Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Skilled Nursing Facility Interventions: WC19 And The Transportation Of Older Adults In Wheelchairs, presented by Brenda Mahon, OTD, OTR/L, ATP.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the basic principles and issues of providing appropriate and safe transport for older adults traveling seated in a wheelchair.

- After this course, participants will be able to examine the wheelchair characteristics needed for use as a vehicle seat by understanding WC19, WC18, and WC20.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the basic seating and positioning principles to provide comfort and support for older adults during transportation.

Introduction

It's such an honor to be here. I'm a really big fan of OccupationalTherapy.com. I've been a member for two years and randomly met Fawn, the Senior Managing Editor, on a flight to the AOTA conference.

What are WC18, WC19, and WC20?

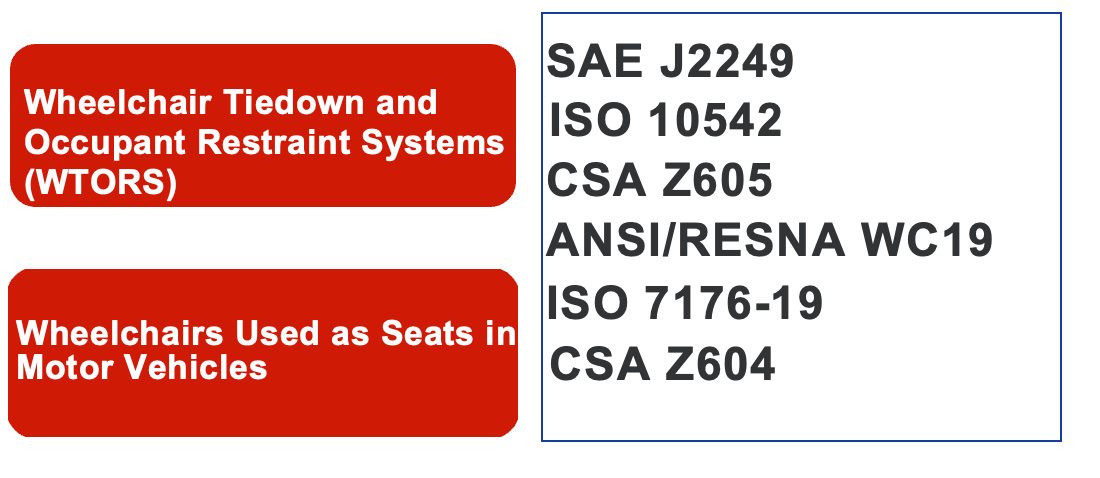

What are WC18, 19, and 20, and are these standards mandatory? We will talk about all of these, but briefly, WC18 covers the tie-downs and the occupant restraint system; WC19 compliance makes the wheelchair crashworthy; WC20 addresses the seating system. Here's a bulleted list of these voluntary standards for your reference.

- WC18 Compliant

- Wheelchair tie-down and occupant restraint systems (WTORS)

- WC19 Compliant

- Wheelchairs used as seats in motor vehicles

- WC20 Compliant

- Seating system

Standards

- Due to the lack of government regulations that address transportation safety for wheelchair users, efforts to develop equipment safety standards were initiated in the 1980s and 1990s by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) and RESNA, as well as by CSA and ISO (Schneider, 2015).

- SAE – Society of Automotive Engineers

- ISO – International Standards Organization CSA – Canadian Standards Association

- ANSI – American National Standards Institute

- RESNA – The Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America

Figure 1. This shows the different standards for each organization.

WC18 Compliant

- WTORS- ability to restrain the forward motion of wheelchair and rider

- Passes 30 mph dynamic crash tests

As mentioned above, WC18 covers the tie-downs and the occupant restraint system. An example of a person is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A person using WC18-compliant equipment.

It includes all the hardware that secures the wheelchair to the vehicle and provides a lap and shoulder belt to protect the seated rider. The most common WC18-compliant systems are the four-point strap systems, but docking systems are also included.

- Must meet federal requirements for seatbelt hardware

- Allow for correct use

- Pass a severe frontal crash test intact

All WC18-compliant tie-downs must be intact and have a seat belt. WC18 systems must be strong and adjustable for a range of occupants, allow a good seatbelt fit, and be compatible with WC19 wheelchairs. They must meet the applicable federal requirements for seatbelt hardware and allow for easy and correct use. WC18 must also pass a severe frontal crash test intact, must limit the movement of the wheelchair and the occupant, and must keep the occupant and the wheelchair upright to permit the occupant and wheelchair to be freed after a crash without tools. Compliant hardware must be labeled with a WC18 logo, and the instructions for use must include information consistent with applicable best safety standards. Equipment with a WC18 designation has a label, usually yellow.

WTORS-Wheelchair Tie-Down and Occupant Restraint System (ORS)

A wheelchair tie-down occupant restraint consists of a four-point strap wheelchair tie-down and the occupant restraint system (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Example of the seatbelt.

It's the primary means of securing the wheeled mobility device and restraining occupants in public transit vehicles in accordance with the accessibility requirements of the ADA. Figure 4 shows the ORS portion comprising of the shoulder and the lap belt, and the assembly used to restrain the passenger's torso and pelvis.

Figure 4. Example of the overall occupant restraint system.

The pelvic belt should sit low across the front of the pelvis, near the upper thighs, and not high over the abdomen or the wheelchair arm supports.

- Four WC18 Tie-down straps

- A seatbelt system with both pelvic and upper torso belts must be used.

The shoulder belt should sit across the middle of the shoulder and the center of the chest and connect with the lap belt near the hip of the wheelchair rider. It's best if the wheelchair is positioned close to the shoulder belt anchor point.

Studies

We're now going to go over a few studies.

Misuse of WTORS- Paratransit Retrospective Study

- 85 Paratransit vehicles

- Monitored by video x 12 months

- 475 trips

(Frost et al., 2018)

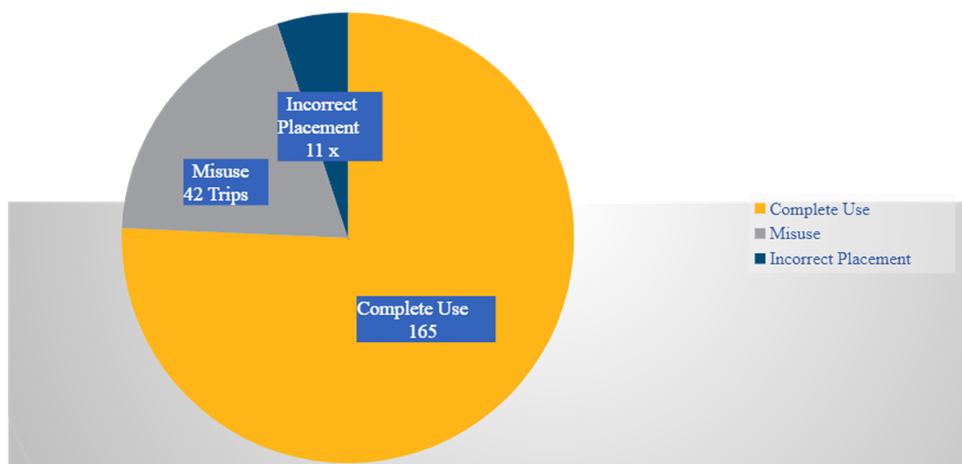

In this retrospective study, 85 paratransit vehicles were monitored via video for over a year. It included 475 trips. The tie-down usage described in the survey was subcategorized as either complete use, misuse, or non-use. We will focus on the 207 trips that were manual wheelchairs because most of our residents go out in manual-type wheelchairs from skilled nursing facilities. During the 207 trips, complete tie-down use was only seen in 165 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Graph of the 207 trips in this study.

Complete tie-down use was only seen in 80% of the cases. Meanwhile, misuse occurred in 42 trips, and incorrect placement occurred in 11. There were ten instances of improper attachment to the footrest or to the caster or an incorrect strap angle.

- Failure to apply one or both occupant restraint belts in 65% of trips

- 1 in 5 was not completely secured with tie downs

- Failure to apply the shoulder belt accounted for 98%

The objective was to understand what was occurring during paratransit in order to determine best practices. The video observation revealed that vehicle operators failed to apply one or both occupant restraint belts during 65% of the trips. And, the failure to apply the shoulder belt accounted for about 98% of those. This area has no room for error, as there should be 100% compliance. Although the tie-down used to secure the wheelchair exceeded the use of the occupant restraint, it's still not great.

Literature Review of Wheelchair Transportation Studies Identified

- Poor fit of safety systems for people seated in wheelchairs

- High levels of non-use and misuse of seatbelts

(Schneider et al., 2016)

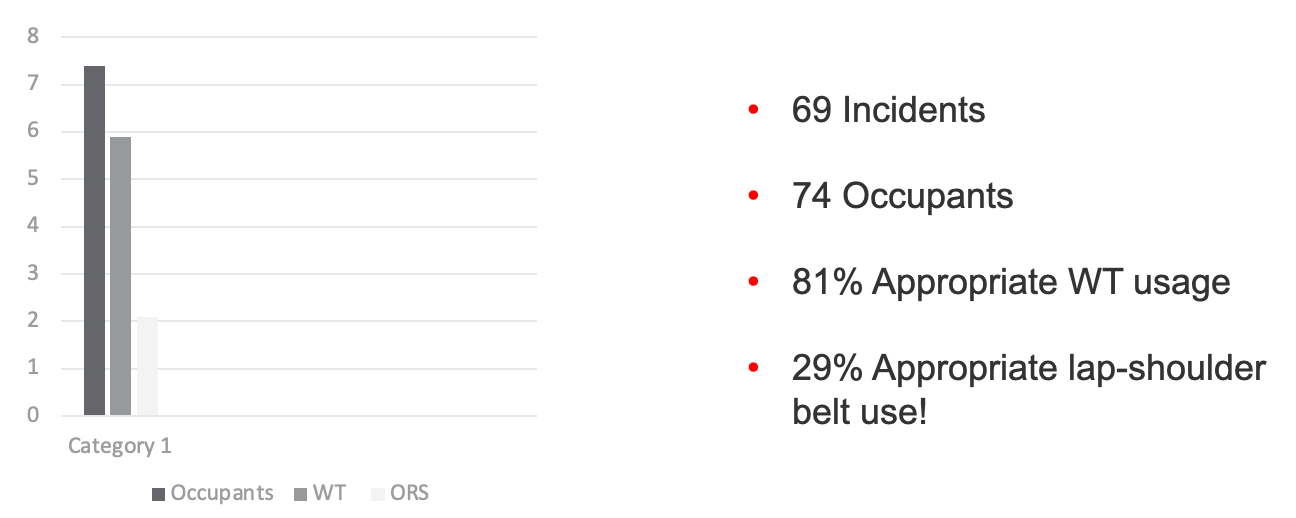

This study investigated 69 incidents involving 74 occupants seated in wheelchairs (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Graph of the results of the wheelchair transportation study.

Most of the incidents were frontal crashes. Although three non-crash events were included, 81% of occupants used tie-down systems appropriately, and only one case failed. However, only 29% of the occupants were appropriately restrained by the lap-shoulder belt. The lack of use or misuse that resulted in poor belt fit was frequent.

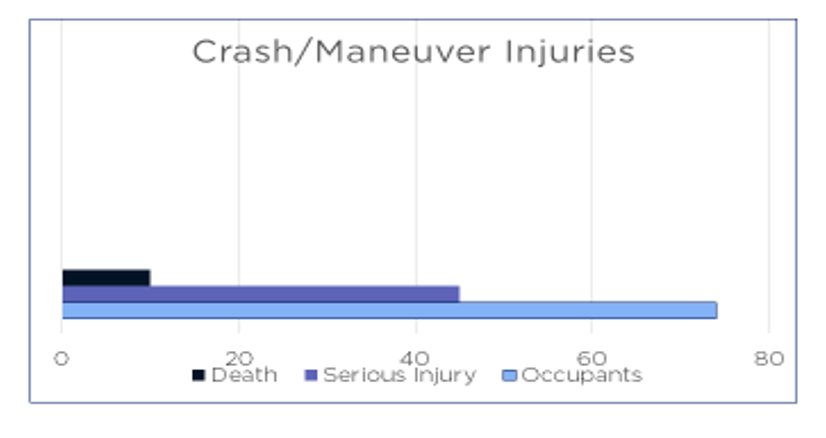

And, 62% of the occupants in these cases experienced serious injury, with 10 cases actually resulting in death. Again, not acceptable. And there's a graph representation (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Graph of crash/maneuver injuries.

Additional Contributing Factors

Before delving into the specifics of WC19 wheelchairs, let's take a moment to reflect on a crucial aspect often overlooked—wheelchairs without the WC19 designation. As therapists, consider those residents frequently transported in wheelchairs for outings or appointments, especially those who were once capable of transferring independently. The optimal goal remains to reintegrate them into transferring from the wheelchair to the manufacturer's seat and restraint system, the safest option.

When contemplating discharging someone, therapists should ponder the feasibility of restoring their ability to transfer, particularly for residents actively participating in outings requiring wheelchair use. This applies not to patients requiring maximal assistance or mechanical lifts but to those who demonstrated past transfer capabilities, even if with minimal or moderate assistance.

Q'Straint, renowned for occupant restraints, offers valuable educational resources. Therapists can benefit from training webinars, on-site national seminars held twice a year, and various live events. It's imperative for therapists to be aware of these offerings and communicate their significance to administrators, particularly for facilities handling patient transportation independently.

For facilities with dedicated transportation, such as vans for patient outings and appointments, Q'Straint's seminar becomes even more relevant. The comprehensive training covers wheelchair transportation regulations, best practices, and securement principles, equipping attendees to address real-world securement and transportation challenges. Additionally, therapists can access free resources on Q'Straint's website, including a downloadable fleet training manual and an inspection form for occupant restraint and tie-down systems—valuable tools worth sharing with administrators.

RESNA, a key authority in the field, emphasizes that wheelchairs used as passenger seats in motor vehicles should provide effective occupant support under frontal impact test conditions, mirroring the standards set for passenger and child safety seats. WC19-compliant wheelchairs, identified by the distinctive logo in the top right-hand corner (Figure 8), facilitate proper placement of vehicle-anchored lap and shoulder-belt restraints. Furthermore, they are designed for securement with a four-point strap-type tie-down, aligning with the current universal method of wheelchair securement.

Figure 8. WC-19 Logo.

In conclusion, therapists should be cognizant of the importance of WC19 compliance and consider Q'Straint's educational resources as a valuable asset in ensuring the safety and well-being of wheelchair-bound individuals during transportation. Sharing this knowledge with administrators can contribute to an enhanced understanding of best practices in wheelchair securement and support.

W19 Compliant

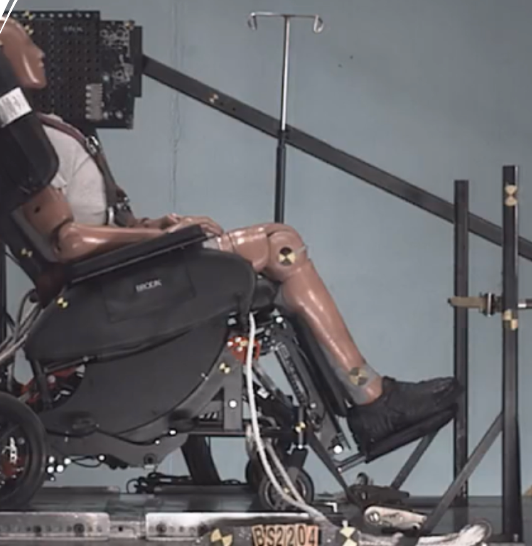

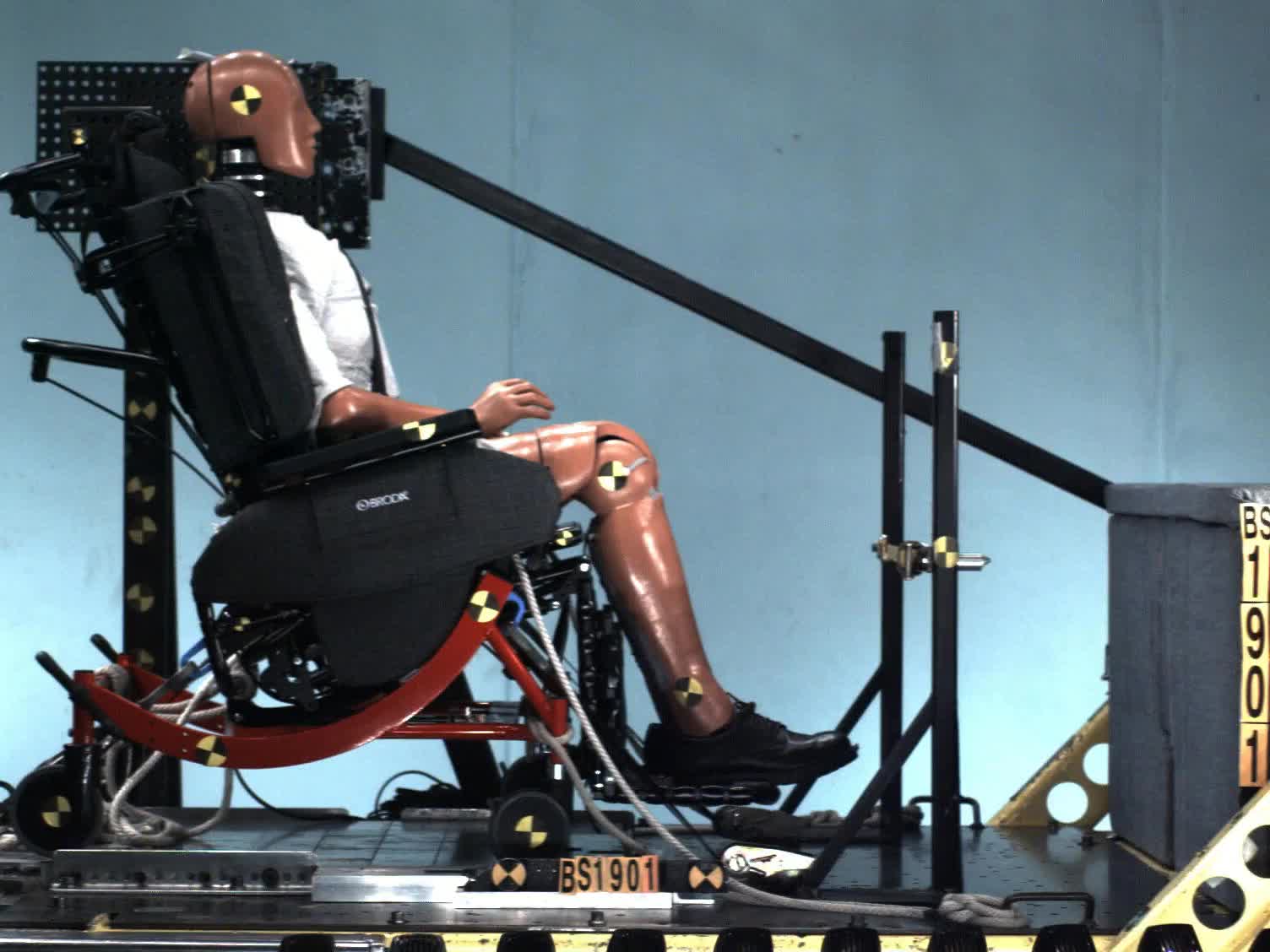

What does it take to be WC19 compliant? It is deemed crash-worthy by the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute to be used as a seat in a motor vehicle, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. An example of a W19-compliant wheelchair from Broda.

The WC19 standard covers various wheelchair types, including manual wheelchairs, strollers, power wheelchairs, and three and four-wheeled scooters. This inclusivity ensures that safety measures are applied across the entire spectrum of mobility devices. One key requirement is compatibility with the four-point strap-type tie-downs, offering a universal method for securement.

Mandated features include labeled securement points and the prohibition of sharp edges that could harm riders or damage tie-down belts. While it may seem obvious that all wheelchairs should be free of sharp edges, the specification underscores a need that emerged from real-world incidents, emphasizing the importance of such safety measures.

Considering common issues with seatbelt fit and usage, WC19 also mandates the availability of a crashworthy wheelchair-anchored lap belt. This improves seatbelt fit, reduces dwell time, and eliminates transportation providers' need to intrude on the rider's personal space to secure the belts. This provision addresses practical challenges in securing individuals and prompts reflection on potential reasons for poor compliance with shoulder belts, which often involve close and personal interactions during the securing process.

Moreover, standardized hardware on the wheelchair-anchored lap belt allows for connection to WC18 shoulder belts, enabling the creation of a comprehensive lap and shoulder belt system. This integrated approach ensures a higher level of safety during transportation, aligning with the overarching goal of enhancing the well-being of individuals using mobility devices. As therapists and administrators, understanding and advocating for these standards contribute to a safer and more secure transportation environment for wheelchair-bound individuals.

This standard was initiated in the mid-'90s. It focused on the design and performance of wheelchairs used as seats in motor vehicles to provide equal protection or as close to those traveling in manufactured vehicle seats. It's to provide guidelines for manufacturers testing equipment across different vehicles and prioritizing frontal crashes since over one-half of all fatalities and injuries occurred during frontal crashes. Another example from Broda can be seen in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Another example of a WC 19 wheelchair.

- WC19 Wheelchairs must pass a frontal crash test

- WC and occupant must stay upright without significant collapse.

A WC19 wheelchair must also pass a frontal crash test without structural failure or allowing any excessive excursion of the wheelchair or the rider. The wheelchair has to stay upright, and it has to support the occupant in an upright posture without significant collapse during impact testing (Figure 11).

Figure 11. An example of a front crash test.

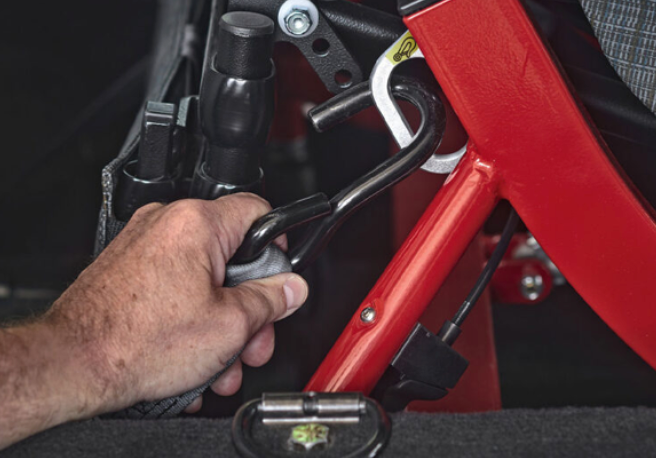

The wheelchair must also be able to be secured quickly. A tie-down straps need to be directly attached from the floor to the wheelchair securement point. The standard includes a rating system for ease of using the vehicle-anchored seatbelt and the resulting quality of the seatbelt fit, so the seatbelt fit is really important.

- The wheelchair must not shift more than 40mm sideways during the 45° tilt test.

To assure lateral stability, the wheelchair must not shift more than 40 millimeters sideways when subjected to a 45-degree tilt test.

Figure 12. Ensuring lateral stability in the equipment.

- DME Vendors, MDs, and Therapists Need to Know

The labeling and instruction requirements include the logo, marking, and information consistent with best safety practices, and the tie-down securement point. Figure 13 shows another example.

Figure 13. An example of a client in a WC19 wheelchair.

A crucial aspect to understand about WC19 compliance is that it cannot be retrofitted. Similar to certain features in vehicles, WC19 standards must be incorporated during the manufacturing process; they cannot be added later. This underscores the importance of informing durable medical equipment vendors, physicians, and therapists about the advantages of utilizing WC19-compliant chairs. It's incumbent upon us to educate patients about transport chairs, emphasizing the significance of WC19 compliance.

To facilitate the use of WC19 chairs, physicians and therapists play a vital role. Physicians should consider prescribing transport chairs when appropriate, and therapists can support this by writing letters of medical necessity. While coverage for WC19 chairs may be limited, establishing a practice of justifying their necessity can be instrumental. In this regard, I have included some justifications for your reference.

An intriguing feature of WC19 compliance is the requirement for the ability to attach using only one hand within 10 seconds. This emphasizes the practicality and efficiency of the design, ensuring ease of use and quick attachment—a notable factor in emergency situations or situations requiring swift and secure chair attachment.

- Auxiliary equipment should be removed and secured separately when possible.

Auxiliary equipment should be removed and secured separately in the vehicle whenever possible. Figure 14 shows an IV pole.

Figure 14. A client with an auxiliary IV pole.

As depicted in the accompanying image, it's noteworthy that an IV pole is positioned alongside the wheelchair. A best practice in transportation safety is to store equipment separately whenever feasible. This precautionary measure aims to prevent equipment from breaking free during a crash, potentially causing injury to other occupants or the person in the wheelchair.

Specific recommendations include using gel cell batteries on powered wheelchairs, as these provide enhanced stability and safety in the event of a crash. Additionally, for situations where trays cannot be removed from the wheelchair during transit, it is advisable to utilize soft or padded trays to minimize the risk of injury.

An important point is that headrests are not currently subjected to WC crash testing. There are currently no headrests designated as WC-compliant. This information is crucial for therapists, physicians, and equipment vendors to consider when assessing the safety and appropriateness of wheelchair accessories, reinforcing the need for a comprehensive understanding of safety standards in wheelchair transportation.

- WC19 Goals

- Provide wheelchair users comparable crash protection when traveling in a wheelchair

- Provide manufacturers with a minimum set of requirements

The primary goals of WC19 are centered around ensuring the provision of wheelchairs that offer comparable crash protection for individuals traveling in wheelchairs. It is crucial to recognize that, while the safest space remains the manufacturer's seat and restraint system, WC19 serves as the next best option. The intent is to establish a set of minimum requirements for manufacturers, guiding them in creating wheelchairs that prioritize safety during transportation.

As therapists familiar with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), we understand its pivotal role in ensuring transportation access for individuals with disabilities across various aspects of life, including employment, education, and recreation. Given that a significant portion of the 3.3 million wheelchair users in the United States may face challenges transferring to a motor vehicle seat, especially evident among residents in skilled nursing facilities, WC19 becomes a crucial designation. Its aim is to afford wheelchair users a level of safety comparable to or as close as possible to that of occupants seated in motor vehicles, acknowledging the unique needs and constraints of individuals relying on wheelchairs for transportation.

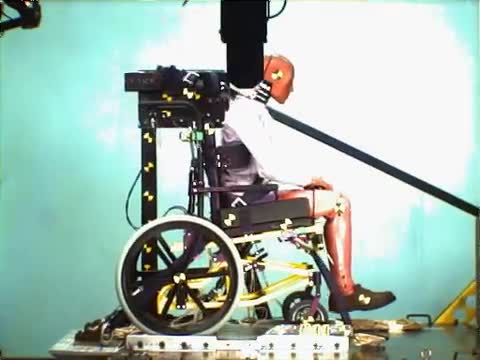

Here are some videos that show crash tests for both.

Crash Test Video-Not WC19 Certified

Crash Test Video-WC19 Certified

In which chair would you want your loved ones? This underscores the significance of prioritizing safety and compliance with standards like WC19. The availability of standardized hardware on the wheelchair-anchored lap belt, facilitating connection to the WC18 shoulder belt, contributes to creating a comprehensive and secure system, as shown in Figure 14.

As caregivers, therapists, and advocates, the pursuit of safety standards in wheelchair design becomes a shared responsibility to ensure the well-being of our loved ones during transportation.

W20 Compliant

- Wheelchair seating systems that utilize third-party seats, back supports, etc.

- Performance criteria include excursion limits and prohibition of sharp edges or broken parts.

A wheelchair seating system for motor vehicles is not always purchased from a single manufacturer but is created by one company. This isn't as common in skilled nursing facilities anymore, but it is applicable. We're talking about older adults today, but it's applicable as many are in custom wheelchairs, so it's important to understand this. This standard applies to third-party seats, back supports, and attachment hardware so they use a generic surrogate wheelchair frame to create a wheelchair for testing; the WC20 requirements mirror those of WC19 related to the seating system.

The performance criteria for the crash test include the same excursion limits, prohibits sharp edges or broken parts, provides good support and fit for the rider, and cannot prevent easy seatbelt application.

- Good News

- Motor vehicles are safer

- Improvements in restraint-system technologies

- Seat belt laws decreased fatalities in MVAs

Over the past 40 years, there has been an exponential increase in motor vehicle safety for both drivers and passengers. This remarkable progress can be attributed primarily to substantial advancements in vehicle safety and restraint-system technologies. The impetus for these improvements came from the demand for enhanced safety regulations, driven by initiatives from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

The implementation of seatbelt laws, coupled with impactful federal ad campaigns like "Click It or Ticket," has played a pivotal role in significantly reducing occupant injury risk. As someone who has been around for a while, I recall the era when unrestrained occupants were more prevalent, leading to more accidents with severe consequences. The cultural shift towards increased seatbelt usage has significantly made road travel safer and reduced fatalities and injuries caused by individuals not wearing seat belts.

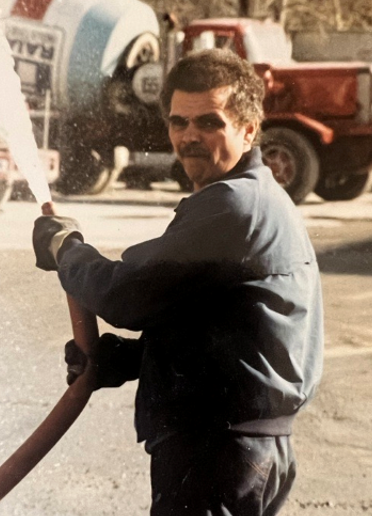

Figure 15 shows my dad, and I miss him dearly.

Figure 15. Image of the author's father.

He was a cement truck driver for a living and was a "clothes horse" who liked to dress to the nines. Anytime we went out, my dad was the one who took a long time to get ready. He never wore seat belts because he said it wrinkled his clothes. However, after he got a ticket, he changed his mind so that campaign worked.

Reflecting on a personal experience from years ago, the importance of seat belt safety hits home. My twin nieces just celebrated their 17th birthday and have recently obtained their driving licenses. Unfortunately, one of them was involved in a severe single-car accident, where the vehicle flipped multiple times.

What stands out is that she was in the backseat, reclined without a seatbelt - a decision that could have had devastating consequences. It's a scenario that prompts reflection on our own habits, especially when traveling in the backseat of various vehicles. Personally, I've encountered challenges with seatbelts in shuttles or Ubers, and it's a common experience for many.

This incident was a stark reminder of the potential risks of neglecting seat belt use. Despite the challenges of securing a seatbelt in certain situations, the outcome for my niece emphasizes the critical importance of buckling up. Miraculously, she survived the accident, but not without serious injuries - 13 broken ribs, a tricep tear, and a significant scalp injury that required a skin graft, leaving a visible scar.

This firsthand account is a poignant reminder that accidents can happen anytime, and wearing a seatbelt can make a life-altering difference. It's a powerful lesson that transcends age, emphasizing seat belts' crucial role in ensuring our safety on the road.

Transportation Safety

The leading cause of disabling and fatal injuries in motor vehicle accidents stems from the impact of the occupant with the vehicle interior or external objects, often referred to as the "human collision" (Schneider, 2015). Additionally, improperly positioned belt restraints contribute to serious injuries. While safety standard improvements benefit many, statistics reveal that individuals seated in wheelchairs while traveling in motor vehicles face a significantly higher risk of severe or fatal injuries (Frost & Bertocci, 2007; Frost, 2010).

During motor vehicle crashes or non-collision events such as abrupt turns or stops, wheelchair users, especially those in skilled facilities, struggle to stabilize their wheelchairs or brace for impact. Research indicates that individuals seated in wheelchairs during travel are 45 times more likely to be injured in an accident than typical passengers (Buning et al., 2012).

Recognizing these risks, there is an opportunity for therapy to focus on facilitating transfers for wheelchair users. While the wheelchair remains essential for mobility over distances, encouraging transfers to the manufacturer's seat emerges as the safest option. The alarming statistics underline the urgency of addressing safety concerns for this demographic.

Every year, RTAs result in approximately 1.25 million deaths (Ang et al., 2017). Concerns escalate for older adults, as those over 65 face a doubled risk of severe injury and fatality in motor vehicle collisions (Songer et al., 2004; Yee, 2006). Adults over 74 are particularly vulnerable, with twice the likelihood of fatal accidents compared to their younger counterparts. Studies attribute the increased fatality rate to low physiologic reserve and diminished adaptability to trauma, emphasizing the need for targeted care for the elderly.

Trauma systems and policymakers must address the growing needs of the aging population. In motor vehicle accidents, older adults are admitted to emergency departments and trauma centers more frequently, yet there are no well-established trauma management guidelines specific to this demographic. Chest wall injuries, such as rib fractures, are prevalent among the elderly, often going undetected and correlating with increased mortality and pneumonia risk (Songer et al., 2004; Yee, 2006). Marques et al., 2020, reported that of 161 participants aged 65 and older- 72% reported moderate to severe pain at the emergency department evaluation.

Paratransit vehicles, commonly used for transporting wheeled mobility devices, pose additional challenges due to their high-G environments and increased crash severity. In fact, the frontal impact of a paratransit vehicle is three times greater than a large bus (Klinich et al., 2022). The delta V, measuring the change in vehicle speed during impact, emphasizes the risks associated with smaller vehicles. The need for wheelchair tie-downs and occupant restraints in paratransit vehicles becomes crucial for ensuring occupant protection.

Considering the risks, using a standard wheelchair for transport is discouraged. Regular wheelchairs lack crash testing, exacerbate postural abnormalities, and fail to provide adequate support and comfort. In the context of Medicaid non-emergency medical transport, beneficiaries with chronic health conditions utilize this service at higher rates, emphasizing the importance of addressing safety concerns in medical transportation, especially for those with specific health conditions such as chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease (CMS, 2021).

Seating and Positioning to Prevent Wounds

When dealing with residents requiring moderate or extensive assistance, especially those unable to transfer from a wheelchair to a motor vehicle seat, the challenges extend beyond safety in transit. Pressure injuries and related deaths are on the rise, with one in ten nursing home residents having a pressure injury, commonly stage two. Pressure injuries led to 20,300 deaths worldwide in 2017 (Chung et al., 2022). The notion that prolonged tissue loading is acceptable for short periods has been dispelled, emphasizing the need for proper seating and positioning.

Consider the scenario of residents who rarely leave their beds. These individuals, often lacking their own wheelchairs, face challenges when sudden transportation needs arise.

Seating goals include:

- Provide good postural alignment and stability

- Optimal pressure redistribution through seat and back

- Provide good contact between the body and the seating system

- Provide comfort to allow for engagement

With age-related tight muscles, decreased strength, and limited flexibility, expecting residents to conform to a rigid seating position (90/90/90) is unrealistic. A tilt or tilt-and-recline feature may be useful to provide better contact between the seating surface and the client. This improves support and pressure redistribution and reduces the caregiver burden for hygiene changes. Tilt angles up to 30 degrees, like in Figure 16, are acceptable, offering a more accommodating solution for individuals with difficulty sitting upright.

Figure 16. Example of a tilted wheelchair.

Despite the significance of wheelchair transportation safety standards, there is a lack of federal or state regulations mandating compliance. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services do not require adherence to WC19 standards, necessitating advocacy and lobbying efforts for policy changes.

Exploring the inadequacies of using stretchers for medical transport, particularly for individuals with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, underscores the necessity for WC19-compliant wheelchairs. Recognizing the need for tailored solutions in non-emergency medical transport, the focus shifts to individual resident needs and the unique challenges posed by their health conditions. While WC19-compliant transport chairs are not proposed as a universal fix, their strategic implementation within a facility is advocated to ensure the well-being and comfort of residents during transit.

Moving forward, the emphasis lies on utilizing appropriate equipment and fostering awareness within the healthcare team. Education and training initiatives should extend to all staff involved in the transportation process, including maintenance and activities personnel. A crucial aspect is addressing the professional drivers of the vehicles, ensuring they receive proper training to secure passengers effectively. Communicating these needs to administrators becomes paramount, as it underscores the significance of employing the right tools and ensuring that those entrusted with transporting residents are adequately trained to guarantee their safety and well-being.

Summary

In summary, the importance of WC19-compliant wheelchairs for transportation cannot be overstated. The key factors encompass proper securement and the provision of effective postural supports during transport, ultimately ensuring a safe wheelchair transportation experience. For those seeking additional information on this critical topic, valuable resources can be found on the Michigan Engineering Wheelchair Transportation Safety website and the Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America (RESNA). Exploring these platforms can offer further insights and knowledge for those interested in delving deeper into the subject.

Question and Answer

In the skilled nursing facility, when using a standard transport chair for transportation, is there a difference in safety compared to using WC19 designated chairs, and are all transportation vans safe for use with standard transport chairs?

From what I understand, to ensure optimal safety, both WC18 designation for the transportation wheelchair tie-down and occupant restraint system in the vehicles, whether private or facility-owned, along with a WC19 designated wheelchair, would provide the best protection and safety for the patient. All these elements must be in place for comprehensive safety during transportation.

You mentioned that WC18 had to pass a 35-mile-per-hour crash test. Is the same impact speed used for frontal crash testing, and is there an increased fatality rate reported?

Yes, the same impact speed is utilized for frontal crash testing, and there has been an increased fatality rate reported. Additionally, it's noteworthy that WC19 is expanding its testing scope to include side impact and rear crash testing, recognizing the diverse nature of accidents.

I work in ILF and ALF facilities and assumed training in these areas, but now I'm wondering. Are these regulations mandatory, and are ILF and ALF staff typically trained in them?

Interestingly, these regulations are voluntary, not mandatory. While one might assume staff in Independent Living (ILF) and Assisted Living Facilities (ALF) are trained, it's not guaranteed. Awareness is crucial, especially given the litigious nature of our society. Changes and improvements often happen after incidents occur, making ongoing education and awareness essential.

How have administrators responded when you've brought this information to their attention, and how do you recommend approaching administration?

While I haven't personally worked in a facility, as part of my role as an educator, I've engaged with administrators on this topic. Many are receptive and appreciative once informed, some even purchasing WC19 designated chairs for multi-use transportation. It's advisable to approach administrators gradually, emphasizing the long-term benefits, and even starting with acquiring one multi-use chair can be a significant step forward.

Working in a skilled nursing facility can be challenging, especially with the additional layer of transportation safety. How do you suggest therapists navigate these challenges?

The RESNA, Q'Straint, and Michigan transportation websites are valuable resources. While the challenges may seem daunting, obtaining information and utilizing these resources can empower therapists. Small steps, such as introducing one multi-use chair, can significantly improve facility transportation safety over time.

Have you conducted inservices for facilities as part of your role with Broda, and have you seen positive outcomes from these efforts?

Yes, I have conducted inservices for facilities, including the VA. Positive outcomes include facilities acquiring a fleet of WC19-designated chairs for improved safety and compliance with standards.

Can you share more about your experiences offering this presentation at an administrator's conference?

Despite facing competition with MDS courses, the eight participants who attended had experienced incidents in their facilities. This highlights that awareness and changes are often sought only after incidents occur, emphasizing the critical need for ongoing education and proactive measures.

How do you recommend talking to administrators about these standards, and have you faced any resistance from them?

As an educator, I've spoken to generally receptive and appreciative administrators. Resistance may arise due to the voluntary nature of the regulations, but emphasizing long-term benefits and starting with small changes, such as acquiring one multi-use chair, can be an effective approach.

References

Downie, A., Chamberlain, A., Kuzminski, R., Vaz, S., Cuomo, B., & Falkmer, T. (2020). Road vehicle transportation of children with physical and behavioral disabilities: A literature review. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, 27(5), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2019.1578408

Hryciów, Z. (2022). The safety of wheelchair occupants in motor vehicles. The Archives of Automotive Engineering – Automotive Archive, 97(3), 5-13. https://doi.org/10.14669/AM/155001

Klinich, K. D., Manary, M. A., Orton, N. R., Boyle, K. J., & Hu, J. (2022). A literature review of wheelchair transportation safety relevant to automated vehicles. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(3), 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031633

Lee, W. Y., Cameron, P. A., & Bailey, M. J. (2006). Road traffic injuries in the elderly. Emergency medicine journal: EMJ, 23(1), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2005.023754

Zemp, R., Rhiner, J., Plüss, S., Togni, R., & Plock, J. A. (2019). Wheelchair tilt-in-space and recline functions: Influence on sitting interface pressure and ischial blood flow in an elderly population. BioMed Research International. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4027976

Citation

Mahon, B.(2023). Skilled nursing facility interventions: WC19 and the transportation of older adults in wheelchairs. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5662. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com