Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Integrating Incontinence Into Occupational Therapy Treatment Plans, presented by Krista Covell-Pierson, OTR/L, BCB-PMD.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify three different types of incontinence OTPs can address in treatment.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize high-risk conditions in patients requiring advanced interventions.

- After this course, participants will be able to list 5 potential treatment interventions for incontinence.

Introduction/What is Incontinence?

I am excited to be here to discuss incontinence and share how I integrate this topic into my occupational therapy treatment plans. I look forward to sharing valuable information you can immediately apply to your practice. I always strive to offer practical insights that you can use right away. Today, my discussion will focus on three main areas, and I am eager to jump into the core content.

What is incontinence? Although many of us believe we understand it, it is essential to define the term for our patients clearly. I have encountered numerous clients—especially older adults in their 90s—who insist that leakage is a normal part of aging. However, whether the leakage is minimal or substantial, incontinence is defined as any unintended loss of stool or urine.

In my practice, I use the terminology and examples I share here to educate patients and remind them that incontinence is not an inevitable aspect of aging. While certain conditions associated with getting older may increase the likelihood of incontinence, simply growing older does not automatically mean one will experience it. This is encouraging news for everyone.

When I conduct my courses, I start with a broad overview—discussing basic definitions and the importance of addressing these issues—before delving into more detailed treatment strategies and documentation practices. This approach helps set the stage for a deeper understanding and provides the practical takeaways many of you hope to implement daily.

Why Should OTPs Address Incontinence?

I want to set the stage by asking, Why should occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) address incontinence? When I was in school many years ago, incontinence and its treatment were barely mentioned, which I believe is a disservice to emerging professionals. We, as OTPs, deserve a seat at the table, and I am passionate about ensuring that our colleagues understand our unique role in managing this issue.

Our work naturally involves addressing the context in which our clients live. I spend countless hours with clients in environments like bathrooms, focusing on cognition, safety during transfers, and musculoskeletal challenges. I am adept at helping people change their routines and integrate functional strategies into their daily lives. If we fail to consider the various facets of incontinence, we miss opportunities to enhance overall well-being.

The impact of incontinence extends far beyond toileting itself. For example, if someone makes frequent trips to the bathroom—perhaps ten, eleven, or even twelve times a day—their activity tolerance for other tasks inevitably decreases. Sleep hygiene, a critical activity of daily living, can suffer, and even fine motor skills, such as handling buttons and zippers, may be compromised. These issues often overlap with challenges I already address, including managing durable medical equipment and alleviating pain.

Incontinence is deeply embedded in our clients' daily routines and overall functionality. Pelvic floor dysfunction, for instance, affects activity tolerance and safety and limits a person’s ability to engage in instrumental activities of daily living. I have seen countless patients refrain from activities they once enjoyed—whether it’s attending church, hosting friends, going to the gym, or even making a simple trip to the pharmacy—simply because they were concerned about incontinence. Although I am relying on an older statistic, it is notable that 45% of home health clients report difficulty with bladder and bowel control. This figure is significant and will likely rise as our population ages, particularly with baby boomers now entering advanced years and living longer than any previous generation.

The impact of incontinence is not isolated to a single aspect of care; it affects goal achievement across multiple disciplines. When a client avoids walking out of fear of leakage, the ramifications extend to physical therapy and the work of speech-language pathologists, fitness coaches, and others. The nature of incontinence is such that if it is not addressed, it worsens over time. This creates an obligation to intervene early and continuously throughout the treatment process.

Moreover, incontinence is often intertwined with other chronic issues, such as Parkinson’s disease, muscle weakness, lack of coordination, and back pain. These correlations further underscore the importance of our proactive engagement in addressing incontinence. By integrating strategies to manage this condition, I help my clients maintain a higher quality of life and achieve their therapeutic goals.

What Does AOTA Say?

Let’s maintain our macro perspective and focus on what our national organization has to say. The American Occupational Therapy Association emphasizes that OTPs can be vital to the healthcare team promoting pelvic health. I won’t read the entire statement, but I will highlight a few key points so you know that your national organization supports you.

When I was a new occupational therapist, pelvic health wasn’t even a focus within AOTA. It’s been a remarkable progression since then. The Association notes that, in addition to difficulties with daily living activities, many clients experience sleep loss, affecting their overall function and participation in work, play, and leisure throughout the day. That is precisely what we aim to improve.

As OTPs, we use a holistic, client-centered approach when treating our clients, focusing on their roles, habits, and occupations. What stands out to me in this discussion is the shift in language over time. There was a period when intervention for pelvic floor dysfunction was primarily focused on surgical and pharmacological approaches. Today, however, the treatment emphasis has shifted towards behavior. This shift signals an opportunity for us to employ strategies such as habit formation, bowel and bladder retraining, diet, and fluid regulation—not restrictions, but thoughtful regulations—along with pelvic floor muscle training.

Research supports this approach by demonstrating that combining biofeedback with traditional pelvic floor rehabilitation is the most effective strategy for treating pelvic floor deficits. In addition, studies have shown that mindfulness techniques can significantly decrease pain and reduce anxiety associated with these deficits. These are interventions that are already well within our skill set.

I am so passionate about this field because I have had mentors—pioneers in pelvic muscle dysfunction—whose innovative work paved the way for what I can do today. I hope this course and webinar will inspire many of you to embrace the world of pelvic health and make a meaningful difference for your patients. We are in a unique position to receive guidance from experienced mentors and pass that knowledge on to future generations of OTPs.

Ultimately, we are equipped to assist clients in physically and psychologically improving through evidence-based, client-centered, and holistic treatment. It’s encouraging to see our national organization reinforce the value of this approach, and I am excited to continue championing these strategies in my practice.

Impact of Incontinence

Incontinence has a significant impact on my patients, often leading to depression. I’ve seen it firsthand—when I attend webinars or courses, I recall the faces of patients I could have helped, each with their own story. I remember Rosemary, who was depressed because of her incontinence, and Kim, who withdrew from social activities due to anxiety over potential accidents. These experiences highlight how fear of embarrassment can reshape a person’s life. Incontinence can also lead to fatigue and an increased risk of falls, especially in hospital settings or organizations focused on reducing fall risk. This can help garner administrative support for addressing the issue.

Another important consideration is the financial burden of incontinence supplies. I once received a referral from a patient whose primary reason for seeking treatment was not only to improve her quality of life but also to reduce the expense of supplies, which can average between $50 and $200 a month. For many, this represents a significant financial strain, money they would prefer to spend elsewhere.

In addition to these challenges, patients with incontinence are at a higher risk for infections and skin irritation. These complications are among the top reasons individuals move from living at home to higher levels of care, such as assisted living or skilled nursing facilities. Caregiver burnout is another concern, and I recognize that caregiver training is crucial, especially when working with patients who have cognitive difficulties. By training caregivers, we can help manage incontinence more effectively and improve the overall well-being of patients and those who support them.

Evaluation

Let’s shift our focus to where to begin. I’ve noticed that many occupational therapy practitioners feel nervous about integrating pelvic health into their evaluations, often thinking, "I don't know how to do this." I want to share some language and strategies to help build your confidence and remind you that you already have a strong foundation. Before any self-doubt creeps in, recall that you know how to conduct a thorough medical record review and interview your patients. Now, all you need to do is incorporate additional information about pelvic health into that process.

I suggest making small changes in your routine evaluations. For example, during your medical record review, look for clues that might reveal potential causes, frequency, or difficulties related to pelvic health. Then, weave those insights into your patient interviews. Normalizing and initiating the conversation about pelvic health can be challenging, but it’s essential.

One gentle way to begin is by asking, “Do you ever have difficulty getting to the bathroom on time?” If your patient answers no, that’s great. If they say yes—or even sometimes—that response can open the door to further discussion. Sometimes, patients will initially share only a little until trust is built, while others might share more details than you anticipated. The goal is to normalize the conversation and become comfortable with the language surrounding pelvic health, even if it feels unfamiliar at first.

Assessing pelvic health also means looking at the underlying components and contributing factors. We often have an advantage over those working in home care or mobile outpatient settings. When visiting a patient’s home, environmental cues can raise red flags—such as a grocery bag on the kitchen table filled with incontinence products or certain odors. These observations can be useful in gathering information.

It’s important to consider various risk factors. Medications and stress levels can influence incontinence, as can neurological conditions and diabetes, which are known to raise their incidence. Discussing their childbirth history with female patients can also be informative. Asking, “Have you had any children? Were there any complications during delivery?” can provide insights. It’s also worth noting that even if a patient has had a C-section, that doesn’t automatically rule out potential pelvic floor issues. Similarly, a history of pelvic surgeries, even if they occurred long ago, should be considered. Additionally, smoking has been linked to an increased likelihood of incontinence.

Finally, collaborating with your interdisciplinary team is key. Bringing up incontinence in team meetings and asking nurses or other team members for their insights can help build a comprehensive understanding of your patient’s needs.

Teach Clients About Anatomy and Urinary/Bowel Function

The next step I like to take is to educate my clients about their anatomy and the basics of urinary function. I can almost guarantee that many patients have never been educated in this area. I don’t dive too deeply into the complexities; I aim to keep the information straightforward and accessible.

One effective strategy I use is to provide a simple, visual aid during our discussions, as in the Figure 1 example. I call it my "golden nugget" approach. I bring a clipboard with a basic printed picture of male and female anatomy. This tool helps set the stage for our conversation and makes it easier for patients to understand what might be happening in their bodies. Using a clear and uncomplicated diagram, I can explain urinary malfunction in terms that resonate with them and empower them with knowledge about their health.

Figure 1. Male and female anatomy (Click here to enlarge the image.). (Images: Continued (licensed from Getty Images)

I am using labeled pictures for your reference, but I like to use unlabeled ones as a teaching tool because I’ve found that labels can sometimes be overwhelming for patients. I start by orienting them to the basics: I point out the tailbone at the back and the pubic bone at the front. I often use myself as an example by pointing to my pubic bone and tailbone, explaining that a group of muscles, known as the pelvic floor muscles, lie in that area, much like napkins at the bottom of a bread basket.

My goal is to increase the mind-body connection for my patients when it comes to their pelvic health—something many of us have little awareness of. For example, just as I can ask someone to bend their elbow and see a bicep contraction, I ask them to squeeze their pelvic floor muscles. I even squeeze mine during our conversation to illustrate the point, though the contraction isn’t visible. This comparison helps normalize the discussion about what’s happening internally, making it less intimidating.

I also use the diagrams to discuss the passageways through the pelvic floor. For men, I point out the urethra and highlight the prostate gland—a small but sometimes troublesome organ that can cause significant issues. For women, I explain the musculature that extends from the pubic bone and how everything must pass through these muscles to void. I also mention that if a woman has had a hysterectomy, the removal of that central organ can affect the positioning of surrounding tissues and potentially lead to complications. Although our anatomy might appear neatly organized in diagrams, everything is a bit more compact and interrelated.

Starting the conversation with these basic anatomical points provides a gentle introduction for patients who are experiencing pelvic health struggles. It opens the door for more in-depth discussions and assessments, making it easier for them to understand what might be happening inside their bodies.

Home Reference for Therapists

In addition to the in-person explanations, I also provide home reference links in the handout for further learning. These links lead to YouTube videos on urination, defecation, and related topics. They offer an easy way for clinicians and patients to dive deeper into the subject, though I deliberately kept today's session focused on treatment strategies.

These videos can be valuable resources for those in skilled nursing or rehabilitation settings. I often recommend that patients watch a few of these videos between visits to reinforce what we've discussed and help them understand the rationale behind their treatment. This approach supports their learning and encourages greater engagement and buy-in, ultimately contributing to better outcomes.

Helpful Terms

I want to introduce a few key terms you might encounter in this field, and I'll go through them quickly. Biofeedback is one of the areas in which I'm certified, and it is a powerful mind-body technique to help our patients better understand their body's functions. I use biofeedback to monitor heart rate, breathing patterns, and muscle responses, and there are even specific machines designed for pelvic health. If you’re interested in diving deeper into this subject, pursuing certification in biofeedback is an excellent step. It makes a difference for patients who struggle with contracting or relaxing their pelvic floor muscles.

I often compare it to a situation where a patient who has had a stroke might not realize they are leaning to one side until we use a mirror to show them. In the same way, when I ask a patient to contract their pelvic floor, and they’re having difficulty, I hook them up to a computer that provides immediate feedback, showing them exactly what’s happening in their body. That visual confirmation can be very encouraging and instructive.

Another term you might hear is cystocele, which refers to a condition where the bladder bulges into the vaginal wall. This can lead to frequent urination and even pain during sexual activity. Then there’s cystoscopy, a term I never tire of saying, which involves inserting an instrument into the urethra to examine the urinary bladder. Dyspareunia, or pain during sexual intercourse, is another important term.

Electrical stimulation, often abbreviated as E-stim, involves passing a small electrical current through the muscles around the bladder. This technique can help these muscles contract and strengthen, and many of you may have already used E-stim for other conditions. Interestingly, it’s also effective for retraining the pelvic floor and can help calm the bladder, a topic I plan to discuss further.

Biofeedback and E-stim are often taught together for a reason—they complement each other well in treatment protocols. These are just a few terms you might encounter or want to investigate further. Some will directly impact your treatment approach, while others might appear in medical records. I recommend marking this slide or taking notes so that you can refer back to these definitions and feel confident when reviewing medical records or discussing these concepts with colleagues.

Educate on the Role of the Pelvic Floor Muscles

I want to focus on the pelvic floor muscles, which are crucial in supporting the pelvic organs. While the detailed anatomy—including the names of all the muscles and their insertions—is more relevant for in-depth study, I aim to help patients understand that their pelvic floor muscles have important functions. When these muscles are weak or not functioning properly, patients might experience pelvic organ prolapse, where organs can bulge through the pelvic floor. Although this condition is often not painful, it can be alarming to witness and indicates that the pelvic floor muscles are not performing their supportive role as they should.

The pelvic floor muscles provide essential sphincter control for both the bladder and bowel, and they facilitate the opening and voiding of the urethral and anal canals. If these muscles are weak or poorly coordinated, or there is a lack of awareness about their function, bowel and bladder control issues can arise. Moreover, these muscles must withstand pressure from everyday actions—such as sneezing, coughing, or climbing stairs—without allowing unwanted leakage. A well-functioning pelvic floor remains tight during these activities and also plays a role in enhancing sexual response.

This is why I believe it's important to ask patients about sexual activity as well. Although many practitioners might hesitate to broach the topic, it’s essential to overall well-being and quality of life. Recognizing the multifaceted role of the pelvic floor reinforces why occupational therapy should be an integral part of the discussion around incontinence and pelvic health.

In summary, understanding incontinence and how the pelvic floor functions helps set the stage for effectively addressing these issues in our practice. Our role is to help patients strengthen these muscles, improve coordination, and ultimately enhance their quality of life by addressing problems with bowel and bladder control and related areas like sexual health.

Healthy Bladder Habits

Now, I’d like to delve into healthy bladder and bowel functioning. I bring my teaching clipboard, including unlabeled anatomy pictures and informational sheets, when teaching my patients. These resources are invaluable whether I’m in a hospital, skilled nursing facility, or any other setting. I often start by sharing a sheet on healthy bladder habits, reviewing it with the patient, and asking, “Does this sound like you?”

For instance, I ask if they feel like they’re getting about two cups of urine when they void. Some patients might be unsure, but those who consistently produce a small volume often recognize that it’s insufficient. This simple check can serve as a yellow flag, indicating that further investigation might be needed.

In addition to volume, I discuss frequency. Typically, urination should occur six to eight times in 24 hours, although many of us don’t keep track of our bathroom visits. I also point out that urine should flow easily, without the need for straining, and the stream should be steady—a factor that can be affected by issues such as an enlarged prostate in men.

I explain the concept of an urge, which is the sensation that builds as the bladder fills, and I ask patients if they consistently feel that urge when they need to go. Interestingly, some patients report that they rarely experience this sensation, which can be surprising. Additionally, I inquired whether they must rush back to the bathroom within 30 minutes after voiding, which might suggest that the bladder isn’t completely emptying. This phenomenon is something I’ve seen frequently in children, who often void just enough to stop feeling discomfort and then quickly return to their activities. I’ve also observed it in some women, particularly those more anxious.

For my colleagues working in home health, nursing, or education, it’s important to note that holding urine for more than four hours is not recommended. Prolonged retention can overstretch the bladder, causing it to become “lazy” and less responsive when it’s time to contract and empty. In some professions—like teaching first grade—patients might have a history of being forced to hold their urine for extended periods, which is a critical point to consider during evaluation.

By discussing these details—urine volume, frequency, ease of flow, the sensation of urge, and the importance of timely voiding—I help my patients understand what healthy bladder function looks like. This approach facilitates a more open dialogue about their symptoms and lays the groundwork for effective treatment and management of any issues they might be experiencing.

Healthy Bowel Habits

When discussing the bowel and bladder in tandem, it’s important to emphasize that you cannot treat one without addressing the other. Often, patients may be primarily concerned with urinary leakage, and even many therapists tend to focus on urinary incontinence. However, I always stress the importance of evaluating both aspects in my practice. Even if a patient complains mainly of urinary issues, I also make it a point to ask about their bowel habits.

When a patient says they are “pretty regular,” it’s important to clarify what that means. Regular bowel habits can range from having a bowel movement as infrequently as three times a week to as often as three times a day. There should be no excessive straining, as heavy straining can wreak havoc on the pelvic floor—leading to complications such as hemorrhoids or tissue damage. I ask my patients whether they know when they need to go and if they are aware of when they’ve fully completed a bowel movement. I also inquire about the consistency and appearance of their stool.

Admittedly, you might not have anticipated discussing stool characteristics with your patients, but it’s essential to understanding their overall pelvic health. By incorporating these questions into my assessments, I ensure I have a complete picture of their bowel and bladder function, which is critical for developing an effective treatment plan.

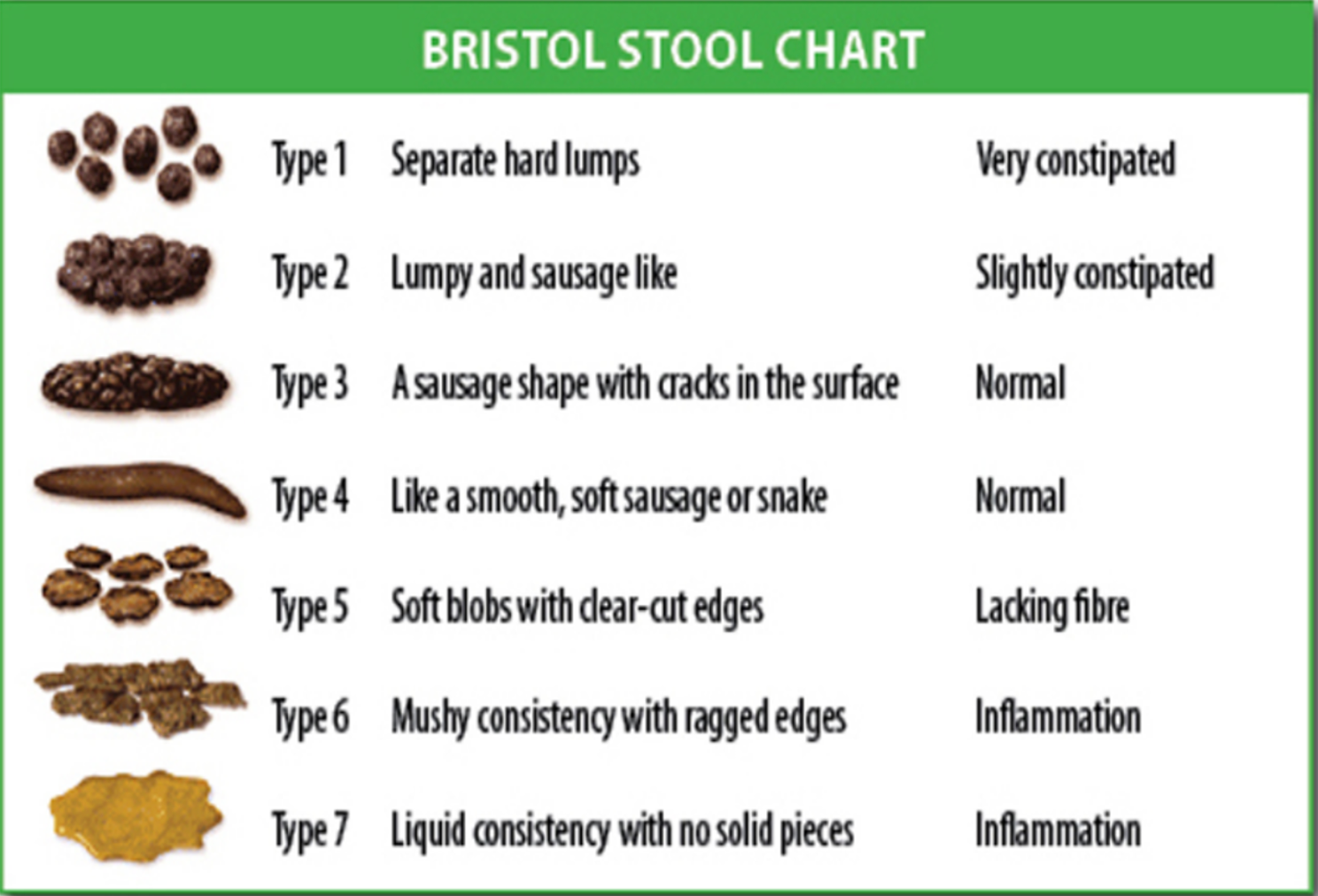

Bristol Stool Chart

We will look at the Bristol Stool Chart in Figure 2 and want people to be around level four.

Figure 2. Bristol Stool Chart. (Image: Cabot Health, Bristol Stool Chart, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons).

Sometimes, in that initial conversation, I ask what might seem peculiar. I explain, “When you have a bowel movement, would you say it’s the size, shape, and consistency of a very ripe banana?” Patients often pause, then respond with descriptions like “It looks like little balls” or “It’s all loose.” Just yesterday, one patient described it as looking like “long ribbons.” These details are invaluable because they help determine whether a patient’s bowel habits are healthy.

I also introduce the Bristol stool scale—a visual tool I keep laminated on my teaching clipboard and share with patients. Observing their reactions is fascinating; people are genuinely interested in learning about their bodies, much like taking a fun quiz from a magazine. They start comparing notes—sometimes even partners will chime in, with one remarking that her stool looks one way and his another. Even children are curious when they notice the laminated chart in my treatment bag, which often turns into a lighthearted conversation.

These discussions are a starting point for educating patients about healthy habits. Depending on the patient’s capacity and interest, I may go into great detail or provide the handout and ask probing questions to get a clearer picture of their habits. I approach these questions like a detective, gathering clues to understand their pelvic health better.

Types of Incontinence

We will now talk about stress, urge, mixed overflow, bowel, and functional incontinence.

Stress Incontinence

Let’s begin with stress incontinence. When abdominal pressure increases—for example, during a sneeze, while jumping on a trampoline, or even simply standing up—the pressure can sometimes exceed what the pelvic floor muscles can handle, leading to urinary or stool leakage. The amount lost can vary from a small dribble to a more noticeable release, but the underlying issue is the same: the abdominal pressure surpasses the pelvic floor’s capacity.

While most of my patients might not be jumping on trampolines, they may experience increased abdominal pressure in everyday activities such as coughing, laughing, or just getting out of bed in the morning. Stress incontinence is the most common type I encounter, typically resulting from weak pelvic floor muscles, and the good news is that it’s often the easiest to treat. In our upcoming discussion, I’ll share various treatment strategies for managing these issues.

Urge Incontinence

Urge incontinence is characterized by a sudden, overwhelming urge to urinate that can lead to leakage. It’s important to note that sometimes patients experience the urge without any loss of urine. I provide information and strategies to help patients control that urge in my practice. However, it’s also worth noting that for third-party payment purposes, the diagnosis of urge incontinence is typically only recognized when there is actual leakage.

The leakage associated with urge incontinence can vary from a small amount to a larger volume, and I often refer to this phenomenon as the "key in the door syndrome." This isn’t just a mild inconvenience where a patient feels an urge and can easily make it to the bathroom; it’s an intense, almost alarming sensation where the patient feels as if they must immediately reach the toilet or risk losing control.

I’ve seen instances where a patient, living in assisted living and otherwise functioning well—engaging in conversation with the activity director and walking confidently with their walker—suddenly experiences that urgent need right as they reach the door. At that moment, they become a high fall risk, a red flag for further intervention. Other triggers, like the sound of running water or even the act of pulling a car into the garage after shopping, can provoke a “bladder temper tantrum.” In these situations, the bladder behaves much like an overactive muscle, spasming in a way that sends an urgent message to the patient that they need to get to the bathroom immediately.

Understanding these triggers and the nature of urge incontinence is key to helping patients manage their symptoms effectively and safely.

Mixed Incontinence

Mixed incontinence is a pretty self-explanatory combination of urge and stress.

Overflow Incontinence

Now, let’s discuss overflow incontinence—a fascinating phenomenon that involves involuntary urine loss because the bladder becomes simply too full. Essentially, when the bladder reaches its capacity and overflows into the urethra, it can result in continuous leakage. I often see this in patients with an enlarged prostate. As you might recall from anatomical images, the urethra passes through the prostate gland. When that gland enlarges, it squeezes the urethra, making it difficult for urine to exit completely. As a result, the bladder overfills and forces urine out, leading to a dribbling or constant leakage that can be very upsetting.

What’s particularly interesting is that patients with overflow incontinence may not feel a strong urge to urinate, even though they are leaking. A weak urine stream is a classic sign of this condition. I sometimes joke that if I were a pelvic floor therapist working in a public restroom—much like a physical therapist observing gait at an airport—I could gauge who might be experiencing these issues simply by listening to the sound of their urine stream. Although I don’t diagnose patients from a toilet stall, these observations underscore the importance of listening to what the body tells us.

Overflow incontinence is also commonly associated with recurrent urinary tract infections. When the bladder cannot empty completely, urine remains stagnant, allowing bacteria to proliferate and cause infections. Beyond prostate issues, overflow incontinence can occur in individuals with an overstretched bladder—perhaps due to years of underuse—or in those with neurological conditions. For example, patients with nerve damage, such as those recovering from a spinal cord injury, might struggle with bladder contraction, leading to an overflow situation.

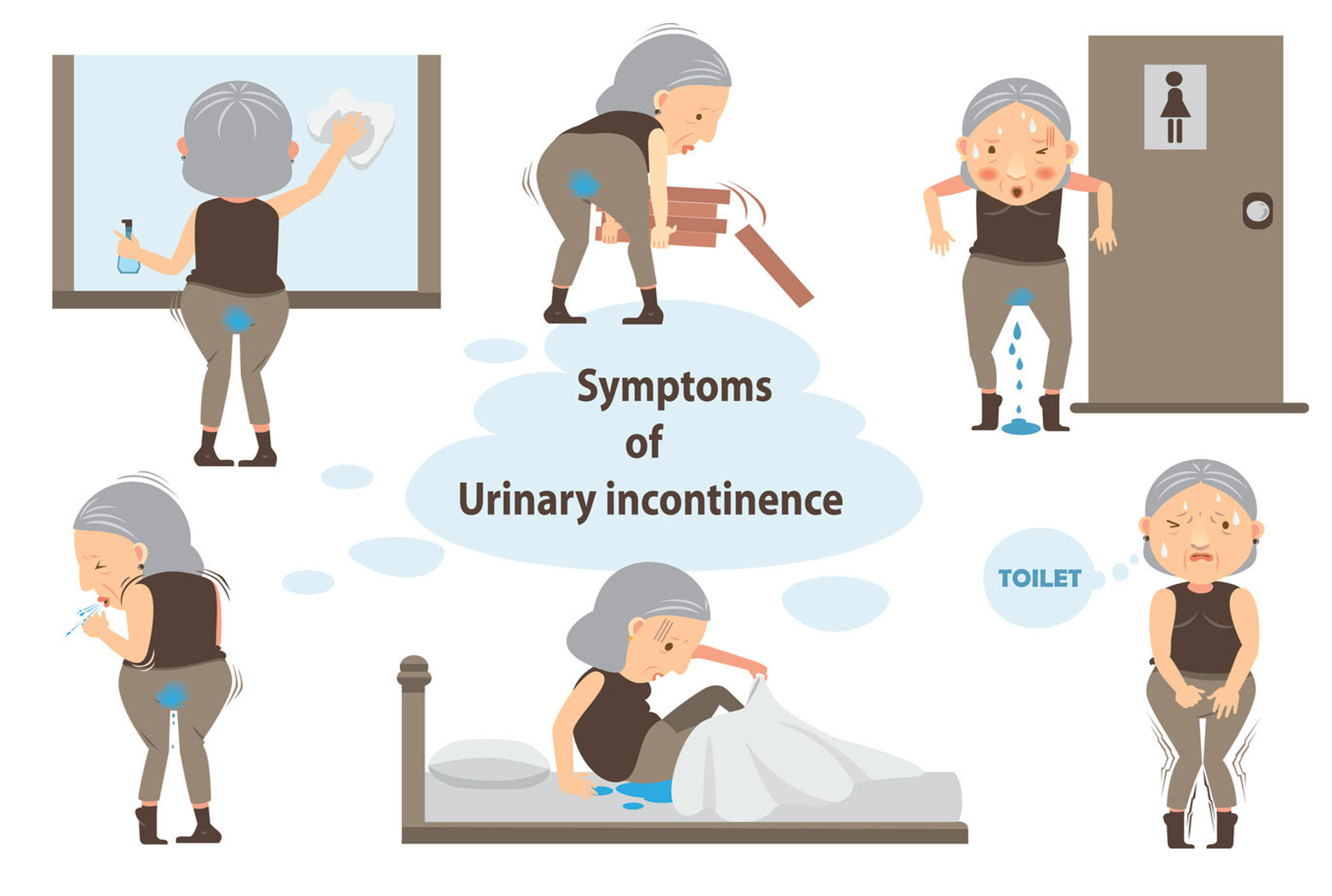

Symptoms of Incontinence

When evaluating incontinence symptoms, I identify the key factors contributing to a patient’s condition and translate those into a functional context. Visual aids—like this picture in Figure 3 or something similar—can be incredibly effective for sparking conversation and helping patients understand how these symptoms impact their daily lives. This approach clarifies what incontinence looks like from a clinical perspective and makes the discussion more accessible and relevant to each individual's experience.

Figure 3. Symptoms of urinary incontinence (Image: Continued (licensed from Getty Images).

When discussing incontinence symptoms, I like to relate them to everyday activities to create a more functional conversation with patients. For example, I might ask, “When you're cleaning or picking something up, do you experience any leakage?” These types of symptoms are often indicative of stress incontinence. Picture a woman who experiences leakage when sneezing or coughing—this is a classic example of stress incontinence. In contrast, looking at the images of the two ladies on the right, one can see signs of urge incontinence. They appear visibly stressed and constantly need to rush to the bathroom, demonstrating that their entire body responds to an overwhelming urge they simply cannot control.

Then there’s the bottom middle image, which illustrates nocturia. Nocturia, by itself, is not considered incontinence—it refers to the need to get up at night to go to the bathroom. However, if a patient is leaking or experiencing significant urine loss during the night, that is a concern that we must address. Using visuals like these helps frame the conversation, making it easier for patients to understand the different types of incontinence and how these symptoms might be affecting their daily lives.

Functional Incontinence

As an occupational therapy practitioner, I often encounter functional incontinence—a loss of urine or stool that stems from a patient’s physical or mental limitations. Many of us are already addressing this in our daily practice. For example, a patient with Parkinson’s disease might have a slow gait and struggle with fine motor control. By the time they get to the toilet, leakage has already occurred. We need to address this critical issue as part of our holistic care.

Thank you for dedicating your time to and engaging with these topics today. Understanding and addressing these functional challenges can significantly improve our patients' quality of life.

Equipment

We're going to mix it up a little bit. Here are some pictures of toilets and some things to consider in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Some equipment options. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

On the left is a picture of one of my sons—his face is intentionally not shown because it was taken while he was using a squatty potty. For those who might not be familiar, a squatty potty is designed to promote a squatting position during voiding. This position can be especially helpful for individuals with overflow incontinence or those with difficulty with the standard seated toilet position. The squat allows the body to work with gravity, easing the process of emptying the bladder and reducing the strain on pelvic muscles.

I also keep a variety of resources with me, including photos and diagrams that demonstrate different toilet setups. For example, I often point out the difference between our high-rise toilets and what’s known as a squat commode—a type of toilet commonly found in some countries, like China, which is designed to be used in a squatting position. Although many of our patients in Western settings may not have the option to void in a full squat due to the design of their bathrooms, using a footstool or a squatty potty can simulate this posture and help them achieve a more natural and effective voiding position.

Another consideration is bidet usage. If a patient has a bidet at home, it’s important to know whether it’s attached to the toilet or if they need to move over to a separate bidet area. This detail can affect not only their ability to manage incontinence but also the ease of maintaining personal hygiene.

Beyond the mechanics of voiding, functional incontinence can be significantly influenced by the environment. I recall a patient who had to navigate a very narrow doorway in his bathroom. The constricted space forced him to turn and shimmy his way through, slowing him down and leading to leakage between movements. Similarly, I have worked with an active patient who, after orthopedic surgery, became reluctant to go out in public. She was afraid that the high toilets in public spaces would prevent her from getting up safely, which limited her community participation. I also had a gentleman, eager to go camping with his family, who was nervous about using a camping toilet. Although he used a walker, his fear of not being able to access a proper toilet on time was holding him back from enjoying a cherished activity.

Environmental factors also play a role for patients with cognitive impairments such as dementia. A checkered pattern on the floor, for example, can be visually confusing and may deter someone from moving confidently toward the bathroom. I’ve encountered patients who refuse to use a particular toilet simply because they felt uncomfortable in that space or who would avoid a room entirely—sometimes even altering the home environment with rugs or other modifications to enhance safety. In one case, a patient, in his haste to reach the bathroom, accidentally broke a section of the wall. Such instances underscore the importance of considering physical and cognitive factors when addressing functional incontinence.

In my practice, I’m constantly reminded that the environment's design, the type of toilet, and even subtle cues like the need for a bidet or a footstool can significantly impact a patient’s ability to manage incontinence. These details affect their physical health and their confidence and willingness to engage in everyday activities. By tailoring our interventions to accommodate these environmental factors, we can help our patients achieve a more functional, comfortable, and safe experience in toileting.

Bowel Dysfunction

Bowel dysfunction is any loss of stool or recurring episodes that may be due to lack of sensation, weakened pelvic and floor muscles, and then also we have to talk about constipation.

What Causes Constipation?

Constipation, for me, is defined as infrequent bowel movements occurring consistently over a week rather than an isolated incident—like what might occur after a knee replacement when anesthesia and pain medications temporarily slow down gut motility. When a patient experiences ongoing constipation, it usually means they're straining to have a bowel movement and not completely emptying their bowels. I’ve seen patients develop a range of creative strategies at home—from using enemas and suppositories to relying heavily on laxatives—which can disrupt the establishment of a healthy, functional bowel routine.

In my evaluations, I prioritize asking detailed questions about bowel habits early in the treatment process, especially if there's been a persistent change. For example, if a patient reports that they haven’t had any bowel movements in a significant period, that’s a red flag, and I advise them to seek medical attention promptly. Impaction is a serious risk, and if I notice signs like blood in the stool or severe pain during evacuation, it’s critical to refer them for immediate medical evaluation.

I must admit that when I first started working in this area, I had a very basic understanding of constipation—essentially, that it just meant having difficulty going to the bathroom. Over time, I’ve come to appreciate the nuances of this condition. For instance, low fluid or fiber intake is a major risk factor, and I can almost guarantee that many of my patients, and even people watching this webinar, aren’t getting enough fiber. Additionally, patients with urinary incontinence often limit their fluid intake out of fear of leakage, inadvertently increasing their risk for constipation. A sedentary lifestyle also plays a big role, and I always encourage my patients to increase their physical activity, as movement can help stimulate bowel function.

I also find it valuable to explore the patient’s history with bowel and bladder control, even from childhood. I’ve encountered several individuals who experienced constipation as young children—sometimes as early as four or five years old—which, in some cases, led to a condition known as megacolon. Even if they managed fine for many years, as these patients reach their 80s, an overstretched colon can contribute to incontinence issues, such as increased urine leakage.

It’s essential to ask about a patient’s occupational history and any long-term habits they may have developed because these insights can guide treatment. For example, slow bowel movements are common in patients with Parkinson’s disease, and sometimes, constipation is one of the early signs, even before a formal diagnosis is made. When the colon absorbs too much water, the stool becomes hard and difficult to pass. Other factors, such as lifestyle changes, pregnancy, frequent travel, and even laxative abuse, can all contribute to constipation.

I also carefully consider the medications my patients are taking. Many pain medicines, antidepressants, calcium supplements, and even a range of other commonly prescribed medications can cause constipation. I recall reading that up to 50% of prescribed medications in the United States may have constipation as a side effect. While I don’t scrutinize a patient’s medication history for every possible cause of constipation, I do pay close attention if they’ve recently started a new medication and then report an increase in constipation.

I always strive to gather as much detailed information as possible from my patients about their bowel habits. Even if a patient relies on many laxatives or other home remedies, it’s important to honor their experience and trust and use that information to tailor an effective treatment plan. Open dialogue about these issues helps create a comprehensive treatment strategy and ensures my patients feel heard and supported in managing their conditions.

OT Settings

In my practice, I’ve learned that while the fundamental aspects of incontinence—such as understanding anatomy, stress and urge incontinence, and bowel issues—remain constant, how we address them can vary significantly depending on our work setting. The person, environment, and occupation model comes into play here. The environment in which a patient lives or receives care can directly influence clinical outcomes.

For example, in a short-term rehabilitation setting, patients may only be in our care for a brief period. In those cases, I might focus on providing concise, practical information and leaving behind resource materials that they can refer to later. This approach may involve educating them on strategies to manage their symptoms at home since I might not have the opportunity to see them repeatedly. In contrast, in settings where I have more consistent and long-term contact with a patient—such as in-home health or outpatient therapy—I can incorporate more in-depth, personalized treatment strategies that gradually build their confidence and competence in managing incontinence.

I’ve also noticed that the resources available in different settings can dictate the extent of intervention. For instance, in some facilities, more equipment might be available to assist with functional toileting, or a team of caregivers may help reinforce what we’ve discussed in therapy sessions. Meanwhile, in settings with limited resources, it becomes even more critical to equip patients and their families with clear, actionable guidance that they can implement on their own.

As OTPs, it’s important to remain adaptable and tailor our interventions to the specific context where we practice. This adaptability ensures that we provide the most effective care possible within our limitations and encourages others to integrate pelvic health into their evaluations and treatment plans. By doing so, we can help improve our patient’s quality of life regardless of the setting in which they receive care.

Hospital

In a hospital setting, I often encounter cases where incontinence or constipation is of new onset—often related to surgery or injury. These issues can increase a patient’s anxiety and hinder their progress in rehabilitation. Sometimes, a little encouragement goes a long way. I remind my patients that after being under anesthesia, undergoing major surgery, or starting new medications, temporary constipation is common and typically improves with time. Of course, it’s our job to work on these issues actively.

I like to show patients a few simple techniques they can use in the bathroom to improve their positioning and harness gravity to their advantage. For instance, I might introduce them to a simulated squat—if they can manage it, we can begin training specifically geared toward addressing incontinence. It’s important to educate patients that there are multiple treatment options available, even for those who believe they’ve struggled with urinary incontinence for years.

I recognize that in some cases, I may only have a brief window with a patient—perhaps just one session before they’re discharged. Even then, I want to ensure that they leave with practical information and a clear understanding that improvement is possible. I always provide a local contact number for further support, emphasizing that we must all work together to bridge gaps within the healthcare system. Whether addressing incontinence, low vision, falls, or other concerns, our role is to facilitate referrals and ensure that our patients are connected to the appropriate resources. The healthcare system can be difficult to navigate, so it’s essential that we help guide our patients through it.

In a hospital environment, toileting is one of the key activities of daily living we address from the very start. This provides a natural opportunity to discuss bowel and bladder health practically, non-threateningly. I often take advantage of moments when patients sit on the toilet to educate them further. I’ll review my treatment clipboard with them, share handouts on healthy habits, and provide guidance on pelvic floor exercises. Even if they don’t follow up immediately, I believe that simply knowing options and strategies are available is a valuable step forward.

Skilled Nursing

I truly enjoy working in skilled nursing, home care, and mobile outpatient settings, as well as in longer-term rehabilitation, because these environments allow me to spend extensive time with clients. Often, I have an hour to 75 minutes with a patient, and during that time, we build a significant amount of trust. This extended interaction enables me to provide highly individualized education about their condition and develop treatment plans that incorporate their specific incontinence challenges.

In skilled nursing, I can integrate incontinence into treatment goals very effectively. I recall one patient who was recovering from back surgery. Alongside her surgical recovery, she had been struggling with urinary incontinence and constipation for a long time. During her rehab time, we focused on strategies to improve her continence and increase her self-awareness regarding pelvic control. The gains she made were substantial, and by the time she left rehab, she was managing her symptoms much more effectively.

Being in these settings also positions us as leaders within the interdisciplinary team when it comes to managing incontinence. In several instances, I've taken the initiative to sit down with the director of nursing to address issues that affect both patient care and staff workload. For example, I once highlighted why a patient was repeatedly asking to use the bathroom every 15 minutes, which was understandably frustrating for the CNAs. By addressing the situation, we not only improved the patient's quality of life but also helped reduce staff burnout and increased CNA buy-in for our treatment protocols.

Collaboration extends to other departments as well. I often work closely with the dietary department to ensure that patients receive the appropriate nutrition—like increasing fiber through more fruits and vegetables—to support healthy bowel function. Hydration is another critical component, and we work together to make sure patients are adequately hydrated. Additionally, I engage with the activities department to explore the possibility of starting a pelvic floor muscle exercise group. I’ve even led such groups and training activities assistants on proper techniques. These program developments have been instrumental in managing bowel and bladder issues, reducing risks for skin breakdown and infection, and ultimately empowering the staff to implement behavioral strategies effectively.

Home Care

Working in home care gives me a unique advantage. I have prime access to assess what's happening with a client's incontinence right in their own home. For example, a patient might tell me, "Oh, I just have a little bit of leakage sometimes," yet when I look, I see they’re using giant briefs. That discrepancy tells me more about the story, and I always make it a point to ask, "Tell me about these—when do you use them?" Often, they’ll explain that they reserve the larger briefs for nighttime because they experience major accidents then. This kind of open conversation is essential for accurate assessment.

I also take the opportunity to evaluate the entire home environment, looking for toileting concerns as part of the overall picture of bowel and bladder health. It’s not just about toilet transfers and pericare; it’s about understanding how incontinence might negatively affect meaningful activities. For instance, if a client on home care aspires to return to community living, I need to know: How will they manage their bowel and bladder concerns outside the home? Can we improve these issues or refer them to an outpatient setting for further support after their home care period ends?

When I first started my company, Covel Care and Rehab, I believed that patients returning home on home care would have all the bells and whistles—the full spectrum of support—to achieve optimal function. However, my experience quickly showed me that the reality is different. In home care, our primary focus is on making patients safe and functional. We do what we can, but often, we can’t help them reach their highest functional potential within the constraints of home care services.

That realization led me to develop a system connecting patients with additional resources to elevate their function. This might involve referring them to a mobile outpatient practice like mine, a brick-and-mortar clinic, or even a personal trainer at a gym—essentially, any resource that can take them to the next level of recovery and independence.

In essence, when working in home care, it’s crucial to address immediate safety and functionality and plan for the patient’s long-term needs. By integrating incontinence management into our overall treatment planning, we can help patients transition more successfully to community living. And that’s what it's all about—incontinence and beyond.

Outpatient

In outpatient settings—whether in a traditional clinic or through a mobile outpatient practice like mine—there’s a tremendous opportunity to address issues such as incontinence, pelvic pain, and prolapse. OTPs can develop comprehensive treatment regimens to bring patients in for these concerns. In Northern Colorado, for example, several organizations support physical and occupational therapy practitioners in developing specialized pelvic health programs. If you work in outpatient and are interested in this area, I encourage you to speak with your supervisor about creating a program that addresses these needs.

We’re all skilled at taking a holistic approach, tying together ADLs and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) with patient-specific needs. Even if you’re a hand therapist, it might not immediately seem like incontinence is on your radar—but consider the impact of functional incontinence on a patient’s overall ability to manage their routines. It might affect how they perform tasks or handle self-care, so it’s worth integrating this perspective into your assessments.

Additionally, I recommend using educational tools in our outpatient settings. Displaying information in our buildings and bathrooms can be a simple yet effective way to raise awareness and educate patients about managing bowel and bladder health. By doing so, we can help patients understand that addressing incontinence isn’t isolated from the rest of their care—it’s a vital component that contributes to their overall function and quality of life.

The bottom pictures (Figure 5) show how simple modifications can turn everyday spaces into learning opportunities. Originally, the bottom image shows a basic print from a store in the bathroom. I asked if I could cover it up with educational information about incontinence. My goal was that when people sit on the toilet, they might also absorb helpful insights about managing their condition.

Figure 5. Examples of how to show educational material.

Advancing Practice Areas

I also encourage you to consider advancing your practice areas. So much beautiful work is happening in pelvic health, and occupational therapy practitioners willing to get creative and take initiative can explore many different avenues. For instance, you might choose to move into obstetrics or pediatrics, much like I have by concentrating on pelvic health in children. A children's hospital has approached me to provide treatment for kids, and I've also seen opportunities in neurology clinics.

Another effective strategy is to connect with primary care physicians for referrals and even offer educational sessions to them. One of my previous students is now working with the military, developing an entire treatment regimen to support pelvic health for women and likely men. There are countless possibilities to expand your scope in this area.

If you're excited about pelvic health and eager to be more creative, I suggest following those breadcrumbs of ideas to move your practice forward. I highly recommend Leslie Howard's book Pelvic Liberation: Using Yoga, Self-Inquiry, and Breath Awareness for Pelvic Health; it's an excellent resource that takes these concepts to the next level.

Lean Into Learning

Continuing education is essential. I’ve found that engaging in in-person learning opportunities makes a significant difference. For example, the Pelvic Health Summit—a conference initiated by one of my previous students and another occupational therapy practitioner—provides a hands-on environment to deepen our understanding of the pelvis. If that interests you, you can even learn to perform internal examinations at this summit.

Some occupational therapy practitioners might hesitate about incorporating these techniques into their practice, thinking, “Oh gosh, I can’t do that.” But the reality is that you absolutely can with proper education and demonstrated competency. Expanding your pelvic health skills enhances your ability to treat patients and opens up opportunities for more advanced interventions.

Consider this a little food for thought and a nudge to continue your learning journey in pelvic health.

Next Steps/Treatment

We've now covered the different types of incontinence and what they look like, and I’m excited to transition into discussing treatment. This part energizes me during continuing education sessions—I’m always eager to implement new strategies. I’ve built up a collection of resources that I keep on my clipboard, and if you use a tablet, it’s even more convenient to pull up these materials during sessions with patients. I also find that having handouts and questionnaires as leave-behinds can be very effective. For instance, a handout on bladder health or a bladder health questionnaire gives patients a chance to engage with the material between visits. When you review these tools together at the next session, they not only provide you with useful talking points but also help gauge the patient’s buy-in to the treatment plan.

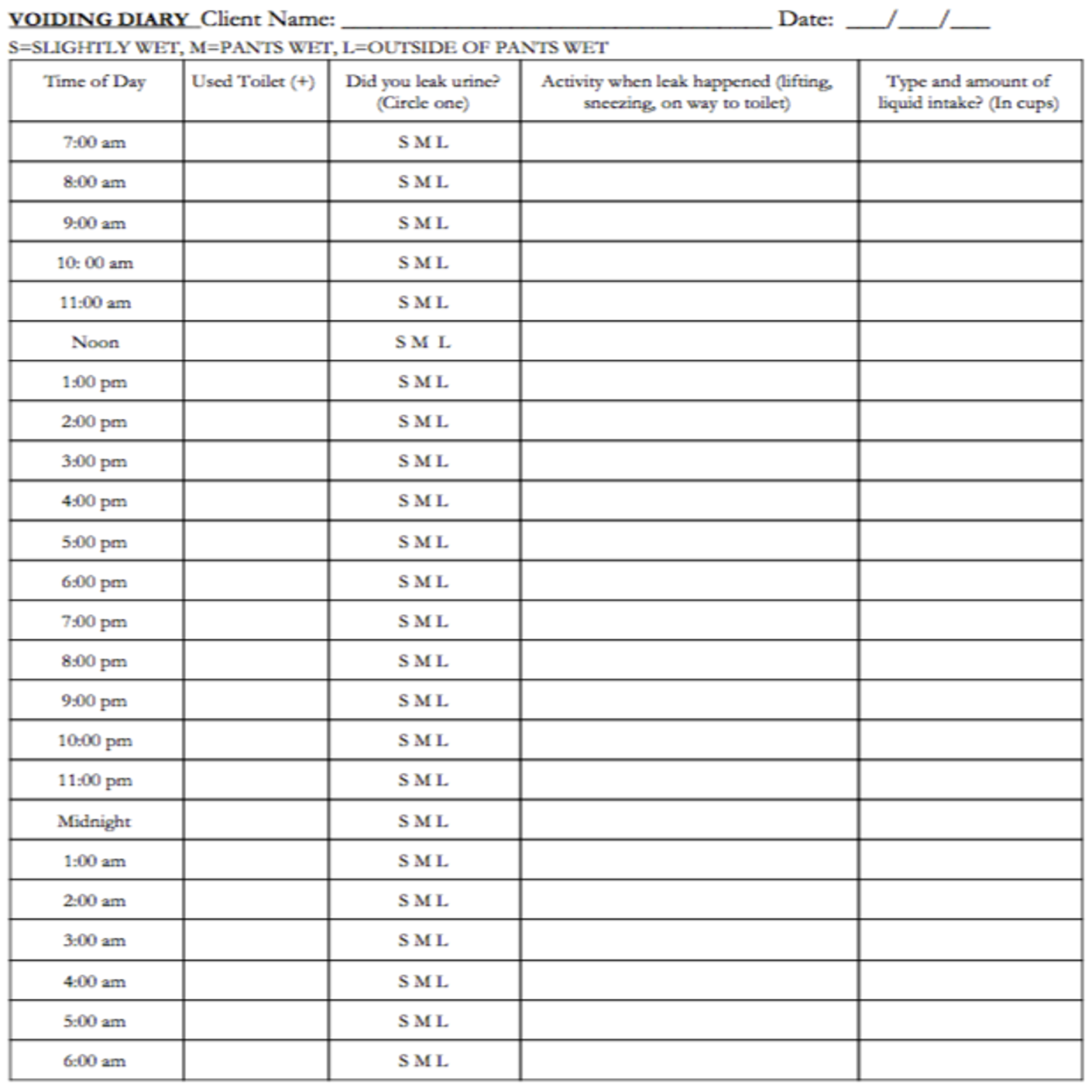

Today, I will touch on key areas: positioning in the bathroom, maintaining a voiding diary, and introducing pelvic exercises and “down training.” Positioning is crucial, whether using a footstool or a simulated squat to facilitate voiding. A voiding diary helps track patterns, which can then inform adjustments to their routine. And, of course, pelvic floor exercises and down training are essential components of the intervention, designed to build awareness and control.

All these strategies are part of a comprehensive approach to incontinence treatment. Combining education, hands-on practice, and consistent follow-up can make a real difference in our patients' lives.

Positioning

Here are some examples of toilet positioning shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Proper and improper positioning. (Image: Continued (licensed from Getty Images)

Consider the example of a patient sitting upright and reading a book while on the toilet. When someone sits completely upright, their pelvis is disadvantaged for evacuating the bowels. I often remind my patients that by leaning forward and elevating their knees—by, for instance, using a footstool or a device like a squatty potty—they can create a more favorable position for bowel evacuation. Although I don’t sell squatty potties, you’ve probably seen them in stores like Target. A nurse once presented the concept on Shark Tank, and one of the sharks invested, leading to the widespread availability of these products.

I encourage patients to try simple modifications such as leaning forward, placing their elbows on their knees, and bringing their knees up slightly. These changes can significantly improve their ability to evacuate, especially after surgery or during times when getting things moving is critical.

Now, I’d like to share a video featuring Pam, an OT assistant who serves as a patient. You might recall her from a previous image on a toilet in China. In this video, Pam illustrates the proper positioning and how these adjustments can facilitate better bowel evacuation. Let’s watch the video together.

Video

Here we have Pam. She had her knee replaced two weeks ago.

Eight days ago, I had the opportunity to work with Pam—one of our OT assistants—who was just beginning to adapt to her new knee after surgery. Like many post-operative patients, she was experiencing some constipation, so I wanted to demonstrate a good sitting position on the toilet that could help ease the process of evacuation. Pam sat upright with her hips at a 90-degree angle in her usual position, which isn’t ideal for bowel movements. I explained that she could adopt a more squat-like position by leaning forward slightly, placing her elbows on her knees, and drawing her feet back as much as possible. This change in posture helps the pelvis tilt in a way that aligns the colon and facilitates a smoother bowel movement.

I’m very grateful to Pam for being willing to model this for us. As an OT assistant, she might not have imagined she’d also serve as a demonstration model for constipation management on the toilet, but her participation was incredibly valuable.

This concept isn’t limited to managing constipation after surgery. For instance, I currently work with a patient who has stage four prostate cancer with multiple pelvic tumors. He’s had a lot of difficulty voiding because the usual position forces him to strain excessively, which has led to painful hemorrhoids and tissue damage. For him, we had to get creative. Instead of a typical sitting posture, he found that standing in front of the toilet, leaning forward dramatically, and resting his head against the wall provided the support he needed. With the assistance of his walker—positioned to slide over to the toilet—this modified stance allowed him to void more effectively and reduced the risk of further injury.

The key takeaway is that positioning is a powerful tool in our therapeutic arsenal. While the squat position works well for many patients, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. We must be creative—whether that means using a footstool, a urinal, or even adapting the position for someone unable to use a standard setup—to achieve the best alignment for voiding.

Voiding Diaries

Figure 7 shows a voiding diary.

Figure 7. Example of a voiding diary.

In my practice, I routinely use tracking tools with nearly all of my patients who are dealing with pelvic health issues—whether it's bladder or bowel incontinence or even constipation. I've noticed that many patients swing between experiencing bowel incontinence and constipation, so it's important to address both aspects when evaluating and planning treatment.

At Covell Care, we use a simple tracking form, and I'm happy to share this resource—it’s not copyrighted, so feel free to modify it as needed. The idea is to have patients record their toileting habits for three consecutive, typical days. I always advise scheduling this when nothing unusual happens, like before a high school reunion, so the data reflects their normal routine. The form is designed for 24 tracking hours, with entries made by the hour. For example, if patients use the bathroom at 9:30, they can record it as either 9 or 10—whatever is closest to the actual time. The goal is not overly precise but to gather useful information to build patient buy-in.

On the form, patients mark the time of each bathroom visit, noting whether they experienced any leakage. They can indicate if it was a slight leak, a moderate amount, or a significant loss—perhaps even noting if their pants became wet. While I sometimes circle that information if it’s important for a particular patient, basic tracking is often sufficient. Additionally, I include sections for recording activity during leakage and details about their liquid intake in cups. Some patients are very diligent with this, while others are less so, but overall, it provides me with a clearer picture of their patterns.

I also customize these forms for patients with low vision by using large print and high-contrast colors, and I provide a sturdy plastic clipboard that they can keep in their bathroom as a reminder. Since toileting is a routine, almost automatic activity, patients often don’t realize how quickly the details slip from memory. Leaving a clipboard in their bathroom encourages them to complete the form consistently, which can also be assisted by a caregiver or nursing staff. While the information might be gathered differently in skilled nursing settings, this extra detail often gives me valuable insights that shape my treatment plan.

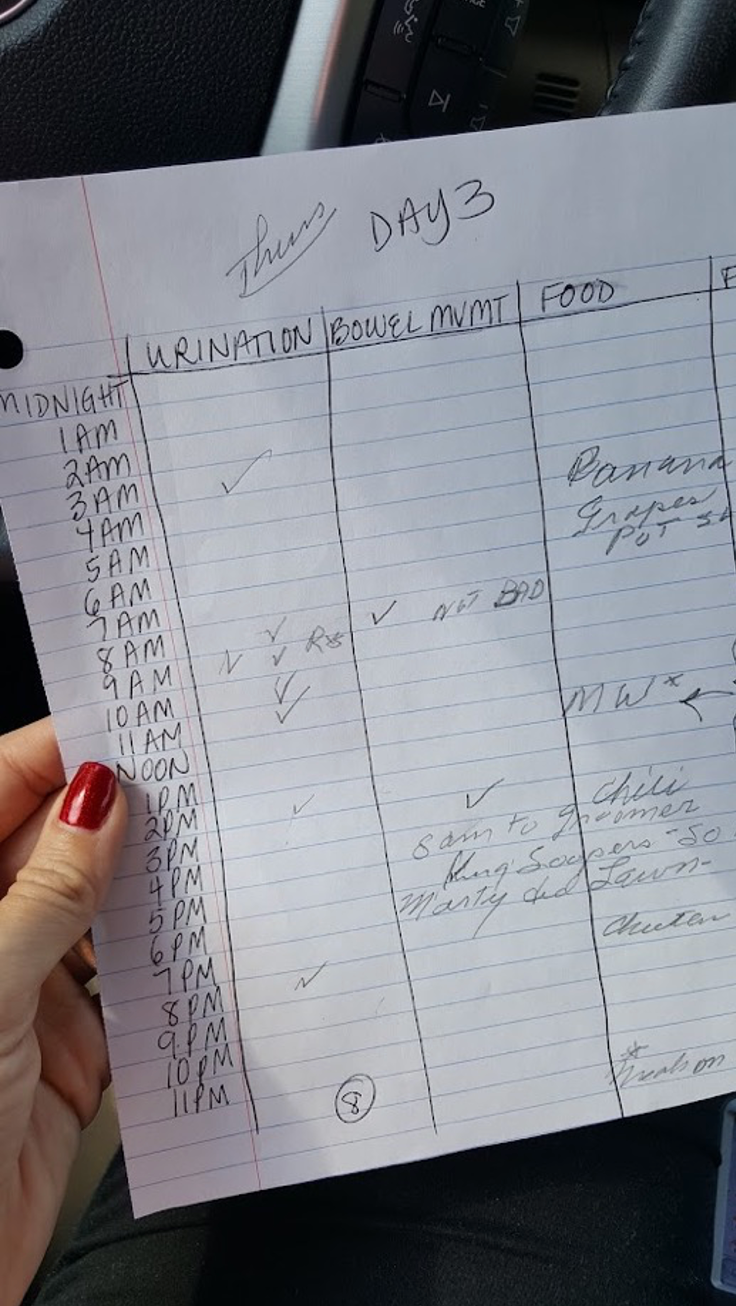

In Figure 8, I have another simple example—a piece of loose-leaf paper that I sometimes use to simplify the process even further for patients who might be overwhelmed by a more complex form. The key is to make it as straightforward as possible so that the tracking becomes a helpful part of their routine rather than a burden.

Figure 8. Informal voiding diary.

I reviewed the collected data on day three of tracking my patient's urinary and bowel habits. I compared her current patterns to what we consider normal. For instance, I noted that she went to the bathroom eight times during the day, which falls within the typical range of six to eight visits. However, when I look more closely at the timing, I see that after a 3 a.m. visit, she didn’t go again until 8 a.m.—a gap of more than four hours. Then, suddenly, she had four consecutive visits in a short span. This pattern raises questions about whether she is voiding completely since, ideally, there should be at least two hours between urinary voids.

In addition to tracking urination, I also record bowel movements and food intake. For example, she noted a bowel movement at 8 a.m. with a comment of “not bad.” She documented her meals—Panera, grapes, and potato salad—which allowed me to look for potential correlations between her diet and any leakage episodes. In her case, it's clear that she experiences leakage every single time she goes to the bathroom; I don’t even need to ask her because the tracking consistently shows that her pants are wet, though not always completely soaked.

Later in the day, at 2 p.m., there’s another notable gap until her next urination at 8 p.m. Patterns like these provide a wealth of information. When I sit down with my patients to review their diaries, I often create an entire visit just to discuss their routines and patterns. It’s eye-opening for them when they see, for example, that they’re going to the bathroom so frequently, and it helps us pinpoint potential issues.

I also want to share a particular case that illustrates the power of tracking and making small lifestyle changes. I once worked with a woman living independently who had a very early start to her day—she would get up at 4 a.m. and develop a routine that involved drinking a Diet Pepsi every morning. Unfortunately, this habit was correlated with an explosive loss of both urine and bowel contents before breakfast. When I reviewed her tracking data, the correlation was undeniable.

I asked her if she would be willing to give up her Diet Pepsi for just three days. I knew asking someone to eliminate a favorite beverage could be tough, but she agreed to the trial. I even brought a case of Diet Pepsi to her room as a visual reminder of the habit we were addressing. After those three days, she reported that she no longer experienced any accidents. It was a rewarding moment for both of us, as such a simple change made a huge difference in her quality of life.

These examples underscore the importance of detailed tracking and the insights it can provide. I can tailor my treatment plans by analyzing when and how often my patients use the bathroom, the type and amount of leakage, and correlating these events with diet and other behaviors. This data informs my clinical decisions and empowers patients to make meaningful changes in their daily routines.

Assessments

These assessments are used across various settings to gather information on a patient’s incontinence, but it’s important to remember that many of these tools are designed primarily to capture the burden of care rather than to assess functional performance or the impact on a patient’s life. For instance, in-home health, you might be completing the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS), which tells you whether a patient is incontinent and outlines some associated issues. However, it doesn’t fully capture whether incontinence prevents them from leaving the house or affects their quality of life.

In skilled nursing facilities, nursing staff often complete documentation, which may reflect their perspective of the patient’s continence status. As OTPs, we need to ensure that our documentation complements that of nursing. If there’s a discrepancy—say nursing reports a patient as a continent while we observe incontinence—it’s critical to collaborate and reconcile these differences to provide an accurate picture of the patient’s functional status.

For inpatient settings, such as inpatient rehabilitation facilities, the Patient Assessment Instrument is commonly used. This instrument, too, tends to focus on the burden of care aspects, such as the number of briefs used or the frequency of toileting assistance, rather than on the patient’s functional performance. To address this gap, there are additional tools available. For example, the Urinary Incontinence Assessment and the Overactive Bladder Assessment Tool are more functionally oriented. These instruments document the extent of incontinence and help assess the patient’s ability to manage voiding independently, thereby providing insights into how incontinence affects their daily function.

Treatment: Bowel Incontinence

Once we move past the voiding diary and other tracking tools, the next step is to look at bowel issues. I often emphasize this because, as my experience has shown, bowel function and urinary incontinence are interrelated. Take the case of my patient, who used to have explosive losses of both urine and stool in the morning. When we addressed her Diet Pepsi habit—a habit that contributed to her overactive bowel issues—her bowel incontinence improved dramatically, and subsequently, her urinary incontinence became much less pronounced. In my words, and perhaps not the most politically correct way to put it, “poop drives the pee.” The urinary system often follows suit if the bowel is not functioning properly.

This reinforces the importance of addressing bowel issues first in our treatment planning. By gathering comprehensive information through assessments and collaborating with nursing staff, we can create a treatment plan that reduces the burden of care and improves the patient’s functional performance and overall quality of life.

When reviewing a voiding diary, if I notice that a patient is managing their bowel function relatively well, I can focus more intently on the urinary component of their treatment plan. Often, I observe a fluctuation between incontinence and constipation. This can occur because patients might use medications to manage their bowel movements—perhaps taking an over-the-counter agent to bulk up loose stools one day and then using a different medication to loosen them up when they’re experiencing constipation the next. This seesaw effect is something I keep in mind during treatment planning.

It’s important to remember that, as therapists, we aren’t doctors. I don’t give direct advice about changing medication schedules or frequencies. Instead, I focus on our interventions and then discuss any observed changes or concerns with the patient’s physician. If a patient is taking an over-the-counter medication to regulate their stool, and I notice an improvement in their regularity, it might suggest that their regimen is working well. However, if a medication has been prescribed at a certain time, I ensure not to interfere with that plan. Rather, I collaborate with their doctor to make functional improvements.

I also use tools like the Bristol Stool Chart to inform our discussions further. I review the diary with my patients and ask them to describe the appearance of their bowel movements, using the chart as a reference. This helps me understand their current bowel function and opens up the conversation about whether adjustments in their routine might be necessary. By combining information from the voiding diary and the Bristol Stool Chart, I can better tailor my treatment approach, and it also becomes a valuable educational tool for the patient and the referring physician.

Bowel Irritants

In my practice, I also make it a point to review dietary habits and identify potential bowel irritants contributing to incontinence. I explain to my patients that certain foods can sometimes exacerbate bowel issues. For example, greasy foods like chicken wings can be a trigger, as can foods that a patient may already know they are sensitive to—such as dairy for someone lactose intolerant. Instead of suggesting they completely eliminate ice cream or other favorite treats, I often recommend a more moderate approach, such as reducing the portion size from three scoops to one scoop, to see if that makes a difference.

I also inquired about other dietary components that might be problematic. Spicy foods and certain sugar replacements like Splenda can sometimes irritate the bowel, so I ask patients what they’re putting in their drinks or consuming with their meals. Caffeine, particularly from coffee, as well as dairy products, garlic, onions, broccoli, cauliflower, fast food, and alcohol, are also common culprits that might worsen bowel incontinence for some individuals.

The key here is not to dictate what they must or must not eat—after all, food is a source of enjoyment and comfort—but to offer suggestions to improve their symptoms. By gently guiding patients to consider modifications in their diet, I help them explore changes that might lead to better bowel control. This collaborative, nonjudgmental approach respects their preferences and lifestyles and empowers them to take control of their pelvic health.

Constipation Agents

I explain to my patients that certain foods and dietary habits can lead to constipation, and I work with them on making modifications that suit their individual needs. For instance, foods made with white flour, processed meats, and fried items are common culprits. Dairy is another factor—it might contribute to incontinence in some people or cause constipation in others, so it depends on the individual's response.

I emphasize that these dietary triggers are highly person-specific. One patient might find that a particular food exacerbates their symptoms, while another might not be affected at all. In addition to these foods, I always discuss the importance of staying well-hydrated, as dehydration can worsen constipation.

Stress is another major factor I consider. By the time many patients come to see me, their stress levels are often quite high, which can contribute to constipation by making the stool sticky and reducing fiber intake. I also discuss ways to manage stress and increase dietary fiber. This combination—dietary modifications, proper hydration, and stress management—can help improve bowel function and, in turn, positively impact overall pelvic health.

Addressing Fiber

I often explain to my patients that fiber is essential for healthy digestion, yet many of us never received much education during our occupational therapy training. When food passes through the intestines, our bodies absorb what they need and leave behind the rest. This undigested material forms stool and its bulk helps stimulate peristalsis—the muscle contractions that move food through the gut. Essentially, the more bulk your stool has, the easier and faster it will move. If the stool is too loose, it can pass through too quickly, leading to issues like diarrhea and, for some patients, even incontinence.

There are two main types of fiber to consider: soluble and insoluble. Soluble fiber dissolves in water and can slow the digestive process, which helps stabilize blood sugar levels. Insoluble fiber doesn’t dissolve in water; it remains mostly unchanged and adds bulk to the stool. Both types play a role in maintaining healthy bowel movements. I encourage my patients to gradually increase their fiber intake—ideally aiming for about 25 grams per day for adults—though this can vary based on individual needs.

I often use tools like fiber logs or calendars as tracking instruments to support this. For example, I might give a patient a calendar and ask them to note the amount of fiber they consume daily, or use a handout from reliable sources like the Mayo Clinic, which clearly outlines fiber content in common foods. I explain how a slice of bread might provide around 2 grams of fiber, whereas a cup of raspberries could offer about 8 grams. This helps patients make more informed choices—like opting for raspberries if they're aiming to boost their fiber intake.

For tech-savvy patients, free apps allow them to keep a digital fiber diary, though some may prefer the simplicity of pen and paper. The goal is to have them assess their current intake and then gradually increase it without overwhelming their system. It’s important to advise them to proceed slowly, as a sudden jump to 30 grams of fiber in one day can upset the stomach. Instead, I help them identify small, manageable changes—perhaps adding a serving of vegetables or a high-fiber snack to their meals.

Additionally, I encourage patients to read food labels and understand the fiber content of the foods they purchase. For those in independent living or similar settings, reviewing the menu and selecting high-fiber options is another practical strategy.

I also stress that it may take a couple of weeks to notice significant changes in bowel function as their fiber intake increases. Consistency is key. Over time, a balanced increase in fiber not only reduces constipation but can also improve incontinence by helping regulate stool consistency. It’s a holistic approach that benefits overall pelvic health.

In summary, by educating patients on the role of fiber and providing them with practical tools—whether a simple handout, a fiber log, or a digital diary—I aim to empower them to make gradual changes in their diet. This collaborative process enhances their digestive health and supports better management of both bowel and bladder function.

Figure 9 shows two examples of fiber stations.

Figure 9. Examples of fiber stations.

On the left, I have a case example of a patient I saw after surgery. She was able to organize her kitchen so that increasing her fiber intake became part of her safety routine with her new walker. We worked together to identify and gather high-fiber options that she already had at home, arranging them in a “grab and go” manner. This way, when she entered her kitchen, she didn't need to rummage through cupboards or the refrigerator to find a healthy option; everything was conveniently accessible.

On the right, I’d like to share another example from an assisted living facility with memory care. One patient, a big snacker, used to help herself to a little candy dish in her small kitchenette—even though it didn’t have an oven or many cooking appliances. She was consuming a lot of chocolates, which wasn’t ideal for her. In collaboration with the care team, we removed those less healthy options and replaced them with items better suited to her dietary needs. For instance, we introduced a personalized linen bag that contained healthier snack alternatives. She was also experiencing loose stools, so we added bananas to her routine, which helped manage her bowel function.

These examples illustrate how small, practical modifications—tailored to the patient's environment and personal habits—can significantly impact their dietary intake and overall pelvic health.

Modifying Bowel Routines

When modifying bowel routines, I often discuss the gastrocolic reflex with my patients—a natural response in which the intestines contract after eating or drinking. For example, many people notice that having coffee triggers the need for a bowel movement. I use this concept frequently, especially with patients who have conditions like ALS or MS, where this reflex may no longer be automatic.

I recall one patient with ALS who lived alone and received periodic caregiver visits. Before integrating a structured bowel routine, she would sometimes wait in the bathroom for her caregiver or even call EMTs when she had a bowel movement and couldn't get assistance. We incorporated a high-fat breakfast option into her morning routine to address this. Instead of relying solely on hot coffee or tea, we provided her with hot water and lemon—something gentle on her system but still effective at triggering the gastrocolic reflex.

Her caregiver would serve her this breakfast at a set time, help her prepare for the day, and guide her to the toilet. She would sit for about 20 to 25 minutes, which allowed enough time for a bowel movement to occur naturally. This routine significantly reduced her episodes of incontinence, minimized her risk for skin breakdown, and helped maintain her dignity, ultimately enabling her to stay home longer.