Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Joint Attention Based Interventions For Preschoolers With ASD, presented by Aditi Mehra, DHSc, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify basic principles of joint attention and its impact on participation.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify 2 models commonly used to address joint attention.

- After this course, participants will be able to list 6 practical techniques and activities to promote joint attention in various settings, such as home, school, and therapy.

Introduction

Today's topic is interesting because it applies to all of us. Let's see how your joint attention is today and how well I keep your joint attention during this course. This course is specifically regarding preschoolers and ASD, which is the majority of the population I work with.

Joint Attention: Case Study

- Jay- 3 yrs. old, Autism Dx.

- Non-verbal

- Hyporesponsive

- Difficult gaining attention

- Ignores therapist

- Pushes away

- Fixated on lining up things

- Dumping toys

- Disorganized play

- No eye contact

- Self-directed.

- Sensory play: Loves Play-Doh

- “Take what I want and ignore what I don’t want” works for him.

Let's delve into the specifics of our case study, focusing on a three-year-old boy whom we'll refer to as Jay. Jay has been diagnosed with autism, and this diagnosis brings to light several noteworthy aspects of his behavior. Notably, Jay is nonverbal and exhibits a hyporesponsive nervous system, making it challenging to capture his attention effectively. During interactions with his therapist, Jay often displays a tendency to ignore verbal prompts, opting to push away both the therapist and objects presented to him.

Jay's fixation on activities such as lining objects and dumping is a prominent play feature. His play style is characterized by disorganization, presenting a significant challenge for therapeutic engagement. A closer examination reveals a lack of eye contact and a self-directed focus on Jay's attentional patterns. Although he demonstrates attention, it is predominantly self-directed, hindering effective communication and interaction.

Sensory preferences also come into play, with Jay displaying a keen interest in activities involving Play-Doh. This insight into Jay's profile prompts us to consider the symptoms of joint attention that become apparent in such cases. These symptoms include being absorbed in one's own world, internal focus without external awareness, difficulty paying attention to others, and a general lack of interest in the interests of others.

Observations of Jay's behavior highlight tendencies to look away, ignore external cues, and prefer solitary engagement over peer interaction. Notably, his excitement is directed more toward objects than people, emphasizing a key characteristic of his attentional preferences. The absence of shared enjoyment becomes evident as Jay fails to express excitement or share achievements with others, a crucial aspect of social engagement.

Further analysis reveals Jay's limited ability to read social cues, as evidenced by his response to the therapist's color choices. His lack of understanding or acknowledgment of these cues suggests potential play skills and attention challenges, attributing these difficulties to a foundational deficit in joint attention.

In coining Jay's behavior as "take what I want and ignore what I don't want," we recognize a coping mechanism that has seemingly served him for three years. This self-directed approach to attention has shaped Jay's world, posing implications for his overall development.

Jay will remain our focal point in exploring joint attention as we progress through this presentation. The structure will involve an introduction to key definitions and points related to joint attention, a review of relevant literature, and the application of evidence-based strategies to address Jay's case. Keep Jay's profile in mind as we navigate through these crucial aspects of developmental intervention.

What is Joint Attention?

- Any sort of nonverbal communication (e.g., glances, facial expressions, gestures, overstated responses, and voices) used to form a mutual interactive experience and draw another person’s attention is considered joint attention.

- Between 5-8 months of development

- Joint attention is an important multidimensional (sensory, motor, process, social) skill, in terms of both social communication and the development of play behaviors.

(Özkan, et al. 2023; Nystrom et al., 2019)

Joint attention is a concept that encompasses a spectrum of nonverbal communication modalities. It goes beyond mere words and encompasses glances, expressions, gestures, vocal nuances, and any interactive experience that successfully captures another person's attention.

The crucial element in understanding joint attention lies in its ability to draw another person's attention actively. It goes beyond individual attention, marking the foundational basis for effective communication and social skills. This fundamental skill typically takes root between five to eight months of age, representing a pivotal milestone in a child's developmental journey.

Joint attention is not a singular dimension but a multi-faceted skill that engages sensory processes, motor functions, cognitive processing, and social skill development. Its significance reverberates across communication and overall developmental domains, acting as a cornerstone for broader skill acquisition.

To illustrate this concept visually, consider a snapshot featuring two interns actively engaged in showcasing joint attention. At its basic level, joint attention involves the coordination of eye gaze shifting, a fundamental component that sets the stage for more intricate communicative exchanges. As we proceed, bear in mind the profound impact of joint attention on the developmental landscape, recognizing its role as a fundamental building block for effective communication and social interaction.

Alternating one's eye gaze between the person and the object, and may involve gesturing. You can see in Figure 1 that Thea is looking at Elise, who's looking at the ball. She sees Elise looking at the ball, and she's like, "Oh, what's that?" Then, Thea ends up looking at the ball also in the second picture.

Figure 1. An example of joint attention.

This is an example of joint attention. I do want to point out that joint attention is more than just two people looking at the same object. It's like I see Elise looking at the ball, so I look at it too. Elise sees me looking at the ball, so she looks at it longer.

Joint attention involves the acknowledgment between two or more people. It is a mutual act. It's like a nonverbal tap on the shoulder saying, "Hey look here," by using their eyes. It's a form of communication that can be very powerful and important to develop, especially if you have a student who is nonverbal.

Two Main Categories of Joint Attention

- The response, which refers to the infants’ ability to follow other people’s looks and gestures, and as a result, share a common social and visual reference point. Involves processing other people’s signals and understanding intention and social preference

- The spontaneous formation of a shared reference point by observing the infant’s movements, gestures, or gazes between the rest of the people (e.g., starting joint attention). Involves the processes of revealing targeted behaviors

(Özkan et al., 2023)

For joint attention, distinct types come into play. One facet is responding to joint attention, exemplified in the previous slide featuring Thea and Elise. To further illustrate, consider a scenario where a child is engrossed in play at the park, swinging away. Suddenly, an ice cream truck arrives, and though the child might not initially notice it, the excitement of other children draws their attention. Intrigued, the child joins the group to see what has sparked such enthusiasm, subsequently becoming excited themselves. This exemplifies joint attention from a responding standpoint.

Conversely, we encounter initiating joint attention, another form of this complex skill. Picture the same child at the park, this time spotting the approaching ice cream truck. In this instance, the child's gaze shifts to their mother, eyes gleaming with excitement. Through gestures, like jumping around, the child effectively communicates their enthusiasm about the ice cream truck to their mother, showcasing initiating joint attention. These examples underscore the dynamic nature of joint attention, both in responding to external cues and proactively initiating shared focus.

Development of Joint Attention

- Responding to another person’s directive attention – develops at the end of 1st year

- At 12-14 months, infants begin to “check back” and look at the person after first looking at the object.

2. Initiating the attention of another person to the object or event.

- The gaze shifts between the object and a familiar person.

- Adults usually respond by labeling objects or events.

Later, combined with gestures, verbalizations, pointing, reaching, and showing

By the middle of the 2nd year, joint attention is well-developed.

(Jones & Carr 2004)

This study focused on the development of joint attention in infants, a noteworthy inclusion in our discussion. While the article specifically addresses infants, the fundamental principles align with the concepts of responding and initiating joint attention.

The developmental trajectory of joint attention is a gradual process, initiating around five to eight months but gaining momentum toward the end of the first year. By approximately 12 to 14 months, infants exhibit the ability to respond to another person's directive attention. This involves checking back with a caregiver after initially focusing on an object, seeking reassurance or approval, a behavior indicative of the child's growing understanding of their social environment.

Initiating joint attention follows, marked by the child shifting their gaze between an object and a familiar person. The adult's role in this interaction is pivotal, as they typically respond by labeling, and offering verbal reinforcement such as, "Oh yes, that's a ball." This social reinforcement plays a crucial role in reinforcing the child's engagement with both the object and the person, contributing to the development of joint attention.

Consider the impact of early social experiences, as illustrated by a child who may have spent their formative years in an orphanage. If a child lacks the social reinforcement of having their observations acknowledged and validated by adults, it could potentially impede the development of joint attention.

As development progresses, combined gestures with verbalization, including pointing, reaching, and showing, come into play. By the middle of the second year, joint attention reaches a well-developed stage, showcasing the intricate interplay between nonverbal cues, verbal reinforcement, and the evolving social dynamics in a child's developmental journey.

Joint Attention Impacts Social Skill Development

- A decrease in social stimulation that is due to the lack of social orientation(the ability to independently perceive and notice social stimuli, including characters, faces, eyes, and body postures) (Özkan et al., 2023).

- Neurocognitive research suggests that social-communication and language processes are two different, yet interacting systems (Nowell et al., 2020).

Joint attention impacts social skill development due to a lack of social orientation.

The ability to independently perceive, notice, and filter stimuli to focus on individuals and obtain feedback is a crucial aspect of cognitive development. Neurocognitive research delves into the intricate relationship between social communication and language processes, highlighting their symbiotic interaction. A notable study conducted by Moberg in 2017 sheds light on the impact of joint attention on the social communication skills of internationally adopted children.

This study addresses a cultural dimension, recognizing that environmental and cultural factors may significantly influence developmental experiences. While Western societies often provide ample stimulation to children in their early years, this may not be universally true, especially in countries where institutionalization, such as orphanages, limits exposure to such stimuli.

The research focused on internationally adopted children who had experienced early adversity before being adopted into the United States. The pivotal question was whether exposure to the rich environment of joint attention and stimulation in the U.S. would bring about changes in their developmental domains. Six months later, an assessment was conducted to evaluate the children's social, communicative, and cognitive domains.

The results were illuminating, indicating that interventions targeting joint attention proved to be effective in supporting children who had faced early adversities. This underscores the significance of not overlooking the impact of joint attention in developmental contexts, particularly for children with challenging early experiences. Early intervention emerges as a key player in addressing and mitigating the negative impacts of early adversities, emphasizing the proactive role of caregivers, educators, and professionals in fostering healthy developmental trajectories for children.

Joint Attention and Autism

- One of the DSM-IV criteria for autism:

- “A lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people (e.g., by a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest)”

In the context of autism, joint attention stands out as a key criterion in the DSM. A comparison between typically developing children and those with autism reveals notable deficits in eye gaze shifting, gestural joint attention, and responsiveness to bids of joint attention - both in initiation and response. These deficits represent some of the earliest signs of autism, as indicated by the literature.

However, the challenge extends beyond the immediate impact on joint attention skills. There is an associated opportunity cost - limitations in joint attention skills restrict language-promoting interactions, subsequently diminishing opportunities for shared collaborative experiences. To illustrate this point, consider an outdoor scenario where a typical child observes a flying bird. The caregiver might exclaim, "Oh, look at that bird!" The child, in turn, gazes in the direction indicated, possibly pointing and engaging in a dialogue about the bird's features or colors. This exchange not only fosters language development but also expands the child's vocabulary through shared experiences.

In contrast, a child with autism displaying joint attention deficits may not respond to the caregiver's remark about the bird. This missed opportunity for engagement disrupts the natural flow of conversation and hinders the building of vocabulary and language skills. Over time, this cumulative loss of engagement opportunities can have exponential and deleterious effects on the child's overall development.

The example highlights the intricate interplay between joint attention deficits and language development, emphasizing the far-reaching consequences of such challenges. While joint attention deficits are a key aspect of autism, it's acknowledged that they may not be the sole contributing factor. Speculation exists regarding other potential reasons, underscoring the complexity of understanding and addressing the multifaceted nature of autism spectrum disorders.

What Does the Literature Say?

- Expressing surprise in actual settings can encourage joint attention behaviors.

- Practicing synchronized staring and pointing may help them to become better at responding to joint attention bids.

- Procedures consisting of direction & reinforcement are effective in teaching demanding and joint attention skills.

- Simplified social environments and joint attention demand positively affect performance in children with ASD.

(Ambrose et al., 2020)

In the literature, it becomes evident that joint attention holds a pivotal role in language development and social play. As we examine the evidence-based strategies outlined in the research, we find that interventions targeting joint attention yield favorable outcomes. These interventions are associated with increased social interaction, positive affect, and spontaneous speech.

Expressing surprise emerges as a particularly effective strategy, tapping into the sensory affect and creating a distinct stimulus for joint attention. Additionally, synchronized staring and pointing practices are highlighted as valuable methods, especially in fostering responding joint attention. Procedures involving clear direction and reinforcement play a crucial role. For instance, reinforcing a child's pointing behavior is essential for the continuity of joint attention.

Simplifying social environments is underscored as a key consideration, particularly when working with children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The sensory perspective is crucial to comprehend – an overwhelming array of visual stimuli may hinder a child's ability to engage in joint attention. By creating an environment that minimizes sensory overload, practitioners can enhance the child's capacity for joint attention and facilitate more effective interventions.

The literature, therefore, provides a comprehensive guide to evidence-based strategies, offering insights into practical approaches for implementing interventions. As we explore these strategies in the case study involving Jay, the goal is to bridge the gap between research findings and real-world application, evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions in a practical setting.

There is More

- Children with ASD have deficiencies in detecting movements during low-level visual stimulation, emotional processing, and facial expressions, even at very young ages.

- Studies have indicated that environmental changes (e.g., space, sensory aspects, lighting [daylight vs. artificial], furniture, fixtures, and materials) result in better participation among children with ASD.

(Özkan et al, 2023)

Children diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) often face challenges in detecting low-level visual stimulation, processing emotions, and interpreting expressions. To address these difficulties, amplifying facial expressions and emotions is imperative, providing exaggerated visual cues that enhance comprehension.

A notable strategy employed in this context is video modeling. This involves parents actively engaging in exaggerated expressions of emotions ranging from happiness to sadness. By leveraging visual learning through this approach, children with ASD can more effectively grasp and interpret emotional cues.

Studies also highlight the significant impact of environmental factors on a child's participation and engagement. Alterations in sensory elements, such as adjusting lighting and managing noise levels, play a crucial role in creating a conducive environment. Understanding the child's sensory profile is essential to tailor the surroundings to accommodate their specific sensory needs.

Joint Attention: A Multidisciplinary Approach

- SLP

- ABA

- OT

The literature underscores the effectiveness of adopting a multisensory and multidisciplinary approach when addressing joint attention. This approach is particularly crucial given that various professionals work on joint attention in different ways, tailoring interventions to their specific goals and areas of expertise.

Occupational therapists, for instance, find joint attention particularly relevant as it intersects with school goals related to learning, writing, and life skills. If a child struggles with joint attention, it can impact various occupational therapy interventions, such as holding a pencil and imitating strokes. Similarly, speech therapists and Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) professionals also address attention concerns in the context of learning, behavior, and life skills.

Emphasizing the importance of a multidisciplinary approach, collaboration among therapists becomes key. Co-treatment, where therapists collaborate during one-on-one sessions, offers a holistic perspective on how therapeutic interventions impact joint attention. This collaborative effort provides valuable insights into the multifaceted nature of joint attention and enhances the overall efficacy of interventions.

It's crucial to note that joint attention concerns are not exclusive to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). They can be a subset of general attention problems, executive functioning issues, or processing speed challenges. Motor planning and processing difficulties can also contribute to joint attention deficits. Additionally, trauma may impact joint attention due to heightened stress responses leading to withdrawal or shutdown. Cultural elements, such as variations in the encouragement of eye contact, also play a role and require careful consideration.

The presentation will further explore evidence-based approaches within these domains, offering practitioners a comprehensive understanding to inform their practice and tailor interventions based on individualized needs and contexts.

An OT Perspective

- An RCT to examine the effects of this training on children’s social communication, ASD-related behaviors, and visual perception skills.

- Twenty children (4 to 6-year-olds with a dx. of ASD) participated in this study.

(Özkan et al., 2023)

From the occupational therapy perspective, it's imperative to acknowledge the sensory element that inherently characterizes this domain. A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) study, selected for its high-level design, provides valuable insights into the impact of training on children's social communication, ASD-related behaviors, and visual perceptual skills.

This rigorous study enlisted 20 children aged four to six, all diagnosed with ASD. The research employed comprehensive measurement tools, including the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), the Autism Behavior Checklist, and the Motor-Free Visual Perceptual Test (MVPT), to assess outcomes.

The multifaceted approach of the study encompasses various facets of occupational therapy interventions. By utilizing these standardized measures, the study aimed to discern the effectiveness of the interventions in addressing the specific challenges faced by children with ASD. This research is a promising example of evidence-based practices within the occupational therapy realm, shedding light on the potential impact of targeted interventions on social communication and perceptual skills in this population.

- 1st Approach:

- (1) Creating a response to a joint attention offer, (2) Initiating joint attention, and (3) Reinforcing a joint attention response

- Less-to-more orientation to get the child to respond to the offer of joint attention

- For example, if the child did not respond to the joint attention offer within 5 to 10 sec, the therapist first directed the child, using exaggerated gestures, to move toward the targeted toy

The first approach in this occupational therapy study focused on cultivating a response to joint attention and initiating joint attention while ensuring reinforcement. Employing a "less to more" contingency in their orientation strategy, the therapists implemented a structured approach. If a child failed to respond to joint attention cues within the initial five to 10 seconds, therapists initiated direction using exaggerated gestures. This technique aligns with the literature emphasizing the efficacy of exaggerated gestures in facilitating joint attention. The goal was to guide the child toward the targeted toy, employing a systematic and responsive methodology to enhance the child's engagement in joint attention activities.

- 2nd Approach:

- The Dynamic Model for Play Choice: the formation of play preferences is the outcome of a nonlinear process, and the choice of play activity is dynamic in character

- The choice of this amusingly and repetitive play pattern by the child and the therapist, with the therapist making funny sounds and gestures, helps in the development of emotional meaning

In the second approach, the occupational therapy intervention is more dynamic. The play activity is characterized by its dynamic and interactive elements, incorporating choices to enhance engagement. This approach fosters a playful and enjoyable scenario, marked by repetition and patterns jointly created by the child and therapist. Therapists introduce funny sounds and gestures within this dynamic context, injecting emotional meaning into the activity. The incorporation of humor and emotional elements serves the dual purpose of making the activity more enjoyable for the child and further facilitating joint attention.

- 3rd Approach:

- Fine motor activities, such as handicrafts and finger games; gross motor activities, such as obstacle courses, music, and dance; and visual–motor activities, such as drawing, cutting, and assembly, were used

- The focus of the intervention was initiating and responding to joint attention during these activities

The third approach in this occupational therapy intervention involves incorporating crafts—a realm where occupational therapists often shine. Through activities such as finger games, gross motor activities, obstacle courses, cutting, drawing, and more, the therapist aims to engage the child in a creative and interactive manner. The focus remains on both initiating and responding to joint attention.

Utilizing craft materials like pompoms, therapists encourage the child to actively participate in tasks, whether it's popping a pompom to a specific location or using glue for a collaborative project. The hands-on nature of crafts enhances fine motor skills and serves as a platform for fostering joint attention.

- 4th Approach:

- Compatible environmental arrangements that provide visual cues are important when structuring environmental activities

- Pictorial directions, photographic activity charts, checklists, video-recorded modeling, activity sequences, and color coding, as well as changes to the sensory properties of the environment and materials used in a task

The fourth approach within this occupational therapy intervention revolves around environmental arrangements. This strategy entails the strategic use of visual cues to structure activities within the environment effectively. This approach is particularly valuable when implementing activities such as obstacle courses or exploring various environmental elements.

Various tools and aids were employed in this approach, including pictorial directions, photographs, activity charts, checklists, video-recorded modeling—a noteworthy inclusion—activity sequences, color coding, and adjustments to sensory properties within the environment. The emphasis on visual cues and environmental structuring aligns with the goal of creating a supportive and organized context for the child.

Results:

- Significantly higher scores for initiating attention, initiating object demands, and responding to social interaction

- Maintained coordination for significantly longer periods and improved their developmental skills

- Improved visual perception in children with ASD

The results of the occupational therapy intervention demonstrated significantly higher scores in initiating attention, initiating object demands, and responding to social interaction. The intervention also maintained coordination for a longer period, indicating improved developmental skills with positive generalization. Additionally, there were observed improvements in visual perceptual skills among children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

What Does Sensory Have to Do With Joint Attention?

- Interacting & forming the foundation for multiple higher-level social, language, and cognitive abilities.

- Sensory perceptual /motor skills are integral to forming knowledge of “self,” and visual and attention skills form knowledge of “other.”

- Integration allows a child to engage in parallel processing of their own attention with the attention of others.

- Both hyporesponsive and sensory-seeking behaviors are significantly associated with slower attention, disengagement, and decreased orienting in children with ASD.

(Nowell et al., 2020)

Understanding the connection between sensory processing and joint attention is pivotal. Imagine being in a bustling environment with vibrant lights, music, and an array of stimuli - it becomes challenging to focus on specific details or conversations amidst the sensory overload. This scenario illustrates the role of the sensory system in joint attention - it acts as a filter, allowing individuals to concentrate on essential information while disregarding extraneous stimuli.

Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) may possess the ability to filter some information, but their attention tends to be isolated, forming a "bubble." This isolated attention hinders the development of foundational skills such as language, social interaction, and joint attention. Additionally, joint attention contributes to a heightened sensory awareness of oneself and others, distinguishing between personal and external stimuli.

Furthermore, the integration of sensory information enables parallel processing - an intricate task involving simultaneous consideration of one's sensory experiences and those of others. This dual processing is intricate and can be challenging for individuals with ASD, impacting their ability to effectively engage in joint attention and navigate the complex sensory landscape of social interactions.

Children with hyporesponsive behaviors may be less sensitive to novel stimuli, impacting their attention's speed and frequency.

Disengagement: Child may be so intensely engaged with a nonsocial aspect of their environment that they struggle to disengage with it and orient their attention to other stimuli.

(Nowell et al., 2020)

Research indicates a significant association between hyperresponsive (underresponsive) and sensory-seeking behaviors and slower attention, disengagement, and decreased orienting in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Additionally, these children tend to be less sensitive to novel stimuli. This is evident in situations where, for example, a fire truck outside the window may go unnoticed by a child with ASD, while their siblings react promptly.

The challenge lies in the difficulty these children face in disengaging from their current focus to attend to something new. Parents often share instances where their child is deeply engrossed in preferred activities like puzzles or hyperlexia (a fascination with letters and numbers). While these activities may provide windows of joint attention if aligned with the child's interests, introducing external demands can disrupt their sensory system.

Parents may observe that when a child is engrossed in preferred activities, their sensory system is calm. Attempts to redirect attention or introduce alternative stimuli can momentarily trigger a fight-or-flight response, leading to resistance and a preference to stick with the familiar. It becomes crucial for parents to understand these sensory dynamics, recognizing that the child's strong focus on specific activities may be a way of maintaining sensory equilibrium. The sensory perspective sheds light on the challenges children with ASD face in navigating joint attention, emphasizing the need for tailored interventions that consider and accommodate their sensory sensitivities.

Speech Language Perspective

- How are joint attention and sensory-regulatory features related in early childhood and predict language and social-communication outcomes in preschool?

- Cross-lagged panel analysis models were used to examine the association between joint attention and sensory-regulatory features at 13 and 22 months of age in children (n = 87)

(Özkan et al., 2023)

Shifting to the speech-language perspective, a recent study investigates the sensory regulatory features in early childhood to predict language and social communication outcomes in preschool-aged children. The study particularly focuses on investigating the association between joint attention and sensory regulation in children aged 13 to 22 months. This research aims to unravel the intricate links between sensory processing, joint attention development, and subsequent language and social communication outcomes during the preschool years.

Study: Nowell et al., 2020

The goal was to examine the following research questions:

- What are the concurrent and predictive correlations between JA and sensory-regulatory features at 13 and 22 months of age in a community sample of children identified at 12 months as at a higher likelihood for ASD?

- To what extent do JA and sensory-regulatory features at 13 and 22 months of age predict general preschool language outcomes in a community sample of children identified at 12 months as at a higher likelihood for ASD?

- To what extent do JA and sensory-regulatory features in children at risk for ASD at 13 and 22 months of age predict aspects of preschool social-communication competence, including narrative retelling, in a community sample of children identified at 12 months as at a higher likelihood for ASD?

The primary focus was examining the correlations between joint attention and sensory regulation. Additionally, the research aimed to explore the extent to which the combination of joint attention and sensory regulation could predict language outcomes in preschool. Furthermore, the study delved into the aspects of preschool social communication competence that could be predicted by the interplay between joint attention and sensory regulation. These research inquiries formed the basis for a thorough investigation into the intricate connections and predictive capacities of joint attention and sensory regulation in the context of language and social communication outcomes for preschool-aged children.

- Results

- It supported the hypothesis that JA and SR were related in early childhood predictive relationships.

- Elevated sensory-seeking behaviors at the end of the second year of life significantly predicted later social-communication symptoms.

- Sensory behaviors at the end of the second year are predictive of preschool receptive language skills.

- Both joint attention and sensory regulation are important factors in the first and second years of life for impacting later preschool language and social communication.

The study yielded intriguing results, revealing a predictive relationship between joint attention and sensory regulation. Elevated sensory-seeking behaviors observed at the conclusion of the second year of life emerged as a significant predictor of subsequent social communication problems. Furthermore, sensory behaviors observed at the end of the second year were identified as predictors of preschool receptive language skills.

A Behavioral Perspective

- Evaluation of whether multiple-exemplar training, auditory scripts, and script-fading procedures could establish a generalized repertoire of initiating bids for joint attention in four, young children with autism.

This study evaluated whether multiple exemplar training, using auditory scripts and script-fading procedures, could establish a generalized repertoire for initiating bids for joint attention.

Gomes Study

- The function of joint attention is social and impacts an individual’s engagement within his or her environment and motivation to interact with a familiar person.

- This makes joint attention more than alleviation of fear or escape. For example, the presence of novel stimuli in the environment may function as negative reinforcers for joint attention.

- Joint attention may be conceptualized as a response class that includes orienting, pointing, and vocally commenting maintained by either positive or negative and socially mediated reinforcement.

In this study involving four young children with autism, the focus was on the function of joint attention within the framework of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). A key aspect of ABA is identifying the function of a behavior, and in the context of joint attention, its function is recognized as both social and involving individual engagement with the environment. This engagement influences the person's motivation to interact with others, ideally someone familiar with the environment.

While the study primarily approached joint attention from a behavioral standpoint, it acknowledged that joint attention is a multifaceted phenomenon. Joint attention encompasses a broader range of functions beyond serving as a mechanism to alleviate fear or escape from attending to others or responding to novel and potentially negative stimuli in the environment. It was emphasized that joint attention can be conceptualized as a response class, involving orienting, pointing, and vocally commenting. These behaviors are maintained by a spectrum of positive, negative, or socially mediated reinforcement.

- Goal: To teach children with autism to initiate bids for joint attention

- (a) in the presence of stimuli representing a greater sample of those occurring naturalistically (e.g., both visual and auditory stimuli)

- (b) that generalize from teaching to nonteaching stimuli and conditions

- (c) using stimuli not necessarily preferred by participants

- (d) that incorporate vocal responses taught using auditory scripts

- (e) using a variety of vocal responses by programming for response generalization using three scripts per target stimulus

- (f) that emitted as a function of socially mediated consequences

In pursuit of the goal of helping children initiate bids for joint attention, the study implemented several key strategies. The approach involved exposing children to diverse stimuli, encompassing visual and auditory elements beyond typical naturalistic occurrences. Generalization of the learned skill was emphasized, extending from teaching stimuli and conditions to non-teaching counterparts. The inclusion of non-preferred stimuli aimed to enhance the versatility of the acquired skill across various situations.

Vocal responses were introduced through auditory scripts, offering a streamlined and structured communication approach. The study incorporated a variety of vocal responses to promote generalization, employing three scripts per target stimulus. Socially mediated consequences played a crucial role, with ample social reinforcement to support and encourage the children to effectively perform the task.

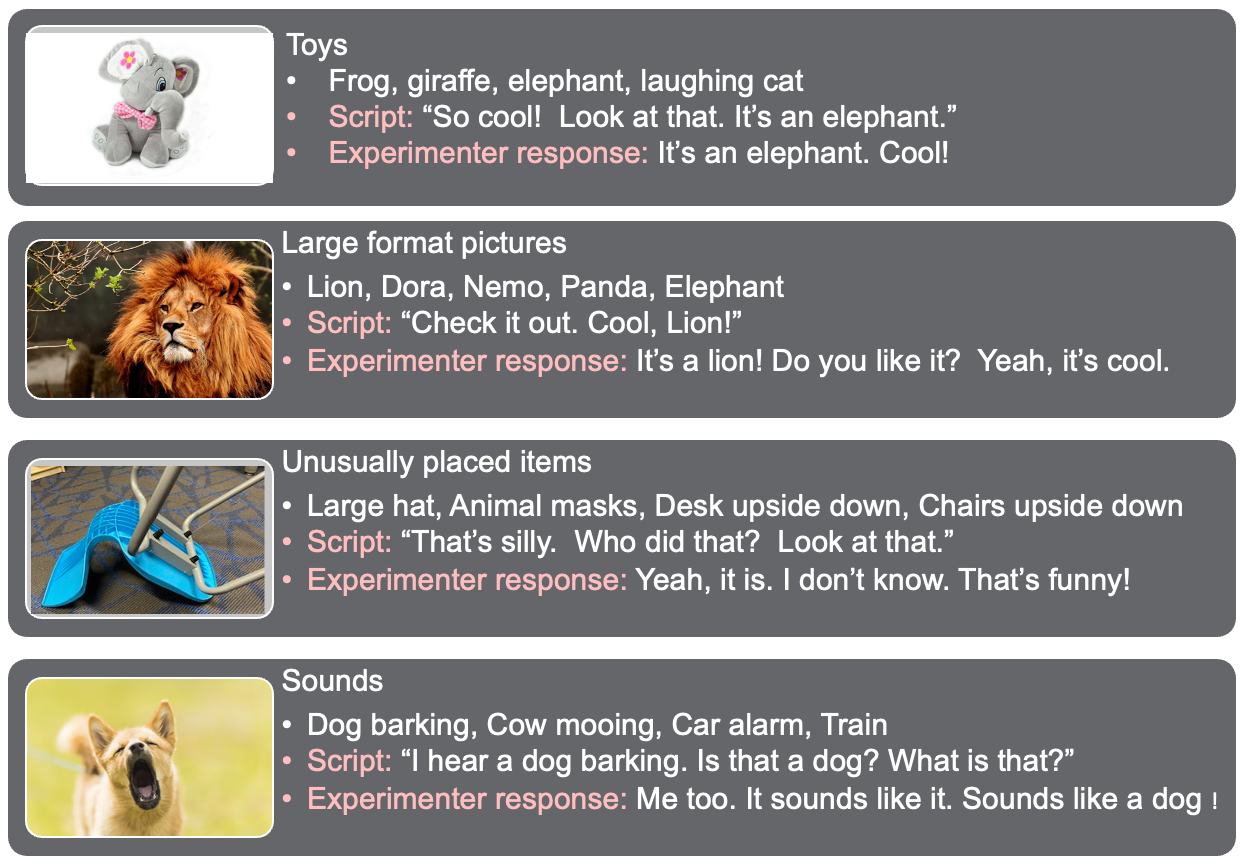

- The four categories were

- (a) visually enticing toys

- (b) unusually placed items

- (c) environmental sounds

- (d) pictures

There are four categories shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Four categories of joint attention initiation (Click here to enlarge the image).

The study employed various stimuli and scripts to facilitate joint attention initiation. Different categories, such as visually enticing toys, placement of toys in unusual spots, environmental scents, pictures, unusual items, and sounds, were utilized with corresponding scripts. These scripts maintained consistency across different items to observe the child's responses.

For instance, with visually enticing toys like a frog or giraffe, the script involved expressing excitement about the toy's identity, followed by a positive acknowledgment. Similarly, large-format pictures, unusually placed items, and sounds were incorporated with consistent scripts to create a structured approach.

- Results

- Young children with autism acquired a generalized repertoire of initiating bids for joint attention across of variety of stimuli and settings. With the introduction of the intervention, participants’ bids for joint attention systematically increased.

- Socially mediated consequences (e.g., smiles, comments made by the experimenter); Required tangible reinforcers (e.g., snacks) to initiate bids for joint attention.

- Multiple-exemplar training was effective in increasing generalized responses across untrained stimuli.

The results of the study demonstrated significant positive outcomes. Young children with autism develop a generalized repertoire for initiating bids for joint attention across various stimuli and settings. The intervention led to a systematic increase in participants' bids for joint attention, showcasing not only generalization but also a consistent improvement in initiating joint attention.

Socially mediated consequences, such as smiles, comments, and high-fives, along with tangible reinforcers like snacks and stickers, were effectively utilized to encourage and reinforce joint attention behaviors. The study highlighted the success of multiple exemplar training, emphasizing a multi-sensory or multi-dimensional approach, in enhancing generalized responding across untrained stimuli.

It's worth noting that the study's distinctive feature was scripted communication, a method that may be particularly relevant to speech therapy. Collaborating with speech therapists can offer valuable insights into the language development stage of the child and determine the most appropriate strategies for intervention.

Models for Joint Attention: Early Start Denver Model (ESDM)

- Based on ABA and developmental psychology, ESDM is a comprehensive early intervention model.

- Use with children aged 18–48 months.

- Features a manualized curriculum divided into four levels each of which targets different developmental areas.

- It uses natural environments and positive relationships to promote children’s learning outcomes.

- ESDM acknowledges that parents are best placed to implement early interventions in the home setting.

- It is grounded in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory.

There are two models with robust research backing their efficacy.

The first model is the Early Start Denver Model, which integrates principles from Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) and developmental psychology. This model is designed for children aged 18 to 48 months, offering a curriculum with four levels. Notably, it emphasizes utilizing natural settings and fostering positive relationships to facilitate children's learning.

What sets this model apart is its focus on involving parents actively. Recognizing that therapy gains must extend to the home environment, the Early Start Denver Model places parents in a crucial role. The model is rooted in Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theories, illustrating how various factors within their world and community influence a child's development. This holistic approach acknowledges the interconnectedness of a child's experiences and the broader environment.

ESDM: Parent Training In…

- Gaining the child’s attention

- Motivating them

- Promoting dyadic engagement

- Joint activity routines

- Enhancing verbal

- Nonverbal communication

- Incorporating play skills

- 26-week period

(Jhuo et al, 2022)

The Denver Model focuses on several key components to support a child's development. It prioritizes capturing the child's attention, fostering motivation, and encouraging didactic engagement between the parent and the child. Notably, it strongly emphasizes joint activity routines, recognizing the significance of structured routines in early intervention. The model also aims to enhance verbal and non-verbal communication skills, integrating play skills into the developmental process. Typically implemented over a 26-week period, this model provides a comprehensive and structured approach to early intervention.

Outcomes of the ESDM Model

- Parents of children with ASD consistently reported lower levels of parenting-related anxiety, stress, or depression.

- It is implemented by parents to maximize learning opportunities in daily activities and bridge service gaps.

- Several studies have revealed that

- (a) Parents can learn to implement the intervention techniques with fidelity

- (b) Doing so results in a range of improvements in child outcomes

(Jhuo et al, 2022)

The Denver Model's positive outcomes extend beyond the child, impacting parents by reducing parenting-related anxiety, stress, and depression. This holistic approach recognizes the interconnectedness of child development and parental well-being. The model's efficacy is demonstrated in maximizing learning opportunities and effectively bridging developmental gaps. Moreover, empowering parents to implement intervention strategies with fidelity contributes to improved outcomes for the child. The versatility of professionals, including psychologists, ABA therapists, OTs, speech therapists, and EI therapists, in delivering this model highlights its accessibility and widespread applicability.

Models for JA: Relationship Development Intervention® (RDI) model

- The Relationship Development Intervention® (RDI)

- Program is a comprehensive, parent-directed intervention designed to facilitate the social, emotional, and cognitive development of children, adolescents, and adults with (ASD).

- It promotes the development of dynamic intelligence through the restoration of a guided participation relationship (GPR) between the parent and the individual with ASD.

(Gutstein 2009)

The Relationship Development Intervention model (RDI) stands out as a comprehensive, parent-directed approach to enhancing joint attention. Distinguished by its emphasis on dynamic intelligence, RDI underscores the importance of fostering adaptability for individuals with autism. This model revolves around understanding diverse perspectives, navigating change effectively, and integrating sensory inputs. The core focus lies in building flexibility, a vital skill that contributes significantly to the quality of life for children and individuals on the autism spectrum.

RDI Theory

- Research suggests that there is indeed evidence of neural underconnectivity in the brains of individuals with ASD.

- It theorizes that a disruption of the guided participation relationship between parents and their children with ASD impedes the development of dynamic neural pathways while leaving static pathways generally intact.

(Gutstein, 2009)

The research underscores the concept of underconnectivity in the brains of individuals with ASD. Strategies promoting flexibility in diverse approaches are highlighted as contributors to enhanced neuroplasticity and connectivity. The model also theorizes that a disruption in the guided participation relationship between parents and children with ASD can hinder development. Therefore, implementing the model as suggested and emphasizing guided participation becomes crucial in optimizing outcomes.

RDI Goals

- Collaboration

- Deliberation

- Flexibility

- Fluency

- Friendship

- Initiative

- Responsibility

- Self-management

(Gutstein, 2009)

The goals are collaboration, deliberation, flexibility, fluency, friendship, initiative, responsibility, and self-management. You can see it's a very different model than the Denver.

RDI Stages

- Readiness Stage

- Apprenticeship Stage

- Guiding Stage

- Internalizing Stage

(Gutstein, 2009)

The stages are readiness, apprenticeship, guiding, and internalizing. A lot goes into these stages, but this is just a general overview.

RDI Outcomes

- RDI helps autistic children reach their potential.

- Parents learn to embrace parenthood.

- Consultants form a team with parents.

Overall, RDI was perceived to be beneficial in improving autistic children’s social engagement, such as parent-child interactions, as well as enhancing parenting experiences.

(McAuliffe et al., 2023)

The Relationship Development Intervention model outcomes indicate significant support for children in reaching their potential. The recent article emphasizes how it facilitates parents in embracing parenthood. With the ongoing support of a consultant guiding a team of parents, the model proves to be beneficial in fostering positive outcomes.

Back to Our Case Study: JA Strategies

Returning to our case study with Jay, a three-year-old diagnosed with autism, let's consider where to begin. Reviewing the literature, these are evidence-based and effective strategies to address the observed behaviors in the assessment.

- Dynamic social expressions and exaggerated mimicry with coordinated pointing

- Establishing the presence of adults as generalized reinforcers

The initial strategy involved incorporating dynamic social expressions, exaggerated mimicry, and coordinated pointing. This approach is utilizing activities like peekaboo, although his hyporesponsiveness resulted in a more subdued reaction than previous students.

Figure 3. The author playing peek-a-boo with a client.

After introducing dynamic social expressions and coordinated pointing, I could incorporate a visual element, such as a spinning or lighting-up object, to enhance Jay's engagement during peekaboo. The focus is on building rapport rather than immediate joint attention. I aimed to establish myself as a generalized reinforcer, ensuring Jay associated our interactions with positive experiences. This approach aimed to reduce potential stress or anxiety associated with encountering a new person, laying the groundwork for future joint attention efforts. The initial sessions focused on creating a positive connection and reinforcing that good things happen when he is with me. This step was crucial in minimizing cortisol spikes and establishing trust with Jay.

- Use items that are preferred and engaging (e.g., toys that move, light up, and have textures, and letters)

- Use a variety of items and incorporate novelty (repetitive put in)

He loved letters and numbers, so Figure 4 shows an activity I used.

Figure 4. Letter activity.

I introduced a simple and preferred activity for Jay using a textured object. Initially, the goal was to engage him in stress-free play without demands or expectations of joint attention. The chosen activity provided repetition and texture, contributing to Jay's calming and regulated sensory experience. The focus at this stage was on creating a positive and enjoyable interaction, fostering a sense of safety and non-threat. The activity involved a familiar and novel element, allowing Jay to engage comfortably while supporting motor skills and coordination. This approach aimed to lay the foundation for future joint attention efforts.

- Introducing silly, out-of-place events/objects

- Out-of-place items to evoke a response

- Putting high-preference items and faces in the line of vision to evoke gaze responses

Elise, a speech pathology intern, was working with me. She used an out-of-place item to evoke a response in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Elise using an out-of-place item.

Collaborating with Elise, we incorporated Jay's interest in dinosaurs into the activity. Placing the toy on Elise's head sparked Jay's curiosity, creating an opportunity for joint attention. A scripted phrase like, "Isn't that silly?" provided a structured interaction. Over time, Jay began spontaneously using the phrase, showcasing a progression in language. The involvement of a speech therapist, Elise, was valuable in refining language strategies, such as transitioning from "silly" to "funny." Tailoring the activity to Jay's high-preference item ensured his engagement and participation in the joint attention process.

- Deliver enthusiastic, high-energy attention (e.g., loud “wow,” funny face, high-volume tickles)

- Combine easy tasks with difficult tasks

- Object at their eye level

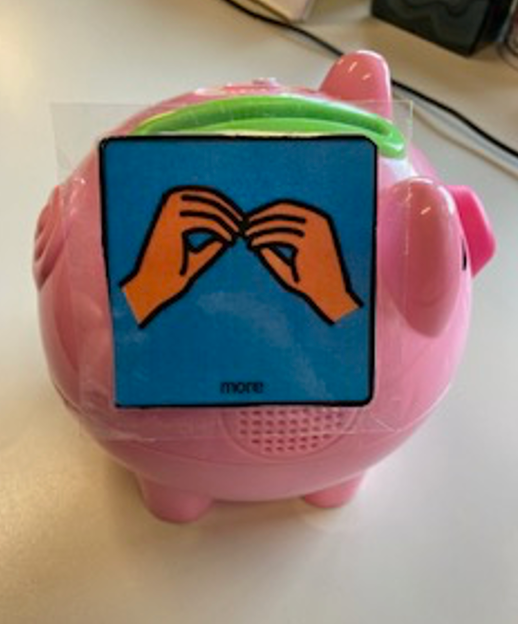

Celebrating joint attention achievements with enthusiastic reinforcement, such as funny faces, high fives, and tickles, creates a positive and rewarding environment. The collaboration between Elise and myself contributed to the child's success. Integrating easy tasks, like placing coins into the container, with more challenging activities, such as using picture cards, as shown in Figure 6, encourages gradual progression in joint attention skills. Tailoring the tasks to Jay's preferences ensures continued engagement and reinforces positive associations with joint attention experiences.

Figure 6. Example of using picture cards with activities.

Adjusting the placement of the PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System) card to align with Jay's visual attention and incorporating a playful element with the pig created a scenario where he needed to interact with the card. This intentional setup encouraged Jay to remove the card, fostering a bid for joint attention. The collaboration between guiding Jay and Elise's positive reinforcement allowed for successfully initiating joint attention using PECS cards. This strategy acknowledges the child's current attention patterns and gradually introduces new elements to expand joint attention capabilities.

- Call the child’s name. Pick up the item he is playing with, put it in front of his face, then lead it to your face.

- Place the PECS card next to the item.

Bringing the item to your face is another strategy, as shown in Figure 7. If you're using PECS cards, you can also bring those to your face.

Figure 7. Elise demonstrated bringing an item to her face.

Another option is taking the child's hands and putting them on your face, if not aversive to touch. You never want to force this scenario.

- Call the child’s name. Take the child’s hands and touch them to your face.

- Call the child’s name. Make a stimulating noise (finger snap, clap, etc.). When the child turns to the noise, catch his gaze and reinforce.

One little girl I treated liked the vibration whenever I sang. She would put her hands on my face (Figure 8). She would look at me when I would sing, but when I'd stop singing, she'd look away. I would wait for her to look at me, and then sing again. I am using her sensory preferences to facilitate joint attention, but I'm also giving her reinforcement. When she looked at me, she would get the song and feel the sensory vibration she enjoyed.

Figure 8. The child touches the author's face to feel the vibration.

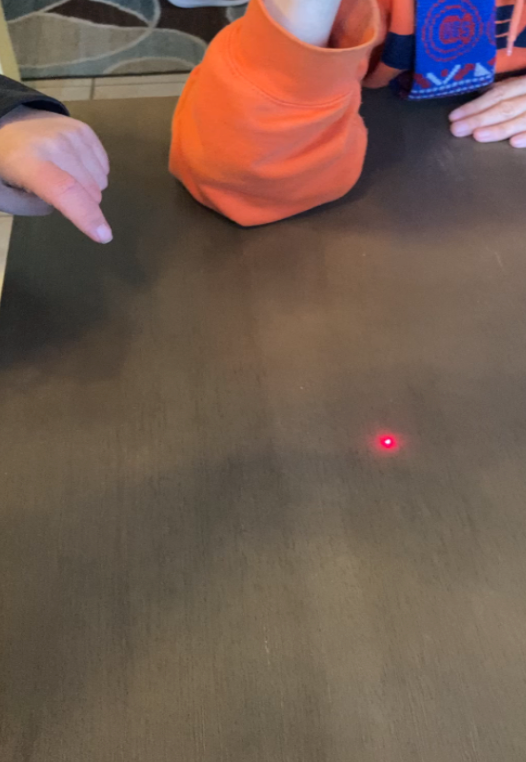

- Use a laser pointer or flashlight to direct attention to target objects.

- Create a need: Make something visible but not accessible.

Using a laser pointer is another strategy, as seen in Figure 9.

Figure 9. The author uses a laser pointer for joint attention.

Using a laser pointer for joint attention and incorporating it into pre-writing skills is a creative and effective strategy. It aligns with the child's visual preferences and helps transfer the skill to functional activities like handwriting. Creating a need but not making it visible, especially with light-up toys, is a clever approach. It encourages the child to engage with you to access the desired toy, providing a natural incentive for joint attention. This method combines the child's interests with skill development in a motivating and engaging way.

- Block the stimming behavior, HOH to complete put in task, then provide stimming opportunity

- Use toys they stim on using on/off buttons

- Use a 1:1 ratio

Introducing a replacement toy that still provides the desired sensory input while encouraging attention to different aspects is a thoughtful strategy. It acknowledges the child's sensory preferences and gradually expands their focus to other toy components. This approach respects the child's need for specific sensory input while guiding them toward broader engagement. It's a practical method to transition from preferred toys and supports the development of joint attention by introducing variety within the child's sensory comfort zone. Figure 10 shows an example of this.

Figure 10. The author is showing a light-up toy near her face.

Using a controlled setting with specific toys to gradually transition from preferred items is a considerate approach. It ensures that the child still receives the sensory input they seek while encouraging joint attention. The controlled access to the toy, limited to special "mommy and me" or "daddy and me" times, establishes a structured environment for joint attention activities. Additionally, the suggestion of using a one-on-one ratio, alternating between joint attention activities and free play, recognizes the importance of balancing structured and unstructured interactions. This approach respects the child's need for self-regulation while progressively incorporating joint attention into their play routine.

- Use tactile boundaries: Using preferred/on preferred sensory items

- Play-Doh

- Wikki Stix

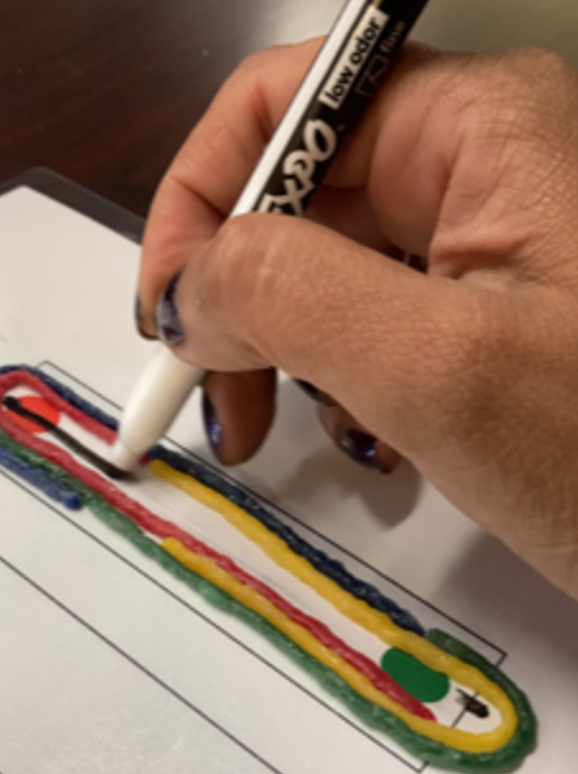

Another strategy is using sensory preferences to help you facilitate joint attention. Figure 11 shows the use of Wikki Stix.

Figure 11. The author is showing an activity with Wikki Stix.

Using tactile and visually engaging materials, such as Wikki Stix and Play-Doh, to facilitate joint attention during pre-writing activities is a creative strategy. The wiki sticks provide a tangible guide for the child's finger, creating a clear starting point for pre-writing strokes. This approach recognizes that visual stimuli may be perceived differently by children with autism, and providing additional cues helps them initiate purposeful engagement.

Pairing preferred and non-preferred items, like Play-Doh, is an effective way to redirect attention towards activities that might not typically attract the child. By incorporating a small amount of Play-Doh onto an object, you've created a connection between the familiar (Play-Doh) and the less familiar (the object). This encourages the child to interact with items they might otherwise overlook, promoting joint attention while engaging in purposeful play.

- Use contrasting backgrounds, larger visuals, real pictures, and hard Velcro

- Limited access to toys in the environment

- Favorite character stickers on the face

- Sing songs they like

Contrasting backgrounds, larger visuals, real pictures, and using hard Velcro are options. One activity is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. An example of a contrasting activity.

Using hard Velcro circles as tactile markers in books is a clever way to provide a textural cue for children who struggle to interpret pictures alone. This strategy recognizes the importance of incorporating multiple sensory modalities to enhance engagement and comprehension. By offering a tangible element like Velcro, you create an additional layer of sensory information, aiding their orientation and interaction with the content.

Limiting access to too many toys in the environment is a practical approach to avoid overwhelming the child and encourage sustained attention to specific activities. Stickers, especially those featuring preferred characters like Cocomelon or Thomas, offer a personalized and engaging element. Incorporating stickers into interactive activities, such as placing them on your face and having the child peel them off, adds a playful and sensory-rich component to the learning experience.

Creating contrast, as demonstrated with the larger Goldfish picture, is an effective strategy for drawing attention to specific elements. Using contrast can help highlight important details and increase visual saliency, facilitating the child's focus on relevant aspects of the activity or material.

- Create a need to access to favorite toy

- Sensory play/obstacle course

- Vestibular input

- Boundaries

- Succinct phrases

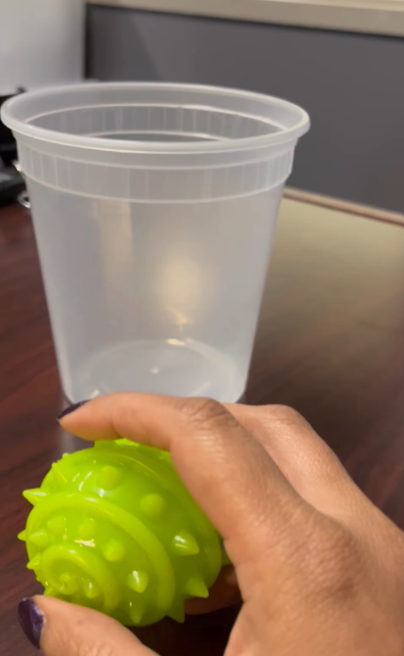

Another strategy is creating a need to access a favorite toy. Figure 13 shows an example of a ball I use.

Figure 13. An example of a ball the author uses.

Creating contrived situations that naturally spark a child's interest, such as covering a ball with your hand and then asking if they want you to open it, is an effective strategy. This approach leverages the child's motivation to initiate interaction, fostering joint attention in a playful and engaging manner. However, ensuring the child is regulated before engaging in one-on-one scenarios is crucial, emphasizing the importance of prior sensory play, obstacle courses, and vestibular input.

Establishing boundaries in the environment becomes especially important for children with difficulties in perceptive input, helping them better understand their body and spatial awareness. Small, boundaries areas create a sense of security and structure, supporting the child's comfort and focus during joint attention activities. Succinct phrases, tailored to each child's speech needs, streamline communication and ensure clarity in the instructions you and the speech therapist provided. A scripted approach allows consistency and individualization based on the child's unique requirements.

Summary

- Never force...always reinforce.

When working with children with joint attention issues, reinforce rather than force. The motto emphasizes building positive associations and experiences around joint attention. Forcing a child into activities or interactions can lead to resistance and negative associations, hindering the progress aimed for in the intervention.

Thank you.

References

Ambrose, D., MacKenzie, D. E., & Ghanouni, P. (2020). The impact of person–environment–occupation transactions on joint attention in children with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83, 350–362. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0308022620902681

Dargue, N., Adams, D., & Simpson, K. (2022). Can characteristics of the physical environment impact engagement in learning activities in children with autism? A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 9, 143–159

Eschenfelder, V. G., & Gavalas, C. M. (2017). Joint attention and occupations for children and families living with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1349

Gabouer, A., & Bortfeld, H. (2021). Revisiting how we operationalize joint attention. Infant behavior & development, 63, 101566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2021.101566

Gomes, S. R., Reeve, S. A., Brothers, K. J., Reeve, K. F., & Sidener, T. M. (2020). Establishing a generalized repertoire of initiating bids for joint attention in children with autism. Behavior Modification, 44(3), 394–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445518822499

Gutstein, S. E. (2009). Empowering families through relationship development intervention: An important part of the biopsychosocial management of autism spectrum disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry, 21(3), 174-182.

Guy, J., Mottron, L., Berthiaume, C., & Bertone, A. (2019). A developmental perspective of global and local visual perception in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 2706-2720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2834-1

Jones, E. A., & Carr, E. G. (2004). Joint attention in children with autism: Theory and intervention. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576040190010301

Jhuo, R.-A., & Chu, S.-Y. (2022). A review of parent-implemented Early Start Denver Model for children with autism spectrum disorder. Children, 9, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020285

Kose, B., Karabulut, E., & Aki, E. (2021). Investigating the interchangeability and clinical utility of MVPT-3 and MVPT--4 for 7-10 year children with and without specific learning disabilities. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 10, 258-265. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 21622965.2019.1681270

Mello, M., Rogers, S.J. (2022). Overview of the Early Start Denver Model. In: Leaf, J.B., Cihon, J.H., Ferguson, J.L., Weiss, M.J. (eds) Handbook of Applied Behavior Analysis Interventions for Autism. Autism and Child Psychopathology Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96478-8_17

McAuliffe, T., Apps, B. & Setchell, J. (2023). Using relationship development intervention with autistic children and their families: The experiences of RDI consultants in Australia. J Dev Phys Disabil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-023-09925-5

Nowell, S. W., Watson, L. R., Crais, E. R., Baranek, G. T., Faldowski, R. A., & Turner-Brown, L. (2020). Joint attention and sensory-regulatory features at 13 and 22 months as predictors of preschool language and social-communication outcomes. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research: JSLHR, 63(9), 3100–3116. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00036

Nyström, P., Thorup, E., Bölte, S., & Falck-Ytter, T. (2019). Joint attention in infancy and the emergence of autism. Biological psychiatry, 86(8), 631–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.05.006

Özkan, E., Belhan Çelik, S., Yaran, M., & Bumin, G. (2023). Joint attention-based occupational therapy intervention in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 77(2), 7702205090. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2023.050177

Shih, W., Shire, S., Chang, Y. C., & Kasari, C. (2021). Joint engagement is a potential mechanism leading to increased initiations of joint attention and downstream effects on language: JASPER early intervention for children with ASD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 62, 1228-1235. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jcpp.13405

Su Maw, S., & Haga, C. (2018). Effectiveness of cognitive, developmental, and behavioural interventions for autism spectrum disorder in preschool-aged children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon, 4, e00763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00763

Citation

Mehra, A.(2023). Joint attention based interventions for preschoolers with ASD. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5674. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com