Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: Understanding And Treatment From An OT Perspective, presented by Zara Dureno, MOT.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the definition of trauma and OT's role in treating it.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the impact of trauma on the body and brain.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify 3 strategies they can use with their clients who have trauma.

Introduction

Thanks so much for having me. I'm excited to be here today to talk about post-traumatic stress disorder, a topic I am very passionate about. Over the last three years, of working in neurological rehab, I've discovered that many people have trauma, either from an accident they have experienced or perhaps childhood trauma. This trauma was impacting their care, and it wasn’t until I started to learn about PTSD that I felt I could truly serve many of my clients in a holistic way, which aligns with the essence of OT.

Today, I’m hoping we can all learn more together about PTSD, including how it may impact clients across OT practice settings. We’ll discuss an OT perspective on treatments and strategies we can use. These are the disclosures for today's talk.

About the Speaker

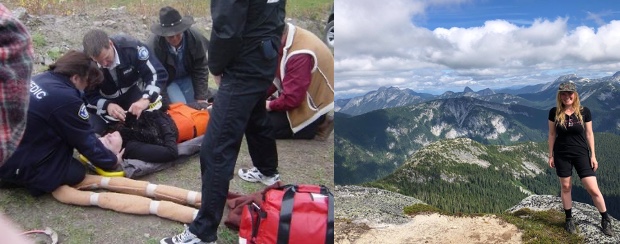

A bit about me – I’ve been in three major accidents in my life. One was a horseback riding accident, another was falling down the side of a mountain, and a boating accident. Each involved a serious threat to my life and physical harm. Interestingly, I only had traumatic responses to the mountain event. This demonstrates how different situations that may objectively seem traumatic can affect people differently on an individual nervous system level. You can experience many adverse events, yet only some may be processed as traumatic. We’ll explore more about the definition of trauma and how it manifests uniquely later.

As you can see in the photo (Figure 1), despite my trauma history, I have returned to hiking and mountaineering, an occupation deeply meaningful to me.

Figure 1. Image of the author after an accident and another while climbing after recovery.

This was possible through applying an OT lens, including the strategies I’ll share today, to manage my thoughts and body responses to the trauma. My perspective comes not only from personal experience but from working with traumatized clients over the past few years, along with extensive reading and training on PTSD.

Trauma Sensitive Topic

I want to offer a caveat before we get into the details that trauma is a sensitive topic. Most people have likely experienced some trauma in their life. If you feel triggered or uncomfortable at any point, please do what you need to take care of yourself, whether stepping away or taking a break. This is heavy material that may bring up difficult emotions, so self-care is important. I'd recommend afterward taking some time to move your body, get outside, or engage in other wellness practices to allow your nervous system to settle. Just a reminder to be gentle with yourself.

Defining Trauma

- “Trauma is a term used to describe the challenging emotional consequences that living through a distressing event can have for an individual.” –Canadian Mental Health Association (2023)

- It often involves a threat to your life and safety or the life and safety of someone in your vicinity, but anything that overwhelms the nervous system’s ability to cope can result in trauma.

Let's talk about the definition of trauma. There is no universal consensus, though associations like the Canadian Mental Health Association have proposed definitions. If you look it up in various sources, there will be slight differences. Among healthcare professionals, consistency is lacking in precise parameters. Basically, I view trauma as anything that overwhelms our nervous system's ability to cope.

The Canadian Mental Health Association describes it as the challenging emotional consequences that living through distressing events can have for an individual. Trauma generally involves a threat to life or serious injury, including a perceived threat to someone in your immediate environment.

Usually, if an experience is traumatic, it also encompasses significant perceived danger, which triggers related nervous system responses. We’ll explore the physiology behind those reactions shortly.

It’s important to recognize trauma is not the same for every person. Two people could endure identical situations, yet only one develops PTSD. It depends on individual nervous system sensitivity and coping abilities. Thus, it's not the event itself that directly causes trauma, but rather how our nervous systems respond.

Having a broad conceptualization of trauma can be beneficial and inclusive since many don’t recognize their experiences as such. However, it’s also important not to trivialize the term by applying it too loosely in everyday language. We've all heard trauma used casually like "that meeting traumatized me" which risks diluting its meaning. A compassionate middle ground of understanding trauma through an open yet respectful lens is ideal.

PTSD and CPTSD

- A traumatic event can be:

- a recent, single traumatic event (e.g., car crash, violent assault)

- a single traumatic event that occurred in the past (e.g., a sexual assault, the death of a spouse or child, an accident, living through a natural disaster or a war)

- a long-term, chronic pattern (e.g., ongoing childhood neglect, sexual or physical abuse)

- A person who has experienced a traumatic event might develop either simple or complex PTSD:

- Experiencing a single traumatic event is most likely to lead to simple PTSD.

- Complex PTSD tends to result from long-term, chronic trauma and can affect a person's ability to form healthy, trusting relationships. Complex trauma in children is often referred to as "developmental trauma."

-From Canadian Mental Health Association (2023)

There is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and also complex PTSD (CPTSD), which is not yet in the DSM but likely will be soon. PTSD generally relates to a single traumatic event like a car crash or assault. CPTSD usually involves a chronic pattern of cumulative unsafe environments, often developmental trauma from ongoing abuse or neglect.

Both PTSD and CPTSD lead to very similar manifestations in the mind and body. However, CPTSD can be more difficult to treat given the need to process numerous cumulative events rather than a single incident.

DSM Criteria

- Intrusive and distressing memories and avoidance of them

- Distressing dreams

- Dissociation – experiencing the event as happening again

- Prolonged stress to cues which remind them of the event with marked intense physiological reactions – avoidance of these cues

- Persistent distorted negative cognitions about self and the world

- Difficulty remembering portions of the event

- Self blame

- Persistent negative emotional state, difficulty experiencing positive emotions

- Diminished interest in significant activities

- Feeling detached from others

- Marked irritability/frustration

- Exagerated startle response

- Problems with concentration

- Sleep disturbance

(Pai et al., 2017)

The DSM-5 criteria for PTSD provide some indicators to be aware of without assuming a diagnosing role. As OTs, we don’t diagnose but can be attuned to signs suggesting a client may be struggling with PTSD or trauma. Being knowledgeable supports appropriate response and understanding.

Some examples are if a client describes intrusive thoughts about their trauma, seems detached during certain discussions, or has exaggerated startle responses. Other clues are avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, hypervigilance, negative thoughts or beliefs, irritability, and sleep disturbances. Checking for PTSD red flags allows us to provide sensitive care.

Intersectional and Collective Trauma

- “Clinical and epidemiological studies show that children of parents who experienced trauma are at risk of developing emotional, cognitive, and behavioral problems including post-traumatic symptoms, depression, anxiety, hyperactivity, and conduct disorders.” (Grand & Salberg, 2021)

- “LGBTQ youth are disproportionately impacted by multiple forms of childhood trauma, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, dating violence, sexual assault, and peer violence.” (McCormick et al., 2018)

- “COVID-19 is a new type of (collective) traumatic stress that has serious mental health effects.” (Kira et al., 2021)

It is also important to consider generational, intersectional, and collective trauma. Generational trauma is passed down through families, often seen in marginalized communities. Trauma alters genetics, predisposing descendants.

Intersectional trauma recognizes factors like race, gender identity, or sexual orientation can lead to traumatic experiences like abuse and assault at disproportionate rates.

Collective trauma refers to society-wide events like COVID-19 that were distressing for many. While not everyone meets PTSD criteria afterward, collective crises can act as tipping points, triggering those predisposed.

Considering sociocultural contexts provides an essential perspective when evaluating clients holistically.

PTSD Screening

In the past month, have you...

YES / NO

YES / NO

YES / NO

YES / NO

YES / NO

(Prins et al., 2016)

A short PTSD screening tool containing five questions can help gauge if clients are experiencing common symptoms of post-traumatic stress without assuming a formal diagnostic role. Assessing for factors like nightmares, hypervigilance, emotional detachment, and more allows for recognizing functional issues like sleep disruption or relationship withdrawal that may benefit from occupational therapy support.

Suicidality Response

If a client endorses thoughts of self-harm, I always follow up to determine if they have an intention and a specific plan. Passive thoughts are less concerning than active ideation with intent and planning, which warrant additional professional support such as calling a crisis line or physician. For any suicidality, I create a safety plan listing coping strategies, reasons for living, safe contacts, and resources.

Body and Brain with Trauma

Amygdala becomes more overactive, and the frontal cortex less active.

They may have changes in hearing (Hyper-acusis or sensitivity to low tones).

Their ventral vagus nerve becomes less active (HRV impacts and difficulty relaxing).

Hyper-arousal of the nervous system

Chronic symptoms: Pain, fatigue, etc.

In overwhelming threat, our autonomic nervous system commandeers control while logic shuts down. The amygdala becomes overactive, increasing fear response and releasing stimulating neurochemicals like cortisol and adrenaline.

Afterward, if the nervous system stays in overdrive, these survival reactions persist, becoming maladaptively encoded. fMRI studies show PTSD patients have enhanced amygdala activity with diminished frontal cortex function, equating to more fear and less thinking.

The vagus nerve, a key nerve regulating the parasympathetic nervous system, becomes less active. This reduces its breaking effect which would normally return the body to homeostasis after stress response.

People with PTSD often have sensory sensitivities, like discomfort with noises reminiscent of the trauma setting. They exhibit chronic hyperarousal and symptoms like pain, fatigue, and dissociation. Trauma disrupts the mind-body link, decreasing interoceptive awareness.

Understanding these physiological effects provides context when treating PTSD through an OT lens.

Understanding Trauma with Polyvagal Theory

- Our alarm system and survival responses get stuck “on” and are difficult to turn off.

- Our nervous systems work like a staircase/ladder: Fawn, Flight, Fight, and Freeze. These autonomic responses can become “stuck” in the body.

Polyvagal theory proposes our nervous system works like a ladder, prioritizing safety responses from easiest to most dangerous. Fawning is top, involving appeasing a threat to mitigate the danger. Next is fleeing if unable to pacify the threat. The last resort is fighting, or direct combat. Freezing is the ultimate response when unable to escape, appease, or battle.

In PTSD, these reactions grow sensitized, coloring situations as far more precarious than reality. The amygdala hijacks executive functioning, spuriously activating defense modes. A treatment goal is dampening this hypersensitivity so clients respond with flexibility versus automatic overreactions.

The good news is neuroplasticity allows the rewiring of neural pathways engrained by trauma toward safety instead of peril. As the brain is molded maladaptively initially, so too can it be sculpted in healthy directions using goal-directed techniques.

Distinct OT and Counseling Roles

- Occupational Therapy

- Occupational therapy practitioners are qualified mental health professionals who assist people experiencing barriers to engage in meaningful roles and occupations to increase their participation, health, and wellness (American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2010, 2014).

- Identify triggers, maladaptive behaviors, and functional coping strategies

- Help clients increase their participation in their meaningful roles and occupations through adaptations, gradual exposure, and identifying specific barriers and tools

- Counseling

- Processing, discussing the past

- Working through emotions related to what happened

- Techniques like EMDR for processing

- Tools and skills for coping

Let’s clarify the distinct roles of OT and counseling for trauma, as there is occasional friction about scope. OTs are qualified mental health professionals per AOTA, experienced in addressing barriers to meaningful occupations. We increase participation and wellness through functional interventions.

OT takes a pragmatic approach using a toolkit to re-engage with life. We identify triggers and maladaptive behaviors while building functional coping through graded exposure, adaptations and specific modalities. I see counseling as more processing-oriented, working through events verbally and utilizing techniques like EMDR that are outside our scope.

Both disciplines offer value through differing lenses. An interdisciplinary team can optimize outcomes versus any one provider independently. OT’s function-based strengths complement counseling’s processing approach to fully support client needs.

General Trauma Informed Care

- Important to avoid re-traumatization: Discuss how you can help them feel safe early on

- Lots of validation!

- Environment: clear view of exits, noise levels low, welcoming language on signs

- Strengths-based approach & empowerment

- Maintain regulation yourself

- Know how trauma impacts the mind/body and how to recognize it

- Involve clients: Give lots of choices!

-SAMHSA (2014)

When working with those with trauma, trauma-informed care is essential to avoid re-traumatization. After introducing myself, I ask what each client needs to feel safe and avoid known triggers. Assuming most people have some trauma exposure promotes universal sensitivity.

Validation is key, even if not validating a detrimental behavior itself. Separating the person from action allows for acknowledging underlying emotions without endorsing maladaptive coping. For example, an alcoholic binge doesn’t warrant praise, but the vulnerability prompting it does deserve compassion.

Additionally, considering aspects like clear sightlines, controlled noise levels, and positive environmental signage fosters security. Empowerment through choices, collaborative goal-setting and strengths-based language also nurtures agency and capability.

Finally, personally maintaining regulation is crucial so as not to absorb clients’ dysregulation or improperly match their distress by losing professional boundaries. Providing an external sense of safety without merging affect is essential for productive processing.

Recognizing Trauma Responses

Understanding how trauma manifests in mind and body, along with recognizing associated responses, allows us to serve clients optimally. My social media contains many examples of differentiating trauma reactions like fight, flight, freeze, or fawn if you’d like to learn more after today. The key is identifying how trauma colors one’s nervous system, relationships, and engagement.

Strategies for Trauma

Next, I’ll review some strategies you can start applying immediately with clients experiencing trauma responses. Please note I’m introducing treatment approaches at a surface level, so pursuing additional training is recommended to gain confidence and depth.

Basics

- Therapeutic relationship

- Sleep hygiene

- Routine and meaningful engagement in activity

- Diet and exercise

It’s important not to underestimate the basics - therapeutic rapport, sleep hygiene, routine, activity engagement, diet, exercise, and more. These OT fundamentals comprise a critical foundation.

DBT Skills

- Nightmare protocol

- STOP: Stop, Take a breath, Observe, Proceed

- TIPP: Temperature, Intense Exercise, Paced breathing, Progressive muscle relaxation

- Mindfulness? Abreaction possible- use with caution

- Distraction techniques – This is also sensory modulation. I make a list with my clients of safe healthy distractions.

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) contains many relevant techniques, included in publicly available DBT handbooks online. DBT is a first-line treatment for conditions like borderline personality disorder and mood dysregulation based on ample research.

One DBT skill I use frequently is the nightmare protocol, as nightmares are common in PTSD. The client writes out their recurring nightmare, then changes the ending to something safer on the other side of the page. They read this revised version repeatedly before bed to provide an alternate narrative. This can substantially reduce distressing dreams.

The STOP skill reminds clients to stop, take a breath, observe, and proceed mindfully when escalated. This creates space between stimuli and reactions, enabling reasoned responses. Additional DBT modules like distress tolerance and emotional regulation can help trauma survivors as well.

Mindfulness merits caution as relaxation may prompt emotional flooding in some PTSD patients. However, structured programs designed for trauma may effectively teach skills like recognizing triggers, tolerating distress, and self-soothing. Mindfulness is an area requiring nuance based on client responses.

When emotions exceed a client’s window of tolerance, receiving psychoeducation is unlikely. Distraction is often more pragmatic in extreme distress via sensory techniques like weighted blankets, lavender, textured objects, music, or visualization. Having clients compile personalized sensory-based coping tools they can access when overwhelmed provides resources to mitigate fight/flight. Distraction shifts attention to navigate intense reactions.

Nervous System Regulation/Somatics

- Horse breath

- Physiological sigh

- Shaking

- Yoga or a movement class

- Use of eyes: Periphery, relaxing

- Opening posture

- Valsalva maneuver

- Reviewing triggers and glimmers

Somatic or body-based practices help communicate safety to the nervous system implicitly through sensation versus cognition. Examples include breath techniques like horse breath and physiological sighing which elicit relaxation.

Shaking out muscles discharges activation. Yoga connects mind and body. Ocular techniques like covering or softly palming the eyes promote security since vision alerts us to danger. Expanding peripheral gaze signals safety through wide environmental appraisal.

Opening posture contradicts defensive stances we adopt when threatened. And interventions like splashing cold water on the face or bearing down can jolt the vagus nerve to restore equilibrium.

Bottom-up sensory approaches foster stability efficiently by shifting physiology itself, not just thoughts. polyvagal-informed strategies work directly with nervous system wiring.

ACT-Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Exploring values with a client- values sheet

- We don’t like the experience but we accept it- serenity prayer

- Primary suffering is defined as the initial injury – it is inherent in living. Secondary suffering as the reaction to the initial injury. Primary suffering is not a choice; secondary suffering is.

- Defusion: “I notice I am having the thought that…”

- This is a practice!

Acceptance and commitment therapy or ACT employs acceptance to reduce secondary suffering layered upon primary pain. By acknowledging distress without compounding it with self-judgment, clients relate to difficulties as transitory experiences rather than personal failings or immutable realities.

Exploring values helps identify intrinsically meaningful activities to re-engage in. Acceptance and values synchronization promotes engagement and purpose.

CBT- Exposure Therapy and Behavior Activation

- Exposure therapy: Start with the least distressing thing related to the exposure. Expose them to it while using lots of grounding techniques. Gradually build up.

- Behavior activation: What is the first step of an activity? Have them do that first.

- Thought challenges: Download a “thought challenge sheet” and “common thought distortions” and go through this with a client, coming up with alternative, more realistic thoughts.

Cognitive behavior therapy highlights links between thoughts, feelings, and actions. Automatic negative thought patterns stemming from learned helplessness or misappraisal can be modified through awareness and disputation tactics. This builds more balanced thinking and mitigates mood or behavioral consequences. For example, collaborative identified thinking traps like black-and-white reasoning allow clients to challenge engrained cognitive distortions. Realistic perspectives create psychological flexibility.

Exposure therapy progressively confronts feared stimuli through hierarchical desensitization. This behaviorally demonstrates previously overwhelming situations can be tolerable and mastered.

Combined with coping skills training, exposure fosters empowerment and self-efficacy. It demonstrates PTSD can be managed, not just endured.

Multipronged top-down and bottom-up protocols address mind and body for comprehensive healing. Just as trauma affects systemic functioning, so too must recovery.

Strategies for Various Levels of Distress

- Green zone: Connect with loved ones, engage in pleasant activities, build mastery, move the body, write gratitudes

- Yellow zone: Regulation techniques, challenge thoughts, meditate

- Red zone: Distractions, safety plan/call for help, listen to music

Here are some suggestions for distress tolerance strategies at different levels:

When in the green zone, with distress levels between 0-4 out of 10, practice gratitude, get moving, engage in a hobby, write in a journal, and listen to uplifting music.

In the yellow zone, with distress from 4-7 out of 10, use grounding techniques, practice deep breathing, go to your calm place mentally, challenge thoughts, practice mindfulness or meditation, and take a break.

For the red zone, with distress levels from 7-10 out of 10, use distraction, call a friend, use your safety plan, listen to music, splash cold water, exercise intensely, and hold an ice cube.

Note About Suicidality

- I always like to do PHQ-9 with my clients in the beginning and see how they answer the suicidality question. Check in often.

- SAFETY PLANS ARE ESSENTIAL:

- Warning signs:

1. Soothing Activities:

2. Reasons For Living:

- A chance for a life worth living

- Things are really tough now but there is a lot you could miss out on

- Life CAN get better than it is now

- Hurt or worry it would cause loved ones

3.Environmental safety

4.People to Call:

5.Resources:

- Crisis Line (1-800-784-2433) 24 hours

- 911 OR Take yourself to the closest hospital emergency dept if all of the above does not reduce suicidal thoughts

I always administer the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire with clients, which asks about thoughts of being better off dead or self-harm. If a client affirms this item, I follow up to assess intention and plan.

Sometimes suicidal thoughts are passing, like thinking one's family would be better off without them. However, if a client expresses the intention to act, like planning to harm themselves using specific means, urgent intervention is required. This may involve contacting a crisis line together, their doctor, or emergency services depending on risk severity. Passing thoughts may not require as intensive a response, but still warrant a safety plan listing coping strategies, reasons for living, securing environment/objects, emergency contacts, and resources.

For any suicidality, a thorough risk assessment and tailored response is crucial - either getting help or creating a robust safety net. My role is to keep the client safe first and foremost. Suicidal thinking must be taken very seriously.

Recommendations

- Refer out for CPT (cognitive processing therapy), EMDR, hypnotherapy, internal family systems, etc.

- Books like “The Body Keeps the Score,” “When the Body Says No,” “Healing Trauma,” “Trauma Treatment Toolbox,” “In the realm of Hungry Ghosts,” and “What Happened to You?: Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing”

- The Trauma Research Foundation has a lot of resources

- Self-Hypnosis or EFT on YouTube

- My Tiktok/Instagram (@uplift_virtualtherapy insta and upliftvirtualtherapy TT)

Here are some additional recommendations and resources for treating trauma. I would refer clients out for evidence-based therapies like cognitive processing therapy (CPT), EMDR, or hypnotherapy. As occupational therapy practitioners, we can pursue training in these approaches or collaborate with providers who specialize in them.

Great trauma-focused books to recommend include: "The Body Keeps the Score," "Trauma and Recovery," "The PTSD Workbook," "The Complex PTSD Workbook," and "Waking the Tiger."

The Trauma Research Foundation and Sidran Institute offer many educational resources for clinicians. Clients can explore self-hypnosis or the Emotional Freedom Technique through self-guided tools on YouTube.

Check out social media like TikTok and Instagram which have hundreds of videos on trauma responses and coping skills. Connect on there for additional resources.

Conclusion

Building a toolkit of trauma-informed referral sources, materials, and continuing education is important, as trauma treatment requires specialization beyond general therapy skills. Please reach out if I can help identify any other evidence-based trauma practices or providers.

I’m happy to take any emails to clarify recommendations after today’s session. Please also feel free to reach out to me through my social media for supplementary materials on understanding and responding to trauma.

Questions and Answers

Did you address spirituality? What experience do you have with that and your scope of practice?

Spirituality is something that I consider a lot with all my clients. It's one of my questions on the intake form. What is your purpose in life? Do you have any spiritual affiliations? I think it is important to include that.

There is a technique that I didn't go into in this course called resourcing. With resourcing, you're imagining a presence or a situation that feels very safe. For a lot of people, we might use God or something from their religion or spirituality that feels very safe for them. When they imagine that presence, that helps to regulate them. For people who don't believe in God, we might use their grandparents, sitting by a waterfall or something like that.

I definitely incorporate spirituality into the practice.

How can OT affect mass shooting PTSD?

It is a rough thing that has been happening in the country, and it's going to impact a lot of people, both primary, the people who've been affected by it directly, and secondary, the people who think about their kids going to school and not being sure if their kids are safe.

I would treat each client individually and go through some of the techniques that you've learned today.

Is there a role for OTA in this area of practice?

Yes, there definitely is especially with exposure therapy and stuff like that. The plan that the occupational therapist has laid out can be something that you can do together. The meditation and the nervous system regulation techniques are good for literally any healthcare practitioner to know. One, for regulating your own system, and two, for helping clients regulate if you notice that they're becoming dysregulated.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (3rd ed). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68, S1–S48. doi:10.5014/ajot.2014.682006

Canadian Mental Health Association (2023) Trauma. https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-illness-and-addiction-index/trauma

Grand, S., & Salberg, J. (2021). Trans-generational transmission of trauma. Social trauma–an interdisciplinary textbook, 209-215.

Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H. A., Ashby, J. S., Elwakeel, S. A., Alhuwailah, A., Sous, M. S. F., ... & Jamil, H. J. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 traumatic stressors on mental health: Is COVID-19 a new trauma type. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-20.

McCormick, A., Scheyd, K., & Terrazas, S. (2018). Trauma-informed care and LGBTQ youth: Considerations for advancing practice with youth with trauma experiences. Families in society, 99(2), 160-169.

Prins, A., Bovin, M. J., Smolenski, D. J., Mark, B. P., Kimerling, R., Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., Kaloupek, D. G., Schnurr, P. P., Pless Kaiser, A., Leyva, Y. E., & Tiet, Q. Q. (2016). The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5(PC-PTSD-5): Development and evaluation within a Veteran primary care sample. (PDF) Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31, 1206-1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606

Pai, A., Suris, A. M., & North, C. S. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, change, and conceptual considerations. Behavioral sciences, 7(1), 7.-016-3703-5

SAMHSA (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. Available at:

https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884.

Citation

Dureno, Z. (2023). Post traumatic stress disorder: Understanding and treatment from an OT perspective. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5626. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com