Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Optimizing Core Retraining, Part 1, presented by Jennifer Stone, PT, DPT, OCS, PHC, TPS, HLC.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze the anatomy and physiology of the core system.

- After this course, participants will be able to apply the relationship of the core system with the body and movement in order to support functional interventions for occupations and functional performance tasks.

- After this course, participants will be able to evaluate for appropriate motor control strategies of the core, including sources of impairment if they exist.

Introduction

Why are we talking about this topic? One reason is that suboptimal core strength and motor control strategy—something we’ll delve into more deeply when discussing motor control later—have been associated with various issues. These include low back pain, both acute and chronic, which, as we know, is one of the most common, if not the most common, reasons people seek outpatient therapy care. It’s also linked to hip pain, neck pain, and pelvic floor dysfunction. There is a strong association with an increased likelihood of athletic injuries, particularly ACL tears. However, with ACL tears, we must ask ourselves: is it especially prone to this issue, or is it simply what we’ve studied the most?

Core strength and motor control strategies are also strongly tied to the likelihood of falls in older adults. Falls are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in this population, making this a critical area to address. Additionally, suboptimal strategies increase the likelihood of developing chronic overuse injuries. Examples include patellar tendinopathy and lateral epicondylalgia—even tennis elbow connects to core strength and strategy. There's also a link to lateral ankle sprains that can occur with everyday movement. And this list goes on.

The short answer to why we’re talking about this today is that regardless of the setting or patient population you work with, optimizing core strength and strategy will likely play a key role. When discussing specific strategies and evaluations, this course will assume a relatively typical or non-impacted neurologic system. If you work with populations with neurologic impairments, adaptations can be made to apply these principles effectively, even though that won’t be our focus here. The concepts and patterns we discuss should still be broadly applicable, whether you’re treating children, adults, older adults, those with orthopedic injuries, balance and falls concerns, or even working in home health.

Anatomy & Physiology of "The Core"

As we look at anatomy and physiology, I apologize in advance if I’m causing anyone to have flashbacks to school during this portion of the class, but I think it’s important to explore what the current evidence says about how the core works. The term “core” is one that rehab professionals often use in a somewhat vague way. We talk about core strength, include core exercises in treatment plans, and reference it frequently, but sometimes we fail to define what we mean by “core.” Understanding how the core functions and how it can be optimized is crucial for both assessment and treatment, especially when dysfunctions are present.

What Is the Core?

What is the core? We say the word often, but do we truly know what it encompasses? For many people, the default thought is that the core refers to the abdominal muscles, and while these are indeed critical components, there’s much more to it. The abdomen, including the transverse abdominis, is extremely important, but the core involves many muscles working in concert. These include muscles in the trunk and torso, deep neck flexors, pelvic floor muscles, hip adductors, and the gluteus medius. It’s a 360-degree ring of musculature that works together as part of this system.

When evaluating and treating core dysfunction, we must address all these components. While we may not need to target every muscle for every patient purposefully, it’s vital to check the system as a whole to ensure it’s functioning optimally. Core strength is important, but it’s difficult to measure in isolation using traditional manual muscle testing because the core isn’t a singular muscle group. It’s also not comprised of muscles that pull in the same direction or operate in the same plane. When we talk about core strength, we often refer to strategy. The muscles need a baseline level of strength, but they’re not designed to be bulky, heavy movers. Instead, the core muscles are endurance-oriented, meant to provide a lower level of consistent activation over a long period.

The core also has an anticipatory function, which is critical for stability and movement. Studies show that core muscles fire before we reach to open a door or grab a coffee mug off a shelf—or at least they’re supposed to. This anticipatory control is key to optimizing core function, and while it’s valuable to train patients to activate their core consciously, we also need to ensure that anticipatory function is addressed. Without it, patients won’t carry over what they learn in therapy into their everyday lives.

We’ll also delve into physiology: how the core system works together, what it does functionally, and how it balances stability and mobility. Both concepts are essential to core control. We’ll also discuss alignment, another term frequently used by rehab professionals. Is alignment as important as we sometimes make it out to be? If so, when and how does it matter, especially given that no one maintains optimal alignment all day? These are some of the questions we’ll explore.

Muscles

Now, let’s talk muscles.

- Neck

- Deep neck flexors

- Trunk

- Rhomboids

- Lower/middle trapezius

- Transverse abdominus

- Multifidus

- Diaphragm

- Obliques

- Erector spinae

- Latissimus dorsi (and on…)

- Pelvis

- Pelvic floor

- Hip adductors

- Gluteus medius

As you can see, many muscles are engaged in the core system. These muscles encompass the trunk, neck, and pelvis, forming that 360-degree ring. While we don’t need to address each of these muscles for every patient, it’s important to consider all of them when assessing and optimizing core strategy.

Physiology

Anticipatory control plays a huge role here, as the core is involved in almost any movement. Even minimally challenging activities, like reaching for a coffee mug, engage the core. The system’s ability to titrate its response to different activities is critical. For example, the core should function differently when reaching for a coffee mug than lifting a 40-pound toddler or maxing out a deadlift. Patients with suboptimal strategies often lose this ability, resorting to an all-or-nothing pattern where the core is either minimally active or maximally engaged. Part of retraining involves reintroducing nuance and teaching patients how to scale their core activation appropriately.

When it comes to core dysfunction, we also need to consider endurance. Every muscle system includes both fast-twitch and slow-twitch fibers. Fast-twitch fibers are suited for short, powerful movements, while slow-twitch fibers sustain smaller, prolonged movements. Most of the core muscles are slow-twitch, designed for endurance. However, retraining the core may require addressing both types of fibers depending on the patient’s specific challenges. For instance, do they struggle with endurance tasks like cooking or folding laundry or face difficulty with powerful movements like lifting heavy objects? Understanding this distinction can guide our approach to treatment.

Many patients I’ve worked with, even those with significant core dysfunction, often have adequate isolated strength but lack the ability to coordinate their core system as a whole. This lack of coordination can lead to ineffective strategies for movement and support. During evaluation, it becomes clear whether the issue lies in strength or strategy based on how the patient moves and performs core-challenging activities.

Lastly, we must integrate core retraining into functional activities. The beauty of core motor control strategy is that it can be incorporated into any movement, exercise, or activity of daily living. Whether it’s unloading a dishwasher, running, or lifting weights, every task can become an opportunity to enhance core function when you understand the system and its role.

History of Core Stability

Let’s take a moment to talk about the history of core stability. Some of you may have been trained under instructors who were educated in very different eras of knowledge, passing along what was current at the time. It’s helpful to look at how our understanding of the core has evolved and how we, as rehab professionals, have thought about and approached the concept over time.

In the early days, the focus on the core was heavily centered around the rectus abdominis, or the "six-pack muscles." Back then, "core" and "rectus abdominis" were synonymous. Core strengthening at that time revolved around exercises like sit-ups and crunches, which directly targeted these muscles. That was the extent of our understanding.

Then, in the 1990s through the early 2000s, a movement scientist named Paul Hodges emerged with groundbreaking work introducing the idea of motor control theory. He brought attention to a lesser-known muscle, the transverse abdominis, which had been largely overlooked up to that point. Around the same time, the orthopedic world was developing clinical prediction rules (CPRs), including lumbar CPR, which featured a category called stabilization. Today, we often refer to this category as motor control or movement strategy, but it was simply labeled stabilization back then.

With these new research findings and clinical strategies, the rehab world started emphasizing abdominal hollowing and bracing techniques, particularly using the transverse abdominis. This period marked a shift in how many of us were taught. If you trained during this time, as I did, you likely learned to coach patients to find a neutral spine, perform a tuck-and-hold, and brace the transverse abdominis to stabilize the spine. The prevailing belief was that muscles attaching directly to the spine could stabilize it by physically holding it in place through isometric activation. If these muscles were strong enough, they were thought to provide adequate support for movement. Training at that time often involved teaching muscles to squeeze isometrically in various positions and under progressively heavier loads.

Our understanding has evolved further into the late 2000s and continues into today. I’ll pause to acknowledge that we still don’t have all the answers. As with most aspects of the human body, our understanding is constantly evolving, and I reserve the right to change my perspective if new research emerges in the next five years. Much of our current thinking still draws on the work of Paul Hodges and others like Diane Lee, who have expanded our knowledge of core strategy and function. Hodges noted that the rehab world ran much further with his early research than he ever intended, emphasizing that the story doesn’t begin and end with the transverse abdominis. He was clear that an exclusive focus on static hold strategies for motor activation is likely, not ideal, a conclusion that aligns with what we know about muscle physiology. After all, there are very few—if any—muscles in the body whose sole function is to squeeze and hold.

During this same period, Diane Lee introduced what was initially called the canister theory. This concept describes the core as a system of muscles that form a 360-degree structure around the ribcage, with the diaphragm as the top and the pelvic floor as the bottom. These components work together to achieve core control. Her theory shifted the focus to viewing the core as an integrated system rather than isolated muscles.

This evolution led to a divide in the rehab world. On one side were those who adhered to stabilization-focused approaches, emphasizing specific exercises for core recovery. On the other were those who dismissed specific core exercises altogether, arguing that the evidence didn’t support their efficacy. This group advocated focusing on overall movement and exercise as the primary approach for treating low back pain and other core-related dysfunctions.

As with many aspects of the human body, core physiology is complicated. We don’t yet have a complete or perfectly accurate understanding of it, but we must apply what we know to help our patients. As our knowledge grows, we refine our approaches and continue advancing our understanding of optimizing core function.

Current Core Physiology Theory

Current best evidence and theory suggest that we gain stability through mobility. This contrasts the earlier belief that stability was achieved by having muscles squeeze and hold. The current understanding is that the best way to achieve support—which I prefer calling support rather than stability—comes from movement and a mobile system. You’ll likely still hear me say stability at times because old habits, especially linguistic ones, are hard to break. However, the focus is on core, spine, and body support as functions of a dynamic and mobile system.

This mobile, multi-structure system creates a dynamic intra-abdominal pressure regulation system. I realize that’s a bit of a mouthful, but let me break it down. Rather than relying on muscles physically holding the spine still, this system uses intra-abdominal pressure to provide support. The fascinating part is that as long as the muscles are coordinated, they can maintain this pressure system, whether eccentrically elongating, concentrically contracting, or doing something in between. The system doesn’t rely on one static position.

Under this framework, alignment is far less important than we once believed. That doesn’t mean we completely dismiss alignment, and I’ll return to that shortly. Previously, we thought ideal stability could only be achieved in a neutral spine position, but current research doesn’t support that notion. A phrase I often hear is, "The best position is your next position." The human body isn’t designed to hold one position for extended periods. Instead, it’s built for movement and adaptation. Encouraging people to shift positions—whether at a workstation, during daily tasks like folding laundry, or at any other time—allows their muscles to function optimally by adapting to position changes.

This modern approach integrates motor control, anticipatory training, and dynamic control into a cohesive theory. Does that mean we discard the transverse abdominis (TA) and the idea of isolated isometric activations? I would argue no. While this remains a debated point, I believe those isolated activations are essential in reestablishing proprioceptive awareness. These exercises help patients reconnect their brains to specific muscles, such as the TA or pelvic floor, by making them aware of where these muscles are and how they should function. This foundational work is crucial for helping patients regain awareness and control of those muscles.

What about posture and alignment? I firmly believe that under very heavy loads—when someone is working close to their one-rep max or even at 80–85% of it—specific positioning becomes important. Certain alignments allow muscles to function at their peak under these conditions. However, this level of precision is only critical during maximum challenges. For example, we might emphasize specific alignment for an Olympic weightlifter during a competition but wouldn’t hold everyone to those same standards during everyday activities.

The takeaway isn’t to dismiss everything we previously believed. Instead, it’s about building upon prior knowledge, integrating it appropriately, and layering in new insights as we gain a deeper understanding of how the body functions. This evolving perspective allows us to provide better care and training strategies for our patients and clients.

Balloon? Canister? How Does It Work?

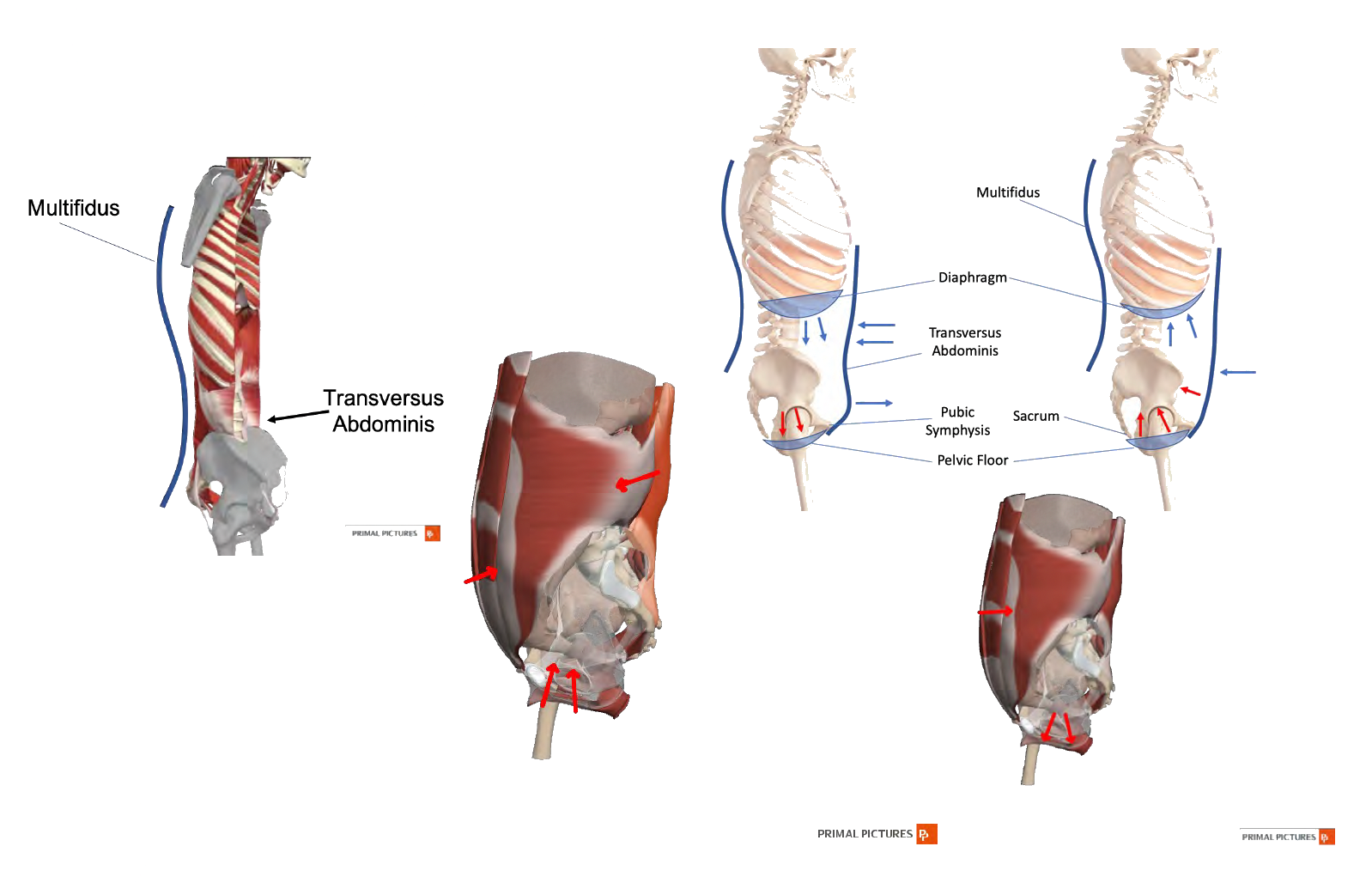

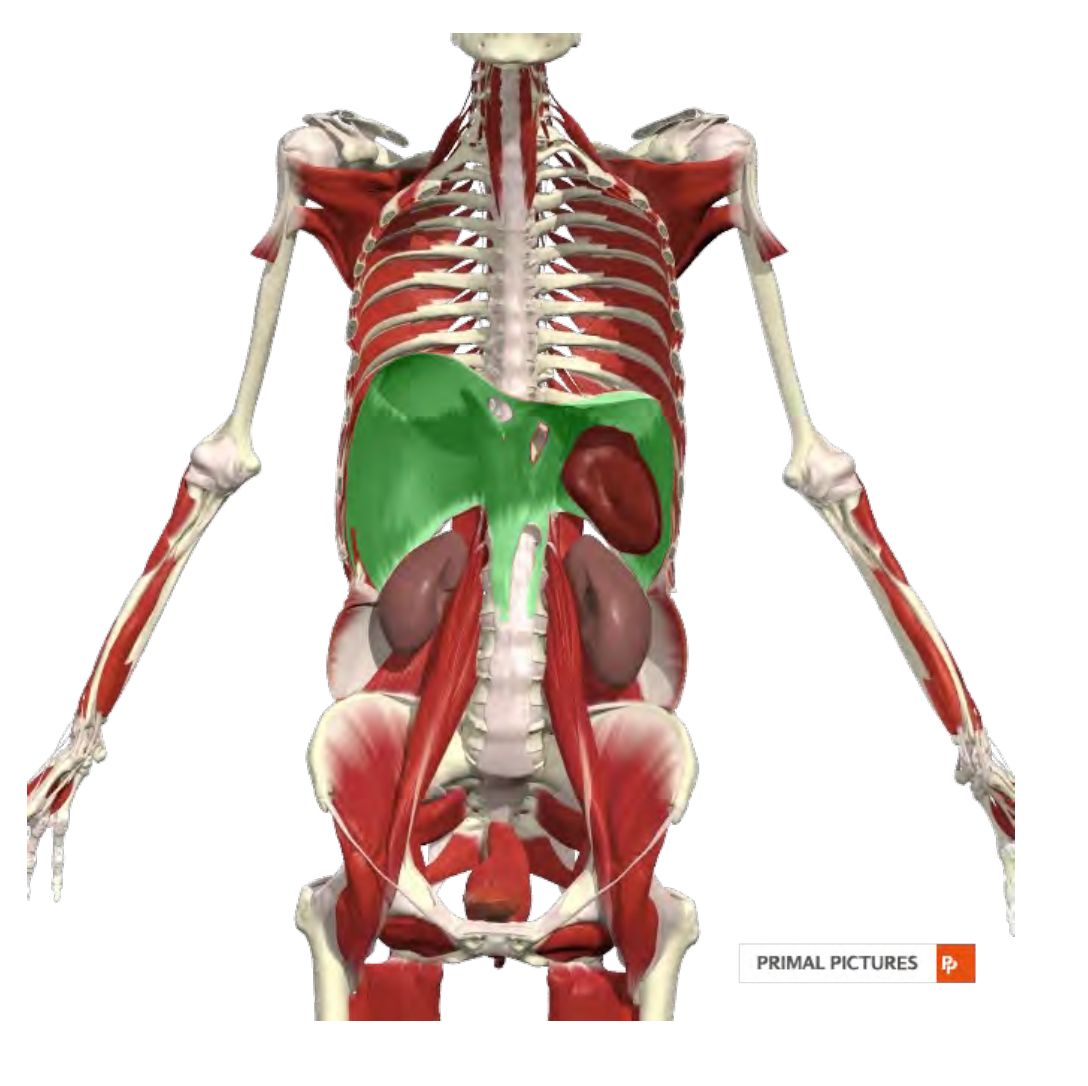

Let’s dive into what people mean when discussing balloons or canisters and how this works (Figure 1).

Figure 1. 360-degree system of muscles (Click here to enlarge this image.).

Essentially, we’re discussing a 360-degree system of muscles that wrap around the trunk or torso. These include the abdominal muscles, obliques, spine muscles, and so on. At the top of this system, we have the diaphragm, and at the bottom, we have the pelvic floor. Together, these structures create a pressure system within the abdomen.

This pressure system is not static—it’s meant to be mobile. I’m sure many of you have encountered patients who hold their breath during core-related exercises. It’s a common pattern, especially when their core strategy isn’t ideal. Holding their breath freezes the diaphragm, allowing them to generate pressure by squeezing and holding this canister. While this can increase intra-abdominal pressure, it’s not the most efficient or desirable strategy unless they work at their maximum capability, such as during a one-rep max lift. Ideally, the pressure system should increase and adjust proportionately to the task—slightly for reaching, more for moderate lifting, and much more for maximum effort.

We want to avoid breath-holding for most activities because we all need to breathe. If our patients aren’t breathing, their core strategy isn’t their biggest problem. The system must function even as the diaphragm moves, ensuring breathing and pressure generation work together seamlessly.

Here’s how it works: the muscles in the 360-degree system engage at a low level, maintaining both concentric and eccentric phases of activation. This activation supports the intra-abdominal pressure increase during both phases. The diaphragm and pelvic floor work in tandem—when the diaphragm drops during inhalation, the pelvic floor elongates eccentrically. This elongation doesn’t mean the pelvic floor “lets go” or loses control; it remains active to keep the pressure system intact. During exhalation, the diaphragm and pelvic floor rebound, maintaining the integrity of the pressure system.

This synchronized movement between the diaphragm, pelvic floor, and surrounding muscles allows for a dynamic, adaptable support system. It provides the stability and mobility needed for various activities while enabling the patient to breathe efficiently. This is how the core functions as a coordinated system rather than a collection of isolated parts.

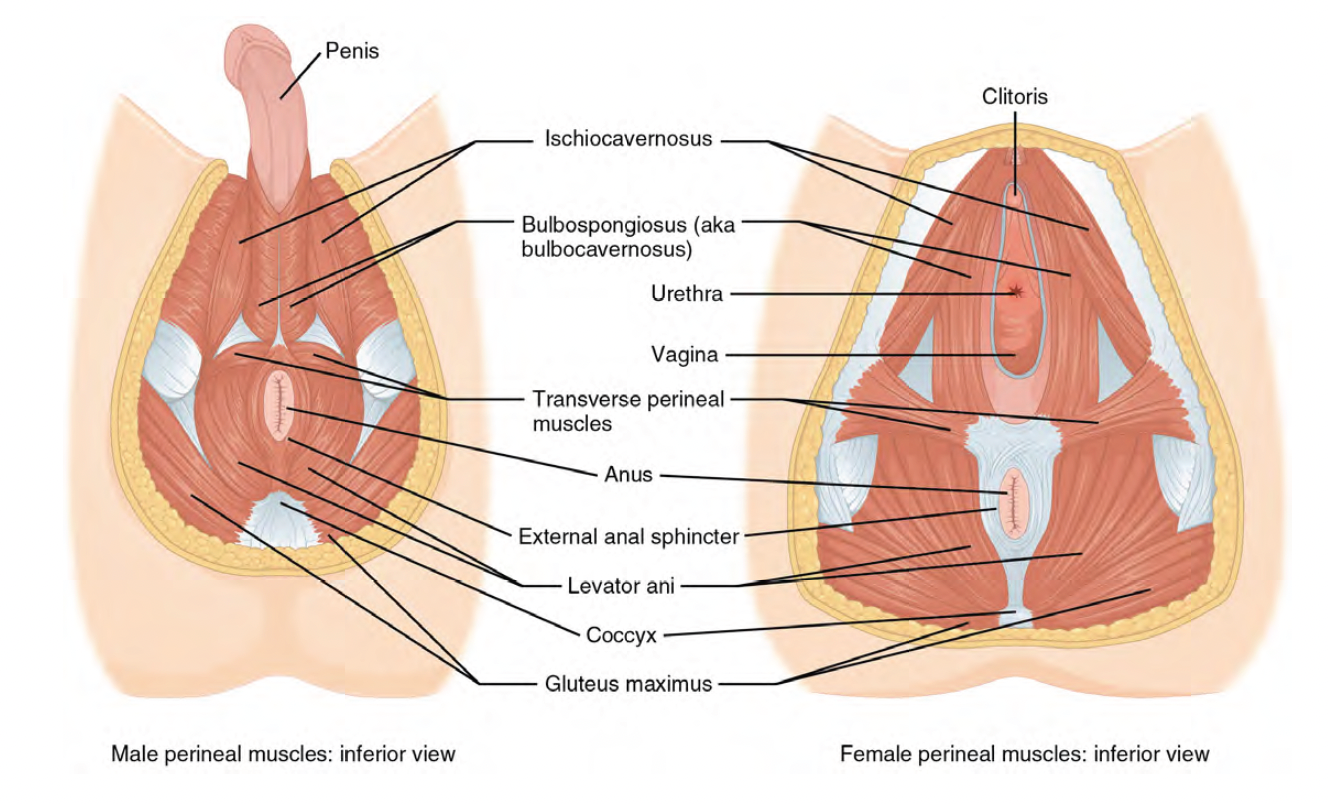

Pelvic Floor

Let’s talk about each of these muscle groups in terms of their contribution to core strategy and what they’re doing. Starting with the pelvic floor, there are three layers of musculature. For this discussion, we’re focusing on the deepest layer. This third layer is the one most significantly involved in core strategy, and it plays a key role in coordinating with the other core muscles, such as the diaphragm, transverse abdominis, and multifidus.

A particularly interesting study published in 2017 sheds light on the connection between the pelvic floor and chronic low back pain. This study examined individuals assigned to females at birth who were experiencing chronic low back pain but were not pregnant or postpartum, as those conditions introduce other influencing factors. Participants completed questionnaires and underwent assessments of their pelvic floor function. The findings were striking: 95.3% of participants showed at least one, and often two, signs of pelvic floor dysfunction, either subjectively or objectively.

This statistic is crucial for those working with patients assigned female at birth. It means you are treating patients with pelvic floor dysfunction, whether or not it has been explicitly identified. This is true across the lifespan, whether you’re working with young athletes, individuals who have never given birth, or postmenopausal patients. These findings make sense when we consider that the pelvic floor forms the "floor" of the core. It’s widely acknowledged that most patients with low back pain likely don’t have an ideal core strategy, and the pelvic floor’s role in core function is a significant factor in this.

A systematic review and meta-analysis (Kazemiia et al.) also provided further evidence of the pelvic floor's importance. They found that including pelvic floor muscle training exercises alongside standard treatments for low back pain significantly reduces the intensity of that pain compared to treatments that don’t address the pelvic floor. Patients in the pelvic floor-focused groups also experienced faster symptom relief, highlighting the value of integrating this component into care.

Here’s a visualization of the third layer of the pelvic floor in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Layers of the pelvic floor in male and female anatomy (Click here to enlarge the image.)

While I won’t delve into the specific names of the muscles—it’s not necessary for our purposes here—what’s important to note is that this layer consists of multiple muscles running in various directions. Together, they span the entire base of the pelvis, forming a complex and adaptable support structure integral to core function. Understanding this intricate network underscores why addressing the pelvic floor is essential when optimizing core strategy and treating related dysfunctions.

Patient Profile-Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Let’s keep this in mind as we discuss working with patients who are likely to have pelvic floor dysfunction. So, who are these patients? Essentially, anyone you see with suboptimal motor patterns could be a candidate, and we’ll discuss later how to identify those patterns. Patients with current or historical complaints involving their lower back, pelvic girdle—sometimes referred to as the SI joint, though I prefer the term pelvic girdle because it’s more inclusive—or hip pain are likely to have pelvic floor dysfunction. Similarly, a history of surgery in any of these areas, like abdominal surgeries, can increase the likelihood. Any muscle in the body will decrease its activity levels during healing, which is a natural and necessary process for recovery. However, these muscles don’t always turn back on automatically after surgery. Some people might recover muscle activity without issue, but most need intentional work to regain proper activation and function. This is one of the reasons our profession exists, especially in orthopedics.

Interestingly, it’s extremely rare—at least where I practice—for patients to receive therapy referrals after abdominal surgeries. I don’t know if this varies regionally, but it’s always struck me as odd. If someone has a knee scope, which involves a relatively small amount of soft tissue disruption, it’s assumed that they’ll need therapy afterward. Yet, after a major open abdominal surgery, therapy isn’t even mentioned, and you might get strange looks if you suggest it. Despite this lack of referrals, such surgeries can significantly impact the canister system, and these issues don’t always resolve on their own.

Another group to consider is individuals with a history of difficult vaginal births or cesarean births. Both experiences can have long-term effects on the pelvic floor and, consequently, the core. Athletes, especially those in high-impact sports, are also at risk. Interestingly, research shows no measurable difference in pelvic floor dysfunction between athletes who have had children and those who haven’t—even in teenage athletes. So, it’s not safe to assume that being young and childless guarantees a fully functional pelvic floor.

Additional groups include postmenopausal individuals, postpartum individuals, those assigned male at birth, and patients with a history of cancer treated with chemotherapy or radiation. The list truly goes on. Essentially, most patients walking into your clinic could at least fit the profile for potential pelvic floor dysfunction. This reinforces the importance of considering these factors in your assessments and treatment plans.

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction May Sound Like...

Let’s explore some things patients might say that could indicate their pelvic floor strongly contributes to their symptoms. It’s important to note that it doesn’t necessarily mean their pelvic floor is fine if they don't mention these specific issues—it might not be a primary driver of their symptoms. Potential signs are if a patient says they experience more symptoms during their menstrual cycle, pain or discomfort with intimacy, trouble with constipation or initiating urination, or feelings of pressure or heaviness low in their pelvis. Some might even describe a sensation like things are “falling out,” though this is typically just a sensation of significant pressure in the area.

Other clues include tailbone pain, recurring SI joint problems, or comments like, “My SI joint keeps going out.” This one often catches my attention because the pelvic floor muscles attach to the pelvis and, specifically, to the anterior sacrum and ilium. Overactivity or an activity mismatch between the two sides of the pelvic floor can alter how pressure is distributed through the SI joints. While this might not cause immediate issues, it can lead to chronic symptoms over time. For patients with longstanding SI joint complaints that improve temporarily with therapy but return when therapy stops, this pattern often suggests pelvic floor involvement.

Earlier in my career, I used to attribute these cases to patients simply not following through with their exercises, which I now see as a short-sighted perspective. If we help patients optimize their movement strategies, they shouldn’t rely on specific exercises to maintain their progress. While staying active and moving is always good, no magic combination of exercises will permanently solve the problem if the underlying strategy isn’t addressed.

Additional signs to watch for include leakage of urine or stool, abdominal pain or cramping that has been ruled out as related to other conditions, and low back pain that improves with therapy but returns afterward. These are all strong indicators that the pelvic floor may be playing a role.

Finally, for patients with low back pain that worsens during their menstrual cycle, regardless of their age, this pattern strongly suggests a pelvic floor component. The pelvic floor likely contributes to the symptoms even if the pain is localized in the lower back rather than the pelvic region. This is an area where targeted intervention can make a significant difference.

Pelvic Girdle Supporters

Let’s start by discussing the pelvic girdle support muscles, including the piriformis, gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, hip flexors, and hip adductors. These muscles often become overactive as a way to compensate for an underactive pelvic floor. For example, patients with piriformis syndrome—while the condition itself is real—may actually have underlying pelvic floor dysfunction driving the problem. Many of us have seen patients who seem to move like “tin soldiers,” squeezing their glute muscles and relying on excessive extension during movement. These motor patterns are compensatory strategies for core muscles not functioning optimally. While these muscles are not typically classified as core muscles, they are heavily impacted by core dysfunction.

Here’s an interesting insight: the hip adductors often mirror the activity of the pelvic floor. If you’re not trained to palpate the pelvic floor itself but notice overactivity or tightness in the hip adductors, it’s a strong indication that the pelvic floor on the same side is overactive. Similarly, if one side of the hip adductors feels overly tight and the other side doesn’t, it’s a safe assumption that the pelvic floor is similarly imbalanced.

Patient Profile-Pelvic Girdle Support Dysfunction

Patients likely to have dysfunction in the pelvic girdle support muscles include those with a history of hip pain, hip surgery, chronic low back pain, or pelvic girdle pain (particularly posterior pelvic girdle pain). Other risk factors include recent significant weight changes (either gain or loss), abdominal surgeries, or even injuries to the limbs—such as an ankle sprain or knee surgery—that caused prolonged limping or reliance on crutches or scooters. These disruptions in movement patterns can lead to pelvic girdle dysfunction and, eventually, core dysfunction. It’s worth integrating exercises for these regions when rehabilitating patients with such histories to prevent long-term issues.

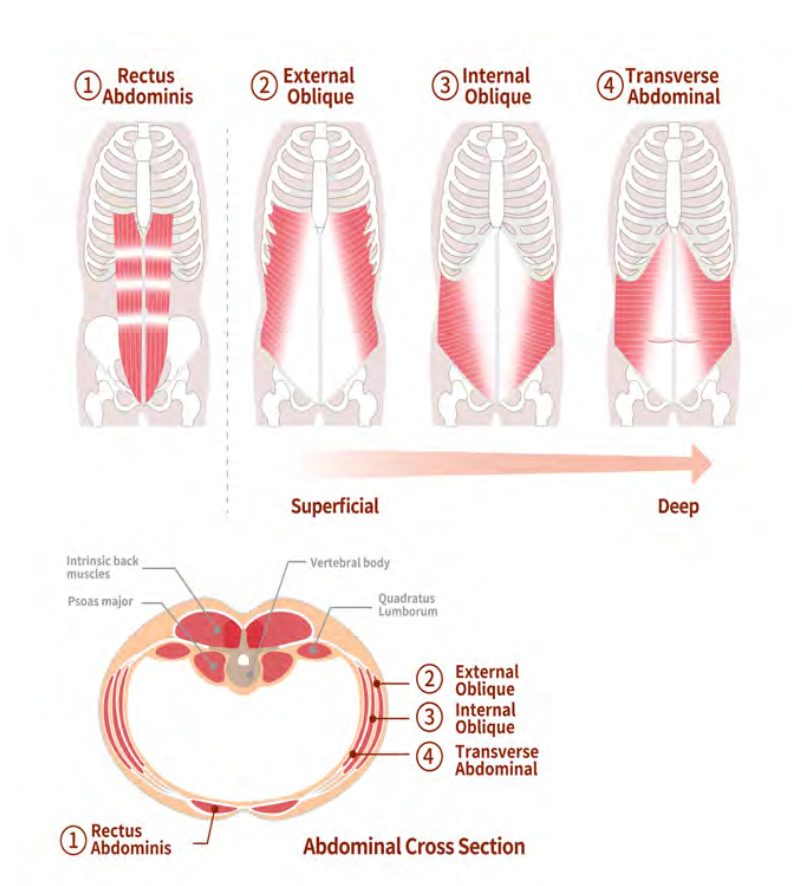

Anterior Trunk Musculature-Lower

Now, let’s talk about the anterior trunk musculature in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Anterior lower musculature (Click here to enlarge this image.).

The transverse abdominis (TA) is the deepest of these muscles and acts like a marathon runner—it provides steady, low-level contractions to stabilize the core. Its extensive attachments include the pelvis, spine, ribcage, and itself at the midline, creating a corset-like effect around the trunk. On the other hand, the obliques are primarily heavy movers, playing key roles in rotation and lifting tasks. Finally, depending on the activity, the rectus abdominis functions as both a heavy mover and a marathon runner. It is more active during heavy lifting than during endurance-based tasks.

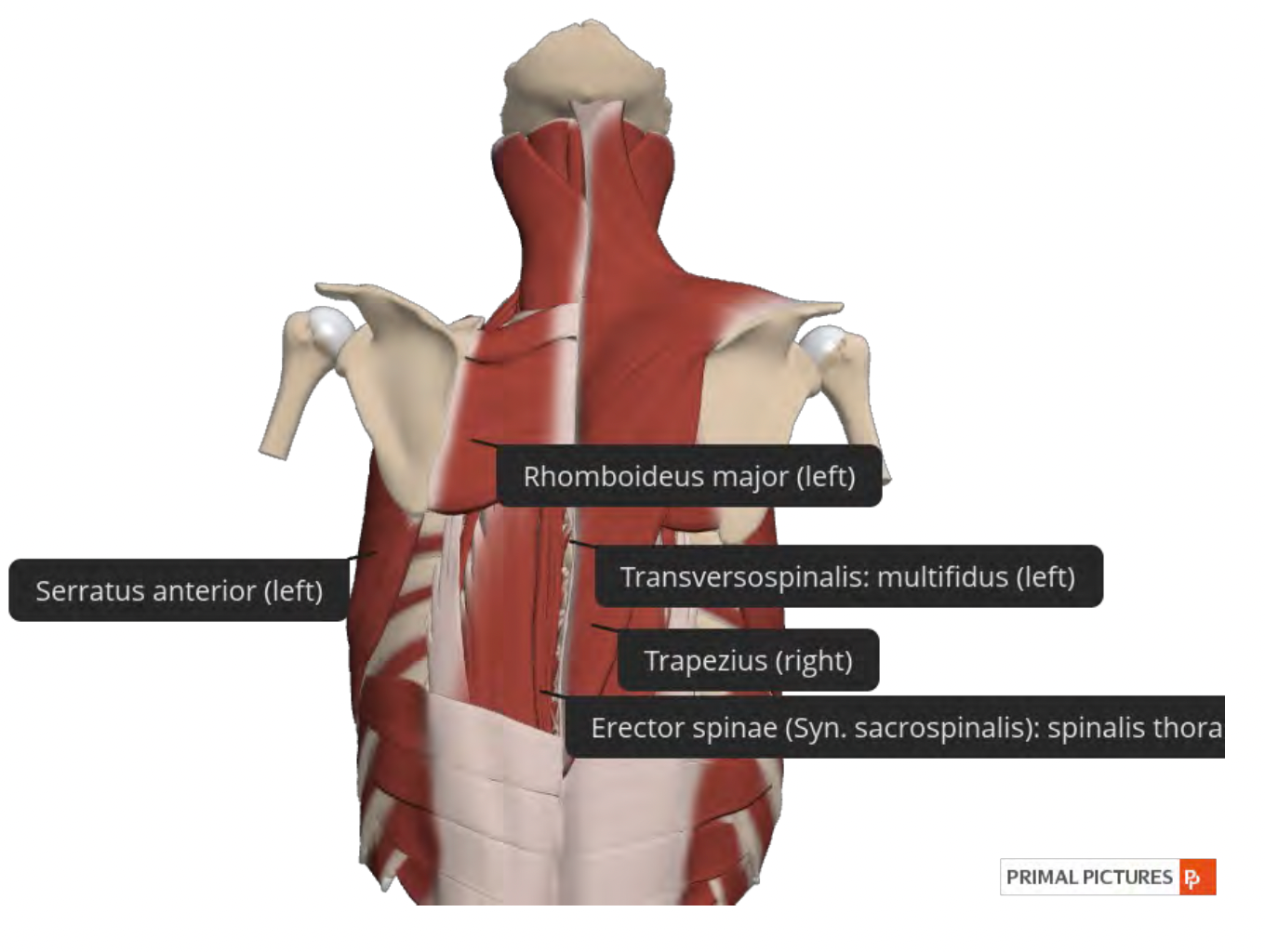

Posterior Trunk Musculature- Lower

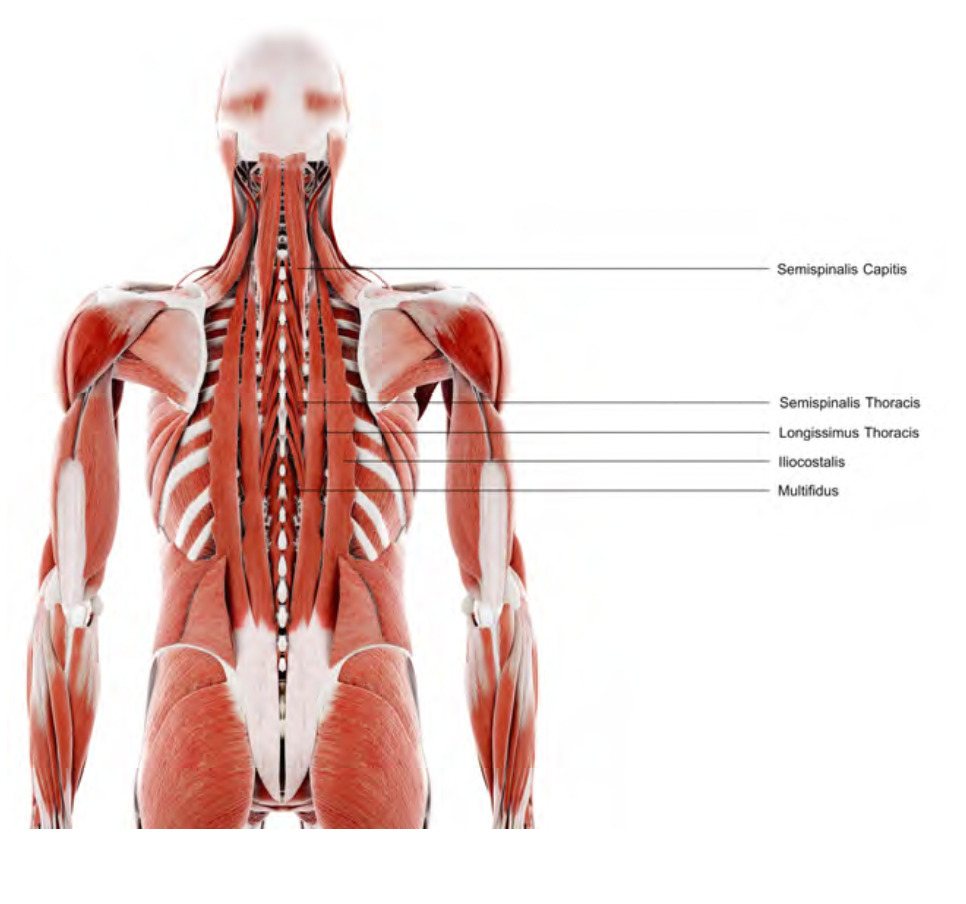

Figure 4 shows the back musculature, including the multifidus, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, and latissimus dorsi.

Figure 4. Posterior lower trunk musculature (Click here to enlarge this image.).

Muscles along the spine often become overactive or spasm to compensate for weak core muscles. In these patients, palpating along the spine feels like running your hands over steel cables. This overactivity is a clear sign of compensatory patterns.

Anterior Trunk- Upper

Here are the upper trunk muscles, particularly the serratus anterior and the diaphragm (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Anterior upper trunk musculature.

The diaphragm is crucial in regulating intra-abdominal pressure while maintaining oxygen exchange. It sits in a dome-like shape at rest and contracts downward to create a negative pressure system in the chest, pulling air into the lungs. The diaphragm relies on good ribcage and thoracic spine mobility and a breathing strategy that prioritizes its use to function effectively. Unfortunately, many patients—especially those with chronic respiratory issues or core dysfunction—default to breathing patterns that rely on accessory muscles in the chest and neck. Addressing these patterns is essential for optimizing both core function and respiratory efficiency.

Understanding these muscle groups and their roles highlights the core's interconnected nature and how dysfunction in one area can cascade into compensatory patterns elsewhere in the body. We can help patients achieve better long-term outcomes by addressing these systems comprehensively.

If you suspect your patient has core dysfunction, it’s crucial to assess their entire body—at the very least, everything from the shoulders to the knees. All of these regions can influence how the core functions, and neglecting to address them may limit your ability to help the patient achieve optimal outcomes.

Patient Profile- Trunk Dysfunction

Patients likely to have dysfunction in this 360-degree "trunk system" include those with a history of abdominal surgery, low back pain, hip pain, or hip surgery. These issues often create a reactive response in the core system as the body compensates for decreased function in the pelvic floor or hip stabilizer muscles. I frequently see this dysfunction in runners who don’t incorporate resistance training into their routines, particularly as they get older. While younger runners might get away with such imbalances, the effects become more pronounced in middle age, often surfacing in their 40s and 50s.

A history of non-contact ACL injuries is another significant risk factor. The association here is so strong that many researchers propose core dysfunction as a primary cause of these injuries. Without adequate support from the trunk muscles, individuals tend to rely excessively on heavy mover muscles, which can predispose them to these types of injuries over time.

Let’s not forget about the upper trunk and cervical regions. While our focus today is mostly on the lower trunk, it’s important to acknowledge that patients with neck pain, headaches, or thoracic dysfunction may also have involvement in these upper areas.

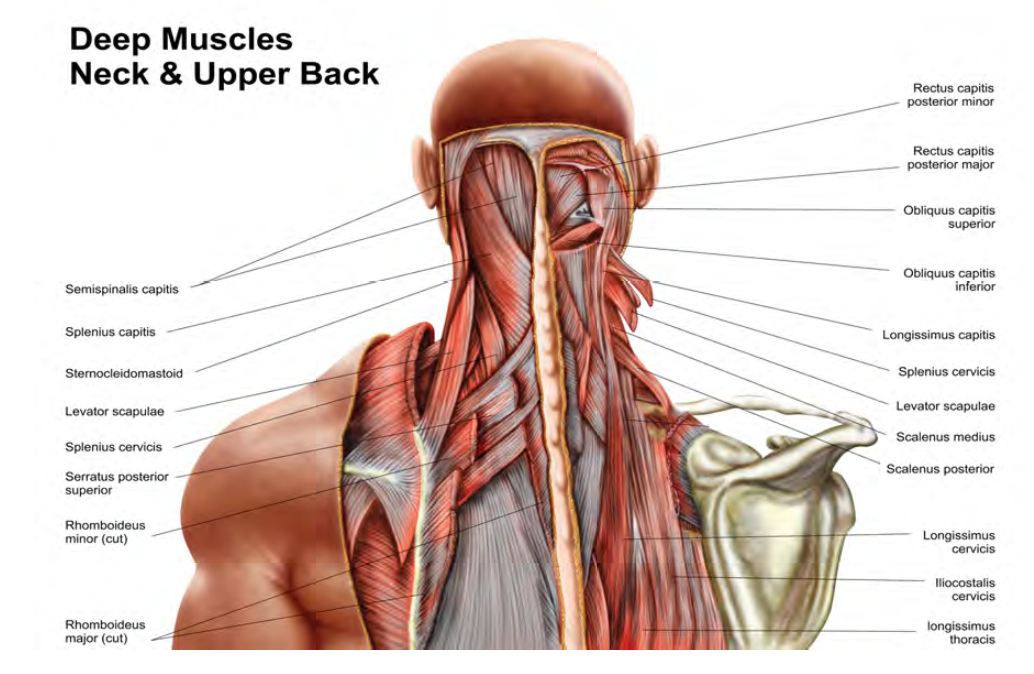

Posterior Upper Trunk/Cervical Musculature

- Posterior Upper Trunk

- Lower Trapezius

- Middle Trapezius

- Rhomboids

- Multifidus

- Erector Spinae

- Serratus Anterior

- Cervical Musculature

- Deep neck flexors

- Suboccipitals

Figures 6 and 7 show this musculature.

Figure 6. Posterior upper trunk musculature (Click here to enlarge the image.).

Figure 7. Cervical musculature (Click here to enlarge the image.)

Scapular stabilizers, deep neck flexors, and suboccipital and posterior muscles running from the lower to the upper trunk can all play a role.

Patient Profile-Upper Trunk & Cervical Dysfunction

Patient profiles for these issues often include a history of neck pain, shoulder or thoracic surgery, whiplash-related injuries (even if mild or untreated at the time), or rib dysfunction. We now understand that untreated injuries can lead to fatty deposits in muscles, potentially contributing to dysfunction later in life.

Summary

In summary, the core is not a single muscle or a singular muscle category. It’s a complex, dynamic system requiring collaboration and coordination among many moving parts to provide optimal support and function. While you may begin by focusing on a specific area, such as the pelvic floor or anterior trunk, achieving long-term optimization necessitates incorporating a broader, whole-body coordination strategy. This ensures the various components of the core work together harmoniously to meet the demands of your patient’s daily life and physical activities.

Evaluation Techniques

Now that we’ve talked about anatomy and physiology, let’s dive into evaluation techniques. I have a patient that fits one of these many profiles that I am now aware could have some version of core dysfunction. How do I know? How do I know which component? We just went through basically the majority of the muscles in the axial skeleton. So how do I know which ones I do need to focus on or which areas?

Assessing Core Musculature

So let’s talk a little bit about evaluation techniques. Do we use manual muscle testing? Do we rely on functional movement assessments? Or do we use a combination of both?

As I mentioned earlier, I believe there is limited value in manual muscle testing for the core. While there are validated manual muscle tests with grading scales from zero to five, these can be useful if you’re required to perform them for insurance purposes or pre-authorization. If that’s the case, by all means, go ahead and use them. However, given our understanding that core muscles do not function in isolation, I recommend that the primary focus of your assessment be on functional movement.

That said, there may be value in checking isolated muscle groups to confirm your hypothesis. For instance, if you suspect that the pelvic floor is the primary driver of core dysfunction and the other muscle groups are compensating, it’s reasonable to assess the pelvic floor in isolation to validate your suspicion. This approach is perfectly appropriate and can provide useful insights.

At the same time, it’s essential to incorporate functional movement assessments into your evaluation. We’re not discarding traditional approaches entirely, but we shouldn’t overly rely on manual muscle testing to provide information it isn’t well-suited to reveal. By combining both isolated and functional evaluations, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the patient’s core function and dysfunction.

Subjective Exam

Let’s start with the subjective exam and what we’re looking for during this evaluation portion. One thing to keep in mind is the patient profiles we’ve discussed earlier, which should guide your questioning. These are good points to include in your subjective exam. In addition to generic questions, consider asking about their history of prior injuries, falls, motor vehicle accidents, surgeries, or any other significant events, even if they occurred years or decades ago. Often, the effects of these events on the core may not become apparent until much later.

If your patient has had any births, ask about the type of delivery—vaginal or cesarean—and details such as prolonged labor. These details provide insight into potential impacts on the pelvic floor. Another essential question is whether their pain improves or worsens with specific movements. This is a critical element of most exams, as it helps identify which muscle groups may be driving their symptoms.

Additionally, ask if they are experiencing issues such as urine or stool leakage, painful intimacy, or constipation. These questions might initially seem out of place for patients presenting with low back pain, and many therapists worry about how their patients will perceive such inquiries. I shared the same concern when asking these questions after my pelvic floor training. As someone who was a board-certified clinical specialist in orthopedics for about a decade before transitioning into pelvic floor therapy, I worried patients would find these questions strange or irrelevant.

However, in my years of asking these questions, I’ve never had a patient react negatively. Prefacing the questions with something like, “I’m going to ask you a few questions that might seem unrelated to your main concern, but they can help me understand how the muscles that support your back are functioning. You’re welcome to skip any questions that make you uncomfortable, but if you’re willing to answer, it could provide helpful information for your treatment,” can put your patient at ease. Most patients are relieved to have a provider who knows and can address these functions.

Patients are unlikely to bring up issues like incontinence, bowel problems, or sexual dysfunction on their own, not because of embarrassment, but often because they don’t see how it might connect to their primary complaint or they’re worried about making the provider uncomfortable. Studies show that many patients with these issues don’t disclose them during medical appointments unless prompted.

If you’re still uncomfortable asking these questions directly, you can ease into it by including them on your intake forms. For example, if a patient marks that they’re experiencing urine leakage, it provides a natural opening to ask, “I see here that you noted some issues with urine leakage. Could you tell me more about that? Do you notice it more when your lower back is hurting?” This approach can make these conversations easier and more comfortable for you and the patient.

I encourage you to leave your comfort zone if this is unfamiliar territory. You might find that these questions provide valuable information that helps you develop a more effective treatment plan and expands your ability to address your patients’ needs comprehensively.

Objective Exam

From an objective exam standpoint, let’s discuss what we do, what we look at, and how we approach this process. I’ll walk through a series of tests and measures you can use, explaining why you might use each one and what they can tell you. That said, I’m not suggesting you need to run through every single one of these for every patient with suspected core dysfunction. Realistically, most of us don’t have the time for exhaustive evaluations unless we’re in a unique setting where longer evaluations are possible.

The key is understanding the purpose of each test and using that knowledge to decide which ones are most relevant for the patient in front of you. This will help you rule in or rule out your suspicions about which muscle groups or areas require focus, at least initially.

Remember, evaluation doesn’t have to happen in one session. It’s perfectly fine to break it up over multiple visits. You might start by focusing on the areas that seem most relevant and then expand your evaluation as those areas improve, shifting your attention to other components. This strategy allows you to be thorough while respecting time constraints and prioritizing the patient’s immediate needs.

Visual Observation

Visual observation is an excellent starting point for the objective exam. When we observe symmetry, it’s not because achieving perfect posture is the goal but because asymmetry can provide valuable insights about the individual. An asymmetry might reflect something structural, like a true leg length discrepancy or scoliosis, or indicate something about their core function.

For example, as in Figure 8, consider an individual with visible creases on one side of their body while the other appears smooth.

Figure 8. Example of asymmetrical posture.

This stock image example highlights something commonly observed. While there are many potential causes for this asymmetry—such as weight shifts or structural discrepancies—if these are ruled out, they may point to a core function issue. It could suggest that part of their intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) strategy involves the overactivation of specific muscles on that side, potentially maintaining a subtle rotation. This rotation may not be overtly visible or even easily palpable, but it’s enough to alter how the skin appears in that region.

Similarly, significant differences in shoulder height could suggest that one shoulder is relatively rotated forward. This might indicate asymmetrical muscle activation patterns contributing to the core or shoulder girdle stability. A lateral shift can offer similar information, signaling that the individual isn’t maintaining intra-abdominal pressure through coordinated activation of all the core muscles but compensates with an alternative, less efficient strategy.

While not diagnostic, these observations can serve as important clues for guiding further evaluation and treatment. They help identify areas to investigate more closely and refine our understanding of the patient’s movement strategies and compensatory patterns.

Posture

Let’s talk about posture as part of our evaluation, keeping in mind that posture, in my view, is primarily a source of information rather than an end goal. I’ll also touch on breathing briefly since it’s closely related. Breathing patterns provide a wealth of insight into which muscles may not be working well and can play a critical role in retraining motor control—though that’s another topic.

When considering posture, it’s important to reflect on the relationship between movement and positioning. In school, we were taught to use a plumb line to assess posture, measuring deviations and aiming to correct them to fit an idealized neutral spine position. We focused on minimizing lordosis or kyphosis and aligning everything to a textbook example. While this approach can yield some benefits, there are significant downsides.

We now understand that our bodies are designed for movement, and a rigid approach to posture can introduce unintended problems. I’ve had patients come to me after previous therapy experiences where they were told to move in overly controlled ways, resulting in stiff, unnatural patterns. For instance, they may have been instructed to lift objects in a very precise posture, leading them to adopt robotic, constrained movements that eventually caused new issues. This highlights the need to avoid introducing kinesiophobia—a fear of movement—which can negatively affect the neuromuscular system and the patient’s overall health, social engagement, and quality of life.

While cueing a neutral spine during exercises in a controlled environment is useful, real-life movement is rarely so isolated. We must equip our patients with strategies that will serve them in their daily lives, not just in the clinic. Achieving this involves addressing the underlying core issues rather than hyper-focusing on posture. Often, when core strategies improve, posture naturally adjusts without direct intervention.

That said, there is one important exception: posture matters under heavy load. Whether it’s Olympic-style weightlifting or an activity as simple as walking across a room (depending on the patient’s fitness level), optimal posture helps achieve the best length-tension ratio in the core muscles, providing the strongest support. In such cases, cueing posture is appropriate, as it maximizes muscle efficiency and safety.

However, it’s vital to avoid creating the impression that patients must rigidly maintain one "correct" posture throughout their daily lives. Movement variability is key, and the goal should be to encourage fluid, adaptable strategies rather than fixed patterns. When we address the underlying dysfunction, we provide patients with tools to sustain improved function and comfort over the long term without relying on suboptimal motor patterns to compensate. Hopefully, this perspective on posture and its role in evaluation makes sense.

Breathing

Let’s discuss breathing as part of the evaluation process. I didn’t pay much attention to this during evaluations until I completed my pelvic floor training. Now, I assess breathing in every evaluation, whether or not I suspect a pelvic floor issue. Suboptimal breathing patterns almost always reflect inappropriate pelvic floor and core activation patterns, making it a critical piece of the puzzle.

Common patterns to observe include chest breathing, where patients rely heavily on accessory muscles, often visible as cords of musculature in the neck. You might also notice chest flaring or patients sucking in around their ribs without engaging the lower ribs. Breath holding is another key sign—many of us have joked with patients to avoid passing out during core exercises, but in reality, breath holding indicates the patient is either not ready for the exercise or has ingrained a suboptimal motor pattern.

Breath holding is a compensatory strategy for increased intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). While it can be a valid technique in specific contexts, such as performing a one-rep max in weightlifting, it’s inappropriate for routine activities like opening a door or standing up from a chair. If a patient holds their breath during an exercise, it’s a clear signal that the exercise either exceeds their current capacity or requires a level of motor coordination they haven’t yet mastered. This feedback helps you adjust the exercise by breaking it into smaller components or scaling it back.

Observing patients in multiple positions and throughout their evaluation and treatment sessions to assess breathing effectively. For example, if you notice breath holding during higher-level exercises, it indicates the need to reassess their capabilities or strategies.

Breathing also serves as a powerful tool during higher-level rehabilitation. Once a strong motor pattern between the breath and the pelvic floor is established, breathing can cue the core reflexively during functional activities. For instance, a marathon runner with urine leakage and low back pain won’t be able to engage their pelvic floor while running consciously, but they can focus on a simple breathing rhythm, such as inhaling for three steps and exhaling for three steps. With proper training, this breathing pattern can activate the rest of the core automatically.

In addition to observing breathing, evaluate for diaphragmatic mobility, lower rib cage mobility, and thoracic spine mobility. Restrictions in any of these areas can limit the diaphragm’s ability to function optimally, which, in turn, affects the core. Identifying and addressing these barriers is essential.

To illustrate, using real-time ultrasound imaging can help visualize the direct relationship between the diaphragm and the pelvic floor.

For example, as the bladder moves up, the pelvic floor lifts, and as the bladder moves down, the pelvic floor elongates. This reflexive movement shows that diaphragmatic breathing inherently involves the pelvic floor. Even patients with poor pelvic floor proprioception can benefit from diaphragmatic breathing because it automatically engages the pelvic floor.

You can enhance this reflex by adding overpressure techniques, such as having the patient blow up a balloon or exhale forcefully. While we’ll explore treatment strategies in more detail later, these breathing techniques provide a glimpse into how effective they can be for pelvic floor training and overall core optimization.

Functional Movement Assessment

Functional movement assessment is essential because, at the end of the day, what matters most is how the core supports patients in their daily lives. Gait, for instance, is a common activity of daily living for most patients and offers valuable insight into core function. If gait patterns are suboptimal, it can significantly impact the rehabilitation process.

For a typical patient with low back pain—one without other major injuries, such as a recent ankle sprain—we should observe decent pelvic stability during gait. The iliac crest should remain relatively level, with minimal side-to-side or up-and-down movement. Similarly, patients should demonstrate good stability during single-leg stance, and the movement should look relatively relaxed. Standing on one leg, for most outpatient populations, shouldn’t require maximal core activation. If you observe a patient stiffen dramatically during single-leg stance, it suggests they are compensating for a core control deficiency. While this doesn’t pinpoint the exact issue, it’s a clear sign that something in their core strategy is suboptimal.

Functional movement assessment should encompass a wide range of movements specific to the patient. While core dysfunction isn’t the sole cause of suboptimal movement patterns, it’s often a contributing factor alongside other issues like leg length discrepancies or hip dysfunction. Adding core strategy considerations to your assessment provides a more comprehensive understanding of the patient’s movement.

A helpful exercise is pushing yourself to core fatigue and noticing your substitution patterns. Common compensations include breath holding, increased lumbar lordosis, excessive glute squeezing, leaning, or rotation. Observing these patterns in yourself or others can help you better identify them in patients when they exceed their core capacity for control, strength, or endurance.

Let’s look at some examples. In a patient performing a squat, you might notice valgus knee movement, excessive adduction, or circumduction of the knees.

These patterns often indicate that the core cannot generate sufficient intra-abdominal pressure (IAP), leading the patient to recruit accessory muscles like the piriformis for extra support. Dropping the weight to reduce the challenge and retraining their movement strategy often resolves these compensations.

In another example, a patient might shift their trunk laterally during a squat or widen their base of support to compensate for insufficient IAP.

From a side view, you might observe excessive lumbar lordosis as they activate their erector spinae to compensate for inadequate core support. While these compensations could stem from multiple factors, including weakness in the lower extremities, core dysfunction is often the underlying issue, particularly if other findings from the evaluation support this conclusion.

To address these patterns, it’s crucial to adjust the load or task complexity to a level where the patient can perform the movement with an optimal motor strategy. For instance, reducing the weight and breaking the movement into smaller components can allow the patient to rebuild their core strategy before progressing back to more challenging tasks.

Functional movement assessments provide a global view of how patients use their muscles for real-world activities. They highlight movement strategies, compensations, and areas of dysfunction. However, if you need to narrow your focus, isolating specific muscle groups to evaluate their contributions can provide additional clarity, which we’ll discuss next.

Muscle Activation Assessment

In these next few slides, we’ll discuss how to examine specific muscle groups in a more isolated manner. One way to do this is to request an isolated activation of the muscle group you’re focusing on, such as the pelvic floor or the anterior core, and observe what happens in the rest of the core system. For example, if you ask your patient to activate their pelvic floor and they immediately start holding their breath, it indicates that something about their core activation strategy is not functioning properly, or that other muscles are not collaborating effectively.

Some of the warning signs to watch for include breath holding or a noticeable change in breathing patterns, such as a shift from diaphragmatic breathing to chest breathing. You might notice the patient bulging other core muscles or moving into exaggerated lumbar lordosis. Shaking or jerking of the muscles during activities that are low-load and should be manageable is another sign, as it suggests a motor control issue where the brain and body are not coordinating properly. A lack of coordination in the movement or unusual patterns may also be evident. You could see a loss of balance during tasks like single-leg stance or sudden changes in pelvic tilt, such as quick anterior or posterior tilting. Additionally, you might observe abnormal neck or upper extremity movements, such as shoulder shrugging or scapular dyskinesia.

These are likely things you’ve already observed in your patients during evaluations. While they provide valuable insights into potential motor control deficits or compensatory strategies, they do not give a complete picture. The goal is to piece together all the findings from your evaluation to determine whether the dysfunction originates in the specific muscle group, the core system, or a combination of both. By integrating these observations, you can narrow down the root cause and create a targeted treatment approach.

Pelvic Floor Screen/Palpation

If you want to screen the pelvic floor, there are simple techniques you can use even if you don’t have specific pelvic floor training. You can externally palpate the pelvic floor in positions like hook lying or side lying. To begin, support your patient’s knees and locate the ischial tuberosity, commonly referred to in some regions as the sit bone. Place your fingers on the ischial tuberosity, then rotate your hand so that your fingers are facing up toward their head. This position allows you to feel the pelvic floor on both sides. Keep in mind that pelvic floor movements are subtle, so don’t expect significant shifts, but you can still palpate effectively.

During the palpation, you’re assessing for things like pain provocation and pelvic floor activation. Additionally, you can palpate the hip adductors, as mentioned earlier, since they can offer useful clues about pelvic floor activity. You can also evaluate strength by placing one hand on the pelvic floor and the other on the transverse abdominis (TA). Ask the patient to perform activations such as engaging their abdomen, activating their pelvic floor, or performing what they believe to be a kegel.

What you’re looking for is a lightening of pressure under your pelvic floor hand. This movement is subtle—more of a slight lift—and you should also feel the transverse abdominis co-contract simultaneously. While there is technically a very short delay between pelvic floor activation and TA engagement, it is so brief (on the order of microseconds) that it should feel simultaneous to your hand. Observe whether the patient can perform this activation while breathing normally. If they hold their breath, that’s a sign of suboptimal core coordination. If they are able to engage both the pelvic floor and TA while breathing easily, it’s unlikely the pelvic floor is a significant contributor to their core dysfunction.

It’s also useful to assess repetition. Can the patient repeat the activation consistently, or do they fatigue quickly? If they cannot perform the movement without breath holding or show difficulty maintaining the contraction, this might indicate a contributing factor to their core dysfunction.

In response to a common question about palpation: you don’t need to think posteriorly to the ischial tuberosity. Begin by placing your hand on the ischial tuberosity, with your fingers pointing toward the opposite side of the room. Then rotate your hand so your fingers point straight up toward the head. You don’t need to sink deeply into the tissue—your fingers should rest just inside the ischial tuberosity.

While visual assessments and palpation can feel subjective, they provide valuable information about the patient’s coordination and function. Incorporating these observations into your broader evaluation helps create a clearer picture of the patient’s overall core and pelvic floor health.

Pelvic Floor Activation Assessment

Next, I've got a few special tests. If you want to think of them that way, that can give you some information about core strategy and core control.

Test-Active Straight Leg Raise (ASLR). The first assessment is the active straight leg raise. This test evaluates core recruitment and how effectively the patient can generate force closure across their pelvis when moving their extremities away from their center of gravity. To perform this test, the patient lies in a supine position with their legs extended. They then lift one leg straight up, raising it six to twelve inches off the mat, and place it back down before lifting the other leg. This is done one side at a time. The sequence doesn’t matter; they can start with either the left or the right leg.

The first question to ask the patient is whether one side felt heavier to lift than the other. If the answer is yes, there are further steps you can take to explore the issue.

One approach is to apply pressure with your hands to bring the ASIS towards each other, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Active straight leg raise (ASLR).

While maintaining this anterior compression, ask the patient to repeat the motion with the leg that felt heavier. Then ask them whether the movement feels better, worse, or the same. This replicates anterior force closure. If the patient reports that the movement feels much better and similar to the other side, this indicates a need to focus on the anterior core muscles, particularly the transverse abdominis.

Alternatively, you can place your hands on the PSIS and apply pressure to bring them towards each other. This increases posterior force closure, or compresses the SI joints. If the patient reports improvement with this adjustment, it suggests that the pelvic floor, erector spinae, or multifidus may be primary contributors.

You can also test oblique force closure by placing one hand on the ASIS and the other on the PSIS and applying pressure to bring them towards each other. If this adjustment is the only one that helps, it suggests a lack of coordination throughout the entire core system, indicating the need for comprehensive work on overall core function.

This test not only helps identify specific areas of dysfunction but also guides you in tailoring your intervention to the patient’s needs.

Test-Coccygeal Movement Test. The next test is the coccygeal movement test, which I find particularly useful because it provides specific insights into pelvic floor function while being non-invasive. It can be performed with the patient fully clothed and in a variety of settings, such as an open gym, or wherever the patient feels most comfortable. Additionally, it can be done in several positions, including sitting, side lying, and standing, making it adaptable for different patient populations.

To perform the test, place your hand over the sacrum, ensuring that your middle finger is positioned on the coccyx. This placement is essential because if your entire hand rests on the sacrum, you won’t feel the movement you’re trying to detect. The coccyx may sit lower than expected, so take care to palpate all the way down to locate it. Figure 10 shows an example.

Figure 10. Coccygeal movement test.

Once positioned, ask the patient to contract their pelvic floor. This test can also double as a teaching tool for pelvic floor activation. If they’re performing the contraction correctly, you should feel a very subtle easing of pressure on your finger. This movement reflects the pelvic floor pulling the coccyx forward toward the pubic symphysis. The movement is small and may be difficult to feel initially, so closing your eyes can sometimes help with focus.

If the patient bears down instead of contracting the pelvic floor correctly, you’ll feel an increase in pressure as the coccyx pushes back into your hand. This motor pattern is common in patients with core dysfunction. Bearing down opens the lower end of the canister, reducing intra-abdominal pressure and potentially contributing to their issues.

If the coccyx doesn’t move at all, it indicates that the patient doesn’t know how to activate their pelvic floor volitionally. While this doesn’t necessarily mean they never use their pelvic floor correctly during daily activities, it highlights a lack of proprioceptive awareness. Improving this awareness can be critical, especially as the patient progresses to higher-level core exercises.

This simple and adaptable test provides valuable information for both assessment and treatment planning, making it a useful addition to your toolbox.

Test-Diastiasis Rectus Evaluation. We’ll cover diastasis rectus abdominis in more detail in the next webinar, but since this session is about evaluation, let’s briefly discuss how to assess for it. Diastasis rectus occurs when the soft tissue between the two sides of the rectus abdominis, known as the linea alba, stretches or, less commonly, tears. When this happens, the ability to generate force across the midline may be compromised, which is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the abdominal canister.

To evaluate diastasis rectus, position the patient in hook lying, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Diastiasis rectus evaluation.

Place your fingers perpendicular to their midline, with the front of your hand facing toward the pubic symphysis and the back of your hand facing toward their head. Then, ask the patient to lift their head and shoulders off the table, as shown in the image. While they perform this movement, check if your fingers can sink into an appreciable hole along the midline. Ideally, you should not feel a significant gap or depression. If you do, this indicates the presence of a diastasis, which can interfere with their ability to control intra-abdominal pressure effectively.

If a diastasis is present, the next step is to assess how well the patient can activate their core muscles to reduce the gap. Cue the patient to activate their pelvic floor or transverse abdominis and observe whether the size or depth of the gap decreases. If it does, this is a positive prognostic sign, suggesting that retraining these muscles to pull in the right direction should be relatively straightforward. If it doesn’t, it simply means the retraining process may require more effort and focused intervention.

Abdominal Soft Tissue Mobility

Additionally, abdominal soft tissue mobility should be evaluated. Given the impact of abdominal surgery on core function, assessing the mobility of these tissues can provide valuable insight. Restrictions or adhesions in the abdominal tissues can compromise their ability to move and function properly, further affecting core dynamics. This is a critical component of the overall assessment to ensure that any underlying issues with soft tissue mobility are addressed as part of the treatment plan.

Abdominal scar tissue, particularly when it involves multiple layers, can significantly impact the pelvic floor and abdominal organs. When evaluating these structures, it’s important to assess the involved areas, feeling for restrictions, tenderness, or other abnormalities. This evaluation helps determine how much mobility is compromised and which structures might be affected.

It’s also essential to differentiate between the terms "scar" and "adhesion." A scar refers to the visible tissue at the site of a wound or incision. Adhesions, on the other hand, include outgrowths of scar tissue or guarding patterns that form around the healing area. These adhesions can persist even after the healing process is complete, leading to limited mobility. Therefore, palpation should extend beyond visible scars to evaluate the entire abdomen and identify what is or isn’t moving properly.

Adhesions can form for several reasons, including trauma. Surgery is a form of trauma to the body, and impact traumas like motor vehicle accidents can also contribute. Additionally, emotional trauma may play a role in some cases, as well as inflammation. Chronic inflammatory conditions, such as endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, prolonged gallbladder or appendiceal issues, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis, can create a chronic inflammatory state in the abdomen that encourages adhesion formation.

In response to a question about post-appendectomy patients who’ve had laparoscopic surgery, the most common issue seen is soft tissue mobility restriction. This restriction often impacts the ability of anterior muscles to activate optimally. When this happens, other muscle groups tend to compensate, leading to overactivity in areas like the pelvic floor or spinal muscles. Patients may also develop breath-holding patterns as part of their compensation strategies.

The best way to address these issues is to focus on restoring soft tissue mobility in the abdomen. Once mobility has improved, retrain the involved muscles to function within the newly gained range of motion. This two-step approach can help alleviate compensatory patterns and improve overall function.

Evaluating Mobility Restrictions

When evaluating abdominal mobility restrictions, there are several key things to observe. Start with visual inspection. Look for indentations in the scar tissue, and note whether these are present when the patient is at rest or if they only become visible when the patient is weight bearing. For example, some scars may appear smooth while the patient is lying down but will tuck or pull inward when they stand up. This change often reflects adhesions that pull the scar tissue deeper into the abdomen under the force of gravity.

Patients who have had cesarean sections often describe what is commonly referred to as the "C-section apron." While it’s easy to assume this is caused by a localized fat deposit, it is more often the result of adhesions pulling the scar tissue backward. This pulling effect causes the surrounding tissues to move or shift around the scar, creating the characteristic appearance. Observing how the scar tissue behaves with movement is another important aspect. For instance, does the indentation change or intensify when the patient moves or shifts position?

Tenderness and numbness around the scar are also important findings. These can indicate that the muscles and nerves near the scar tissue have not fully returned to normal function, even long after the surgery. Such issues can perpetuate restrictions and contribute to compensatory patterns elsewhere in the body.

To address these restrictions, gentle mobilizations and scar work can be effective. Techniques like superficial soft tissue mobilization or Kinesio taping may also help improve the mobility and function of these tissues. While we aren’t delving deeply into treatment here, it’s worth noting that even subtle interventions can significantly impact how the soft tissues function and how the patient feels overall.

Cesarean Section/Abdominal Hysterectomy. Here are some examples of what a C-section scar might look like in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Examples of cesarean and and abdominal hysterectomy scars.

In this first image, there isn’t a significant amount of indentation visible across the scar. However, upon closer inspection, you might notice a slightly darker area that appears to sit further back. While it’s difficult to fully assess from just a picture, this could indicate a localized area where the scar tissue may not be moving as freely as the surrounding tissue. In a clinical evaluation, I would check for mobility in this region and assess whether there are any restrictions that extend outward from this portion of the scar into the surrounding tissues.

The next image shows a vertical incision, which you might encounter in older patients or in cases where there was an emergent delivery situation. This type of incision is less common because it is more challenging for the body to heal and can create more difficulties with tissue mobility. However, you will occasionally see these scars, and they should be evaluated for restrictions and mobility just like horizontal scars.

In another example, you can see areas of indentation along the scar. Interestingly, these indentations often occur where the scar is narrower. This suggests there may be scar tissue in those areas that is not moving well, contributing to a lack of mobility and possibly affecting the surrounding tissues.

Each of these examples highlights the importance of evaluating scars in detail. While photos can give us a starting point, nothing replaces hands-on assessment in the clinic to understand how the scar tissue and surrounding structures are behaving. Mobility issues in even small sections of the scar can have broader impacts on core function and overall movement.

Cholecystectomy. Cholecystectomy, or gallbladder removal, is another procedure where scar evaluation can be valuable, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Examples of laparoscopic incisions.

Here’s an example of what laparoscopic incisions for this surgery might look like. Typically, there are four small incisions. This particular incision here, often located just beneath the ribcage, is a common site for adhesion development. These adhesions can sometimes extend upward, limiting the diaphragm’s ability to move fully during its excursion. Such restrictions can have a significant impact on breathing patterns and overall core function.

In contrast, here’s an example of an open gallbladder surgery. These scars are less common today but may still be encountered, particularly in older patients or those who had emergent surgeries. This type of incision involves a larger scar and may be associated with more extensive adhesions, which could further impact tissue mobility and function.

These examples highlight the need to consider both the type and location of surgical scars during evaluation. Whether it’s laparoscopic or open, scars in these regions can influence nearby structures like the diaphragm, the core, and the upper abdominal tissues, making a thorough assessment of soft tissue mobility essential for optimizing patient outcomes.

Appendectomy. Figure 14 shows an example of an appendectomy, which illustrates some of the concepts we discussed earlier regarding laparoscopic surgeries and scar tissue formation.

Figure 14. Appendectomy scars.

While laparoscopic incisions are typically small, this case highlights how scar tissue can develop extensively, even with minimally invasive procedures. This specific example shows a significant buildup of scar tissue that penetrates through multiple layers. Although this spot is a laparoscopic incision, the visible extension of scar tissue suggests this surgery likely started as laparoscopic but then converted to an open procedure. You can see how the scar extends downward, which likely indicates the patient had significant complications, possibly requiring a thorough clean-out and extensive tissue trauma before the appendix was removed.

This example also includes a laparoscopic incision at the top, which is not directly connected to the open incision below but still reflects the potential for deep scar formation. Umbilical incisions are also visible here, another common feature of laparoscopic surgeries. Lastly, there is a straightforward open incision shown, which is less common today but may still be encountered.

The key takeaway is not to assume that small laparoscopic incisions inherently result in minimal scar tissue. Even small incisions can create tunnels where scar tissue develops and extends into deeper layers, potentially restricting tissue mobility. While visual appearance can provide clues, it’s important to confirm your findings through palpation and assessment of soft tissue mobility. However, if you see an extensive scar like this one, it’s a safe assumption that significant soft tissue mobility restrictions are present. In contrast, a smaller, less prominent scar may suggest fewer restrictions, though thorough evaluation is still essential.

The Key

That was a lot of information packed into a relatively short time, but here are the key takeaways. Our bodies are remarkable in their ability to develop substitutionary motor control patterns that allow us to keep functioning, even when musculoskeletal control or activity isn’t ideal. This adaptability is beneficial because it enables us to continue daily activities, even after minor injuries. However, it becomes problematic if the body doesn’t naturally revert to more optimal motor control patterns as healing occurs or as conditions improve.

The first thing we typically lose is motor control. It’s important to approach evaluation with this in mind, particularly when considering visual observation. Visual observations provide valuable clues about what might be happening, but they are rarely the actual problem. For example, postural issues often reflect underlying dysfunctions rather than being the primary cause themselves. Treating posture without addressing its root cause merely replaces one suboptimal motor pattern with another, which can lead to recurring issues or, worse, leave patients disillusioned with therapy.

As we transition to the next session, remember that laying the proper foundation for motor control will make higher-level activities naturally fall into place. Finally, the core becomes more challenged when balance is reduced, so introducing controlled destabilization can be an effective strategy for challenging and improving core function. These principles will set the stage for what we’ll dive into next time.

Question and Answers

Do laparoscopic surgeries affect core and abdominal muscle firing?

Yes, they can. While laparoscopic procedures often leave smaller external scars compared to open surgeries, they can create tunnels of scar tissue between layers of abdominal tissue. These adhesions can restrict movement, as the abdominal layers are designed to slide and glide. In some cases, the resulting immobility can be even more significant than after open surgery, depending on the individual. Despite minimal external scarring, it’s vital to assess and address soft tissue mobility to restore proper muscle function.

How do gender-affirming surgeries impact the pelvic floor?

Gender-affirming surgeries involving incisions through the pelvic floor or pelvic organ prolapse repairs can disrupt optimal muscle function. However, these disruptions can be rehabilitated. Post-surgical rehab is strongly recommended, as it can help restore muscle coordination and core function, enabling patients to recover and regain strength.

Can suboptimal pelvic floor or core control impact exercise resistance and weight-bearing capacity?

Absolutely. Patients with suboptimal pelvic floor or core control are less likely to support heavy loads effectively during movement or exercise, which can compromise their safety. As with any other muscle group, assessing their current capacity is crucial. Gradual progression in strength and coordination can help them safely manage heavier loads over time.

Do core imbalances increase the risk of abdominal or oblique muscle tears?

It’s possible. Core imbalances can lead to situations where stabilizing muscles like the transverse abdominis (TA) are underperforming, forcing larger, movement-focused muscles like the obliques to take on roles they aren’t designed for. This mismatch can lead to fatigue or injury, similar to asking a sprinter to run a marathon. While muscle tears are a potential outcome, core dysfunction more commonly presents as low back pain, hip pain, or related issues. Proper evaluation and targeted intervention can address these imbalances effectively.

If a patient has had cement from an OB-GYN procedure to treat urinary incontinence, how does this affect functional pelvic floor muscle recruitment, and how do you treat compensation due to it?

It depends. The impact varies widely; some patients may experience minimal effects, while others may have significant challenges. To treat compensatory patterns in the core, begin with a detailed evaluation to identify impairments. For example, if the patient holds their breath when activating their pelvic floor, this suggests suboptimal coordination. Treatment will involve layering exercises to address these impairments, with more detail available in the next webinar.

Is maintaining a posterior pelvic tilt outdated, similar to how we used to emphasize alignment?

Yes, permanently holding any specific pelvic tilt is largely outdated. While some patients with core dysfunction may tend to stay in an anterior pelvic tilt, the goal is to encourage movement in and out of various positions throughout the day. There are specific scenarios, like squatting under a heavy load, where a posterior tilt may be beneficial, but teaching patients to maintain this position all the time is unlikely to serve them well.

What do you recommend for treating patients with a large diastasis?

This will be covered in detail in the next webinar, as treatment for a large diastasis involves multiple layers of intervention. Stay tuned for strategies and approaches to address this condition.

Any tricks for teaching patients to engage the pelvic floor during eccentric elongation?