Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Mental Health of Adolescents: Psychosocial Occupational Therapy for Adolescent Populations, presented by William Lambert, MS, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the etiology and psychosocial stressors that affect the mental health of adolescents.

- After this course, participants will be able to ▪Identify presenting problems, symptoms, and diagnoses common to this population.

- After this course, participants will be able to list effective intervention strategies for adolescents experiencing mental health-based issues.

Introduction

Adolescents are my favorite treatment population. Today, we will be talking about all the different mental health issues of adolescents.

Stereotypes

Let's begin by talking about stereotypes. There are pervasive stereotypes about teenagers that can muddy the water when looking at mental health. For example, we typically think of adolescents as moody, dramatic, and sometimes oppositional/defiant. We also think of them as withdrawn and isolated from their families. These perceptions are because they are individuating.

Any of these characteristics can be symptoms of a mental health problem. For example, withdrawal is part of depression. Histrionics, drama, and mood swings are typical in bipolar disorder or other mood disorders. When we see these different things, we may start to get worried. For instance, if they are oppositional and defiant, are they developing a conduct disorder? We have to put these stereotypes aside and look at an adolescent as a whole person to see what is happening.

Etiology

- As with other age groups, a number of factors can contribute to developing mental health issues.

- Generally, it is believed to be a combination of genetic and psychosocial factors.

- Equality of life issues

- Adolescents from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds face different role expectations.

- Self-efficacy

- Bullying and school violence

As with other age groups, a number of factors can contribute to developing mental health issues. Across the board (children and adults), mental health issues are generally believed to be a combination of genetic and psychosocial factors. If we are programmed for depression because of family history and suffer some hardship, we may be more likely to develop depression than someone whose family does not have the genes for depression.

Equality of life issues means that not everybody has the same ability to access healthcare for various reasons. Sometimes, it is an availability issue in a community or a lack of insurance. A person may not be able to go out of their area to see a mental health expert. Socioeconomic status plays an issue here as well. More educated people may be aware of different illnesses and problems. They also may take their children to well-baby visits more often. As such, they will catch things much faster than families that are not aware of those issues. These are just a few of the equality of life issues that exist.

Adolescents from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds also face different role expectations. The ability of adolescents to have self-efficacy and a belief that they can handle whatever comes at them is a strength and protective factor. We will talk more about that in a minute. Conversely, if you lack protective factors, then you are going to be more at risk.

Lastly, bullying and school violence affect the mental health of adolescents. School violence, such as mass shootings, happens all too often in our country.

- Just as there are risk factors for mental illness, there are also strengths that can be protective barriers.

- Courage, hope, optimism, interpersonal skills, and perseverance

- A strong family system also supports adolescent resiliency.

As I said a moment ago, there are also strengths and protective barriers in addition to risk factors. These strengths are courage, hope, optimism, interpersonal skills, and perseverance. A strong family system also supports adolescent resiliency. It does not necessarily have to be a specific person in a family system, but it needs to be someone the adolescent confides in and trusts.

Special Considerations: COVID-19 Pandemic

- Social Isolation

- Lack of Access to Services

- Exacerbated Symptoms

COVID-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on the mental health of people everywhere. There is plenty of research about how it creates mental health issues for people due to social isolation, lack of access to services, and people just not being seen. And, if a person already has a mental health issue, their symptoms are exacerbated by the necessity of masking, social isolation, and social distancing. I never realized what a social person I am until I was isolated. Taking away social interaction contributes to mental health issues for everyone.

- Effects of Social Isolation on Mental Health

- Increased stress and feelings of loneliness

- More vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and suicide

- Increased risk of domestic abuse and violence

- less likely to report this abuse while in the home

- Increased cyber-bullying due to rise in social media/screen-time

Social isolation causes stress and feelings of loneliness, and people are more vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and suicide. There is also an increased risk of domestic abuse and violence. This is "familiarity breeds contempt" taken to the nth degree. When a child is in an abusive home, at least in school, there are other people to observe the child. When people are working remotely, and everyone is at home, this prevents this security measure. Cyberbullying has been on the rise, especially during the pandemic, due to more social media screen-time.

Disorders/Diagnoses

- Vary according to treatment setting

- Inpatient: depression, bipolar disorder, thought disorders such as schizophrenia. Symptoms may include suicidal ideation, threatening physical violence, generally a threat to self or others

- Conduct disorder, ADHD, attachment disorders, any of the adult diagnoses such as OCD or PTSD

Let's take a few minutes to look at diagnoses. They vary according to treatment settings. I worked in an inpatient, locked facility with severe and more challenging disorders. These are disorders like depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. One of the things that usually leads to an inpatient hospitalization is suicidal ideation. We will talk more about suicide later. Other factors leading to an inpatient setting are threatening physical violence, being a threat to self or others, conduct disorders, ADHD, attachment disorders, and any adult diagnoses such as OCD or PTSD.

Diagnoses

- Outpatient: Adjustment disorders, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, ODD, and PTSD

- Disorders can be co-occurring with other problems such as substance abuse or eating disorders.

- Adolescents with diagnoses common to inpatient settings will be seen outpatient once symptoms have been stabilized or did not warrant hospitalization.

In outpatient, we are likely to see people in recovery as opposed to in the throes of a crisis. These diagnoses include adjustment, depressive, and anxiety disorders. You may or may not see these in an inpatient setting but rather in community-based settings. These disorders can also co-occur with other problems such as substance abuse or eating disorders. After adolescents are seen in inpatient, they move to outpatient once they have stabilized and no longer warrant hospitalization.

New to the DSM-5

- Revised classification of Bipolar and Depressive Disorders

- A new chapter titled “Disruptive, Impulse-Control and Conduct Disorder” has been added that includes Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder, and Intermittent Explosive Disorder

- A new chapter titled “Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders” has been added that provides for Acute Stress Disorder, Adjustment Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Reactive Attachment Disorder

There are some new chapters in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The DSM-5 is the most accepted manual for diagnosing mental health disorders in the United States and around the world. If you work in mental health, and even if you do not, you need access to this manual for all of the criteria for the different disorders. It has been rearranged from previous editions of the DSM-5.

Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorder have their own chapter. There is also a whole new chapter entitled, Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders. This is important because trauma-informed care is a new way to treat people with mental health issues.

Presenting Problems

- Treatment is more likely to be rehabilitative as opposed to habilitative.

- Internalizing behaviors and symptoms include diagnoses such as depression. May present as the “quiet or good kids” and not identified as readily as having mental health issues.

- Externalizing behaviors present in “the problem kid” and leads to more MH referrals.

- Professionals should NOT overlook the adolescents who are quiet or nonacting out.

The treatment with adolescents is more likely to be rehabilitative as opposed to habilitative. What I mean by habilitative is that children may have never learned specific skills. We are habilitating and teaching them skills that they do not have. Adolescent treatment is more likely to be rehabilitative because, instead of teaching them skills, we are trying to get them back to where they were before finishing their goals. Other things to think about are things like internalizing versus externalizing behaviors. The quiet or good kids are much more likely to fly under the radar and internalize depression. Externalizing behaviors may present in those seen as "problem kids." These external behaviors lead to more referrals because of oppositional and defiant behavior. We should not overlook the adolescents who are quiet and not acting out. A behavior change is one of the first signals of a mental health issue in an adolescent.

- Changes in behavior

- Changes in affect or mood

- Changes in relationships

- Decompensating in general

- Presenting a danger to self or others

- Comorbid issues, e.g., physical problems

We need to look for changes in behavior, their affect or mood, and changes in relationships. If they were previously very gregarious and now withdrawn and not seeing their friends, this may be an issue. Decompensating, in general, is another signal. Decompensating is the regression from a high well functioning status to a lower or less well functioning level. For example, your depression may be in control, but if you start to be sad and hedonic, which means you do not find pleasure in things that you usually do, this would be decompensating. Another problem is presenting as a danger to self or others.

We also want to look at comorbid issues like physical problems. With mental health, we always need to look at what else is going on with the person. I always tell my students, "No one just has one thing going on at a time." Let's use the example of someone who has had a hip fracture and replacement. They can be anxious about going out. They could have an "anxiety disorder" that could be part of the fall itself, or maybe they were always an anxious person. Indeed, people can become depressed over medical issues and not have the ability to do things they used to do. And, different disorders also limit us in lots of ways, such as diabetes. Thus, many other things can contribute to a mental health issue outside the scope of what we usually expect.

Suicide

Next, let's look at suicide and start with some frightening statistics.

Statistics

- The second leading cause of death for people aged 10-14 years of age (CDC, 2018)

- The second leading cause of death for people aged 15-24 years of age (CDC, 2018)

- 13.6% of high school students and 2.4% of college students have written a plan (CDC, 2015)

- 7% of high school students have attempted suicide (CDC, 2017)

These statistics have not budged much over time. Suicide has moved from the third leading cause of death for adolescents to second place. Most frightening is this emergence of the second leading cause of death for people ages 10 to 14 years of age, according to the CDC. Younger people are attempting suicide. And, it is the second leading cause of death for people ages 15 to 24 years of age. This is second to things like motor vehicle accidents or other kinds of accidents. We are also talking about the college years in this group, which could probably be its own discussion. Changes that occur with going to college can be exacerbating factors for developing a mental illness and decompensation due to the loss of supports at home. They may have to find a new therapist or school counselor and establish unique rapport.

The following statistic is 13.6% of high school students, 2.4 college students have written a plan about suicide, and 7% of high school students have attempted suicide. This is a real crisis in our country.

Leading Causes of Death by Age Group

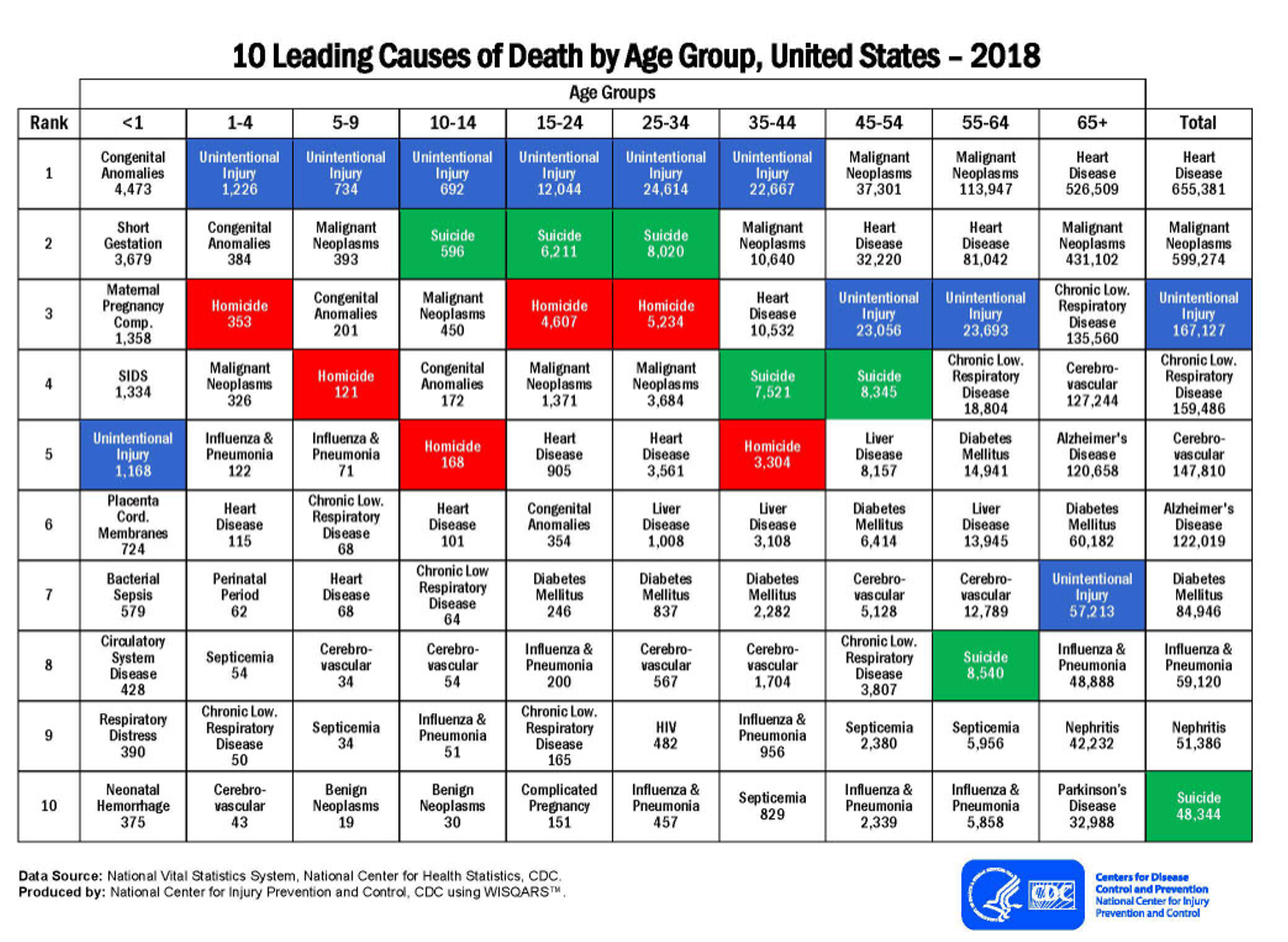

I will not go over this, but this chart shows the leading causes of death of young people (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Graph of the ten leading causes of death by age group in the US (CDC, 2018). Click to enlarge the image.

Risk Factors

- Depression/other mental health disorders

- Prior suicide attempt

- Family history

- Family violence, physical, or sexual abuse

- Firearms in the home (used in half of all suicides)

- Incarceration

- Exposure to the suicidal behavior of others

There are many risk factors for suicide, including depression or other mental health disorders, a prior suicide attempt, family history, family violence, physical or sexual abuse, firearms in the home, incarceration, and exposure to the suicidal behavior of others. One important note is the socio-cultural nature of firearms in the house. When I worked in an adolescent inpatient unit, I remember in lots of team treatment meetings, part of discharge planning was to get the family to remove firearms from the home as they are often used in suicides, especially males. Often, they would refuse or say that they would lock them up. We would reply, "That's not good enough." It was an argument that surprised me. Incarceration is another risk factor. For example, an adolescent is arrested for something stupid. This can create a loss of faith and/or the fear of disappointing parents. Depending on the adolescent's temperament, this could be a suicide risk factor.

Additional Risk Factors

- Co-occurring mental and substance abuse disorders

- Parental psychopathology

- Hopelessness

- Impulsive/aggressive tendencies

- Life stressors such as interpersonal losses and legal or disciplinary problems

Some additional risk factors include co-occurring mental health and substance abuse disorders, parental psychopathology, and hopelessness. Hopelessness in my research has shown to be the number one risk factor for suicide. This makes sense when you think about it. Impulsive and aggressive tendencies and life stressors, such as interpersonal problems and losses or disciplinary problems, as I was just alluding to, are also risk factors. I have lost patients to suicide. I also have friends that have lost a child to suicide. I mention this only to emphasize the importance of prevention.

Interventions

- ALL suicidal verbalizations or gestures need to be taken seriously.

- Ideation, plan, and intent

- Interventions:

- Have individual seek help from doctor or ER

- Dial 911

- Eliminate access to firearms, medications

- Consider ideation, plan, and intent

- Take personal responsibility to keep the person safe

- Never leave the person alone

All suicidal verbalizations or gestures need to be taken seriously. Even in inpatient settings, I have heard people say, "They are doing that for attention." It is a crummy way to get attention, and I am sure that plenty of people might have been doing it for attention but instead died. Anytime someone says anything remotely suicidal, you have to take it seriously.

The other things you look at are ideation, plan, and intent. Ideation is having suicidal thoughts, and the plan is how you would do it. The intent is how seriously you are planning to carry this out. With each of these in place, it ratchets up the lethality and probability of a suicide attempt.

The most critical intervention is never to leave the person alone. You stay with them and ask them to seek help from a doctor or take them to the ER if they are willing to go. Now that everybody has a phone with them, it is much easier to dial 911 with the person there. Again, eliminate access to firearms and medications. It is essential to consider ideation, planning, and intent. It is your responsibility to keep that person safe. Here is an example. "Bill, I agree to go to the hospital. I just need to go to the bathroom for just a minute. I'll be right out." How loaded is the bathroom with things that could be lethal in terms of medications, razor blades, etc.? I have found in my work, especially in inpatient settings, that if somebody intends to harm themselves, they will use whatever is available to them. You do not want to leave that person alone for even one minute.

Resources

- National Suicide Prevention Hotline

- 1-800-273-8255

- 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress

- Crisis Text Line

- Text HOME to 741741

- 24/7, free and confidential support from trained Crisis Counselors

These are some resources for you. These are available 24/7.

Occupational Therapy Interventions

- Patient and family education

- Management of relapse and disappointment with a plan in place--- a contract for safety

- Dealing with hopelessness

- Reinforcing remaining in treatment

- Medication compliance

- Family involvement

- Identifying support groups and resources

- Strategies to handle setbacks in recovery

Let's talk a moment about OT intervention. What can we do for adolescents with mental health issues or prevent mental health issues from developing? Patient and family education is essential. In my outpatient practice, I had a young man who had reactive attachment disorder (RAD). Some of the symptoms he displayed were stealing, lying, and hoarding. I will not go into a whole history of why people develop a reactive attachment disorder. Still, it was essential to educate the family that the boy was not doing it to be oppositional and spite them. Instead, his background and diagnosis were causing these problems. I had pamphlets that I gave families so that they understood this. I also conducted family meetings with the patient and family to explain the reasons for the behavior. Of course, we have to try to mold people to fit into society and family appropriately. A contract for safety can be used when people leave the hospital and feel suicidal. They pledge to contact a particular person. It sounds simple, but they have promised not to harm themselves. When someone is in crisis and has an actual plan in place, a tangible contract that they can see can be beneficial.

Other interventions include dealing with hopelessness, remaining in treatment, medication compliance, and keeping the family involved. You can help the adolescent and family identify support groups, resources, and strategies to handle setbacks in recovery. We do not always think to prepare people for the highs and lows of an illness. Mental and physical health are not linear. When there is a setback of some sort, the client needs a strategy for dealing with that setback.

Self-Mutilation

- “Deliberate destruction or alteration of one’s body tissue without conscious suicidal intent” (Favassa, 1996)

- Also known as self-injurious behavior, parasuicide, self-wounding, and “cutting”

- A maladaptive coping skill for dealing with uncomfortable feelings

- OT: Self-management (stress, anger, and emotional management), alternative coping strategies (ice, etc.), CBT, DBT, and sensory approaches

- Problem-solving, tactile stimulation, massage, self-soothing, communications skills

I frequently saw self-mutilation in the adolescent population. Self-mutilation is deliberate destruction or alteration of one's body tissue without conscious suicidal intent. If you are interested in learning more about self-mutilation, Favassa (1996) is a leading expert in this area. Self-mutilation is also known as self-injurious behavior, parasuicide, self-wounding, and cutting. Someone engaging in self-injurious behavior is a "cutter." I think this is horrible. Let's not reduce a person to that.

The main thing about self-mutilation is that it is a maladaptive coping skill for dealing with uncomfortable feelings. Once I asked an adolescent why she cut, and she said, "When I see the blood flow, I feel better." Naturally, it is our job to teach coping skills that are not harmful to one's body. However, I have read that there is a certain euphoria that comes with cutting. For self-management skills, how do we help our clients to handle and cope with those uncomfortable feelings better? We can teach self-management strategies for stress, anger, emotions. Two alternative coping strategies for self-mutilation are holding an ice cube on the skin, which presents a burning feeling, or snapping a rubber band. Both are not going to cause permanent damage. The key is that these are temporary alternative coping strategies.

We want them not to engage in self-harm. Then we want them to develop coping strategies through cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, and sensory approaches. This is perfect for occupational therapy. We naturally can also work on problem-solving, tactile stimulation, massage, self-soothing, communication skills, and things like that.

Helpful Concepts for Treating Adolescents

Structure and Consistency

- Adolescence is a period of transition, and sometimes instability

- Can be lacking in the home environment

- Establishes trust

Adolescence, as we all know, is a period of transition and sometimes instability. Structure and consistency help maintain adolescents' mental health and can be lacking in a home environment. When there is no structure and consistency at home, we can provide this as a therapist using therapeutic use of self and becoming a reliable person. They must have one person out there that they can go to that will listen to them. This is invaluable. We also need to establish trust through structure and consistency. We do what we say we will do, and if it does not, you discuss it.

Limit Setting

- Teens are more likely to follow rules and adhere to expectations if they are involved in their creation.

- Providing positive reinforcement instead of negative consequences is helpful.

Setting limits with adolescents is another helpful concept. Two important things to remember here are that teens are more likely to follow rules and adhere to expectations if they are involved in creating the rules. Providing positive reinforcement instead of negative consequences is also helpful. I use this when working with children. I try to catch them doing something good. People like to hear positive things. Let's say you want the curfew for your adolescent to be nine o'clock, and they want it to be eleven o'clock. If you compromise on ten, they are much more likely to be home by ten than if you just say, "It's nine, and that's it." They are becoming young adults, which is a good way for them to understand how to settle problems and differences.

Again, providing positive reinforcement instead of negative consequences is helpful. It does not need to be items. I think buying things for kids as rewards is not as good as positive statements or gestures. For example, "I appreciate that you're sticking to your curfew. Let's go out and do something fun."

Therapeutic Use of Self in Relationship

- Be authentic and genuine

- A confidant but not a friend

- A trustworthy adult

In terms of that therapeutic use of self in the relationship, it is critical to be authentic and genuine. A teenager can spot a phony or someone who is not interested a mile away. Treating adolescents may not be your niche. We should all find our niche so that we can truly be engaged. Remember that you are a confidant and not a friend, as there is a difference. You need to be a trustworthy adult.

Avoiding Power Struggles

- Adolescents have the cognitive skills to negotiate and manipulate adults

- Allowing adolescents to make decisions and have control meets their need to express autonomy and act independently

- Providing choices is effective and gives the adolescent a sense of control and the ability to express autonomy acceptably

This follows the conversation that we just had about limit-setting and so on. Adolescents have the cognitive skills to negotiate, as I mentioned, but they also can manipulate. Allowing adolescents to make decisions and have control helps them meet their need to express autonomy and act independently. This is good because we want them to be well-rounded, competent adults. Providing choices is an effective way to give adolescents a sense of control and express autonomy acceptably. Let's use the example of cutting the grass. If I say, "I expect you to cut the lawn today. Would you like to do it this morning while it's a bit cooler or later this afternoon? This is effective as they feel in control and are not being told what to do. I do not think any of us like that. If someone tells me what to do, I think, "We'll see about that." And I do not have an oppositional defiant disorder. Nobody likes a mandate, and people want to feel that they have some control.

Creating a Therapeutic Environment

- Milieu therapy as it was intended

- Family room type atmosphere

- Humanizing the environment through lighting, furnishings, atmosphere

It is also vital to create a therapeutic environment. My OT room, both in inpatient and private practice, was like a family room. I call it milieu therapy. All psych units say that they use milieu therapy. If you have ever been in an inpatient setting, it is brightly lit with few comfortable places to sit. There is not a lot on the walls for safety reasons. In the OT room, I used incandescent lights and had art on the walls. The change in the atmosphere put people at ease. It also provided things to talk about based on the items in the room. We can humanize the treating environment in many ways by changing the lighting and furnishings.

Adolescent Settings & Programs

- Traditional Settings: Hospitals, psychiatric units, behavioral health facilities, partial hospitalization programs, residential treatment centers, outpatient therapy

- School-Based Programs

- Home/Community

- Private Practice

I have touched on traditional adolescent treatment settings: hospitals, psychiatric units, and behavioral health facilities. The first two are the most restrictive environments. Behavioral health facilities often contain both an inpatient and outpatient portion. Partial hospitalization, or day programs, are entirely outpatient. Residential treatment centers are where the adolescents stay for treatment. Outpatient therapy is the least restrictive environment. Clients in outpatient are going from a very acute setting to living in the community. This changes up your ability to do different kinds of therapy and in different environments. There were probably very few adolescents that I wanted to see while they were in crisis and suicidal. However, when I had an outpatient office, I saw people alone at night with complete comfort.

Right now, what we see in Pennsylvania and some of the other Northeastern states is more of a focus on school-based mental health programs for adolescents. Most notably are anti-suicide and anti-bullying programs in the schools. We finally recognize these issues. Many of these programs include an anonymous number you can call. There is protection for people that are identifying what is going on. This has become very successful. I certainly hope we continue to see that.

In terms of home and community, adolescents have so many needs, especially for the age group of 15 to 24-year-olds. For instance, there are many things we can do on college campuses to address mental health needs or adjustment needs. This includes dealing with the pandemic, transitioning out of your home, how to set up your life independently, etc. It does not have to be a severe problem but serious that they seek help. I have had OT and grad students that stated they needed help. Some of the areas include finding an apartment, open a checking account, and budgeting. Listening and taking an excellent occupational profile will help determine the goals.

Evaluation

- Magazine Picture Collage

- Kinetic Self Image Assessment

- Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS)

- Adolescent and Adult Sensory Profile

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

- Youth Self-Report

- Interest Checklists

There are many evaluations you could use. I like the Magazine Picture Collage. I used this in assessment groups with adolescents all the time, roughly based on Carol Learner's Magazine Picture Collage. I would ask them to pick a color of paper, a glue stick, scissors, and a magazine. They cut out words and pictures that represent them. This was a great first look at what made them tick, what they valued, what they found necessary, and how they saw themselves. I found this to be an excellent initial assessment along with the Kinetic Self-Image Assessment, which I tended to use more with children or younger adolescents. They draw a picture of themselves doing something, and then they describe that to give you some cues about their normal development, what they like to do, and with whom. Both of these assessments have a projective quality. I love the Adolescent and Adult Sensory Profile. The Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS), COPM, Youth Self-Report, and Interest Checklists are others. I have also created and copyrighted an Interest Checklist for adolescents because the other ones were outdated. One of the things we need to look at in all areas of treatment, mental health, and otherwise, is how old the assessments are and if they still provide the information we need for people currently living in the 21st century.

Intervention

- Client-Based

- Client-Driven

- Family Involvement

Adolescents love doing---Perfect for Occupational Therapy

Intervention, client-based, and client-driven family involvement are all critical in intervention. Adolescents love doing things I found in my practice. It was not hard to get them to occupational therapy. Something I wanted to mention is the use of scissors. There is no reason not to use scissors in a controlled environment where you have done a sharps count. I do not give them giant kitchen sheers. I always used the smaller versions, and I counted the amount of "sharps" at the beginning and end of the group. Trust is so important. They would say, "Ooh, aren't you afraid of what we'll do with the scissors? I would respond, "No, I'm not. If you can't handle scissors in the OT room in the hospital, I'm not sure how you're going to do outside the hospital." You have to have a sense of humor and a way of developing therapeutic rapport. You can joke around with them and use humor.

Here are things that I found to be successful.

- Arts and crafts

- Real Life Occupations, especially in community-based occupational therapy---finding employment, cooking, and other actual daily occupations

- Must be relevant to the individual/client-based

- Board Games: “Life,” “Talk it Out”

- 104 Activities That Build: Self-Esteem, Teamwork, Communication, Anger Management, Self Discovery, and Coping Skills

- SEALS Series (Self-Esteem and Life Skills) can be used for topical, focus, and psychoeducational groups or individual sessions

For the most part, adolescents love arts and crafts like tile mosaics and wood projects. Other things that work well are life occupations like finding employment, cooking, and other daily activities. Cooking groups are excellent in every population and every setting. I want to share this funny cooking group story to emphasize what was said earlier about things that do not always work out as planned. In the absence of a kitchen at the last hospital where I worked inpatient, I decided that I would cook English muffin pizzas with the adolescents because I could do it in my office. I took the toaster oven out of the staff lounge, and we made them. While they cooked, we played a therapy game. I intently listened to their responses and did not notice anything was amiss until one of the participants said, "Bill, the oven's on fire." Indeed, the oven was on fire. The mishap did not necessitate the presence of the police or the fire department, which was good, and the fire extinguished quickly. It was my mistake as the toaster got frequent use and needed a cleaning. Those former clients (now adults) are probably still talking about it somewhere today.

All activities should be relevant and client-based. Every board game does not have to be a "therapy game." I have seen adolescents use the game of Life to talk about life issues. Do they want to get married? Do they want to go to college? It is perfect for generating conversation and is forward-looking. I had a favorite therapy game called Talk-It-Out, which was a lot of fun. Adolescents respond well to it, and I enjoyed playing the game with them. On that point, there are times when you can be in the group with the adolescents and times when you should not. When they are making a collage, they are not my peers. I would sit at my desk while they worked on things because it was all about them. They do not need a collage about a middle-aged guy. However, for the game Talk-It-Out, I would sit at the table and play it with them to be a leader and an organizer. It depends on the nature of what you are doing, and it is a judgment call.

I highly recommend the book 104 Activities That Build: Self-Esteem, Teamwork, Communication, Anger Management, Self-Discovery, Coping Skills because it has many activities you can do with adolescents that require almost no budget. One of them is a cup stacking activity. You stack seven cups into a pyramid using a rubber band with five strings on it for each group. The SEALS Activity Books are somewhat outdated now but may have some valuable ideas. The amount of psychoeducational handouts online these days is just staggering. You do not want to use paper handouts solely. Try to pair those with other activities.

Examples of Successful Group Activities

- Cooking

- Variety of crafts, i.e., mosaic tiling

- Tie-dying

- Competitive games

- Wii, Pictionary, Taboo, Scene It

- Psycho-educational and Topical Groups: Anger Management, Coping Skills, Stress Management, Self-Esteem, Goal-Setting, Leisure and Recreation, Vocational Skills

- Creative Expression

Successful group activities are cooking, crafts, and tie-dying. The number one favorite thing that the adolescents wanted to do was tie-dying. They loved it. And, the next day, it was an excellent advertisement for occupational therapy. They were very proud. Again, we can use regular store-bought games for therapeutic purposes. Examples are Wii, Pictionary, Taboo, Scene It, and things like that. We used Pictionary on Fridays to lighten things up. We did a lot of serious stuff during the week, but I always thought it was essential to get adolescents to laugh and have a good time for a little while. I would take them outside to play basketball. When you do that, they look for all the world like young people who do not have any issues. Supplying real-life experiences and fun games is beneficial, especially if you can get depressed people to laugh. I also did specific psychoeducational groups like anger management, coping skills, stress management, self-esteem, leisure, and recreation. These can also be done 1:1. The list goes on and on. It depends on the needs of your population/client.

Emerging Areas of Practice and Current Trends

- Private Practice

- Home-Based Practice

- Community Treatment Facilities

- Schools/School Districts

- Community Agencies

I had a combination of private and home-based practice that was very gratifying. This is one of the ways that we can re-establish ourselves as a provider of mental health services. There is a place out there for us. You might have to do a little marketing as a beautiful adjunct to psychotherapy. "Here's what I can do. We can work together on this." One of the things I loved about working in a hospital-based setting was talking with the rest of the treatment team or the person's therapist and saying, "Here's how they're doing in OT." Or, they would ask me how did a person do in OT. Did they participate? Did they interact with anyone? Those kinds of things.

OT is always a great testing ground for skills that are either being developed or are lagging. We should already be providing mental health services in schools. I worked in a school district, and believe me. They gave me way too many cases. I foolishly did not know how many would be a good number, but in any case, I did not have time to do mental health groups.

Interestingly, some people were threatened by me doing therapeutic kinds of things. "I've never heard of OTs setting behavioral or interpersonal goals." The more we do it, the more accepted it will be. As I said earlier in this presentation, many school districts are now looking to open programs, and some funding supports anti-bullying and anti-suicide programs. Now is the time to get involved with school districts. Community agencies are other areas that treat teens.

Rewards of Working With Adolescents

- Their gratitude for a listening ear

- Their eagerness to discuss problems

- Their candor about their circumstances

- Their acceptance of others/peers

- A desire to be or return to normal

- Some ability to see that things may not work out as planned

As we are nearing the end of this presentation, I would like to say that I enjoy working with the adolescent population because of their gratitude for a listening ear and eagerness to discuss their problems. Many are looking for a trusting adult, and they are not always comfortable telling their families and friends. They need someone to be candid with about their circumstances. It is so essential to the things that have been bothering them off of their chest.

Adolescents also are very accepting of others and peers. They are so much more accepting of gender and racial differences than previous generations. I think that this is a beautiful development that has occurred.

Adolescents have a desire to return to normal. Nobody likes to carry all of this around. If we can help them, they will be delighted. The other good thing about adolescents is that, unlike working with children, they can see that things may not work out as planned. Can you talk to them about the backup plan?

Questions and Answers

For presenting problems, would this be an immediate change in behavior, mood, relationships, et cetera, or is it gradual?

That is a great question. I would say that it is probably going to be more gradual. Depending on how involved the child is with the family system, they might not notice it at first, but over time they will. Conversely, some of these things will happen abruptly because of a crisis or a traumatic event. Family members may see many symptoms and grief reactions like depression and anxiety. It depends on the psychosocial stressor in terms of the intensity of the progression of those symptoms.

Can you please explain this idea of linear versus nonlinear disorders?

Sure, I would be happy to. If you think of a continuum or a yardstick, you have at one end the one-inch or two-inch part of the yardstick as you are holding it horizontally in front of you. To this end, the depression is either non-existent or under control. The other end of the yardstick at 30-36 inches represents suicide. Depression can be a lethal and terminal illness. This is something that people do not always realize. An adolescent can be at any of those points in between depending on how well they are responding to the medication or therapy. For example, if an adolescent goes to therapy and is on medication, they may go back two inches. The recovery model predominately used in mental health uses a timeline of sorts when looking at treatment.

Is your Interest Checklist something we can buy or download, and does it have a specific name?

I have been looking for a way of getting it distributed. It will not have a cost. It is called the Scranton Adolescent Interest Checklist. As I said, I copyrighted it after years of using it in research to find out adolescents' interests. Now, I want to move it in the next direction of people in the field using it. I never expected to make money on it. It was just a need I saw out there. It is named not for the University of Scranton but for the City of Scranton, where we are.

References

AOTA. (n.d.) Children and youth, 5-21. Health management and maintenance: Evidence-informed intervention ideas. Retrieved from: https://www.aota.org/Practice/Children-Youth/Evidence-based/EBP-Children-Youth/student-health-intervention.aspx

Bohnert, A., Lieb, R., & Arola, N. (2019). More than Leisure: Organized Activity Participation and Socio-Emotional Adjustment Among Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 49(7), 2637–2652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2783-8

Cara, E. & MacRae, A. (2013). Psychosocial occupational therapy: An evolving practice (3rd ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Delmar, Cengage Learning.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Suicide facts at a glance. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicide-datasheet-a.PDF

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5). Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

Favazza, A. R. (1996). Bodies under siege: Self-mutilation and body modification in culture and psychiatry. Johns Hopkins University Press.

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2016). Mental health facts children and teens. Retrieved from http://www.nami.org/NAMI/media/NAMIMedia/Infographics/Children-MH-Facts-NAMI.pdf

Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition. (2020). Am J Occup Ther, 74(Supplement_2):7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Rawlings, J. R., & Stoddard, S. A. (2019). A Critical review of anti-bullying programs in North American elementary schools. The Journal of School Health, 89(9), 759–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12814

Twenge, J., Spitzberg, B., & Campbell, W. (2019). Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36, 1892 - 1913.

Citation

Lambert, W. (2021). Mental health of adolescents: Psychosocial occupational therapy for adolescent populations. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5462. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com