Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Motor Supports For Handwriting Development, presented by Kristen Tompkins, OTR/L.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the underlying core control issues that can impact handwriting development.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the difference between efficient vs. inefficient pencil grasp patterns.

- After this course, participants will be able to list 3 exercises that support motor requirements for handwriting success that could be done at home or in the classroom setting.

Introduction

Today, we’ll discuss motor supports for handwriting development. With a lot to cover in just an hour, I’ll be moving through the material steadily. There will be time for questions at the end, but I hope many will be answered naturally throughout the presentation. It’s important to note that this course will not focus on the visual perceptual motor aspects of handwriting development. That is a much broader and more complex topic that would require at least two to three hours to cover adequately. With that, let’s get started.

Consequences of Handwriting Difficulties at School

According to Case-Smith and O'Brien in Occupational Therapy for Children, handwriting difficulties in school have several significant consequences. This is particularly important for those working in school-based practice or pediatric clinics, where parents often seek support for their child's handwriting challenges. Understanding these consequences helps us better advocate for appropriate interventions.

One major issue is that teachers may assign lower marks based on a student’s handwriting quality. If a teacher struggles to decipher a student's written responses, grading becomes difficult, even if the content is correct. Additionally, slow handwriting speed can limit a student’s compositional fluency and quality, making it challenging to complete assignments at the same pace as their peers. Parents frequently express concerns about how long it takes their child to finish homework, which can create frustration for both the child and their family.

Handwriting difficulties also impact note-taking. If students cannot keep up with writing during class or struggle to read their notes later, they may have difficulty studying for tests and quizzes. Furthermore, they might fail to develop higher-order writing processes, such as planning and grammar, which are critical for academic success. Over time, writing avoidance can lead to arrested writing development, where the student’s writing skills fail to progress at an expected rate. These challenges can have lasting effects on their academic confidence and performance.

To address these concerns, we first need to examine core control and its impact on fine motor development. Many adults, including educators and parents, often assume that handwriting difficulties stem solely from fine motor control issues. However, in many cases, underlying core weaknesses play a significant role. The first part of this course will focus on understanding the connection between core stability and fine motor control, as this area has shown a substantial impact in practice.

One particularly interesting observation, widely recognized by occupational therapy practitioners working with children in schools, is the change in the structure of children's hands over time. This shift has implications for handwriting development, and we will explore what might be contributing to these changes and how we can support children in overcoming these challenges.

Core Control and Impact on Fine Motor Development

Sleep

Research suggests that changes in infant sleep recommendations have had unintended consequences on hand development. The shift began when the American Academy of Pediatrics introduced safe sleep guidelines to reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. While these guidelines are crucial for protecting infants, they have also reduced the time babies spend in a prone position.

Infants not accustomed to sleeping on their stomachs may also resist spending time in that position while awake. Many prefer lying on their backs, which limits their opportunities to push up with their hands, lift their heads, and develop essential neck and upper body control. This change in sleep positioning has coincided with another major shift—the widespread use of infant car carriers. Years ago, these carriers were not as common, and parents would often hold their babies or use slings, allowing for more opportunities to develop head and neck strength. Today, it is common to see infants spending extended periods in car carriers, whether in the grocery store, at a restaurant, or even at church. Since these carriers keep babies on their backs, they reduce opportunities for active movement and postural development.

This decline in prone time has several developmental consequences. Reduced neck muscle control can affect visual development, as head stability is crucial in how infants learn to track and focus their gaze. Many elementary-aged children today still exhibit a head lag when pulled to a sitting position, which should have been resolved in infancy. Another concern is that some infants may skip the crawling stage altogether, negatively impacting upper body strength and coordination. Crawling plays a key role in developing shoulder and elbow stability and palmar arch formation, both of which are essential for fine motor skills.

During the early stages of crawling, infants use a rocking motion on their hands and knees, providing critical sensory and motor feedback. This movement strengthens the palm, wrists, elbows, and shoulders, establishing the foundational stability needed for future fine motor control. When babies do not experience this development phase, they may face challenges later on with tasks requiring hand strength and dexterity, such as handwriting. Understanding these developmental shifts allows us to assess better and support children who present with handwriting difficulties and other fine motor challenges.

Research: Relationship Between Prone Skills and Motor-Based Problem-Solving Abilities in Full-Term and Preterm Infants During the First 6 Months of Life

Research further supports the importance of prone positioning in early development. One study, The Relationship Between Prone Skills and Motor-Based Problem-Solving Abilities in Full-Term and Preterm Infants During the First Six Months of Life, provides valuable insights into this topic. Conducted by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University, the study presents preliminary evidence that full-term infants demonstrate more advanced exploration skills compared to preterm infants when engaged in problem-solving tasks.

The findings highlight a strong correlation between prone motor skills and advanced motor exploration abilities in infants. Additionally, the study indicates that prone motor development is significantly linked to overall motor-based problem-solving skills. This suggests that infants who spend more time in prone positions can better engage in problem-solving tasks that require physical exploration and motor coordination.

These findings reinforce the importance of prone time in infancy. If an infant does not have adequate opportunities to develop these prone motor skills, their ability to explore and interact with their environment meaningfully may be affected. This, in turn, could have broader implications for overall motor and cognitive development. For those interested in this area of research, I highly recommend reviewing this study for further insights into the developmental impact of early motor experiences.

Pencil Grasp

As we continue examining the connection between core control and fine motor development, we must recognize that pencil grasp norms have evolved over time. When I began working in schools in the 1990s, the thumb wrap grasp was classified as an atypical grasp pattern. At that time, it was considered inefficient to hold a pencil and was addressed as something that needed correction.

However, over the years, there has been a noticeable shift. At recent conferences, I’ve heard discussions highlighting how the thumb wrap grasp has become so common that it is now considered a typical grasp pattern. This doesn’t necessarily mean it is efficient, but it does reflect changes in how children develop fine motor control.

This shift raises important questions about why grasp patterns change and how broader developmental trends, such as reduced core stability and decreased time spent in prone positions, may influence how children learn to hold and control a writing utensil. Understanding these changes helps us approach handwriting interventions with a more informed and adaptive perspective.

Core Control

It is important to include testing for all core control postures when assessing fine motor or handwriting difficulties. Prone extension, supine flexion, and quadruped pointer balance are essential postures to evaluate, and we will look at some photos in just a moment for reference. If you are unsure about any of these, you can also assess tall kneeling as part of your evaluation. Including these in your assessments is highly recommended, especially in school-based settings where fine motor and handwriting referrals are common.

Educating parents and school staff about the impact of core weakness on fine motor control is critical in improving compliance with recommended exercises. Whether these exercises are incorporated into home routines or the classroom environment, gaining buy-in from adults who support the child is essential for progress.

Once these postures are tested, modifying them based on the student’s needs is often necessary. By identifying areas of weakness, you can determine the best way to adjust or downgrade an exercise so the student can experience success before gradually increasing the difficulty level. This process of staged progression is a key part of your role as a therapist, ensuring that the intervention remains appropriately challenging without being overwhelming.

Now, let’s look at the basic testing postures for core control.

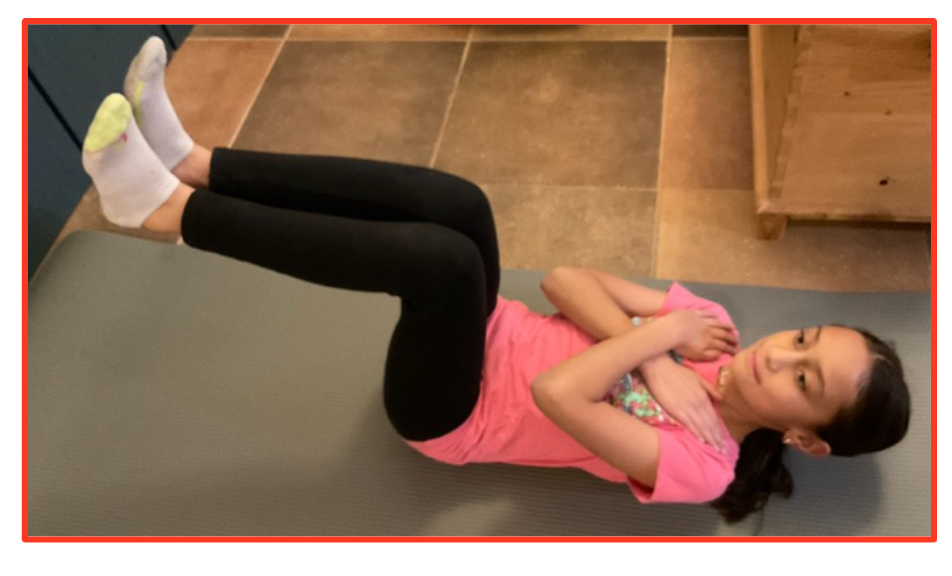

Supine Flexion

Supine flexion is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Supine flexion.

Supine flexion is assessed with the individual lying on their back on the floor. The hips, knees, and ankles should all be positioned at 90-degree angles. Arms should be crossed over the chest to prevent them from assisting in the movement. From this position, the individual lifts their head just enough to clear the floor without raising it significantly. The goal is to hold this crunch-like position, engaging the core muscles while maintaining proper form.

Prone Extension

Figure 2 shows prone extension.

Figure 2. Prone extension.

For prone extension, the knees and ankles should remain close while the individual lies flat on their stomach. This position resembles a Superman or Superwoman posture, where the arms, legs, and head lift off the floor. The elevation does not need to be substantial, but all limbs and the head should clear the floor. This movement engages the back, shoulder, and core muscles, helping to assess overall postural control and strength.

Quadruped

Quadruped, just hands and knees, is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Quadruped position.

Pointer Balance

Pointer balance is performed from a hand-and-knee position (Figure 4). The individual simultaneously lifts one arm and the opposite leg, holding briefly before returning to the starting position. The movement is then repeated on the other side, lifting the opposite arm and leg. This exercise helps assess core stability, balance, and coordination, as it requires controlled engagement of the trunk and extremities to maintain proper alignment.

Figure 4. Pointer balance.

There are standardized norms available for how long students of different ages should be able to hold these positions. However, I am not primarily focused on those normed times when assessing a child. My main goal is to determine whether they can even get into the position and hold it for a count of three to five seconds.

Many children often struggle to achieve and maintain the proper testing position. Some may not be able to assume the posture at all, while others may fall out of position quickly. Once we identify these challenges, the next step is to explore ways to modify these positions to create functional exercises that can be incorporated into a home or school routine. Let’s now look at how we can adapt these movements to support each child’s needs better.

Modified Supine Flexion

A great way to modify supine flexion is to have the student place their feet against a stable surface, such as a wall or the side of a piece of furniture, like a filing cabinet (Figure 5). This provides additional support and stability, helping students engage their core muscles while properly positioned. This adjustment can make the exercise more accessible for those who struggle to hold the standard posture while still allowing them to build strength and control.

Figure 5. Modified supine flexion.

In some cases, even with the modification of placing the feet against a stable surface, a student may still struggle to maintain the position. I have occasionally needed full support by holding their feet in place and ensuring their knees stay together. However, the goal is to gradually fade the amount of physical assistance over time, allowing the student to build the strength and control to maintain the position independently.

Modified Prone Extension

For prone extension, a couple of ways you could modify are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Modified prone extension.

One way to modify the exercise is to have the student keep their legs and feet on the floor rather than lifting them. This allows them to focus on lifting their arms and head, helping them gradually build the strength needed for the full position. Another option is to have the student place their feet against a wall or a piece of furniture for additional support, which can provide stability and make it easier to engage the necessary muscles while working toward the full posture.

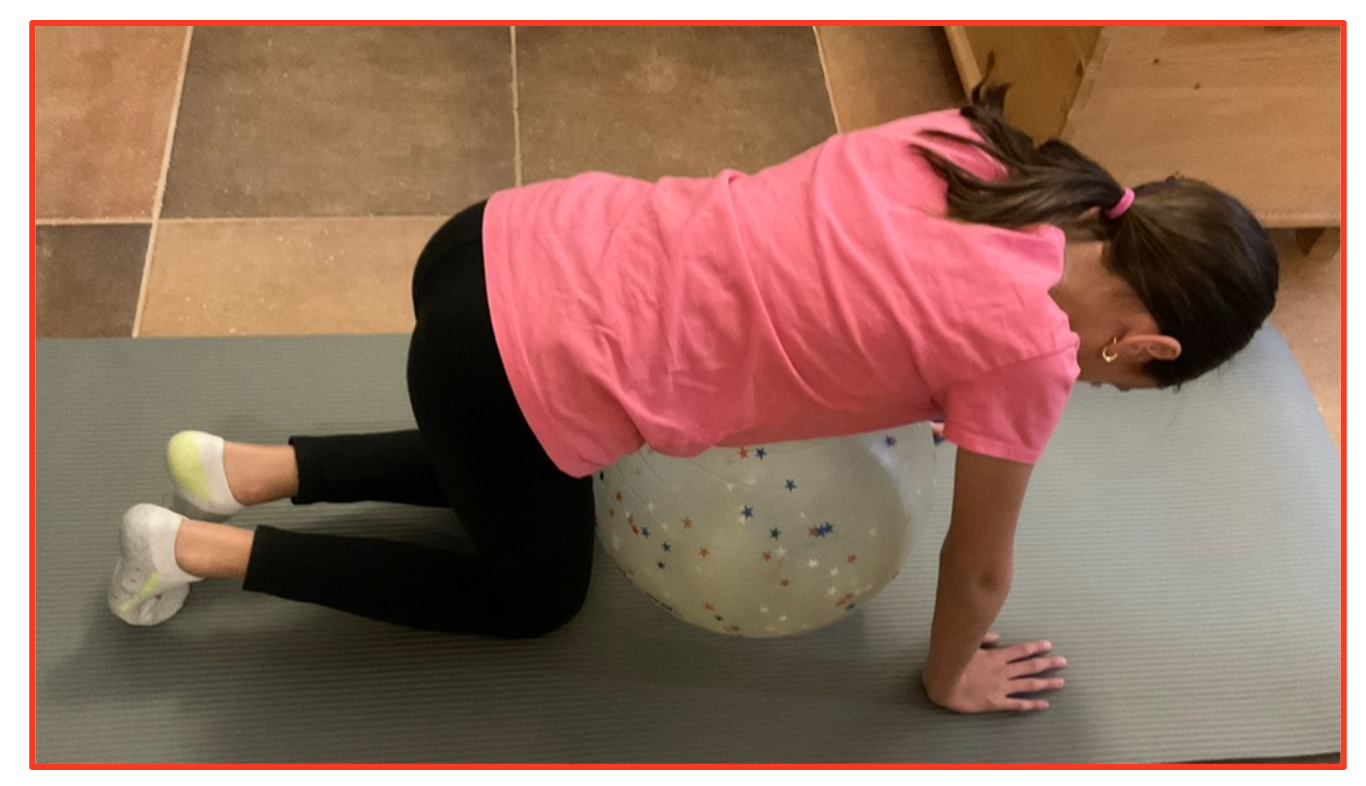

Modified Quadruped

A helpful approach to modifying the quadruped position is to provide the student with additional support. One option is to have them place their hands on a small therapy ball, which introduces stability while engaging core and upper body muscles, as shown in Figure 7. Another modification is to use a small preschool-sized chair with a pillow, allowing the student to rest their hands at an elevated position. These adjustments can help make the exercise more accessible while encouraging strength and coordination development.

Figure 7. Modified quadruped.

A useful modification for quadruped positioning is to place a small support under the student's tummy, such as a rolled-up towel, a small therapy ball, or a cushion. This support should provide enough assistance without causing the student to arch their back like a cat. The goal is to maintain a flat, tabletop-like back while ensuring the weight is evenly distributed across the shoulders, hips, and knees. In some cases, physical support may be needed initially, but the student should work toward maintaining the position independently over time.

Modified Pointer Balance

For pointer balance in Figure 8, you could begin by having the student practice lifting only one arm or leg.

Figure 8. Modified pointer balance.

Providing support under their tummy can be helpful if students struggle to maintain a quadruped position on their hands and knees. This same approach can also be used when working on pointer balance or prone extension to offer additional stability as they build strength.

As shown in Figure 9, incorporating a reaching activity can often make the task more engaging and purposeful for the student. Adding an interactive element helps with motivation and encourages functional movement patterns, making the exercise feel less structured and more like a fun and meaningful activity.

Figure 9. Pointer balance incorporates a reaching activity.

Tips for Core Control Exercises

A few additional tips to keep in mind include providing physical prompts or assistance when necessary to help eliminate compensatory movements. However, as the student's skills improve, it is important to fade that assistance to encourage independent control gradually. When assessing students and introducing these exercises, it is essential to watch for common substitutions and inform teachers and parents about them so they can monitor these patterns at home or in the classroom.

One common substitution in supine flexion occurs when a student pulls laterally or uses their arms to help lift their head off the floor. Some children may even cross their arms over their chest as instructed but then hook their thumbs or fingers into their mouth to assist in pulling their heads up.

In quadruped, students may compensate by sitting back on their heels rather than keeping their weight evenly distributed over their shoulders, hips, and knees. Some may also display a sagging trunk or an arched back, which assessments should note as they indicate underlying postural weaknesses.

Another common substitution when performing pointer balance is excessive trunk rotation when lifting an arm or leg. Some students may struggle to extend the leg straight instead of keeping it flexed and internally rotated, pressing it tightly against the supporting leg to create additional stability.

In quadruped, shoulder or elbow instability can also contribute to compensatory movements. Signs to look for include hyperextension of the elbows (example in Figure 10) or winging of the scapula, where the shoulder blades lift away from the back rather than remaining stable. Observing and documenting these patterns in assessment reports provides valuable insight into areas that need targeted intervention and helps guide appropriate exercise modifications.

Figure 10. Hyperextension in the elbow.

A little bit is normal, but it's very pronounced for some kids. So you want to take note of those things. If that's the case, it will be much harder for those kids to find stability with the weight evenly bearing through their shoulders and elbows.

Research: Moving Together: Understanding Parent Perceptions Related to Physical Activity and Motor Skill Development in Preschool Children

Another valuable piece of research to consider is Moving Together: Understanding Parent Perceptions Related to Physical Activity and Motor Development in Preschool Children. This study, conducted by researchers from Colorado, New Mexico, and New York, explored parents' role in shaping children's physical activity levels and the development of fundamental motor skills.

The study’s findings emphasize the critical need for parent support and education. Many parents may not fully recognize the impact of physical activity on motor skill development or understand how to provide the right opportunities for their children to build strength, coordination, and stability. This aligns with an important aspect of our therapist role—helping educate and guide parents better to support their child's motor development at home.

By equipping parents with knowledge and practical strategies, we can encourage meaningful engagement in activities promoting foundational motor skills. This reinforces the idea that early movement experiences, both structured and unstructured, play a vital role in a child's overall development and future success in fine and gross motor tasks.

Research: Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, Sleep Knowledge and Self-Efficacy Among Parents of Young Children in Canada

Another relevant study is Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, Sleep Knowledge, and Self-Efficacy Among Parents of Young Children in Canada. This research highlighted the need to raise awareness about engaging children in daily healthy movement during early childhood.

One key finding was that parents reported the least knowledge about muscle and bone-strengthening activities. This directly connects to our role as therapists in educating families about the impact of core strength on motor development. Many parents may not realize how foundational core stability is for fine motor control, coordination, and overall physical function.

This research reinforces the importance of securing parent buy-in for daily movement activities at home. Children may struggle with core weakness without regular engagement in strength-building activities, affecting their ability to develop essential motor skills. By increasing awareness and providing practical strategies, we can help parents take an active role in supporting their child's physical development in a manageable and effective way.

Pencil Grasp and Control

Okay, we are ready to jump into the fine motor aspects of this now. Let's first look at efficient pencil grasp patterns.

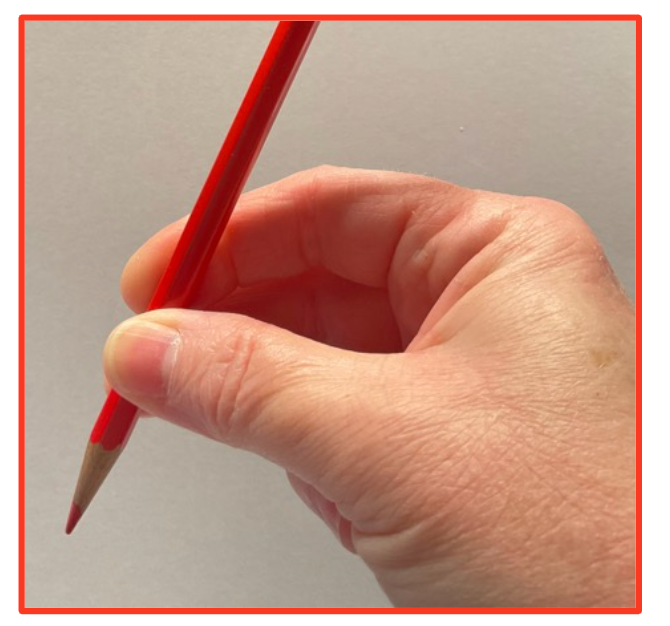

Efficient: Tripod Grasp

First is the tripod grasp, as seen in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Tripod grasp.

In an efficient pencil grasp, the pencil rests on the middle finger's side while pinched between the tip of the thumb and the index finger. As seen in the picture, one important characteristic of this grasp is that the thumb-index web space remains open. This open web space is a key indicator of an efficient grasp pattern, allowing for better movement control and reducing tension in the hand. When the web space is too tight or collapsed, it can restrict finger mobility and lead to fatigue, impacting writing endurance and fluidity.

Efficient: Quadrupod Grasp

Next is a quadruped pencil grasp, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Quadrupod grasp.

The only difference between this grasp and a traditional tripod grasp is that, in this case, the pencil rests on the side of the fourth finger, or ring finger, rather than the middle finger. However, the key feature remains the same—the thumb-index web space stays open. This openness is essential for maintaining an efficient grasp, allowing for controlled movement and reducing strain on the hand. Despite this slight variation, the grasp still supports functional and effective handwriting.

Efficient: Modified Tripod Grasp

The third grasp, which you may or may not be familiar with, is the modified tripod grasp (Figure 13). This variation is sometimes also referred to as the adapted tripod grasp. While it still provides functional control of the pencil, it differs slightly from the traditional tripod grasp in finger placement and positioning. Understanding these variations is important when assessing handwriting, as different grasp patterns can still be efficient if they allow for proper finger mobility, control, and endurance.

Figure 13. Modified tripod grasp.

The pencil is stabilized between the index and middle fingers in the modified tripod grasp. This is a great grasp to explore for yourself, as it provides a high level of stability by positioning the pencil in the natural cove between these two fingers. This placement offers a secure hold while allowing for an open thumb-index web space, essential for maintaining flexibility and reducing tension.

One of the key benefits of this grasp is that it still allows for effective shift and rotation skills, which are necessary for adjusting the pencil’s position during writing and manipulating small objects with precision. This makes the modified tripod grasp a functional and efficient alternative for individuals struggling with a traditional tripod grasp.

Key: Open Web Space

An open web space between the thumb and index finger is key to an efficient pencil grasp. The modified tripod grasp can be a great alternative for some children. One of its biggest advantages is that the hand is always available, whereas a pencil grip is not always accessible or practical for every child.

A significant benefit of maintaining an open web space is that it allows for developing shift and rotation skills, which are crucial in refining handwriting. These small push, pull, and rotation movements help children gradually decrease their handwriting size as they gain better fine motor control. While letter formation is the primary focus in early writing, the ability to adjust and refine letter size develops more prominently in kindergarten.

It’s also important to remember that the hand is divided into two functional sides. The skilled side consists of the thumb, index, and middle fingers, responsible for precision movements such as pencil control. This is why the tripod grasp is generally preferred for handwriting tasks. The stability, or power side, includes the ring and little fingers, which provide support and strength for heavier tasks. For example, when picking up a water bottle, the power side of the hand is engaged in managing the weight rather than just relying on the precision fingers.

We must look closer at inefficient pencil grasp patterns commonly appearing during handwriting assessments. While there is not necessarily an exhaustive list of grasp variations, several patterns frequently emerge, and recognizing them is essential for identifying potential handwriting challenges.

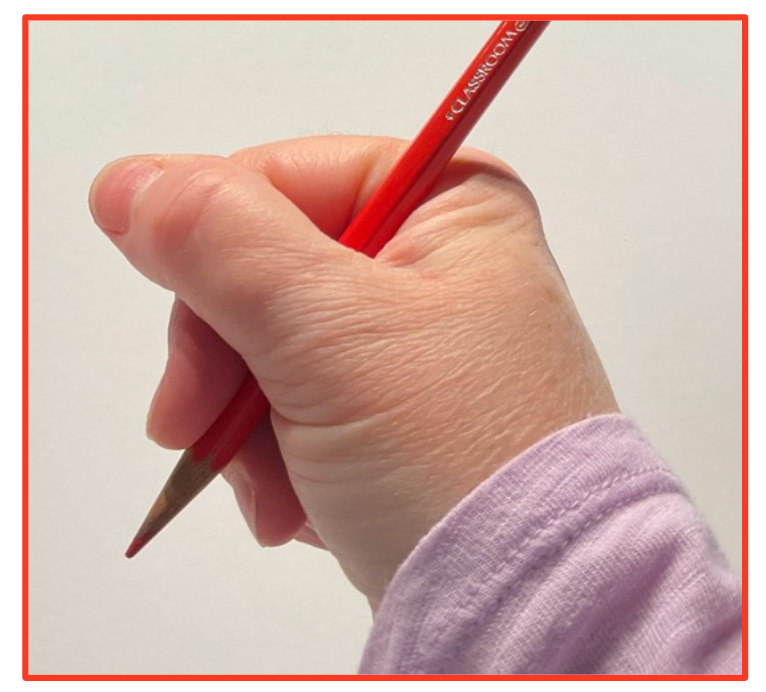

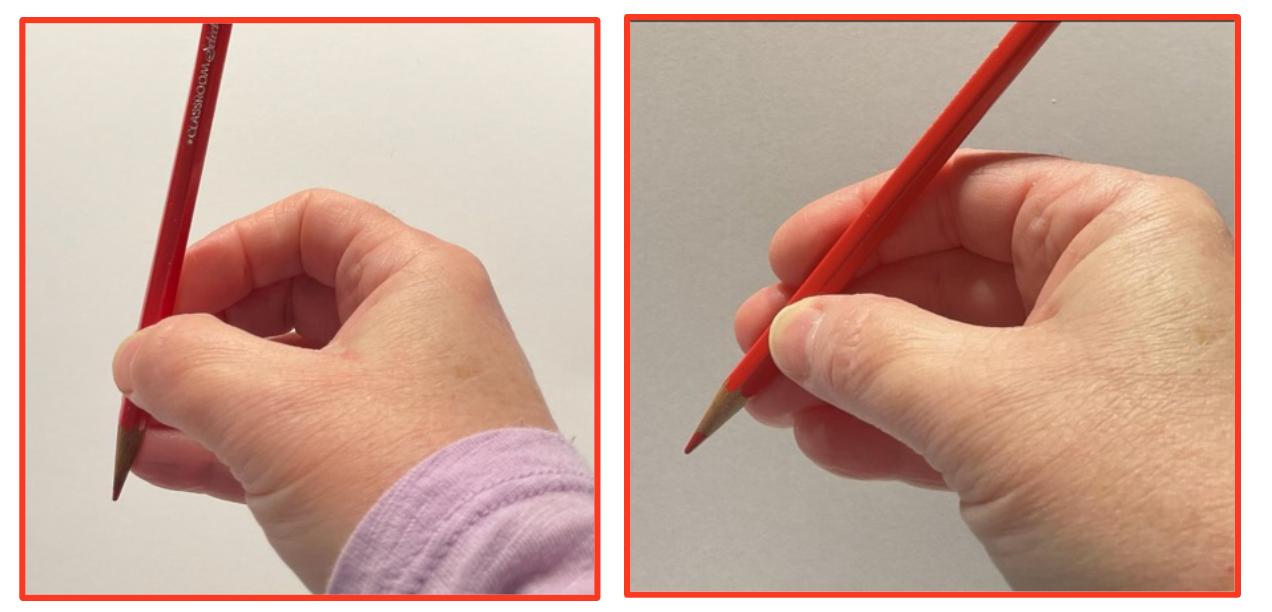

Inefficient: Thumb Wrap Or Cross Thumb Grasp

One inefficient grasp is the thumb wrap in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Thumb wrap.

This is where you use a tripod or a quadruped grass pattern, but you'll notice that the thumb is wrapped across the pencil and the index finger.

Inefficient: Lateral Pinch Grasp

Next is a lateral pinch in Figure 15.

Figure 15. Lateral pinch.

This grasp resembles the pinch we use when turning a key in a door. The hand is more fisted, with the pencil pressed firmly against the side of the index finger while the thumb holds it tightly in place. This grip tends to limit finger mobility and fine motor control, making handwriting movements more rigid and less fluid. Because the hand remains more closed, it can also increase muscle fatigue and reduce endurance during writing tasks.

Inefficient: Index Hook Or High Index Grasp

An index hook grasp is seen in Figure 16.

Figure 16. Index hook.

I frequently observe this particular grasp in left-handed students and children with very lax thumb ligaments. It is characterized by the thumb being extended and fixed in an extended or hyperextended position. The index finger’s distal joint hooks slightly around the upper portion of the pencil, while the pencil rests near the tip of the fourth or fifth digit.

Because this grasp creates a very rigid posture, much of the writing movement originates from the hand and wrist rather than the fingers. This is a common characteristic of inefficient grasp patterns. When the thumb-index web space remains closed, it restricts the ability to perform fine motor adjustments such as shift and rotation. Without these refined movements, the child compensates by engaging larger muscle groups. Instead of using the fingers for precise control, writing relies more on wrist, elbow, forearm, or even shoulder movements.

This shift in movement strategy results in decreased efficiency, reduced endurance, and increased fatigue as larger muscle groups are forced to take on a task that the small, precise muscles of the fingers should primarily manage. Over time, this can impact handwriting quality and the child’s comfort and ability to sustain writing tasks for extended periods.

Inefficient: Thumb Tuck Grasp

Another inefficient grasp is the thumb tuck. This is a tripod or quadrupod pattern, but the thumb gets tucked under the index finger or the pencil altogether (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Thumb tuck.

Inefficient: Interdigital Grasp

Then, you might also see an interdigital position, as noted in Figure 18.

Figure 18. Interdigital position.

The pencil usually gets tucked between the middle and fourth fingers, and the thumb is wrapped across for stability.

Inefficient: Three-Jaw Chuck

A three-jaw chuck grasp in Figure 19 looks similar to a tripod grasp but is not the same. It is a static grasp because the pencil does not rest in the web space.

Figure 19. Three jaw chuck.

The pencil tends to be more vertical or slightly angled in a three-jaw chuck grasp. The thumb's posture is fixed, eliminating flexibility and preventing the use of shift and rotation movements. This lack of mobility makes fine motor adjustments more difficult, impacting writing efficiency and control.

Inefficient: Digital Grasp

The digital grasp (Figure 20) is similar, except that the ring and little finger are extended.

Figure 20. Digital grasp.

This is a fixed posture.

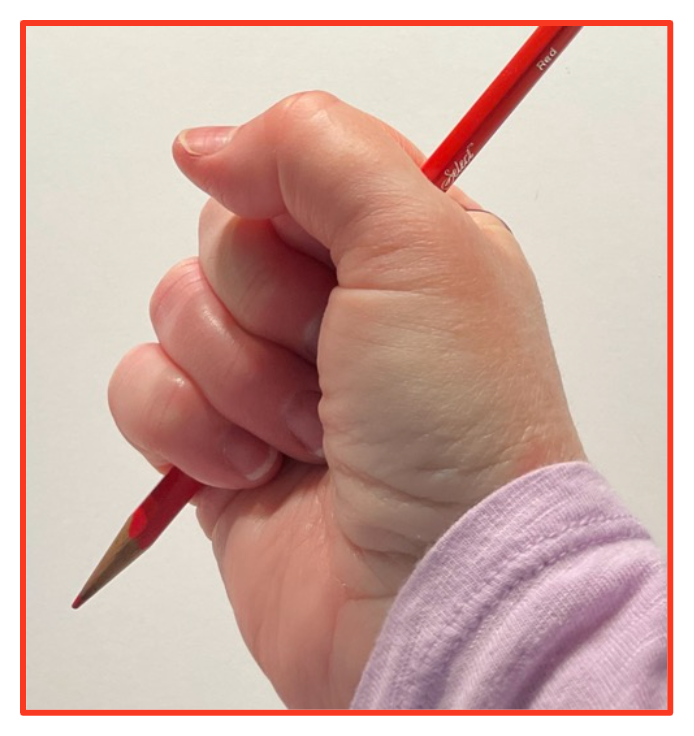

Inefficient: Pronated or Pronate Digital Grasp

Next is seen a pronated grasp in Figure 21.

Figure 21. Pronated position.

This grasp is a typical developmental stage for infants as they learn prehension skills. Early on, they progress from a fisted grasp to a pronated grasp as part of their natural motor development. However, this grasp should not persist in a school-age child, as it lacks the refined control needed for efficient handwriting.

Inefficient Grasp: Fisted/Palmar/Gross

A fisted grasp might also be called a palmer or gross grasp, as seen in Figure 22.

Figure 22. Palmer or gross grasp.

Wrist Postures

Wrist posture plays a significant role in handwriting efficiency. A slightly extended wrist position is ideal, while a neutral wrist is considered adequate. However, a hooked or flexed wrist is less efficient and generally not recommended for writing.

Hooked wrist postures are particularly common among left-handed students, providing a functional visual and spatial planning advantage. When writing with a neutral or extended wrist, a left-handed writer’s hand naturally covers their previous work, making it difficult to judge spacing accurately. Until spacing becomes an automatic skill, some left-handed students develop a hooked wrist position to lift their hands away from the writing surface, allowing them to see their work more easily.

Wrist position also influences finger movement and overall grasp efficiency. A flexed wrist naturally causes the fingers to extend, which is not ideal for grasp control. You can test this yourself—if you flex your wrist and relax your hand, your fingers will extend automatically. In contrast, an extended wrist encourages the fingers to flex, promoting a more controlled and efficient grasp pattern.

One effective way to encourage a more extended wrist position is to have students practice writing or engaging in fine motor activities on a vertical surface. Writing on a slanted or vertical surface naturally facilitates wrist extension, reinforcing proper hand positioning for writing and other fine motor tasks. This simple adjustment can help improve writing efficiency, endurance, and comfort.

Common Underlying Issues Resulting in Inefficient Grasp Patterns

When evaluating inefficient grasp patterns, it’s important to consider the underlying factors contributing to these compensatory movements. One of the primary causes is a weak or underdeveloped palmar arch. To assess for palmar arch strength, I often ask students to make a sign language “C” or pretend they are holding a ball in their hand. Ideally, this should create a visible curvature in the arch of the hand. However, children with weak palmar arches often exhibit a flattened or "bear claw" position instead, which can significantly impact their ability to manipulate writing tools effectively.

Other contributing factors are low muscle tone and ligament laxity. Muscle tone is often misunderstood—it is not the same as muscle strength. Muscle tone refers to the resting state of a muscle, influencing how it responds to movement and external pressure. In individuals with typical muscle tone, there is a slight elasticity when pressing on a muscle belly, which quickly rebounds after being touched. High muscle tone, such as that seen in some individuals with cerebral palsy, creates extreme tightness, while low muscle tone results in a softer feel with less resistance.

Earlier in my career, I would document that certain students had low muscle tone, only for parents to return from a neurologist appointment saying, “My doctor said my child does not have low muscle tone.” This experience taught me that “low muscle tone” must be used carefully. Neurologists diagnose clinically significant hypotonia, whereas many of the students I work with do not meet that threshold. Instead, I now describe these children as having “low-normal” muscle tone, meaning their muscles feel softer than typical but are not classified as hypotonic.

Children with Down syndrome often present with clinically significant hypotonia, but many others fall within the low-normal range. This is often accompanied by ligament laxity, which affects joint stability. Ligaments function like small rubber bands that help stabilize joints. When ligaments lose elasticity, they become looser, leading to excessive movement in the joints. In children with normal ligament tension, pressing on a finger joint results in a natural stopping point. However, in children with lax ligaments, the joint moves past this point, making it more difficult to maintain stability when grasping objects.

Muscle tone, ligament integrity, and bone structure create a stable foundation for fine motor control. When a child has low-normal muscle tone and ligament laxity, they lose some of this natural stability, often leading to inefficient grasp patterns. These children frequently develop fixed or static grasps, relying on rigid stabilization rather than dynamic finger movements. One of the most common compensations in children with ligament laxity is hyperextension when holding a pencil in one or more finger joints. The body attempts to create stability without adequate muscular and ligamentous support.

Understanding these foundational issues is critical in identifying why inefficient grasps develop and how to address them effectively. By recognizing the impact of palmar arch strength, muscle tone, and ligament laxity, therapists can implement targeted interventions to help children develop more efficient and functional grasp patterns.

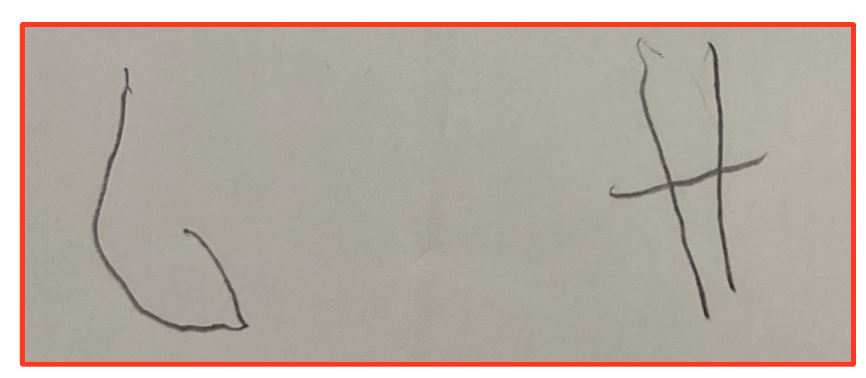

Fine Motor Impact on Handwriting Development

Fine motor skills are crucial in handwriting development, influencing a child’s ability to form letters and write efficiently. The ability to produce straight vertical, horizontal, and diagonal lines relies heavily on fine motor control and the precision needed to form angles when changing line direction. Smoothness and uniformity in curved lines and the accuracy of starting and stopping at the correct points depend on these skills' refinement.

One common difficulty seen in students with fine motor challenges is closing a circle. Students struggling with fine motor precision may have difficulty aligning the start and end points, resulting in gaps or misalignment. Similarly, fine motor deficits can impact a student's ability to maintain writing boundaries, leading to letters that drift outside of lines or inconsistently spaced words. This difficulty with spatial organization often makes handwriting appear less controlled and legible.

Endurance for utensil use is another key consideration. Some students may demonstrate correct letter formation when writing in short bursts but begin to struggle as fatigue sets in. The distinction between comfort and endurance is important. While some students may be able to sustain writing for long periods but experience discomfort, others may fatigue quickly, even if they are not reporting pain. In both cases, diminished endurance affects students' ability to produce consistent and legible writing over time.

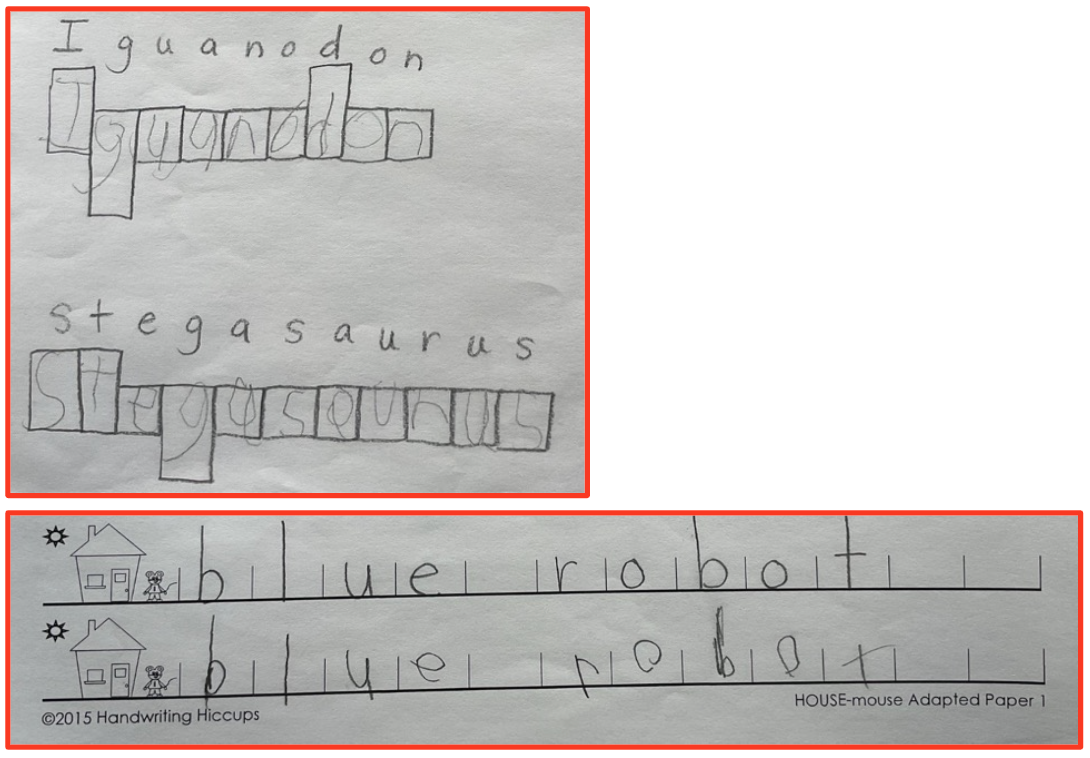

To better illustrate these challenges, we can examine examples of letter formation, such as in Figure 23. These examples highlight how fine motor control influences handwriting quality, showing variations in stroke accuracy, letter spacing, and consistency in line formation. By recognizing these difficulties, targeted interventions can be developed to strengthen fine motor skills and improve handwriting efficiency.

Figure 23. Letter formation.

This student demonstrated a solid understanding of letter formation and the motor actions required to create the letter “G” and the hill shape. However, they encountered difficulties with maintaining straight line quality, achieving smooth curves, controlling angles accurately, and ensuring precise points of intersection. These challenges are important indicators of fine motor control and coordination.

When evaluating handwriting, these elements become immediately noticeable. One of the first considerations is whether the student possesses the motor plan necessary for forming letters correctly. If they do, the next step is to determine whether their difficulties stem from a visual-motor integration issue—meaning they struggle with translating what they see into motor actions—or if the primary challenge lies in fine motor control, affecting their ability to execute movements smoothly and precisely.

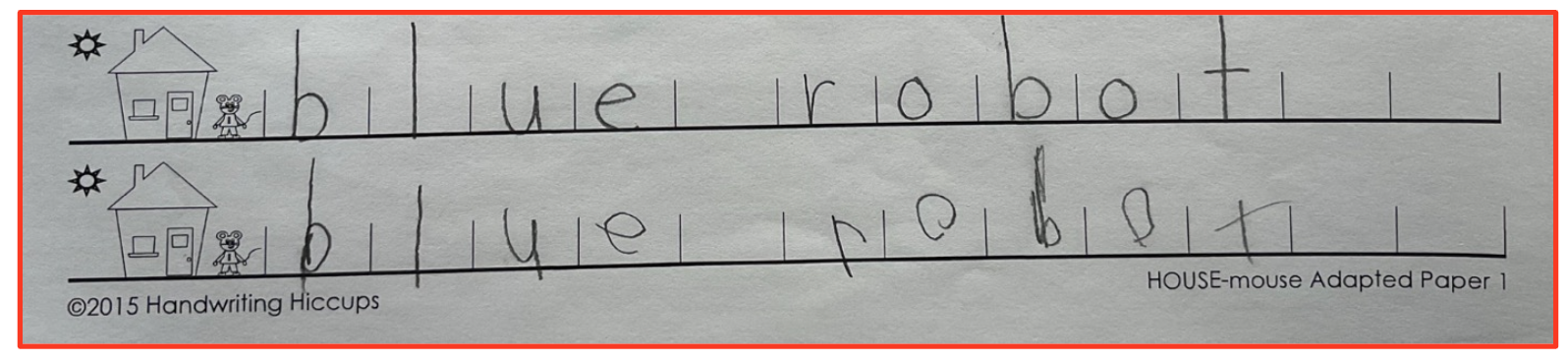

A clear example of this analysis is illustrated in the bottom example in Figure 24. My model drawing of the student’s “blue robot” is shown at the top, while the student’s attempt at copying it appears underneath. This comparison highlights their ability to replicate details, maintain proportions, and control movements when working from a structured reference. By examining these factors, we can better identify whether their handwriting struggles are rooted in visual-motor difficulties, fine-motor weakness, or a combination of both, guiding the next steps in intervention and skill development.

Figure 24. Handwriting example.

This student demonstrates a more advanced skill level than the first example, but there are still noticeable motor control challenges. One key issue is the accuracy of closing circles, such as with the letter "O" or the first "B," where slight overlapping occurs. Additionally, there are difficulties with precise starting and stopping on the baseline, which further indicates motor control inconsistencies.

Even when a student has a strong grasp of letter formation, these small inaccuracies can impact overall legibility and fluency. Subtle inconsistencies in closure, alignment, and spacing can make handwriting appear less polished, even if the general structure of the letters is correct. Identifying these motor control difficulties allows for more targeted intervention to refine precision, helping the student develop smoother, more controlled writing patterns.

Strategies/Adapted Equipment for Handwriting Support

Now, let’s explore some strategies for improving pencil grasp. Various pencil grips, adapted pencils, and other writing tools can help students develop a more efficient and functional grasp. Each tool serves a specific purpose, and selecting the right one depends on the student's unique needs.

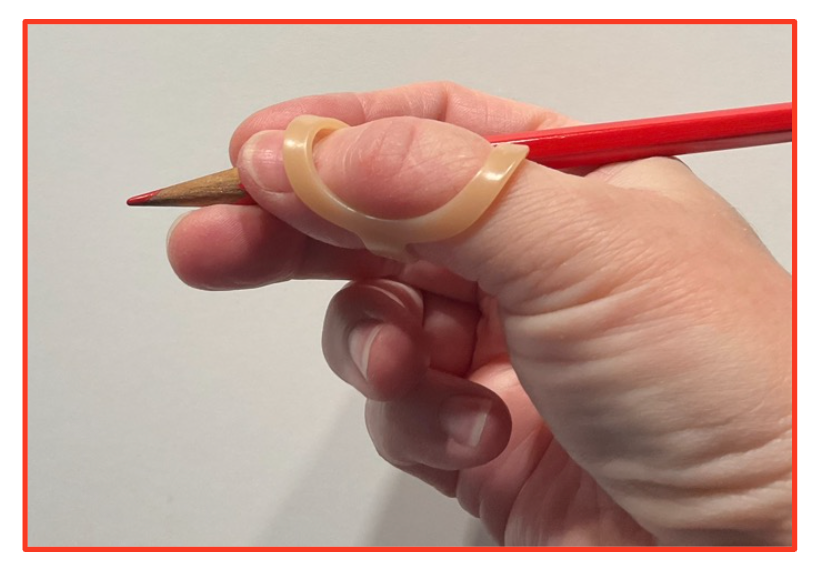

The first example, shown in Figure 25, demonstrates a grip that provides additional support by positioning the fingers correctly on the pencil. This promotes greater control and stability, helping to reduce strain and improve handwriting precision. Some grips encourage a more open web space, while others help prevent excessive pressure or compensatory movements.

When considering adaptations, it’s important to match the tool to the specific challenges a student is facing. Some students may benefit from grips encouraging tripod grasp, while others might need a weighted pencil or a shorter writing tool to enhance control. Understanding how these modifications affect motor coordination allows for more individualized support, ultimately improving comfort and handwriting efficiency. Let’s look at how these tools can assist in handwriting development.

Figure 25. Pencil grips. Images: Used with permission from Therapy Shoppe.

This particular grip can be a useful starting solution for students with a thumb wrap grasp. Its design includes a built-in wall that helps guide finger placement, providing a designated spot for the thumb on one side and the index finger on the other. For many students struggling with a thumb wrap grasp, this structure offers the support needed to encourage a more functional grasp pattern.

When I introduce a pencil grip, it is not a random trial-and-error process. Instead, I assess the specific grasp issue a student presents and then select a grip that aligns with their needs. While this particular grip is often my first choice for addressing a thumb wrap grasp, it is not universally effective for every student. I explore alternative grip styles to find the best fit for their hand positioning and motor coordination if necessary.

In this example, the left side features a crossover grip, while the right side shows a Grotto grip.

Figure 26 presents yet another type of grip that can be an alternative approach. By understanding how different grips function and applying them strategically, we can better support students in developing a more efficient and comfortable writing grasp.

Figure 26. Some other grip examples. Images: Used with permission from Therapy Shoppe.

These grips are particularly beneficial for students with difficulty correctly positioning their fingers for a tripod or quadrupod grasp. They provide structured guidance, helping to correct inefficient grasp patterns by offering designated placement areas for the thumb and fingers. Many of these grips include built-in baskets that anchor the fingers in a more stable position, giving students mechanical support while reducing excessive movement.

Some examples include the Writing Claw, which is especially effective for kindergarten-age students, and the Pointer Pencil Grip, which features a single basket that can be used for either the thumb or index finger. Another option is the Finger Cup Duo, which includes two baskets—one for the thumb and one for the index finger—to reinforce proper finger alignment. There is now a much wider selection of pencil grips available than in the past, making it easier to find a solution tailored to each student’s needs. The grips shown in these images come from Therapy Shop, a resource that has been extremely helpful for our district, but many of these products are also available from other vendors, including Amazon and some physical stores.

While these structured grips can be highly effective, they have some drawbacks. Young students may need time to learn where to place their fingers correctly, as these grips require more structured positioning than traditional options. Additionally, because they are not as easy to slip on and off, older students who need to erase frequently may find them cumbersome. Unlike simpler grips that allow for a quick flip of the pencil, these require the student to reposition their fingers each time, which can slow down their writing process. These considerations should be factored into the decision when selecting the most appropriate grip for a student.

A more substantial grip may be necessary for students who struggle with a collapsed thumb-index web space or require additional support for palmar arch control. The Jumbo Grip, Jumbo Contoured Foam Grip, or Jumbo Egg Grip, all shown in Figure 27, can provide the extra stability needed for better grasp mechanics. These grips help maintain proper finger positioning while reducing excessive strain on the hand, making them an excellent choice for students who need additional support to develop a functional and comfortable writing grasp.

Figure 27. Larger grips. Images: Used with permission from Therapy Shoppe.

I’ve successfully used the jumbo egg grip with students who have a combination of palmar arch weakness, low muscle tone, and ligament laxity. The egg grip's larger size and contoured shape provide additional stability and support, making it a good option for students who struggle to maintain proper hand positioning. This grip reduces strain and encourages a more functional grasp pattern by offering a more substantial surface to hold onto.

Figure 28 shows additional grip options that may also be effective, depending on the student's specific needs. Exploring different grip styles and understanding how they support hand function allows for a more individualized approach to improving pencil grasp and handwriting efficiency. Matching the right grip to the student's unique challenges can significantly affect their ability to write comfortably and effectively.

Figure 28. Additional grip styles and Ferby pencil. Images: Used with permission from Therapy Shoppe.

Some students are on the verge of developing a proper tripod grasp but need a little extra prompting to position their fingers correctly. In these cases, a basic pencil grip can be helpful. The jumbo pencil grip is a larger version that provides additional support, but the standard pencil grip is often enough for students who need gentle guidance.

One useful feature of the pencil grip is its three distinct sides, which indicate where the fingers should be placed. It also includes an "R" and an "L" on different sides to help guide thumb placement for both right-handed and left-handed writers. This simple structure makes it easier for students to position their fingers consistently, reinforcing a more functional grasp pattern.

Another option is an adaptive pencil, such as the Ferby pencil. This pencil has a slightly larger barrel and a triangular shape, providing three clear sides for finger placement. It can be a great alternative for students needing a little extra structure without a separate grip. The natural shape of the pencil helps guide the fingers into a more stable position while allowing for flexibility in movement.

Additional tools can help students who struggle with pencil angles, particularly those using inefficient grasps like the three-jaw chuck or digital grasp, where the pencil is too vertical. The Handiwriter and the RingWriter clip are designed to cue students to rest the pencil properly in the thumb-index web space. The RingWriter clip is a small ring with an extension that holds the pencil in place, though it can be tricky to use since it must fit the student’s index finger or thumb correctly.

The Handiwriter, shown in Figure 29, is a more adjustable option, making it a versatile tool for a wider range of students. While images of these particular tools were not available for inclusion, they are widely accessible and easy to reference. Exploring different options and understanding how each tool supports pencil grasp development allows for a more individualized approach, ensuring that students receive the right level of guidance to improve their writing mechanics.

Figure 29. The Handiwriter. Image: Used with permission from Therapy Shoppe.

Sometimes, when pencil positioning is the main issue, tools like the Handiwriter can help. The Handiwriter has a longer loop with an attached bead that students can hold in their palms using the ring and little fingers, reinforcing proper finger positioning. However, this extra component can make the process overly complicated for some children. In these cases, I often modify the tool by removing the looped bead and using the Handiwriter to adjust the pencil angle. By simplifying the setup, the focus remains on improving grip without overwhelming the student with too many adjustments.

For some students, grasp difficulties are not just about positioning but also about understanding pressure. These students may press too lightly, making their writing faint and inconsistent, or they may press too hard, leading to fatigue and excessive pencil drag. In such cases, weighted aids can be helpful. Adding weight to the pencil provides sensory feedback, helping students develop better control over downward pressure and improving the fluidity of their writing movements.

Figure 30 shows examples of weighted aids that help students regulate their pencil pressure. These tools can be particularly effective for those who struggle with proprioceptive awareness, as they help reinforce an appropriate balance between force and control while writing.

Figure 30. Weighted aids. Images: Used with permission from Therapy Shoppe.

You might try a weighted pencil or a hand, Wrist, or forearm weight with the weighted pencil. I would say sometimes they are just not super comfortable. There are silicon pencil sleeves that you can cut to size and stretch over the metal part of the weighted pencil to make it more comfortable.

One last thing that you may or may not be familiar with as a possibility is the use of an oval 8 splint in Figure 31. An oval 8 splint is a great option for kids who have those lax ligament issues in the thumb in particular.

Figure 31. Oval 8 splint.

Once hyperextension in the interphalangeal (IP) joint of the thumb is blocked, it often creates a chain reaction down the rest of the thumb. Many students with thumb hyperextension experience it in both thumb joints, but stabilizing just one joint often improves overall mechanical stability. This added support allows for better control and a more functional grasp.

One downside of using the Oval-8 splint is that it is small and easily lost in a classroom setting. A student must be mature enough to keep track of it, as it’s not realistic to expect a teacher to be responsible for such a small, neutral-colored item. However, these splints are available in multiple sizes, and the Oval-8 company provides a printable measuring tool to help ensure the correct fit before ordering. This can be particularly helpful for students who need individualized support.

For the right student, the Oval-8 splint can be a great solution, especially for home use, where it may be easier to keep track of. It may also be a better option for older, more responsible students who can manage the splint independently. Another consideration is that if you live in a region with high temperatures, such as Las Vegas, the splint can melt or warp if left in a hot car. This is something to keep in mind when storing or transporting it.

Another strategy, shown in Figure 32, focuses on handwriting structure rather than pencil grip. Using individual boxes for letter formation can give students clear visual boundaries, helping them develop consistency in letter size, spacing, and alignment. This approach is particularly useful for students who struggle with spatial awareness and need extra guidance to refine their handwriting skills.

Figure 32. Individual boxes for letter formation.

This approach is beneficial because it provides clear, concrete boundaries that help cue students to adjust or reduce the size of their muscle movements. By using the visual system as a guide, students receive immediate feedback on how to refine their handwriting control.

I have developed my own grid-style paper called House Mouse Paper, which comes in different sizes to accommodate varying needs. However, some students require an even larger format. In these cases, it can be helpful to explore ready-made graph-style paper available in different sizes and recommend options to parents and teachers based on what best suits the student's needs.

For students who are still making very large letter formations, starting with larger boxes can be an effective way to refine their motor movements gradually. Initially, a simple hand-drawn grid can provide structure, allowing the student to focus on one word at a time. As the student begins to adjust their movements to fit within these boundaries, the size of the boxes can gradually be reduced over time. This progressive approach helps students transition to adapted grid-style or standard graph paper as their fine motor control improves.

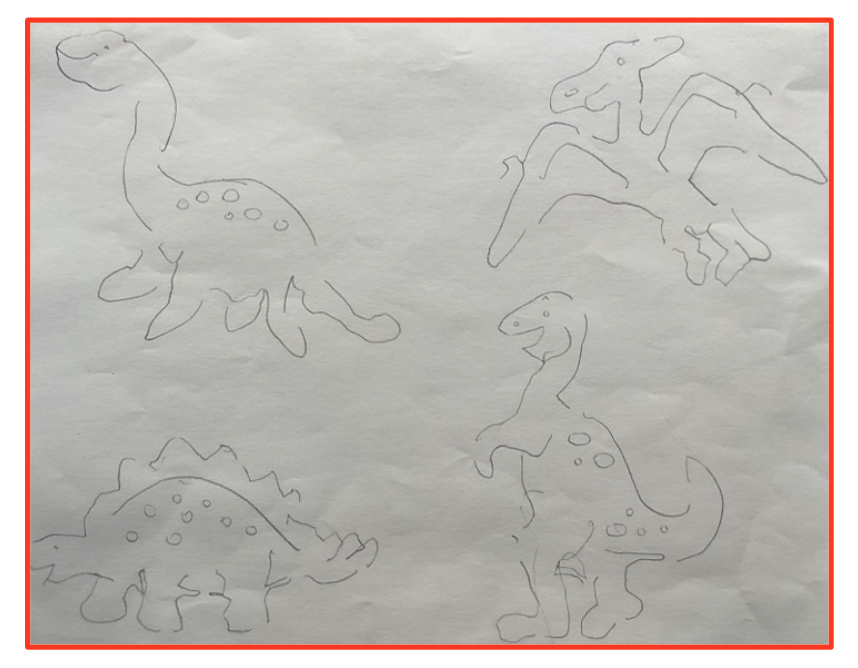

Figure 33 introduces another strategy using stencils with very narrow pathways. These stencils create physical constraints, guiding students toward more controlled letter formation and encouraging precise, deliberate movements as they refine their handwriting skills.

Figure 33. Examples of drawings using stencils.

These stencils help develop essential fine motor skills, including changing pencil line direction, rotating for small circles, and making subtle shifts with the fingers. They are inexpensive and widely available on Amazon, often coming in sets of eight or ten for just a few dollars.

There are many themed options, from dinosaurs to space to farm animals, making them engaging for young students. However, it is important to choose stencils with narrow pathways rather than wide-open designs. Most students who struggle with handwriting do not yet have the control needed to keep the pencil pressed against the edge of a large, open stencil. The wide spaces can lead to uneven, uncoordinated movements rather than reinforcing precision.

Stencils with narrow pathways naturally help guide the pencil, acting as self-correcting tools. These designs encourage better control, particularly for small circular motions, and allow students to refine their handwriting skills with structured support. Providing clear boundaries helps reinforce accuracy without requiring constant verbal cueing, making them an effective and engaging tool for handwriting practice.

Home or Classroom Exercise to Target Shift & Rotation Skills

Now, look at another activity designed to improve shift and rotation skills. In this example, I created an exercise called Ready to Race: Stay on the Track (Figure 34). The goal is for students to practice controlled pencil movements while maintaining accuracy.

Figure 34. Car worksheet.

I start by modeling the task using the top set of circles, demonstrating how to keep the pencil within the track. I tell the child, "I’m like a car and must stay on the track. Stay on the track. Don’t go off the track." The focus is not on speed but precision, helping them develop fine motor control as they guide their pencil smoothly along the path.

Figure 34 shows how this structured activity reinforces accuracy while engaging in the task. By following the curved lines carefully, students strengthen their ability to make small, controlled pencil movements, improving their overall handwriting coordination.

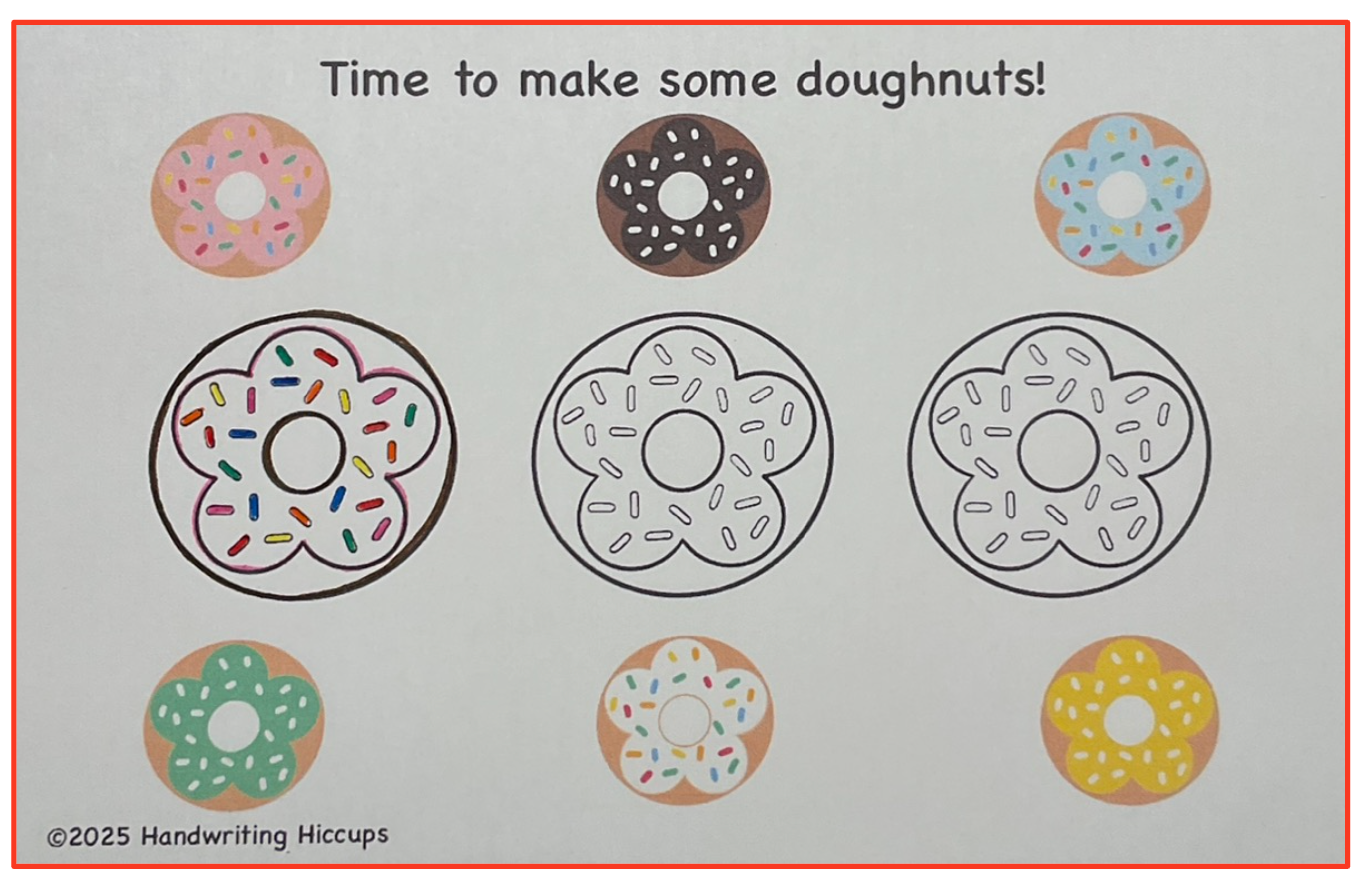

Another activity in Figure 35 uses donuts.

Figure 35. Doughnut worksheet.

You can work on rotation skills while tracing around the curves of the flowery frosting design, encouraging smooth and controlled movement. Then, when coloring in all the small sprinkles on the donut, students practice small shift movements, refining their ability to make precise adjustments with their fingers.

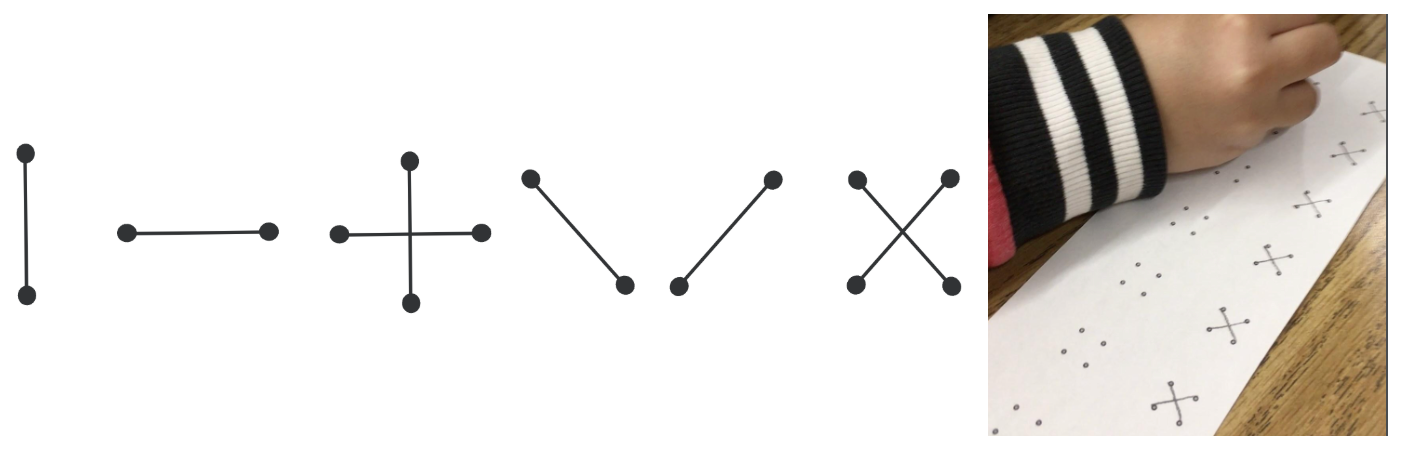

Targeting start and stop accuracy is an essential skill I work on with many students. One example is a student practicing the letter X, as shown in Figure 36. He needed to improve his ability to form diagonals, so this exercise was particularly useful in helping him refine both directionality and control. Focusing on stopping at the correct points and maintaining accuracy, he developed stronger motor planning for diagonal strokes, which can be a common challenge for many students.

Figure 36. A student practicing writing X.

He also needed to slow down. He tended to work at a manic speed, making it difficult to control his fine motor movements. The dot strategy helped him pace himself by providing clear start and stop points. His accuracy improved significantly once he understood the expectation of beginning and ending at the dots.

Providing a model can be a helpful way to introduce this strategy. This could mean modeling the top row or alternating examples until the student gets the hang of it. As they become more familiar with the pattern, you might only need to demonstrate the first before they can continue. This gradual transition allows the student to build independence while reinforcing control and precision in their writing.

Palmar Arch Development

Engaging in activities that encourage weight-bearing and hand activation can support palmar arch strength development. Playing games on hands and knees, such as crawling-based activities or crab walk games, can be particularly beneficial. These movements promote weight-bearing through the palms, elbows, and shoulders, reinforcing hand strength and stability in a natural and playful way.

Spray bottle activities are another excellent way to strengthen the palmar arch. Simple tasks like watering plants at home or during recess, spraying sidewalk chalk designs with water, or using a spray bottle to clean tricycles or playground surfaces provide meaningful opportunities to build hand strength. The squeezing motion required to operate a spray bottle directly targets the muscles involved in palmar arch control.

Another effective activity is the classic tennis ball game, where a small slit is cut into a tennis ball to create a "mouth." By adding googly eyes or drawing a face on it, the ball becomes a fun character that can "eat" small objects like tokens or buttons. Squeezing the ball open to feed it requires significant hand strength and promotes palmar arch development.

For students who press too hard while writing, it is important to determine whether the issue is related to their pencil grasp. If grasp is not the underlying cause, several strategies help regulate pressure. One effective approach is having them use a mechanical pencil and challenge themselves not to break the lead. Because mechanical pencil lead is fragile, this provides immediate feedback on pressure control. Another option is having them complete drawing activities on tissue paper, ensuring they apply just enough pressure to make marks without tearing the delicate surface.

One strategy I often use to teach teachers involves daily clipboard activities. In this exercise, the student holds the clipboard in the air rather than resting it on a desk or table. While holding it, they complete simple drawing tasks, such as connecting matching items or circling correct answers. Because they must press the clipboard into their non-dominant hand while applying controlled pressure with the pencil, they create their feedback loop for force regulation. This can be particularly helpful for students struggling to adjust their writing pressure.

Weighted pencils or hand and wrist weights are also potential solutions, though sometimes a simple adjustment—such as using a darker—leaded pencil—provides the best result. A softer lead requires less pressure to make clear marks, reducing strain while producing legible writing. Exploring different approaches allows for individualized solutions that help students develop a more functional and comfortable writing style.

Research: How Effective is Fine Motor Training in Children with ADHD

Another important area of research focuses on the effectiveness of fine motor training in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Researchers from Germany and Switzerland conducted a scoping review examining the impact of motor deficiencies in children with ADHD, particularly how these challenges contribute to academic underachievement, frustration, and low self-esteem.

Their findings indicated that fine motor training interventions can be effective, with twelve studies showing clear benefits. The review also highlighted that motor deficiencies are common in children with ADHD, yet they are widely undertreated. The research emphasized the importance of providing positive feedback on motor performance and noted that children with ADHD respond particularly well to a playful, interest-driven approach.

This reinforces what many of us see in practice—engagement is key. Incorporating play into interventions makes a significant difference, especially at the elementary level. When activities are enjoyable and motivating, children are more likely to participate willingly and invest effort in improving their skills. Finding ways to integrate fun into fine motor training increases engagement and enhances learning and skill development in a meaningful way.

Research: Effects of Fine Motor Training in Improving the Legibility of Handwriting of Students With Special Educational Needs

Another study examined the effects of fine motor training on improving handwriting legibility in students with special education needs. Researchers in Malaysia found that fine motor activities involving concrete materials, such as paper, chopsticks, sewing kits, and diamond painting kits, were particularly beneficial. These activities provided repeated, staged opportunities to strengthen the small muscles of the hands while also refining eye-hand coordination.

The structured, hands-on approach allowed students to develop better control over their fine motor movements, leading to noticeable improvements in handwriting legibility. By incorporating tangible, engaging materials into fine motor training, students had more opportunities for repetitive practice in a way that felt meaningful and accessible. This research reinforces the importance of selecting activities that target motor skills and encourage motivation and engagement, especially for students with special education needs.

Handwriting Legibility Scale. As a handwriting outcome measure, the researchers used the Handwriting Legibility Scale, which I had not heard of before but found very interesting. This scale was used for pre-and post-test assessments to measure legibility based on five criteria: letter formation, sizing, spacing, line quality, and overall legibility of entire words. The results were positive for the treatment group, although the study had a small sample size.

One key takeaway from this study was the emphasis on fine motor activities that involved utensil use. In school-based therapy, therapists might be inclined to use general fine motor activities like hiding beads in therapy putty. While these activities have some benefits, they do not always address the core issue for students struggling with handwriting—utensil control. This study demonstrated that targeting fine motor skills by using different types of utensils in a precise and controlled way directly supported handwriting improvement. The connection between these functional activities and improved writing mechanics makes sense and reinforces the importance of designing interventions that align closely with students' challenges.

The Handwriting Legibility Scale also reported good reliability and validity for children ages nine to fourteen, making it a valuable tool for assessing handwriting. The study found significant differences between the handwriting of boys and girls, and the scale effectively distinguished between children with and without developmental coordination disorder. These findings suggest that the Handwriting Legibility Scale could be useful for accurately assessing and tracking handwriting progress in students with fine motor challenges.

Impact of Posture & Muscle Tone on Handwriting Success

Students with low or low-normal muscle tone, particularly those with postural weakness, often struggle with keeping their materials in place during class. They frequently drop items, and retrieving them takes extra time, causing them to fall behind in their work and miss important instructions. These small disruptions add up, making it difficult for them to stay engaged and keep up with their peers.

Educating teachers and parents about these challenges can help create better classroom strategies to support these students. One simple adjustment is using a hinged pencil box that stays open on the desk, preventing materials from rolling off. Another option is a fixed pencil holder attached to the desk, where students learn to take their pencil, use it, and return it immediately. Establishing these habits early on can make a big difference in reducing unnecessary distractions and keeping students on task.

Students with hypotonia often extend their ring and little fingers against the desk while writing to create stability. This is common among students with Down syndrome, and many parents are unaware of why their child does this. Once they understand, it makes sense, and they can better support their child’s needs. While these compensations can be helpful, some students may still struggle with their grasp. In these cases, using a claw pencil grip can provide extra support and guiding finger placement without interfering with their natural need for stability.

Postural stability is another major factor affecting writing. Students may have difficulty controlling fine motor movements if their feet are not firmly planted on the floor. Solutions can include a footrest, adjusting the desk or chair height, or allowing the student to stand while working. Standing can help students with weak core muscles stay more engaged, as long as it is not being used as a way to avoid work.

Flexible seating is becoming more common in classrooms, but not all options provide the stability needed for writing. Teachers may need guidance in determining which students benefit from certain seating choices. For example, a student struggling with posture might struggle to maintain control while writing on an exercise ball. Instead, using the ball for activities like flashcard practice or peer discussions might be a better fit, while a more stable chair is used for writing tasks.

Desk height is another important factor. Students may hike their shoulders if a desk is too high, creating tension and limiting movement. If the desk is too low, they may rest their chin on the table, which can interfere with visual acuity and handwriting accuracy. Adjusting the desk height to match the student’s posture can help reduce strain and improve writing performance.

Making small but intentional adjustments to a student’s workspace can improve their ability to focus, complete tasks efficiently, and develop better writing habits. Teachers and parents can better support students with postural and fine motor challenges by increasing awareness and providing practical solutions.

Summary

Exam Poll

1)What is the consequence of handwriting difficulties?

They can have avoidance behaviors, struggle to take notes in class and be unable to read them later. Later, they might receive lower marks due to poor legibility. All of those things can be consequences of handwriting difficulties at school.

2)What is NOT an issue that can develop from limited infant time in prone?

The answer is B. The other things can reduce palmer arch, delayed skipping or crawling, and reduced development of neck muscle control. Those can all develop from limited infant time and prone, but SIDS does not develop from that.

3)What is a method to downgrade/modify supine flexion?

Having the student complete the activity with their feet against a wall or solid furniture can provide additional stability and support. If students struggle with supine flexion, placing their feet against a stable surface like a wall or filing cabinet can help them maintain balance and engage the appropriate muscles more effectively. This modification can make the exercise more accessible while still building strength and coordination. So, for question three, the correct answer is C.

4)Which is NOT an inefficient pencil grasp pattern?

The quadrupod grasp that rests on the side of the ring finger instead of the middle finger is not considered inefficient. It still allows for an open index-thumb web space, essential for push, pull, and rotation movements. The grasp can still support efficient writing movements as long as the web space remains open and functional.

However, the inefficient grasps include the index hook, the thumb wrap, and the three-jaw chuck. These grasps limit movement and often lead to compensation through larger muscle groups, reducing fine motor efficiency. The correct answer is that a quadrupod grasp is not inefficient.

5)What does reduced fine motor control during handwriting impact?

The correct answer is all of the above. Handwriting accuracy is influenced by multiple factors, including the ability to start and stop within writing lines, the smoothness of curves, and the straightness of lines. These elements play a role in overall legibility and fine motor control, making them all important considerations in handwriting development.

Questions and Answers

What are some strategies for improving handwriting in students, particularly in grades four and up?

The best strategy depends on the underlying issue. If the primary challenge is fine motor-related, using a pencil grip or an adaptive pencil can help. Additionally, changing the writing paper—such as switching to a graph-style format—has often been an effective solution for fine motor and spacing difficulties. If the issue is more related to visual perceptual-motor development, that is a separate topic that requires further discussion.

Should students' exercises be done in sessions or assigned as homework?

Exercises in the session are used to determine the "just right challenge" for the student. The therapist identifies the student's starting point and then teaches the specific exercise to parents and teachers. The goal is to integrate the exercise into the school day or at home at an appropriate time. When the student returns, the therapist rechecks their skills to determine whether the exercise should be more challenging or adjusted to keep them engaged.

Fine motor testing is common in schools, but core strength testing is not. Is it appropriate to recommend core strength exercises?

Yes, even if the school does not explicitly assess core strength, therapists should still consider it a factor in handwriting and fine motor difficulties. While some classroom environments may not support core exercises, others—especially younger classrooms—might incorporate them into daily routines. If core exercises cannot be implemented in the school setting, working with parents to include them at home is essential. Although a school district does not include core control in reports, therapists should assess it to determine the best treatment options.

Why is it important to get parents involved in implementing core strengthening exercises at home?

In some cases, the classroom is not ideal for exercises, especially if services are only provided twice a month or schools require strictly educationally relevant interventions. Some teachers may incorporate simple exercises for the whole class, but home is the more practical setting in other cases. Getting parents on board ensures that the student receives consistent practice, which is necessary for improvement.

What interventions are recommended for students experiencing tremors during handwriting without a suspected neurological condition?

The therapist’s first approach is typically to use weighted items like pencil or wrist weight. This method often provides a quick improvement in the classroom. While core strengthening and weight-bearing activities could be beneficial, weighted tools offer more immediate results for handwriting stability.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Tompkins, K. (2025). Motor supports for handwriting development. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5784. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com