Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar Introduction To Breastfeeding And The Role Of The Occupational Therapy Practitioner, presented by Jennifer L. Campanella, OTD, OTR/L, CBS.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify 2 challenges and potential solutions when breastfeeding difficulties arise due to the anatomy and physiology of the mother.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify 2 challenges and potential solutions when breastfeeding difficulties arise due to the infant's oral anatomy and sucking patterns.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the occupation of breastfeeding and identify 2 roles of the occupational therapy practitioner.

Introduction

I have been an early intervention occupational therapist for over 25 years, specializing in sensory processing and feeding concerns. My experience and passion for supporting children and families led me to pursue SIPT certification. In 2021, I became a certified breastfeeding specialist, driven to bridge the gap between breastfeeding and transitioning to bottle-feeding or solid foods. My goal has always been to support the infant and their family through these crucial stages, helping address feeding issues and create smoother transitions.

Agenda

We will explore the anatomy and physiology of lactation, what to do when challenges arise, and examine the critical role of the occupational therapy practitioner (OTP) in addressing these difficulties. We will also dive into infant oral anatomy, focusing on managing challenges in this area and considering the occupational therapy practitioner's role in supporting the infant and family through these concerns. Lastly, we’ll finish by discussing breastfeeding as an occupation, with time for questions and answers to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the topics covered.

Anatomy and Physiology of Lactation

The anatomy and physiology of lactation are fundamentally driven by the infant's appetite and ability to effectively remove milk from the breast. This process creates a positive feedback loop for the mother and the baby. For the mother, as the baby sucks, the hormone prolactin is produced, stimulating milk production. The more the baby sucks, the more prolactin is released, leading to increased milk production and, consequently, more breastfeeding opportunities.

On the baby's side, a similar feedback loop occurs. As infants feed, they become more alert, hydrated, and stronger, which fuels their hunger and encourages them to feed more. This continuous cycle promotes growth, alertness, and participation in feeding, reinforcing the connection between successful breastfeeding and the infant’s development. The more infants are fed, the more strength they gain, further supporting their health and the mother’s milk production.

Uniqueness of the Mammary System

The mammary system is unique in that its development is unlike any other organ in the human body. It begins forming in utero while the mother is still a fetus and continues to evolve through distinct life stages—birth, puberty, pregnancy, and lactation. Interestingly, full mammary development is only achieved when a woman becomes pregnant and begins lactating. This means that women who do not have children or choose not to breastfeed may never experience complete mammary development.

For these women, the mammary glands remain at a partial developmental stage, as the physiological changes required for full maturation only occur in response to the hormonal and physical demands of breastfeeding. This highlights how intricately the anatomy and function of the mammary system are tied to the reproductive and nurturing phases of a woman's life, adapting to meet the needs of both mother and child during lactation.

4 Phases of the Mammary Gland Development

The mammary system has four phases of development. The first phase is mammogenesis. The second phase is lactogenesis, which is divided into two different stages. The third stage is galactopoiesis, and the fourth stage is involution. We will examine each of those stages in more depth.

Mammogenesis. The first stage is mammogenesis, which begins in utero and continues throughout pregnancy. During this extended development period, the mammary glands grow significantly in size and weight. As the woman’s breast enlarges, hormonal changes start to take place, especially during pregnancy. There is an increase in hormones such as estrogen, lactogen, and progesterone, all of which contribute to the growth of ducts and glandular tissue within the breast. This expansion and preparation are essential for future milk production.

Lactogenesis. The second phase is lactogenesis, which consists of two distinct stages. The first stage, known as lactogenesis I, begins around mid-pregnancy, typically at about 20 weeks gestation, and continues through the first two days postpartum. During this time, the alveolar cells in the breast start to differentiate and transform into secretory cells, a process that readies the breast for milk production. This transformation occurs gradually throughout pregnancy and continues for a few days after delivery. Once the alveolar cells shift into secretory cells, prolactin stimulates them, initiating colostrum production. The body prepares to produce milk from mid-pregnancy until around two days postpartum.

Lactogenesis II is a shorter but crucial stage, beginning around day three postpartum and continuing through day nine. During this period, the secretory cells activate fully, transforming into secretory activation cells. This is when a significant drop in progesterone levels triggers an increase in milk production. Many mothers consider this stage when their “milk comes in.” However, milk production can be somewhat inconsistent during this time, fluctuating levels as the body adjusts to meet the infant’s needs. In this transitional stage, the breasts stabilize milk secretion in preparation for ongoing lactation.

Several factors can delay lactogenesis. For instance, mothers who have undergone a C-section may experience disruptions in normal hormonal levels, which can interfere with the onset of lactogenesis. The hormone changes and the effects of anesthesia and medications often delay milk production. Maternal stress, whether related to a C-section or in general, can also impede the timely start of lactation. Other potential causes include advanced maternal age (mothers over 35), placental retention, and a history of breast surgeries, which may impact the breast tissue’s ability to produce milk.

An essential concept during lactogenesis is the transition from an endocrine-driven to an autocrine-driven system. Initially, lactation is controlled by hormonal changes: the drop in progesterone, the rise in prolactin, and the delivery of the placenta. However, as lactogenesis progresses, the system shifts to being regulated by milk removal, primarily baby-driven. The infant’s suck-swallow response becomes the primary factor driving milk production rather than hormonal fluctuations.

Galactopoiesis. The third stage is galactopoiesis, which begins around day nine postpartum and continues through the duration of breastfeeding, up until the final stage of involution (the end of breastfeeding). The ongoing maintenance of milk production characterizes galactopoiesis. By this point, a mother’s milk supply has stabilized, producing an amount that meets the infant’s needs based on the principle of supply and demand. Instead of establishing milk production, this stage is focused on maintaining a steady supply.

It is crucial during galactopoiesis to ensure adequate milk removal, as any disruption—whether due to feeding difficulties, changes in the baby's feeding patterns, or other external factors—can lead to a decrease in milk production. During this period, and typically by around six to nine months, the breasts may begin to decrease in size as they shift back towards their pre-pregnancy state, reflecting the adjustment in milk production to meet the infant’s needs. This stage sets the foundation for sustaining breastfeeding over the long term.

Involution. The final stage is involution, which marks the process of the breasts returning to their non-lactating state. This stage begins with the last breastfeeding session and lasts about 40 days. During this time, the body gradually reduces milk production, and the mammary glands slowly return to their pre-lactation condition. Even though active breastfeeding has ended, small amounts of milk may still be produced, and hormonal changes continue until the mammary tissue fully transitions back to its non-lactating state. This involution period signifies the end of the lactation process, allowing the breasts to return to their pre-pregnancy structure and function.

Challenges With Lactation

Numerous challenges can arise with lactation, and it’s important to recognize some of these to provide effective support. When assessing lactation, the focus is primarily on the mother. As a breastfeeding specialist and therapist, one of the first steps is conducting a breast assessment. This can be done in different ways depending on the comfort level of both the practitioner and the mother. It might involve a physical evaluation or be more informal, taking place through conversation and careful observation. The key is establishing a safe, supportive environment where the mother feels comfortable discussing her concerns and experiences.

Breast Assessment

It’s essential to understand that the size and shape of a mother’s breasts have little to do with how much milk she can produce. Small and large breasts can provide sufficient milk for an infant. Similarly, breast symmetry does not typically affect lactation. Almost every mother will have some degree of asymmetry between the right and left breast, which is normal.

However, a noticeable or significant asymmetry, either visually observed or reported by the mother, could indicate an underlying issue, such as insufficient glandular tissue, which may impact milk production. Another potential concern is breast hypoplasia, characterized by a wide space between the breasts. When a mother’s breasts are engorged with milk, they should generally appear closer together. If there is a wide separation, with a prominent view of the breastbone or sternum, it could suggest a lack of adequate breast tissue. These signs warrant further evaluation and may require referral to a healthcare professional with specialized expertise in lactation.

For mothers with very large or engorged breasts, finding a well-fitting bra is crucial to help support the weight, maintain milk supply, and ensure comfort. In these cases, adjustments to breastfeeding positions might also be necessary, as larger breasts can pose unique challenges for both the mother and infant during feeding. Creating individualized strategies to accommodate these variations can greatly enhance the breastfeeding experience and promote successful lactation.

Classification of Nipple Function

Another common set of challenges with lactation involves nipple function, which can vary and may present unilaterally or bilaterally. Ideally, when a baby begins to nurse, the nipple should protract, moving forward as the infant latches and begins to suck. This protraction is necessary for a good latch and effective milk transfer.

However, when the baby starts to nurse and then releases, the nipple might remain retracted instead of protracting as expected. This retraction can range from mild to severe. Without proper protraction, the infant may struggle to latch effectively, interfering with feeding. In mild cases, some babies may be able to stimulate the nipple to move forward through their sucking patterns, but when the nipple remains fully retracted, this can indicate a more complex issue known as inversion.

Nipple inversion is the most severe form of retraction, where part or all of the nipple is completely withdrawn into the areola. When this happens, the nipple is not visible, leaving the baby without a point of contact to initiate a proper latch. Depending on the extent of inversion, some therapeutic techniques can be applied. For example, gentle manual pressure around the areola may encourage the nipple to move forward. Discussing these techniques with the mother can be empowering, as she can learn how to use manual stimulation to help facilitate protraction.

Additionally, applying cold compresses may sometimes draw the nipple out of its inverted state, providing enough protraction for the infant to establish a latch and, ideally, sustain a good feeding pattern. While these approaches may help in mild to moderate cases, more severe inversions may require additional support and should be referred to a lactation specialist or healthcare provider.

Beyond nipple issues, ensuring a well-fitting bra can also be beneficial for maintaining overall breast health and comfort during lactation. Proper bra support and individualized guidance on managing retraction or inversion can significantly support successful breastfeeding.

Occupational Therapy Practitioner's (OTP) Role in Lactation

Occupational therapy practitioners can play a vital role in supporting lactation by addressing mothers' physical, emotional, and educational needs. One of the primary areas of focus is prenatal counseling and education. Mothers must know what to expect before they begin breastfeeding so they can recognize what is typical and what might indicate a problem. Prenatal education helps mothers feel empowered and prepared, giving them the confidence to ask questions or seek assistance. This early intervention is part of a wellness-based approach occupational therapy practitioners can offer families.

Once lactation has begun, OTPs can continue educating mothers about when they might need additional help from a physician or lactation specialist, ensuring they know when to involve another professional for more complex issues. OTPs can also guide nutrition and hydration, discouraging calorie-restrictive diets, which many new mothers may consider to return to their pre-pregnancy weight. It’s important to emphasize that breastfeeding can burn up to 500 calories daily. Mothers are recommended to consume 350 to 400 calories to support lactation while allowing for gradual weight loss without compromising milk supply or health.

Proper hydration is another key component. While water is important, other healthy fluids like juices or teas can contribute to overall hydration and support milk production. In addition to physical wellness, sleep, and relaxation are essential aspects of health during lactation. OTPs can provide training in mindfulness techniques, yoga, or relaxation exercises to help mothers manage stress, which is known to negatively impact milk production.

Pumping can also be beneficial for maintaining milk supply, especially if there are gaps between feedings. OTPs can educate mothers on using pumps effectively, suggesting they pump after regular feedings or between nursing sessions. This additional stimulation can help sustain milk production and prevent a drop in supply.

Another important intervention is skin-to-skin contact, or “kangaroo care.” This technique, which involves placing the baby directly on the mother’s bare chest, enhances bonding and helps regulate the infant’s body temperature and heart rate. Skin-to-skin contact is recommended immediately after birth and can continue as long as the mother is comfortable. Even as the baby grows, keeping the child close to the chest so they can hear the mother’s heartbeat and feel her warmth remains beneficial for bonding and can support continued lactation.

A key concept to convey to families is that no two mother-baby dyads are the same. Each mother and infant will have unique needs and preferences regarding feeding, so it’s essential to respect and support their individual choices. Whether the mother decides to exclusively breastfeed, pump and bottle feed, supplement with formula, or use formula entirely, the role of the OTP is to provide support without judgment.

OTPs also play a role in facilitating the mother’s transition into new roles. With each pregnancy and postpartum experience, a mother’s roles and responsibilities change significantly. Whether it’s her first child or her fifth, occupational therapy practitioners should be prepared to support her through these shifts and help her adjust to her new identity. This involves validating her feelings, letting her know that whatever she’s experiencing—joy, fear, exhaustion, or confusion—is normal and valid.

Another significant area for occupational therapy practitioners is assessing maternal mental health. Postpartum depression and baby blues are widely discussed, but knowing the difference between the two is essential. Baby blues typically begin around day three postpartum and can last for two to three weeks, affecting as many as 80% of new mothers. They are largely driven by hormonal changes and generally resolve on their own without the need for medical intervention. In contrast, postpartum depression involves more severe and persistent symptoms, including extreme sadness, loss of interest in activities, and even thoughts of harm. Postpartum psychosis, though rare, can also develop and requires immediate medical attention. Educating mothers about these differences and providing referrals when necessary is an important part of the OTP’s role.

Beyond supporting mental health, OTPs promote health and wellness by encouraging mothers to maintain a healthy diet, establish a consistent sleep pattern, and engage in stress-reducing activities. This holistic approach considers the mother's physical and psychosocial health, acknowledging the complex interplay between these factors during breastfeeding and lactation.

Lastly, connecting families to community resources is essential. Occupational therapy practitioners should know local organizations like La Leche League or other breastfeeding support agencies. Support groups can be invaluable for mothers seeking camaraderie and advice in person or online. Knowing where to direct mothers for reliable help can significantly impact their breastfeeding journey. If the OTP does not have specialized training in lactation, establishing a network of contacts, including lactation consultants or other specialists, ensures mothers receive comprehensive support.

Infant Oral Anatomy and Suck Swallow Patterns

The next section focuses on infant oral anatomy and the dynamics of their suck-swallow patterns. When an infant is latched onto the nipple, it’s important to consider specific anatomical landmarks such as the hard palate and soft palate. The hard palate is located in the mouth's anterior (front) portion, while the soft palate is positioned posteriorly (toward the back).

Additionally, we must be aware of the epiglottis and the larynx, which work together to help direct breast milk safely into the esophagus, preventing aspiration. Understanding the location and function of these structures, along with the position of the esophagus and trachea, is crucial in assessing the infant’s feeding mechanics and ensuring that milk flows properly without entering the airway. This anatomical awareness helps guide proper positioning and technique during breastfeeding to optimize safety and efficiency for the infant.

Infant Oral Anatomy

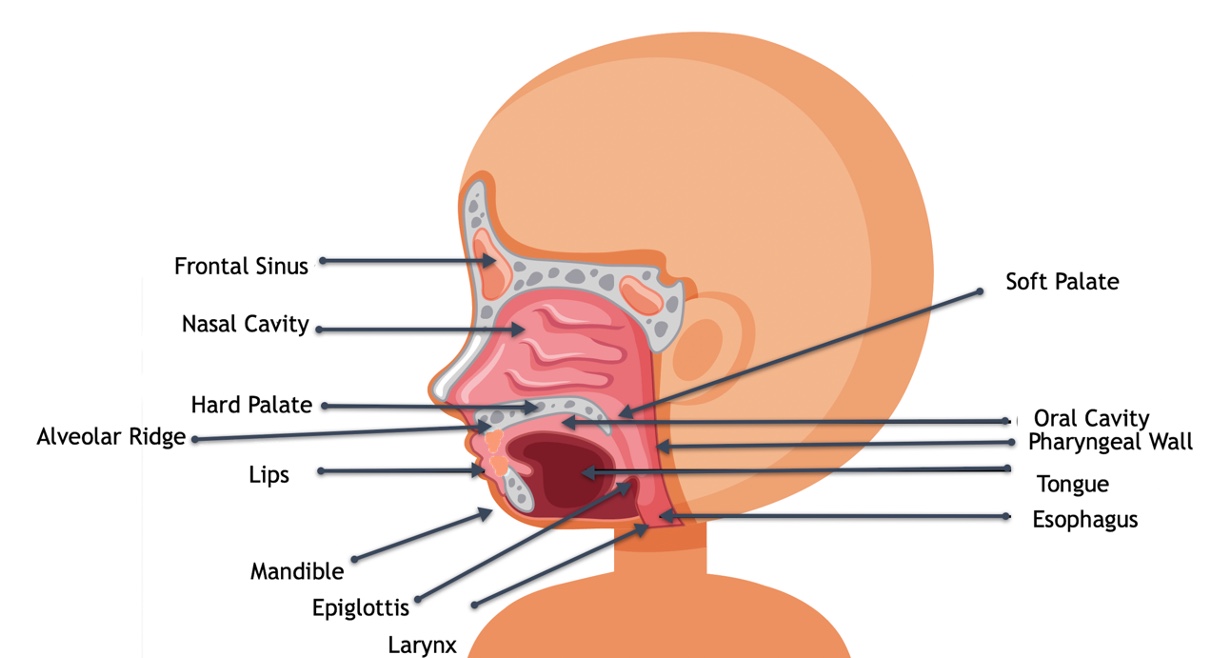

To provide an overview of infant oral anatomy, it’s essential to understand the unique characteristics of an infant’s mouth at birth (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Infant oral anatomy (Click here to enlarge this image.)

An infant’s mouth is vertically short and doesn’t open very wide. The tongue is large and wide, contacting the gums laterally and the roof of the mouth, filling up most of the oral cavity. This extensive tongue contact within the mouth is a typical and necessary part of their feeding mechanics.

Additionally, the hard palate in infants sits lower and tends to be broader than an adult's. The jaw is also smaller and somewhat receded, creating a slight overbite appearance because the lower jaw is set back. This recessed position is advantageous for breastfeeding, allowing the breast to fit more comfortably into the infant’s mouth. All these anatomical features work together, creating an oral structure uniquely designed to support effective latch and feeding during early infancy.

Palate

Looking at the palate more closely, an infant’s palate is short, wide, and slightly arched. In contrast, an adult’s palate is deeply arched and sits higher in the mouth. The anterior hard palate, located at the front, plays a crucial role in feeding by assisting the tongue in stabilizing the nipple during breastfeeding. The interaction between the tongue and the anterior hard palate creates a secure latch, helping the infant maintain an effective seal on the nipple.

The soft palate, positioned back in the mouth, seals off the nasal cavity from the oral cavity during feeding, ensuring milk flows efficiently without entering the nasal passage. This coordinated action between the hard and soft palates and the tongue is essential for safe and effective feeding.

Over time, the palate is shaped by the tongue's movements. An infant with a very high and narrow palate may show signs of potential difficulties. For instance, tongue tie could be a contributing factor, where a short frenulum restricts the tongue's ability to lift properly, preventing it from flattening and widening the palate as it should. Another possible cause of a high palate is low muscle tone, where the infant lacks the strength to raise the tongue sufficiently.

A high palate might indicate mouth breathing, a condition often associated with structural or functional issues in the oral or nasal cavities. These characteristics can provide important clues when evaluating an infant’s feeding mechanics and oral function, helping identify areas requiring further intervention or support.

Tongue and Lips

The tongue and lips are critical in stabilizing and creating a proper seal during feeding. As previously noted, the tongue fills most of the infant’s oral cavity, resting over the lower gums and extending slightly over the edge. The entire tongue is set within the oral cavity, and its movements are intricately coordinated with the jaw.

The anterior portion of the tongue moves in tandem with the jaw—when the jaw moves up, the anterior tongue follows, and when the jaw moves down, the tongue moves down as well. This coordinated movement ensures that the nipple remains stable and the latch remains secure during feeding.

The posterior portion of the tongue (from about mid-tongue to the back) has a unique motion pattern known as a peristaltic movement. This wave-like motion is crucial for effective milk transfer. As the tongue moves upward and downward, the wave motion creates alternating pressure changes within the oral cavity, which helps to initiate the milk ejection reflex. The positive pressure generated by these movements draws milk from the breast, while the changing pressure levels help carry the milk toward the back of the mouth for swallowing.

This combined action of the tongue and jaw ensures a proper latch and milk transfer and stimulates the ongoing milk ejection process, facilitating successful breastfeeding. Understanding these dynamics is essential for identifying any disruptions in feeding patterns and providing the necessary support to optimize oral function during nursing.

Epiglottis and Larynx

The epiglottis and larynx play a vital role in protecting the infant’s airway during feeding, and while their position and function cannot be altered through intervention, it’s important to be aware of their anatomical placement and purpose. The epiglottis is positioned low, just below the soft palate, which helps decrease the risk of aspiration by directing milk laterally. This means that the epiglottis slows the milk flow, preventing it from rushing too quickly down the esophagus, thereby allowing for safer swallowing.

In conjunction with the epiglottis, the larynx sits much higher in the oral cavity in infants than in adults. This elevated position allows the larynx to move up and under the base of the tongue during feeding. As the larynx elevates, it helps direct milk into the pharynx and down the esophagus instead of the trachea, minimizing the risk of milk entering the airway.

Together, the epiglottis and larynx seal off the trachea, ensuring that milk flows into the esophagus in a controlled and manageable manner. Their coordination is essential for airway protection, making safe and efficient feeding possible for the infant. If any concerns arise regarding the infant’s ability to manage milk flow or signs of aspiration (such as coughing, choking, or difficulty breathing during feeds), it is critical to seek further evaluation from a healthcare provider to ensure the infant’s safety during feeding.

Cheeks

The cheeks are a surprisingly important part of an infant’s feeding anatomy. If you’ve ever had the opportunity to gently press a finger into an infant’s cheek, you’ll notice that it feels much thicker than an adult’s—sometimes up to about an inch thick. This thickness comes from fat pads, which are crucial for effective suckling and sucking.

These fat pads provide additional stability and play an active role in creating the pressure and seal needed for successful feeding. They are located between the buccinator and masseter muscles, contributing to the strength and structure of the infant’s cheeks. When you see those chubby baby cheeks, they’re not just for looks—they have a functional purpose, helping the baby maintain a firm seal during feeding.

These fat pads prevent the cheeks from collapsing inward during sucking, allowing the infant to maintain a pursed lip position and generate the necessary suction for milk transfer. Stabilizing the tongue and cheeks ensures that the oral cavity maintains its shape and pressure, essential for efficient breastfeeding. Without these pads, infants would struggle to keep their cheeks firm and lips sealed, impacting their ability to create a strong latch and maintain a consistent feeding rhythm.

Sucking Patterns

By around 28 weeks gestation, the suck-swallow-breathe coordination in an infant is sufficiently developed, which is a crucial milestone. This is why babies born at 28 weeks or later often can initiate sucking movements, despite being premature. While it’s always ideal to carry pregnancies to full term, reaching the 28-week mark is significant regarding feeding capability. Babies born at this stage may not need mechanical feeding support because they can often begin the process of oral feeding independently.

As the baby progresses further in gestation, by 32 weeks, they have developed the capacity to coordinate the full sequence of sucking, swallowing, and breathing. At this stage, the pattern might look like: “suck, suck, suck—swallow—breathe.” This rhythm is essential for safe and efficient feeding. Remarkably, even though these infants are about two months premature, they can start exhibiting these coordinated bursts, demonstrating that their feeding mechanisms are already functioning.

Whether a baby is born prematurely or at full term, feeding begins with the rooting reflex. This reflex is triggered when the side of the baby’s cheek is stimulated, either by the mother’s hand, a bottle nipple, or the breast. The infant instinctively turns their head towards the stimulation, signaling the start of the feeding process. The rooting reflex leads to the baby opening their mouth wide, lowering the tongue, and bringing the tongue tip forward, preparing for a proper latch. This movement—where the mouth opens, the tongue drops down, and the tip slightly lifts—is essential for drawing the nipple into the mouth.

It’s important to note that a crying baby is not in an optimal state for feeding. When a baby cries, their tongue naturally elevates to the roof of the mouth, disrupting the ideal nursing position. Forcing a crying baby to latch will likely be unproductive and frustrating for both mother and infant. Instead, it’s best to calm the baby first, so their tongue can drop down, enabling them to establish a good latch and initiate the sucking pattern. Understanding these reflexes and patterns is vital for supporting successful breastfeeding and ensuring a positive feeding experience for both the baby and the mother.

Suck/Swallow Patterns

When milk is flowing adequately, the rate of a typical suck-swallow pattern is about one cycle per second. If the milk flow is lower, the baby may increase that rate to about two suck-swallow cycles per second. This faster pace is an attempt to stimulate the milk flow and encourage more milk to be released. When milk supply decreases, the baby compensates by increasing the suck-swallow rate, and when milk flow is sufficient or even abundant, it tends to slow down.

If there is a sudden increase in milk, and the flow becomes too rapid for the baby to manage, they will instinctively slow down their suck-swallow pattern. Healthy infants can adjust their sucking rate to regulate the amount of milk intake. For instance, a hungry baby may start feeding with a rapid, forceful suck-swallow pattern to quickly get the milk flowing. As the milk begins to satiate them, they naturally slow down to a steadier, more relaxed rhythm of about one cycle per second.

Conversely, if the mother has a strong letdown and milk is flowing too quickly, the baby might slow its suck-swallow rate significantly to manage the excess flow and prevent being overwhelmed. This self-regulation of the suck-swallow pattern is a key component in effective feeding, allowing the baby to control the pace it takes in milk and adjust according to the flow.

Non-Nutritive Suck

Non-nutritive sucking is a crucial behavior for infants and involves a sucking pattern where no milk is present. This often occurs at the beginning of a breastfeeding session, before milk letdown, as the baby stimulates the breast to initiate milk flow. It also happens when a baby is sucking on a toy, pacifier, or their fingers.

Non-nutritive sucking is typically faster than a nutritive sucking pattern, with a rate of about two sucks per second. It occurs in bursts of approximately six to eight sucks before the baby pauses to take a breath, creating a pattern like: suck, suck, suck, suck, breath—suck, suck, suck, suck, breath. These are smaller, quicker movements compared to those seen in nutritive sucking.

This type of sucking is essential for several reasons. It supports oral exploration, allowing infants to learn about their environment through their mouth, a primary sensory organ at this stage. Additionally, it serves as an effective method for self-soothing, helping babies regulate their emotions and calm themselves. This is why pacifiers can be beneficial, as they help train the sucking reflex while also providing comfort through the familiar, rhythmic motions of non-nutritive sucking.

Mechanisms of Infant Suck

The mechanism of an infant’s suck begins when the nipple and surrounding area are drawn deep into the infant's mouth. Once inside, the tip of the infant’s tongue rests over the gums, forming a groove for the nipple to settle into. The nipple is drawn in quite far, reaching about mid-tongue level, close to where the hard and soft palate meets, but not completely at the junction. This placement allows for optimal contact and stimulation.

As the infant begins to suck, the lower jaw drops, pulling the anterior portion of the tongue downward. This movement initiates the posterior tongue's wave-like, or peristaltic, motion. The tongue's motion, in combination with the jaw movement, creates a change in pressure that helps draw milk from the breast. When the nipple is in the mouth, the sucking action causes the nipple to lengthen and widen, ensuring a secure grip and proper latch.

The change in pressure as the tongue and jaw move up and down helps drive the milk ejection. As the jaw drops and the anterior tongue lowers, the nipple is supported by the tongue's groove. The subsequent rise of the jaw moves the anterior tongue upward again, initiating another wave-like motion that compresses the nipple and propels the milk further into the mouth, readying it for swallowing.

This coordinated action between the tongue, jaw, and palate stabilizes the nipple and helps milk travel effectively from the nipple through the oral cavity to the pharynx. Each cycle of the jaw-dropping, tongue-lowering, and peristaltic wave moving back contributes to the continuous flow of milk, ensuring the infant receives adequate nutrition with each suck-swallow sequence.

Challenges with Infant Oral Anatomy and Suck/Swallow Patterns

Numerous challenges can arise during breastfeeding due to variations in oral anatomy and suck-swallow patterns, making it essential to be aware of what might impact feeding. While some issues can be addressed through therapeutic interventions, others may require additional medical support. Understanding where occupational therapy practitioners and other healthcare providers can step in is crucial.

One common concern is prematurity. If a baby is born before 28 weeks gestation, they may not have the ability to coordinate sucking and swallowing appropriately. Even babies born between 28 and 32 weeks, though capable of these movements, may have a weak suck-swallow reflex, making it challenging to adequately drain the breast. These infants might not stimulate sufficient milk flow, reducing milk transfer and potential feeding difficulties.

Due to the structural differences in the oral cavity, babies born with cleft palate or cleft lip face significant obstacles to effective breastfeeding. They may struggle to create the necessary seal and pressure for milk extraction. Similarly, infants who fail to thrive often experience various feeding challenges. These babies typically have low birth weight, delayed developmental milestones, and may be irritable or disinterested in feeding. Their low energy and irritability can further hinder their ability to latch and nurse effectively.

Infants with low muscle tone, such as those with Down syndrome, may lack the strength needed to elevate their tongue adequately, which disrupts proper latch and milk transfer. Sensory differences can also interfere with breastfeeding. Babies who are overreactive or underreactive to sensory input may struggle to establish a comfortable feeding rhythm, leading to either aversion or poor sucking patterns.

Tongue tie is another condition that can impact feeding mechanics. When the frenulum under the tongue is too short, it restricts the tongue’s movement, making it difficult for the baby to lift and position the tongue correctly during nursing. This restriction can cause a poor latch and reduced milk transfer.

Laryngeal malacia, a congenital softening of the tissues around the larynx, may cause noisy breathing or a hoarse voice. While it often resolves independently within a few weeks, persistent symptoms might require medical evaluation and intervention to ensure the baby can safely manage milk flow without compromising their airway.

Attachment issues between mother and baby can also affect feeding. Babies who do not form a secure attachment may show disinterest in breastfeeding or struggle to maintain the motivation for consistent nursing. This can be compounded if the mother is experiencing pain or discomfort, such as sore or cracked nipples, which are often caused by an improper latch. The pain can discourage the mother from nursing as frequently, leading to reduced milk production and perpetuating the cycle of poor latch and pain.

Engorged breasts present another challenge. When the breasts are overly full with milk, it can be difficult for the baby to latch properly, making breastfeeding uncomfortable for both mother and baby. Left unaddressed, this can lead to mastitis, an infection caused by clogged milk ducts. Mastitis results in painful, swollen breasts and can severely impact milk production, creating a barrier to successful breastfeeding and potentially requiring antibiotics or other medical interventions.

By recognizing these challenges early and understanding how they impact the breastfeeding process, OTPs and other healthcare providers can guide families through tailored strategies to support both the mother and infant, promoting a positive breastfeeding experience and addressing specific feeding difficulties as they arise.

OTP’s Role in Infant Oral Anatomy and Suck/Swallow Patterns

The occupational therapy practitioner’s role often circles back to the psychosocial aspect of care, which includes providing support and empathy. This means letting mothers know that what they are experiencing, feeling, and doing is normal and acceptable and offering reassurance throughout the process. It’s about being present to validate their feelings and letting them know you are there to listen, understand, and assist as needed.

An ongoing assessment of maternal mental health is crucial when working with mothers of newborns. This continuous monitoring allows practitioners to identify concerns early and provide timely intervention. Additionally, connecting mothers to community resources—whether local or virtual—remains an essential part of the practitioner’s role. Being familiar with the available supports, such as breastfeeding groups, mental health resources, and parenting programs, can make a significant difference for new mothers navigating the complexities of caring for a newborn.

The next three roles will be explored more to highlight specific areas where occupational therapy practitioners can provide targeted support.

Basic Suck Training

Basic suck training involves a series of structured steps designed to help infants develop effective sucking patterns. These techniques can be used by occupational therapy practitioners or taught to parents to support feeding skills. The process begins by gently stroking the cheeks towards the lips using your finger. This brings attention forward and encourages the infant to focus on oral movements. The key is to use a gentle but firm touch, avoiding light strokes, which can be overstimulating.

Next, brush the infant’s lips using the same gentle but firm touch to promote relaxation. Once the infant is comfortable, gently rub the outside and top of the upper and lower gums. This increases oral stimulation and prepares the infant for further input.

Then, insert your finger into the infant’s mouth and nail the side down. Once inside, gently push up and rub at the junction of the hard and soft palate. This specific location is sensitive and helps trigger a sucking response. After applying pressure and rubbing, press downward slightly with the nail portion of your finger. This action should encourage the infant to initiate sucking.

To maintain a consistent suck pattern, repeat the motion: move back up to the junction of the palate, rub gently, and then press down again. This repeated sequence helps establish a rhythm for the infant, reinforcing the motor patterns needed for effective sucking.

In some cases, infants may need extra deep pressure if they have a high tone or are resistant to the movements. Using techniques from neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT), such as providing firm, deep pressure, can help decrease tone and support better control of oral muscles. Integrating these strategies into basic suck training can optimize feeding outcomes and improve oral-motor function for infants who need additional support.

Oral Sensory Training

Oral sensory stimulation involves providing various sensory experiences to increase awareness and responsiveness in the oral area. One simple way to enhance this is by including the infant during mealtimes. Placing them in a comfortable spot, like a bassinet, so they can observe the sights, smell the food, and hear family members talking can help engage their senses and set the stage for oral stimulation. This exposure can also encourage interest in feeding as they associate mealtime with social interaction and sensory experiences.

Encouraging oral exploration is another important aspect. Allowing infants to put their hands in their mouths or providing toys, fingers, or pacifiers to put in their mouths helps them become more aware of different sensations and calms them as they engage in this natural exploration. Increasing oral stimulation can be as simple as offering various textures around the mouth using your hands, a soft washcloth, or different toys.

Another strategy is dipping pacifiers in expressed milk. This adds an extra sensory component, as the infant can taste and smell the milk, making the pacifier more appealing and engaging. Introducing simple teethers is also beneficial. At this stage, the focus isn’t on chewing but on exposing the infant to diverse textures. Some teethers might have bumps on one side and ridges on the other, providing multiple sensory inputs. Offering teethers at different temperatures—such as a frozen teether versus one at room temperature—can also vary the sensory experience.

Positioning for Breastfeeding

Positioning for breastfeeding is important. First and foremost, ensuring the area is free of distractions is essential, which can be challenging, especially for moms with a two-year-old running around. Helping the mother find a comfortable position is key, and ensuring the baby is well-supported is equally important. This process involves trial and error, so trying different positions is recommended. Encourage the mother to explore various positions independently to find what works best for her and the baby.

Cradle Hold. The first position to discuss is the cradle hold in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Cradle hold.

This is the traditional position where the baby is supported with the mother’s arm on the same side as the breast used for nursing. The baby’s body is positioned across the mother’s torso, with their head resting comfortably in the crook of her arm. The mother’s opposite arm can support the baby if needed or for other tasks.

Cross Cradle Hold. Next is the cross-cradle hold in Figure 3, where the mother uses the arm opposite the nursing side to support the baby’s head and back.

Figure 3. Cross cradle hold.

This frees up the arm on the nursing side to support her breast, allowing her to guide the baby’s mouth to the breast more effectively. This position can be particularly helpful for mothers with very large or heavy breasts, as it provides more control and support, making it easier to achieve a proper latch.

Laid-Back Position. The laid-back position can benefit many mothers, especially those feeling exhausted (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Laid-back position.

In this position, the infant is laid on the mother’s chest, allowing gravity to help keep the baby in place without the mother needing to actively hold them. It’s ideal for mothers who may have back or shoulder issues, whether from delivery or preexisting conditions. The mother is in a semi-reclined position, with the baby propped comfortably on her chest, allowing for a more relaxed nursing experience while maintaining a good latch.

Side-Lying Position. The side-lying position, in Figure 5, is another option that allows mothers to relax while nursing.

Figure 5. Side-lying position.

In this position, the mother is lying on her side with her head supported, either on her arm or on a pillow. This setup prevents the breast from weighing down on the baby, which can be particularly helpful for mothers with larger breasts, as it provides some separation between the breast and the infant. The mother’s top arm can support her breast and help guide the baby as needed, making it easier to achieve a comfortable and effective latch.

Football Hold. The football hold (Figure 6) is another nursing position in which the mother holds and nurses the baby on the same side, similar to the cradle hold.

Figure 6. Football hold.

However, instead of the baby being positioned across the mother’s torso, the baby is tucked under the mother’s arm, like holding a football. This positioning allows the baby’s body to be supported along the side of the mother’s body, which can be especially useful for mothers recovering from a C-section or for those who prefer more control over the baby's head during latching.

Football for Twins. This position also allows the mother to have one arm free, providing additional support as needed. It is especially helpful for mothers nursing twins, as they can hold each baby with one arm and nurse them simultaneously. Figure 7 shows this position.

Figure 7. Football hold with twins.

The babies are positioned along her sides rather than in front, giving them each their own space and making it easier to manage feeding without the babies competing for room.

Breastfeeding as an Occupation

The last topic to cover is breastfeeding as an occupation. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months. However, most mothers cannot meet this guideline, and there are countless reasons why. These reasons may include issues with lactation, infant feeding difficulties, lack of support at home, or the need to return to work without access to a suitable pumping environment.

Currently, in the United States, only 25.6% of breastfeeding mothers can continue exclusively breastfeeding for the full six months. This statistic is disheartening, given the recommendations from the WHO and AAP. It highlights the need for greater support systems and resources to help mothers reach their breastfeeding goals through education, workplace accommodations, or community support.

Model of Co-Occupation

Breastfeeding actively involves both the mother and the baby, making it a shared experience rather than something one does to the other. It’s a dynamic process where both respond to each other—the mom adjusting to the baby's cues and the baby responding to the mother's actions. This interactive nature makes breastfeeding a co-occupation because both participants are engaged and actively contributing. Understanding this interplay is essential for recognizing how breastfeeding is more than just feeding; it involves a complex, shared dynamic that affects both the mother and the baby.

There is a significant sharing of the physical aspects of breastfeeding and the emotional and intentional components. It requires both parties to work together harmoniously, highlighting how intertwined their roles are in this activity.

OTPF-4

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) views breastfeeding as more than providing nutrition. It emphasizes the interaction between mother and baby, considering breastfeeding part of a shared caregiving routine, particularly in nighttime care. It’s about creating a sense of comfort and safety for the infant, not just meeting nutritional needs.

What’s particularly interesting is that the OTPF highlights this co-occupation by focusing on the emotional and relational aspects between mother and baby rather than strictly on feeding. This perspective shifts the focus to the interplay between mother and child, reinforcing that breastfeeding is essential to nurturing and bonding, supporting the infant’s overall well-being and security.

Factors Impacting Breastfeeding Duration

Several factors can influence the duration of breastfeeding. Anxiety and maternal stress are significant contributors, as they can negatively impact milk production and add a layer of strain on the mother. This stress can come from balancing the demands of breastfeeding, household responsibilities, or caring for other children. For some mothers, finding the time and mental space to breastfeed consistently becomes overwhelming, making it more difficult to maintain long-term.

Timing is another key factor. When mothers decide to start breastfeeding a few days after birth rather than immediately, they may face additional challenges in establishing a good milk supply and latch, potentially leading to a shorter breastfeeding duration. Belief in the value of breastfeeding also plays a crucial role. Mothers who strongly believe in the benefits and are confident that it will work are more likely to persevere, while those who are unsure or don’t see the value may give up more easily.

Setting realistic expectations is essential. If a mother has very rigid goals, such as exclusively breastfeeding for six months, but faces difficulties with supply or the infant’s nutrition, the frustration and sense of failure may cause her to stop altogether. Flexibility, such as being open to occasional formula supplementation if needed, can help prolong breastfeeding by reducing the pressure and stress on the mother.

Self-efficacy, or a mother’s confidence in her ability to successfully breastfeed, is another critical factor. When mothers feel capable and supported, they are more likely to continue, even through challenging periods. Maternal age also impacts breastfeeding duration, with both very young mothers and those over 35 less likely to breastfeed for a full six months.

Educational level and socioeconomic status are additional influences. Lower educational attainment and socioeconomic status are linked to shorter breastfeeding durations, likely due to a lack of resources, support, and access to lactation education. Racial and cultural factors have also been shown to play a role, with some studies indicating that certain racial groups are less likely to continue breastfeeding. Understanding these factors allows for more tailored support to address each mother's unique challenges.

Facilitating the Co-Occupation of Breastfeeding

As occupational therapy practitioners, we facilitate and support the co-occupation of breastfeeding. We focus not just on the health and well-being of the mother or the baby individually but on the health and well-being of the mother-baby dyad as a unit. The interplay between the two makes this co-occupation so essential, and supporting this relationship is at our core.

OTPs bring a unique perspective to this process by addressing breastfeeding holistically. We aren’t just concerned with the mother’s health, the baby’s health, or the physical aspects of feeding. Instead, we consider the overall wellness, including the social and emotional dimensions. This holistic approach allows us to promote and nurture the dynamic relationship between mother and child, making our support even more meaningful and impactful for both.

Summary

In conclusion, I hope I was able to address the learning outcomes of identifying challenges and potential solutions related to breastfeeding difficulties stemming from the anatomy and physiology of the mother, as well as challenges arising from the infant’s oral anatomy or sucking patterns. Additionally, I aimed to highlight the importance of recognizing breastfeeding as a co-occupation and clarifying occupational therapy practitioners' roles in supporting both the mother and the infant.

Questions and Answers

For women with large breasts, is it recommended that they wear a bra to support milk production, or is it okay for them to go without a bra for greater comfort? Will going without a bra affect milk production?

That’s a great question. Wearing a well-supporting bra is typically more comfortable for women with larger breasts. A supportive bra can help prevent tissue damage, muscle soreness, and overall discomfort. Going without a bra won’t negatively impact milk production, but wearing one can help maintain comfort, indirectly supporting breastfeeding.

Do teas such as fenugreek work to increase milk production?

There are mixed reviews on the effectiveness of fenugreek. Some mothers believe it significantly helps, while others see no difference. It’s one of those remedies that likely won’t hurt to try, but results may vary depending on the individual.

How can mastitis be avoided?

Even when it seems that milk is being drained adequately during feedings, pumping right after nursing is a great strategy to ensure complete milk removal. This practice is especially helpful early on in the breastfeeding process. Pumping after each session can help prevent mastitis by making sure there’s no leftover milk in the breasts, which reduces the risk of clogged ducts. Mastitis can become quite painful, so taking steps to fully empty the breasts is important.

How did you become a breastfeeding specialist?

I pursued certification through lactation consultant educational resources, which involved many hours of coursework focused on breastfeeding. While I could have continued to become a certified lactation consultant, which involves more hands-on training in a hospital setting, I chose to focus on becoming a certified breastfeeding specialist. This certification aligns well with the work I was already doing and supports my ability to assist mothers in a broader, community-based role.

Is it appropriate for occupational therapists to assist with pump fitting and ensuring maximum milk flow?

Absolutely. Occupational therapy practitioners can play a vital role in helping mothers use breast pumps effectively. This includes showing them how to properly fit the pump and ensuring the settings are optimized for comfort and flow. Sometimes, having an external perspective is helpful, as it can be hard for moms to see if things are correctly aligned. Proper pump use and fitting can significantly affect milk production and comfort.

How can the spouse or significant other help the mother during breastfeeding?

This is a crucial aspect that often gets overlooked. Spouses or significant others can play a key role in supporting the mother’s mental health and overall well-being during breastfeeding. Providing emotional support is important, but they can also take on practical tasks, such as cleaning pump parts, managing household responsibilities, or helping with other children. Even if they can’t directly feed the baby, finding ways to be involved and supportive can help them feel connected and included in their development.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Campanella, J. (2024). Introduction to breastfeeding and the role of the occupational therapy practitioner. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5745. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com