Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Insights Into Reaching And Teaching Teenagers, Part 1, presented by Tere Bowen-Irish, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to compare and contrast specific qualities of the developing teenage brain.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize how the Universal Model for Design can be a conduit towards goal development when treating teens.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify a variety of ways to connect with teens on their caseload, as well as be an integral part of helping them be successful in a school-based setting.

Introduction

Hello everyone. This is a subject that holds profound significance for me. With years of experience in my practice, I have observed a recurring pattern of discharging children aged approximately ten and beyond. The more I delve into the intricacies of their cognitive development and consider the specific diagnoses they carry, the more it underscores the importance of our availability for consultation. It is evident that we play a crucial role in aiding these individuals as they navigate the challenges of middle and high school.

Overview

- Here is an overview of the course in two parts:

- Explore today’s teenagers and behaviors common developmentally to teens

- Review new brain research

- Understand more about self-regulation and executive function

- Consider the application of strategies, techniques, modifications, and interventions via a Universal Design Model

Your presence here for the next two sessions is presumed to be rooted in your engagement with, proximity to, or connection with teenagers. I will provide an overview of the course, divided into two parts. Firstly, we will explore contemporary teenagers, examining the developmental behaviors commonly observed from ages 10 through 21 and beyond. This exploration will be complemented by a review of recent brain research pertaining to the teenage brain.

Additionally, we will delve into the understanding of self-regulation, prefrontal lobe activity, and executive function. Our objective is to consider various strategies, techniques, modifications, and interventions, aligning with the principles of the Universal Design Model. This model, frequently employed by educators, resonated with me as I sought a common language while working in classrooms. Comprising three key elements, we will thoroughly cover these components today. For those unfamiliar with UDL, I trust that this introduction will spark ideas on adapting or modifying your approach within the framework of this model.

Teenagers Need Support

- The teenage population in schools today needs therapists and other school-based personnel to support and nurture their development.

In my opinion, the teenage population requires the assistance of therapists and other school-based personnel for their support and developmental nurturing.

What are the characteristics of the teenagers we encounter in the 21st century? Think about this and jot down a few words. Reflect on the teenagers you know, those you treat, or teenagers in general to create a profile.

My goal today is for you to gain value, generate ideas addressing the characteristics you've noted that may disrupt learning, shift our perspective, and explore how to channel that energy positively.

Characteristics

- Disrespectful

- Emotional

- Not Accountable

- Scattered

- Unpredictable

- Impulsive

- Obstinate

- Seeks novelty

- Curious and questions everything

- Demanding

- Questioning

- Obsessed with certain things

- Cares only about peers

- Rejects adult intervention

Notable characteristics of teenagers include a discernible sense of disrespectfulness, an inclination towards heightened emotions, a tendency to evade accountability, and a demeanor that appears scattered, unpredictable, impulsive, and obstinate. Additionally, there is an observable inclination towards seeking novelty, coupled with a persistent curiosity that prompts questioning of established norms. This demographic often manifests demanding behaviors, shows an inclination towards obsession with certain interests, and tends to prioritize peer relationships over others.

Notably, there is a prevalent resistance to adult intervention. These characteristics find explanation in the ongoing brain research, offering insights into the intricate process adolescents use to shape their journey into adulthood. As our conversation progresses, I anticipate delving deeper into the nuanced dynamics.

Sean Covey’s Book: "The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens"

- Pinpoints bad habits of today's teens

- Reaction, blame on others

- Avoidance of goals, no future thinking

- Always view life in a “win-lose” situation

- Not listening when views are different

- Uncooperative, becoming more of an island

- Were these characteristics on your list?

Sean Covey's book, "The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens," addresses habits that resonate as enduring and pivotal. It identifies certain habits that may align with the characteristics we've discussed. These include reactionary tendencies, a proclivity for projecting blame onto others, a reluctance to set goals, marked avoidance, and limited future-oriented thinking. Another facet involves a predisposition towards win-lose situations, characterized by a somewhat black-and-white perspective.

Furthermore, issues may arise in terms of not actively listening when confronted with differing viewpoints, fostering an uncooperative demeanor, and adopting a tendency to become an island, distancing oneself from adults. It's important to note that in highlighting these aspects, the intention is not to cast a negative light on teenagers. Instead, the goal is to foster a deeper understanding of the underlying reasons for these behaviors. By unraveling these dynamics, we can pave the way for more meaningful connections with the teenage demographic.

Frances Jenson's Book: "The Teenage Brain"

- “The teen brain is only 80% of the way towards maturity…that 20% gap where the wiring is thinnest, is crucial and goes a long way toward explaining why teenagers behave in such puzzling ways…mood swings, irritability, impulsiveness and explosiveness.”

Frances Jensen's book sheds light on a crucial aspect - the prefrontal cortex - in understanding the intricacies of the teenage brain. It unveils that the teen brain is only 80% mature, despite their physical appearance resembling that of adults. This 20% gap signifies a thin wiring in the prefrontal cortex, contributing to behaviors that might seem puzzling.

The manifestations include heightened mood swings, irritability, impulsiveness, and explosiveness. These behaviors find their roots in the incomplete maturation of the prefrontal cortex. Current research indicates that full maturity is not attained until individuals are 25 to 27, with girls generally maturing faster than boys. This insight into the developmental timeline provides a nuanced perspective on the challenges and behaviors exhibited by teenagers.

- Jenson cites impulsiveness, risky behaviors, and inability to follow through on tasks as other signs and symptoms of frontal lobe immaturity.

- Dr. Daniel Siegel discusses the dopamine craving, without thought about consequences.

- He calls it “hyper rationality”- not impulsivity but rather seeking high arousal despite consequences.

- Taking risks…. results in many tragic stories…we have all heard them.

Frances Jensen's work also highlights impulsiveness, risky behaviors, and challenges in following through on tasks, all indicative of frontal lobe immaturity. These behaviors, including impulsivity, often stem from a desire for heightened arousal and a craving for dopamine.

Dr. Siegel introduces the concept of "hyper-rationality" in his book, challenging the conventional understanding of impulsivity. He describes it as a pursuit of high arousal, a sort of 'damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead' feeling, where consequences take a back seat. An illustrative example from his book involves a young woman knowingly taking the risk of bringing alcohol to a party at the principal's house. Despite being aware of the consequences, she perceived the novelty and thrill as worth the risk, showcasing the deliberate seeking of such experiences.

This perspective is emphasized in "Brainstorm," where Dr. Siegel explores the neurodevelopmental changes the teenage brain undergoes. Contrary to common attribution solely to hormones, these changes are more intricate, revealing that hormonal shifts alone do not account for the diverse spectrum of teenage behaviors.

Daniel Siegel's Book: Brainstorm

- The brain is going through a series of neuro-developmental changes that are not only related to hormonal shifts. Siegel uses the term “pruning.” As the teenager lets go of some past learning, their brain begins to remodel itself. He calls this “specialization.”

Dr. Siegel introduces the concept of "pruning" to describe the transformative process occurring in the teenage brain. As adolescents let go of some past learning, the brain undergoes a remodeling phase he refers to as "specialization." This process involves the brain shedding elements of knowledge acquired in elementary years, focusing on honing specific areas of interest.

In his books, Dr. Siegel illustrates how, during the elementary years, individuals acquire a broad range of knowledge, including basics like the ABCs and numerical concepts. However, as the brain matures, typically around 10, 11, and 12, it initiates a selective process, discarding no longer interesting or unused information.

This shift towards specialization signifies a transformation where individuals gravitate towards activities or subjects that align with their intrinsic interests. It marks a natural inclination to pursue what intrigues them, enabling the enjoyable exploration of classes and activities that align with their evolving passions and aspirations.

- That “specializing” suggests shifts and changes.

- What is interesting from a treatment point of view is the “use it or lose it principle.” If skills are not enhanced or practiced, they are lost. The good news is we can educate teens about these changes, like finding and acting on passions (e.g., pursuing interests, and learning new skills will stimulate brain growth). Myelin sheaths become more mature, and neuronal communication increases at a faster rate.

Dr. Siegel emphasizes that specialization entails significant shifts and changes in the teenage brain. Viewing it through the lens of a "use it or lose it" principle, teenagers' skills need active enhancement and practice to avoid being lost. The encouraging aspect is that we can stimulate their brain growth by educating teens about these ongoing brain changes and encouraging them to find and act on passions, pursue interests, and learn new skills.

Dr. Siegel employs the metaphor of a tree to illustrate this process: initial growth, addition of leaves and branches, and pruning. Just as a tree can lose leaves or entire branches, the teenage brain undergoes a similar selective process.

As an occupational therapist, the consideration extends to the leisure activities of teens in the 21st century, notably, the prevalence of gaming. Conversations about their interests may reveal limitations or adherence to outdated preferences. An example from my past involves a student diagnosed with autism who initially had a strong affinity for Thomas The Train. Over the years, we expanded this interest, transitioning to collecting old-fashioned trains, creating a train station model, and involving the family. This approach tapped into the concept of specialization, requiring the development of various skills, such as budgeting, online research, and participation in auctions. By guiding teens in making these shifts, we contribute to making their interests more socially acceptable and developmentally aligned.

Dr. Stuart Goldman of Psychiatric Education at Children’s Hospital in Boston

- “Teenagers are basically hard-wired to butt heads with their parents.” And, "Adolescence is a time of rapid change for kids both physically and cognitively," he explains. "It's the task of the teenager to fire their parents and then re-hire them years later, but as consultants rather than managers."

Dr. Stuart Goldman's perspective from Children's Hospital in Boston resonates powerfully: "Teenagers are hardwired to butt heads with their parents." He frames adolescence as a period of rapid physical and cognitive change, describing it as the teenager's task to "fire" their parents temporarily and then "rehire" them years later, but in a consultant role rather than a managerial one.

This dynamic is particularly pronounced in cases where teenagers have received special education services for an extended period. While parent involvement may remain high, the challenge lies in guiding parents to engage effectively in assisting their teenager's shifts toward interests that foster growth and development.

Understanding that the teenager's apparent rejection is an exploration of identity in relation to peers, parents, and the broader community becomes pivotal. By facilitating this shift in perspective, we can help parents navigate their evolving roles and support their teenagers in the transformative journey of self-discovery.

Dr. Siegel's Lecture: Specialization

I work with middle schoolers and teens, and I often share a video by Dr. Siegel, though unfortunately, I couldn't obtain permission to showcase it here. The video sparks numerous thoughts, ideas, and even dreams. Let me share how I leverage this in my work.

I have a student named Connor on my caseload at a school for emotionally disturbed or diagnosed kids who face challenges in mainstream education. When I initially met Connor, he exhibited strong oppositional defiance towards adults, questioning everything and resisting tasks. To connect with him, I brought my two dogs to school and discovered that walks with Connor and the dogs fostered a more relaxed environment, facilitating open discussions.

During these walks, Connor passionately shared his love for football, detailing his positions, exercise routines, strategies against opposing teams, and experiences on the field. Despite his enthusiasm for football, his teachers reported his reluctance to engage in math or writing tasks, leading to academic struggles.

Observing the light in Connor's eyes and the activation of his limbic system during our football discussions, I recognized an opportunity. I presented the idea of integrating football statistics into his academic work to the team. Based on his preferred teams, we devised math tasks involving addition, subtraction, and comparisons. The teacher skillfully incorporated writing assignments, such as biographies of football players throughout history, exploring the evolution of the sport and its impact on the brain.

This approach, centered around Connor's interests, stimulated his limbic system and led to improved attention and focus. I eventually stepped back, allowing the teachers to run with it, witnessing the transformative effect on Connor's academic engagement. This experience reaffirms the power of understanding and connecting with students personally, discovering who they truly are, and making meaningful connections that can profoundly impact their educational journey. I encourage you to explore the referenced video, as it may resonate with your experiences with students awaiting that connection to discover their true selves.

Basic Needs of Teenagers

- Good nutrition and adequate hydration

- Daily exercise

- Sound sleep

Let's look at the fundamental needs of a teenager, an aspect I frequently emphasize in my lectures throughout the year. Understanding these basics is crucial when working with students, as reiterated by brain research on learning.

One cornerstone is the recognition that healthy habits significantly influence student success. This encompasses essential elements such as ensuring they receive proper nutrition, maintain adequate hydration, engage in regular exercise, and obtain sufficient sleep. The impact of these factors on a student's overall well-being and performance cannot be overstated.

Sleep and Circadian Rhythms

The circadian rhythms of a teenager are different than a younger child.

- Teens tend to have later bedtimes.

- School hours often start earlier than elementary.

- They are often tired early in the day.

- Possibly, they are more available for learning later.

Notably, with teenagers, there's a unique consideration regarding circadian rhythms. Adolescent circadian rhythms differ from those of adults, and understanding these distinctions is vital for effective treatment and support. As we explore these basic needs, we gain insights into creating an environment that optimally nurtures a teenager's physical and cognitive development.

Teens often adopt later bedtimes compared to elementary students, leading to challenges when school hours commence early. It's a common observation that teenagers may feel fatigued early in the day, potentially impacting their readiness for learning. The reality is that they may be more receptive to learning later in the day.

Taking a local perspective and adopting a reflective approach, it becomes essential to consider what scheduling would be most effective for these teens. Unlike elementary kids who may benefit from an early start to enhance alertness, the situation for teenagers is different, especially when they have late bedtimes. Trying to engage them early in the morning, especially if they've had inadequate sleep, might prove challenging.

Recognizing these differences, some regions nationwide are reevaluating school start times. Initiatives involve incorporating physical exercise before school to invigorate the system and educational efforts to emphasize the importance of sleep, nutrition, and hygiene for overall well-being. This approach aligns with the understanding that catering to the unique needs of teenagers contributes to creating a conducive environment for effective learning.

Guare and Dawson's Book: "Smart But Scattered"

- “Many teens will have wake-up issues…from a biological perspective the wake-sleep clock in adolescents’ bodies changes so that they are naturally awake later, but still need a good night’s sleep.”

Quoting from the book "Smart but Scattered," it highlights a common issue among many teens: wake-up issues. The biological perspective elucidates that the wake-sleep clock in adolescents undergoes a natural shift, making them naturally more awake later in the day while still requiring a good night's sleep. This biological shift can result in teens facing challenges related to insufficient sleep.

Understanding the impact of inadequate sleep is crucial, as we all experience chaos and cognitive fuzziness when deprived of a good night's sleep. It becomes an educational opportunity to discuss sleep habits and hygiene with teens, addressing how they spend their leisure time before bedtime.

While some might argue that addressing sleep is beyond the scope of a school-based therapist, the broader perspective suggests otherwise. A comprehensive understanding of the 24-hour clock equips therapists to educate not only the students but also the teachers. Therapists can contribute to a more informed and supportive educational environment by grasping the challenges teens face outside of school hours.

ADHD and Sleep: Becker et al., 2019

- The Becker et al. study “provides clear experimental evidence that how much teens (that are diagnosed with ADHD) sleep has a significant impact on their attention and behavior. An additional 1.6 hours per night - the average difference in sleep during restriction and extension weeks - had impacts that were discernible to parents and, for some outcomes, to teens themselves.”

Becker underscores the crucial link between sleep patterns and attention and behavior in teens diagnosed with ADHD. Clear experimental evidence highlights the significant impact of lack of sleep on their cognitive functions. The proposal that an additional 1.6 hours of sleep per night could yield discernible improvements for both parents and teens is a noteworthy observation.

What makes this intervention particularly valuable is that it's a cost-free endeavor. It raises awareness and encourages teens to aim for eight to nine hours of sleep each night. The potential outcomes extend beyond mere parental observation, influencing the teens' well-being.

While it's possible that parents might be hesitant to address sleep patterns, especially if they're not fully aware of the benefits, providing education on the subject becomes pivotal. Empowering teens with the knowledge to make informed choices about their sleep habits aligns with the broader goal of supporting their efforts to improve overall well-being.

- “What is surprising, however, is that that assessing sleep and intervening where indicated is not done for many youth with ADHD. While the impact of increasing sleep did not have as large an effect, on average, as medication, there is no reason not to include sleep assessment and intervention for nearly all youth with ADHD. There is virtually no cost to doing this, and it can make a difference.”

"What is surprising, however, is that assessing sleep and intervening where indicated is not done for youth with ADHD. While increasing sleep did not have this large effect, on average, as medication, there is no reason not to include sleep assessment and intervention. It's virtually no cost to do this and can make a difference."

Other Health Concerns

- Concerns about certain dyes and glucose levels that may affect hyperactivity

- Skin conditions due to poor health, food choices, processed foods

- Rise in sports injuries

- Irregular patterns can also affect creativity and problem-solving, and cause forgetfulness

- Obesity rising in our youth as well as inactivity

- High blood pressure due to sodium intake

- Some kids with poor vision may display hyperactivity

- Irregular hours may play a role in mental health, juvenile delinquency, and violence

- A lack of regular exercise can result in an inability to blow off steam

Various health concerns, particularly nutritional ones, affect teens' well-being. In Europe, the outlawing of certain dyes, such as red and yellow, stems from findings that link them to affecting the nervous system, potentially leading to hyperactive-like behaviors.

Nutritional choices also play a role in skin conditions, a topic the school nurse often addresses with teens, linking food choices to acne. Sports injuries are on the rise, influenced not only by risky behaviors but also by fatigue, affecting their physical condition and focus.

Irregular sleep patterns contribute to issues like forgetfulness, disorganization, and difficulty turning in homework, concerns often conveyed by teachers. Obesity and high blood pressure are additional health challenges prevalent among teenagers.

An interesting perspective is the correlation between hyperactivity and visual skills. Deteriorating vision might prompt hyperactive behaviors as individuals attempt to compensate by getting closer to what they're working on or struggle to focus due to blurriness.

Moreover, irregular hours, coupled with a lack of regular exercise, can be linked to juvenile delinquency and violence. The absence of a consistent outlet for blowing off steam, through regular exercise, can impact teens who may require such activities for their overall well-being. Addressing these health considerations holistically becomes essential in supporting teenagers' physical and mental health.

John Ratey's Book: "Spark"

- "Spark" was published in 2008. It continues to be a source in proving that the connection between exercise and brain functioning helps reduce stress, enhances focus, and directly affects performance in academics. He also has written the book Go Wild, and ADHD 2.0.

The book authored by John Ratey in 2008 has left a lasting impact, notably illustrated by a significant experiment conducted in Urbana, Illinois. Several schools have embraced the principles outlined in the book, and a particular high school stands out for implementing a morning routine where students either run or walk a mile or participate in gymnastic activities before the commencement of regular classes. This initiative proved remarkably successful, leading to a substantial increase in state testing scores for the school, even though its curriculum remained consistent with other schools in Illinois.

John Ratey has continued his contributions to the field with subsequent books such as "Go Wild" and "ADHD 2.0." The core idea emphasizes the positive influence of movement on key aspects like stamina, focus, and endurance. As an occupational therapist, this aligns with your belief in the significant impact of physical activity on overall well-being. The success of these initiatives underscores the potential transformative effects of incorporating regular physical activity into daily routines, not only for academic performance but also for the holistic development of students.

Lengel and Kuczala's Book: Kinesthetic Classroom

- “When the body is inactive for 20 minutes or longer, there is a decline in neuronal communication.”

- Signs of focus loss: Lack of sleep may show itself this way!

- Examples: Staring, humming, acting out, unfinished tasks, interrupting, talking to others, doodling, fidgeting, attention-getting behaviors, poor direction following

The book "Kinesthetic Classroom" by Langel and Kuczala, a topic introduced by one of my colleagues, sheds light on the importance of movement in the learning environment. This perspective has proven valuable during my classroom observations, particularly in high school settings with block scheduling, where extended periods of sitting can lead to a decline in neuronal communication after 20 minutes of inactivity. Signs of decreased focus, often attributed to lack of sleep, include behaviors such as staring, humming, acting out, unfinished tasks, interrupting, talking to others, and fidgeting.

Brain Break Video

Please participate, if you would, and just notice how you're feeling. So everyone should stand up, and if you can't stand up, you can do these seated. All right, so let's start with simply windshield wipers. So hands above your head, and we're just going to cross, one, two, three, you can switch hand in front, hand in back, six, seven, eight, nine, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. Good, hands come down. Hands together in front of you, thumbs hooked. Now you're going to breathe in and open your arms, breathe in, and put your palms together, come down. Hook thumbs again, breathe in, palms together and down. Hook thumbs, last one, breathe in, and down. Shake one arm, just keep shaking it, don't shake the other. Just shake, shake, shake, shake that arm, keep it shaken from the shoulder to the wrist, to the elbow and back again. And stop. Close your eyes. And notice the difference in sensation between the one arm that wasn't shook up and the other. Now do the other side. Shake, shake, shake, shake, shake, shake, shake, shake, shake, and stop. And again, notice the one you shook. You may feel tingling, you may feel warmth, you may feel coolness, you may feel vibration. Excellent. Okay, last one, hands in front, palms up. Breathing in. Pull your hands in, breathing out, push away. Now let's think about something that's tough today. Breathing in, push it away, breathing in, push it away. So I've got a lot of deadlines I have to meet, need the energy to deal with that, push to get it done. In and push. And in, last one, push.

Here is the cognitive overlay for this. I tell them, "Now your body is ready to sit long and strong for the rest of the class." When I do things like this, I talk to them about connecting mind and body to help with focus. What I notice is if I do this regularly and routinely with the teacher doing it with me, and the teacher does it when I'm not there, then it becomes part of the habituation in the classroom. It alerts the body as a tool to sit down to work for both younger and older kids.

Think about what changes you feel. Are you listening more? Do you feel your posture's better? Are you able to attend better? Was that kind of a way to erase a little chaos in your brain and then reboot, if you will?

Tech and Sleep

- Melatonin production, which helps the body attain a circadian rhythm, is affected by the glow of a phone screen in the dark. The circadian rhythm helps the body adapt to a day/night cycle. If there is a decline in melatonin production, it affects the individual’s sleeping cycle.

Most high school and middle school students need adequate sleep for stimulation of brain cells and to handle emotions better. When we give that education about their growth, we could preempt some of those exercises by saying, "You still may be pretty sleepy, especially if you went to bed late last night."

Incorporating such exercises in the classroom helps students stay focused, improve posture, and enhance attention. Connecting mind and body becomes a habit, empowering students to use their bodies as tools for optimal learning.

Additionally, addressing the importance of adequate sleep in the context of brain cell stimulation and emotional regulation is crucial. By providing education about growth-related changes and offering preemptive exercises, especially after insufficient sleep, teachers can contribute to better stress and anxiety management among students.

I find it fascinating to consider how it affects melatonin production and circadian rhythms. Becoming a new grandmother has brought this issue to my attention, especially as I observe my infant granddaughter struggling to adapt to a day and night cycle.

It is concerning to contemplate the potential decline in melatonin production for teenagers who habitually keep their phones on in the middle of the night. This behavior disrupts their sleeping cycle and affects their alertness and readiness to learn.

I'm increasingly aware of the importance of addressing these issues among parents, caregivers, and educators. Encouraging healthy sleep habits, such as establishing a tech-free period before bedtime, becomes vital to ensuring the overall well-being of individuals, from infants to teenagers.

In the context of the 21st century, where technology is deeply ingrained in our lives, there's a need to raise awareness about the potential consequences of excessive tech use on sleep quality. Educating the younger generation on striking a balance between technology and sleep is crucial as we navigate the challenges of the digital age.

- Text messages or social media alerts disrupt sleep if left on a nightstand or in bed. A text message or a social media alert can wake you during sleep. A recent study found that 22% of respondents reported having the cell phone ringer turned on and resting on the nightstand at night. Even worse, 10% of participants in the survey said the phone woke them up over the last week.

The impact of text messages and social media alerts on sleep is evident, especially when devices are left on the nightstand. The study reveals that 22% of respondents have their cell phone ringers turned on and resting on the nightstand, with 10% reporting that their phones woke them up over the last week. This constant presence of the phone poses a challenge for individuals seeking rest.

In my interactions with teenagers, I often prompt them to reflect on quiet moments and encourage them to put down their devices without constant returns. It's essential to initiate conversations about how this constant connection to technology affects their sleep patterns and, consequently, their overall performance during the day. Understanding the importance of disconnecting and creating boundaries with technology is crucial for promoting better sleep hygiene and overall well-being.

- Using a tech device prior to sleep causes stimulus to the brain. The brain is then challenged to relax. Listening to a book, taking a bath, dimming lights, and music can all contribute to a soothing bedtime routine that helps aid sleep.

- Computers, cell phones, and tablets stimulate the brain more than television or radio. Constant interaction with these can affect memory, focus, rational decision-making, and settling down.

The impact of using tech devices before bedtime on brain stimulation is a significant consideration. Such devices can challenge the brain's ability to relax when turned off, potentially affecting sleep quality. In my research, I discovered that engaging in activities like listening to a book, taking a bath, dimming lights, and incorporating music can contribute to a more soothing bedtime routine. Notably, taking a bath has the added benefit of changing core temperature and naturally releasing melatonin.

It's interesting to note that while computers, cell phones, and tablets can stimulate the brain, they do so more intensely than a television or a radio. This constant interaction with technology can affect memory, focus, and decision-making as individuals settle at night. Though not explicitly labeled as addiction, the repetitive nature of checking phones day after day, night after night, especially among teens, borders on such behavior. The impulsivity in wanting to maintain that connection with peers through constant phone use adds another layer to the potential impact on overall well-being. Recognizing these patterns is crucial for fostering a healthier relationship with technology and promoting better sleep habits.

- If tech is always in our pocket or by our side, there is a need to check it, as we may miss something. This creates restlessness, and focus, concentration, and endurance for other tasks as sleep can be compromised.

The constant accessibility of tech devices, often kept in our pockets or by our side, creates a strong impulse to check them regularly. The fear of missing out on something important can lead to restlessness and compromise various aspects of well-being, including focus, concentration, endurance for tasks, and even sleep.

I have a nephew who addresses this issue in his classroom in San Francisco by having a designated basket for students to place their phones can help create a tech-free zone, allowing them to focus on the educational environment. However, the complexities arise for students who need to keep their phones close due to concerns about safety and family well-being. In such cases, individuals may remain on high alert, impacting their ability to fully engage in classroom activities.

I know another teacher who utilizes a similar strategy of collecting phones in a basket but incorporates technology during designated times for academic purposes. This approach aims to shift the focus of tech usage from personal lives to academic applications, promoting a more controlled and purposeful integration of technology in the educational setting.

Balancing technology's convenience and potential distractions is an ongoing challenge, especially in educational environments. Finding ways to make tech more applicable to academics and establishing clear boundaries can contribute to a healthier relationship with these devices in personal and educational contexts.

- Technology is here to stay.

Tech is here to stay, and it can be both positive and negative. The average person checks their phone 144 times a day, which is concerning.

- The 21st century brings technology to the classroom, but it also has a 24/7 effect.

The 21st century brings technology to the classroom, and it can be a nuisance and a blessing all at the same time.

Positive Influences

- Provides many possibilities for students of all levels to express themselves and communicate more effectively

- Offers a myriad of new ideas, both visual and interactive

- Adds to supportive collaboration among students and contributes to teamwork

- Alternative ways of learning for both individuals and groups

The positive influences that technology can provide in education are indeed significant. It offers diverse possibilities for students of varying abilities to express their thoughts and communicate effectively. Technology's role in visually and interactively stimulating creativity is evident, contributing to supportive collaboration and teamwork among students.

In the context of research, using technology, such as Chromebooks, allows students to access and explore the same information simultaneously. This collaborative approach to learning enhances the effectiveness of group work and offers alternative methods for individual and collective learning experiences. The integration of tech as an integral part of the learning process can often motivate teenagers to actively participate.

However, it's crucial, as you mentioned, to consider the development of teamwork skills. Teachers and therapists play a pivotal role in guiding students on how to effectively work together using technology. Defining clear goals and strategies for collaborative projects ensures that tech use aligns with educational objectives.

One teacher I know used technology to teach vocabulary. The interactive nature of students using thumbs up to signal unfamiliar words, searching for definitions, and integrating new vocabulary into their writing demonstrates effective tech use and enhances the overall learning experience. Additionally, incorporating auditory input for spelling and integrating tech seamlessly into writing assignments showcases technology's versatility and positive impact on the learning process.

- Opportunities for specific tutoring

- Opportunity for creativity in project-oriented curriculum

- Daily use, aiding in the refinement of mastering technology and its application to education

- Adds novelty and entertainment to learning processes

- Improves overall knowledge of facts, information, and instructions

Specific tutoring opportunities emerge in educational possibilities, such as the innovative concept of a flipped classroom. This approach involves teachers assigning work outside the classroom via YouTube videos and online materials. For instance, if students are studying endangered species, they choose a species, and the teacher provides relevant YouTube videos and assignments for independent exploration outside school hours.

Upon returning to school, the teacher engages in individual discussions with each student, assuming they have engaged with the assigned material. While organizing a flipped classroom can be time-consuming, its benefits are notable. In a classroom I encountered, around 20% of students initially struggled with completing assignments at home. In response, the teacher implemented a strategy, having those students catch up in the classroom, wearing headphones to watch the assigned content, and then completing the homework independently the next day. Most students, drawn to the appeal of YouTube videos, embraced the approach, fostering a unique and engaging learning environment.

The project-oriented curriculum further expands opportunities for technology integration. Beyond daily use, technology aids in refining and mastering educational concepts. Additionally, it introduces novelty and entertainment, contributing to acquiring knowledge and information. While acknowledging the positive influences of technology in education, it's essential to advocate for moderation. The goal is not constant tech use but a balanced approach that enhances learning experiences. Leveraging technology in moderation can open the limbic system of a teenager, providing a valuable avenue for engagement and learning.

Current Research: Pew Research Center 2022

- According to a survey by Pew Research Center in 2022, 95% of American teenagers aged 13-17 use the internet daily. The same survey also found that 67% of teens use TikTok, which has become one of teenagers' most popular social media platforms. In contrast, the percentage of teens who use Facebook has dropped from 71% in 2014-15 to 32% in 2022. YouTube is the most widely used online platform among teens, with 95% of them using it. Instagram and Snapchat are also popular among teenagers, with about six in ten teens using them.

The survey also found that 97% of teens have access to digital devices such as smartphones, 90% have access to desktop or laptop computers, and 80% have access to gaming consoles. The study shows that there has been an increase in daily teen internet users from 92% in 2014-15 to 97% in 2022. Additionally, the percentage of teens who use the internet almost constantly has increased from 24% in 2014-15 to 46% in 2022.

Another article by The Edvocate states that, on average, teenagers spend roughly nine hours per day on the internet, not including time spent on homework. It also mentions that two-thirds of teens have access to internet-capable mobile devices (aka smartphones) and that 90% of teens have used social media.

The provided facts shed light on the internet's pervasive influence and various social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and YouTube on the teenage population. The data reveals a significant increase in teenagers' access to these devices compared to 2014-15, indicating a notable shift in their digital engagement.

One striking statistic is that, on average, teenagers spend approximately nine hours per day on the Internet, excluding time dedicated to homework. This staggering amount of screen time raises concerns about the potential effects on their cognitive development, particularly in brain pruning. Understanding the intricacies of a teenager's daily routine becomes crucial in identifying what aspects of their cognitive function are being pruned or specialized due to extensive internet use.

The emphasis on the importance of occupational therapists engaging with teenagers in school settings is a compelling argument. Occupational therapists can bring a unique perspective to teachers, offering insights into effectively reaching and teaching these adolescents. This involvement addresses the immediate concerns of excessive internet usage and provides a platform for teenagers to express themselves and develop a deeper understanding of their identities.

The mention of specific apps for focusing, organization, planning, and time management underscores the potential role of technology in mitigating some of the challenges associated with prolonged internet use. Exploring these apps could offer practical solutions to enhance teenagers' engagement and productivity while promoting a healthier relationship with technology.

Apps

- How can we make technology work for us versus against us…. What are you already doing? Many teachers feel that it causes a more distracted student…

Here are some apps that may help rather than be a negative use of technology

30/30 Binary Hammer has a visual timer and color-coding

Lotus Bud helps with task initiation with a random bell alarm

MyHomework student planner by Rodrigo Neri helps with planning and prioritizing

inClass: organization and planning

Connected mind helps with mind mapping

LucidChart for Education for organization, planning, and memory

Strict Workflow for productivity, focus, and time on task

Alarmed Reminders + Timers by Yoctoville has a nag feature!

Tech Strategies and Approaches

- Tech can help us to build strategies and approaches to connect with our students.

Establishing connections with teenagers requires a nuanced approach, and drawing parallels with the methods used in working with elementary school children can be insightful. In elementary school settings, therapists often utilize conduits or toys to create a bridge for engagement. The focus is not immediately on specific therapeutic goals but on building a connection through shared activities.

When working with teenagers, it's essential to recognize that the dynamics may differ, and traditional methods might need adjustment. Therapists might feel challenged finding effective ways to connect with teens, especially considering the potential absence of toys or structured activities.

However, numerous successful strategies can be employed to establish meaningful connections with teenagers. One approach involves integrating their interests and hobbies into the therapeutic process. Understanding their preferences, whether related to sports, music, art, or other activities, can provide a valuable entry point for engagement. This approach lets therapists connect with teens personally and create open communication spaces.

Another effective strategy is adopting a strengths-based approach. Rather than focusing solely on challenges or deficits, recognizing and leveraging teenagers' strengths and positive qualities can foster a more positive and collaborative therapeutic relationship.

The key is approaching teens with genuine curiosity, actively listening to their experiences, and adapting therapeutic strategies to align with their unique personalities and interests. Therapists can build connections beyond therapeutic goals by creating a comfortable and non-judgmental space, allowing for a more holistic and impactful intervention.

Jenson and Snider's Book: "Turnaround Tools for the Teenage Brain"

- Eric Jenson and Carol Snider, from their book, "Turnaround Tools for the Teenage Brain," say…

- “Underperformance does not determine destiny…”

- “Destiny is determined by 30-40% genes and 60-70% environmental factors/gene environmental interactions.”

- “Brains, IQs, and attitudes can change…”

- “If you have the will and the skill, you can make significant and lasting differences in student’s lives.”

In my work with teenagers facing challenging circumstances, I often engage in conversations about the malleability of destiny. I convey that while a portion of one's life may be determined (30-40%), environmental factors and personal choices significantly influence overall well-being. Many of the teens I work with come from tough situations and dispelling the notion that their current academic struggles dictate their future is paramount.

I draw upon the evolving understanding of the brain to illustrate the potential for growth and change. Emphasizing the importance of positive connections and a sense of curiosity, I strive to instill hope and encourage these teens to envision a future beyond their immediate challenges.

Reflecting on my journey into occupational therapy, I recall the impactful mentorship of Ruth Edmunds, an occupational therapist in a nursing home. Shadowing her exposed me to the transformative power of occupational therapy and inspired my career path. Ruth's ability to integrate me into her work, explain complex conditions, and express hope for her clients left a lasting impression.

Recognizing the crucial role of mentors, I advocate for therapists to become mentors for teenagers. By actively engaging with them, therapists can create positive influences that help teens discover their strengths and aspirations. This approach builds trust, curiosity, and connection beyond immediate challenges.

The narrative further explores personal experiences with influential high school teachers, such as Mr. Meyer, whose engaging lectures made history come alive. This prompts a reflection on the current state of high school experiences and the need for fostering environments where students genuinely enjoy learning.

Acknowledging the challenges faced by teenagers on caseloads with long-term diagnoses, I encourage therapists to move beyond the consult model. Recognizing the ongoing development of their prefrontal lobes and brain pruning, therapists should focus on stimulating and encouraging skill development. This may involve tweaking existing activities to align with individual interests and abilities.

I work with a 16-year-old girl on the spectrum who enjoys drawing and writing notes to teachers each week. Her unique talents are a starting point for collaborative brainstorming within the team, aiming to expand and leverage her skills for future opportunities. Could she do something with graphic art on the computer? Or, can she make note cards, and sell them at our quarterly craft sales? When we begin to think about how we can expand their needs, it may end up being that we need to tweak what's already there. She loves writing to me and giving me pictures of my dogs, Bear and Penny, who are canine citizens in our school. She is already specializing, and we need to support this.

- Who influenced you as a teen?

- How did they treat you?

- What characteristics did they possess that made you feel accepted, empowered, safe, and able?

These are important questions to ask ourselves so that we can then treat these kids.

- Jenson and Snider also discuss some issues that we may not consider:

- What is the family’s attitude toward school?

- The effort is not relevant if the task is not challenging or interesting…

- Students may be more available if you listen to their dreams and figure out ways of connecting academic demands to those dreams.

- Cognitive capacity can be changed through teaching.

- Simple, short-term goals will help with focus.

- Consider teaching and modeling strategies.

Jenson and Snider discussed some issues we may not always consider when treating teens. Students may be more available if you spend more time listening to their dreams and helping them connect their academic demands to those dreams, similar to what I did with Connor. And so, as we begin to think about their cognitive capacity, and build short-term goals with them to help them focus, we have to consider all teaching and modeling strategies.

Conversation Starters

- OK, in 5 years, you will be 21

- Where do you see yourself?

- Working?

- Living?

- And with whom?

- Facilitating the dream…can create the bridge towards adulthood

I often initiate conversations with the teens I work with by posing a question that sparks their future aspirations. I ask them to envision where they see themselves in five years when they turn 21. It's a seemingly simple question, but the responses I get are often insightful. They might talk about their desired workplace, like Dunkin' Donuts or Market Basket, or express a wish to live independently.

As we delve into these discussions, some teens share their frustrations when asked if they are treated like kids while being expected to act like adults. This observation often resonates with them, and we explore how they can demonstrate to adults that they are actively building the bridge to adulthood.

I worked with a teen named Donnie, who expressed a passion for working on old cars during our interview. He traced this interest to his grandpa's barn, where he would tinker with an old car. Despite his grandpa being gone, Donnie continued to explore this passion through online research and discussions about classic cars from the '70s. Together, we found local places where people work on old cars, and he eventually secured a volunteer position that later turned into a part-time summer job.

The key takeaway from these conversations is the importance of delving deep into teens' interests, whether drawing, cars, or playing the guitar. Exploring their passions can uncover opportunities for personal and skill development, fostering a sense of purpose and direction in their lives.

Emmeline Zhao: Why Identity and Emotion Are Central to Motivating the Teen Brain

- “A window of formative brain development …between the ages of 9-13 and likely through the teenage years.” She quotes Ronald Dahl from Berkley…”This is a flexible period for goal engagement, and the main part of what’s underneath what we think about setting goals in conscious ways – the bottom-up based pull to feel motivated towards things.”

- Co-active goal making

The formative brain development window between ages 9 and 13, extending into the teenage years, presents a flexible period for goal engagement. Donnie's story exemplifies exploring underlying passions during this crucial developmental phase and setting conscious goals.

During my own journey, I discovered my interest in occupational therapy (OT) and decided to volunteer with Ruth Edmunds at the end of my junior year in high school. Continuing the volunteer work throughout my senior year, Ruth offered me a job for the summer before I went to college.

This narrative highlights the bottom-up approach to motivation, where discovering and nurturing personal passions becomes the driving force. By recognizing and fostering these passions, individuals can build a foundation for setting and achieving goals and creating personal and professional development pathways.

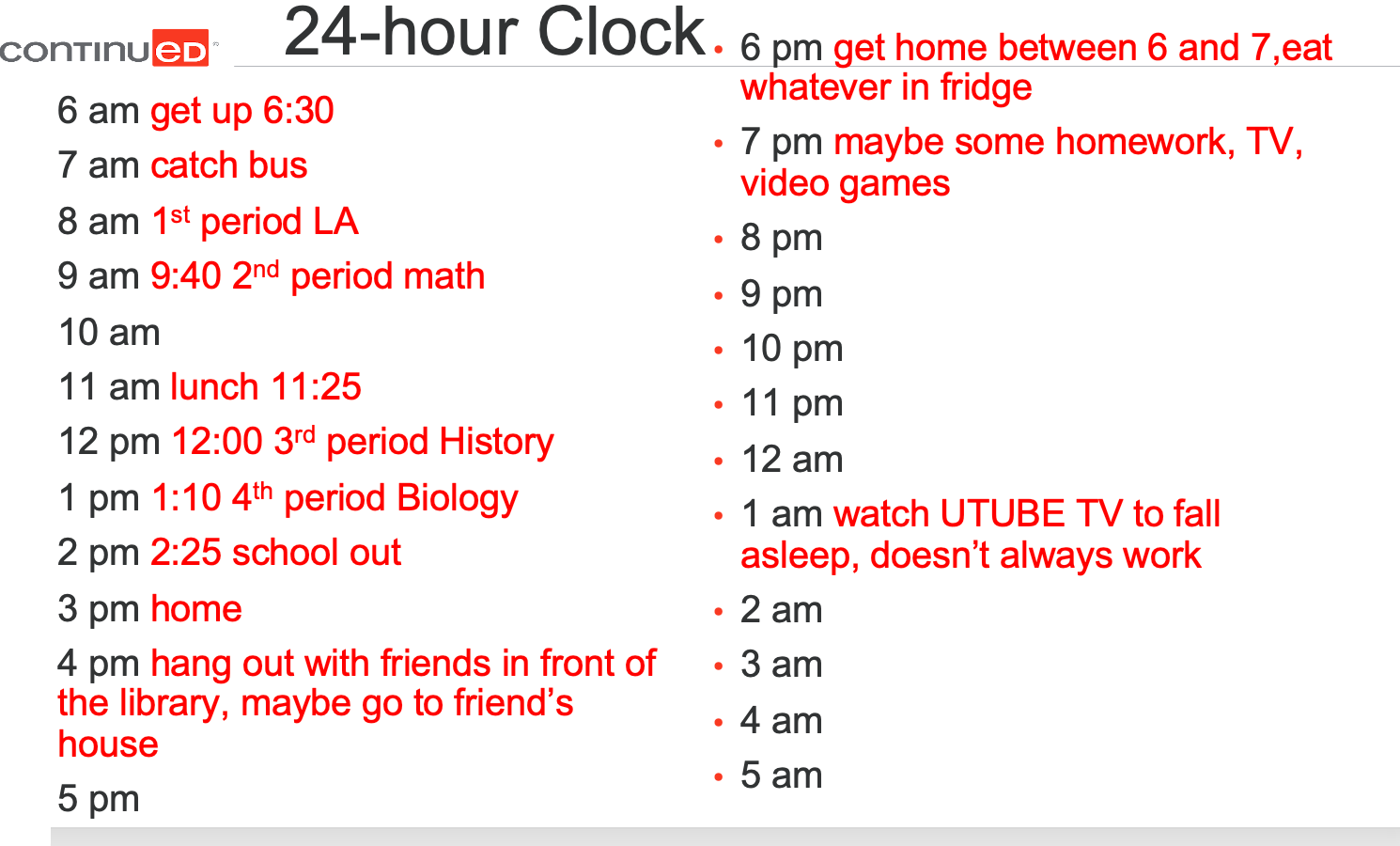

24-Hour Clock

In your handouts, there is a 24-hour clock form. This may be a conduit towards understanding your student's day. Here's a 24-hour clock sample in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A 24-hour clock sample.

When engaging with students, a valuable approach I use is to have them share their typical 24-hour day with me. I take on the task of writing down their schedule, ensuring that writing challenges don't hinder the expression of their thoughts. An example might include waking up at 6:30 AM, catching the bus at 7:00 AM, attending language arts (LA) at 9:00 AM, and math at 10:00 AM.

As I dig into the details, I inquire about their morning routine - whether they eat breakfast, shower, or how they choose their clothes. This allows me to uncover more about their daily life in a curious yet respectful manner. Exploring their feelings about classes, homework habits, and participation offers insights into their academic experience.

Beyond the school day, understanding their activities between 3:00 PM and 4:00 PM provides a glimpse into their after-school life. Some students may have responsibilities like babysitting siblings, while others might spend time with friends or engage in specific rituals. I comprehensively understand their daily life by inquiring about family gatherings, meal routines, and how they spend their evenings.

When discussing sleep, I explore bedtime rituals, the ease of falling asleep, and any disruptions during the night. This approach allows me to uncover valuable information about their routines, habits, and challenges, providing a holistic view of their daily experiences.

- Do you eat breakfast? Drink water during the day? Eat lunch? Ever sit down at home for dinner? Can you cook?

- On a scale of 1-10, how awake are you? 1st period, 2nd, 3rd, 4th?

- Which class do you like best, and why? Which teacher do you like best? What characteristics does that teacher have? Any friends in your classes?

- Is it hard to fall asleep? Stay asleep? Do you make up sleep on weekends?

- What are the most challenging parts of your day?

- If you could change anything about your day?

In addition to the basic questions about their daily schedule, I delve deeper into various aspects of their lives to gain a more comprehensive understanding. Questions like whether they drink water during the day, if they eat lunch, or if they can cook provide insights into their daily habits. A scale of 1 to 10 to gauge their alertness in different periods helps identify when they feel most engaged or challenged.

I explore their preferences in classes and teachers, aiming to understand the characteristics they appreciate in an educator. The influence of peers on their attendance in a class is another critical aspect to consider. Talking about sleep patterns, such as difficulty falling asleep or compensating on weekends, provides information about their overall well-being.

Two significant questions involve identifying the most challenging part of their day and asking them what they would change if given the opportunity. The responses to these questions can range from familial challenges to academic stress or a desire for more social time. Understanding their weekly schedule helps uncover potential sources of stress and overextension, especially among high-achieving students.

Parents' values and expectations regarding education contribute to the overall picture, as students often feel the pressure to meet certain academic standards. Exploring their desires for change sheds light on their priorities, with many expressing a wish for more social or downtime.

When guiding them on time management, it's crucial to recognize the need to break habits gradually. Creating new habits and helping them organize their time involves fostering small, manageable changes rather than drastic shifts. This approach ensures a more sustainable adjustment to their routines.

- More things to analyze

- Nutrition in general

- Sleep

- Exercise

- Social connections

- Leisure pursuits

- Community connections

- Schoolwork

- Getting adequate sleep and exercise?

- What’s the source of social? In person? On internet?

- Passions, hobbies?

- Church, clubs, teams?

- Can they balance school and work?

- What gets in the way?

When conducting a 24-hour clock assessment, I consider a holistic view of a student's life, encompassing various dimensions. This includes examining their nutrition, sleep patterns, exercise routines, social connections, leisure activities, community involvement, and school-related aspects. I evaluate whether their basic needs are being adequately met and explore the nature of their social interactions, whether in-person or internet-based.

Assessing their involvement in clubs, teams, or other school activities is crucial, as it provides insights into their social dynamics. Encountering difficulties in joining existing groups, such as cliques in clubs or teams, is not uncommon. In such cases, strategic planning, as demonstrated with the girl interested in drama, can help students navigate potential challenges and integrate successfully.

The balance between school and work and understanding their approach to these responsibilities sheds light on their overall life management. Recognizing potential obstacles to a smooth flow in their daily lives is essential. Factors such as tension, readiness to quit school, or other underlying issues may influence their behaviors and choices.

The adolescent brain's ongoing pruning and specialization contribute to the diversity of teenage behaviors. Understanding this neurological aspect helps contextualize their actions and behaviors in the broader framework of their lives.

Sue Fino: Geographic Metaphor

- What are your fields?

- What are your mountains?

- What are your hills?

- I add pinnacles.

- As OTs, we look at the whole person. Is anyone else on the team doing this?

Years ago, I attended a lecture by Sue Fino. It resonated with me that she used this technique to get to know her students.

Figure 2. An example of the geographic metaphor.

Using the analogy of geography, specifically fields, hills, mountains, and pinnacles, to understand a student's life is a brilliant approach. Sue, the learning disability specialist, initiated discussions with students about the fields in their lives - areas that come easily to them. This could encompass academic strengths or positive aspects of their personal lives, providing a foundation for understanding their strengths and preferences.

Moving on to hills, the challenges that students can navigate successfully open up conversations about academic difficulties and strategies they employ to overcome them. It acknowledges their resilience and problem-solving skills.

The mountain discussion looks into the toughest aspects of school and home life. This phase encourages frankness and openness, allowing students to express their genuine struggles and concerns. Understanding these mountains is crucial for providing targeted support.

Adding the concept of pinnacles, exploring where students envision themselves or their aspirations, is a forward-looking approach. This question taps into their dreams, aspirations, and future goals. Addressing these aspirations can guide interventions and support, aligning them with the student's vision for their future.

This holistic approach helps occupational therapists comprehensively understand the student and provides valuable insights for the entire team. In the often fast-paced academic environment, engaging with students personally can be a game-changer in preventing issues like dropout or lack of graduation. It adds a layer of personalization and empathy to academic support, fostering a collaborative and supportive team dynamic.

Eric Jenson's Book: "Teaching with the Brain in Mind"

- Let’s Consider the brain’s capacity from a developmental level…

- Direct instruction for new content time frames:

- Grades 6-12 have 15-18 minutes

- Adults don’t vary much…have 18-20 minutes

The insight from Eric Jensen's "Teaching with the Brain in Mind" highlights the limited attention span for new content in grades 6 through 12, ranging from 15 to 20 minutes. This emphasizes incorporating variety and engagement strategies to keep the brain active and attentive during learning sessions.

Your approach of changing ideas, altering tone, and presenting information differently aligns with the understanding that such variations can enhance cognitive engagement. Acknowledging the brain's capacity for sustained attention underscores the need for educators to adopt diverse teaching methods to cater to different learning styles and optimize information retention.

Considering the limitations in attention span, it becomes crucial for teachers to explore alternative ways of presenting concepts beyond traditional methods. This might involve incorporating visual aids, interactive activities, or discussions to keep the learning experience dynamic and capture the students' interest.

Your awareness of these cognitive principles and commitment to incorporating movement breaks and varied presentation styles reflect a student-centered approach that recognizes and respects the brain's natural learning processes.

Brain Break Video 2

Stand up please. All right. So what I want you to do here, these are called sliders, you're going to put one hand on the top of your shoulder, and you're going to breathe in, and bring it back, breathe out. And in. And out. And in. And out. Now do the other side. Breathe in. And out. Breathe in. And out. Breathe in. And out. And here's another one that includes rhythm, it's called heart rock. So you're going to lift one foot up as you lean to the opposite side, and just rock back and forth. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, and 10. Final activity. Arm up, arm out, fingers down, fingers up, turn, in, pull. Other arm up, and out, fingers down, fingers up, turn, in, and pull. Both arms up, deep breath in, deep breath out, fingers down, fingers up, turn, in, pull.

Hopefully, this will get you through to the end of this course.

In my role at a high school, I collaborated with John, the science teacher, to explore the resilience of an egg wrapping when dropped from 12 feet. In previous years, John had approached this experiment by providing individual students with various materials to choose from. However, recognizing the dynamics of our classroom, we decided to implement a dyadic approach, pairing students together to collaboratively design a wrapping that would prevent the egg from breaking upon impact.

To facilitate this collaborative effort, we set up workstations with long tables, each accommodating four students. The paired students across from each other collaborated on constructing their egg protection devices using materials such as boxes, tissue paper, crate paper, packing chips, packing bubbles, scotch tape, and pieces of wood. This shift to dyadic work revealed a noteworthy change in the students' approach. Unlike the previous individualistic method, there was a remarkable absence of a possessive attitude toward ideas. Instead, the students actively leveraged each other's insights to achieve the common goal of creating a protective wrapping.

As John and I moved around the room, we observed the collaborative discussions and problem-solving processes unfolding at each workstation. The shift to dyadic work fostered a sense of shared responsibility, with students utilizing teamwork to optimize their egg protection designs.

Following the construction phase, we proceeded to drop the wrapped eggs examining the results. John initiated a post-experiment discussion about the students' design choices and their teamwork dynamics. This debriefing provided valuable insights I could later incorporate into my therapeutic discussions with the students, emphasizing the importance of effective communication, collaboration, and shared decision-making.

In addition to the egg-drop experiment, John introduced a project centered on airplane design, focusing on loft, lift, and flight duration. Students individually selected two airplane designs from a pool of ten and crafted their respective models. Subsequently, they collaborated by timing each other's flights, measuring loft and lift, and recording the data. The classroom buzzed with activity and enthusiasm as students engaged in this hands-on exploration.

Toward the project's conclusion, all students came together to collectively analyze and compare the performance of different airplane designs. Through graphing and discussion, they assessed the effectiveness of each design, highlighting the collaborative aspects of the experiment and reinforcing the importance of teamwork in achieving common goals. This multi-faceted approach not only enriched the learning experience but also provided valuable lessons in collaboration and problem-solving for the students.

Mix Things Up

Exploring diverse teaching methodologies, such as incorporating collaborative projects and hands-on activities, can significantly impact the dynamics within a classroom. Even implementing these approaches once a month can yield noticeable improvements in student engagement and interaction.

It's essential to strike a balance and avoid overwhelming students to the point where their comprehension suffers. A strategic approach to hands-on activities becomes crucial to prevent cognitive overload, particularly in short time frames of 15 to 18 minutes. By aligning these activities with a clear rationale and educational objectives, educators can optimize the impact of limited time on content delivery.

This intentional mix of teaching methods enhances the learning experience and ensures that students remain actively engaged. Striving for this balance fosters a positive and dynamic classroom environment, promoting effective learning outcomes without overwhelming students.

Universal Model for Design

- It stemmed from the architectural idea of access for all abilities.

- In my treatment, I really like to look at the student from a UDL perspective.

- Environment

- Multiple ways of presenting content

- Student style

Concluding Part 1 of the Universal Model for Design focuses on three essential perspectives within Universal Design for Learning (UDL). These perspectives offer a comprehensive approach to understanding and implementing UDL principles, shaping a more inclusive educational experience.

Firstly, the learning environment takes center stage in UDL. Creating a setting that resonates with teenagers involves a thoughtful consideration of factors such as seating arrangements, lighting, temperature, access to natural light, and the overall layout of the classroom. Details like the configuration of desks, the positioning of the teacher, and the proximity of students to each other contribute to fostering a conducive learning environment.

The second perspective delves into the presentation of content. UDL emphasizes presenting information in multiple ways to accommodate diverse learning preferences. John's approach to the egg-drop experiment serves as an example, offering various materials and incorporating dyadic work. This approach caters to different learning styles and encourages collaboration and diverse problem-solving approaches.

The third perspective centers around understanding and adapting to individual student styles. John's pairing of students based on their compatibility reflects the importance of recognizing how students work best together. This insight enhances the learning experience's collaborative and inclusive nature, ensuring that each student's unique needs are considered.

In a broader context, therapists can apply these perspectives when assessing a high school classroom. Observing the arrangement of desks, lighting conditions, temperature, proximity, and overall use of space provides valuable insights into how the environment supports or hinders learning. These considerations allow educators and therapists to analyze and address potential barriers to student success.

As we delve deeper into the exploration, these perspectives will serve as a foundational framework for understanding how UDL can be effectively applied in educational settings.

- This theory believes all students can learn and embraces neurodiversity.

- The National Center on Universal Design for Learning has designated 3 networks.

The theory believes that all students can learn, and it embraces neurodiversity. This caught my eye the first time I got involved with UDL because it has three designated networks focusing on the brain.

- Three Designated Areas

- Universal Design 1: Environment

- Universal Design 2: Variety in teaching curriculum

- Universal Design 3: Student style

We can think about the environment, variety in teaching curriculum, and student style to approach teenagers and create a plan that's going to engage and be successful for them.

- UDLM suggests that neuroscientists believe that how we learn is as distinct as our fingerprints. They suggest that in order to provide a customized approach, you need to look at three primary brain networks.

- The first brain network is The Recognition Network, housed in the areas of the brain where we listen, see, and read. This is when a student can tell you about an author’s style, like Eric Carle, and can identify various letters and words. They practice recognition, or “the what of learning.”

- The occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes

Neuroscience posits that the learning process is as unique as an individual's fingerprint, advocating for a customized approach not only for special needs kids but all students. In this vein, the focus shifts to understanding three primary brain networks influencing learning.

The first of these networks is termed the Recognition Network, residing in areas associated with listening, visualization, and reading. When students can discuss the stylistic elements of Eric Carle's work (as an example), identify various letters and words, and articulate insights about reading, they engage with the "what" of learning. The involvement of the occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes underscores the intricate neural processes associated with recognizing and comprehending information. This network provides insights into how the brain operates concerning acquiring and interpreting information from various sources, such as auditory and visual stimuli.

- The second network is called Strategic Network, primarily in the prefrontal cortex.

- Here, the student performs tasks; they organize, plan, and express what they know via action, verbal or representational expression. This is referred to as the “how of learning.”

Moving on to the second network, we encounter the Strategic Network in the prefrontal cortex—an area we've touched upon earlier. This network delves into the "how" of learning, encompassing how students approach a task, organize and plan their actions, and articulate or represent what they have learned. Essentially, it encapsulates the entire spectrum of executive function, reflecting the cognitive processes that guide goal-directed behaviors.

The prefrontal cortex's involvement in this network emphasizes its role in higher-order thinking and decision-making. It's important to note that the development of the Strategic Network is intricately tied to factors such as age, grade level, and cognitive abilities, aligning with the evolving expectations placed on students at different stages of their educational journey. Understanding the intricacies of this network provides valuable insights into a student's ability to execute tasks, plan effectively, and demonstrate their grasp of learned material.

- Finally, the 3rd network is the Affective Network.

- This is looking at how to engage learners and what opens their minds up to want to learn. Are they excited, interested, stimulated, challenged, inspired or motivated? They call this the “why of learning.”

The third and final network, the Affective Network, aligns closely with our discussions today. This network explores how learners are engaged, and what triggers excitement, interest, stimulation, or challenge—often associated with the limbic system. The key question here is the "why" of learning. Are students motivated, curious, and invested in the subject matter? This emotional and motivational aspect plays a crucial role in opening up learners' minds to the educational experience.

It's evident from your presence here that you have chosen to engage with this topic willingly, driven by your interest. This aligns with the concept of the Affective Network, emphasizing the importance of creating a learning environment that sparks enthusiasm and curiosity.

For those seeking a deeper understanding of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), there are numerous resources available on platforms like YouTube, offering comprehensive overviews of this intricate approach to education. Utilizing UDL language and theories when communicating with educators fosters mutual understanding and respect. The collaborative sharing of theories between therapists and educators enriches the educational landscape, creating a more cohesive and supportive framework. Embracing similar language, such as the concept of opening the limbic system to facilitate learning, facilitates effective communication and collaboration to enhance the educational experience for all students.

- Environment

- Comfortable

- Welcoming

- Accessible

- Functional

- Attractive

- Adaptable

Engaging in a shared learning experience, let's explore the first aspect: the learning environment. Consider the adjectives that come to mind when describing your favorite place in your house. It's likely to be comfortable, welcoming, easily accessible, functional, visually attractive, and adaptable. Take a moment to jot down a couple of thoughts about your most cherished space at home.

This exercise prompts us to reflect on the qualities that make a space desirable—whether where we retreat after work or where we choose to work from home. For instance, my current location on the porch provides a beautiful outdoor view, comfortable seating, perfect lighting, and the ability to shut the doors to minimize distractions. Thinking about where we work or relax at home, we realize that adjectives like comfortable, welcoming, and functional play a crucial role in defining the environment.

Understanding these adjectives helps shape an environment conducive to learning, whether a classroom or a workspace. Creating spaces embodying these qualities ensures learners feel at ease, motivated, and ready to engage in learning.

- Let’s consider what must be taught…Do we really know the curriculum standards? How much do we need to understand to make our therapy relevant?

- As we venture into presenting content in different ways (The "what" of learning)

How much do we know when we start to think about curriculum standards and what's being taught in that environment? How much do we need to know to make our therapy relevant? I want to swing back a little more to the environment before we delve into this. When you think about UDL and walking into a classroom, imagine in your brain the difference between an elementary classroom, a middle school classroom, and a high school classroom. In my experience, they get starker with less stimulation in the higher grades.

UDL talks about things as detailed as postural issues. Some kids do better with reading, lying on a chair, on their belly, or leaning against a wall. At the same time, others want to sit at a regular desk, on a ball, or a hockey chair. Some kids need that ability to stand and work at a computer. So, when we think about the therapist's influence on environmental changes for our teenagers, we need to interview the teenager about that and negotiate with the teacher.

Some of these UDL classrooms are incredible. They are designed to make the teenager feel safe to sit and learn. An example is addressing the sensory part of an environment for a student. This sixth-grade girl was having a hard time. She was being pulled out into the hallway to do vocabulary work. There were three doors: one coming into the hallway, the other door leading from a classroom, and another door leading from the classroom. Her table was in the middle of the hall, and she was having difficulty concentrating and appeared uncomfortable, often looking behind her. I suggested they pull the table from the wall so she could sit with her back against it and see all three doors. They rolled their eyes at me like I was crazy, but it had worked like a charm by the next week. She hadn't shown any focus issues before in any classroom, which made a difference. These are the things that make us specialists, with different perspectives that another team member might not look at.