Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Sensory Health: The Missing Piece in the Wellness Conversation, presented by Catherine M. Cavaliere, PhD, OTR.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the concept of sensory health.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the role of sensory health in well-being.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the role of sensory health in community health and participation.

Introduction

Thank you so much for joining me today. I am excited to be here and talk about sensory health. As occupational therapists, this is not new to us. We understand the concept of sensory processing and integration, and in fact, we can say that we are experts in sensory processing and integration.

Today, we will reframe the concepts of sensory processing and integration and move away from the clinical and toward the area of health and wellness. This shift fits into the AOTA vision and is good for our profession moving forward. It is essential to bring forward our specialized knowledge in sensory processing and integration to support health and wellness.

Dr. Ayres is a pioneer in terms of sensory integration and processing theory. Her work has left a tremendous impact on our profession as she was the first one to talk about the role of sensory integration in learning and behavior.

- "The experience of being human is embedded in the sensory event of everyday life." (Dunn, 2001)

However, Winnie Dunn was the first to speak about the integral role of sensory processing in our lives. Life is rich with sensation. Every experience we have is embedded with sensation, so it is central to the human experience. This makes sensory processing especially important to wellness and well-being.

Impact of Sensory Processing

- "The way in which our brains and bodies process and integrate sensory information influences how we experience the world and ourselves within the world."

- Sensory processing impact:

- Motor

- Praxis

- Self-image

- Social-emotional

- Mental health

- Physical health

- Participation

- Resilience

We understand ourselves and the world through our sensory experiences, body senses, and our external senses. We bring concepts of sensory processing and integration to communities and populations that we would not have otherwise reached if we approached it from a purely clinical point of view. Some people do not come to us unless they have a challenge or a problem with their sensory modulation. Bringing an understanding of the essential human experience and its impact on our interactions and engagement with the world can provide a deeper understanding of health and wellness and our experience within the world. Our sensory processing patterns impact human action from reflexes to conscious decision-making. Everything that we do is grounded in sensation, and each of us uniquely processes sensory information.

Our sensory processing patterns have a dramatic influence on our experience within the world. The way we process sensation provides us with affordances for health and participation, impacts motor planning (praxis) and implementation, and higher-order skills (executive function) like planning and organization. Sensory processing affects not only motor skills but also cognitive and other perceptual skills. Engaging in the world allows us to develop self-efficacy and self-esteem. And, this all gives meaning to the things that we do.

These concepts are fundamental in understanding that we can be agents of change within the world. This understanding plays a large part in our mental health and our participation.

Sensory Health

Let's take a further look at sensory health using examples of hand skills (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Examples of people using their hands.

Hand skills begin reflexively. You touch an infant's palm, and the hand grasps the finger. It is a reflexive sensory-motor experience that results in engagement. As the infant develops and their sensory-motor skills become more voluntary and volitional, the infant begins to understand that they have control. They can reach out and grasp a toy. This experience is grounded in sensation. Take, for example, a baseball player who catches a baseball. Perhaps the feeling of catching a ball causes a child to join a baseball team. He then makes friends on that team and begins to identify himself with that team and as a baseball player. The child develops a sense of self, develops relationships, and increases their self-esteem, integral to health and well-being. Engagement with the objects and the people in our environment supports the development of oneself and belonging in the world, directly impacting our sense of well-being.

Sensations also drive our choices and our habits in life. We gravitate towards people and activities that are meaningful, feel good, and that satisfies a need. Why do some of us love classical music and others love heavy metal? Why do some of us love a yoga class while others love kickboxing? The answer is because of how it feels. And, we know that feelings come from sensing and identifying internal cues that connect to an emotion.

Senses

- Vision

- Audition

- Taste

- Smell

- Touch

- Vestibular

- Proprioceptive

- Interoception

- *Neuroception

As occupational therapists, we are well-versed in sensory processing, integration, and the different senses. I want to highlight both interoception and neuroception.

Interoception

- Information that we get from the internal organs

- Body cues

- Feeling

- Drives us to act

(Mahler, 2017)

Interoception is the information that we get from our internal organs, and it gives us cues about our bodily state. Understanding these cues and being able to process and integrate them motivates us to act. As Kelly Mahler states, it is the basis for self-regulated behavior. An elementary example is your stomach growling and having a headache. This means you are hungry. You are connecting bodily cues to a feeling and emotion. You then act to regulate yourself by getting something to eat. This is purposeful, regulated, and directed behavior. Interoception is being able to understand ourselves and being responsive to our bodies.

Interoception also allows us to use these feelings as a reference point to connect with others and develop empathy. For instance, you know what hunger feels like; therefore, if somebody else tells you they are hungry, you can empathize with them. This creates perspective-taking allowing us to attune to other people, develop relationships, and ultimately to co-regulate and self-regulate.

Neuroception

- The ability to sense safety and danger

- Informed through our senses

- Environmental cues safety and danger- shrill sounds, the smell of smoke, seeing a violent act

- Safety cues – social cues

- Unconscious/ conscious

- Stress- faulty neuroception

- Sensory Processing differences

(Porges, 2011)

For those of you who are polyvagal geeks like me, you probably have heard of neuroception. Neuroception is one of the pillars of the Polyvagal Theory, designed by Stephen Porges. Neuroception is the ability to sense safety and danger via our senses. For instance, examples are the shrill sound of a fire siren, the smell of smoke, or seeing a violent car crash. These experiences cue us to danger.

Safety cues, in addition to the environmental cues, can also come from other people. They are social cues that inform us that we are having a safe interaction. The prosody of voice is an example. Think about a mom soothing her baby. She talks very rhythmically, softly, and calmly.

In contrast, think about a teacher scolding a student. She talks sternly and loudly. These are two different experiences that cue us about safety.

Head-turning, orienting, and eye gaze tell a person that someone is interested or is there for them. We can also get cues from facial expressions like a soft versus a tight stern face. These are all examples of social cues that allow us to experience safety from others, co-regulate to form attachments, and eventually self-regulate.

However, chronic and prolonged stress, trauma, or whatever it may be can result in faulty neuroception. Our nervous system is in a state of danger and cannot pick up on these safety and social cues. As such, this perpetuates the dangerous state within our nervous system and our autonomic nervous system in particular.

I also think about what sensory processing differences do to a body due to a state of stress. Research tells us that people with sensory processing differences are more prone to experiencing high levels of stress. What does this do to a person's sense of safety within their body and environment?

Self-Regulation

- Self-regulation is flexibility in responding to the environment, task, and relational demands

- Physiologic

- Emotional

- Behavioral

- Sensory

- Cognitive

- *Flexibility in responses

The following important concept for sensory health is self-regulation. As OTs, we talk a lot about self-regulation, but it has not been perfectly defined yet. I see self-regulation as flexibility in responding to the environment, task, and relational demands. It involves physiologic, emotional, behavioral, sensory, and cognitive flexibility. All of these areas interact to allow an individual to have a dynamic state of self-regulation. The key to self-regulation is flexibility in response.

One's sensory needs, preferences, differences drive action towards self-regulation. Research states that self-regulation in children, in particular, supports better academic achievement throughout childhood, adolescence, and even into adulthood. It supports feelings of higher self-worth, increased ability to cope with stress, less substance abuse, and less law-breaking, even amongst at-risk youth. Self-regulation plays a crucial role in well-being and wellness overall.

Again, persons with autism, who sometimes tend to be rigid in their thinking and behaviors, may have less physiologic flexibility. We know their emotional and behavioral flexibility because we can see and measure that. We also know that persons with autism demonstrate some sensory modulation challenges. Thus, I looked at physiologic flexibility and vagal tone (a measure of heart rate variability) in children with autism and typically developing children. I found that when I compared these two groups, children with autism demonstrated less physiologic flexibility at baseline and in response to sensation. This needs more research.

I also mentioned interoception and neuroception as they play a considerable role in self-regulation and our ability to flexibly respond to stimuli in the environment.

Co-Regulation and Self-Regulation

- Interoception

- Attunement

- Attachment

- Empathy

- Perspective-taking

- Neuroception

- Access safe and social cues

- Use those cues for regulating

- Give safe and social cues

We are constantly processing interoceptive, neuroceptive, body sense, and external sensory information through this dynamic state of self-regulation and integrating those efficiently and effectively. Self-regulation allows us to feel safe, confident, and in control. Ultimately, it gives us a sense of well-being as agents of change in our environment.

- Sensory health is the bridge that connects the concepts of sensory processing and integration, self-regulation, and well-being. Therefore, we can say that well-being is truly grounded in sensory processing and integration.

- Foundation for our interactions within the world

- Mastery and development of self

- Supports relationships

- Mindful awareness of our sensory processing styles, needs, and preferences and responding accordingly can allow us to achieve a more complete sense of well being = self-regulation

Sensory processing and integration provide the foundation for interactions within the world. They allow for mastery of skill and development of self and support relationships. Mindful awareness of our sensory processing styles, needs, and preferences will enable us to achieve a more complete sense of well-being. This is what I hope you will get out of today's conversation and is what we can bring this information to people, and we can help them achieve that more profound sense of self-actualization, well-being, and wellness.

Well-being

There are many different definitions of well-being. Seligman in 2011 described it as a state of flourishing.

- 5 elements:

- Positive emotions

- Engagement

- Positive relationships

- Meaning

Accomplishment

Sensory Health

He also identifies five elements to well-being, positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. As OTs, it is clear to see how sensory processing and integration can impact each area.

As we talked about earlier, positive emotions are associated with interoception. Interoception connects to our bodily senses and allows us to feel positive emotions more intensely. We also engage with the world through sensory-motor experiences. Participation is an essential piece of sensory processing and integration that supports positive relationships. We also talked about placing meaning to sensory experiences over time and how the affordances in terms of health and participation through our sensory processing and integration abilities allow us to develop meaning with our experiences. Accomplishment is developing a sense of control, being an agent of change, and obtaining a sense of mastery over our environment through our sensory processing and integration.

Sensory Processing and Well-being Related Concepts

- Mental Health

- Physical Health

- Quality of Life

There is also information on sensory processing in mental health, physical health, quality of life, and resilience. I will briefly go into these concepts to demonstrate the profound role of sensory processing and integration.

Sensory Processing and Mental Health

- Sensory differences at risk:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- High-stress levels

- Social discomfort

- Low self-esteem

- Negative affect

- Difficulty developing and maintaining relationships

- Impacts of trauma

- Interoception

- Mood disorders

- Eating disorders

- Addiction

(Engel Yeger & Dunn, 2011; Harrison et al., 2019; Reynolds et al., 2012; Aron & Aron, 1997; Ben Avi et al., 2012; Paulus & Stein, 2010; Klabunde et al., 2013; Paulus et al., 2013; DiLernia et al., 2016)

People have sensory differences, and research shows correlations with these and anxiety, depression, high-stress levels, social discomfort, low self-esteem, negative affect, and difficulty developing relationships. They feel more deeply the impacts of trauma, specifically in terms of interoception. And, we know the interoception has been correlated with mood disorders, eating disorders, and addictions.

Sensory Processing and Physical Health

- Higher levels of stress – at risk for chronic health conditions

- Correlations type 1 diabetes in children

- Regional complex pain syndrome

- Fibromyalgia

- Migraines

- Less physical activity- at risk for chronic health conditions

(Bar-Shalita et al., 2018; Goldberg et al., 2018; Hebert, 2018; Hertzog et al., 2019; Kimball et al., 2012; Kosiecz et al., 2019; Seo & Park, 2018)

Regarding physical health, we know that persons with specific sensory processing differences have higher stress levels and are therefore at risk for chronic health conditions. Research also shows correlations between people's sensory differences and type 1 diabetes (in children) and pain syndromes, like regional complex pain syndrome and fibromyalgia.

Sensory Processing and Quality of Life

- Active sensory regulation:

- Increased resilience

- Adaptability

- Sense of control

- Self-esteem

- Self-confidence

- Quality of life

- More physically active

- Lower BMI

(Dean et al., 2018; Engle Yeger & Rosenblum, 2017; Meredith et al., 2015; Iacoviello & Charney, 2014)

Active sensory regulation behaviors are the key to promoting positive mental and physical health and mitigating sensory processing differences' potential adverse health effects. Research shows that people who use active self-regulation, even people with sensory processing differences, have increased adaptability, sense of control, self-esteem, self-confidence, quality of life, and better physical health outcomes.

When using active sensory regulation behaviors, we can also mitigate some of these issues. This is important for us as professionals. Action towards a regulated state shows integration and a connection to one's body and environment, including the people in their environment. The melding of these factors and the capacities for building relationships and self-regulation allow one to experience safety in the world and experience interactions to support positive mental health. Ultimately, sensory health is a pillar of wellness. And, it is the pillar that is not talked about as much as it should be. This is surprising because we talk about these different health poles, including sensory, mental, physical, financial, and social areas. Sensory health allows for this more profound sense of self and a deeper experience of self-actualization. It is something that occupational therapists can bring to the table.

Public Health Approach to Sensory Health

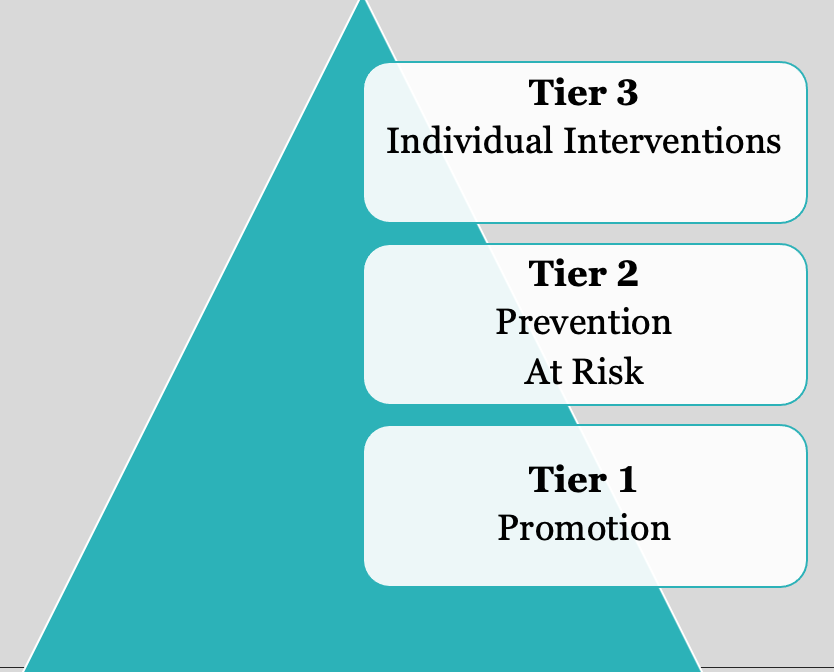

We can take a public health approach to sensory health, as noted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Three tiers of a public health approach.

A public health approach shows how you can provide health and wellness interventions with different communities of people. For instance, Tier 1 promotes health for all people, not excluding anybody, at the community health level. Then, there is the prevention of ill health at Tier 2. This is working with at-risk groups prone to particular health challenges, such as sensory processing challenges. Lastly, Tier 3 is individual interventions for those that need help to participate in life.

Tier One

- Mind-body connection – yoga; mediation; mindfulness- mindful minutes; interoceptive building

- Leisure exploration

- Lifestyle design

- Physical activity

- Fostering connections to others

- Develop social-emotional capacities for relationship building

- Sensory health literacy

Tier 1 is health promotion through a sensory health lens, and it involves things such as yoga, meditation, and mindfulness. These interventions help with interoceptive building, strengthening a person's ability to form and maintain relationships, gain control, and optimize wellness.

We also want to promote health by helping them to find activities that they enjoy and are driven to do. We can do this by using an informed lens of understanding an individual's sensory processing needs, preferences, patterns, and differences.

We can look at their lifestyles and workspaces. Who do they choose to spend their time with and why. All of this is part of lifestyle design. It uses a mindful approach to help the person discover what makes them happy and allows them to flourish and connect with others.

Sensory health literacy educates people on what sensory health is and why it is vital to wellness.

Tier Two

- Trauma

- Supporting new mothers

- Addiction prevention - adolescents

- Incarceration system

- Neurodiverse populations

- Mental health challenges

- Colleges/university students

- Transitions

- Family counseling

At the second tier, these are people or groups at risk for sensory processing differences, impacting their participation, occupations, and well-being. We know that persons with trauma are prone to sensory modulation challenges and dissociation. We want to support one's connection to their body and support their positive relationships and co-regulation.

It is also important to support new mothers who have increased stress levels and need help identifying how to self-regulate to co-regulate with their children.

People with certain addictions are more at risk of having sensory processing and integration challenges. We can work on prevention with adolescents on addiction prevention and help them to understand their own sensory processing needs and preferences. We can work on leisure exploration or other ways to feed their needs so that they do not go down the road of drugs and alcohol.

We also know that people in the incarceration system have a higher incidence of sensory processing differences. We can help educate them about their sensory health and help them identify lifestyle and leisure choices that might help them rehabilitate.

Neurodiverse populations (autism, ADHD) have more sensory processing challenges. Additionally, research shows that people with mental health challenges have sensory differences that are pretty prominent as compared to the typically developing population. We need to support these populations to achieve sensory health.

- Examples

- Parent education in infant/early childhood sensory-based play techniques to support sensorimotor development

- Sensory supportive environments for diverse learners in schools such as the comfortable cafeteria program (Bazyk et al. 2018) and sensory-friendly classrooms spaces

- Sensory Modulation Program (Champagne, 2011)

- Sensory health literacy programs to help children/youth identify their own unique sensory processing styles and ways to support that in multiple environments

- Programs such as the Zones of Regulation (Kuypers, 2011) to promote self-regulation and social-emotional awareness

- Interoceptive curriculum (Mahler, 2019)

There are so many more at-risk populations, but these are a couple of examples that I thought would be interesting to mention. These are things I think we are doing already, but it is just a matter of reframing some of these using a wellness perspective instead of a clinical perspective. There are plenty of us that educate parents on childhood sensory-based play techniques.

The Comfortable Cafeteria Program is a supportive sensory program. It is a program that supports learners with diverse sensory processing abilities to help them to enjoy a cafeteria experience. It is inclusive of all people.

The Sensory Modulation Program by Tina Champagne is a beautiful program that provides a deeper look at a person's sensory processing preferences and needs and then identifies strategies to help the individual to stay regulated within their environment.

The Zones of Regulation is also a great program that works on self-regulation and emotional regulation by adding a social-emotional component.

The Interoceptive Curriculum by Kelly Mahler is another excellent program. Again, Kelly Mahler is somebody who has done a lot of work with interoception. She wrote a curriculum specifically for people with interoceptive awareness challenges. However, interoception can take mindfulness to the next level for at-risk people and people who want to achieve a greater sense of wellness and well-being.

Tier Three

Tier 3 is working with individuals and families. Rather than fixing something wrong, we can reframe, understand, respond, and support people and their families with sensory differences. The outcomes of optimal sensory health are self-discovery and understanding yourself better, what drives you, your behaviors, your habits, and choices, and other factors that play into that.

Optimal Outcomes

- Self-discovery

- Supporting positive mental health and well being

- Supporting physical health and well being

- Supporting positive relationships

- Supporting self-fulfillment

- Promoting resilience

We want to support positive mental health and well-being, including self-regulation and co-regulation, optimal outcomes. Finding a place of fulfillment can only come from a deep, complete understanding of your sensory self. Again, we know that people with active self-regulation strategies can achieve a sense of safety in their environment and respond to their needs are more resilient in life.

Summary

Occupational therapists can be leaders when it comes to sensory health. We can bring all our knowledge on sensory processing and integration and how it influences everything we do into the wellness conversation. We can make sensory health a more prominent of the conversation to bring the mindful movement to the next level.

You can also reach out to me if you have any questions about any of the research that I talked about. I hope that some of you will take this call to action to bring sensory health more into the mainstream because it can make a change for the greater and fits directly into AOTA's 2025 vision for our profession as we move into the health and wellness realm.

Questions and Answers

Do you find that people do not know what sensory processing is?

Yes, people do not understand the depth of sensory integration and processing. They may use essential oils at night and think this is processing sensation, but they are missing so much of what sensory health means. They also miss how occupational therapists work with clients on more sensory integration and processing than "hear, smell, or touch." They also do not look at how sensory processing shapes our behaviors and influences our habits.

How did you first get interested in doing this kind of work?

I had a practice for many years where I used more of a traditional sensory integration approach. We served mainly children and adolescents with sensory processing challenges and those that did not have a diagnosis, but their caregivers felt something was wrong. We helped children that were gifted and had eating disorders. Through education, what became evident to me is how necessary sensory processing is to our experience and how it can shape behaviors and change family dynamics. It understands the child and their behavior through a sensory processing lens and parent behaviors. A parent has to be regulated to be attuned to their child's regulation and sensory processing needs. As I began doing more talks and hosting more groups for parents, I realized that working with parents was extremely important. We were not doing enough of it as we were constantly in the clinic working with the kids. The other piece was trying to understand the connections between the polyvagal theory and sensory processing.

I loved how you said that when a mother talks to their child, they use a rhythmic cadence, and then a teacher may have a louder, choppier voice.

I think we can all understand that in our daily lives when we are stressed, we get loud. Again, this is grounded in sensation is our ability to feel safe.

Is ABA as influential in the education of autistic children? And, have you seen behaviorists borrowing from OT programs?

I have not seen behaviorists borrowing from OT programs. Still, I think more and more that behaviorists are beginning to see how sensory processing and integration strategies can support positive behavior.

What recommendations do you have for parents of a young child with behavioral anxiety tendencies who often shut down during tasks and use negative self-talk?

I do not know what the family dynamic is like or their sensory processing styles or preferences. One of the first things I would do with the parents is support attunement and connection with the child. Once there is a connection, we can pick up on the safety and social cues to help bring their anxiety down. If the child is in a constant state of danger, it is hard for them to relax.

Are school psychologists open to working with OTs on this subject? I find school psychologists work on self-regulation, and OTs are given the handwriting and fine motor in IEPs. Any tips on bringing these psychologists and OTs into a stronger working relationship?

You are right. I have seen in my experience that psychologists often talk about cognitive regulation and not necessarily sensory regulation. This is where OTs have a foot in the door. Sensory regulation and physiologic regulation through sensory regulation strategies are something that OTs can support. As we move more into the wellness realm, I think people are beginning to understand the connection between sensation and self-regulated behavior. This is where I would make my case when working with a psychologist. When looking at self-regulation, you can bring your unique perspective as an occupational therapist through a sensory health lens.

How do you recommend integrating this into treatment with adults in a way that will allow reimbursement from insurance companies?

This is tricky and depends on the adults and their diagnoses. For instance, if you are working with an adult with mental health issues, you can work on coping strategies, typically covered by insurance. Part of a coping strategy could be identifying sensory health strategies, interoceptive work, and neuroception and co-regulation.

Can you tell us more about your work with discovering the heart muscle not being as flexible in response to cues from relational and environmental?

In my research, I looked at heart rate variability, which is a parasympathetic nervous system function, without getting into too much detail. When we have flexibility in our autonomic state, that allows us to respond to the environment from the time that we are born throughout the end of our lives. Research shows that premies had less flexibility in their physiologic systems than babies born at term. Some studies looked at children early on. They found that children with less heart rate flexibility and responses to the environment had less self-regulation. So, I looked at children with autism that typically have rigid, stereotypical behaviors. I wanted to discover physiologically if there was something to that because physiological processes support behavior. A system that is not physiologically flexible is going to result in behaviors that are not as flexible. I believe that if we have a system that supports flexibility, then we can have behavioral flexibility.

I compared children with autism to a group of typically developing children. I looked at both their baseline heart rate variability and their heart rate variability in response to different sensations using the sensory challenge protocol, which was something that Lucy Miller had designed. I found that children with autism had much less physiologic flexibility with lower heart rate variability and baseline vagal tone than the typically developing children. Specifically, we found that children with autism had much less flexibility in responding to vestibular information than typically developing children.

When comparing mindfulness and understanding your senses, mindfulness is understanding with more clarity. Do you see the similarity?

Yes, I see a similarity. I think mindfulness is, or a large part of mindfulness, really is understanding your senses. However, I believe that sensory health is more than mindfulness because it is more informed than mindful practice. I think that is the key. Not only is it essential to understand your senses, but it is also essential to be responsive to that stimuli. It is not like, "I am hungry, and I am going to get something to eat." It is being more responsive to your sensory needs, differences, and patterns.

References

Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (1997). Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(2), 345-368.

Bar-Shalita, T., Livshitz, A., Levin-Meltz, Y., Rand, D., Deutsch, L., & Vatine, J. J. (2018). Sensory modulation dysfunction is associated with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. PLoS One, 13(8):e0201354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201354. PMID: 30091986; PMCID: PMC6084887.

Bazyk, S., Demirjian, L., Horvath, F., & Doxsey, L. (2018). The Comfortable Cafeteria program for promoting student participation and enjoyment: An outcome study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72, 7203205050. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2018.025379

Champagne, T. (2011). Sensory modulation and environment: Essential elements of occupation. Sydney, Australia: Pearson

DiLernia, D., Sernio, S., & Riva, G. (2016). Pain in the body: Altered interoception in chronic pain conditions: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Review, 71, 328-342.

Dean, E. E., Little, L., Tomchek, S., & Dunn, W. (2018). Sensory processing in the general population: Adaptability, resiliency, and challenging behavior. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(1),doi:7201195060p1-7201195060p8.

Dunn, W. (2001) The sensations of everyday life: Empirical, theoretical, and pragmatic considerations. 2001 Eleanor Clarke Slagle lecture. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55, 608-620.

Engel-Yeger, B. & Dunn, W. (2011) Exploring the relationship between affect and sensory processing patterns in adults. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(10), 456-464.

Engel-Yeger, B. & Rosenblum, S. (2017). The relationship between sensory processing patterns and occupational engagement among older persons. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84(1), 10-21.

Goldberg, A., Ebraheem, Z., Freiberg, C., Ferarro, R., Chai, S., & Gottfried, O. D. (2018). Sweet and sensitive: Sensory processing densitivity and Type 1 diabetes. Journal of pediatric nursing, 38, e35–e38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.10.015

Harrison, L. A., Kats, A., Williams, M. E., & Aziz-Zadeh, L. (2019). The importance of sensory processing in Mental Health: A Proposed Addition to the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) and Suggestions for RDoC 2.0. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 103. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00103

Hertzog D, Cermak S, Bar Shalita T (2019) Sensory modulation, physical activity and participation in daily occupations in young children. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 86(2): 106-113

Iacoviello, B. M. & Charney, D. S. (2014) Psychosocial facets of resilience: implications for preventing posttrauma psychopathology, treating trauma survivors, and enhancing community resilience. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1).

Klabunde, M., Acheson, D.T., Boutelle, K.N., Matthews, S.C., and Kaye, W.H. (2013) Interoceptivesensitivity deficits in women recovered from bulimia nervosa. Eating Behaviors, 14, 488-492Doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.08.002

Kosiecz A, Taczała J, Zdzienicka Chyła A, Woszczyńska M, Chrościńska Krawczyk M (2019) The level of physical fitness and everyday activities vs sensory integration processing disorders in preschool children – preliminary findings. Journal of Education, Health and Sport 9(6): 319324.

Mahler, K. (2017). Interoception: The eighth sensory system. AAPC Publishing.

Mahler, K. (2019). The interoception curriculum. AAPC Publishing.

Meredith, P. J., Rappel, G., Strong, J., & Bailey, K. J. (2015). Sensory sensitivity and strategies for coping with pain. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69, 6904240010 https://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.014621

Paulus, M.P., & Stein, M.B. (2010). Interoception in anxiety and depression. Brain Structure and Function, 214, 451-463. Doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0258-9

Paulus, M. P., Stewart, J. L., and Haase, L. (2013). Treatment approaches for interoceptive dysfunction in drug addiction. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4:137.

Porges, S. (2011). The polyvagal theory. W.W. Norton and Company., Inc.

Seo, J. G., Park, S. P. (2019). Clinical significance of sensory hypersensitivities in migraine patients: Does allodynia have a priority on it? Neurology Science, 40(2):393-398. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3661-2. Epub 2018 Dec 1. PMID: 30506413.

Citation

Cavaliere, C. M. (2021). Sensory health: The missing piece in the wellness conversation. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5474. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com