Emily: I am really excited to be here. I taught a course on typical brain development, and now I want to go over primitive reflexes and how they impact development. There are going to be some areas that I review from the previous course.

My Cousin Jack

Before we jump into the course, I want to talk a little bit about my cousin Jack. He had a lot of different developmental problems growing up and went to a lot of different specialists. He received several different diagnoses like ADHD, sensory processing, dyslexia, learning disabilities, and those are just the ones that I remember. His mother took him all over the country trying to find something that would help him. The thing that makes the biggest difference for him was working with a neurodevelopmental delay therapist, or NDD therapist in Colorado named Deanna Buck. She tested his reflexes and created a specific treatment program for him.

Before treatment, he was always very withdrawn and had really poor emotion regulation. He had meltdowns all the time. He was also anxious and withdrawn with very poor social skills. He struggled in school constantly. As he went through this program, all of these things start to kind of go away or become much easier for him. He blossomed. He was able to get through school, make friends, and he developed much better emotion regulation and general overall life skills. I remember one time he was riding up the escalator with his mom. It was not until they were about halfway up when his mom said, "Hey Jack, you're riding on an escalator!" This was the first time that he had ever ridden an escalator without panicking.

My Background

Because I got to see how successful Jack was with this type of treatment, I knew, as a pretty young teenager, that I wanted to be able to offer families the same thing.

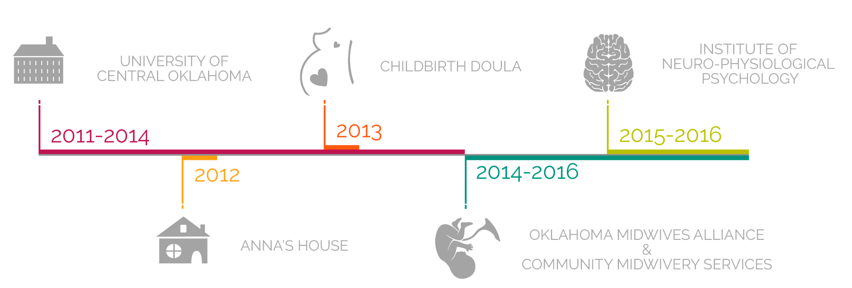

Figure 1. My background.

I went to college at the University of Central Oklahoma and received a bachelor's degree in psychology. I also became a certified midwife's assistant with the Oklahoma Midwives Alliance. Then, I got a postgraduate degree in neurodevelopmental delay from the Institute of Neuro-Physiological Psychology. Again, this whole process started with Jack.

Once I was in college, I decided to take a summer internship with Anna Buck, who is the owner of Anna's House. She is the therapist that helped my cousin so much. I spent a summer in Colorado with her. While I was there, her daughter was pregnant, and she was using a midwife for her prenatal care and delivery. I knew a little bit about this practice as my mother used a midwife with me. I was really curious about their role, and I asked a lot of questions. It is holistic and preventive care offered to women during pregnancy and labor, and it helps to prevent a lot of the neurological problems.

During my college psychology classes, I learned how pregnancy and prenatal development impacts the brain development and the nervous system. However, I had not really learned anything about labor and birth and how that can have an impact on brain development. I left that internship really curious and wanting to learn more. In my senior year of college, I decided to become a childbirth doula. A doula is somebody who provides physical and emotional support to women during labor. This is not the medical side, but the practical side of labor and birth, and how to help people through it. I worked as a childbirth doula through my last year of college, and again, I left college wanting to know more. I wanted to know more about the medical side of things and how that impacts brain development.

Thus, once I graduated, I enrolled in the Oklahoma Midwives Assistant course. Then, I enrolled a year later at the Institute of Neuro-Physiological Psychology and got a postgraduate degree in neurodevelopmental delay therapy. Once I graduated from there, I opened a practice called Early Roots where I work with children who have retained reflexes and specific types of neurological delays.

Brain Development

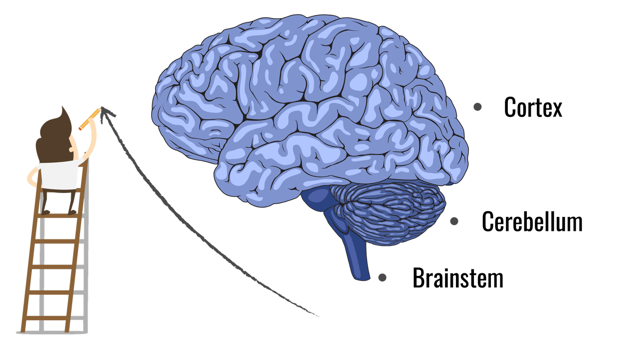

The first thing I want to talk to you about is some very basic principles of brain development. The brain develops both physically and functionally from the bottom up as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Brain development sequence.

The lower structures of the brain begin forming and maturing first, and then the higher structures of the brain mature last. You can see this pretty easily when you look at fetal development. The first thing that forms in the spinal cord, the brainstem, the cerebellum, and finally the cortex.

At birth, a baby's brain is very immature. The brainstem is the most mature, and it regulates most of a baby's functioning. The brainstem is responsible for automatic functions like breathing, heart rate, and primitive reflexes. This is really important early on in development because at the time of birth the rest of the brain is really immature. As the baby begins developing during that first year, the brain stem is going to begin relinquishing more and more control as the rest of the brain takes over. The brain stem fully matures within the first year although it is mostly by birth.

Movement is Key

The last part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex at the very top, is not fully mature until a person is in their mid 20's. This whole process of brain maturation takes place through movement, use, and interaction with the environment. It is a use it or lose it type phenomenon. As babies receive information from the environment through their senses, their brain responds to it, and they react and move. It is a back and forth bi-directional exchange of information that creates changes in the brain and in the body systems.

It is also important to remember, that as babies grow and develop new physical skills, they begin to have more control over their body. Their brain stem is beginning to relinquish more and more of that control to higher portions of the brain. It is really easy to focus on the brain alone and forget that it is this connection and interaction with the body that is extremely important for growth and development. They do not function or work together in isolation. They work together, and they are completely connected and interdependent.

The Developed Brain

When this whole process of maturation works properly, you should have a brain that functions a lot like a theater. The upper level of the brain functioning is a lot like a stage. Using this metaphor, you should only notice what is going on on the stage. This part of the brain focuses on learning, planning, rational thinking, and those types of things. The lower sections of the brain, the brain stem, and the cerebellum, should work like the backstage crew. They are working really hard behind the scenes to make sure that everything is running smoothly.

Think Holistically

You need to think holistically. I appreciate this quote from Sally Goddard Blythe.

“Children’s difficulties do not exist in specialist departments; they exist within the context of the whole child.”

- Sally Goddard Blythe

She is one of the founders of the institute where I did my postgraduate work. It is easy to focus on one specific problem or one specific symptom, and then forget that we have a whole child with lots of different things going on.

Primitive Reflexes

- Develop in utero

- Help with the birth process and help the infant survive outside the womb

- Disappear during the first year

- Replaced by Postural (adult) reflexes by age 3 ½

- Provide reliable indicators of the maturity of the central nervous system

- They are very powerful and can interfere with the development and function of the rest of the brain

Infants develop a set of reflexes in utero as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Primitive reflexes: palmar, plantar, and Moro.

They help them during the birth process, they help them to adapt to being outside of the womb in a totally new environment, and they help them to survive during the first year or so after birth. These reflexes should begin to disappear after birth and should be gone within the first year. They are replaced by postural or adult reflexes by about the age of three and a half. These reflexes, when you look at them specifically in older children, provide good indicators of the maturity level of a person's nervous system. These reflexes develop and inhibit in a very orderly and systematic way.

In my practice, I focus on them so much because they are very powerful and can interfere with the development and the function of the rest of the brain. The brainstem is what regulates primitive reflexes. Primitive reflexes can interfere with signals going to the rest of the brain. When primitive reflexes are not extinguished, this can impact lots of different areas of brain development and function.

Moro Reflex

Definition

The Moro reflex is the most common primitive reflex that I see in my practice. It is also the one that causes the biggest problems in children. This reflex is elicited by any sudden change in the environment or any sudden change of the five senses of light, touch, sound, taste, smell, or any sudden loss of head support. It is typically elicited when the head extends back and tilts below the level of the spine. This causes the baby's sympathetic nervous system, or fight-or-flight mode, to kick in. They take in a deep breath, their head pulls back, their arms extend out, and then they grasp forward (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Moro reflex.

Purpose

It is important after birth for several reasons. They use a lot of these reflexes to help not only develop good motor coordination and muscle tone but also to keep them safe and alive while they are in that process.

- Helps stimulate breathing after birth

- Helps protect baby’s airway

- Alerts caregiver to possible danger

- Stimulates the nervous system

It helps to stimulate breathing after birth and forces that first breath of life. It also helps to keep their airways clear after birth. Babies have very little control over their body movements when they are first born. The Moro helps to prevent their airways from becoming blocked. It can alert their caregiver to possible dangers. Finally, it helps to stimulate their nervous system.

There is also a big difference between the Moro, or the infant startle reflex, and an adult startle reflex. The adult startle reflex has connections to upper parts of the brain and is not as sensitive. If somebody were to drop something on the ground like a glass, you most likely would jump and would orient your attention to whatever that was. You would make a really quick evaluation of that situation and your body would determine whether or not and that was something dangerous. This determines whether you should fight, or flee, or calm down. This does not happen with the Moro. There is no connection between higher levels of the brain. There is no orienting towards whatever it is or an evaluation conducted. With the Moro, they are immediately put into a fight-or-flight response. Smaller noises, smaller lights, smaller touches, and things like that can elicit this reflex.

Moro Connections

In order to understand this a little bit better, we have to look at the two like modes of the nervous system. The first is the sympathetic nervous system or the fight-or-flight system. It is responsible for responding to stress and to danger. The opposing mode is the parasympathetic nervous system. This is your rest and digest mode, and it is responsible for maintaining homeostasis. Children, who have a retained Moro reflex, spend a lot more time in their sympathetic state than they should. Most of the time, people should be in their parasympathetic mode.

Being in fight-or-flight mode for an increased time can have a huge impact not just on their emotional well-being, but on their physical well-being as well. I will go into a little bit more detail on that a little bit later. Whenever your sympathetic nervous system is activated, your body releases stress hormones, cortisol, and adrenaline. Additionally, blood is diverted away from non-essential body systems, like your digestive system, and it is diverted to large muscle groups to help prepare you to either fight or flee.

The Moro reflex also has connections to several different systems.

- Arousal system

- Sensory system

- Immune system

- Digestive system

Obviously, one is the arousal system. Other areas include the sensory, immune, and digestive systems. When you have a child that has a retained Moro, they are exposed to a lot more stress hormones than they should be. This can take a toll on their immune system. They also spend a lot more time in that fight-or-flight mode which can have an impact on their digestive health as well.

You also have to think about what else is going on developmentally at the time when the Moro is present. For example, in early infancy, their vision is very peripheral. Their visual attention tends to be drawn to any little changes in their environment. They are unable to focus their visual attention and tune out irrelevant information. This is normal and adaptive in early infancy, but as they develop, their vision should become more centrally focused. They should be able to tune out irrelevant information in their peripheral vision. Many children who have a retained Moro are very stimulus bound. Their visual attention tends to function more like that of an infant, and they have a really hard time focusing their vision centrally and tuning out irrelevant visual stimuli.

Another thing that happens, as the Moro reflex is inhibited, is the acoustic stapedius reflex. Whenever an infant experiences a particularly loud sound, the muscles in the ear contract to dampen the sound and prevent discomfort or damage to the ears. This should develop before the infant begins to vocalize because it also helps to dampen the sound of one's own voice. Often, children, with a retained Moro, have not developed this reflex so not only are they more sensitive to auditory information, but they experience noises louder than a typical person would. They may even have trouble tuning out the sound of their own voice.

Symptoms

Let's look at some of the symptoms.

- Overreactive

- Hypersensitive

- Anxiety

- Hyperactive

- Visual-perception problems

- Poor impulse control

- Emotional immaturity

- Motion sickness

- Immune issues

- Stimulus bound

- Controlling behavior

- Inflexibility/dislike of change

These are some of the symptoms that I see. Children tend to be overreactive. They have a much stronger physiological reaction than they should have to certain things. They are hypersensitive and are much more sensitive to sensory input. They can be anxious as these children are living in a world that is too loud, bright, and scary. They do not have a way to regulate their emotions or their responses to their environment. This creates a lot of anxiety and frustration. Some kids are hyperactive and this tends to be a coping mechanism. They use their fight-or-flight response like an adrenaline rush. They may get really hyped up and excited, and they will run around and have a hard time calming down. It may seem like they are just really excited, but what is happening is that they are being startled.