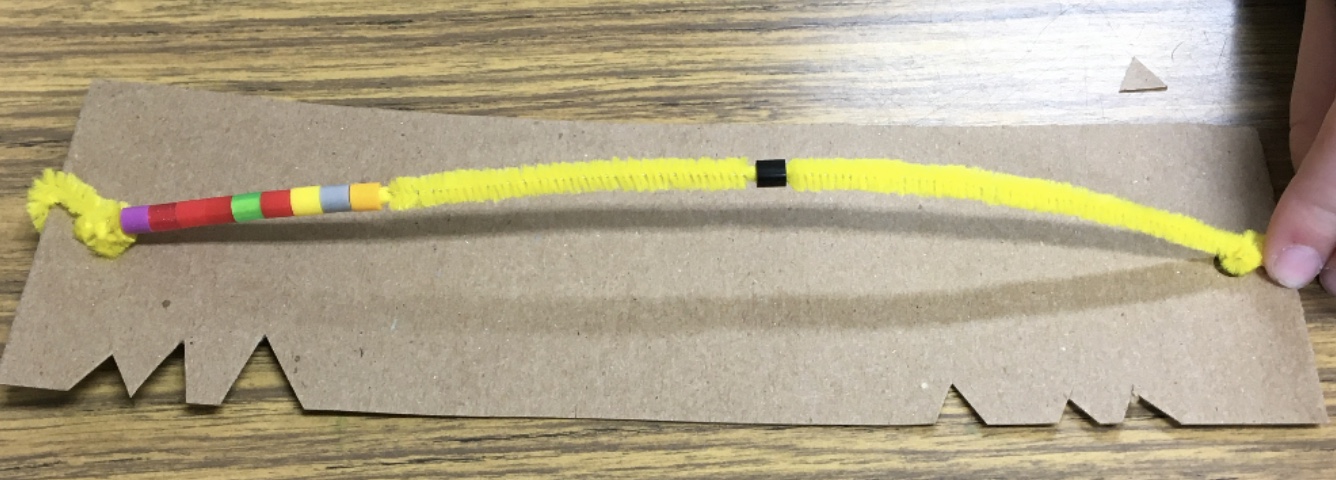

Breathing beads are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Example of breathing beads.

Here's how the breathing beads technique works: the client takes a bead and, while breathing in, moves it all the way across the string. Then, they take the next bead and, while breathing out, move it across as well. They repeat this process, bead by bead, focusing on their breath and the movement until they feel calm. This simple yet effective tool helps clients regulate their breathing, focus their attention, and achieve a state of relaxation.

Worksheets and Handouts

I often use a variety of worksheets and handouts during sessions (included in the handouts).

- Tips for Realistic Thinking and How to Take Action worksheet

- Identifying Unhelpful Thoughts worksheet

- Sleep Hygiene handout

- Outcomes Tracking worksheet

- Thoughtful Questions for Unhelpful Thoughts worksheet

- Facts For and Against worksheet

- Thought Cascade worksheet

Tips for Realistic Thinking and How to Take Action. The first worksheet, Tips for Realistic Thinking and How to Take Action, offers strategies designed to help kids address various challenges. One key concept is understanding that just because we think something doesn’t mean it’s true. Thoughts are not facts, and it’s important to evaluate whether there’s any evidence behind them. The goal isn’t to replace negative thoughts with purely positive ones but to shift toward realistic thinking.

Journaling is a central strategy in this worksheet, where clients record things they did that were a little hard or that they’re proud of. It’s crucial that they don’t journal things that didn’t go well. Sometimes kids will write down things they didn’t complete, but focusing on what they didn’t accomplish is unhelpful, especially when they’re already experts at self-criticism. The aim is to highlight successes and progress, no matter how small.

Another strategy involves rating worries on a scale from 1 to 10. For instance, if a child is nervous about entering a gas station, they might rate their fear as a 5 out of 10 beforehand. After completing the task and realizing it wasn’t as scary as anticipated, they might rate it a 0. This provides tangible evidence of progress, and they can journal how it went to reinforce the experience: “I went in, got my candy bar, and came back out. I was okay.”

As discussed earlier, the worksheet also includes other strategies, such as using a worry jar or worry time and tackling school assignments effectively. I always recommend a paper planner for tracking assignments, as it reduces overwhelm and improves memory retention. Completing the most difficult assignments first and learning to ask for help are also valuable skills.

Sensory strategies to improve attention include heavy work, reducing clutter, using earplugs, and taking regular breaks. Another effective approach is to break chores into smaller, manageable tasks. For example, the client might focus on the closet or the dresser instead of cleaning a messy room. This helps reduce overwhelm and maintain motivation.

For kids who struggle with ADHD and time perception, estimating task durations and then timing them can be an eye-opener. If they think cleaning their room will take two hours but discover it only takes 27 minutes, it reframes the task as less daunting and helps them plan better.

Other practical tips include preparing healthy snacks and meals at the start of the week to ensure access to nutritious options. For exercise, I work with many clients in rural areas where affordability can be a barrier. I often recommend thrift stores as a budget-friendly exercise clothing and gear option. Sharing personal experiences, like how I shop at thrift stores, helps make the idea relatable and approachable, empowering clients to start building healthier habits in accessible ways.

Identifying Unhelpful Thoughts. These concepts address common cognitive distortions that often lead to unhelpful thinking patterns. One example is all-or-nothing thinking, which is very black and white—for instance, "I have to get straight A’s or it’s not worth trying." This type of thinking overlooks the value of effort and progress. Another is fortune-telling, where someone assumes a negative outcome in the future despite evidence to the contrary, such as thinking, "I’m going to fail this test," even if they’ve never failed before.

Labeling is another distortion, where someone defines themselves negatively based on a single event, such as believing, "I’m a bad person for forgetting my friend’s birthday," when it’s just one oversight. Emotional reasoning involves assuming feelings are facts, such as, "I feel like they’re judging me, so they must be." In reality, feelings are not evidence, and thoughts are not facts.

Selective abstraction focuses only on part of a situation while ignoring the rest. For example, a student might dwell on a bad grade while dismissing all the good grades they earned in the same class. Overgeneralizing furthers this, such as concluding, "Because I got one F, I’m a bad student."

Mind reading assumes we know what others think, like, "I know they’re thinking I don’t look good in my clothes," when there’s no evidence to support that. Taking things personally is another distortion, like assuming, "They didn’t text me back, so they must not like me," rather than considering they might just be busy or distracted.

Imperatives like "I should have done this yesterday" or "I should be doing this now" are often self-defeating because they focus on unattainable past actions or unrealistic present expectations. Magnification and minimization involve overemphasizing negatives while downplaying positives, which is why tracking "credit" is important—it shifts this balance and reinforces positive thinking.

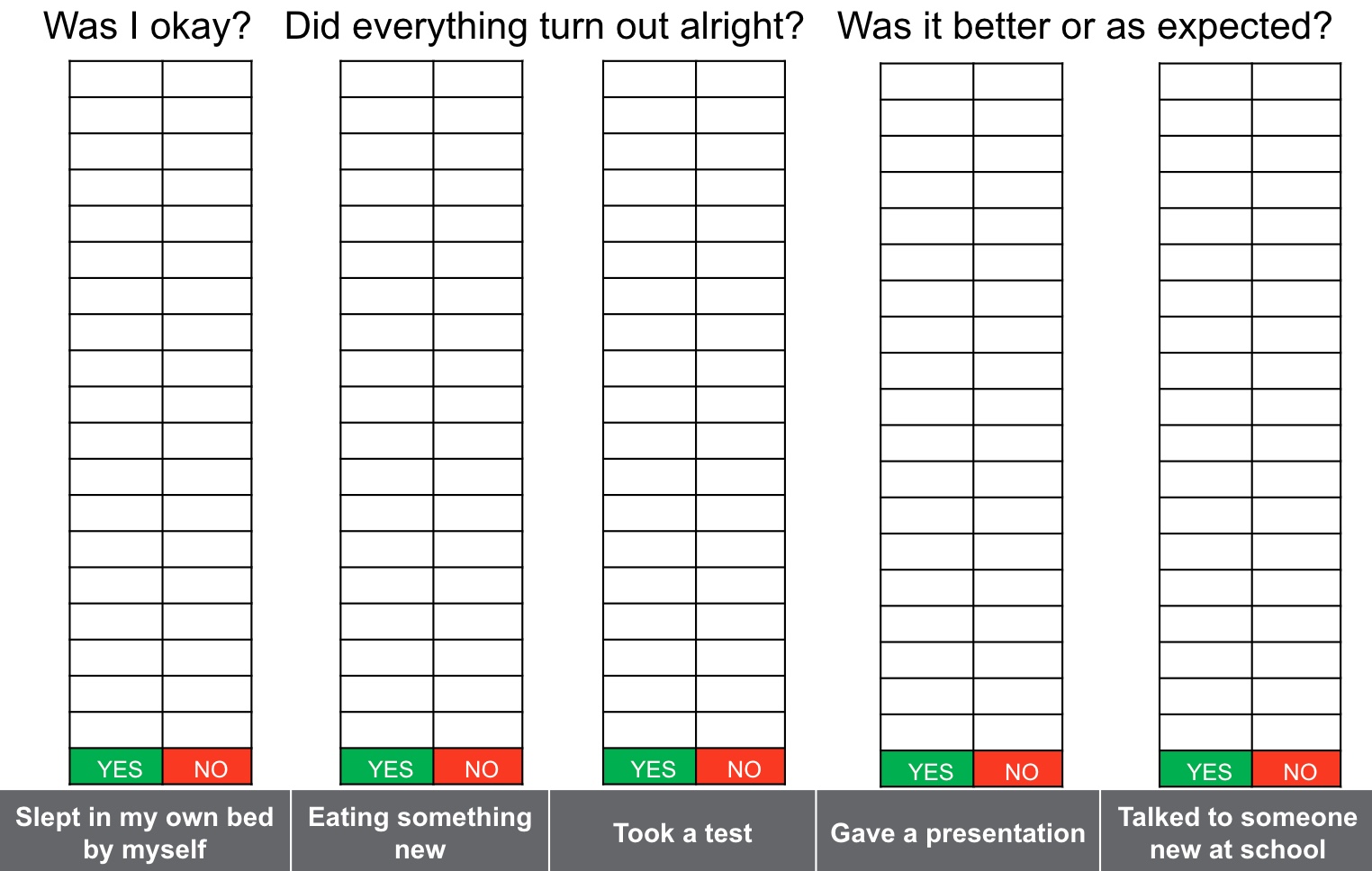

One helpful tool to counter these distortions is the outcomes worksheet in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Outcomes worksheet. Click here to enlarge the image.

With this, clients list activities they’re worried about at the bottom of the sheet, such as taking a test or attending a social event. After participating in the activity, they mark whether the outcome was okay, better than expected, or as expected. Over time, this builds a visual record showing that things turn out fine, often better than anticipated. By consistently building evidence, clients move from hoping they’ll be okay to knowing they’ll be okay, supported by a clear pattern of success.

Thoughtful Questions for Unhelpful Thoughts. When thinking about problem-solving, it’s helpful to ask, What’s the worst thing that could happen? Let’s use an example of talking to someone new. The worst-case scenario might be that they ignore us or say something mean. If that happened, what would you do? Likely, you’d walk away. You might feel bad for a little while, but you’ll recover. Most of us have had less-than-ideal interactions with people before, and we’ve moved past them.

Next, consider What’s the best thing that could happen? In this example, the best outcome might be that you become friends. And the most realistic outcome? You’d likely have a decent back-and-forth conversation, which could be a positive interaction, even if it doesn’t lead to friendship.

To challenge unhelpful thoughts, we also look at the evidence. For instance, if you think, "People don’t like me," we’d ask, "What’s the evidence that this thought is true? Can we prove it?" Often, there’s no real evidence to support the thought. What’s another way we could look at the situation? For example, if someone doesn’t text back, instead of assuming, "They must not like me," we could consider, "Maybe they’re busy or forgot."

Next, think about how these unhelpful thoughts make you feel. For instance, believing People don’t like me likely makes you feel down or unmotivated. Now imagine replacing that thought with People do like me. How would that make you feel? Probably much better, and it would encourage more positive actions.

It’s also important to examine how unhelpful thoughts affect your daily life and what they prevent you from doing. For example, such thoughts might prevent you from meeting new people or making friends. Changing your thinking can make you feel more confident about stepping outside your comfort zone, initiating conversations, and engaging with others.

Finally, it’s helpful to take an outside perspective and ask, What would I tell a friend in the same situation? Often, we’re much kinder and more understanding to others than we are to ourselves. This shift in perspective can make it easier to adopt a more realistic and compassionate approach to our own challenges.

Let's Practice

Facts For and Against Helpful Thought Table

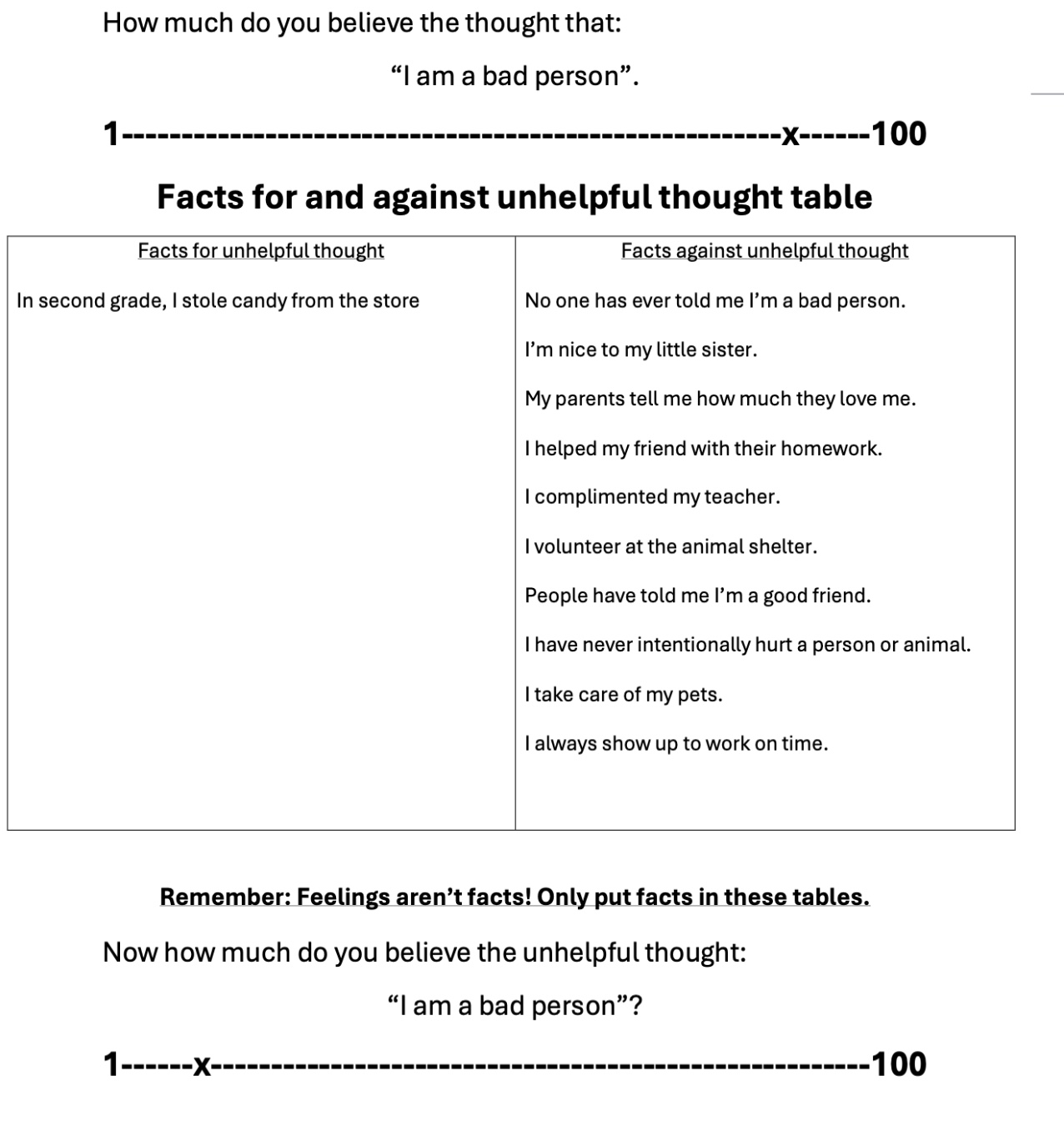

Figure 7 shows the Facts For and Against Helpful Thought Table handout.

Figure 7. Facts For and Against Helpful Thought Table handout. Click here to enlarge the image.

Let’s work with the unhelpful thought, I’m a bad person. First, ask the client to rate their belief on a scale from 1 to 100. In this case, let’s say their belief is close to 100.

Start by listing the Facts for the unhelpful thought. In this example, the client might recall stealing candy in second grade. However, now they’re 15, and no other instances exist to support this thought. It’s crucial to fully explore this column before moving to the Facts against side.

When listing Facts against the unhelpful thought, you may need to cue the client. Together, you can build a much longer list of reasons why the thought isn’t true—such as their kindness toward friends, good grades, or positive actions they’ve taken recently. This process often highlights a significant imbalance, where the Facts against greatly outweigh the Facts for.

Remind the client that feelings aren’t facts, so they don’t belong in the table. For example, "I feel like I’m a bad person" doesn’t qualify as evidence. Once the table is complete, ask them to re-rate their belief in the unhelpful thought. Typically, this number will drop significantly after completing the exercise.

Take a moment to think of an unhelpful thought that you or a client has had and map it out using this approach. This exercise helps reinforce the importance of evaluating thoughts critically and recognizing the weight of evidence against unhelpful beliefs.

The Thought Cascade Handout

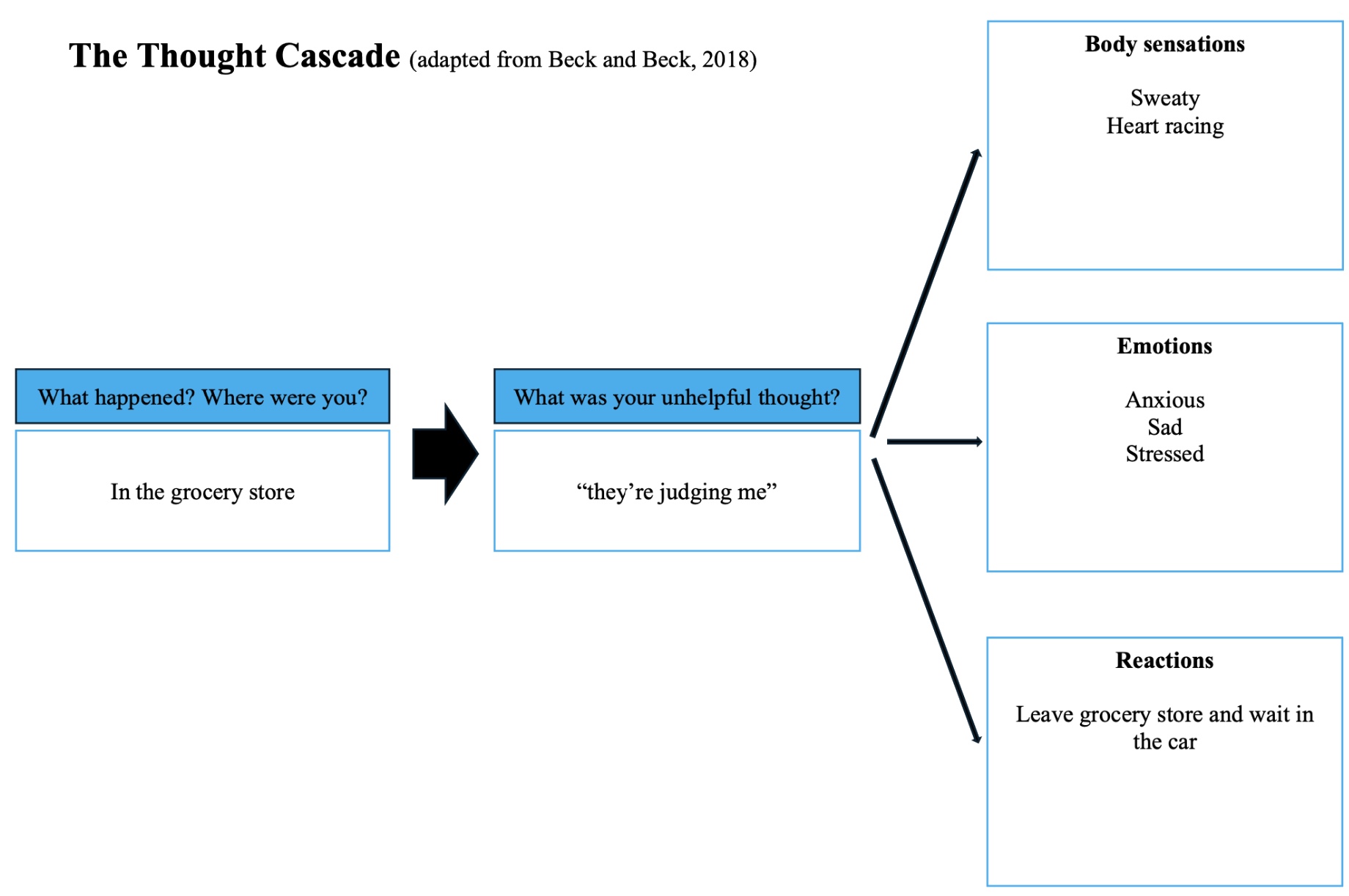

Figure 8 shows another worksheet that I thought we could practice.

Figure 8. The Thought Cascade handout. Click here to enlarge the image.

In this exercise, we’re focusing on breaking down a scenario into its components: the situation, the unhelpful thought, the resulting body sensations, emotions, and reactions. If you don’t have the worksheet, you can create a simple diagram on paper to map this out.

Let’s use the example of someone going to the grocery store. The situation is straightforward—they’re at the store. Their automatic unhelpful thought is, They’re judging me. This thought triggers body sensations like sweating and a racing heart and emotions such as anxiety, sadness, and stress. These feelings lead to a reaction—they leave the store and wait in the car, even though they enjoy grocery shopping and picking out snacks they like.

Take about 30 seconds to think of a scenario involving an unhelpful thought, either from your experience or a client’s, and write down the cascade of sensations, emotions, and reactions. This exercise helps illustrate how unhelpful thoughts can escalate into physical and emotional discomfort and affect behavior, laying the groundwork for exploring more helpful, realistic thoughts in future exercises.

Case Study

In this case study, we have an 11-year-old who is scared to sleep in their bed alone. They are a picky eater and are scared to try new foods because of past stomach problems. They have difficulty completing their chores and struggling with time management and organization, leading to poor grades. They are also scared to be without their parents, even in public, and cannot tolerate being out of view. Additionally, they are experiencing bullying at school and are excessively worried. This is an example of a typical treatment session or progression I might work through with a client.

Diagnosis Codes

Here are the diagnostic codes.

Referring diagnosis:

F89 Unspecified disorder of psychological development

Tx diagnosis:

F89 Unspecified disorder of psychological development

R41.844 Frontal lobe and executive function deficit

Alternative Tx diagnosis:

R53.83 Other fatigue

R44.9 Unspecified general sensations and perceptions

The referring diagnosis code was the F89, the unspecified disorder of psychological development. My treatment diagnosis codes are F89 and then the executive functioning deficit. Alternatively, I could also use other fatigue because they are having a hard time with sleep or unspecified general sensations and perceptions because they have these physiological reactions to their stress.

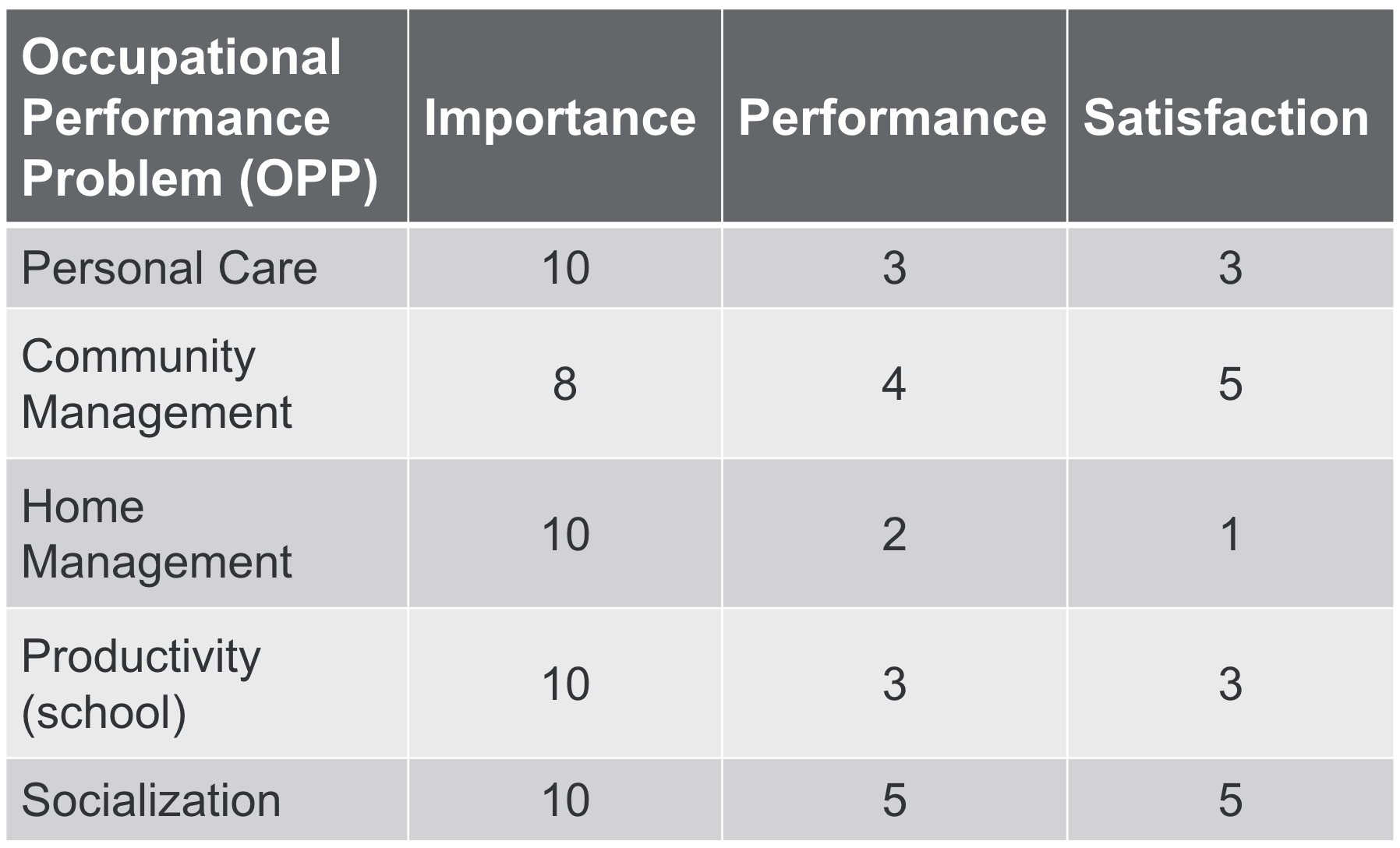

COPM Assessment Results

Here are their COPM assessment results in Figure 9. Again, they are rated on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 being the most important.

Figure 9. COPM assessment results.

In this case, the scoring system helps gauge performance and satisfaction levels, where a 10 indicates performing a task with no problem, and satisfaction means being completely happy with the performance. For this client, most areas—such as personal care (healthy eating and sleep), community management (fear of being away from their parents), home management (completing chores), and time management (school performance)—ranked high in importance. However, their performance and satisfaction scores in these areas were generally low.

The client is particularly dissatisfied with their sleep and eating habits. They feel somewhat neutral about how they handle being away from their parents in public spaces but are notably unhappy about their inability to keep their room clean and their struggles with school performance. While they feel okay about socialization because they have friends, bullying remains a significant concern.

When reporting these scores in an evaluation report for insurance, I include relevant information but leave out references to school-related challenges. For example, while the struggles with time management and organization are noted, I avoid explicitly tying them to "school" in the report. This is because insurance companies may reject claims if they perceive the issue as something that should be addressed in school. They often don’t understand that these services are typically not offered in schools and that the qualifying criteria for school-based services differ significantly from outpatient services. This distinction ensures the report is more likely to be approved while still addressing the client’s needs effectively.

Other Assessment Results

Here are the other assessment results.

CASQ

65/80 (higher score indicates sleepier)

Beck Anxiety Inventory-Youth

T-score=66 (Moderate anxiety)

Beck Self Concept Inventory-Youth

T-score=39 (Much lower than average)

The client’s CASQ score (Cleveland Adolescent Sleepiness Questionnaire) was 65 out of 80, indicating significant daytime sleepiness. Their anxiety inventory revealed moderate anxiety levels, while their self-concept score was much lower than average, suggesting challenges with self-esteem and how they perceive themselves. These results provide valuable insight into the client's struggles and help guide targeted interventions.

Goals: Short Term

Client will sleep in own bed for duration of night I’ly without complaint on 4/5 trials.

Client will tolerate licking new/nonpreferred foods with min aversion I’ly on 4/5 trials.

Client will participate in community mgmt. tasks without emotional lability I’ly on 4/5 trials.

Client will identify and use at least 3 organizational/time management strategies to use across environments to improve productivity I’ly on 4/5 trials.

Client will use reciprocity strategies to improve success with socialization I’ly on 4/5 trials.

Client will identify and use at least 3 coping strategies to calm self when overwhelmed across environments I’ly on 4/5 trials.

Client will participate in a weekly home program (action plan) with at least 80% compliance with min A on 4/5 trials.

The short-term goals for this client include several specific and measurable targets. They aim to sleep in their own bed independently for the duration of the night without complaint in four out of five trials. They will tolerate licking new or non-preferred foods with minimal aversion and participate in community management tasks without emotional lability. Additional goals involve identifying executive functioning strategies to improve productivity, learning successful reciprocity strategies for navigating uncomfortable social situations and identifying and using at least three coping strategies to calm themselves.

I also always include a weekly home program with an 80% compliance goal to ensure clients consistently practice what we work on during sessions. This is critical because, without regular follow-through, it becomes much harder to make meaningful progress. In an outpatient mental health setting, clients need to be ready to take action and make changes. This readiness is essential, and the home program goal reflects the importance of their active participation between sessions.

Goals: Long Term

Client will improve score on the COPM by at least 2 points on average for Performance and Satisfaction demonstrating clinically significant improvement in important occupations in 6 months.

Client will chew and swallow new/nonpreferred foods without aversion independently on 4/5 trials in 6 months.

The long-term goals are that they'll improve their score on the COPM by at least two points, demonstrate improvement in performance and satisfaction and meaningful occupations, and be able to try new foods without aversion.

Cognitive Restructuring Interventions

Journaling “credit”

Thoughtful Questions worksheet

Thought Cascade worksheet

Facts For and Against Chart

Experiments (i.e, different aisle in grocery store)

Tips for realistic thinking and How to Take Action handout

Outcomes Tracking sheet

The interventions used with this patient included several targeted strategies to address their specific challenges. We utilized the Journaling Credit activity to help them recognize and record their accomplishments, even small ones. We incorporated thoughtful questions to guide reflection and self-awareness and the Thought Cascade and Facts For and Against worksheets to help challenge and reframe unhelpful thoughts.

Experiments were another key intervention, such as having the client walk down a different aisle from their parent and meet at the end. This helped build their confidence and independence in a gradual, controlled manner. The Tips for Realistic Thinking and How to Take Action handout provided them with concrete strategies to navigate difficult situations, and the Outcomes Tracking worksheet was used to document and visualize their progress, reinforcing positive outcomes and building evidence for realistic thinking. These interventions were selected to create a comprehensive and supportive approach to the client's goals.

Occupational and Coping Strategy Interventions

Color coding subject folders/materials

Trying new foods

Sleep hygiene

Worry jar

Coloring, painting

Rating worry before and after

Timing tasks

To do lists

Paper planner

Chore chart

Role play to prepare to talk to bully or make a new friend

Color-coding subject folders and materials is a great strategy to help clients with organization. For trying new foods, using the Outcomes Tracking Worksheet can help clients record and reflect on their progress. For example, if a client is nervous about trying a new food and rates their anxiety as 8 out of 10 before the session, they might find their anxiety drops to 0 out of 10 afterward. They can then note this success on the worksheet, building evidence that trying new foods can be safe and manageable.

Games like Zufari or Candyland can make trying new foods more engaging. Assigning each game color to a different food introduces an element of fun, and having a safe space and something familiar they enjoy alongside the new food can help them feel comfortable.

For sleep hygiene, a gradual desensitization approach can be helpful. Starting with the child sleeping on a cot or mat near their parents’ bedroom, they progressively move farther away until they’re sleeping comfortably in their own bed. Again, tracking worry levels before and after can show them that nothing bad happens when they sleep alone. Asking for evidence of potential dangers—such as, “Do you know anyone who’s had something bad happen at night?”—helps them challenge these fears logically.

The worry jar can be a helpful tool for externalizing fears. Activities like coloring and painting are also effective for boosting self-esteem while tracking worry levels before and after the session reinforces their sense of accomplishment.

Timing tasks and creating to-do lists are great strategies for improving time management. Reviewing these lists daily helps clients stay organized and remember what they need to accomplish. Similarly, creating chore charts, either handmade or store-bought, allows clients to take ownership of their responsibilities and gives them a clear visual of their progress.

Role-playing is an essential intervention for managing bullying or making new friends. For bullying, clients are encouraged to identify something they admire about the bully, such as their style or a skill they excel at, like baseball. Role-playing scenarios might include complimenting the bully’s shirt or asking for tips on pitching. This approach teaches kids to handle conflict positively and constructively, often resulting in the bully either backing off or forming a friendship.

For making new friends, encourage the client to identify the nicest person in the class and think of a genuine compliment or interest to start a conversation. For example, if a classmate makes jewelry, they might ask, “Could you teach me how to make jewelry sometime?” This fosters connection and builds social confidence, helping them establish new relationships.

Soap Note Example

This is a soap note example.

S: Pt was willing to participate in therapy today. Pt was able to complete 2/3 action plan components I’ly.

O: Self-regulation, socialization, feeding, action plan.

A: Pt tolerated therapy well. Completed “worry jar” craft to use when overwhelmed and return demonstrated use of jar. Tolerated chewing and swallowing 1 small bite of new/nonpreferred foods with vision occluded with min aversion on 3/5 trials. Recorded result of trying each food on outcomes tracking sheet to use as coping strategy. Role played peer scenario to improve reciprocity and made plan to implement peer interaction tomorrow.

P: Continue with plan of care.

This may seem like a lot of information, but I wanted to provide an example that you can reference if you decide to implement cognitive behavioral strategies in your outpatient setting. Since we all write SOAP notes differently, this example reflects the format I use in my practice, which I’ve found reimbursable through insurance. You’ll notice that the note avoids including personal information unrelated to occupational performance. For instance, something like “my boyfriend broke up with me today” wouldn’t be included because it’s irrelevant to the client’s functional progress and doesn’t demonstrate improvement in targeted areas.

Including such personal details is inappropriate for a chart that others might review in the client’s care. Instead, keep those details in separate paper notes or a private chart to guide conversations in future sessions. However, your SOAP note should remain focused on occupational performance, ensuring it outlines the areas being worked on and the progress being made. This focus not only maintains professional boundaries but also strengthens the documentation for insurance purposes by emphasizing measurable, goal-oriented outcomes.

Treatment Progression

The treatment progression in this scenario consisted of 10 sessions, scheduled once a week for 45 minutes each. Starting at session eight, we began tapering the sessions every other week for the remaining time. During the off weeks, the client participated in a self-therapy session.

A self-therapy session involves the client setting aside a specific time—perhaps right after school on Mondays—to engage in their own structured therapeutic process. During this time, they review their goals from the previous week, reflect on their journal entries highlighting accomplishments and evidence of progress, and create an action plan for the upcoming week. This approach helps reinforce self-efficacy and ensures continuity in their therapeutic work even when sessions are less frequent, fostering independence and long-term success.

Discharge Session

In the discharge session, we re-administered all of the initial assessments, and I scored these during the session. These assessments are relatively easy to score in real-time, which is important because this is the final session, and we won’t have another opportunity to review the results with the client. Scoring in-session shows the client the progress they’ve made immediately. We also revisit their goals, which, along with the assessment scores, clearly highlight how far they’ve come.

Occasionally, a client might initially express uncertainty about whether they feel much better, though this is rare. When this happens, reviewing their scores can be incredibly impactful. Seeing the objective progress they’ve made often leads to a moment of realization, where they say, “Oh, my gosh, I’ve made huge gains.” This is an empowering experience for the client, helping them truly see and appreciate their growth.

Ending therapy this way fosters a sense of hope and confidence, emphasizing how far they’ve come and reinforcing their ability to continue making progress on their own. It’s also a valuable moment for the therapist, as it underscores the effectiveness of the intervention and provides a satisfying conclusion to the therapeutic process.

Discharge Home Programming

Creating a home maintenance program at discharge is crucial to ensure the client maintains the progress they’ve made and continues to grow. For the discharge home program, I always have the client record the plan in their journal. We start by noting the date and then reviewing all the notes I’ve taken throughout therapy. Together, we identify the strategies and tools that worked best for them, and they write them down in one place for easy access. Even though they’ll be reviewing their journal regularly, having everything summarized ensures they won’t need to search through pages to find what they need.

The home maintenance program includes continuing with their journaling, holding a weekly self-therapy session, and regularly reviewing their journal and the tools that have been most effective for them. We also discuss how they can get a future referral if needed. I emphasize that just because therapy is concluding today doesn’t mean they can’t come back if circumstances change. If they find themselves struggling again, they can return with a new referral, ensuring they have ongoing support when needed.

Summary

Exam Poll

1)What is a foundational component of integrating Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) into Occupational Therapy (OT)?

The answer is C emphasizing the use of adaptive behaviors.

2)During the initial evaluation in the Cognitive Behavioral Frame of Reference (CB-FoR), what is a key action step?

Okay, great job, everyone. The answer is B. Teaching the client about neuroplasticity and OT role.

3)Which assessment tool is designed specifically for youth to self-assess their occupational competence?

It's B. The Child Occupational Self Assessment.

4)Which intervention is recommended to improve realistic thinking?

Great job. B journaling successes and reviewing them nightly.

5)What is a short-term goal for a client using the CB-FoR?

The answer is B.

Questions and Answers

What should be done if Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) does not cover cognitive billing codes?

A: It’s common for cognitive billing codes not to reimburse well. In such cases, I recommend billing under self-care codes, which fall under a broad umbrella that includes home management and related activities. Most of what we do in occupational therapy can relate to self-care, so these codes can be a viable alternative. Additionally, behavioral codes are emerging, and I’m currently working to implement them at my hospital to see if they’re reimbursable. The billing landscape is always changing, so staying updated on coverage and adjusting as needed is critical.

Do you have specific tools or data sheets for tracking home program compliance, or do you rely on client self-reporting?

A: I rely on the action plans we write together in session. We review each action plan during follow-ups to see how many were completed. For example, if there were three action plans, we determine whether they completed two or three out of three and calculate a percentage for compliance.

How do you engage teen clients who may not be ready to address negative thought patterns?

A: I am honest with clients upfront, explaining that progress depends on their willingness to make changes. If clients feel their performance and satisfaction are fine, as reflected in tools like the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, and they express no desire to make changes, occupational therapy may not be appropriate for them. I encourage them to return when ready to engage in the process.

Does a practicing OTP need supervision from a psychologist to implement cognitive behavioral strategies?

A: No, OTPs can practice these strategies independently as long as they receive proper training. I completed the Beck training series, including modules on anxiety, depression, essentials, children, and perinatal mood disorders. These trainings provided excellent guidance on implementing cognitive behavioral strategies. While I had assistance from a psychologist to create an email template for referrals when starting this service line, OTPs are fully capable of implementing these techniques independently with the right preparation.

How do you determine the boundary between occupational therapy and psychological services, and when is a referral to psychology more appropriate?

A: The boundary often depends on the client’s needs and readiness for action-based therapy. If a client scores high on the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (e.g., above six) and primarily wants to discuss their concerns, I may refer them to psychology. For cases like trauma, where I’m not trained in specific psychological treatments, I refer to psychology while continuing to provide skills-based therapy within my scope. Sometimes, I refer to both OT and psychology for a comprehensive approach.

References

Please refer to the additional handout.

Citation

Jones, M. (2025). Implementing the cognitive behavioral frame of reference In outpatient care for youth with mental health conditions. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5765. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com