Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, School Based Occupational Therapy For Post Concussed Youth An Occupation Based Framework, presented by Jennifer Morgan, OTD-PP, OTR/L.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify a holistic, client-centered, occupation-based framework that school-based OTPs can apply to service provision for post-concussed youth within the educational setting.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize 5 physical, cognitive, and emotional attributes of lingering post-concussion syndrome that often leads to occupational withdrawal and occupational imbalance with educational activities.

- After this course, participants will be able to list two occupation-based assessments and two occupation-based interventions that school-based OTPs can apply to service provision.

Introduction/Case Study

Thank you so much for joining me today. I'm excited to share this information with each of you. On a personal note, I'm also thrilled to let you know that this framework will be published in an upcoming article co-authored with my capstone mentor, Dr. Alicia Scutan. Be on the lookout for it in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy—Volume 79, Issue 3.

We have a lot of content packed into this webinar, so without any further delay, let’s dive in by taking a quick look at the case study of Robbie. You’ll find Robbie’s case study included in your handouts for future reference, but let’s highlight the key points together.

Robbie collided with another player during a basketball game. He fell and hit his head. Later that evening, he developed a headache, took Tylenol, and went to bed. Robbie woke up with a headache but chose to go to school anyway. As the day progressed, his symptoms worsened. The headache intensified, he felt nauseous, and he had trouble thinking clearly. His mother took him to the pediatrician and explained the incident that occurred during the basketball game. Robbie was diagnosed with a concussion.

His educational team was promptly notified, including his teachers, coach, and you—his school-based occupational therapy practioner.

Problem Statement

As a school-based occupational therapy practitioner (OTP), you might ask yourself the following questions: What best practice intervention approaches would support Robbie’s participation in learning if learning barriers were identified? What is the role of the school-based OTP in concussion management? How would the school-based OTP assess Robbie? And what would Robbie’s intervention look like?

You may feel stuck answering these questions as a school-based OTP—and for good reason. Despite the advancement of occupational therapy management for concussion, there is no clear framework guiding school-based OT practitioners in implementing a holistic intervention approach. One that identifies environmental factors influencing recovery and considers the delicate balance between rest, symptom monitoring, and the student’s unique activity choices.

In addition, research on school-based occupational therapy provision for post-concussed youth remains limited, and currently, there is no established clinical guideline specifically tailored for school-based OT practitioners.

The information I’m going to share with you today will provide a strong foundation for supporting students like Robbie to fully participate in school. With this framework, you'll be able to confidently answer the questions posed earlier.

The first step in demystifying the role of school-based OTP in supporting post-concussion student recovery is to review the practice guidelines and legislation related to providing school-based services. Star this slide as a reference.

Practice Guidelines and Legislation Relating to School-Based OT

AOTA clearly defines the role of school-based occupational therapy through its guidelines for OT services in early intervention and schools. These guidelines are shaped by key legislative influences, including the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEA 2004), the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 (ESSA), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 2004, and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Under IDEA 2004, school-based occupational therapy is defined as a related service that may be provided to prevent impairment or loss of function and to improve, develop, or restore functions that have been impaired or lost due to injury, illness, or deprivation. ESSA also plays a vital role in reinforcing the significance of school-based occupational therapy, recognizing the OTP as an essential member of the educational team in the capacity of a SISP—spelled S-I-S-P. SISP stands for Specialized Instructional Support Personnel. As SISPs, occupational therapy practitioners work to promote occupational performance in at-risk students with high needs, using targeted instruction and evidence-based practices to support successful school participation and outcomes.

The Guidelines for Occupational Therapy Services in Early Intervention and Schools, developed by AOTA, further emphasize the role of school-based OT practitioners at the systems level. These practitioners help identify a child’s current performance in their occupations, examine both the affordances and barriers to successful engagement, and collaborate with parents and school staff to understand their priorities and concerns in order to develop meaningful and individualized goals for the child.

mTBI

Definition

The CDC defines a mild traumatic brain injury, also known as a concussion, as a bump, blow, or jolt to the head—or a hit to the body—that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth within the skull. This sudden movement can cause the brain to bounce or twist inside the skull, leading to chemical changes in the brain.

Clearly, a mild traumatic brain injury can result in impairments that call for the knowledge and expertise of the school-based occupational therapist as a related service provider. In this role, the OT supports the post-concussed student by helping them overcome barriers to learning through strategic adaptation and modification.

Please go ahead and star this slide as well—you’ll likely find it helpful to review later.

Prevalence

Concussions are prevalent among youth under the age of 17, with 3.2%—or approximately 2.3 million children and adolescents—having ever received a diagnosis. However, this reported prevalence may significantly underestimate the actual incidence of mild traumatic brain injury. Several factors may contribute to this underreporting, including parents choosing not to seek care, limited accessibility to healthcare services, the availability of qualified providers, lack of insurance coverage, or lack of access to reliable transportation.

Please take a moment to place a star or make a note on this slide so you can revisit it later.

Burden of Injury

Although methodologies for capturing the prevalence of pediatric mild traumatic brain injury may vary, these prevalence estimates are valuable in raising awareness about the burden of pediatric concussion and in informing clinical care practices. Older children and adolescents show a higher prevalence of concussions compared to younger age groups. Boys generally have a higher prevalence than girls. Among youth athletes, those participating in high-contact sports—often dominated by boys—exhibit the highest rates of concussion. However, in gender-comparable sports such as soccer, females experience a higher rate of concussion.

Symptoms

Concussed youth may experience a wide range of neurological, physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms. I recommend placing a star or notation on this slide as well, so you can easily review the symptoms of concussion later.

Concussion symptoms can be categorized as executive dysfunction impairments and may present as difficulty completing novel tasks, identifying and correcting errors, planning and prioritizing, setting goals, organizing, problem-solving, concentrating, self-monitoring, orienting, and memory challenges.

If you look at the middle column of the slide, you’ll see the physical symptoms often include headache, dizziness, nausea, fatigue, sleep disturbances, sensory sensitivity to sounds, and visual disturbances.

Finally, the far-right column lists the emotional symptoms of concussion, which may include depression, anxiety, and difficulty identifying and describing feelings.

Recovery Rate

Concussion symptoms typically emerge within the first seven to ten days following an injury and generally resolve within one-month post-injury. However, in some cases, symptoms can persist beyond this period. Post-concussion syndrome is characterized by lingering symptoms that can last longer than three months and, in some instances, up to a year.

Interestingly, the onset of prolonged post-concussion symptoms does not appear to be directly related to the severity of the initial injury. The primary goal of treatment in these cases is to manage symptoms effectively while working to improve overall function and quality of life.

Influence on Occupational Performance

Lingering post-concussion symptoms can lead to a short- or long-term disruption in a youth’s participation in meaningful occupations—activities that are often deeply tied to their sense of identity. When symptoms persist, post-concussed youth may withdraw from or become hesitant to re-engage in the occupations they participated in before the injury. This hesitation is often driven by self-perceived concerns about the risk of re-injury or fear of worsening their symptoms.

Occupational Imbalance

Consequently, occupational imbalance may occur—a mismatch between what the youth can do, how they use their time, and how satisfied they feel with their daily activities. This imbalance can also result from limited access to resources or opportunities available to them.

Considering occupational imbalance is especially important in post-concussed youth, as it can prolong the recovery process and contribute to a range of negative outcomes, including depression, anxiety, social isolation, loss of academic standing, and physical deconditioning. In this way, occupational imbalance becomes a key determinant of poor health in this population.

Occupation: A Health Promoting Strategy

Occupational therapy practitioners play a critical role in promoting healthy lifestyles by emphasizing participation in occupation as a strategy to support overall well-being. Health-promoting interventions can include occupation-based activities that re-engage youth in meaningful routines and support their recovery.

The Role of School-Based OT in Concussion Recovery

In this framework, the school-based OTP uses occupation-based activities to guide post-concussed youth in discovering or developing new skills and capacities while nurturing ambition by focusing on their available resources, existing capabilities, habits, and skills. The goal is to support their ability to adapt to their environment meaningfully. This process of enabling “doing” through occupation introduces the concept of “becoming,” which refers to the journey toward reaching one’s highest potential for personal development. It involves an evolving sense of self-actualization and self-esteem—both of which are critical to consider during post-concussion recovery in youth.

This framework centers on enabling the process of resuming “doing” for post-concussed youth through occupation-based activities. It embraces a holistic approach to promote health and enhance quality of life during recovery.

To ground this framework, I’ll begin by describing the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, 4th Edition (OTPF-4).

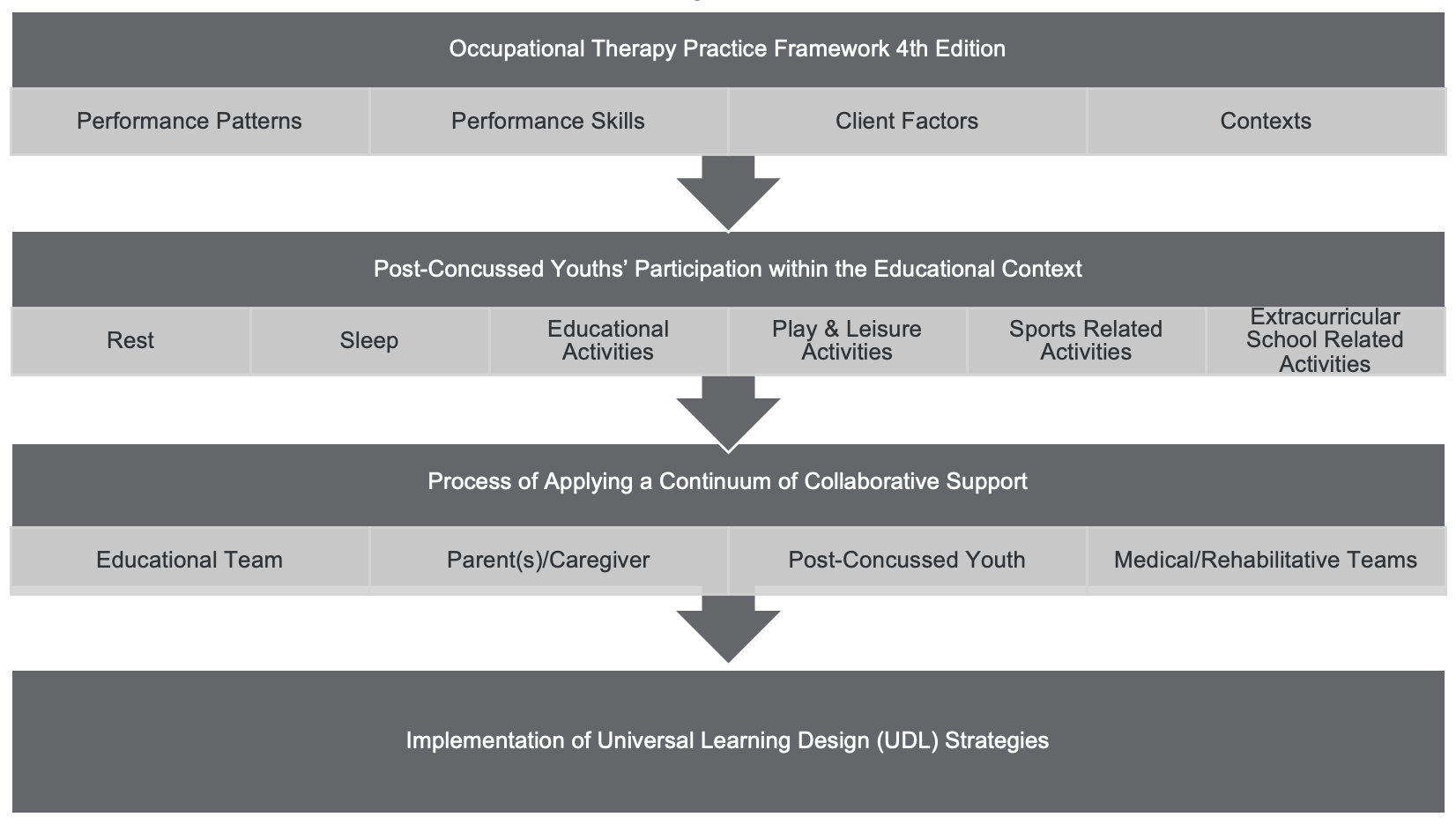

The OTPF-4 outlines the scope of occupational therapy practice and highlights the unique characteristics central to an individual’s being, which work together to support engagement in meaningful activities. I’d like to draw your attention to the top row of the diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of the Role of School-Based OT in Concussion Recovery (Click here to enlarge the image).

The OTPF-4 identifies distinct elements—performance skills, performance patterns, client factors, and context—as critical components that shape a post-concussed youth’s identity, desires, and capacity to participate in occupations within the educational setting.

Now, follow the arrow to the second row of the diagram. We’ve learned that post-concussed students often experience physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms that disrupt their engagement or challenge their performance in leisure, sports, and educational occupations.

In addition, lingering post-concussion symptoms may interfere with the occupational categories of rest and sleep, both of which are foundational for success in educational and daily activities.

Let’s move down to the third row of the diagram. Here, the school-based OT practitioner brings expertise in applying the OTPF-4 to develop educationally relevant intervention strategies. These strategies aim to facilitate safe re-engagement in educational activities and are delivered through collaborative relationships with educators, parents, and the broader medical and rehabilitation teams supporting the youth’s recovery.

Universal Learning Design for Post-Concussed Youth

The school-based OTP is well-positioned to assess the performance skills, performance patterns, client factors, and personal and environmental contexts that influence a post-concussed youth’s engagement within the educational setting. Based on this comprehensive understanding, the OTP can then implement interventions that enhance participation in learning by developing universally designed learning (UDL) strategies.

In the final row of the diagram, UDL strategies may include modifications to instructional materials, learning activities, and the physical or sensory aspects of the learning environment. These adaptations are aligned with the evolving capabilities of post-concussed youth during their recovery phase to support meaningful and sustained engagement.

In addition to classroom-based supports, the school-based OTP can collaborate closely with the post-concussed youth and the medical and rehabilitation teams to modify team roles and guide safe participation in team drills. These activities are intentionally kept below the youth’s symptom threshold and are adjusted throughout the recovery process to promote gradual re-entry and prevent symptom exacerbation.

Variations in Post-Concussion Care

I want to highlight that variations in post-concussion care can significantly influence a youth’s recovery. In 2019, Wildgoose and colleagues reported that post-concussed youth often experience stress when returning to school, largely due to a lack of educator awareness, inconsistent messaging from educators, and wide variations in both the type and amount of accommodations offered.

When the school-based OTP forms strong collaborative relationships with the medical, rehabilitation, and educational teams, these variations in care can be mitigated. This coordinated approach helps ensure a safer and more effective return to meaningful educational activities for the post-concussed youth.

This collaboration is particularly important in light of recent research efforts aimed at developing best practice guidelines for concussion management, especially as they relate to resuming participation in both sports and learning activities.

Collaborative Care

Collaborative care is widely recognized as a best practice approach in supporting post-concussed youth during recovery. Numerous sources have emphasized that optimal outcomes are achieved when a multidisciplinary team manages post-concussion rehabilitation, including addressing limitations in occupational performance.

This collaborative team should include the parent or caregiver, the post-concussed youth, school administrators and educators involved in the student’s learning, and medical and rehabilitation service providers. By working together, this team can ensure a coordinated, consistent, and supportive approach that promotes safe and meaningful re-engagement in educational and daily activities.

Concussion Protocols

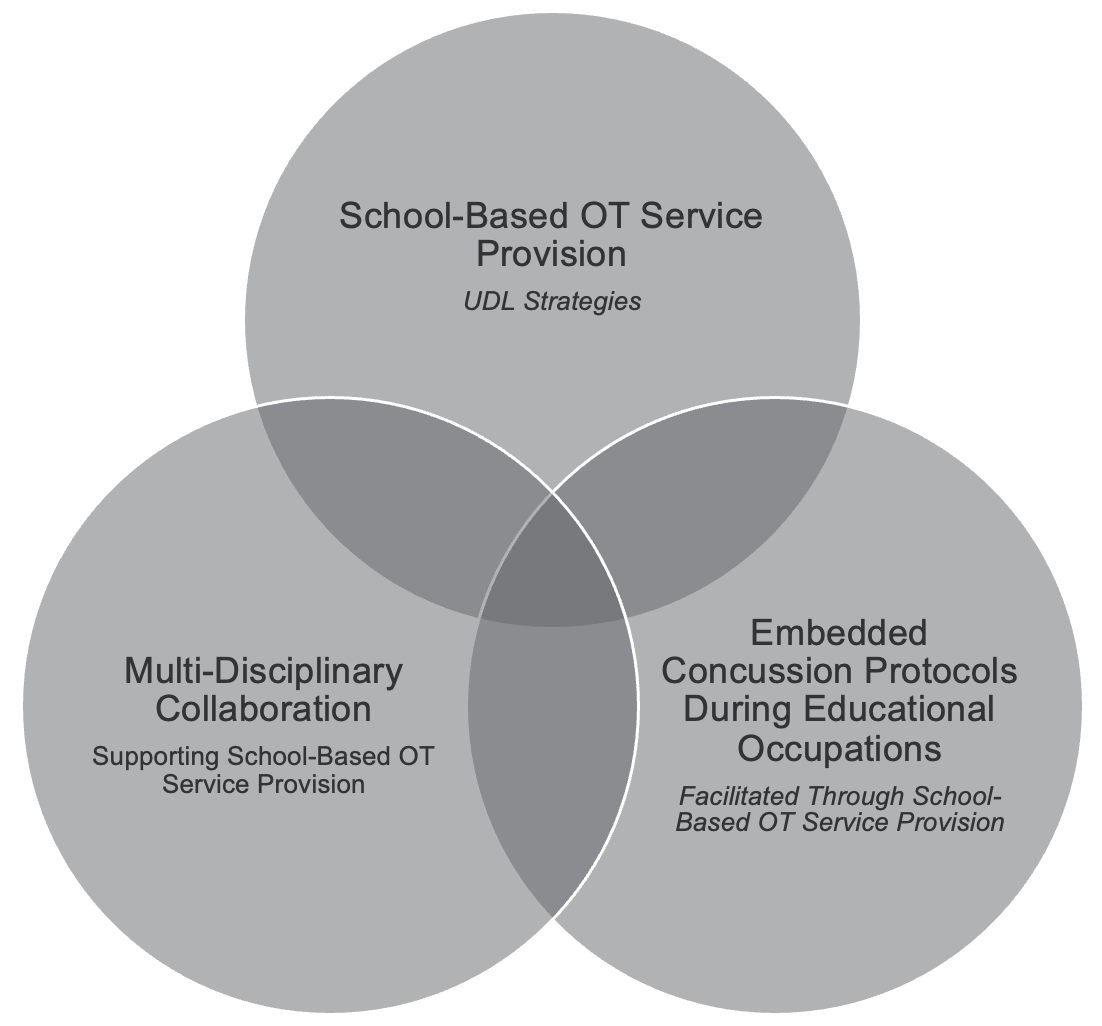

Figure 2 represents the overlapping components that are essential to post-concussion recovery.

Figure 2. Overlapping components of concussion protocols.

The school-based OT practitioner plays a key role by embedding updated concussion protocols into educational activities and implementing universally designed learning (UDL) strategies that support and enhance the participation of post-concussed youth in the school environment.

These interconnected aspects of school-based OT service provision emphasize the critical importance of multidisciplinary team collaboration. By working closely with educators, medical professionals, and families, the school-based OT helps to reduce inconsistencies in post-concussion care and ensures a more cohesive, supportive approach within the school setting.

Concussion Protocols Emphasize Return to Occupation

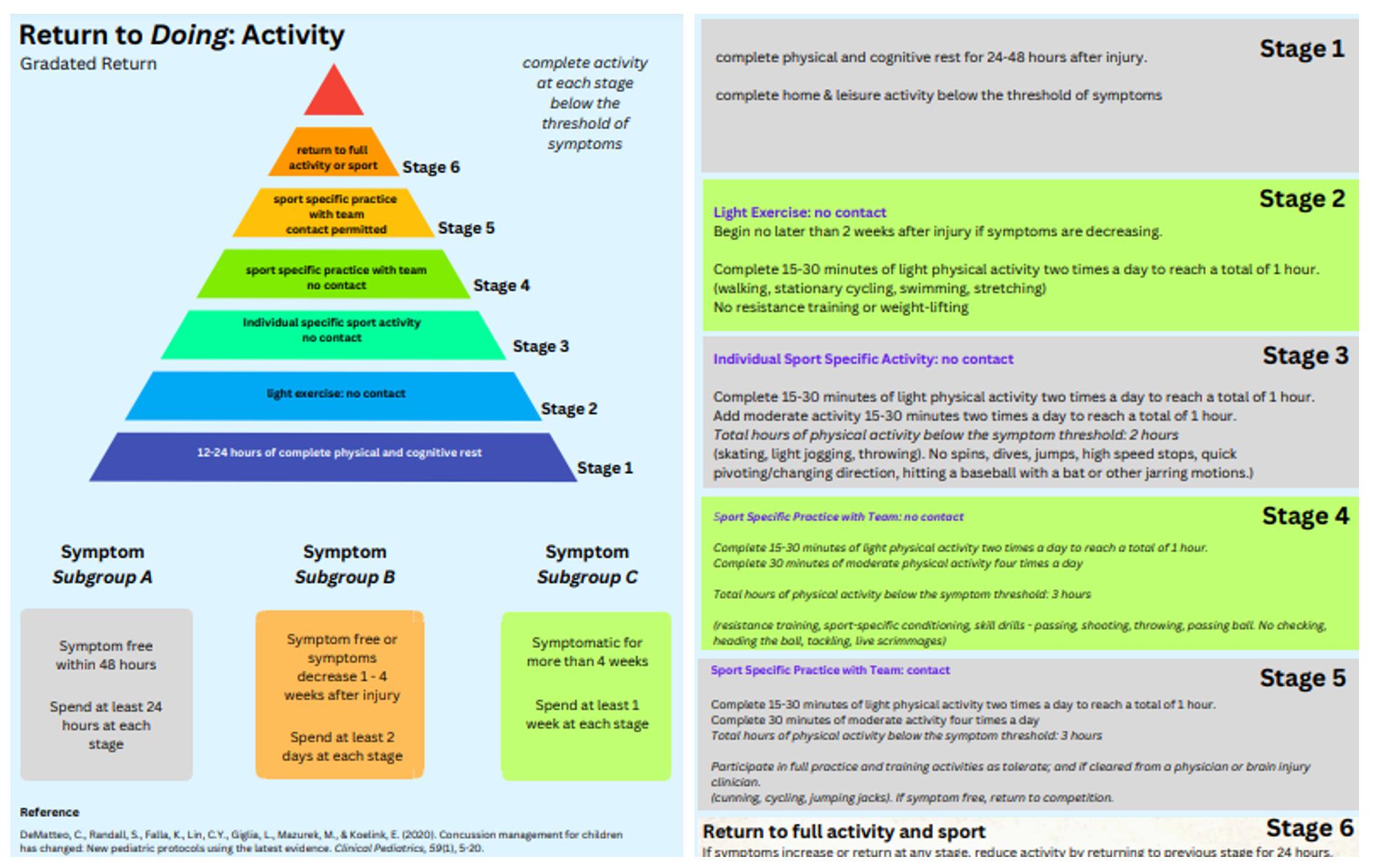

Let’s take a moment to review the updated concussion protocols. These new guidelines emphasize a shortened period of physical and cognitive rest—typically 24 to 48 hours—followed by a gradual return to occupation. This approach encourages post-concussed youth to re-engage in light, symptom-guided activity, including aerobic exercise.

The updated protocols highlight the typically rapid recovery rate seen in youth when appropriate interventions are implemented. These interventions not only support safe re-engagement in meaningful occupations but also recognize the psychological benefits that come from participating in educational activities. Reconnecting with tasks that the youth love, want, and need to do promotes a sense of social belonging and supports their emotional well-being during recovery.

Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the phases recommended for Return to Doing.

Figure 3. Graphic of the phases of Return to Doing (Click here to enlarge the image). (Developed by Morgan & Skuthan, 2024).

This also encompasses physical activity and sports. You’ll have the opportunity to spend more time familiarizing yourself with this handout after the webinar. However, one key point I want to highlight is that these handouts align with the CDC’s updated concussion protocols. They were developed based on my review of the 2020 linear study and systematic review by De Matteo and colleagues, published in the Journal of Clinical Pediatrics.

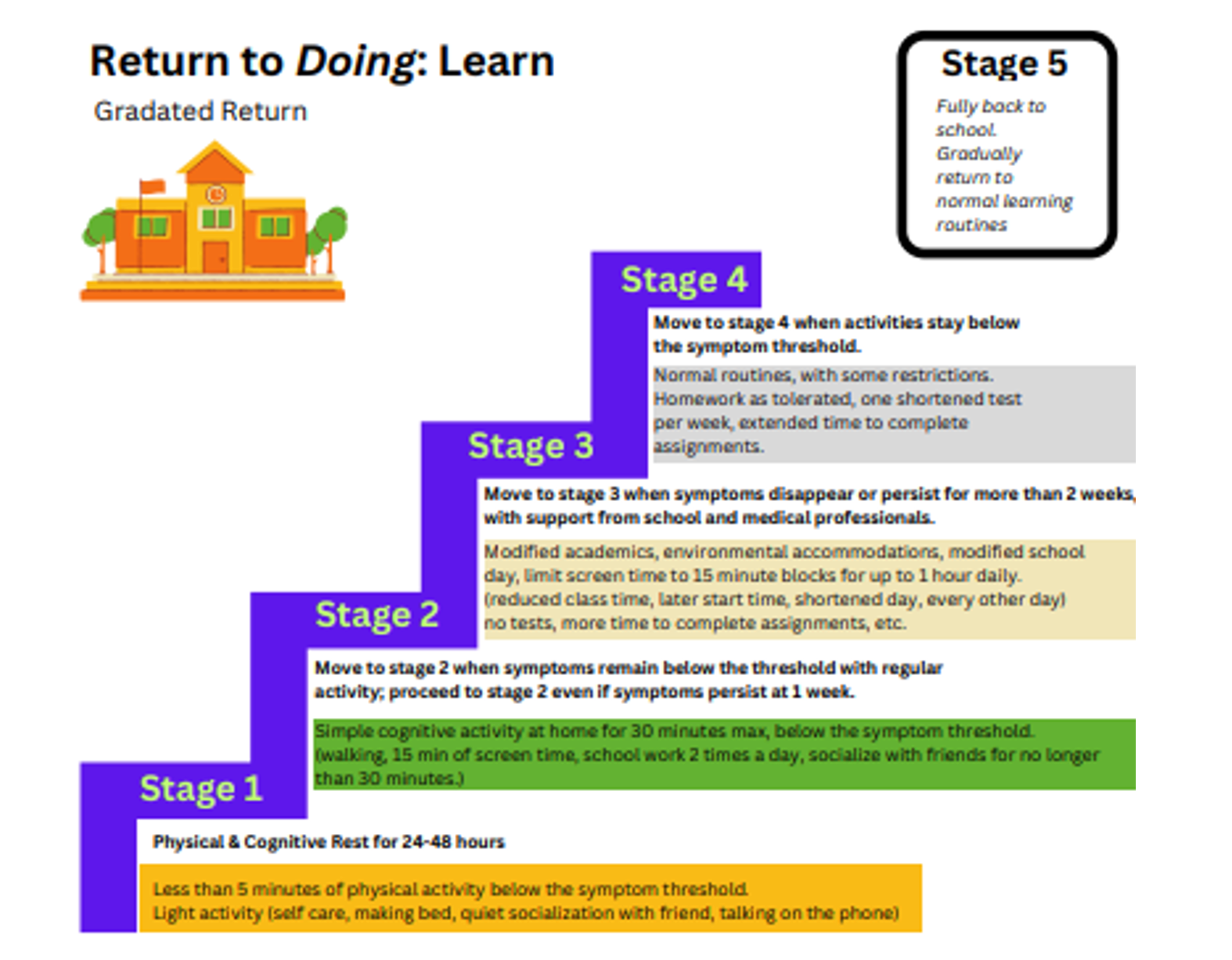

It’s important to note that Return to Learn protocols differ slightly from Return to Play protocols, as seen in Figure 4. As I mentioned earlier, this visual aid is included in your handouts, and you’ll have more time after the session to explore the stages of Return to Learn in greater detail.

Figure 4. Graphic of the phases of Return to Doing (Click here to enlarge the image). (Developed by Morgan & Skuthan, 2024).

However, I want to draw your attention to an important detail—if you look closely, you'll see that it’s recommended for the student to continue progressing up the ladder by actively engaging in meaningful learning occupations as long as they remain below their symptom threshold.

These visual aids can be especially helpful when discussing your role with post-concussed students, administrators, educators, parents, and coaches. In the school districts where I work, I use them regularly as a quick-reference knowledge tool. They help facilitate a shared understanding of the principles behind a graded return to learn and play.

Video: Ivy

Now, I want to share with you Ivy’s experience with lingering post-concussion symptoms. Ivy reflects not only on how her symptoms impacted her ability to learn but also on the emotional aspect of recovery—an element that may not always be fully understood by parents, educators, and professionals who support post-concussed youth.

Hi Ivy, thanks so much for joining me on this interview. I just wanted to make sure you're giving consent for this interview and you are willingly sharing this story with other occupational therapists so that they can understand their role in school-based therapy and how they can help first concussed student recovery. Yes, absolutely. Thank you. Ivy, can you tell me a little bit about how you sustained your concussion?

I actually had three concussions, so most of my middle school time had a concussion. They were all sports related. So the first one, a girl, there was a stampede, I guess you could describe it in basketball, and she went to grab something to stop herself from falling and I went in for a layup and she grabbed my leg and my head hit the floor.

At that point, they didn't really know much about concussions. School perspective wise, they. Because they were like, hey, Tammy, you might want to take her to the hospital. Talking to my mom just like, hey, we don't. She did hit her head pretty hard.

We don't want anything to happen at that point. My mom thought I was fine, so we just kind of would go with the flow. She woke me up every 30 minutes or so. Just make sure I was still conscious.

Other two concussions were in soccer, and those were both just body hits. And I hit the ground hard. So. Okay. What were some of the symptoms of your concussion?

Light sensitivity was a big one. I had almost a constant headache, so it would get worse or better throughout the day. I will say anything I struggled with in school became harder. So anything like my dyslexia, adhd, stuff like that, it all almost became heightened. So things that were hard for me already became almost harder or like I had to think more about how to do those things.

So that was something that really affected me in school. Okay. Noise. Oh, noise. Noise was a big one.

Classrooms were. And you know, you're in middle school, classrooms are kind of loud at some points in time. That one really affected me too. So it was mainly noise and light. Okay.

Did you feel as if your brain was foggy in the way you could think or did you feel tired? I often did feel tired during the day. If I had a study hall, I'd take a nap. So. And I had a great teacher who would let me thank goodness, or she'd let me go to the nurse to take a nap.

I. There were points in the day where I'd feel foggy. So there were some times I could start taking a test and I'd feel perfectly fine. I know the answers. And I'd start taking it and everything would kind of just like.

That makes sense. Just like kind of wipe away. Like it started getting foggy and I just stopped. I almost stopped remembering what I was doing. So that was something that happened every once in a while.

Okay. Did you have a difficult time remembering previously learned material, like from the day before or from the week before when you had to take tests?

I will say I do remember memory issues of learning, like, things quickly. I will say I.

I have a little bit of long term memory issues. So, like, I can tell you some things that have happened, but also you kind of prompting me does help. I don't really remember everything that happened during that time. I'm doing EMDR with a Therapist to try and bring back some of those memories. Just because brain injury was traumatic, and I've lost some of those memories.

Okay. Do you feel as if the symptoms that you experienced in school would have affected your personality because of a challenge and being. Or just experiencing those physical symptoms that you just mentioned? My. Anybody around me would have said I was a lot more grumpy, I was very moody.

Anything would probably have set me off. And I would say I'm generally a happy person. So to, like, kind of snap on somebody is not typical. But I did become very moody. Moody.

Would you say that would be agitated or frustrated or anxious? Probably agitated and anxious, mostly. Like, I was almost always waiting for something to happen, but anything that did happen would, like, make me upset. Do you feel like all of these symptoms affected your ability to perform in school in some way? Did you feel.

Were there any activities related to school that were challenging for you?

I think there were certain classes. Like, again, if there was a class that was already challenging to me, it almost came impossible to, like. Science was not my strong suit, and science became something that was really difficult for me. I will say, during one of my concussions, they did put me on homebound for a month, and that was something. It went kind of both ways.

It benefited and also, I think, stunted. I think it benefited because I was resting my brain more. I wasn't around those loud sounds or the lights. But I also got a little bit more sad at that point in time because you were supposed to be resting. So I'd only seen my family for that whole month, and I'd see the one teacher who would come to see me, and that's all I did for a whole month.

So the homebound helped me in that way, but in the way of I had essentially isolated myself, which my mom was trying to do what she thought the doctors needed me to do, which was just complete. I. Like, she put me in the living room and close all the blinds and, like, make it really dark and stuff. And we would just sit there and play war. And that was, like, all I did for a whole month.

That one. I will say it did help my brain heal mostly. I could also mention that on that point in time, when I was on homebound, I wasn't taking Adderall. So I was prescribed Adderall for school, and I was told by a neurologist to continue to take this medication, like, normally, not realizing that it was stimulating my brain while I was trying to heal. And that was not helping me recover.

So when I went on homebound and stopped taking that medication. It did help my brain heal. Okay, thank you for sharing that. Do you feel as if copying from the board or reading or writing was impacted by your concussion symptoms? I will say copying from the board was something really difficult.

I think it goes again with kind of lighting. I'm not sure what was different, but at that point in time I could almost and I'd be right at the front. I would sit right in front of the board and I almost couldn't see it. I don't know if it was blurred vision or if it was a glare or what it was, but I had a really hard time copying and I just got notes from friends, so. Okay.

And would you say you felt satisfied with your performance during your concussion or was that an area where you might have needed some extra support to manage your symptoms during your recovery? In school?

I do think I had additional support and that's the reason I do feel satisfied with it. So I did have that additional support and I think I did the best I could with how my brain was at okay, Ivy, thank you so much for sharing your experience with concussion in school. I know that there's going to be a lot of knowledge gained from this interview so that occupational therapists working in the school system can understand their role in helping post concuss students recovery. So I really appreciate your willingness to share your story with me and with others. Yeah, it was good talking to you.

It was great talking with you too. Take care.

I'm thankful that Ivy was able to share that experience with us. Moving right along.

Evidence Review

Emerging evidence highlights the risk that prolonged occupational deprivation poses to the overall health of post-concussed youth and supports a timely return to meaningful activity, provided it remains below the individual’s symptom threshold. We touched on this earlier, and now I’d like to take a closer look at the body of evidence that helped shape this school-based OT framework for supporting post-concussed youth.

Several scholars emphasize the importance of analyzing occupational performance and promoting a good fit between the person, environment, and task. They also underscore the need to incorporate a graded activity that balances rest with the development of environmental or task adaptations—strategies that support recovery while promoting both academic progression and mental well-being. In addition, the literature strongly advocates for the use of top-down, occupation-based approaches that prioritize the exploration of role meaningfulness and competence. These approaches suggest that performance component deficits should only be explored to the extent necessary to clarify the sources of observed functional limitations.

Numerous studies also highlight the critical role of occupational therapy in concussion care within educational settings. These studies consistently support occupation-based interventions that are individualized, holistic, strength-based, context-driven, and collaborative. Several specific approaches have shown promise in supporting recovery for post-concussed youth. These include the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), the Dove Hawk model of allostatic load, the Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) approach, and a multi-tiered systems model.

Let’s examine how these approaches can be integrated into school-based OT service provision for post-concussed youth. A multi-tiered systems model is a three-tiered approach featuring collaborative consultation between occupational therapists and school staff. This model promotes participation in learning for at-risk students, including those recovering from concussions. It incorporates a graded approach to learning that includes universally designed instruction, modification of teaching materials, and individualized support tailored to student needs. Practitioners are encouraged to shift focus from identifying deficits to leveraging a strength-based support model.

The Dove Hawk model of allostatic load for youth with persistent concussion symptoms provides insight into how personal factors can shape behavior profiles that influence recovery. This model emphasizes self-management, the creation of personal boundaries, and the development of realistic expectations to guide a successful return to activity.

Similarly, the CO-OP approach promotes self-management and facilitates re-engagement in meaningful occupations. This approach focuses on collaborative goal setting and active doing rather than restricting activity. It encourages a symptom-guided re-entry into everyday life, which aligns well with concussion recovery principles.

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) has been used to evaluate occupational outcomes in youth receiving client-centered, occupation-based interventions following concussion. It is a valuable tool for measuring recovery in youth who have experienced occupational deprivation due to a prolonged recovery period.

This programming framework begins by implementing a multi-tiered systems model of support, creating a foundation for layered, collaborative intervention tailored to each student's unique needs.

Service Delivery Framework: Using a Multi-Tiered Systems Model of Support

Within this framework, the school-based OT leverages a multidisciplinary team approach, collaborating with educators, administrators, parents, coaches, and health professionals throughout the Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) process. This collaborative structure allows for consistent communication and shared decision-making, ensuring the post-concussed youth receives comprehensive, individualized support.

Let’s look closer at this three-tiered system and how it functions in practice.

Tier I: Concussion Awareness and Prevention

Tier I OT support focuses on concussion awareness and prevention activities designed to reduce the risk of concussion injuries. The interventions provided at this level fall within the occupational therapy practice framework's domain of health management and are considered health-promoting activities that support school-aged youth in maintaining participation in meaningful occupations.

At Tier I, school-based OT support may include a variety of proactive and educational strategies. These can involve faculty “lunch and learn” sessions, in-service presentations that outline the signs and symptoms of concussion, and assessments to ensure proper fit of sports gear. Educational handouts and visual aids are also distributed to students, educators, and parents to increase understanding of concussion risks and symptoms. Additionally, school-wide assemblies may be conducted where the entire student body gathers to learn about concussion signs, symptoms, and strategies for prevention.

Tier II: Student Screening & Multi-Tiered Model of Support

Tier II school-based OT support is initiated for students who are experiencing concussion symptoms that create barriers to participation in educational activities. At this stage, those participation barriers may warrant screening to understand the student's needs better.

The school-based OT observes the post-concussed student within the natural context of their educational routines, offering targeted recommendations that may include embedded classroom strategies. Screenings can occur at any time within the educational environment and may be requested by family members, educators, or medical providers. Throughout the Tier II process, the OT provides collaborative support to the educational team, ensuring that strategies remain aligned with the student's evolving needs.

Supportive Tier II interventions often include visual aids and educational handouts that promote learning through universally designed learning (UDL) strategies. A graded recovery approach encourages student participation in activities that remain below their symptom threshold. UDL strategies at this level may include modifications to instructional materials, adjustments to learning activities, and environmental adaptations supporting the student's recovery capabilities.

This same support framework can be extended to coaches, enabling the post-concussed youth to safely re-engage in play through modified physical activity or participation in alternative team roles throughout their recovery phase.

Tier II: Caregiver & Post-Concussed Youth Education

Tier II school-based OT support also includes caregiver education, recognizing that increasing caregiver knowledge can clarify caregiving roles and positively impact the recovery of post-concussed youth. Support at this level often focuses on developing a shared understanding of the caregiver’s and the youth’s perceptions of recovery while offering practical strategies that can be easily integrated into natural routines.

The OT incorporates visual aids and educational handouts as essential Tier II supports. These tools provide guidance on post-concussion recovery guidelines, nutritional strategies that support brain health, sleep hygiene practices, a graded approach to physical activity, energy conservation techniques, coping and relaxation strategies, tips for social re-engagement and visual supports or classroom adaptations to improve academic performance.

Your handouts include all of the visual aids I’ve just described. Please feel free to use them in your practice as knowledge tools to support post-concussed youth in their recovery and their participation in educationally related occupations.

Tier III: Individualized Evaluation, Intervention, & Outcome Measures

Tier III support is initiated for students who continue to experience lingering post-concussion symptoms beyond the typical four-week recovery window. While Tier II interventions may still offer some benefits, students at this level often require more individualized and intensive support during educational activities to improve occupational performance.

At this stage, the student’s educational team may determine that a referral for a school-based OT evaluation is necessary to identify specific supports that warrant more direct service provision. This model emphasizes the integration of several key tools and approaches, including the Dove Hawk model of allostatic load for youth with persistent concussion symptoms, the AOTA Occupational Profile, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), the Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) approach, and Goal Attainment Scaling. These tools serve as integral components of Tier III programming.

Additional occupation-based assessments and interventions may be incorporated at this level, depending on the student’s needs. As with all levels of support, a multidisciplinary approach is maintained, involving ongoing collaboration with medical and rehabilitation specialists who are supporting the recovery of post-concussed youth.

At Tier III, the school-based OT provides highly individualized interventions to facilitate reintegration into educational activities while remaining below the student’s symptom threshold. These interventions aim to support effective symptom management and enable modified participation in meaningful educational and sporting occupations.

Assessment

Canadian Occupational Performance Model (COPM)

Since the first step to evaluation is assessment, let’s take a closer look at the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM). The COPM is a client-centered outcome measure that guides the school-based OT in facilitating a meaningful discussion with the post-concussed youth to identify occupational barriers that are limiting their participation in daily routines. This conversation allows the student to reflect on environmental demands and role expectations that may interfere with their ability to engage in occupation.

The occupations measured within the COPM fall into three primary categories: self-care, leisure, and productivity. The outcomes of this assessment generate both performance and satisfaction scores for the post-concussed youth in each of these areas.

The school-based OT conducts a semi-structured interview with the student, during which the youth identifies specific occupational barriers and prioritizes the performance areas that are most important to them. This prioritization forms the foundation for developing meaningful, individualized intervention goals.

The COPM is particularly valuable because it tracks changes in youth occupational performance over time. Based on collaboration between the student and the therapist, it can be administered at the beginning of service provision and revisited at any point during the intervention process.

In your handouts, I’ve included a document with sample program questions you may find helpful during your interview with the post-concussed student. Feel free to use that handout as a starting point to guide your questions during the COPM assessment.

Dove-Hawk Model of Allostatic Load for Youth with Persistent Concussion Symptoms

The assessment also includes the use of the Dove Hawk model of allostatic load for youth with persistent concussion symptoms. Let’s take a moment to review this model in more detail.

The Dove Hawk model explores how personal factors can shape behavior profiles that influence the course of recovery. It identifies two primary behavioral profiles: the passive “Dove” and the active “Hawk.”

Post-concussed youth who are fearful or hesitant to resume pre-injury occupations—despite it being safe to do so—may withdraw or avoid activity and often appear anxious. These individuals are described as having characteristics of a passive Dove profile.

In contrast, youth who hold high expectations for themselves, push too hard to return to pre-injury occupations, ignore symptoms, exhibit irritability or anger, and experience excessive fatigue are described as fitting an active Hawk profile.

Dove Hawk profiling supports the occupational therapist in designing individualized interventions that focus on self-management, establishing personal boundaries, and developing realistic expectations. These strategies guide a safe and effective return to activity tailored to the youth’s unique behavioral response to recovery.

Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) Approach

You can begin to understand which profile your post-concussed student may be functioning under—whether Dove or Hawk—during the administration of the COPM and while observing their performance using the CO-OP approach. Since we’re now discussing the CO-OP approach, I want to introduce this intervention strategy in more detail. Please pay close attention to this slide and mark it with a star so you can review it later.

When using the CO-OP approach, the school-based OTP facilitates re-engagement in occupation by supporting post-concussed youth as they identify a goal, develop a plan to work toward it, carry it out, and then reflect on how it works. This intervention follows the “Goal–Plan–Do–Check” strategy.

For example, the post-concussed youth begins by naming a specific goal they want to achieve. From there, the school-based OTP uses guided discovery to initiate a collaborative discussion, helping the youth explore and shape a plan for reaching that goal. While the OT may offer education on options or strategies that could support performance, they never directly tell the youth what to do. Instead, the therapist uses probing questions to promote problem-solving and ownership.

These questions might include, “How do you think this strategy will help you?” or “When will you use this strategy?” Students are encouraged to develop their solutions and select meaningful and relevant strategies.

Once a plan is in place, the youth enters the “Do” phase of the approach—carrying out their plan. The therapist may observe the student in action during the session, or the student may implement the plan independently and return to discuss the outcome at the next OT session.

This brings us to the “Check” phase, where the youth and the OTP review strategies. The therapist provides constructive feedback, and together, they determine whether the plan needs adjustment. This cycle repeats until the student feels they have successfully met their goal.

Outcome Measures

COPM

Notably, this intervention approach can also be used to measure occupational outcomes through the youth process of performing meaningful occupation-based interventions and supplement outcome measures identified through the administration of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure described earlier. The COPM can be administered throughout the intervention to measure post-concussed youth progress toward meaningful goals.

Goal Attainment Scaling

Another outcome measure used in this framework is Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS). GAS is especially valuable because it promotes collaborative goal setting, which is instrumental in developing goals that are personally meaningful and valued by the student. This process allows for measurable tracking of changes in occupation-based outcomes over time.

With GAS, the post-concussed youth is actively involved in identifying their own goals and anticipated outcomes. These outcomes are tailored to reflect both the student's current level of performance and their expected level of achievement. Progress is then rated throughout the course of the intervention, providing a clear picture of how the student is advancing toward their goals.

If you’re like me, you might find that one potential drawback of Goal Attainment Scaling is the level of detail and calculation required to formulate scorable goals. While the process can be more rigorous on the front end, the personalized and data-driven insight it provides into the youth’s recovery makes it a highly effective outcome measure within this framework.

GAS-Light Approach

For this reason, this framework emphasizes the GAS Light approach. This modified version of Goal Attainment Scaling removes the need for rigorous calculations while preserving the process's core benefits—namely, the development of valuable, occupation-based goals that reflect meaningful change in the post-concussed youth’s baseline performance.

GAS Light allows the student and therapist to collaboratively identify clear, functional goals and track observable progress over time without the complexity of weighted scoring or statistical analysis. It offers a user-friendly way to maintain client-centered focus and ensure that interventions align with the youth’s priorities and evolving capabilities.

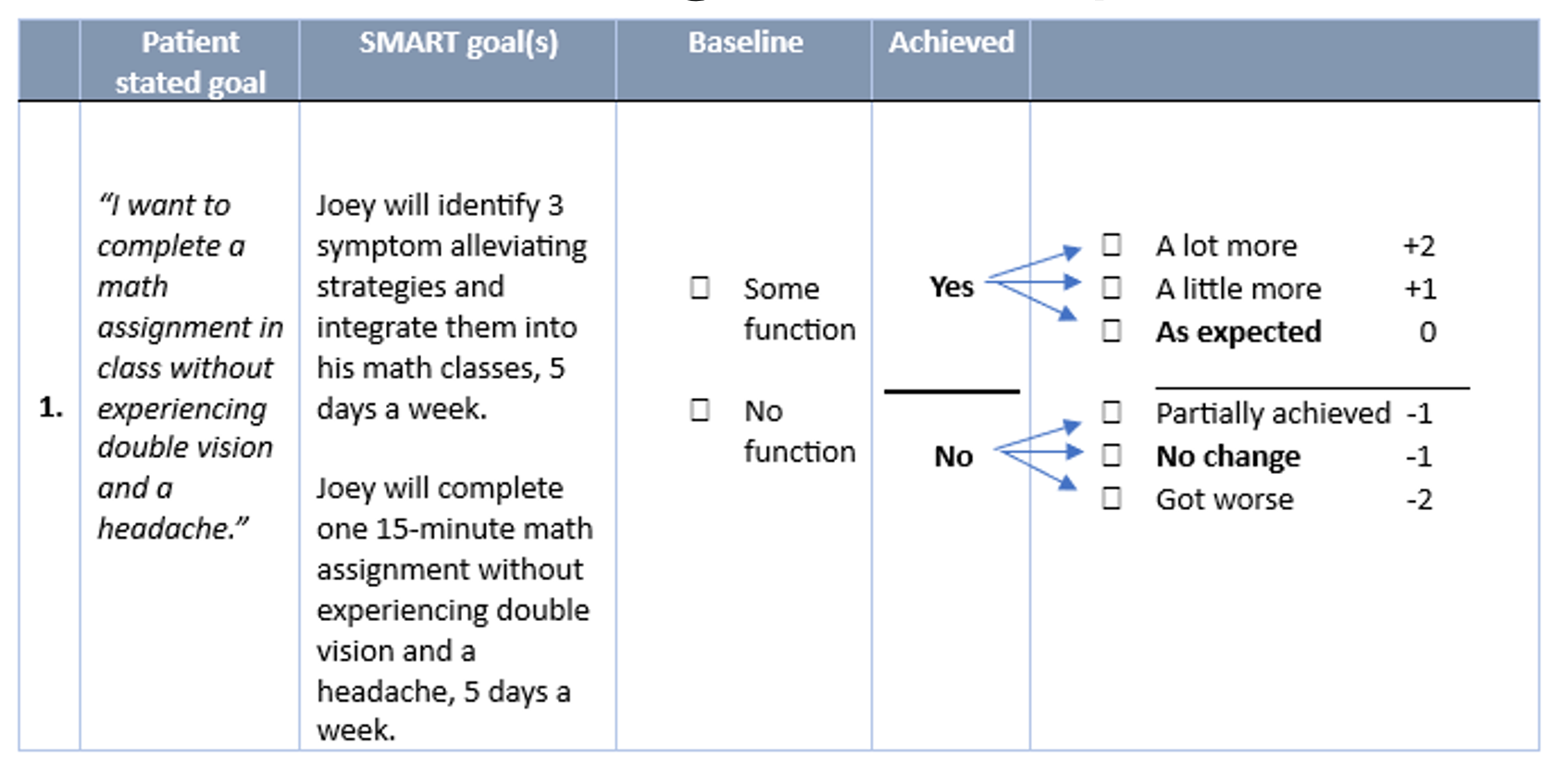

Let’s peek at what this simplified approach looks like in practice in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Example of GAS-Light Approach (Click here to enlarge the image.).

In this visual, the post-concussed youth states their goal. The therapist and post-concussed youth collaborate to develop a measurable goal. Using the SMART format, baseline performance is captured during each scheduled session. The post-concussed youth and therapists can review progress toward the goal and determine whether the goal is achieved through a rating that measures change as a lot more, a little more, as expected, partially or no change at all, or even performance became worse. This goal can be adjusted at any time. I wanted to share this table with you as I wrap up this section.

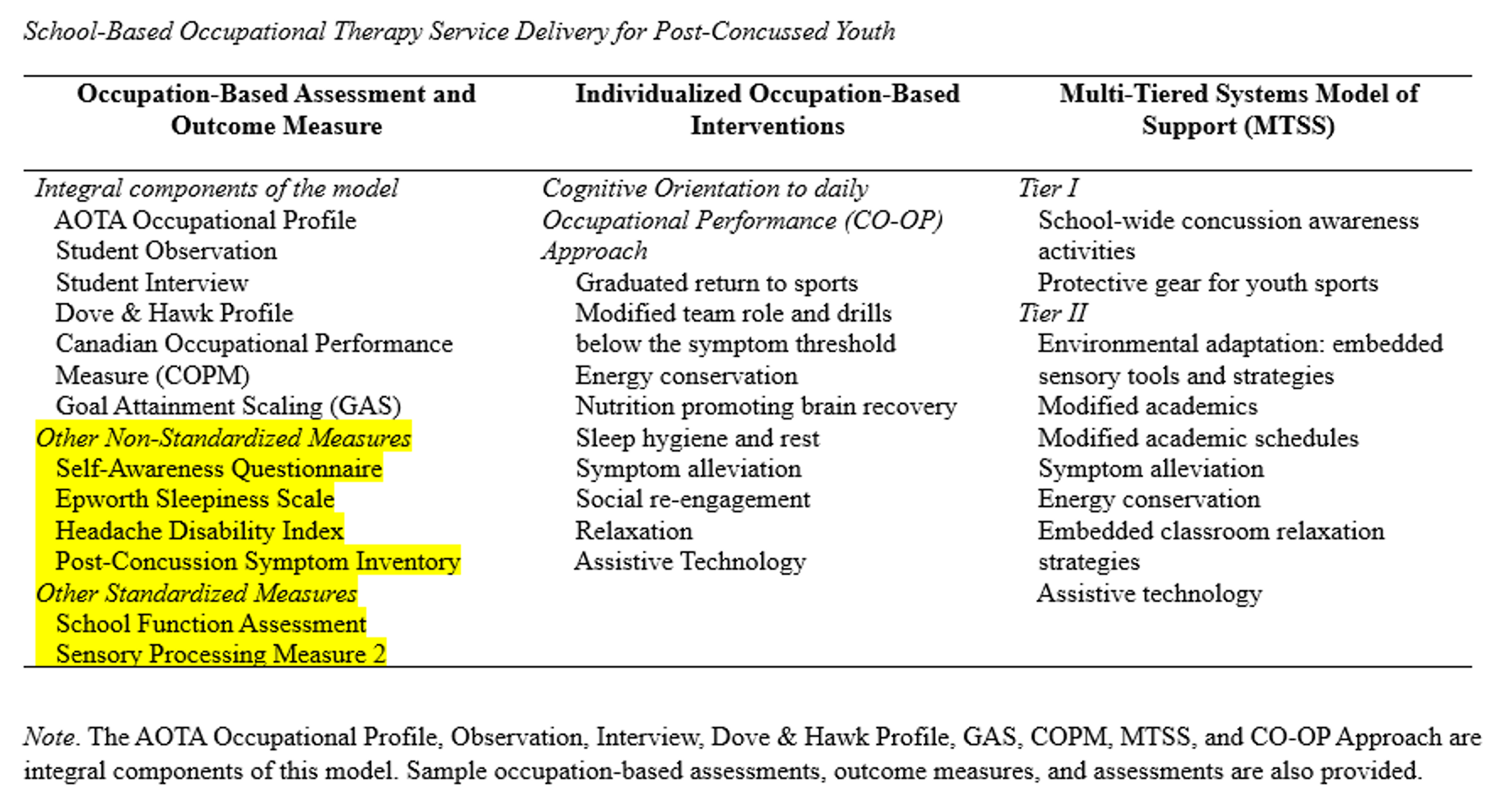

It provides an overview of the occupation-based assessments and outcome measures used within this School-Based OT Programming Framework for Post-Concussed Youth so you can reference it later. I want to draw your attention to the yellow highlighted section of this table in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Overview of the occupation-based assessments and outcome measures (Click here to enlarge the image). Unpublished Capstone. Developed by Morgan & Skuthan (2024).

Though the school-based OT practitioner can incorporate other standardized and non-standardized assessments during programming, this framework emphasizes an occupation-based and strengths-based approach. It prioritizes using the assessment and outcome measures highlighted in the far-left column of the table.

I also want to draw your attention to the potential overlap between Tier II and Tier III interventions, as reflected in the middle and far-right columns of the table. This overlap is appropriate and may be necessary to provide the individualized care your students need. Flexibility within the framework allows practitioners to tailor support in a way that truly meets each student where they are in their recovery journey.

Case Study: Robbie (Cont.)

So, let’s circle back to Robbie’s injury and explore how the school-based OT practitioner addressed his needs. I want to focus on the highlighted section of this slide. By midday, Robbie was experiencing a headache, sensitivity to sounds, difficulty concentrating, fidgety and restless behavior, and fatigue. These signs suggest that he likely reached his threshold for cognitive activity during his morning academic schedule.

It’s also important to point out that, in this case study, Robbie strongly desired to return to play. However, his coach had concerns, and his parents were uncertain about how to best support him in managing his symptoms while continuing to learn.

Robbie’s injury occurred within the typical four-week recovery window, so the school-based OT recommended Tier II academic supports rather than immediately moving to an individualized evaluation. These supports included a variety of symptom-guided strategies: earplugs were provided to reduce auditory sensitivity, a stress ball was offered to support self-regulation, and preferential seating was recommended—likely a corner seat away from high-traffic areas such as the door or teacher’s desk.

In addition, oral answers were accepted for some assignments to reduce the cognitive load of writing, and voice-to-text technology was introduced to further support written expression. Robbie was also allowed to rest for 15 minutes between classes in the nurse’s office, where he used a cold compress to help manage his headache. Homework was reduced to help him conserve cognitive energy.

These Tier II academic supports were closely monitored and tailored to help Robbie alleviate symptoms and participate in his education below the symptom threshold. They remained in place until his symptoms resolved, ensuring a safe and supportive recovery within the school setting.

Tier II Support

The school-based OT also played a key role in supporting Robbie’s return to basketball through Tier II interventions throughout his recovery. Robbie’s coach involved him by asking him to review game film for as long as he could tolerate, with the option to email or call in his analysis. This made Robbie feel like he was still part of the team, even while limiting physical exertion.

As his recovery progressed, Robbie was gradually reintroduced to physical activity. He began with passing drills and participating in non-contact team activities. Eventually, he was able to return to play once fully he received medical clearance from his physician.

In addition to supporting Robbie’s return to academics and sports, the school-based OT provided educational handouts to Robbie and his parents. These handouts focused on sleep hygiene and brain health, including recommendations such as following a diet rich in omega-3s, limiting caffeine intake, and drinking plenty of water throughout the day to stay hydrated.

Many of the recommendations shown on this slide are included in your handouts, so feel free to use them as practical tools when working with post-concussed families.

Case Study: Caroline

Now, let’s review the case study of Caroline, who required more intensive Tier III support, including an individualized school-based OT evaluation. A similar case study is included in your handouts for later review, but for now, I’ll walk you through the highlights.

Caroline is 14 years old and sustained a concussion during a soccer game five weeks ago. She briefly lost consciousness after colliding with a teammate. Initially, she received Tier II academic supports recommended by the school-based OT, which included modified assignments and environmental adaptations—likely similar to those provided to Robbie. However, Caroline also attended school on a shortened day schedule.

While these supports were beneficial, she continued to experience performance difficulties, and her lingering post-concussion symptoms began to impact her behavior. Parents and teachers noted that Caroline’s typically cheerful personality had shifted—she had become irritable, quiet, and withdrawn, and her academic performance was declining.

Since her symptoms extended beyond the typical four-week recovery window and behavioral changes were evident, the school team recommended a school-based OT evaluation. This slide highlights the use of the Return to Doing visual aid, which helped identify where Caroline was functioning below her symptom threshold at week five.

During the evaluation process, the school-based OT obtained consent to communicate with Caroline’s medical and rehabilitation providers. The OT used the Occupational Profile to gather meaningful information about Caroline’s performance barriers, values, priorities, and concerns. In addition to the insights shared by her healthcare team, the OT observed Caroline in the classroom to better understand the performance and environmental factors either supporting or limiting her engagement.

A range of standardized and non-standardized, occupation-based assessments were administered, including the COPM, the School Function Assessment, activity simulation tasks, and symptom inventories. The COPM revealed several areas of occupational imbalance across self-care, leisure, and productivity. Caroline reported difficulties with rest, fatigue, low energy, headaches, sound sensitivity, dizziness, feeling socially isolated, and academic challenges. Her learning barriers were particularly evident in reading, writing, and memory.

This slide also demonstrates the use of Goal Attainment Scaling Light to develop Caroline’s school-based goals. You’ll be able to review her full list of goals in your handouts later, but let’s take a moment to explore Goal #2. Caroline expressed a desire not to feel isolated from her friends due to her physical symptoms. A SMART goal was developed: Caroline would review homework with a friend and use FaceTime with her coach to review plays, tolerating 15 minutes of conversation five days a week. At baseline, she could manage some interaction. By the end of one week, she made partial progress toward this goal, reporting that she could engage in 10 minutes of FaceTime-based homework with a friend.

The next slide provides an example of an academic-centered goal using assistive technology to support Caroline’s reading and writing challenges. As with the earlier example, she could visualize her progress through the highlighted areas in her plan. During her OT sessions, she worked with the therapist to review and adjust her strategies using the CO-OP approach.

This slide outlines how the CO-OP method was applied to her goal areas using the “Goal–Plan–Do–Check” strategy. Caroline identified a goal, developed a plan with support, carried out the plan, and then evaluated its effectiveness. The school-based OT observed her performance, used guided discussion to help Caroline identify gaps, and implemented occupation-based interventions to bridge those gaps.

In Caroline’s case, the school-based OT introduced a variety of assistive technology tools to support her academic participation. These included blue light glasses, screen dimming, voice-to-text dictation software, KAMI, and Snap&Read. Caroline learned how to use these tools during her intervention sessions and, with guidance, identified which classes would benefit most from their use.

The OT and Caroline then collaborated with her teachers to integrate these tools into her school assignments. Performance outcomes were reviewed during subsequent sessions. Throughout her recovery, Goal Attainment Scaling Light continued to be used to measure progress, while the CO-OP approach helped refine strategies aimed at achieving her COPM goals.

Summary

In summary, this framework emphasizes the use of occupation-based assessment and intervention within a Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) model. It highlights the school-based OT’s valuable contribution to multidisciplinary care throughout the recovery process for post-concussed youth.

In closing, I’d like everyone to take away a few key points from this framework. The first step in concussion care for the school-based OT is to promote health management through Tier I school-wide concussion awareness activities. This should be followed by a continuum of care that includes ongoing communication between educational, athletic, medical, and rehabilitation teams.

Refer to the diagram and the knowledge tools shared during this webinar when providing Tier II and Tier III interventions. Use them when meeting with school administrators, educators, parents, and post-concussed youth to help explain the role and scope of school-based OT in concussion recovery within the educational setting.

Finally, the last phase of school-based OT programming for post-concussed youth should include the use of outcome measures to identify and address implementation barriers, refine programming, and ensure that each student receives the individualized support they need.

Questions and Answers

Are there any accommodations being put in place in classrooms for students who suffer concussions during sports activities?

Yes, accommodations are typically offered as Tier II supports in the schools I work with. I collaborate closely with the school nurse to monitor physical symptoms while teachers observe and track academic symptoms. These symptoms are reviewed weekly to determine the need for ongoing support. Although I haven’t yet been actively providing accommodations to coaches, I’m currently advocating for my role as an occupational therapist in concussion recovery and have started engaging with administrators about it.

How can we educate doctors about the effects of medications like Adderall on students recovering from a concussion?

That’s a great question. One suggestion is to create a handout or visual aid and drop it off at local physicians' offices. Another idea is to schedule a “lunch and learn” session with area physicians to provide them with more detailed information. These efforts can help bridge the gap in understanding how certain medications may affect concussion recovery.

Can schools provide temporary accommodations for students with a concussion, even if they don’t have an IEP?

Yes, temporary accommodations like extended time to complete assignments and tests can be provided through Tier 2 supports. Most students with a concussion do not qualify for an IEP, but under a Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS), schools can implement these kinds of temporary strategies to support recovery without requiring special education services.

It was a pleasure sharing this information with you all. Thank you so much for joining me. Have a great day.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Morgan, J. (2025). School based occupational therapy for post concussed youth an occupation based framework. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5791. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com