Introduction

Thank you so much. I love getting to talk about sleep. Our learning outcomes today are to distinguish between typical sleep patterns and what we would identify as problem sleep, to identify confounding factors that affect sleep hygiene in the elderly, to describe how sleep deficits impact function, behavior, and participation, and to determine appropriate responses to sleep problems in the elderly.

Typical Sleep & Sleep Architecture

We need to start talking about what sleep architecture is and what we should be getting as adults.

What We Should Get

- Newborns (0-3 months): Sleep range narrowed to 14-17 hours each day (previously, 12-18)

- Infants (4-11 months): Sleep range widened two hours to 12-15 hours (previously, 14-15)

- Toddlers (1-2 years): Sleep range widened by one hour to 11-14 hours (previously, 12-14)

- Preschoolers (3-5): Sleep range widened by one hour to 10-13 hours (previously, 11-13)

- School-age children (6-13): Sleep range widened by one hour to 9-11 hours (previously, 10-11)

- Teenagers (14-17): Sleep range widened by one hour to 8-10 hours (previously, 8.5-9.5)

- Younger adults (18-25): Sleep range is 7-9 hours (new category)

- Adults (26-64): No change with 7-9 hours

- Older adults (65+): Sleep range is 7-8 hours (new category)

Here is the type of sleep that we should be getting through the lifespan. There is something in here for everyone. Participants will find something for themselves, their parents, and their children. This is provided by The National Sleep Foundation. Their website has an infographic that is downloadable for you, but these recommendations came out in 2017. They represent a few changes from prior recommendations based on the most current information available from the sleep research. Earlier recommendations did not necessarily allow for the variation in individual requirements of sleep, but these current recommendations allow a range instead of a specific hour amount for those who require either slightly more or slightly less sleep than others. Changes in amounts over the years have included a narrower band for newborns, down to 14 to 17 hours each day. Previously, it was recommended of 12 to 18. Also, many of the pediatric and adult ranges have been widened by one or two hours, and the adult range is also now divided into separate bands for teenagers, young adults, and adults. You can see there is also a widening of the range of hours for infants and toddlers. Around the time a child is going to school, it is down to about nine to 11, and then if you have any teenagers at home, you will see it is trimmed a little bit, but the range is widened by an hour. It has been identified that they do still need greater than eight hours of sleep. Teenages are still recommended to get roughly 8-10 hours. And, as I stated earlier, they have split off the older categories, but as you can see, they are still recommending seven to nine hours. And older adults (65+), they have identified as a new category altogether and recommend seven to eight hours. They are finally recognizing that older adults have different sleep needs than prior ages.

What We Actually Get

- Sleep Health Index®/National Sleep Foundation

- Americans report sleeping an average of 7:36/night.

- On workdays, the average bedtime was 10:55 PM and the average wake time was 6:38 AM

- Average sleep time was 40 minutes longer on non-work days

- Americans aged 18-29 reported latest bedtimes

- Sleep duration did not differ between men and women

In 2017, the peer-reviewed journal Sleep Health, which is the journal of The National Sleep Foundation, rolled out a new 12 item survey tool called The Sleep Health Index. It was developed in 2014, and over the next two years, they surveyed over 2,500 adult Americans using that index. They used factor analysis and identified three different sleep domains which they called sleep quality, sleep duration, and then disordered sleep. The index provides 100 point score in each of those sub areas, and then an overall roll-up. The tool also used regression analysis to determine the independent predictors of sleep. You can see that following their two years of research that the average American is reporting about seven hours and 36 minutes of sleep a night, which is well within that recommended range that we just looked at on the prior slide, and this is using a substantial sample size in their study. Not surprisingly, on work days, the average bedtime was 10:55 p.m. and the average wake time was 6:38 a.m. And, sleep was 40 minutes longer on non-work days. Also not surprisingly, young adults aged 18 to 29 reported the latest bedtimes. Lastly, in this study, sleep duration did not differ between men and women.

Population Surveyed

You may be wondering, "Who are these people that are sleeping an average of seven hours and 36 minutes a night?" as you may be getting substantially less sleep.

- 48% men, 52% of women

- Fairly even distribution of age and income

- Age predicted disordered sleep, but not quality or duration.

- 57% employed

- Employment negatively affects sleep duration (length of time spent sleeping) but not quality

- 66% White, 12% Black, 15% Latinx, 7% Other

However, the population surveyed was about evenly distributed between men and women, and it was fairly distributed across a full range of income. Older age was found to predict disordered sleep, but it did not affect sleep quality or duration. And, as we will go on to discuss, disordered sleep means that sleep is broken up across the day rather than consolidated into a single sleep set as you or I might sleep. So, age did predict disordered sleep, but the quality and duration of that sleep were unaffected by age. Of note, only 57% of the sample was employed, the remainder were categorized as either unemployed which they classified as students or retired, on disability, a stay-at-home parent, or in fact fully unemployed. The regression model indicated that employment negatively affected sleep duration. The length of time spent sleeping was affected by employment but not the quality of that sleep and this did not contribute to disordered sleep. That is, having either a part-time or full-time job meant that you simply spent less time in bed. A full two-thirds of the sample identified as white, and there is a growing body of literature that does describe racial and ethnic sleep disparities. What is important is to know that prior to this very recent study and tool, there was not a valid and reliable research survey that determined the current state of sleep health. We hope that now there is and that this study opened up the door for additional studies that will focus on the unique issues affecting minority populations as well as aging. The tool was not designed to be administered to a pediatric population so the study excluded youth and also anyone identified with a disability.

Normal Sleep Architecture

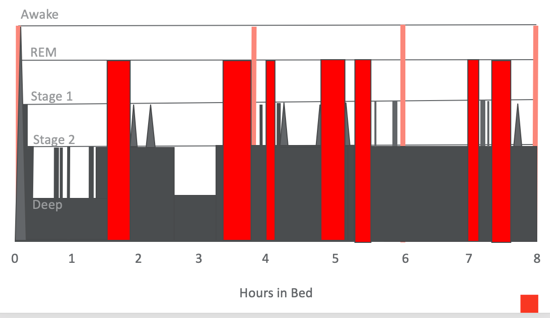

We are going to spend a lot of time on this slide (Figure 1) as we are going to reference the concepts often as we continue.

Figure 1. Normal sleep architecture.

You probably know that REM sleep, rapid eye movement, and non-REM sleep make up a normal sleep cycle. What do these cycles look like? How many times do we cycle through, and what happens when we do not get adequate REM sleep, or how does sleep get disrupted or disorganized? Graphics similar to these may look familiar to you if you have used either a sleep app or a fitness band. These can track your nocturnal movements and your heart rate which give an indication of your sleep trends. If we take a closer look at this graphic, you can see that the x-axis is the number of hours in bed. The left side is the beginning of the night, and then we are assuming an eight-hour sleep duration within this graph. The y-axis is the stages of sleep. There are the REM stages, Stage 1 sleep, Stage 2, and then deep sleep. In normal sleep architecture, you can see that you are at a state of wakefulness at the beginning of your sleep cycle here and then at the end of your sleep cycle as you are waking up. There are also a couple of times during the night where there are periods of wakefulness which are very normal. You see these occurring at four hours in bed and again at six hours in bed, when you actually wake up from your sleep cycle. During these periods, you may drop back down, as you see, as it is a fairly short episode of wakefulness. If you are undisturbed, there is the opportunity to drop back down into stage two sleep, but if something is disruptive like you are too warm or there is a noise outside, you may actually come to a full state of wakefulness at these particular periods. And again, it occurs at about four and six hours in bed, and you see that anecdotally in your conversations with people as well. You will commonly hear, "Oh, I only got four hours of sleep," or "I got six hours of sleep." You rarely hear, "Oh, I only got three hours of sleep last night." This is because, in this third hour of sleep, you are usually in one of your deepest sleep phases, at least in nighttime sleep.

The next thing I would like you to notice is that when you are first falling asleep, here at the front of your sleep cycle, you can see a "waterfalling" down from wakefulness to Stage 1, Stage 2, and then deep sleep really very quickly in just a matter of minutes. This occurs in the very front of the first hour of sleep. Let's discuss those stages. All three levels are considered non-REM. REM periods are the red bars that occur sprinkled throughout the sleep cycle here. These are your periods of REM. We will not get to REM sleep until we have been asleep for not quite two hours, and then we have our first REM phase. Primarily, at the front of our sleep, there are non-REM cycles. Reflect on your own sleep as we talk about this chart because we are going to assume that you are a typical sleeper. In non-REM, stage 1, your eyes are heavy and they are closed, but you may not feel as if you are quite asleep. You do not spend too much time here before dropping down into Stage 2. At Stage 2, this is when you feel your muscles both contract and relax and your heart rate and your body temperature go down. You are here for just a few moments, and then fairly quickly you drop into Stage 3, or deep sleep. This is depicted as the deepest sleep within the cycle. At this stage, you are so deeply asleep that you are a bit disoriented if you are awoken. You fall into that deep sleep fairly quickly on the front end of the evening. There are a few bursts back into Stage 2 sleep, and this is when you might notice that suddenly your body might jerk or jump which occurs at those Stage 2 spikes. You are in deep sleep for about the first two hours of your sleep cycle and then again at about three to three and a half hours that you are in bed. You see the bottom dips stop happening after that third hour in bed and have extinguished from typical sleep. Thinking about those hours when I was trying to sneak money under the Tooth Fairy pillow in the middle of the night, I would have been better to have done that in the front end of my child's sleep cycle because that is where the deepest sleep occurs.

Now, let's talk about REM which first appears as this red bar you see just inside of two hours, or about 90 minutes after you fall asleep. One thing you will notice about those red bars is that the width of REM sleep in each of those bars is variable. Most REM cycles are about 10 minutes long with some are a little less and some are a little more. REM is actually a very active sleep phase in which not only are you moving your eyes very quickly but your heart rate and your respiration rate increase from what they were. These are sprinkled throughout the sleep cycle, but they do not begin until you have been asleep for not quite two hours. You will also notice that none of those REM cycles occur at the same time as Level 3 deep sleep. REM only occurs during Stage 2 sleep. When you are in your deepest sleep, you are not having REM. Another thing you see on this normal sleep cycle is that there are several points in the evening in which your body returns to very light sleep. These spikes take you all the way up into Stage 1 or even those points at which you are fully awake. This is completely typical even if you as the sleeper do not register wakefulness. This is something we go on to discuss relative to the sleep environment so keep it in mind for later.

The takeaway message from this slide on normal sleep architecture is that in normal sleep, deep sleep is occurring on the front of the sleep cycle and does not reappear in the back half. In addition, when you first lie down and then finally get up, wakefulness occurs at regular intervals at about four hours and six-hour points, but most sleepers do not fully wake up during those middle of the night times unless their sleep is disrupted. Light sleep phases punctuate the entire cycle even in normal sleep. By the way, if you are wondering about the accuracy of those consumer wearables, they are far better at measuring your sleep cycle than calories burned since there are fewer confounding variables affecting sleep. They do overestimate your sleep duration on average by about 24 minutes compared to a research level accelerometer and about 67 minutes compared to clinical polysomnography according to a 2015 study. However, most consumers find that to be adequate for their home and personal interest purposes.

Sleep Process Factors

- Process S and Process C

- DLMO: Dim Light Melatonin Onset

Now, we are going to discuss the two sleep process factors, which are Process S and Process C, as well as, dim light melatonin onset and the role of melatonin in the body.

Two-Process Sleep Model

- Process S

- Sleep Pressure

- Dependent on hours of wakefulness vs. hours of sleep

- Very high in the first phase

- Diminishes with sleep

- Process C

- ‘Circadian Pacemaker’

- Sleep/Wake rhythm

- Emerges at 12 weeks old

- Sleep preferences emerge

- DLMO begins to emerge 1-2 hours later

- ‘Zeitgebers’: light-dark, mealtimes, social activities