Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Palliative Care And Occupational Therapy: Our Unique Role, presented by Heather Javaherian, OTD, OTR/L.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- As a result of this course, participants will be able to identify and define the practice area of palliative care.

- As a result of this course, participants will be able to recognize the unique role of occupational therapy in palliative care.

- As a result of this course, participants will be able to list the evidence of occupational therapy in palliative care.

Introduction

I am very glad to be here. Let's get started with the facts about palliative care.

Facts

Annually, 56.8 million people need palliative care worldwide. However, only 14% who need it get it. In the United States alone, 6 million people could benefit from palliative care, so there's a lot of need.

What is Palliative Care?

What is palliative care? It's a medical specialty established in 1967 to address patients' physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs as they face a serious and chronic disease or condition.

One exciting aspect of palliative care is that it's founded on an interprofessional approach. Its team includes a physician, social worker, nurse, and often a chaplain. I also believe that occupational therapy should always be part of that team. Hopefully, when you leave this session, you will have a foundation for advocating for occupational therapy's role in palliative care.

Palliative Care

Palliative care focuses on physical and emotional relief for the patients. It encourages strong patient and physician communication and promotes collaborative decision-making. Your palliative care physician will be that one person who sees all facets of care. They sit down with their patients and family members to discuss pain management, quality of life, and what's working and not working. They coordinate the big picture for that patient to connect the healthcare system silos that exist. Palliative care also provides curative treatments. Someone can be on palliative care and receive chemotherapy or other curative procedures to help fight that disease or condition. Palliative care coordinates continuity of care across various settings. The team can work with a patient in the hospital, at home, or in hospice. Palliative care identifies the goals of the individual or the family and provides options for working with a patient to move forward. Think about the patients that you work with and the challenges they face. They often have serious healthcare decisions to make. A palliative doctor can help them review their options and move forward with that meaningful plan. Many argue that palliative care should be initiated at the time the serious or life-threatening condition has been diagnosed or when life-prolonging therapies are introduced. For example, palliative care would be when congestive heart failure or cancer is first diagnosed. This is a little different approach than we normally see.

Who is Seen in Palliative Care?

Palliative care is for patients who have serious illnesses, life-threatening illnesses, and then also patients who have various comorbidities. These conditions may involve cancer, cardiac conditions, COPD, dementia, chronic liver disease, Parkinson's disease, rheumatoid arthritis with its systemic impacts, and stroke. It can cover a wide variety of conditions. I think often we think of cancer, but it's anyone who has that serious, life-threatening, or chronic disease.

Palliative Care Vs. Hospice

Many people think hospice with they think palliative care. It's important to remember that not all palliative care patients are in hospice. Palliative care can still involve curative treatments and working on increasing independence. The clients want to get better. Hospice is a subset of palliative care. So typically, when someone's put into hospice, they have six months or less to live at this time. And when they go into hospice, all curative treatments are stopped. Now the focus is really on quality of life. There is a focus and emphasis on providing our patients with comfort and dignity, supporting the family, and managing their pain. We can also provide the family with respite and bereavement care as they just prepare for the impending loss of their loved ones.

Facing Serious Illness and End of Life

Here is a 1996 study by the Gallup Survey; I know it's a bit old, but it provides some great information. They found that nine in ten adults prefer to be cared for at home versus hospital or nursing homes. Many of us work in home health environments and understand the importance of a natural context.

Most hospice care is provided in the patient's home. Occupational therapy should be a part of that team going into the patient's home, especially when our clients are facing these serious illnesses and the end of life.

The survey also found that the greatest fears associated with death were "being a burden to family and friends," "pain," and then a "lack of control." Think about these words. As an occupational therapy practitioner, do we not help our patients not to be a burden on their family or friends? For example, in rehab, you may work with your patient on independence in upper body dressing, lower body dressing, or other self-care tasks. You may work with them in a "therapy apartment" on meal planning or other high-level tasks because you want them to be more independent and don't want to be that burden. In palliative care, we can also help our patients to adapt different occupations so they don't have that feeling of being a burden.

Pain management is another concern. The medical team, like the palliative care or hospice physician, can look at pain management from a pharmaceutical standpoint. As occupational therapy practitioners, we can look at nonpharmaceutical ways to address pain and help them have meaning during this important time.

A lack of control exists when you don't feel well. It can feel overwhelming. How can we use occupations, our golden nugget, to get that patient to feel like they have control over their day, their decisions, and their interactions with their loved ones?

Finally, most adults said they would be interested in a comprehensive home hospice program. Yet, most Americans know little or nothing about their eligibility or the availability of hospice. I was one of those adults several years ago who, after months of being with a loved one in a hospital setting with a terminal illness, there was a nurse who suggested, Heather, have you thought about palliative care in hospice? They provided a lot of education on both palliative care and hospice. In hindsight, I so wish that someone had introduced us to the palliative care team on that day that we were given that serious terminal diagnosis, as that might have changed our journey.

People Who Are on Palliative Care Are at a Higher Risk For:

Individuals receiving palliative care are at an elevated risk for various conditions and challenges that significantly impact their functional performance and quality of life. The physical and emotional toll of their illness often makes it difficult for them to engage in daily activities and participate in meaningful occupations.

For example, those with cancer may experience cancer-related fatigue, leading to exhaustion and an inability to perform routine tasks. The physical changes associated with their illness—such as weight loss, hair loss, and altered eating habits—can negatively impact their body image and self-esteem.

Pain management is another significant challenge, often accompanied by decreased strength and limited range of motion. These issues can exacerbate fatigue and diminish their overall functional capacity. Additionally, these patients may face a heightened risk of falls, further complicating their health and potentially leading to hospital readmissions. This raises concerns about their ability to safely return home and continue living independently.

Cognitive changes are also critical, as the disease process or medications can impair cognitive function, affecting their safety and ability to engage in daily activities. Lymphedema, if present, can further restrict range of motion and mobility, requiring specialized intervention from an occupational therapy practitioner trained in lymphedema management.

Skin integrity is also a crucial concern, particularly for those who are bedridden or have limited mobility. occupational therapy practitioners play a vital role in educating patients and caregivers on maintaining skin integrity to prevent complications like infections, which could lead to severe outcomes. Neuropathy, often resulting from treatments such as chemotherapy, can make daily tasks challenging and increase the risk of injuries, further compromising safety and quality of life.

These multifaceted challenges underscore the importance of a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach in palliative care, with occupational therapy practitioners providing essential support to help patients maintain their quality of life.

What Roles, Routines, and Occupations May Be Impacted?

As occupational therapy practitioners, it is essential to recognize the profound impact that these impairments can have on our clients' daily roles and routines. We must explore how these challenges affect their ability to engage in daily occupations, particularly in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. This involves assessing whether they can perform essential self-care tasks independently, such as bathing, dressing, and grooming, and evaluating their ability to manage more complex activities like cooking, cleaning, and managing finances. For clients with dependents, whether children or pets, it is crucial to consider how they cope with caregiving responsibilities and whether they require additional support.

Health management is another critical area of focus. It's important to determine if the client can manage their health needs independently. Can they take their medications as prescribed, or do they need assistance? For those on specialized treatments like total parenteral nutrition, we must assess who is providing this care and whether the client is involved or capable of managing it on their own. Additionally, exploring their rest and sleep patterns is vital, as illness often disrupts them and can significantly affect overall well-being.

Education, work, and leisure activities may also be affected. While education might not be a priority during this time, for those who are still working, energy conservation strategies and possible workplace modifications may be necessary to maintain employment. For younger clients, play may need to be adapted to accommodate their physical and cognitive limitations, and adults might require modifications to their leisure activities to ensure they can continue participating in enjoyable and meaningful pastimes.

Social participation is critical to assess, as maintaining connections with loved ones can provide essential emotional support during illness. It is important to explore whether the client can meet with friends and family and engage in social activities that are meaningful to them. If they are experiencing barriers to social participation, identifying ways to overcome these challenges is crucial.

A comprehensive evaluation of their performance patterns is necessary to understand how frequently they engage in important activities and how their condition has affected them. Assessing their performance skills, including motor skills, process skills, and social interaction skills, helps identify areas of strength and those that require intervention. Additionally, it is important to consider how client factors, particularly those related to the disease process, influence their abilities and overall occupational performance.

Ultimately, our assessments should be guided by what is most important to the client. By understanding their priorities, we can focus our interventions on helping them achieve the most important goals, thereby enhancing their quality of life during this challenging time.

Case Study: Leisa

Reflecting on Liesa’s situation, it's evident how deeply her role as a mother was integral to her identity and daily life. The challenge of managing her heart condition while striving to fulfill her responsibilities, especially in a physically demanding environment like a two-story condo, called for a nuanced and compassionate approach to therapy. As a home health occupational therapy practitioner, the work with Liesa involved a comprehensive strategy tailored to support her physical and emotional well-being.

In managing her heart condition, techniques like breathing exercises, energy conservation, and pacing were crucial to preventing overexertion and managing her symptoms. Introducing a rollator walker with back support was a practical intervention that allowed her to maintain her cherished routine of walking her children to the bus stop. This was more than just a functional solution—it provided Liesa with a sense of independence and normalcy, offering her a way to stay connected to her role as a mother during a time of overwhelming uncertainty.

The focus on meal preparation and adaptive equipment ensured that Liesa could continue contributing to her household, reinforcing her role as a caregiver despite her physical limitations. Addressing her anxiety was another critical aspect of her care, as emotional distress could easily exacerbate her physical symptoms, creating a cycle that would further hinder her daily functioning. Incorporating mindfulness and relaxation techniques into her therapy likely played a key role in her ability to cope with the emotional weight of her situation.

What truly stands out in Liesa’s case is the vital importance of occupational participation, particularly in palliative care. For Liesa, being able to participate in her children's lives—whether by walking them to the bus stop or attending school functions—was not just a series of tasks but a profound connection to her identity and purpose. The goal of occupational therapy in this context extended beyond merely managing her symptoms; it was about preserving and enhancing her ability to engage in these meaningful activities central to her sense of self. Ensuring that her quality of life was maintained, even as she navigated significant health challenges, was at the heart of the therapeutic process.

What Do Patients Want and Need While on Palliative Care?

Occupational Participation

Von Post and Wagner's scoping review highlights a profound insight: people in palliative care want to maintain their previous occupational patterns. This finding underscores the critical role of occupational therapy in these settings. Occupational therapy practitioners must understand and respect these patterns, focusing on energy conservation strategies that enable clients to stay engaged in their everyday lives. These individuals do not want to be confined solely to the "sick world"; they aspire to continue participating actively in their families, social circles, and communities.

Social participation is a key occupation, and it is vital that we facilitate ways for our clients to remain connected with others. Whether by adapting activities or finding new engagement methods, we can help them maintain these essential social bonds. Furthermore, many clients desire to leave a legacy, which can become an integral part of their therapy. We can support this by exploring meaningful activities or projects that allow them to contribute something lasting and significant.

The concept of "living as long as you live" resonates deeply within occupational therapy. It's about ensuring that every day counts and that life is filled with meaning and activity, regardless of the challenges. This is the essence of our profession—empowering individuals to continue doing, participating, and living fully, even in the face of serious illness.

However, it is crucial to recognize that many palliative care patients are not receiving the comprehensive care they need, including access to occupational therapy. This gap in service highlights the importance of advocating for our role within palliative care teams. By integrating occupational therapy more fully into these teams, we can better meet the needs of these individuals, ensuring they have the opportunity to live as fully as possible every day.

Occupations

Hammil, Bye, & Cook's (2014) study remains highly relevant today despite being conducted some time ago. Their findings highlight the importance of engaging in occupations to give patients a critical sense of control. This aligns closely with the results of the Gallup survey, which identified loss of control as one of the primary fears among patients. By creating opportunities for occupational participation, we can help restore a sense of control and balance, which is particularly vital for individuals facing terminal or life-threatening illnesses. In this context, occupations can be a grounding force, providing much-needed stability during a turbulent time.

Kealy & McIntyre's (2004) research further supports this concept, emphasizing that patients strongly desire to continue engaging in activities. One significant activity that patients often wish to pursue is simply going outdoors. This underscores the importance of facilitating engagement in meaningful activities that provide a sense of control and enhance the quality of life by enabling connection with nature and their surroundings. These insights remind us that occupation is not merely about the act of doing but about empowering individuals to maintain their sense of self and autonomy, even in the face of serious illness.

This is a picture of some of my relatives (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Author's relatives outside.

Reflecting on Aunt Dorothy's and her sister's experiences, I’m reminded of the profound joy and connection they found in simply being able to go outside, ride their scooters, and be part of the community. Despite the challenges they faced, these outings offered them a sense of freedom and normalcy that was deeply meaningful. I was always struck by how skillfully Aunt Dorothy could walk her dog while maneuvering her scooter. It was clear that this simple activity brought her a great deal of pride and fulfillment, especially because it allowed her to remain active and engaged with the world around her.

I also think back to a palliative care patient who had a strong desire to take a bath—a routine that many of us might take for granted, but for her, it was deeply tied to her sense of identity and well-being. However, safety concerns related to her balance and functional mobility made this cherished ritual challenging. We had to adapt by transitioning her to using a shower chair, which could have felt like a loss of independence. To preserve the comfort and specialness of her bathing routine, I suggested incorporating essential oils to create a spa-like atmosphere in the shower. This adaptation helped make the experience feel more peaceful and personalized, allowing her to retain some of the pleasure and relaxation she associated with bathing.

These experiences encapsulate what occupational therapy means to me: helping people continue to engage in the activities that matter most to them, even when significant obstacles arise. Whether enabling someone to enjoy the outdoors, facilitating social connections, or adapting personal care routines, my goal is always to support meaningful participation and enhance the quality of life for my clients. These moments of connection and creativity make the work so rewarding, as they underscore the vital role of occupation in maintaining a person’s sense of self and well-being, even in serious health challenges.

Attitudes to Ageing: An Overview of Australian Perspectives...(Jeyasingam et al., 2008)

This is another study that has similar findings and looks at unmet needs. I bolded a few areas.

- Washing self

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 27

- Unmet need (Patient): 3 (10%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 0

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 24

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 6 (20%)

- Dressing self

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 27

- Unmet need (Patient): 3 (10%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 0

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 24

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 6 (20%)

- Showering self

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 21

- Unmet need (Patient): 9 (30%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 0

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 24

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 6 (20%)

- Cooking

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 20

- Unmet need (Patient): 6 (20%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 4

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 15

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 5 (17%)

- Eating

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 29

- Unmet need (Patient): 1 (3%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 0

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 26

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 4 (13%)

- Walking

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 23

- Unmet need (Patient): 7 (22%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 0

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 18

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 12 (40%)

- Stairs

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 16

- Unmet need (Patient): 12 (40%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 2

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 10

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 14 (46%)

- Transfers

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 20

- Unmet need (Patient): 10 (33%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 0

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 19

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 11 (36%)

- Work

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 10

- Unmet need (Patient): 2 (7%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 18

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 6

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 3 (10%)

- Writing

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 29

- Unmet need (Patient): 1 (3%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 0

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 26

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 4 (13%)

- Transport

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 16

- Unmet need (Patient): 5 (17%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 9

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 13

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 8 (26%)

- Leisure

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 21

- Unmet need (Patient): 7 (22%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 2

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 14

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 11 (36%)

- Other areas

- Resolved or no need identified (Patient): 21

- Unmet need (Patient): 9 (30%)

- Not applicable (Patient): 0

- Resolved or no need identified (Caregiver): 20

- Unmet need (Caregiver): 10 (33%)

In reflecting on the study, several key unmet needs resonated with me, particularly in areas that align closely with our work as occupational therapy practitioners. One of the most striking findings was that many patients identified showering independently as an unmet need. They expressed that they weren't receiving the necessary support to perform this basic but vital activity of daily living. Similarly, difficulties with walking stairs and transfers were also highlighted. While some might initially think that physical therapy is the right intervention for these issues, I believe it’s crucial to dig deeper into the context of these activities.

For many patients, walking or navigating stairs isn’t just about mobility; it’s about accomplishing something meaningful—like saying goodnight to their children or having the comfort of sleeping in their own bed. These actions are deeply tied to their sense of normalcy and identity. This is where I see the unique contribution of occupational therapy. My role is to understand the significance behind these activities and to enable patients to continue participating in these essential routines, even in the face of physical challenges.

Transfers are another area of significant importance, especially as patients experience the inevitable decline associated with disease progression. While my goal is always to maintain or enhance function within the palliative care framework, I recognize the need to adapt as conditions change. By regularly assessing the patient’s needs, collaborating closely with the interdisciplinary team, and providing caregiver training, I can help ensure that patients receive the right support as their abilities shift.

Leisure activities were also emphasized as a crucial concern, reflecting patient and caregiver perspectives. In this context, leisure is about more than just passing time; it’s about engaging in activities that bring joy and fulfillment, even during illness. This study serves as a powerful reminder of the multifaceted needs of palliative care patients and our critical role in addressing those needs through thoughtful, patient-centered interventions.

Importance of OT Interventions (Phipps & Cooper, 2014)

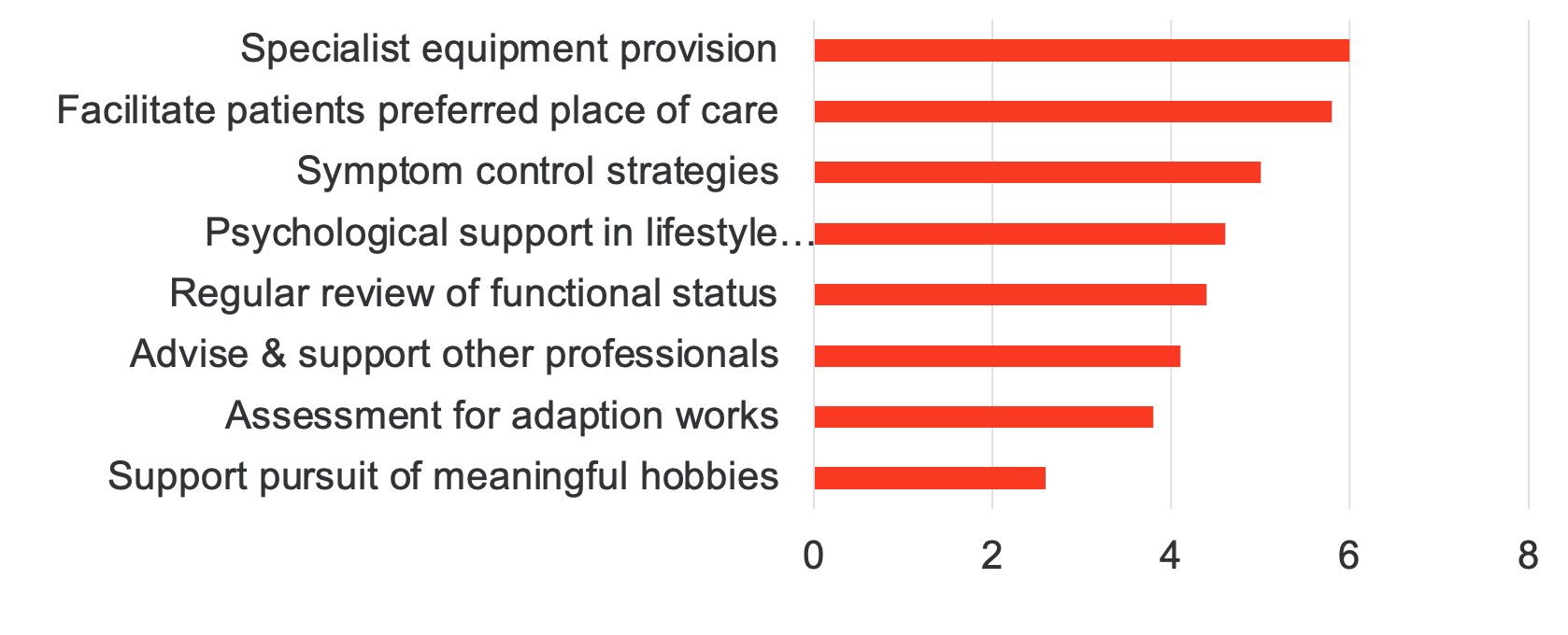

Phipps and Cooper (2014) looked at the importance of OT interventions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Results from the Phipps & Cooper study (Click here to enlarge the image.).

The study clarified that while we often provide adaptive equipment—and we do a great deal of that—our role extends beyond just supplying tools. We can be instrumental in guiding patients and their families to the best possible referral options. It’s about asking the critical questions: Is home the best setting for them, or do they need the support of skilled nursing? Would home health services be more appropriate, or is there another level of care that would better meet their needs?

Our work involves managing physical symptoms, providing psychological support, and helping patients develop effective lifestyle coping strategies. We look closely at their functional status, considering necessary modifications to their work environment if they’re still working and ensuring they can continue engaging in leisure activities that bring them joy. By addressing these various aspects, we help create a comprehensive plan that supports their overall well-being, ensuring they receive the right care at the right time.

The Gap

However, there remains a significant gap in care. According to a national home and hospice care survey, only 10.6% of participants received occupational therapy, even though 87.5% of patients needed assistance with one or more activities of daily living. Nearly 80% required help with essential tasks such as dressing, bathing, toileting, and transferring—yet they weren’t receiving occupational therapy services.

Even more concerning is that over 80% of the sample population was expected to live longer than six months. These patients are on palliative care with a significant time ahead of them, but they’re not getting the support they need to live with quality. This underscores the critical need for us, as occupational therapy practitioners, to be more involved. We need to step in and work with these patients to ensure they can maintain their dignity, independence, and quality of life during this time. Our role is vital, and we must advocate for greater inclusion in palliative care teams to meet these pressing needs.

Significant barriers still exist, particularly regarding the poor awareness of occupational therapy in palliative care. Many palliative care physicians may not fully understand who we are, how we can support their patients, and our valuable role as part of their team. There's also a lack of understanding about who can benefit from our services and, just as importantly, how to access those services.

It’s crucial that we don’t sit back and wait for these referrals to come to us. We must proactively contact palliative care teams and clarify that occupational therapy is essential to comprehensive care. We should be positioning ourselves so that when a doctor recognizes a need, they immediately think, "I need an OT," and know exactly how to find us. By raising awareness and making ourselves visible and accessible, we can ensure that more patients receive the occupational therapy services that are so critical to their quality of life.

Screening Questions

- Has the patient had any falls in the last 6 months?

- Has the patient experienced difficulty with ADL or IADL tasks over the past several weeks?

- Are there new upper-extremity flexibility restrictions or pain limiting everyday activities?

- Has the patient experienced new limitations in leisure or social activities?

- Has the patient experienced changes in memory, attention, or focus that have impacted participation in routine daily activities?

To ensure patients needing occupational therapy receive the necessary referrals, it’s helpful to provide clear guidance to nurses, case managers, social workers, and doctors—often the first to screen patients. For example, you might suggest that they ask if the patient has had any falls in the last six months. If the answer is yes, that’s a strong indicator to refer them to occupational therapy. Similarly, if the patient has experienced difficulty with activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living over the past several weeks, this would be another key reason to involve OT.

Other important considerations include whether the patient has new upper extremity flexibility restrictions or pain that impacts their daily activities. If so, OT could be beneficial. Additionally, if the patient has experienced limitations in leisure or social activities, it’s important to consider how OT might help them regain these meaningful aspects of life. Finally, any changes in cognition should prompt a referral to occupational therapy. If any of these issues are present, it’s crucial to ensure that the patient receives the support that OT can provide. By asking these targeted questions, healthcare professionals can better identify patients who would benefit from occupational therapy and help them access the care they need.

Evaluation Process

Once we've identified that a patient could benefit from occupational therapy, we, as OTPs, can step in and conduct a comprehensive evaluation. This allows us to determine the best course of action—whether the patient needs to be seen several times for ongoing therapy or if a consultative approach would be more appropriate. The key is to get through the door to make that decision and provide the needed care.

With our evaluation in hand, we can develop a tailored plan to address the patient's needs. It's important to note that most insurance plans do cover palliative care services, which include our interventions. This means we can effectively get involved and bill for our services, ensuring that the patient receives the occupational therapy support they require without financial barriers. The focus is on ensuring we’re there to help, providing the right level of care at the right time.

We always begin with an occupational profile, which is essential for us to truly understand the individual needs of our clients and to ensure that our interventions remain unique and within our scope of practice. This profile helps us tailor our approach to each patient, respecting their goals and priorities.

In addition to the occupational profile, you'll likely use your organization’s specific evaluation form during your assessment. When conducting evaluations in a palliative care setting, it's crucial to keep in mind that we are working with individuals who have serious, life-threatening illnesses. Many of you are already familiar with this population, but it's important to recognize that our role may vary depending on the stage of the illness. While we may focus on maintaining and increasing function initially, there will also be times when our primary goal shifts to helping the patient maintain their quality of life and as much function as possible as their condition progresses. This often means adapting our approach to address their chronic condition's increasing challenges, ensuring that we support them through every stage of their journey.

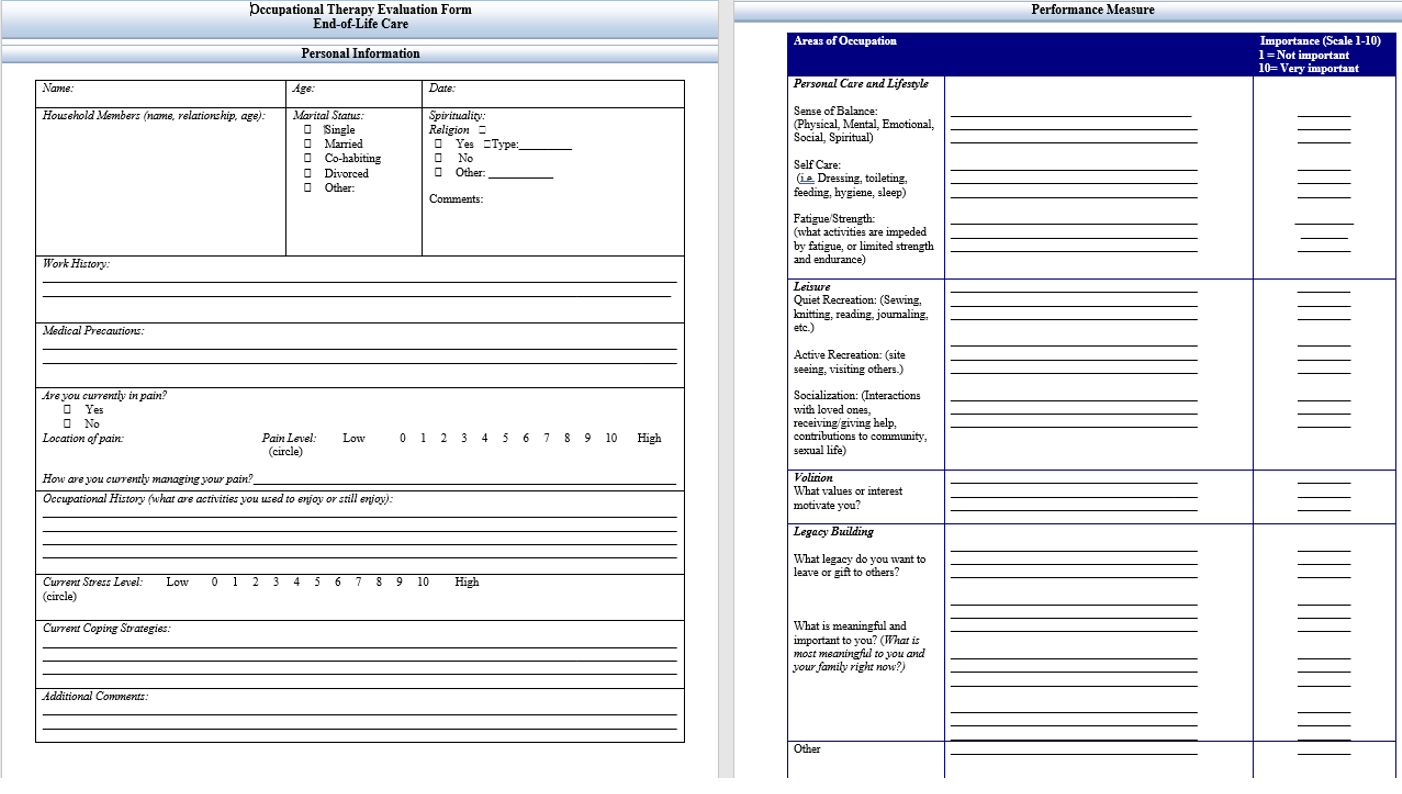

Figure 3 is an example of an end-of-life palliative care tool that I use when I visit Loma Linda as part of the team. It provides basic information.

Figure 3. End-of-life palliative care tool (Click here to enlarge the image).

When I begin an assessment, I want to gather comprehensive information about the patient to understand their needs and priorities. I start by exploring their work history and spirituality, which can offer valuable insights into what motivates them and gives their life meaning. I also assess any medical precautions and delve into their pain—specifically, where the pain is located, how they currently manage it, and how effective those strategies are. It’s important to understand what they are doing to manage their pain and how well those methods work for them.

I then focus on when the pain occurs and how it’s affecting their daily life. This leads me to explore their occupational history—what activities they enjoy, what they used to do but may no longer be able to, and how these changes impact their well-being. I also assess their stress levels and coping mechanisms to better understand their emotional state.

From there, I move into the specific areas of occupation, much like the approach used in the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. I go through various areas of occupation, asking the patient to identify where they are struggling. For instance, they might mention difficulties with taking a shower, expressing that they no longer feel safe due to a few close calls with falls. We would note this concern and discuss how important this activity is to them. They would then rate the importance of this activity, and from there, we set our goals, ensuring that the interventions are aligned with what truly matters to them. This process helps create a patient-centered plan that addresses their physical and emotional needs, enhancing their overall quality of life.

Interventions

OT Intervention: Problem Solving

Now, let’s move into interventions, which I find particularly exciting because occupational therapy practitioners are natural problem solvers. We always ask, “What do you want to do, and how can we help you achieve that despite your health condition?” This is where we dig into the occupational profile to understand what their daily life looks like or perhaps what they want it to look like. It’s about identifying what’s causing them difficulty and working together to find solutions that allow them to engage in meaningful activities.

Part of our role involves addressing the present challenges and preparing for potential declines. We need to deeply understand the disease process to anticipate and plan for changes before they lead to a crisis. For example, if a patient has COPD or a cardiovascular condition, we might discuss how overexertion could impact them and then develop a game plan for managing these situations if they arise. It’s about being proactive—ensuring they’re prepared for what might come next rather than being caught off guard by a sudden decline.

In addition to physical strategies, identifying and fostering coping mechanisms is crucial. Coping strategies are vital as they help the patient manage anxiety and adjust to their condition, enabling them to navigate the complexities of living with a serious illness. By integrating these strategies into our interventions, we support not just their physical health but their emotional well-being as well. This holistic approach is key to helping them live fully and meaningfully, despite significant health challenges.

Occupation & Identity

As we carry out our interventions, we must remember that everything we do is grounded in occupation and identity. Occupation provides us with purpose, shapes our experience of time and space, and helps organize our world. It gives individuals a sense of control, which is incredibly important, especially for someone navigating a chronic, serious disease. Occupation is also a powerful expression of identity.

When we work with a patient, we must see the person in front of us for who they truly are. We need to recognize their history, roles, and values—essentially, what makes them unique. Our job is to help them continue participating in the activities that define them, give their life meaning, and connect them to their sense of self. It’s not just about addressing their physical needs but also about supporting their identity through occupation. By doing so, we can help them maintain their dignity, autonomy, and quality of life, even in the face of significant health challenges.

Occupations provide a means of self-expression and engagement, granting meaning and purpose to the person and the family as they prepare for death and the following transition. We want to utilize the power of occupation throughout this process.

After our evaluation, we want to consider creating an occupation-based problem list. This chart shows examples.

Qualifying conditions | Types of interventions provided by an occupational therapy practitioner |

ADL/IADL limitation | ADL/IADL self-care, functional activity participation, therapeutic exercise, durable medical equipment recommendations |

Debility, fatigue, poor endurance | Therapeutic exercise, ADL/IADL self-care, functional activity participation, durable medical equipment recommendations, energy conservation |

Neuropathy

| Neuromuscular re-education, ADL/IADL self-care, therapeutic activity, therapeutic exercise, manual therapy, durable medical equipment recommendations |

Lymphedema | Manual therapy, ADL/IADL self-care, functional activity participation |

Cognitive decline | Cognitive therapy, ADL/IADL self-care, functional activity participation |

Upper extremity impairment

| ADL/IADL self-care management, neuromuscular re-education, functional activity participation, therapeutic exercise, manual therapy |

Balance

| ADL/IADL self-care management, neuromuscular re-education, functional activity participation, therapeutic exercise, durable medical equipment recommendations |

Pain

| Functional activity participation, ADL/IADL self-care management, therapeutic exercise, durable medical equipment recommendations |

Abbreviations: ADL, activity of daily living; IADL, instrumental activity of daily living. | |

(Qualifying conditions and potential interventions for occupational therapy; Pergolotti et al., 2016, p. 316)

We can start by identifying specific challenges the patient is facing. For example, if patients cannot dress their upper body, we must determine why. Is it due to poor upper body strength, limited active range of motion, or perhaps pain? Similarly, if a patient cannot independently cook for their family, we need to assess whether this is due to poor safety awareness or difficulty with sequencing. When considering these issues, asking what's causing them is crucial. Is the poor safety awareness a result of medication side effects, or is it related to the disease process itself? The same applies to difficulties with sequencing—understanding the root cause will guide how we focus our interventions.

We then consider whether to approach the issue with compensation strategies or remediation. What do we expect to achieve? It’s important to always return to these occupation-based problem statements because they directly inform our goals, which drive our interventions. This approach ensures that our interventions are targeted and effective in addressing the patient's needs.

Intervention Areas

When we move into intervention areas, there are several key aspects to consider, particularly in patients with serious, chronic, and life-threatening conditions. One of the primary areas is ADL retraining, which involves working on upper and lower body dressing, grooming, and assessing where things are located in their home. A home evaluation can be incredibly insightful for identifying potential adaptations and assessing the need for adaptive equipment. Training in energy conservation is also essential, not only for the patient but also for their caregivers. We must be mindful that these caregivers often process the emotional weight of their loved one’s condition, and our approach to caregiver education must be sensitive and thorough.

It’s important to ensure that caregivers are not just shown what to do but are actively involved in the learning process. This involves explaining, demonstrating, and then having them perform the task themselves to ensure they feel confident and capable. For instance, if a caregiver is learning to assist with transfers or dressing techniques, we might need to show them alternative methods or strategies if the initial approach isn't effective. This hands-on education is crucial for adapting care as the patient's condition evolves.

Energy conservation and fatigue management are critical elements, particularly as we help patients pace themselves throughout the day. Addressing feeding issues is another significant area, especially when conditions or medications may cause challenges like dry mouth or decreased hand-eye coordination. For many, meal times are social and emotional events, and maintaining independence in feeding can be vital for their dignity and quality of life. For example, if a patient struggles with holding a mouth swab due to fine motor issues, we might need to adapt the handle to make it easier for them to use independently, preserving their dignity.

Functional mobility is another area of focus—determining what devices the patient might need and understanding their goals and the activities they wish to continue. We also need to consider sleep-related issues, such as insomnia, which could be related to medication or anxiety. Addressing sleep hygiene and adjusting their sleep environment can significantly improve their rest.

Pain management is always a critical component. Understanding how pain impacts their function, we might need to look at their positioning or ergonomics to find ways to minimize discomfort. We also need to consider how they’re coping with pain, especially since too much medication could make them groggy and less able to interact with loved ones. Sometimes, the goal is to find that balance where they can manage some pain level while still being present and engaged in meaningful activities.

Self-esteem and body image are also important to address. Patients may have concerns about their appearance or how they communicate with loved ones, and the intimate nature of OT allows us to have these important conversations. We can help them express their fears and possibly make referrals to other disciplines for additional support if needed.

Finally, we look at strengthening, managing swelling, and positioning, which could include lymphedema management. Each intervention area is designed to support the patient’s quality of life, allowing them to maintain dignity and participate in the activities that matter most to them.

Looking at Lifestyle Interventions for a Holistic Approach

As you might have gathered from my bio, I have a strong passion for wellness, and I believe it's essential to incorporate that focus into our work with patients. Our lifestyle choices profoundly impact our health, and as occupational therapy practitioners, we can play a significant role in supporting our patients in making healthier choices.

For instance, about 19.4% of cancer diagnoses are linked to smoking. Depending on your work setting, you might have the opportunity to help patients become more aware of the risks associated with smoking and support them in reducing or quitting. Similarly, 7.8% of cancer diagnoses are related to obesity or being overweight. We can assist patients with health management strategies, encouraging them to engage in physical activity and adopt healthy eating habits—all of which are integral to our practice framework.

Approximately 5.6% of cancer diagnoses are attributed to alcohol consumption. If you're working with a patient who struggles with alcohol use or perhaps just consumes more than is healthy, you can provide education and support around reducing alcohol intake. Additionally, 4.7% of cancer cases are related to exposure to sunlight, and 4.2% to poor dietary habits. Again, promoting healthy eating is something we can emphasize in our interventions. Lastly, 2.9% of cancer diagnoses are linked to insufficient physical activity.

These statistics highlight just how much our lifestyle choices affect our health. When we work with patients, incorporating wellness and lifestyle education into our interventions can make a significant difference, not just in managing their current conditions but also in improving their overall health and well-being.

We really need to emphasize the importance of a healthy lifestyle in our work with patients. Many of us might struggle with a poor diet, lead a sedentary life, smoke, or consume alcohol. However, if we address these factors, research from the American College of Lifestyle Medicine suggests that we could prevent up to 80% of heart disease and strokes, which are conditions you're likely encountering, whether you're in acute care, rehab, or palliative care. Additionally, 80% of type 2 diabetes and 40% of cancers can be prevented. Even for patients in palliative care, focusing on these preventive measures can make a significant difference.

So, what are some solutions? One key approach is to encourage a more whole-food, plant-predominant diet. Another is to promote the national recommendation of 150 minutes per week of moderate exercise. As an OTP, you can tailor these recommendations to your patient’s specific health condition, abilities, and physical challenges. It’s about finding safe and effective ways for them to engage in physical activity.

Beyond diet and exercise, helping patients achieve 8 hours of restful sleep and manage their stress levels are also critical components of a healthy lifestyle. We should also emphasize the importance of not smoking and help our patients connect with the people around them. Social connection is a vital part of well-being, and as OTPs, we can facilitate these connections, helping patients to maintain a strong support network. Through these lifestyle interventions, we can help manage existing conditions and prevent the onset of new ones, ultimately improving our patients' quality of life.

Address Pillars of Health

These considerations align perfectly with the pillars of health outlined by the American College of Lifestyle Medicine, and they fit seamlessly within the scope of occupational therapy. Healthy eating is a key component of health management, and it directly ties into one of our instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)—meal preparation. Physical activity is another crucial aspect of health management that we address in our practice.

Stress management also falls under health management, reinforcing its relevance to our work as OTPs. Social participation is one of our core areas, and sleep is another essential focus. Lastly, avoiding risky substances impacts every area of our practice, influencing our clients' overall well-being and health. These pillars of health guide our interventions and underscore the comprehensive, holistic approach occupational therapy brings to patient care.

OT Evidence in Palliative Care

We see a clear impact when we look at the evidence supporting occupational therapy interventions in palliative care. For instance, Li, Chen, and Wang conducted a randomized controlled trial in 2005 that focused on feeding interventions. Over three weeks, they provided positioning recommendations, feeding aids, and upper extremity supports, finding that OT made a significant difference for palliative care patients. This underscores the importance of addressing feeding as a critical area of intervention.

Another study by Sakin and colleagues involved a two-week OT and PT program that emphasized walking, transfer training, positioning, and balance. Although the study included both OT and PT, it was evident that these interventions were effective for patients in palliative care. Similarly, Serek and Hartley conducted a four-week European program that combined OT and physiotherapy, focusing on patient resources such as fatigue management, pacing exercises, relaxation techniques, and healthy cooking. They also found that OT and physiotherapy were beneficial in improving the quality of life for palliative care patients.

These studies prove that occupational therapy interventions can significantly enhance patients' care and quality of life in palliative settings, whether focused on feeding, mobility, or overall well-being.

Adapting Occupations for End of LIfe

End-of-life care is fundamentally about adapting occupations to meet our clients' changing needs and abilities. I had a client in the hospital facing a life-threatening disease, and during one of our conversations, she expressed how difficult it was to find meaning in her days. She told me she just slept most of the time and felt terrible because she had nothing to do. So, I asked her about activities she used to enjoy, and she mentioned that she loved doing calligraphy when she was younger.

As it happened, I had a calligraphy pen, though I wasn’t skilled with it. I brought it to the hospital the next day, and we began practicing together. During that session, she decided to write a note to her parents, thanking them for all they had done for her in her life. About a year later, she passed away, but I can only imagine how much that letter meant to her parents. This experience really highlighted for me the importance of adapting occupations, particularly in a palliative care setting.

This naturally leads us to the concept of legacy. Helping people create and leave a legacy is about more than just preparing for the end; it’s about giving them a way to express what’s important to them and share that with their loved ones. It’s a sensitive topic because discussing legacy often brings up thoughts of dying. However, palliative care can be introduced earlier when the person feels healthier and more capable. This approach allows them to engage in meaningful activities, like writing letters or creating something special for their family, without the pressure of time or declining ability.

Legacy

Legacy should indeed be a family-based intervention, and I believe that we, as occupational therapy practitioners, can play a pivotal role in orchestrating this process. We can act as the conductor, guiding the patient and their family through creating meaningful legacy activities. Our role is to help the patient identify what they want to do—sharing stories, creating keepsakes, or engaging in special activities—and then facilitate the family’s involvement in these tasks.

For example, I’ve seen the power of involving family members, including grandchildren, in these legacy projects. In one case, a wife was heartbroken because every time the family visited, her husband, who was in palliative care, would just sit in his chair and fall asleep, leaving the grandchildren awkward and disengaged. We worked together to create a "jar of opportunity"—a fun, interactive way for the patient to share stories, play short games, or engage in meaningful activities with his family. The patient would prepare stories or activities ahead of time, and when the family visited, they would take turns pulling an item from the jar, sparking conversation, or a brief game.

This simple intervention transformed their visits. The grandchildren were excited to participate, and the patient became more engaged, sharing stories and playing games with his family. It was a small but powerful way to bring meaning and connection to their time together, creating lasting memories for everyone involved.

Some research, such as Alan's work, shows the positive impact of these types of interventions, though the evidence is still emerging. Nevertheless, I believe we, as OTPs, have a significant role to play in facilitating these legacy activities. By helping families create and participate in these meaningful experiences, we can contribute to both the patient’s and the caregiver’s sense of connection, purpose, and fulfillment during a challenging time.

Important Considerations for Legacy Building With Patients & Families

When considering legacy work, it’s crucial to implement it early. For instance, someone might desire to write cards for family members, but writing may become physically challenging as the disease progresses. That’s where our skills as occupational therapy practitioners come into play. We can adapt the task—perhaps they can dictate their messages for someone else to write, or we can explore recording audio or video messages instead. Early implementation allows for more creativity and flexibility, but it’s comforting to know that we can always find a way to adapt as needed.

Our task analysis skills are vital in this process, whether we're focusing on legacy projects or helping patients participate in their daily occupations. We must consider the patient’s diagnosis, safety, medications, endurance level, and overall condition to determine the best way to support their participation in meaningful activities. Task analysis helps us break down the activity into manageable steps and find the best approach to meet their needs.

When guiding families in legacy work, it’s important to plan short sessions. You don’t want to overwhelm the patient or their loved ones with overly intensive activities. As the OTP, you can suggest keeping sessions to 10 to 15 minutes, depending on the patient’s endurance. Short, focused sessions can be more manageable and enjoyable, allowing for meaningful engagement without causing fatigue.

It’s also essential to capture the simple moments. While elaborate plans can be wonderful, it’s often the simple memories that hold the most significance. Small, everyday interactions—like a conversation about flowers that brings back childhood memories—can be incredibly meaningful. Encouraging the family to be involved in these simple yet profound moments can create lasting memories that are cherished long after the session ends.

By being thoughtful in our approach and using our skills to adapt and plan, we can help patients and their families create and preserve meaningful legacies that reflect the true essence of their lives and relationships.

Wrapping Up

As we wrap up this brief introduction to palliative care, I hope you’re feeling energized about our vital role in this field. We have a significant role, and I believe each of you already possesses the skills needed to make a meaningful impact. However, it's crucial that we advocate for our place in this area and continue to build our presence in palliative care.

Everything we do in palliative care falls squarely within our scope of practice as occupational therapy practitioners. We bring unique expertise in analyzing tasks, breaking them down, and understanding performance patterns, skills, and client factors. This enables us to address the specific needs of our clients, helping them continue to engage in the activities they value, reducing their fears, and alleviating the burden they may feel they impose on others. Our goal is to promote occupational participation and, ultimately, to improve quality of life.

Remember, patients want to continue living their lives fully, even as they face serious illness. They want to maintain control and avoid becoming a burden. We are a crucial part of the interprofessional team that helps them achieve these goals.

As we reflect on our learning outcomes, I hope you now have a clearer understanding of palliative care as a practice area. You should be able to differentiate it from hospice care and recognize our specific contributions to the palliative care team. When engaging with a palliative care team, keep in mind that the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) offers resources to help you advocate for your role. Use these tools, bring your business cards, and ensure that healthcare providers know how to reach you when they need to make a referral.

Finally, while we do have existing evidence to support our interventions in palliative care, there is always room for more research and data to strengthen our position. Let’s continue to build on that evidence base and advocate for occupational therapy's essential role in enhancing the lives of those in palliative care.

Questions and Answers

Do you have to worry about reimbursement in palliative care, or is OT just a service provided? Many areas of intervention seem to be declined because of insurance reimbursement limitations.

Reimbursement is a challenge, but we need to advocate for OT in palliative care. It is billable, and our role can be justified. I would challenge us all to consider how having OT as part of the service could help decrease costs. For instance, when we address skin integrity, prevent infections, and reduce fall risks through energy conservation and task analysis, we might lower overall costs by preventing hospital-induced expenses. Research is crucial to demonstrate these broader outcomes.

How do you approach a terminal patient who denies all interventions, even after education? They are full of anxiety and want so much control that not accepting help hurts them.

This is a sensitive question. It’s essential for us, as OTPs, to reflect on our own views about chronic disease, terminal illness, and end of life, both personally and professionally. Respecting where the patient is emotionally and mentally is key. Listening to them, validating their feelings, and gently trying to uncover what might be behind their denial can be helpful. However, we must also respect their choices and find ways to honor those decisions while supporting them as best we can.

Does a palliative care patient have options for family to receive respite care?

Respite care typically becomes available when a patient transitions to hospice. However, if the family is in need, it’s worth discussing with the palliative care team. It might not be included in the treatment package until hospice care, but having a conversation with the physician leading the team could lead to exploring other options, such as a change in environment. OTPs can play a crucial role in guiding these discussions.

Can home health and palliative care be reimbursed at the same time?

Typically, we would work under one umbrella or the other—either as a home health OTP or within palliative care. However, a patient receiving home health services could also receive palliative care. As OTs, it’s important not to work in silos but to communicate effectively with the palliative care team to ensure continuity of care. Understanding the prognosis and preparing for disease progression is crucial in this context.

How can I best advocate with a patient’s family who is having trouble accepting that the end of life is near?

This complex issue could warrant an entire discussion on its own. Working closely with your team is essential. I’ve been fortunate to collaborate with a gifted palliative care doctor who excels in these conversations, listening carefully to patients and their families and guiding them with compassion. You might also consider referring the family to a chaplain or other support services aligned with their belief or value system. The key is approaching this as a team effort, navigating these difficult conversations together.

We’ve come to the end of our session. Thank you for your thoughtful questions and engagement.

References

Center to Advance Palliative Care. (2014). Palliative care facts and stats. Microsoft Word - press-kit-onePagers-R1.docx (capc.org)

Hammil, Bye, & Cook. (2017). Workforce profile of Australian occupational therapy practitioners working with people who are terminally ill. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(1), 58-67.

Hasselkus, B.R., (2021). The meaning of everyday occupation. 3rd ed. Slack Inc.

Hunter, E. (2008). Beyond death: inheriting the past and giving to the future, transmitting the legacy of one’s self. OMEGA, 56(4), 313-329.

Jeyasingam, L., Agar, M., Soares, M., Plummer, J., & Currow, D. C. (2008). A prospective study of unmet activity of daily living needs in palliative care inpatients. Australian occupational therapy journal, 55(4), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00705.x

Kealy & McIntyre. (2005). An evaluation of the domiciliary occupational therapy service in palliative cancer care in a community trust: A patient and carers perspective. European Journal of Cancer Care, 14(3), 232-243.

Khosla D, Patel FD, Sharma SC (September 2012). Palliative care in India: Current progress and future needs. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 18(3), 149–154. doi:10.4103/0973-1075.105683. PMC 3573467. PMID 23439559.

Mueller, E., Arthur, P., Ivy, M., Pryor, L., Armstead, A., & Li, C. Y. (2021). Addressing the gap: Occupational therapy in hospice care. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 35(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2021.1879410

National Hospice Organization. (1996). Gallup survey.

National Institute on Aging. (2021). What are palliative care and hospice care? | National Institute on Aging (nih.gov).

Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition. (2020). Am J Occup Ther, 74(Supplement_2), 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Pergolotti, Williams, Campbell, Munoz, & Muss. (2016). Occupational therapy for adults with cancer: Why it matters. The Oncologist, 21, 314-319.

Phipps, K. & Cooper, J. (2014). A service evaluation of a specialist community palliative care occupational therapy service. Progress in Palliative Care, 22(6), 347-351.

Rhiner, M., & Mohr, G. J. (2019). Palliative care competency part 1: Palliative care an overview. Loma Linda University.

Saarik, J., & Hartley, J. (2010). Living with cancer-related fatigue: Developing an effective management programme. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 16(1), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.1.46178

Sekine et al., (2014). Changes in and associations among functional status and perceived quality of life of patients with metastatic/locally advanced cancer receiving rehabilitation for general disability. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 32(7), 695-702

Von Post, H., & Wagman, P. (2019). What is important to patients in palliative care? A scoping review of the patient’s perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 26(1), 1-8.

Wilcock, A., Howard, P., & Charlesworth, S. (2022). Palliative care formulary (PCF8) eighth edition. Pharmaceutical Press.

World Health Organization. (2020). Palliative care: Key facts. Palliative care (who.int)

Yerxa, E. J. (1994). Dreams, dilemmas, and decisions for occupational therapy practice in a new millennium: An American perspective. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48(7), 586–589. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.48.7.586

Citation

Javaherian, H. (2024). Palliative care and occupational therapy: Our unique role. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5726. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com