Lyndsay: I am currently working in a Surgical Trauma ICU, and Meghan comes from the Neurological ICU. We will each be giving our personal clinical input on this topic.

Overview

- What is Delirium?

- Clinical Relevance

- Assessing for Delirium

- Intervention Strategies

- Case Studies

What is Delirium?

- A disturbance in attention and awareness (ability to direct, focus, and sustain attention).

- A disturbance in cognition (memory, orientation, language, visuospatial ability, or perception).

- The disturbance develops over a short period of time (usually hours to days), represents a change from baseline, and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day.

- The disturbance is not better explained by another pre-existing, evolving, or established neurocognitive disorder.

The DSM-5 identifies it as a disturbance in attention and awareness, disturbance in cognition from a global perspective that is marked over a short period of time, an acute change within hours to days, and it really cannot be explained by another preexisting or evolving process. For instance, you might see somebody in a clinical setting who has an acute change in cognition, but then you later find out, they were having some sort of CVA process or hypoxic event. We obviously have a very focal and pointed medical reason why that change in cognition occurred so we would hesitate to consider that delirium.

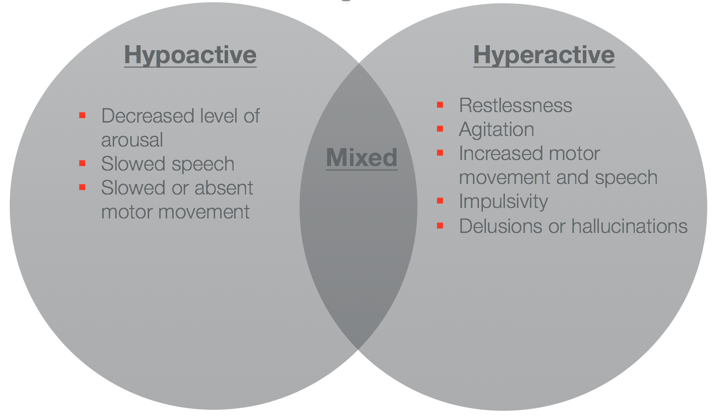

Delirium can present in numerous different ways. When I originally thought of somebody who was delirious, I pictured a hyperactive presentation with motor restlessness or agitation, pulling at lines, an inability to calm down, impulsivity, and hyperactive from a sensory standpoint, meaning auditory or visual hallucinations or delusions. Conversely, on the other end of the spectrum, you have the hypoactive delirious presentation. This is the individual that looks like they are sleeping, hard to arouse, slowed speech or maybe absence to speech, and slowed or absent motor movement. Finally, there is a subset of delirium that is mixed (Figure 1). On any given day, they can range throughout the spectrum of symptoms or presentation from that hypoactive to the hyperactive.

Figure 1. Delirium sub-types. (Yang et al., 2009)

Clinical Relevance

As OTs, why is delirium really that relevant to us? It is relevant because, in critical care, we see it quite a bit.

Prevalence

- ~35% of patients within the ICU experience delirium

- ~80% of patients requiring mechanical ventilation

Current literature (Clancy, Edington, Casarin, Vizcavchipi, 2015; Salluh et al., 2015; Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 2013) states about a little over a third of patients within the ICU will experience delirium at some point in their stay, and then of that subset of ICU patients, 80% of those who are experiencing mechanical ventilation will experience delirium. That is a pretty large majority of the patients that are potentially on our caseload.

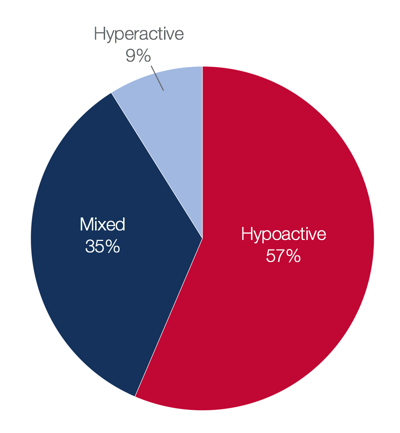

We also need to be aware of the signs and symptoms. Of the 35% of patients in the ICU with delirium, you will see the breakdown of symptoms in Figure 2.

Figure 2. ICU delirium symptoms.

The majority of them are going to be hypoactive. They are going to be difficult to arouse and really tired. This often goes underdiagnosed or there is a delay in diagnosis because the symptoms are less obvious as compared to our hyperactive patients who might be having pulling at lines or are agitated. This group is a smaller subset of the patient within the ICU.

Vulnerable Populations

- Advanced age (>65 years old)

- Post-surgical

- Pre-morbid depression

- Pre-existing cognitive impairment

- Ex.) CVA, TBI

- Poor eyesight or hearing

- Presence of infection or sepsis

The vulnerable populations include anybody greater than 65 years of age or who have had a preexisting cognitive impairment as they are considered to be a little bit less neuro-cognitively resilient. Also included on this list is anybody who has undergone surgery. If you think of the anesthesia process and a likely follow up with pretty powerful pain medications, these patients are less likely to be aroused and can slip into that delirious process. Anybody who has premorbid depression or decreased eyesight or hearing is more likely to become delirious due to a product of the environment.

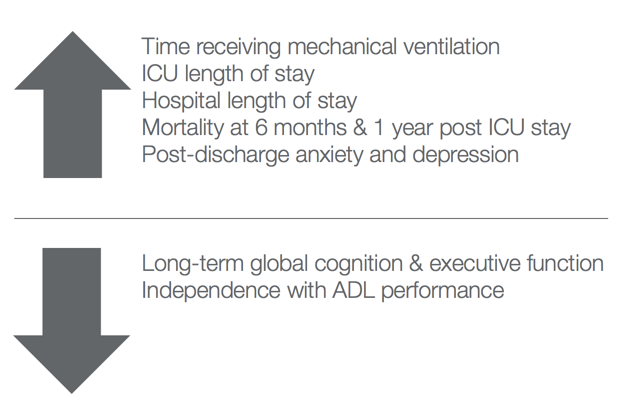

Delirium can lead to some pretty severe issues in terms of functional morbidity and then just poor outcomes (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Outcomes. (Salluh et al., 2015; Davydow, 2009)

Patients who currently experience delirium typically spend more time on mechanical ventilation, making them harder to wean, which then increases ICU length of stay. Patients can experience an overall increased length of stay within the hospital. They also have higher mortality rates. At six months and a year, one study showed that for every day a patient is delirious, they have a 10% increase in mortality rate, which is pretty profound. Then, patients experiencing delirium also have increased rates of anxiety and depression following discharge.

In terms of OT specifically, delirium has some pretty profound effects on a patient's function. They are less likely to return to independence from an ADL/IADL perspective. They are more likely to be dependent on caregivers for some aspect of their care, and they have poor long-term global cognition and executive function outcomes. They are less likely to return to work and leisure activities. There is a clinical presentation that is directly related to challenges in returning to functional independence. I think it is certainly an area that OT can provide some targeted intervention for.

Post-Intensive Care Syndrome

The Society of Critical Care Medicine states that we are seeing patients surviving these very profound critical care events, but they have new impairments in physical functioning, cognition, and mental health. They decided to term this syndrome, Post-Intensive Care Syndrome, as a way to identify this cluster of symptoms and as a way to provide very focused interventions to try to remediate this issue.

“New or worsening impairments in physical, cognitive, and/or mental health in ICU survivors.”

(Parker, Sricharoenchai, & Needham, 2013)

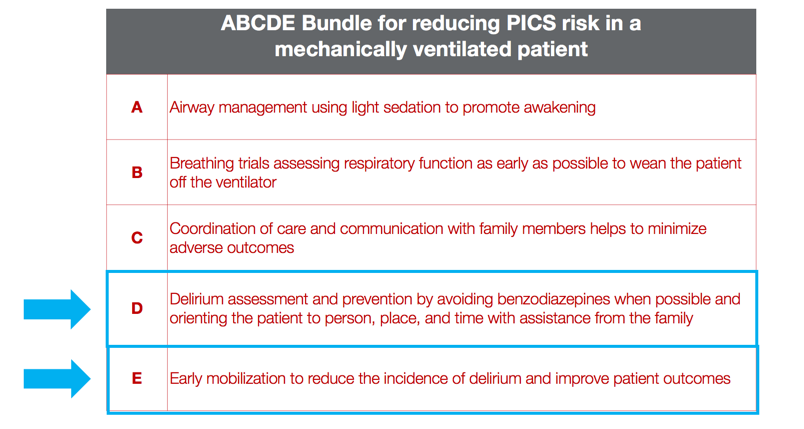

They came out with the ABCDE Bundle as a targeted way to help combat the effects of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome (Figure 4).

Figure 4. ABCDE Bundle. (Davidson, J. E., Harvey, M.A., & Bemis-Dougherty, A., et al., 2013)

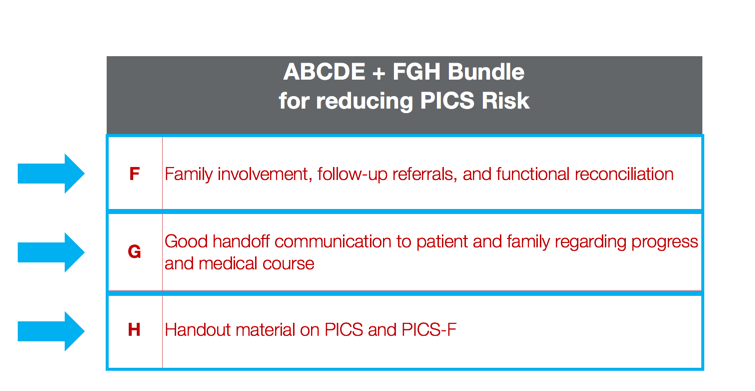

Of these, D and E directly relate to delirium management, as delirium carries a very high prevalence of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome following discharge. The experts in critical care management have decided to put forth these in order to improve outcomes, both of them targeting delirium. Several years later, they decided that managing the patient alone was not enough and that we really should be providing some targeted interventions to family, so they came out with the FGH bundle (Figure 5).

Figure 5. FGH Bundle. (Davidson, J. E., Harvey, M.A., & Bemis-Dougherty, A., et al., 2013)

This was developed to help remediate some of these issues that patients were experiencing and provide some family involvement along the way.

Assessing for Delirium

Meghan: We know the profound impact that delirium has on a patient's recovery and overall quality of life. I think we can all agree that there is a clear need for prevention as well as a need for effective treatment intervention. We learned what patients are most vulnerable and at a higher risk, now I am going to teach you what assessments and treatments that we OTs can use to not only screen but also treat all ICU patients for delirium. With practice, you too will be able to predict and prevent delirium in your setting. Here are some assessments.

- Confusion Assessment Method-ICU (CAM-ICU)

- CAM Severity (CAM-S)

- Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS)

- Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC)

- Orientation Log (O-Log)

Confusion Assessment Method-ICU (CAM-ICU)

First, I would like to start with the gold standard of delirium assessments. It was developed and validated for use by ICU nurses in 2001.

- Intended to assist with identifying the symptoms of confusion or delirium

- Administration time: 2-3 minutes

- Sensitivity rating: 95 to 100%

- Specificity: 93 to 98%

- *Most heavily researched

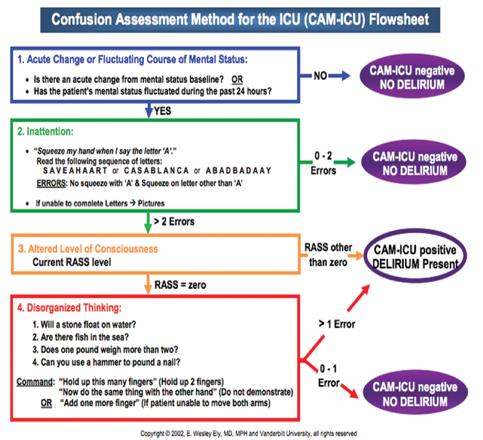

Patients are examined for their level of consciousness and cognitive functioning using a two-step approach. First, you take a look if there is an acute onset of mental status change or a fluctuating course, then you determine a patient's level of consciousness. I do think that this overall flow sheet, in Figure 6, can be a little intimidating, but I do highly recommend you check this out.

Figure 6. CAM-ICU Flowsheet.

There are also many examples on YouTube, and it is actually not that hard to implement into daily practice.

Another resource that I definitely want to encourage you to use is your nurses. Nurses typically do this assessment one to two times per shift. They are not only experts, but they are very willing to help you learn how to do this as well. At the end of the day, the more we know, the better we can help our patients.

The CAM takes two to three minutes to administer, and it has a sensitivity rating of 95 to 100% and a specificity rating of 93 to 98. It is also the most heavily research ICU assessment, and something that is pretty much communicated universally by all critical care providers.

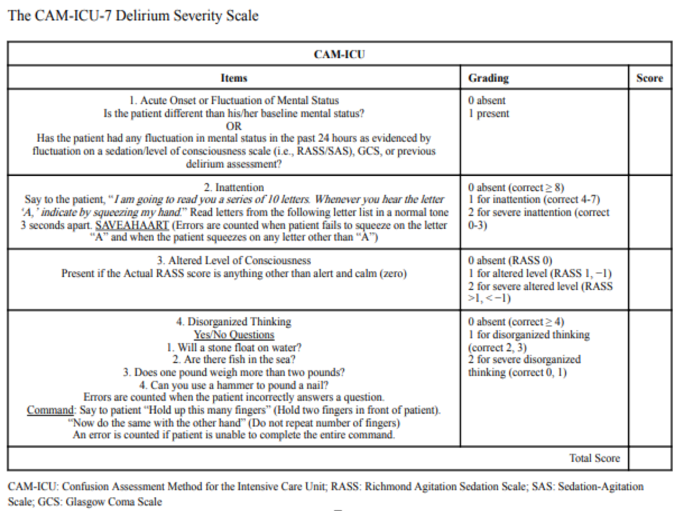

CAM Severity (CAM-S)

The second assessment is my personal favorite. It gives you the ability to quantify the intensity of the delirium that a patient may be experiencing.

- Assess the severity of delirium through observation of symptoms.

- Increased severity correlates to increased LOS, mortality, and nursing home residence.

Figure 7. CAM-S.

This addresses the acute onset or fluctuating course of delirium. However, it also is going to look at a patient's inattention or disorganized thinking in addition to their altered level of consciousness. This takes a little bit longer to do, but, when I say a little bit, I mean five to seven minutes. On the plus side, patients do not end their delirium when they leave the ICU. This is a measure that is also valid on floor patients, and I think is a really great way to communicate through different staff where the patient came from to where they need to be. The CAM Severity Scale is a great measure to illustrate a fluctuating course and any type of positive or negative trends. When I am assessing a patient, I do a CAM and then I do a CAM Severity. The power that the Cam Severity gives me a jumping off point of where they started, and then as you continue to treat your patient, you learn more about them. For example, if I go in to see a new patient and they have a CAM Severity score of one out of seven, I know that at this stage in their recovery, prevention or actual treatment management is going to be key. The more we can intervene on the front end, the greater the patient's chance at a good recovery and better quality of life is. On the flip side, if you see a patient continuously, and they continue to decline, you can then go to your neurosurgeon or whomever and voice your concerns. "Mr. Jones started off last week with a score of one out of seven on the CAM-S, and he's now a six out of seven. Can we reduce his amount of neuro-checks to allow him to have better sleep hygiene, or what can we do?" This man is not doing well. It just opens the door to have better clinical conversations with more objective data, so I am a huge proponent of this.

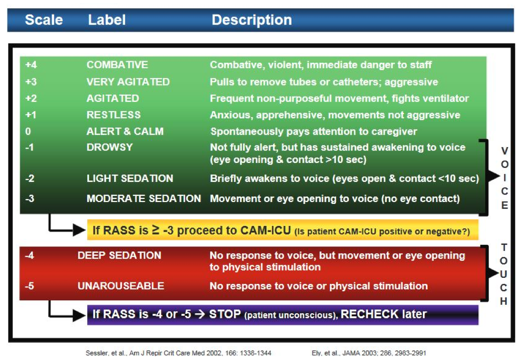

Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS)

- Medical scale used to measure the agitation or sedation level of a patient

- Integral part of the CAM-ICU assessment

- Assists with initiating spontaneous awakening trials with nursing staff

- Correlates to delirium type

- Hyperactive vs. hypoactive?

The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale is an additional measure used within the CAM but also can be used alone. This is another measure used to determine the level of consciousness of a patient. The original purpose of the RASS was to avoid over- and under-sedation. The RASS now, however, has also provided a very important therapeutic intervention guideline to clinicians to help assist in providing evidence-based treatment.

Figure 8. RASS. (Sessler, et al., 2002; Ely et al., 2003)

If the patient has a RASS of negative three, that is more moderate sedation. They can move and they open their eyes to a voice, but there is really no eye contact. I think many of us would agree that they are probably not engaged in what is going on. For this type of patient, they may benefit from a passive range of motion home exercise program and a music therapy program, which I will talk about a little bit later. This could be administered by a CNA or a patient's family member until they are able to emerge to the next level of consciousness where they would be much more appropriate for increased mobility and engagement of self-care tasks.

This scale can open up some pretty powerful clinical conversation with our teammates. We can initiate spontaneous awake trials. That is something I am going to go into on the intervention side. The more objective data we have reduces the amount of subjective input we put into patients' care, and we can really work within our interdisciplinary team to do what is best for each patient.

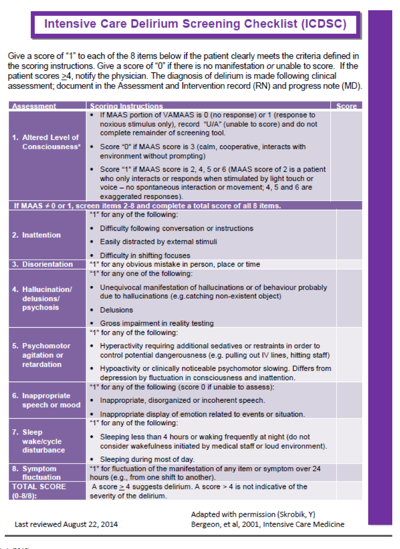

Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC)

- The current literature of delirium in the neuro population pertains to patients with mild to moderate illness severity.

- In the neuro‐critically ill, delirium screening is challenged by limited feasibility.

- Recent literature has demonstrated that the ICDSC may be a valid tool & the CAM-ICU is less suitable for delirium detection for patients in the Neuro- ICU.

For those of you who are working in the Neuro ICU or any kind of neuro environment, this information is hot off the presses. In an article by Larson (2018), researchers found that delirium was under-investigated in the neuro critically ill patient population. Now, of course, the harmful effects of delirium is well established. However, the ability to detect delirium in the acute brain injury patient population has not yet been validated. I would like to put in a little clarification at this time. The CAM-ICU does have mild brain traumatic injuries within their patient population, but for those who have much more moderate to severe deficits as well as more cognitive involvement, there has been no delirium measurement validated in this patient population. Larson's research group set out to validate and compare the CAM-ICU with this Intensive Care Delirium Screen Checklist (Figure 9).

Figure 9. ICDSC.

For those of you who are not familiar, the ICDSC is a checklist comprised of the assessment of eight different components as you can see here: Level of Consciousness, Attention, Disorientation, Hallucinations, Psychomotor and Agitation, Speech, Sleep-Wake Cycle, and then the Fluctuating of Symptoms. Without going into too much detail, when you score a patient with a one out of each eight items, the patient must clearly meet the criteria defined. This can also be found on YouTube. Anyone who scores equal or greater to four on this checklist makes them positive for delirium. We are not talking about how severe their delirium is so please note that when you are using this checklist for neurologically involved patients, if they get a four or more, that marks them as positive for delirium, but it does not speak to their severity. Using the severity scale in addition to this is much more helpful.