Erik: Thank you to all of the audience members out there that are listening today. I am super excited to be able to talk about the military and occupational therapy. The information that I express in this presentation should not be taken as representing the policies and views of the Department of Defense, its component services, or the United States government. These are from my experience as an occupational therapist in the Army.

I always like to start out my presentations with this quote by Steve Jobs. "Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied, is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven't found it yet, keep looking. do not settle." This resonates with me so much because if you love your job as an OT, you are going to do great work. You are going to help people, and you are going to see it as much more than just a job. Occupational therapy has a unique way of being able to change clients for the better, whether it be for a physical disability, a cognitive deficit, or developmental disability. We all can empower somebody if we choose.

Army OT Focus Areas

Let's look at the Army OT focus areas.

- Behavioral Health

- Neuromusculoskeletal Evaluation and Treatment

- Physical Disabilities

- Inpatient/Outpatient

- Work and Community Reintegration

- Ergonomics

- Burn Rehabilitation

- Amputee Rehabilitation

Typically, in the military, we do not see pediatrics as a specific practice area. The Navy does dabble in it, but you do not see it as much. A lot of this presentation that I give will be from my experiences as an Army occupational therapist. If you are looking to be an OT in the military, I encourage you to look at all branches and look at what they have to offer. I will also be more than happy to talk to you about each of these areas if you are interested.

During World War I, occupational therapists started out as a reconstruction aidea. Reconstruction aides were originally brought in because many soldiers had "shell shock" or combat stress. The idea was that you pull the soldier off the front line, engage them in activity, and help them decompress, and then reengage. We teach that this is a normal reaction to an abnormal situation. Today, this has changed a little bit, and we have added some things to it.

Mental Health & Combat Operational Stress Control

Mental health is probably still the number one thing that we tackle as a military occupational therapist. The role of the OT in a combat and operational stress control unit is to evaluate the occupational performance of soldiers adversely affected by combat stress reactions and to implement interventions that enhance performance. The two key things are to evaluate and enhance. You identify a stress reaction, whether it is anxiety, depression, or anything that could be potentially compromising their ability to be a soldier, you pull them offline, normalize things, engage them in occupation, and get them back out to the fight.

This is done four different ways.

- To enhance adaptive stress reactions

- To prevent maladaptive stress reactions

- To control stress reactions

- Identify and manage behavioral disorders

We want to enhance their adaptive stress reactions. These are all the good ones. We want to prevent their maladaptive stress reactions, or the bad ones. Overseas, while you are deployed, you are not allowed to drink. We find soldiers that struggle with some of these things end up having some of these maladaptive stress reactions. And we want them to be able to control their stress reactions. We want to pull them back, teach them some good adaptive stress reactions or ways to control that, and then be able to reengage them. We also want to control their current stress reactions and identify and manage behavioral disorders. We are not the only ones treating mental health. There is a huge team that includes psychologists, psychology nurses, technicians, and behavior health people. Of course, the OT is a huge part of that.

Buy-In

No matter what setting that you are in, you are not going to be an effective therapist if you do not have buy-in from the client. You need to understand your patient before you do any of any kind of therapy. The initial interview is my number one tool. When a patient comes in to me, I always want to see what makes them tick. If I do not understand them and complete a treatment plan without that information, then I have already lost the game. If you have a patient that is very somber and withdrawn, then you need to be calm and encouraging for them. I always look at different ways to engage with the patient and also look at generational differences. In the military, we use community reintegration activities and leisure exploration. We will get into some of those in a little bit.

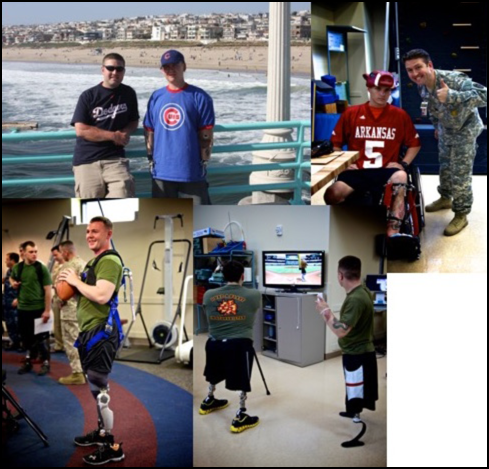

Figure 1 and 2. Examples of activities.

Even doing something simple like playing root beer pong in a clinic can be both purposeful and therapeutic. Remember, these are 18- to 35 year old soldiers. For example, the guy in the orange, in the top picture, is a double amputee and is working on both balance and weight shifting.

Upper Extremity Orthpedics

Our outpatient rehab ends up being fully encompassing. While the soldiers are our number one clients, we also see family members and retirees. We could see a teenager that has a distal radius fracture or a retiree that has a hip replacement. There are many different things you can do in ortho outpatient to be creative. In your clinics, you have the ability to pretty much order what you want. Why not get different color splinting material? I am a firm believer that if a patient can enjoy the splint that they are wearing, then they are going to wear it a lot longer. If you do not have somebody that is compliant with your treatment plan or your wear schedule, then what is the point of even doing it? Make it fun for them and give them a reason to want to wear it and show it off. Some examples are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Examples of different splints.

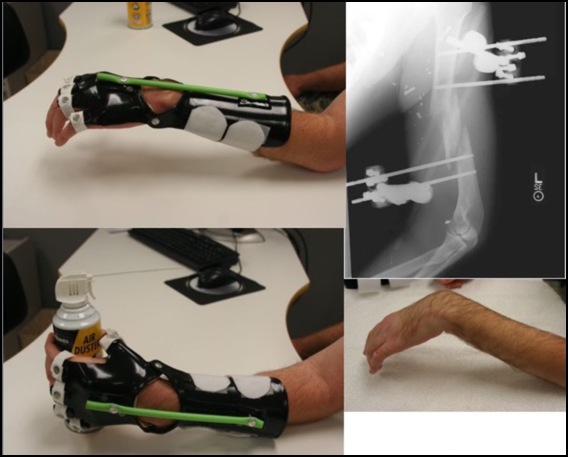

Unfortunately, we also see a lot of complex polytrauma. In Figure 4, this patient had a humerus fracture with an accompanying radial nerve injury. Your typical radial nerve palsy splint would have a very bulky outrigger. However, I wanted to give him something that he could wear out in public that would not get caught on something. I call this my Darth Vader splint.

Figure 4. Darth Vader splint.

I know what you are thinking, "No! That green light saber is more of a Luke Skywalker-type thing. Darth Vader has a red light saber." I need you to work with me here. This splint also has a component for wrist motion. It also has a traction for each individual finger to be pulled back into extension, but the flexion he could do on his own. I knew this patient was going to go back to a rural area where he would not have access to stores. I needed to make something durable, but also use materials that he could easily find and replace if needed.

Splinting

ADLs

One gentleman I worked with had eight gunshot wounds and bilateral radial nerve palsies on both sides. I approached him and said, "What can I do for you right now?" There were a lot of things we could not do. He had wound vacs all over the place--I think 4 at the time. He was not allowed to use his arms or legs. I wanted to find things to make him feel a little more human. One thing he identified was to be independent in getting a drink of water in the middle of the night. Figure 5 shows how I incorporated a Camelback on to his splint so he could get a drink at night.

Figure 5. Incorportating a Camelback on splint.

I thought that if I could get on his good side, then when I had to do something that was painful, he would be more willing to work with me. He also identified that he wanted to be able to answer the phone. This was before smartphones. We used a traditional phone with a speaker. We set it up so he could tap the speaker function when someone called. I later called at the hospital and was so excited that he could answer the phone. Some of these things are simple, but by getting them on your side and developing a relationship, this can help you down the road as therapy gets more difficult.

Driving

I also look at driving because it allows increased independence. One soldier, after getting hit by a roadside bomb, wanted to be able to drive stick shift again. He was unable to grab the gear shift, but by getting creative, we were able to create the splint in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Adapted splint for driving.

For this particular patient, we adapted this splint to his actual vehicle, and he was able to do his road trip.

Leisure Activities

We can also look at their leisure activities. For this same patient, he lost his pinkie. Now, I do not know how many musicians we have out there, but I play saxophone myself. One of the things that I could really appreciate in this particular patient is that he needed his pinkie to hit G sharp. To complete this maneuver, we created a "pinkie" out of splinting materials (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Adapted splint for saxaphone playing.

This client could not put his right fingers on the frets of a guitar and strum at the same time. I made him this splint in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Adapted splint for guitar playing.

I also made him a trough with dysem to help him old the guitar.

Many of our lower extremity amputee patients are unable to perform cardiovascular exercises. We can use recumbent bikes or hand bikes. I was able to make this adapation for his bike in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Adapted splint for exercise.

This is another example of adapting a leisure activity in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Adapted equipment for golf.

These are all examples of how we can adapt activities for full participation.

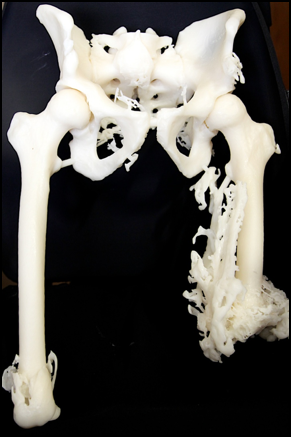

Amputee Care: Pre-Prosthetic Training

There is a common misconception that amputees are the number one type of clientele that we see, and that is not necessarily always the case. We only have a small population of therapists that work with amputee patients in the three big military rehab sites: Walter Reed, San Antonio, and Balboa in San Diego. Amputee care is tough as you never know what you are going to see. It is important to engage the patient to be as independent as possible. Of course, both PT and OT work hand in hand together to make that happen. I am not going to go too in-depth in amputee care right now because we have a speaker later in the week who will be talking very specifically on amputee care. I am going to do an overview of amputee care in general and then kind of work from there.

Often, they come to us with fresh wounds. We cannot have them use a limb that is not healed. Typically with our lower extremities, it is going to be a little bit longer wait. You can anticipate probably about six weeks before they are even allowed to be fitted for a prosthetic for their lower limbs. The upper extremity is similar in that we cannot just throw a prosthetic arm on there until we start seeing the limbs take shape and see those wounds close.

There is also some splinting involved, as shown earlier, to enable patients to be independent. It is important to give them independence without a prosthesis in case of breakage or if they want to do something quickly. Here is an example of some ADL training in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Splint use for ADLs.

They need to understand what they can do with the limbs that they have.

Video 1: The Dino

In this video, I want to show you how a patient, who is a quad amputee, can conduct toilet hygiene without using prosthetics. Let's take a look at it.

You can see he is struggling here and there, but overall he is doing pretty well. It is just a matter of being patient.

Amputee Care: Prosthetic Training

Prosthetic training is going to include a lot of different things. I tell my clients to think of it as a bonus if they are able to wear a prosthetic effectively. Our goal is to be able to get them to the point where they are comfortable with their prosthesis. The goal is that it feels like their limb, they want to use it, it is functional for them, and it empowers them. During prosthetic training, we look at both fine and gross motor activities.

Video 2: Donning a Prosthesis

You can see in the video that he has obviously done this once or twice before. Again, we want to encourage independence. One of the great things about our amputee programs in the military is that our prosthetists are right there on site. We can easily collaborate. Typically, they can make immediate adjustments as needed.

As a patient gets further along in treatment, we want to start challenging them. I am going to show you a video of a patient who was a medic in the military. He lost his dominant arm and leg in a roadside bombing. He told me that he wanted to deploy again as a medic. We needed to see how effective he could be in that same role as people's lives would be on the line. We also needed to provide opportunities so that he could figure things out for himself.

Video 3: Starting an IV

First, we set up tasks to simulate what he might encounter in the field. This particular patient was convinced that he was going to be able to go back in there and do everything he was able to before. My thoughts were how his clients were going to feel and whether they thought he could take care of them. What happened if his leg went out?