Introduction

Good afternoon. I'm so glad to be here and have an opportunity to teach on well one of my many favorite subjects, but bringing yoga into the work we do and the practices we do. First off, let's look at our learning objectives. As a result of this course, participants will be able to name three aspects of brain function which are altered by chronic pain, describe the neuromatrix of pain, and list three yoga treatment options to manage chronic pain.

Pain

What is Pain?

What is pain? Let's start with a video.

Video 1.

Pain occurs when something hurts. We all know that. Causing an uncomfortable or unpleasant feeling. Now the presence of pain often means that something's wrong. Each individual is the best judge of his or her own pain. There is an estimated 50 to 75 million Americans living with chronic pain, and chronic pain decreases function, causes anxiety and depression.

Pain Theories

There are a multitude of pain theories.

- Intensive Theory (Erb,1874): Defines pain, not as a unique sensory experience but rather, as an emotion that occurs when a stimulus is stronger than usual.

- Specificity Theory (Von Frey, 1895): Specific pain receptors transmit signals to a "pain center" in the brain that produces the perception of pain

- Strong's Theory (Strong,1895): Pain was an experience based on both the noxious stimulus and the psychic reaction or displeasure provoked by the sensation.

- Pattern Theory (Nafe,1929): People feel pain when certain patterns of neural activity occur, such as when appropriate types of activity reach excessively high levels in the brain

- Central Summation Theory (Livingstone,1943): Prolonged abnormal activity bombards cells in the spinal cord, and information is projected to the brain for pain perception.

- The Fourth Theory of Pain (Hardy, Wolff, & Goodell, 1940’s): It stated that pain was composed of two components: the perception of pain and the reaction one has towards it.

- Sensory Interaction Theory (Noordenbos,1959) It describes two systems involving transmission of pain: fast and slow system.

- Gate Control Theory (Melzack and Wall,1965) pain stimulation is carried by small, slow fibers that enter the dorsal horn of the spinal cord; then other cells transmit the impulses from the spinal cord up to the brain.

If I started going through every one of these, I would not have time to get to the treatment aspects that I want to talk to you about. I have included them so that you can take a look at them on your own time. It is really interesting how this has all developed over many many years.

Through my own experience, I have done my own research on pain management. In 2001, I was in a motor vehicle accident and sustained spinal injuries in a result. After multiple surgeries, I found myself completely debilitated because of pain, and it was not until 2006 when my son introduced me to yoga, that I actually started to find a way out of the situation. Another thing that helped is that I had a physician who gave me a list of descriptors of what pain was. When I read the word "exhausting," I finally knew that I found someone who could understand a bit of what I was experiencing.

One of the things that really resonates with me and makes a lot of sense is the theory of the neuromatrix of pain.

The Neuromatrix of Pain

The neuromatrix of pain says that pain occurs within the central nervous system, which we all know is made up of the brain and spinal cord. This is because pain is produced within the brain and affects multiple parts of the brain and spinal cord. They work together to respond from a stimulus of the body and the environment. This what creates the experience of pain.

By shifting the experience of pain from the tissue damage in the peripheral nervous system into the central nervous system, it actually gives us a much wider field for recovery and options for treating and managing chronic pain. Much of this research came out of working with amputees and phantom limb pain. If you have an amputation, the pain originates in the peripheral nervous system. After many months of healing, the pain should stop. Phantom limb pain, however, can persist and is definitely within the central nervous system.

Pain Response from the Brain

The pain response that occurs within the brain is when the brain receives signals from different portions of the body that is injured or is perceived to be injured. The brain immediately determines the best way to respond to the injury. The amygdala senses that a threat has occurred, or may occur, and signals are sent to the areas of the brain that initiate a series of very complex neuro endocrine, neuro hormonal and neuromuscular responses. These changes in the body further set up that chain reaction of fight or flight, or self protection responses. The amygdala is actually acting as the body's smoke detector. It senses an alarm, it senses something may be wrong, and then it sets off into action. Even if it is only a perceived threat, it is immediately on guard and ready to make the decisions that are needed. Other areas of the brain suddenly receive the alarm response and determine the best way to respond like pulling your hand away quickly, fight or flight, running, or a freeze response. The brain considers all of these factors in a nanosecond. Once that sets up within the central nervous system, it is a little more challenging to reverse that order. Let's see if we can give you a small example of this, with this next video.

Anticipation of Pain from a Learned Experience

Video 2.

Trauma of any sort, be it acute, chronic, emotional or a combination of them utilizes the brain mechanism of the amygdala in perceiving a threat and sending signals to other areas of the brain to respond. The same time the trauma occurs, literally every other sensory input, taste, smell, hearing, etc. gets recorded in the brain as an associated memory of the traumatic event. The brain signals a series of physical responses such as inflammation at the site of the injury as well as a perception of pain. Sometimes the alarm signal in our brain in the area of the amygdala can be activated when a physical experience or threat is not actually occurring. Past pain can make you more sensitive to future pain. You can thank one of the great wonders of the nervous system, its ability to learn in response to experience. This ability is called neuroplasticity. Through the repeated experience of pain, the nervous system gets better at detecting the threat and producing the protective pain response. So unfortunately, in the case of chronic pain, learning from experience and getting better at pain paradoxically means more pain, not less.

The more pain we experience, the better we get at experiencing pain. Continuing to learn from our past mistakes. We can add to this though, more than just the instant of injury, touching the stove.

The Biopsychosocial Model of Pain

This states that pain is not simply physiological. It also involves social, psychological, culture, familial history, and so many other environmental influences that impact on a person's emotions, perceptions, their ability to learn, their behavior, and their cognition. It sets in motion a train, or what we like to call a "train wreck." The engine might start off the pain response, but it might not be until the caboose runs over you that you have finally had enough. The influence of what is happening in your environment can also perpetuate the pain. Many times the fear of change, like starting a new career after an injury, can set up more pain as a learned response.

Why Is Pain So Complicated?

- Pain has been reported by people for whom there is no physiological evidence for feeling pain.

- Environmental factors and individual differences make pain a subjective experience that is difficult to assess.

- Research on pain is limited by ethics restrictions that minimize animal subjects' pain and suffering, and not many humans volunteer for pain studies.

Pain has been reported by people for whom there is no physiological evidence for feeling pain. Environmental factors and influences impact pain, and it is a subjective experience. Many years ago, we started asking clients, "What level is your pain?," and we came out with the 10 smiley face scale. "Point to the level of pain you're at." With this scale, I assume that you are going to perceive pain the same way I do, however, this is not true. For someone a pinprick could be devastating, while someone else can tolerate being run over by a steam roller. So, everyone experiences pain differently.

Research on pain is limited by ethics' restrictions. We are not going to inflict pain on a person in order to find out what pain feels like. This is just common sense.

Acute Versus Chronic Pain

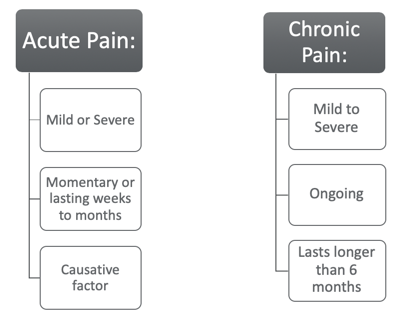

Figure 1 shows a comparison between the two.

Figure 1. Acute versus chronic pain.

Acute Pain

Acute pain typically has a sudden onset, and it can occur from a sudden injury, surgery, broken bones, dental work, or burns or cuts. It can have some residual effects, and there is usually a causative factor. For example, when you touch the hot stove, you burn yourself and incur an injury and pain.

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain, however, is pain that is ongoing, usually lasts longer than six months, and this type of pain can continue even after the injury or illness that caused it has dissipated or gone away. Pain signals remain active in the nervous system for weeks, months, or years. Some people suffer chronic pain even when there is no past injury or apparent damage. Chronic pain is linked to conditions like headaches, arthritis, cancer, nerve pain, back pain, and fibromyalgic pain. The more we learn about each of these conditions, we produce more questions. There is a significant difference between what is occurring in acute pain and chronic pain. Keeping that in mind, an acute incident can easily cross over into a chronic pain situation.

Chronic pain is multidimensional. You are experiencing something physically as well as emotionally and socially. In that previous vignette where you touched the stove and burned yourself, you now might remember the pain of touching the stove and get to a place where you decide it is not even worth cooking. It changes your behaviors. And, if it is too painful to get dressed and go out to dinner, you are limiting your social interactions. It continues to affect so many areas.

It also has a negative influence on the muscles of your body, patterns of breathing, and energy levels, as well as, your mindset. If you have ever had a toothache or a sore in your mouth, it is just amazing how the brain gets so focused on that little pinpoint pain. Sometimes, you cannot even think straight anymore. All of this gets exasperated by what is happening in the person's life. "Mom's in bed again as she can't get up and get us to school." "Dad is home from work, and he's miserable." Children and other family members are not feeling the pain, but they are seeing and feeling the results of it. This can cause a different level of stress on the individual. Chronic pain not only debilitates the client, but everyone around them. It is one of those things that will continue to perpetuate not only itself, but so many aspects of disfunction within the life.

Unique Aspects of Chronic Pain

- The longer that pain persists, the easier it is to feel it.

- You can feel pain from factors unrelated to physical harm.

- Your central nervous system adjusts the "volume level" of pain signals sent to your brain.

- All pain has a psychological component.

- Significant emotional distress is common in chronic pain.

The longer the pain persists, the easier it is to feel it. This is that learned response. You can feel pain from factors unrelated to physical harm. One of the things that I have always heard is that if the brain could really remember pain, none of us would exist after the first woman gave birth. She would never put herself through that again. If you hve ever had a child, you can recall the occurrence of that pain, but then the offset of having this child, balances that pain response for most people. Your central nervous system will adjust to the volume level of pain. Again, some people feel a pinprick and it is excruciating, while others could crush their hand in a roller and just walk away. Next day, we're all good. All pain has a psychological component to it, and this significant emotional stress is common with chronic pain.

Fear of Pain

Fear of pain is another big component. People who have chronic pain feel those effects of stress on the body, and it sets up fear of the anticipation of more pain. That tenseness in the muscles starts to effect your breathing, your energy levels, and appetite changes.

The Impact of Chronic Pain

- Emotional

- Social

- Interpersonal relations

- The loss of roles

- Intellectual

- Spiritual

Emotional effects of chronic pain include depression, anger, anxiety, and fear of reinjury. This fear can be so much more powerful than the pain itself. The International Association on the Study of Pain defines pain as a subjective unpleasant sensory emotional experience due to an actual or potential injury, or described in terms of the injury. It acknowledges that there is this mind-body aspect of the experience, and again, qualifying it is subjective.

The experience first occurs in our consciousness, and then it begins to reflect in the psychological and behavioral planes. It is not just the physical aspect. Again, if it was just a physical aspect, once the cut healed, the pain would be over. You would be fine and keep moving with life.

As OTs working in this field, we can effectively use this knowledge of the relationship between the physical aspect of pain with the psychological, the emotional, and the behavioral aspects. In understanding and caring for our clients with chronic pain, we do not just look at the pain, but we look at the whole person. We are not quick to say they are making it up. I love being an OT, and part of it is the aspect that we are willing to step back and look at the whole person. We see different aspects of their life which may be causing a great deal of this. We have already spoken quite a bit about the different areas the impact pain. Chronic pain decreases function and causes anxiety and depression. The physiology in this state of persistent stress affects the pituitary glands, the adrenal glands, the nervous system, and how that impacts everything emotionally.

Being able to get up and get out and function and interact with others is very important.