Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Neuro Rehab Strategies in the Home Setting, presented by Sara Frye, MS, OTR/L, ATP.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify 3 safety considerations for neurologic rehabilitation in the home setting.

- After this course, participants will be able to compare and contrast 3 evidence-based strategies for home-based neurologic rehabilitation.

- After this course, participants will be able to examine 3 components of an effective neurologic home exercise program.

Introduction

I'd like to begin by sharing my professional journey. I started my career in an inpatient rehabilitation unit for individuals with spinal cord injuries, where I worked for approximately 12 years. Following that, I transitioned to an inpatient rehabilitation program focused on brain injuries, both traumatic and non-traumatic. Later, I joined a comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation unit with a specific focus on stroke patients. After gaining considerable experience in the inpatient rehabilitation setting, I made the transition to home health with a particular passion for neurologic rehab.

One aspect I truly appreciate about neurologic rehab is the demand for creativity and critical thinking. Building strong relationships with my clients and witnessing their progress over time brings me immense joy.

However, I faced some differences in the home health setting. Unlike the clinic environment, I didn't have immediate access to my team to collaborate on problem-solving, and I couldn't call for extra assistance whenever needed. This change significantly impacted my practice, as I no longer had access to the same array of rehabilitation technology or resources I had at my disposal in the clinic. Consequently, I had to adapt my approach and learn to practice in a slightly different manner. Today, I'll be sharing some of the valuable insights and lessons I've gained from this experience.

Challenges of Neuro Rehab in Home Health

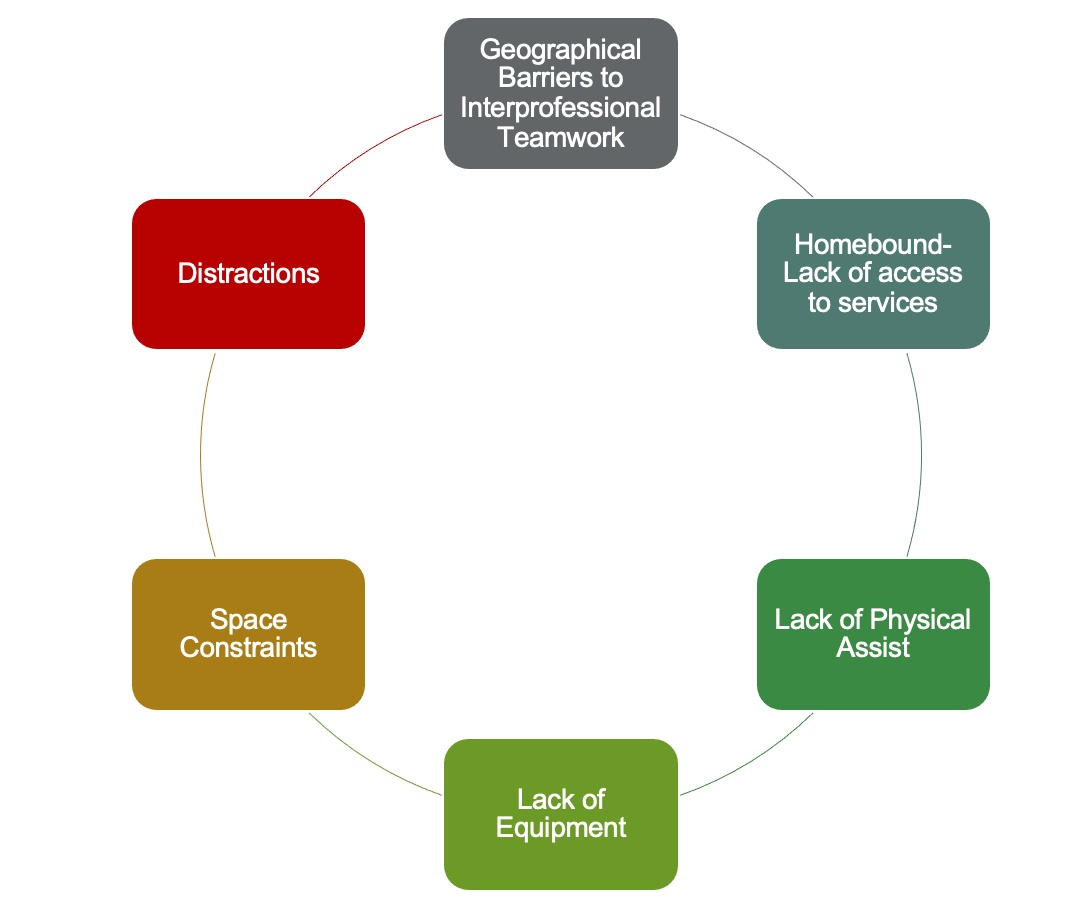

There are several key challenges to providing neurologic rehabilitation in home health, as noted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Six key challenges of neuro rehab in the home.

Geographical Barriers to Interprofessional Teamwork

The first challenge is the presence of geographic barriers that hinder interprofessional teamwork. Depending on the location of your work, you may be in close proximity to other members of your home health team, or you might need to cover a wide area where coordination and co-treatment become challenging when required. Additionally, there may be difficulties in accessing physicians, providers, or other individuals providing input into the patient's care. To address this, an effective communication strategy is vital. Utilizing secure messaging systems, making phone calls, and using case communication within the electronic medical record can help foster better communication and collaboration among team members.

Homebound- Lack of Access to Services

The second challenge we will discuss is the difficulty faced by homebound individuals in accessing specialty services. Leaving their homes can be a taxing effort for them, which makes it challenging to access services like tone management or specialty providers such as urologists, along with other community services they may require. To address this issue, we often need to adopt a more creative approach.

Lack of Physical Assistance

The third challenge involves the lack of physical assistance for clients with more significant physical impairments. Having an extra set of hands, or even multiple sets, can be crucial in such cases. However, due to distance or other factors, it may not always be possible to have people available in the home to provide the necessary assistance. While some clients may be fortunate to have a supportive and hands-on family, certain interventions demand skilled physical assistance that goes beyond what family members can provide.

Lack of Equipment

Another significant challenge is the lack of equipment in the home health setting. In contrast to the resources available in inpatient rehabilitation, where various equipment, such as large tables for gravity-eliminated exercises with an arm skate or state-of-the-art robotic devices, were readily accessible, home health practitioners often have to adapt to doing more with limited resources. As occupational therapists, we possess the valuable ability to think creatively and find innovative solutions.

Space Constraints

The next challenge is dealing with space constraints in the home health setting. Some clients may have limited space in their homes, which can impact the types of interventions we can implement. Additionally, factors like physical limitations, adverse weather conditions, or accessibility issues might restrict our ability to work outside, further confining our interventions to indoor settings. As a result, we must be resourceful and develop dynamic interventions that can effectively take place within a small space.

Distractions

Lastly, distractions pose another challenge during home health therapy sessions. Unlike in an inpatient rehab setting, where the therapy time is more isolated and dedicated, home health therapists need to integrate themselves into their clients' home routines. This means being mindful of factors such as kids coming home from school, mail being delivered, or visitors arriving, which can all affect the client's participation in the therapy session.

However, as I'll discuss later, these distractions can also present opportunities for incorporating dual-task activities into therapy. By carefully considering the client's daily activities and incorporating them into therapy, we can make the most of these distractions and use them as part of the treatment process.

Health Care is Moving Home

- Recent trends for shorter lengths of inpatient stays

- Home health increased 7.21% from 2020 to 2021 with continued growth projected through 2030 (Grandview Research, 2022).

When considering neuro rehab in the home health setting, it's important to acknowledge that this practice is becoming increasingly prevalent. Recent trends indicate shorter inpatient rehabilitation stays for individuals with new injuries, leading to a rise in home healthcare utilization. In fact, home health services experienced a notable 7.21% increase from 2020 to 2021, and this growth is projected to continue at a similar rate until the year 2030.

To put it into perspective, there were approximately 600 million home health visits in the United States last year alone. This significant number underscores the increasing demand for home rehabilitation services, and it indicates that the need for such care will continue to expand in the coming years.

Common Neuro Diagnoses Seen in Home Care

- Stroke

- Parkinson’s Disease

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Brain Injury (consider also Brain Tumor)

In the home care setting, healthcare professionals commonly encounter patients with various neurologic diagnoses, including stroke, Parkinson's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, and brain injuries. Additionally, clients with brain tumors are also prevalent, presenting with a range of neurologic impairments.

The treatment interventions that will be discussed today are generally applicable to all these patient populations. However, it's worth noting that for patients with ALS, a more compensatory approach is often adopted instead of focusing on remediating strategies that will be covered in this discussion. ALS is a progressive and debilitating disease, so the emphasis is typically on helping patients adapt to their changing abilities and enhancing their overall quality of life.

What is Neuro Rehab?

- Skilled rehabilitation focused on improving function, decreasing symptoms, and improving the quality of life for people with neurologic conditions.

- Neuroplasticity- “the ability of the nervous system to change its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, functions, or connections.” (Mateos-Aparicio & Rodríguez-Moreno, 2019)

Neurologic rehabilitation refers to a specialized form of rehabilitation that aims to enhance function, alleviate symptoms, and improve the quality of life for individuals with neurologic conditions. Neuroplasticity is a fundamental concept in this field, denoting the nervous system's ability to modify its activity in response to internal and external stimuli, leading to the reorganization of its structure, functions, and connections.

The concept of neuroplasticity encompasses two essential aspects: the brain's capacity to create new connections and its ability to adapt and redirect information through existing connections. In the context of skilled neurologic rehabilitation, we leverage this neuroplasticity by providing individuals with tailored intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli. By doing so, we facilitate the brain's reorganization process, thereby aiding in the recovery and improvement of functional abilities.

Ultimately, the primary objective of neurologic rehabilitation is to harness the potential of neuroplasticity to optimize an individual's recovery and overall well-being after a neurologic injury or condition.

Motor Learning Principles: Systems Model

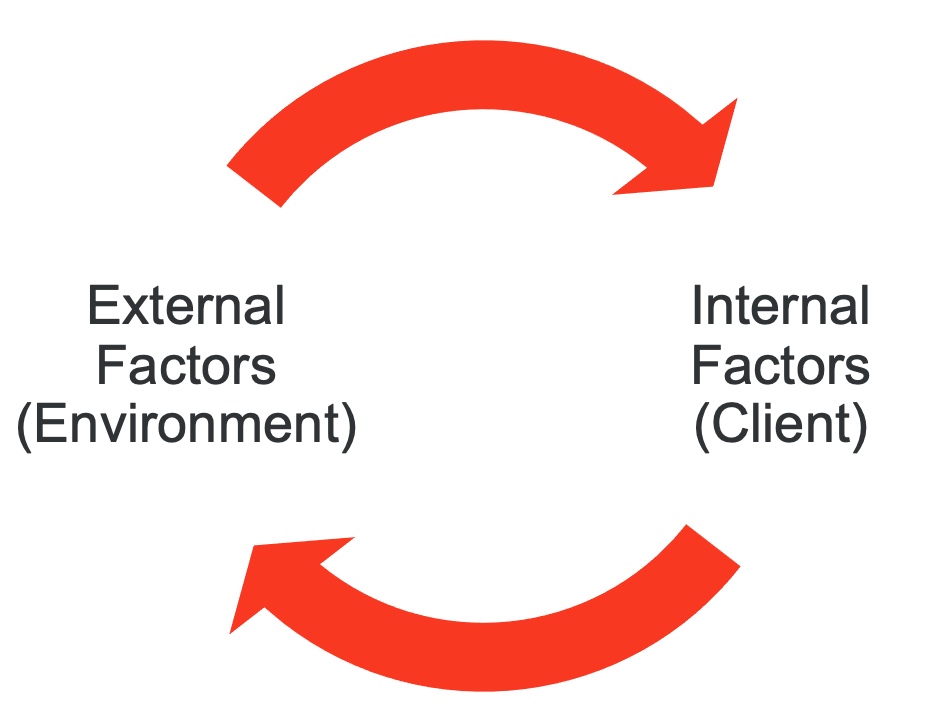

When considering neurologic rehabilitation, it is helpful to understand motor learning principles about how people acquire new motor skills. An overview of the systems model is seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Graphic of the systems model.

I will start by discussing some motor learning principles. When considering motor learning, it is essential to adopt a systems model. As an Occupational Therapist (OT), I always take into account the internal factors, which refer to the client, and the external factors, which pertain to the environment. From my perspective, I often think about the PEO model, which emphasizes the dynamic interplay between the client and their environment. This interplay of internal and external factors is crucial in fostering participation in occupational performance.

However, in the context of motor learning, our primary focus is on how we can stimulate the brain to acquire new movement patterns and learn novel ways to perform tasks, thereby promoting neuroplasticity. By exploring strategies that encourage neuroplasticity, we can facilitate the process of acquiring and mastering new motor skills.

Motor Learning Principles

- Start with smaller more controlled movements and amplify (degrees of freedom)

- Working on a task in parts and moving to the whole task

- Providing opportunities for mass practice

- Moving from more controlled environments to less controlled environments

When discussing motor learning principles, we consider how individuals learn new motor skills. One crucial principle is beginning with smaller and more controlled movements and gradually increasing their complexity. This concept is often referred to as "degrees of freedom." For example, when working on a task, we might first focus on specific hand movements, then incorporate wrist movements, and eventually progress to larger movements that traverse through space. A relatable example of this is learning to ice skate, where initially, movements are slow and restricted, but with practice and motor learning, longer strides and smoother motions become achievable.

Another important principle is breaking down a task into smaller parts and mastering each part individually before combining them into the whole task. This approach is familiar as forward chaining or backward chaining in occupational therapy education. By learning and perfecting each component, clients can gradually develop the ability to execute the entire task effectively.

Providing opportunities for mass practice is another key motor learning principle. This involves allowing clients to practice a movement multiple times rather than just once, which reinforces learning and improves skill acquisition. Starting with controlled environments and progressively transitioning to less controlled ones is also vital in motor learning. It could mean beginning a task in a distraction-free setting and gradually introducing more complex or challenging elements. Similarly, starting on a smooth, flat surface and then progressing to an uneven surface helps individuals gain better control over their bodies as they develop their skills.

Motor Learning Stages

1. Acquisition - learning the skill

2. Retention - retaining the skill over time

3. Transfer - the ability to transfer a skill to new environments

Motor learning is a process that unfolds in three distinct stages. The first stage is the acquisition phase, during which individuals learn the necessary skills. In the second stage, known as retention, they diligently practice and refine these skills to enhance proficiency. Finally, in the third stage, known as transfer, learners are capable of applying the acquired skills to new and challenging environments, demonstrating adaptability and versatility.

Skill Acquisition

- Initial Stage

- Learn movement

- Identify needed environmental supports

- Later Stages

- Move from explicit to implicit control

When we're thinking about that early stage of skill acquisition, that is when the client is really focused on learning the movement. And our job can also be to identify needed environmental supports. How can we change the environment to allow that client to perform better? Is there a certain amount of light they need to be able to have the visual discrimination for the task? Is there a certain type of sensory input we can provide that will allow them to perform better?

In the later stages of motor learning, the focus shifts from explicit to implicit control. This means that the goal is for clients to internalize motor patterns and execute them independently, without relying on external cues like environmental prompts, verbal feedback from the therapist, or tactile facilitation.

- Consistency

- Flexibility

- Efficiency

The ultimate measure of motor learning success involves three key elements. The first element is consistency. Clients should be able to perform the skill consistently every time they attempt it, or at least with a high level of regularity.

The second element is flexibility. This refers to the ability to perform motor skills in different contexts and under various conditions. Clients should be capable of executing the task in different positions (sitting and standing) and in different environments (indoors and outdoors), showcasing adaptability.

The third element is efficiency. The client's performance of the task should be efficient, without unnecessary errors or large compensatory movements that hinder the effectiveness of the activity. Efficiency is crucial for enhancing independence and functionality.

One of the challenges faced in neuro rehab, especially when working with clients at home, is fall prevention. To promote neuroplasticity, therapists often need to push the envelope and engage clients in tasks that challenge their motor abilities, even if it involves some degree of risk. The key is to strike a balance between pushing the boundaries for improvement while ensuring safety and preventing accidents.

Fall Prevention

I would like to discuss some strategies I've developed to promote fall prevention in the home.

Treatment Strategies

- Demonstrate and/or rehearse tasks with a client

- Review fall prevention measures during the demonstration

- Use a gait belt

- Perform balance challenges in front of a surface

- Maintaining UE support in standing

- Consider seated tasks

- Ensure the client has appropriate footwear

As a treatment strategy for fall prevention, I prioritize demonstrating and rehearsing tasks with the client. Following the principles of motor learning, I start with controlled environments, gradually progressing to less controlled ones. I provide initial support, practicing the task before moving on to more challenging balance exercises or dual-task activities. During the demonstration, I also educate the client on fall prevention techniques and show them how to avoid falls.

In some cases, I utilize a gait belt, which can be a controversial method but proves useful in the home health setting. It allows me to give clients a bit more physical space to challenge their balance while providing the necessary assistance to prevent falls.

For tasks that involve dynamic movements or balance challenges, I conduct them in front of a supportive surface. For example, if a client is doing sit-to-stands at the edge of a bed or performing a balancing task at the counter, I position myself in front of them or behind them to offer support from both sides.

To intensify exercises, I may have clients maintain one upper extremity support in a standing position, such as bracing against a wall or holding onto a counter. Additionally, I incorporate seated exercises for higher-intensity tasks, considering what clients can safely do on their own when I'm not present.

Lastly, I prioritize ensuring that clients have appropriate footwear, encouraging the use of supportive, non-skid sneakers to minimize the risk of falls.

Environmental Strategies for Fall Prevention

- Assess environmental safety at every visit

- Remove hazards

- Smooth surfaces

- Adequate lighting

- Limit distractions

Environmental strategies play a crucial role in fall prevention, and I ensure to assess environmental safety during each visit with my clients. When identifying potential hazards, I make a point to involve the client in my clinical reasoning process. Instead of merely instructing them to remove a throw rug, I explain that I've noticed they have difficulty lifting their foot high enough, and the throw rug might pose a tripping risk. This approach engages the client in problem-solving and helps them understand the rationale behind safety recommendations.

To enhance the home's safety, I proactively remove any potential hazards that could lead to falls. Additionally, when conducting more dynamic treatments, I select areas within the home that have smooth surfaces, adequate lighting, and no loose flooring or trip hazards.

During the early phases of motor learning, I aim to minimize distractions or strategically use them as part of the therapy. This helps the client focus on the task at hand and promotes a more effective learning experience.

High Intensity Training: Relationship to ADLs

The next topic of discussion is high-intensity training and its connection to activities of daily living. High-intensity training is a buzzword in neuro rehab, and it's an aspect I enjoy integrating into my therapy sessions. However, I've heard fellow therapists argue that we must prioritize ADL. Now, the question is: How can we strike the perfect balance? How can we blend high-intensity training with promoting independence in ADL performance through effective motor learning strategies?

High Intensity Training (HIT)

- Periods of high intensity exercise

- Benefits of both high intensity and moderate intensity exercise

- Can be interspersed

- Higher intensity periods can be as short as 20 seconds

High-intensity training involves periods of rigorous exercise or activity, offering benefits alongside moderate intensity exercises. The incorporation of both high and moderate intensity intervals can be interspersed throughout therapy sessions. It's not necessary to maintain a constant high or moderate intensity phase during therapy. Even short bursts of high intensity, as brief as 20 seconds, can yield positive results for motor learning and overall improvement.

What is High Intensity?

- Moderate Intensity 60-75% Max Heart Rate

- High Intensity 75-80% Max Heart Rate

- Rate of perceived exertion

- Borg (6-20 scale)

- Modified Borg (1-10 scale)

(ANPT, 2018)

High intensity, as defined in the context of your therapy, can be quantified using heart rate percentages or the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) scale. For heart rate percentages, moderate intensity falls within 60 to 75% of the maximum heart rate, while high intensity is between 75 to 80% of the maximum heart rate. This calculation depends on factors like age and fitness level.

Alternatively, the RPE scale can be used, with options like the Borg scale (six to 20) or the modified Borg scale (one to 10). On the modified Borg scale, moderate activity typically falls between 3 to 5, and 6 and above signifies high intensity. On the six to 20 scale, moderate intensity usually corresponds to 12 to 14, while 15 and above indicates high intensity. Verbal descriptors, such as "somewhat hard" or "somewhat challenging," can help gauge the patient's perceived exertion during the activity.

It's essential to gather feedback from the client to determine their comfort and capability during the training. The level of intensity will vary individually, based on their skills, endurance, and progress over time. Thus, patient-specific outcome measures are crucial to track and tailor the therapy effectively for each individual's needs and progress.

HIT in the Home?

- Clarify vitals parameters with a provider

- Carefully observe the patient for signs of distress

- Monitor activity tolerance with vitals and RPE

- Can consider smart technologies as an adjunct

- Allow for a cool-down period and monitor the patient’s return to baseline

Implementing high-intensity training in a home setting can be challenging, but it's essential to prioritize safety and monitor the client closely. When working with clients who have cardiovascular issues, always clarify vital parameter guidelines with a healthcare provider. This ensures that you're adhering to best practices and taking their specific health needs into account.

For clients on medications that affect heart rate sensitivity, relying on the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) scale becomes crucial. Careful observation during the session is vital, watching for any signs of distress or discomfort. Monitoring activity tolerance through vital signs and the RPE scale before, during, and after the session helps track their response to the exercises.

Regularly checking heart rate, oxygen levels, and possibly blood pressure during the session provides valuable real-time data. Smartwatches that can monitor heart rate in real-time are convenient tools to have, especially for high-intensity interventions. After the session, allowing a cool-down period is beneficial, as it lets the client return to their baseline gradually.

It's essential to educate clients on what to expect after the exercise session. Effects of exercise may persist, so they should be aware of any lingering changes and know what signs to look out for to monitor their own well-being. Open communication and individualized monitoring are key to ensuring the client's safety and maximizing the benefits of high-intensity training at home.

Balancing HIT and Occupation-Based Practice

- Consider HIT as a preparatory method

- Can be a primer for motor learning during ADL tasks

We achieve a balance between high intensity and occupation-based practice by considering high intensity as a preparatory method and a primer for motor learning during ADL tasks. The seated march, as shown in Figure 3, serves as an effective warm-up to introduce some intensity before starting the session.

Figure 3. Client marching while seated.

By incorporating high-intensity exercises at the beginning, we can prepare the client's neuromuscular system and enhance their motor learning during subsequent occupation-based activities.

Can High Intensity Be Built Into ADL Routines?

- Bouts of sit to stand when getting up from a chair

- Bouts of fast walking on the way to the mailbox

- Completing activities and potentially rest breaks in standing

- Location transitions in the home throughout the session

Incorporating high intensity into ADL routines can be highly beneficial for maximizing therapy outcomes. Some effective ways to achieve this are by including sit-to-stand bouts when getting up from a chair or doing activities like walking to the bathroom. During walks to perform specific ADLs, encourage maintaining a brisk pace for short intervals to introduce high-intensity segments into the routine. Instead of remaining seated during therapy, promote standing throughout the session to improve postural control, balance, and overall engagement. Additionally, consider doing location transitions in the home during the session, utilizing different areas to increase standing and mobility and drive up the intensity of the therapy.

Promoting HIT Through Dual Task Training

- Dual task training

- Motor-Motor

- Motor-Cognitive

- Cognitive-Cognitive

- And more!!!

- Can be used to drive HR up and stimulate neuroplasticity

Dual-task training is an excellent method for promoting intensity in therapy. By having the client focus on two tasks simultaneously, it challenges their cognitive and motor abilities. This dual-task approach can involve combining two motor activities, such as engaging in upper-body and lower-body exercises simultaneously or combining a motor activity with a cognitive task. An example is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Example of dual task training.

For instance, you could have the client perform a walking exercise while also answering simple math questions or reciting a list of items. Another option is to layer a scanning activity onto any of these combinations, where the client must visually search for specific items while performing other tasks.

Dual-task training not only increases the client's heart rate and physical intensity but also stimulates neuroplasticity. The brain is exposed to a higher volume of internal and external stimuli, forcing it to adapt and process the information more efficiently. This stimulation enhances the brain's ability to form new neural connections, leading to improved cognitive and motor performance.

Sample Dual Task Activities in the Home

- Motor

- Box stepping or box walking

- Throwing a ball

- Passing an object hand to hand

- Carrying a glass of water

- Unloading a dishwasher

- Making coffee

- Cognitive

- Serial 7

- Categories

- Scanning

- Sorting mail

- Conversation

Dual-task activities in the home can be a great way to promote intensity and challenge both physical and cognitive abilities. For instance, you can have the client engage in box stepping or box walking, which involves stepping back and forth in a box pattern outlined by painter's tape on the floor.

To add a cognitive aspect, you can have them perform tasks like scanning, sorting mail, holding a conversation, doing serial sevens (counting backward by seven from a hundred), listing categories, or passing an object hand-to-hand while doing the stepping activity. Other examples include walking while carrying an object and stepping over something, unloading the dishwasher while engaging in a category activity, or performing seated shoulder exercises with resistance bands while reciting days of the week backward.

Potential Treatment Items

Figure 5 shows some potential treatment items.

Figure 5. Examples of treatment ideas for dual-task training.

One effective way to incorporate dual-task training is through the use of a deck of cards. For instance, we can have clients stand at their kitchen counter and take side steps while reading cards held up by the therapist. Every time they encounter a black card, they step to the right, and with each red card, they step to the left. Alternatively, we can use only number cards, instructing the client to add or subtract depending on the card's color. To further challenge the client, we may introduce an additional layer, such as rolling a ball back and forth while performing the card-based activity.

Another useful tool is post-it notes, which can provide excellent targets for promoting scanning abilities. Strategically placing post-its around the home, each labeled with different kitchen items, can create a scavenger hunt-like activity. Clients retrieve the Post-it from the wall, place it on the counter, and then go to the kitchen to retrieve the corresponding item. This exercise effectively incorporates scanning, kitchen mobility, and sequencing of multi-step tasks.

Incorporating props like a ball and sponge can also enhance dual-task exercises. For example, using the sponge as a target during tabletop tasks challenges clients to scan to peripheral vision fields. Additionally, a big ball and a set of small cones can be utilized for engaging gross motor and fine motor scanning activities. Clients can stand at the edge of the bed and throw the rings to the cones, stating the name of a state or a similar item with each throw.

In conclusion, dual-task training is a valuable strategy for promoting neurorehabilitation in the home setting. By creatively integrating motor and cognitive activities, therapists can challenge clients' neural pathways, leading to enhanced neuroplasticity and improved functional abilities.

Seated Step Test

- Measure blood pressure and heart rate pre-post

- Alternate: rate of perceived exertion

- Metronome of 60 beats per minute

- Stage 1: 6”

- Stage 2: 12”

- Stage 3: 18”

- Stage 4 18” and arms

(VanSwearingen & Brach, 2001)

The seated step task, Figure 6, is a valuable method I often employ during dual-task activities, particularly for clients who require a lower intensity option or when safety is a concern.

Figure 6. Example of a client doing the seated step task.

Although there is a standardized way to perform this task, I have also observed significant benefits from using a non-standardized approach with my clients. The traditional method involves using an aerobic step, but in the photo provided, you can see a purple folding stool that I carry for placing my clinical bag.

To conduct the seated step task, I have the client sit in the same chair and tap their foot, synchronizing their movements with a metronome app on my phone set to 60 beats per minute. The objective is to maintain this tapping rhythm for a duration of two minutes. Initially, many clients struggle to sustain the activity for even a minute. However, by regularly integrating this exercise into therapy sessions, I have observed notable improvements in their endurance over time.

Using the seated step task allows me to document the progress of my clients' endurance, serving as a valuable measure of their functional improvements.

Evidence

- There is evidence to support moderate to high intensity exercise for sub-acute stroke and spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease (ANPT, 2018).

- There is strong evidence that physical activity(exercise) interventions improve motor and nonmotor function for adults with Parkinson’s Disease (Foster et al., 2021)

- Strategies to support: peer mentoring, social support and interaction, goal setting, action and coping planning, and activity tracking

There is substantial evidence supporting the effectiveness of moderate to high intensity exercise for individuals with subacute stroke, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson's disease. These exercise interventions have shown significant benefits in improving both motor and non-motor functions in these populations. Importantly, these benefits are not only limited to individuals with new injuries; even those with existing conditions can continue to reap the advantages of engaging in moderate and high intensity activities.

For adults with Parkinson's disease, in particular, physical activity has been demonstrated to be highly beneficial. Various strategies can be employed to support their participation in regular exercise. Peer mentoring and social support play pivotal roles in motivating and encouraging individuals to stay engaged in physical activities. Having a family member or friend join in on walks or exercises can provide additional motivation and support.

Moreover, implementing goal-setting, action planning, coping strategies, and activity tracking can be highly motivating. Tools like Fitbit or similar wearable devices can be utilized to monitor activity levels, giving individuals real-time feedback and a sense of accomplishment as they achieve their goals.

By integrating these evidence-based strategies and interventions into rehabilitation programs, therapists can help clients maintain their motivation and adherence to physical activity. With consistent support and the use of effective strategies, individuals with neurological conditions can experience improved motor and non-motor functions, leading to an enhanced quality of life.

Upper Extremity Strategies

Now, let's discuss upper extremity strategies for home-based rehabilitation. When addressing upper extremity management, we need to consider various aspects such as positioning, range of motion, strength, fine motor coordination, gross motor coordination, and endurance. These factors are crucial in promoting functional independence and improving upper limb function. To achieve these goals effectively, we will apply motor learning principles, which play a key role in optimizing the learning and retention of new motor skills.

Neuro Re-education Strategies

- Sensory strategies

- Tactile (tapping, hand over hand)

- Proprioceptive (weight-bearing, deep pressure)

- Auditory (snapping, bells, verbal cues)

- Visual (ribbon on wrist, line of tape in environment)

- Crossing Midline

This is an area where neurologic reeducation strategies play a vital role. Utilizing sensory strategies is essential in promoting motor learning and providing extrinsic feedback to the client, which can be gradually reduced as they master their motor skills. Tactile strategies, such as hand-over-hand guidance and tapping over specific muscles to encourage activation, can be effective in enhancing motor control.

Proprioceptive strategies involve having the client weight-bear onto an affected limb or providing deep pressure, which helps improve body awareness and coordination. Auditory strategies, such as verbal cues or snapping to direct their attention, can be useful for clients with an affected side.

Visual strategies offer valuable support, like using a line of tape in the environment as an anchor or placing a ribbon on their wrist to encourage visual attention to the affected side. Additionally, visual cues like Post-it notes can be employed to guide their movements.

An essential aspect of neurologic reeducation is encouraging clients to engage both sides of their body together and work on crossing the midline. For instance, if a target is on the right side, they reach for it using their left hand, and vice versa.

Spasticity Management

- Barriers to provider access limit spasticity management in the home.

- While working to develop a plan for medical management, positioning strategies are key to preventing contractures.

Managing spasticity in the home setting can indeed present unique challenges due to limited access to providers and specialized resources. In such cases, telehealth providers or collaboration with the client's primary care physician (PCP) become valuable allies in developing an effective spasticity management plan.

While addressing spasticity, the primary focus is on preventing contractures through strategic positioning strategies. As a therapist, I can administer range of motion exercises during therapy sessions and educate caregivers on how to implement these exercises regularly. However, the key lies in adopting proper positioning techniques to elongate muscles and prevent contractures while concurrently working on other tone management principles.

Ensuring that the client's muscles are positioned in an elongated state helps maintain flexibility and mobility, reducing the risk of contractures. Collaborating with telehealth providers or the PCP allows for comprehensive care and ensures that the spasticity management plan is tailored to the client's specific needs.

Ultimately, combining range of motion exercises, positioning strategies, and tone management principles contributes to an effective and holistic approach to managing spasticity in the home environment.

Orthotic Access

- In-home orthotist consult

- Self-purchase options

- Clinic-based appointments

- Referral to outpatient

Orthotic access in the home setting can be a significant challenge, but there are various avenues to explore for obtaining the necessary orthotics. As therapists, we strive to provide the best care possible, and obtaining appropriate orthotics is an essential part of the treatment process.

In some cases, an orthotist can come to the client's home to provide custom-made orthotics, ensuring a proper fit and functionality. Additionally, clients may have the option to purchase splints online or from a pharmacy, which can be convenient and accessible.

For clients with conditions like ALS or MS, interdisciplinary specialty clinics may offer orthotic services, providing them with the appropriate support they need. In situations where home-based options are limited, the goal is to refer these clients to outpatient clinics, where they can receive comprehensive orthotic care.

It is important to be thorough in our assessment and communication with clients. Often, clients may already possess the recommended splint in a drawer at home, unbeknownst to them. Therefore, our first step should always be to ask the client if they have any existing orthotics that align with our recommendations.

Navigating the challenges of orthotic access requires collaboration with various stakeholders, including orthotists, specialty clinics, and outpatient facilities.

Modified Constraint-induced Movement Therapy (mCIMT)

- Restraining the unaffected limb to force the use of the affected limb

- Client performs structured functional activities while wearing restraint

- Guidelines for use:

- Active movement in the affected arm

- Cognitive skills to follow protocol

- Ability to ambulate using the restraint must be evaluated.

- CIMT protocol 6-7 hours/day for 15 days

- mCIMT lower doses, some protocols recommend 2 hours daily, but improvements seen with 1 hour, 3X per week

- Improvements may include motor function, range of motion, and reduced spasticity

(Rocha et al., 2021)

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) offers a wide range of benefits for individuals with various neurological conditions. By encouraging the use of the affected limb and providing intensive training, CIMT can significantly improve motor function, range of motion, and spasticity in clients.

For stroke survivors, CIMT has shown remarkable results in enhancing motor function, helping them regain functional abilities in their affected limbs. Additionally, CIMT can improve balance in stroke patients, contributing to increased stability during daily activities.

Although CIMT is often associated with the stroke population, there is emerging evidence supporting its effectiveness for individuals with Parkinson's disease as well. For people with Parkinson's disease, CIMT has demonstrated positive outcomes in promoting motor function and reducing the impact of motor symptoms on their daily lives.

By tailoring the therapy to the unique needs of each individual, CIMT can address specific motor challenges and contribute to substantial improvements in motor function, range of motion, and spasticity management.

- mCIMT Evidence

- CIMT can improve upper limb motor function in people with stroke compared to standard therapy (Corbetta et al., 2015).

- CIMT can also improve balance in adults with stroke (Tedla et al., 2022).

- Although CIMT is often associated with the stroke population, there is evidence to support its use for clients with Parkinson’s Disease as well (Wellsby et al., 2019).

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) offers significant benefits in improving motor function, range of motion, and spasticity. For individuals with stroke, CIMT has proven to be effective in enhancing motor function and can also contribute to improved balance. Moreover, CIMT's positive impact is not limited to the stroke population; evidence supports its use for individuals with Parkinson's disease as well.

Mirror Therapy

- A mirror box is placed in front of the client. The affected hand is placed in the box, and the unaffected hand is next to the mirror. Completed movement by the unaffected hand gives the illusion the affected limb is moving (in the reflection). The patient may also try to move the unaffected hand (bilateral mirror therapy).

- Sample Tasks:

- Active range of motion exercises- wrist flexion/extension, finger opposition

- Functional tasks: Wiping table with a rag

- Fine Motor: Flipping Cards

(Geller et al., 2021)

Mirror therapy is a common and effective intervention for improving upper extremity function in individuals with neurological conditions. The concept involves using a mirror box placed in front of the client, with the unaffected hand visible in the mirror while the affected hand is hidden behind it. When the client moves the unaffected hand, it creates the illusion that the affected limb is also moving in the reflection.

During mirror therapy, clients can engage in various activities, such as active range of motion exercises and functional tasks like wiping a table with a rag or flipping cards. This approach can help promote motor relearning and facilitate the brain's neural pathways, contributing to improved motor function in the affected limb.

While creating a mirror box at home can be challenging, there are alternative options for conducting mirror therapy. For example, a simple and cost-effective method involves using a full-length mirror, which many people already have at home. Placing the mirror between the client's legs while seated allows them to see the reflection of their unaffected hand and engage in the therapy exercises effectively.

- Mirror Therapy: Evidence

- Trial of home-based mirror therapy (Geller et al., 2021)

- 1-hour instruction session with OT

- Provided mirror box, activity supplies, instructional handout, and log to record sessions

- 30 mins/day, 5 days/week

- 6 week protocol

- 2x45 minute sessions and weekly 30-minute check-in

- Results, unilateral mirror therapy more effective than bilateral mirror therapy or control

Research supports the effectiveness of mirror therapy when applied with a consistent schedule. Engaging in mirror therapy for 30 minutes daily, five days a week has been shown to lead to improvements in function and motor recovery for individuals with neurological conditions.

Moreover, studies have indicated that unilateral mirror therapy, where the focus is primarily on moving the unaffected arm while the affected arm remains stationary, can be more effective than bilateral mirror therapy. By directing attention to the unaffected limb's movements, the brain's neural pathways related to motor function are more effectively stimulated, resulting in enhanced motor relearning and function.

As therapists, it is crucial to consider the evidence and tailor the mirror therapy approach based on the individual's specific needs and response to treatment.

Action Observation

- Client observes an action and then executes it in context.

- Action should be discrete and can be observed from various angles.

- Observation can include videos or demonstrations.

- Sample videos can be found on YouTube, but diverse skin tones may be limited.

- May be combined with motor imagery strategies

(Buccino, 2014)

Action observation is another valuable strategy for enhancing upper extremity function. During this intervention, the client observes a specific action being performed and then replicates it in context. The observed action should be clear and easily distinguishable, allowing the client to view it from various angles. While therapists can demonstrate the action, there are also numerous videos available on platforms like YouTube where clients can watch others performing tasks with their arms.

However, it is important to note that there may be limited availability of videos showcasing diverse skin tones, which should be taken into consideration when selecting appropriate resources for clients.

To further enhance the effectiveness of action observation, clients can employ motor imagery strategies. By mentally visualizing themselves performing the observed action while simultaneously engaging in the physical execution, they reinforce the motor learning process.

Action observation and motor imagery are complementary techniques that support motor relearning and neural plasticity. By integrating these strategies into therapy sessions, we can maximize the potential for functional improvement in upper extremity function.

While therapy sessions usually last for about one to two hours per visit, with two to three visits per week, the key to successful outcomes lies in regular and consistent practice.

Home Exercise Program

A home exercise program is essential to extend the benefits achieved during therapy sessions.

HEP Considerations

- Need for caregiver assist

- Setup or completion

- Adherence

- Goals

- Dose

There are some key considerations when developing a home exercise program. The first is the need for caregiver assistance. It is important to avoid creating a program that places a heavy burden on the caregiver, as they may already have significant responsibilities in assisting with the person's basic activities of daily living. Therefore, I prefer to focus on exercises that the client can perform independently or with minimal setup.

Another critical factor to consider is adherence. Will the client be motivated to consistently engage in the exercises? It's crucial to design a program that aligns with the client's interests and goals, ensuring they are more likely to commit to the routine.

Instead of overwhelming the client with numerous exercises, I aim to identify the most effective ones that are directly tied to the client's specific goals. By tailoring the program to their individual needs, we can increase the likelihood of adherence and successful outcomes.

Lastly, determining the appropriate dosage is essential. Finding the right balance between challenging the client and avoiding overwhelming them is crucial. Gradually increasing the intensity and complexity of the exercises over time can promote continuous progress and maximize the program's effectiveness.

HEP Modes

- Written

- Handwritten

- Printed

- Pictures

- Auditory

- Voice Memo

- Video

- YouTube

- Client Video

- Electronic

- Electronic programs

- Memory

There are numerous modes available for issuing a home exercise program, allowing us to tailor the delivery to the client's preferences and needs. The program could be in written form, printed instructions, or even pictures of the client performing the exercises to serve as visual cues. Alternatively, voice memos can be recorded and sent to the client's phone for easy access and auditory guidance.

Leveraging digital platforms can be advantageous as well. Clients can access exercise videos on platforms like YouTube, or therapists can take videos of the clients themselves performing the exercises, which can be emailed or shared electronically.

Interestingly, some clients may have excellent memory recall and can remember the exercises without any external aids, making this an effective home exercise program in itself.

By offering diverse modes of delivering the home exercise program, we enhance the likelihood of client adherence and engagement.

- Evidence: HEP Modes

- A randomized controlled trial found a significant increase in UE Fugl-Meyer Scores for those who received a multisensory electronic HEP compared to controls who received a paper-based program (Swanson et al., 2023).

- Electronic pressure sensing pucks and a tablet were used for the electronic HEP.

Research trials have explored the efficacy of various home exercise programs for individuals with stroke. One notable finding is that a multi-sensory home exercise program showed greater effectiveness compared to a traditional paper-based program.

In this innovative approach, clients utilized electronic pressure sensing pucks, a popular tool in inpatient neuro rehab, which was translated to the home setting. By incorporating dynamic activities and real-time feedback through these electronic tools, clients were able to track their progress and engagement in the exercises.

The multi-sensory nature of this program, which likely engaged different sensory modalities, appeared to hold promise in promoting better outcomes for stroke patients. The ability to tailor the home exercise program to individual needs and provide interactive elements through electronic devices might contribute to increased motivation, adherence, and overall effectiveness.

Examples

Now, I will share some samples of my work with clients that effectively combine intensity with simplicity. This is crucial since the most important aspect of any exercise is its practicality - it should be something the client can easily incorporate into their routine.

Circuit HEP Sample

- 10 shoulder rolls

- 10 chest press

- 10 shoulder touch

- 10 cross body reaches

- Complete the circuit 5 times

Here is a sample circuit home exercise program that I find effective for clients. It involves learning four key exercises, and they can gradually progress from one set to two sets and eventually up to five sets.

To keep things varied, I like to combine different exercises, alternating between high-intensity and low-intensity movements. We usually begin with a simple shoulder roll to warm up. Then, to ease the stress on the shoulder, we move on to a bicep shoulder touch. After that, we focus on cross-body reaches to further challenge and engage the muscles.

For an added element of fun and improvement, I incorporate some target practice using a ball and post-its, as in the example in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Sample of a circuit HEP exercise.

The client can touch the ball to each Post-it, either in numerical order (from one to ten) or alphabetically (from A to F), depending on their preference. This not only adds a scanning aspect to the workout but also helps improve coordination and accuracy.

To continuously challenge the client, I can rearrange the post-its every week, encouraging them to complete the circuit five times, reaching new heights in their performance.

Sample HEP for Hemiplegic UE

- Self Range of Motion 10 reps all planes

- Towel slides 5 minutes

- Seated ball exercises 5 minutes

- Incorporate affected UE as a gross assist whenever possible

The following is a sample home exercise program designed specifically for individuals with a hemiplegic arm (Figure 8). The focus of this program is to improve arm mobility, strength, and functionality.

Figure 8. Sample exercise for a hemiplegic upper extremity.

To begin, we recommend starting with self-range of motion exercises for the affected arm. Perform these exercises slowly and in a controlled manner, gradually increasing the range of motion as you feel comfortable. This will help to promote better arm mobility and build strength over time.

Next, consider incorporating towel slides or hand-over-hand towel slides into your routine. Place a towel on a flat surface and use your unaffected arm to gently slide the affected arm along the towel's surface. This exercise targets arm mobility and strength, assisting in the recovery process.

An excellent addition to your exercise regimen is seated ball exercises. Sit on a stable chair or at the edge of the bed with a therapy ball placed on a table in front of you. Utilize both hands to apply weight-bearing into the therapy ball, using your unaffected arm for support. Roll the affected arm over the therapy ball, guided by the assistance of the unaffected arm. This exercise promotes sensory input, mobility, and trunk balance while also facilitating transfers.

Incorporate your affected arm as a gross assist whenever possible during daily activities. By practicing reaching for objects, opening doors, or performing simple tasks with the affected arm, you can maintain and improve its functionality in day-to-day living.

Always prioritize safety and comfort during your exercise program. If you experience any discomfort or have concerns about specific exercises, it's essential to consult a healthcare professional for guidance and modification.

Gross Moter HEP Sample

- 30 seated jacks

- 30 seated marches

- *Modification UE only

Incorporating gross motor exercises into adaily routine is an excellent way to stay active and improve overall physical fitness. A simple and effective routine are seated jacks and seated marches, as shown in Figure 9. These exercises are easy to perform and can be suitable for individuals with different fitness levels.

Figure 9. Sample of a gross motor exercise.

To start, have the client do 30 seated jacks, extending their arms out to the sides while lifting both feet off the ground simultaneously. This exercise is a great way to get the heart rate up and engage both the upper and lower body together. Following this, have them try 30 seated marches, lifting one knee at a time in a marching motion, to work on lower body strength and coordination.

As they become more comfortable with these exercises, increase the intensity by timing them - aim to do each exercise for one minute. They can use a timer or rely on voice-activated devices.

To add variety and target specific muscle groups, modify the exercises as needed. Focus on the upper extremities only by performing seated arm jacks, lifting their arms while keeping their feet on the ground. Similarly, concentrate on the lower extremities by doing seated leg kicks, extending one leg at a time. Progress to doing both exercises together simultaneously for a comprehensive full-body workout.

Remember, the key to any exercise program is consistency and gradual progression. They need to listen to their body, and if they experience any discomfort or pain, consider modifying the exercises or consulting a healthcare professional for guidance.

Music-Based HEP Sample

- 1 song of active range of motion or dance 3X per day

- Can use a digital assistant to initiate music

Incorporating a music-based gross movement home exercise program is an enjoyable option for some clients. A recent instance involved working with a client who had a spinal cord injury, limiting their ability to perform exercises without assistance. However, the client could interact with Alexa and request music to play. Capitalizing on this opportunity, a straightforward and effective approach was devised, focusing on active range of motion dance movements that the client could perform for the duration of a single song.

Initially, the client started with one song session per day, gradually progressing to two sessions, and eventually accomplishing three sessions daily. This provided a means to engage in physical activity despite their limited mobility. The simplicity of the movements allowed them to participate actively and independently.

The time element played a crucial role in the program. Recognizing that most songs last approximately three minutes, this provided a structured framework for the exercise routine, making it easy to incorporate into the client's daily schedule.

Overall, this music-based gross movement exercise program served as a fun and effective way for the client to engage in regular physical activity, enhancing their range of motion and overall well-being. By catering to the client's abilities and incorporating music as a motivator, the exercise routine became an enjoyable part of their daily routine.

mCIMT Sample

- Setup activity box to be available on the table

- Complete 30-60 minutes of activities daily

In this exercise, an activity box is set up on a table, using a wooden box or shoebox to contain various fine motor activities. The client is then instructed to wear a potholder on their unaffected arm to encourage the use of the affected arm. The goal is to engage in a half-hour of these activities daily, focusing on improving the affected arm's mobility and functionality.

One effective activity is using clothespins on the side of the box, where the client can practice taking items out of the box and placing them back in. The therapist can adjust the complexity of the activities based on the client's capabilities, ensuring they are appropriately challenged and making steady progress.

By employing this modified CIMT approach, clients can work on strengthening and rehabilitating their affected arm through daily practice and engagement with various fine motor tasks. It provides a structured and effective way to address limitations and promote functional improvement in a controlled and motivating setting.

BUE Integration HEP Sample

- 20 cane pushes

- 20 arm rolls

- 20 arm scissors

- 20 ski arms

I find exercises that involve both arms working together to be highly beneficial for clients, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Sample exercises for bilateral upper extremity integration.

Activities like shoulder and arm rolls, as well as scissor movements imitating Nordic track skiing, are excellent for promoting bilateral integration and coordination.

In addition to these exercises, for clients who require an active assistive range of motion, I recommend incorporating the use of a cane. This can be a valuable tool in engaging the shoulder and trunk muscles. By pushing the cane forward in different directions, clients can target specific areas and promote mobility and strength. They have the flexibility to perform this exercise using one arm or both arms together, based on their individual needs and abilities.

This approach facilitates a well-rounded workout, targeting multiple muscle groups and enhancing overall upper body function. By encouraging clients to participate actively in these exercises, they can experience steady progress and improvements in their range of motion, stability, and strength.

Sample Dual Task HEP

- Pick a category from the sheet

- Provide a sheet with categories

- Complete seated marches while naming as many objects from the category

- Do a balloon toss if a caregiver is available

Introducing dual-task exercises can be more challenging for clients, but they can yield significant benefits for cognitive and motor functions. To facilitate this, you can provide a sheet with categories, and while the client performs seated marches, they can try naming as many objects from a category as possible. This activity enhances cognitive processing and coordination, making it a valuable addition to their therapy.

Involving caregivers in the therapy process can be highly beneficial. Caregivers can learn these dual-task games, such as the balloon toss activity. By engaging in these games together, clients can experience increased social interaction and motivation, making the therapy sessions more enjoyable and productive.

Combining physical exercises with cognitive tasks can be particularly effective. For instance, while the client performs exercises with weights or therabands, they can watch a TV show and challenge themselves to name everything that's blue on the screen. This simultaneous engagement of both systems helps improve multitasking skills, memory, and attention.

By incorporating dual-task exercises into the therapy sessions, clients can work on improving their ability to handle multiple activities simultaneously, which has practical applications in everyday life. These exercises enhance cognitive flexibility and motor coordination, helping clients regain independence and functionality in various activities.

Case Studies

Patricia

- Patricia has a glioma and is referred for home OT. She presents with left homonymous hemianopsia, weakness in her left dominant upper extremity, decreased gross and fine motor coordination, and mild cognitive impairment. Her goals include being able to complete her morning grooming independently and writing her name with her left upper extremity. She has poor balance and walks with a walker.

Our first case study involves a patient named Patricia, though that is not her real name. Patricia has been diagnosed with a glioma and has been referred for home occupational therapy (OT). She experiences left homonymous hemianopia, weakness in her left dominant upper extremity, decreased gross and fine motor coordination, and mild cognitive impairment.

Patricia's therapy goals are centered around regaining independence in her daily activities. These goals include being able to complete her morning grooming routine independently, which involves tasks like putting on makeup, brushing her teeth, and writing her name with her left arm. Due to her poor balance, Patricia uses a walker for walking assistance.

- Patricia Sample Intervention

- Therapy visit structure (45 mins):

- Arrival and vitals (10 mins)

- Gross motor activities: sit to stand x 20, seated marches x 20 (5 mins)

- Dual task activities: lateral stepping at the kitchen counter to retrieve items while completing a category game (15 minutes)

- Tabletop stroke tracing practice followed by writing name 2 times (10 mins)

- Post-vitals and equipment cleaning (5 mins)

- In-between session activities:

- YouTube exercise videos- One seated aerobics and one seated yoga; OT assisted the patient to save the links to Patricia’s iPad for independent access.

- mCIMT box assembled and patient completed 30 minutes daily seated at her kitchen table. Box included cards, a coloring book, a squeeze ball, blocks, dominoes and clothespins to place on the sides.

- Therapy visit structure (45 mins):

Now, let's explore what a sample therapy session for Patricia might look like. Typically, these sessions last about 45 to 60 minutes, but for this illustration, we'll consider a 45-minute session. The session starts with me arriving and taking Patricia's vitals, monitoring her pain level, and checking for any changes in her medication or overall health.

To begin, we engage in some gross motor activities as a warm-up. This includes performing 20 repetitions of sit-to-stand exercises and seated marches. These activities help prepare Patricia's muscles for the rest of the session.

Next, we progress to dual task activities, which are designed to challenge both her cognitive and motor skills. For instance, we might have Patricia do lateral stepping at the kitchen counter while completing a category game. This involves walking forward to retrieve items and then taking three steps backward based on a target or using post-it notes to retrieve specified items.

Moving forward, we focus on more dynamic activities that align with Patricia's specific goals. For example, she might sit at a tabletop and practice tracing various strokes before attempting to write her name using her left arm. During this process, we can utilize action observation, where I demonstrate the strokes first, and then Patricia replicates them before moving on to writing her name. This helps in a parts-to-whole training approach.

As the session nears its end, we conduct post-session vitals and clean any equipment used to maintain a hygienic environment. Additionally, between sessions, I provide Patricia with exercise videos from YouTube. These videos feature seated aerobics and yoga, suitable for her visual and cognitive impairments. I assist her in saving the links to her iPad, ensuring she can access them independently for safe practice.

Furthermore, we assemble a box of materials for modified constraint-induced movement therapy, which Patricia can conveniently access on her kitchen table. This daily 30-minute activity includes ball squeezes, flipping cards, stacking dominoes, and coloring exercises related to her writing goal. We also incorporate clothespins for specific hand exercises.

Perry

- Perry is being seen in his home s/p hospitalization after a fall. He has a past medical history that includes stroke and Parkinson’s disease. Perry is a retired school teacher and enjoys gardening but has been unable to safely go outside. He is currently sleeping in a recliner on the lower level of his home and is walking only short distances with supervision with a quad cane. He has decreased gross and fine motor coordination as well as tremors present. He states he would like to be able to return to gardening outside and has been feeling down over his loss of function.

Our second case study involves Perry, who is receiving home care after a recent hospitalization due to a fall. Perry's medical history includes a stroke and Parkinson's disease. He used to be a school teacher and enjoyed gardening, but his recent limitations have made it unsafe for him to go outside. Currently, Perry sleeps on a recliner on the lower level of his home and can only walk short distances with supervision using a quad cane. He experiences decreased gross and fine motor coordination as well as tremors, and he is feeling down due to the loss of his functional abilities.

- Perry Intervention Plan

- OT works collaboratively with PT to develop a fall prevention plan.

- PT works on balance reactions and ambulation skills.

- OT assesses the environment and provides education on fall prevention strategies during functional activities.

- The OT and Perry set a short-term goal for Perry to be able to walk to the bathroom with distant supervision. The OT ensures the pathway is clear and well-lit.

- The OT works collaboratively with Perry’s wife to get supplies for Perry to start seeds for a summer garden. Perry’s wife is going to talk to their son about getting pots or a raised bed to transplant the seeds at the end of spring.

- OT works collaboratively with PT to develop a fall prevention plan.

In this case, I collaborate with a physical therapist (PT) to develop a fall prevention plan for Perry. The PT is focusing on balance and ambulation while I work on environmental assessment and educate Perry on incorporating fall prevention strategies into his daily activities. We establish a short-term goal for Perry to be able to walk to the bathroom with distance supervision, creating a more controlled environment for initial practice. As a long-term goal, we aim to work towards him being able to participate in outdoor activities like gardening again. To bridge this gap, we involve Perry's wife in the process. She helps gather supplies to start seeds for a summer garden, and their son is approached to arrange for pots or a raised bed so Perry can transplant the seeds when ready.

- Perry- Sample Intervention

- Therapy Visit Structure (40 mins)

- Arrival and Vitals (5 minutes)

- Warm-Up exercises- 1 minute seated jack, 1 minute seated marches, 1-minute finger touches. Instruct to complete after breakfast and lunch as HEP (5 minutes).

- Ambulation to the bathroom with cues for large amplitude stepping. OT educate on UE support while stepping over the threshold and use of a grab bar next to the commode. Practice sitting to stand at the commode x 5. Conclude bathroom practice with hand hygiene at the sink. (10 mins)

- Seed planting at elevated tray table in standing. Walk back and forth to the bathroom to fill up the watering can, practice stepping over an obstacle while carrying the can (15 mins)

- Post-vitals and equipment cleaning (5 mins)

- Therapy Visit Structure (40 mins)

Now, let's consider a sample visit for Perry. As I arrive, the first step is to take his vitals to ensure his health and safety. Then, we proceed with warm-up exercises, engaging in gross motor activities.

Next, we work on ambulation to the bathroom, providing cues to encourage large amplitude stepping. To address potential hazards, we teach Perry to hold onto the threshold while stepping over it and to use a grab bar for support during sit-to-stand movements next to the commode. We practice sit-to-stand at the commode with blocked practice, providing repetition and intensity to enhance motor learning. The session concludes with hand hygiene practice at the sink, incorporating standing balance and occupation-based tasks.

After that, we focus on his gardening goal. Perry stands at an elevated tray table to plant seeds, simulating the activity he enjoys. To incorporate dual-task training, we have him walk back and forth to the bathroom, holding a watering can and possibly stepping over an obstacle to mimic the experience of navigating the garden hose outside.

Throughout the session, we aim to improve Perry's balance, coordination, and confidence in performing daily activities. By setting both short-term and long-term goals and involving his family in the process, we strive to make his return to gardening a realistic and rewarding achievement.

Conclusion

- The need for occupational therapy services to address neurologic deficits in the home is increasing.

- Occupational therapists will use their client-centered creativity to blend neuro-rehab strategies into occupation-based practice.

In conclusion, the demand for therapy services to address neurological deficits in the home is increasing, and Occupational Therapists (OTs) have the opportunity to utilize their client-centered creativity to integrate neuro-rehabilitation strategies into occupation-based practice.

Questions and Answers

Can you please clarify the difference between modified constraint-induced movement therapy and constraint-induced movement therapy?

The main difference between modified constraint-induced movement therapy and constraint-induced movement therapy lies in the dose and the level of arm restraint. When constraint-induced movement therapy was developed, the protocol involved restraining the non-affected arm for six to seven hours a day for 15 days. However, many clients find it challenging to tolerate such prolonged restraint.

In contrast, modified constraint-induced movement therapy still involves some limitations of the unaffected arm, but the dose is significantly lower. It focuses on finding a balance between utilizing the affected arm while also providing some restraint to encourage its use during therapy.

For a client with a newer stroke and some return of function in the upper extremity, would you focus on teaching one-handed dressing techniques or bilateral techniques for lower body dressing?

When working with a client who has experienced a newer stroke and has regained some function in the upper extremity, I would prioritize teaching strategies that incorporate the affected hand as a gross assist. For example, the affected hand could stabilize clothing while the unaffected hand performs activities such as buttoning.

I always aim to find ways to incorporate the affected hand more actively, such as having it reach for and grasp items or performing supported reaching tasks. By using the affected hand as much as possible, we can help redirect the brain's attention to that arm and potentially improve outcomes.

With a modified constraint-induced movement therapy box, do you provide the materials for the client to keep, or do you encourage them to use items they already have at home?

For a modified constraint-induced movement therapy box, I typically provide certain materials like oven mitts, which can be purchased inexpensively from the dollar store and are for the client to keep. However, I also encourage using items readily available in their home for other activities in the box.

Items like coins, silverware, coffee mugs, and shoeboxes can be utilized creatively for sorting, reaching, and grasping exercises. By using familiar items, the therapy becomes more practical and engaging for the client.

What are your thoughts on using high-intensity therapy in the hospital setting?

High-intensity therapy can be beneficial in the hospital setting, but it's essential to consult with the medical team and adhere to established parameters. There are various high-intensity activities that can be incorporated into treatment, such as dual-task exercises involving music, stepping over objects, or ball throwing.

Before implementing high-intensity therapy, it's important to assess the patient's condition and consult with the healthcare provider to ensure it is safe and appropriate for their specific needs.

Can you explain mirror therapy again?

Mirror therapy involves occluding the affected hand with a mirror and then having the client move the unaffected hand. When they look into the mirror, their brain perceives both hands as moving simultaneously, stimulating the part of the brain responsible for movement through visual feedback.

The idea behind mirror therapy is to encourage the brain to reestablish connections related to movement by providing visual input. It can be an intriguing experience to try it out, even using a mirror at home to see the sensation it creates.

References

Academy of Neurologic Physical Therapy. (2018). Intensity matters. Retrieved from https://www.neuropt.org/practice-resources/best-practice-initiatives-and-resources/intensity_matters

Buccino G. (2014). Action observation treatment: A novel tool in neurorehabilitation. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 369(1644), 20130185. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0185

Corbetta, D., Sirtori, V., Castellini, G., Moja, L., & Gatti, R. (2015). Constraint-induced movement therapy for upper extremities in people with stroke. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2015(10), CD004433. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004433.pub3

Foster, E. R., Carson, L. G., Archer, J., & Hunter, E. G. (2021). Occupational therapy interventions for instrumental activities of daily living for adults with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 75(3), 7503190030p1–7503190030p24. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.046581

Geller, D., Nilsen, D. M., Quinn, L., Van Lew, S., Bayona, C., & Gillen, G. (2022). Home mirror therapy: A randomized controlled pilot study comparing unimanual and bimanual mirror therapy for improved arm and hand function post-stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(22), 6766–6774. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1973121

Grandview Research (2022). Home healthcare market size, share & trends analysis report by equipment (therapeutic, diagnostic), by services (skilled home healthcare service, unskilled home healthcare service), by indication, by region, and segment forecasts, 2023 – 2030. Retrieved from https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/home-healthcare-industry

Mateos-Aparicio, P., & Rodríguez-Moreno, A. (2019). The impact of studying brain plasticity. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 13, 66. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2019.00066

Nielsen, T. L., Petersen, K. S., Nielsen, C. V., Strøm, J., Ehlers, M. M., & Bjerrum, M. (2017). What are the short-term and long-term effects of occupation-focused and occupation-based occupational therapy in the home on older adults' occupational performance? A systematic review. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, 24(4), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2016.1245357

Rocha, L. S. O., Gama, G. C. B., Rocha, R. S. B., Rocha, L. B., Dias, C. P., Santos, L. L. S., Santos, M. C. S., Montebelo, M. I. L., & Teodori, R. M. (2021). Constraint-induced movement therapy increases functionality and quality of life after stroke. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases: The official journal of National Stroke Association, 30(6), 105774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105774

Swanson, V. A., Johnson, C., Zondervan, D. K., Bayus, N., McCoy, P., Ng, Y. F. J., Schindele Bs, J., Reinkensmeyer, D. J., & Shaw, S. (2023). Optimized home rehabilitation technology reduces upper extremity impairment compared to a conventional home exercise program: A randomized, controlled, single-blind trial in subacute stroke. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 37(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/15459683221146995

Tedla, J. S., Gular, K., Reddy, R. S., de Sá Ferreira, A., Rodrigues, E. C., Kakaraparthi, V. N., Gyer, G., Sangadala, D. R., Qasheesh, M., Kovela, R. K., & Nambi, G. (2022). Effectiveness of constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) on balance and functional mobility in the stroke population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 10(3), 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030495

VanSwearingen, J. M., & Brach, J. S. (2001). Making geriatric assessment work: Selecting useful measures. Physical therapy, 81(6), 1233–1252.

Welsby, E., Berrigan, S., & Laver, K. (2019). Effectiveness of occupational therapy intervention for people with Parkinson's disease: Systematic review. Australian occupational therapy journal, 66(6), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12615

Citation

Frye, Sara (2023). Neuro rehab strategies in the home setting. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5628. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com