Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Sexuality And Intimacy Considerations: Pediatric Acute Care Virtual Conference, presented by Alex King, OTR/L, CCLS.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify at least 2 assessment tools directly applicable to addressing sexuality and intimacy in the pediatric acute setting.

- After this course, participants will be able to distinguish between the OT role in sexuality and intimacy and the roles of other interdisciplinary team members and compare and contrast at least 2 aspects of sexuality and intimacy routinely addressed for each age group (infant, toddler, school-age, adolescent).

- After this course, participants will be able to identify at least 2 sources for gathering and updating information regarding local/organizational policies/laws associated with the boundaries of confidentiality, mandatory reporting, adolescent privacy, and consent.

Introduction

Today will be a not-sterile but not-super-intense introduction to sexuality and intimacy considerations for the pediatric population in acute care. This presentation is designed for both the advocate and the skeptic, so I'm hoping everybody can get a little something out of it.

Scope Accountability

- Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process

- AOTA 2020 OT Code of Ethics

- Licensure Act

- Patient Rights – INFORMED CONSENT

Scope accountability refers to the responsibility of a provider to ensure that all recipients of their care receive the full range of services available within their scope of practice. The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework in the US is our most comprehensive document that captures these aspects.

The AOTA 2020 OT Code of Ethics offers guidance on applying the framework inclusively and understanding the needs of diverse populations. This requires a deep understanding of ourselves and the expectations for providing inclusive care. Each state's licensure acts are unique, so it's crucial to know the specific permissions granted by your licensure act. Additionally, understanding the licensure acts of other professions is important to know what privileges they have been given and how it might impact our own practice.

Working with your state organizations to understand licensure rules is essential. Understanding patient rights, including pediatric patient rights, is equally important. Informed consent is a fundamental aspect of healthcare in America and many other countries. It requires informing the client about the nature of your care, who you are, your scope of practice, and the services they can access. Without presenting the full scope of care available within our profession, we fail to provide the client the opportunity to give informed consent and choose which services to access.

OT Role-OTPF-4

Explicit OTPF-4 Statements

Sexual activity

| Engaging in the broad possibilities for sexual expression and experiences with self or others (e.g., hugging, kissing, foreplay, masturbation, oral sex, intercourse) |

Personal care device management

| Procuring, using, cleaning, and maintaining personal care devices, including hearing aids, contact lenses, glasses, orthotics, prosthetics, adaptive equipment, pessaries, glucometers, and contraceptive and sexual devices |

Social and emotional health promotion and maintenance | Identifying personal strengths and assets, managing emotions, expressing needs effectively, seeking occupations and social engagement to support health and wellness, developing self-identity, making choices to improve quality of life in participation |

Intimate partner relationships | Engaging in activities to initiate and maintain a close relationship, including giving and receiving affection and interacting in desired roles; intimate partners may or may not engage in sexual activity |

1AOTA (2020)

In the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF), our role is explicitly defined within the context of sexuality and intimacy. Sexuality is identified as an Activity of Daily Living (ADL) and encompasses all aspects of physical sexuality and its expression, both independently and with others. This includes personal care, device management, social and emotional health promotion, and intimate partner relationships. Each of these areas involves specific roles, such as using contraceptives, managing sexual devices, accessing activities with the help of devices, and understanding our roles in developing intimacy and safety in intimate relationships.

Implicit OTPF-4 Statements

- All of it...

Exhibit 1. Aspects of the Occupational Therapy Domain All aspects of the occupational therapy domain transact to support engagement, participation, and health. This exhibit does not imply a hierarchy. | ||||

Occupations | Contexts | Performance Patterns | Performance Skills | Client Factors |

•Activities of daily living (ADLs) •Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) •Health management •Rest and sleep •Education •Work •Play •Leisure •Social participation | •Environmental factors •Personal factors | •Habits •Routines •Roles •Rituals | •Motor skills •Process skills •Social interaction skills | •Values, beliefs, and spirituality •Body functions •Body structures |

1AOTA (2020)

Throughout the OTPF, our role offers implicit opportunities to understand the role of sexuality. Occupations and client factors within our domain, as expressed in the OTPF, include aspects of daily life that affect our ability to access and build intimate relationships and participate in sexuality and sexual activities. When considering access to ADLs, instrumental activities of daily living, health management, rest, and sleep, all of these areas can address aspects of sexuality.

For many, addressing sexuality becomes more comfortable when they realize that interventions often focus on preparatory activities. This might include helping clients access environments where they might meet someone for intimate relationships, preparing their bodies for sexual activity, understanding bodily responses, and learning how to protect themselves in intimate situations. These are all within our scope of practice and are activities we regularly engage in with our clients, making the subject of sexuality more approachable and integrated into our daily work.

Premise

- IF occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) complete an occupational profile for every client…

- AND Self-care, social participation, and sexual participation are defined aspects of a complete occupational profile…

- AND all clients have the right to a full understanding of the scope and potential utility of OT services in order to provide INFORMED CONSENT for those services and the provider offered…

- THEN…

The idea is that if occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) complete an occupational profile for every client, as outlined in the OTPF, and since self-care, social participation, and sexual participation are defined aspects of a complete occupational profile, then all clients have the right to a full understanding of the scope and potential utility of OT services. This ensures that each client is aware of how OT can address various aspects of their lives, including intimate and sexual participation, thereby promoting a comprehensive approach to their care and well-being.

- Every OT evaluation should include an explanation of the role of OT in self-care, social participation, and sexual participation…

- AND

- …at minimum, the opportunity to express the need/desire for those services.

To provide informed consent for occupational therapy services, every OT evaluation should explain the OTP's role in self-care, social participation, and sexual participation. This ensures that clients are fully informed about the scope of OT and can express their need or desire for these services. By including this explanation in evaluations, we ensure that clients understand how OT can support various aspects of their lives and that they can make informed decisions about their care.

Your Team in Acute Pediatrics

- Acute Care

- Client/Family

- Pediatrics

- Adolescent Medicine

- Psychology

- Psychiatry

- Nursing

- Gynecology

- Urology

- Social Work & Counseling

- Admin/Legal

- After Discharge:

- Child/Family

- Pediatrician/PCP

- School

- Case Management

- + Referred Services

The good news is that we are not alone; many team members are involved in this care. Sometimes, our role is to understand the client's needs and connect them with the right providers or educate them on how to access these providers, which is part of the health management piece. After clients are discharged from the hospital, professionals are still prepared to help them. In the hospital, we have access to various resources to bring the necessary support, ranging from surgical to psychosocial.

Upon discharge, if we prepare them correctly and make effective discharge recommendations, we provide them with tools for their family, themselves, their pediatrician, PCP, school, case management, and referred services. These referred services may or may not include occupational therapy to continue addressing their needs post-discharge.

Why OT’s Role is Special?

- Occupational Profile

- Task Analysis

- Potential for Consistent Outpatient Support

- OT provides a link between the lived experience and the clinical assessment/plan.

Our role is crucial because we provide access to the occupational profile. We are often the only professionals who enter the room with the primary goal of understanding who the client is, how they live their lives, and what is most important to them. We prioritize understanding the person before considering their health condition, allowing us to see how their health condition and new experiences might affect them. We aim to link their lived experience and the clinical assessment and plan.

Key aspects of our role include the occupational profile, task analysis of all involved activities, and the potential for consistent outpatient support on a referral basis after discharge. This approach makes much sense, especially for adults, and is generally well-received.

- "...but this is peds?

- “These families aren’t thinking about that right now?”

- “I’m not comfortable talking about sex in my personal life. I can’t imagine talking about it at work!”

- “I don’t think families would trust me if I brought up sex…”

- “I know it’s important, but I don’t know what I’d do if they actually said they wanted me to help with it.”

- “I don’t believe masturbation is okay, so I’m not going to help someone participate in it.”

- “There are so many things going on. There’s no way this is a priority, right?”

- Is it even appropriate? Or LEGAL?

There are numerous barriers and concerns when addressing topics related to sexuality within the pediatric population, and we will address some of these today. Many concerns stem from whether the topic is even on the patient's or their family's mind when admitted for another health condition. We may think that families will lose trust in healthcare providers or develop assumptions about them if the topic of sex is brought up. Additionally, many people are uncomfortable discussing sex in their personal lives, and therapists might feel unprepared to address such topics. There are also concerns about the appropriateness or legality of discussing sexuality with pediatric patients, which involve personal assumptions and legal ramifications that we will explore today.

Barriers to Practice

- Facility/Organization Culture/Policies

- Personal Perspectives/Culture/Values

- Assumptions of Client Perspectives/Culture/Values

- Fear of…

- Reactions

- Awkwardness

- Legal/Organizational Responses

- Competence (Actual and/or Perceived)2

2Larson et al. (2021)

Barriers to addressing sexuality in pediatric practice include facility and organizational culture. If our teams and interdisciplinary groups are not expecting us to address these topics, there is no expectation to follow through. Resistance can also arise when you are the sole person in your facility or team willing to discuss sexuality. This often leads others to defer to you on this topic, which can occur in healthcare facilities, outpatient settings, and even university programs. When someone specializes and feels comfortable with a subject like this, it allows others to avoid an uncomfortable topic, presenting a significant challenge.

Personal perspectives and values are another potential barrier. Regardless of our practice area, we must understand our own assumptions and perspectives to support our clients inclusively. Clients may also have perspectives, cultures, or values that we are unaware of, and making assumptions without including them in their occupational profile can lead to incomplete care. Time constraints often make it challenging to integrate all personal values into the context of obtaining equipment and ensuring safe discharge planning.

One of the biggest barriers is the fear of reactions, awkwardness, and potential legal or organizational repercussions. Concerns about getting in trouble, wondering what others will think, and personal discomfort can hinder our ability to make clients feel comfortable. Research, particularly within the neurodivergent population, indicates that the primary barrier is competence. When surveyed, occupational therapy practitioners often cite a lack of confidence or the necessary skills and tools to address these topics. Today, we will discuss some of these tools to help you feel more prepared and know where to find the resources you need.

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) Perspectives

- Spina Bifida Association – CPG for Sexual Health and Education3

- “Maximization of the ability of adults with Spina Bifida to participate as desired in meaningful and fulfilling sexual relationships through the provision of accurate sexual health education across the life span.”

- **RECOMMEND EDUCATION STARTING AT 0-11 MONTHS and continuing through lifespan.**

- **23 Guidelines prior to the age of 13 years. Additional 26 guidelines between 13-18+**

- CPG on Sexuality for Epidermolysis Bullosa4

- “Families of infants diagnosed with EB should be provided the opportunity for discussion of future sexual participation to minimize assumptions about sexuality-related limitations.”

- “Family and child/adolescent readiness for pubertal transition should be assessed in early development.”

3SBA (2018); 4King et al. (2021)

One more justification for providing this service within the acute and pediatric population is that clinical practice guidelines (CPG) for conditions such as spina bifida and epidermolysis bullosa have started to include recommendations for addressing sexuality with children, even down to the NICU level. These guidelines are developed in collaboration with community members, and the goals and perspectives they reflect are informed by clinicians and community members. They are driven by an extensive literature review, ensuring that they are grounded in the values and needs of the population, and they are developed through consensus decisions. This process is designed to be reliable and reflect the community's true needs.

For instance, the Spina Bifida Association's Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) for sexual health and education recommend starting education for families when children are between zero to eleven months old and continuing through the lifespan. The guidelines include 23 recommendations for addressing sexuality with families before the age of 13 and an additional 26 guidelines for ages 13 to 18 and into adulthood. These recommendations highlight the importance of early and continuous education on sexual health and relationships.

The CPG for sexuality and epidermolysis bullosa specifically recommends that families of infants diagnosed with the condition be allowed to discuss future sexual participation. This is to minimize assumptions and sexuality-related limitations and to assess family and adolescent readiness for pubertal transitions early in development.

As someone involved in developing these guidelines, I can attest that one significant reason for these recommendations is the feedback from surveys sent to families and adults with these conditions. Many current adults reported growing up with the belief that sexuality and intimacy were not accessible to them, leading to significant challenges in finding their sexual and intimate identities later in life. Parents also expressed a strong desire for a place to ask questions and alleviate the stress and anxiety about their child's future in terms of sexuality and intimate relationships. These insights underscore the importance of including discussions about sexuality in pediatric care to support both the patients and their families effectively.

Okay...Then How?

So, if we're convinced that we should address this in acute care and pediatrics, then the question is, how are we going to do that?

The Introduction

- Introduce intimacy and sexuality as part of your role from day/minute one.

- Develop a personal introduction of OT services that ensures clients are aware that you are a safe and appropriate place to ask questions about puberty, sexuality, intimacy, and relationships

The most important step is to assess yourself and whether your facility is ready to address these topics. Start by identifying the language you use and evaluating if you have educated yourself enough on LGBTQ health and diverse cultural perspectives on sexuality. This self-assessment ensures you feel comfortable and open to clients' perspectives and questions.

To become comfortable talking about sexuality and intimacy within your practice, begin by incorporating this language into your daily interactions. When new clinicians integrate these topics into their daily language and strategies, I suggest starting with their introduction. Consider your elevator speech and how you introduce OT services to patients and families. Is there a way to include topics related to sexuality, intimacy, puberty, or relationships in that initial conversation? This helps set the tone, letting them know you are safe and approachable for these discussions.

Almost no other provider will directly acknowledge and provide permission to discuss these topics, which makes it essential for us to do so. Not every question will require you to have the answer, but creating a space where these questions can be asked is vital. You can then provide health management education and training to help them identify the appropriate provider and learn how to communicate and access the support they need. This approach helps normalize the conversation and supports clients in addressing these important aspects of their lives.

Clarify Your Role and Its Boundaries…

- Things every clinician should research and know:

- Professional Skills, Knowledge, and Limitations

- Personal biases, needs, traumas, or boundaries

- Licensure laws governing practice

- Organizational policies and procedures affecting practice

- Geographically-relevant laws about…

- Sexual activity, consent, and age requirements

- Mandatory Reporting Requirements

- CONFIDENTIALITY in pediatric, adolescent, and adult care

- APPROPRIATE REFERRAL DESTINATIONS

5Hoover et al. (2020)

Once you've identified addressing sexuality as part of your role, it's important to clarify exactly what that role entails and where its boundaries lie. Firstly, we must recognize our professional skills and limitations, as our licensure holds us accountable for understanding both. While we can present the full scope of OT services to clients, we also need to know when to refer to other team members if certain issues fall outside our skill set.

In acute care with pediatrics, if we frequently encounter questions we can't answer, we should leverage our multidisciplinary team members to fill those knowledge gaps. Continuing education courses can also help expand our understanding. It's essential to be aware of our biases and figure out how to introduce ourselves to families in an open and honest way. Our biases, needs, traumas, and boundaries must be managed to provide safe and effective care. If addressing certain topics compromises the safety or comfort of either the clinician or the client, it should be clear that a referral to another provider is necessary. While it’s acceptable to feel unprepared or uncomfortable, denying clients the option to discuss these topics is not acceptable, as this is part of informed consent.

Understanding licensure laws is crucial. Some licensure laws explicitly include addressing sexuality, while others might not use specific terms but include related concepts like social participation or psychosocial health. Knowing where your licensure act includes these aspects helps you communicate with your organization, families, and potentially legal entities about why you are providing this service. Organizational policies and procedures can also impact practice. If your facility lacks LGBTQ inclusion awareness or training, it can be challenging for families to feel safe discussing these topics. Assumptions about bodies, preferences, orientations, and identities are often incorrect, making it more important to provide an open and safe space for clients to share who they are and what they need.

Geographically, laws differ, so understanding your state’s laws beyond licensure is vital. This includes mandatory reporting laws, which differ by state and primarily apply to abuse. Knowing what you must report helps you inform families and clients about these boundaries. When they share information, they understand the implications and are effectively asking for help.

Confidentiality laws also vary, especially regarding pediatric, adolescent, and adult populations. For example, the age of consent for sex might differ from the age at which confidentiality protections kick in for certain healthcare services. Knowing these laws helps you navigate situations where an adolescent might share sensitive information. Using allies within your facility, such as adolescent medicine, the legal department, and compliance, is essential for understanding these boundaries and maintaining trust with your clients.

When clients bring up issues related to sexuality, it's often necessary to refer them to the appropriate specialists. For instance, if a client has issues with continence, you might address functional strategies but still refer them to urology. Having all providers in the same place is an advantage in acute care pediatrics. Accessing mentorship, education, and consults from these specialists ensures comprehensive care. Referrals for follow-up after discharge are also crucial for continuous support.

By understanding your role, clarifying boundaries, staying informed about laws and policies, and knowing when to refer to specialists, you can provide effective, inclusive care that addresses all aspects of your client's needs.

Introduce the Ex-PLISSIT Model

- Permission (at every level of discussion)

- Limited Information

- Specific Suggestions

- Intensive Therapy

As we move through this process, we need our clients to understand how to address these topics. It's important to communicate how the conversation about sexuality and intimacy will unfold. The Ex-PLISSIT model provides a useful framework for this, ensuring that permission and consent are obtained at every level of intervention.

When you introduce your services and explain your role in the setting, you provide clients with clear, informed information about what you are there to offer. They give implicit consent to address these topics by welcoming you into their room. As you progress through the occupational profile, clients might ask questions, or you might need to ask them questions. It's crucial that they know they can choose not to answer or can ask for more information if needed. Always ensure they have the opportunity to express comfort, ask further questions, or end the conversation at any point.

Providing limited information within the Ex-PLISSIT model involves being prepared with basic information and resources. This could include handouts from community organizations or referral sources like adolescent medicine, which can offer guidelines on boundaries of confidentiality in healthcare or consent for sex in your state. Having this information readily available ensures you can provide initial answers and direct clients to appropriate resources.

If clients have further questions and it’s within your scope of practice, you can offer specific suggestions. For instance, if a client asks about accessing masturbation, you might provide advice on building daily routines, ensuring privacy, and communicating needs. These aspects are well within the scope of occupational therapy and can be seamlessly integrated into ADL routines.

Knowing your referral sources is essential in cases where ongoing treatment is needed. Intensive therapy might not always fall within OT’s scope, but understanding when and how to refer is key. For example, if the primary barrier to accessing intimate and sexual relationships is environmental or related to initiating interactions, OT can provide intensive therapy to develop psychosocial strength, build identity, and facilitate deeper relationships.

Contrary to what I learned in school, where intensive therapy for sexuality was often considered exclusive to sex therapy, the OTPF model shows that OT can address many factors affecting sexuality. Even before sexuality becomes relevant at a certain age, we can help clients develop prerequisite skills for this stage of development.

Additionally, intensive therapy might include recommending durable medical equipment (DME) for bathing, toileting, or positioning, which can influence how clients access and engage in sexual activities. By following this approach, we ensure comprehensive and client-centered care, addressing sexuality and intimacy within the scope of occupational therapy.

Be Ready to Assess...

- Occupational Profile2 (COPM, etc.)

- Occupational Performance Inventory of Sexuality and Intimacy (OPISI)6

- Occupation and/or Skill-specific Measures

- MOST IMPORTANTLY…

- Build an effective therapeutic relationship based on authenticity and unconditional positive regard.7

1AOTA (2020); 7Walker et al. (2019); 8Rogers (1995)

When addressing sexuality with clients, it is crucial to be ready to assess them thoroughly. The occupational profile is your primary assessment tool; you can't perform an OT evaluation without it. Tools like the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) and the Child Occupational Self-Assessment (COSA) are excellent for quickly and effectively understanding who the client is and how their current health condition or situation might affect their life. These measures allow clients to discuss various aspects of their lives without delving into exhaustive detail.

My favorite assessment tool for sexuality and intimacy is the Occupational Performance Inventory of Sexuality and Intimacy (OPISI). This tool offers a comprehensive approach to assessment and intervention, guiding the therapist and the client through the process. One of the best features of the OPISI is its screener, a one-page assessment that introduces the topic and allows clients to express whether they want to discuss these areas further. The screener covers a range of topics, from self-identity and self-care to interactive, interpersonal experiences, including orgasms, erections, and masturbation. This initial step ensures that consent is obtained at every stage, making it easy to gauge the client's comfort level and knowledge about these topics.

In addition to specific sexual activities, many client needs may relate to other areas that impact their ability to engage in sexuality and intimacy. Fine motor, oral, communication, and relationship development skills are often integral to this aspect of life. You can identify and address specific challenges by conducting a thorough task analysis. For instance, ensuring that a client's wheelchair is appropriately set up for intimate activities or that they have the necessary hygiene and grooming skills supports their readiness for these experiences. These are areas we frequently address but don't always link explicitly to sexuality. By supporting ADLs and related skills, we enhance clients' access to and participation in sexual activities.

The foundation of this work lies in developing a therapeutic relationship with your client. Carl Rogers' concept of authenticity and unconditional positive regard is fundamental. Authenticity means bringing your true self and honestly presenting your services, creating a safe space for clients to do the same. Unconditional positive regard involves accepting and valuing clients regardless of their identities, interests, pleasures, or pains. Maintaining this stable and supportive relationship ensures that clients feel safe and respected, allowing them to share openly and engage fully in the therapeutic process.

If there's one skill to focus on, it’s building an effective therapeutic relationship. Establishing a genuine and supportive connection is paramount when addressing difficult topics, sensitive issues, or simply understanding a client's occupational profile. This relationship forms the basis for all therapeutic work, ensuring clients feel comfortable and supported as they navigate their challenges and explore their identities.

Intervention...

- Values & (Occupational) Identity

- Social Participation & Intimacy Skills

- Performance/Participation in Sexual Activity

- (Includes associated skill areas – ADLs, Health Management, Daily Routines, etc.)

- In-Hospital Needs Recommendations

- **Future/Prospective Participation**

As we move past the assessment phase and establish a trusting relationship with our clients, we often find that the primary intervention revolves around helping them identify their values and occupational identity. This enables them to live comfortably in the spaces and environments necessary for accessing various occupations, including sexual participation. Sexual participation is complex, even on an individual level, and understanding what people need and want from this aspect of their lives is crucial.

We can work on social participation and intimacy skills, as well as performance and participation in sexual activities. This might involve developing routines, facilitating communication with family members, and adapting medical devices that allow for privacy for the pediatric population. For instance, we might recommend a chair that provides more stability or flexibility to meet both daily care and grooming needs and sexual health needs. These recommendations often integrate into our broader support of ADLs and health management routines.

Our role as OTPs in the hospital encompasses addressing immediate in-hospital needs and future prospective participation. In the hospital, we ensure clients can access parts of themselves safely and comfortably. This might include providing privacy and understanding why certain issues, such as falls or skin breakdown, occur. By conducting thorough assessments, we sometimes uncover underlying factors related to sexuality and intimacy that contribute to the client's primary health condition. This holistic approach often provides the healthcare team with vital information to support and treat patients more effectively.

For future participation, we consider how to support clients as they develop into sexual beings. This involves preparing them and their families for the changes and challenges of puberty, helping them understand their sexual identity, and providing ongoing support. This comprehensive approach ensures that clients are equipped to navigate their sexual health and intimate relationships throughout their development.

In essence, our interventions should focus on helping clients build the necessary skills and environments for healthy sexual participation. This includes working on social and intimacy skills, addressing performance in sexual activities, and ensuring that their physical and emotional needs are met both in the hospital and as they transition into their everyday lives. By doing so, we not only support their immediate health but also their long-term well-being and development.

Intimacy as a Developmental Process

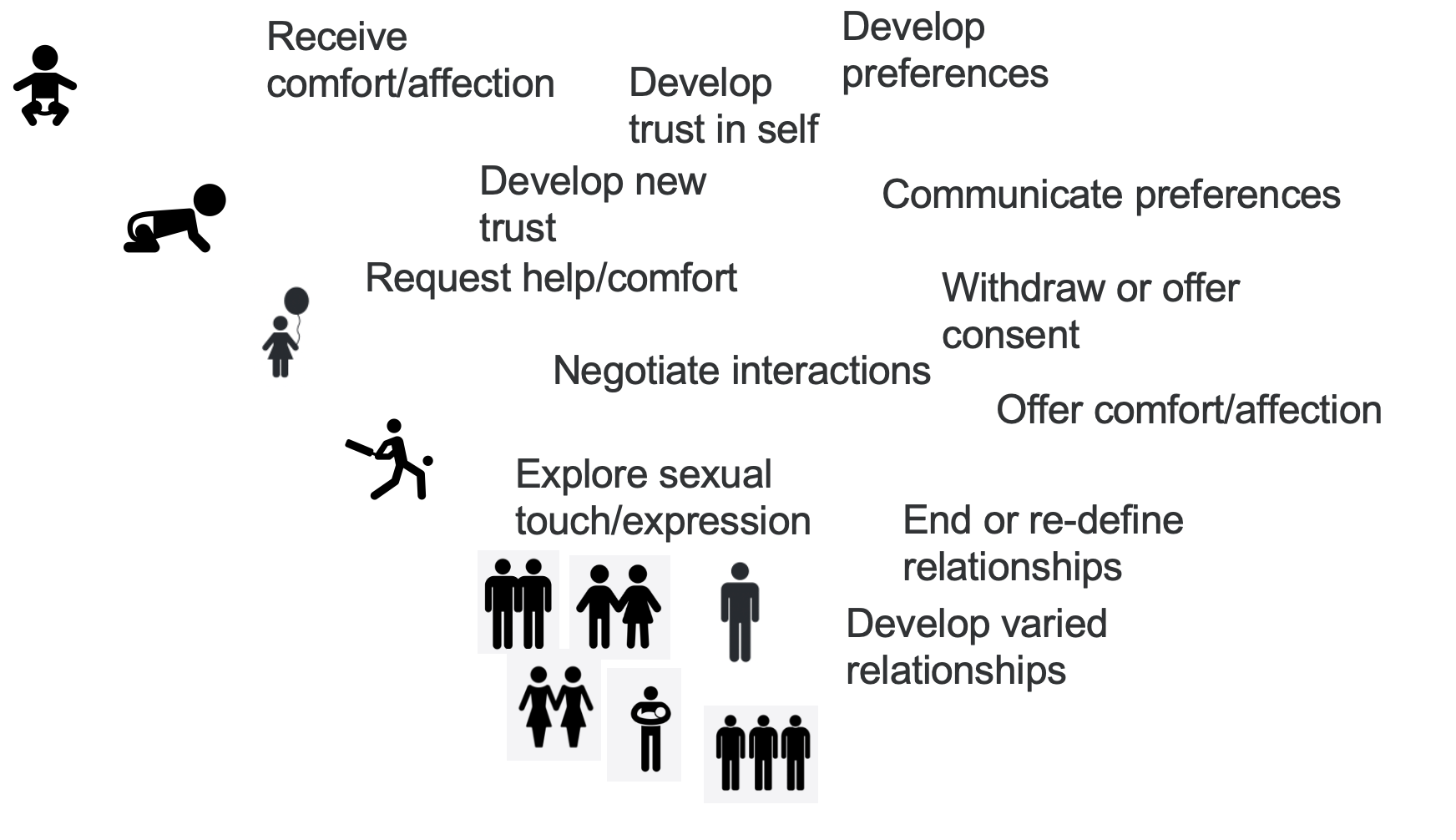

As we discuss providing ongoing care and setting families up for success, it's important to realize that intimacy is a developmental process in and of itself (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Illustration of intimacy as a developmental process.

Intimacy development involves learning to receive comfort, trust ourselves, develop preferences, and gradually build trust with new people. It includes communicating our preferences, requesting help and comfort, withdrawing consent, and saying no to help and comfort. It involves negotiating interactions, understanding mutual needs, and determining how to meet them. Offering comfort and affection, exploring sexual touch and expression with oneself and others, and learning how to end and redefine relationships are all parts of this process. Relationships can take many forms, including varying levels of intimacy and sexuality, which will look different for each person.

Given our psychosocial scope, it is crucial to help people identify their strengths and areas for growth in these skills. We assist them in understanding which skills they excel in, which ones they feel confident about, and which ones impact their daily lives and relationships.

A trauma-informed care approach can help us see the foundations of these skills at a very young age, even in infancy. This approach often frames challenges in terms of attachment and behavior, identifying perceived "problems" in how a child is developing or coping with situations. However, these processes are fundamentally about learning how to connect with and trust others. Children are learning to find people who offer unconditional positive regard, where they can be themselves and still be accepted.

The more we educate families on creating such environments, the better we can support the child's development. This education involves teaching families what to expect and cautioning against making assumptions about their child's future sexual function. By doing so, we equip families with the tools they need post-discharge to continue supporting their child's development and accessing additional support when necessary.

As occupational therapy practitioners, our role includes facilitating this developmental process. We support families in creating safe, accepting environments where children can learn to trust and express themselves. We provide education and resources to help families understand and nurture their child's development in intimacy and sexuality. By doing so, we help children build the skills they need for healthy relationships and self-expression, both now and in the future.

Discharge Planning

- Ongoing needs vs. Future access to care

- Home Programs/Strategies/Recommendations

- Referral Planning

That's where discharge planning becomes essential. In the acute care setting, we often can't address the intricate details of sexuality, intimacy, and relationship development unless the patient is there for a condition that requires a recurrent or extended hospital stay. In those cases, we have the opportunity to work on and hone these skills, demonstrating the significant impact OT can have in this area. When referring to outpatient OT, it's crucial to inform families about what to expect, how to find a provider, and how to ask if they can provide the necessary services.

We need to educate families about ongoing needs and future access to care. This involves explaining what OTPs do in the hospital and what they can offer in outpatient settings and as their child develops. Families need to know when to access OT services and how to choose the right providers. Providing home program strategies, recommendations, and equipment to support these needs is vital. For instance, if we're ordering a wheelchair or bath chair for a person with a new chronic physical condition, we should include considerations for intimacy and sexuality in the selection of that equipment.

Finally, referral planning is crucial. Identifying the right providers outside the hospital who can continue to support the patient’s development is essential. This ensures that patients and their families have a clear understanding of how to continue the process of developing intimacy and sexuality skills and how to access the necessary care as they progress. By integrating these elements into discharge planning, we can provide comprehensive support that extends beyond the acute care setting and promotes long-term well-being and development.

Case Studies

We're going to apply some of these concepts in some case studies. These are all real cases, with a few aspects changed for confidentiality.

Case #1

- 10-day-old with MMC (hx in-utero closure) in NICU following full-term delivery for r/o HC preparing for DC home with family.

- OT Consult for family education/training re: positioning and developmental recommendations.

- Base competency: Intro of services/scope, resources if requested (per CPG), refer to specialists if needed.

- Higher/Specialized competency: If requested by the family, provide detailed information and/or examples of specific suggestions/therapies available. Use the OPISI if appropriate to help guide the conversation with families.

Case number one involves a ten-day-old infant with myelomeningocele who had an in-utero closure and is now in the NICU following a full-term delivery. The primary goals are to rule out hydrocephalus and prepare the family for discharge. The OTP is consulted for family education and training on the condition, its progression, and to provide positioning and developmental recommendations for both the hospital and home settings.

An OTP with basic competency might introduce the scope of OT services, including discussions about intimacy and sexuality through the lifespan. They would provide resources like the spina bifida CPG to help the family understand future expectations and identify specialists they might need to consult.

If requested, an OTP with higher specialized competency in this area could provide the family with more specific examples and suggestions. They might use the OPISI to allow the family to consider aspects of sexuality and intimacy and how these might be affected by their child's health condition. By discussing these topics early, even if specific recommendations or information are not requested, the family knows they are in a safe environment to ask questions. They are informed about which medical providers to approach in the future, how to engage with a multidisciplinary clinic, or how to initiate conversations with their PCP for necessary referrals. This empowers them to take charge of their child's developmental progress and access appropriate support.

Case #2

- 15-year-old (he/him) admitted s/p AKA for tx. of osteosarcoma following unsuccessful conservative treatments x3 years.

- OT Consult for ADLs, Safe Discharge Planning.

- OT EVAL: Client shares that puberty started about 6 months ago. He has used ADL times as opportunities for masturbation and has been grooming around his genitals. Now he’s concerned about receiving support from parents for ADLs and losing access to privacy for masturbation and self-care.

- Base competency: Validate, Normalize, Discuss alternative support systems – equipment/adaptation, home health/attendant care services, etc.

- Higher/Specialized competency: Motivational interviewing to establish values and understanding of options and rights. Support client in communicating/self-advocating for those needs.

A 15-year-old is admitted to acute care status post aka for treatment of osteosarcoma following unsuccessful conservative treatments for three years. The OTP has been consulted for ADLs and safe discharge planning.

The client shares that puberty started about six months ago. He's had privacy within his ADL time that he's used for grooming around his genitals and accessing masturbation. Now, he's concerned about the level of support he needs to receive from his parents and losing access to that privacy and space. At a base competency level, we can validate the experience, we can help normalize it and help them understand stage appropriate development as well as discuss alternative support systems. Do we need to change our equipment or adaptation recommendations to increase ADL independence or access certain ADL environments independently? At this stage, do we need to change daily care routines or provide opportunities in daily care routines to provide a safe or private space or access to communicate the need for privacy to the family? They may not want their family to see them during this private time. They may want to know their options for home health or care services, and accessing other providers that aren't their families, even if their family is willing to provide that support in those ADL environments, is something that all of our OTPs are qualified and can do at the base competency.

At a higher, more specialized level, you might provide a motivational interviewing approach to establish what their values and understanding of their options and rights really are and then support the client in communicating and self-advocating those needs to their family. We can be the person who helps the person identify exactly what their concerns are and their stressors are and how to communicate that to their family. And sometimes, even if it's something that is legally confidential and we can't share with the family because the client shared it with us and it's protected a lot of the time, we aren't the person they want to know.

They need to be able to communicate that to the family. By providing a safe space where they can clarify those values and needs for themselves and then have a medium for discussing that with their families, we can give them that opportunity and prevent the disability and psychosocial stress that may result if we don't address it.

Case #3

- 14-year-old (he/him) with acute admission for SI. PMH of tethered cord, surgically corrected at 8y.

- OT for self-care skills and state regulation/sensory processing.

- OT Eval: OP reveals client recently had first sexual experience with another 14-year-old. When he ejaculated, the peer was upset about the mess and said it wasn’t normal. Shame, bullying, and fear followed.

- Base Competency: Validate/Normalize. Discuss Team Roles - Refer.

- Higher/Specialized competency: Offer education on ejaculatory incontinence and tethered cord recurrence. Apply to other ADL routines and experiences to gather more information to the team. Support client in communicating these concerns. Provide psychosocial intervention during admission and refer for ongoing OT if needed.

This is a 14-year-old with acute care admission for SI and a prior medical history of tethered cord surgically corrected at eight. The OTP is consulted for self-care skills, self-regulation, and sensory processing. The occupational profile reveals that the client recently had a first sexual experience with another 14-year-old when he ejaculated.

The peer was upset about the mess and said it wasn't normal. Shame, bullying, blame and fear followed. At a base competency, we can validate and normalize like we did in the last one. We can discuss the roles of the team and refer. So, for instance, someone with a tethered cord who's having ejaculatory concerns can talk to their pediatrician, their adolescent medicine doctor, or their urologist about that need.

When you build your therapeutic relationship, you might be able to offer education on ejaculatory incontinence and how that might be associated with a tethered cord. It also might help you identify that there's a tethered cord recurrence, which is the first symptom they're actually experiencing. You can apply to other ADL routines and experiences to gather more information for the team and then communicate all of those things. It may actually lead to a diagnosis process within the healthcare world that reveals a primary condition that's leading to the symptom that caused the psychosocial experience that resulted in the SI. So supporting the client in communicating these concerns, understanding and normalizing those, and then providing psychosocial intervention during the admission and then referral for ongoing OT afterwards.

Case #4

- 10-year-old with PMH of SCI admitted for constipation.

- OT Referral for toileting positioning recommendations.

- OT EVAL: Family asks to speak to therapist after eval. Family vocalizes concern about upcoming pubertal transition. Current OP OT works on fine motor skills and core strength – reports that they don’t address sexuality/puberty.

- Base Competency: Validate. Normalize. Educate on OT’s Role. Follow the Ex-PLISSIT Model in providing CPGs or other resources + Team Roles review/referral.

- Higher/Specialized competency: Provide motivational interviewing approach to developing dx-specific strategies for family to utilize in providing support through development – Introduce the role of B&B management in sexuality for people living with SCI.

A ten-year-old with a prior medical history of spinal cord injury is admitted for constipation. The OT referral is for toileting and positioning recommendations. During the OT evaluation, the family requests to speak to a therapist afterward. They express concerns about upcoming pubertal transitions. The current outpatient OT focuses on fine motor skills and core strength but does not address sexuality and puberty.

We can validate and normalize the family’s experience at a base competency level. We can educate them on the full scope of the OT role, enabling them to communicate this to their provider and select a different provider if needed. Following the Ex-PLISSIT model, we can provide clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) or other resources and outline the roles of the healthcare team.

If we feel comfortable and are at a higher level of competency, we might use motivational interviewing to develop diagnosis-specific strategies for the family to support their child through development. We might introduce the role of bowel and bladder function and other aspects of continence or sexual performance and intimacy skills.

The primary challenge might often be connecting with peers, making new friends, body image, or similar issues. By conducting a thorough task analysis, we can identify if addressing these skills with their primary OT will help in areas indirectly related to sexuality. For example, improving social skills or body image can support their development and ease pubertal transitions. Providing this comprehensive support ensures the family has the resources and understanding to navigate these changes effectively.

Summary

As we discussed today, we've identified several assessment tools directly applicable to addressing sexuality and intimacy. We've also distinguished our role from those of interdisciplinary team members and understood that developing skills for sexuality and intimacy and processing these aspects as a family happens differently from infancy through adolescence and adulthood. Additionally, we've talked about the importance of being aware of laws and organizational policies, which are crucial not only when addressing sexuality but in any interaction with adolescent, adult, or pediatric patients.

Understanding patient rights, the limits of what you can legally share with families, and confidentiality implications is vital whether you plan to address these topics or not. As a strong therapist, creating a strong therapeutic relationship and a safe space for patients to share their identities, interests, and daily activities is fundamental. This environment encourages openness, and patients are likely to share sensitive information.

If you're not clear on relevant laws and policies, you risk unintentionally violating them. Creating a safe and trusting space means being prepared for the possibility that patients will share deeply personal information. Ensuring that you understand confidentiality laws and organizational policies helps prevent accidental breaches of trust and maintains the integrity of the therapeutic relationship.

Exam Poll

1)The Ex-PLISSIT Model stands for ALL EXCEPT:

The correct answer is liability information. Liability information is very important, but it is not included in the Ex-PLISSIT model. The key components are permission, specific suggestions, and intensive therapy. The piece that we're missing in this list is limited information, which is providing a certain amount of information that's either general or very specific.

2)What is most important when addressing sexuality with a client?

The answer for Question 2 is C. The therapeutic relationship is everything.

3)OT intervention includes:

All of those things are included in our scope.

4)OTPs can address intimacy as a developmental process. What area is included in this process?

Again, the correct answer is D, all of the above.

5)In Case #1, what resource could help guide the conversation about future sexual participation?

All of these things are important, and all could be used, but the OPISI is the most detailed opportunity to talk to them and provide opportunities to talk about specific concerns or aspects of future participation.

Questions and Answers

What is your elevator speech during the initial evaluation about our role?

It does depend a little bit on what I'm there for, but it usually goes something like this.

"Hi, I'm Alex. I'm from occupational therapy. Your doctor referred me to come in because I know you've experienced a change in how you get around. My job is to figure out how you navigate at home, use the bathroom, get to the bedroom, and manage everything you do in your daily life. My job is to address toileting, dressing, and other activities. I also look at how our conditions affect our relationships, how we access sexuality, how we eat, and other daily tasks. I'm kind of your go-to person for these personal areas. This is anything that happens in the bedroom and bathroom. You can ask those things, and there's no judgment. I am open to all lifestyles."

How would I be able to address the OPISI after an OT evaluation and working with families?

The OPISI very rarely comes out during the initial evaluation unless the evaluation is specifically related to sexuality and intimacy or if it goes exceptionally well and everyone feels ready for it. Most of the time, during the initial evaluation, you'll gather much information about their life and who they are. You'll provide them with the opportunity to identify if sexuality is something they want to address more specifically and how their health condition or other aspects of who they are affect their participation. If they've identified this interest, you might write a related goal. They will clarify their concerns regarding their access to sexuality and intimacy, and then you may bring in the screener in a future session.

The OPISI screener is a one-page questionnaire where they can indicate whether they want more information or wish to discuss those topics. For someone who can and wants to, I give them the questionnaire and let them fill it out. Sometimes, I do this during the evaluation and tell them I'll pick it up from them later. Other times, I facilitate it with them, explaining or defining words as we go through because it uses terms like orgasm, pleasure, masturbation, and ejaculation. Not everyone has access to that education at their current stage, so it’s important to provide clarity as needed.

Thanks for your time today.

References

Citation

King, A. (2024). Sexuality and intimacy considerations: Pediatric acute care virtual conference. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5712. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com.