Background and Prevalence

Thank you so much for having me. I am very excited to be here today speaking about this topic. Today, we will cover various lifestyle redesign strategies, focusing on non-pharmacological approaches to managing pain. I want to start with just a little bit of background and prevalence to focus on why this topic is important.

Public Health Concerns

There are essentially two major public health concerns that are an issue right now. One is that chronic pain is being experienced at a very high prevalence, with many costs associated with treating and managing chronic pain. There is also the mental health impact that chronic pain is having. The second public health concern is the high rates of death associated with opioid misuse. There is also the cost of that as well. For those reasons, there is a big need to improve the available treatment options.

Opioid Statistics

- Rise in opioid prescriptions

- Both prescription opioid-overuse deaths & opioid prescriptions quadrupled between 1999 and 2000

- Opioid overdose deaths increased 4-fold over the past 14 years

- Economic burden is approx. $78.5 billion/year

Over time, we have seen a rise in opioid prescriptions. Prescription opioid-overuse deaths and opioid prescriptions themselves quadrupled between 1999 and 2000. Opioid overdose deaths have increased four-fold in the last 14 years. This has resulted in an economic burden of approximately $78.5 billion per year. This is definitely an area of treatment that we want to improve and reduce these negative statistics. One way to do this is by working on non-pharmacological treatment strategies that we will talk about today.

Incidence

- Chronic Pain affects more Americans than diabetes, heart disease, and cancer… combined.

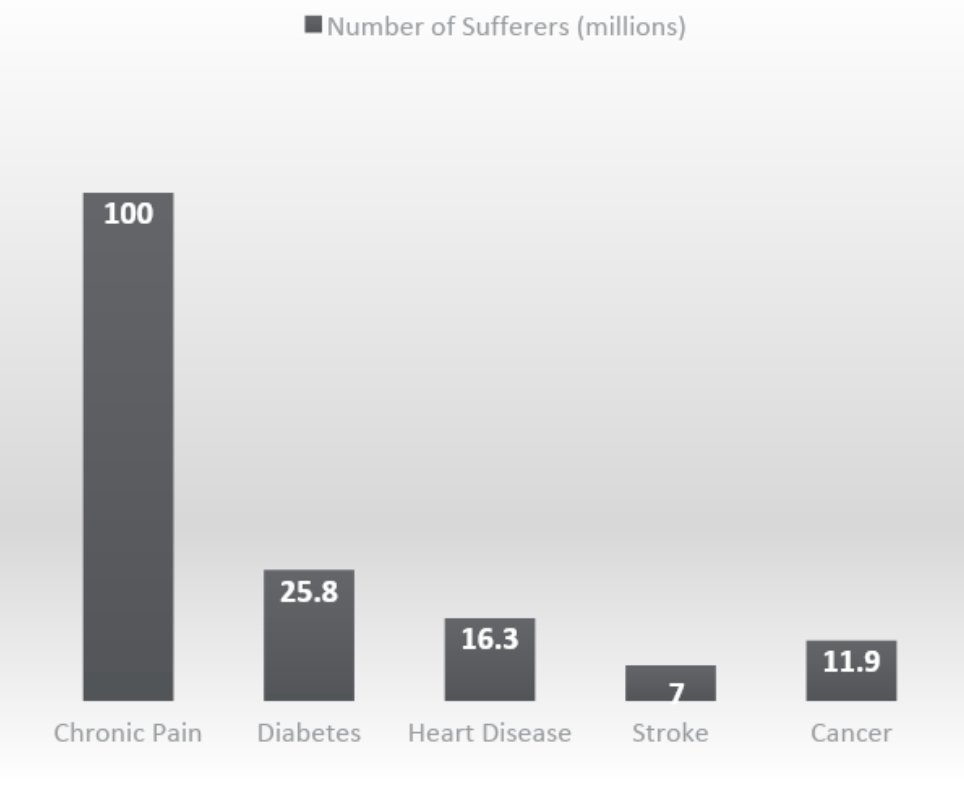

Also, it is important to understand the incidence of chronic pain. Chronic pain is something that affects more Americans than diabetes, heart disease, and cancer combined. More than 39 million people experience nearly daily chronic pain, 25 million have daily chronic pain, and 10 million are disabled because of chronic pain.

Figure 1. The number of sufferers with chronic pain versus other conditions (AAPM, 2013).

Chronic pain is a common diagnosis for which we need to improve treatment.

Impact and Burden of Pain

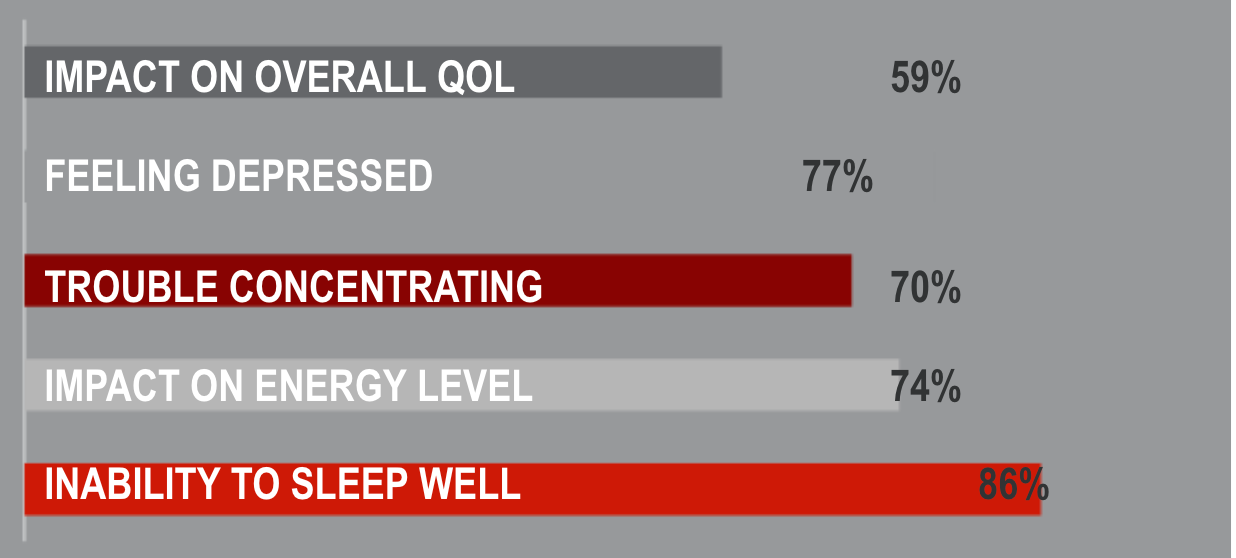

We also need to understand the impact and the burden of living with chronic pain. Some statistics are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Impact and the burden of living with chronic pain (AAPM, 2013; National Centers for Health Statistics, 2006).

Beyond just the pain itself, there are other ways that chronic pain affects a person's quality of life. Rates of depression are really high when chronic pain is present. Patients also report difficulty concentrating. It reduces their energy levels, and it impacts their ability to sleep.

- Annual cost of health care associated with pain treatment: $560-$635 billion/year

- Lost Productive Time From Common Pain Conditions Estimated Annually To Be- $297.4 to $335.5 billion

- Days of work missed- $11.6 to $12.7 billion

- Hours of work lost- $95.2 to $96.5 billion

- Lower wages- $190.6 to $226.3 billion

- Most pain-related lost productive time is due to reduced performance rather than absenteeism

(Simon, L. S. 2012; American Academy of Pain Medicine, 2011)

As a result of that impact, we see the estimated cost of treating a person with chronic pain as high as 560 to $635 billion per year. This makes it both a medical issue that we need to address and a public health concern. This is a combination of medical care and economic costs related to disability days, wages, and lost productivity. The Institute of Medicine report indicated that the annual value of lost productivity was 297 to $335 billion per year. This was due to things like missed hours and days of work lost, and lower wages. If we think back to how chronic pain impacts a person's daily life, like sleep, energy, and ability to concentrate, we can imagine how difficult it would be to work effectively.

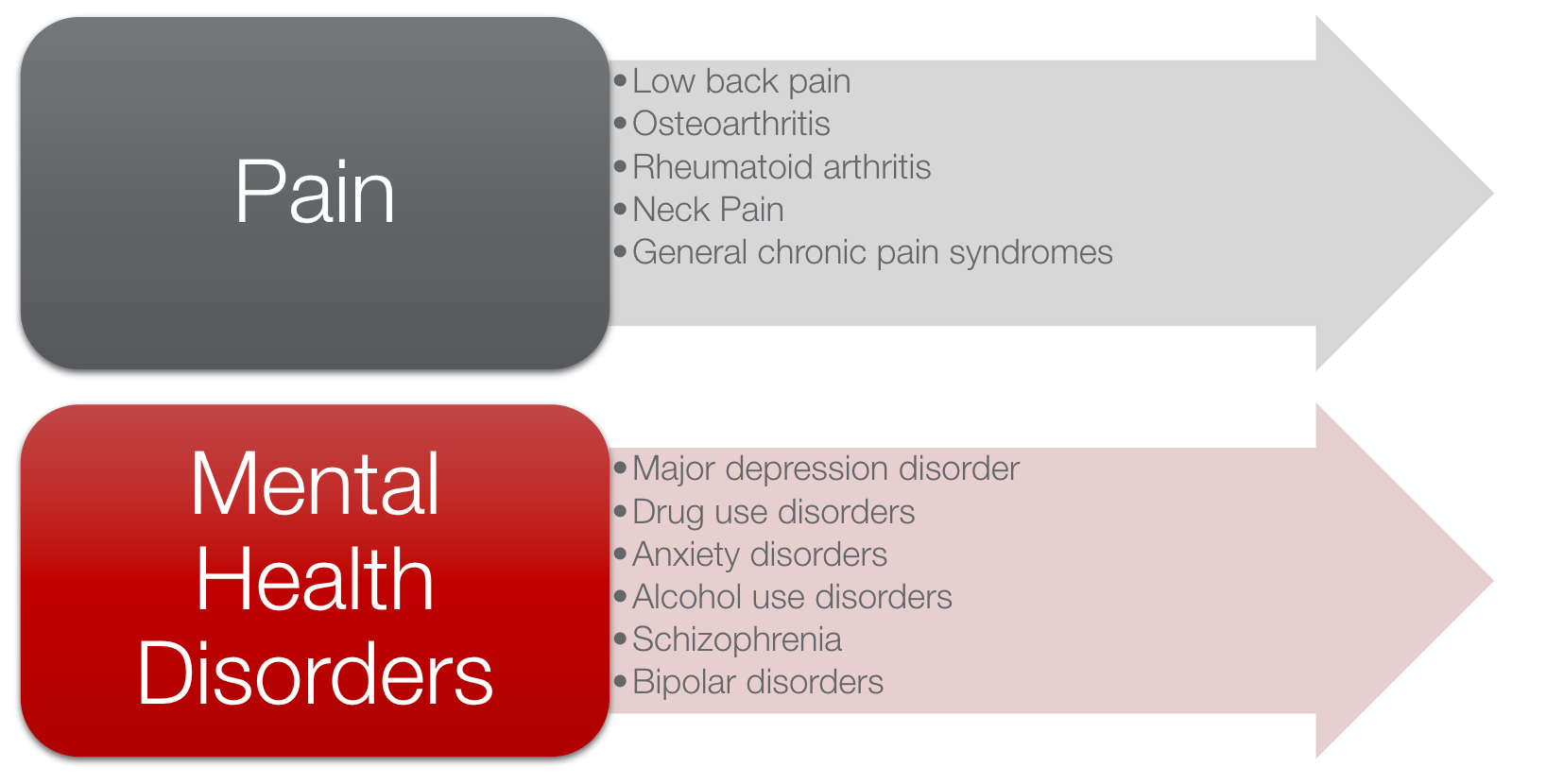

Disability: Pain and Mental Health

This also relates to disability rates, as noted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Disability causes (Phillips, C. J., 2009; AAPM, 2013; Woolf, A. D., & Pfleger, B., (2003); Murray, C. J. et al., 2013).

The two leading causes of disability are musculoskeletal disorders that cause chronic pain and mental health conditions. This graphic also highlights the need to effectively address the mental health aspects of living with chronic pain. Both of these conditions contribute to high rates of disability. I am excited to speak about this because there really has been a national call for improving the treatment options for chronic pain conditions.

National Pain Strategy

- Improve treatment for pain:

- Improve the prevention and management of pain

- Develop a system of patient-centered integrated pain management practices based on the biopsychosocial model of care

- Minimize barriers to pain care

- Increase public awareness of pain

- Improve patient knowledge

- Improve healthcare provider training for pain management

(Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee, 2015)

With the opioid crisis and the lack of effectiveness of opioids for treating chronic pain, there have been some efforts to address this, including the National Pain Strategy. These clinical practice guidelines were created to help improve the treatment for this population. The US Department of Health and Human Services released this national pain strategy, and it outlined some of those recommendations. First and foremost, it focuses on the prevention of pain. This is going to mean better care if we can prevent the onset of pain. We also want to learn how to manage it better. This is using a patient-centered client-centered approach that is focused on a biopsychosocial model of care. It also looks at the barriers to pain care. With telehealth options being a little more readily available, this has helped reduce some of those barriers. It includes increasing the public's awareness of pain. I think patient knowledge is crucial. We will talk a little bit about that in treatment interventions. We also need to improve healthcare provider training for pain management. This is what we are doing today.

Pain Pathways

- Afferent pathways-Nociceptor registers pain signal and transmit pain information to the CNS

- Central Nervous System-CNS evaluates and interprets the information

- Efferent Pathways-Interpretation of the pain is sent through efferent pathways to the periphery

To treat pain, we have to understand the process and how chronic pain comes to be. Typically, when a person experiences pain, pain is registered in the afferent pathways. Nociceptors in our periphery get activated when they are exposed to a pain stimulus. When those receptors turn on, they send a signal or message to the brain through afferent pathways. Once that information gets to the central nervous system, the brain evaluates and interprets it and then decides what to do with it. It sends a message back out through efferent pathways to the source of where the stimulus is coming from and tells us what to do, maybe removing our hand from that fire or removing ourselves from that painful stimulus. This is how pain should be processed.

Chronic Pain and Central Sensitization

- Chronic pain=Dysfunction of the nervous system-->Central sensitization

- What is Central Sensitization?

- Heightened reactivity due to exposure to persistent and prolonged pain signaling

- Allodynia: when a person experiences pain with things that are not normally painful

- Hyperalgesia: when an actual painful stimulus is perceived as more painful than it should be

- Heightened sensitivity to pain and other sensory input (light, sound, smell, touch)

- Other changes in the brain: cognitive deficits, poor concentration, poor short-term memory

- Heightened reactivity due to exposure to persistent and prolonged pain signaling

(McCaffrey, R., Frock, T. L., & Garguilo, H., 2003)

With chronic pain, the signaling system is not functioning properly. Instead, the nociceptors (pain receptors) are activated without an immediate stimulus. The pain signal is constantly being sent to the brain. Over time, this results in a heightened reactivity because of the prolonged and persistent exposure to that pain signal. Essentially, it becomes a dysfunction of the nervous system. This can lead to things like allodynia and hyperalgesia.

Allodynia is when a person experiences pain when things are not normally painful. And, hyperalgesia is when an actual painful stimulus is perceived as more painful than it should be. These indicate what we call central sensitization, or the heightened reactivity due to exposure to a prolonged, persistent pain signal.

Separate from changes in our pain signaling system, central sensitization is also associated with sensitivity to other sensory inputs, like light, sound, or smell. It has also been associated with other brain changes, like cognitive deficits, poor concentration, and poor short-term memory. Thus, it can have a wide effect beyond just the pain signaling system itself.

Pain Modulation

- Gate Control Theory

- Pain perception can be altered by:

- Emotions

- Prior experience with pain

- Anxiety

- Pain perception can be altered by:

- Neurotransmitter Modulation:

- Serotonin, Norepinephrine, Endorphins, Enkephalins, Substance P

(McCaffrey, R., Frock, T. L., & Garguilo, H., 2003)

Once that pain signal gets to the brain, and the brain interprets and makes sense of it, there are two main theories about how pain gets modulated. One is the Gate Control Theory. In a simplified description, the brain has gates that are either open and allow the pain signal to go back through those efferent pathways to the periphery, or those gates are closed and block that pain signal at the level of the brain. Circumstances that influence these gates and whether they are opened or closed are things like a person's emotional state, their prior experiences with pain, and the presence of anxiety. Educating patients about that helps them understand the relationship between our mental health state, our thought patterns around pain, and how that can keep those pain gates open, further facilitating that pain signal.

The other pain modulation theory is the Neurotransmitter Modulation Theory, which focuses on how these different chemicals and neurotransmitters influence pain. They can either increase that pain signal or help to reduce it. I think an example that a lot of people are familiar with is endorphins. Endorphins are our body's natural painkillers. Exercise is an example of how to release endorphins naturally. When we engage in emotionally pleasurable things such as laughing, hugging, quiet relaxation, or meaningful occupations, we will see an increase in endorphin release. This is another tool that I think is helpful for patients to understand. Engagement in activities releases endorphins to block pain signals and reduce that experience of pain. Education around how pain is modulated can be really beneficial.

Factors That Affect the Experience of Pain

- Act indirectly on pain:

- ↓ activity

- ↓conditioning

- ↑ nociception

- ↑sympathetic nervous system activation

- ↑ muscle tension

(Weinstein & Axtell, 2016)

Some other factors that affect the pain experience are decreased activity, decreased conditioning, increased nociception, and increased sympathetic nervous system activation. If someone is experiencing a chronic stress episode, that increased sympathetic nervous system activation can affect the experience of pain and increase muscle tension. This can further increase the pain experience.

Psychosocial & Behavioral Factors that Affect the Experience of Pain

- Mood

- Depression and anxiety are common comorbidities

- Trauma history

- Childhood trauma increases the likelihood of developing a chronic pain disorder

- Occupational engagement

- Decreased activity, fear-avoidance behaviors, decreased conditioning

- Marital Issues

- Solicitous spouse assoc. w/ ↑ pain perception

- Communication Style

- Passive/assertive/aggressive

(Weinstein & Axtell, 2016)

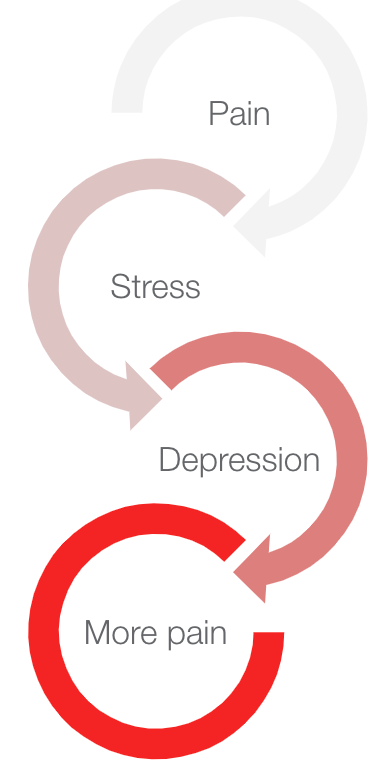

Some psychosocial and behavioral factors also affect the experience of pain. For mood, the evidence shows that depression and anxiety are prevalent comorbidities. Up to 50% of chronic pain patients are depressed or experienced anxiety. Another factor is the history of trauma. Suppose a person reports a history of childhood trauma, for example, that increases the likelihood of developing a chronic pain disorder. A person's level of occupational engagement is another. If a person demonstrates avoidance or sedentary behaviors due to a fear of triggering pain, it will worsen. Some interesting research shows that having a solicitous or overly attentive spouse can actually increase pain perception. The last factor is communication style. If a person is passive in their care and just waits for solutions to fix their problems or are they very assertive and able to ask for help, these can play a role as well.

Cognitive Factors that Affect the Experience of Chronic Pain

- Appraisal, beliefs, expectations (about pain and function)

- Catastrophizing- exaggerated negative orientation toward actual or anticipated pain experiences and function

- Coping- passive vs. active

- Control and self-efficacy

(Weinstein & Axtell, 2016)

Looking at some cognitive factors, a person's beliefs about pain and their expectations about pain and function affect the experience of chronic pain. Pain catastrophizing is the tendency to describe a painful experience in a more exaggerated way than the average person or to ruminate on it. This is a predictive factor for understanding the chronicity of their pain experience, and it is associated with a poor prognosis. We also want to know how a person is coping. Are they more passive, or are they a little bit more active in that pain management process? What is the person's own sense of control and their own belief in their self-efficacy? Much of the treatment that we will cover today is really focused on increasing a person's self-efficacy and confidence in their ability to manage their pain by giving them the tools that can help them reduce their pain or cope with it more effectively.

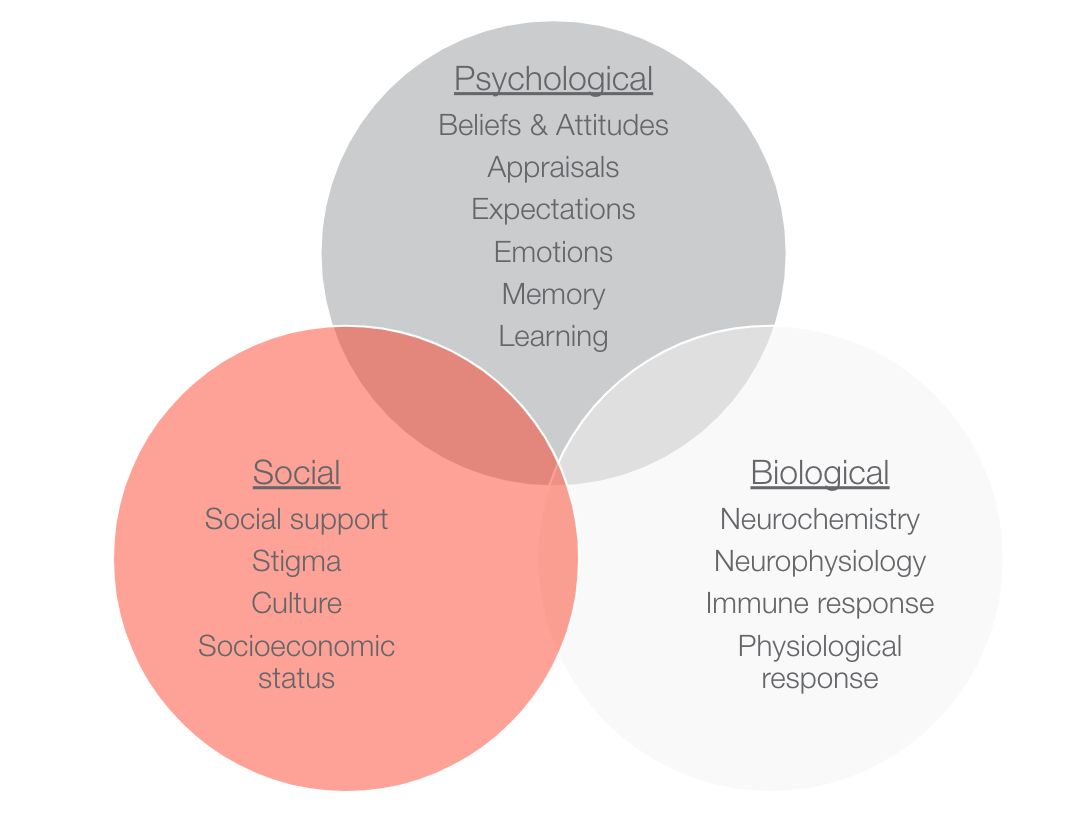

Biopsychosocial Approach

Understanding the physiological impacts of pain and how cognitive and emotional states influence pain, the biopsychosocial approach, in Figure 4, is the recommended approach for treating chronic pain.

Figure 4. The biopsychosocial approach to pain.

We have to address every one of these factors to improve pain management.

Lifestyle Management Strategies for Chronic Pain

We will focus on lifestyle management strategies that are shown to be effective for improving pain management.

OT Intervention

I will address all of these different treatment areas to give you guys an idea and a sense of where you can start with your patients (Figure 5).

Figure 5. OT treatment areas to address with a lifestyle management approach.

Patient Education: Understanding Chronic Pain

Once I do an initial evaluation with patients, I start with a session that is focused on patient education. It is such an important part of treatment to ensure that the patient understands what is going on physiologically. They can then start to increase their own awareness of what triggers to look out for, what things exacerbate their pain, and how their thoughts and cognitive factors could be influencing their pain experience. I think this should be a starting point. It helps to get the patient involved early on in wanting to make changes and improving their self-efficacy. They can do things within their control, outside of their medications, to help manage their pain. You can educate them about the Gate Control Theory and the Neurotransmitter Modulation Theory.

- Understanding the Impact of Pain

- Factors associated with chronic pain. Keep in mind that these are all two-sided relationships!

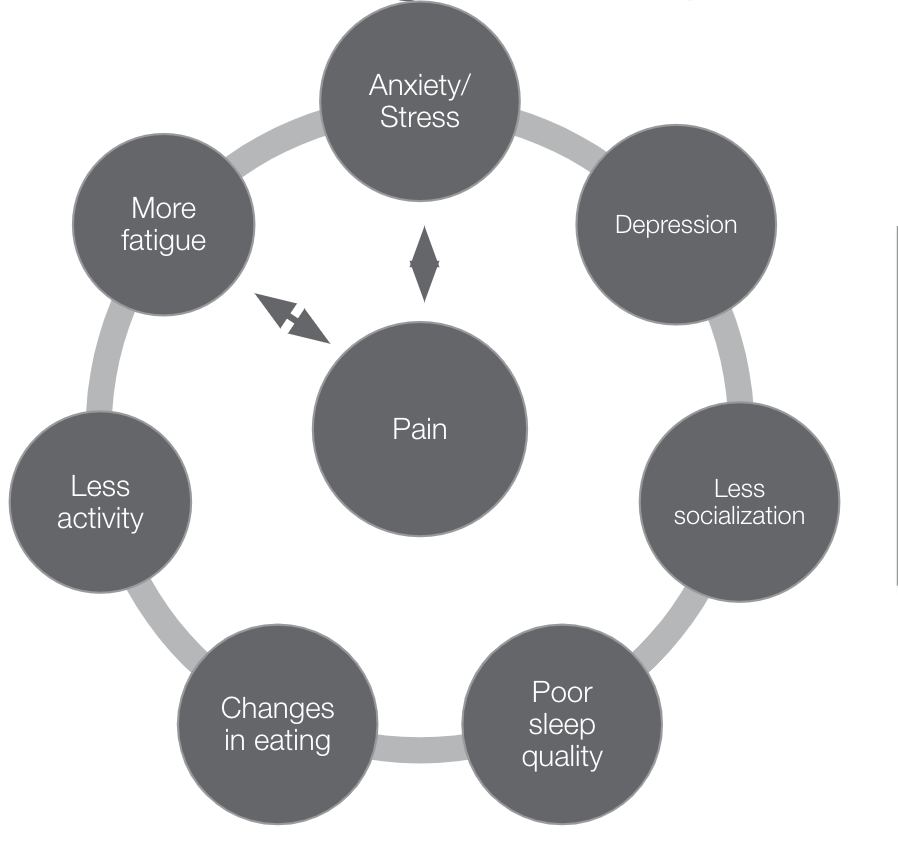

In that patient education session, I will also help patients understand this two-way relationship between pain and these lifestyle factors (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Factors associated with chronic pain.

We know, for example, that anxiety and stress are widespread triggers of pain, but pain can also increase a person's stress and anxiety. It is a two-way cycle. Similarly, another example is sleep. Pain can make sleep challenging, but if a person is not getting good quality sleep, their pain sensitivity can be higher. Using a lifestyle management approach, we will work on managing stress, sleep routines, and eating habits. Addressing each of those areas on the outside of the circle will positively influence pain as well.

- Self-Management Interventions for Pain

- Change Psychological Factors

- Thoughts & behaviors (thoughts, emotions, & behaviors are cyclical!)

- Awareness of the current situation

- Coping techniques

- Relaxation techniques

- Avoid, fix, or let go of stressors

- Build social support and community resources

- Have HOPE (it's scientifically proven!)

- Change Behavioral Factors

- Choice of daily activities

- Pacing and energy conservation

- Ergonomics and posture

- Exercise and eating routines

- Stretching, massage

- Get more sleep

- Practice good self-care routines

- Do something outdoors every day

- Create a team of professionals to help

- Change Psychological Factors

Another part of that patient education piece is self-management strategies. Pain is a very multidimensional experience and can affect the biopsychosocial levels of a person's experience. It is important to highlight that we can do things psychologically and behaviorally to improve pain management. We can address a person's thoughts, behaviors, and coping techniques, like relaxation, that they are using. We can also change the behavioral factors of pacing and getting good sleep, using good ergonomics and body mechanics, and things like that. I think seeing these options helps people understand, "Oh yeah, there are things within my control that I can do."

- The Power of Occupation

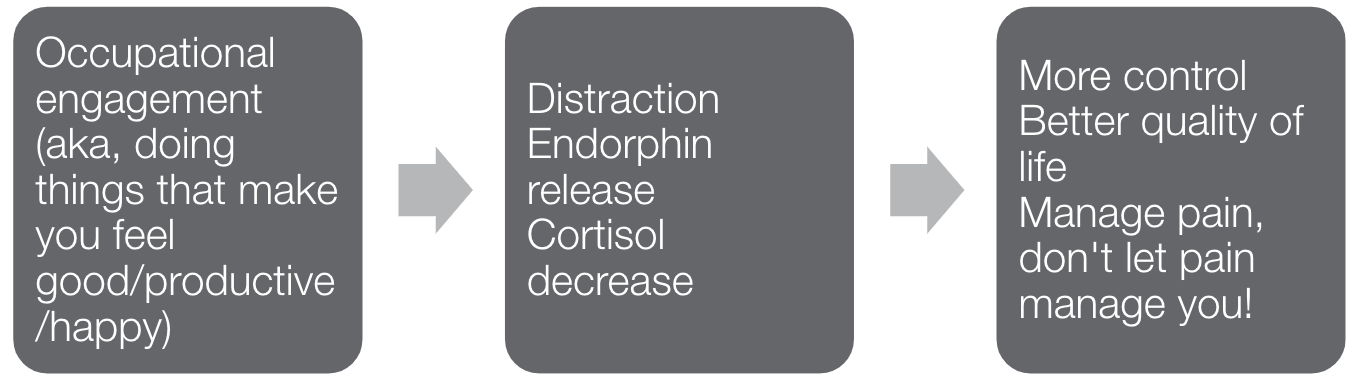

Lastly, I always like to highlight just the power of occupation and help people understand that.

Figure 7. Power of occupation.

When they are engaged in meaningful and purposeful activities, this leads to positive distraction from the pain. It causes endorphins (natural painkillers) to release and cortisol levels to decrease. This physiological response leads to better control, increased quality of life, and better self-efficacy.

Pain Tracking

After the patient education piece, I like to work with patients to build awareness using pain tracking.

- Electronic Resources:

- CatchMyPain

- My Pain Diary

- PainScale (free)

- Pain Diary App (free)

- ACPA “Live Better with Pain” Log

There are several different tools available to help patients engage in tracking. Some people like written logs while others like electronic versions. Helping the patient figure out the system that is going to work best for them is really important. Figure 8 shows a log for headaches.

Figure 8. Example of a pain log to track headaches.

When a patient starts a pain log early on, it helps build their awareness of the patterns in their pain onset, and it helps them pay a little more attention to the things that trigger and manage their pain. This is where I think the buy-in really comes. They have that information and can look at that data. They are going to feel a little more motivated when they can monitor this. It is also great for us to look at that data to inform our treatment and the direction we want to go as it is such an individualized experience.

Chronic Pain and Energy Management

- Pacing interventions found in rehabilitation literature based on biophysiological and biomechanical principles

- Jeanne Melvin: an OT using energy conservation to manage generalized fatigue with patients with rheumatic diseases

(Mclean, Coutts & Becker, 2012)

The next treatment area that I commonly address is energy management/activity pacing. Fatigue is a prevalent symptom that people living with chronic pain experience. If we think about the pain signaling system that is not functioning properly with our brain constantly receiving this pain information, you could imagine how energy-depleting that might be. If our brain is constantly having to make sense of what to do with this information and assess if it is an actual threat, you could see that it would be fatiguing. And, many people with chronic pain do report fatigue. One of the interventions focuses on pacing and energy conservation strategies.

These are interventions found in rehabilitation literature that are based on biophysiological and biomechanical principles. Jeanne Melvin is an OT who first wrote about energy conservation strategies. Initially, her focus was on helping patients with rheumatic diseases to manage generalized fatigue. Since then, there has been a lot more information beyond just energy conservation. One is activity pacing. This is such an appropriate tool for occupational therapists to use with their patients. There is a lot of evidence supporting activity pacing.

- Evidence Supporting Activity Pacing

- Headache:

- Pacing was effective for "preventing increases in headache intensity (70%), decrease headache intensity (65%), and shorten the duration of a headache (40%)" (McLean, Coutts & Becker, 2012, p.611).

- Fibromyalgia:

- Patients who increased the use of pacing strategies showed improvements in pain severity and emotional distress (Nielson & Jenson, 2004).

- Chronic low back pain:

- Pacing is an "absolute necessary part of living with CLBP...because without pacing oneself, the pain would become insurmountable and they would become fatigued" (Stensland & Sanders, 2018, p. 1440).

- Headache:

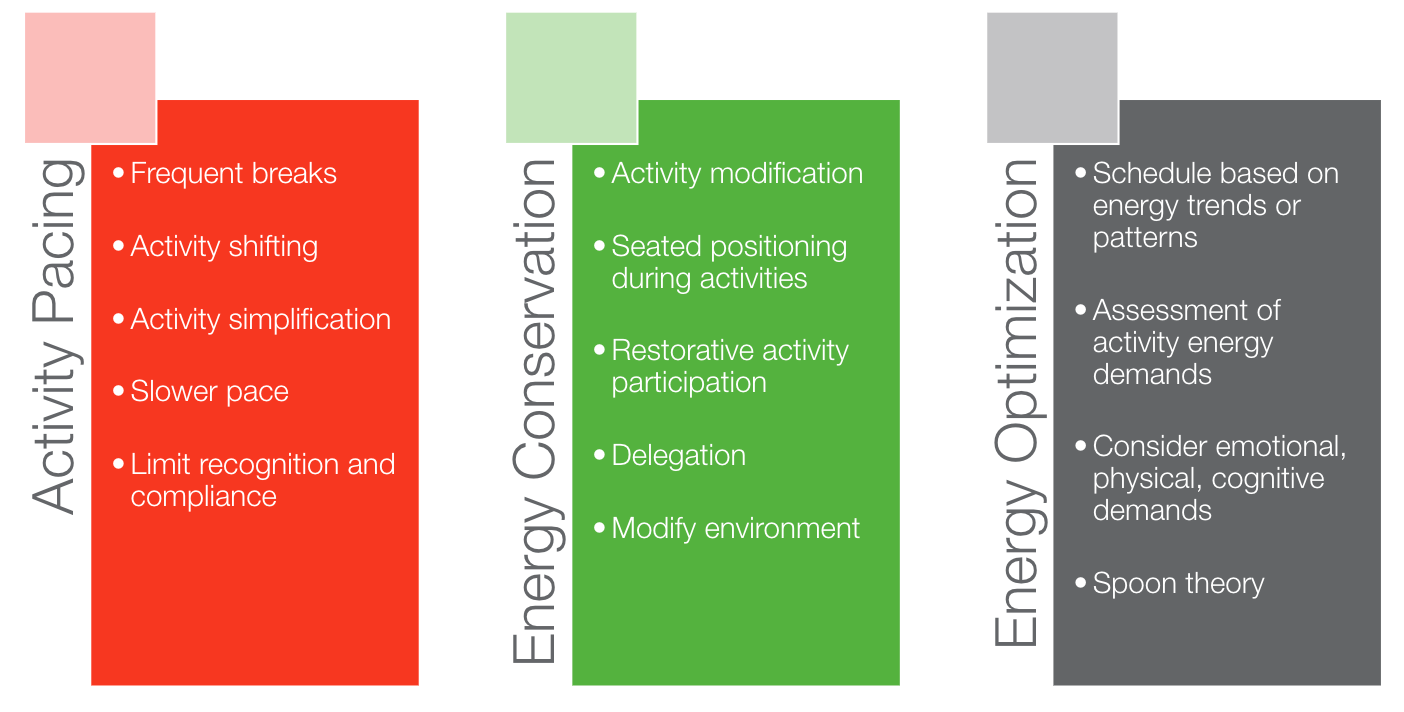

In patients with headache pain, pacing was shown to be effective for preventing an increase in headache intensity, reducing headache intensity, and shortening the duration of a headache episode. For patients with fibromyalgia, pacing resulted in improvements in pain severity and emotional distress. Patients with chronic low back pain reported that pacing was necessary to reduce fatigue. When we think about interventions and what we can do in our OT treatment, it can fall into one of three categories (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Activity pacing, energy conservation, and energy optimization.

- Activity Pacing

- Activity Shifting

- Frequent breaks

- Slower pace

- Activity simplification

- Limit recognition and compliance

Pacing strategies focus on modifying the activity and balancing between low, moderate, and high demanding activities throughout the day. It is also about taking frequent breaks throughout an activity and moving at a slower pace, so it is not as energy-demanding. It is also about finding ways to simplify activities. An example might be that instead of cleaning the whole house on a Sunday, only doing one room at a time throughout the week. This recognizes that limits need to be set.

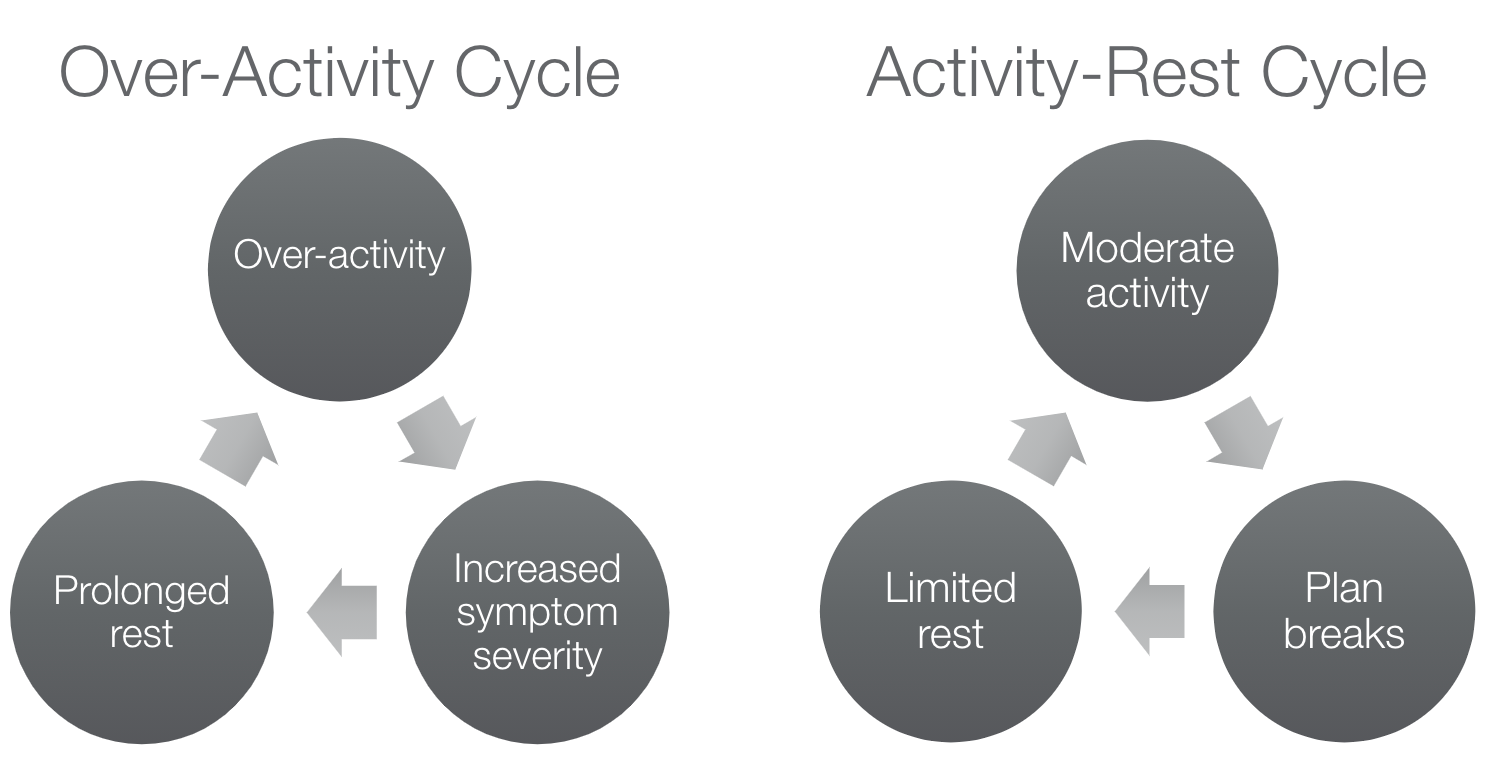

Many patients report pushing through an activity until the end without ever checking in throughout the activity itself. If we check in more frequently and recognize the onset of early pain or fatigue, we can set limits to avoid the trigger of a more severe pain episode. An example of that is the overactivity cycle shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Overactivity cycle versus activity-rest cycle.

Perhaps, on days when clients feel good, or their pain is better managed, they might be more at risk for overdoing it. They might want to check everything off their to-do list that day. However, the consequence of that is it leads to increased symptom severity. Our brain gets familiar with a higher pain intensity, which can lower a person's pain threshold over time. Then, there is a need for a prolonged rest period. After a prolonged rest period, a person might be at risk for overdoing it because they have had a few days not to do the things on their to-do list. It is a cycle that feeds into itself. Alternatively, we want to train patients in more of this activity-rest cycle. This cycle is moderate activity with planned rest breaks in advance. At the earliest warning sign of their pain onset, they take more frequent but shorter rest breaks. This way, they can get back to their activity without recovering from a prolonged pain episode. We want to help patients learn how to approach activities using this approach.

- Energy Conservation

- Activity modification

- Seated positioning during activities

- Restorative activity participation

- Delegation

- Modify environment

This can be things like modifying activities using adaptive equipment or equipment (like tub benches and seats) that make the task easier. Or doing things seated versus standing. It could also be engaging in restorative occupations that give us energy back rather than deplete energy. Delegating tasks and modifying the environment can also improve energy management.

- Energy Optimization

- Schedule based on energy trends or patterns

- Assessment of energy demands for activities

- Consider emotional, physical, cognitive demands

- Spoon theory

Figure 11 shows some questions we can ask to assess energy optimization.

Figure 11. Energy optimization considerations.

Energy is a little bit hard to measure. However, if we can start to analyze our energy levels throughout the day, that can help. One concept that is common in the chronic condition world is the spoon theory. This is a theory that helps us evaluate, on any given day, how much energy ("spoons") do I have available to myself. And based on that, how am I going to plan my day accordingly so that I am not depleted of all of my energy resources.

We can also look at different sources of energy. Does a certain task require physical, cognitive, or emotional demands? It also considers patterns in a person's energy levels. If a person finds that their highest energy is mid-afternoon, they may want to plan activities based on that energy pattern.

You can do activity pacing and energy management strategies to help clients avoid the trigger of pain and help them manage their fatigue more effectively.

- Secondary Fatigue Management

- Sleep routines

- Eating routines

- Managing stress

- Ergonomics and body mechanic training

- Adaptive equipment training

- Time management and lifestyle balance

- Medication mgmt. routines

- Assertive communication strategies

We also need to consider secondary factors that can compound fatigue or make their fatigue experience worse. We want to look at their sleep, eating, exercise routines, level of stress, lifestyle balance, and managing their time throughout their day. For instance, medication side effects could be contributing to fatigue. I like to educate patients about these secondary factors to assess if they think anything could make their fatigue symptoms even worse. And if so, then problem-solving through how to manage those sources of fatigue.

Chronic Pain + Mental Health Comorbidity

Another important area is addressing stress and the management of any mental health comorbidity. Some of the factors are listed in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Mental health as a comorbidity with pain (Gureje, 2008).

The presence of pain and mental health comorbidity tends to have worse outcomes than if someone experiences pain alone. These clients also have higher rates of disability. They may respond less favorably to rehabilitation services, and pain can complicate mental health treatment. We must address both components of the pain experience. The benefits of treating both pain and mental health are that it impacts a person's self-efficacy and ability to feel confident in their management and ability to engage in occupations.

- Treating Pain and MH

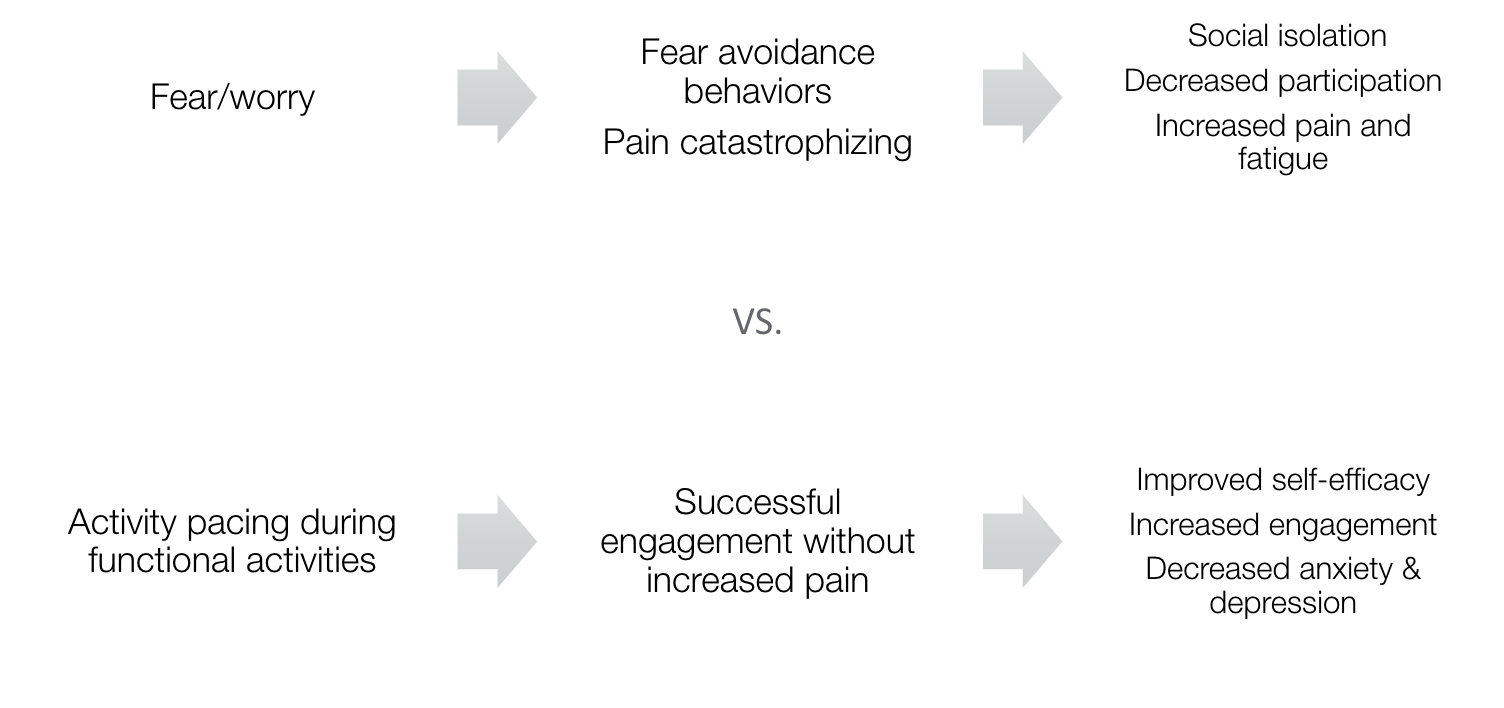

A common process during the initial evaluation is a patient might be experiencing fear and worry about their pain. This graphic was from AOTA in 2013.

Figure 13. Treating pain and mental health (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2013).

Many report fear-avoidance behaviors or pain catastrophizing thoughts and are at risk for social isolation. They are often not engaging in their meaningful occupations, making their pain and fatigue worse. If we educate patients about pacing strategies and how to manage stress more effectively, then hopefully, they will utilize pacing and stress management strategies during functional activities to allow them to engage successfully. As a result, they have more self-efficacy and continue to engage in their occupations using those tools. We also see a reduction in their anxiety and depression. That is how we want these treatment strategies to influence activity participation. I want to help my clients successfully engage in activities that they may have been previously avoiding, building their confidence.

Stress Management

- Sympathetic activation & pain cycle

- Pt education:

- Fight or Flight vs. Relaxation Response (helps explain why relaxation techniques help)

- Stress <-----> Pain

For stress management, I always start with patient education. I explain to clients the two-way relationship between stress and pain and how stress or pain (or even the thought of stress and pain) activates the sympathetic nervous system. It might not feel like they are experiencing stress necessarily, but they are experiencing pain, which indicates that their fight or flight response is turned on. Whether it is to treat stress or pain, relaxation techniques and other stress management strategies will help turn off that sympathetic nervous system and turn on the relaxation response. This is why relaxation techniques are effective, not only for stress management but also for treating pain. I give them the background information about the fight or flight response versus the parasympathetic rest and digest response.

- Stress trigger identification

- Remediate if possible

- Understanding signs and symptoms of stress

- Self-regulate sooner

- Healthy coping strategies

- Relaxation training

Figure 14. Stress triggers and pain.

The goal is to help patients recognize when they are experiencing stress and when they are in fight or flight mode. First, by understanding their triggers and the signs and symptoms of stress, they can recognize it sooner. They will be able to implement self-regulation strategies closer to the onset of that stress rather than ignoring or pushing it.

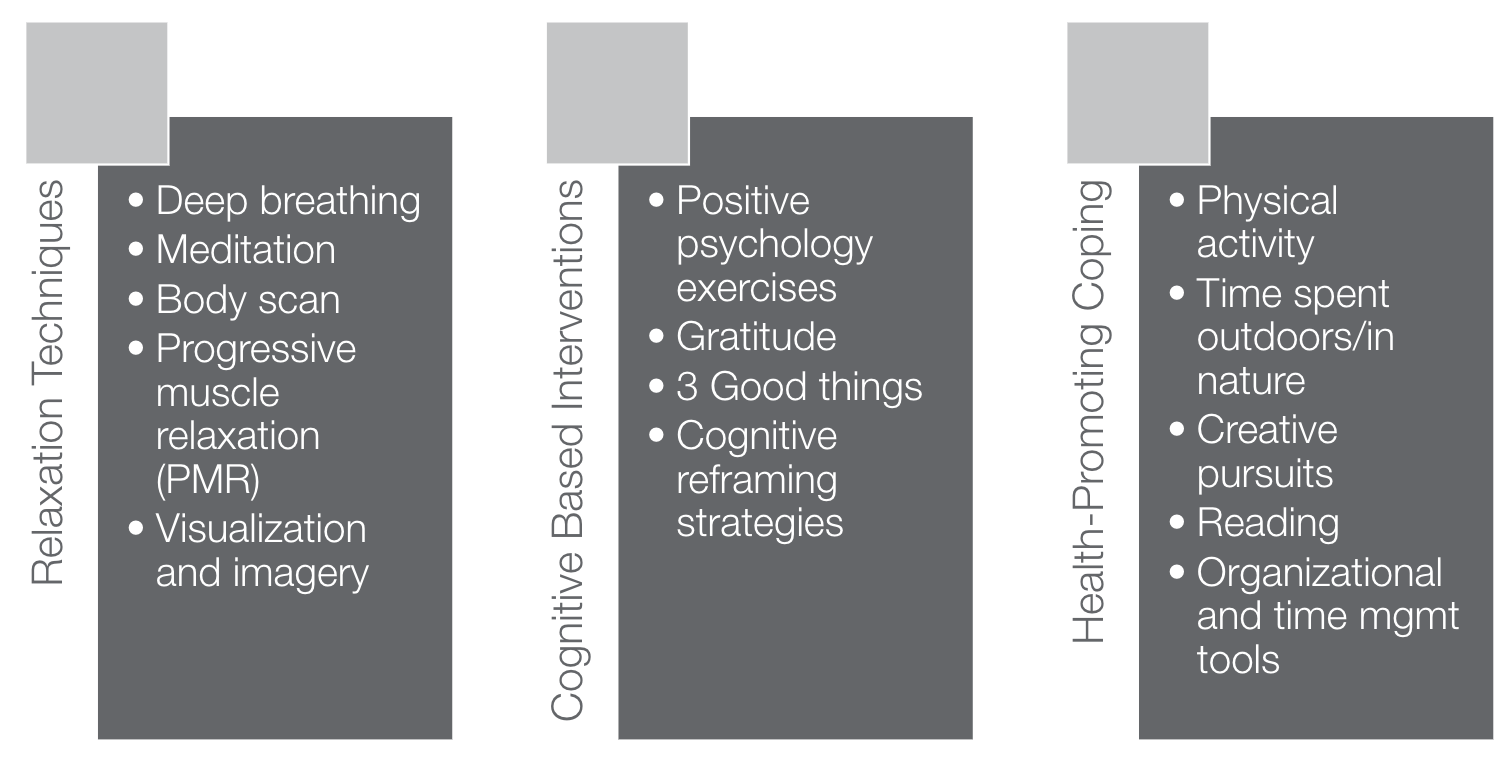

- Chronic Stress Interventions

Once they have an awareness of triggers and signs and symptoms, we can give them the tools to use once they notice them. These are outlined in Figure 15.

Figure 15. Stress reduction tools (Bowling, 2013; Foley & Sarnoff, 2015)

These tools fall under three areas relaxation techniques, cognitive-behavioral interventions, and health-promoting coping strategies. In that category of relaxation techniques, we can train clients to utilize different relaxation techniques like deep breathing, meditation, etc. They can find the coping strategy that works best for them. Cognitive-based interventions might be reframing their thoughts to reduce catastrophic thinking, gratitude exercises, and positive psychology exercises. Other health-promoting coping strategies include exercising, getting sunlight and vitamin D, spending time in nature, engaging in creative pursuits, managing time more effectively, and having a better lifestyle balance.

Sleep and Pain

- Why sleep matters?

- Release of hormones (human growth hormone, cortisol)

- Metabolism

- Memory, emotional health, concentration, motor function

- Immune system

- Prevent and manage fatigue

- Decrease risk for chronic health conditions

(Hester, J., & Tang, N. K., 2008; Straube & Heesen, 2015)

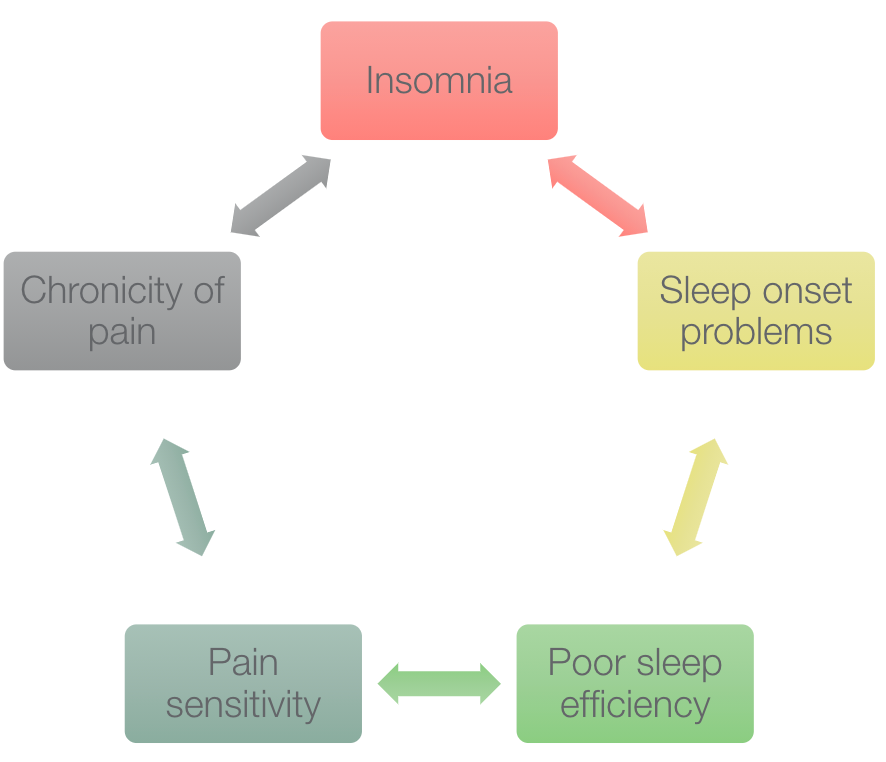

Sleep plays a huge role in the management of pain. Sleep is so important that it is really the only time that our brain is turned off and not getting that pain signal. It also gives our brain time to repair itself. While we are sleeping, we are getting a release of hormones, our metabolism restores itself, and we are getting benefits to our memory and emotional health. When sleep is disrupted, it can increase the risk for stress triggers, headaches, and more chronic health conditions. It can be a vicious cycle. Poor sleep efficiency can increase pain sensitivity and increase pain chronicity, as seen in Figure 16.

Figure 16. A cycle of poor sleep and pain.

- Sleep Routines

- Evidence demonstrates a relationship between poor sleep quality and fatigue

- Interventions:

- Sleep hygiene

- Stimulus control

- Self-regulation training

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

- Contraindicated for patients with epilepsy, bipolar disorder, fall risk

Bladder management strategies

(Trojan, Arnold, & Collet, 2007)

When patients are living with chronic pain, it also influences their sleep routines. There is definitely a relationship between poor sleep quality and fatigue, and higher pain sensitivity. As far as interventions go, we can focus on sleep hygiene training and look at the routines and behaviors around sleep that support or interfere with sleep. An example of stimulus control is being on our phone in bed. This causes a behavioral reaction where our brain associates activity with our bed. This can keep us awake through the night. We can do some self-regulation training to promote relaxation before bed. Some occupational therapists are specifically trained in cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). If CBT-I is an appropriate treatment, there are things like sleep restriction guidelines that we can recommend for improving their sleep quality. If nocturia or waking up to go to the restroom through the night is a barrier, we can also address bladder management strategies. Also, something that is not listed here is looking at sleep positioning strategies. There are things to help reduce pain during sleep, like pillow supports, positioning strategies, stretching before bed, and the like.

Eating Routines

- Pain

- Decreased appetite/skipping meals

- Emotional eating/overeating

- Overweight and obesity

- Dietary triggers

- Pain as a limiting factor for meal preparation/grocery shopping

Causes:

- Impaired energy levels

- Further dysregulation of the nervous system

(Okifuji, A. et al., 2010)

Pain can affect eating routines as it leads to decreased appetite or skipping meals. Alternatively, a patient might cope through food. There might be emotional eating or overeating. Being overweight or obese can increase pain levels due to excess pressure on the joints and the extra load that people are carrying. A lot of people also experience specific dietary triggers that make their pain worse. Pain can also be a limiting factor that prevents or interferes with a person's ability to engage in meal preparation or grocery shopping.

- Eating frequency (about every 2-3 hours)

- Blood sugar regulation (especially in migraines)

- Food choices

- Fluid intake– Water, Caffeine, Alcohol

- Simple meal prep strategies

- Identifying food triggers and elimination diet

- Weight management

- Activity pacing and adaptive equipment

If eating routines are not well-regulated, it can further exacerbate fatigue and dysregulates the nervous system. This is definitely an area we want to improve to regulate blood sugar and manage energy to reduce that pain experience. We may work on eating frequency or how often a person is eating throughout the day to manage their blood sugar levels. We can also look at food choices and make sure clients are hydrated to eliminate dietary triggers.

If meal preparation or grocery shopping is a challenge, we can also look at adaptive and compensatory strategies for engaging in meal preparation. Weight management is another area where we can assist if that is contributing to their pain. Also, any other pacing or adaptive equipment techniques can make the eating meal prep experience a little more efficient and easier to tolerate.

Physical Activity

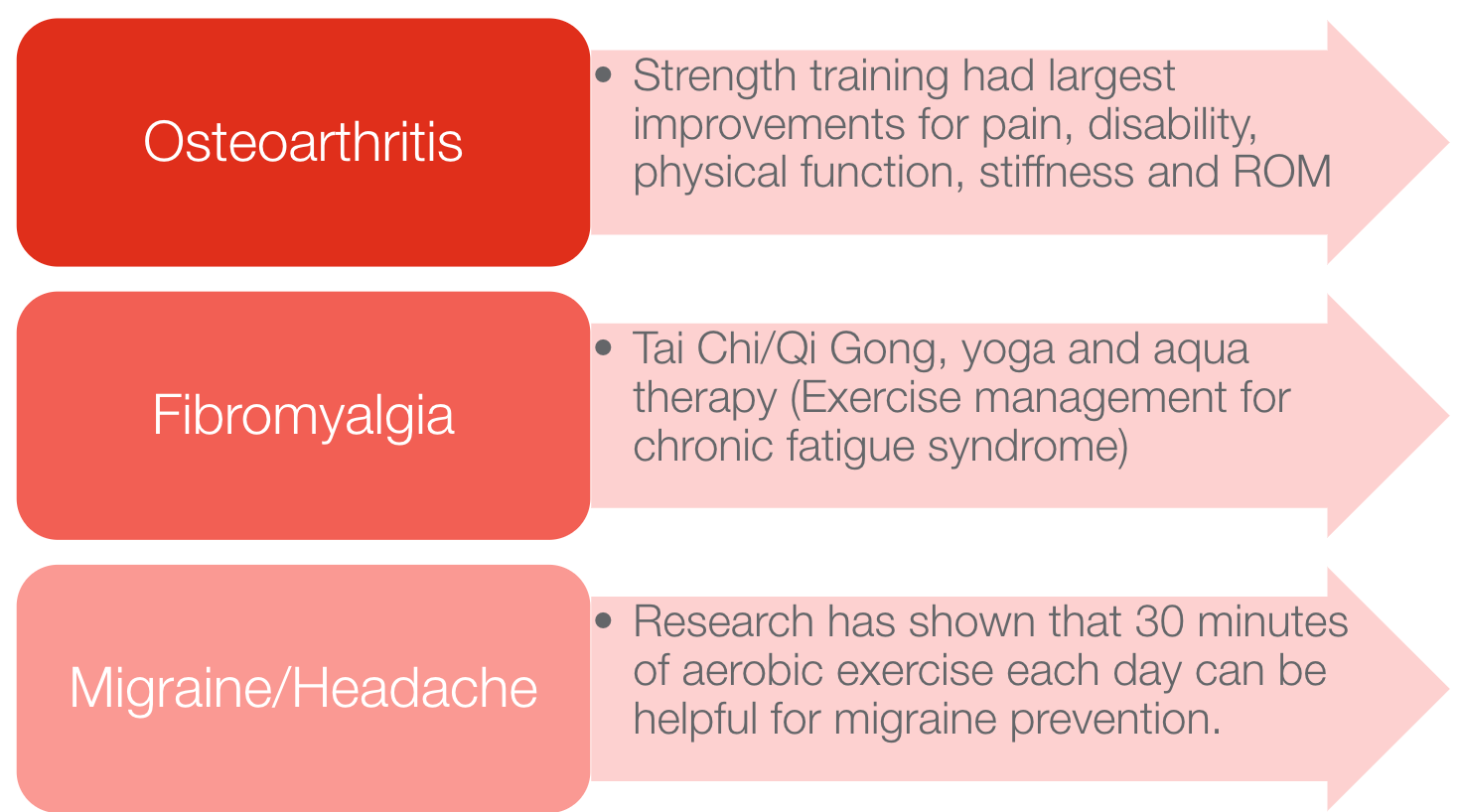

There are many physical activity recommendations out there in the literature. I just wanted to highlight a few of them (Figure 16).

Figure 16. Physical activity recommendations.

For osteoarthritis and pain specifically, strength training effectively improves pain, physical function, stiffness, and range of motion. They recommend more mind-body exercises like Tai Chi, Qi Gong, yoga, and aqua therapy for fibromyalgia. For migraine and headache pain, 30 minutes of aerobic exercise has been shown to prevent headache triggers each day. For whatever pain condition you are treating, I would recommend looking at the research and seeing what form of physical activity is recommended.

- Finding the just-right balance

- Choice of activity important

- Grade exercise without a pain flare

- Routine establishment

- Exercise pacing strategies to facilitate successful engagement:

- Stay hydrated

- Proper body mechanics

- Begin with short duration and low intensity, and increase very gradually.

- Avoid overheating with the use of a fan, cooling garments, or water-based exercises.

- Regular eating routine adherence

- Warm-up and cool-down routines

With that being said, I think another role that we play is helping patients find and establish safe and effective exercise routines that they prefer. Pacing strategies might be essential to help them gradually get back to exercise routines. They need to make sure that they are staying hydrated and warming up and cooling down properly. As a heart rate monitor, they might use symptom monitoring tools to increase their awareness of the relationship between their heart rate and their headache onset. There are many different ways that we can support physical activity.

Body Mechanics and Ergonomics

- Body mechanics

- Include sexual activity and safe positioning

- Bending, lifting, movement education

- Ergonomics

- Work

- Driving

- Integrate activity pacing principles

Body mechanics and ergonomic training can help to reduce joint strain and decrease repetitive movements. Again, give patients a tool to check-in to see how they are using their body during a task. This can prevent pain onset.

We also want to look at ergonomics, especially with people working from home and spending so much more time on the computer. Help clients to set up their workstations and computers in a way that is not promoting poor postures. We want a neutral spine, as shown in green (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Proper body mechanics.

We can also promote those activity pacing principles during the workday.

Adaptive Equipment Training

- To decrease joint strain

- Improve energy management

- Increase safety and independence

- Examples:

- Long-handled equipment

- Shower bench

- Rolling carts

- Driving aids

- Garden kneeler

- AND SO MUCH MORE!

Similarly, if we evaluate a specific task with the patient and they have a hard time completing it independently, we might explore adaptive equipment training. This can help to reduce joint strain, improve energy management, improve safety, and increase independence. A few examples are long-handled equipment, shower benches, grab bars, rolling carts, and garden kneelers. There are so many adaptive equipment options out there. Depending on the task, it is worth exploring these options to help patients perform that tasks with less pain, more energy, and more independence.

Meaningful Occupation

- Community integration/reintegration

- Leisure and avocation

- Socialization

- Pain flare-up planning

Another area is looking at occupational engagement and helping patients with community integration. If fear and avoidance behaviors are present, we want to help patients safely and effectively get back into those activities. This could be community, work, or school integration, leisure and avocation activities, socializing, and also pain flare-up planning.

- Work/School (Re)Integration

- Work/School accommodations

- Activity pacing plan to gradually return

- Body mechanic/ergonomic training

- Assertive communication/self-advocacy

- Morning/evening routines for pain management

- Problem-solving environmental barriers or sensory exposure risks

I do a lot of work with clients to help them identify reasonable and necessary accommodations that will support their ability to engage in work or school while managing their pain condition effectively. I often write accommodation letters that the physician co-signs. This has really helped patients get back to work, maybe after a leave of absence, or to tolerate work better because those support systems are in place.

Other work school re-integration strategies could be that pacing techniques and body mechanics. You can also do some assertive communication or self-advocacy training if a patient has difficulty communicating with coworkers or their HR department. This gives them the skills that allow them to communicate more effectively. We need to help people establish morning or evening routines that can help them manage their pain better. We also want to help them to problem-solving through any other potential environmental barriers or sensory exposure risks.

When reintegrating into an activity, I like to help patients think about the things they need to do before a potentially triggering event, during that potentially triggering event, and even afterward. Hopefully, by doing this, there is less disruption to their nervous system throughout the activity itself.

- Social/Leisure Engagement

- Exploring leisure and social interests

- Values checklist

- Modified interest checklist

- ID’ing community resources

- Support groups

- Psychological supports

- Problem-solving through potential barriers

- Risk for overexertion

- Transportation limitations

- Exploring leisure and social interests

With social and leisure engagement, and again getting back to those meaningful occupations that can provide a positive distraction and release those good endorphins, we might do several things with the patients, exploring their leisure and social interests. And these are some tools that can help with that. Identifying community resources, linking them to community support groups, or helping them find psychological supports in the community are other options. And then again, problem-solving through any barriers that might exist. So if they're at risk for overexertion, let's come up with a pacing plan, or if there are transportation limitations, maybe there are some resources for that too.

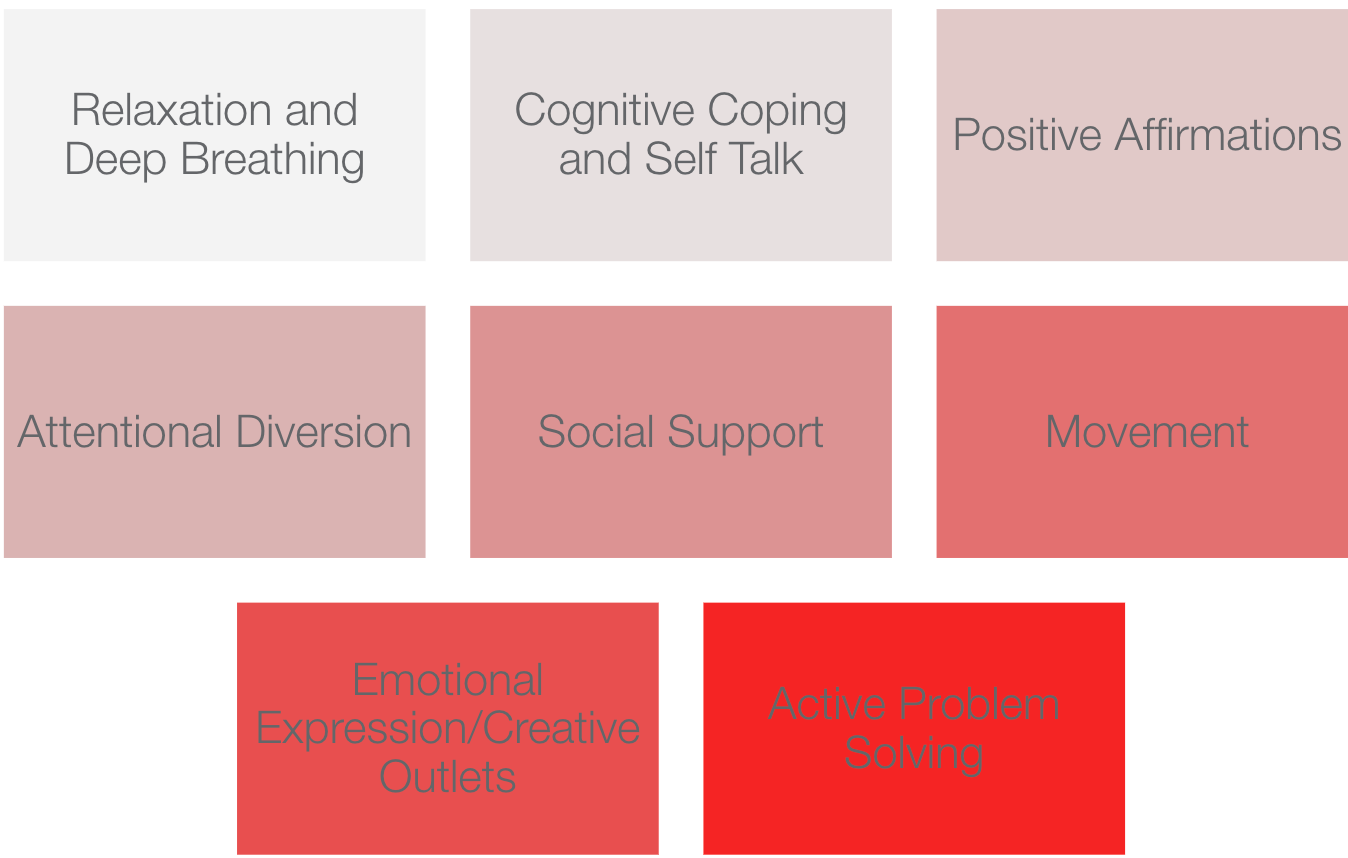

Lastly, more towards the end of my treatments, when patients have been trained in all of these self-management interventions and before discharge, I want to make sure they have a very specific pain flare-up plan in place.

- Creating a Pain Flare Up Plan

- The Flare Up Plan needs to be:

- Explicit

- Useful

- Achievable

- The Flare Up Plan should utilize

- Diverse Skills

- Various Coping Modalities

- The Flare Up Plan needs to be:

A flare-up plan is meant to be explicit, useful, and achievable and is a diverse set of coping strategies that the patient can use. The goal with this is to reduce the overall duration and intensity of their pain flare-up. Some of the pain flare-up plan strategies that we have already discussed. Hopefully, they feel like they have a lot of these tools under their belt. It is building their self-efficacy to say, "Oh, I have a lot of these strategies in my toolbox." You want them to feel confident in preparing for discharge.

Figure 18. Strategies for a flare-up plan.

You want them to be able to use these strategies to get back to their activities gradually. You also want them to think about how they can make a task a little more simple. This summarizes all of the things we have discussed as a lifestyle design approach using a biopsychosocial model.

Interdisciplinary Team Care for Pain Management

I did also want to spend a little bit of time focusing on interdisciplinary care for pain management. While the recommendation is to use a biopsychosocial model approach, this also goes hand in hand with using an interdisciplinary care team to address each of those factors.

Current Challenges in Healthcare

Here is some information from AOTA's forum on interprofessional care teams. This highlights some of the challenges that exist in healthcare and why interprofessional care is recommended.

- High cost of care

- Aging population and growth in chronic disease rates

- Inadequate access to care for many Americans

- Fragmented structure for delivering and paying for care

- Lack of coordination of care between settings

- Problems with the quality of care, including difficulty in managing chronic illnesses and providing reliable continuity of care

- Poor reimbursement, physician dissatisfaction, high workload, and workforce shortages in primary care

There is a high cost of healthcare as well as a growing aging population. There can be difficulty accessing care due to a lot of barriers. Healthcare can be fragmented. Research also shows that using an interprofessional care team can be more cost-effective. AOTA and several other healthcare professionals recognize the importance of interprofessional care teams.

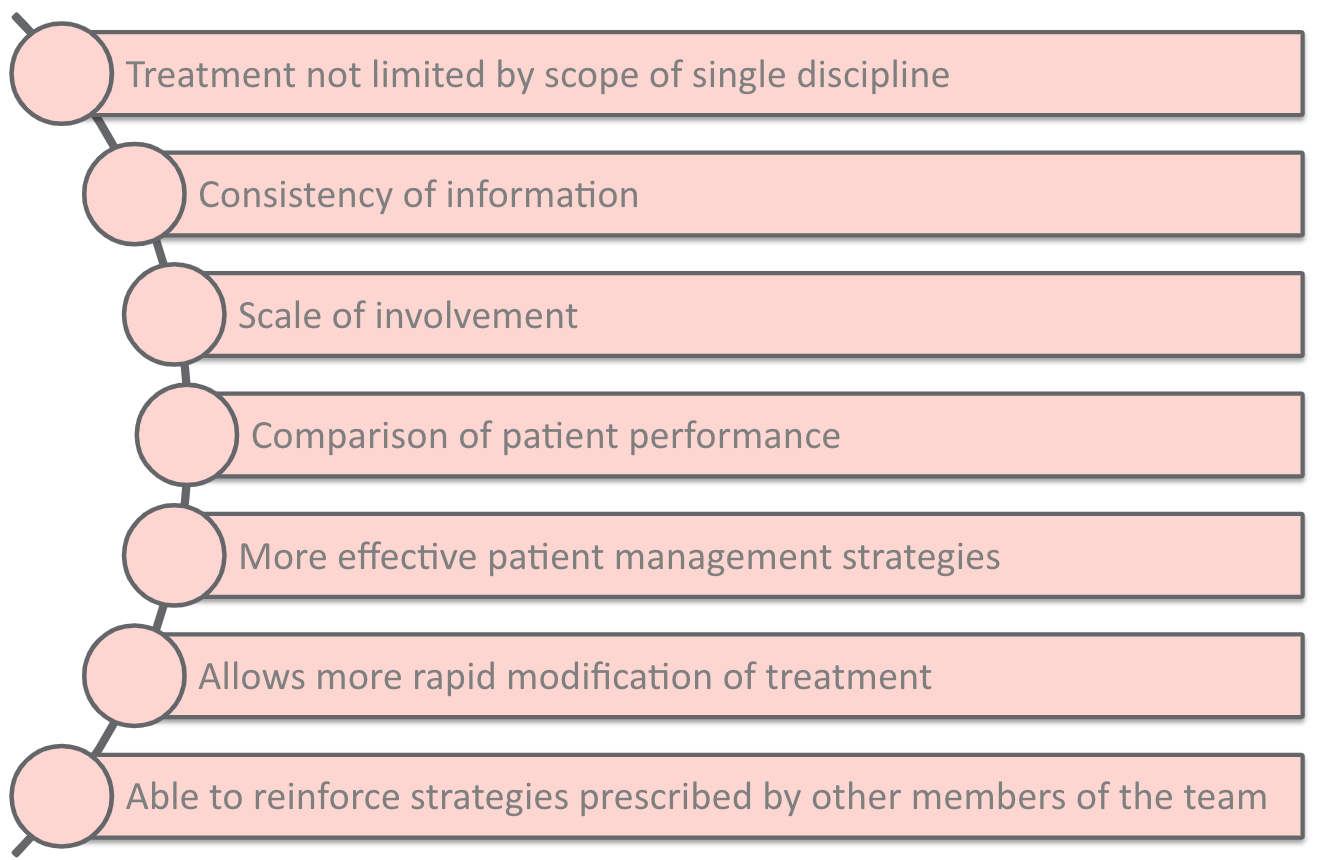

Advantages of an Interdisciplinary Team

For pain management specifically, research and my experience show advantages to a team approach (Figure 19).

Figure 19. Advantages to treating pain via a team approach.

First and foremost, pain treatment is not limited to any single discipline. A client will get intervention from various specialists that can address each of those biopsychosocial factors. With a team approach, there is also a more consistent release of information. If a patient is working with OT, PT, and psychology, we might all be reinforcing the same information and education, and that can improve treatment outcomes and reduce the duration of treatment. The patient will also be more involved in their care, demonstrating that they are engaged and ready to make some behavior changes.

Having a team approach can also help each discipline recognize risk factors sooner and communicate that to the team. More effective pain management strategies and rapid modification of treatment are also benefits. The ability to reinforce strategies that other physicians or other team members prescribe is also a huge benefit. I would say that a lot of my work on an interdisciplinary pain team is helping patients implement the recommended strategies from their other healthcare providers like their PT home exercise program or a thought journaling exercise from their psychologist. Recommendations can be made, but the implementation piece is what is hard. We have a unique role in OT of focusing on the behavior change factors that can help with these learning techniques' carryover.

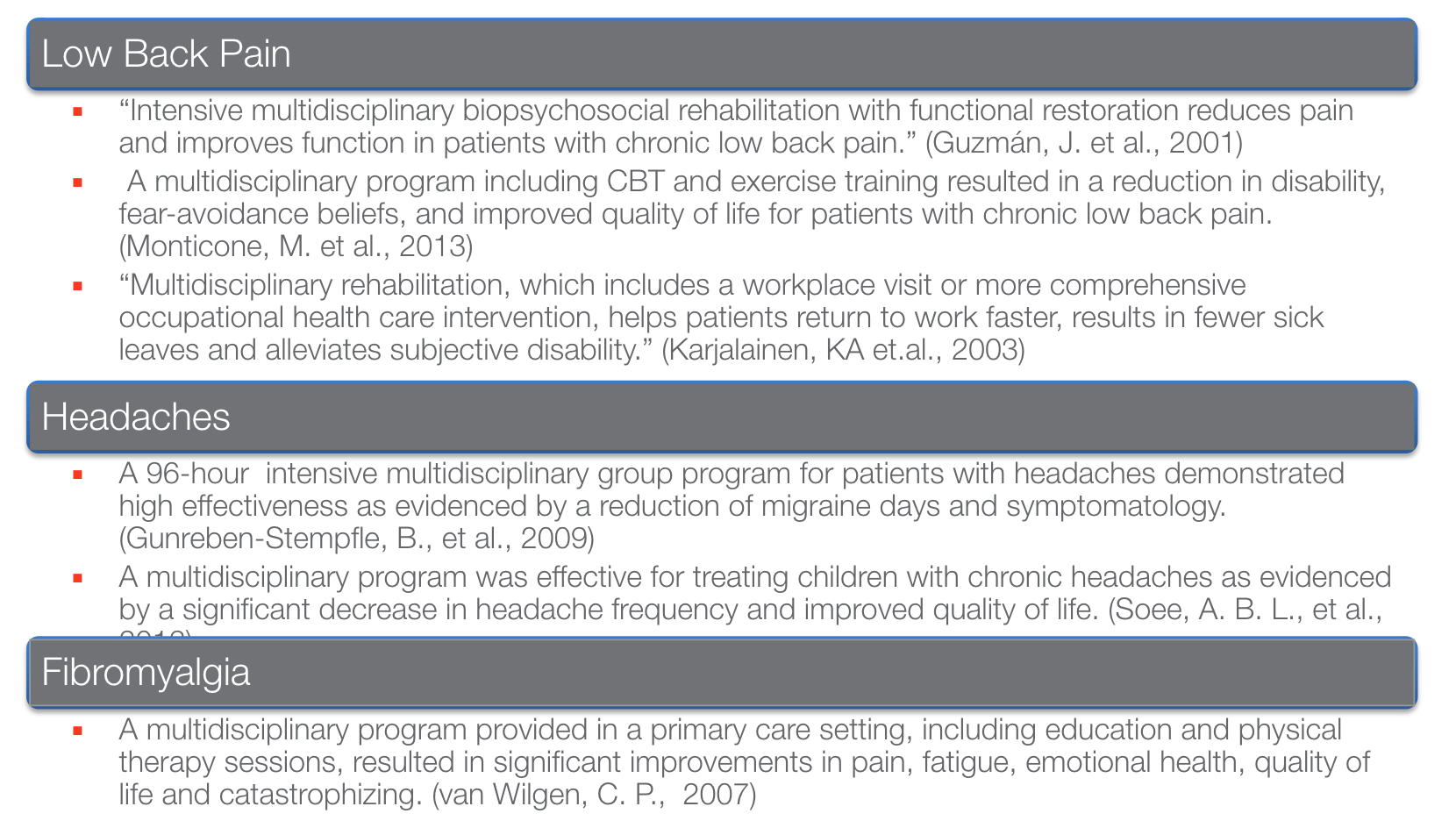

Team Care for Pain Conditions

I wanted to include some research and evidence for team care, specifically in Figure 20.

Figure 20. Evidence for a team approach for specific diagnoses.

There is so much evidence out there. For low back pain, team care was shown to reduce pain and improve function. It also helped patients return to work faster, which resulted in fewer sick days. It is reducing that overall disability. With headaches, a team approach demonstrated high effectiveness in reducing migraine days and the overall symptomatology. And with fibromyalgia, a team approach that involved patient education and physical therapy sessions led to improvements in pain, fatigue, emotional health, quality of life, and a reduction in catastrophizing.

USC Interdisciplinary Pain and Headache Teams

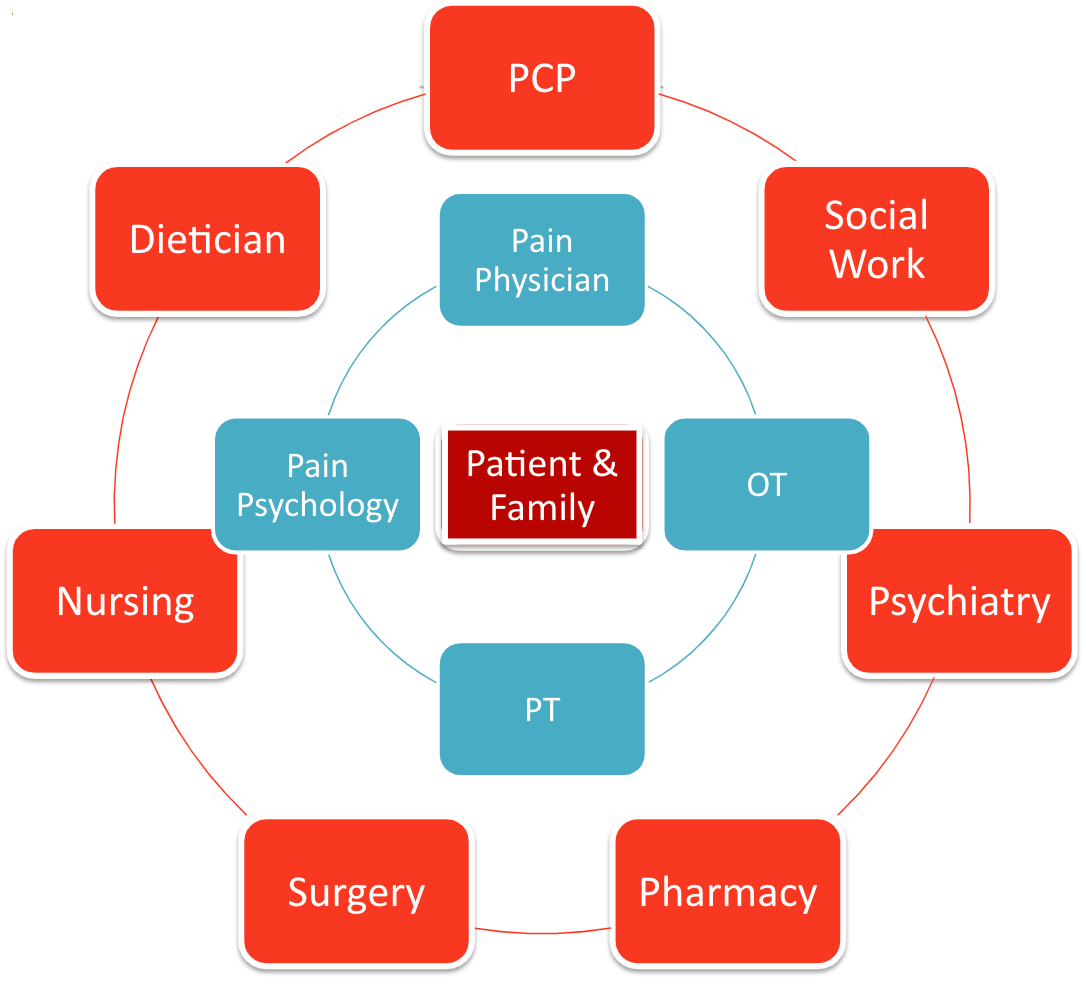

At USC, we have two great interdisciplinary teams, the pain team and the headache team (Figure 21).

Figure 21. USC pain and headache teams.

As seen in Figure 22, the patient is always the center of our care team.

Figure 22. USC pain team graphic.

Our core team members are the referring physician, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and pain psychology. And then, we will call in additional providers on an as-needed basis. One of the potential challenges with a team approach is the fear of practice overlap.

Our Strategies for Practice Overlap

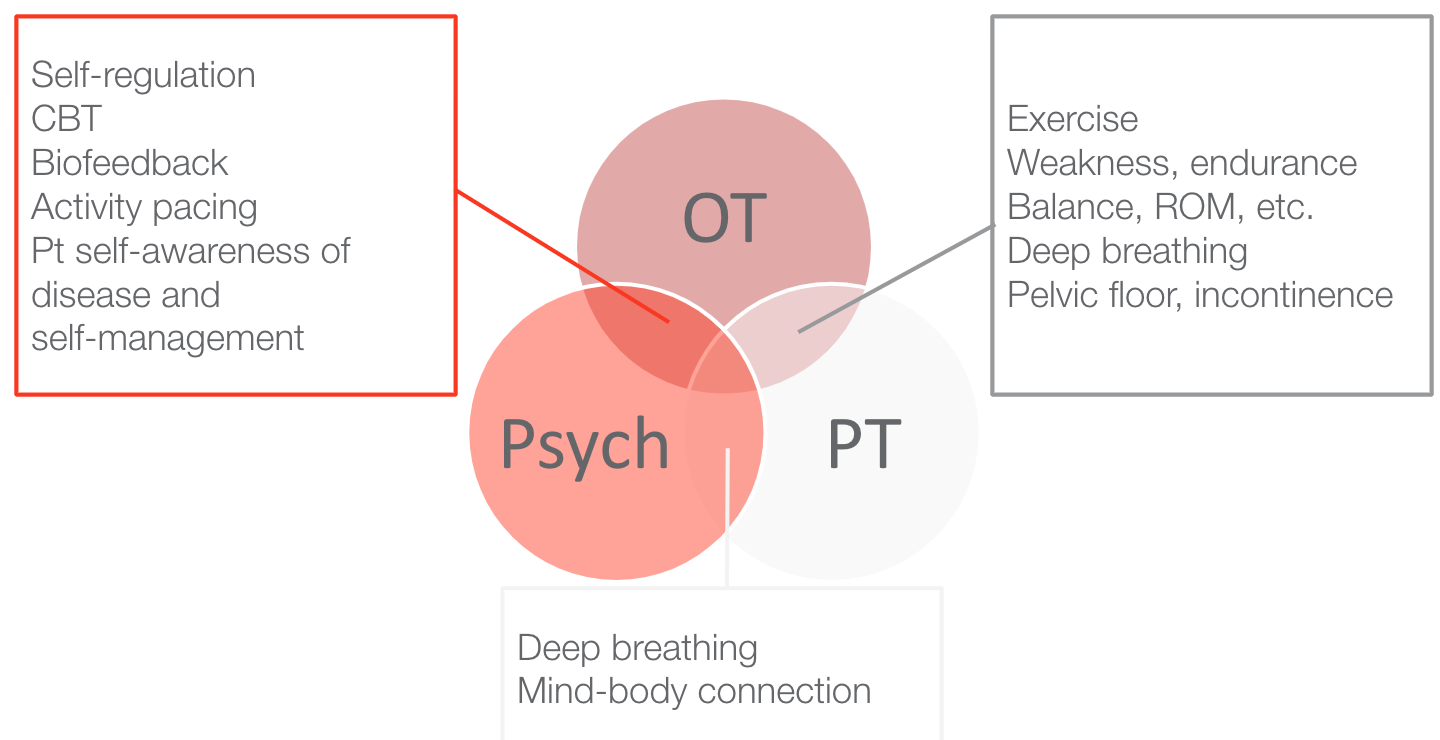

For our team specifically, we welcome that overlap because we feel it further reinforces the things that each discipline is doing. Listed in Figure 23 are examples of how psychology, PT, and OT disciplines might work together on stress management. Using our own frameworks, OT might focus a little more on integrating those stress management strategies into routines.

Figure 23. Examples of OT, PT, and Psychology disciplines working together.

Psychology and PT might both be working on deep breathing and the mind-body connection. OT and PT might be working on exercise and physical activity. Still, our focus might be a little more on the pacing with exercise or integrating exercise into a typical week or a daily routine.

Characteristics of a Well Functioning Team

One challenge with establishing team care is there is no handbook to follow on creating and developing an effective team. Still, there is a lot of literature and research out there about the characteristics of a well-functioning team, as noted in Figure 24.

Figure 24. Characteristics of an effective team.

The characteristics of an effective team are leadership and communication both within the team and with the patient. It is important to have training opportunities in place and the appropriate resources and procedures. It is also important to have a clear vision as a team. You need to measure the quality of patient care outcomes as well as how your team is functioning. And then, of course, all team members need to understand each other's roles and what each discipline contributes to the patient care experience. When we use that team approach, we can put all of these puzzle pieces together and address all of the different ways that pain might be affecting someone in their everyday experience. One of my favorite parts of working with this population is being able to collab