Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, OT And Dyslexia, presented by Magan Gramling, OTR/L, CLT, CTP, CFNIP.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify dyslexia in school-aged children who could benefit from occupational therapy.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the difference between dyslexia, executive functioning, and other common childhood disorders such as ADHD.

- After this course, participants will be able to list interventions that will increase occupational well-being in children with dyslexia.

Introduction

I'm excited to be here today and appreciate you all joining me. I am an occupational therapist, a certified lymphedema therapist, a trauma practitioner, and a functional nutrition-informed practitioner.

I have worked in various settings throughout my career, but my passion for occupational therapy began with pediatrics. That passion has remained a driving force in my work, which is why I am especially excited to share insights with you today on the role of occupational therapy in supporting individuals with dyslexia.

This webinar is designed as an introductory-level session, specifically geared toward practitioners with little prior knowledge of OT’s role in dyslexia. I aim to provide a foundational understanding of how occupational therapy can contribute to interventions and support strategies in this area.

With that, let’s go ahead and get started.

Myth or Fact

Let's begin with a myth-or-fact discussion. I want you to take a moment to consider: Have you ever heard dyslexia referred to as a visual impairment? Has anyone ever told you that dyslexia can be cured? Another common misconception is that dyslexia is either made up or that it only affects children who lack discipline. Additionally, some believe that occupational therapy practitioners do not have a role in treating children with dyslexia.

All of these statements are myths. Dyslexia is not a visual impairment. This misconception dates back to earlier beliefs that dyslexia primarily involved letter reversals. While some children with dyslexia may experience challenges related to visual-motor integration, dyslexia itself is not classified as a visual impairment.

Dyslexia also cannot be cured. It is a lifelong condition that individuals learn to navigate with the right support and interventions.

The idea that dyslexia is fabricated or simply the result of a lack of discipline is entirely false. Dyslexia is a well-documented and researched neurodevelopmental condition that affects reading, writing, and language processing.

As occupational therapy practitioners, we play a significant role in supporting children with dyslexia. Our expertise in sensory processing, motor coordination, executive functioning, and self-regulation can help these children develop strategies to enhance their learning and participation in daily activities.

Definitions

Dyslexia is known by several names, including specific reading disability and developmental dyslexia. For the sake of clarity, I will refer to it simply as dyslexia throughout this webinar. One of the most critical aspects of its definition is the presence of an unexpected difficulty in reading. This difficulty is not related to age, intelligence, socioeconomic status, or any other external factor.

The key term here is unexpected—children with dyslexia often have average to above-average intelligence. It can affect children from affluent backgrounds just as much as those from underprivileged communities. Dyslexia is widespread and does not discriminate based on environment, career, or background.

Dyslexia primarily affects fluency and accuracy in reading. It is neurobiological in origin, meaning it is rooted in the brain’s structure and function. Research indicates that dyslexia can be hereditary, making it a condition that often runs in families. It is also the most common learning disability in the United States. Approximately one in five individuals has dyslexia, and it accounts for up to 85% of all learning disabilities.

Like many other neurodevelopmental conditions, dyslexia is a continuum ranging from mild to severe. Possible precursors may help with early detection, though research on this remains divided. Some potential early indicators include fine motor delays, a connection between dyslexia and dysgraphia, and speech-language difficulties. Additionally, some children with dyslexia may present with visual-motor impairments in early grades (kindergarten through third grade).

Dyslexia manifests differently over time. In early elementary years, it is most apparent in reading difficulties, but by fourth grade and beyond, challenges may become more pronounced in math-related tasks as well.

For those interested in further resources, I highly recommend the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity. It is an excellent source of information and research on dyslexia, offering valuable insights for educators, practitioners, and families.

Why Does It Matter?

Understanding why dyslexia matters is crucial, particularly when considering the broader implications for learning, mental health, and overall participation in daily life. Research shows that nearly half of all school-age children who qualify for an IEP or 504 plan do so because of a learning disability, and almost 90% of those learning disabilities are related to reading.

For occupational therapy, this is significant because reading impairments can lead to occupational deprivation and occupational injustice. When individuals cannot participate fully in society due to difficulties with reading, they experience occupational injustice, limiting their ability to engage in essential and meaningful activities. If we consider all the tasks in daily life that require reading—schoolwork, filling out forms, reading instructions, even engaging in leisure activities like reading for pleasure—it becomes clear that individuals with dyslexia face frequent barriers that can lead to occupational deprivation.

Dyslexia also impacts mental health. Research has shown that individuals with dyslexia experience higher levels of stress and anxiety due to repeated experiences of failure compared to their peers. One particular study explored this connection and introduced an interesting framework known as the DE-STRESS Model to help individuals manage these challenges.

The DE-STRESS Model is an acronym that outlines key interventions:

- D: Define dyslexia and how it presents for the individual. Understanding how dyslexia uniquely affects each person is the first step in developing strategies.

- E: Educate the client on how dyslexia impacts their life. Providing knowledge about their condition empowers individuals and promotes self-advocacy.

- S: Speculate—look ahead to anticipate potential difficulties and develop proactive strategies.

- T: Teach clients strategies that maximize success and minimize frustration.

- R: Reduce threats by shaping the learning environment to be more accessible and supportive, which is a critical role for occupational therapy practitioners.

- E: Encourage healthy habits such as exercise, proper nutrition, and hydration to support overall cognitive function and learning.

- S: Support success through repeated mastery, reinforcing the just-right challenge concept familiar to OTPs. Providing individuals with opportunities for achievable challenges builds confidence and competence.

- S: Strategize ways to manage stress, improve resilience, and enhance self-esteem.

As occupational therapy practitioners, we recognize that occupation is medicine. Engaging in meaningful activities, whether being in nature, walking, participating in social groups, practicing yoga, or meditation, can significantly reduce stress and anxiety. While stress itself is not inherently negative—it can serve as a motivator—chronic stress and anxiety can be detrimental to learning and well-being. It is important to differentiate the two: stress is a response to a present challenge, whereas anxiety is worry about the future or something that has not yet happened.

Because anxiety is so prevalent in individuals with dyslexia, integrating mindfulness-based practices into interventions can be incredibly beneficial. Whether through structured activities or daily routines, these strategies help regulate emotions, manage stress, and promote overall well-being.

Functional MRIs (fMRI)

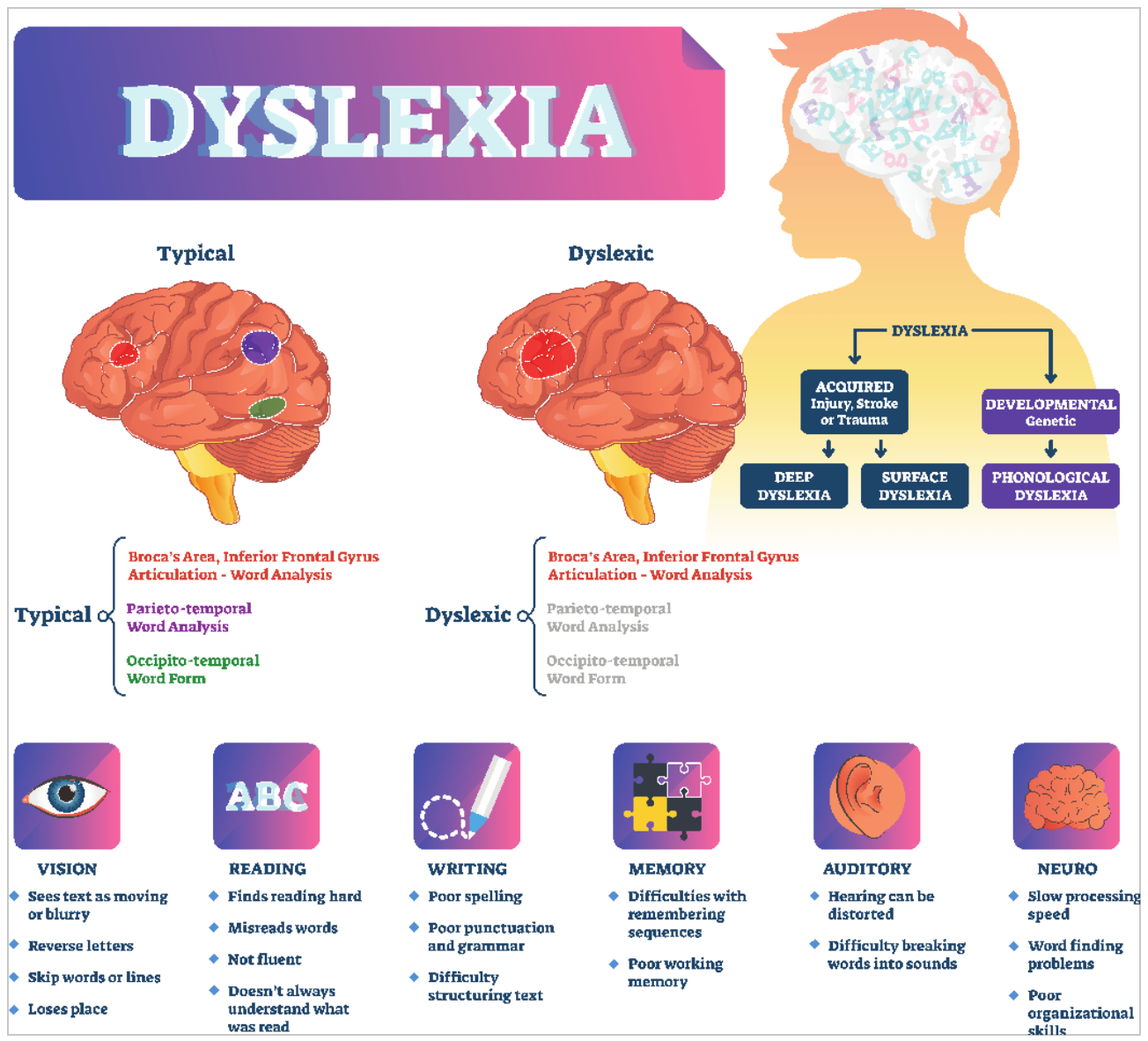

Functional MRIs is a relatively new area for treating people with dyslexia (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Infographic about dyslexia (Click here to enlarge the image).

Advancements in neuroimaging have allowed us to better understand the differences in brain function between individuals with dyslexia and those without. When we begin reading, the process typically starts in the right hemisphere, but shortly after, it shifts to the left hemisphere, where the brain’s primary reading centers are located. However, for individuals with dyslexia, this shift does not occur in the same way.

Functional MRI (fMRI) studies have revealed that individuals with dyslexia rely more heavily on imaging pathways in the brain than typical readers. They show increased connectivity between visual pathways and the prefrontal cortex, which is the region responsible for executive functioning skills such as attention, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. This reinforces the understanding that dyslexia is not simply difficulty with reading—it is a whole-brain condition rather than an isolated issue within the left temporal lobe's reading centers.

Another significant finding from neuroimaging studies is that individuals with dyslexia exhibit increased connectivity to the limbic system, which governs emotions and behavior regulation. The amygdala, a key structure within the limbic system responsible for processing emotions, is more engaged in individuals with dyslexia. This research suggests that dyslexia is, at least in part, a disorder of attention. We will discuss attention and executive functioning more in-depth later, but this finding highlights why children with dyslexia often appear to struggle with focus and mental effort when reading.

One of the most striking discoveries is that individuals with dyslexia expend significantly more effort while reading. Since their brains do not process words using the typical left-hemisphere reading centers, they must sound out each word rather than automatically recognize high-frequency or sight words. This increased cognitive load makes reading a far more strenuous task.

However, an unexpected but fascinating finding is that individuals with dyslexia often perform better in reading comprehension than typical readers. They tend to develop strong comprehension skills because they read for meaning rather than sound, particularly when information is read aloud. This reinforces the importance of multisensory learning approaches and the role of audiobooks or read-aloud accommodations for children with dyslexia.

As occupational therapy practitioners, especially in school-based settings, we often work with children who do not have a formal diagnosis of dyslexia. In my own practice, particularly through my nature-based work, I frequently encounter neurodivergent children who attend programs for health and wellness rather than through a traditional medical referral. While some children come with a formal diagnosis, many do not, requiring us as practitioners to take on a detective role, observing their behaviors, challenges, and strengths to determine what interventions may be most effective. This investigative approach allows us to tailor support strategies to each child’s unique needs, even without an official diagnosis.

OT & Dyslexia

I created this chart to show you the overlap between ADHD, executive dysfunction, and dyslexia because there is a good bit of overlap.

| ADHD | ED | Dyslexia |

Attention difficulties | x | x | x |

Self-control | x | x |

|

Emotional dysregulation | x | x | x |

Working memory | x | x | x |

Transitions (task switching) | x | x |

|

Initiation (Starting a task) | x | x | x |

Organization | x | x | X (reading & writing) |

Planning | x | x | x |

Impulsivity | x | x |

|

Distraction | x | x |

|

Difficulty taking turns | x | x |

|

Clinical diagnosis w/possible chemical deficits | x |

| x |

Visual motor deficits (potentially, not always) |

|

| x |

Difficulties with communication |

| x | x |

Brain fatigue with learning |

| x | x(can look like not completing tasks) |

Grammar & spelling difficulties |

|

| x |

Reading comprehension difficulties |

|

| x |

Task completion | x | x | x |

Anxiety or low self-esteem | x? | x | x |

A lot of the kids I have seen with dyslexia initially came to me under the assumption that they had ADHD. When we look at the chart, we can see that kids with dyslexia, executive dysfunction, and ADHD all have difficulties with attention. They may also struggle with emotional regulation, working memory, initiation, organization, and planning.

Both ADHD and dyslexia can have clinical diagnoses. They can also both present challenges with task completion and may contribute to anxiety or low self-esteem.

When we examine dyslexia and executive dysfunction, we see that nearly every trait associated with dyslexia is also a characteristic of executive dysfunction. As discussed earlier, executive functioning is closely linked to the prefrontal cortex, which is critical in regulating cognitive processes.

Executive functioning is defined as a high-level cognitive skill that controls other functions and behaviors. It is essential for a child's behavior, emotional regulation, and social interactions. A helpful way to visualize executive functioning is through the analogy of an orchestra, where executive functioning is the conductor. The various tasks—attention, working memory, and perception—are individual instruments, each playing a role in cognitive processing. The conductor (executive functioning) ensures that everything is synchronized, guiding and directing the orchestra as a whole.

Executive functioning is a core area of focus for occupational therapy, particularly in how our scope aligns with supporting children with dyslexia. Many of the challenges these children face are directly related to executive dysfunction, which impacts their ability to organize thoughts, maintain focus, and regulate emotions effectively.

Table 1 Definitions of Components Included in the Active View of Reading |

|

Component | Definition based on Duke and Cartwright (2021) |

Self-regulation |

|

Executive function | Self-regulatory neurocognitive processes used in complex, goal-directed tasks. Includes three core skills of cognitive flexibility, working memory, and inhibitory control. |

Motivation | Students’ interest in reading, perceived sense of value of reading, mindsets around reading success and difficulty, and active participation in reading (i.e., interaction with text) |

Strategy | Goal-directed approaches to modify how a student decodes text, understands words, and constructs meaning |

Source: Recreated from Duke, N.K., & Cartwright, K.B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Read Res Q, 56(S1), S25– S44. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.411

This chart comes from a 2021 psychology journal article that explored reading as a social justice issue. This perspective highlights the broader implications of literacy and access to effective interventions, reinforcing the critical need to address executive functioning challenges in children with dyslexia. If reading is a social justice issue, we recognize it as an occupational justice issue, given the profound impact that literacy has on a child's ability to participate fully in education, work, and daily life.

The article introduced the Active View of Reading, contrasting with traditional, mainstream perspectives on literacy development. Researchers found that reading interventions were most effective when integrated with executive functioning tasks, specifically inhibition, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and motivation—all areas within OT's scope of practice.

Motivation, a key component of many OT theories and models, is crucial in literacy and learning. The Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) is one of the most well-known frameworks that emphasizes the role of motivation in occupational engagement. The article’s findings align with this perspective, showing that reading skills improve when interventions incorporate executive functioning tasks alongside literacy instruction. This is why the researchers titled their framework the Active View of Reading—it recognizes reading as a dynamic, interactive process that relies on multiple cognitive and executive function skills rather than a passive or isolated ability.

Executive Functioning

Other executive functioning skills will be attention, problem-solving, planning, organization, and perception, based on the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF).

Table 9. Client factors, cont. |

|

Category | Examples Relevant to Occupational Therapy Practice |

Body Functions (cont.) |

|

Mental functions |

|

Specific mental functions |

|

| Judgment, concept formation, metacognition, executive functions, praxis, cognitive flexibility, insight |

| Sustained shifting and divided attention, concentration, distractibility |

| Short-term, long-term, and working memory |

| Discrimination of sensations (e.g., auditory, tactile, visual, olfactory, gustatory, vestibular, proprioceptive) |

| Control and content of thought, awareness of reality vs. delusions, logical and coherent thought |

| Mental functions that regulate the speed, response, quality, and time of motor production, such as restlessness, toe tapping, or hand wringing, in response to inner tension |

| Regulation and range of emotions, appropriateness of emotions, including anger, love, tension, and anxiety; lability of emotions |

Here is another chart from the OTPF.

Body Structures-”Anatomical parts of the body, such as organs, limbs, and their components” that support body function (WHO, 2021, p. 10). This section of the table is organized according to the ICF classifications; for fuller descriptions and definitions, refer to WHO (2001). |

|

| Occupational therapy practitioners have knowledge of body structures and understand broadly the interaction that occurs between these structures to support health, well-being, and participation in life through engagement in occupation. |

Executive functioning skills fall well within our occupational therapy scope of practice because they directly influence all occupations, many performance patterns, and most performance skills. A couple of executive functioning assessments that I find particularly useful include the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), which provides valuable insight into a child's executive functioning in daily life. Another well-regarded test I have not personally used is the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, which assesses cognitive flexibility and problem-solving abilities.

This discussion highlights how executive functioning challenges manifest in occupational therapy practice. As we reflect on these skills, we can likely think of children we treat who struggle with executive function, as well as our personal experiences—whether as practitioners, parents, or in moments of stress or illness, when our own executive functioning is not at its best. When our cognitive efficiency is compromised, we often see a decline in performance skills and a disruption in occupational balance.

Referencing the OTPF, we see that executive functioning relates to mental functions, particularly higher-level cognition. A key component of this is cognitive flexibility, which is closely tied to concept formation and imagination. Cognitive flexibility allows individuals to integrate an idea into an existing schema, essential for adapting to new situations. Other critical areas include attention, divided attention, and distractibility, all of which overlap significantly with ADHD and dyslexia. Perception, which involves discriminating sensations and processing sensory input, is another area where occupational therapy interventions can be highly effective.

A study examining executive function in children with dyslexia found that they scored lower on executive skills than their peers without dyslexia. The specific executive function skills assessed included inhibition, initiation, working memory, emotional regulation, planning, and organization. These findings reinforce what many OTPs observe in practice—children with dyslexia often face cognitive and self-regulation challenges beyond reading difficulties.

In my own experience using the BRIEF, parents of children with dyslexia or executive dysfunction frequently report that their children:

- Do not think about consequences before acting.

- Take longer to recover from meltdowns or have more frequent emotional outbursts than their peers.

- Struggle with estimating how long a task will take.

- Have difficulty completing multi-step tasks, such as following a morning routine with multiple sequential actions.

For example, if I tell my daughter, “Go upstairs, brush your teeth, put on your clothes, and when you come down, we’ll pack your lunch,” remembering those steps would be much more challenging for someone with executive dysfunction. Breaking down instructions into smaller, manageable parts is often necessary for supporting children with dyslexia and executive function deficits.

When framed this way, I hope it demystifies the role of occupational therapy in treating dyslexia. Many OTPs feel uncertain about their role in working with children with dyslexia, which can lead to hesitancy in assessing and treating it.

A 2023 study in Australia surveyed occupational therapy practitioners, speech-language pathologists (SLPs), and school psychologists to assess their confidence in evaluating and treating children with dyslexia. Interestingly, all practitioners needed more education on dyslexia, particularly intervention strategies. While SLPs and school psychologists reported greater familiarity with dyslexia than OTPs, all groups acknowledged a desire for additional training.

Another study reinforced my perspective on this issue, stating: “This state of affairs is concerning, as OTPs play an integral role in assisting children with dyslexia.” When practitioners lack confidence, they may shy away from treating dyslexia, which can contribute to underdiagnosed, misdiagnosed, or undertreated children. As a profession, we must recognize that executive functioning and literacy challenges are within our domain, and our interventions can be transformative for children with dyslexia.

Interventions

Early intervention is key when addressing dyslexia. In my experience working in Alabama, I’ve noticed that it’s common for school systems to wait until third grade before evaluating a child for a potential IEP or 504 plan. However, if a child has been struggling with school since kindergarten, first, or even second grade, waiting that long can significantly delay getting them the support they need.

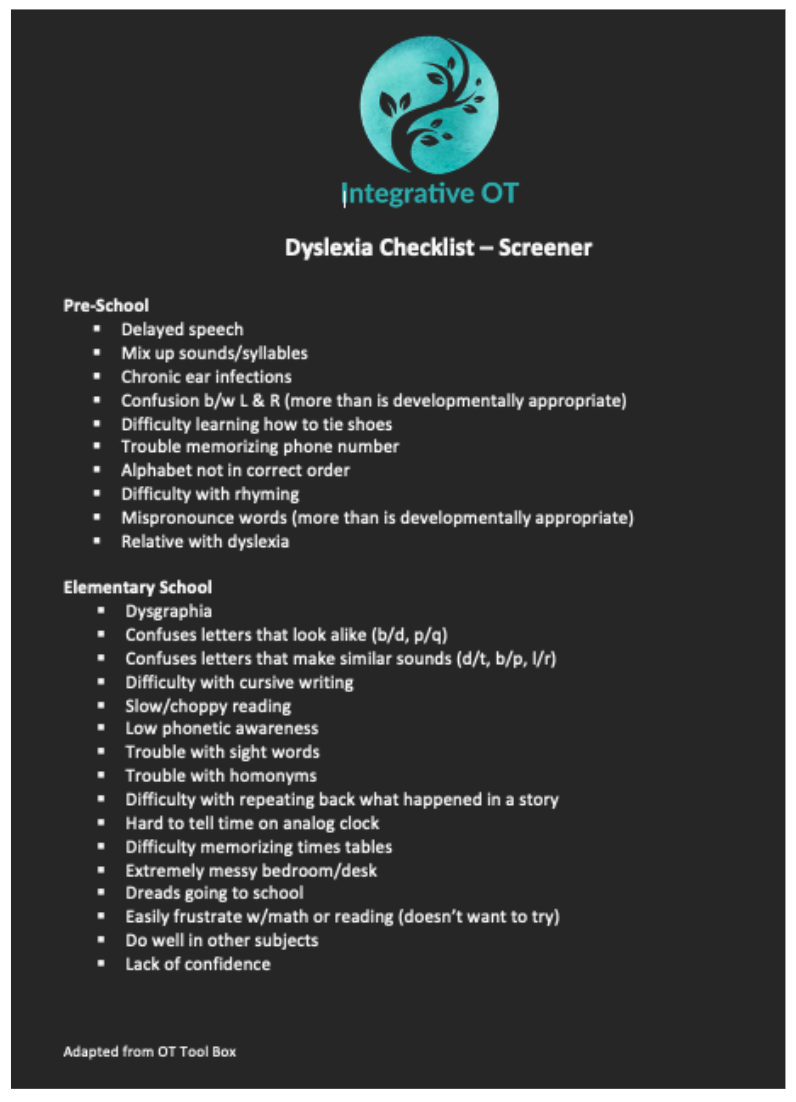

Screeners are incredibly useful in identifying early signs of dyslexia. I created the screener in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Dyslexia screener. (Click here to enlarge this image.)

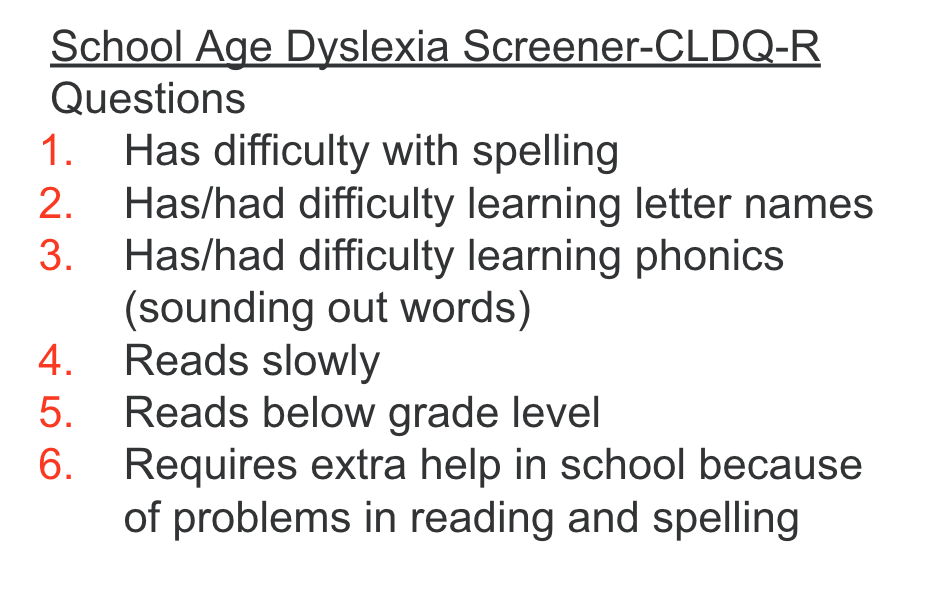

Figure 3 shows the Colorado Learning Disabilities Questionnaire.

Figure 3. Colorado Learning Disabilities Questionnaire.

Another screener I highly recommend is EFFORTS (Executive Functioning and Occupational Roles), which is particularly useful for occupational therapists. I divided my screener into preschool and elementary age groups because I firmly believe that the earlier we recognize red flags, the sooner we can intervene and provide appropriate services.

Key Red Flags

- Difficulty automatically naming letters of the alphabet, which is an auditory sequencing skill that should develop through rote memory (e.g., singing the alphabet song).

- Challenges with rhyming, which indicate difficulty recognizing sound patterns in words.

- Struggling with inserting or deleting letters and sounding out sight words, high-frequency words that cannot be phonetically decoded and must be recognized instantly.

- Slower vocabulary development and difficulty learning new words may be linked to late speech development or chronic ear infections in early childhood.

- Difficulty with rote memory tasks, such as reciting the days of the week, months of the year, or even memorizing a phone number—something many parents teach their children for safety.

- Word retrieval difficulties are often linked to dysgraphia, a condition frequently coexisting with dyslexia.

- Trouble following multi-step directions, which is a hallmark of working memory deficits.

- Difficulty telling time on an analog clock, which requires strong visual-spatial skills.

- Delayed reading milestones include not reading sentences by the end of kindergarten, text by the end of first grade, or with expression by the end of second grade.

Teachers I work with have found these indicators particularly useful when screening for dyslexia. Another key sign is having a limited vocabulary despite strong intelligence, reinforcing the unexpected nature of dyslexia—it’s not an issue of intelligence but rather fluency, accuracy, and word acquisition.

Interventions for Dyslexia

When designing interventions for dyslexia, we should prioritize multisensory and kinesthetic learning while embracing a multidisciplinary approach. Collaboration with SLPs, reading coaches, teachers, and school psychologists can create a more effective support system if working in a school setting or an outpatient clinic.

Research shows that kinesthetic learning is one of the best methods for children with dyslexia, emphasizing the importance of hands-on and movement-based activities. A key intervention component is vocabulary development, which involves understanding syntax (word order) and semantics (word meaning). Since children with dyslexia read for meaning rather than sound, interventions should align with how they naturally process information.

Advocating for Evidence-Based Reading Programs

One of the biggest challenges I’ve encountered when working with school systems is advocating for the Orton-Gillingham curriculum, which is considered the gold standard for dyslexia interventions. This approach is multisensory, structured, and sequential, incorporating techniques like syllable tapping to reinforce phonemic awareness. As occupational therapists, advocacy is an important part of our role, and supporting evidence-based interventions like Orton-Gillingham can make a significant impact.

Accommodations for Dyslexia

Several classroom accommodations can support students with dyslexia:

- Using a scribe to assist with note-taking or written assignments reduces the impact of dysgraphia.

- Oral testing instead of written tests when the goal is to assess comprehension rather than handwriting skills.

- Modifying reading materials ensures students access the content at their reading level while still engaging with their peers' subject matter.

- Adjusting the environment through assistive technology and adaptive tools and creating stress-free learning spaces, as outlined in the DE-STRESS model.

- Big-picture teaching emphasizes the key learning objective rather than rigid adherence to traditional teaching methods. For example, if the goal is reading comprehension, a parent or aide could read the passage aloud while the student answers the questions.

Test-Taking Strategies

One effective strategy is having students read the test questions before starting a passage or activity. This helps direct their attention to key information, improving focus and comprehension. Additionally, the IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) law requires that any printed text used in schools be available in audiobook format, making audiobooks and podcasts valuable tools for students with dyslexia.

Multisensory Vocabulary Learning

A great way to reinforce new vocabulary is through multisensory activities, such as:

- Drawing pictures of the word.

- Acting out the meaning, like a game of charades.

- Identifying synonyms and antonyms.

- Creating stories or sentences using the word in context.

Sensory and Reflex Integration

Children with dyslexia often have comorbidities, including sensory processing challenges. Regardless of whether a child has sensory processing disorder (SPD), proprioceptive input before a seated task benefits all children. Many classrooms incorporate brain breaks before academic work, which can improve focus and self-regulation.

Additionally, primitive reflex integration is something I assess in every evaluation. In my experience, every child I have worked with who has ADHD or dyslexia has retained at least one primitive reflex. Integrating these reflexes through targeted exercises for 30 days can lead to remarkable improvements in attention, coordination, and learning.

Executive Functioning Interventions

A fascinating 2021 study found that targeting visual-motor integration and executive functioning skills together resulted in the greatest improvements in reading ability. Activities from the study included:

- Memory games with pictures.

- Catching a ball while jumping.

- Obstacle courses on uneven surfaces.

- Ball games like bowling and basketball to improve motor planning.

Other effective executive functioning interventions include:

- Board games like Perfection and Battleship to improve focus and cognitive flexibility.

- Obstacle courses promote bilateral coordination and motor planning.

- Games like Red Light, Green Light, and Simon Says reinforce inhibition and self-control.

- Mindfulness activities, such as body scans and check-ins using a ball-passing game.

Dyslexia Strengths

The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity highlights the strengths of individuals with dyslexia, emphasizing that nearly 75% of entrepreneurs are dyslexic. Their strengths include:

- Big-picture thinking and problem-solving skills are essential for entrepreneurship.

- Artistic and creative talents, leading to strengths in design, storytelling, and analogical thinking.

- Stronger recall of facts presented in story format, making narrative-based learning highly effective.

- Heightened social skills and ability to excel at non-reading tasks.

As occupational therapists, we recognize that occupation is medicine. Encouraging children with dyslexia to engage in non-academic occupations—such as sports, music, theater, or hands-on creative pursuits—not only builds confidence but also promotes occupational balance.

Summary

I hope this webinar has strengthened your confidence in supporting children with dyslexia through targeted interventions while addressing the executive functioning challenges integral to their success. These areas fall squarely within occupational therapy’s scope of practice, and with the right strategies, we can empower children with dyslexia to thrive not only academically but also socially and emotionally. By fostering their strengths, providing meaningful interventions, and advocating for their needs, we can help them navigate challenges with confidence and success.

Questions and Answers

Is executive functioning commonly diagnosed?

No, executive functioning is not typically diagnosed as a standalone condition. Occupational therapists cannot diagnose it, but we can often identify executive dysfunction through observation and assessment. It is not easily or commonly diagnosed but is more of a clinical presentation that OTs recognize and address through intervention.

What is the name of the screener for executive functioning and occupational roles?

The screener is the Executive Functioning with Occupational Roles Test (EFFORT).

What does "reading for meaning" mean?

Reading for meaning refers to reading comprehension. It is understanding a passage's overall message or moral rather than just decoding words. Children with dyslexia, for example, are often more focused on extracting meaning from a passage rather than simply reading for the sake of reading.

How many criteria must be met to receive a diagnosis of dyslexia?

Dyslexia is classified as a specific reading disability in the DSM, but occupational therapists do not diagnose it. A diagnosis typically comes from a pediatrician or a special education team through an IEP evaluation. The specific criteria depend on the assessment tools used by the diagnosing professionals.

How can teachers modify reading assignments for students at different reading levels?

Teachers typically have a variety of books available at different reading levels, allowing them to assign materials appropriate for each student. For example, if a class is reading Little Red Riding Hood, a teacher or aide might adjust the wording of the passage to match a struggling student’s reading level while still maintaining the story’s meaning and comprehension goals.

What is the name of the gold-standard curriculum for dyslexia intervention?

Orton-Gillingham is considered the gold standard for dyslexia intervention.

What are your thoughts on special fonts for dyslexia?

While I have not personally used them in therapy, I have seen students use dyslexia-friendly fonts on their Google Chromebooks or Kindles. I have heard positive feedback from students who feel these fonts improve readability.

What is the DE-STRESS acronym?

The DE-STRESS acronym comes from a journal article referenced in the provided research handout. If you’d like to learn more, refer to the original article for details.

How often should primitive reflex integration exercises be performed?

Reflex integration exercises should be done consistently, ideally two to three times a day. For example, if working on integrating the Asymmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex (ATNR) using the "robot" or "lizard" exercise, I typically recommend 10 repetitions in the morning and at night for 30 days. Some children may need additional time, but I have rarely needed to continue for over three months.

What are the three main primitive reflexes?

There are more than three primitive reflexes, but the ones I most commonly see retained in children are the Asymmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex (ATNR), the Symmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex (STNR), and the Spinal Galant Reflex.

What are some good creative resource websites?

The Yale Center for Creativity and Harvard have excellent websites with valuable resources.

Is there an unintegrated reflex that is most commonly associated with dyslexia?

The most commonly retained reflexes in children with dyslexia are the ATNR and STNR. The Spinal Galant Reflex can also be retained in some cases, but ATNR and STNR are the most frequently observed.

Do you see many children with both dyslexia and ADHD?

Many children are identified as having both dyslexia and ADHD, but once executive functioning skills, diet, and sleep are addressed, I often see significant improvement in attention and hyperactivity. If hyperactivity is removed from the equation, many aspects of inattention overlap with the executive functioning challenges seen in dyslexia. While some children may have both conditions, others may present overlapping symptoms that can improve with targeted interventions.

Does dyslexia contribute to balance issues?

I have not personally observed a strong connection between dyslexia and vestibular system dysfunction. However, research suggests links between dyslexia and visual-motor integration challenges. If you want to explore this further, I recommend reviewing the visual processing article mentioned earlier.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Gramling, M. (2025). OT and dyslexia. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5785. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com