Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Navigating The Journey: OT’s Role In Oncology And Navigating End-of-Life Care, presented by Kirsten Davin OTD, OTR/L, ATP/SMS.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to compare and contrast three benefits and challenges to the inclusion of occupational therapy services in end-of-life care.

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze at least two practice guideline sources related to the provision of OT services in oncology.

- After this course, participants will be able to apply intervention to incorporate with palliative and end of life care.

Introduction

I am excited to work with you all over the next hour to discuss our role as occupational therapists in oncology, especially navigating end-of-life care.

As we start today's webinar, we're going to touch on some general information about cancer and oncology and those diagnoses. Much of what you'll get during the first portion of this webinar will be informative. I know many of you are here for the interventions, the assessments, and all the exciting things that I've put in the back half of the seminar.

Types of Cancer (Based on Cell Type)

- Carcinoma: Skin or tissues that line or cover internal organs.

- Sarcoma: Bone, cartilage, fat, muscle, blood vessels, connective and supportive tissues.

- Leukemia: Blood-forming tissues (bone marrow).

- Lymphoma and myeloma: Cells of the immune system.

- Central nervous system: Tissues of the brain and spinal cord.

As we discuss the types of cancer, you'll notice that this single slide could easily be an hour-long presentation on its own. However, the information is available for you to review at your convenience. We won't spend too much time on the elementary options because I know you're eager to move on to the assessments and interventions.

Several types of cancer are classified based on cell type. Regardless of the specific type, there's always a risk of invasion into adjacent tissues or metastasis.

TNM Cancer Staging System

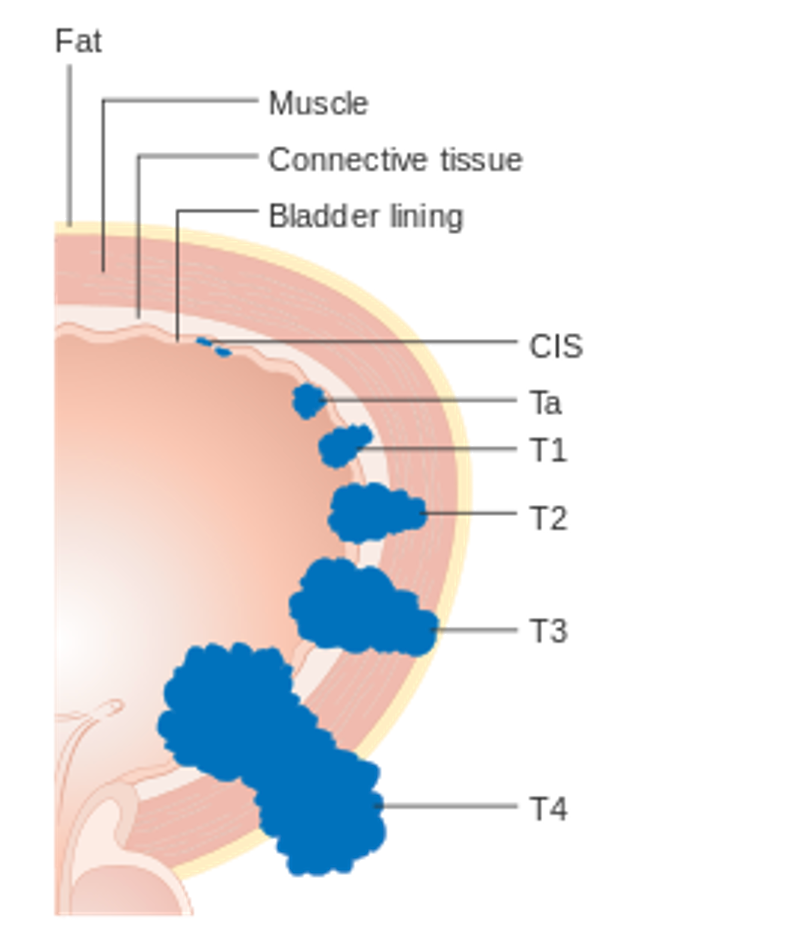

Several types of cancer staging systems exist, and the TNM Cancer Staging System is one of them (Figure 1).

Figure 1. TNM Cancer Staging System (Click here to enlarge the image).

The TNM staging system is used for many different types of cancer. The concept involves three categories: tumor, lymph node, and metastasis. The TNM system is the most widely used cancer staging system, adopted by various hospitals and medical centers to provide a comprehensive overview of the extent of the main tumor.

- TNM Classification (universal system)

- T (T1-T4): Tumor size

- N (NO-N3): Lymph node involvement

- M (MO-M1): Absence or presence of metastasis

- Staging Groups

- Stage I: T1 NO MO

- Stage II: T2 N1 MO

- Stage III: T3 N2 MO

- Stage IV: T4 N3 M1

The T portion of the TNM staging system has different classifications, ranging from no evidence of primary lesions to penetration into other organs. The N portion, which represents lymph node involvement, also has a rating system that ranges from no lymph node involvement to metastasis. If metastasis is present, it is further classified as either distant or not distant.

This system provides healthcare workers with an overview of the initial lesion and the extent of its involvement. As illustrated in Figure 2, it is crucial to understand the definitions and differences between invasion and metastasis.

Figure 2. Illustration of the TNM Cancer Staging System.

Invasion refers to the direct migration of the initial cancer occurrence into neighboring tissues, similar to an army invading another country. Cancer cells move directly from the initial tissue into adjacent tissues.

Metastasis, on the other hand, occurs when some cancer cells enter the lymphatic, blood vasculature, or circulatory systems. Once in these systems, the cancer cells can travel to other body parts. While invasion is a direct spread to neighboring tissues, metastasis involves cancer cells "hitching a ride" on the lymphatic or circulatory system, allowing them to spread to different body areas.

Common Sites of Metastasis

- Often, patterns of metastasis are identified and often predicted based on the primary

Now, some common sites of metastasis are what we see here.

Primary Site | Site of Metastasis |

Breast | Bone, lung, liver, lymph, brain, meninges |

Prostate | Bone, lung, liver, lymph |

Lung | Bone, liver, lymph, brain, meninges |

Colorectal | Liver, lung, lymph |

Bone | Lung, brain |

Metastatic cancer retains the name of the primary cancer. For example, breast cancer that starts in the breast and spreads to the lung is called metastatic breast cancer, not lung cancer. The cancer is named for the site of its original occurrence. So, if diagnosed with breast cancer and it metastasizes to the lung, it will be classified as stage IV breast cancer with metastasis to the lung, not as lung cancer.

This differentiation is crucial in healthcare. Cancer can spread to almost any part of the body, though different types are more likely to metastasize to certain areas. The most common sites of metastasis are bone, liver, lung, and sometimes brain. The list above shows these common sites of metastasis.

Cancer Treatment Options Overview

- Treatment type or a combination of treatments will often result in specific side effects which can impact function, discharge plan, caregiver needs, and more.

- Types of Cancer Treatment:

- Stem cell therapy

- Targeted therapy

- Hormone therapy

- Immunotherapy

- Chemotherapy

- Radiation therapy

- Surgery

As we proceed, we will discuss various cancer treatment options. Often, a patient will not experience just one type of cancer treatment. Instead, these treatments are frequently combined to achieve the best possible outcome. To illustrate this, I can share a personal example: my cousin was recently diagnosed with breast cancer and is undergoing a comprehensive treatment regimen. Initially, she is receiving two separate rounds of chemotherapy, followed by lumpectomies, then radiation, and finally hormone therapy. This highlights that cancer treatment is not a single-choice menu; rather, physicians often use a combination of interventions.

These combined treatments aim to achieve the best possible outcomes. However, it is important to acknowledge the wide range of side effects associated with these interventions. Patients may experience pain, fatigue, or limited endurance, especially if surgery is involved. There is also a risk of infection, blood clots, and pulmonary embolisms, which can cause swelling.

Radiation therapy, in particular, often leads to fatigue. Additionally, both radiation and certain chemotherapies can cause nausea, vomiting, skin changes, and cognitive changes. We will delve into the side effects of these treatment options in more detail shortly. It is crucial to understand that when working with a client undergoing cancer treatment, these side effects can significantly impact our interventions and the client's overall experience.

MRI Guided Radiation

Here is a link to view this technology.

Guided radiation therapy Innovations in radiation oncology are constantly occurring. Every so often, there's really a transformative change in terms of what we offer patients. MRI-guided radiotherapy technology that we are bringing into the Dana Farber Brigman Women's Cancer Center is one of those moments of transformative change.

We guide most of our radiation therapy using CT scans or simple x-ray films. CT scans are very good at imaging parts of the body, but they're not so great at imaging soft tissue tumors. The new technology with MRI guidance really allows us to see around tumors much better than we could with the CT scan.

The MRI-guided radiation therapy program at Dana Farber Brigham and Women's Cancer Center has two main components. One component is the MRI advancement procedure and simulation suite, or MAPS. And this is a high-field MRI scanner with a specialized immobilization setup to image a patient before their radiation therapy treatment, so that we can develop the most precise radiation therapy treatment plan possible. The second component is the MRI-guided linear accelerator, an MRI scanner that has been married with a radiation therapy treatment device to treat with radiation while visualizing directly in real-time, and to change and adapt our radiation therapy plan on a day-to-day basis.

Historically, planning takes us as long as three to five days. With this MRGI linear accelerator, we can actually do that in an hour. So we're able to adjust the radiation based on the conditions of the day. And the reason why that's important is that the tumors don't stay still.

The anatomy of the patient changes from day to day and second to second. As the patient breathes and the tumor moves up and down and up and down, it might move in and out of the field of radiation.

We can actually automatically have the machine turn the radiation off if the tumor moves out of the position that we want it to be in. That allows us to really make sure that within millimeters, we're treating where we want to treat. And this may allow us to give more dose safely than we would otherwise feel comfortable. Soft tissue tumors, like pancreatic tumors, liver tumors, or tumors that move a lot like lung tumors, could have potentially a very large benefit.

Right now, there's certain key cancers that we can't even treat safely. With MRI-linac, our hope is that finally we can have an answer for these really difficult to treat patients, and certainly that's going to require us to prove it by conducting clinical trials.

This degree of precision and personalization has never been available before. This is what we're here for. It's to provide the best care for the benefit of our patients, and it's the people in our department that bring all of this together.

Everybody from the front desk staff who welcomes the patient in the nursing staff, the radiation therapists, the medical dosimetrist, a really tight-knit team of people who are all doing this work in real-time.

It's been a tremendous effort. Just two decades ago, we were planning this treatment using wax crayons. Today, we're delivering these treatments with really complicated, high-tech devices. We'll be the first center in New England and around the first 20 in the world to have these new, new technologies. We're really excited to bring that into our department at the Dan Farbergree Women's Cancer Center.

What you just saw was a treatment method that isn't often discussed but can offer a significant targeted impact on cancer and the tumor. The video, courtesy of Brigham and Women's Hospital, demonstrated how MRI-guided radiation therapy can be used and highlighted some of its distinct benefits.

In recent years, along with guided radiation therapy, there have been advancements in targeted therapy options. These targeted therapies have shown promising outcomes in terms of medical and clinical responses to certain types of cancer.

How Does Targeted Therapy Work?

- Blocks signals that help cancer cells grow

- Reduces the longevity of cancer cells

- Triggers the immune system to attack cancer cells

- Cuts off supply of hormones that contribute to cancer

- Delivers cell-killing substances to cancer cells

- Stops creation of blood vessels that lead to tumors

- Destroys cancer cells

- Benefits include:

- Fewer side effects than traditional chemotherapy intervention

- Delivers a multi-faceted “attack” on cancer cells

Targeted therapy is a type of cancer treatment that specifically targets proteins that control how cancer cells grow, divide, and spread. This approach represents a significant breakthrough in recent years. Unlike traditional chemotherapy and broader radiation therapies, targeted therapies offer distinct benefits. Depending on the type of targeted therapy used, these treatments can enhance the immune system's ability to destroy cancer cells, trigger the immune system to attack specific cancer cells, and block signals that promote cancer growth, effectively starving the cancer within the patient's body. Additionally, targeted therapy can cut off the supply of hormones and blood vessels that feed tumors.

This specific approach to medical intervention allows for fewer side effects compared to traditional chemotherapy, enabling a multifaceted attack on cancer cells. For occupational therapy, the benefits of targeted therapy are particularly valuable. With reduced side effects, patients can be more active, feel better, and participate more in daily activities. As we delve into the treatment side, it's important to recognize how these advancements in targeted therapy can significantly improve the quality of life for patients undergoing cancer treatment.

Curative Vs. Palliative Care

- Curative (Therapeutic) Care

- The medical goal is to return the patient to their prior health status.

- Treatment is aimed at curative objectives.

- Palliative Care

- Goals include optimizing comfort

- Patient-centered goals

- Aid in reducing caregiver burden/offer respite

There is a distinct difference between curative and palliative care. Curative, also known as therapeutic care, refers to treatments and therapies to cure an illness or condition. When treating a patient via a curative pathway, we aim to restore them to their previous health status and level of function, allowing them to live independently once again. Curative therapies strive to provide a definitive solution to the diagnosis.

Palliative care, on the other hand, has different objectives. It is specialized medical care for individuals with serious illnesses, such as cancer. The primary goals of palliative care are to optimize comfort, provide relief from symptoms, reduce stress, and improve the quality of life for both the patient and their family. This type of care often transitions into end-of-life care when faced with a terminal diagnosis.

Implementing patient-centered and client-centered goals is crucial, but it becomes particularly significant in palliative and end-of-life situations. One essential component of palliative care is providing respite for caregivers. Caring for a loved one with cancer or a terminal illness can be incredibly challenging, and supporting caregivers with respite and care is an integral part of our approach.

As we consider how we interact with and treat the patient, it is vital to also address the well-being of the caregiver. Providing support and relief for caregivers not only helps them but also enhances the overall care and comfort of the patient.

Oncology Treatment Spectrum

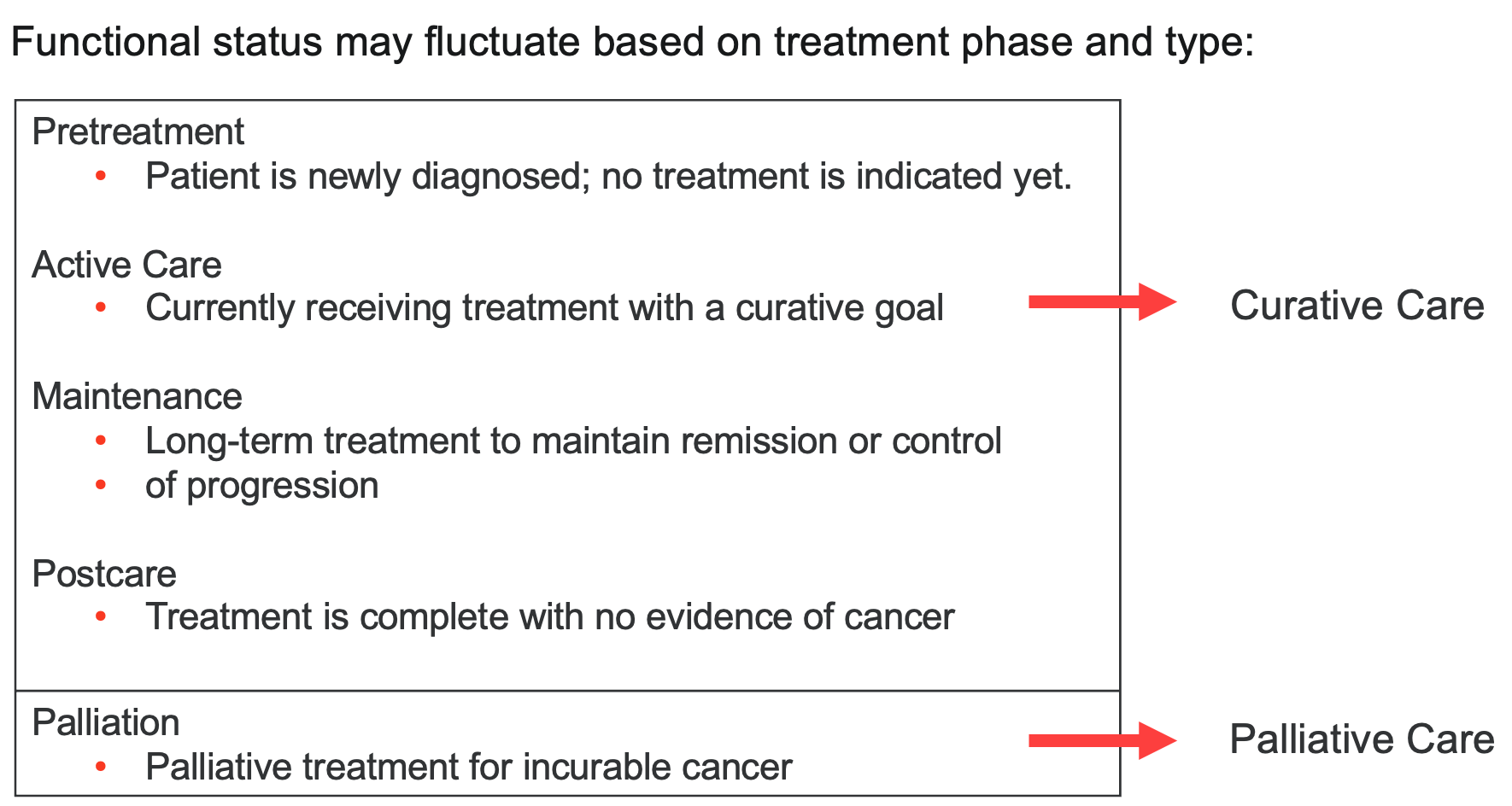

Now, here we have the oncology treatment spectrum in Figure 3.

Stubblefield & O’Dell, 2021

Figure 3. Oncology treatment spectrum (Click here to enlarge this image).

As you'll see, we just touched on two types of care: curative and palliative. Along with these two classifications, we will examine phases of treatment prior to delving into treatment interventions and assessment.

In the top portion of this discussion, you'll find curative care, which includes four subclassifications. The first is pre-treatment, where patients are newly diagnosed, and treatment has yet to begin. Once treatment has been initiated with a curative goal, the patient is considered to be under active care. This phase includes active rehabilitation efforts. Following this is the maintenance phase, during which we are in the long-term treatment range. At this stage, we may have successfully achieved our goals of getting the patient back home and relatively independent. The focus is on maintaining the level of function the patient has achieved. The final phase is post-care, which involves the completion of treatment when the cancer has been removed.

Palliation refers to the palliative section or portion of care, which pertains to individuals diagnosed with an incurable form of cancer. Palliative care focuses on optimizing comfort, providing relief from symptoms, reducing stress, and improving the quality of life for both patients and their families. This care often transitions into end-of-life care in the case of terminal diagnoses.

In summary, understanding these phases of treatment helps us better plan and implement the appropriate interventions and assessments tailored to each patient's needs and goals.

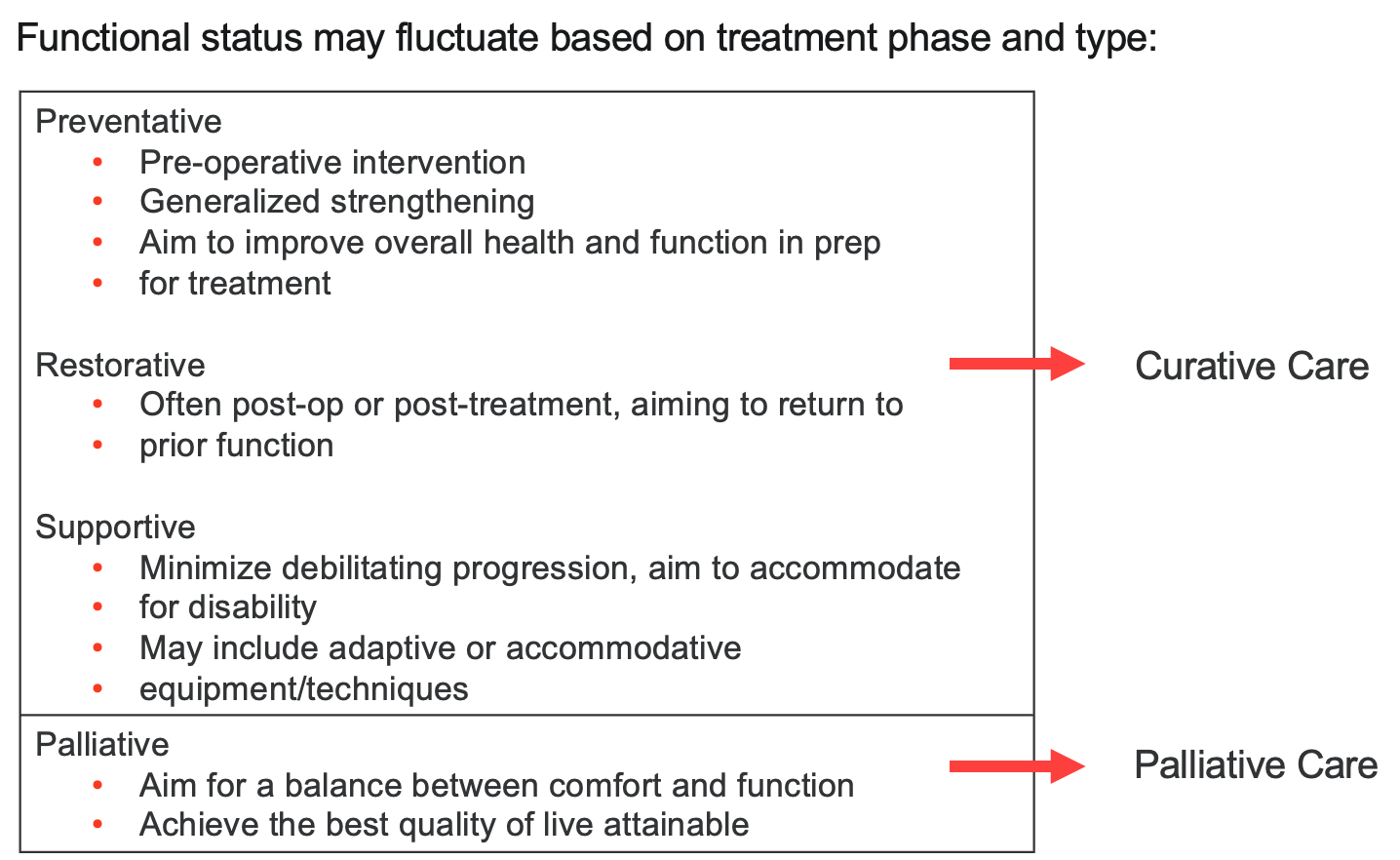

Rehabilitation Paradigms

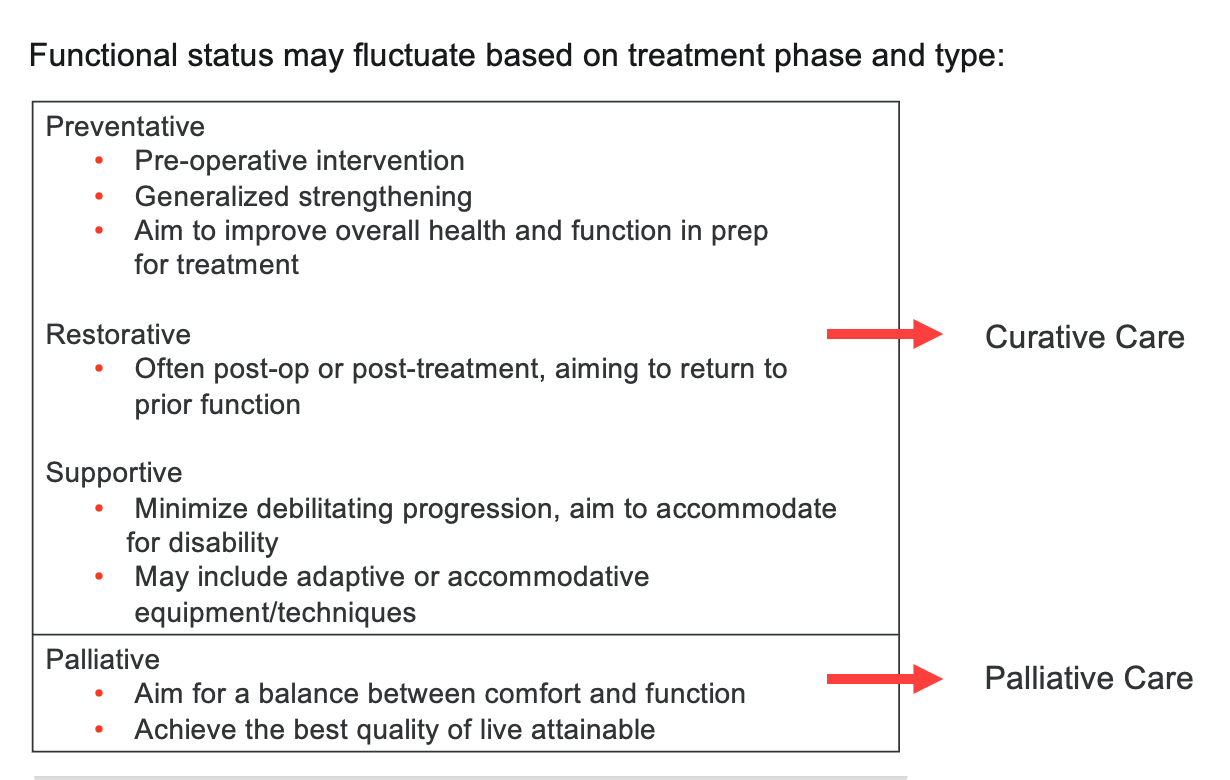

Now, we will parallel the oncology treatment spectrum with the rehab paradigm, as noted in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Rehabilitation paradigms (Click here to enlarge this image).

Functional status may fluctuate depending on what phase of treatment a patient is in and what level of care they are receiving. If we refer back to the slide on curative versus palliative care, we see that medically, patients may be newly diagnosed and in pre-treatment, undergoing active care, or in the maintenance phase where the cancer is semi-controlled. Post-care is when no more cancer is present. Palliative care intervenes with clients who have long-term cancer diagnoses and an incurable diagnosis.

For us as rehab professionals, it is crucial to align our interventions with the phase of treatment and the patient's medical status. In preventative care, we might work with clients preparing for an operation to remove tumors or undergoing a mastectomy. Therapists can be brought in to promote strengthening prior to the operation, improving overall health and function in preparation for surgery. For example, my cousin, who is currently undergoing chemotherapy in preparation for an upcoming surgery, has started preoperative therapy to build strength and endurance, promote good health habits, and get involved with therapy before the surgical intervention.

Restorative care under curative treatment often involves post-operative care with the goal of returning patients to their prior level of function. This is common in acute care settings or the ICU, where we work with clients recovering from an injury, illness, or surgery. Our primary goal is to help them regain their previous functional abilities.

Supportive care involves long-term thinking. After surgery, when patients return home, they may need long-term adaptations, equipment, or techniques like energy conservation interventions. Our focus here is to ensure they continue to progress and maintain their level of function.

In palliative care, our goal is to achieve a balance between comfort and function. We want clients to listen to their bodies and do what they can while maintaining as high a quality of life as possible. Some clients may have a list of goals they want to achieve, often referred to as a bucket list, despite their terminal diagnosis. Occupational therapy can assist with these goals, which might be as simple as making dinner for a loved one or attending a child’s ball game. We need to ask clients what they want to achieve and how we can support them in this process.

In the oncology setting, clients might need help tying up loose ends, such as completing wills. While this isn't within the scope of occupational therapy, we can refer them to appropriate services. Many clients in palliative care have a checklist of what they want to accomplish while they still can.

Overall, our rehabilitation paradigms are designed to support engagement, participation, and health, encompassing all aspects of the occupational therapy domain.

- Considerations for engagement and goals with clients who present with cancer diagnoses may look different from the traditional acute care or rehab client

Occupations | Contexts | Performance Patterns | Performance Skills | Client Factors |

•Activities of daily living (ADLs) •Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) •Health management •Rest and sleep •Education •Work Play •Leisure •Social participation | •Environmental factors •Personal factors | •Habits •Routines •Roles •Rituals | •Motor skills •Process skills •Social interaction skills | •Values, beliefs, and spirituality •Body functions •Body structures |

AOTA, 2020

This is a portion of the AOTA practice framework that I'm sure you're all very familiar with, and these are all considerations that we want to keep in mind when we get into that intervention and treatment portion.

This is a chart for your reference.

Rehabilitation Paradigms & OT | |||

Cancer Rehabilitation Paradigms

(Dietz, 1981) | Focus of Paradigm Intervention

(Dietz, 1981) | Occupational Therapy Intervention Approaches

(AOTA, 2008, pp.657-659) | Focus of Occupational Therapy Interventions

(AOTA, 2008, pp.657-659) |

•Preventative | •Preoperative education and training. •Improve general health and function. | •Prevent (disability prevention) | •To prevent the occurrence or evolution of barriers to performance in context. |

•Restorative | •Return to previous levels of function. | •Establish, restore (remediation, restoration) •Prevent (see above) | •To change client variables to establish a skill or ability that has not yet developed or to restore a skill or ability that has been impaired. |

•Supportive | •Accommodation training for existing disabilities. •Minimize potential debilitating changes. | •Modify (compensation, adaptation) •Prevent (see above) •Maintain (see below) | •To find ways to revise the current context or activity demands to support performance in the natural setting. |

•Palliative | •Best quality of life for client and family. •Balance between function and comfort. | •Maintain •Modify (see above) | •To provide the supports that will allow the client to preserve the performance capabilities that have been regained, to continue to meet the client's occupational needs, or both. •Assumption: that without continued maintenance intervention, performance would decrease, occupational needs would not be met. or both. thereby affecting health and quality of life. |

AOTA, 2012

This is from the AOTA. They've provided some guidance as to rehab paradigms and occupational therapy as it relates to oncology and occupational therapy. The AOTA has a set of practice guidelines for cancer rehabilitation with adults. It was written a few years ago and published by AOTA Press.

Practice Guidelines

- Maintain current level of function

- Prevent secondary deficits

- Modify activity demands or environments and contexts

- Provide interventions to improve performance skills and client factors

- Establish performance patterns that improve the process of engaging in occupations

If you're interested in specific practice guidelines for adults diagnosed with cancer who are undergoing cancer rehabilitation, the link in your PDF packet will take you to that resource where you can acquire more information.

Common Oncology Symptoms & Side Effects

- Pain

- Cognitive Limitations (often referred to as “Chemo-brain”)

- Fatigue

- Peripheral Neuropathy (also often associated with chemotreatment)

- Nausea/Diarrhea/Generalized Weakness

- Anxiety/Fear of the Unknown or Future

Now, let's talk about some common oncology symptoms and side effects. We'll touch on some of the more prevalent side effects and then discuss how occupational therapists can help clients remain functional and independent despite these challenges, and how we can assist in reducing the side effects.

Pain is one of the most common side effects, occurring in as many as 50% of clients undergoing cancer treatment. In the curative phase, many patients experience pain, but this prevalence often increases as individuals transition to end-of-life care. Occupational therapists, in collaboration with the healthcare team, strive to control pain as effectively as possible.

Cognitive limitations, often referred to by clients as "chemo brain," are another common side effect. Clients may describe themselves as being in a fog, feeling fuzzy, or not quite right. Some clients even say they feel like they're about five seconds behind the rest of the world. We will discuss cognitive interventions that can help alleviate these symptoms.

Fatigue is also very common, and this is where our energy conservation techniques come into play. Additionally, chemotherapy can lead to peripheral neuropathy, generalized weakness, diarrhea, and nausea. Anxiety often accompanies these symptoms, stemming from the fear of the unknown associated with a cancer diagnosis. As therapists, we can support clients by addressing their anxiety and stress, allowing them to discuss their fears, and helping them work through these emotions.

Occupational therapy has significant potential to help adults with cancer by reversing, slowing, or hopefully eliminating the disability associated with their diagnosis. By addressing the side effects and symptoms, we aim to enhance the quality of life and functional independence of our clients.

There are different types of qualifying conditions often associated with occupational therapy and oncology. These conditions provide a framework for understanding how occupational therapy can be applied to support clients throughout their cancer journey. This comprehensive approach allows therapists to tailor interventions to each patient's unique needs, ensuring the best possible outcomes in terms of function and quality of life.

Occupational Therapy in Oncology:

Needs, Conditions, and Intervention Strategies

This is a general overview of interventions that are oftentimes provided by OT.

Qualifying conditions | Types of interventions provided by an occupational therapist |

ADL/IADL limitation | ADL/IADL self-care, functional activity participation, therapeutic exercise, durable medical equipment recommendations |

Debility, fatigue, poor endurance | Therapeutic exercise, ADL/IADL self-care, functional activity participation, durable medical equipment recommendations, energy conservation |

Neuropathy | Neuromuscular re-education, ADL/IADL self-care, therapeutic activity, therapeutic exercise, manual therapy, durable medical equipment recommendations |

Lymphedema | Manual therapy, ADL/IADL self-care, functional activity participation |

Cognitive decline | Cognitive therapy, ADL/IADL self-care, functional activity participation |

Upper extremity impairment | ADL/IADL self-care management, neuromuscular re-education, functional activity participation, therapeutic exercise, manual therapy |

Balance | ADL/IADL self-care management, neuromuscular re-education, functional activity participation, therapeutic exercise, durable medical equipment recommendations |

Pain | Functional activity participation, ADL/IADL self-care management, therapeutic exercise, durable medical equipment recommendations |

Abbreviations: ADL, activity of daily living; IADL, instrumental activity of daily living. | |

Table Source: Pergolotti, 2016

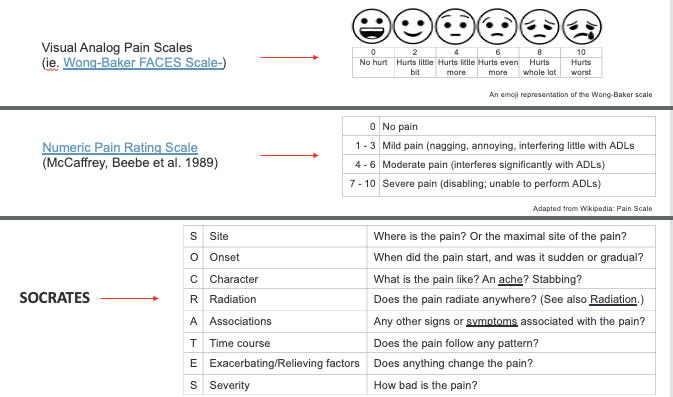

Pain Assessment

- Subjective Rating of Experience (Self-report)

- Visual Analog Scales (various types)

- Numeric Pain Scales

- SOCRATES

- Brief Pain Inventory

- …more!

- Quantitative Signs on Physical Exam (Therapist observation/scoring)

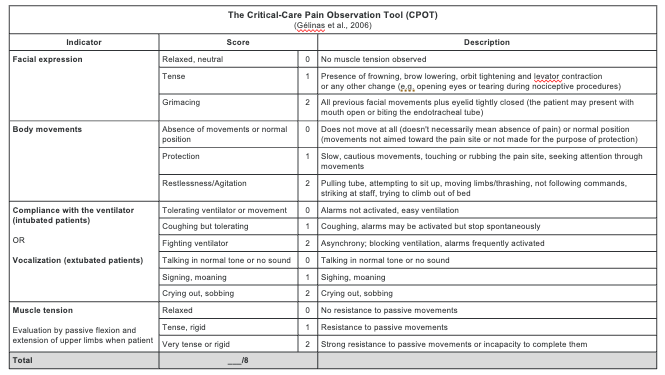

- Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT)

As we discussed, pain assessment is often significant in cancer patients. Pain assessment falls into two different categories: a subjective rating of experience, which is how the patient reports their pain level, and a quantitative rating.

This is how we observe their pain level (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Subjective rating of pain (Click here to enlarge image).

When performing a pain assessment, it is crucial to consider both subjective and quantitative aspects. A subjective experience rating is a self-report where the patient describes their pain. Some common tools for subjective pain ratings include the Wong-Baker FACES scale, the Numeric Pain Rating Scale, and Socrates.

The Wong-Baker FACES scale uses facial expressions to help patients, especially children, communicate their pain levels. The Numeric Pain Rating Scale asks patients to rate their pain from 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain imaginable. Socrates provides a comprehensive view of the pain by evaluating the site, onset, character, radiation, associations, time course, exacerbating and relieving factors, and severity. These tools help us understand how the patient feels and the impact of pain on their daily life.

For quantitative signs observed during a physical exam, the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) is commonly used and shown in Figure 6. CPOT assesses pain based on clinical indicators such as facial expressions, body movements, muscle tension, compliance with the ventilator for intubated patients, and vocalization for extubated patients. These objective measures complement the subjective reports, providing a well-rounded picture of the patient's pain experience.

Figure 6. The Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT)(Click here to enlarge this image).

The Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) evaluates pain through four main dimensions: facial expression, body movement, vocalization (or compliance with the ventilator if the patient is intubated), and muscle tension. This rating scale allows healthcare professionals to observe and assess pain levels from an external perspective. By using CPOT, clinicians can identify pain indicators that might not be verbally expressed by the patient.

Often, subjective and quantitative assessments are used together to gain a comprehensive understanding of the patient's pain experience. For example, combining self-reported pain levels with CPOT observations ensures a more accurate assessment.

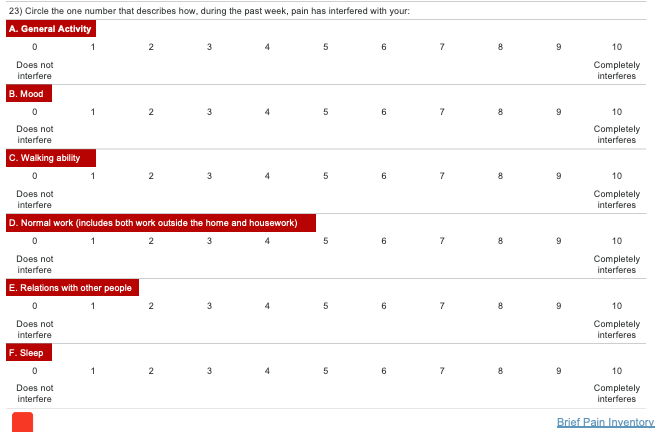

Another useful tool is the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), which comes in both long and short versions. The shorter version consists of twelve items that assess pain based on physical intervention and impact on daily activities. The BPI helps in understanding the severity of pain and its interference with the patient's functional abilities.

By utilizing tools like CPOT and the Brief Pain Inventory, occupational therapists and other healthcare professionals can better tailor their interventions to manage pain effectively and improve the patient’s quality of life.

Figure 7. Brief Pain Inventory (Click here to enlarge the image).

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) asks clients to identify how their pain has affected various aspects of their lives over the past week. Specifically, it inquires whether pain has limited their ability to walk, perform normal work such as housework or self-care, and impact their sleep, mood, or relationships with others. This comprehensive approach aligns closely with occupational therapy principles because it not only assesses the intensity of the pain but also evaluates its broader impact on daily functioning and quality of life.

By asking about the effects of pain on schoolwork, home life, regular work, and mobility, the BPI provides valuable insights into how pain interferes with essential activities. This holistic perspective is particularly useful for occupational therapists, who aim to enhance clients' overall well-being and functional independence. The BPI's focus on both pain and its consequences makes it a highly suitable tool for occupational therapy assessments, offering a detailed understanding of the challenges clients face and helping to inform effective intervention strategies.

Treatment Considerations

- Physical Intervention

- Soft tissue mobilization

- Modalities intervention

- Postural education

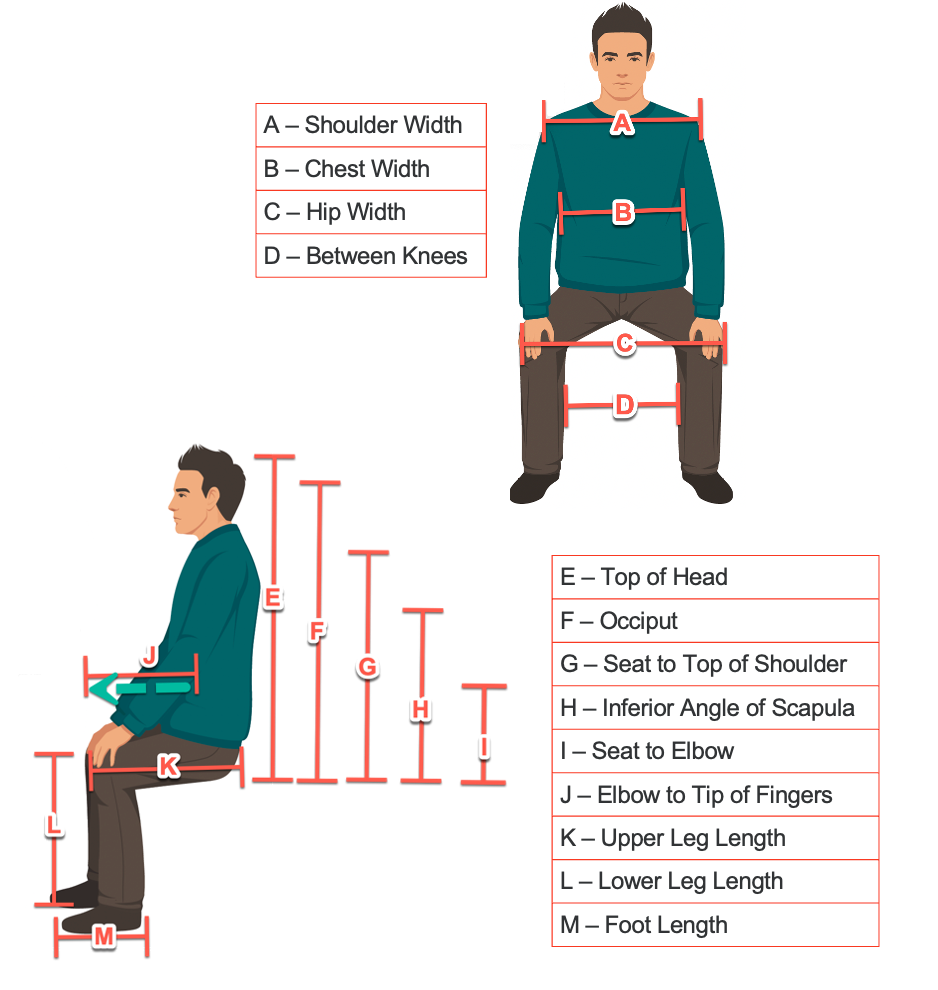

- Wheelchair seating/positioning

- Ergonomic assessment

- Functional/purposeful activities

- Psychosocial Intervention

- Anxiety management

- Identification of triggers

- Environmental Intervention

- Bed, recliner, etc. use

- Home access

We also need to consider various treatment options for managing pain. Physical interventions can include modalities such as heat, cold, and electrical stimulation. Postural education is another critical aspect, as proper posture can significantly impact pain levels, respiratory capacity, sitting tolerance, and overall activity levels.

Wheelchair seating is particularly important in managing pain for individuals who rely on wheelchairs for mobility. Proper seating can alleviate discomfort and prevent secondary complications. While we won't delve into the complexities of wheelchair seating here, it's essential to recognize its importance.

Maintaining good posture is crucial for reducing pain and enhancing overall function. By ensuring that clients have proper posture, we can help them improve their respiratory capacity, increase sitting tolerance, and engage more comfortably in daily activities. This holistic approach to pain management supports clients in achieving better health and functional outcomes.

Figure 8. Postural seating considerations.

We also want to think about psychosocial intervention. Can we help manage anxiety to help reduce pain? And also environmental intervention as well?

How do they look in bed? How do they look in the recliner? How's their home access? All of those can impact that pain rating scale. Also, another significant side effect can be cognition.

Cognitive Assessment

- Top-Down Approach

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

- The Barthel Index

- …more!

- Bottom-Up Approach

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

- …more!

Some cognitive assessments, commonly referred to as chemo brain (a term I'm personally not fond of, but frequently used in the industry), can be approached in a couple of different ways. In occupational therapy, we use both a top-down and a bottom-up approach to cognitive assessment.

The top-down approach focuses on the patient's engagement in activities. It looks at the broader picture: what activities can the patient perform, what meaningful activities are they participating in, and how does cognition affect these activities? This approach emphasizes the patient's overall functional performance and participation in daily life.

The bottom-up approach, on the other hand, focuses more on performance skills and client factors. It assesses what cognitive skills the patient can perform from the ground up. This approach is more of a skill check, evaluating specific cognitive abilities such as memory, attention, and problem-solving.

Both approaches have their roles and can be beneficial in different contexts. The top-down approach helps us understand the impact of cognitive impairments on the patient's daily activities, while the bottom-up approach provides a detailed assessment of specific cognitive skills. I'll provide some assessment options for both approaches to ensure a comprehensive evaluation of cognitive function.

Cognitive Limitations

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches

- Top-Down Approach

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

- The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure is an evidence-based outcome measure designed to capture a client’s self-perception of performance in everyday living, over time. Originally published in 1991, it is used in over 40 countries and has been translated into more than 40 languages.

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

For assessing cognitive limitations, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) is often a valuable tool. The COPM is widely used and well-regarded for its client-centered approach. It helps identify and prioritize everyday issues that restrict participation, allowing individuals to assess and share how their cognitive status affects their daily lives. The COPM evaluates the impact of cognition on self-care, leisure activities, productivity at work or school, and overall participation in daily activities. You can find more information about the COPM in the provided PDF link.

The Barthel Index is another useful tool for a top-down approach. It serves as an outcome measure to score performance in activities of daily living (ADLs) and mobility. The Barthel Index, which is very occupational therapy-based, includes ten items, each scored as either 10 (fully independent) or 0 (fully dependent). This tool provides a clear picture of a client's functional abilities and areas needing support.

Both the COPM and the Barthel Index are effective in assessing cognitive limitations and their impact on daily functioning. This allows therapists to tailor interventions to the client's specific needs and goals.

- Top-Down Approach

The Barthel index is helpful because it allows us to delineate the level of assistance that the clients need to accomplish daily self-care and some mobility concepts as well.

The Barthel Index | |

Activity | Score |

FEEDING •0 = unable •5 = needs help cutting, spreading butter, etc., or requires modified diet •10 = independent |

|

BATHING •0 = dependent •5 = independent (or in shower) |

|

GROOMING •0 = needs to help with personal care •5 = independent face/hair/teeth/shaving (implements provided) |

|

DRESSING •0 = dependent •5 = needs help but can do about half unaided •10 = independent (including buttons, zips, laces, etc.) |

|

BOWELS •0 = incontinent (or needs to be given enemas) •5 = occasional accident •10 = continent |

|

BLADDER •0 = incontinent, or catheterized and unable to manage alone •5 = occasional accident •10 = continent |

|

TOILET USE •0 = dependent •5 = needs some help, but can do something alone •10 = independent (on and off, dressing, wiping) |

|

TRANSFERS (BED TO CHAIR AND BACK) •0 = unable, no sitting balance •5 = major help (one or two people, physical), can sit •10 = minor help (verbal or physical) •15 = independent |

|

MOBILITY (ON LEVEL SURFACES) •0 = immobile or < 50 yards •5 = wheelchair independent, including corners, > 50 yards •10 = walks with help of one person (verbal or physical) > 50 yards •15 = independent (but may use any aid; for example, stick) > 50 yards |

|

STAIRS •0 = unable •5 = needs help (verbal, physical, carrying aid) •10 = independent |

|

TOTAL (0-100): ______ | |

- Bottoms-Up Approach

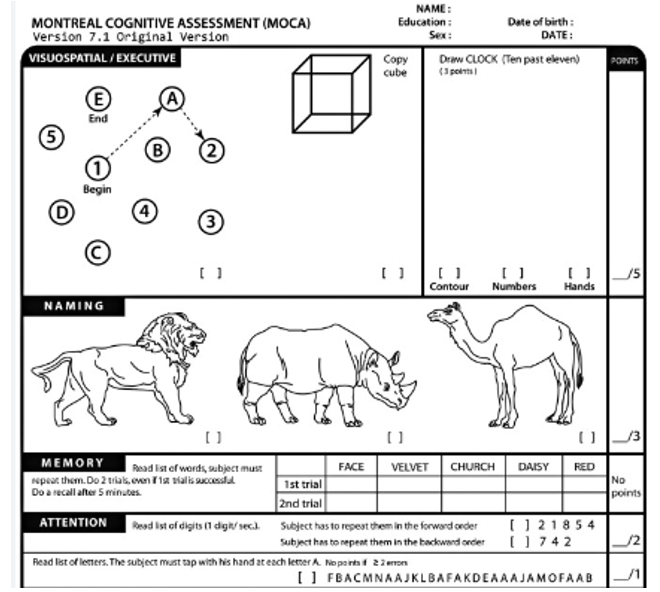

You have probably seen the MOCA, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. This is a bottom-up approach based on a score of 30 (Figure 9).

Figure 9. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is another tool that takes about ten to twelve minutes to complete and examines seven different domains. These domains include executive function, naming, language, abstraction, memory, attention, and orientation. The MoCA focuses on specific cognitive skills rather than taking a holistic approach.

For example, the MoCA might ask you to remember and recall three words after a few minutes, assess your ability to name objects or evaluate your attention through various tasks. This detailed examination allows us to understand the finer aspects of cognitive function, such as memory retention and attention span, providing a thorough assessment of cognitive abilities.

- Bottom-Up Approach

- The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)

- A Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a set of 11 questions that doctors and other healthcare professionals commonly use to check for cognitive impairment (problems with thinking, communication, understanding, and memory).

- Orientation to time and place

- Attention/concentration

- Short-term memory (recall)

- Language skills

- Visuospatial abilities

- Ability to understand and follow instructions

- A Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a set of 11 questions that doctors and other healthcare professionals commonly use to check for cognitive impairment (problems with thinking, communication, understanding, and memory).

- The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)

Along with the Barthel Index, the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) also looks for some small skill sets. It's a set of eleven questions that can be used to address orientation, attention, short-term memory, recall, and visual-spatial abilities.

Treatment Considerations

- Cognitive Rehabilitation Intervention

- Computer-based attention training

- Activities to remediate cognitive loss

- Traditional cognitive re-education techniques

- Caregiver Support

- Family/caregiver training to support patient

- Outside assistance to ensure caregiver health and respite

- Environmental Intervention

- Medication reminders

- Visual cues to execute ADL tasks

When considering treatment for cognitive limitations in clients undergoing chemotherapy, it's important to remember that these cognitive side effects are often short-term. Unlike conditions such as stroke or dementia, the cognitive impact from chemotherapy may only last for the duration of the treatment, typically a few months. This should be taken into account when planning treatment interventions for cognition.

There are various computer-based attention training options available that can be easily assigned as homework for clients. These activities, which can be done on a tablet or laptop at home, are designed to improve attention and help remediate cognitive loss or fogginess. These exercises are similar to traditional cognitive re-education techniques, providing structured tasks to enhance cognitive function.

Caregiver support is also crucial. Assessing how the family and caregivers are managing, especially if they lack a robust support system, is important. Outside assistance or respite care may be necessary to support both the patient and their caregiver. Ensuring caregivers have the resources and support they need can improve overall care and reduce stress.

Environmental interventions can also play a significant role. Clients with cognitive limitations may still be able to live at home with a few adaptations. Medication reminders, visual cues for daily tasks, and assistive technologies like pill organizers and reminder systems can help manage cognitive deficits. These tools can make a significant difference in maintaining independence and ensuring safety in the home environment.

By combining cognitive training exercises, caregiver support, and environmental adaptations, we can create a comprehensive approach to managing cognitive limitations in clients undergoing chemotherapy, enhancing their quality of life and functional independence.

Fatigue Considerations

- Causes of cancer-related fatigue

- Cancer itself

- Cancer treatments

- Pain

- Anemia

- Fatigue before treatment

- Other medical problems

- Lack of physical activity

- Nutrition problems

- Medications

- Emotional distress

- Sleep problems

Fatigue is the most common symptom associated with patients who are experiencing cancer diagnoses. Oftentimes, patients will refer to fatigue as distressing, persistent, and many times, it's a frustration for them because they feel like they want to go and do these things, but they're just so tired all the time. They just can't. They just can't do it. Cancer-related fatigue can affect up to 75% of the clientele who are undergoing cancer treatment.

This is something very important that we do need to address. A lot of times in healthcare, the message that the patient may get is, well, your body is going through a lot right now. Yes, you'll probably feel tired, but as occupational therapists, let's dig a little deeper. What can we do to help with that fatigue? How can we intervene with that fatigue and allow them to have a better quality of life?

Cancer-Related Fatigue Assessment

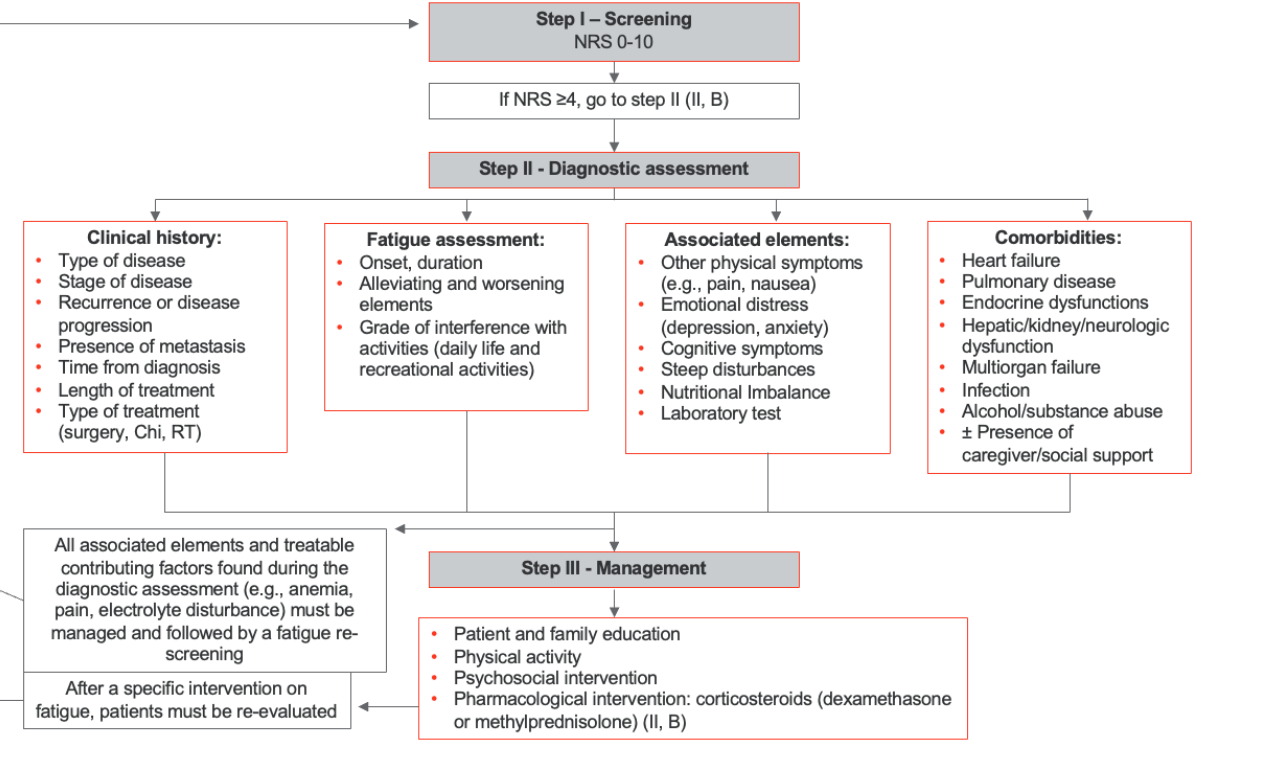

In terms of assessment, there is a screening tool called the Cancer-Related Fatigue Assessment (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Cancer-Related Fatigue Assessment (Click here to enlarge the image). Resource: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32173483/

This screening will identify the degree of cancer-related fatigue and give some suggestions for intervention and management.

MFI® Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory

The MFI, the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, is a 20-item scale designed to assess dimensions of fatigue, including general fatigue, physical fatigue, lack of or reduced motivation, reduced activity, and mental fatigue.

MFI® MULTIDIMENSIONAL FATIGUE INVENTORY ® E. Smets, B.Garssen, B. Bonke. | ||||||||

Instructions: •By means of the following statements, we would like to get an idea of how you have been feeling lately. •There is, for example, the statement: "I FEEL RELAXED" •If you think that this is entirely true, that indeed you have been feeling relaxed lately, please, place an X in the extreme left box; like this: yes, that is true ☒1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5 no, that is not true •The more you disagree with the statement, the more you can place an X in the direction of "no, that is not true". Please do not miss out a statement and place only one X in a box for each statement. | ||||||||

| I feel fit. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| Physically, I feel only able to do a little. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I feel very active. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I feel like doing all sorts of nice things. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I feel tired. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I think I do a lot in a day. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| When I am doing something, I can keep my thoughts on it. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| Physically I can take a lot. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I dread having to do things. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I think I do very little in a day. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I can concentrate well. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I am rested. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| It takes a lot of effort to concentrate on things. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| Physically I feel I am in a bad condition. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I have a lot of plans. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I tire easily. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I get little done. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| I don’t feel like doing anything. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| My thoughts easily wander. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

| Physically I feel I am in an excellent condition. | Yes, that is true. | q1 | q2 | q3 | q4 | q5 | No, that is not true. |

As occupational therapy practitioners, we understand that there are various types of fatigue. Physical fatigue, for instance, can occur after activities like jogging a mile, leaving one tired due to the physical exertion. On the other hand, sitting through a six-hour Zoom class can result in mental fatigue. We recognize these different tiers and types of fatigue, and it’s essential to address them appropriately.

The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) is an effective tool for assessing these diverse aspects of fatigue. The MFI evaluates five dimensions: physical fatigue, lack of motivation, reduced activity, mental fatigue, and more. This comprehensive assessment allows us to identify the specific areas where fatigue impacts our clients, enabling us to tailor interventions that address each type of fatigue and improve overall quality of life.

Brief Fatigue Inventory

Another fatigue assessment option is the Brief Fatigue Inventory.

Brief Fatigue Inventory | ||||||||||

Throughout our lives, most of us have times when we feel very tired or fatigued. Have you felt unusually tired or fatigued in the last week? Yes ☐ No ☐ | ||||||||||

1. Please rate your fatigue (weariness, tiredness) by circling the one number that best describes your fatigue right NOW. | ||||||||||

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

No Fatigue |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| As bad as you can imagine |

2. Please rate your fatigue (weariness, tiredness) by circling the one number that best describes your USUAL level of fatigue during past 24 hours. | ||||||||||

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

No Fatigue |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| As bad as you can imagine |

3. Please rate your fatigue (weariness, tiredness) by circling the number that best describes your WORST level of fatigue during past 24 hours. | ||||||||||

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

No Fatigue |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| As bad as you can imagine |

4. Circle the one number that describes how, during the past 24 hours, fatigue has interfered with your: | ||||||||||

A. General Activity | ||||||||||

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Does not interfere |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Completely interferes |

B. Mood | ||||||||||

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Does not interfere |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Completely interferes |

C. Walking ability | ||||||||||

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Does not interfere |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Completely interferes |

D. Normal work (includes both work outside the home and daily chores) | ||||||||||

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Does not interfere |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Completely interferes |

E. Relations with other people | ||||||||||

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Does not interfere |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Completely interferes |

F. Enjoyment of life | ||||||||||

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Does not interfere |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Completely interferes |

The brief fatigue inventory is used to rapidly assess the severity and impact of cancer-related fatigue. So, this is a very quick assessment. Many times, this is used at the beginning of a session with occupational therapy or with a healthcare provider. There are essentially several options that the client will rate, ranging from zero, having no fatigue, up to ten, where the fatigue is as bad as they could imagine it to be.

Treatment Considerations

- Client-Centered Holistic Approach

- Medical consultation (i.e. labs, pharmacological approaches)

- Aim for restorative vs compensatory techniques

- Methods to improve quality of life

- Exercise/Strengthening

- Exercises, graded activities

- Increase activity

- Incorporate exercise in function, desirable activities

- Exercise for stamina and atrophy

- Environmental/Social Intervention

- Home assessment for safety and energy conservation

- Consider social supports, opportunities

Now, let's consider treatment considerations for fatigue. When working with clients who present with oncology-related diagnoses, we want to take a client-centered and holistic approach. Fatigue can have multiple causes, so we need to think broadly. Could the fatigue be due to medication? Is it a side effect of the treatment they are receiving? Is it the impact of cancer on their body or a physiological response?

We need to consider whether the healthcare team can adjust anything to alleviate fatigue. For example, if a patient's pain medication schedule causes fatigue throughout the day, could we find an alternative pain control option that allows them to be more awake and alert during the day? Evaluating and potentially adjusting pharmacological approaches is crucial.

For physical fatigue, we should consider exercises and grading activities. Breaking down daily activities, creating schedules, and identifying times of the day when the patient is less fatigued can help. We might move important activities to times when the patient has more energy and spread out physician appointments to avoid overwhelming them with multiple visits in a single day.

Environmental and social interventions are also important. Home safety and energy conservation are key for clients experiencing extreme fatigue. A home health occupational therapy evaluation can be very beneficial. This evaluation allows an occupational therapy practitioner (OTP) to assess the home environment and suggest changes that can save energy and improve safety. For instance, moving frequently used items like dishes from a top shelf to a counter can reduce the need for repetitive reaching motions, conserving the client's energy.

As OTPs, we can improve the home environment through assessments and interventions that enhance safety and energy conservation, ultimately supporting the patient's overall well-being.

OT Energy Conservation

Elevate OT Energy Conservation Pack – Energy Conservation Prioritizing

- Step 1: Create a list of all the things you have to do. Include items you need to do today or in the near future.

- Step 2: Rate each item and give them each a total score.

- How important? Rate 0-10.

- 0 = not important

- 10 = very important

- How urgent? Rate 0-10.

- 0 = not urgent

- 10 = very urgent

- Add up for total score

- How important? Rate 0-10.

- Step 3: List your tasks/activities in order of their score.

- Consider avoiding or having someone do tasks with a low score and use your energy elsewhere.

- Step 4: Get things done.

- Focus your peak energies on activities with the highest scores; they are your priorities.

There is an OT energy conservation pack for OTPs to look at. It has many great energy conservation activities, assessments, and tactics.

Rehabilitation Paradigms

We've seen this slide before, so we're not going to spend a lot of time on it. I want to focus on the transition into palliative care.

Figure 11. The different paradigms (Stubblefield & O’Dell, 2021).

Palliative care is for those who have been diagnosed with a condition where curative treatment is not an option. For those of us working with clients who have received a terminal diagnosis related to cancer, we need to shift our thinking accordingly.

The goals for someone on a curative or therapeutic pathway typically focus on regaining function, returning home independently, and resuming work, school, or other activities they performed before the diagnosis. However, in palliative care, our approach and goals will differ significantly, emphasizing comfort, quality of life, and supporting the client in achieving their personal wishes and priorities during this time.

Palliative Care Pathway

- OT goals with a client in palliative care are often different than those who are within the Curative Pathway.

- Aim of OT Goals in Palliative Care

- Provide opportunities to enhance the quality of life for the client

- Consider quality of life and/or necessary respite for family/caregivers

- Attempt to achieve a balance between function/desires and comfort

- Ensure client-centered care

- Direct intervention to what is important to the client

- If appropriate, assist with end-of-life preparation (i.e. to-dos per client)

The goals of the palliative pathway might include spending more time with a spouse or a child. Another goal might be being able to get out of bed and sit in a chair comfortably—where comfort is key—but it's not just about the ability to do it but being able to tolerate it. I've had patients whose goals included writing letters to family and friends or completing end-of-life care wishes.

I've also worked with patients on funeral planning and referred them to professionals for estate management at their request. As we transition to the palliative care pathway, our services should focus on what is most important to the patient or client. We need to understand what they want to do and what they feel they need to accomplish as part of their end-of-life transition. This client-centered approach ensures that our interventions align with their personal goals and provide meaningful support during this time.

Palliative Care: Treatment Considerations for End-of-Life Care

- American OT Association offers guidance for OT’s role in end-of-life care.

- Role of Occupational Therapy in End-of-Life Care

- The purpose of this statement is to describe the role of occupational therapy practitioners in providing services to clients who are living with terminal conditions and are at the end of life as well as practitioners' role in providing services and support to client caregivers. This statement also serves as a resource for occupational therapy practitioners, hospice and palliative care programs, policymakers, funding sources, and clients and caregivers who receive hospice and palliative care services.

- Occupational therapy practitioners provide skilled intervention to improve quality of life by facilitating engagement in daily occupations throughout the entire life course, including end-of-life. Participation in meaningful life occupations continues to be as important at the end of life as it is at earlier stages.

- Palliative and Hospice Care

- The term end-of-life care encompasses both palliative and hospice care that can occur during the final stages of life. Palliative and hospice care are closely related. Both approaches are directed toward providing intervention services to those with life-threatening illnesses and their caregivers.

- Palliative Care

- The World Health Organization (2016, para. 1) defines palliative care as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness. Palliative care focuses on the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems.

- Palliative care differs from hospice care in that palliative care can be initiated at any point in the client's illness, whereas hospice is reserved for the terminal stage of the client's condition (Baxter et al., 2014). Curative care interventions may be used within the context of the palliative approach, whereas curative services are not provided when a client is receiving hospice care. A client simultaneously receiving palliative and curative services may transition to a hospice service when curative therapies are no longer appropriate or desired and the end of life is more imminent.

- Hospice Care

- Hospice encompasses a philosophy of care for individuals of any age with life-limiting illnesses for whom further curative measures are no longer desired or appropriate.

- Role of Occupational Therapy in End-of-Life Care

The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) offers excellent guidance for occupational therapists working in end-of-life care. On AOTA's website, there is a comprehensive section dedicated to our role in end-of-life care, including treatment options and intervention considerations. Occupational therapy holds distinct value in this area because we can facilitate quality of life for our clients, a concept we are always focused on.

While we typically think about quality of life in terms of promoting independence, in end-of-life care, it may not be about independence but about comfort, fulfillment, and achieving personal goals. Our role involves understanding what matters most to the client and tailoring our interventions to enhance their well-being and support their wishes during this critical time.

- Dual Focus – Living & Dying

- Goals may include sharing a final family meal, preparing a meal/favorite dish

- Preparing for an upcoming holiday, wedding, etc.

- Letters to family members

- Occupational Therapy Considerations

- Facilitate a death experience with closure and peacefulness for the patient and family

- Consider environmental factors (ie. accessibility, family training, social support)

- Consider personal factors such as anxiety

- Identify especially meaningful occupations rather than rote rehabilitation

- Consider benefits to outdoors, outside of home/hospital activities

- Spirituality if appropriate

The AOTA notes that OT practitioners have a distinct value in end-of-life care for clients and their caregivers through engagement in meaningful occupations during the client's remaining days. Our role in palliative care involves a dual focus: living and dying. This means addressing clients' goals that range from writing letters to making it to an upcoming holiday or attending a significant event like a wedding, perhaps even walking down the aisle.

In occupational therapy, we need to consider what end-of-life care means to the client. This might involve facilitating experiences that offer closure and peace for both the patient and their family. Environmental factors are critical; if a client wishes to stay at home during this process, we should support them by ensuring they have the proper social support and equipment to fulfill that desire.

Personal factors such as anxiety and pain control are also essential considerations. If spirituality is important to the client, we should integrate that into our care plan. We need to focus on meaningful occupations rather than routine rehabilitation tasks. For example, instead of activities like washing windows or doing laundry, we should prioritize tasks that the client finds truly important, such as going through files or looking at family photos.

Additionally, the benefits of being outside cannot be underestimated. Being confined to a single room for an extended period can be monotonous and depressing. A change of scenery, such as a car ride to a favorite place, sitting on the porch, or enjoying a milkshake from a beloved restaurant, can greatly enhance the client's quality of life. Occupational therapists should think creatively about these non-traditional rehabilitation activities to support the client's desires and well-being during their end-of-life journey.

Case Study (AOTA 2016)

Case #1

- Case Description

- Gertrude, an 80-year-old grandmother with 11 supportive grandchildren, moved into a hospice facility after a significant decline in her physical status.

- The hospice team was concerned about her refusal to follow the pain medication regimen and requested an occupational therapy referral to address strategies for pain management.

- Occupational Therapy Interventions

- After talking to Gertrude, the OT determined that Gertrude avoided taking her pain medication because she was afraid of having slurred speech and being confused and lethargic, symptoms that might frighten her. grandchildren when they visited. Although without pain medications, she was alert when her grandchildren visited, her pain limited her ability to enjoy these visits and to participate in other activities that were important to her.

- The OT recommended changes in Gertrude's daily routines to accommodate her desired roles, meaningful occupations, and pain management needs.

- The OT facilitated the collaboration of the hospice team. Together, they worked with Gertrude and her family to develop a modified visitation and medication schedule so that family visits were not occurring at times when the medication's effects on Gertrude's alertness were most intense.

- Outcomes

- With her anxiety about frightening her grandchildren lessened, Gertrude was more agreeable to taking her medications regularly.

- The resulting effective management of her pain allowed her to increase involvement in valued occupations and to maintain her role as a loving grandmother.

Case Study #2

- Case Description

- Levi was a 6-year-old boy with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. He and his younger sister were the second family for his parents, who both had children in their teens and 20s. He was an avid soccer player, coached by an older brother with whom he shared a close relationship.

- Levi was remarkably aware of his health problems and at times appeared to support his family's understanding. At age 6, with limited awareness of what life could otherwise hold for him, Levi was not burdened with the anticipatory losses his parents and older siblings experienced.

- He was hospitalized for the third time for additional treatment. His room was set up. with an additional bed and cot for family members to share the space and a room just outside his for a communal gathering space for families on the unit.

- His medical team believed there was no further curative treatments to offer him, and so he was transferred to hospice and palliative care services. Occupational therapy was called in help develop a transition plan home for continued life engagement within his abilities.

- Occupational Therapy Interventions

- After talking with Levi and his parents, the OT brought the larger family together to discuss what they felt was important to their occupations with Levi.

- Creating fun and energy was something they all enjoyed around Levi. Stories of him running "like a terror" through the house since toddlerhood and his inquisitive nature ("always snooping," joked an older sister) created the background for the plan.

- The parents' first-floor bedroom transitioned to "command central" for his medical needs and rest. Although he could not go to soccer games, Levi could help his brother/coach develop "game plans," enjoying the new title of special coaching assistant.

- The OT provided information about special hours at the Science Museum for children with special needs. It was arranged for him to visit early in the day, before other visitors arrived, and while the staff were working on installing a new early bird life exhibit. He became a favorite of the staff who continued to send him updates on their diorama and exhibit. He offered "Levi ideas" on a regular basis, many of which found their way into the display.

- As his health worsened and Levi was more fatigued, his OT helped the family modify family activities, eliminating extra burden on Levi but keeping the focus on fun and energy.

- In his insightful way, Levi asked the family to attend his soccer team's championship game, asking that a nursing friend of the family watch him while they go. It was as though he was letting them know they would and could still have fun without him.

- Outcomes

- Levi and his family enjoyed continuing the occupations that mattered to them, although in a modified manner.

- They continued to give him a choice in what he wanted to do, including having him attend his little sister's dance recital through FaceTime on his parent's phone.

- His pain and fatigue were well managed by his care team, giving hope to the family that his dying would not be too difficult for him and for them. Levi's father remarked on how his son seemed so connected to his family and his dying process. "It is as if he is caring for us."

- Levi died just after his 7th birthday, with new friends, new experiences, and renewed hope for his family.

The AOTA has provided some valuable case studies for us to reference. These case studies include descriptions of individuals, with one focusing on an older individual and the other on a younger individual. Each case study discusses the individual's background, the OT intervention implemented, and the outcomes achieved.

While we won't go through these case studies line by line, they serve as a helpful resource to understand the role of occupational therapy in cancer intervention. By examining these case studies, you can gain insights into how OT practitioners can support clients with cancer through tailored interventions that address their unique needs and goals. These examples from the AOTA illustrate the impact of occupational therapy on improving quality of life and facilitating meaningful participation in daily activities for clients undergoing cancer treatment.

Summary

Our goals today were to compare and contrast three benefits and challenges of including occupational therapy in end-of-life care, analyze a couple of practice guideline resources, and discuss the application of interventions in palliative and end-of-life care.

You have several resources from the AOTA to review after the class. These resources will help you better understand how to incorporate occupational therapy interventions effectively in palliative and end-of-life care settings. By achieving these learning outcomes, you'll be better equipped to support clients through holistic and client-centered approaches during their end-of-life journey.

Let's now review our exam poll.

Exam Poll

1) In the TNM cancer staging system, what does "MO" or "M1" stand for?

The correct answer is B, the presence or absence of metastasis.

2) What is a cancer treatment option?

It is all of the above as all of them could be cancer treatment options.

3) Which of the following is NOT in the OT Practice Guidelines for cancer rehabilitation for adults?

The answer to this one is B. We're not responsible for setting up all chemotherapy treatments.

4) What can cause cancer-related fatigue?

The answer to this one is D.

5) When reviewing rehabilitation paradigms, palliative care aims for...

The correct answer is balance between comfort and function.

References

Abdur Rahman, M., Rashid, M. M., Le Kernec, J., Philippe, B., Barnes, S. J., Fioranelli, F., ... & Imran, M. (2019). A secure occupational therapy framework for monitoring cancer patients’ quality of life. Sensors, 19(23), 5258.

Deshields, T. L., Wells‐Di Gregorio, S., Flowers, S. R., Irwin, K. E., Nipp, R., Padgett, L., & Zebrack, B. (2021). Addressing distress management challenges: Recommendations from the consensus panel of the American Psychosocial Oncology Society and the Association of Oncology Social Work. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(5), 407-436.

Esplen, M. J., Foster, B., Pearson, S., Wong, J., Mackinnon, C., Shamsudeen, I., & Cecchin, K. (2020). A survey of oncology healthcare professionals’ knowledge and attitudes toward the use of music as a therapeutic tool in healthcare. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28, 381-388.•

Hirschey, R., Nance, J., Wangen, M., Bryant, A. L., Wheeler, S. B., Herrera, J., & Leeman, J. (2021). Using cognitive interviewing to design interventions for implementation in oncology settings. Nursing research, 70(3), 206.

Hwang, N. K., Jung, Y. J., & Park, J. S. (2020, September). Information and communications technology-based telehealth approach for occupational therapy interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. In Healthcare, 8(4), 355). MDPI.

Lai, L. L., Player, H., Hite, S., Satyananda, V., Stacey, J., Sun, V., ... & Hayter, J. (2021). Feasibility of remote occupational therapy services via telemedicine in a breast cancer recovery program. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(2).

Nightingale, G., Battisti, N. M. L., Loh, K. P., Puts, M., Kenis, C., Goldberg, A., ... & Pergolotti, M. (2021). Perspectives on functional status in older adults with cancer: an interprofessional report from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) nursing and allied health interest group and young SIOG. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 12(4), 658-665.

Pergolotti, M., Bailliard, A., McCarthy, L., Farley, E., Covington, K. R., & Doll, K. M. (2020). Women’s experiences after ovarian cancer surgery: distress, uncertainty, and the need for occupational therapy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(3), 7403205140p1-7403205140p9.

Pergolotti, M., Deal, A. M., Williams, G. R., Bryant, A. L., McCarthy, L., Nyrop, K. A., ... & Muss, H. B. (2019). Older adults with cancer: a randomized controlled trial of occupational and physical therapy. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(5), 953-960.

Presley, C. J., Krok-Schoen, J. L., Wall, S. A., Noonan, A. M., Jones, D. C., Folefac, E., ... & Rosko, A. E. (2020). Implementing a multidisciplinary approach for older adults with cancer: geriatric oncology in practice. Bmc Geriatrics, 20, 1-9.

Rijpkema, C., Duijts, S. F., & Stuiver, M. M. (2020). Reasons for and outcome of occupational therapy consultation and treatment in the context of multidisciplinary cancer rehabilitation; a historical cohort study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(3), 260-268.

Sattar, S., Kenis, C., Haase, K., Burhenn, P., Stolz-Baskett, P., Milisen, K., ... & Puts, M. T. (2020). Falls in older patients with cancer: Nursing and Allied Health Group of International Society of Geriatric Oncology review paper. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 11(1), 1-7.

Stout, N. L., Santa Mina, D., Lyons, K. D., Robb, K., & Silver, J. K. (2021). A systematic review of rehabilitation and exercise recommendations in oncology guidelines. CA: A cancer journal for clinicians, 71(2), 149-175.

Udovicich, A., Foley, K. R., Bull, D., & Salehi, N. (2020). Occupational therapy group interventions in oncology: A scoping review. The American Journal of OccupationalTherapy, 74(4), 7404205010p1-7404205010p13.

Williams, G. R., Weaver, K. E., Lesser, G. J., Dressler, E., Winkfield, K. M., Neuman, H. B., ... & Klepin, H. D. (2020). Capacity to provide geriatric specialty care for older adults in community oncology practices. The oncologist, 25(12), 1032-1038.

Citation

Davin, K. (2024). Navigating the journey: OT’s role in oncology and navigating end-of-life care. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5719. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com