Introduction

Good afternoon, everybody. I am glad you were able to put aside an hour and join me. The title of today's program is Living Life to its Fullest. That happens to be, as you know, a logo for AOTA. An older one was Skills for the Job of Living. Today's program is going to focus on ways that we can improve each breath. It is not just for people with COPD. Everything that I will talk about today applies to that population of people, but more broadly, this piece is for all of our clients.

I discovered in my 20 plus years of work, especially my first few years, that most of the people, regardless of diagnosis, were breathing inefficiently. I also realized that my formal education had not really dealt with that. Thus, I really had no skills to help my clients. I tried to teach them the components of diaphragmatic breathing, but I ended up confusing them. As a result, they started to breathe more inefficiently.

I had to start exploring different ways of breathing from Eastern and Western traditions. Through trial and error, I started to identify ways to help my clients breathe more efficiently. I even created a breath group called Peak Performance to help clients re-engage in meaningful occupations. This worked on improving their endurance and strength. However, we also have to support their breathing habits to support their engagement in occupations. I hope today's program will give you some additional tools to serve your clients well.

Breath - The Bridge Between Mind and Body

Breath is the foundation between the mind and body. Think about if you are upset or worried about something. Your breathing gets shallow. Or, if you are in physical pain, this also restricts your breathing. We can use breathing techniques to quiet the mind and to relax the body. Towards the latter part of the presentation, we will come back to that and use that as a guide in helping people breathe more efficiently.

We breathe in and out over 20,000 times per day. Thus, it makes sense that we should know a little more about this process as it impacts every aspect of well-being. Breathing affects every organ of the body.

- Cerebrum, Thalamus, Hypothalamus

- Cerebellum, Extra Pyramidal Centers

- The pH of the Blood

- CO2

- O2

- Vessels

- Joints

- Muscles/tendons

- Skin, mucous membranes

- Lungs

- Heart

- Solar plexus

Many people believe that breathing should be like a metronome with a consistent inhale and exhale at the same rate all the time. That is not true. This would actually contribute to inefficient breathing. Breathing needs to be dynamic and adapt moment to moment based upon the activities we are engaged in. If you are sitting and reading a book, you are going to breathe one way. If you are bending down to don and doff a pair of shoes, your breathing needs to adjust to accommodate that. Breath is fluid and dynamic. That is healthy breathing. If we get stuck in a pattern like a metronome, it will not support occupations.

External Respiration Versus Internal Respiration

When we think about breathing, we can think of it in external respiration and internal respiration.

External Respiration

- Breathing occurs at the level of the lungs

- Body Structures: anatomical parts of the body that influence the efficiency of each breath:

- spine, ribs, pelvis, muscles, posture, and our thinking

External respiration includes the things that contribute to the air getting into the lungs. For example, when working with someone with COPD, we cannot change the lung disease process. However, if we improve the muscles and joints' mobility, posture, and mindset, we can optimize each breath.

Internal Respiration

- What occurs at the tissue and cellular level

- Body Functions: physiological functions of body systems

Internal respiration is what happens at the cellular level once the air gets into the lungs. We will focus primarily on external respiration today, but obviously, it has a direct relationship to what goes on with internal respiration.

Common Breath Holding Patterns

- Chest Breathing

- Reverse Breathing/Paradoxical Breathing

- Collapsed Breathing

- Hyperventilation

- Dyspnea

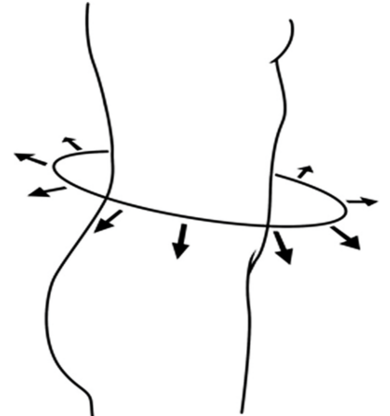

I want to review a couple of the common holding or inefficient breathing patterns that we see with our clients. The first one is chest breathing. It is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Illustration of chest breathing.

It shows primarily how the shoulders go up and down with inspiration, and the diaphragm is not moving much. Many clients of mine breathe this way. If I tell them to take a deep breath, their shoulders will go up, their chest expands, but there is not much movement lower down. The secondary muscles of respiration, the scalenes (SCM), are doing a lot more work than they should, and the diaphragm, the primary muscle, is barely contributing. The diaphragm is not being utilized to full capacity. This creates a more rapid and shallow breath.

Reverse breathing or paradoxical breathing is in about 10% of the people that I work with. If you put your hand on your belly and you breathe in, you should feel the belly bulge out a little bit. When you exhale, the belly should go in. Ten percent do the reverse. When they breathe in, the belly pulls towards the spine, and when breathing out, it goes in the opposite direction. This can be changed as it is not a healthy pattern of breathing. What we are going to discuss today will help these people. Clients that perform paradoxical breathing just need a little more time to get that pattern turned around.

Collapsed breathing has a lot to do with posture. This is where the person is hunched over and collapsed in the front. This poor posture influences their breathing.

Many people can demonstrate a mild version of hyperventilation with their respiratory rates in the low 20s.

All of these combined lead to dyspnea or shortness of breath.

Impact of These Breathing Patterns

- Chronic tension in the upper body, especially around the neck, shoulders, back, and jaw

- Anxiety and increased stress response (heart disease, hypertension)

- Lack of circulation in the abdominal area leading to indigestion, heartburn, and bloating

- Greater difficulty learning movement because the basic pattern of breathing (movement) can be upside down

- Confused and disoriented state of mind

The impact of these poor breathing patterns can be chronic tension in the upper neck muscles and scalenes as they are overworking. People often have chronic pain in their neck pain, shoulders, or jaw. The rapid respiratory rate leads to an increased stress response, which directly relates to heart disease, hypertension, and many other issues. The stress response also ties directly to the lack of circulation in the abdominal area, contributing to indigestion, heartburn, and bloating. If a person is in a fight or flight mode because their respiratory rate is quick, the blood that would normally be in their belly is going to be shunted to their arms, legs, and brain in preparation for flight. So, even when there is no threat, rapid breathing can kick off a sympathetic response that will influence digestion.

Efficient Breathing

- More energy to engage in occupations

- A calmer, clearer perspective

- Manage pain

- Greater ease of movement

When we breathe inefficiently, movement becomes a challenge. For example, if I am trying to help a client learn how to weight shift, but they are breathing inefficiently, they may not be able to coordinate their breath with the task. And, if they have a mild version of hyperventilation, this can lead to confusion or a slightly disoriented state.

Figure 2. More efficient breathing pattern with diaphragmatic movement.

This picture is showing a more efficient breathing pattern. You can see the diaphragm moving up and down. On inhale, it goes down, and on exhale, it goes up. We also do not see the shoulders moving in this illustration, but they should move slightly.

During belly breathing, as the diaphragm goes down, it compresses the abdominal organs. If the abdominals are relaxed enough, the belly will pop out. We often refer to this as diaphragmatic breathing or belly breathing. Air obviously does not go into the belly.

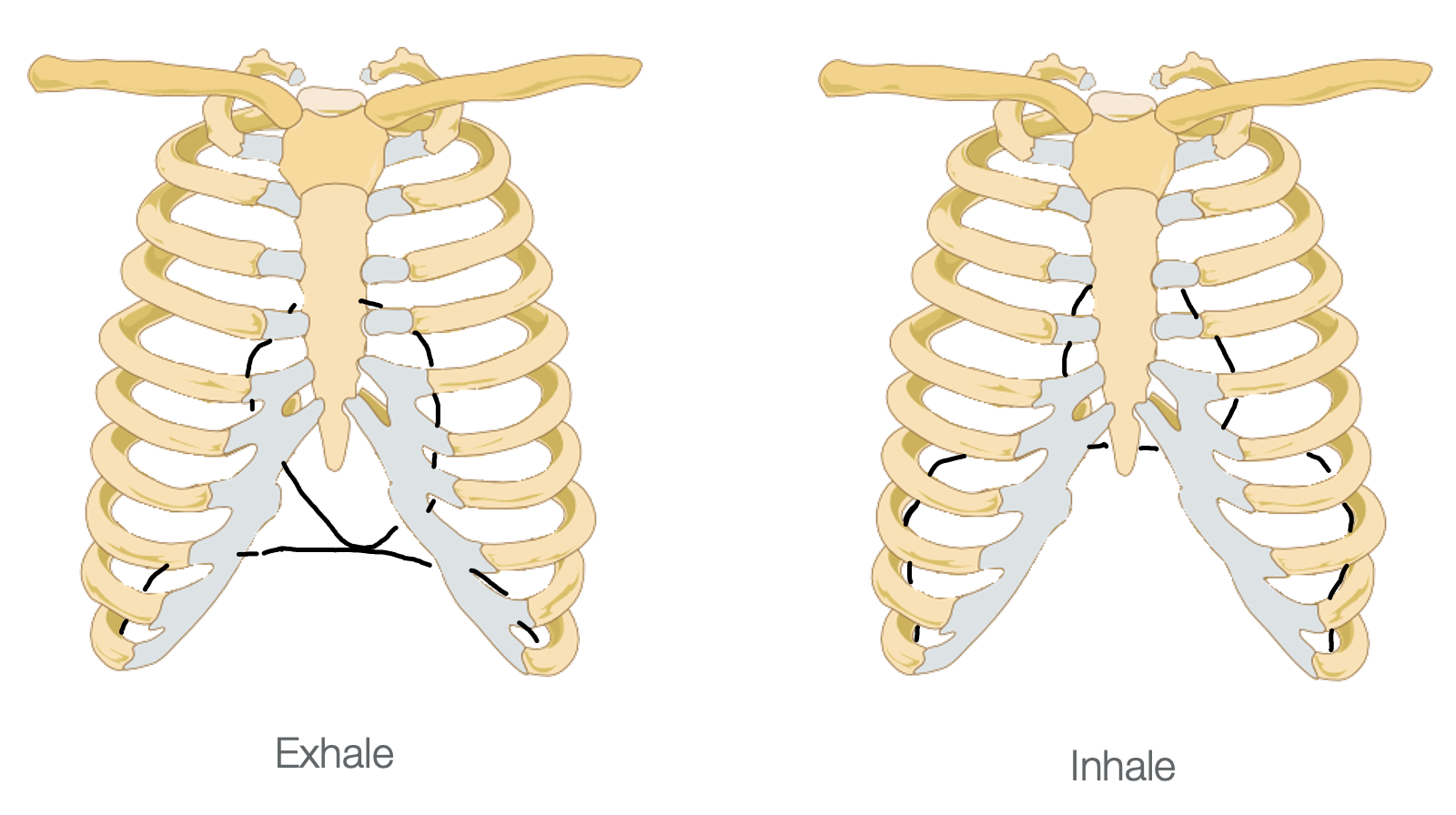

The diaphragm, a big powerful muscle, pushes down on those abdominal organs and the belly. As I said, the abdominals will expand if they are not bound or too tight. Figure 3 shows two triangles superimposed on the body of a gentleman.

Figure 3. The upright triangle represents efficient breathing, and the upside triangle represents inefficient breathing.

When we breathe more efficiently, the base of the triangle (on the left) is larger, representing more movement related to breathing. We should feel more movement in the stomach area and less movement towards the neck/shoulders (apex of the triangle). For many people, the triangle is upside down with more movement up top and less movement down below (right picture).

As we help our clients to breathe more efficiently, what are the benefits? They have the energy to engage in occupations. They also have a calmer or clearer perspective because they engage the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. It can help to manage pain. Some of you may have attended the pain symposium on OccupationalTherapy.com. I repeat a little of that talk to reiterate that breath is a wonderful way to help manage pain. And, as we start to breathe more efficiently, the movement gets easier. This is the goal.

Anatomy of Breathing

Diaphragm

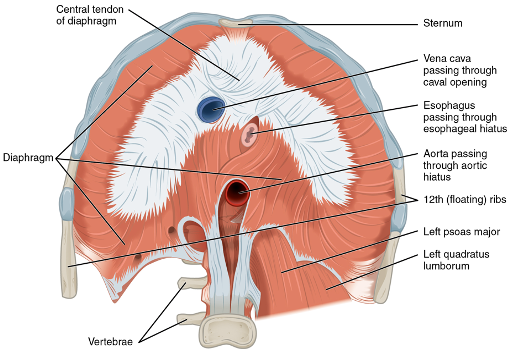

Let's talk now a little bit about anatomy. The diaphragm is huge, as you can see in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Cross-section of the body showing the diaphragm (OpenStax, CC by 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons). Click here to enlarge the image.

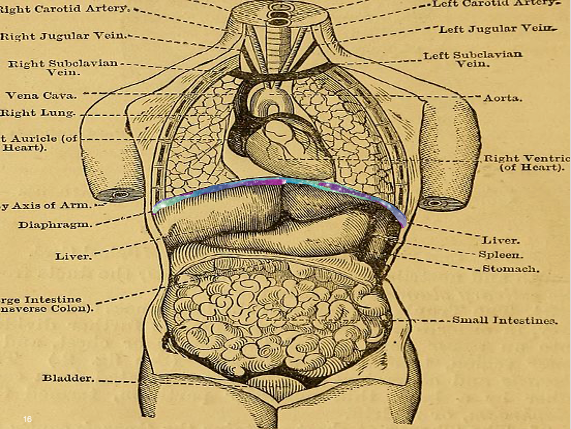

The diaphragm attaches all the way around the body, from the lower ribs in the front to the back to the spine. Figure 5 shows the diaphragm as a multicolored little line that separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity.

Figure 5. Diaphragm indicated by the colored line (Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons). Click here to enlarge the image.

When we inhale, the diaphragm presses down on the organs, and they will come forward a little bit. As the diaphragm goes all the way around, there should be movement in the front, around the waist, and in the back of the body. You will not feel as much movement in the back because of the spine. Most of the movement will be in the front by the belly. The diaphragm is like a cylinder that expands and can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The diaphragm moves outward on the body during inhalation.

One of the things I work on with people is I want them to get that experience of not only feeling the movement in the front but around the waist and in the back. I want them to have that sensory experience. When they are doing occupations and can stop, they then have a reference. "What's my breathing like at this moment?" They can see if they feel movement all the way around?

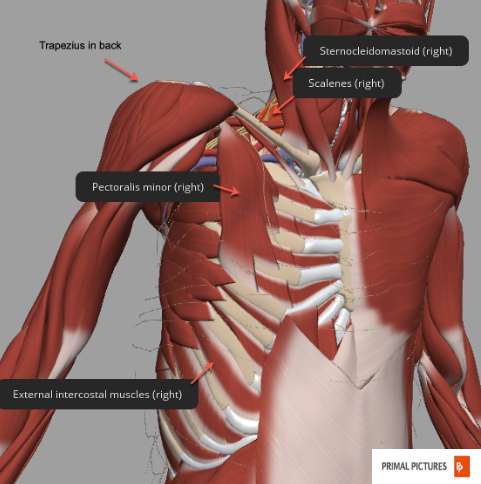

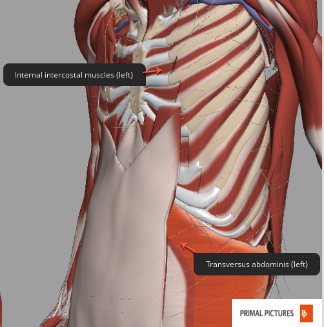

Secondary Muscles

The primary muscles are the diaphragm and the external intercostal muscles. The secondary or accessory muscles can be seen in Figures 7 and 8.

Figure 7. Anatomical photo showing the trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, pectoralis minor, and external intercostal muscles on the right side. Click here to enlarge the image.

Figure 8. Anatomical photo showing the internal intercostal and transversus abdominis muscles on the left side. Click here to enlarge the image.

If we do not let the diaphragm do what it is designed to do, it will create space for oxygen. These secondary muscles, which are part-time players, are made to work full-time. These muscles kick in, lift the upper ribs, and then let them come back down. Again, with 20,000 cycles of breath per day, those muscles get tired very quickly.

Core Functions

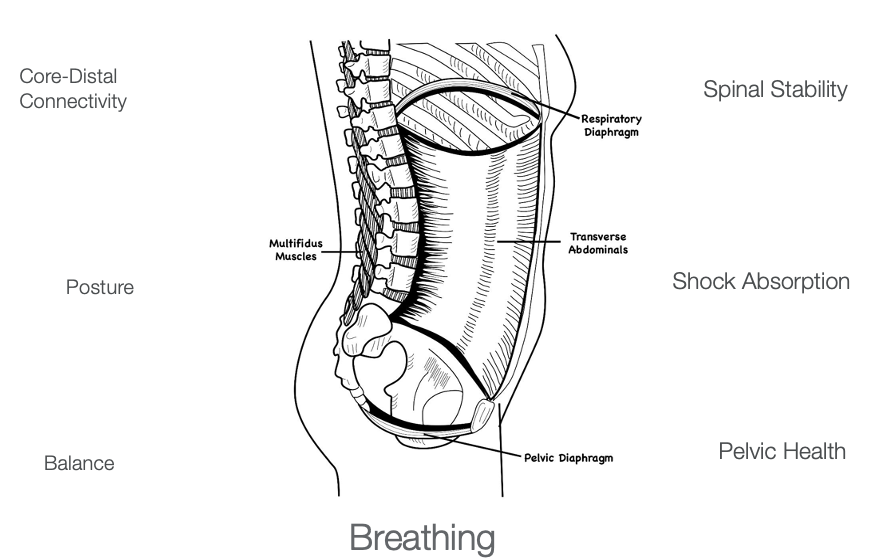

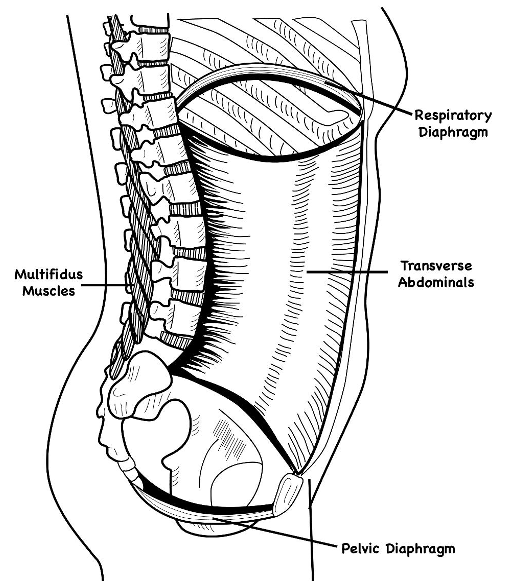

The diaphragm, represented in this drawing in Figure 9, is part of the core function.

Figure 9. The diaphragm is part of core function and can be seen in relation to the body and the pelvis. Click here to enlarge the image.

A common term today is "the core." When people think about core strengthening and core development, they often think about the abdominals. People try to get that six-pack, firm, and flat belly. However, this can lead to a lot of problems. If the core is too firm and tight, this will restrict the ability of the diaphragm to move down. The secondary muscles of respiration then need to kick in to create space for oxygen. Although it is not efficient, it is better than not getting enough air to function. However, this is not done healthily, as we discussed earlier. Ultimately, the respiratory diaphragm is part of the core. Thus, core functioning needs to incorporate the respiratory diaphragm, and the pelvic floor, also called the pelvic diaphragm.

In Figure 10, we see a close-up of the previous image.

Figure 10. Here is a close-up view of both of the diaphragms.

In this view, you can see the respiratory diaphragm at the top, the pelvic diaphragm at the bottom, the abdominals in the front, and the multifidus in the back. For core strengthening, there has to be coordination among all these different parts. If we do not do core strengthening correctly or over involve the abdominals, this will restrict breathing. Core functioning is integral to posture, balance, and spinal stability. It also acts as a shock absorber. Pelvic health, which I will discuss in another program, and core-distal connection, meaning core stability, enables us to have more mobility distally.

I want to clarify another point that the respiratory diaphragm. When it comes down and compresses all those abdominal organs, the pelvic diaphragm or floor also moves down. When we exhale, and the diaphragm goes up, the pelvic floor should also go up. This is called the dance of the diaphragm. They move together for efficient breathing. Thus, if there are pelvic health issues, this will also contribute to restricted breath.

- Over 80 Joints

- The ribs are deformable & elastic

- Costal cartilage is the most flexible

When we look at the body structure level, the ribs have 80 joints. There are three joints in the back where the rib attaches to the body. There is the joint in the front, except for the floating ribs. I always envision an accordion. The ribs move to create flexibility and adaptability during breathing. We need to keep the ribs flexible. We have to include these as well as the spine in our interventions.

Nose and Nasal Cavities

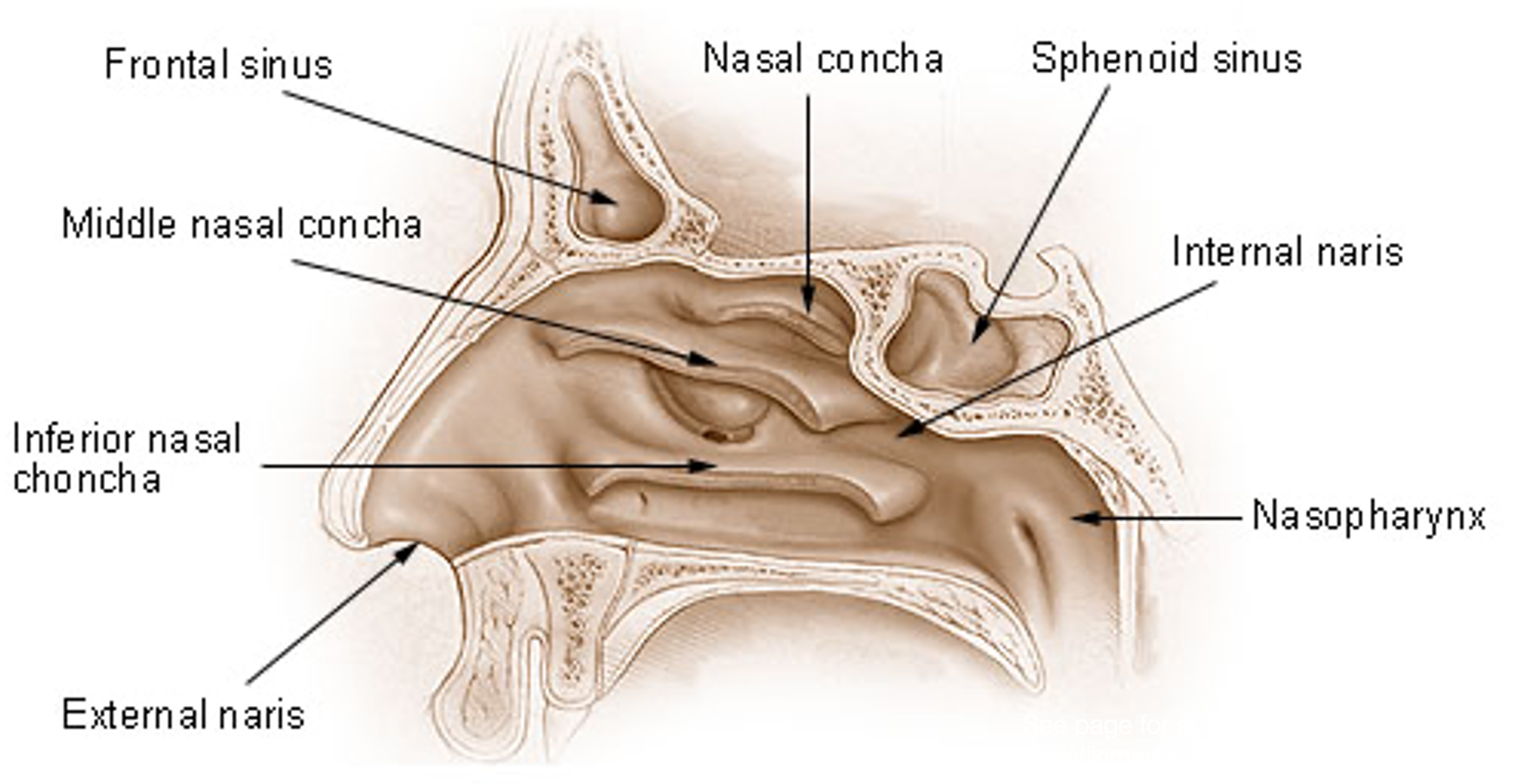

Should we breathe in through the nose, or should we breathe in through the mouth? This is a question I often get. When we breathe in through our noses, the air goes through different pathways, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Nasal pathways. Click here to enlarge the image.

These are sometimes referred to as turbines.

Nose Versus Mouth

- Nose

- air is warmed and humidified

- cleaned of dust particles

- cleaned of bacteria

- Mouth

- more air in during intense physical activity

- when trying to inhale quickly

- for techniques requiring the deepest exhalation possible

- greater ability to vary airflow

Some little hairs or cilia catch the dust. The membranes also have an antibacterial on them. This helps kill some of the bacteria. The nasal canal also humidifies the air. Even with these benefits of nose breathing, this does not mean that you do not breathe in through your mouth. We need adaptability. Nothing is just one way. If we need more air during physical activity, breathing through the mouth is okay. If we have to inhale quickly to get more air in, that is also okay. When we really want to exhale deeply, exhaling through the mouth is good. A greater ability to vary airflow happens through the mouth. Ideally, most of the time, when a client is relaxed and not engaged in an activity, I would like them to breathe through their nose.

Heart and Breath

Let's now talk about the heart concerning breathing. In this image, you can see the heart brushing up against the diaphragm (Figure 12).

Figure 12. The anatomical relationship of the heart to the diaphragm.

What we are not seeing is the pericardium that is around the heart and attaches to the diaphragm. In Figure 13, you can see that the heart and diaphragm are pulled down every time we breathe in. And when we exhale, the diaphragm goes up, and it lets the heart come back up.

Figure 13. Position of the heart in the rib cage during exhalation and inhalation. (Mikael Häggström, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The heart gets gently massaged with every breath.

What Restricts Movement?

What restricts the diaphragm, which in turn greatly impacts breathing?

Sitting Posture

Posture is a big thing and one of the first things I look at with my clients. Many people sit in a slumped posture. Figure 14 shows a bowling ball in place of the person's head as a metaphor for how heavy it can get with poor posture.

Figure 14. Bowling ball represents how heavy a head can feel. (Bowling ball: Photo by IBRAHIM AL JARUSHI on Unsplash)

Our head weighs eight to 10 pounds. And, if we are not aligned, this can put a lot of stress and strain on the neck.

Let's try something quickly to illustrate that point. Sit all the way back in your chair. You want your lower back to be flush with the back of the chair and to be sitting upright. Now, observe your breathing. Try not to control it in any way. Notice what the breath feels like. Then, I want you to come forward, so you are slumping in your chair with a little bit of a rounded back. You want your pelvis away from the back of the chair. What does it feel like in that position? Your breath should change. If you are not sure, go back and forth between the two positions. There should be one position that clearly allows your breathing to be a little bit deeper and easier. How many of you noticed that your breathing feels a little deeper when you are sitting upright than when you are slumped? It is important to look at how your client is sitting and create a new habit for sitting. There is nothing wrong with slumping a little bit, but if that is how the person sits all the time, their abdominal muscles are kept in a shortened position. If a person is in that position a lot during the day, it might be harder to stand upright as the muscle fibers have accommodated to the favored position. The abdominals will be tighter so that when the diaphragm tries to move down, the abdominals cannot release as freely as they need to for the diaphragm to descend fully.

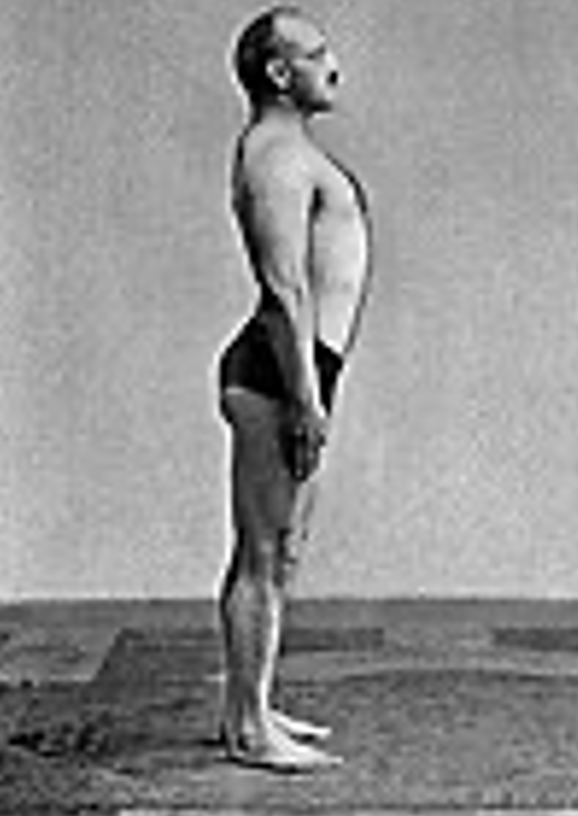

Standing Posture

We also need to look at standing posture. People are always asking me what good posture is. When I say, "Show me a good posture," they may do something like Figure 15.

Figure 15. Military-type upright posture.

This is a military-type posture with the knees are locked, chest out, and belly sucked in. Assume that posture for a moment if you can do so. Lock your knees, and let your breathing come and go. See what that feels like. Then, soften your knees a little bit and see how that influences your breathing. Many people that I work with are knee lockers. You are probably going to notice that when you let your knees soften, the breath gets naturally deeper. Think of how many standing activities our clients do. Helping them create this new habit of softening their knees when they stand will improve the quality of their breath and lower their center of gravity, take the pressure off their knees, and increase their stability.

Aesthetics

The other issue is aesthetics. Again, people like the "six-pack" stomachs. We already discussed why that is not a great thing for breathing. Also, people tend to try to fit into tight clothes, restricting the abdominal area. With both of these scenarios, the diaphragm does not work as well, causing the scalenes and secondary muscles to kick in. If we squeeze a tube of toothpaste in the middle, the toothpaste moves up or down from the middle. This is like the diaphragm. If you squeeze the middle, this restricts both the respiratory and pelvic diaphragms.

Surgeries

Abdominal surgeries can restrict breathing. Not only are there abdominal sutures, but people do not move their bellies due to pain. It is a compensatory pattern like anything else. If somebody has pain in the leg, they do not put pressure on it. Once the pain is gone, the habit is in place. This is the same thing with breathing if they are restricted post-surgery.

Emotional and Physical Pain

Emotional and physical pain can also be restricting.

Soft Tissue Restrictions/Joint Limitations/Habits

There can also be soft tissue restrictions and joint limitations. Again, the habit of keeping abdominals tight may be where a person holds in emotion or maybe because they do not want their belly to stick out due to aesthetics.

Respiratory Volumes

- The volume of airflow is never the same from one breath to the next

- Variations in activity create different demands for oxygen

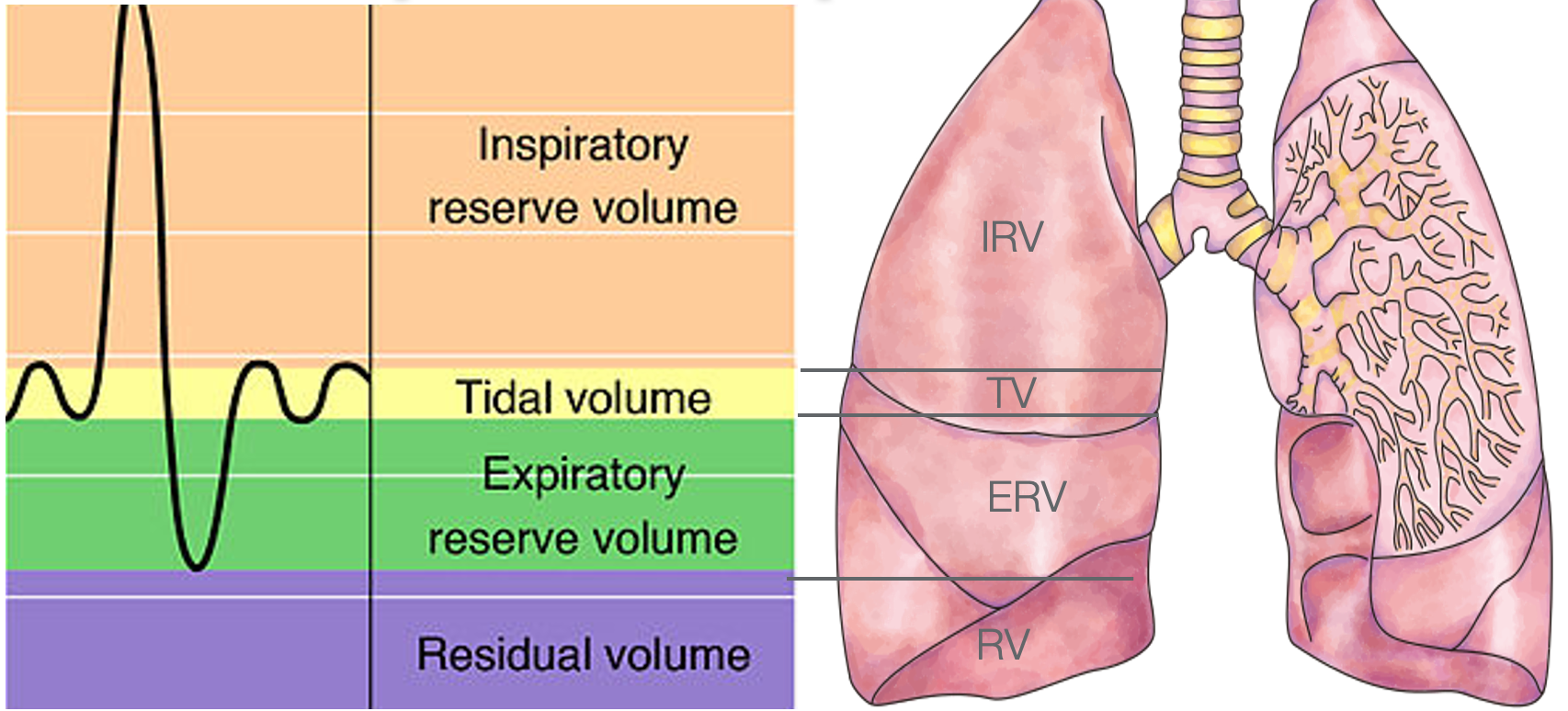

Let's now talk briefly about lung or respiratory volumes. This will help you to understand the treatment aspect of breath a little bit more. I want to talk about inspiratory reserve volume, tidal volume, expiratory reserve volume, and residual volume. As I said at the beginning of this discussion, the airflow volume is never the same from one breath to the next, or at least it should not be. The demands of activity will create different demands for oxygen.

Looking at Figure 16, here are the different respiratory volumes on a chart.

Figure 16. Different respiratory volumes on an x/y axis. (OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons; DataBase Center for Life Science (DBCLS), CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

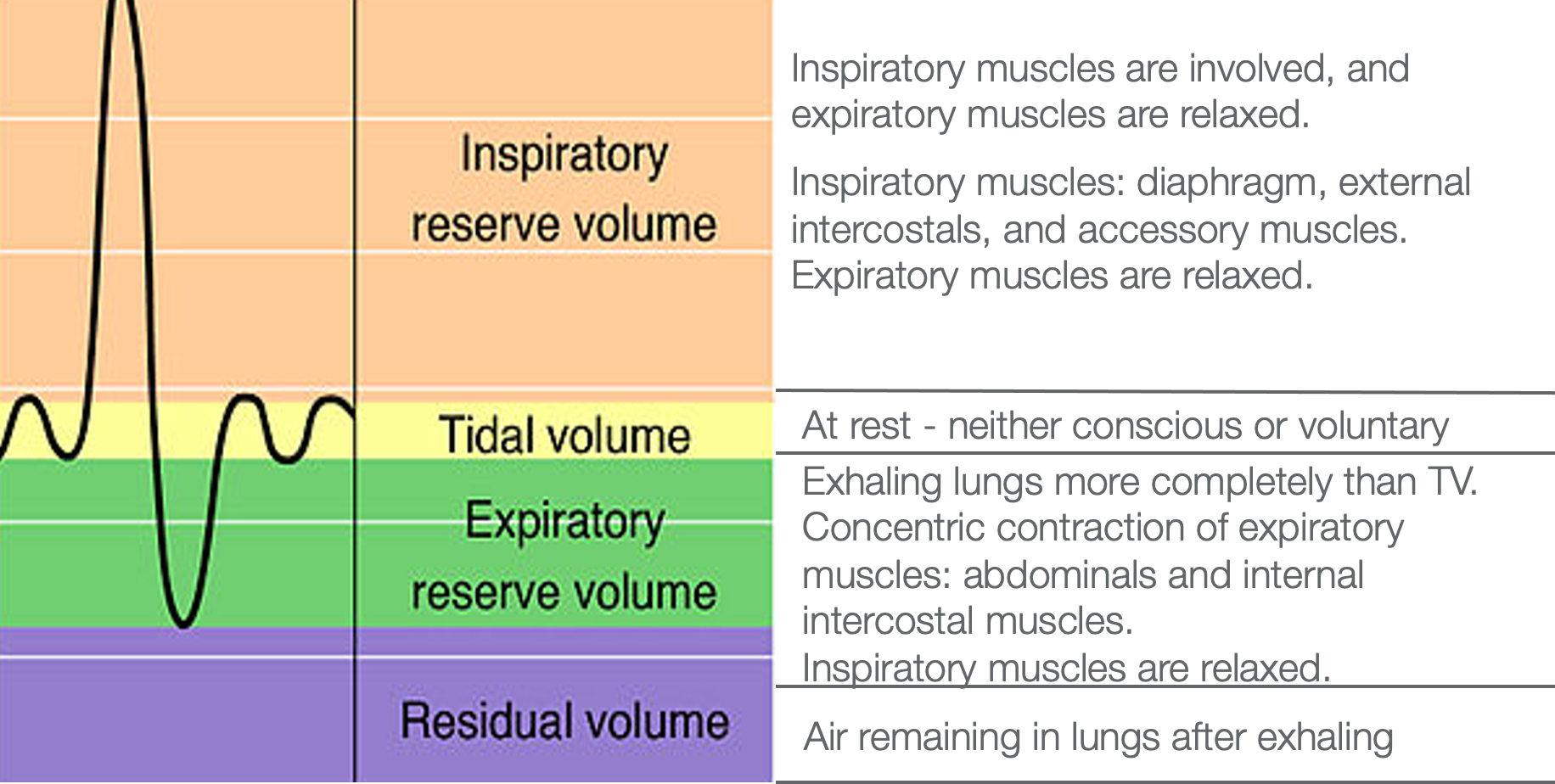

The tidal volume (yellow line) happens when we are at rest, and it is on the x-axis of this image. We do not have to think about it. Breathing is voluntary, and there is a normal elasticity in the pulmonary system. And, when you exhale, it rebounds with not a lot of muscular effort. However, when a client performs an activity, they may need more oxygen. The diaphragm and the external intercostals start to be more engaged to help bring in more oxygen. Let's look at this respiratory volume image again for more details (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Different respiratory volumes on an x/y axis with definitions of each type/volume of breath in the lungs.

During this time, the expiratory muscles, primarily the abdominals, have to be relaxed during this inspiration. When a client takes in this big breath to support the demands of the activity, we exhale through an eccentric contraction of those muscles if we do it healthily. It is concentric as we inhale, eccentric as we exhale,

To get more air in, we have to get more air out. As a client exhales, the air content goes below tidal volume (below the x-axis) in the lungs and then moves into an expiratory reserve level. Due to the dip in the air volume, the client now has to get more air in. This is where the abdominals kick in. As they begin to push the air out, they spontaneously relax the abdominals to allow more air to come in. At this point, when they have taken in that big breath, they gently begin to do an eccentric contraction to get the air back to a tidal volume. This is when the inspiratory muscles need to relax. Even when we exhale, there is always air in the lungs called the residual volume. People with things like COPD have more residual volume or more air left in their lungs. It is harder for them to get more air in due to this.

- Inhaling after ERV:

- After an intense exhalation, it is enough to relax the expiratory muscles

- Elasticity will allow:

- Ribs to return to their original curvature

- Lungs to expand to tidal volume

I will give you an example of how you can get more air out (if you are healthy) for you to get more air in. This technique would also be good for somebody with COPD. Sit back in your chair with your lower back flush with the back of the chair. Take a moment to notice your breathing. Of course, it is changing a little bit because you are thinking about it. Notice what your inhale feels like and how much the body (belly and chest) moves as you are breathing in. You are now at the tidal volume as if you were sleeping. Now, take a breath in. When you exhale, keep going. Put your hands on your belly and feel your belly come in until you cannot exhale anymore. Once you have exhaled as much as possible, relax your belly 100% and see what happens. Again, take a breath in, exhale using a "pffff" sound (like with pursed-lip breathing), and then relax the belly. What you may notice is that the belly pops out, and you get a large breath in spontaneously. This is the thinking behind pursed-lip breathing. It slows the respiratory rate. It creates a back pressure which opens up the airways to allow more air to come out. The other piece is that it engages the abdominals. The abdominals can help push more air out so that spontaneously you can get more air in.

- Respiratory volumes will vary depending on the size, physical fitness, and health of the individual

- Treatment focus:

- Increase IRV

- increasing flexibility of rib cage/spine, pelvis, and abdominals.

- quieting the mind, reducing stress

- strengthening of diaphragm

- Increase ERV

- strengthening abdominals (emphysema)

- maintaining suppleness

- Increase IRV

Remember, all of these respiratory volumes depend upon the size and fitness of the person. From a treatment focus, it is important to increase the inspiratory reserve volume. This is not rocket science. To do so, we want to increase the flexibility of the rib cage and the spine. We also want to increase movement at the pelvis. Can they go anterior and posterior? Can they do lateral weight shifts? How much flexibility is in the pelvic region? Are the abdominals too tight? Are they generally weak? Let's not forget about thinking. Reducing stress is also a key factor. We also need to strengthen the diaphragm. I will talk a little later about how you can straightforwardly do that.

For increasing the ERV, you want to maintain suppleness. You do not want to strengthen the muscle fibers so tight that they cannot release. Remember, every healthy muscle in the body has the ability to lengthen and shorten. This is what I mean by suppleness. We want to make sure that the muscles can do that. Do not over-strengthen those abs; make sure they maintain suppleness.

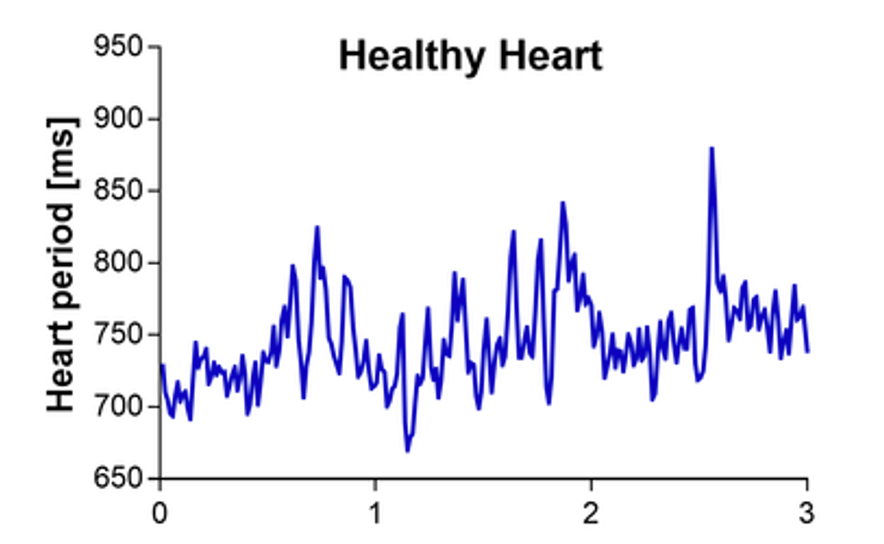

Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia or Heart Rate Variability

The next thing I want to talk about is heart rate variability. This is also called respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Should the exhalation be longer than the inhalation? Most of us would say, "If the exhale is longer, that is a good thing." I want you to find your radial pulse. Put two fingers there and feel the pulse. If you cannot feel that well, you can go to the carotid pulse. I want you to notice what happens when you breathe in and out. You can also use pursed-lip breathing, where you breathe in through your nose, and you exhale slowly as if you are trying to blow a bubble. See what happens. When you breathe in, what happens to the heart rate? When you breathe out with pursed-lip breathing or making the "pfff" sound, what do you notice? The heart rate slows when we exhale. This is called respiratory sinus arrhythmia. There is the up and down or the heart rate variability, as seen in the chart in Figure 18. This is healthy, and we want that variability of the heart rate going up and down.

Figure 18. The variability of heartbeats (pulse) per millisecond on a graph. (Mathias Baumert, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

What is a Normal Respiratory Rate?

Now, I am going to talk about heart rate and get into hyperventilation.

- Neonatal 30-60

- Early Childhood 20-40

- Late Childhood 15-25

- Adult 12-16

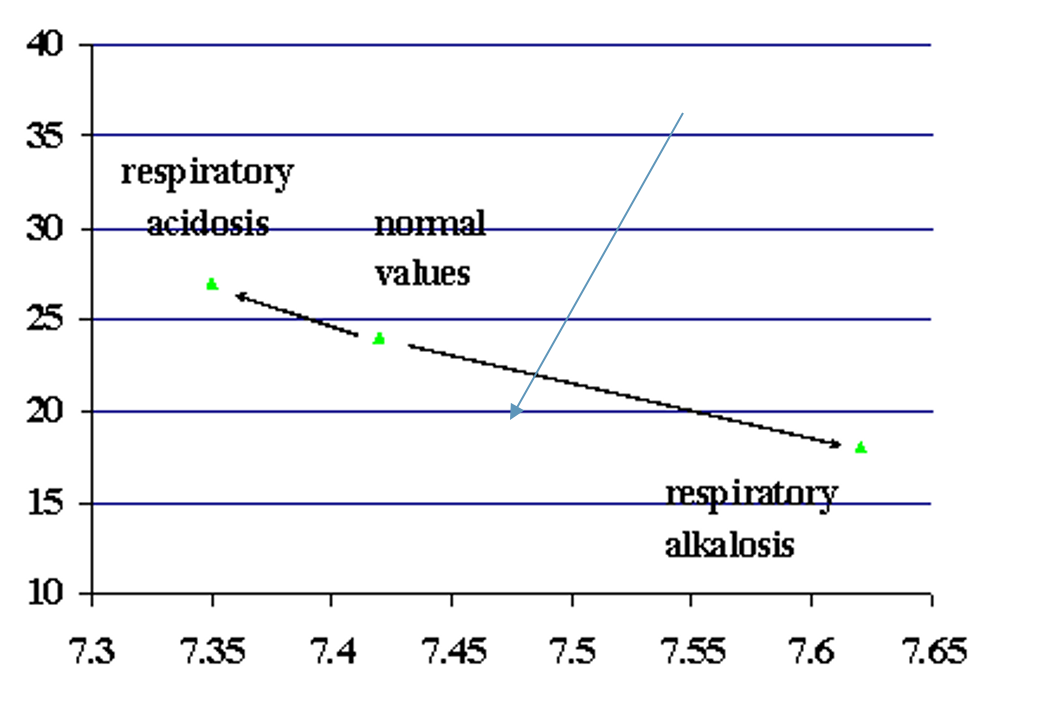

For adults, the normal respiratory rate or cycle of breath (inhale and exhale) ranges between 12 to 16. Many people who are in perfect physical shape could have a range of seven or eight. These are the guidelines. Many well-conditioned people will be lower than 12 and are just fine. For respiratory rates of 18, 19, or 20 and above, these people may have chronic hyperventilation. Our blood chemistry has a certain pH level influenced by the balance between oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood. When you look at this pH level chart in Figure 19, the pH level should be around 7.45.

Figure 19. Blood pH levels as compared to respiratory rates.

When someone hyperventilates, they lose CO2. Those values are represented on the left. As the CO2 decreases, the PH level increases (respiratory alkalosis). If there is an increase in CO2 levels in the blood, it becomes more acidic (respiratory acidosis). This is what is called respiratory alkalosis. We lose carbon dioxide.

When people are hyperventilating, the normal thing to do is breathe into a paper bag. The is because every time you exhale, you put carbon dioxide in the bag. Thus, the next inhalation brings in more CO2. The pH level influences the body's ability to metabolize efficiently. As it goes from one pH extreme to the other, cellular metabolism may not work as efficiently as it should.

- Hyperventilation is not usually recognized unless in its extreme form, but it can be both subtle and chronic.

- This type of breathing is the natural consequence of chest breathing

I always like to look at the respiratory rate of my clients and try to see if their chest or belly is moving. While you are interviewing them, you can do a count. See if you can do it without them knowing, or if you cannot that, ask them to sit and breathe as if they were sleeping. You can tell them that you are looking at their respiratory rate.

- Lose too much CO2...which is crucial to maintaining the right mixture of acid and alkaline, an essential balance for proper cell metabolism (respiratory alkalosis)

- The slightest change in the acid-alkaline balance can cause marked alterations in the rates of chemical reactions in cells.

As I mentioned, if a person is hyperventilating, they may be losing too much CO2, which is really necessary for cellular metabolism. Those changes influence our organ systems as well.

- Hemoglobin will retain O2, thereby reducing the release of O2 into the tissue. This action perpetuates the hyperventilation pattern.

Another thing that happens when we start to hyperventilate is that the hemoglobin, which carries the oxygen and releases it, starts to retain O2. Now, you have a double whammy. You are losing too much CO2, which is affecting the metabolism, and then also you are losing oxygen because the hemoglobin holds onto it and does not release it.

- Conditions that may be related to hyperventilation: fatigue, exhaustion, heart palpitations, rapid pulse, dizziness, and visual disturbances, numbness, tingling in the limbs, SOB, yawning, chest pain, stomach pain, muscle pain, cramps, stiffness, anxiety, insomnia, nightmares, impaired concentration, and memory

There are many conditions related to hyperventilation. We see many of these things like fatigue, exhaustion, palpitations, rapid pulse, and dizziness. We may not think about visual disturbances, numbness, tingling in the limbs, shortness of breath, chest pain, and stomach pain. Remember what I said before about fight or flight mode. The blood gets shunted from our bellies, causing muscular pain, cramps, stiffness, and anxiety. All of these things can impair concentration and memory as a result of the stress response. Again, rapid breathing or inefficient breathing can contribute to this. I should have the reference here, and I apologize. I know it was from an article in JAMA encouraging doctors to be aware to be checking the client's respiratory rates because these are symptoms that often can be attributed to faster respiratory rates.

- Hyperventilation may be compensatory conditions such as….

- Kidney Disease and Diabetes can result in metabolic acidosis

- Hyperventilating may be the body’s attempt to return the acid-alkaline balance to normal.

Most of the time, we want to slow down the respiratory rate. However, if somebody has kidney disease or diabetes, we may want to double-check with the physician to verify that. They may breathe more quickly to bring their blood level to a more normal pH level.

Straw Activity

This is where you need a straw. If you do not have a straw available, you can do pursed-lip breathing. Let's investigate what happens when we slow down our respiratory rates. See if you notice anything. First, sit back with your lower back flush to the back of your chair without using your straw or pursed-lip breathing. I am going to set a timer for 30 seconds. I want you to count how many times you exhale in 30 seconds, and then we will double that number. Try to breathe nice and easy, just like you are sleeping. You are not trying to control it. Now, write that number down and double it. For example, if it was eight, your respiratory rate would be 16 for 1 minute.

Next, I want you to take the straw and breathe in through your nose and out through the straw. When you breathe in, take the straw away to make sure you breathe in through your nose, and then exhale through the straw. Practice that for a moment where you are breathing normally and not trying to take a deeper breath. If you do spontaneously, that is fine. If you are doing pursed-lip breathing, breathe in through your nose and exhale through pursed lips. We are going to do this again for 30 seconds starting now. I want you to count and tell me the times you exhale through the straw or via pursed-lip breathing. Double that number. Did your respiratory rate go down after you did the straw breathing or the pulsed lip breathing? Many of you are saying, "Yes."

What does it mean to slow down our respiratory rate? Sometimes doing pursed-lip breathing can be a little bit challenging for some. For many, the straw makes it really easy. I instruct them to sit there with a straw for one to two minutes. People might start to a little bit dizzy. The reason for this is that the blood chemistry begins to change pretty quickly. If this happens, I tell them to take the straw out of their mouth, stop pursed-lip breathing for a moment, and then go back to doing it. I am willing to bet some of you started to feel a little calmer because that is how quickly breathing can start to influence how we feel. It starts to shift us from that sympathetic branch to parasympathetic really quickly. And, if I had let you do it for two minutes, it would have been even more evident.

I give my clients this experience so they can start to sense and feel things a little bit differently, which will influence how they think and act. This is the language that I learned from Moshe Feldenkrais when I was trained in the Feldenkrais Method. I will talk a little more about that when I show you some pictures in a couple of minutes.

The Mind-Body Circle of Influence

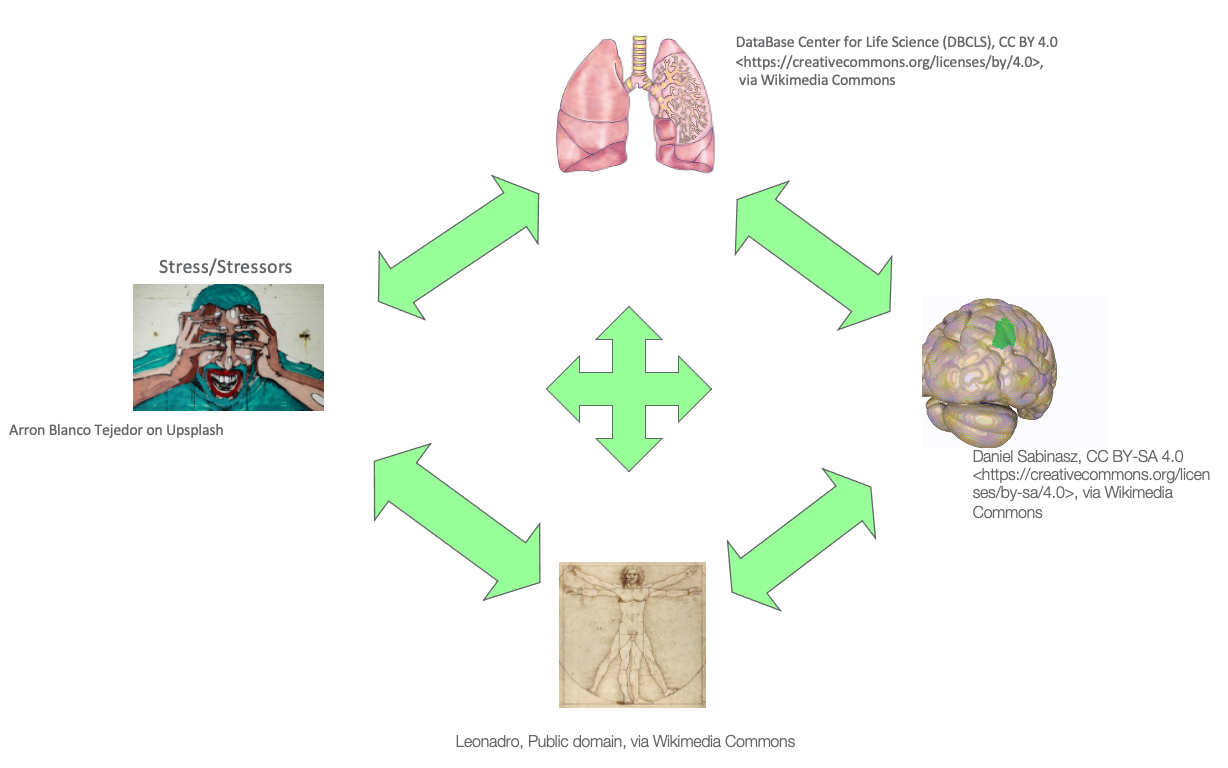

Let's now look at Figure 20.

Figure 20. The Mind-Body Circle of Influence. Click here to enlarge the image.

This is a significant slide. If my client is demonstrating an inefficient breathing pattern (represented by the lungs) and engages the sympathetic response as we have talked about, all of a sudden, they start breathing more rapidly, and their body can get tenser. Their mind then gets a little bit more wound up. And, as they move to a sympathetic response, they release more cortisol. This causes their muscles to get tighter and their minds to get a little more irritated. If we encourage them to use a breathing technique like pursed-lip or straw breathing, this can reduce their stress, quiet their minds, and relax their bodies. As represented in this image, you can see that the lungs, mind, and body are all interrelated. If a client has a breathing issue, it impacts them mentally and physically with the release of cortisol.

As we are trying to create mobility to address body structures (the spine, ribs), you can see that quieting the mind would be important. This will allow the body to start breathing more efficiently. You can also use meditation or activity that really captures someone's attention to quiet the mind.

Body Structures/Treatment

Gentle Exercise

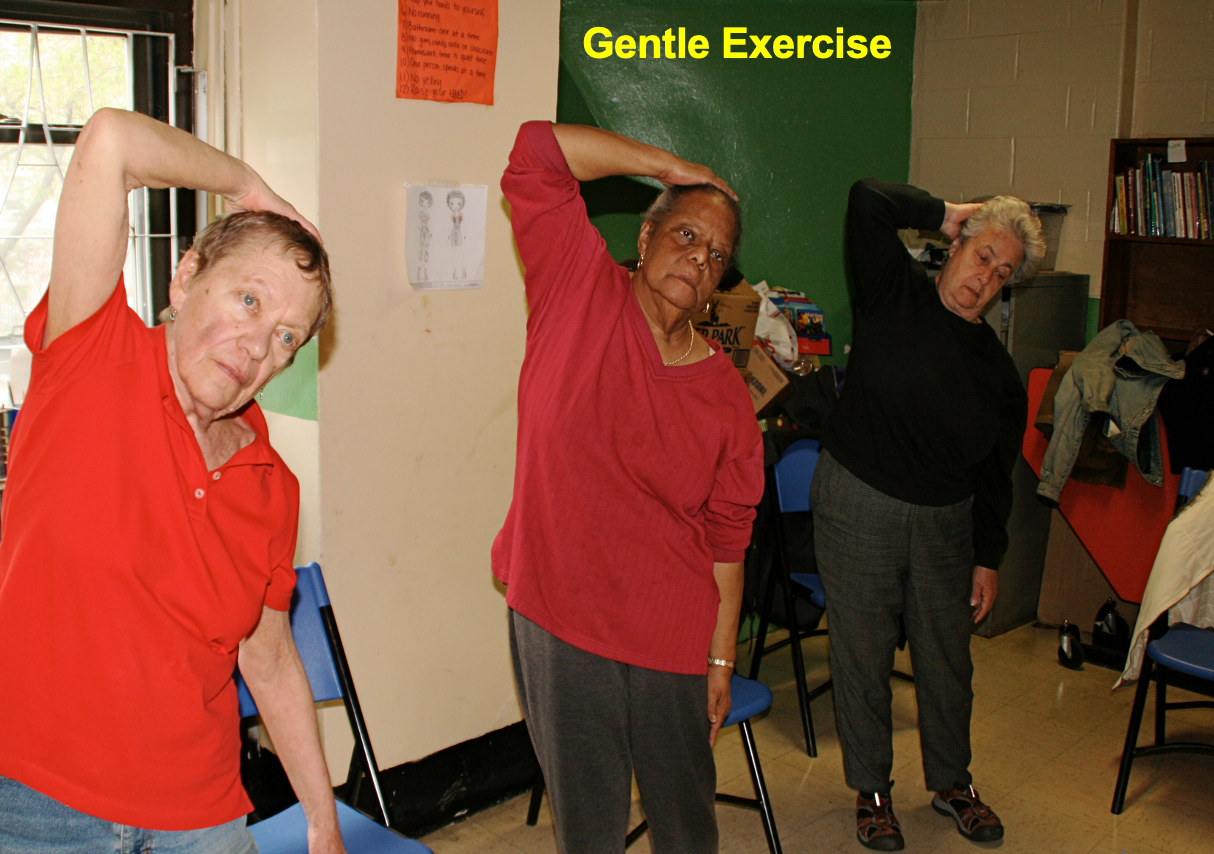

Gentle exercise is great for breath support. In Figure 21, you can see clients putting their arms on top of their heads and leaning to the opposite side in standing. You can also have them do this in sitting.

Figure 21. Women doing gentle stretching while standing.

This exercise opens up the ribs on one side and closes them on the other. Then, you have them switch directions. This works on the mobility of the ribs and the spine.

A clock on a Wall

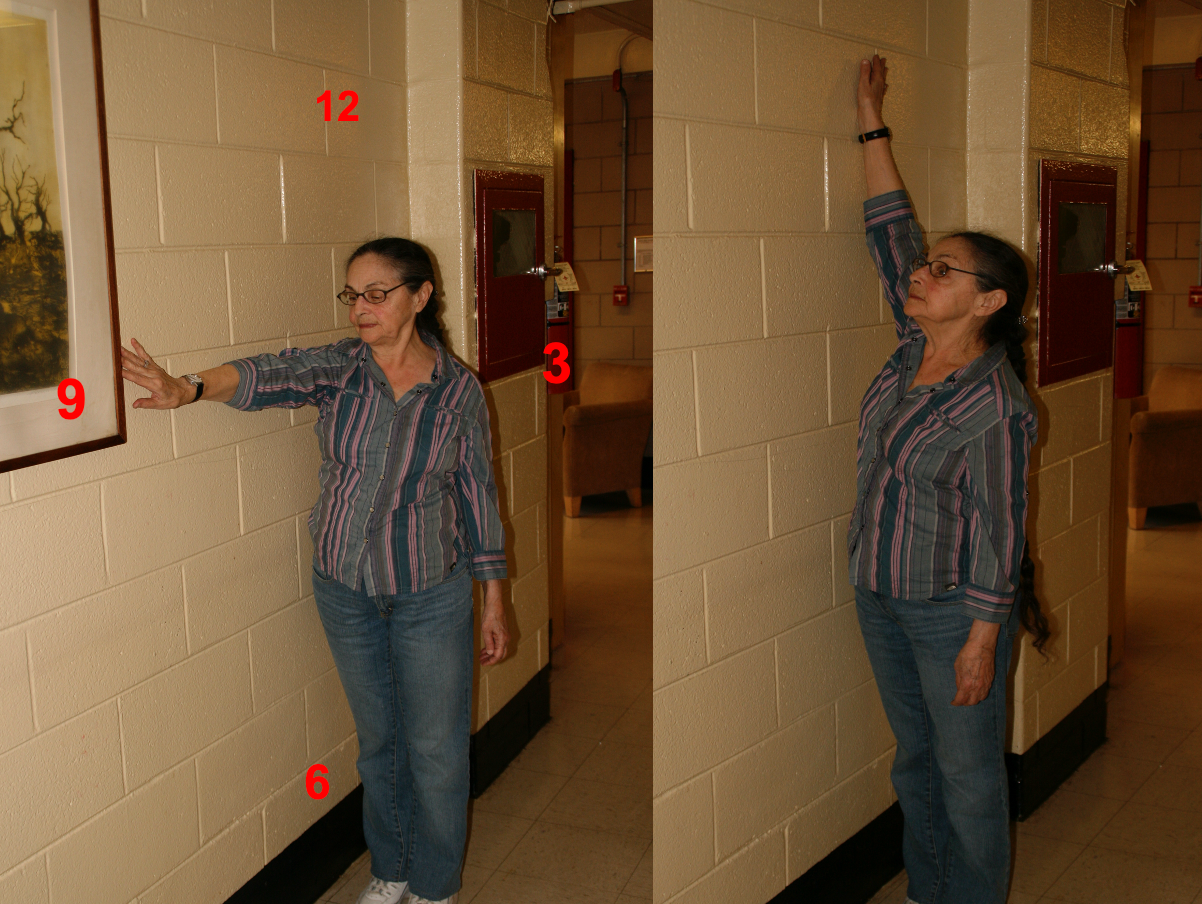

I have instructed the client to imagine a clock on the wall (Figure 22).

Figure 22. A woman doing arm movements mimicking clock hands.

This works both the shoulder and the ribs.

Spinal Rotation

Spinal rotation of any kind moves muscles around the spine like the multifidus (Figure 23).

Figure 23. Two women demonstrate gentle spinal rotation while standing.

A client can do this in standing or sitting. Rotating to the right opens the ribs on that side. This gentle movement creates mobility in the spine, the ribs, and even the pelvis, which we will get to in a moment.

Tai Chi Quan Cloud Hands

I also like to use simple things from Tai Chi, which is slow, controlled movement. I have them coordinate their breath with the movement. Figure 24 shows a preparatory activity.

Figure 24. Several women demonstrating cloud hands in standing with one arm above the other twisting from side to side.

They rotate the pelvis and trunk left and right while moving both arms.

Breath With Activity

I have them breathe when they go one way and then exhale when they go the other way using slow, controlled movement. Figure 25 demonstrates this.

Figure 25. Women breathing while picking up a basket with cleaning supplies.

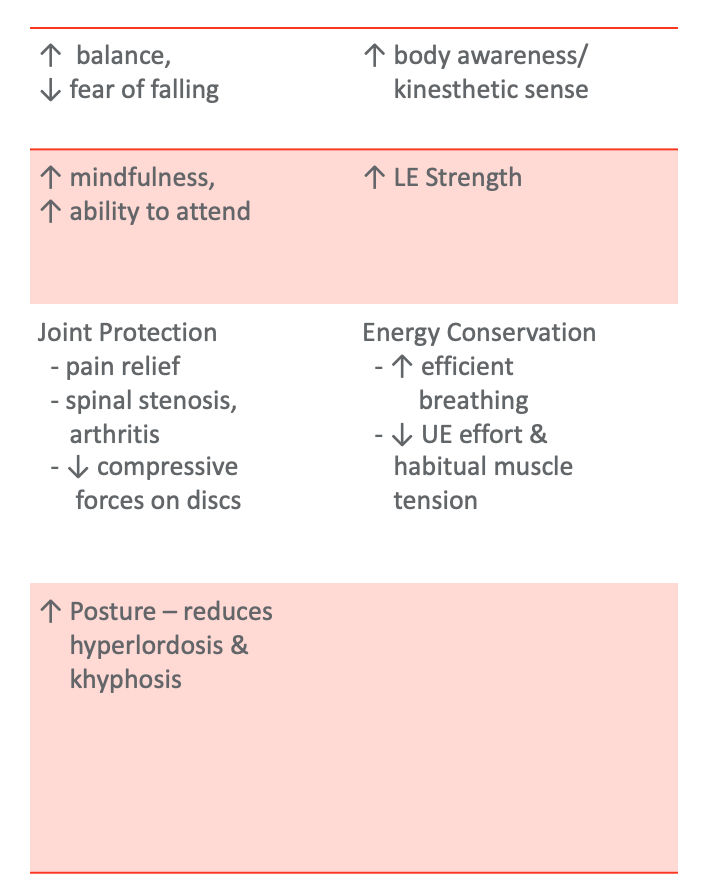

This is teaching them to coordinate breath with movement, which they can then take into an activity. The following chart (Figure 26) shows the clinical and functional benefits of using breathing with activity.

Figure 26. Clinical and functional benefits of using breath with activity. Click here to enlarge the image.

Restorative Yoga

Supported Recline

I use restorative yoga postures a lot in my practice. In this Figure 27, you can see that this client is lying on a folded blanket, opening up the chest and the rib spaces in the front and being closed in the back.

Figure 27. Woman in a restorative yoga pose on a mat with a towel under her chest while supine to open up the chest and ribs.

Expand your chest, and you can feel how the ribs in the front open and the back, how the space closes. This posture in Figure 27 also moves the pelvis a little bit towards an anterior pelvic tilt. And, if she has tight abdominals, the abdominals and pecs are also being gently stretched. This position creates a beautiful stretch of the muscles and stretches the joints to facilitate breath then. I also like to put my hand on the client's belly and say, "While you are in this posture, I want you to allow your breath to move into my hand."

When we focus on that dimensionality of the breath, we can also feel the waist expand. I also like to place my hands on the outside of their waist, as shown in Figure 28.

Figure 28. Placing hands on the client's waist to feel the expansion.

Then, I like to bring the client into sidelying before getting up (Figure 29). In this position, I can place my hand on their back to see if they feel the movement there.

Figure 29. The client is sidelying to the right side with pillows between knees and under her left arm.

The client in these different positions gets to sense and feel the movement of the breath. Then, when she is engaged in activities, I can have her check in and see if she is still noticing her breath. Is there anything restricting her breath?

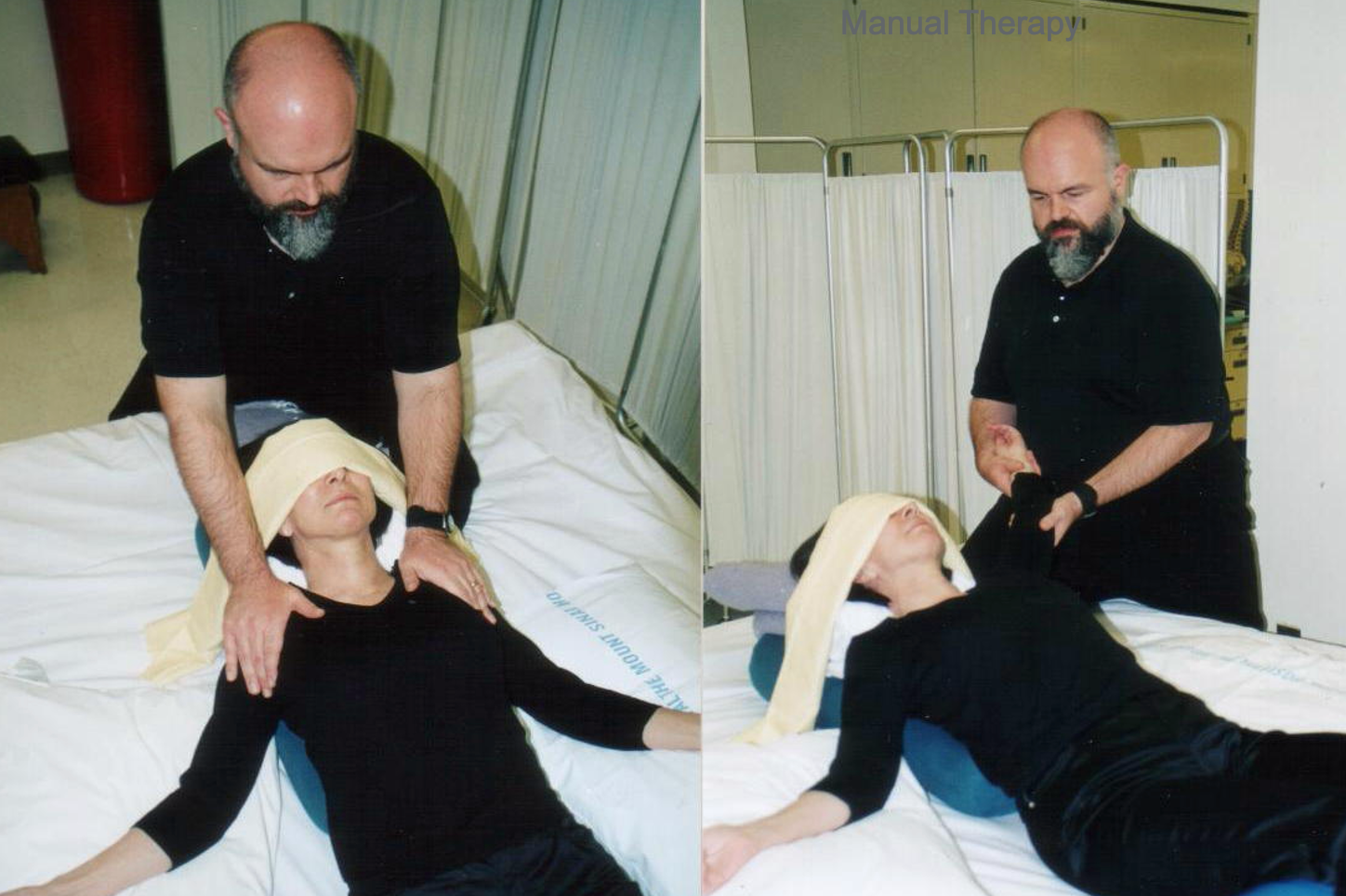

Manual Therapy/Supported Recline

You can do lots of nice manual therapy, as shown in Figure 30. This client is being stretched at the shoulders while in a supported recline position.

Figure 30. A client is receiving manual stretching of her upper extremities while in a supported recline position.

Benefits of Supported Recline

There are many benefits to setting people up after therapy in their beds in a supported recline.

- Benefits

- Functional Benefits:

- Transfers, sit-to-stand

- Forward Reach

- Posture

- Functional Mobility

- Breathing

- Clinical Benefits:

- Neutral/anterior pelvic tilt

- Thoracic Extension

- Ribs – opened anteriorly, closed posteriorly

- Stretching of neck extensors, abdominals, pectoralis muscles, shoulder external rotators

- Relaxation response

Some of the key benefits are listed above. It stretches the ribs, the spine, the neck extensors, the abdominals, and the pecs. The person is relaxed, which engages the relaxation response. Many times people are in a slumped posture when up. I like to use a supported recline position to bring them in the opposite direction (Figure 31).

Figure 31. Client lying in a hospital bed in supported recline position after therapy.

Child's Pose

I also put people in child pose because that is the opposite of supported recline (Figure 32).

Figure 32. Woman in child's pose on a mat laying on a pillow.

The ribs are open in the back and closed in the front, and the pelvis has moved posteriorly. If somebody cannot do it more traditionally, they can do it in sitting (Figure 33).

Figure 33. Woman doing child's pose while seated with head on a table and feel elevated.

The trick is to bring the feet up. If there is no contraindication, get their knees higher than their hips to create a posterior pelvic tilt. I like to have them focused on their breath in this position.

Benefits of Child's Pose

- Functional Benefits:

- Lower body dressing

- Bending

- Seating and positioning

- Balance

- Breathing

- Clinical Benefits:

- Promotes posterior pelvic tilt

- Flexion of hips and knees

- Ribs – opened posteriorly, closed anteriorly

- Reduced compression of lumbar joints

- Stretches erector spinae

- Relaxation response

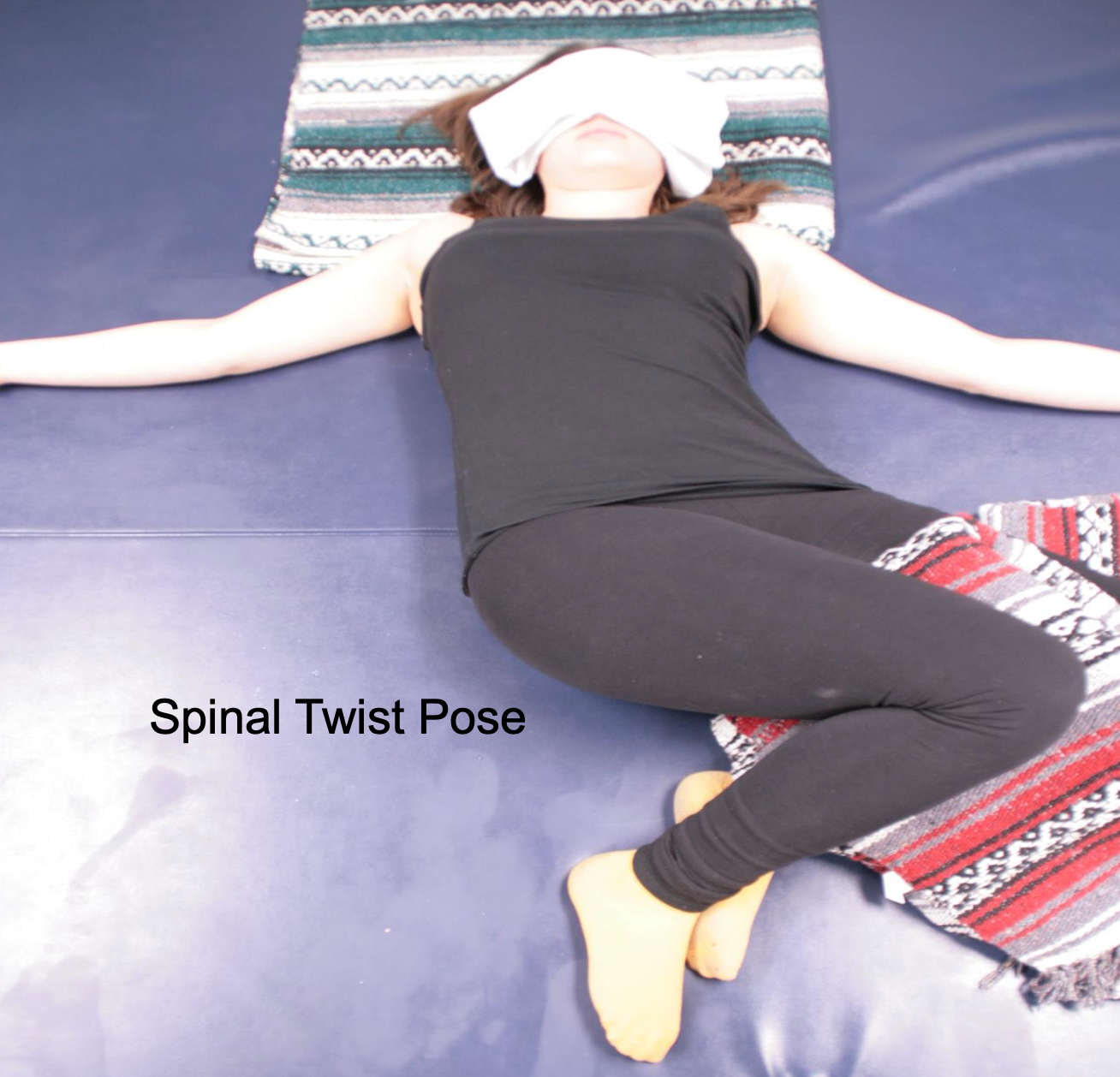

When they are in this position, their breathing is restricted, and it opens up the door to them feeling more movement in the back. We can also place pillows under their ribs on the side to get one side of the ribs to broaden while the other side shortens. Again, we can also put people in a spinal twist that opens on one side, closes on the other, curves the spine, and moves the pelvis. There are numerous possibilities.

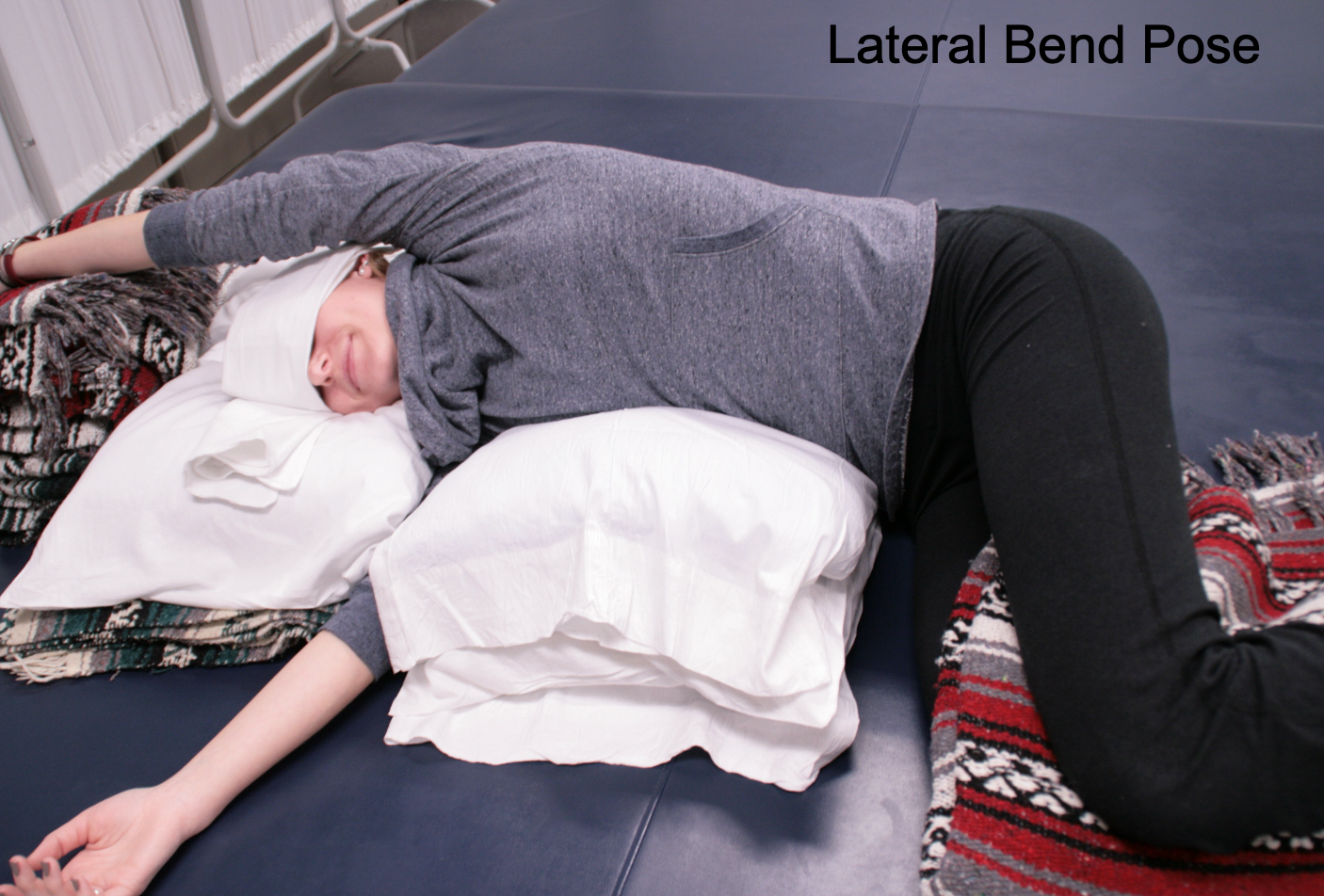

Other Poses

There are so many ways to stretch and position people to get mobility in all these areas. Here are some examples in Figures 34 through 37.

Figure 34. Lateral bend pose with a woman sidelying with arms overhead.

Figure 35. A woman is supine on a mat with her knees bent and rotated to one side while her chest and head are neutral.

Figure 36. Woman in spinal twist pose with the therapist applying gentle pressure to her bent and rotated knees for an increased stretch.

Figure 37. Supine lateral bend with a woman on a mat with legs crossed and shifted to the left of midline.

Benefits of Restorative Yoga

- Low load stretching-long duration

- Promotes the relaxation response

- Facilitates efficient breathing patterns

- Facilitates manual therapy

- Helps manage pain

- Edema management

- Helps improve movement and function

Restorative yoga facilitates efficient breathing and the relaxation response, which I discussed and showed you many options.

Meditation

- Meditation is a particular way of paying attention

- Focus on something specific such as the breath, h a word, image, sound, or body sensation

- Not a passive practice, but rather an active process

- Meditation is universal. It is practiced within many spiritual traditions, but it does not have to be attached to a belief system

- Occupations can be meditative

Meditation also helps the person to shift towards the parasympathetic aspect of the autonomic nervous system. This promotes more efficient breathing.

Pelvic Clock in Sitting

- Clinical Benefits:

- Mobilizes joints and soft tissue of the pelvis, spine, ribs, and head

- Functional Benefits:

- Balance

- Weight shifting

- Transfers

- Forward and lateral reach

- Lower body dressing

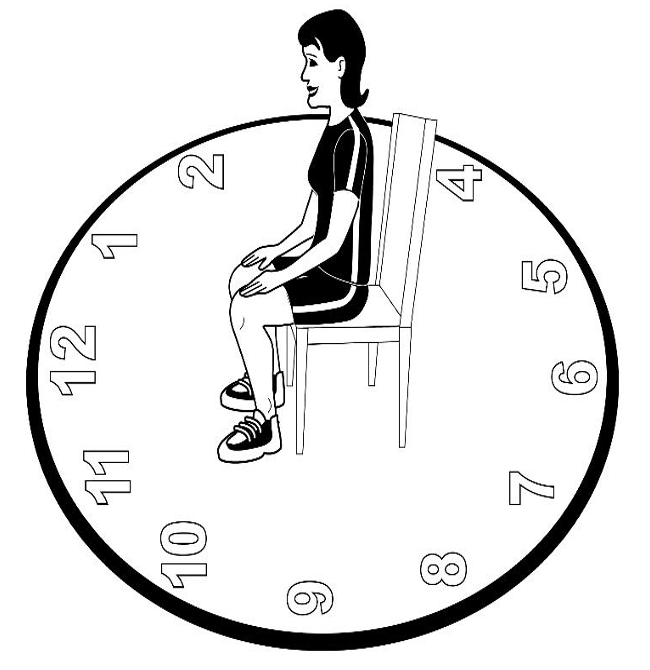

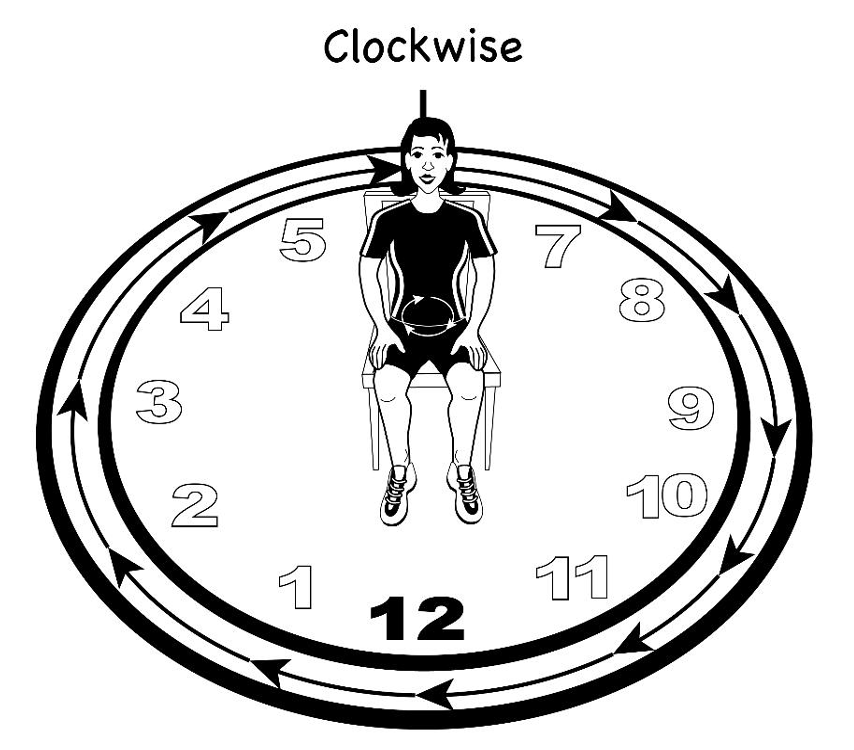

I use the pelvic clock a lot in treatment, as shown in Figure 38.

Figure 38. Drawing of a pelvic clock with a person facing 12 o'clock.

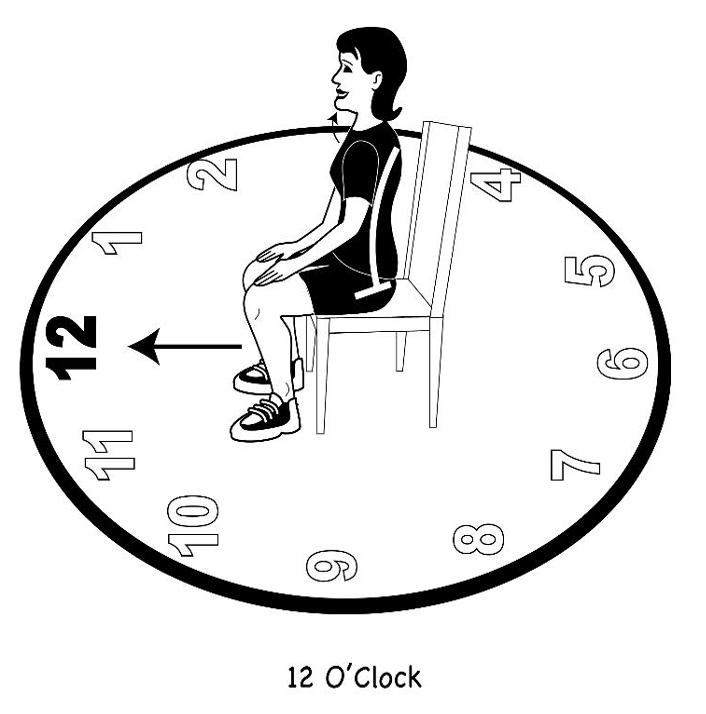

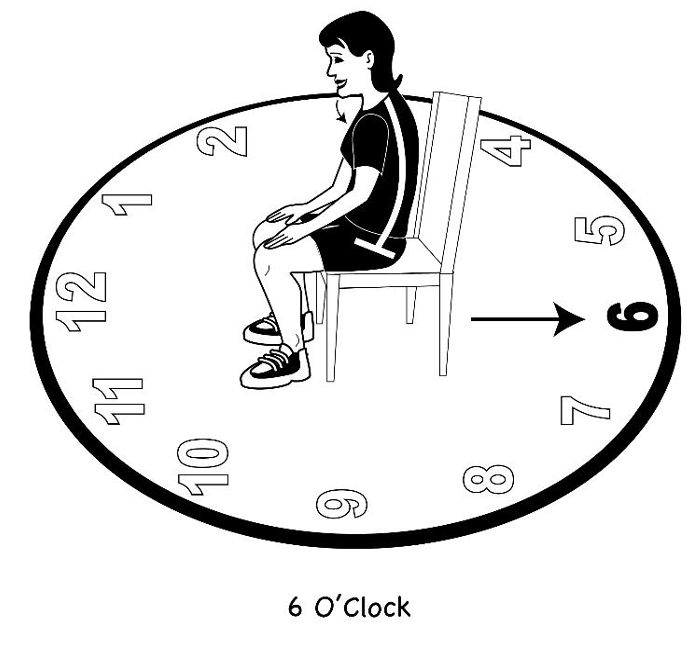

This is where a person sits in a chair and imagines that they are on a clock. First, I have them toggle back and forth from six o'clock to 12 o'clock. See Figures 39 and 40.

Figure 39. Drawing of a pelvic clock with person rotating the pelvis toward 12 o'clock creating an anterior pelvic tilt.

Figure 40. Drawing of a pelvic clock with person rotating the pelvis toward 6 o'clock creating a posterior pelvic tilt.

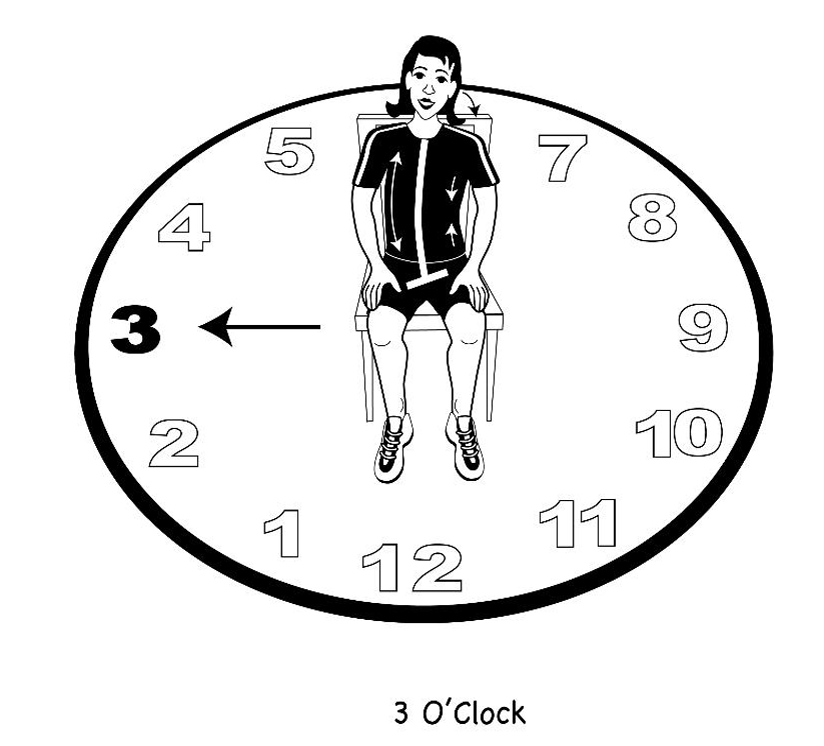

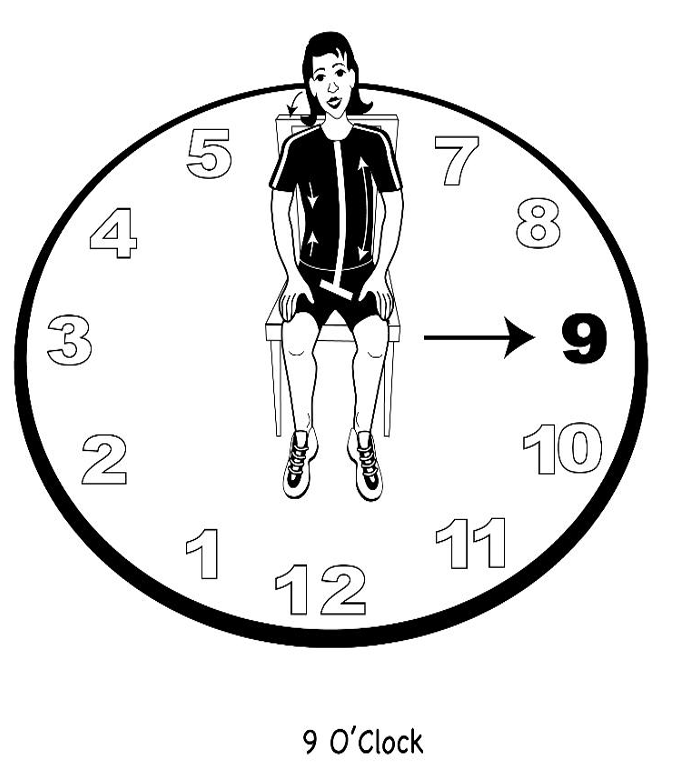

This is going from an anterior pelvic tilt to a posterior pelvic tilt. This helps to open up the rib cage. I have them do this gently. Then, I have them go from side to side to do lateral weight shifts (Figures 41 and 42).

Figure 41. Drawing of a pelvic clock with a person performing a right lateral pelvic shift toward 3 o'clock.

Figure 42. Drawing of a pelvic clock with a person performing a left lateral pelvic shift toward 9 o'clock.

Again, I want them to notice how this influences their ribs. Their head and neck are free to move while the pelvis is moving. All of this is a gentle, easy movement, mobilizing all these different parts of the body that we have identified that are important to efficient breathing. Next, I will have them go around the pelvic clock in a circle, slowly in both directions, as seen in Figure 43. This is both clockwise and counterclockwise.

Figure 43. Drawing of a pelvic clock with a person rotating their pelvis clockwise.

Energy Conservation Techniques, Work Simplification, and Ergonomics

Let's not forget many of the things we learned in OT school, energy conservation techniques, work simplification, and ergonomics. These are all vital pieces that we need to include in our treatment plans.