Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Overview And Importance Of Pelvic Health: Postnatal Pelvic Health Virtual Conference, presented by Jessica McHugh Conlin, PhD, OTR/L, BCP, CPT.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the need to support women during the postnatal period and beyond.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize how postnatal pelvic health affects other areas of maternal health.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify occupational therapy’s role in postnatal pelvic health care.

Overview of Sessions

Thank you all for joining us today. As the guest editor of this series, I am truly excited about this topic and the important area of practice we’ll be discussing. Over this week, we’ll delve into postnatal pelvic health, a critical yet often overlooked aspect of maternal care. We have five outstanding sessions, each led by experts in the field, and I’m thrilled to explore this subject with all of you.

Today’s session provides an overview of postnatal pelvic health and why it is essential to address it. Throughout the week, you’ll hear from professionals who bring a wealth of knowledge and experience to this conversation. The title of today’s presentation is Overview and Importance of Pelvic Health as part of the Postnatal Pelvic Health Virtual Conference.

This presentation is intended as an introductory course designed to provide a broad overview of maternal health, pelvic health therapy, and the specific contributions of occupational therapy in this area. My hope is that you’ll walk away from today’s session with a deeper understanding of the topic, actionable insights, and practical tools to integrate into your work with clients and patients.

Once again, welcome to this virtual conference. I’m so glad to have you here, and I look forward to an engaging week of learning and collaboration.

Today, we’ll discuss the importance of overall maternal health. From there, I’ll briefly overview the core and pelvic floor. While we’ll explore these topics in greater detail throughout the week, today’s goal is to lay the groundwork by highlighting key landmarks and sharing some basic foundational information.

Next, we’ll define pelvic health therapy and examine why occupational therapy is vital in this area. Finally, we’ll wrap up the session with two case studies that illustrate practical applications and demonstrate how these concepts can be implemented in real-world scenarios.

Let’s dive in!

Introduction

My name is Jessica McHugh Conlin, and I’d like to take a moment to share a bit about my background and the journey that brought me to where I am today. My career began in education as a special education teacher. I worked with children with autism, running a program that served students from kindergarten through sixth grade. During this time, I had the opportunity to collaborate with an incredible occupational therapist, who introduced me to the field and its broad scope. That experience planted the seed for my eventual transition into occupational therapy.

When I became pregnant with my first son 20 years ago, I left teaching and took on a role as the aquatics director for a YMCA. In this role, I managed individual and group programs for various participants, from children to older adults. It was also my first experience working with prenatal and postnatal individuals. I created and led a pre-and postnatal aqua exercise class, which I particularly enjoyed as I was pregnant then. This hands-on experience taught me so much about the needs of this population. Additionally, I developed and ran a one-on-one program for children with disabilities called Starfish. Through these experiences, I felt a deeper pull toward occupational therapy.

Eventually, I pursued this passion and returned to school, earning my master’s degree in OT from the University of South Dakota. After graduating, I founded a pediatric therapy company called AbleKids, which provided OT, PT, and speech therapy services. The company grew much larger than I had anticipated, and in 2016, I chose to sell it to a larger organization. Around the same time, I began working as an adjunct faculty member at the University of South Dakota and later joined the faculty full-time in 2017.

During this period, my husband and I also operated a CrossFit gym. Running the gym was a wonderful experience that allowed me to work closely with women, helping them achieve their health and fitness goals. I became certified in personal training and nutrition, which added another dimension to my ability to support women, particularly in group settings. This experience deepened my understanding of women’s health and reinforced my desire to focus on this population.

After deciding to leave academia, my husband and I started a nonprofit organization called Healthy360. While much of my OT practice has been in pediatrics, this nonprofit allowed me to shift my focus to postnatal women and their infants. In my part of the organization, I work exclusively with postnatal mothers, tracking their health and well-being and their infants’ development for a year. I meet with the mothers within the first month of birth and then again at three, six, nine, and twelve months postpartum.

During these visits, I address a variety of areas, including postnatal pelvic health, nutrition, sleep, stress, and anxiety—key factors that affect the transition into motherhood. I monitor the infants' developmental milestones, hearing, sleep, and feeding. If the mother is breastfeeding, I provide lactation support. I aim to offer a holistic approach to care while referring families to other specialists when their needs extend beyond my expertise.

This journey has been both rewarding and humbling. It has allowed me to integrate my experiences in education, fitness, pediatrics, and occupational therapy to serve women and families meaningfully.

Why Does Maternal Health Matter?

Why is maternal health so important? In the United States alone, there are just under 3.7 million live births each year. While the postnatal period is often a time of joy and excitement, it also presents a host of challenges for many women.

Some of the most commonly reported stressors include physical and emotional difficulties, balancing the demands of a new baby with other responsibilities, and feelings of loneliness. Research into this population highlights additional struggles that women often face, such as a lack of time for self-care—particularly when it comes to nutrition and sleep—postpartum depression, and pelvic floor dysfunction, which is a key topic of our discussion today.

Women also frequently report feeling overwhelmed and overloaded, coupled with fears or anxieties about their child’s well-being. These stressors create a complex and often all-encompassing experience during a time that is supposed to feel exciting and fulfilling. Understanding and addressing these challenges is critical to supporting maternal health and ensuring that women not only survive but thrive during this transformative period.

Postpartum Depression

Before we delve into the topic of the pelvic floor and pelvic health, I want to take a moment to discuss postpartum depression, as it is a significant aspect of the postnatal experience for many women. Unfortunately, this condition is often dismissed or goes unspoken because many women fear opening up about their struggles.

Statistics reveal that between 1 in 10 and 1 in 7, women experience some level of postpartum depression during the first year after giving birth. Many report feeling like they carry the majority of the burden of caring for their children and often find parenting more challenging than fathers do. Despite its prevalence, research indicates that about 50 percent of postpartum depression cases go undiagnosed or underdiagnosed. This is frequently due to barriers such as fear of disclosure, stigma, and concerns about privacy.

Currently, it is estimated that close to 1 million women in the United States are suffering from postpartum depression. Importantly, research has shown a link between urinary incontinence and an increased risk of developing postpartum depression. This connection underscores the need to address pelvic health as part of comprehensive postnatal care. By creating a safe space for women to discuss these challenges and receive support, we can help break down barriers and ensure that their mental and physical health are prioritized.

The Core

Let’s begin by exploring the main focus of this conference: pelvic health and its relationship to pregnancy. Before we explore the pelvic floor in-depth, I want to briefly overview the anatomy involved to help orient everyone to the structures we’ll discuss. Part two of this series will go into much more detail on this topic, but for now, I’d like to highlight some key points and give a foundational understanding of how these systems work together.

When discussing pelvic health, we can’t overlook the core, which plays a crucial role but is often underrated or forgotten in these conversations. Most people, when they think of the core, focus solely on the abdominal muscles, but it’s so much more than that. The core and pelvic floor are interconnected; understanding this relationship is vital to effectively addressing pelvic health.

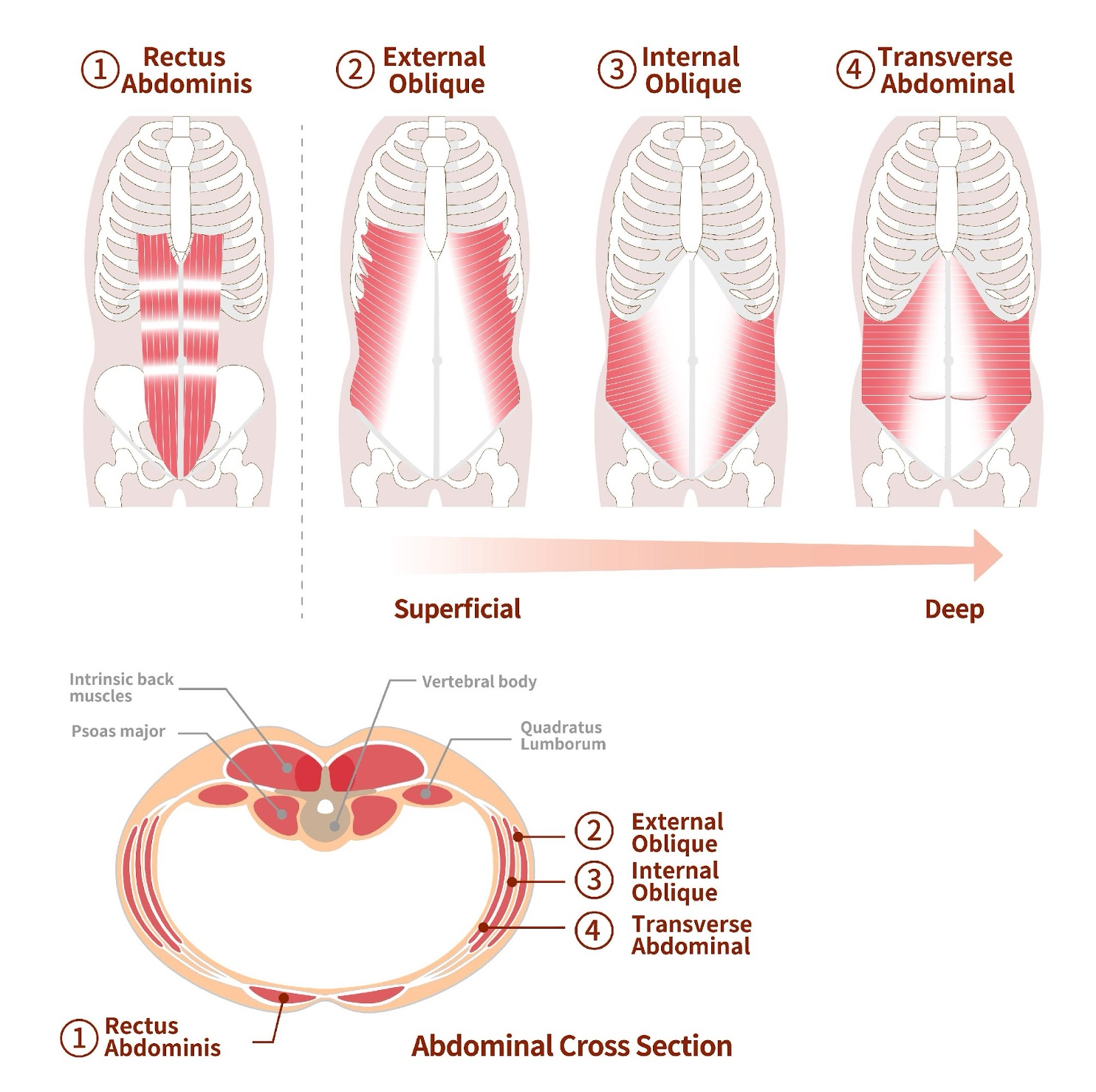

Let’s talk about the abdominal muscles (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Abdominal muscles. (Click here to enlarge this image.)

The most superficial layer is the rectus abdominis, commonly known as the “six-pack” muscle. Beneath that, we have the external obliques, which run diagonally from the ribs down to the pelvis. A helpful way to visualize the direction of the external oblique fibers is to imagine sliding your hands into your front pockets—the angle they follow. Below the external obliques are the internal obliques, which run in the opposite direction. Finally, the deepest layer is the transverse abdominis, which acts like a corset, providing stability and support to the core and internal organs.

All these layers—external obliques, internal obliques, and transverse abdominis—come together in a connective tissue sheath. This sheath wraps around the rectus abdominis muscles, and in the center of these muscles lies the linea alba, the midline connective tissue that runs vertically along the abdomen.

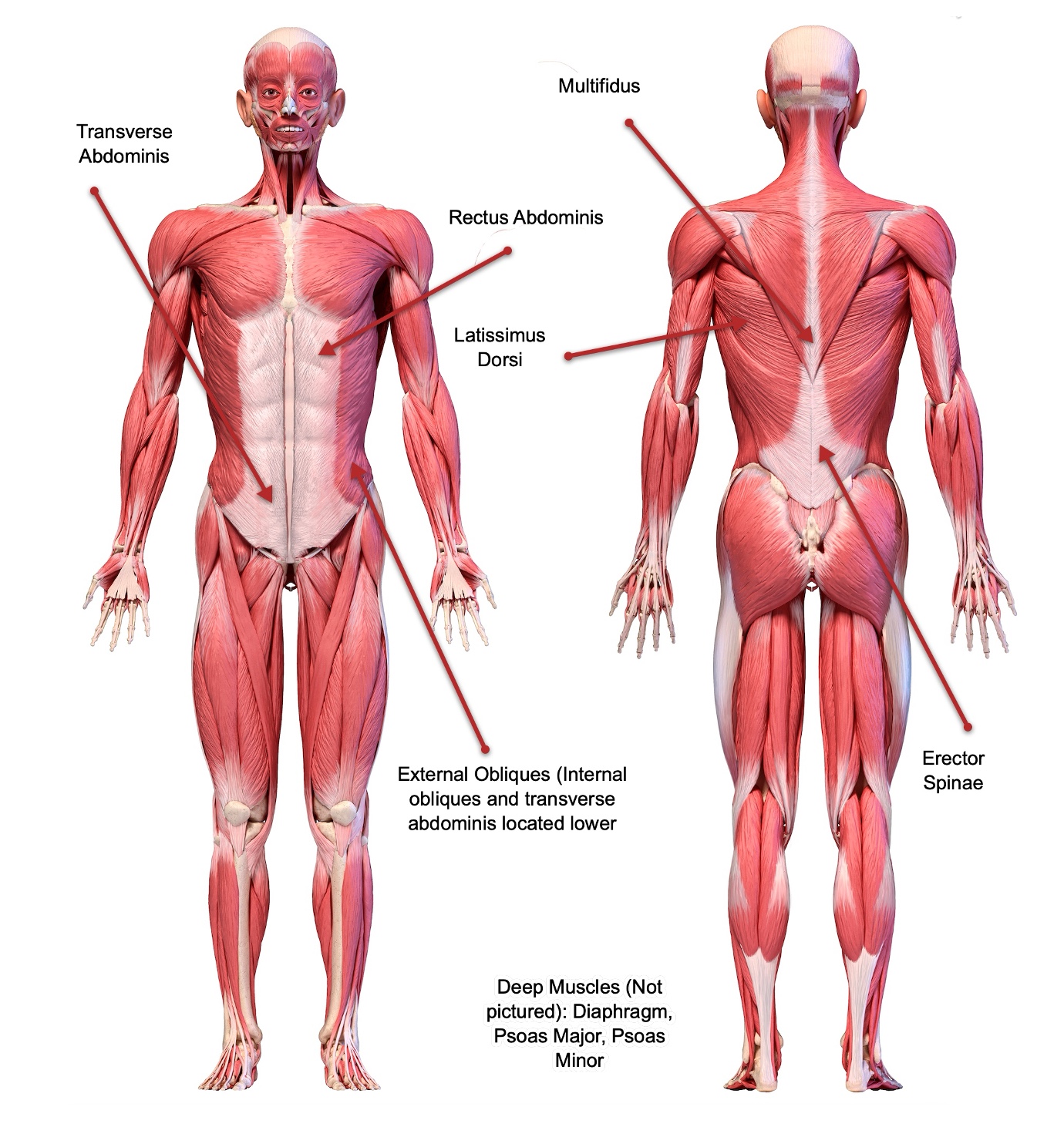

But the core doesn’t stop with the abdominal muscles. It also includes muscles along the back, such as the erector spinae and multifidus, the diaphragm, psoas major and minor, and the iliacus (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Anatomical images of both the front and back of core musculature. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

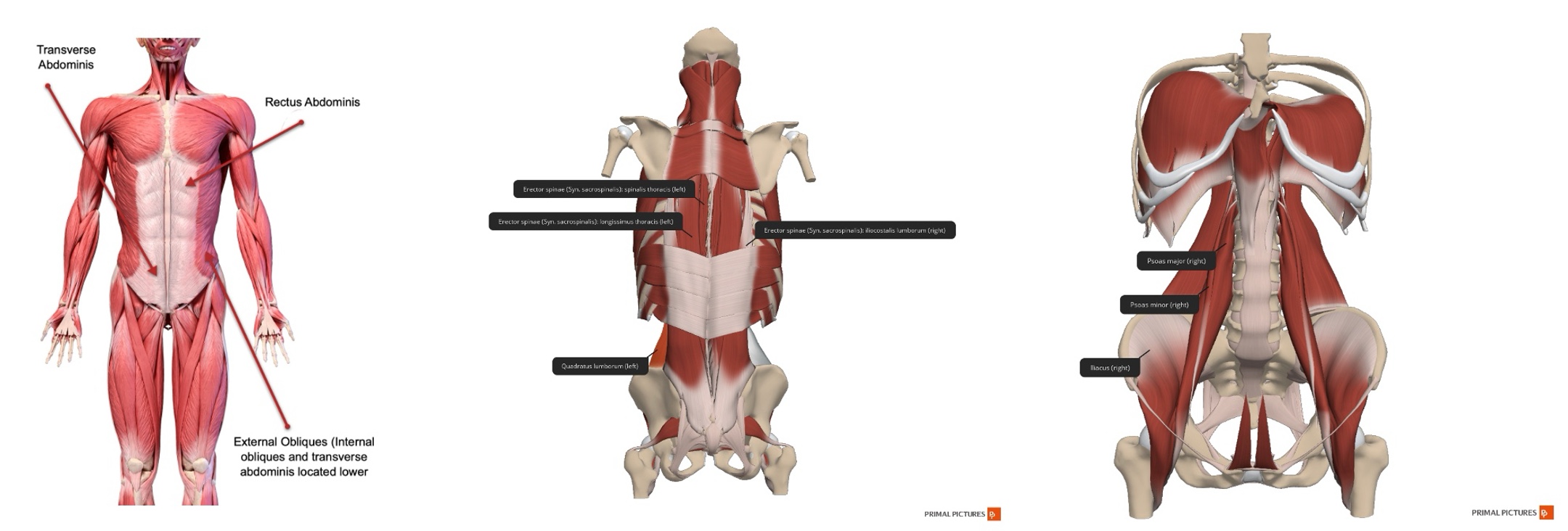

Together, these muscles form a dynamic system that provides stability and mobility. Without this muscular framework, our skeleton would lack structure and support, leading to dysfunction. Let’s look at some of these deeper muscles in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Deeper muscles of the core. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

The psoas major and minor, along with the iliacus, are particularly significant because they are the only muscles that cross from the trunk to the lower extremities, attaching to the femur. This connection is critical in understanding how core stability impacts pelvic health. Dysfunction in these muscles can contribute to various issues related to the pelvis. Figure 4 spotlights the transverse abdominis because of its unique role in core stability.

Figure 4. Transverse abdominus. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

This muscle is often compared to a corset, as it encircles the abdomen and “holds everything in.” It is the top line of defense for maintaining core integrity and protecting the organs beneath it. However, during pregnancy, the transverse abdominis often becomes disrupted, leading to potential dysfunction. We’ll discuss this disruption in more detail tomorrow and touch on it briefly in some upcoming slides.

This overview should show you how these structures work together and set the stage for our deeper exploration of pelvic health. Remember, you’ll have access to all the slides afterward, so feel free to review them in more detail as needed. Let’s move forward with a deeper understanding of how the core and pelvic floor are intertwined.

Pressure Regulators

Next, we have the pressure regulators: the diaphragm and pelvic floor. These two structures need to work in concert to maintain proper function. To visualize the diaphragm, think of a jellyfish. As you breathe out, the top of the jellyfish lifts, mimicking the diaphragm's upward motion. You can try it yourself—breathe in, then breathe out. As you exhale, imagine the jellyfish lifting upward.

When you breathe in, the top of the jellyfish flattens, corresponding with the diaphragm’s movement downward. The pelvic floor, on the other hand, can be imagined as an upside-down umbrella. When the umbrella opens, it holds things securely inside. As you exhale and the jellyfish lifts, the pelvic floor also lifts. When you inhale, the jellyfish flattens, and the pelvic floor relaxes. This tandem movement is essential for maintaining harmony in the body.

Issues often arise if the diaphragm and pelvic floor are not functioning together. For example, a poorly functioning pelvic floor can lead to incontinence, pelvic pain, or other related problems. Similarly, if the diaphragm or rib cage isn’t moving adequately, it can cause shallow breathing and tension, affecting the pelvic floor muscles and increasing tension and discomfort. This interplay shows how vital it is for these systems to work cohesively.

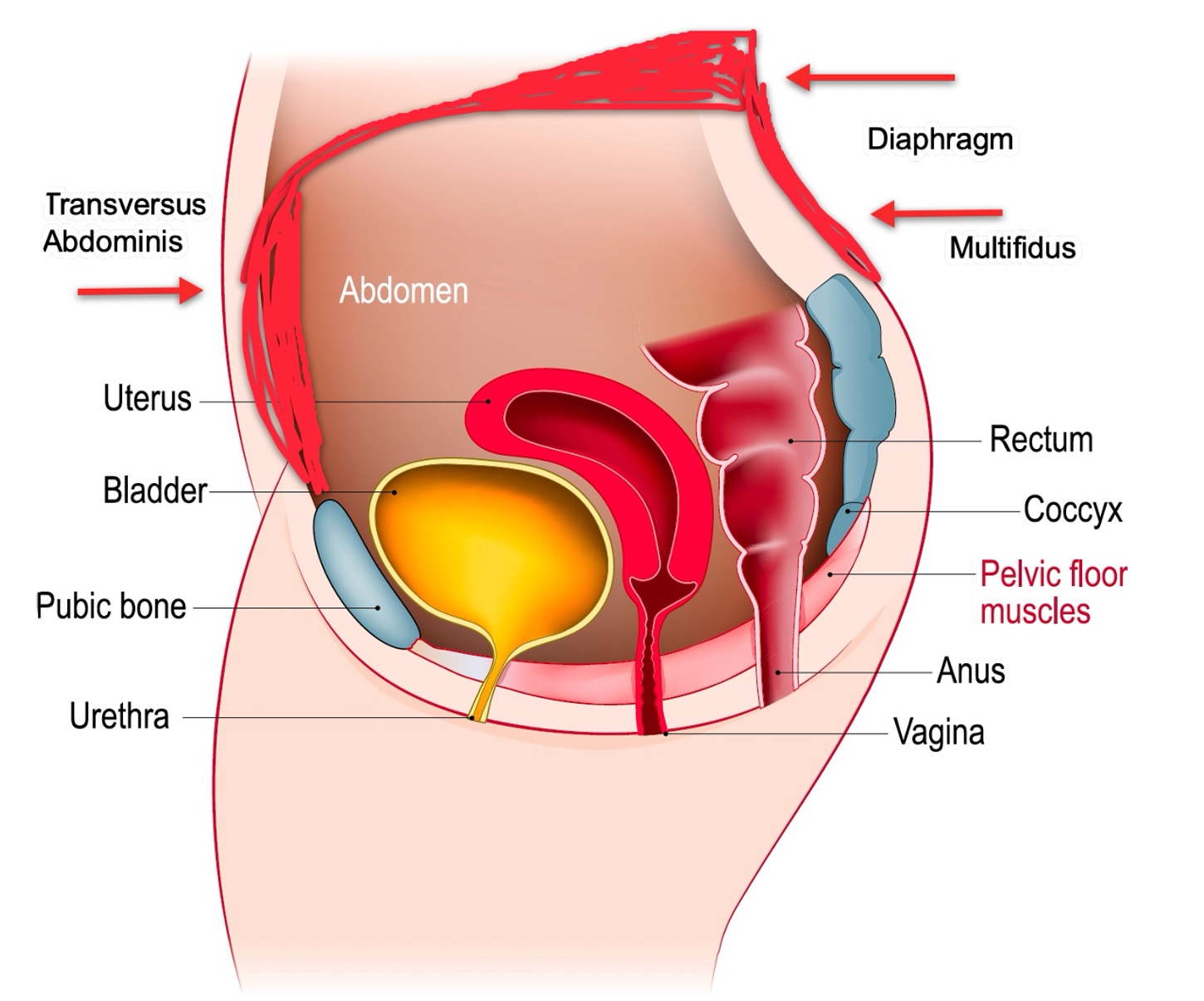

The next slide (Figure 5) illustrates this relationship.

Figure 5. The core and pelvic floor are pressure regulators. (Click here to enlarge this image.)

The diaphragm sits at the top of the core, and as pressure changes in the chest during breathing, it impacts pressure in the pelvic region below. This connection directly affects the pelvis. You’ll also notice in the diagram the positioning of the uterus, which is nestled between the bladder and intestines, further highlighting the interconnectedness of these structures.

As we move forward, we’ll explore these concepts in greater depth, but I hope this quick overview gives you a foundational understanding of how the diaphragm and pelvic floor work together to regulate pressure and maintain pelvic health.

Pelvic Floor

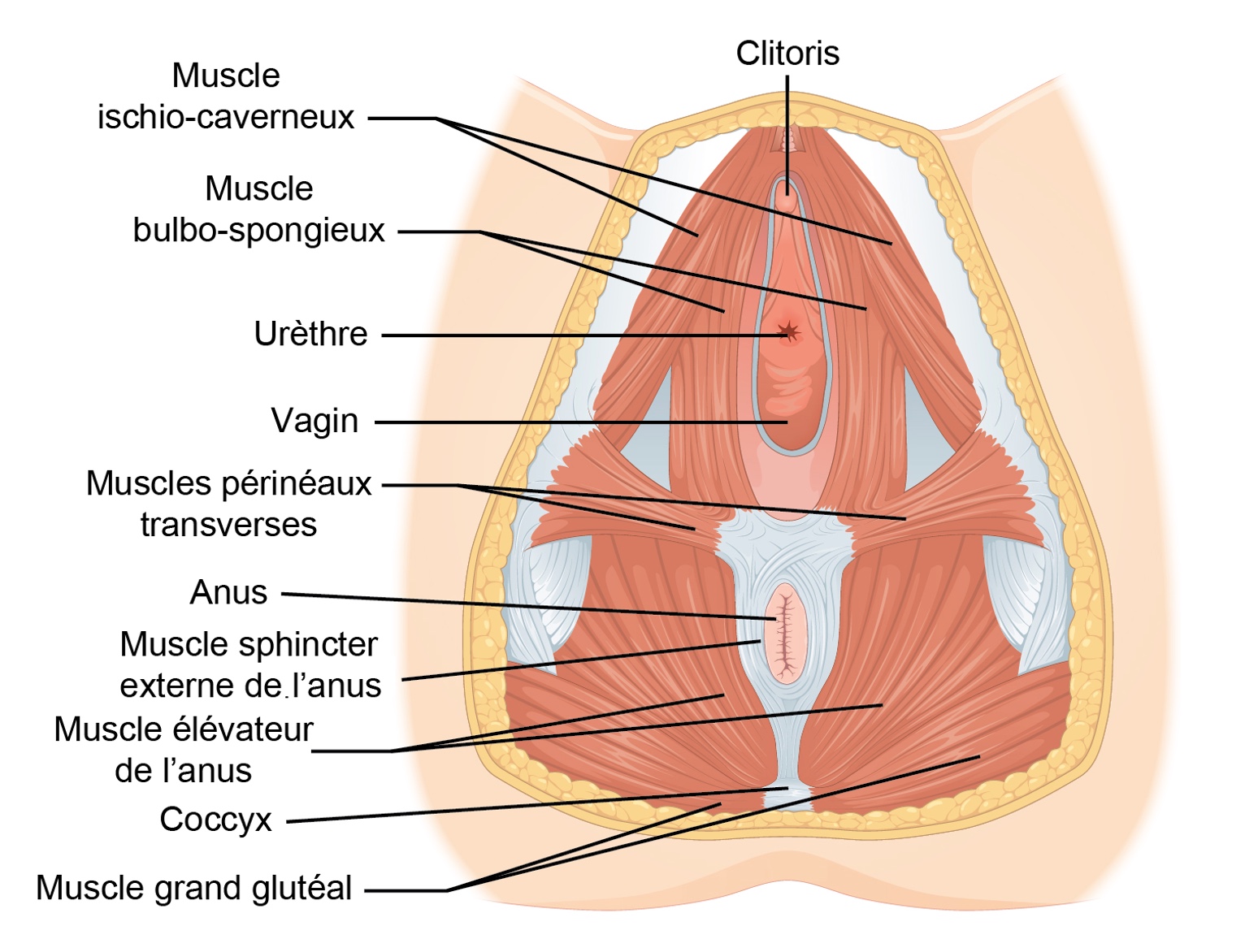

Now, let’s take a closer look at the pelvic floor. While I won’t detail every muscle involved, you can see from the images that the pelvic floor comprises numerous muscles running in various directions, with fibers oriented to support different functions (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Pelvic floor anatomy. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

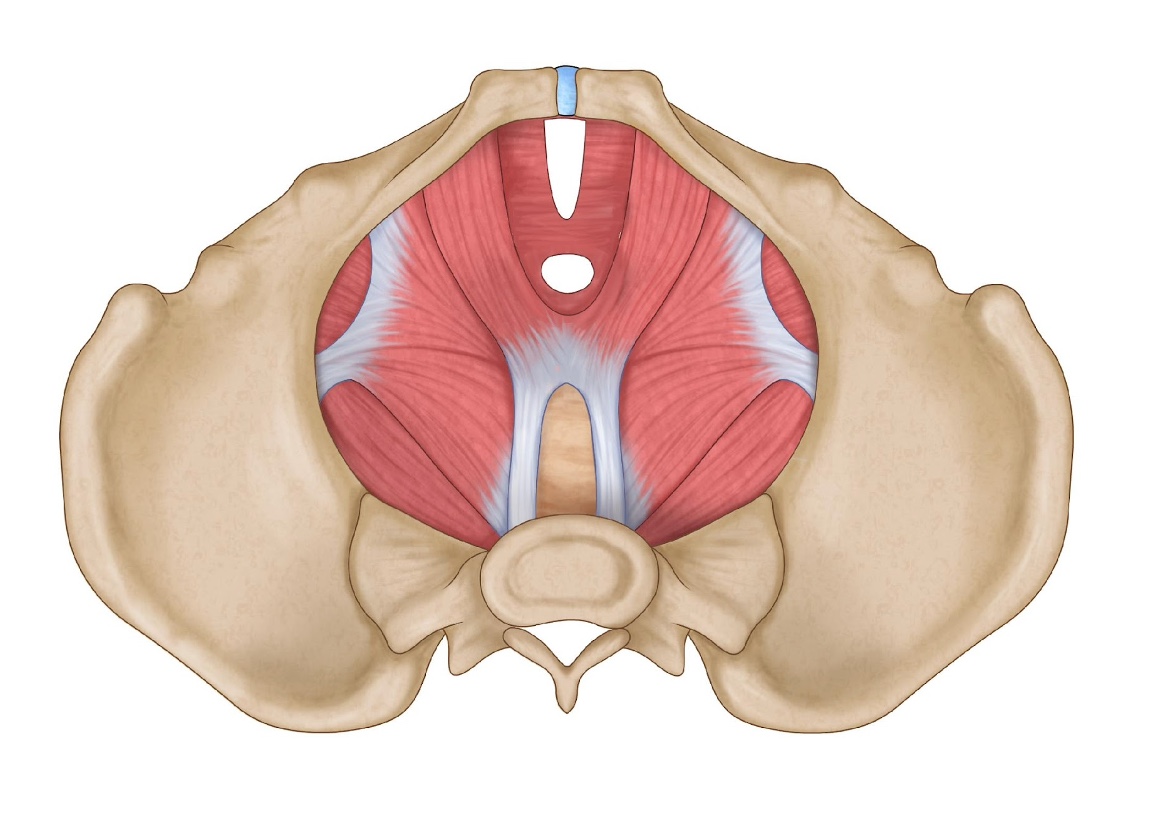

These muscles work together to fulfill what we often refer to as the pelvic floor's "three S's": support, sphincter, and sex. These overarching roles provide a helpful framework for understanding its significance. To orient you to the anatomy further in Figure 7, the front of the pelvic floor corresponds to the pubic bone, while the back aligns with the coccyx.

Figure 7. Pelvic floor muscles within the pubic bone.

Imagine this view as if you were looking at the pelvis from below, with the person’s legs open, offering a downward perspective. This vantage point also allows us to see how the muscles form a tent-like structure or an upside-down umbrella, providing critical support to the pelvic organs.

At the front, you’ll notice the pubic symphysis, a cartilage structure rather than bone. This flexibility is crucial during childbirth, allowing the pelvis to expand and accommodate the baby. However, this same flexibility can sometimes lead to shifts or instability in the pelvic floor muscles, potentially resulting in later dysfunction.

You’ll also observe the iliacus muscle and the sacroiliac (SI) joints on either side of the pelvis. These connections are a reminder that the pelvic floor doesn’t operate in isolation—everything in the body is interconnected. For example, a dysfunction or imbalance in one area, such as the iliacus or SI joint, can alter the positioning of the pelvis. This shift can subsequently affect the pelvic floor muscles and lead to various issues, including pain, weakness, or incontinence.

Understanding this intricate system helps us appreciate how the pelvic floor interacts with the rest of the body, emphasizing the importance of addressing it as part of a holistic approach to postnatal health.

Why Are the Core and the Pelvic Floor Important?

Why is the pelvic floor so important? It plays a crucial role in providing stability, structure, and support to the body. It serves as a protective barrier for our internal organs, ensuring they remain securely in place. The pelvic floor also helps prevent incontinence by controlling our sphincters, maintaining proper function, and supporting our ability to manage bodily waste.

In addition to these vital roles, the pelvic floor is essential for other bodily functions, including sexual health. Its proper function contributes to physical comfort, intimacy, and overall well-being, highlighting the importance of maintaining its health and addressing any dysfunctions that may arise.

What is Pelvic Health Therapy?

What is pelvic health therapy? At its core, pelvic health therapy is the assessment and treatment of pelvic floor dysfunctions or disorders. It addresses a wide range of issues that can affect individuals across the lifespan—from birth through older adulthood. Pelvic health therapy is a growing specialty within occupational therapy and other healthcare fields, offering targeted interventions for various conditions.

Let’s start with some common pelvic floor dysfunctions to provide a quick overview. Urinary incontinence is one of the most well-known and can present in different forms. Stress incontinence, for example, occurs during physical activity, such as jumping or running, and can lead to leaking. In my experience running CrossFit classes, this is why many women would head to the bathroom before starting exercises like jumping rope. While this is common, it is not normal and should not be accepted as an inevitable consequence of childbirth or activity. Similarly, urgency incontinence involves a strong, sudden urge to urinate, often triggered by certain situations, like walking through the door at home. Many women experience mixed incontinence, which combines both stress and urgency components.

Other pelvic floor issues include fecal incontinence and chronic constipation, which can significantly impact daily life. Diastasis recti, a separation of the abdominal muscles, is another condition often associated with pregnancy and postpartum recovery. We’ll explore this further in our upcoming case studies. Pelvic organ prolapse is where one or more pelvic organs—such as the bladder, uterus, rectum, or intestines—descend or bulge due to weakened muscles and can cause pain, discomfort, or a sense of heaviness. While this topic could warrant an entire discussion, it’s another key area of focus in pelvic health therapy.

Beyond these conditions, pelvic health therapy also addresses issues related to menopause, such as dry vaginal tissue or recovery from injuries like a broken tailbone. Post-surgical recovery, such as after bladder or prostate cancer treatments, can also lead to pelvic floor dysfunction requiring intervention.

Pelvic health therapists employ specialized assessments and treatments to address these challenges. This therapy is not limited to a specific age group—practitioners can work with infants, children, adults, and older adults. For example, pediatric pelvic health therapy focuses on conditions like bedwetting or constipation, while therapy for older adults might address incontinence or pelvic pain related to age-related changes.

Ultimately, pelvic health therapy aims to restore function and improve quality of life by addressing the underlying issues within the pelvic floor. It’s a field that highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach, with occupational therapists uniquely positioned to contribute through their holistic understanding of function and daily living.

Why OT?

Why OT? My response is, why not OT? This practice area aligns naturally with our profession's foundational principles and skills. When evaluating whether a specific area falls within the scope of occupational therapy, I always return to the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF), 4th Edition.

According to the OTPF, occupational therapy practitioners are uniquely trained to evaluate across multiple domains: occupations, context, performance patterns, performance skills, and client factors. These evaluations are carried out using the occupational therapy process, which includes assessment, intervention, and measurement of outcomes. Our work spans individuals, groups, and populations, making us adaptable to diverse needs.

Pelvic floor dysfunctions fit seamlessly within these frameworks. They align directly with the OTPF’s domain of body structures and functions under client factors. Additionally, these dysfunctions often impact performance skills, making them integral to our scope of practice. Occupational therapy practitioners assess clients' strengths and limitations to develop interventions tailored to their specific goals, needs, and desired outcomes. This client-centered, holistic approach makes OT so well-suited to pelvic health.

To further reinforce this connection, the OTPF defines occupational therapy as the therapeutic use of everyday occupations with individuals, groups, and populations to enhance or enable participation. This core principle is vital in pelvic health therapy, as the focus is often on helping clients regain or maintain their ability to participate fully in daily activities.

Moreover, the OTPF emphasizes that occupational therapy services encompass habilitation, rehabilitation, and health and wellness promotion for clients, whether they have disabilities or not. This broad focus highlights our role in addressing pelvic health challenges across a spectrum of needs, from prevention and maintenance to recovery and adaptation.

Throughout this week, you’ll hear repeatedly how occupational therapy fits into this practice area. Our training, perspective, and focus on enhancing participation in meaningful activities make us exceptionally well-equipped to address pelvic health and pelvic floor dysfunction. This area of practice not only aligns with our professional scope but also exemplifies our unique contributions to improving the quality of life for clients.

Effects of Pregnancy

I also want to highlight some relevant areas where occupational therapy plays a crucial role in supporting women experiencing pelvic health challenges. These include conditions like diastasis recti, incontinence, organ prolapse, pain during urination, bowel movements, or intercourse, as well as pain during exercise and daily activities. Each of these issues impacts a woman’s ability to participate in meaningful activities, which is at the core of our practice as OTPs.

To frame this discussion, I’ve included definitions of quality of life from the AOTA and the World Health Organization. While I won’t read them in full to save time, it’s important to recognize that these definitions align closely with the impacts of pelvic floor dysfunction on physical, emotional, and social well-being.

Let me share some insights from recent research. One study by Molina et al. in 2023 interviewed nearly 1,500 postnatal women and found a strong association between pelvic floor disorders and reduced quality of life. The emotional component of quality of life scored the lowest, highlighting how these disorders profoundly affect women’s emotional well-being. The researchers used tools such as the SF-12 for quality of life, the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory, and additional measures to assess prolapse and urinary symptoms.

Another study by Katina in 2024 explored the impact of pelvic health dysfunction on body image in postnatal women. Conditions like urinary incontinence, constipation, and symptoms of prolapse were found to significantly affect how women perceive their bodies, adding another layer to the emotional and psychological toll of these issues.

Some of the effects of pregnancy on pelvic health are striking. Up to 60 percent of women experience diastasis recti and between 32 and 56 percent report urinary incontinence either during or within a year after childbirth. In the Molina study, nearly 93 percent of the 208 women surveyed reported experiencing one or more symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction between 28 and 32 weeks of pregnancy, with 73.6 percent continuing to report symptoms one year postpartum.

Additionally, a recent study by Burkhart, published in OTJR, revealed that almost 67 percent of women are unaware of pelvic floor rehabilitation as an option. This lack of awareness is significant, as many of these women reported symptoms that directly limit their occupational performance, particularly in sexual activity and exercise.

These statistics emphasize the broad and lasting impact of pelvic health issues on women’s lives, highlighting the need for education, intervention, and support. Occupational therapy is well-positioned to address these challenges by improving awareness and providing meaningful, client-centered care to enhance quality of life.

Case Study: Cautionary Tale

Here is a case study that I consider a cautionary tale—because it’s my own story. I am a 40-year-old woman, six years postpartum from my last of three pregnancies. My children’s birth weights ranged between 6 pounds 9 ounces and 7 pounds 11 ounces—not unusually large babies. However, I was dealing with a significant diastasis recti, measuring over four fingers in width, along with an umbilical hernia.

At the time, I was recently divorced and adjusting to being the primary caregiver for my three children, then ages 6, 9, and 12. I had also just started a new job as a pediatric OT faculty member. On top of all this, I was an avid runner and triathlete, regularly running 25 to 35 miles a week, and had completed my first half marathon just before my 40th birthday.

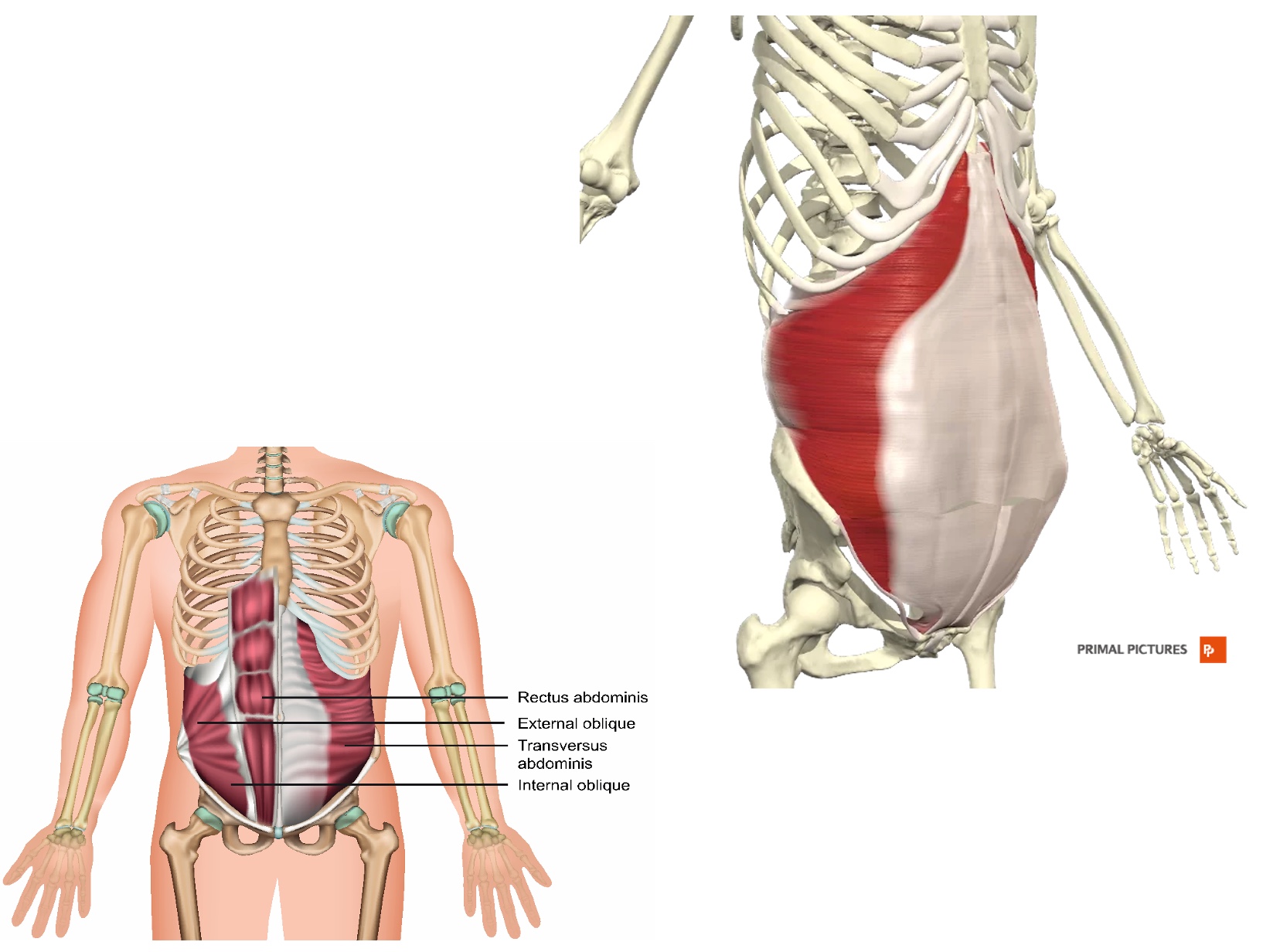

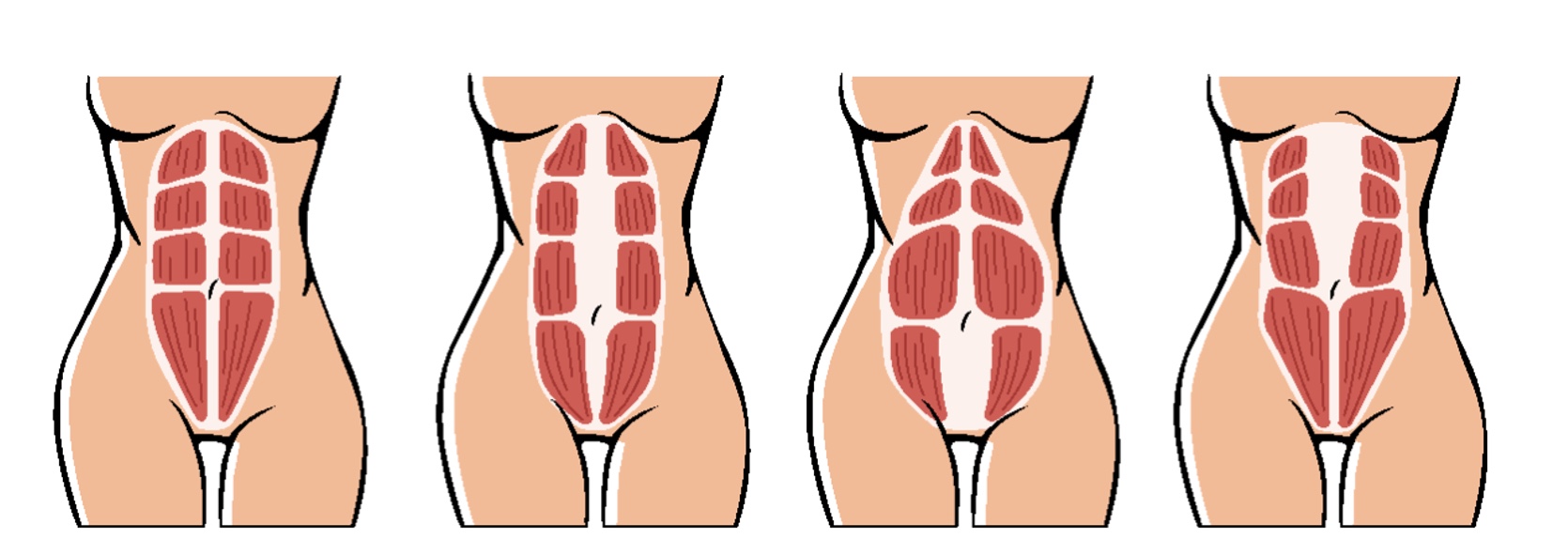

My diastasis recti was severe—a separation larger than a fist—and it spanned the entire width of my abdomen, causing the umbilical hernia. Examples of diastasis recti are in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Examples of diastasis recti.

I sought treatment from a board-certified surgeon in general and plastic surgery. During my consultation, he recommended repairing the hernia and the diastasis recti. He explained the procedure would involve stitching my abdominal muscles from my ribs to my pelvis and assured me the resulting scar would be minimal and concealed beneath my bikini line.

Unfortunately, the reality was far from what I had anticipated. Less than a month after surgery, I began experiencing severe complications. My surgical site developed open wounds that leaked yellow fluid constantly. Every night, my abdomen would swell with fluid, and every morning, it would flatten out again. I used maxi pads as makeshift bandages to manage the drainage while working. Despite these alarming symptoms and recurring fevers, my surgeon dismissed my concerns, claiming everything was healing well.

It wasn’t until my fever spiked to 104.3 degrees that I realized how serious the situation was. When I contacted the surgeon’s office, they brushed me off, suggesting I had an upper respiratory infection. I ended up at my family doctor’s office, where I was diagnosed with sepsis. Cultures revealed I had an MRSA infection, and my white blood cell count had climbed to 43,000. I spent nearly two weeks in the hospital on IV antibiotics and was sent home with oral antibiotics, yet my wounds still wouldn’t heal.

Frustrated and desperate, I sought a second opinion from a specialist outside my area. This surgeon removed the infection, revised my scar, and used proper sutures. While the new scar was larger, it healed much better. However, I continued to experience recurring infections from sutures left behind by the original surgeon, each time culturing as MRSA. Over time, additional surgeries were required to remove the infected sutures and address complications, including one instance where the infection compromised my linea alba.

Looking back, I can see how my fitness routine at the time was making things worse. My workouts were centered around sagittal plane activities—running, cycling, swimming, and sit-ups—all of which exacerbated my diastasis recti. Sit-ups and crunches, in particular, were the worst exercises for my condition, as they pulled my abdominal muscles further apart. I truly needed exercises that targeted the transverse abdominis, the deepest layer of abdominal muscles, to strengthen my core and improve pelvic floor control.

I also realized that my lifelong rib flaring and increased lordosis had contributed to my diastasis recti. As a child, I had chronic reflux and recurrent pneumonia, which caused me to adopt postural patterns that increased the strain on my abdominal muscles. These factors, combined with my postpartum activities, created the perfect storm for pelvic and core dysfunction.

This experience is what ultimately led me to specialize in postnatal care. I realized how vital education and early intervention are for women like me. If someone had taught me how to work outside the sagittal plane and protect my core and pelvic floor after childbirth, I could have avoided many of these challenges. My journey has been long and difficult, but it has given me the passion and purpose to help other women navigate their postnatal recovery with the education and support I didn’t have. This is why I do what I do—so others can avoid the struggles I endured and regain their strength, function, and confidence.

Case Study: Success Story

I’d like to share a success story from my practice. This client is a 27-year-old woman postpartum with her third child. She has three children under five, with birth weights ranging from 6 pounds 2 ounces to 7 pounds 8 ounces. At our initial evaluation, 15 days postpartum, she had a diastasis recti measuring less than three fingers and reported several physical and emotional challenges.

Some of her client factors provide important context. She is newly married and the primary caregiver for her three children, ages three, four, and five. Her husband, a firefighter, works 24-hour shifts, leaving her to manage the household alone much of the time. She is pursuing a nursing degree with a background in exercise science. She has a history of postpartum depression and anxiety, and her previous hobbies included CrossFit and weightlifting, which she hoped to resume eventually.

During our initial session, I assessed her diastasis recti and evaluated her home environment, observing her couch, bedroom, and bathroom setup to identify ways to reduce strain during daily activities. She was exclusively breastfeeding and recovering from a first-degree tear and perineal hematoma, both resulting from a vacuum-assisted delivery. During this session, I focused on education—teaching her proper positioning for feeding, getting out of bed with less strain, and strategies for managing her recovery. I also administered the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and the Perinatal Anxiety Screening Scale (PASS), which indicated a high likelihood of postpartum depression and mild to moderate anxiety symptoms.

At our three-month follow-up, her tear and hematoma had resolved, and she was continuing to breastfeed while introducing bottle-feeding for daycare. She reported mixed incontinence with a self-rated severity of 6 out of 10 and a daily activity impact of 5 out of 10. Her diastasis recti remained under three fingers. During this session, I introduced targeted exercises to strengthen her core and pelvic floor, such as elbow planks with posterior tilt, glute bridges with feet elevated, and wall squats with adductor squeezes. These exercises were designed to help her engage her transverse abdominis and pelvic floor muscles more effectively, addressing her quad dominance and improving overall stability. Exercises can be viewed on the links found in the handout.

Six months postpartum, she returned to her nursing program and continued breastfeeding while managing daycare feedings. She reported some progress, with reduced incontinence severity but new symptoms of intermittent constipation. Her anxiety and stress remained elevated, likely due to the challenges of balancing school, parenting, and recovery. At this point, she opted to begin weekly training sessions with me. These sessions included light cardio, pelvic health exercises, and a gradual reintroduction to weightlifting. I provided extensive education on techniques like the Valsalva maneuver and the use of weight belts, explaining their potential risks for postpartum women with weakened pelvic floors. We also discussed nutritional strategies to address her constipation and support her recovery.

By her nine-month follow-up, she had made significant progress. Her diastasis recti had reduced to less than two fingers, and her incontinence severity had decreased further. While her anxiety remained mildly elevated, her depression and stress scores were within normal ranges. She was feeling much better overall and reported enjoying her time with her children while continuing to progress in her recovery.

At the one-year mark, her progress continued. She experienced minimal stress incontinence, primarily during gym activities, but felt it was manageable. Her diastasis recti remained stable, and her postpartum depression and stress scores were below the clinical threshold. While her anxiety persisted at a mild to moderate level, she felt it was consistent with her typical baseline. At this stage, we transitioned to as-needed check-ins, allowing her to maintain her progress independently. Her story underscores the importance of personalized, holistic care in supporting women through postpartum challenges, and it’s been a privilege to be part of her journey.

Summary

Now, we’ll move on to an interactive exam poll to assess what we’ve covered.

Exam Poll

1) Which is NOT a stressor reported by postnatal women?

Great, it looks like most of you got this one right! New moms don’t typically report Increased time and boredom—quite the opposite, as anyone with a newborn knows.

2)Why are the core and the pelvic floor important?

Well done! Most of you selected the correct answer, which is D—"all of the above." The core and pelvic floor play multiple critical roles, including providing stability and protection and preventing incontinence.

3)What is an example of pelvic floor dysfunction?

That’s correct—the answer is D, all of the above. While we didn’t go into detail about pelvic perineal pain syndrome today, it’s another important condition that often arises when the pelvis and pelvic girdle lack stability.

4)Which of the following is NOT a reason why occupational therapy is an important part of treating pelvic health?

Great job! The correct answer is C. While occupational therapists can assess and treat pelvic floor dysfunction, we cannot diagnose medical conditions or prescribe medications.

5)What percentage of people continue to report pelvic floor dysfunction 1 year postpartum?

This one had more variation, but the correct answer is C—73%. This was mentioned on the slide with the statistics about postnatal pelvic floor dysfunction.

Overall, great work on the poll! I’ve also provided my references in a supplemental handout so you can access all the studies and data I mentioned during the session.

Thank you all for being here today. I hope you found today’s presentation informative and engaging.

Questions and Answers

Does the weight of the baby have an impact on postpartum deficits?

Yes, the baby's weight can impact the mother's health. Studies show that women with larger babies are more likely to experience pelvic floor dysfunction and may have a higher risk of developing pelvic organ prolapse in the future. Additionally, the baby’s position during pregnancy can contribute to challenges. For instance, a baby sitting low or in an unusual position can lead to increased difficulties during pregnancy and postpartum.

Does the number of pregnancies affect pelvic health?

Yes, with each pregnancy, the risk of pelvic floor dysfunction increases. Research shows that the cumulative impact of multiple pregnancies can heighten the likelihood of pelvic health issues.

Are there differences in how OT supports breastfeeding versus formula-feeding mothers in pelvic health?

No, the approach to pelvic health therapy remains the same for both breastfeeding and formula-feeding mothers. The interventions and support are tailored to the individual’s needs rather than their feeding choice.

How do you measure diastasis recti?

To measure diastasis recti, the client lies on their back. Start below the ribs and above the belly button, feeling along the linea alba. If it’s hard to locate, you can have the client perform a small crunch, which makes the separation more noticeable. Using your fingers, determine how many can fit between the separation. Repeat this process below the belly button to assess if the separation is localized or spans multiple areas.

What scales do you use for postpartum depression and anxiety?

I use the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and the Perinatal Anxiety Screening Scale (PASS). Both are freely available online. The EPDS is particularly effective for identifying postpartum depression, while the PASS evaluates perinatal anxiety levels.

Can pelvic floor dysfunction be addressed years after a C-section?

Yes, it is possible to work on pelvic floor dysfunction years after a C-section. This is an area many pelvic health specialists focus on, and even long-term issues can often be improved with appropriate intervention. If this applies to you, I recommend attending future sessions this week for more in-depth guidance.

What training and certifications do you recommend for pelvic health professionals?

My training started in pediatrics, where I learned breathing and core techniques through Mary Massery’s work, which spans the lifespan. I also completed Girls Gone Strong’s pre- and postnatal course, open to therapists and personal trainers. Another excellent resource is Core Exercise Solutions by Sarah Duvall. Additionally, the AOTA has a Pelvic Health Community of Practice, and Lindsey’s upcoming pelvic health conference is another valuable opportunity.

Is it normal to experience mild prolapse symptoms years after birth?

It’s not normal, though it is somewhat common. If prolapse symptoms persist, a pelvic health therapist should evaluate them to address the underlying issues.

Does the degree of tearing during delivery impact pelvic health?

Yes, the severity of a tear can significantly affect the pelvic floor. Larger tears often result in more damage to the muscles, and scar tissue can further complicate recovery. Evaluating and addressing scar tissue is an important part of pelvic health therapy.

Who typically refers women to your practice?

I receive referrals from my community's OB-GYNs, general practitioners, and pediatricians. These relationships have been built over years of collaboration. Grants and donations fund my services so clients don’t incur costs for my care.

Are planks safe for individuals with diastasis recti?

Yes, planks can be safe if done correctly. Proper positioning and alignment are key, especially ensuring the pelvis and ribs are aligned without excessive strain. The severity of the diastasis recti should also be considered when deciding whether planks are an appropriate exercise.

Do you accept insurance?

I don’t accept insurance, as my services are grant-funded. However, other pelvic health specialists may accept insurance, so I recommend asking about this during future sessions.

Do you perform internal exams?

A: No, I do not perform internal exams. My focus is broader, and I work with both the mother and infant during sessions. I refer clients to local pelvic health specialists with the appropriate equipment and expertise for detailed internal evaluations.

References

Please refer to the separate handout.

Citation

McHugh-Conlin, J. (2024). Overview and importance of pelvic health: Postnatal pelvic health virtual conference. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5758. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com