Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Psychosocial Considerations in the Pediatric Acute Care Hospital Setting, presented by Laura Stimler, OTD, OTR/L, BCP, C/NDT.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify risk factors for psychosocial issues and conditions among children admitted to the acute care setting.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize evidence-based psychosocial assessments for occupational therapy practitioners in pediatric acute care.

- After this course, participants will be able to list strategies for implementing evidence-based approaches within the scope of occupational therapy practice to decrease the burden of psychosocial issues in children admitted to the acute care setting.

Introduction

It is always a pleasure presenting with OccupationalTherapy.com. My name is Laura Stimler, and I have had the wonderful privilege of working as a clinician in various pediatric settings, including long-term pediatric care, rehabilitation, early intervention, outpatient, and acute care. In addition to teaching, I currently work as a PRN OT at a pediatric long-term care facility. I have been working as an OT for nearly 20 years. I continue to be amazed at how gracefully so many skilled OTs are at managing and navigating the sensitive psychosocial concerns and challenges for children and families in pediatric hospital settings. Thank you for joining me today as I navigate through some of these challenges with you and discuss the unique ways we can ease the burden for families and children with our OT perspective.

Pediatric Acute Care Overview

Pediatric Hospitalization Statistics

- 5.5 million hospitalizations in children 0-17 years in 2016

(Committee on Hospital Care, 2020)

According to the Committee on Hospital Care, approximately 5.5 million children between 0 to 17 years were hospitalized in 2016.

Pediatric Conditions In Acute Care

- Reasons for admission:

- Respiratory illness (pneumonia, acute bronchiolitis, asthma)

- Appendicitis

- Seizures

- Infections

- Dehydration

(Committee on Hospital Care, 2020)

The reasons for many of these admissions included respiratory illnesses like pneumonia, acute bronchiolitis, asthma, and many others. The second most common reason was appendicitis. Next are seizures, infections, and then dehydration. This information is according to the Committee on Hospital Care.

General Considerations

- Admissions due to trauma or acute illness are different from planned admissions.

- Transfers between hospital units

- Pain

- Separation from caregivers

- Invasive tests

- Unfamiliar staff and routines

- Sensory environment

(Pike & Enright, 2015)

Some general information about risk factors that are unique to children is important to consider. First, for children and families admitted to the acute care setting that is the result of a trauma or acute illness will be a much different experience than a planned admission. They can be significantly more challenging and affect the entire family. In addition, transfers between hospital units can cause significant stress as well, especially for younger children. An example of this is transitioning from a regular or a general hospital floor to the pediatric intensive care unit. A PICU is going to have strict guidelines for visitation and medical care. These rigid guidelines and unfamiliar environments can cause heightened stress and emotions overall.

Pain also is more difficult to assess in children for many reasons. When assessing pain in a verbal adult that is cognitively aware and able to communicate their needs gives a more objective measure using numbers. For children who are non-verbal for whatever reason, pain becomes a bit more subjective to assess. It is essential to use pediatric-friendly pain analog scales with either pictures or colors more age-appropriate for children. In children who are too young to articulate their needs and wants, pain can be challenging to assess.

Caregiver separation is often a significant source of stress as well. Separation is required for many tests and procedures that occur in a pediatric acute hospital setting. And, these tests are frequently invasive and painful, causing increased stress.

Children are also expected to adapt to an entirely new environment. The environment may involve unfamiliar staff and people and a completely different sensory environment than they are used to. They are exposed to different smells, sounds, temperatures, equipment, and supplies. Their overall experience is very different from more familiar settings.

Risk Factors

- Post-Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS)

- ICU Acquired Weakness

- Cognitive Deficits

- Delirium

- Chronic conditions/cancer

- Parent & child post-traumatic stress

(Hall et al., 2020; Chari et al., 2020; Franck et al., 2015)

In addition to some of these typical challenges, more significant risk factors are unique to children admitted to more critical care. Post-intensive care syndrome, or PICS, is a syndrome that has become more conceptualized with a greater focus on children over recent years. Children affected by PICS often experience issues soon after discharge from the hospital, ranging from cognition, emotional functioning, sleep, and functional changes. There are specific domains associated with PICS that are expected to make this diagnosis. These are changes in physical functioning, psychological functioning, functional status, and social changes. These domains may impact either the child, their caregiver, or the family. Children admitted to the PICU and those on bed rest are at higher risk for this type of condition and ICU acquired weakness. What is tricky in the pediatric population is that many of these conditions are determined based on behavioral presentation and functional status. For example, younger children with severe neuromuscular issues may present with limited movement due to their condition. Therefore, other indicators, including respiratory rate or changes in feeding, may be more indicative of decline. There are a variety of conditions that commonly use functional status, making them tricky to diagnose in children.

Changes in cognition are common in children admitted to the acute care setting, especially the PICU, as well as delirium. These are more common in children diagnosed with more chronic conditions. Specific cognitive changes that may occur include decreased attention, limited processing speed, and decreased memory. Other neurocognitive impairments are also common in children with these chronic conditions and those admitted to the PICU. There is not necessarily one single approach that will address all children, and children's previous experiences heavily influence the way a child can cope with a given situation in the hospital.

Hospitalization and Developmental Considerations

We also have to look at the developmental age, whether it is typical or atypical, and how it influences the child's experience, behaviors, and actions. We will shift our focus now to discuss and highlight age-specific considerations related to coping and children. Using age-appropriate strategies to communicate and provide care to the child makes it possible to ease the burden and decrease the stress on some of these children and families during their hospital stay. The information on the following few slides is heavily guided by the psychosocial developmental principles that Erik Erikson first introduced from a developmental psychology perspective.

Infancy

- Typical Development

- Sensorimotor play

- Milestones

- Hospital Considerations

- Maximize day/night environment

- Establish routines

- Age-appropriate and safe toys

- Maximize sensory experiences

(Pike & Enright, 2015)

Infants are trying to figure out if the world is an okay place. They do this through play and sensory-motor play. They are learning about their bodies and how to move around. A significant focus of our work and others often relies heavily on observing developmental milestones. These milestones may have to do with cognition, motor skills, sensory processing, and sensory perception. There are milestones and some general considerations that we look for when a child is admitted to the hospital. For example, we may need to create an environment more conducive to their growth and development. Creating a familiar space is one of the best ways to do that and also to incorporate as much routine as possible. This might involve educating the family on how to self-advocate for things like a sleep schedule for the child. They can set expectations by posting a sign on the door for sleep hours for the child. They can also change the physical environment in the room to simulate day and night lighting. We can encourage families to carry over a consistent sleep hygiene and preparation routine. They can also bring in familiar items like sheets, blankets, or whatever it may be to create a comfortable and predictable environment as much as possible. Lastly, using age-appropriate toys and maximizing their exposure to different sensory experiences will also be essential to help them maintain that trajectory of typical development moving forward.

Toddlers

- Typical Development

- Autonomy vs. shame: “I will do it myself.”

- Hospital Considerations

- Limit unnecessary separations

- Maintain routines

- Establish a “safe zone.”

- Maximize play opportunities and movement

(Pike & Enright, 2015)

Toddlers want to do things themselves. They want to be independent and are exploring their autonomy. Many of them test how far they can push limits. For toddlers in the hospital, it is essential to limit unnecessary separations from caregivers and family. This is tricky because separation is required for many invasive and intimidating procedures/surgeries in this setting. Thus, sticking to routines is essential. As with infants, it is crucial to create a safe space to offer the child some control.

Many places I have worked have established a safe zone where medical care or invasive procedures do not occur. This could be a special chair in the child's room or a special area on the floor. I have seen some child life specialty programs establish safe zones as well. The children know that if they are playing in that area, they will not be interrupted for a medical procedure, or a medical procedure will not occur there.

Fostering play opportunities and movement is critical for toddlers, especially chronically ill and critically ill. These children tend to be at higher risk for psychosocial concerns due to their prolonged hospitalization. Distraction through play and movement can be a great coping mechanism for children in the toddler age range.

Preschool

- Typical Development

- Magical thinking

- Egocentric/associated logic

- Hospital Considerations

- Maintain routines

- Allow participation through choices

- Maximize child’s opportunity for control

(Pike & Enright, 2015)

Preschool-age children often process using a combination of what is referred to as egocentric and associative thought logic. This can lead to magical thinking or interweaving of reality with their imagination. An example is a child who believes that a diagnosis is a punishment for thought or negative behavior that they had or demonstrated. So, procedures for preschool-aged children can feel like punishments because they cannot wrap their heads around the "why" behind what is happening. Another example is preschoolers trying to comprehend the disease process in some situations, specifically things like leukemia or other hematologic malignancies that do not have a localized area to address or treat. These can be difficult for children to grasp.

Children ages three to six years old tend to spend most of their time with their family and caregiver. Separation can be tough, especially in the confusing and complex hospital setting. Any chance you can offer control to these children is excellent and very important. Control can range from something straightforward like letting the child choose what color tape to use for their medical care or letting the child decide what color socks to wear that day if it is an option. Provide opportunities for control can help preschool children cope.

School Age

- Typical Development

- "Mastery of skills" and logical thinking

- Hospital Considerations

- Foster socialization

- Age-appropriate explanations

- Involve in care

- Give choices when possible

(Pike & Enright, 2015)

School-age children look to play a more active role in their care, and friends and social influences are starting to play a more significant role. Disruption of school attendance and interaction with their peers can lead to decrease coping in children this age. And prolonged hospitalization and chronic illness certainly put them at risk for those issues.

Children this age take a lot of pride in knowing things like their procedures and medication names. Involving them in their care is a great strategy to give them some sense of control and engagement while in the hospital.

Adolescence

- Typical Development

- Increased independence

- New relationships

- Sense of identity

- Education/employment goals

- Hospital Considerations

- Foster socialization

- Include in decision-making

- Respect privacy

Adolescence is a sensitive time, and teenagers also want to play a more active role in their care. They can think a bit more abstractly and process information about specific diagnoses or conditions in the same capacity that an adult would. However, they are focused heavily on embracing their newly acquired independence and may feel that it is being taken away from them during prolonged hospitalization.

Peer groups can heavily drive motivations and decisions for individuals in this age range. Sexual development can also be a significant influence as well. Adolescents with chronic conditions or those admitted in critical care that requires prolonged hospitalization are now dependent on their families again for things they consider to be basic. Other things like altered body image might be an issue for those who experienced significant physical changes due to the disease process or surgery and affect their self-esteem.

In some cases, their plans might be significantly disrupted. An example is teenagers diagnosed with different types of bone cancer. Over time, bones might not gain strength in the same way that they would otherwise. If adolescents have their minds on a career that requires a significant amount of heavy or physical work, they may need to rethink their career path. That cannot be easy to process for the adolescent age population, especially if their career plans or education plans are disrupted.

These types of conditions or complications can cause significant psychosocial concerns. We may see symptoms ranging from depression to distress to anxiety emerge more frequently in this age range as well.

Psychosocial Issues

- Collaborate with child life specialists

- Assess pain using age-appropriate pediatric pain scales

- Special training to support individuals with intellectual disabilities or ASD

- Preparing to manage end-of-life situations and palliative care

(American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] Committee on Hospital Care, 2020)

I found an interesting publication by the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care. The article highlighted some general considerations for acute care facilities that do not specialize in working with children, in improving their management of pediatric patients. I thought some of these basic concepts were worth sharing because many of them carry over into what we do as occupational therapists.

First, child life specialists' services are considered a standard of care to address psychosocial concerns in different pediatric acute care hospitals. These excellent practitioners offer so many contributions to the populations we serve, ranging from creating play experiences that involve specific play scenarios, medical play to prepare children for particular events in the hospital, supporting siblings, and explaining things from a developmentally appropriate perspective. I have worked with many child life specialists, and I find it helpful to collaborate with them to fabricate custom splints in the acute care setting. They are skilled at helping the child understand why something needs to be done and distracting them while doing it. If you feel like you do not have enough hands to do both, they can support that role. I worked with a five-year-old boy years ago that had a rare type of bone cancer. His family and the medical team elected to perform a rotationplasty procedure. This is a procedure used for clients who have a primary bone tumor in their lower extremity. The surgeon removes the tumor, and if there are clean margins, they might salvage the ankle and foot. They then turn the foot and the ankle into the knee.

I do not have a picture of it here, but you can visualize it. There is a very dramatic change physically with this type of procedure. Functionally, it can be fantastic and afford the child many opportunities they would not have with other types of limb salvage procedures associated with that diagnosis. From a functional perspective, it can be a great thing. Psychosocially, it can be a lot to process and work through after the procedure because there is such a dramatic change. He was adamant that he would not get out of bed, perform bed mobility, or look at the leg after the surgery. He had to get out of bed to maintain skin integrity and for all the reasons we know are so important. Due to his very fragile post-surgical state, even though he was tiny, we could not just scoop him up and help him sit in the chair. He had to be on board for us to facilitate that safely. I collaborated with the child life specialist involved in his care, and she came up with the most fantastic idea. She knew he loved robots, so she decided to turn his walker into a robot. We used construction paper and cardboard to bring this "walker robot" to life. The next day, he was agreeable to using his new robot to facilitate an out-of-bed activity. We worked as a team to meet his needs. Child life specialists are great. If you have not reached out to those in your facility, please do.

As mentioned before, pain can be challenging to assess in children formally. Traditional pain scales where individuals have to rate their pain from 0 to 10 are not appropriate or effective in very young children or children who may have issues communicating their wants and needs. It is essential always to be sure to use a pediatric-friendly or an appropriate visual analog pain scale. These scales use facial expressions or colors to effectively document and monitor pain. In very young children and infants, we look at some more subjective measures to document pain like facial grimacing, crying, and the overall demeanor of the child. In addition to that, taking clinical vital signs can give us information about pain. For example, how much does blood pressure change during a procedure, changes in position, or therapy? Heart rate can also give us some information about their pain as well.

It is crucial to have specialized training when working with children or individuals diagnosed with intellectual disabilities or autism spectrum disorder. Many places I have worked have looked to our department to help guide that process in supporting individuals with these unique needs during their hospitalizations. This is especially true of children who have significant sensory needs. Occupational therapists can provide great strategies to help them cope and be more comfortable within the hospital room and setting.

End-of-life situations and palliative care can be incredibly complex and challenging to navigate. These situations certainly require specialized care within the hospital-based setting.

AAP Recommendations for Pediatric Hospital Inpatient Care

- If a child is admitted to the acute care setting for longer than a week, a hospital liaison is recommended to partner with the school to prevent interruption in the child’s educational activities.

- Nurse

- Social worker

- Discharge planner

- Child life specialist

(AAP Committee on Hospital Care, 2020)

Another recommendation that the American Academy of Pediatrics suggested is that a hospital liaison should be utilized for children admitted to the hospital for a week or longer. This program aims to use hospital personnel like a nurse, social worker, case manager, discharge planner, or child life specialist to serve as a liaison between the hospital setting and school-based setting. This collaboration is helpful for a few reasons. First, this approach makes the carry-over of the child's needs a bit more practical. When all of this information falls on families, they may not completely understand all the ins and out of everything. This liaison clearly understands all the medical terminology and what it means for the child in the different environments. It can reduce the stress that falls on families when they feel like they are expected to tie up every possible loose end of a child's care. In addition to making services and carry over more efficient, it can decrease the burden on families.

Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice

- Standards of Practice for Pediatric Palliative Care: Professional Development and Resources Series

- Developmental needs

- Physiological resiliency & uncertainty

- Need to travel for specialized care

- Lack legal voice

- Engaged in multiple communities

- Devastating grief that extends to multiple communities

(National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2019)

As I mentioned before, pediatric palliative care and end-of-life care are exceptionally complex in the hospital-based setting. The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization published standards of practice, specifically for pediatric palliative care and hospice. I included the link to this document in my resources. If you would like to learn more information, I recommend looking at this resource as I found it very helpful. Their standards include specific considerations for how and why hospice care for children differs from adults. I cannot think of a tremendous privilege or honor than working with a child during their final days. We, as OTs, have a place in that. Many of the families we work with either do not prioritize OT or rehab services at that time, and that is perfectly fine. On the other hand, other families thrive. Some families use their child's engagement in therapy as a coping strategy for themselves and their children.

Typical struggles and issues associated with age-appropriate developmental needs during difficult and stressful times, like potty training or play skills, may be let go by the family. However, when focusing on play skills, the family may find comfort in knowing their child is still learning about play and advancing their play skills. It can be beneficial but tricky to navigate when you are trying to find that balance. Another child that I worked with in an acute care oncology setting is a great example. This particular child's family traveled internationally, and they wanted their child to receive care at a National Cancer Institute, a Children Oncology Group approved institution. During this child's final days, her family, including her siblings, her parents, and many of her caregivers, were able to come to the hospital where she was receiving care to be by her side. Unfortunately, one of her grandmothers could not travel to fly internationally as she was not well. This particular family thrived with rehabilitation services and valued what rehab had to offer throughout this child's continuum of care and her cancer diagnosis. During her final week, her family requested an OT session because they knew how much the child valued and enjoyed arts and crafts. We worked together on a project for the grandmother, who could not travel to see this child during her final days. The child talked about how she missed her grandma so much. We were able to support this child as she made a bracelet for her grandmother. It was a great and powerful session. It was also evidently clear how much it helped the family in their coping at that time. It helped them focus on something meaningful for their child.

Other considerations for pediatric palliative care are differences in physiological resilience and uncertainty. Many of the children we serve receive intensive and sometimes even neurotoxic treatment, specifically in the oncology population. Many of these treatments may have future side effects that could impede or cause barriers to function. When providing palliative care or trying to make a child comfortable after life-saving procedures, those unknowns about the impact on the future can be a source of stress. This is unique to the pediatric population because their future is a bit unknown.

Another issue is that many families give up their lives and travel to receive specialized care for their children. This can cause a significant source of stress on the family unit.

Additionally, children lack the legal voice that adults have. While they may not have the legal right to make decisions in their medical care, many of them are indeed very insightful and have at least a basic understanding of their surroundings and discussions that occur. Making decisions about end-of-life care and determining how much or when not to involve the child in those decisions can be very difficult to navigate.

Many children are also associated with a wide variety of environments like home, school, extended families, extracurricular activities, and neighborhood communities. This can result in devastating grief across multiple contexts when a child becomes critically ill or receives end-of-life care.

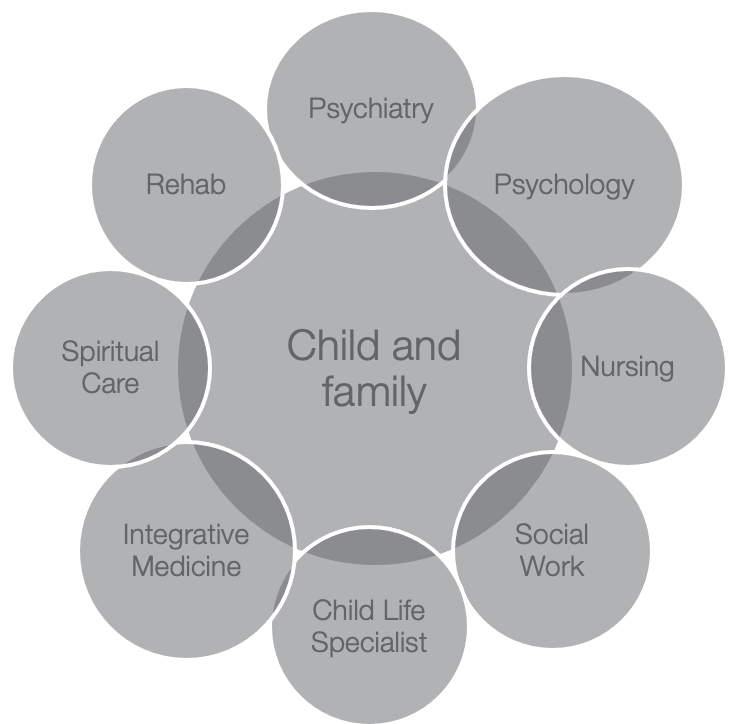

Multidisciplinary Approach

Tackling the many psychosocial issues children and families face in acute care settings requires a multidisciplinary approach (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Graphic showing all of the discipline involved with the child and family in an acute setting.

Psychiatry usually operates on a consultative basis to evaluate and treat conditions including, but certainly not limited to, depression, delirium, and distress. Psychiatrists typically utilize a pharmacologic approach for treating these conditions. Psychologists are available for evaluation and treatment. They tend to use specific techniques or frameworks like psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other approaches to address psychosocial issues for children and their families. The nursing staff is well-positioned to consistently assess and monitor and treat psychosocial concerns and do this in various ways. They often administer medication to decrease pain, decrease nausea, and improve comfort. These measures can ease the burden of stress associated with hospitalization. Also, nursing is consistently present to monitor any anticipatory anxiety related to procedures. They can also work closely with families to provide any answers to questions regarding procedures.

I mentioned child life previously. They are excellent for so many reasons. Again, they are skilled at providing age-appropriate explanations for procedures and events that occur in the hospital. They can also work closely with siblings as needed.

Social workers can help families navigate the complex healthcare system as this can be a significant source of stress. They also provide counseling and coping strategies and coordinate support groups for families and children in the hospital setting.

Integrative medicine compliments what we consider to be mainstream medical care. Integrative medicine departments may look different, depending on the type of facility. Some examples include other types of energy therapies, mind-body interventions, music, and dance. Also, spiritual care can be critically important, especially during crisis points of care, for families and children.

Occupational Therapy Considerations

What is our essential role in tackling these psychosocial issues for children in the hospital?

OT Assessment Tools

- PedsQL

- Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory

- COPM

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure

- SCOPE

- Short Child Occupational Performance Evaluation

- COSA

- Children’s Occupational Self Assessment

- PVQ

- Pediatric Volitional Questionnaire

Let's start with the evaluation process. There are many subjective questionnaires and screening tools, inventories, and interviews available to capture information about the psychosocial functioning of pediatric clients. The PedsQL, or the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory, explores the overall health-related quality of life for children of all ages. There are different subsections to the PedsQ, including a psychosocial and physical health summary. Each sub-test is tailored to the parent or child, and they cover a wide variety of conditions. For example, there are cancer, brain tumor, and stem cell transplant modules. It is age-appropriate and includes both a parent and child report so that you can compare the information.

Another assessment is the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM). This tool can be used on children of all ages. A parent report is recommended to supplement for children ages eight years and younger. I think the COPM is fantastic because it allows an individual to report levels of both satisfaction and perceived performance. It is an excellent tool across many populations.

The Short-Child Occupational Performance Evaluation (SCOPE) is based on MOHO or the Model of Human Occupation. The SCOPE addresses volition, habituation, communication, and the process and motor skills of the child.

The Children's Occupational Self Assessment (COSA) and the Pediatric Volitional Questionnaire (PVQ) are great tools to consider.

In our work as occupational therapists, we must always think about child-centered care. First, it is essential to promote independence. Sometimes we need to spell that out to families and let them know that it is okay to set expectations for their child to engage in their ADL routine or movement and play. Many families require a bit of feedback or education on the importance of participating in these activities and how they can be used as mechanisms for coping. It is also essential for families to understand strategies to prevent learned helplessness for their children and to set expectations as appropriate.

Other more general concepts related to intervention include that, whenever possible, trying to create choices for the child. This affords them a sense of control in an environment where they feel completely out of control. In the inpatient acute care setting specifically, creating a more conducive environment to play can be very helpful. You might even physically rearrange the room to create space to put a mat on the floor. You might invite caregivers to bring familiar toys or items from their home to set the room up in a way that allows a child to feel more comfortable and encourages their active participation.

OT Interventions

- Conceptual frameworks to promote coping are guided by adult models (Haertl, 2019)

- Relaxation

- Social skills

- Interpersonal effectiveness training

- Cognitive-behavioral techniques

- Behavioral reinforcement programs

- Promotion of self-control

- Engage in age-appropriate occupations (AOTA, 2020)

Most strategies that are described today are conceptual frameworks for facilitating coping. Children are heavily guided and influenced by existing adult models. Strategies that are supported by strong levels of evidence include things like relaxation. Relaxation strategies involve deep breathing, energy conservation, visualization, and meditation. We also want to use social skills training, interpersonal effectiveness training, cognitive-behavioral approaches, behavioral reinforcement approaches, and maximizing self-control. When we take a moment to refer back to the list of occupations presented and described in our Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF), we are reminded of the many appropriate activities for children. These include activities of daily living, play, sleep and rest, leisure, social interaction, and the list goes on. We can also use a virtual context, especially for our older school-aged children and adolescents. There is evidence emerging on many uses for digital stories, especially during times of isolation. This can be an effective way to help individuals and children with chronic illnesses dealing with issues over a prolonged period. It can be an excellent way for them to share their story as they feel comfortable. Encouraging these activities can also help decrease the burden of many other psychosocial conditions we see in acute care, specifically.

Play

- “Play is necessary in the hospital setting not only to process and understand information, but also to comfort, to engage, to cope, and to express feelings.” (Pike & Enright, 2015, p. 54)

- Play belongs to the child

- Play is meant to be enjoyable

- Any child can play

Zengin et al. (2020)

Play is one of the few opportunities children have to take control. Fortunately, there is strong evidence across multiple disciplines supporting the use of play as a way for children to cope while in the hospital setting. Based on nursing evidence, Pike and Enright (2000) describe three essential principles that should guide hospital-based play. They state that play belongs to the child and is enjoyable, and any child can play. Most of us would agree that these guidelines parallel closely to the current play frameworks that we follow in occupational therapy practice.

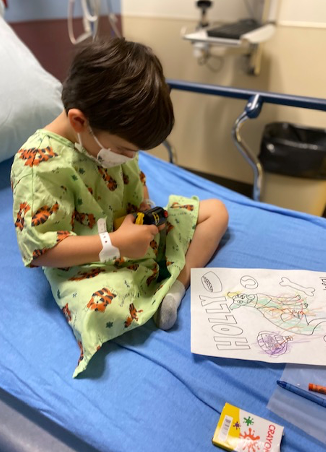

As OTs, play is a top priority and the primary occupation for children, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Little boy coloring in a hospital bed.

It is easy to lose sight of this in hospital-based settings when children are critically ill or frequently come to the hospital. Frequently, the focus is our meeting the primary medical needs of the child, and play is put on the back burner.

In this study, Zengin et al., in 2020, studied the impact of therapeutic play on the levels of fear and anxiety in children (six to 12 years old) following liver transplantation. They found that play significantly decreased levels of fear and anxiety in children. More studies like this are emerging, showing that play can be helpful in unique situations for different children.

Trauma-Informed Care (TIC)

- Abuse

- Neglect

- Disaster experiences

- War

- Disturbing occurrences

(Haertl, 2019)

Trauma-informed care is a systematic approach designed to recognize and respond to trauma and prevent the retraumatization of different populations and individuals. The result of ongoing trauma can result in an increased need for physical-based healthcare services. Many children who have experienced trauma over time may develop chronic health conditions. As OTs, it is essential to remain sensitive to these issues and stay current on best practices and guidelines implemented in each institution. The different types of trauma can range from abuse, neglect, disaster experiences, war, and other types of disturbing occurrences.

In the acute care setting specifically, OTs might work with a child admitted for the first time or after their first time experiencing trauma. OTs may also work with children who have experienced chronic and repetitive trauma over a significant time. Most pediatric hospital-based settings are sensitive to these issues and provide specialized training. It can be helpful to have a representative from the OT department to be a point person to offers specialized and focused trauma-informed care. This is an emerging practice area that is getting more attention, which is a good thing.

Early Mobility

- Growing evidence supporting benefits to early mobility in pediatric populations (Betters et al., 2020)

- Early mobility in infants with acute respiratory failure (Ortmann et al., 2019)

Substantial evidence supports the many benefits of early mobility programs, but much of the research has been done on the adult population. Most things are done in the adult population first and then in pediatrics. More evidence is emerging related to early mobility programs in the pediatric population. Early mobility refers to programs typically driven by occupational and physical therapists to initiate physical movement early in critical illness. In the PICU or the pediatric intensive care unit, where mortality rates are declining, there continues to be a greater focus on quality of life. Research suggests that mobility is one of the most significant predictors of worsening functional decline in children. Early mobility in children can help decrease the burden of immobility and prolonged bed rest in the PICU to promote improved functional status upon discharge and decrease the risk of some of the high-risk conditions. For instance, there are emerging studies related to infants. Ortmann and colleagues looked at clinical vital signs, and infants were held immediately after or soon after intubation in the PICU for better outcomes.

Case Study: Juanita

- 7-year-old female diagnosed with ALL

- Family relocated from Puerto Rico for treatment

- Medical treatment (chemo, RT, port placement)

- Hospital-based school

- OT Process

Here is a case study of a seven-year-old girl, Juanita, diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Upon her diagnosis, her family chose to relocate for her to receive care at a national cancer institution in the US. Her medical care included chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and placement of a port because the medical team anticipated that she would need care for quite some time.

Her care was complicated for multiple reasons. She ended up needing a stem cell transplant, which caused a prolonged hospitalization due to numerous infections. She was immunocompromised and was eventually referred to OT to improve ADL participation and interest in play. The nurse practitioners and team felt that she was not very playful or interested in socializing with anyone. She was a bit more isolated.

The OT used the PedsQL (parent report version) due to her age, and they could use the specific stem cell transplantation version of the assessment. The PedsQL revealed that the mother had concerns about her emotional wellbeing. It also reported that Juanita had a pretty significant decline in physical functioning over the last seven days of the hospitalization. The mother verbalized that she wanted her child to be more engaged in her daily routine.

After the evaluation, the OT collaborated closely with the family, the medical team, and child life to create a schedule for Juanita. The OT ended up seeing Juanita about twice a week to focus on ADL participation so that Juanita could understand what she was able to do. It had been a long time since anyone had challenged her to do things like dress herself, walk to the bathroom instead of using the bedside commode, and standing at the sink to brush her teeth. The OT put a plan to help her gain more self-confidence and self-esteem, as she participated actively in her ADL routine. They also established a play schedule and set up the room to support this. Everybody was on board, including nursing. They moved the room around to allow her access to the floor and a mat, where she was safe to play in a clean space with her toys. Due to her immunocompromised state, they had to prioritize that.

In collaboration with child life, they worked with Juanita to choose her playtime. She could select when specific medical care occurred and decide whether or not she did bathing or dressing in the morning or evening. She was offered a lot of choices regarding her care.

They also put her on a token economy system and other behavioral strategies, like a sticker chart, to help motivate her. The more stickers that she earned, the more opportunities for play that she had. They collaborated closely with the medical team to get approval. If her blood counts were high enough and her immune system was strong enough, we got permission for her to leave the room on days that she had completed all the necessary care. The prize essentially was more opportunities for more movement and engagement as she grew stronger and could tolerate it.

Throughout her OT treatment, we also used strategies like relaxation, mindfulness, deep breathing, taking rest breaks, and energy conservation. Cancer-related fatigue was a barrier to her participation, and she was not quite sure how to overcome that. We explained that cancer-related fatigue was a significant side effect so that she could understand and give her behavioral strategies to save energy for the stuff she wanted to do, like play and interact with others.

Summary

Here are my references. I think it is exciting how many resources are available to us today regarding psychosocial care in hospitalized children with different chronic conditions. In our role as OTs, we have so much to offer, especially in collaboration with other disciplines throughout the hospital. I would love to spend the last few minutes answering any questions. Thanks for your time.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (fourth edition). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2)., 7412410010

Betters K.A., Kudchadkar S.R. (2021) "Mobility in the PICU." In: Kamat P.P., Berkenbosch J.W. (eds) Sedation and analgesia for the pediatric intensivist. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52555-2_21

Chari, Uttara & Hirisave, Uma. (2020). Psychological health of young children undergoing treatment for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 16. 66-79.

Committee on Hospital Care (2020). Retrieved from https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/committee_on_hospital_care

Ernst, K. D., AAP Committee on Hospital Care. (2020). Resources Recommended for the Care of Pediatric Patients in Hospitals. Pediatrics, 145(4):e20200204

Franck, L. S., Wray, J., Gay, C., Dearmun, A. K., Lee, K., & Cooper, B. A. (2015). Predictors of parent post-traumatic stress symptoms after child hospitalization on general pediatric wards: A prospective cohort study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(1), 10-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.06.011

Questions and Answers

What behavioral strategies did you use to help with cancer-related fatigue?

There are many helpful strategies, depending on the age of the child. You can educate them on energy conservation to help them plan their day around treatments that they will receive. Getting this stuff out of the way first thing in the morning may take quite a bit of energy. They may need a nap after. That same child may benefit from having therapy in the afternoon. Some kids are the opposite. It is vital to collaborate closely with the nursing staff to understand the side effects of some of their medications. Some medications have a more immediate impact and can cause fatigue right after. We also need to make sure that the child understands cancer-related fatigue so that they know that we believe them. We know that they are tired, and it is not something they can just push through. We need to help them come up with a strategy. We always need to let the child lead the treatment.

What is the difference between child life specialist goals and OT goals and services?

That's a great question. My understanding of child life is that they focus on meeting the child where they are in that moment. And we do the same thing with our occupational therapy approach. I believe the goals we have are for the child to make progress over a prolonged period during hospitalization. In contrast, child life specialists are on call and intervene at the moment to make a situation as tolerable as possible. We look at prolonged coping strategies to carry out over time to impact functional performance and play.

With adolescent athletes who have suffered traumatic injuries requiring brain surgery, do you have any suggestions to deal with their level of disappointment and depression?

Most of my experience is with adolescents diagnosed with brain tumors. I tried to keep them connected with friends and family and encouraged them to remain active by emailing, texting, or whatever strategy they used to communicate. I would write goals for them to engage in those communications a certain number of times a week. It is crucial to keep up the individual's momentum and connections with the important people in their lives. We can also give them resources for support groups and introduce them to people who relate to their experiences.

How do you handle the parent that either isn't engaged or too protective with the child?

That's a good question. I think that it is so specific to each parent. Going back to learned helplessness, I try to educate families on the importance of not physically doing everything for their child, like putting socks on a ten-year-old or brushing their 13-year old's teeth. Most of the time, they are capable of doing those tasks. I approach it with humor. For example, I have walked in rooms saying, "Oh my gosh, mom. I'm so thirsty. The pantry is down the hall. Do you mind going to get me a cup of coffee or a cup of water?" Wink, wink- I am giving them an out. This works with some families, but for others, it does not. Some families need a little bit more time.

On the other side of the spectrum, some families may not seem as interested or are disconnected. I try to give them specific insight into situations that I may have observed as powerful or point out times that I noticed they helped their child.

What about the parents that are overbearing in treatment sessions?

Each of them is different. I am pretty vocal about things like that. I do not have a problem saying, "This might be more effective if we give 'Sam' space. Sam's going to figure it out on his own, and it's going to trickle down and have a long-term effect. If you keep getting involved and doing it for them, we're not going to get very far." I just try to be honest and tactful while being sensitive to their anxiety level.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (fourth edition). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2)., 7412410010

Betters, K. A., & Kudchadkar, S. R. (2020). Mobility in the picu. Sedation and Analgesia for the Pediatric Intensivist, 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030 52555-2_21

Chari, Uttara & Hirisave, Uma. (2020). Psychological health of young children undergoing treatment for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health,16. 66-79.

Ernst, K. D., AAP Committee on Hospital Care. (2020). Resources recommended for the care of pediatric patients in hospitals. Pediatrics,145(4):e20200204

Franck, L. S., Wray, J., Gay, C., Dearmun, A. K., Lee, K., & Cooper, B. A. (2015). Predictors of parent post-traumatic stress symptoms after child hospitalization on general pediatric wards: A prospective cohort study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(1), 10-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.06.011

Haertl, K. (2019). Coping and resilience. In C. Brown, V. C. Stoffel, & J. P. Muñoz (Eds.)., Occupational therapy in mental health: A vision for participation (2nd ed). F. A. Davis.

Hall, T. A., Leonard, S., Bradbury, K., Holding, E., Lee, J., Wagner, A., Duvall, S., & Williams, C. N. (2020). Post-intensive care syndrome in a cohort of Infants & Young Children Receiving Integrated Care via a pediatric critical care & neurotrauma recovery program: A pilot investigation. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1797176

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2019). Standards of practice for pediatric palliative care: Professional development and resource series. Retrieved from: https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Pediatric_Standards.pdf

Ortmann, L., & Dey, A. (2019). Early mobilization of infants intubated for acute respiratory failure. Critical Care Nurse, 39(6), 47-52 ctice. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Wiener, L., Canter, K., Long, K., Psihogios, A. M., & Thompson, A. L. (2020). Pediatric psychosocial standards of care in action: Research that bridges the gap from need to implementation. Psycho-Oncology, 29(12), 2033–2040. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5505

Zengin, M., Yayan, E. H., & Düken, M. E. (2021). The Effects of a Therapeutic Play/Play Therapy Program on the Fear and Anxiety Levels of Hospitalized Children After Liver Transplantation. Journal of perianesthesia nursing : Official journal of the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses, 36(1), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2020.07.006

Citation

Stimler, L. (2021). Psychosocial considerations in the pediatric acute care hospital setting. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5463. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com