Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, The Pruning Effect On The Teenage Brain (It’s Not Just Hormones), presented by Tere Bowen-Irish, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to differentiate between a developing teen brain and an elementary student’s brain.

- After this course, participants will be able to evaluate what parts of the brain activate and deactivate during adolescence.

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze and apply specific considerations for evaluation and treatment during adolescence.

Introduction

- Today’s topic (I’m hoping) will help you better understand pre-teen and teen behaviors based on relatively new neurodevelopmental theories.

- Keep in mind, that their frontal lobes are not fully developed, and other parts of their brain are going through many changes. This starts around age 12 and finishes in the mid-to-late twenties.

Greetings, everyone. I'm delighted to be back here with you. Today, I want to delve into a topic that holds a special place in my heart – teenagers. Currently, my engagement with this fascinating age group is through teaching yoga and mindfulness in a middle and high school setting. In navigating this journey, I've come across some insightful research that I believe will be equally enlightening for you as it continues to shape my own understanding.

Let's commence with a brief mindful moment. I've observed that incorporating this into sessions with teens helps ground them. Whether you choose to close or avert your eyes, place one hand on your heart and the other on your belly. Simply observe your breath without altering it in any manner. As we embark on this session, my goal is to share an hour of valuable insights. Recognizing that you may have rushed here from other commitments and still have a busy afternoon ahead, let's collectively set aside those distractions and be fully present for the next hour. Take a deep breath in, allowing it to escape through your mouth.

The essence of our discussion today revolves around equipping therapists and educators with a deeper comprehension of pre-teen and teen behaviors. Neurodevelopmental theories, a relatively recent addition to our understanding, have been gaining prominence over the last couple of decades. It's crucial to bear in mind that despite their seemingly mature appearance, teenagers are not fully developed in their frontal lobes. Various aspects of their brain are undergoing significant changes, a process that initiates around the age of 12. As we explore the content, you'll encounter differing opinions among researchers, some suggesting an onset at 10, others at 11, and a few extending the timeline to around 27 for complete myelination and frontal lobe development. I present these perspectives as part of the ongoing discourse in the field, urging us to consider the span from approximately age 12 to the mid to late 20s when addressing the complexities of teenage development.

Myths

- Were any of these myths on your list? (If we believe them, they can be disempowering for us and the teens we treat.)

- Raging hormones

- Out of control, lazy, crazy

- Risk-taking and impulsiveness predominate

- It’s a terrible time in life

- Development is on autopilot

- Disrespect for boundaries

- They only live in the moment, with no concern for the future

- Erratic in reactions and emotions

- They hate and dislike their parents and teachers. They don’t care how they are viewed by them

As we explore prevailing myths surrounding teenagers and consider the narratives we've encountered from others or scripts we might use, the discourse often revolves around clichés. We frequently hear about raging hormones, perceptions of being out of control, laziness, and a general disposition toward impulsivity. The prevailing notion is that adolescence is a tumultuous period, marked by development on autopilot, where individuals grapple primarily with the challenges posed by their hormones. There's a pervasive belief that teens inherently lack respect for boundaries, living solely in the moment with little concern for the future. The narrative continues with characterizations of teenagers as erratic, overly emotional beings who harbor disdain for their parents and teachers, indifferent to how they are perceived by authority figures.

It's crucial to recognize that these myths, whether consciously or not, can be disempowering. This holds true not only for us, as individuals involved in therapeutic work, but also for the teenagers themselves. The impact extends to how they perceive our perspective on them. Dispelling these myths is integral to fostering a more constructive and empowering environment for both parties involved in the therapeutic relationship.

- Today, we will spend some time debunking those myths. Here are some interesting facts to ponder.

- From the book, The Teenage Brain by Frances Jenson. “Prospective memory which is the mind’s ability to hold an intention to perform a certain activity at a future time, initially comes into play between 6 and 10 years and doesn’t develop much between 10 and 14 years old”.

- Dr. Daniel Siegel suggests that the adolescent period is a necessary period of development to move toward adulthood. It’s a drive to pursue the uncomfortable, unsafe, and uncertain. The reward circuit of the brain changes, and the adolescent seeks novelty. There is a true dopamine change. Hyper-rational thinking can be displayed. The adolescent tends to lean towards the exciting parts of life that may be dangerous. This period goes into the 20s.

Let's dedicate some time to dispelling these myths, and here's where the debunking begins. In Frances Jensen's book, "The Teenage Brain," the concept of prospective thinking, the mind's ability to hold intention and perform specific activities, is discussed. Surprisingly, this ability peaks between the ages of 6 and 10. However, developmental progression in this skill doesn't show significant growth between the ages of 10 and 14. This challenges the expectation that cognitive abilities would naturally improve during this period, suggesting that we might anticipate more development than is actually occurring.

Dr. Daniel Siegel, whose insightful books I highly recommend exploring, proposes that this period is crucial for the transition to adulthood. It's characterized by a drive to embrace discomfort, uncertainty, and novelty. What's intriguing is that the reward circuits in the teenage brain undergo changes, accompanied by a shift in dopamine levels. This can lead to what Dr. Siegel terms as hyper-rational thinking. Adolescents are inclined toward the more thrilling aspects of life, often finding themselves drawn to taking risks that may be perceived as dangerous. This pursuit of excitement and the associated risk-taking behavior can extend well into the 20s, marking a significant and necessary phase in the journey toward maturity.

- Consider this if emotional reactiveness is present:

- A study by Robert McGiven, a neuroscientist, found that there was an overall increase in nerve activity at the pre-frontal cortex at the onset of puberty that correlates with difficulty in recognizing other people’s emotions. This ability does not return until 18 years of age. The result is poor reading of social situations, confusion with emotional situations, and emotional dysregulation. Teenagers often react to a feeling or a situation impulsively.

- Brain and Cognition (vol. 50, p173) Oct. 2. Study taken from Tools for Teens by Diana Henry

Consider the aspect of emotional reactivity, as elucidated by Dr. Robert McGiven. He notes an overall increase in nerve activity in the prefrontal cortex right at the onset of puberty, affecting the ability to recognize other people's emotions. This concept resonates with my past exposure to Diana Henry's discussions on the topic. In practice, I've encountered numerous instances where teenagers misinterpret my facial expressions or the meaning behind a word, reacting emotionally to a perception that differs from my intended communication. The documented evidence in this realm suggests that teenagers often struggle with accurately reading social situations, leading to confusion in emotional contexts and difficulties with emotional regulation. Consequently, they tend to react impulsively rather than respond thoughtfully to feelings or situations.

Imagine the scenario of entering a cafeteria and grappling with the decision of where to sit. In this context, if the cues are not overtly clear, such as a direct invitation to join, teenagers may misread social signals. For instance, they might conclude, "Oh, they aren't really waving at me," missing out on potential connections due to an inaccurate interpretation of the situation. This underscores the challenges teens face in navigating the subtleties of social dynamics during this crucial developmental phase.

Teenage Brain Development

- Dr. Daniel Siegel has much to say about brain development during the teen years.

- He claims that many of us can be disgruntled by a teenager’s attitude, affect, and behavior. We may blame it on immaturity, hormones, or social disconnection.

- When in fact, the brain is going through an amazing change.

- The brain is pruning itself and, in fact, re-modeling itself.

Dr. Daniel Siegel provides valuable insights into the dynamics of brain development during the teenage years, shedding light on the attitudes and behaviors that can sometimes leave us disgruntled. While it's easy to attribute these changes to immaturity, hormones, or a social disconnect, Dr. Siegel redirects our focus to a fascinating transformation occurring within the adolescent brain.

According to Dr. Siegel, what may appear as challenging behavior is, in fact, part of an incredible process of change. He describes this phenomenon as a remodeling effect, aptly named "pruning." During this phase, teenagers are actively letting go of elements that no longer capture their interest or that they no longer wish to pursue. Simultaneously, they are forging new neuronal pathways, directing their cognitive resources towards pursuits that genuinely resonate with their evolving interests and passions. This restructuring is a crucial aspect of the adolescent journey, contributing to the formation of a more refined and individualized neural network that aligns with their emerging sense of self.

- Siegel uses the metaphor of a tree during our elementary years. During this time, the child is growing branches and leaves that represent generalized learning about many things.

- Recent neuroscience tells us, that type of learning changes during adolescence. During the remodeling, the brain prunes itself to specialize the brain, losing some leaves and even branches. The adolescent has the opportunity to explore what they are passionate about, “specializing,” as Siegel states. There is a use it or lose it principle. Myelin sheaths become more mature. Neuronal communication increases at a faster rate.

Dr. Daniel Siegel employs the metaphor of a tree to illustrate the developmental process during the elementary years. From the inception of formal education, children begin growing new branches on their cognitive tree, with each leaf representing generalized learning across various domains. However, as adolescence sets in, this learning dynamic undergoes a profound transformation. The brain engages in a remodeling process akin to pruning, shedding leaves and branches to specialize in certain areas. This specialization, termed by Siegel as "specializing," allows adolescents to explore and devote their energy to what genuinely impassions them.

What adds an intriguing layer to this process is the "use it or lose it" principle. As the myelin sheaths mature and facilitate faster neuronal communication, the brain becomes more adept at wiring and firing. However, if adolescents aren't exposed to activities that align with their interests, or if their daily routines are predominantly solitary without engagement in the broader community, school, family, or worldly activities, there's a risk of regression. Without the stimulus that comes from pursuing passions, the brain may lose some of its acquired abilities. This underscores the importance of providing adolescents with opportunities to explore and engage in activities that genuinely captivate their interest, ensuring the continual growth and refinement of their cognitive abilities.

Leonard's Story

- Leonard’s profile: Unpredictable, impulsive in words and actions, and negative towards authority figures. Tough to connect with... We started with service duties (Dr. Robert Brooks’ work), which in turn, led to the discovery of his passions.

Allow me to share a poignant story about Leonard, a student I had the privilege of working with at a specialized school for children facing challenges that hinder their success in public education. Drawing inspiration from Dr. Robert Brooks, renowned for his work on self-esteem, I was reminded of the profound impact of service duties in fostering a sense of acceptance and value.

One day, I learned from a teacher that Leonard, a 14 or 15-year-old, was struggling to settle down in the mornings. Taking a cue from Dr. Brooks' insights, I invited Leonard to assist me in setting up the yoga room - an activity I typically handled alone. Together, we laid out mats, adjusted lights, opened windows, and tended to the needs of the therapy dogs accompanying me. During this time, Leonard and I engaged in conversation.

It was during these exchanges that Leonard shared his deep desire to learn how to play the guitar. He had been exposed to it in music class but harbored uncertainty about his family's ability to afford both a guitar and lessons. Starting in September, our collaboration continued throughout the year. Leonard, now passionately involved, began giving me concerts, showcasing his newfound musical skills. Eventually, he secured regular guitar lessons, exploring artists he resonated with, and even putting on a small concert for his classmates.

This experience underscored the transformative power of recognizing and nurturing a student's passion. Through a simple conversation during service duty, Leonard's hidden talent and enthusiasm for the guitar emerged. Without that connection, this remarkable journey might have remained unknown to both of us.

Pruning, Cont.

- Siegel goes on to say that it is a time to notice what interests adolescents have. From there, encouraging them or providing opportunities to pursue and refine those interests.

- There are many leisure inventories available, as well as multiple intelligence testing which correlates with what one does for work in adulthood.

- Here are two links: one for Dr. Siegel’s lecture on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0O1u5OEc5eY) and one for multiple intelligence testing (free_multiple_intelligences_test_manual_version_L.xls (businessballs.com).

Building on Dr. Siegel's insights, adolescence becomes a crucial time for observing and identifying the interests of individuals, akin to the discovery of Leonard's passion for playing the guitar. As we actively encourage and create opportunities for teenagers to explore and refine these interests, we contribute to their process of specialization. To complement this approach, I often utilize leisure inventories and recommend watching Dr. Siegel's informative YouTube video on teenage development and pruning.

In addition, I find that administering a multiple intelligence test can be particularly enlightening. Many of the teenagers I work with, especially those in therapeutic settings, may not have had experiences that made them feel intelligent. Through these tests, they often discover areas where they excel, whether it be in music, linguistics, or another domain. This realization serves as a powerful catalyst, helping us uncover what truly ignites their passion and excitement.

Employing these tools not only aids in building relationships but also forms an integral part of the therapeutic process. By recognizing and nurturing the diverse intelligence and interests of teenagers, we empower them to explore and embrace their unique strengths, fostering a sense of accomplishment and self-worth.

What Else Do We Know?

- Emotional sparks occur, moody, irritable, or the excitement of passion.

- Social engagement is important…they move toward peers and away from parents…seen in mammalian evolution.

- Can be a sense of urgency to be with and fit in with peers.

- There can be a downside, forsaking morality when trying to fit in, risk, and danger.

- They seek out novelty, and trying new things can help grow their brain.

- Siegel talks about adolescents challenging the status quo. Their minds push the boundaries. This occurs in the second 12 years of life. They see their parents as fallible. They may be overwhelmed, but they may also become more innovative to move towards change.

Emotional sparks are a hallmark of adolescence, manifesting as moodiness, irritability, or heightened excitement and passion. Reflecting on our own teenage years, the potency of emotions often surfaces when familiar music evokes vivid memories. During this phase, the emotional brain takes center stage, imprinting experiences in a deeply emotive manner. Social engagement becomes paramount, leading teenagers to gravitate toward peers while distancing themselves from parents - an evolutionary pattern observed in mammalian development.

The adolescent journey is characterized by a sense of urgency regarding social connections, where missing a social event may feel like an irreversible disconnection. This heightened emotional state can lead to dramatic expressions. Simultaneously, the pursuit of novelty and a willingness to experiment with new experiences may lead to a downside, exposing adolescents to potential risks.

Dr. Siegel underscores the importance of working with adolescents to navigate this transformative period. Encouraging them to challenge their status quo, adolescents naturally push boundaries as they seek to define themselves. Acknowledging parents as fallible beings becomes a pivotal moment in their development. This realization, often an "aha moment," allows adolescents to step back, recognizing their parents as imperfect individuals who make mistakes and experience outbursts. Armed with this understanding, they gain the power to shape their own identity, consciously deciding the values and behaviors they want to embody and those they wish to avoid. This awareness becomes a cornerstone for their emerging sense of self.

Dan Siegel Books

- Siegel’s books, Mindsight and Brainstorm, focus on mindfulness, self-awareness, and exercises to aid in self-regulation.

- He does Mindsight exercises to increase brain integration. Focus is helping adolescents make connections that are deep with other people.

These are the books I referred to in our discussion. As an avid admirer of Dan Siegel, I find his insights particularly enlightening. In his two books, he delves into the complexities of the brain and offers strategies for assisting children with self-regulation and fostering heightened self-awareness. As individuals become more self-aware, their understanding extends to their actions in various situations. This prompts contemplation on their locus of control—can they influence outcomes? Additionally, exploring their window of tolerance becomes essential; understanding how much work or engagement they can handle before reaching a point of being overwhelmed.

For instance, in an upcoming session with teenagers, I plan to center our discussion around the significance of gratitude as a fundamental attitude. I reflect on the common practice of expressing gratitude for birthday or Christmas presents, yet observe that such expressions are infrequent in daily life. As part of our dialogue, I often share anecdotes, like the scenario at the grocery store, where a simple exchange of pleasantries occurs. Do individuals merely respond with a cursory "You too" or "Have a nice day" without genuinely connecting with the person as a fellow human being? It's these seemingly mundane interactions that provide an opportunity for a meaningful exchange—encouraging authentic presence, with the ultimate goal of fostering increased self-awareness among the teenagers I work with.

Abrams, 2022

- Abrams, from the article What Neuroscience Tells Us About the Teenage Brain

- “Heightened sensitivity to rewards, for example, which is partly driven by increased activity in a part of the brain called the ventral striatum, has been implicated in behaviors such as substance use and unprotected sex among teens. But research now shows that in different settings, that same neural circuitry can also promote positive peer influence and behaviors, Telzer said, such as wearing a seat belt or joining a peaceful protest.”

This article by Abrams, titled "What Neuroscience Tells Us About the Teenage Brain," delves into the sensitivity to rewards inherent in the teenage brain. This sensitivity is intricately linked to increased activity in the ventral striatum, a part of the brain. Notably, this circuitry has been associated with behaviors such as substance abuse and unprotected sex. However, recent findings indicate that the same neural pathways can also contribute to fostering positive outcomes, including better relationships with peers and increased responsibility.

Consider scenarios where this circuitry can be harnessed for positive development, such as wearing a seatbelt, participating in a peaceful protest, or becoming more engaged in school-related activities. Creating environments that stimulate these circuits could potentially lead to more responsible and constructive behaviors.

Reflecting on a personal experience, when my children were growing up near the ocean, their class took a hands-on approach to environmental awareness. They measured out a thousand square feet at the beach, calculated the square footage in a mile along the eight miles of seacoast, and engaged in activities like picking up and sorting garbage. This immersive experience was a remarkable opportunity to showcase the consequences of littering and the abuse of the beach area, igniting passion for environmental stewardship.

In essence, providing teenagers with such hands-on experiences can open avenues for passionate and meaningful engagement, leveraging the reward-sensitive circuitry in their brains for positive outcomes.

- "As the field of developmental neuroscience matures, so too do the questions researchers ask. Studies are increasingly considering the influence not just of peers but also of parents. Researchers are also looking closely at how social media use may affect young brains, as concerns mount about teens’ online activity. As a result, research on the teenage brain is finally starting to catch up with studies of other age groups, complete with the level of detail it deserves.”

- “The shift from childhood to adulthood is not a linear one. Adolescence is a time of wonderfully dynamic change in the brain,” said BJ Casey, PhD, a professor of psychology who directs the Fundamentals of the Adolescent Brain Lab at Yale University. “Too often, we’ve superimposed an adult model onto a developing brain, but now we’re starting to see more nuanced findings.”

In the realm of developmental neuroscience, the questions researchers pose evolve alongside our understanding. Presently, a notable focus is directed toward examining how social media impacts adolescent brains, giving rise to concerns about online activity. These research endeavors are in their nascent stages, gradually delving into the intricate details of this complex landscape.

It's crucial to recognize that the transition from childhood to adulthood is far from a linear progression; it embodies dynamic change. Despite the apparent maturity of teenagers, there exists a nuanced difference between them and what we traditionally define as adults. While this may seem like an obvious realization, it is easy to overlook. For instance, when working with a seemingly fully developed and articulate 16-year-old, it's essential to pause and acknowledge that they still have approximately 10 years before the full maturation of their frontal lobe. This recognition prompts a deeper understanding of the ongoing developmental processes and underscores the need for a nuanced perspective when interacting with adolescents.

What Can We Do In Our Treatment?

- Adolescents crave independence and connection. Peers are so very important. The motivations of an adolescent are very different from a younger child. As educators and therapists, we need to learn what their passions are. Acknowledgment of who they are means you really see them.

- My favorite line is to say to them, “Do you find that all the grown-ups in your life expect you to step up and act like an adult, but they often treat you as a kid?”

- This, in turn, creates discussion about what are the walls that school/home presents and what bridges can be built toward adulthood.

The crux of the matter lies in how we apply this wealth of information to shape our interventions in schools. Understanding that peers play a pivotal role and that adolescent motivations differ significantly from younger children is crucial. Identifying their passions and fostering connections are key components of effective engagement.

When conversing with teenagers, a powerful approach is to pose a relatable question: "Do you feel that all the adults in your life expect you to act like an adult, yet treat you like a kid?" This question acts as a catalyst for connection, sparking conversations about their experiences with teachers, grandparents, and parents. It delves into the irony of the expectations placed upon them—balancing responsibilities and seeking freedoms. Establishing these connections helps them explore ways to demonstrate their maturity in their interactions.

Furthermore, addressing common sources of conflict is essential. For instance, when they express frustration by retreating to their room and slamming the door, we explore whether this builds a bridge or a wall in communication with their parents. The goal is to guide them in building bridges, showcasing their capabilities and authentic selves.

Reflecting on the impact of COVID-19, which may still linger, it's evident that the tight-knit family dynamics during the pandemic limited opportunities for teenagers to spread their wings. Now, as they gain a bit more independence and time away from family, there's a notable shift. Those who have this space are more inclined to get involved in life, embracing a journey of self-discovery and independence. Recognizing and facilitating these moments of self-birth becomes crucial in our interventions.

Moving From Childhood Dependency Towards Adult Responsibility

- As mentioned earlier, adolescents may react to faces differently than children and adults. They may not react to facial expressions or neutral interactions as expected, and they may, in fact, react with exaggerated emotions. Is it important to educate them and their teachers? Yes!

- Teens often want to know why…is there a forum for information?

- Their brain appraises what we offer, to see if they want to pay attention. Is this good or bad for me? The adolescent’s evaluative circuits change. How do we open their limbic systems?

- Siegel says that educators may find more kickback from middle schoolers if the system is run like an elementary school.

Transitioning from childhood dependency brings about a need for heightened awareness. Notably, teenagers may exhibit unexpected reactions to faces, potentially not responding as anticipated to facial expressions or neutral interactions. In these moments, I often share insights with them, explaining that their evolving brains are undergoing significant changes, impacting how they perceive and react to facial cues. I pose questions like, "How might you decipher the meaning behind a subtle eye roll? Could you ask for clarification to better understand?"

In this transformative phase, their brains are in a constant process of appraisal, evaluating stimuli to determine their significance—whether it is beneficial or detrimental. This evaluation extends to what educators, friends, and the school environment offer. Recognizing that shared interests open up the limbic system, I emphasize the importance of aligning educational approaches with subjects that genuinely capture their interest.

Dr. Siegel's observation regarding middle school education is intriguing. He highlights the potential pitfalls when attempting to recreate an elementary school environment at the middle school level. This approach can lead to heightened resistance, manifesting as increased irritability among students. The absence of a sense of autonomy, as they feel treated like younger children, becomes a notable factor. This insight underscores the importance of fostering a sense of independence and autonomy in educational settings catering to middle schoolers, contributing to a more positive and conducive learning environment.

Sleep

- Another point to be aware of is…Some of what we are witnessing could also be based on exaggerated due to lack of sleep. Circadian rhythms for adolescents are different.

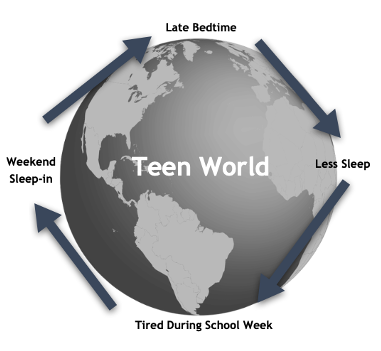

Another crucial aspect to consider, and as some of you may already know about my focus, is the significance of sleep. In adolescence, we often observe challenges with their circadian rhythm. Many teenagers establish late bedtimes, resulting in reduced sleep during the school week, subsequently leading to fatigue. The common pattern then becomes compensating for this sleep deficit by attempting to "catch up" on the weekends. This sleep pattern can significantly impact their overall well-being and academic performance. Understanding and addressing these circadian rhythm challenges becomes essential in supporting the holistic development of adolescents. Figure 1 shows an example.

Figure 1. An illustration of teen sleep.

Smart but Scattered for Teens by Guare and Dawson

- “Many teens will have wake-up issues…from a biological perspective, the wake-sleep clock in adolescents’ bodies changes so that they are naturally awake later, but still need a good night’s sleep.”

- This group tends to be more awake/alert afternoons/evenings versus an elementary student.

- Should the time of day of treatment change?

For those working with teens, I highly recommend the book by Guare and Dawson, which provides valuable insights into executive function - a crucial aspect connected to frontal lobe development. One notable topic they address is wake-up issues, rooted in the biological changes occurring in an adolescent's body. The wake-sleep clock undergoes a shift, making them naturally more alert and awake later in the day.

Understanding this biological shift prompts us to reconsider the timing of our interactions with adolescents. Recognizing that they tend to be more awake and alert in the afternoons and evenings compared to elementary students, adjusting the timing of sessions or activities can enhance their ability to engage and participate effectively. This simple consideration aligns with their natural biological rhythms, fostering a more conducive and productive environment for interaction and learning.

Frances Jensen’s book, The Teenage Brain…

- Nothing good comes from sleep deprivation.

- There is a direct relationship between learning and sleep for teens. One study he discussed was a single change by starting schools 70 minutes later had a dramatic effect for the positive with better grades statistically.

- Another study cited a school that started an hour later. They noticed attendance rose, standardized test scores improved, and auto accidents decreased.

- Simply changing exam times from 8 am to 10 am affects scores positively.

- Teens who have sleep disturbance, often consume more fried food, sugary foods, caffeine, and soft drinks.

Frances Jensen's exploration of sleep deprivation in her books underscores a direct correlation between learning and sleep in teenagers. Notably, studies have demonstrated the positive impact of delaying school start times. In one instance, a 70-minute delay resulted in statistically improved grades. Another school, with a one-hour later start, witnessed increased attendance, improved standardized testing outcomes, and a reduction in auto accidents.

These findings prompt a reevaluation of school schedules. While logistical challenges, such as bus schedules, are often cited as obstacles to later start times, the potential benefits, as seen in improved engagement, attendance, and academic performance, suggest a need for creative solutions. Considering the possibility of starting elementary school earlier and concluding earlier in the afternoon, while high school starts later and extends into the afternoon, could better align with the natural circadian rhythms of different age groups.

Moreover, the timing of exams has been shown to impact performance. Starting exams later in the morning, around 10 A.M., positively influenced scores. Beyond sleep patterns, the discussion also delves into dietary factors. The consumption of fried food, caffeine, and soft drinks can contribute to dysregulation, affecting self-regulation and alertness in teenagers. These considerations highlight the multifaceted approach needed to address factors influencing adolescent well-being and academic success.

Understanding Our Teen Clients

- We must be skilled in making inroads into understanding the teen we are working with….

- Who influenced you as a teen?

- How did they treat you?

- What characteristics did they possess that made you feel accepted, empowered, safe, and able? Let’s think about this!

Reflecting on our own experiences, it's valuable to recall those individuals who influenced us during our teenage years in a school setting. Whether it was a peer we admired, a teacher, or a guidance counselor, what set them apart were the qualities that made us feel accepted, empowered, safe, and capable. This introspection serves as a reminder that our approach as educators and therapists can profoundly impact how teenagers perceive us.

Recognizing the challenges some teens may have in dealing with authority figures, it becomes crucial for us to be mindful of how we present ourselves. Shifting our perspective to see them as individuals rather than participants in a routine treatment session fosters a more personalized and empathetic connection. Opening conversations with simple inquiries about their week and allowing them a few minutes to share what's on their mind provides an opportunity to clear the air and establish a sense of togetherness.

Drawing from a personal example, Mr. Meyer, a teacher who led a current events class during the Watergate era, stands out as a significant influence. His ability to bring real-world events into the classroom, creating a space for discussion and curiosity, left a lasting impact. This approach of engaging students with relevant and intriguing topics showcases the potential of fostering meaningful connections that go beyond the traditional educational framework.

Making Our Treatment Pertinent For Our Clients

- Here is a story about a teenage boy, an IEP, and a keyboarding goal! Perhaps a life skill?

In a particular school setting where I served as an occupational therapist, there was a teenager named Tim who had challenging behavior, particularly when it came to handwriting and motor coordination. Previous attempts at intervention focused more on containment than understanding the root cause of his frustration. Tim was initially assigned keyboarding sessions twice a week for 30 minutes, but his negative response to the previous therapist's approach was evident when I introduced myself.

I acknowledged Tim's frustration, and instead of reacting to his use of explicit language, I inquired about his past experiences. He expressed dissatisfaction with the previous therapist's methods, involving a computer program with spaceships that failed to engage him. Sensing his disinterest, I proposed a different approach, asking for just half an hour to explain my perspective.

I revealed the rationale behind keyboarding, emphasizing its potential to enhance his efficiency compared to handwriting. To illustrate, I had Tim copy a paragraph from a magazine, timing his writing speed and discussing the challenges he faced. Subsequently, we transitioned to typing, where he demonstrated better skills and significantly increased speed.

By presenting the information as a collaborative effort and setting a goal to complete the keyboarding program, Tim became actively engaged in the process. He demonstrated remarkable dedication, even seeking me out if I was slightly late. This shift not only improved his academic output but also positively impacted his overall attitude. The key takeaway from this experience is the concept of "naming it to tame it," emphasizing a collaborative, goal-oriented approach over a traditional therapist-student dynamic.

- How many of us include the pre-teen and teen in IEP development?

- Are we tending towards consultative services for the right reasons?

- Have you tried more hands-on approaches…?

- Are your detective skills for what is occurring throughout a school day keeping you informed?

Incorporating pre-teens and teenagers into the development of their Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) might initially feel uncomfortable, but it proves beneficial by actively engaging them in the process. When discussing future goals, I encourage the students to reflect on their progress, using a scale of one to five to assess their achievements. This collaborative evaluation helps in identifying areas that may need additional attention.

As we consider a shift towards consultative services, it becomes crucial to question our motivations. Understanding the neurodevelopmental aspects of these students suggests that a more hands-on approach, viewed from a different perspective, might yield better results. Taking the time to comprehend the students' experiences as they move between classrooms, identifying teachers they find motivating, and understanding the behaviors that demotivate them can contribute significantly to tailoring effective interventions.

Zhao: Why Identity and Emotion are Central to Motivating the Teen Brain

- A window of formative brain development …between the ages of 9-13 and likely through the teenage years”. She quotes Ronald Dahl from Berkley…”This is a flexible period for goal engagement, and the main part of what’s underneath what we think about setting goals in conscious ways – the bottom-up based pull to feel motivated towards things.”

The article highlights an intriguing concept: the window of formative brain development between ages 9 and 13 as a flexible period for goal engagement. The essence lies in consciously setting goals during this time and harnessing the bottom-up pull that motivates teens towards these objectives. By involving teenagers in the goal-setting process, using it as a consistent reminder throughout the year, and acknowledging and celebrating shifts and changes, we can effectively apply applicable treatment strategies.

Consultative Model

- The consultative model often can leave us feeling less empowered to make a difference. I want to share about this group!

- I did a group with 5 students in 6th grade that was focused on executive function practice and development.

The consultative model sometimes leaves us feeling less empowered to make a significant difference. I recall a sixth-grade group I facilitated at a public school a year ago, comprising five students with goals centered around socialization, impulse control, organizational skills, and cooperative group work. These objectives primarily targeted the development of their prefrontal cortex. Many of these students had been part of my caseload since their elementary years.

- The group planned and taught skills to their peers once a month. Activity-based intervention with a twist!

During our sessions in the gym, which provided a great space, I dedicated the initial six weeks of the school year to building rapport and understanding the students better. They collaborated as a group on various activities. After witnessing their smooth teamwork, an idea struck me. I said, "I think we should set up something for our class." Puzzled, they inquired, "What class?" I responded, "Your fifth and sixth-grade class" since they were combined. The proposal was to organize and run some centers for their peers. Examples are seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Center examples.

Creating and implementing these centers became an engaging and educational process for the students. Each had a specific interest, such as basketball, street hockey, yoga, or crafts. Over the course of eight months, I facilitated their planning and organization, teaching them the necessary skills to run their respective centers effectively. As they developed their roles and responsibilities, I noticed a transformation in their leadership abilities.

The students practiced and role-played, figuring out logistics like the number of participants, the duration of each session, and the required equipment. By the eighth month, they were independently managing their groups, demonstrating a remarkable level of autonomy. The positive feedback from their peers served as valuable reinforcement. For example, one student received praise for their patience in teaching origami, while another learned about the importance of assertive leadership.

This approach not only enhanced their organizational and leadership skills but also provided them with a tangible way to apply their strengths and interests. It felt like a therapeutic intervention, where the students learned crucial life skills while gaining recognition and respect from their peers.

Consider Students' Profiles

- As we assess and treat, what do we see? Are we looking at the whole person, in and out of school?

- What support systems exist outside for these kids?

- If you are noticing low effort: What may shift the attention? Working with peers versus alone?

- Are we offering moments of mindfulness throughout the day?

- Are there down times to get to know who they are? Who is listening to their dreams?

When assessing and treating adolescents, it's vital to consider the entirety of their lives, both within and beyond the school setting. Explore the presence of external support systems, delving into their home environments and available resources to gain a comprehensive understanding. Observe their effort and attention levels, identifying potential motivators that can shift their focus. Consider the dynamics of individual versus peer sessions, recognizing the impact of group interactions on adolescent development. Integrate mindfulness and brain breaks into the daily routine to support their overall well-being and attention span. Reflect on the school schedule and expectations, exploring alternative models that prioritize regular breaks, as seen in countries like Finland. Take the time to genuinely get to know the adolescents by engaging in casual conversations, joining them during lunch, and actively listening to their dreams and aspirations. This holistic approach ensures a more supportive and understanding environment, acknowledging the individual needs of adolescents in the therapeutic process.

Access

- Are there opportunities during a school day to promote abilities? Would co-therapy with speech or social work help with connection?

- Does the tech teacher need help with maintenance, inventory, helping teach younger kids?

- Are there daily things at school that this student might be interested in doing? Let me share about bus duty!

- Or…clubs such as drama, debate, game cafés, chorus, instrument lessons, sports, student council, decorations, pep rallies, etc.?

In exploring additional avenues, we can consider various opportunities throughout the school day. This entails evaluating if collaborative efforts with speech and language pathologists or physical therapists are beneficial for high school students. Furthermore, identifying areas where support may be required, such as assisting the tech teacher with maintenance inventory, is crucial. This aligns with the concept I previously discussed with Robert Brooks, emphasizing service duties as a means of teaching hands-on tasks. An illustrative example involves a student I worked with who embarked on an independent study, learning the ropes of working at a pizza joint during lunch hours. This hands-on experience equipped him with valuable skills, from customer interactions to order processing and giving change. Encouraging students to engage in practical tasks aligns with fostering independence and real-world competencies.

Moreover, considering daily tasks within the school environment is pivotal. For instance, proposing responsibilities like managing bus calls in middle school, where a student ensures the smooth boarding process, can provide a sense of purpose. Often overlooked but immensely impactful is the establishment of clubs to ignite passion among students. From drama and debate clubs to unique initiatives like a game cafe featuring classic board games, these avenues provide diverse outlets for exploration. My recent experience with a middle schooler exemplifies the positive impact of external engagements. When faced with a challenging day, a collaborative walk with the student and my dogs, followed by hands-on involvement in setting up a welcoming school board, proved to be an effective means of regulation and engagement. These experiences underscore the importance of tailoring interventions to each student's interests and strengths, thereby facilitating meaningful connections with the learning process.

The Yellow Wallpaper Example

- An example of working within the context of the classroom. The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkin Gilman

- “The most beautiful place! It is quite alone, standing well back from the road, quite three miles from the village. It makes me think of English places that you read about, for there are hedges and walls and gates that lock and lots of separate little houses for the gardeners and people.

- There is a delicious garden! I never saw such a garden - large and shady, full of box-bordered paths, and lined with long grape-covered arbors with seats under them.”

- The teacher needed help with engagement and focus…we worked on visualization.

Exploring unconventional approaches to therapy, I once utilized a passage from the book "The Yellow Wallpaper" to engage students in a unique comprehension exercise. The book depicts a woman confined to a room due to a traumatic experience, and her vivid descriptions of her surroundings serve as a catalyst for a creative activity. I presented quotes from the text, such as "The most beautiful place! It's quite alone, standing well back from the road, three miles from the village." Instead of traditional methods, I encouraged the students to sketch their recollections of the described scenes. The exercise not only enhanced their comprehension but also sparked curiosity, leading to questions like "What's an arbor?" This prompted a quick Google search and expanded their understanding. As we delved into comprehension, I guided them to close their eyes and imagine the details of the town, emphasizing observation of paths, hedgerows, and other elements.

This method fostered active engagement in the therapeutic process, allowing students to visualize and connect with the material rather than passively reading or listening to it. Transitioning to the broader context of treatment, it's essential to consider not only developing abilities but also preventing the regression of acquired skills. Driven by the concern articulated by Siegel about skill deterioration when neglected, proactive therapeutic strategies become imperative in maintaining and advancing the cognitive abilities of individuals.

Drop Out Statistics

- 11 Facts About High School Dropout Rates | DoSomething.org

- Every year, over 1.2 million students drop out of high school in the United States alone. That’s a student every 26 seconds – or 7,000 a day.

- The US, which had some of the highest graduation rates of any developed country, now ranks 22nd out of 27 developed countries.

- A high school dropout will earn $200,000 less than a high school graduate over his lifetime, and almost a million dollars less than a college graduate.

- In the US, high school dropouts commit about 75% of crimes.

As I contemplated this lecture, I found myself immersed in the stark realities faced by today's high school students. Alarming statistics reveal that annually, 1.2 million students drop out of high school in the United States alone, translating to a student abandoning education every 26 seconds or 7,000 a day. The country, once boasting high graduation rates, now stands 22nd out of 27 developed nations. The repercussions of dropping out are profound, with a high school dropout expected to earn $200,000 less than a graduate over a lifetime and nearly a million dollars less than a college graduate. More unsettling is the correlation between high school dropouts and criminal activities, with 75% of crimes committed by this demographic. The gravity of these statistics compels us to consider the long-term consequences for these students and prompts a critical examination of how we are addressing their needs in the classroom.

Observing classrooms reveals a departure from the original intent of block scheduling, where the initial promise was a blend of deep content learning and hands-on application. In some instances, adaptations are being made to accommodate the distinct attention and focus patterns of 21st-century students. Examples include implementing centers in honors classes, where students engage with topics related to the teacher's rubric, fostering peer-to-peer learning and presentations on specific aspects of a broader concept. This shift underscores the evolving strategies educators are employing to better align with the learning styles and needs of contemporary students.

The Good News

- Eric Jenson and Carol Snider from their book, “Turnaround Tools for the Teenage Brain” say:

- “Underperformance does not determine destiny.”

- “Brains, IQs, and attitudes can change.” This may be something they need to know.

- “If you have the will and the skill, you can make significant and lasting differences in students’ lives.”

- Destiny is determined- 30-40% genes and 60-70% environmental factors/gene environmental interactions

Indeed, amid the challenges faced by high school students, there is a glimmer of hope. Eric Jensen and Carol Snider, authors of "Turnaround Tools for Teens," offer a reassuring perspective by emphasizing that underperformance doesn't dictate destiny. Their assertion that brains, IQs, and attitudes are malleable and can undergo positive transformations is a powerful message that students need to hear. Importantly, they stress that with the right will and skill, educators can effect meaningful and enduring changes in students' lives. The intriguing aspect lies in the statistics they present, revealing that destiny is influenced 30% to 40% by genetics and a substantial 60% to 70% by environmental factors and interactions. This insight underscores the significant role educators play in shaping and influencing the developmental trajectory of high school students, providing a motivating foundation for transformative interventions.

Summary

Thanks for attending today. I hope you enjoyed it.

Questions and Answers

Can you share more about having your dogs with you in your work?

Absolutely. After retiring from full-time OT work in schools about a year and a half ago, I started doing more part-time work. One of my dogs, a black Lab, was diagnosed with mast cell cancer, and the vet gave him one to three months to live at eight years old. However, following a pill-based chemo regimen (Monday, Wednesday, Friday), he has now lived for 20 months. He attended a Canine Citizen course sponsored by AKC, and now his sister, a chocolate Lab named Penny, joins us in schools. The kids love them, and it's covered under my homeowner's insurance.

What are your thoughts on youth missing out on peer connections due to illness, COVID, or mental health, especially those not in high school or college?

When addressing the lack of social connections, it's crucial to consider it across the lifespan. Whether it's an infant not being stimulated or an elderly person living alone, social connection is vital. To intervene, focus on the individual's interests and passion. Discover what engages them, be it watching YouTube videos or exploring unique hobbies, and then find ways to bring it into more outgoing, social settings.

How do you feel about a four-day school week concerning teen sleep and energy cycles?

A four-day school week could be beneficial, especially if it accommodates later start times. Ensuring that activities are planned in the afternoon, incorporating social clubs, can provide the needed social interactions. It's crucial to consider teachers' preferences and avoid excessively long days for both students and educators.

Any ideas for motivating teens for home-based tasks?

Novelty and offering incentives can be effective in motivating teens for home-based tasks. Given that their frontal lobes are not fully developed, setting realistic expectations and providing rewards for completing tasks can be helpful. It's essential to understand their perspective and balance expectations for age-appropriate responsibilities.

What strategies can be employed when a school schedule starts very early, like at 7 am?

If a school's schedule starts early, making changes may be challenging. It could be beneficial for parents to collectively address this issue during PTO meetings. Collaborating with other families affected might increase the likelihood of the school considering adjustments to the schedule.

How does online learning impact students, considering the need for social interaction?

While online learning might be suitable for some students, especially those on the spectrum who prefer a more controlled environment, it lacks the essential social-emotional development gained through in-person interactions. The increasing incidents involving teens between 3 and 5 pm highlight the importance of addressing the need for social gatherings.

Any information on the lack of pruning in neurodivergent populations?

While there's no specific information on the lack of pruning in neurodivergent populations, differences in brain development, especially in ADHD, are noted. ADHD-diagnosed individuals may have a frontal lobe development delay of around 30%, emphasizing the need for tailored interventions.

How can we work with teachers to incorporate student-led centers in classrooms?

Initiate a conversation with teachers, emphasizing the benefits of smaller group activities for better attention. Understand the teacher's perspective and workload, highlighting the positive impact on students' engagement and learning. Approach the discussion with a focus on collaboration and improved learning outcomes.

As a COTA, how can age-appropriate goals be set while respecting OTR goals?

Engage in a discussion with the OTR about the end goals, such as knowing all 26 letters and functional keys for keyboarding. Emphasize adaptations and accommodations that allow for successful skill development. Collaboration and defining the ultimate purpose of the goals can lead to more age-appropriate and engaging interventions.

Can you recommend books addressing neurobio development in older teens, especially in high school?

"Smart But Scattered" is a good resource for understanding executive function. Additionally, books by Daniel Siegel, such as "The Yes Brain" and those focusing on teenage brain development, can offer valuable insights. Russell Barkley's work on prefrontal development in ADHD may also be relevant.

How can we help an 18-year-old transition to a healthier circadian rhythm?

Educate the individual about circadian rhythms and work together to establish a nighttime routine. Focus on gradually lowering lights, limiting screen time, and incorporating relaxing activities. While it might be challenging due to socialization patterns, empowering the individual with knowledge can aid in making informed decisions.

If a teen has many interests, should all of them be explored or prioritized?

Engage in a conversation with the teen to explore their interests. Consider categorizing interests into independent, parallel, and cooperative activities. Evaluate whether they prefer individual pursuits, engaging in the same activities side by side, or working collaboratively. This approach ensures a balance and promotes diverse social and play skills.

Have you encountered students interested in learning musical instruments, and how did you encourage them?

Yes, I've worked with students interested in learning musical instruments, like Leonard. Collaborating with parents and leveraging the expertise of music teachers can provide additional support. Offering extra time in school and facilitating connections with external instructors can help nurture these interests.

How can statistics on grades and measurable outcomes be presented to resonate with school administration?

Utilize statistics and data on grades to emphasize the correlation between social interactions and academic performance. Emphasize the broader impact on measurable outcomes and present this data during discussions with school administration to advocate for a more comprehensive approach to education.

References

Abrams, Z. (2022) What neuroscience tells us about the teenage brain. American Psychological Association, 53(5).

APA (n. d.). Speaking of psychology: Understanding the teenage brain with Eva Telzer. Retrieved from: https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/teenage-brain

Blakemore, S-J. (2018) Inventing ourselves: The secret life of the teenage brain. Public Affairs.

Casey, B. J., Heller, A. S., Gee, D. G., & Cohen, A. O. (2019). Development of the emotional brain. Neuroscience Letters, 693, 29-34, ISSN 0304-3940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2017.11.055.

DoSomething.Org. (n.d.). 11 facts about high school dropout rates. Retrieved from: https://www.dosomething.org/us/facts/11-facts-about-high-school-dropout-rates

Gilman, C. P. (1892- Release date 1999). The yellow wallpaper. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved from: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1952

Guare, R., Dawson, P., & Guare, C. (2012). Smart but scattered teens: The ”executive skills" program for helping teens reach their potential. The Guilford Press.

Henry, D. A., Wheeler, T., & Sava, D. I. (2004). Tools for teens handbook: Strategies to promote sensory processing. WPS.

Hohnen, B., Gilmour, J., & Murphy, T. (2019) The incredible teenage brain. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Jensen, F. E., & Nutt, A. E. (2015). The teenage brain: A neuroscientist’s survival guide to raising adolescents and young adults. Harper.

Jensen, F., E., & Snider, C. (2013). Turnaround tools for the teenage brain: Helping underperforming students become lifelong learners. Jossey-Bass.

Magis-Weinberg, L., & Berger, E. L. (2020). Mind games: Technology and the developing teenage brain. Frontiers for Young Minds.

Weir, K. (2019). A deep dive into adolescent development. American Psychological Association, 50(6).

Siegel, D. (2015) Brainstorm. TarcherPerigee: New York, NY.

Siegel, D. (2010) Mindsight. Bantam: New York, NY.

Zhao, E. (2015, Dec.). Why identity and emotion are central to motivating the teen brain. Retrieved from https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/43037/why-identity-and-emotion-are-central-to-motivating-the-teen-brain

Citation

Bowen-Irish, T. (2023). The pruning effect on the teenage brain (it’s not just hormones). OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5654. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com