Introduction

This is a topic that I feel is important to our profession, and I like talking about it. What I want to convey is that you should care about this topic too. I work in academia course, and obviously, I use information literacy skills. However, I also spend time in clinical practice, and I know that these skills bridge to clinical practice.

To start, I want you to think about what tools you use in practice? What are your favorite therapy tools? Some of you may say adaptive equipment like reachers. I think reachers are fantastic. If you work in pediatrics, you may say Play-doh. In contrast, another may say a deck of cards. For me, I know shaving cream is an intervention that I have used from pediatrics through the lifespan. You can always find something to do with shaving cream.

There are many tools that we have in our therapeutic toolbox. What I am going to guarantee is that you use information literacy skills in practice every day. And if you do not use them every day, you use things you have learned previously by utilizing information literacy skills. Throughout the presentation, I will connect this idea of these information literacy skills to how it is seen and used in everyday practice.

Why Do OTs Need Information?

- I think ______ is true. Now what?

- Sensory rooms can be used to treat addiction.

- OT is important in the treatment of vets with blast-related TBI.

- Virtual reality can help with stroke recovery.

- There should be "sensory-friendly" community events.

- You can treat Boutonniere deformity with serial casting.

- Animal-assisted therapy has a place in skilled nursing facilities.

- Information literacy skills are important to occupational therapy practitioners.

To start connecting information literacy to occupational therapy, let's think about why occupational therapy practitioners need information daily. Typically, it is because of one of three reasons. You think you know something is true, but you need a little bit of evidence to back it up. You need somebody else to believe this as well, or you do not know the answer to something and have to find out that answer. And sometimes, you have limited information and then need to fill some gaps in with some more information.

Here are some examples of things that people have told me or that I have personally experienced. We know that there are sensory rooms for people who have sensory processing disorders, and these can be really effective in treating that type of condition. There are also some ideas that sensory rooms could be used to treat addiction. We think this is true, but we need to connect the dots.

Another one of my students was interested in looking at the treatment of veterans with blast-related traumatic brain injury. What is the best occupational therapy treatment that would work for this population?

I think using virtual reality for stroke recovery is really interesting. Does it work? Is this something that we can start using at our rehab or skilled nursing facilities?

If you are working with families/caregivers, what sensory-friendly community events are available?

This was one from my experience in hand therapy. I had a patient come in with a script from her doctor for a Boutonniere deformity. The treatment was serial casting. I needed more information on this topic to use this treatment. We will dive deeper into this a little later.

Here is an example from one of my colleagues that we will also revisit later. She believed that animal-assisted therapy should have a place and is really beneficial in skilled nursing facilities.

What are the steps of information literacy to help in these scenarios? Information literacy skills are important to occupational therapy practitioners.

Definitions

- Information Literacy

- Ability to know when information is needed & have the ability to locate, evaluate, and effectively use it (ALA, 2021)

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Ability to use the current best information, or evidence, to make a decision in caring for consumers (AOTA, 2021)

- Health Literacy

- Ability for consumers to understand medical/clinical information given to them or searched for by them and use this information to make good health decisions (CDC, 2020)

I think it is helpful to look at some definitions. What is information literacy? According to the American Library Association, information literacy is the ability to know when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and effectively use it.

We are probably more familiar with the definition of evidence-based practice. I pulled this definition from the American Occupational Therapy Association. It is the ability to use the current best information or the evidence to make decisions in caring for the consumers of OT services.

Lastly, health literacy is included in the Initiative of Healthy People 2030 via the CDC. They define health literacy as the ability for consumers to understand medical and clinical information that is either given to them or they are seeking out. Consumers can use this information to make good, sound health decisions. Healthy People 2030 breaks this down into two different kinds of health literacy. Personal health literacy is an individual doing this, and organizational health literacy is through an organization. At the organization level, this looks at how they can equitably enable individuals to find and understand information to use for health-related decisions.

During this talk, we will work on connecting these three terms because they are well-connected, and at times, interchangeable.

7 Pillars of Information Literacy

- Here are the seven pillars of information literacy:

- Identify

- Scope

- Plan

- Gather

- Evaluate

- Manage

- Present

(Bobish & Jacobson, 2014)

According to Bobish and Jacobson, who wrote a textbook called "100% Information Literacy Success," there are seven pillars of information literacy to translate to clinical environments. The first pillar is to identify. This means understanding what kind of information you need. The second is scope. This is knowing what is available. Planning is how you develop your strategy to go about finding that information. Gather is finding the information and getting it. Evaluate is one of the most important steps, and we will talk about that in a little bit more depth. This means assessing the information you found. Is it applicable and credible information? The sixth step is managing or organizing all of the information. There is so much information out there. How do we manage everything and use it effectively and ethically? The last part is to present the information. You have completed the first six steps to find information. Now, what are you going to do with it? It is sharing what you have learned, whether it is through written or verbal communication.

Information Literacy: The Classroom

- Is this taught in all undergraduate or graduate health care programs?

- Should it be done interprofessionally?

- Results in...

- Better interprofessional collaborative knowledge

- Evidence-based patient care

- Positive patient outcomes

(Rapchak et al., 2017)

A study from Duquesne University in Pittsburgh looked at teaching information literacy skills as an interprofessional course. They took students that were in school for nursing, pharmacy, and some of the other allied health professionals like occupational therapy. They looked at how they were teaching it in an undergrad program. The idea was that they could develop providers and practitioners that could solve real-world problems by working together. This resulted in the integration of information from various disciplines, evidence-based care, and positive patient outcomes to meet the needs of their clients or their families.

There are benefits to teaching information literacy in an academic environment. This makes sense because students need to locate and use the information to complete their academic assignments, fieldwork, and internships. The challenge or the less explicit piece is knowing then how to continue that. How does that really work in the real world or the busy clinical environment of occupational therapy?

Information Literacy: After Graduation

- Information literacy skills are needed to “find and apply current sources of evidence in the professional literature” (p.1), leading to the use of EBP in practice (DaLomba et al., 2018).

- Important for instructors to “convey importance of applying research information to patient care and inform students of ways to access this information after they graduate” (p. 468, Powell & Case-Smith, 2003).

- “Occupational therapy practitioners need access to information systems in the clinical setting that synthesize the research in a way that is readily applicable to patient-care issues” (p. 468, Powell & Case-Smith, 2003).

- Health care professionals “must keep up to date with the large amounts of biomedical literature produced each year to engage in professional best practices” (p. 265, Boruff & Thomas, 2011)

Here is a study from 2018 that looked at information literacy skills needed to find and apply current sources of evidence in the professional literature. This leads to good skills to providing evidence-based practice. Many studies outline this and look at information literacy in healthcare professions during their undergraduate and graduate programs. We have to teach this. We know that. There are fewer studies that look at how this translates into clinical practice.

I will use this older study from Ohio State University as they challenged occupational therapy faculty and library specialists to work together to convey the importance of applying research information to patient care and inform students of ways to access this information after they graduated. They found that the students could then recognize the real-world issues of information literacy which is much different than the academic world. In real-world practice, answers are often needed right away. You do not have a due date of next week or in a few weeks to get something done. Additionally, the resources out in the clinical environment sometimes dwindle a bit, depending on where you are working and how your facility/company supports finding information and databases. They looked at occupational therapy practitioners and felt that they needed to know how to access information systems in the clinical setting. Clinicians need to synthesize research and apply it to patient care issues.

The last study is from McGill University in Quebec. They looked at PT and OT students and how to prepare them for real-world challenges in healthcare settings. They said that PT and OT professional programs benefited from the integration and evaluation of information literacy concepts. This really works in tandem with evidence-based practice skills.

In summary, healthcare professionals need to keep up to date on large amounts of literature to engage in professional best practices. The way you do this is by having sound information literacy skills.

Information Literacy: Impact on Academia & Professional Practice

- Study from South African University looked at evidence-based health care teaching and learning strategies in undergraduate programs for OT, PT, SLH, & nutrition

- Emails from former students asking questions

- Improves patient care, avoid wasting resources, manage explosion of scientific literature, reduces mechanical rule following in favor of ‘expert judgment’

- Importance of allied health professionals

- Ability to find the ‘truth’ among all angles of evidence

- Helps to “deal with uncertainty in healthcare decision-making, the information overload [faced] in daily practice, and to make informed decisions about health care for best patient outcomes” (p. 15).

(Schoonees et al., 2017)

I love this newer study. They looked at what was called evidence-based health care teaching and learning in undergrad programs. Again, this was interdisciplinary. They looked at nutrition, OT/PT, and speech and language programs. Instructors from this South African University modified and changed their curriculum based on emails from former students. These former students were asking for evidence and articles. They asked for help from former instructors on finding information. These clinicians (post-graduation) needed to know how to find information, analyze it, and come up with recommendations. As a result, the instructors changed their curriculum to teach information literacy skills and connect them to the clinical environment.

After they switched their curriculum, they found that it helped their grads to improve patient care, avoid wasting resources, and manage the explosion of scientific literature. This gave the graduates more confidence and credibility when they would have discussions with people (even in policy/administration) or make recommendations.

Clinicians need to be able to find evidence to say something works or has to be implemented. This is how we translate information into clinical practice. This is especially true for allied professionals. This study said that allied health professions make up about 60% of our healthcare workers, supporting doctors, nurses, and people involved in patient care. They are part of multidisciplinary teams. We are the ones who are spending time with the clients and the patients. We are having to answer questions, explain things, and educate. In a lot of settings, we get more face time than the physicians or nursing. We have to sift through to find the truth among all the evidence that is out there.

Lastly, this is something I know my students and even seasoned practitioners struggle with. You never get a strict set of guidelines that you feel safe with. You always have to use clinical reasoning on the job. Clinical reasoning can be uncomfortable, and one treatment will not work with all individuals or in all settings. You need to search and find your own evidence. Being able to do that makes you more independent as a practitioner. It also increases a culture of continuous learning or lifelong learning. This is a big buzzword within occupational therapy. Academia cannot teach you everything that is out there in the profession. You have to commit to the fact that you will not know everything, but you will know how to find it. This is lifelong learning.

Information literacy helps deal with the uncertainty of the healthcare decision-making process, the information overload we face daily, and then making informed decisions about healthcare for the best patient outcomes.

Information Literacy: Transition to Clinical Environment

- Study in BHSc program at St. John University in York, UK

- Academia offers a narrow scope of information literacy

- Classroom learning needs to make sense later in professional practice

- Work environment has more specific needs for information, is related to job performance, and related to environmental influences

- Information literacy is connected to health literacy and will improve communication between patient/client and health care professional

(Spring, 2018)

This study found that academic programs need to teach information literacy and teach it in the context of a healthcare environment instead of using the narrow scope of the academic/classroom-based environment. As I said, in academia, you have longer timeframes to find your information. And, you are given a lot of guidance, specifics, and grading rubrics. Resources are also provided like textbooks, databases, and university libraries.

This study challenged academicians to make information literacy skills training applicable and meaningful to the work environment related to patient outcomes and job performance.

Information literacy is connected to health literacy. We need to start making that connection to improve communication between ourselves and the clients/families we serve.

Skill to Prepare for Healthcare Environment

- Study in BSN program at Northern Michigan University

- Health care environments are increasingly “technological & data-rich” (p. 101)

- Assignments need to increase students ability to recognize need for information, locate/evaluate/use information, appreciate information literacy, and be able to connect it to safe and effective patient care

(Flood et al., 2010)

The Institute of Medicine endorsed the development of five competencies that were essential for all health care providers.

IOM's 5 Competencies Essential to Health Care Providers

- Provide patient-centered care

- Work in interdisciplinary teams

- Use EBP

- Apply quality improvement

- Use informatics

They merge technology skills and the use of evidence-based practice. All of these things are going to overlap. We know that the healthcare environment is very technological and data-rich. There is so much information out there, and technology plays a big role in that. We have so much at our fingertips these days. The authors felt that it is the job of the instructors to develop a curriculum to help bridge this to practice.

Thus, they created a curriculum and built upon that via scaffolding. They started with easy/novice assignments. They first asked, as an example, "What the role is of occupational therapy with a patient who has diabetes?" Then, they ramped this up to an intermediate integration of skills asking for the student to design an educational brochure for the client with diabetes, including treatment recommendations and interventions. Lastly, using more advanced skills with a complex patient, they asked, "What do you need to know about the patient and their health concerns? What kind of education do you need to provide to that patient, the family, and the interdisciplinary team? What does this mean to greater overall health or public health concerns? And, how do we put this all together?" This is asking for real-life clinical decisions?

This is again connecting information literacy to lifelong learning. Information literacy should and could be a lifelong learning skill. It must be.

Information Literacy Is Lifelong Learning

- “Information literacy should and could be a lifelong learning skill” (p. 114)

- Little effort to Google, but are you getting the right info?

- “Health information can shift, change and become defunct remarkably quickly” (p 113).

- Benefit = quick info

- Risk = losing key information skills or making assumptions

- Rise of the ‘informed patient’

- Clients want to collaborate or corroborate rather than be ‘taught’

- Technological literacy does not equal information literacy

- Clients may misinterpret data, be misinformed, or persuaded

- Digital divide – not everyone can access technology

- Little effort to Google, but are you getting the right info?

(Lipczynska, 2014)

This is an editorial from 2014 that focused on information literacy skills and how they should be introduced in undergraduate/graduate education. And how these information literacy skills need to be revisited throughout that education, taken with that student on to clinical work, and then still used within the professional career. They gave some reasons why. We all Google or use search engines. There is a minimal effort put into using Google. However, you then need to figure out if you are getting the right information. This is where you need to be an educated gatekeeper of information and do some of your own evaluation. You need to make decisions about what is good health information. Things can shift and become defunct remarkably quickly. New things are exploding on the internet every day. This was especially true during the pandemic.

We also know that there can be good intentions with bad treatment. For example, in the '50s, they gave pregnant women all kinds of drugs for morning sickness or whatever was ailing them. They thought that medications could not cross that placental barrier. Pregnant women were also smoking and drinking. Even today, there are medication recalls or treatments that did work. Current evidence does not back them up. We know that things shift and change quickly, and it is not because people wanted to put information out there that was bad. They just learned more since the information was disseminated.

Keeping up with new information is vital. The benefit to a Google search is that you get quick information. The risk is that we sometimes lose those skills needed and do not pick through information and find the good stuff. We make assumptions based on bad or quick information.

The other piece of this is that our clients are Googling as well. They also have information at their fingertips. This is leading to the phenomenon called the rise of the "informed patient." Our patients want to collaborate with their healthcare providers. They do not just want you to treat them. They want you to validate what they found and confirm it, rather than just listening to what you have to say.

Occupational therapy is client-centered, and we are collaborative. However, we also need to be the good gatekeepers of information and give the proper information. Access to technology does not mean that you have good information literacy skills or a good consumer of that information. I see this all the time, and I am sure you have examples as well. "I was just told to squeeze a ball, and my hand issue will go away." Or, they will come in with over-the-counter splints. They may also request Kinesiotape after watching the Olympics or a sporting event. They may come in with ideas of treatment, but it might not be the right treatment.

The last thing discussed in this editorial, which I really appreciated, is the digital divide. Not everybody has access to technology or information at their fingertips. It is our job as practitioners to help them find that information and understand it. Lifelong learning is there for our clients and us. We should respect the skills needed to be good consumers of information.

Health Information Literacy Meets EBP

- EBP = research + patient values + (your own experience)

- When we present evidence that we have looked into … consumers needs to be able to understand it & make good decisions

- Consumers also are looking up their own info – but where?

- Example – do carrots reduce cholesterol??

- Using EBP skills is our duty to inform the public & create awareness of good information within medicine

- Health literacy is “about consumers being able to understand the medical information their caregivers give them or they find through the Internet and being able to use that information to make good decisions about their own course of care” (p. 1)

(Schardt, 2011)

This study merges all of these terms: evidence-based practice, health literacy, and information literacy. They talk about how evidence-based practice (most of us probably already know this) is a combination. It is not just reading the latest research article, but the research plus your patient values, what your clients want, and then your own experience. You are coming in with that experience as well. Those three things together are evidence, and that is evidence-based practice.

When we present our evidence to our clients, they need to understand what we are talking about. They need to understand what you are telling them and how they can make an informed decision based on this. This is the hallmark of health literacy. As we said, clients are more informed, and they are going to find their own information. They may be using self-help books besides the Internet. There is actually a self-help book out there that says that carrots can reduce cholesterol by 20%. I do not mind carrots-- I will eat some carrots to reduce my cholesterol. However, this is based on a report of five Scottish men who ate a half-pound of carrots for breakfast each day. And, this is published in a self-help book! As you can see, there are limitations.

We can help our clients have access to better information like a Cochrane review. For example, a Cochrane review may look at screening and mammography for breast cancer. They may use seven different trials and over 600,000 women with randomized control trials and random assignments. This is a much different ball game than five Scottish men.

We cannot use our evidence-based practice skills without information literacy skills. This is our duty to do so and inform the public. We need to create awareness of good information within medicine and within occupational therapy. We are the healthcare practitioners that have the opportunity to explain information to clients to help them make informed health decisions. We play a role in increasing their health literacy.

Information Literacy Improves Health Literacy

- Study stresses how important the “correct and appropriate use of appropriate and reliable information is essential in health care” (p.1)

- Reinforced era of the ‘informed patient’ in the community

- Access to electronic & web-based health information in mass quantities

- People make decisions about health and safety based on this information

- Not everything on the internet is valid, correct, appropriate

(Dastani & Sattart, 2017)

People in the community are accessing web-based health information in mass quantities as it is readily available. People are making decisions based on these findings, and those decisions impact their health and safety. We know not all information out there is valid, reliable, and appropriate. This study looked at how information literacy skills like identifying, accessing, and evaluating information are needed. Not only is it needed to be taught on a community level, but this also needs to be promoted to individuals to help them make good health decisions.

Connection to OT’s Vision 2025

- “As an inclusive profession, occupational therapy maximizes health, well-being, and quality of life for all people, populations, and communities through effective solutions that facilitate participation in everyday living.”

https://www.aota.org/AboutAOTA/vision-2025.aspx

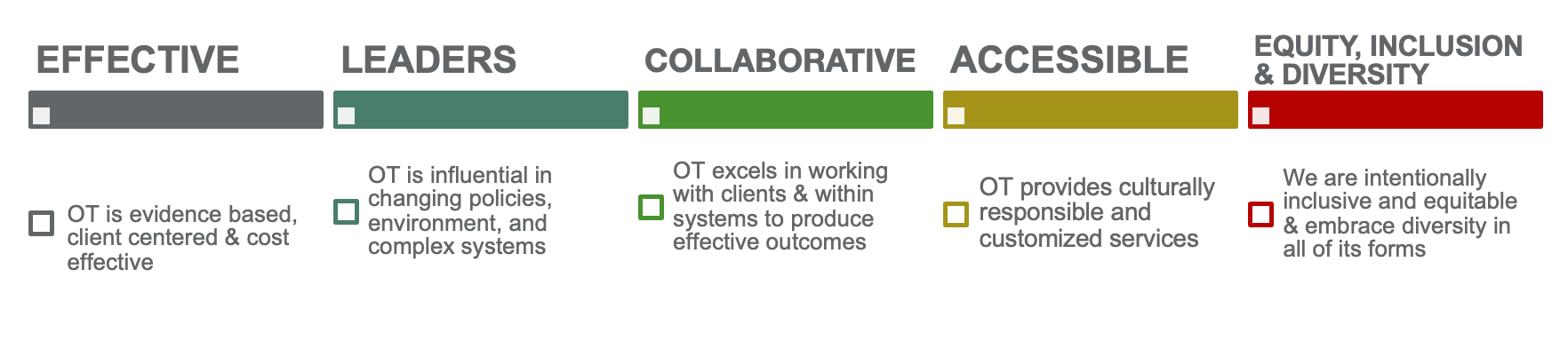

The American Occupational Therapy Association and Vision 2025 has these different pillars, as noted in Figure 1. We know that having sound information literacy skills will contribute to and align with this Vision 2025. You can look at these different pillars that are on here,

Figure 1. Pillars for the AOTA Vision 2025.

First, there needs to be evidence-based practice that is client-centered care and cost-effective. We can have a role in changing policies. We are collaborative and can talk with others about information. The last two pieces are having accessible services and being equitable, inclusive, and embracing diversity in services. You can make an argument that this can be for information literacy skills as well. Any of these pillars speak to needing, finding, and conveying information, whether it is to other OT practitioners, policymakers, or consumers of OT services.

Connection to OT Advocacy

- OT's Distinct Value

- “Occupational therapy’s distinct value is to improve health and quality of life through facilitating participation and engagement in occupations, the meaningful, necessary, and familiar activities of everyday life. Occupational therapy is client-centered, achieves positive outcomes, and is cost-effective.”

- https://www.aota.org/~/media/Corporate/Files/Secure/Practice/distinct-value-rehab.pdf

- Value-Based OT

- “Emphasize the value of services provided rather than rewarding the volume of services”

- https://www.aota.org/Practice/Manage/value.aspx

We are making big strides in advocating for occupational therapy services and getting the word out there, but there is more work to be done. It is certainly not the best-known profession yet. Of course, I think it is the best profession. Information literacy can lead us to provide sound evidence-based interventions which can support OT advocacy.

Consider what is going on right now regarding payment and justifying OT's distinct value in a very crowded healthcare environment. The distinct value campaign by the AOTA promotes that OT is client-centered, has positive outcomes, and is cost-effective. We need to be prepared to speak to this and prove this. If we are going to talk that talk, we have to walk that walk.

In the past few years, we have seen this shift from quantity to quality. Outcomes are more important than meeting our minutes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Quantity versus quality graphic.

Medicare and other payers and health systems are starting to emphasize that there is a value to the services rather than rewarding the volume of services we are providing. This transition is an opportunity for occupational therapy practitioners to highlight our distinct value by understanding and applying quality measures to everyday practice. To do this, we need to use some of these pillars of information literacy.

Pillars of Information Literacy and Application to OT

- Identify

- Scope

- Plan

- Gather

- Evaluate

- Manage

- Present

(Bobish & Jacobson, 2014)

Here are those seven pillars again. They are identify, scope, plan, gather, evaluate, manage, and present. This is not a step-by-step guide. You do not need to hit each one of these. They do not always happen in order, nor do you need to spend a lot of time on each one. I will go through each one and make a case for how it applies to occupational therapy.

Identify

- What do I already know? What else do I need to know? = your ‘research’ question

Identify is understanding what information you need, what you already know, and what else you need to know. Where do I need to fill in those gaps? In essence, this is your research question. I do not mean a big research question. It can be as simple as a client in practice that you have some questions about their diagnosis or treatment plan. Sometimes you need the information to report back to the team/client, and sometimes these questions are a lot bigger and require you to advance your knowledge in this area. For example, earlier, I talked about the patient with a Boutonniere deformity. I had not seen the patient yet when I got the script from the doctor. It said, "Boutonniere deformity, please use serial casting." I already know what a Boutonniere deformity was and know anatomically what was going on. I also know that serial casting is a treatment for this particular deformity. However, I still had to look up a few things. What are the parameters? How long am I supposed to do this for how many weeks? How long is it supposed to stay on before I change it? Things changed went my patient came in. She was an older woman that used a Rollator walker. She was coming from assisted living. I changed my mind about the serial casting due to her situation and fragile skin. I decided to look up some information to see what else I could do that was as effective. I was worried about sending her back to the assisted living where I knew someone would not watch it closely. She also did not have great transportation access to get back to my outpatient clinic to get the serial cast changed. I just started thinking this was not the best practice for this client. I started problem-solving a little bit.

Other "research" type questions include the ones I talked about earlier. For example, my colleague thinks that pet therapy has benefits. Now, she needs the evidence to boost this idea. I also treat a lot of individuals after a thumb arthroplasty. They all want to know when it is safe to go back to work. Another example is I had a group of students who were interested in occupational therapy and opioid addiction. They wanted to know what they could do to help with recovery and treatment. These questions take a little bit more time to frame out. We are not just repeating knowledge back, but we are advancing and synthesizing some things for the profession.

Scope

- What is available?

- Free web

- Database

- Library

- Other?

“The search engine is now as essential as the stethoscope” (Schoonees, Rohwer & Young, 2017, p.2).

The second pillar is scope. This is finding out what is available. After we identify a problem, then you have to fill in the gaps of knowledge. Scope starts this process for you by planning where the appropriate places to get that information. This is going to vary greatly. There are times that it is a quick Google search to find information that you need. You may need to look up a medication name or the dermatomes for a median nerve laceration. Those are pretty quick Google searches. I may search Amazon for a certain product. If the question is a little more complex, it may not be appropriate to look on Google or Amazon. Perhaps I want to see the outcomes for a thumb arthroplasty or mirror therapy for complex regional pain syndrome. Building the case for pet therapy in skilled nursing facilities or OT's role in opioid addiction are other examples of bigger searches. These are more scholarly inquiries that might lead you to different databases. Another example I gave earlier about helping families find sensory-friendly community events or inclusive playgrounds is not going to be found on these databases or in my university library. This is going to be a totally different kind of search. I want to impart that all this information cannot be found on technology sources. People are also good resources for information. You may need to ask colleagues or experts in this area. Human capital is significant too. And I love this quote that says that "the search engine is now as essential as the stethoscope in healthcare." This speaks to our time right now and how we need access to information.

Getting information: journal articles.

- AOTA Membership

- American Journal of Occupational Therapy

- British Journal of Occupational Therapy

- Australian Occupational Therapy Journal

- Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

- OT Practice – Trade Magazine

- OT Search – abstracts only

- NBCOT

- ProQuest Database

- OT SEARCH

- Need a subscription

- OT Seeker

- Free online – abstracts only

- www.otseeker.com

One good place to access information is in journal articles. As far as credibility, any gatekeeping and peer reviews have already been completed. You still have to make sure it applies to your cause. An American Occupational Therapy Association membership is a great resource. In addition to the "American Journal of Occupational Therapy" or AJOT as part of your membership, you also have access to other international journals like the "British Journal," "Australian Journal," and "Canadian Journal." You also get the trade magazine, "OT Practice." I love "OT Practice" because it is so digestible with pictures and graphs. I can quickly look at this information and figure out what they are trying to tell me.

Another feature is the "OT Search," which is not part of an AOTA membership but part of an OT subscription database. If you maintain your NBCOT credentials, which is important in my opinion, you get access to a ProQuest database. This is an excellent database. OT Search is an OT database that houses information from 1910 through the present. There are over 46,000 records are in there, and they are all OT relevant. The last one on here is a free online OT search engine called OT Seeker. This is for abstracts only.

AOTA membership benefits with EBP.

- Practice resources by practice area

- Children & Youth, Mental Health, Rehab & Disability, Health & Wellness, Productive Aging, Work & Industry

- Publications

- Practice guidelines

- Critically Appraised Topics

- AJOT issues

- Choosing Wisely Campaign

- Everyday Evidence Podcasts

https://www.aota.org/Practice/Researchers.aspx

Another member benefit of an AOTA membership is that they do a lot of evidence-based practice crunching for you. You do not have to search the databases and see what is out there in terms of the research articles. They compile it for you by practice area. I work within work and industry, and I can go right in that area and find great information.

They also publish evidence-based practice themes within their publications. This includes practice guidelines, critically appraised topics, and articles within AJOT. They support the Choosing Wisely Campaign with the American Board of Internal Medicine, which is the idea that consumers should question the interventions of therapists that they work with to make sure that they are not duplicated and that there is evidence to back them up. There was something on this in the latest "OT Practice" on that. They also have everyday evidence podcasts as well.

University partnerships.

- OT Search & OT Seeker

- PEDro Physiotherapy Evidence Database

- Clinical Key

- CINAHL

- Proquest Health & Medical Complete

- PubMed

- PsychNET

- Academic Search Premier

- Access Medicine

- Cochrane Library

- Writing & Citing Resources

- Video Library

- Evidence Based Medicine Resources

I also have to plug university partnerships as they are a good source of information. Via university library systems, we can have access to large databases that are subscription only. Above I have listed the ones that my students use the most. Some of them are definitely my "go-to's."

There are also writing and citing resources. Additionally, there are video libraries, evidence-based medicine resources, and information resources. It is great to have that university partnership. You can leverage that and use your students to look up information for you. This will help to teach them those skills. You also may be able to reach out to an academic clinical education coordinator and ask for access to an article. Partnerships are important and can be mutually beneficial. Perhaps we can take a student, be a guest lecturer, or volunteer for something, and they can help you access good information.

Plan

- Specifics of searching

- Choose a tool

- Keywords

- Boolean operator

The next pillar is planning. This is choosing how you are going to start. You found your question, and now you know where you are going to look. This is how you are going to start searching. Sometimes, it is starting to brainstorm some terms or using advanced searches.

Boolean searching.

- And-Or-Not

- Which search term(s) will make your search broader (more results)?

- Which term(s) will make your search more narrow (less results)?

- Why have ‘NOT’?

One of the things that I find really helpful is Boolean operators. This is the use of the search words AND, OR, and NOT. This usually makes your search narrower or broader, depending upon what term you use. We also have "not" as a way to filter things out.

Boolean searching example.

- I want to learn more about the opioid crisis.

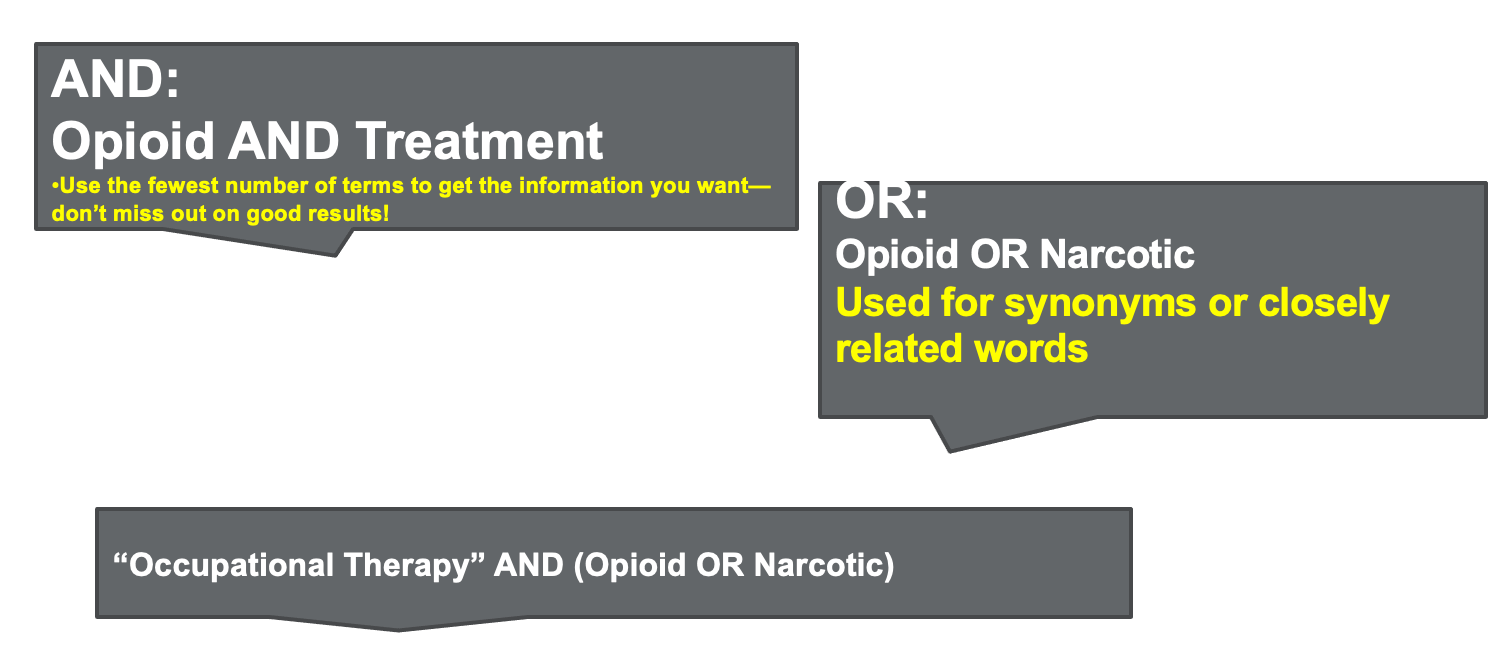

Let's see what that looks like in a practical example in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Boolean search example.

In the example, we are researching the opioid crisis. If you just search for opioids, you will get maybe a definition or other related concepts like addiction, abuse risk factors, overdose statistics, treatment, et cetera. If you use a Boolean operator, opioids "AND" treatment, it will only search for things that have those two things in common. If you did not use that combination, your search is going to blow up. If you only want opioid and the treatment side of it, you should be fine. However, words have synonyms or closely related words. For example, opioids and narcotics might go hand-in-hand. Narcotic treatment might be the same as opioid treatment. You could use the "OR" operator. This will look for articles with opioids or narcotics in the content. This is a way to broaden the search and make sure you get all of the pertinent articles. If you want to put this all together, it kind of looks like a math equation. You are going to use "occupational therapy" AND opioid OR narcotic. Thus, all of your search results should connect occupational therapy with either opioids or narcotics. By putting occupational therapy in quotation marks, this chunks those two words together. It is only going to search for that phrase together, not those two words separately. I find this really useful.

- NOT: “Opioid Treatment” NOT “Detoxification”

- Give me all the information EXCEPT for…

What I do not find quite as useful is using the "NOT" operator. Here is what that would look like. You want to learn about opioid treatment, but you do not want to know about detox. You would say opioid treatment, NOT detoxification. You want all opioid treatment but detox.

Topic hierarchies.

- *Knowing the broader and narrower categories of your topic can help you search wisely

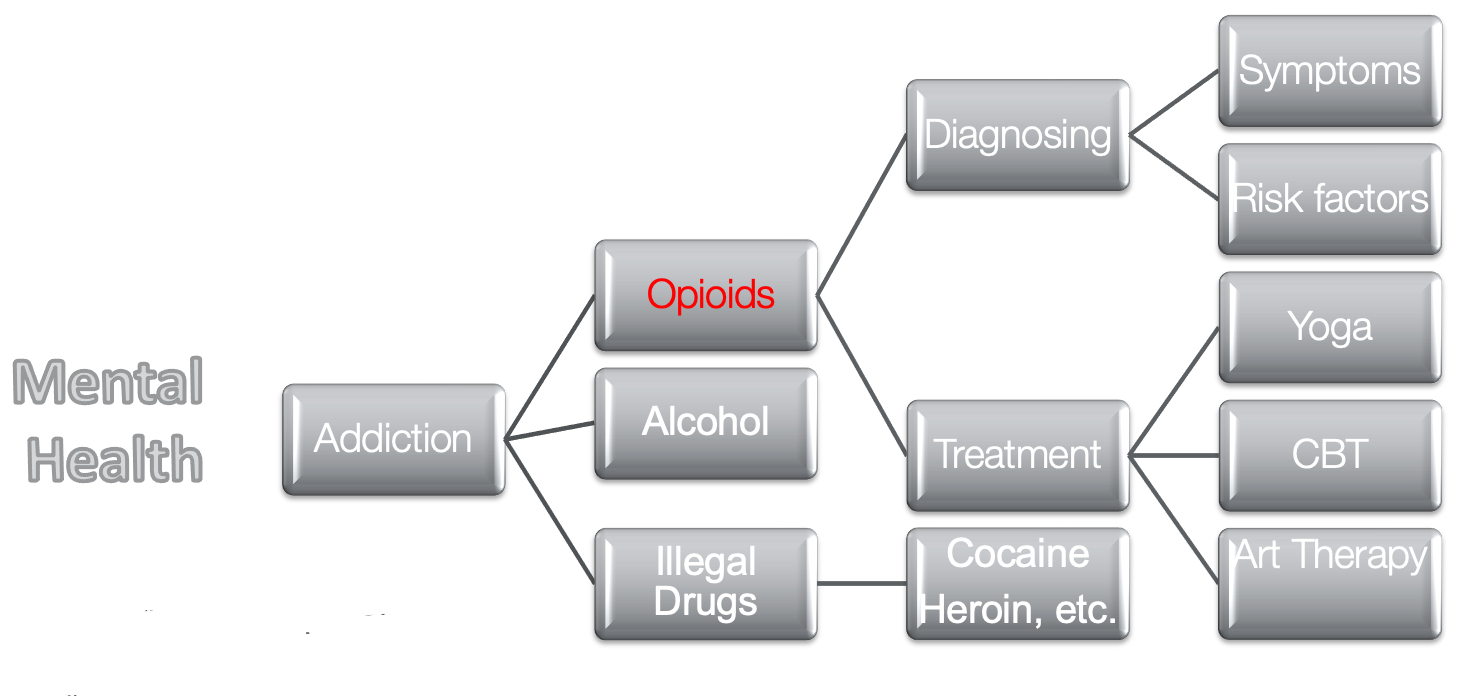

Topic hierarchies can be helpful when you are doing brainstorming and plugging things in. It is important to know where your topic is within a hierarchy. You can see where the term opioids falls in this hierarchy in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Word hierarchy for searching example.

There are going to be more narrow terms and broader terms. Knowing the broader terms can help you when brainstorming, and the narrower terms lead to a more focused research question. For example, we are looking at opioid addiction. If we just looked at addiction, we would find many different kinds of addiction. What do we want to know about opioids? Do we want to know how to diagnose that addiction? Do we want to know about treatment options? We want to know about treatment options. When we plug things in, you can see many treatment options for opioid treatment like yoga, cognitive behavioral therapy, and art therapy. We can keep narrowing that down to get to some articles or an answer to our question. If we are not finding enough resources, we have to go broader. We may start at mental health disorders and narrow it from there.

Keyword vs. controlled vocabulary searching.

- Keywords

- Quick

- Work well … if you know the right words to use

- Might miss info due to synonyms

- You can’t explain ‘context’ to a database or search engine

- Controlled vocabulary

- Find more relevant information

- Learn the lingo

- Unintuitive

- Not uniform across databases

- Missing for over 80% of electronic formats

Keywords are great for brainstorming. They are quick, and they work well if you know all the right words to use. However, there might be synonyms, and you miss that information. For example, if you put in the words occupational therapy and stroke, the search engine may not know to look for occupational therapy and cerebrovascular accident, which we know is a synonym for stroke. You cannot explain the context to a database.

A controlled vocabulary is a feature where some databases have their own vocabulary that they like to use. You put in stroke, and they know that stroke and CVA are the same things. A controlled vocabulary happens in PubMed that has medical subject headings. OT Search has a thesaurus. The problem is that they are not always easy to use, and over 80% of electronic formats (even Google) do not have them. Keyword searching is usually the way to go.

Searching strategies summary.

- Boolean operators

- Word hierarchies

- Keyword vs. Controlled Vocab

- Phrase Searching

- Advanced Search Options

In summary, we have different search strategies. Boolean operators use different key conjunctions (AND, OR, NOT) to sort. Word hierarchies help decide narrower and broader terms. Keywords can be quick, but they have limitations. And if a controlled vocabulary is available, go ahead and see if you can use it. Phrase searching and chunking things together in quotation marks is really helpful. Lastly, you can use advanced search options to narrow by dates, file type, authors, or publication.

Gather

- Find it!

- Know when you have enough

This is when you are going to consider your range of sources and know how much is enough. Is this a one-and-done search where you can move on? Or, is it in your best interest to do multiple searches to support your topic across different databases or types of publications? How much time do you have to dedicate to this? When do you need this information by? There are both short searches and bigger projects.

Evaluate

- Currency

- Relevance

- Authority

- Accuracy

- Purpose

Next is evaluate. You can evaluate based on this test which is so affectionately called the CRAAP test. It is published in a lot of library associations.

CRAAP Test.

- Currency

- Relevance

- Authority

- Accuracy

- Purpose

(Duquesne University, 2020)

This one I pulled from Duquesne. It stands for currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, and purpose. Currency is asking when the information was written. How often is it updated or published? You really need to be careful of this on the web. Is there new updated information that is updated regularly? If it is dated, is that still relevant? It could be a topic that changes frequently or one that stays the same. The R is relevance. Is the information you are finding from that search relevant to your argument or your question? When you pull in a lot of information to determine if something is relevant, I recommend skimming and scanning by reading headings and looking at keywords, pictures, and graphs. Skim to the abstract and conclusion quickly. In terms of authority, you want to see who the author is and their credentials. I tell my students to take that author and dump it into Google scholar and see if they have written other things. You can find about the credibility of an author pretty quickly. What qualifies them to speak on this topic? What affiliations do they have? How do they give this information? Who published this? Look for any type of bias. In terms of accuracy, is the source well-documented? Where did they get their information from? Is it cited? Are their references? Is it presented as this is fact? Or, is it presented as this is our opinion? Could you verify the information on another source that you know is accurate? If something has typographical errors and poor editing, that is a red flag. It is harder when a site looks excellent, and you have to pick through to see if it really is a good site. Clean sites do not always mean that they are accurate sites. All you know is that time was spent on it. It is your job to use this test to evaluate. The last parameter is purpose. Why was this information written? Why was it published? Uncover any obvious biases or any kind of prejudices. Does it look at multiple points of view? If there is a counter-argument, do they address it? Do they acknowledge it? If you go through those steps, especially on the free web where you need to be the gatekeeper, this will help you to find good information.

Manage

- Ethical & Responsible Use of Information

Plagiarism is a real thing, and it is not just people who write academic papers. Think about it in your practice. You may grab something and photocopy only a portion of it or cut and paste things off the internet. Think about how you are using information. Are you doing it ethically and responsibly? Keep track of your sources. Know how to reference things appropriately if you are writing them out. Put that citation at the bottom. I once wrote a whole protocol for tennis elbow. It was not my information, but I pulled it from the source I really loved. I made sure to put that where I got it from. It is academic integrity that we teach in a university that carries over to professional integrity and upholding our code of ethics. In 2020, there was a new code of ethics published by the AOTA. This falls under the principle of veracity. There are categories such as professional integrity, responsibility, and accountability. There is also a category for professional competence, education, supervision, and training. Under that category, there is a specific standard of ethical behavior, standard 5-I. This talks about plagiarism and copyright law. It is our duty to make sure that we are putting information out there ethically and responsibly.

Present

- Verbal vs. Written

- Consider Audience

- Synthesize & Summarize

The last thing is present. You did all this work, and now, who will be the recipient of that information? It could be verbal or written. You could write an article, present a poster at a conference, create a patient education handout, or design a bulletin board at work for OT month. You could put together a home exercise program or a letter of medical necessity. You always have to consider your audience. Are you posting things on social media to promote occupational therapy? Think about where you got the information, and if it is good. It could be verbal communication or an oral presentation. An example could be presenting at a care conference to an interdisciplinary team. It also could be simple, like explaining something to a patient or a family member, or it could be more complex, like talking to a legislator, administrator, or a case manager. You need to synthesize and summarize the information using key points. Be effective, efficient, and get that information out there.

Examples

To wrap up today, I am going to use some examples.

Professional Development Example

- Steps: Identify, Scope, Plan, Gather, Evaluate, Manage, Present

- Interested in learning more about the role of OT with opioid addiction

- Narrow your research question

- Find support

- Where?

- Evaluate the evidence

- Current, relevant

- Present information at a conference

- Write up proposal

- Figure out the best way to visually present information

The first example is a professional development example, a little bit more of a longer-term project that uses the steps of information literacy. As I said, I had a group of students who felt stro